The influence of rumination and distraction on depressed and anxious mood: a prospective examination of the response styles theory in children and adolescents

- Original Contribution

- Published: 05 May 2009

- Volume 18 , pages 635–642, ( 2009 )

Cite this article

- Jeffrey Roelofs 1 ,

- Lea Rood 1 ,

- Cor Meesters 1 ,

- Valérie te Dorsthorst 1 ,

- Susan Bögels 2 ,

- Lauren B. Alloy 3 &

- Susan Nolen-Hoeksema 4

2045 Accesses

79 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The present study sought to test predictions of the response styles theory in a sample of children and adolescents. More specifically, a ratio approach to response styles was utilized to examine the effects on residual change scores in depression and anxiety. Participants completed a battery of questionnaires including measures of rumination, distraction, depression, and anxiety at baseline (Time 1) and 8–10 weeks follow-up (Time 2). Results showed that the ratio score of rumination and distraction was significantly associated with depressed and anxious symptoms over time. More specifically, individuals who have a greater tendency to ruminate compared to distracting themselves have increases in depression and anxiety scores over time, whereas those who have a greater tendency to engage in distraction compared to rumination have decreases in depression and anxiety symptoms over time. These findings indicate that a ratio approach can be used to examine the relation between response styles and symptoms of depression and anxiety in non-clinical children and adolescents. Implications of the results may be that engaging in distractive activities should be promoted and that ruminative thinking should be targeted in juvenile depression treatment.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

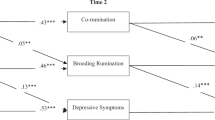

Co-Rumination and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence: Prospective Associations and the Mediating Role of Brooding Rumination

How do Rumination and Social Problem Solving Intensify Depression? A Longitudinal Study

The role of executive functioning in adolescent rumination and depression.

The association between depression (CDI) and anxiety (STAI-C) was relatively high, possibly threatening the discriminant validity of the scales. To deal with this issue, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis on items of the CDI and the STAI-C in order to obtain relatively pure depression and anxiety factors (see [7]). Items with salient double loadings (i.e., >0.30) were removed. In total, 18 out of 20 STAI-C items and 22 out of 27 CDI items were retained. The correlation coefficient between the reduced scales was 0.65 indicating less overlap. All analyses were conducted for the original scales as well as for the reduced scales. Similar results were found for the original and reduced scales. Therefore, the original scales were used in all analyses in order to be able to compare our findings to previous research.

Abela JRZ, Aydin CM, Auerbach RP (2007) Responses to depression in children: reconceptualizing the relation among response styles. J Abnormal Child Psychol 35:913–927

Article Google Scholar

Abela JRZ, Brozina K, de Haigh EP (2002) An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: a short-term longitudinal study. J Abnormal Child Psychol 30:515–527

Abela JRZ, Hankin BL (2008) Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: a developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL (eds) Childhood and adolescent depression: causes treatment and prevention. Guilford Press, New York, pp 35–78

Google Scholar

Abela JRZ, Vanderbilt E, Rochon A (2004) A test of the integration of the response styles theory and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. J Soc Clin Psychol 5:653–674

Abbott MJ, Rapee RM (2004) Post-event rumination and negative self-appraisal in social phobia and after treatment. J Abnorm Psychol 113:136–144

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bagby RM, Rector NA, Bacchiochi JR, McBride C (2004) The stability of the response styles questionnaire rumination scale in a sample of patients with major depression. Cogn Ther Res 28:527–538

Bieling PJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP (1998) The state-trait anxiety inventory, trait version: structure and content re-examined. Behav Res Ther 36:777–788

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Blagden JC, Craske MG (1996) Effects of active and passive rumination and distraction: a pilot replication with anxious mood. J Anx Dis 10:243–252

Bögels SM (2006) Task concentration training versus applied relaxation, in combination with cognitive therapy, for social phobia patients with fear of blushing, trembling, and sweating. Behav Res Ther 44:1199–1210

Bögels SM, Mansell W (2004) Attention processes in the maintenance and treatment of social phobia: hypervigilance, avoidance and self-focused attention. Clin Psychol Rev 24:827–856

Burwell RA, Shirk SR (2007) Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and coping. J Clin Child Adolescent Psychol 36:56–65

Chang EC (2004) Distinguishing between ruminative and distractive responses in dysphoric college students: does indication of past depression make a difference? Pers Individ Diff 36:845–855

Ciarrochi J, Scott G, Deane F, Heaven P (2003) Relations between social and emotional competence and mental health: a construct validation study. Pers Individ Diff 35:1947–1963

Ciesla JA, Roberts JE (2002) Self-directed thought and response to treatment for depression: a preliminary investigation. J Cogn Psychother 16:435–453

Comer JS, Kendall PC (2004) A symptom-level examination of parent–child agreement in the diagnosis of anxious youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:878–886

Cox BJ, Enns MW, Walker JR, Kjernisted K, Pidlubny SR (2001) Psychological vulnerability in patients with major depression versus panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 39:567–573

Driscoll KA (2004) Children’s response styles and risk for depression and anxiety: developmental and sex differences. Unpublished Dissertation, Florida State University

Finch AJ Jr, Montgomery L, Deardorff P (1974) Reliability of state-trait anxiety with emotionally disturbed children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2:67–69

Flett GL, Madorsky D, Hewitt PL, Heisel MJ (2002) Perfectionism cognitions, rumination, and psychological distress. J Ration Emotive Cogn Behav Ther 20:33–47

Fresco DM, Frankel AN, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG (2002) Distinct and overlapping features of rumination and worry: the relationship of cognitive production to negative affective states. Cogn Ther Res 26:179–188

Harrington JA, Blankenship V (2002) Ruminative thoughts and their relation to depression and anxiety. J Applied Soc Psychol 32:465–485

Harvey A, Watkins E, Mansell W, Shafran R (2004) Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: a transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG (2003) Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behaviour change. Guilford, New York

Hilt LM, Cha CB, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2008) Non-suicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: moderators of the distress–function relationship. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:63–71

Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, Addis ME, Koermer K, Gollan JK, Gortner E, Prince SE (1996) A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 64:295–304

Jacobson NS, Martell CR, Dimidjian S (2001) Behavioral activation treatment for depression: returning to contextual roots. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 8:255–270

Just N, Alloy LB (1997) The response styles theory of depression: tests and an extension of the theory. J Abnorm Psychol 106:221–229

Kocovski NL, Endler NS, Rector NA, Flett GL (2005) Ruminative coping and post-event processing in social anxiety. Behav Res Ther 43:971–984

Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory, CDI. Manual. Multi-Health Systems Inc., Toronto (Ontario)

Kuehner C, Weber I (1999) Responses to depression in unipolar depressed patients: an investigation of Nolen-Hoeksema’s response styles theory. Psychol Med 29:1323–1333

Lam D, Smith S, Checkley S, Rijsdijk F, Sham P (2003) Effect of neuroticism, response style and information processing on depression severity in a clinically depressed sample. Psychol Med 33:469–479

Lara ME, Klein DN, Kasch KL (2000) Psychosocial predictors of the short-term course and outcome of major depression: a longitudinal study of a nonclinical sample with recent-onset episodes. J Abnorm Psychol 109:644–650

Lewinsohn PM, Antonuccio DO, Breckenridge JS, Teri L (1984) The coping with depression course. Eugene, OR, Castalia

Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S (1993) Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. J Pers Soc Psychol 65:339–349

Lyubomirsky S, Tucker KL, Caldwell ND, Berg K (1999) Why ruminators are poor problem solvers: clues from the phenomenology of dysphoric rumination. J Pers Soc Psychol 77:1041–1060

Miranda R, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2007) Brooding and reflection: rumination predicts suicidality at one-year follow up in a community sample. Behav Res Ther 45:3088–3095

Morrow J, Nolen-Hoeksema S (1990) Effects of responses to depression on the remediation of depressive affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 58:519–527

Muris P, Roelofs J, Meesters C, Boomsma P (2004) Rumination and worry in nonclinical adolescents. Cogn Ther Res 28:539–554

Muris P, Roelofs J, Rassin E, Franken I, Mayer B (2005) Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety, and depression. Pers Individ Diff 39:1105–1111

Muris P, Fokke M, Kwik D (2009) The ruminative response style in adolescents: an examination of its specific link to symptoms of depression. Cogn Ther Res 33:21–32

Nolen-Hoeksema S (1987) Sex differences in unipolar depression: evidence and theory. Psychol Bull 101:259–282

Nolen-Hoeksema S (1991) Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol 100:569–582

Nolen-Hoeksema S (1998) Ruminative coping with depression. In: Heckhausen J, Dweck CS (eds) Motivation and self-regulation across the life span. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 237–256

Nolen-Hoeksema S (2000) The role of rumination in depressive disorder and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol 109:504–511

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS (1994) The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull 115:424–443

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrell ZA (2002) Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: tests of gender differences. J Cogn Psychother 16:391–403

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J (1991) A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol 61:115–121

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J (1993) Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cogn Emot 7:561–570

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C (2007) Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 116:198–207

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S (2008) Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci 3:400–424

Papageorgiou C, Wells A (2004) Depressive rumination: nature, theory and treatment. Wiley, Chichester

Robinson LA, Alloy LB (2003) Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: a prospective study. Cogn Ther Res 27:275–292

Schwartz JAJ, Koenig LJ (1996) Response styles and negative affect among adolescents. Cogn Ther Res 20:13–36

Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD (2002) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford, New York

Segerstrom SC, Tsao JCI, Alden LE, Craske MG (2000) Worry and rumination: repetitive thought as a concomitant and predictor of negative mood. Cogn Ther Res 24:671–688

Smith JM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY (2006) Cognitive vulnerability to depression, rumination, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: Multiple pathways to self-injurious thinking. Suicide Life Threat Behav 36:443–454

Spasojevic J, Alloy LB (2001) Rumination as a common mechanism relating depressive risk factors to depression. Emotion 1:25–37

Spielberger CD (1973) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory for children. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Vaus D (2001) Research designs in social research. Sage Publications Ltd, London

Vickers KS, Vogeltanz-Holm ND (2003) The effects of rumination and distraction tasks on psychophysiological responses and mood in dysphoric and nondysphoric individuals. Cogn Ther Res 27:331–348

Ward A, Lyubomirsky S, Sousa L, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2003) Can’t quite commit: rumination and uncertainty. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 29:96–107

Watkins E (2004) Appraisals and strategies associated with rumination and worry. Pers Individ Diff 37:679–694

Wood JV, Saltzberg JA, Neale JM, Stone AA, Rachmiel TB (1990) Self-focused attention, coping responses, and distressed mood in everyday life. J Pers Soc Psychol 58:1027–1036

Ziegert DI, Kistner JA (2002) Response styles theory: downward extension to children. J Clin Child Adolescent Psychol 31:325–334

Download references

Acknowledgments

The contribution of Jeffrey Roelofs was supported by the NWO Social Sciences Research Council of The Netherlands, Grant No. 451-05-019.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Clinical Psychological Science, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Jeffrey Roelofs, Lea Rood, Cor Meesters & Valérie te Dorsthorst

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Susan Bögels

Temple University, Philadelphia, USA

Lauren B. Alloy

Yale University, New Haven, USA

Susan Nolen-Hoeksema

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeffrey Roelofs .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Roelofs, J., Rood, L., Meesters, C. et al. The influence of rumination and distraction on depressed and anxious mood: a prospective examination of the response styles theory in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 18 , 635–642 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0026-7

Download citation

Received : 19 October 2008

Accepted : 15 April 2009

Published : 05 May 2009

Issue Date : October 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0026-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adolescents

- Distraction

- Response styles theory

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Modeling and estimating the feedback mechanisms among depression, rumination, and stressors in adolescents

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Grado Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, United States of America

Roles Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States of America, Division of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, College of Medicine, Michigan State University, Grand Rapids, MI, United States of America

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States of America

Roles Software, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- Niyousha Hosseinichimeh,

- Andrea K. Wittenborn,

- Jennifer Rick,

- Mohammad S. Jalali,

- Hazhir Rahmandad

- Published: September 27, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389

- Reader Comments

The systemic interactions among depressive symptoms, rumination, and stress are important to understanding depression but have not yet been quantified. In this article, we present a system dynamics simulation model of depression that captures the reciprocal relationships among stressors, rumination, and depression. Building on the response styles theory, this model formalizes three interdependent mechanisms: 1) Rumination contributes to ‘keeping stressors alive’; 2) Rumination has a direct impact on depressive symptoms; and 3) Both ‘stressors kept alive’ and current depressive symptoms contribute to rumination. The strength of these mechanisms is estimated using data from 661 adolescents (353 girls and 308 boys) from two middle schools (grades 6–8). These estimates indicate that rumination contributes to depression by keeping stressors ‘alive’—and the individual activated—even after the stressor has ended. This mechanism is stronger among girls than boys, increasing their vulnerability to a rumination reinforcing loop. Different profiles of depression emerge over time depending on initial levels of depressive symptoms, rumination, and stressors as well as the occurrence rate for stressors; levels of rumination and occurrence of stressors are stronger contributors to long-term depression. Our systems model is a steppingstone towards a more comprehensive understanding of depression in which reinforcing feedback mechanisms play a significant role. Future research is needed to expand this simulation model to incorporate other drivers of depression and provide a more holistic tool for studying depression.

Citation: Hosseinichimeh N, Wittenborn AK, Rick J, Jalali MS, Rahmandad H (2018) Modeling and estimating the feedback mechanisms among depression, rumination, and stressors in adolescents. PLoS ONE 13(9): e0204389. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389

Editor: Iratxe Puebla, Public Library of Science, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: January 6, 2017; Accepted: September 7, 2018; Published: September 27, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Hosseinichimeh et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Authors of this manuscript do not own the data. A researcher at the University of Washington, Dr. Kate McLaughlin, shared the data with us. Data are available from the following study whose author may be contacted at [email protected] : MCLAUGHLIN, K. A. & NOLEN-HOEKSEMA, S. (2012). Interpersonal Stress Generation as a Mechanism Linking Rumination to Internalizing Symptoms in Early Adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 41, 584-97.

Funding: This article was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health award R21MH100515. AW obtained the funding. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Major depressive disorder is a systemic syndrome [ 1 ]. Previous research has identified multiple interactions among depressive symptoms, rumination, and stressful events. Response styles theory [ 2 , 3 ] defines rumination as repetitively and passively focusing on symptoms of distress and the causes and consequences of the symptoms without actively engaging in coping or problem-solving. Rumination is a robust predictor of the onset of depression in children [ 4 ], adolescents [ 5 ], and adults [ 6 ]. Stress caused by difficult life events increases an individual’s vulnerability to rumination and depression [ 5 , 7 ]. On the other hand, multiple studies have indicated that the interaction of stress and rumination predicts both onset and severity of depression [ 8 – 11 ]. In addition, recent studies have found that rumination moderates the association between stress and depression [ 5 , 12 , 13 ]. While research supports a link between stress and rumination, less is known about how these processes unfold over time and how their interactions contribute to depression.

Ruscio and colleagues suggested three potential pathways for the link between rumination, stress, and depression [ 14 ]. First, rumination after stressful events may lead to the negative affect that is an important feature of mood disorders. Second, rumination may cause dysfunctional behaviors such as reduced activity or withdrawal that worsen depressive symptoms. Third, rumination might worsen the effects of past stressors by “keeping the stressor ‘alive’—and the individual activated—even after the stressor has ended” [ 14 ]. Using ecological momentary assessment in which data were collected from participants multiple times per day, Ruscio and colleagues examined the first two pathways and found that rumination mediated the association between stress and depressive symptoms. They also found that individuals with major depressive disorder were more likely to ruminate in response to stressors than individuals with no psychopathology. The third pathway was not tested. Nolen-Hoeksema and colleagues examined the reciprocal relationship between rumination and depression without including stressors in the model [ 15 ]. They showed that a higher rumination score predicted elevated depressive symptoms in the next year and depressive symptoms predicted a significant increase in ruminative style over time.

Other variables can influence the relationship between rumination and depression. For instance, rumination was found to mediate the relationship between cognitive control and depressive symptoms [ 16 ]. Rumination also mediates the relation between trait anger and depression. In other words, individuals prone to experience more anger might become depressed in situations under which they tend to ruminate [ 17 , 18 ]. Co-rumination, or ruminating with peers, was found to moderate the relationship between stress and depression [ 12 ]. Those with high levels of co-rumination are more likely to activate negative schemas, which in turn increases depressive symptoms [ 19 ]. Stress may contribute to depression through other pathways, including biological mechanisms such as HPA axis dysfunction [ 20 – 22 ] and inflammation [ 23 , 24 ].

The complex feedback mechanisms among the drivers of major depressive disorder call for methods that can both estimate multiple interactions and synthesize existing evidence [ 25 ]. System dynamics provides one such methodology which has provided important insights in health research on diabetes [ 26 , 27 ], heart disease [ 28 ], and post-traumatic stress disorder [ 29 ], among others. System dynamics has also been used for qualitatively capturing feedback processes underlying depression [ 1 ], but these feedback mechanisms have not been quantified.

In this study, we use system dynamics to develop a simulation model of depression based on the response styles theory [ 15 ]. We model and estimate the interactions among rumination, depressive symptoms, and stressors that have been hypothesized in prior research. While many other feedback mechanisms could be included in a comprehensive model of depression, we limit our focus to these interactions because they have strong theoretical support, and data for estimating these interactions exists. Moreover, few prior studies capture even this level of complexity, so in contributing to a cumulative science of depression we hope our study can act as a steppingstone but not as a final comprehensive model; such a comprehensive model, if ever feasible, can only come after many smaller and more modest models are developed, estimated, refined, and combined.

A novel estimation method, documented in a previous methodological article [ 30 ], was used for calibrating the model. Results inform the strength of various mechanisms and reinforcing loops relevant to depression. In addition, we estimate the mean time that a stressor is kept active (i.e., the time a person is activated by the stressor, which provides an estimate for the duration of a stressor’s impact in the absence of any intervention) for boys and girls, finding a significant asymmetry. We then simulate the model for 32 unique profiles of individuals to better understand individual variations depending on initial conditions of individuals and their exposure to stressors.

The present study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, prior studies have not estimated the endogenous relationships between stress, rumination, and depression simultaneously; instead, they have investigated the bidirectional relationship between either rumination and depression [ 31 ] or stress and depression [ 7 , 32 ]. Second, this study examines the hypothesis of Ruscio and colleagues, which asserts that rumination prolongs the effects of stressful events by keeping an individual activated [ 14 ]. Our major contribution lies in capturing this untested mechanism in our dynamic model and estimating its impact in interaction with rumination and depressive symptoms. Third, this study is the first to use system dynamics to quantify feedback mechanisms involved in depression and offers a template for developing other individual-level simulation models of depression.

A system dynamics model of interactions between depressive symptoms, rumination, and stress was developed and estimated based on data from a longitudinal study of adolescent mental health carried out by McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema [ 33 ]. Below we briefly summarize the empirical data. Then, given the novelty of the use of system dynamics in this context, we provide a brief background on the approach and then discuss the simulation model and estimation approach in more detail.

Participants

The participants were 1,057 adolescents from two middle schools (Grades 6–8) in central Connecticut. Students in the self-contained special education classrooms and technical programs who were not present in the school for the majority of the day were excluded. The racial/ethnic characteristics of the sample were: 56.9% (N = 610) Hispanic/Latino, 13.2% (N = 141) non-Hispanic White, 11.8% (N = 126) non-Hispanic Black, 9.3% (N = 100) biracial/multiracial, 2.2% (N = 24) Asian/Pacific Islander, 0.8% (N = 9) Middle Eastern, 0.2% (N = 2) Native American, and 4.2% (N = 45) other racial/ethnic groups. Based on the school records, 62.3% of the students qualified for free or reduced lunch. The per capita income of the community where the two schools were located is $18,404, which is considered a low socioeconomic status community. We excluded participants with missing values and the final sample includes 661 individuals. Twenty-eight percent of participants (N = 221) in the baseline assessment did not complete the assessment at Time 2, and 20.4% (N = 217) did not complete the assessment at Time 3. Attrition was primarily related to leaving the school district. From 2000 to 2004, 22.7% of students had left the school district [ 34 ]. Those who did not complete the second and third assessments did not differ from the participants in the first assessment in terms of grade level, race/ethnicity, or being from a single-parent household ( ps > 0.10). However, they were more likely to be female ( χ 2 (1) = 6.85, p < 0.01). The level of rumination and depression of those who did not complete at least one of the follow-up assessments did not differ from those who completed all assessments ( ps > 0.10).

Instruments

Data were collected over a span of seven months. The following instruments were used to measure stressful life events (at times 1 and 3), rumination levels (at times 1, 2 and 3), and depressive symptoms (at times 1 and 3). The time between the first and second assessments was four months, and there were three months between the second and third assessments.

Stressful life events.

The Life Events Scale for Children [ 35 ] contains 25 examples of stressful life events. Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced any of the events in the past six months (e.g., “Your parents got divorced” and “You got suspended from school”). The test-retest reliability of this measure over a 2-week period is high [ 36 , 37 ].

Rumination.

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; [ 4 ]) measures the level of rumination, distraction, and problem-solving in response to sad feelings. This measure was modeled after the Response Styles Questionnaire [ 2 ], which was developed for adults. The CRSQ is composed of 25 items that are grouped into three scales: 1) Ruminative Response subscale, 2) Distracting Response subscale, and 3) Problem-Solving subscale. In the present study, only the Ruminative Response subscale was used. For each item, children are asked to identify how often they respond a certain way when they feel sad ( almost never = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3, or almost always = 4). The Ruminative Response subscale (CRSQ-Rumination) includes 13 items and generates a score between 13 and 52. Sample items include “Think about how alone you feel,” “Think about a recent situation wishing it had gone better,” and “Think why can’t I handle things better?” Previous studies reported good reliabilities for the CRSQ-Rumination subscale [ 4 ]. In this sample, the subscale was reliable ( α = 0.86).

Depressive symptoms.

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) includes 27 items that evaluate the presence and severity of depression in children and adolescents [ 38 ]. Each item includes three statements from which the respondents chose the one that best describes them in the past two weeks (e.g., “I am sad once in a while,” “I am sad many times,” and “I am sad all the time”). The item related to suicide was removed at the request of the human subjects committee and school officials. Adding the remaining 26 items generates a score that ranges from 0 to 52. The CDI exhibited good reliability in this sample ( α = 0.82).

System dynamics modeling

System dynamics is a methodological approach for understanding the structure and analyzing the dynamics of complex systems [ 39 ]. System dynamics allows for quantifying nonlinear and reciprocal influences among variables, making it an appropriate tool when endogenous feedback is important for understanding a phenomenon. In addition, system dynamics accounts for accumulations (sources of inertia) and the speed of change in states of a system. For instance, a system dynamics model of depression and rumination takes into account the reciprocal relationship (i.e., feedback loop) between the two variables such that rumination increases depressive symptoms, and more depressive symptoms lead to a higher level of rumination. In addition, system dynamics incorporates the speed of change in inertial factors. For instance, rumination does not develop overnight. It accumulates over time and its inertia influences the dynamics of depressive symptoms.

Mathematically, typical system dynamics models consist of a system of ordinary differential equations, potentially influenced by exogenous and/or random inputs, and can be simulated to track the results of different assumed model structures and parameters. Statistical estimation of these models makes it possible to identify the strength of hypothesized causal pathways based on observed data. The development of a system dynamics model is an iterative process and often involves the following steps. First, the problem that specifies the phenomenon to be explained is articulated. Second, a theory or set of dynamic hypotheses about potential causes of the problem are specified. Third, key variables, including sources of inertia (i.e., accumulation or stock variables), are identified. Fourth, a causal diagram that maps the causal relationships among the variables is developed by reviewing the literature and consulting experts and policymakers. Fifth, the model is formulated, refined, and estimated until it is robust, reliable and able to replicate historical data. The refinement process is iterative and involves various tests to build confidence in the model [ 40 – 42 ]. Finally, different scenarios and policies are formulated and the model is simulated to identify high-leverage policies [ 39 ].

Our motivation for using system dynamics in this research is based on three distinct benefits that this methodology can bring to the study of depression. First, depression is a complex and persistent problem, not caused by a ‘common cause,’ and as a result, a ‘causal systems perspective’ is needed to analyze the disorder [ 43 , 44 ]. A system dynamics approach allows for explicitly capturing the multiple feedback mechanisms, latent variables, and accumulations relevant to understanding depression. While structural equation models and simultaneous equation estimation can partially accommodate feedback and latent variables, system dynamics models incorporate all of these and allow for potential nonlinearities among variables. Second, these models are simulated in continuous time, enabling us to separate the actual unfolding of events (which is continuous in time) from the discrete measurements used for estimation. For instance, depressive symptoms of diverse patients can be simulated continuously over time to examine their symptom trajectories under different conditions. Finally, by accommodating more realistic mechanisms and broader feedback mechanisms, these simulation models can provide input into intervention analysis and design.

Developing and estimating a model of depression

We developed a system dynamics simulation model of depression that simultaneously captured the bidirectional relationships among depressive symptoms, rumination, and stressors at the individual level. Our model included two major feedback loops that are based on the mechanisms proposed by Ruscio and colleagues [ 14 ], depicted in reinforcing feedback loop 1 ( Fig 1 , loop R1: ‘Rumination’), and the response styles theory [ 15 ], illustrated in reinforcing feedback loop 2 ( Fig 1 , loop R2: ‘Symptom Exacerbation’). These two feedback loops are self-reinforcing such that an initial change in the loop comes back to cause a further change in the same direction—e.g., an initial increase will cause a further increase. Feedback loop R1 captures the idea that after experiencing a stressor, an individual prone to rumination spends time ruminating about the stressful events, keeping those stressors active, increasing the chances of even more rumination. In other words, rumination intensifies sensitivity to stressors by keeping a person activated and the stressor “alive” [ 14 ]. This leads to more rumination and depressive symptoms. Feedback loop R2 hypothesizes that more rumination leads to more depressive symptoms, and a higher level of depressive symptoms causes even more rumination [ 31 ]. It should be noted that feedback loops R1 and R2 are interconnected (see Fig 1 ). This is important because, similar to any other complex system, the interaction between the feedback loops in the model gives rise to other potential dynamics—we discuss these dynamics further in the results section.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Boxed variables represent stocks (or states), and double arrows with valves depict flows into/out of the stocks. Single-line arrows present hypothesized causal relationships—their strength is estimated below. A stock variable, which is mathematically represented as an integral, is the accumulation of the difference between its inflows and outflows.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.g001

Stressors that contribute to rumination and subsequent depression are those that happened in the past but still keep an individual activated; as a result, they are modeled as a stock variable—a boxed variable named ‘ past stressors kept alive ’ in Fig 1 . A stock variable accumulates units (e.g., patients, materials, information) and mathematically is the accumulation of the difference between its inflows and outflows (represented as double arrows with valves in Fig 1 ). A bathtub offers a simple example of a stock variable with one inflow and one outflow. The level of water depends on the initial level of water in the tub and its net flow (i.e., the level of water in the bathtub increases when the inflow is larger than the outflow). The same argument applies to the stock of past stressors kept alive . The level of past stressors kept alive depends on the initial level of stressors (i.e., prior stressors ) and the net flow of stressors ( past stressors kept alive increases if ongoing stressors is greater than ‘ let it go’ ). Let it go resembles the drain of the bathtub and is a function of memory time and past stressors kept alive ( let it go equals past stressors kept alive divided by memory time ). Memory time captures how fast an individual comes to terms with past stressors, and is formulated as the product of rumination and a parameter estimated in the calibration process (θ 9 , with the estimated value of 1.47). The higher the rumination level, the greater the memory time and the lower the let it go flow. As let it go declines, past stressors accumulate in the stock of past stressors kept alive , which increases the level of rumination even further (Reinforcing loop R1). Detailed formulations of the model are available in S1 File Appendix, and the results section provides more details.

This model is estimated using the indirect inference method [ 45 , 46 ]. In this method, sources of stochastic environmental variations (i.e., process noise) are added to the model. The parameters of the model and the environmental factors are then estimated to match the aggregate auxiliary statistics of empirical data. Indirect inference is specifically suitable for estimating complex models with intractable likelihood functions. The online S1 File Appendix provides the details for the model formulations and the indirect inference estimation method. Additional details on the development of the simulation model and estimation method are discussed in [ 30 ]. For parameter estimation, we used the dataset of 661 adolescents collected by McLaughlin and Nolen-Hoeksema [ 33 ] that is summarized in the methods section.

Table 1 summarizes the means and standard deviations for all measures at each assessment time for all participants ( N = 661), as well as separately for boys ( N = 308) and girls ( N = 353). Girls reported higher levels of rumination at all evaluation times ( p = 0.00) and more symptoms of depression at Time 1 ( p = 0.03) and Time 3 ( p = 0.08). There was no gender difference in terms of experiencing stressful life events at Time 1 ( p = 0.98) and Time 3 ( p = 0.27).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.t001

Table 2 reports the parameters of the estimated model [ 30 ]. In interpreting the results, it is important to note that one cannot claim empirical causality for any of the discussed relationships, given the observational nature of the data. On the other hand, once a simulation model is quantified, it is possible to run synthetic controlled experiments and discuss causality within the simulation results. In the results description, the use of causal language is only intended to apply to the estimated simulation model. The gender coefficient (θ 3 ) is significant, which implies that girls ruminate more than boys. The effect of stress on rumination (θ 4 ) and the effect of rumination on memory time (θ 9 ) are also significant, indicating that rumination increases sensitivity to stressful events by keeping the person activated and the stressor active. The effect of rumination on depression (θ 7 ) is significant, while the effect of depression on rumination (θ 2 ) is positive but not significant at a 95% confidence level. Overall, these results provide strong support for the Rumination reinforcing loop, moderate evidence for the Symptom Exacerbation loop, and a significant gender effect in rumination rates.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.t002

Average memory time for adolescents with different characteristics

In this section, we report the average memory time (i.e., the time it takes to release a stressor) for all participants by gender (first row in Table 3 ) and for depressed individuals with high and low rumination by gender (second and third row in Table 3 ), given the estimated strength of the Rumination loop. As discussed in the methods section, memory time is defined based on the pathway hypothesized by Ruscio and colleagues, in which rumination exacerbates the effect of stressors by keeping stressors active. Memory time captures the time over which an individual releases a stressor and is proportional to rumination (i.e., memory time equals rumination multiplied by a parameter, θ 9 , with the estimated value of 1.47). The higher the rumination level, the greater the memory time , and the longer it takes the stressors to leave the stock of past stressors kept alive ( Fig 1 ). We separately report average memory time of depressed patients (i.e., those with depressive symptoms above the cut-off value of 16 [ 47 ]) with high or low rumination (i.e., for individuals above/below mean rumination) because memory time is a function of rumination. A single value of θ 9 (reported in Table 2 ) is estimated for all participants, while rumination varies across individuals. Simulated memory time is calculated for each individual and averaged over the study time horizon. We then calculate the average memory time for each category reported in Table 3 by gender. The table shows that, on average, it takes more time for girls to release a stressor (11.7 months) compared to boys (6.8 months) (first row in Table 3 ). This effect is driven by the higher gain for the Rumination reinforcing loop, R1, for girls. This loop is stronger in girls because they are estimated to have a higher baseline rumination tendency (θ 3 >0), so are more likely to see an increase in rumination, which sustains the stressful memories (i.e., increases memory time), leading to even more rumination. For those depressed individuals starting the study with high levels of rumination, both reinforcing loops remain active throughout the study period, and thus they all have long memory times regardless of gender (second row of Table 3 ). However, the stronger R1 loop can distinguish among depressed individuals starting the study with low levels of rumination: the lower strength of R1 increases the chance for boys to reduce rumination, and memory time, compared to girls (third row of Table 3 ). In sum, the gender effect in rumination means that girls may sustain stressful memories for longer ( Fig 2 ), and as a result, have a higher risk of depression given the same external stressful events.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.t003

Trajectories of depressive symptoms by characteristics of participants

What are the implications of this estimated model for individual trajectories of depression? Individuals vary on many factors, including their initial state (i.e., level of active stressors, rumination, and depressive symptoms) and rate of exposure to stressors over time. An important question is how such individual-level variations manifest themselves in the long-term trajectories of depression. We can better appreciate the resulting variations using controlled simulation experiments. Therefore, we explore different potential trajectories by creating individual profiles varying across five parameters of the model: initial value of rumination, initial value of depressive symptoms, gender, prior stressors (i.e., the initial value of past stressors kept alive in Fig 1 ), and ongoing stressors (i.e., inflow of past stressors kept alive in Fig 1 ). A large value for prior stressors implies that a simulated participant has experienced many stressors in the six months prior to starting the simulation, while sizable ongoing stressors indicates that stressors continue to happen in someone’s life.

We conducted a full-factorial simulation experiment varying the four factors for each gender at two levels: initial depressive symptoms, initial rumination, prior stressors, and ongoing stressors (i.e., flow of stressors). We ran the model for each of the resulting 16 boy/girl groups over 120 months. For brevity, we focus the discussion on the results for girls ( Fig 3 ) and provide the counterparts for boys in S1 Fig Appendix. In each group, we used identical inputs (reported in the last row of Fig 3 ), instead of the actual individual data, in order to conduct fully controlled simulation experiments. The inputs defining the groups reported in Fig 3 were found by adding or subtracting one standard deviation to or from the empirical means of depression and rumination to determine the high or low levels of these variables. The same calculation using two standard deviations was used to find the high levels of stressors, and zero for low levels of stressors, to avoid negative stressor values. As a result, the first eight groups had high levels of depressive symptoms at the beginning of the simulation, and the rest had low initial depressive symptoms ( Fig 3 ). Groups 1 to 4 and 9 to 12 had high initial rumination, while groups 5 to 8 and 13 to 16 had low levels of initial rumination. For instance, at the beginning of the simulation, a simulated person in group 1 had high levels of depressive symptoms and rumination. In addition, she had experienced multiple stressful events in the six months prior to the beginning of the simulation, and more stressors were happening in her life. A subject in group 2 had the same characteristics, but no more stressors were occurring in her life. As in the real world, simulated subjects also vary in the random environmental factors that influence their outcome trajectories. We captured these environmental variations as first-order auto-correlated noise terms operating on indicated rumination and depression. Thus, 2,500 subjects were simulated in each experimental group, differing only in the realization of random shocks (but not in the underlying distributions). The mean and the range enveloping 75% of simulated depression symptom trajectories over time are reported for each group. The same analysis was then repeated for boys (see S1 Fig Appendix).

D 0 , R 0 , S 0 , and SI represent initial depressive symptoms and rumination, prior stressors, and ongoing stressors, respectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.g003

Fig 4 shows the mean and the 75% envelope of the simulated depressive symptoms over 120 months for each of the 16 profiles for girls. The 75% envelope shows the range containing all individuals with depressive symptoms between the 12.5 and 87.5 percentile within each group. Note that since we used the cut-off value reported in a study by Timbremont and Braet [ 47 ], a depression score above 16 depicts clinical depression. Comparing the simulated depressive symptoms in columns 1 with 2 and columns 3 with 4 indicates the critical role of ongoing stressors in the development of depression. Those with very high ongoing stressors (columns 1 and 3) experience increasing depressive symptoms, while those with no ongoing stressors (columns 2 and 4) have declining or stable depressive symptoms. For example, groups 1 and 2 experienced the same level of stressors six months prior to the start of the simulation, and they have the same initial depressive symptoms and rumination; but, unlike group 2, the stressors continue at a high rate for those in group 1. Thus, the depressive symptoms of group 2 increase slightly in the first months and then follow a declining trend, while the depressive symptoms of group 1 continue to increase during the entire simulation. Note that it is possible for a depressive episode to continue for a long time. A 30-year study of a large clinical sample found that 8% of patients had not recovered from a depressive episode after 10 years and 6% had still not recovered after 15 years [ 48 ]. However, the severity has fluctuations over time which do not appear in the simulations for two reasons. First, we used a constant flow for external stressors, whereas actual stressors are coming and going with much fluctuation. Moreover, in Fig 4 , the fluctuations have been concealed because we are averaging over 2,500 individuals, but there are fluctuations in single simulations.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.g004

The initial increase in the depressive symptoms of group 2 is caused by previous stressors that are still present in the past stressors kept alive stock. This stock resembles a reservoir of stressful memories that is initially full. Despite the low inflow of stressful memories during simulation, the initially high levels of stressful memories keep the outflow from the reservoir low (R1), and can trigger more depressive symptoms (R2). However, once the let it go rate has depleted the stock enough, and in the absence of additional ongoing stressors , the memory time goes down, the depressive symptoms subside, and the rumination level declines as well. Unlike group 2, stressors continue to occur in the lives of individuals in group 1, thus the stressors accumulate in the stock of past stressors kept alive and the level of rumination , and subsequently depression , increases during the entire simulation. Due to the slow letting go of stressors, the simulated depressive symptoms of group 2 take more than ten years to reach equilibrium.

Prior stressors interact with the initial level of rumination to influence the initial trajectory of depressive symptoms. When both are high (groups 1, 2, 9 and 10), depressive symptoms initially grow because both the stressors stay around for longer (effect of loop R1) and the rumination increases depressive symptoms (effect of loop R2). In other words, higher initial rumination leads to lower let it go and keeps past stressors active for a longer time, which causes even higher rumination (Reinforcing loop R1 in Fig 1 ) and depression (Reinforcing loop R2 in Fig 1 ). In the simulations, the interaction between initial rumination and prior stressors is temporary, and final depressive symptoms are determined by ongoing stressors. For example, comparing group 10 (which is high on both factors) with group 12 or 14, the latter groups differ in initial trajectories but show similar final levels, largely determined by the ongoing stressors level (the same across all 3). However, long-term impacts of that interaction can be seen when high levels of initial stressors and rumination are accompanied by high ongoing stressors (groups 1 and 9); in these cases, very high final depressive symptoms emerge from the sustained slow let it go rates when depressive symptoms and rumination reinforce each other continuously. The difference between groups 9 and 1 is in the initial depressive symptoms (high in group 1, low in group 9), and is only salient in the short run (first 20 months), with limited impact on the longer-term trajectories.

Results shown in Fig 4 highlight the significant impact of ongoing stressors and rumination on depressive symptoms. However, the numbers used to generate the graphs in Fig 4 are just a few extreme combinations of the range we observed empirically. Thus, we ran a sensitivity analysis to investigate the depressive symptoms after 120 months of simulation as a function of stressor inflow (ongoing stressors) and initial rumination ( Fig 5 ). The sensitivity analysis for girls was conducted by setting the initial level of depressive symptoms and prior stressors at their mean values, 9.98 and 4.97, respectively. The contour graph presented in Fig 5 illustrates mean depressive symptoms at time 120 for different combinations of ongoing stressors and initial rumination (depressive symptoms above 16 are considered to represent depression). The horizontal and vertical dashed lines represent the means for rumination and ongoing stressors. As expected, the depressive symptoms for the average individual are well below the depression threshold. Trajectories for boys are documented in S1 Fig Appendix.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.g005

Building on the response styles theory, this study investigated two of the potential feedback mechanisms underlying depression: in the first rumination increases the memory time for stressors and in the second it reinforces depressive symptoms. The proposed mechanisms were formalized in a simulation model that was estimated using data from a longitudinal study of depression and rumination among adolescents. The results indicate that rumination contributes to depression by keeping stressors ‘alive’, which in turn stimulate more rumination. Using a simulation method, we estimated the amount of time a person was activated by a stressor. On average, girls continued to ruminate about a stressor for 12 months, while it took about 7 months for boys to release a stressor. The same level of ongoing stressors creates less depressive symptoms in boys because girls are more likely to ruminate. The simulation model illustrated that the depressive symptoms of a non-depressed adolescent reached the depressive symptoms of an initially depressed person if they both had high levels of initial rumination, had experienced prior stressors, and were exposed to more stressors during the simulation. This indicates the importance of preventive care for non-depressed individuals with a ruminative style who are exposed to stress. Moreover, comparisons of individuals with the same characteristics, except for the inflow of stressors (ongoing stressors), demonstrated the critical role of this factor in the evolution of depression. Vulnerability to past events was moderated by the level of initial rumination.

Our findings reinforce and build on past studies in several ways. We found that girls ruminate significantly more than boys. A meta-analysis of the literature on rumination with a pooled sample of 14,321 individuals showed that rumination rate is significantly higher among adult females [ 49 ]. Similar to Michl and colleagues [ 5 ], we found that rumination mediated the relationship between stressful life events and depression. In line with findings reported by Nolen-Hoeksema and coauthors [ 15 ], we showed that rumination significantly increases depression, but we found only limited support for the effect of depression on rumination (there was a positive coefficient, but it was not statistically significant). However, in contrast to the joint estimation method we used, that study separately examined whether rumination in this period predicted depressive symptoms at the next time period and whether depressive symptoms in this period predicted rumination at a later time [ 15 ].

Besides reinforcing prior findings, the proposed model contributes to the literature in distinct ways. First, unlike previous studies that investigated reciprocal relationships between either stress and depression or rumination and depression, the proposed model simultaneously captures the reciprocal relationships between stress, rumination, and depression. Second, this is the first known study to examine one of the proposed pathways through which rumination contributes to depression by keeping stressors alive, and thus a person activated. Third, this model provides an integrated model of an individual’s endogenous response to exogenous stressors, and thus can be used in future examinations on the impact of multiple factors and/or interventions on trends of depressive symptoms. In other words, the model provides a simulation environment in which the effects of interventions can be estimated. Finally, this study offers the first individual-level system dynamics model of depression and is the first steppingstone to quantify the complex interactions among drivers of the disorder. The fully documented model, according to Rahmandad and Sterman [ 50 ]‘s guidelines, is available for other researchers to replicate and build on this work.

Clinical implications

The present study highlights the importance of personalized prevention and intervention. Intervening to change the level of ongoing stressors, as well as the initial level of rumination and prior stressors, may generate diverse trends in depressive symptoms. Fast exacerbation of the symptoms for non-depressed individuals with a ruminative style who are facing stressors indicates that they may receive significant benefits from timely prevention. Since the time it takes to release a stressor is significantly different in boys and girls, gender should be one of the important determinants in tailoring treatment. By providing the full documentation of the model, we hope that practitioners can use our calibrated model for estimating the effects of interventions on depression in adolescents. For instance, one can input the initial level of depressive symptoms, initial rumination, gender, level of prior stressors, and current stressors (all measurable using standard instruments reported in this paper) of an adolescent into the model and then simulate the model for a certain time to predict the progression of depressive symptoms in the absence of interventions. Such benchmarks can then guide future assessments and adaptations of treatment plans. Also, a rumination intervention that reduces the memory time can be added to the model to examine the impact of the intervention on depressive symptoms and to determine the optimal timing and length of a treatment.

Limitations

These findings should be interpreted in light of a few important limitations. First, many complex feedback mechanisms underlie depression [ 1 ]. Environmental factors as well as social, psychological, and biological factors determine the course of depression. This study only included two interdependent cognitive mechanisms and environmental stressors. However, by focusing on adolescents we attempt to rule out the existence of some biological mechanisms such as hippocampal atrophy, which is thought to take years to develop. Future research can expand upon this model to include additional mechanisms. Second, we relied on self-report questionnaire checklists which are susceptible to bias and recall failure. Specifically, life event checklist measures are increasingly considered less effective measures of stressful events. Comparisons of interview-based and self-report methods indicate that significant differences exist between the events captured by the two methods [ 51 ]. However, a review of studies on stress in children and adolescents showed that only 2% of the 500 studies used interview-based methods for measuring stress. The self-report life event checklists have remained the most common stress measure and research using secondary data have to rely on them. As discussed in the methods section and in S2 File Appendix, we addressed some of the limitations of the life events measure by estimating the stressors that contribute to rumination using the checklist. Another data limitation is that subjects may ruminate about stressors that were not measured. In addition, the rumination measure may also capture concepts such as worrying, which is more focused on the future. Some of the model parameters were estimated at the population level; if more data were available, individual estimates could be made, providing a more nuanced understanding of heterogeneity in various response functions among individuals. Finally, every model is a simplification of reality, and as such, its implications would only hold to the extent that the assumptions built into the model structure (e.g., the response styles theory and Ruscio et al.’s third pathway) are a good representation of the situation at hand. In addition to grounding the model in well-supported theoretical constructs, we built confidence in the structure of the model by checking the level of significance of the model parameters, nevertheless, estimation of feedback-rich models of depression is novel and more research is needed to assess, expand, and realize the full potential of these methods.

The proposed model incorporates the current literature on one of the major mechanisms of depression. The results highlight the importance of individualized prevention and intervention for depression and support the idea that rumination contributes to depression by keeping stressors active.

Supporting information

S1 file. developing and calibrating a model of depression..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.s001

S2 File. Estimating the inflow of past stressors kept alive.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.s002

S1 Fig. Trajectories for male participants.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204389.s003

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kate McLaughlin for generously sharing her dataset. This research was funded by NIH/NIMH grant R21MH100515 (A.K.W., PI).

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 34. Connecticut Department of Education. Strategic school profile 2005–2006: New Britain public schools. Hartford: Connecticut Department of Education. 2006.

- 38. Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY:Multi-Health Systems. 1992.

- 39. Sterman JD. Business dynamics: systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. 1 ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 2000. 982 p.

- 42. Rahmandad H, Oliva R, Osgood ND. Analytical Methods for Dynamic Modelers. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 2015.

- 48. Keller MB, Coryell WH, Endicott J, Maser JD, Schettler PJ. Clinical guide to depression and bipolar disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.; 2013.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Effects of Rumination and Depressive Symptoms on the Prediction of Negative Attributional Style Among College Students

Cola s. l. lo.

1 Department of Psychology, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Samuel M. Y. Ho

Steven d. hollon.

2 Department of Psychology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN USA

Research on cognitive vulnerability to depression has identified negative cognitive style and rumination as distinct risk factors for depression but how rumination would influence negative cognitive style remains unclear. The present study investigated the relationship between rumination and negative attributional style and specifically tested the potential moderating effect of depressive symptoms and processing mode during rumination on activating negative attributional style. After completing the baseline measures of depressive symptoms, dysphoric affect, and negative attributional style, participants were randomly assigned to three experimental conditions: analytical self-focus, experiential self-focus, and distraction, in which the degree of self-focus and mode of processing were manipulated. A second set of mood and cognitive measures was administered afterwards. Results showed that a stronger positive relationship between negative attributional style and level of depressive symptoms was found in the analytical self-focus condition, relative to the experiential and distraction conditions. This finding suggested that processing mode in rumination interacted with depressive symptoms to predict negative attributional style.

Introduction

Cognitive theories of depression state that people have characteristic ways of understanding negative life events and that those who exhibit a dispositional negative cognitive style and dysfunctional attitudes are at greater risk for depression (Abramson et al. 1989 ; Beck 1987 ). The hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al. 1989 ) postulates that depressive symptoms are likely to occur when negative life events are attributed to stable and global causes, when they are perceived as being associated with other negative consequences in the future, and construed as implying personal deficit and worthlessness. Considerable empirical support shows that the negative cognitive style featured in the hopelessness theory, especially in interaction with stressors, predicts prospective depressive symptoms and clinically significant depressive disorders (Abramson et al. 2002 ; Hankin et al. 2004 , 2005 ; Scher et al. 2005 ).

Rumination is another cognitive risk factor for depression that has received growing attention in the literature. According to the response style theory (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991 ), rumination is defined as a mode of thinking that involves repetitively and passively focusing on one’s symptoms of depression as well as on the causes and consequences of those symptoms. The theory proposes that individuals have dispositional differences in the way they react to negative mood states and those who respond to a depressed mood by consistently engaging in rumination tend to have more persistent and severe depressive episodes. In contrast, responses that serve to distract one from depressed mood are posited to alleviate feelings of sadness. Although the original theory suggested that rumination should predict the duration of depressed mood or depressive episodes, recent evidence suggests that rumination also predicts new onsets of major depressive episodes (Just and Alloy 1997 ; Nolen-Hoeksema 2000 ; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1994 ). Experimental studies have shown that rumination (relative to distraction) intensified negative mood states, enhanced negative thinking and memory, and impaired social problem solving in dysphoric individuals (see Lyubomirsky and Tkach 2004 for a review). However, similar effects did not observe among nondysphoric individuals, suggesting that it is the combination of dysphoria and rumination that contributes to the negative outcomes in rumination (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema 1995 ).

A recent study found that negative cognitive style and rumination represent empirically distinct (albeit highly correlated) cognitive risk factors for depression (Hankin et al. 2007 ). In an attempt to conceptualize the relationship between negative cognitive style and rumination in depression, Abramson et al. ( 2002 ) proposed that cognitively vulnerable individuals should be at higher risk for engaging in rumination as their underlying negative thinking makes it very difficult to exit the self-regulatory cycle. Empirical data support that individuals who exhibit a negative cognitive style and have the tendency to ruminate would be more likely than others to have more severe depressive episodes (Alloy et al. 2000 ; Robinson and Alloy 2003 ). Besides, rumination has been found to mediate the relationship between depression and negative cognitive style, as well as dysfunctional attitudes and neuroticism, suggesting that rumination may represent a common mechanism through which a variety of risk factors affect depression (Lo et al. 2008 ; Roberts et al. 1998 ; Spasojevic and Alloy 2001 ). Along with the negative cognitive consequences of rumination that have been found in the experimental studies, rumination and negative cognitive style may be dynamically related and their relationship may be reciprocal in nature. The presence of rumination would increase the influence of negative cognition on depression and this, in turn, would increase the influence of depression on cognition in a way that a self-perpetuated cycle of cognitive–affective processing would be generated during depression (Ciesla and Roberts 2007 ; Teasdale 1999 ).

Recent evidence has suggested that the consequences of rumination could be moderated by the mode of thinking adopted in times of distress. Two distinct modes of self-focus during rumination have been identified that have distinct functional properties with respect to depression (Watkins and Moulds 2005 ; Watkins and Teasdale 2004 ). The abstract analytical processing mode is focused on evaluating higher level causes, meanings, consequences, and implications of self-experience. In contrast, the concrete experiential processing mode is focused on the lower level, specific, and direct experience of one’s thoughts, feelings, and sensations in the present moment. The theoretical rationale for this distinction comes from the reduced concreteness theory (Borkovec et al. 1998 ; Stober and Borkovec 2002 ) and the interacting cognitive subsystems theory (Teasdale 1999 ). Both these theories propose that abstract analytical processing at times of negative self-experience is maladaptive in depression since it is associated with poorer emotional processing and overgeneralization (Ganellen 1988 ; Teasdale 1999 ). The abstract analytical processing may also provide event descriptions that are less detailed and conceptual that might hinder effective problem solving.

Research findings showed that among depressed patients, an induction of analytical self-focus (the abstract analytical mode) reduced the specificity of autobiographical memory recall (Watkins and Teasdale 2001 , 2004 ), impaired social problem solving (Watkins and Moulds 2005 ), and increased endorsement of global negative self-judgments (Rimes and Watkins 2005 ) compared to experiential self-focus (the concrete experiential mode). Consistently, such differential effect was not evident among nondepressed participants, suggesting that the presence of depressive symptoms would be necessary to trigger the negative effect of rumination. These findings provide support to the mode of processing hypothesis (Watkins and Moulds 2005 ) that it is the processing mode, and not the degree of self-focus, that influences cognitive consequences in depression. However, since these studies did not include a distraction condition, it would be difficult to draw conclusions regarding the different predictions of processing mode hypothesis and the degree of self-focus hypothesis. Given that abstract analytical processing would facilitate overgeneralization, it is speculated that reliance on an abstract analytical processing mode during rumination would also amplify and intensify the underlying negative cognitive style (as featured in the hopelessness theory of depression) in individuals who are experiencing depressive symptoms.

In summary, research evidence suggests the presence of depressive symptoms and the analytical mode of processing during rumination would activate negative cognitive style. However, little research has directly investigated how these variables may act together to enhance the effect of negative cognitive style. It is important to examine the potential moderating effect directly so as to shed light on the dynamic relationship among these factors. It is also imperative to examine how these vulnerability factors interrelate in order to more fully understand the mechanisms leading to depression, and thus identify the most appropriate points for intervention and guide the development of even more efficacious treatments of depression.

The present experimental study investigated the moderating effect of depressive symptoms and the processing mode in rumination on activating negative attributional style (the negative inferences about the causes of negative events). In accordance with the processing mode hypothesis (Watkins and Moulds 2005 ), mode of processing during rumination, and not the degree of self-focus would be associated with the level of negative attributional style. In addition to manipulating the mode of processing, a distraction condition was included as a reference condition so that the differential effects of processing mode and degree of self-focus could be directly examined. It was hypothesized that the level of depressive symptoms would interact with the mode of processing in predicting negative attributional style. Specifically, it was predicted that a stronger association between depressive symptoms and negative attributional style would be found in the analytical self-focus condition (a maladaptive mode of processing) than would be found in the experiential self-focus and distraction conditions.

Participants

The participants were undergraduate students at The University of Hong Kong who participated in the study in return for research credit. The sample comprised 23 male and 49 female participants with a mean age of 19.47 (SD = 1.37). The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Psychology Department at The University of Hong Kong.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996 )

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure of depressive symptoms that possesses strong psychometric properties. The Chinese version of the BDI-II (C-BDI-II; Chinese Behavioral Sciences Society 2000 ) was used in this study. It has been reported to have strong psychometric properties and an internal consistency of .94 in a Chinese sample (Byrne et al. 2004 ). In the present sample, the coefficient alpha was .82.

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; Teasdale and Dent 1987 )

The VAS was used to measure current level of dysphoric mood. Participants rated current “in the moment” feelings of sad/depressed emotions on scales ranging from 0 (not at all sad/depressed) to 100 (extremely sad/depressed) with anchors at every 10 points along the scale.

Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ; Peterson et al. 1982 )

The ASQ is a self-report measure that assesses causal attributions for six hypothetical positive and negative events along the dimensions of internality, stability, and globality on a 7-point Likert scale. A composite negative score can be computed by averaging the values of the respondent’s responses on the six negative events to produce a score that ranges from 1 to 7. A parallel version of the ASQ comprising another six hypothetical negative events, matched in length and content to the ASQ, was adapted from the expanded attributional style questionnaire (EASQ; Peterson and Villanova 1988 ). These two parallel versions of the ASQ were used as repeated measures of negative attributional style and were counterbalanced within each condition for time of measurement. These measures of negative attributional style were translated into Chinese using the translation and back translation procedure. A pilot study with 110 college students revealed that these two versions of the ASQ had comparable means and standard deviations, and were highly correlated ( r = .73, p < .001). Internal consistencies for the two measures were satisfactory ( α = .81 and .80). The hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al. 1989 ) has de-emphasized the importance of the internality dimension, and demonstrated that generality, a composite score computed from the stable and global items, may show a stronger relationship to depression than does the traditional internal, stable, and global composite. Past research reported satisfactory internal consistency with the generality score, the alphas of which ranged from .67 to .77 (Fresco et al. 2006 ; Metalsky et al. 1987 ). The generality score was used to index negative attributional style in this study. In the present sample, coefficient alphas for the generality score (ASQ-GEN) were .75 at Time 1 and .81 at Time 2.

Experimental Conditions

The three manipulated conditions were designed to influence the degree of self-focus and processing mode of thinking by requiring the participants to focus their attention on a series of 45 items presented in written form in Chinese for 8 min (adapted from Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow 1993 ). For the two rumination conditions, 45 identical items that were symptom-focused, emotion-focused and self-focused were used but with different sets of instruction for manipulating the modes of processing (adapted from Watkins and Teasdale 2004 ). Instructions for the analytical self-focus condition emphasized thinking about the causes, meanings, and consequences of each item whereas the instructions for the experiential self-focus condition emphasized focusing one’s attention on the experience of each item. The distraction condition required participants to focus their attention externally on thoughts that were not related to self. Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow ( 1993 ) reported that items in both the rumination and the distraction conditions were rated as being equally neutral in affective tone by nondysphoric judges. The translation and back translation procedure was used to develop the Chinese instructions and items for the manipulated conditions.

After the participants had given their written informed consent, they completed the BDI-II and baseline measures of the VAS and the ASQ-GEN. The experimenter then introduced and explained the manipulation task. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the three manipulated conditions (analytical self-focus, experiential self-focus, and distraction), and were told to spend exactly 8 min on the assigned task. Following the manipulation, the participants completed the second set of the VAS and the ASQ-GEN. Finally, the participants filled out a questionnaire asking open-ended questions regarding the purpose of the study. They were then thoroughly debriefed. The entire procedure lasted approximately 45 min.

Preliminary Analyses