1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Virtue Ethics

Author: David Merry Category: Ethics , Historical Philosophy Word Count: 1000

Listen here

Think of the (morally) best person you know. It could be a friend, parent, teacher, religious leader, thinker, or activist.

The person you thought of is probably kind, brave, and wise. They are probably not greedy, cruel, or foolish.

The first list of ‘character traits’ ( kind, brave, etc.) are virtues, and the second list ( arrogant, greedy, etc.) are vices . Virtues are ways in which people are good; vices are ways in which people are bad.

This essay presents virtue ethics, a theory that sees virtues and vices as central to understanding who we should be, and what we should do.

1. Virtue and Happiness

Virtues are excellent traits of character. [1] They shape how we act, think, and feel. They make us who we are. Virtues are acquired through good habits, over a long period of time.

1.1. Eudaimonia

According to Aristotle (384-322 BCE) virtues are those, and only those, character traits we need to be happy. [2] Many virtue ethicists today agree. [3] These virtue ethicists are called eudaimonists, after the Greek word eudaimonia, usually translated as “happiness,” “flourishing,” or “well-being . ” [4]

For eudaimonists, happiness is more than a feeling: it involves living well with others and pursuing worthwhile goals. This includes cultivating strong relationships, and succeeding at such projects as raising a family, fighting for justice, and (moderate yet enthusiastic) enjoyment of pleasure. [5]

Eudaimonists believe our happiness is not easily separated from that of other people. Many would consider the happiness of their friends and family as part of their own. Eudaimonists may extend this to complete strangers, and non-human animals. Similarly for causes or ideals: eudaimonists believe complicity in injustice and deceit reduces a person’s happiness. , [6]

If eudaimonists are right about happiness, then it is plausible that we need virtues such as honesty, kindness, gratitude and justice to be happy. This is not to say that the virtues will guarantee happiness. But eudaimonists believe we cannot be truly happy without them.

One concern is that vicious people often seem happy. For example, dictators live in palaces, apparently rather pleasantly. Eudaimonists may not think this amounts to happiness, but many would disagree. And if dictators can be happy, then we certainly can be happy without the virtues. Answering this objection is an ongoing project for eudaimonists. [7]

1.2. Emotion, Intelligence, and Developing Virtue

Eudaimonists believe emotions are essential to happiness, and that our emotions are shaped by our habits. Good emotional habits are a question of balance.

For example, eudaimonists argue that honest people habitually want to and enjoy telling the truth, but not so much that they will ignore all other considerations–a habit of enjoying pointing out other people’s shortcomings will leave us friendless, and so is not part of honesty. [8]

Because virtue requires balancing competing considerations, such as telling the truth and considering other people’s feelings, virtue also requires experience in making moral decisions. Virtue ethicists call this intellectual ability practical intelligence, or wisdom. [9]

2. Virtue and Right Action

Virtue ethicists believe we can use virtue to understand how we should act, or what makes actions right.

According to some virtue ethicists, an action is right if, and only if, it is what a virtuous person would characteristically do under the circumstances. [10] On rare occasions, virtuous people do the wrong thing. But this is not acting characteristically.

2.1. Being Specific

“Do what virtuous people would do” is not very specific, and we may be left wondering what the theory is actually saying we should do.

One way to make it more specific is to generate rules for each of the virtues and vices, called “v-rules.” Two examples of v-rules are: be kind, don’t be cruel. The v-rules give specific guidance in many cases: writing an email just to hurt someone’s feelings is cruel, so don’t do it. [11]

Unfortunately, the virtues can conflict: if a friend asks whether we like their new partner, it may be more honest to say we do not , but kinder to say we do. In this case it is hard to say what the virtuous person would do.

Virtue ethicists might respond that other ethical theories will also struggle to give clear guidance in hard cases. [12]

Second, they might try to understand how a virtuous person would think about the situation. Remember that virtuous people have practical intelligence, and habitually care about other people’s happiness and telling the truth. So they may consider a lot of particular details, including how close the friendship is, how bad the partner is, how gently the friend may be told. [13]

This may not provide a specific answer, but virtue ethicists hope they can at least provide a helpful model for thinking about hard cases. [14]

2.2. Explaining Why

We have seen how virtue ethics tells us what to do. But we also want to know why we should do it.

Virtue ethicists point out that if we ask virtuous people, they will explain why they did what they did. [15] Their reasoning results from their excellent emotional habits and practical intelligence–that is, from their virtue. And if we want to be happy, we need to cultivate virtue. So these should be our reasons too.

But in explaining their decision, the virtuous person won’t necessarily mention virtue. They might, for example, say, “I wanted to avoid hurting their feelings, so I told the truth gently.” [16]

It might then seem that something other than virtue–in our example, the importance of other people’s feelings–explains why the action is right . But then this other thing should be central to ethical theory, instead of virtue.

Virtue ethicists may respond that the moral weight of this other thing depends on which character traits are virtues. Accordingly, if kindness were not a virtue, there may be no moral reason to care about others’ feelings. [17]

3. Conclusion

Virtue ethicists recommend reflecting on the character traits we need to be happy. They hope this will help us make better moral decisions. Virtue ethics may not always yield clear answers, but perhaps acknowledging moral uncertainty is not a vice.

[1] Others may define virtue as admirable or merely good traits of character. For additional definitions of virtue and understandings of virtue ethics, see Hursthouse and Pettigrove’s “Virtue Ethics.”

[2] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , Book One, Chapter 9, Lines 1099b25-29. For this interpretation, see Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness, p. 6.

[3] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics , pp. 165-169, “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, p. 226, Foot, Natural Goodness , pp. 99-116.

There are many other accounts of virtue worth considering. One major alternative is sentimentalist accounts, such as that of Hume and Zagbzebski, who define virtues as those character traits that attract love or admiration. Some scholars argue that Confucian ethics is a virtue ethic, though this is debated: see Wong, “Chinese Ethics.” Also see John Ramsey’s Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts . For an African understanding of virtue, see Thaddeus Metz’s The African Ethic of Ubuntu .

[4] Hursthouse has a detailed and accessible discussion of the merits of different translations of eudaimonia in On Virtue Ethics, pp. 9-10.

[5] Some people find this account of virtue surprising because they think virtue must involve sacrificing one’s own happiness for the sake of other people, and living like a saint, a monk, or just being a really boring and miserable person. In this case it may be more helpful to think in terms of ‘good character’ than ‘virtue’. David Hume amusingly argued that some alleged virtues, such as humility, celibacy, silence, and solitude, were vices. See his Enquiry 9.1.

[6] The idea that injustice erodes everybody’s happiness is not to deny that it especially harms people who are treated unjustly. However, eudaimonists consider being unjust, or deceiving others to be bad for us.

[7] For a compelling discussion of this objection to eudaimonism, see Blackburn, Being Good, pp. 112-118 . Eudaimonists have been trying to answer this objection for a long time. Indeed, arguing that it is more beneficial to be just than unjust is one of the major themes of Plato’s Republic. For more recent attempts to make the case, see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, Chapter 8, or Foot, Natural Goodness, especially Chapter 7. See also Kiki Berk’s Happiness .

[8] The idea that the virtues involve finding a balance is called ‘the doctrine of the mean.’ See Nicomachean Ethics, Book II, Chapter 6, lines 1106b30-1107a5. For one contemporary account of the emotional aspects of virtue, see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, pp.108-121.

[9] Aristotle discusses practical intelligence in Nicomachean Ethics Book 6. For a contemporary account see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, pp. 59-62.

[10] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics, pp. 28-29. This is sometimes called a qualified-agent account. For some alternatives, see van Zyl’s “Virtue Ethics and Right Action”.

[11] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics, pp. 28-29.

[12] For other moral theories, see Deontology: Kantian Ethics by Andrew Chapman and Introduction to Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz. When reading, you might consider whether these theories would give you clearer guidance about your friend’s partner.

[13] See Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 2, chapter 9, lines 1109a25-30. Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics pp. 128-129.

[14] For two examples of how virtue ethics may be helpfully applied to tough moral decisions, see Hursthouse’s “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, and Foot’s “Euthanasia”.

[15] Hursthouse, “Virtue Ethics and Abortion”, especially p. 227, pp. 234-237. “Do what a virtuous person would do” is only supposed to tell us what we should do, not how we should think .

[16] This objection is discussed in Shafer-Landau’s The Fundamentals of Ethics, pp. 272-274.

[17] On this connection between facts about morality on facts about virtue and human happiness, see Hursthouse “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, pp. 236-238.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics . C. 355-322 BCE. Trans. Roger Crisp. Cambridge UP. 2014.

Blackburn, S. Being Good. Oxford UP. 2001.

Boxill, B. “How Injustice Pays.” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 9(4): 359-371. 1980.

Foot, P. Natural Goodness. Oxford UP. 2001.

Foot, P. “Euthanasia”. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 6(2): 85–112. 1977.

Foot, P. “Moral Beliefs.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 59: 83-104. 1958.

Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. 1777.

Hursthouse, R. “Virtue Theory and Abortion.” Philosophy & Public Affairs . 20(3): 223-246. 1991.

Hursthouse, R. On Virtue Ethics. Oxford UP. 1999.

Hursthouse, Rosalind and Glen Pettigrove, “Virtue Ethics”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Zalta, E.N (ed.). 2018,

Nussbaum, M. The Fragility of Goodness. Cambridge UP. 2nd Edition, 2001.

van Zyl, L. “Virtue Ethics and Right Action”. In Russell, D. C (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Virtue Ethics. Cambridge UP. 2013.

Plato. Republic. C. 375 BCE. Trans. Paul Shorey. Harvard UP. 1969.

Shafer-Landau, R. The Fundamentals of Ethics . Fourth Edition. Oxford UP. 2017.

Wong, D. “Chinese Ethics”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition) . Zalta, E.N (ed). 2021.

Zagzebski, L.T. Exemplarist Moral Theory. Oxford UP. 2017.

Related Essays

Happiness by Kiki Berk

Deontology: Kantian Ethics by Andrew Chapman

Introduction to Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz

G. E. M. Anscombe’s “Modern Moral Philosophy” by Daniel Weltman

Philosophy as a Way of Life by Christine Darr

Ethical Egoism by Nathan Nobis

Why be Moral? Plato’s ‘Ring of Gyges’ Thought Experiment by Spencer Case

Situationism and Virtue Ethics by Ian Tully

Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature by G. M. Trujillo, Jr.

Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts by John Ramsey

Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 2: The Cultivation Analogy by John Ramsey

The African Ethic of Ubuntu by Thaddeus Metz

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

David Merry’s research is mostly about ethics and dialectic in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, although he also occasionally works on contemporary ethics and philosophy of medicine. He received a Ph.D. from the Humboldt University of Berlin, and an M.A in philosophy from the University of Auckland. He is co-editor of Essays on Argumentation in Antiquity . He offers interactive, discussion-based online philosophy classes and maintains a blog at Kayepos.com .

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 21 thoughts on “ virtue ethics ”.

- Pingback: Philosophy as a Way of Life – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Aristotle on Friendship: What Does It Take to Be a Good Friend? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ursula Le Guin’s “The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas”: Would You Walk Away? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: G. E. M. Anscombe’s “Modern Moral Philosophy” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Why be Moral? Plato’s ‘Ring of Gyges’ Thought Experiment – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Article on Virtue Ethics at 1000-Word Philosophy - Kayepos: Philosophical Capers

- Pingback: - Kayepos: Philosophical Capers

- Pingback: Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update | Daily Nous

- Pingback: Rousseau on Human Nature: “Amour de soi” and “Amour propre” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: What Is It To Love Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Because God Says So: On Divine Command Theory – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Consequentialism and Utilitarianism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Deontology: Kantian Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Happiness: What is it to be Happy? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Indoctrination: What is it to Indoctrinate Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: The African Ethic of Ubuntu – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Situationism and Virtue Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 2: The Cultivation Analogy – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Comments are closed.

Inner Strength For Life – The 12 Master Virtues

Our journey of growth in life can be described as a journey of developing both insights and also virtues (qualities of mind and heart). This article maps out what are the main qualities to develop, and what particular strengths or gifts are gained from each of them.

Developing virtues is not about being better than others, but about developing the potential of our own heart and mind. The philosophers of ancient Greece , Buddha , the Yogis, and the Positive Psychology movement all value the cultivation of certain personal qualities. In this essay I attempt to systematize these core strengths into 12 “buckets” or “power virtues”, as many of them share common features.

Each of these virtues, rather than being an inborn personal trait, are habits and states of mind that can be consciously cultivated using a systematic approach.

There are many books written about each of these virtues. In this post I can only cover a brief introduction of each, and suggest some further reading. Finally, I have separated them into virtues of mind and heart only for the sake of exposition – in truth there is great overlap between both.

Let us begin by talking about the need to develop virtues holistically.

Jump to section

What is a Virtue

Balanced self-development, tranquility, virtues list, parting thoughts.

A virtue is a positive character trait that is consider a foundation for living well, and a key ingredient to greatness.

For some, the word “virtue” may have a bit of a Victorian puritanism associated with it. This is not my understanding of it, nor is this the spirit of this article.

Rather, a virtue is a personal asset , a shield to protect us from difficulty, trouble, and suffering. Each virtue is a special sort of “power” that enables us to experience a level of well-being that we wouldn’t be able to access otherwise. Indeed, “virtue”comes from the latin virtus (force, worth, power).

Let’s take the virtue of equanimity as an example.

Developing equanimity protects us from suffering through the ups and downs of life, and saves us from the pain of being criticized, wronged, or left behind. It unlocks a new level of well-being: the emotional stability of knowing we will always be ok.

The same is true for every virtue discussed in this essay.

We all have certain personal qualities more naturally developed than the others. And our tendency is often to double-down on the virtues that we already have, rather than developing complementary virtues . For instance, people who are good at self-discipline may focus on getting even better at that, and overlook the need to develop the opposing virtue of flexibility.

There is no doubt that we need to play our strengths . But when we focus solely on our strengths and use them to overcompensate our weaknesses, the result is often not good. We can become victims of our own blessings.

Let’s take the case of a person whose natural strength is compassion and kindness. In certain relationships, this might be abused by other people (directly or indirectly). Dealing with this situation by becoming kinder would not be wise. Instead, the opposing virtue of self-assertiveness (the courage of setting boundaries), is to be exercised.

Here are some other examples of virtues that are incomplete (and potentially harmful) in isolation:

- Tranquility without joy and energy is stale;

- Detachment and equanimity without love can be cold;

- Trust without wisdom can be blind;

- Morality without humility can be self-righteous;

- Love without wisdom can cause harm to oneself;

- Focus and courage without love and wisdom is just blind power.

It took me years to get to this precious insight – and I’ll probably need a lifetime to learn how to implement it. 😉

Funnily enough, afterwards I discovered that this was already a concept praised by the Stoics. In Stoicism, it is called anacoluthia , the mutual entailment of virtues.

The point is: we need to focus on our strengths, but we also need to pay attention to the virtues we lack the most. Any development in these areas, however small, has the potential to be life-changing. I go deeper into this topic here .

Have a look at your current strengths. What complementary virtues might you be overlooking?

Best Virtues of Mind

“Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage.” – Anais Nin

Related qualities: boldness, fearlessness, decisiveness, leadership, assertiveness, confidence, magnanimity.

Courage says: “The consequences of this action might be painful for me, but it’s the right thing to do. I’ll do it.”

Courage is the ability to hold on to the feeling “I need to do this”, ignore the fear mongering thoughts, and take action. For a few, it is the absence of fear; for most, it’s the willingness to act despite fear.

Examples: It takes courage to expose yourself, to try something new, to change directions, to take a risk, to let go of an attachment, to say “I was wrong”, to have a difficult conversation, to trust yourself. Its manifestations are many, both in small and big things in life.

Without courage we feel powerless. Because we know what we want to do, or what we need to do, but we lack the boldness to take action. We default to the easy way out, the path of least resistance. It might feel comfortable now, but in the long term it doesn’t make us happy.

Recommended book: Daring Greatly (Brené Brown)

“The more tranquil a man becomes, the greater his success, his influence, his power for good. Calmness of mind is one of the beautiful jewels of wisdom.” – James Allen

Related qualities: serenity, calmness, non-reactivity, gentleness, peace, acceptance.

Tranquility says: “There is no need to stress. All is well.”

Tranquility involves keeping your mind and heart calm, like the ocean’s depth. You take your time to perceive what’s going on and act purposefully, without agitation, without hurry, and without overreacting. On a deeper level, it means to diminish rumination, worries, and useless thinking.

Examples: Taking a deep breath before answering an email or phone call, or before responding to the hurtful behavior of someone else. Being ok with the fact that things are often not going to go as we expect. Not brooding about the past or worrying too much about the future. Shunning busyness in favor of a more purposeful living. Not living in fight-or-flight mode.

Without tranquility we expend more energy than what’s really needed. We experience a constant feeling of stress, anxiety, or agitation in the back of our minds. And sometimes we may be fooling ourselves thinking we are being “active” or “productive”.

Recommended book: The Path to Tranquility (Dalai Lama)

“Success is going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm.” -Winston Churchill

Related qualities: energy, enthusiasm, passion, vitality, zeal, perseverance, willpower, determination, discipline, self-control, resolution, mindfulness, steadfastness, tenacity, grit.

Diligence says: “I am committed to this work / habit / path. I will continue it no matter what , even in the face of challenges, discouragement, and tiredness.”

Some may say that it is the most essential virtue for success in any field – career, art, sports or business. It is about making a decision once, in something that is good for you, and then keeping it up despite adversities and mood fluctuations.

Examples: Deciding to stop smoking and never again lighting acigarette. Deciding that I will meditate every day and keeping that up, like a perfect habit chain. Showing up to train / study / work in your passion project day after day, regardless of how you feel. Always getting up as soon as you fall. Having an unbreakable, almost stubborn, determination. Treating challenges like energy bars.

Without diligence we can’t accomplish anything meaningful. We can’t properly take care of our health, finances, mind, or relationships. We give up on everything too soon. We can’t create good habits, break bad habits, or manifest the things we want in our lives. We are a victim of circumstances, social/familial conditioning, and genetics.

Recommended books: The Willpower Instinct (Kelly McGonigal), Grit (Angela Duckworth), Power of Habit (Charles Duhhig)

“The powers of the mind are like the rays of the sun – when they are concentrated they illumine.” – Swami Vivekananda

Related qualities: concentration, one-pointedness, depth, contemplation, essentialism, meditation, orderliness.

Focus says: “I will ignore distractions, ignore the thousand different trivial things, and put all my energy in the most important thing. I will keep going deeper into what really matters. I can tame my own mind.”

Focus, the ability to control your attention, is the core skill of meditation . It involves bringing your mind, moment after moment, to dwell where you want it to dwell, rather than being pulled by the gravity of all the noise going on inside and outside of you.

Examples: Bringing your mind again and again to your breathing or mantra , during meditation. Cutting down on social media, TV and gossip. Learning to say “no” to 90% of good opportunities, so you can say yes to the 10% of great opportunities. Staying on your chosen path and not chasing the next shiny thing.

Without focus our energy is dissipated and our progress in any field is limited (like moving one mile in ten directions, rather than ten miles in a single direction). Focus, together with motivation and diligence, is a type of fire, and as such it needs to be balanced with more water-like virtues.

Recommended book: Essentialism (Greg McKeown)

“Happy is the man who can endure the highest and lowest fortune. He who has endured such vicissitudes with equanimity has deprived misfortune of its power.” – Seneca the Younger

Related qualities: balance, temperance, patience, forbearance, tolerance, acceptance, resilience, fortitude.

Equanimity says: “In highs and lows, victory and defeat, pleasure and pain, gain or loss – I keep evenness of temper. Nothing can mess me up.”

It is the ability to accept the present moment without emotional reaction, without agitation. It’s being unfuckwithable , imperturbable.

Examples: Not going into despair when we miss an opportunity, or lose some money. Not feeling elated when praised, or discouraged when criticized. Not taking offense from other people. Not indulging in emotional reactions to gain or loss, whatever shape they take. Being modest in success, and gracious in defeat.

Without equanimity , life is an emotional roller-coaster. We are attached to the highs, which brings pain because they are short-lived. And we are uncomfortable (perhaps even fearful) with the lows – which also brings pain, because they can’t be fully avoided.

Recommended book: Letters from a Stoic (Seneca), Dhammapada (Buddha)

“A great man is always willing to be little.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

Related qualities: modesty, humbleness, discretion, egolessness, lack of conceit, simplicity, prudence, respect.

Humility says: “There are many things that I don’t know. Every person I meet is my teacher in something.”

Humility is letting go of the desire to feel superior to other people, either by means of wealth, fame, intelligence, beauty, titles, or influence. It’s about not comparing yourself with others, to be either superior or inferior. In the words of C.S. Lewis, True humility is not about thinking less of yourself; it is thinking of yourself less . In the deepest sense, humility is about transcending the ego.

This virtue is especially needed for overachievers and “successful people”.

Examples: Accepting your own mistakes. Learning to see virtue and good in others. Not dwelling on vanity and feelings of inflated self-importance. Being genuinely happy with other people’s successes. Accepting the uncertainty of life, and how small we are.

Without humility , we live stuck in an ego trap which prevents us from growing beyond the confines of our self-interests, and also poisons our relationships.

Recommended books: Ego is the Enemy (Ryan Holiday), Humility: An Unlikely Biography of America’s Greatest Virtue

“Always do what is right. It will gratify half of mankind and astound the other.” – Mark Twain

Related qualities: character, justice, honor, truthfulness, sincerity, honesty, responsibility, reliability, morality, righteousness, ethics, idealism, loyalty, dignity.

Integrity says: “I will do what is right, according to my conscience, even if nobody is looking. I will choose thoughts and words based on my values, not on personal gains. I will be radically honest and authentic, with myself and others.”

Like many virtues, integrity is about choosing what is best , rather than what is easy . It invites us to resist instant gratification in favor of a higher type of satisfaction – that of doing the right thing. It’s not about being moralistic, but about being congruent to our own conscience and values, in all our actions.

Examples: Refusing to distort the truth in order to gain personal benefits. Sticking to our words. Acting as though all our real intentions were publicly visible by others. Letting go of the “but I can get away with it” thinking. Not promising what you know you cannot fulfill.

Without integrity , we are not perceived as trustable or genuine. We make decisions that favor a short term gain but are likely to bring disastrous consequences in the long run.

Recommended books: Lying (Sam Harris), Yoga Morality (Georg Feuerstein)

“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom” – Aristotle

Related qualities: intelligence, discernment, insight, understanding, knowledge, transcendence, perspective, discrimination, contemplation, investigation, clarity, vision.

Wisdom says: “Let me contemplate deeply on this. Let me understand it from the inside out. Let me know myself.”

Unlike the other virtues listed so far, wisdom it is not something that you can directly practice. Rather, it is the result of contemplation, introspection, study, and experience. It unveils the other virtues, informs them, and makes their practice easier. It points out the truth behind the surface, and the connection among things.

Without wisdom , we don’t really know what we are doing. Life is small, often confusing, and there might be a sense of purposelessness.

Recommended books: This depends on your taste for traditional and philosophy ( here is my list). Or you can also join my Practical Wisdom Newsletter .

Best Virtues of Heart

“You have to trust in something – your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever.” – Steve Jobs

Related qualities: optimism, faith, openness, devotion, hope.

Trust says: “There is something larger than me. Life flows better when I trust resources larger than my own, and when I see purpose in random events.”

Trust is not a whimsical expectation that things will happen according to your preference; but rather a faith that things will happen in favor of your greater good. As Tony Robbins says, it is the attitude that life is happening for you , not to you .

Examples: Not dwelling on negative interpretations of what has happened in your life. Trusting that there is something good to be learned or gained from any situation. Having the feeling that if you keep true to your path, things will eventually work out ok.

Without trust , life can feel lonely, scary, or unfair. You are on your own, in the midst of random events, in a cold and careless universe.

Recommended book: Radical Acceptance (Tara Brach)

“Remain cheerful, for nothing destructivecan piece through the solid wall of cheerfulness.” – Sri Chinmoy

Related qualities: contentment, cheerfulness, satisfaction, gratitude, humor, appreciation.

Joy says: “I am cheerful, content, happy, and grateful. There is always something good in anything that happens. I feel well in my own skin, without depending on anything else.”

The disposition for joy is something that can be consciously cultivated. It is often the result of good vitality in the body, peace of mind, and an attitude of appreciation. It is also a natural consequence of a deep meditation practice , and the letting go of clinging.

Examples: Feeling good as a result of the positive states you have cultivated in your body (health), mind (peace), and heart (gratitude).

Without joy we are unhappy, cranky, gloomy, pessimistic, bored, neurotic.

Recommended books: The How of Happiness (Sonja Lyubomirsky), The Book of Joy (Dalai Lama et ali)

“The tighter you squeeze, the less you have.” – Zen Saying

Related qualities: dispassion, non-attachment, forgiveness, letting go, moderation, flexibility, frugality.

Detachment says: “I interact with things, I experience things, but I do not own them. Everything passes. I can let them be, and let them go.”

Learning how to let go is one of the most important things in overcoming suffering. It doesn’t mean that we live life less intensely; rather, we do what we are called to do with zest, and then we step back and watch what happens, without anxiety. It doesn’t mean we don’t love, play, work, or seek with intensity; but rather that we are detached from the results, knowing that we have full control only over the effort we make.

At the deepest level, detachment is a disillusionment with external desires and goals, and there is the realization that the only reliable source of happiness is internal. It also involves not holding onto any particular state.

Examples: Not being anxious about what the future brings. Letting go when things need to go. “Opening the hand” of your mind and allowing things to flow as they will. Having the feeling of not needing anything .

Without detachment, we suffer loss again and again. We can be manipulated. The mind is an open field for worries, fear, and insecurity.

Recommended books: Letting Go (David R. Hawkins), Everything Arises, Everything Falls Away (Ajahn Chah)

Check also my online course on the topic: Letting Go, Letting Be .

“The more you lose yourself in something bigger than yourself, the more energy you will have.” – Norman Vincent Peale

Related qualities: love, compassion, friendliness, service, generosity, sacrifice, selflessness, cooperation, nonviolence, consideration, tact, sensitivity.

Kindness says: “I feel others as myself, and take pleasure in doing good for them, in giving and serving. I wish everyone well. The well-being of others is my well-being.”

Kindness and related virtues (love, compassion, consideration) is the core “social virtue”. It invites us to expand our sense of well-being to include others as well. It gives us the ability to put ourselves in another person’s shoes, and feel what they feel as if it is happening to us, and if appropriate do something about it. The result is the experience of the “helper’s high”, a mix of dopamine and oxytocin.

At it’s most basic level, this virtue tell us to do unto others as you would have them do unto you . At the deepest level, it says “We are all one”.

Examples: Offering a word of encouragement or advice. Listening without judgment. Helping someone in need, directly or indirectly. Teaching. Assuming the best in others. Volunteering. Doing something for someone who can never repay you.

Without kindness , we cannot build any true human connection, and we fail to experience a happiness that is larger than ourself.

Recommended books: The Power of Kindness (Pierro Ferrucci), Awakening Loving-Kindness (Pema Chodron)

Here is the full list of virtues. The ones that are very similar are grouped together.

- Acceptance. Letting go.

- Contentment. Joyfulness.

- Confidence. Boldness. Courage. Assertiveness.

- Forgiveness. Magnanimity. Clemency.

- Honesty. Authenticity. Truthfulness. Sincerity. Integrity.

- Kindness. Generosity. Compassion. Empathy. Friendliness.

- Loyalty. Trustworthiness. Reliability.

- Perseverance. Determination. Purposefulness. Tenacity.

- Willpower. Self-control. Fortitude. Self-discipline.

- Loyalty. Commitment. Responsibility.

- Caringness. Consideration. Support. Service.

- Cooperation. Unity.

- Humility. Simplicity.

- Creativity. Imagination.

- Detachment.

- Wisdom. Thoughtfulness. Insight.

- Dignity. Honor. Respect.

- Energy. Motivation. Zest. Enthusiasm. Passion.

- Resilience. Grit. Tolerance. Patience.

- Excellence.

- Orderliness. Purity. Clarity.

- Prudence. Awareness. Tactfulness. Preparedness.

- Temperance. Balance. Moderation.

- Justice. Fairness.

- Trust. Faith. Hope. Optimism.

- Calmnes. Serenity. Centeredness. Peace.

- Grace. Elegance. Gentleness.

- Flexibility. Adaptability.

Developing these virtues is a life-long process. We’ll probably never be perfect at them. But the more we cultivate them, the better our life becomes. And, chances are, simply reading about these virtues has already enlivened them in you.

One simple way of cultivating these virtues is to focus on a single virtue each week (or month), and look daily for opportunities to put that chosen quality into practice. Keep asking yourself throughout the day, “What does it mean to be [virtue]?”

However, if you want to develop them more systematically, with practical exercises and support, consider joining my Intermediate Meditation Course . In this online program, besides learning 10 different types of meditation, you will find lessons focused on developing 10 different character strengths/virtues.

Another option is to work in person with me as your coach .

Every step taken on developing these virtues is valuable. By developing them we grow as a person, expand our awareness, and have better tools to live a happy and meaningful life.

Spread Meditation:

- ← Previous post

- Next Post →

Related Posts

Shifting from anxious living to fearless living, optimism, gratitude, and contentment as a solution to anxiety 🙏🏻🙃😌, anxiety feeds on itself… but so does courage 😉💪🏻.

Become Calm, Centered, Focused.

Make the world a better place, one mind at a time.

Copyrights @ 2019 All Rights Reserved

Essays About Values: 5 Essay Examples Plus 10 Prompts

Similar to how our values guide us, let this guide with essays about values and writing prompts help you write your essay.

Values are the core principles that guide the actions we take and the choices we make. They are the cornerstones of our identity. On a community or organizational level, values are the moral code that every member must embrace to live harmoniously and work together towards shared goals.

We acquire our values from different sources such as parents, mentors, friends, cultures, and experiences. All of these build on one another — some rejected as we see fit — for us to form our perception of our values and what will lead us to a happy and fulfilled life.

5 Essay Examples

1. what today’s classrooms can learn from ancient cultures by linda flanagan, 2. stand out to your hiring panel with a personal value statement by maggie wooll, 3. make your values mean something by patrick m. lencioni, 4. how greed outstripped need by beth azar, 5. a shift in american family values is fueling estrangement by joshua coleman, 1. my core values, 2. how my upbringing shaped my values, 3. values of today’s youth, 4. values of a good friend, 5. an experience that shaped your values, 6. remembering our values when innovating, 7. important values of school culture, 8. books that influenced your values, 9. religious faith and moral values, 10. schwartz’s theory of basic values.

“Connectedness is another core value among Maya families, and teachers seek to cultivate it… While many American teachers also value relationships with their students, that effort is undermined by the competitive environment seen in many Western classrooms.”

Ancient communities keep their traditions and values of a hands-off approach to raising their kids. They also preserve their hunter-gatherer mindsets and others that help their kids gain patience, initiative, a sense of connectedness, and other qualities that make a helpful child.

“How do you align with the company’s mission and add to its culture? Because it contains such vital information, your personal value statement should stand out on your resume or in your application package.”

Want to rise above other candidates in the jobs market? Then always highlight your value statement. A personal value statement should be short but still, capture the aspirations and values of the company. The essay provides an example of a captivating value statement and tips for crafting one.

“Values can set a company apart from the competition by clarifying its identity and serving as a rallying point for employees. But coming up with strong values—and sticking to them—requires real guts.”

Along with the mission and vision, clear values should dictate a company’s strategic goals. However, several CEOs still needed help to grasp organizational values fully. The essay offers a direction in setting these values and impresses on readers the necessity to preserve them at all costs.

“‘He compared the values held by people in countries with more competitive forms of capitalism with the values of folks in countries that have a more cooperative style of capitalism… These countries rely more on strategic cooperation… rather than relying mostly on free-market competition as the United States does.”

The form of capitalism we have created today has shaped our high value for material happiness. In this process, psychologists said we have allowed our moral and ethical values to drift away from us for greed to take over. You can also check out these essays about utopia .

“From the adult child’s perspective, there might be much to gain from an estrangement: the liberation from those perceived as hurtful or oppressive, the claiming of authority in a relationship, and the sense of control over which people to keep in one’s life. For the mother or father, there is little benefit when their child cuts off contact.”

It is most challenging when the bonds between parent and child weaken in later years. Psychologists have been navigating this problem among modern families, which is not an easy conflict to resolve. It requires both parties to give their best in humbling themselves and understanding their loved ones, no matter how divergent their values are.

10 Writing Prompts On Essays About Values

For this topic prompt, contemplate your non-negotiable core values and why you strive to observe them at all costs. For example, you might value honesty and integrity above all else. Expound on why cultivating fundamental values leads to a happy and meaningful life. Finally, ponder other values you would like to gain for your future self. Write down how you have been practicing to adopt these aspired values.

Many of our values may have been instilled in us during childhood. This essay discusses the essential values you gained from your parents or teachers while growing up. Expound on their importance in helping you flourish in your adult years. Then, offer recommendations on what households, schools, or communities can do to ensure that more young people adopt these values.

Is today’s youth lacking essential values, or is there simply a shift in what values generations uphold? Strive to answer this and write down the healthy values that are emerging and dying. Then think of ways society can preserve healthy values while doing away with bad ones. Of course, this change will always start at home, so also encourage parents, as role models, to be mindful of their words, actions and behavior.

The greatest gift in life is friendship. In this essay, enumerate the top values a friend should have. You may use your best friend as an example. Then, cite the best traits your best friend has that have influenced you to be a better version of yourself. Finally, expound on how these values can effectively sustain a healthy friendship in the long term.

We all have that one defining experience that has forever changed how we see life and the values we hold dear. Describe yours through storytelling with the help of our storytelling guide . This experience may involve a decision, a conversation you had with someone, or a speech you heard at an event.

With today’s innovation, scientists can make positive changes happen. But can we truly exercise our values when we fiddle with new technologies whose full extent of positive and adverse effects we do not yet understand such as AI? Contemplate this question and look into existing regulations on how we curb the creation or use of technologies that go against our values. Finally, assess these rules’ effectiveness and other options society has.

Highlight a school’s role in honing a person’s values. Then, look into the different aspects of your school’s culture. Identify which best practices distinct in your school are helping students develop their values. You could consider whether your teachers exhibit themselves as admirable role models or specific parts of the curriculum that help you build good character.

In this essay, recommend your readers to pick up your favorite books, particularly those that served as pathways to enlightening insights and values. To start, provide a summary of the book’s story. It would be better if you could do so without revealing too much to avoid spoiling your readers’ experience. Then, elaborate on how you have applied the values you learned from the book.

For many, religious faith is the underlying reason for their values. For this prompt, explore further the inextricable links between religion and values. If you identify with a certain religion, share your thoughts on the values your sector subscribes to. You can also tread the more controversial path on the conflicts of religious values with socially accepted beliefs or practices, such as abortion.

Dive deeper into the ten universal values that social psychologist Shalom Schwartz came up with: power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, and security. Look into their connections and conflicts against each other. Then, pick your favorite value and explain how you relate to it the most. Also, find if value conflicts within you, as theorized by Schwartz.

Make sure to check out our round-up of the best essay checkers . If you want to use the latest grammar software, read our guide on using an AI grammar checker .

Yna Lim is a communications specialist currently focused on policy advocacy. In her eight years of writing, she has been exposed to a variety of topics, including cryptocurrency, web hosting, agriculture, marketing, intellectual property, data privacy and international trade. A former journalist in one of the top business papers in the Philippines, Yna is currently pursuing her master's degree in economics and business.

View all posts

9.4 Virtue Ethics

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the central principles of virtue ethics.

- Distinguish the major features of Confucianism.

- Evaluate Aristotle’s moral theory.

Virtue ethics takes a character-centered approach to morality. Whereas Mohists and utilitarians look to consequences to determine the rightness of an action and deontologists maintain that a right action is the one that conforms to moral rules and norms, virtue ethicists argue that right action flows from good character traits or dispositions. We become a good person, then, through the cultivation of character, self-reflection, and self-perfection.

There is often a connection between the virtuous life and the good life in virtue ethics because of its emphasis on character and self-cultivation. Through virtuous development, we realize and perfect ourselves, laying the foundation for a good life. In Justice as a Virtue , for example, Mark LeBar (2020) notes that “on the Greek eudaimonist views (including here Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, and Epicurus) our reasons for action arise from our interest in [ eudaimonia , or] a happy life.” The ancient Greeks thought the aim of life was eudaimonia . Though eudaimonia is often translated as “happiness,” it means something closer to “a flourishing life.” Confucianism , with its strong emphasis on repairing the fractured social world, connects the promotion of virtuous development and social order. Confucians believe virtuous action is informed by social roles and relationships, such that promoting virtuous development also promotes social order.

Confucianism

As discussed earlier, the Warring States period in ancient China (ca. 475–221 BCE) was a period marked by warfare, social unrest, and suffering. Warfare during this period was common because China was comprised of small states that were not politically unified. New philosophical approaches were developed to promote social harmony, peace, and a better life. This period in China’s history is also sometimes referred to as the era of the “Hundred Schools of Thought” because the development of new philosophical approaches led to cultural expansion and intellectual development. Mohism, Daoism, and Confucianism developed in ancient China during this period. Daoism and Confucianism would later spread to Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, where they would be adopted and changed in response to local social and cultural circumstances.

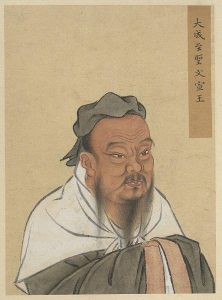

Confucius (551–479 BCE) rose from lowly positions to become a minister in the government of a province in eastern China. After a political conflict with the hereditary aristocracy, Confucius resigned his position and began traveling to other kingdoms and teaching. Confucius’s teachings centered on virtue, veering into practical subjects such as social obligations, ritual performance, and governance. During his lifetime, Confucius despaired that his advice to rulers fell on deaf ears: “How can I be like a bitter gourd that hangs from the end of a string and can not be eaten?” (Analects 17:7). He did not foresee that his work and ideas would influence society, politics, and culture in East Asia for over 2000 years.

Confucius is credited with authoring or editing the classical texts that became the curriculum of the imperial exams, which applicants had to pass to obtain positions in government. His words, sayings, and exchanges with rulers and his disciples were written down and recorded in the Lun Yu , or the Analects of Confucius , which has heavily influenced the moral and social practice in China and elsewhere.

Relational Aspect of Virtue

Like Mohism, Confucianism aimed to restore social order and harmony by establishing moral and social norms. Confucius believed the way to achieve this was through an ordered, hierarchical society in which people know their place in relationship to other people. Confucius said, “There is government, when the prince is prince, and the minister is minister; when the father is father, and the son is son” (Analects, 7:11). In Confucianism, relationships and social roles shape moral responsibilities and structure moral life.

A cornerstone of Confucian virtue is filial piety . Confucius felt that the role of the father was to care for and educate his son, but the duty of the son must be to respect his father by obediently abiding by his wishes. “While a man's father is alive, look at the bent of his will; when his father is dead, look at his conduct. If for three years he does not alter from the way of his father, he may be called filial” (Analects, 1:11). Indeed, when the Duke of Sheh informed Confucius that his subjects were so truthful that if their father stole a sheep, they would bear witness to it, Confucius replied, “Among us, in our part of the country, those who are upright are different from this. The father conceals the misconduct of the son, and the son conceals the misconduct of the father. Uprightness is to be found in this.” The devotion of the son to the father is more important than what Kant would call the universal moral law of truth telling.

There is therefore an important relational aspect of virtue that a moral person must understand. The virtuous person must not only be aware of and care for others but must understand the “human dance,” or the complex practices and relationships that we participate in and that define social life (Wong 2021). The more we begin to understand the “human dance,” the more we grasp how we relate to one another and how social roles and relationships must be accounted for to act virtuously.

Ritual and Ren

Important to both early and late Confucian ethics is the concept of li (ritual and practice). Li plays an important role in the transformation of character. These rituals are a guide or become a means by which we develop and start to understand our moral responsibilities. Sacrificial offerings to parents and other ancestors after their death, for example, cultivate filial piety. By carrying out rituals, we transform our character and become more sensitive to the complexities of human interaction and social life.

In later Confucian thought, the concept of li takes on a broader role and denotes the customs and practices that are a blueprint for many kinds of respectful behavior (Wong 2021). In this way, it relates to ren , a concept that refers to someone with complete virtue or specific virtues needed to achieve moral excellence. Confucians maintain that it is possible to perfect human nature through personal development and transformation. They believe society will improve if people abide by moral and social norms and focus on perfecting themselves. The aim is to live according to the dao . The word dao means “way” in the sense of a road or path of virtue.

Junzi and Self-Perfection

Confucius used the term junzi to refer to an exemplary figure who lives according to the dao . This figure is an ethical ideal that reminds us that self-perfection can be achieved through practice, self-transformation, and a deep understanding of social relationships and norms. A junzi knows what is right and chooses it, taking into account social roles and norms, while serving as a role model. Whenever we act, our actions are observed by others. If we act morally and strive to embody the ethical ideal, we can become an example for others to follow, someone they can look to and emulate.

The Ethical Ruler

Any person of any status can become a junzi . Yet, it was particularly important that rulers strive toward this ideal because their subjects would then follow this ideal. When the ruler Chi K’ang consulted with Confucius about what to do about the number of thieves in his domain, Confucius responded, “If you, sir, were not covetous, although you should reward them to do it, they would not steal” (Analects, 7:18).

Confucius thought social problems were rooted in the elite’s behavior and, in particular, in their pursuit of their own benefit to the detriment of the people. Hence, government officials must model personal integrity, understand the needs of the communities over which they exercised authority, and place the welfare of the people over and above their own (Koller 2007, 204).

In adherence to the ethical code, a ruler’s subjects must show obedience to honorable people and emulate those higher up in the social hierarchy. Chi K’ang, responding to Confucius’s suggestion regarding thievery, asked Confucius, “What do you say to killing the unprincipled for the good of the principled?” Confucius replied that there was no need to kill at all. “Let your evinced desires be for what is good, and the people will be good.” Confucius believed that the relationship between rulers and their subjects is and should be like that between the wind and the grass. “The grass must bend, when the wind blows across it” (Analects, 7:19).

Japanese Confucianism

Although Confucianism was initially developed in China, it spread to Japan in the mid-sixth century, via Korea, and developed its own unique attributes. Confucianism is one of the dominant philosophical teachings in Japan. As in China, Japanese Confucianism focuses on teaching individual perfection and moral development, fostering harmonious and healthy familial relations, and promoting a functioning and prosperous society. In Japan, Confucianism has been changed and transformed in response to local social and cultural factors. For example, Confucianism and Buddhism were introduced around the same time in Japan. It is therefore not uncommon to find variations of Japanese Confucianism that integrate ideas and beliefs from Buddhism. Some neo-Confucian philosophers like Zhu Xi, for example, developed “Confucian thinking after earlier study and practice of Chan Buddhism” (Tucker 2018).

Aristotelianism

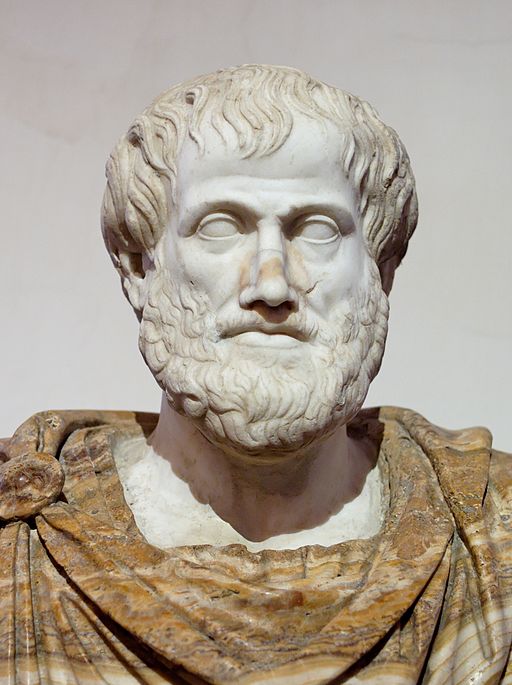

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was a preeminent ancient Greek philosopher. He studied with Plato (ca. 429–347 BCE) at the Academy , a fraternal organization where participants pursued knowledge and self-development. After Plato’s death, Aristotle traveled, tutored the boy who would later become Alexander the Great, and among other things, established his own place of learning, dedicated to the god Apollo (Shields 2020).

Aristotle spent his life in the pursuit of knowledge and wisdom. His extant works today represent only a portion of his total life’s work, much of which was lost to history. During his life, Aristotle was, for example, principal to the creation of logic, created the first system of classification for animals, and wrote on diverse topics of philosophical interest. Along with his teacher, Plato, Aristotle is considered one of the pillars of Western philosophy.

Human Flourishing as the Goal of Human Action

In the first line of Book I of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics , he observes that “[every] art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1094a). If everything we do aims at some good, he argues, then there must be a final or highest good that is the end of all action (life’s telos ), which is eudaimonia , the flourishing life (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1097a34–b25). Everything else we pursue is pursued for the sake of this end.

Connections

See the chapter on epistemology for more on the topic of eudaimonia .

Nicomachean Ethics is a practical exploration of the flourishing life and how to live it. Aristotle, like other ancient Greek and Roman philosophers (e.g., Plato and the Stoics), asserts that virtuous development is central to human flourishing. Virtue (or aretê ) means “excellence. We determine something’s virtue, Aristotle argued, by identifying its peculiar function or purpose because “the good and the ‘well’ is thought to reside in the function” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1097b25–1098a15). We might reasonably say, for example, that a knife’s function is to cut. A sharp knife that cuts extremely well is an excellent (or virtuous) knife. The sharp knife realizes its function and embodies excellence (or it is an excellent representation of knife-ness).

Aristotle assumed our rational capacity makes us distinct from other (living) things. He identifies rationality as the unique function of human beings and says that human virtue, or excellence, is therefore realized through the development or perfection of reason. For Aristotle, virtuous development is the transformation and perfection of character in accordance with reason. While most thinkers (like Aristotle and Kant) assign similar significance to reason, it is interesting to note how they arrive at such different theories.

Deliberation, Practical Wisdom, and Character

To exercise or possess virtue is to demonstrate excellent character. For ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, the pursuit of intentional, directed self-development to cultivate virtues is the pursuit of excellence. Someone with a virtuous character is consistent, firm, self-controlled, and well-off. Aristotle characterized the virtuous character state as the mean between two vice states, deficiency and excess. He thought each person naturally tends toward one of the extreme (or vice) states. We cultivate virtue when we bring our character into alignment with the “mean or intermediate state with regard to” feelings and actions, and in doing so we become “well off in relation to our feelings and actions” (Homiak 2019).

Being virtuous requires more than simply developing a habit or character trait. An individual must voluntarily choose the right action, the virtuous state; know why they chose it; and do so from a consistent, firm character. To voluntarily choose virtue requires reflection, self-awareness, and deliberation. Virtuous actions, Aristotle claims, should “accord with the correct reason” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1103b30). The virtuous person chooses what is right after deliberation that is informed by practical wisdom and experience. Through a deliberative process we identify the choice that is consistent with the mean state.

The Role of Habit

Aristotle proposed that humans “are made perfect by habit” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1103a10–33). Habit therefore plays an important role in our virtuous development. When we practice doing what’s right, we get better at choosing the right action in different circumstances. Through habituation we gain practice and familiarity, we bring about dispositions or tendencies, and we gain the requisite practical experience to identify the reasons why a certain action should be chosen in diverse situations. Habit, in short, allows us to gain important practical experience and a certain familiarity with choosing and doing the right thing. The more we reinforce doing the right thing, the more we grow accustomed to recognizing what’s right in different circumstances. Through habit we become more aware of which action is supported by reason and why, and get better at choosing it.

Habit and repetition develop dispositions. In Nicomachean Ethics , for example, Aristotle reminds us of the importance of upbringing. A good upbringing will promote the formation of positive dispositions, making one’s tendencies closer to the mean state. A bad upbringing, in contrast, will promote the formation of negative dispositions, making one’s tendencies farther from the mean state (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1095b5).

Read Like a Philosopher

Artistotle on virtue.

Read this passage from from Book II of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics , considering what Aristotle means when he states that moral virtues come about as a result of habit. How should individuals make use of the two types of virtue to become virtuous?

Virtue, then, being of two kinds, intellectual and moral, intellectual virtue in the main owes both its birth and its growth to teaching (for which reason it requires experience and time), while moral virtue comes about as a result of habit, whence also its name (ethike) is one that is formed by a slight variation from the word ethos (habit). From this it is also plain that none of the moral virtues arises in us by nature; for nothing that exists by nature can form a habit contrary to its nature. For instance, the stone which by nature moves downwards cannot be habituated to move upwards, not even if one tries to train it by throwing it up ten thousand times; nor can fire be habituated to move downwards, nor can anything else that by nature behaves in one way be trained to behave in another. Neither by nature, then, nor contrary to nature do the virtues arise in us; rather we are adapted by nature to receive them, and are made perfect by habit. Again, of all the things that come to us by nature we first acquire the potentiality and later exhibit the activity (this is plain in the case of the senses; for it was not by often seeing or often hearing that we got these senses, but on the contrary we had them before we used them, and did not come to have them by using them); but the virtues we get by first exercising them, as also happens in the case of the arts as well. For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g. men become builders by building and lyreplayers by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts. This is confirmed by what happens in states; for legislators make the citizens good by forming habits in them, and this is the wish of every legislator, and those who do not effect it miss their mark, and it is in this that a good constitution differs from a bad one. Again, it is from the same causes and by the same means that every virtue is both produced and destroyed, and similarly every art; for it is from playing the lyre that both good and bad lyreplayers are produced. And the corresponding statement is true of builders and of all the rest; men will be good or bad builders as a result of building well or badly. For if this were not so, there would have been no need of a teacher, but all men would have been born good or bad at their craft. This, then, is the case with the virtues also; by doing the acts that we do in our transactions with other men we become just or unjust, and by doing the acts that we do in the presence of danger, and being habituated to feel fear or confidence, we become brave or cowardly. The same is true of appetites and feelings of anger; some men become temperate and good-tempered, others self-indulgent and irascible, by behaving in one way or the other in the appropriate circumstances. Thus, in one word, states of character arise out of like activities. This is why the activities we exhibit must be of a certain kind; it is because the states of character correspond to the differences between these. It makes no small difference, then, whether we form habits of one kind or of another from our very youth; it makes a very great difference, or rather all the difference.

Social Relationships and Friendship

Aristotle was careful to note in Nicomachean Ethics that virtuous development alone does not make a flourishing life, though it is central to it. In addition to virtuous development, Aristotle thought things like success, friendships, and other external goods contributed to eudaimonia .

In Nicomachean Ethics , Aristotle points out that humans are social (or political) beings (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1097b10). It’s not surprising, then, that, like Confucius, Aristotle thinks social relations are important for our rational and virtuous development.

When we interact with others who have common goals and interests, we are more likely to progress and realize our rational powers. Social relations afford us opportunities to learn, practice, and engage in rational pursuits with other people. The ancient Greek schools (e.g., Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum , and Epicurus’s Gardens) exemplify the ways individuals benefit from social relations. These ancient schools offered a meeting place where those interested in knowledge and the pursuit of wisdom could participate in these activities together.

Through social relations, we also develop an important sense of community and take an interest in the flourishing of others. We see ourselves as connected to others, and through our interactions we develop social virtues like generosity and friendliness (Homiak 2019). Moreover, as we develop social virtues and gain a deeper understanding of the reasons why what is right, is right, we realize that an individual’s ability to flourish and thrive is improved when the community flourishes. Social relations and political friendships are useful for increasing the amount of good we can do for the community (Kraut 2018).

The important role Aristotle assigns to friendship in a flourishing life is evidenced by the fact that he devotes two out of the ten books of Nicomachean Ethics (Books VIII and IX) to a discussion of it. He notes that it would be odd, “when one assigns all good things to the happy man, not to assign friends, who are thought the greatest of external goods” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1169a35–b20). Aristotle distinguishes between incidental friendships and perfect friendships . Incidental friendships are based on and defined by either utility or pleasure. Such friendships are casual relationships where each person participates only because they get something (utility or pleasure) from it. These friendships neither contribute to our happiness nor do they foster virtuous development.

Unlike incidental friendships, perfect friendships are relationships that foster and strengthen our virtuous development. The love that binds a perfect friendship is based on the good or on the goodness of the characters of the individuals involved. Aristotle believed that perfect friends wish each other well simply because they love each other and want each other to do well, not because they expect something (utility or pleasure) from the other. He points out that “those who wish well to their friends for their sake are most truly friends” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1156a27–b17). Aristotle argues that the happy man needs (true) friends because such friendships make it possible for them to “contemplate worthy [or virtuous] actions and actions that are [their] own” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1169b20–1170a6). This affords the good individual the opportunity to contemplate worthy actions that are not their own (i.e., they are their friend’s) while still thinking of these actions as in some sense being their own because their friend is another self. On Aristotle’s account, we see a true friend as another self because we are truly invested in our friend’s life and “we ought to wish what is good for his sake” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1155b17–1156a5).

Perfect friendships afford us opportunities to grow and develop, to better ourselves—something we do not get from other relationships. Aristotle therefore argues that a “certain training in virtue arises also from the company of the good” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1170a6–30). Our perfect friend provides perspective that helps us in our development and contributes to our happiness because we get to participate in and experience our friend’s happiness as our own. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that Aristotle considered true friends “the greatest of external goods” (Aristotle [350 BCE] 1998, 1169a35–b20).

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Nathan Smith

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Philosophy

- Publication date: Jun 15, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/9-4-virtue-ethics

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 How Can I Be a Better Person? On Virtue Ethics

Douglas Giles

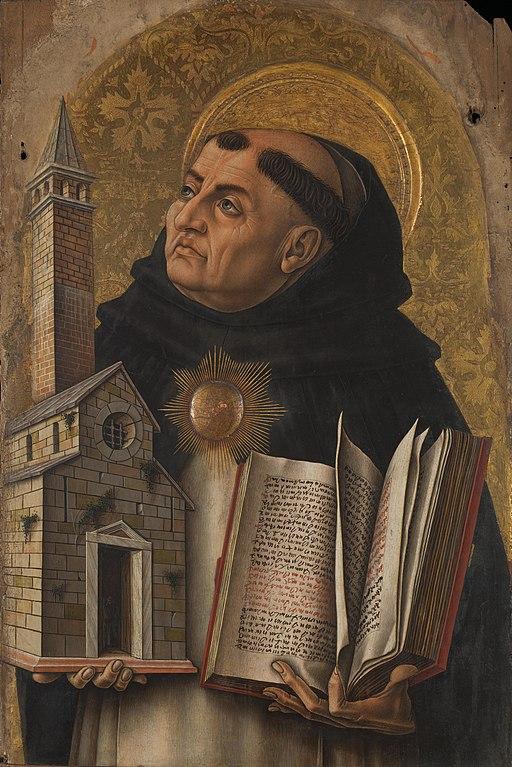

This chapter explores a variety of approaches to the question of moral virtue and what it means to be a good person. It examines four ethical systems that revolve around the concept of virtue: Aristotle’s virtue ethics, Aquinas’s Christian version of Aristotelian virtue ethics, Buddhist virtue ethics, and Daoist and Confucian virtue ethics. Each will be presented as a different way of understanding what it might mean to live as a good person. For Aristotle, this is to be understood in terms of striving for the mean between extremes in the context of a well-ordered political community. For Aquinas, it is to be understood within the context of Christianity and natural law. For Buddhism, virtue is understood in terms of a life oriented toward the eightfold path that leads to the end of suffering. For Chinese philosophy, both Daoist and Confucian, virtue means being in harmony with the Cosmic Dao.

What is Virtue Ethics?

In philosophies of virtue ethics, rather than an emphasis on following rules, the emphasis is on developing oneself as a good person. It is not that following rules is not important; it is more the sense that being ethical means more than simply following the rules. For example, given an opportunity to donate to a charity, deontologists (see Chapter 6 ) would consider whether there is an ethical rule that required them to donate. Utilitarians (see Chapter 5 ) would consider whether a donation would produce better consequences if they donated than if they did not. Virtue ethicists would consider whether donating is the kind of action that a virtuous person would do. Another example would be deciding whether to lie or tell the truth. Rather than focus on rules or consequences, virtue ethicists ask what kind of person do they want to be: honest or dishonest? Virtue ethicists place more importance on being a person who is honest, trustworthy, generous and other virtues that lead to a good life, and place less importance on one’s ethical duty or obligations. A common theme among virtue ethicists is stressing the importance of cultivating ethical values in order to increase human happiness. Businesses today increasingly incorporate virtue ethics in their work culture, often having a “statement of values” guiding their operations.

Because the right ethical action depends on the particularities of individual people and their particular situations, virtue ethics links goodness with wisdom because virtue is knowing how to make ethical decisions rather than knowing a list of general ethical rules that will not apply to every circumstance. Virtue ethicists tend to reject the view that ethical theory should provide a set of commands that dictate what we should do on all occasions. Instead, virtue ethicists advocate the cultivation of wisdom and character that people can use to internalize basic ethical principles from which they can determine the ethical course of action in particular situations. Virtue ethicists tend to see ethical principles as being inherent in the world and as being discoverable by means of rational reflection and disciplined living. The different forms of virtue ethics may or may not focus on God as the ultimate source of ethical principles. What unites the various forms of virtue ethics is the focus on moral education to cultivate moral wisdom, discernment, and character in the belief that ethical virtue will manifest in ethical actions.

Aristotle on Excellence and Flourishing

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) believed that to understand something we need to understand its nature and proper function (see Chapter 2 ). He also believed that everything has an end, or goal, toward which it naturally moves. For example, a seed grows into a tree because the purpose and function of the seed is to grow into a tree. Objects fulfill their purpose, not out of conscious desire, but because it is in their nature to fulfill their functions. Aristotle believed that our purpose is to pursue our proper human end, eud ai monia , which is best understood as human flourishing or living well. Eud ai monia is not momentary pleasure but enduring contentment—not just a good day but a good life. Aristotle said that one swallow does not make a summer, and so, too, one day does not make one blessed and happy. It is human nature to move toward eudaimonia and this is the purpose, function, or final goal ( telos ) of all human activity. We work to make money, to make a home, and we sacrifice to improve our future, all with the ultimate aim of living well.

Human flourishing means acting in ways that cause your essential human nature to achieve its most excellent form of expression. Aristotle held that a good life of lasting contentment can be gained only by a life of virtue—a life lived with both phrónesis , or “practical wisdom,” and aretē , or “excellence.” Aristotle defines human good as the activity of the soul in accordance with virtue, and wrote in the Nicomachean Ethics that

we take the characteristic activity of a human being to be a certain kind of life; and if we take this kind of life to be activity of the soul and actions in accordance with reason, and the characteristic activity of the good person to be to carry this out well and nobly, and a characteristic activity to be accomplished well when it is accomplished in accordance with the appropriate virtue; then if this is so, the human good turns out to be activity of the soul in accordance with virtue. (1.7) [1]

The ethical demand on us is to develop our character to become a person of excellent ethical wisdom because, from that excellence, good actions will flow, leading to a good life. Virtuous actions come from a virtuous person; therefore, it is wise to focus on being a virtuous person.