Qualitative Data Coding 101

How to code qualitative data, the smart way (with examples).

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD) | Reviewed by:Dr Eunice Rautenbach | December 2020

As we’ve discussed previously , qualitative research makes use of non-numerical data – for example, words, phrases or even images and video. To analyse this kind of data, the first dragon you’ll need to slay is qualitative data coding (or just “coding” if you want to sound cool). But what exactly is coding and how do you do it?

Overview: Qualitative Data Coding

In this post, we’ll explain qualitative data coding in simple terms. Specifically, we’ll dig into:

- What exactly qualitative data coding is

- What different types of coding exist

- How to code qualitative data (the process)

- Moving from coding to qualitative analysis

- Tips and tricks for quality data coding

What is qualitative data coding?

Let’s start by understanding what a code is. At the simplest level, a code is a label that describes the content of a piece of text. For example, in the sentence:

“Pigeons attacked me and stole my sandwich.”

You could use “pigeons” as a code. This code simply describes that the sentence involves pigeons.

So, building onto this, qualitative data coding is the process of creating and assigning codes to categorise data extracts. You’ll then use these codes later down the road to derive themes and patterns for your qualitative analysis (for example, thematic analysis ). Coding and analysis can take place simultaneously, but it’s important to note that coding does not necessarily involve identifying themes (depending on which textbook you’re reading, of course). Instead, it generally refers to the process of labelling and grouping similar types of data to make generating themes and analysing the data more manageable.

Makes sense? Great. But why should you bother with coding at all? Why not just look for themes from the outset? Well, coding is a way of making sure your data is valid . In other words, it helps ensure that your analysis is undertaken systematically and that other researchers can review it (in the world of research, we call this transparency). In other words, good coding is the foundation of high-quality analysis.

What are the different types of coding?

Now that we’ve got a plain-language definition of coding on the table, the next step is to understand what types of coding exist. Let’s start with the two main approaches, deductive and inductive coding.

Deductive coding 101

With deductive coding, we make use of pre-established codes, which are developed before you interact with the present data. This usually involves drawing up a set of codes based on a research question or previous research . You could also use a code set from the codebook of a previous study.

For example, if you were studying the eating habits of college students, you might have a research question along the lines of

“What foods do college students eat the most?”

As a result of this research question, you might develop a code set that includes codes such as “sushi”, “pizza”, and “burgers”.

Deductive coding allows you to approach your analysis with a very tightly focused lens and quickly identify relevant data . Of course, the downside is that you could miss out on some very valuable insights as a result of this tight, predetermined focus.

Inductive coding 101

But what about inductive coding? As we touched on earlier, this type of coding involves jumping right into the data and then developing the codes based on what you find within the data.

For example, if you were to analyse a set of open-ended interviews , you wouldn’t necessarily know which direction the conversation would flow. If a conversation begins with a discussion of cats, it may go on to include other animals too, and so you’d add these codes as you progress with your analysis. Simply put, with inductive coding, you “go with the flow” of the data.

Inductive coding is great when you’re researching something that isn’t yet well understood because the coding derived from the data helps you explore the subject. Therefore, this type of coding is usually used when researchers want to investigate new ideas or concepts , or when they want to create new theories.

A little bit of both… hybrid coding approaches

If you’ve got a set of codes you’ve derived from a research topic, literature review or a previous study (i.e. a deductive approach), but you still don’t have a rich enough set to capture the depth of your qualitative data, you can combine deductive and inductive methods – this is called a hybrid coding approach.

To adopt a hybrid approach, you’ll begin your analysis with a set of a priori codes (deductive) and then add new codes (inductive) as you work your way through the data. Essentially, the hybrid coding approach provides the best of both worlds, which is why it’s pretty common to see this in research.

Need a helping hand?

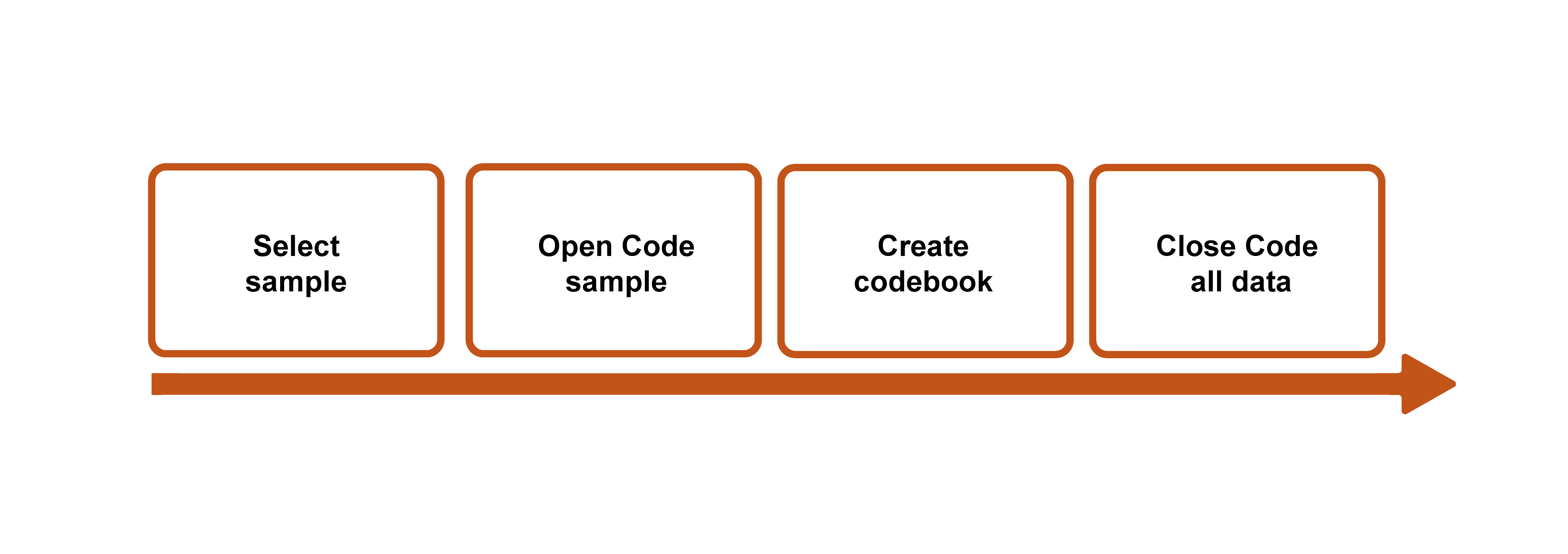

How to code qualitative data

Now that we’ve looked at the main approaches to coding, the next question you’re probably asking is “how do I actually do it?”. Let’s take a look at the coding process , step by step.

Both inductive and deductive methods of coding typically occur in two stages: initial coding and line by line coding .

In the initial coding stage, the objective is to get a general overview of the data by reading through and understanding it. If you’re using an inductive approach, this is also where you’ll develop an initial set of codes. Then, in the second stage (line by line coding), you’ll delve deeper into the data and (re)organise it according to (potentially new) codes.

Step 1 – Initial coding

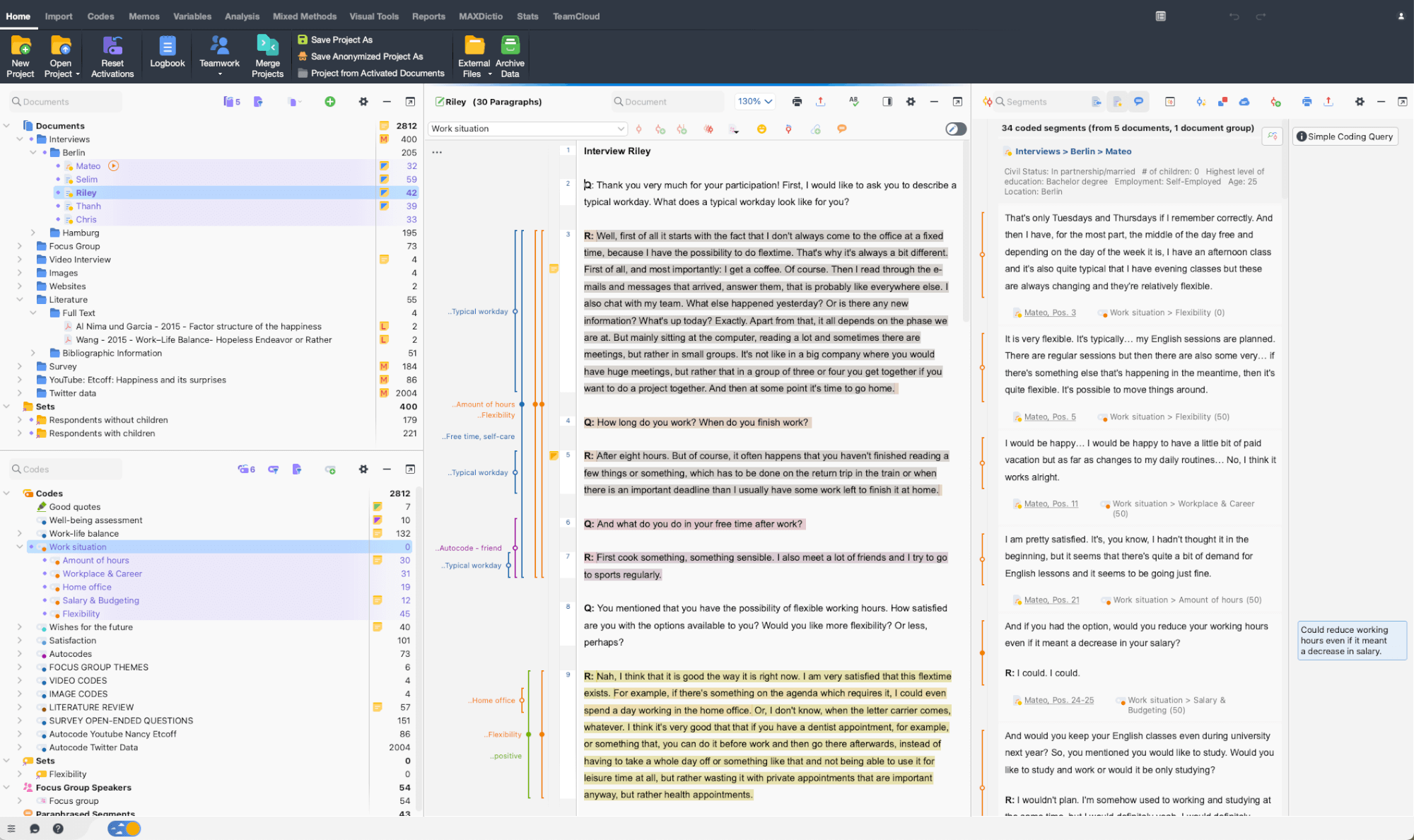

The first step of the coding process is to identify the essence of the text and code it accordingly. While there are various qualitative analysis software packages available, you can just as easily code textual data using Microsoft Word’s “comments” feature.

Let’s take a look at a practical example of coding. Assume you had the following interview data from two interviewees:

What pets do you have?

I have an alpaca and three dogs.

Only one alpaca? They can die of loneliness if they don’t have a friend.

I didn’t know that! I’ll just have to get five more.

I have twenty-three bunnies. I initially only had two, I’m not sure what happened.

In the initial stage of coding, you could assign the code of “pets” or “animals”. These are just initial, fairly broad codes that you can (and will) develop and refine later. In the initial stage, broad, rough codes are fine – they’re just a starting point which you will build onto in the second stage.

How to decide which codes to use

But how exactly do you decide what codes to use when there are many ways to read and interpret any given sentence? Well, there are a few different approaches you can adopt. The main approaches to initial coding include:

- In vivo coding

Process coding

- Open coding

Descriptive coding

Structural coding.

- Value coding

Let’s take a look at each of these:

In vivo coding

When you use in vivo coding, you make use of a participants’ own words , rather than your interpretation of the data. In other words, you use direct quotes from participants as your codes. By doing this, you’ll avoid trying to infer meaning, rather staying as close to the original phrases and words as possible.

In vivo coding is particularly useful when your data are derived from participants who speak different languages or come from different cultures. In these cases, it’s often difficult to accurately infer meaning due to linguistic or cultural differences.

For example, English speakers typically view the future as in front of them and the past as behind them. However, this isn’t the same in all cultures. Speakers of Aymara view the past as in front of them and the future as behind them. Why? Because the future is unknown, so it must be out of sight (or behind us). They know what happened in the past, so their perspective is that it’s positioned in front of them, where they can “see” it.

In a scenario like this one, it’s not possible to derive the reason for viewing the past as in front and the future as behind without knowing the Aymara culture’s perception of time. Therefore, in vivo coding is particularly useful, as it avoids interpretation errors.

Next up, there’s process coding, which makes use of action-based codes . Action-based codes are codes that indicate a movement or procedure. These actions are often indicated by gerunds (words ending in “-ing”) – for example, running, jumping or singing.

Process coding is useful as it allows you to code parts of data that aren’t necessarily spoken, but that are still imperative to understanding the meaning of the texts.

An example here would be if a participant were to say something like, “I have no idea where she is”. A sentence like this can be interpreted in many different ways depending on the context and movements of the participant. The participant could shrug their shoulders, which would indicate that they genuinely don’t know where the girl is; however, they could also wink, showing that they do actually know where the girl is.

Simply put, process coding is useful as it allows you to, in a concise manner, identify the main occurrences in a set of data and provide a dynamic account of events. For example, you may have action codes such as, “describing a panda”, “singing a song about bananas”, or “arguing with a relative”.

Descriptive coding aims to summarise extracts by using a single word or noun that encapsulates the general idea of the data. These words will typically describe the data in a highly condensed manner, which allows the researcher to quickly refer to the content.

Descriptive coding is very useful when dealing with data that appear in forms other than traditional text – i.e. video clips, sound recordings or images. For example, a descriptive code could be “food” when coding a video clip that involves a group of people discussing what they ate throughout the day, or “cooking” when coding an image showing the steps of a recipe.

Structural coding involves labelling and describing specific structural attributes of the data. Generally, it includes coding according to answers to the questions of “ who ”, “ what ”, “ where ”, and “ how ”, rather than the actual topics expressed in the data. This type of coding is useful when you want to access segments of data quickly, and it can help tremendously when you’re dealing with large data sets.

For example, if you were coding a collection of theses or dissertations (which would be quite a large data set), structural coding could be useful as you could code according to different sections within each of these documents – i.e. according to the standard dissertation structure . What-centric labels such as “hypothesis”, “literature review”, and “methodology” would help you to efficiently refer to sections and navigate without having to work through sections of data all over again.

Structural coding is also useful for data from open-ended surveys. This data may initially be difficult to code as they lack the set structure of other forms of data (such as an interview with a strict set of questions to be answered). In this case, it would useful to code sections of data that answer certain questions such as “who?”, “what?”, “where?” and “how?”.

Let’s take a look at a practical example. If we were to send out a survey asking people about their dogs, we may end up with a (highly condensed) response such as the following:

Bella is my best friend. When I’m at home I like to sit on the floor with her and roll her ball across the carpet for her to fetch and bring back to me. I love my dog.

In this set, we could code Bella as “who”, dog as “what”, home and floor as “where”, and roll her ball as “how”.

Values coding

Finally, values coding involves coding that relates to the participant’s worldviews . Typically, this type of coding focuses on excerpts that reflect the values, attitudes, and beliefs of the participants. Values coding is therefore very useful for research exploring cultural values and intrapersonal and experiences and actions.

To recap, the aim of initial coding is to understand and familiarise yourself with your data , to develop an initial code set (if you’re taking an inductive approach) and to take the first shot at coding your data . The coding approaches above allow you to arrange your data so that it’s easier to navigate during the next stage, line by line coding (we’ll get to this soon).

While these approaches can all be used individually, it’s important to remember that it’s possible, and potentially beneficial, to combine them . For example, when conducting initial coding with interviews, you could begin by using structural coding to indicate who speaks when. Then, as a next step, you could apply descriptive coding so that you can navigate to, and between, conversation topics easily.

Step 2 – Line by line coding

Once you’ve got an overall idea of our data, are comfortable navigating it and have applied some initial codes, you can move on to line by line coding. Line by line coding is pretty much exactly what it sounds like – reviewing your data, line by line, digging deeper and assigning additional codes to each line.

With line-by-line coding, the objective is to pay close attention to your data to add detail to your codes. For example, if you have a discussion of beverages and you previously just coded this as “beverages”, you could now go deeper and code more specifically, such as “coffee”, “tea”, and “orange juice”. The aim here is to scratch below the surface. This is the time to get detailed and specific so as to capture as much richness from the data as possible.

In the line-by-line coding process, it’s useful to code everything in your data, even if you don’t think you’re going to use it (you may just end up needing it!). As you go through this process, your coding will become more thorough and detailed, and you’ll have a much better understanding of your data as a result of this, which will be incredibly valuable in the analysis phase.

Moving from coding to analysis

Once you’ve completed your initial coding and line by line coding, the next step is to start your analysis . Of course, the coding process itself will get you in “analysis mode” and you’ll probably already have some insights and ideas as a result of it, so you should always keep notes of your thoughts as you work through the coding.

When it comes to qualitative data analysis, there are many different types of analyses (we discuss some of the most popular ones here ) and the type of analysis you adopt will depend heavily on your research aims, objectives and questions . Therefore, we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole here, but we’ll cover the important first steps that build the bridge from qualitative data coding to qualitative analysis.

When starting to think about your analysis, it’s useful to ask yourself the following questions to get the wheels turning:

- What actions are shown in the data?

- What are the aims of these interactions and excerpts? What are the participants potentially trying to achieve?

- How do participants interpret what is happening, and how do they speak about it? What does their language reveal?

- What are the assumptions made by the participants?

- What are the participants doing? What is going on?

- Why do I want to learn about this? What am I trying to find out?

- Why did I include this particular excerpt? What does it represent and how?

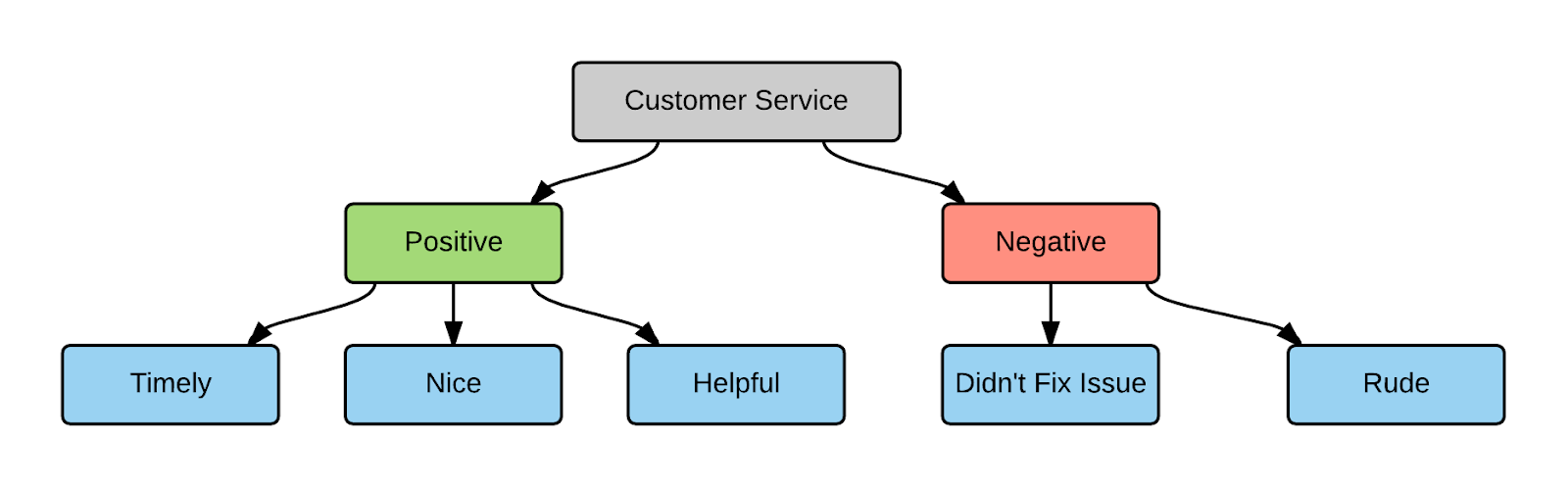

Code categorisation

Categorisation is simply the process of reviewing everything you’ve coded and then creating code categories that can be used to guide your future analysis. In other words, it’s about creating categories for your code set. Let’s take a look at a practical example.

If you were discussing different types of animals, your initial codes may be “dogs”, “llamas”, and “lions”. In the process of categorisation, you could label (categorise) these three animals as “mammals”, whereas you could categorise “flies”, “crickets”, and “beetles” as “insects”. By creating these code categories, you will be making your data more organised, as well as enriching it so that you can see new connections between different groups of codes.

Theme identification

From the coding and categorisation processes, you’ll naturally start noticing themes. Therefore, the logical next step is to identify and clearly articulate the themes in your data set. When you determine themes, you’ll take what you’ve learned from the coding and categorisation and group it all together to develop themes. This is the part of the coding process where you’ll try to draw meaning from your data, and start to produce a narrative . The nature of this narrative depends on your research aims and objectives, as well as your research questions (sounds familiar?) and the qualitative data analysis method you’ve chosen, so keep these factors front of mind as you scan for themes.

Tips & tricks for quality coding

Before we wrap up, let’s quickly look at some general advice, tips and suggestions to ensure your qualitative data coding is top-notch.

- Before you begin coding, plan out the steps you will take and the coding approach and technique(s) you will follow to avoid inconsistencies.

- When adopting deductive coding, it’s useful to use a codebook from the start of the coding process. This will keep your work organised and will ensure that you don’t forget any of your codes.

- Whether you’re adopting an inductive or deductive approach, keep track of the meanings of your codes and remember to revisit these as you go along.

- Avoid using synonyms for codes that are similar, if not the same. This will allow you to have a more uniform and accurate coded dataset and will also help you to not get overwhelmed by your data.

- While coding, make sure that you remind yourself of your aims and coding method. This will help you to avoid directional drift , which happens when coding is not kept consistent.

- If you are working in a team, make sure that everyone has been trained and understands how codes need to be assigned.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

28 Comments

I appreciated the valuable information provided to accomplish the various stages of the inductive and inductive coding process. However, I would have been extremely satisfied to be appraised of the SPECIFIC STEPS to follow for: 1. Deductive coding related to the phenomenon and its features to generate the codes, categories, and themes. 2. Inductive coding related to using (a) Initial (b) Axial, and (c) Thematic procedures using transcribe data from the research questions

Thank you so much for this. Very clear and simplified discussion about qualitative data coding.

This is what I want and the way I wanted it. Thank you very much.

All of the information’s are valuable and helpful. Thank for you giving helpful information’s. Can do some article about alternative methods for continue researches during the pandemics. It is more beneficial for those struggling to continue their researchers.

Thank you for your information on coding qualitative data, this is a very important point to be known, really thank you very much.

Very useful article. Clear, articulate and easy to understand. Thanks

This is very useful. You have simplified it the way I wanted it to be! Thanks

Thank you so very much for explaining, this is quite helpful!

hello, great article! well written and easy to understand. Can you provide some of the sources in this article used for further reading purposes?

You guys are doing a great job out there . I will not realize how many students you help through your articles and post on a daily basis. I have benefited a lot from your work. this is remarkable.

Wonderful one thank you so much.

Hello, I am doing qualitative research, please assist with example of coding format.

This is an invaluable website! Thank you so very much!

Well explained and easy to follow the presentation. A big thumbs up to you. Greatly appreciate the effort 👏👏👏👏

Thank you for this clear article with examples

Thank you for the detailed explanation. I appreciate your great effort. Congrats!

Ahhhhhhhhhh! You just killed me with your explanation. Crystal clear. Two Cheers!

D0 you have primary references that was used when creating this? If so, can you share them?

Being a complete novice to the field of qualitative data analysis, your indepth analysis of the process of thematic analysis has given me better insight. Thank you so much.

Excellent summary

Thank you so much for your precise and very helpful information about coding in qualitative data.

Thanks a lot to this helpful information. You cleared the fog in my brain.

Glad to hear that!

This has been very helpful. I am excited and grateful.

I still don’t understand the coding and categorizing of qualitative research, please give an example on my research base on the state of government education infrastructure environment in PNG

Wahho, this is amazing and very educational to have come across this site.. from a little search to a wide discovery of knowledge.

Thanks I really appreciate this.

Thank you so much! Very grateful.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Higher Ed Professor

Demystifying higher education.

- Productivity

- Issue Discussion

- Current Events

Coding in qualitative research

C oding is a central part of qualitative data analysis, yet I often find that doctoral students particularly struggle with knowing how to code their qualitative data. In today’s post, I want to share some foundational information for coding to provide a sense of the role of coding as a central function of qualitative data analysis.

In qualitative research, a researcher begins to understand and make sense of the data through coding. Thus, coding plays a critical role in the data analysis process (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, 2014).

A code is an identified or highlighted section of text, frequently a word or short quotation, that helps illustrate the topic of the study. Saldana (2015) defines a code as “most often a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” (p. 3).

Coding breaks down the data to the smallest unit, or idea, that can stand alone. Coding data “leads you from the data to the idea, and from the idea to all the data pertaining to that idea” (Richards & Morse, 2007, p. 137). Coding effectively indexes the data, and serves as a tool to help researchers build connections between different pieces of data.

Coding breaks down data into easy-to-digest pieces (the codes themselves), which can then be organized and reorganized into patterns and ideas that answer the research questions (Bernard, Wutich, & Ryan, 2016; Grbich, 2007).

Codes may be used only one time, or perhaps they are used numerous times through the course of data analysis; other times, you may assign one or more codes to a statement from an interview, for example, to identify the significance of the passage of data (Miles et al., 2014).

Continuous refining and adjusting of the coding scheme is inherent to coding and data analysis. This refinement occurs through the expansion of ideas, the analysis of additional data, and the search for themes and patterns. While coding may seem like a precursor to actual data analysis, in reality coding represents a crucial step in the analytic process.

As a novice qualitative researcher, students might wonder what data should be coded and how the data should be identified. Richards and Morse (2007) joke, “If it moves, code it” (p. 146).

First, you should code all of the data including all transcripts, documents, observations, notes, memos, visual evidence, and anything else gathered during data collection. Second, you should code what participants are doing or did in the past, including activities, strategies, and assumptions (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 1995).

Ideas that directly relate to the literature, framework, and research questions should be coded, in addition to any ideas that seem potentially important or related to the overall goals of the study.

Also, coding ideas that were expected at the beginning of the dissertation as well as those that were unexpected can prove useful (Creswell, 2007). The number of codes that students should have after multiple rounds of data analysis varies, but basic guidelines can help determine an approximate figure.

For example, Lichtman (2006) suggests that education related qualitative research studies should have between 80 and 100 codes that then get distilled into five to seven major categories or themes.

Undoubtedly, while some students end up with more or fewer codes and major themes, aiming for 80-100 emerging themes is a useful target at the start of data analysis.

Saldana (2015), in defining approaches to qualitative coding, identifies two types: “lumping” and “splitting.”

“Lumpers” begin analysis with a single, overarching code for an entire paragraph or passage of text, essentially “lumping” the data together to fit more data into fewer, broader codes.

In contrast, “splitters” initially break a given passage into component parts using six or eight more specific codes rather than one, “splitting” the passage up.

We often find that doctoral students commonly fall into one of these two approaches, but we suggest that using a bit of both approaches is likely a productive avenue.

After a document or two has been coded, take a step back and think about how you are engaging in the process of coding. Determine if you have adopted the lumper or the splitter approach, and then work purposefully to incorporate the other approach in subsequent coding efforts.

By bridging the divide between lumping and splitting, you will have a more comprehensive set of codes that will better enable the next round of data analysis.

The most common types of codes are identified by their ancient Greek descriptors: etic and emic .

Etic codes come from the perspective of the researcher and the framework, literature, and research questions of the study.

In contrast, emic coding focuses on the participant’s perspective and are not always bound to the aims or goals of the study.

Obviously, coding of both types provides valuable insights.

Either approach can be a good place to start with data analysis; we recommend novice qualitative researchers and doctoral students begin with etic coding before moving on to emic.

The fact that etic codes are derived from the research study provides more structure for initial coding than the comparatively unstructured and open-ended emic approach.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

28 Coding and Analysis Strategies

Johnny Saldaña, School of Theatre and Film, Arizona State University

- Published: 04 August 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter provides an overview of selected qualitative data analytic strategies with a particular focus on codes and coding. Preparatory strategies for a qualitative research study and data management are first outlined. Six coding methods are then profiled using comparable interview data: process coding, in vivo coding, descriptive coding, values coding, dramaturgical coding, and versus coding. Strategies for constructing themes and assertions from the data follow. Analytic memo writing is woven throughout the preceding as a method for generating additional analytic insight. Next, display and arts-based strategies are provided, followed by recommended qualitative data analytic software programs and a discussion on verifying the researcher’s analytic findings.

Coding and Analysis Strategies

Anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1983) charmingly mused, “Life is just a bowl of strategies” (p. 25). Strategy , as I use it here, refers to a carefully considered plan or method to achieve a particular goal. The goal in this case is to develop a write-up of your analytic work with the qualitative data you have been given and collected as part of a study. The plans and methods you might employ to achieve that goal are what this article profiles.

Some may perceive strategy as an inappropriate if not colonizing word, suggesting formulaic or regimented approaches to inquiry. I assure you that that is not my intent. My use of strategy is actually dramaturgical in nature: strategies are actions that characters in plays take to overcome obstacles to achieve their objectives. Actors portraying these characters rely on action verbs to generate belief within themselves and to motivate them as they interpret the lines and move appropriately on stage. So what I offer is a qualitative researcher’s array of actions from which to draw to overcome the obstacles to thinking to achieve an analysis of your data. But unlike the pre-scripted text of a play in which the obstacles, strategies, and outcomes have been predetermined by the playwright, your work must be improvisational—acting, reacting, and interacting with data on a moment-by-moment basis to determine what obstacles stand in your way, and thus what strategies you should take to reach your goals.

Another intriguing quote to keep in mind comes from research methodologist Robert E. Stake (1995) who posits, “Good research is not about good methods as much as it is about good thinking” (p. 19). In other words, strategies can take you only so far. You can have a box full of tools, but if you do not know how to use them well or use them creatively, the collection seems rather purposeless. One of the best ways we learn is by doing . So pick up one or more of these strategies (in the form of verbs) and take analytic action with your data. Also keep in mind that these are discussed in the order in which they may typically occur, although humans think cyclically, iteratively, and reverberatively, and each particular research project has its own unique contexts and needs. So be prepared for your mind to jump purposefully and/or idiosyncratically from one strategy to another throughout the study.

QDA (Qualitative Data Analysis) Strategy: To Foresee

To foresee in QDA is to reflect beforehand on what forms of data you will most likely need and collect, which thus informs what types of data analytic strategies you anticipate using.

Analysis, in a way, begins even before you collect data. As you design your research study in your mind and on a word processor page, one strategy is to consider what types of data you may need to help inform and answer your central and related research questions. Interview transcripts, participant observation field notes, documents, artifacts, photographs, video recordings, and so on are not only forms of data but foundations for how you may plan to analyze them. A participant interview, for example, suggests that you will transcribe all or relevant portions of the recording, and use both the transcription and the recording itself as sources for data analysis. Any analytic memos (discussed later) or journal entries you make about your impressions of the interview also become data to analyze. Even the computing software you plan to employ will be relevant to data analysis as it may help or hinder your efforts.

As your research design formulates, compose one to two paragraphs that outline how your QDA may proceed. This will necessitate that you have some background knowledge of the vast array of methods available to you. Thus surveying the literature is vital preparatory work.

QDA Strategy: To Survey

To survey in QDA is to look for and consider the applicability of the QDA literature in your field that may provide useful guidance for your forthcoming data analytic work.

General sources in QDA will provide a good starting point for acquainting you with the data analytic strategies available for the variety of genres in qualitative inquiry (e.g., ethnography, phenomenology, case study, arts-based research, mixed methods). One of the most accessible is Graham R. Gibbs’ (2007) Analysing Qualitative Data , and one of the most richly detailed is Frederick J. Wertz et al.'s (2011) Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis . The author’s core texts for this article came from The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers ( Saldaña, 2009 , 2013 ) and Fundamentals of Qualitative Research ( Saldaña, 2011 ).

If your study’s methodology or approach is grounded theory, for example, then a survey of methods works by such authors as Barney G. Glaser, Anselm L. Strauss, Juliet Corbin and, in particular, the prolific Kathy Charmaz (2006) may be expected. But there has been a recent outpouring of additional book publications in grounded theory by Birks & Mills (2011) , Bryant & Charmaz (2007) , Stern & Porr (2011) , plus the legacy of thousands of articles and chapters across many disciplines that have addressed grounded theory in their studies.

Particular fields such as education, psychology, social work, health care, and others also have their own QDA methods literature in the form of texts and journals, plus international conferences and workshops for members of the profession. Most important is to have had some university coursework and/or mentorship in qualitative research to suitably prepare you for the intricacies of QDA. Also acknowledge that the emergent nature of qualitative inquiry may require you to adopt different analytic strategies from what you originally planned.

QDA Strategy: To Collect

To collect in QDA is to receive the data given to you by participants and those data you actively gather to inform your study.

QDA is concurrent with data collection and management. As interviews are transcribed, field notes are fleshed out, and documents are filed, the researcher uses the opportunity to carefully read the corpus and make preliminary notations directly on the data documents by highlighting, bolding, italicizing, or noting in some way any particularly interesting or salient portions. As these data are initially reviewed, the researcher also composes supplemental analytic memos that include first impressions, reminders for follow-up, preliminary connections, and other thinking matters about the phenomena at work.

Some of the most common fieldwork tools you might use to collect data are notepads, pens and pencils, file folders for documents, a laptop or desktop with word processing software (Microsoft Word and Excel are most useful) and internet access, a digital camera, and a voice recorder. Some fieldworkers may even employ a digital video camera to record social action, as long as participant permissions have been secured. But everything originates from the researcher himself or herself. Your senses are immersed in the cultural milieu you study, taking in and holding on to relevant details or “significant trivia,” as I call them. You become a human camera, zooming out to capture the broad landscape of your field site one day, then zooming in on a particularly interesting individual or phenomenon the next. Your analysis is only as good as the data you collect.

Fieldwork can be an overwhelming experience because so many details of social life are happening in front of you. Take a holistic approach to your entree, but as you become more familiar with the setting and participants, actively focus on things that relate to your research topic and questions. Of course, keep yourself open to the intriguing, surprising, and disturbing ( Sunstein & Chiseri-Strater, 2012 , p. 115), for these facets enrich your study by making you aware of the unexpected.

QDA Strategy: To Feel

To feel in QDA is to gain deep emotional insight into the social worlds you study and what it means to be human.

Virtually everything we do has an accompanying emotion(s), and feelings are both reactions and stimuli for action. Others’ emotions clue you to their motives, attitudes, values, beliefs, worldviews, identities, and other subjective perceptions and interpretations. Acknowledge that emotional detachment is not possible in field research. Attunement to the emotional experiences of your participants plus sympathetic and empathetic responses to the actions around you are necessary in qualitative endeavors. Your own emotional responses during fieldwork are also data because they document the tacit and visceral. It is important during such analytic reflection to assess why your emotional reactions were as they were. But it is equally important not to let emotions alone steer the course of your study. A proper balance must be found between feelings and facts.

QDA Strategy: To Organize

To organize in QDA is to maintain an orderly repository of data for easy access and analysis.

Even in the smallest of qualitative studies, a large amount of data will be collected across time. Prepare both a hard drive and hard copy folders for digital data and paperwork, and back up all materials for security from loss. I recommend that each data “chunk” (e.g., one interview transcript, one document, one day’s worth of field notes) get its own file, with subfolders specifying the data forms and research study logistics (e.g., interviews, field notes, documents, Institutional Review Board correspondence, calendar).

For small-scale qualitative studies, I have found it quite useful to maintain one large master file with all participant and field site data copied and combined with the literature review and accompanying researcher analytic memos. This master file is used to cut and paste related passages together, deleting what seems unnecessary as the study proceeds, and eventually transforming the document into the final report itself. Cosmetic devices such as font style, font size, rich text (italicizing, bolding, underlining, etc.), and color can help you distinguish between different data forms and highlight significant passages. For example, descriptive, narrative passages of field notes are logged in regular font. “Quotations, things spoken by participants, are logged in bold font.” Observer’s comments, such as the researcher’s subjective impressions or analytic jottings, are set in italics.

QDA Strategy: To Jot

To jot in QDA is to write occasional, brief notes about your thinking or reminders for follow up.

A jot is a phrase or brief sentence that will literally fit on a standard size “sticky note.” As data are brought and documented together, take some initial time to review their contents and to jot some notes about preliminary patterns, participant quotes that seem quite vivid, anomalies in the data, and so forth.

As you work on a project, keep something to write with or to voice record with you at all times to capture your fleeting thoughts. You will most likely find yourself thinking about your research when you're not working exclusively on the project, and a “mental jot” may occur to you as you ruminate on logistical or analytic matters. Get the thought documented in some way for later retrieval and elaboration as an analytic memo.

QDA Strategy: To Prioritize

To prioritize in QDA is to determine which data are most significant in your corpus and which tasks are most necessary.

During fieldwork, massive amounts of data in various forms may be collected, and your mind can get easily overwhelmed from the magnitude of the quantity, its richness, and its management. Decisions will need to be made about the most pertinent of them because they help answer your research questions or emerge as salient pieces of evidence. As a sweeping generalization, approximately one half to two thirds of what you collect may become unnecessary as you proceed toward the more formal stages of QDA.

To prioritize in QDA is to also determine what matters most in your assembly of codes, categories, themes, assertions, and concepts. Return back to your research purpose and questions to keep you framed for what the focus should be.

QDA Strategy: To Analyze

To analyze in QDA is to observe and discern patterns within data and to construct meanings that seem to capture their essences and essentials.

Just as there are a variety of genres, elements, and styles of qualitative research, so too are there a variety of methods available for QDA. Analytic choices are most often based on what methods will harmonize with your genre selection and conceptual framework, what will generate the most sufficient answers to your research questions, and what will best represent and present the project’s findings.

Analysis can range from the factual to the conceptual to the interpretive. Analysis can also range from a straightforward descriptive account to an emergently constructed grounded theory to an evocatively composed short story. A qualitative research project’s outcomes may range from rigorously achieved, insightful answers to open-ended, evocative questions; from rich descriptive detail to a bullet-pointed list of themes; and from third-person, objective reportage to first-person, emotion-laden poetry. Just as there are multiple destinations in qualitative research, there are multiple pathways and journeys along the way.

Analysis is accelerated as you take cognitive ownership of your data. By reading and rereading the corpus, you gain intimate familiarity with its contents and begin to notice significant details as well as make new insights about their meanings. Patterns, categories, and their interrelationships become more evident the more you know the subtleties of the database.

Since qualitative research’s design, fieldwork, and data collection are most often provisional, emergent, and evolutionary processes, you reflect on and analyze the data as you gather them and proceed through the project. If preplanned methods are not working, you change them to secure the data you need. There is generally a post-fieldwork period when continued reflection and more systematic data analysis occur, concurrent with or followed by additional data collection, if needed, and the more formal write-up of the study, which is in itself an analytic act. Through field note writing, interview transcribing, analytic memo writing, and other documentation processes, you gain cognitive ownership of your data; and the intuitive, tacit, synthesizing capabilities of your brain begin sensing patterns, making connections, and seeing the bigger picture. The purpose and outcome of data analysis is to reveal to others through fresh insights what we have observed and discovered about the human condition. And fortunately, there are heuristics for reorganizing and reflecting on your qualitative data to help you achieve that goal.

QDA Strategy: To Pattern

To pattern in QDA is to detect similarities within and regularities among the data you have collected.

The natural world is filled with patterns because we, as humans, have constructed them as such. Stars in the night sky are not just a random assembly; our ancestors pieced them together to form constellations like the Big Dipper. A collection of flowers growing wild in a field has a pattern, as does an individual flower’s patterns of leaves and petals. Look at the physical objects humans have created and notice how pattern oriented we are in our construction, organization, and decoration. Look around you in your environment and notice how many patterns are evident on your clothing, in a room, and on most objects themselves. Even our sometimes mundane daily and long-term human actions are reproduced patterns in the form of roles, relationships, rules, routines, and rituals.

This human propensity for pattern making follows us into QDA. From the vast array of interview transcripts, field notes, documents, and other forms of data, there is this instinctive, hardwired need to bring order to the collection—not just to reorganize it but to look for and construct patterns out of it. The discernment of patterns is one of the first steps in the data analytic process, and the methods described next are recommended ways to construct them.

QDA Strategy: To Code

To code in QDA is to assign a truncated, symbolic meaning to each datum for purposes of qualitative analysis.

Coding is a heuristic—a method of discovery—to the meanings of individual sections of data. These codes function as a way of patterning, classifying, and later reorganizing them into emergent categories for further analysis. Different types of codes exist for different types of research genres and qualitative data analytic approaches, but this article will focus on only a few selected methods. First, a definition of a code:

A code in qualitative data analysis is most often a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data. The data can consist of interview transcripts, participant observation fieldnotes, journals, documents, literature, artifacts, photographs, video, websites, e-mail correspondence, and so on. The portion of data to be coded can... range in magnitude from a single word to a full sentence to an entire page of text to a stream of moving images.... Just as a title represents and captures a book or film or poem’s primary content and essence, so does a code represent and capture a datum’s primary content and essence. [ Saldaña, 2009 , p. 3]

One helpful pre-coding task is to divide long selections of field note or interview transcript data into shorter stanzas . Stanza division “chunks” the corpus into more manageable paragraph-like units for coding assignments and analysis. The transcript sample that follows illustrates one possible way of inserting line breaks in-between self-standing passages of interview text for easier readability.

Process Coding

As a first coding example, the following interview excerpt about an employed, single, lower-middle-class adult male’s spending habits during the difficult economic times in the U.S. during 2008–2012 is coded in the right-hand margin in capital letters. The superscript numbers match the datum unit with its corresponding code. This particular method is called process coding, which uses gerunds (“-ing” words) exclusively to represent action suggested by the data. Processes can consist of observable human actions (e.g., BUYING BARGAINS), mental processes (e.g., THINKING TWICE), and more conceptual ideas (e.g., APPRECIATING WHAT YOU’VE GOT). Notice that the interviewer’s (I) portions are not coded, just the participant’s (P). A code is applied each time the subtopic of the interview shifts—even within a stanza—and the same codes can (and should) be used more than once if the subtopics are similar. The central research question driving this qualitative study is, “In what ways are middle-class Americans influenced and affected by the current [2008–2012] economic recession?”

Different researchers analyzing this same piece of data may develop completely different codes, depending on their lenses and filters. The previous codes are only one person’s interpretation of what is happening in the data, not the definitive list. The process codes have transformed the raw data units into new representations for analysis. A listing of them applied to this interview transcript, in the order they appear, reads:

BUYING BARGAINS

QUESTIONING A PURCHASE

THINKING TWICE

STOCKING UP

REFUSING SACRIFICE

PRIORITIZING

FINDING ALTERNATIVES

LIVING CHEAPLY

NOTICING CHANGES

STAYING INFORMED

MAINTAINING HEALTH

PICKING UP THE TAB

APPRECIATING WHAT YOU’VE GOT

Coding the data is the first step in this particular approach to QDA, and categorization is just one of the next possible steps.

QDA Strategy: To Categorize

To categorize in QDA is to cluster similar or comparable codes into groups for pattern construction and further analysis.

Humans categorize things in innumerable ways. Think of an average apartment or house’s layout. The rooms of a dwelling have been constructed or categorized by their builders and occupants according to function. A kitchen is designated as an area to store and prepare food and the cooking and dining materials such as pots, pans, and utensils. A bedroom is designated for sleeping, a closet for clothing storage, a bathroom for bodily functions and hygiene, and so on. Each room is like a category in which related and relevant patterns of human action occur. Of course, there are exceptions now and then, such as eating breakfast in bed rather than in a dining area or living in a small studio apartment in which most possessions are contained within one large room (but nonetheless are most often organized and clustered into subcategories according to function and optimal use of space).

The point here is that the patterns of social action we designate into particular categories during QDA are not perfectly bounded. Category construction is our best attempt to cluster the most seemingly alike things into the most seemingly appropriate groups. Categorizing is reorganizing and reordering the vast array of data from a study because it is from these smaller, larger, and meaning-rich units that we can better grasp the particular features of each one and the categories’ possible interrelationships with one another.

One analytic strategy with a list of codes is to classify them into similar clusters. Obviously, the same codes share the same category, but it is also possible that a single code can merit its own group if you feel it is unique enough. After the codes have been classified, a category label is applied to each grouping. Sometimes a code can also double as a category name if you feel it best summarizes the totality of the cluster. Like coding, categorizing is an interpretive act, for there can be different ways of separating and collecting codes that seem to belong together. The cut-and-paste functions of a word processor are most useful for exploring which codes share something in common.

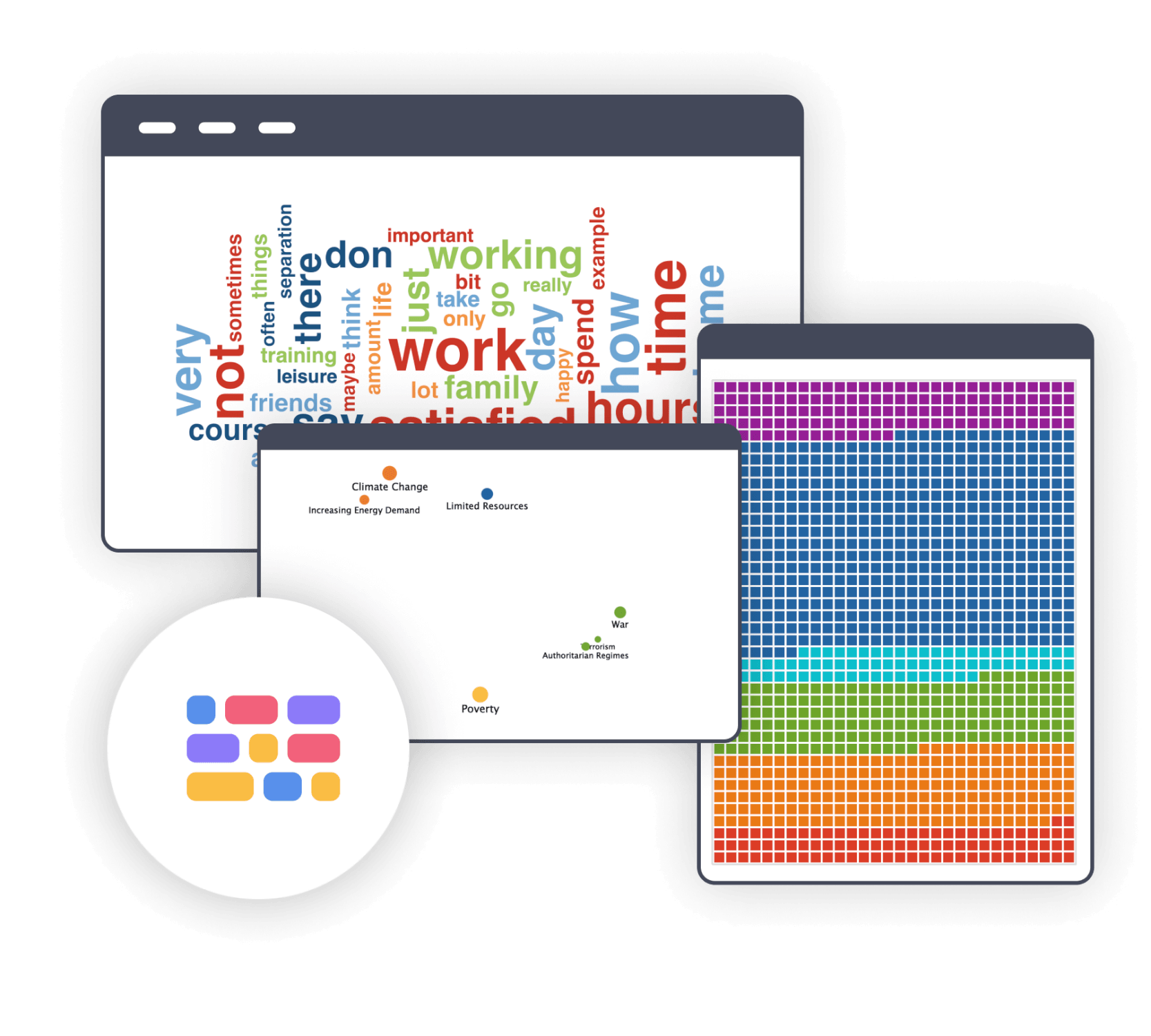

Below is my categorization of the fifteen codes generated from the interview transcript presented earlier. Like the gerunds for process codes, the categories have also been labeled as “-ing” words to connote action. And there was no particular reason why fifteen codes resulted in three categories—there could have been less or even more, but this is how the array came together after my reflections on which codes seemed to belong together. The category labels are ways of answering “why” they belong together. For at-a-glance differentiation, I place codes in CAPITAL LETTERS and categories in upper and lower case Bold Font :

Category 1: Thinking Strategically

Category 2: Spending Strategically

Category 3: Living Strategically

APPRECIATING WHAT YOU'VE GOT

Notice that the three category labels share a common word: “strategically.” Where did this word come from? It came from analytic reflection on the original data, the codes, and the process of categorizing the codes and generating their category labels. It was the analyst’s choice based on the interpretation of what primary action was happening. Your categories generated from your coded data do not need to share a common word or phrase, but I find that this technique, when appropriate, helps build a sense of unity to the initial analytic scheme.

The three categories— Thinking Strategically , Spending Strategically , and Living Strategically —are then reflected upon for how they might interact and interplay. This is where the next major facet of data analysis, analytic memos, enters the scheme. But a necessary section on the basic principles of interrelationship and analytic reasoning must precede that discussion.

QDA Strategy: To Interrelate

To interrelate in QDA is to propose connections within, between, and among the constituent elements of analyzed data.

One task of QDA is to explore the ways our patterns and categories interact and interplay. I use these terms to suggest the qualitative equivalent of statistical correlation, but interaction and interplay are much more than a simple relationship. They imply interrelationship . Interaction refers to reverberative connections—for example, how one or more categories might influence and affect the others, how categories operate concurrently, or whether there is some kind of “domino” effect to them. Interplay refers to the structural and processual nature of categories—for example, whether some type of sequential order, hierarchy, or taxonomy exists; whether any overlaps occur; whether there is superordinate and subordinate arrangement; and what types of organizational frameworks or networks might exist among them. The positivist construct of “cause and effect” becomes influences and affects in QDA.

There can even be patterns of patterns and categories of categories if your mind thinks conceptually and abstractly enough. Our minds can intricately connect multiple phenomena but only if the data and their analyses support the constructions. We can speculate about interaction and interplay all we want, but it is only through a more systematic investigation of the data—in other words, good thinking—that we can plausibly establish any possible interrelationships.

QDA Strategy: To Reason

To reason in QDA is to think in ways that lead to causal probabilities, summative findings, and evaluative conclusions.

Unlike quantitative research, with its statistical formulas and established hypothesis-testing protocols, qualitative research has no standardized methods of data analysis. Rest assured, there are recommended guidelines from the field’s scholars and a legacy of analytic strategies from which to draw. But the primary heuristics (or methods of discovery) you apply during a study are deductive , inductive , abductive , and retroductive reasoning. Deduction is what we generally draw and conclude from established facts and evidence. Induction is what we experientially explore and infer to be transferable from the particular to the general, based on an examination of the evidence and an accumulation of knowledge. Abduction is surmising from the evidence that which is most likely, those explanatory hunches based on clues. “Whereas deductive inferences are certain (so long as their premises are true) and inductive inferences are probable, abductive inferences are merely plausible” ( Shank, 2008 , p. 1). Retroduction is historic reconstruction, working backwards to figure out how the current conditions came to exist.