Freedom and Happiness in Nations: A Research Synthesis

- Published: 14 June 2017

- Volume 13 , pages 435–456, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Amanina Abdur Rahman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2495-5269 1 &

- Ruut Veenhoven 2 , 3

2126 Accesses

22 Citations

15 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

An Erratum to this article was published on 29 August 2017

This article has been updated

Freedom is highly valued, but there are limits to the amount of freedom a society can allow its members. This begs the question of how much freedom is too much. The answers to that question differ across political cultures and are typically based on ideological argumentation. In this paper, we consider the compatibility of freedom and happiness in nations by taking stock of the research findings on that matter, gathered in the World Database of Happiness. We find that freedom and happiness are positively correlated in contemporary nations. The pattern of correlation differs somewhat across cultures and aspects of freedom. We found no pattern of declining happiness returns, which suggests that freedom has not passed its maximum in the freest countries.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Freedom and happiness in nations: why the Finns are happier than the French

Gaël Brulé & Ruut Veenhoven

Measuring Economic Freedom: Better Without Size of Government

Cultural Evolution Shifts the Source of Happiness from Religion to Subjective Freedom

Michael Minkov, Christian Welzel & Michael Schachner

Change history

29 august 2017.

An erratum to this article has been published.

The six determinants are GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, generosity, freedom from corruption, and freedom to make life choices. Together, these six variables explain 74% of the variation (adjusted R-squared) in the national annual average ladder scores of countries (Helliwell et al. 2017 ).

A full description of the construction of the index is available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2016/methodology

This proposition, as well as the one in the previous paragraph are not new, and are built on past theories and literature that are not within the scope of our study. The publications by Inglehart, Welzel, and Klingemann are the most relevant to our study as they also provide empirical evidence of the human development syndrome. A detailed theoretical background is available in Welzel et al. ( 2003 ) and Welzel ( 2013 ).

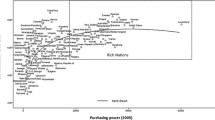

The happiness measure used is the average response to the Cantril ladder question, which asks respondents to rate their quality of life on a scale of 0 to 10, with higher values meaning higher levels of happiness. It is the average response for the years 2013–2015, obtained from the World Happiness Report 2016 (Helliwell et al. 2016 ). The measure of economic freedom is on a scale from 1 to 10, where higher values indicate higher levels of economic freedom, obtained from the Economic Freedom of the World Report 2015 (Gwartney et al. 2015 ). The measure of perceived freedom is on a scale of 1 to 10, with higher values meaning higher levels of perceived freedom. It is obtained from the sixth wave of the World Values Survey, conducted in the years 2012–2014, and is described in detail in Section 2.3 above.

The link to the WDH finding page for the relationship between economic freedom and happiness in Gehring ( 2013 ) is: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_cor/desc_cor.php?sssid=24018

This distinction is stated in the page that lists the research findings on the World Database of Happiness, accessible from the table by Control + Click on the symbols representing each association.

Findings in the World Database of Happiness: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_cor/desc_cor.php?sssid=24018

Bjørnskov, C. (2014). Do economic reforms alleviate subjective well-being losses of economic crises? Journal of Happiness Studies, 15 (1), 163–182. doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9442-y .

Article Google Scholar

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2007). The bigger the better? Evidence of the effect of government size on life satisfaction around the world. Public Choice, 130 (3–4), 267–292. doi: 10.1007/s11127-006-9081-5 .

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2010). Formal institutions and subjective well-being: revisiting the cross-country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 26 (4), 419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.03.001 .

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143 (1–2), 67–101. doi: 10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2 .

Google Scholar

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: integration in personality. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation 1990 (Vol. 38, pp. 237–288). Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1976). Pictures of facial affect . California: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Elliott, M., & Hayward, R. D. (2009). Religion and life satisfaction worldwide: the role of government regulation*. Sociology of Religion, 70 (3), 285–310. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srp028 .

Freedom House (2016). Freedom in the World 2016 . Retrieved from www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2016 .

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Investigating the patterns and determinants of life satisfaction in Germany following reunification. The Journal of Human Resources, 39 (3), 649–674. doi: 10.2307/3558991 .

Fromm, E. (1994). Escape from Freedom (Reprint). New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Gehring, K. (2013). Who benefits from economic freedom? Unraveling the effect of economic freedom on subjective well-being. World Development, 50 , 74–90. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.05.003 .

Gerring, J., Bond, P., Barndt, W. T., & Moreno, C. (2005). Democracy and economic growth: a historical perspective. World Politics, 57 (3), 323–364.

Gwartney, J. D., Lawson, R., & Hall, J. (2015). Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report . Fraser Institute. Retrieved from www.fraserinstitute.org .

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2016). World Happiness Report 2016, Update (Vol. I). New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2017). World Happiness Report 2017 . New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Henisz, W. J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics and Politics, 12 (1), 1–31. doi: 10.1111/1468-0343.00066 .

Henisz, W. J. (2002). The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11 (2), 355–389. doi: 10.1093/icc/11.2.355 .

Heston, A., Summers, R., & Aten, B. (2002). Penn World Table Version 6.1. Center for International Comparisons at the University of Pennsylvania (CICUP).

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values . Beverly Hills: SAGE.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Humana, C. (1992). World human rights guide . New York: Oxford University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: the human development sequence . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Jackman, R. W., & Miller, R. A. (1998). Social capital and Politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 1 (1), 47–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.47 .

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1682130). Rochester: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1682130 .

Miller, T., & Kim, A. (2016). 2016 Index of Economic Freedom . The Heritage Foundation and Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

Muller, E. N., & Seligson, M. A. (1994). Civic culture and democracy: the question of causal relationships. The American Political Science Review, 88 (3), 635–652. doi: 10.2307/2944800 .

Rode, M. (2012). Do good institutions make citizens happy, or do happy citizens build better institutions? Journal of Happiness Studies, 14 (5), 1479–1505. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9391-x .

Rotter, J. B. (1990). Internal versus external control of reinforcement: a case history of a variable. American Psychologist, 45 (4), 489–493. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.489 .

Rustow, D. A. (1970). Transitions to democracy: toward a dynamic model. Comparative Politics, 2 (3), 337–363. doi: 10.2307/421307 .

Schwartz, B. (2009). The paradox of choice . New York: Harper Collins.

Smart, J. J. C., & Williams, B. (1973). Utilitarianism: for and against . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tsai, M.-C. (2009). Market openness, transition economies and subjective Wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10 (5), 523–539. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9107-4 .

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24 (1), 1–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00292648 .

Veenhoven, R. (1999). Quality-of-life in individualistic society. Social Indicators Research, 48 (2), 159–188. doi: 10.1023/A:1006923418502 .

Veenhoven, R. (2000). Freedom and happiness: a comparative study in forty-four nations in the early 1990s. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 257–288). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2009). How do we assess how happy we are? Tenets, implications and tenability of three theories. In A. K. Dutt & B. Radcliff (Eds.), Happiness, Economics and Politics: towards a multi-disciplinary approach (pp. 45–69). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Veenhoven, R. (2010). How universal is happiness? In E. Diener, D. Kahneman, & J. Helliwell (Eds.), International differences in well-being (pp. 328–350). New York: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Veenhoven, R. (2012). Cross-national differences in happiness: cultural measurement bias or effect of culture? International Journal of Wellbeing, 2 (4). doi: 10.5502/ijw.v2.i4.4 .

Veenhoven, R. (2015). Informed pursuit of happiness: what we should know, do know and can get to know. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16 (4), 1035–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9560-1 .

Veenhoven, R. (2017). World database of happiness: archive of research findings on subjective enjoyment of life. Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl .

Veenhoven, R., & Vergunst, F. (2014). The Easterlin illusion: economic growth does go with greater happiness. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1 (4), 311–343. doi: 10.1504/IJHD.2014.066115 .

Wacziarg, R., & Welch, K. H. (2008). Trade liberalization and growth: new evidence. The World Bank Economic Review, 22 (2), 187–231. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhn007 .

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising: human empowerment and the quest for emancipation . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Welzel, C., & Inglehart, R. (2010). Agency, values, and well-being: a human development model. Social Indicators Research, 97 (1), 43–63. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9557-z .

Welzel, C., Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H.-D. (2003). The theory of human development: a cross-cultural analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 42 (3), 341–379. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00086 .

World Bank. (2016). World development indicators 2016 . Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/datacatalog/world-development-indicators .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, School of Business, Monash University Malaysia, Jalan Lagoon Selatan, Bandar Sunway, 47500, Subang Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Amanina Abdur Rahman

Erasmus Happiness Economics Research Organization (EHERO), Erasmus University Rotterdam, P.O. Box 1738, 3000 DR, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Ruut Veenhoven

Opentia Research Program, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Amanina Abdur Rahman .

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: modifications have been made to Tables 2, 3, and 4, captions to Figs. 2 and 3, and hyperlinks to the findings pages on the World Database of Happiness in page 11. Full information regarding corrections made can be found in the erratum for this article.

Ruut Veenhoven is on the Editorial Policy Board of the Applied Research in Quality-of-Life journal, and one of the Board of Directors of the International Society of Quality-of-Life Studies.

Appendix 1: Measures of Economic Freedom

Appendix 2: measures of political freedom.

Example of a findings page in the World Database of Happiness

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Abdur Rahman, A., Veenhoven, R. Freedom and Happiness in Nations: A Research Synthesis. Applied Research Quality Life 13 , 435–456 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9543-6

Download citation

Received : 10 January 2017

Accepted : 24 April 2017

Published : 14 June 2017

Issue Date : June 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9543-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- World Database of Happiness

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Freedom and Equality

Elizabeth Anderson is Arthur F. Thurnau Professor and John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Published: 05 October 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Freedom and equality are often viewed as conflicting values. But there are at least three conceptions of freedom-negative, positive, and republican-and three conceptions of equality-of standing, esteem, and authority. Libertarians argue that rights to negative liberty override claims to positive liberty. However, a freedom-based defense of private property rights must favor positive over negative freedom. Furthermore, a regime of full contractual alienability of rights-on the priority of negative over republican freedom-is an unstable basis for a free society. To sustain a free society over time, republican liberty must take priority over negative liberty, resulting in a kind of authority egalitarianism. Finally, the chapter discusses how the values of freedom and equality bear on the definition of property rights. The result is a qualified defense of some core features of social democratic orders.

Freedom and equality are typically presented as opposing values. In the quick version of the argument, economic liberty—the freedom to make contracts, acquire property, and exchange goods—upsets substantive economic equality ( Nozick, 2013 : 160–164). Suppose some people sail to an uninhabited island and divide its territory and the provisions they brought into shares of equal value. If they are free to produce, trade, and accumulate property, some would rapidly get richer than others due to good luck and good choices, while others would become poor due to bad luck and bad choices. Any attempt to enforce strict material equality across large populations under modern economic conditions would require a totalitarian state. Gracchus Babeuf, a radical of the French Revolution, and the first modern advocate of strict material equality under state communism, understood this perfectly. He saw that the only way to ensure strict material equality was for the state to run society like an army—to control all property and production, assign everyone to their jobs, and control everyone’s thoughts (lest some get the ideas that they deserve more than others, or that they should be free to choose their own way of life) ( Babeuf, 1967 ; Buonarroti, 1836 ). He thought such equality was worth the sacrifice of freedom. Few who have actually lived under communism agree.

While the quick argument is true and of great historical importance, it does not address moderate types of egalitarianism. Virtually no one today advocates strict material equality. Social democrats, particularly in northern Europe, embraced private property and extensive markets well before the collapse of communism. Friedrich Hayek (1944) argued that social democratic experiments would lead societies down the slippery slope to totalitarianism. His prediction failed: moderate egalitarianism of the social democratic type has proved compatible with democracy, extensive civil liberties, and substantial if constrained market freedoms.

To make progress on the question of normative trade-offs between freedom and equality within the range of options for political economy credibly on the table, we must clarify our concepts. There are at least three conceptions of freedom—negative, positive, and republican—and three conceptions of equality—of standing, esteem, and authority. Republican freedom requires extensive authority egalitarianism. To block arguments that freedom requires substantial material equality, libertarians typically argue that rights to negative liberty override or constrain claims to positive liberty. This chapter will argue that, to the extent that libertarians want to support private property rights in terms of the importance of freedom to individuals, this strategy fails, because the freedom-based defense of private property rights depends on giving priority to positive or republican over negative freedom. Next, it is argued that the core rationale for inalienable rights depends on considerations of republican freedom. A regime of full contractual alienability of rights—on the priority of negative over republican freedom—is an unstable basis for a free society. It tends to shrink the domains in which individuals interact as free and independent persons, and expand the domains in which they interact on terms of domination and subordination. To sustain a free society over time, we should accept the priority of republican over negative liberty. This is to endorse a kind of authority egalitarianism. The chapter concludes with some reflections on how the values of freedom and equality bear on the definition of property rights. The result will be a qualified defense of some core features of social democratic orders.

1. Conceptions of Freedom and Equality

Let us distinguish three conceptions of freedom: negative freedom (noninterference), positive freedom (opportunities), and republican freedom (nondomination). Sarah has negative freedom if no one interferes with her actions. She has positive freedom if she has a rich set of opportunities effectively accessible to her. She has republican freedom if she is not dominated by another person—not subject to another’s arbitrary and unaccountable will.

These three conceptions of freedom are logically distinct. They are also somewhat causally independent: one can enjoy high degrees of any two of these freedoms at substantial cost to the third. Lakshmi could have perfect negative and republican freedom on an island in which she is the only inhabitant. No one else would be interfering with her actions or dominating her. She would have little positive freedom, however, since most opportunities are generated in society with others. Maria could have high degrees of negative and positive freedom while lacking republican freedom. She could be the favorite of an indulgent king, who showers her with wealth and privileges, and permits her to say and do what she likes—but who could throw her in his dungeon at his whim. Finally, Sven could have high degrees of positive and republican freedom while being subject to many constraints on his negative liberty. He could reside in an advanced social democratic state such as Norway, where interpersonal authority is constrained by the rule of law (so he is not subject to anyone’s arbitrary will), and a rich set of opportunities is available to all, at the cost of substantial negative liberty constraints through high levels of taxation and economic regulation.

Traditionally, most discussions of freedom focused on the contrast between negative and positive freedom. The recent revival of the republican conception of freedom as nondomination adds an important dimension to thinking about the lived experience of unfreedom and the social conditions of freedom. Pettit (1997 : 22–25) stresses the contrast between negative and republican freedom in the case where a dominator could but chooses not to interfere with subordinates. He argues that such vulnerability to interference can make subordinates submissive, self-censoring, and sycophantic toward their superiors. It is also important to consider some differences between negative liberty constraints imposed by a dominating power and those imposed in accordance with the rule of law by a liberal democratic authority. Domination is often personal: think of the husband under the law of coverture or the violent husband today, the slaveholder, the bullying, micromanaging boss. Rule-of-law constraints are impersonal and of general applicability. This arm’s-length character of the rule of law often relieves people of the humiliation of submission to domination, since they know “it’s not about me.” Dominating interference can arrive unannounced. Rule-of-law constraints must be publicized in advance, giving people time to figure out how to pursue their projects in ways that avoid interference. Dominating interference does not have to justify itself. Rule-of-law constraints in a liberal democratic order must appeal to public reasons, which limits the constraints that can be imposed. Dominating interference is unaccountable. Applied rule-of-law constraints in a democracy are subject to appeal before an impartial adjudicator, and those who enact them can be removed from power by those to whom the constraints apply.

These remarks apply to ideal types only. Actually existing formally liberal democratic regimes have devised innumerable ways to exercise domination under the guise of the rule of law. It is possible to devise a set of impersonal, generally applicable, publicized laws that regulate conduct so minutely that almost anyone innocently going about their business could be found to have run afoul of one of them. Such is the case with traffic laws in the United States. If enforcement action on the trivial infringements were limited to mere warnings or token fines, as in police stops to warn drivers that their tail lights are broken, they could be a service to the drivers and others on the road. Often, however, such traffic stops are a mere pretext for police exercise of arbitrary power to harass, intimidate, invade privacy, and seize people’s property without due process of law. 1 In other cases, impersonal rule-of-law regulations impose constraints so out of touch with local conditions, with such draconian penalties for noncompliance, that enforcement amounts to domination. Such is the case with the high-stakes testing regime imposed by the federal government under No Child Left Behind, with uniform arbitrary progress goals foisted on local school districts without any empirical research demonstrating that these goals were feasible. In some cases, the NCLB regime has created a culture of intimidation and cheating ( Aviv, 2014 ). This is a centralized planning regime akin to the five-year plans of communist states. In both cases, the imposition of goals plucked out of thin air in combination with severe sanctions is premised on the assumption that lack of sufficient will is the primary obstacle to progress—an assumption that rationalizes domination of those required to meet the goals.

We should be skeptical of attempts to operationalize the conditions for nondomination in formal terms. Powerful agents are constantly devising ways to skirt around formal constraints to dominate others. Republican freedom is a sociologically complex condition not easily encapsulated in any simple set of necessary and sufficient conditions, nor easily realized through any particular set of laws.

Turn now to equality. In other work, I have argued that the conceptions of equality relevant for political purposes are relational: they characterize the types of social relations in which members of society stand to one another ( Anderson, 2012b ; Anderson, 2012a ). Relational equality is opposed to social hierarchy. Three types of hierarchy—of standing, esteem, and authority—are particularly important. In hierarchies of standing, agents (including the state) count the interests of superiors highly, and the interests of inferiors for little or nothing. In hierarchies of esteem, some groups monopolize esteem and stigmatize their inferiors. In hierarchies of authority, dominant agents issue arbitrary and unaccountable commands to subordinates, who must obey on pain of sanctions. Egalitarians oppose such hierarchies and aim to replace them with institutions in which persons relate to one another as equals. For example, they want members of society to be treated as equals by the state and in institutions of civil society (standing); to be recognized as bearing equal dignity and respect (esteem); to have equal votes and access to political participation in democratic states (authority). Each of these conceptions of relational equality is complex and implicates numerous features of the social setting.

These three types of hierarchy usually reinforce each other. Groups that exercise power over others tend to enjoy higher esteem, and often use their power to exact special solicitude for their interests from others. Sometimes they come apart. Upper-class married women under the law of coverture enjoyed high esteem and standing, but had little authority and were subordinate to their husbands and to men generally. Some ethnic minorities, such as Chinese Malaysians, enjoy high standing and authority through their ownership and control of most businesses in Malaysia, but are racially stigmatized in Malaysian society.

Given this array of distinct conceptions of freedom and equality, it is harder to argue that freedom and equality are structurally opposed. There is a deep affinity between republican freedom as nondomination and authority egalitarianism. These are not conceptually identical. Domination can be realized in an isolated, transient interpersonal case (consider a kidnapper and his victim). Authoritarian hierarchy is institutionalized, enduring, and group-based. Yet authority hierarchies cause the most important infringements of republican freedom. Historically, the radical republican tradition, from the Levellers to the radical wing of the Republican party through Reconstruction, saw the two causes of freedom and equality as united: to be free was to not be subject to the arbitrary will of others. This required elimination of the authoritarian powers of dominant classes, whether of the king, feudal landlords, or slaveholders. Republican freedom for all is incompatible with authoritarian hierarchy and hence requires some form of authority egalitarianism.

Authority egalitarianism so dominates public discourse in contemporary liberal democracies that few people openly reject it. However, conservatives have traditionally supported authority hierarchy, and continue to do so today, while often publicizing their views in other terms. For example, conservatives tend to defend expansive discretionary powers of police over suspects and employers over workers, as well as policies that reinforce race, class, and gender hierarchies, such as restrictions on voting, reproductive freedom, and access to the courts.

The connections between relational equality and conventional ideas of equality in terms of the distribution of income and wealth are mainly causal. Esteem egalitarians worry that great economic inequality will cause the poor to be stigmatized and the rich glorified simply for their wealth. Authority egalitarians worry that too much wealth inequality empowers the rich to turn the state into a plutocracy. This radical republican objection to wealth inequality is distinct from contemporary notions of distributive justice, which focus on the ideas that unequal distributions are unfair, and that redistribution can enhance the consumption opportunities of the less well off. 2 The latter notions are the concern of standing egalitarianism. Concern for distributive justice—specifically, how the rules that determine the fair division of gains from social cooperation should be designed—can be cast in terms of the question: what rules would free people of equal standing choose, with an eye to also sustaining their equal social relations? The concern to choose principles that sustain relations of equal standing is partly causal and partly constitutive. In a contractualist framework, principles of distributive justice for economic goods constrain the choice of regulative rules of property, contract, the system of money and banking, and so forth, and do not directly determine outcomes ( Rawls, 1999 : 47–49, 73–76). From this point of view, certain principles, such as equality of rights to own property and make contracts, are constitutive of equal standing.

Absent from this list of conceptions of equality is any notion of equality considered as a bare pattern in the distribution of goods, independent of how those goods were brought about, the social relations through which they came to be possessed, or the social relations they tend to cause. Some people think that it is a bad thing if one person is worse off than another due to sheer luck ( Arneson, 2000 ; Temkin, 2003 ). I do not share this intuition. Suppose a temperamentally happy baby is born, and then another is born that is even happier. The first is now worse off than the second, through sheer luck. This fact is no injustice and harms no one’s interests. Nor does it make the world a worse place. Even if it did, it would still be irrelevant in a liberal political order, as concern for the value of the world apart from any connection to human welfare, interests, or freedom fails even the most lax standard of liberal neutrality.

2. A Freedom-based Justification of Property Must Favor Positive or Republican over Negative Freedom

The conventional debate about freedom and distributive equality is cast in terms of the relative priority of negative and positive freedom. If negative liberty, as embodied in property rights, trumps positive freedom, then taxation for purposes of redistribution of income and wealth is unjust ( Nozick, 2013 : 30–34, 172–173; Mack, 2009 ).

One way to motivate the priority of negative freedom is to stress the normative difference between constraints against infringing others’ liberties, which do not require anyone to do anything (merely to refrain from acting in certain ways), and positive requirements to supply others with goods, which carry the taint of forced labor. This argument applies at most to taxation of labor income. Nozick (2013 : 169) tacitly acknowledged this point in claiming that “Taxation of earnings from labor is on a par with forced labor” (emphasis added). People receive passive income (such as interest, mineral royalties, capital gains, land rents, and bequests) without lifting a finger, so taxation of or limitations on such income does not amount to forcing them to work for others. Such taxation is the traditional left-libertarian strategy for pursuing distributive equality consistent with negative liberty constraints. Land and natural resource taxes can be justified in Lockean terms, as respecting the property rights in the commons of those who lost access to privately appropriated land. Paine’s classic version of this argument (1796) claims that Lockean property rights should be unbundled: just appropriation entitles owners to use the land and exclude others, but not to 100 percent of the income from land rents. Citizens generally retain rights to part of that income stream. This grounds a moderate egalitarianism without resort to the extravagant premises needed to support a more demanding distributive equality in libertarian terms, as for instance in Otsuka (1998) .

Arguments for the priority of negative over positive freedom with respect to property rights run into more fundamental difficulties. A regime of perfect negative freedom with respect to property is one of Hohfeldian privileges only, not of rights. 3 A negative liberty is a privilege to act in some way without state interference or liability for damages to another for the way one acts. The correlate to A’s privilege is that others lack any right to demand state assistance in constraining A’s liberty to act in that way. There is nothing conceptually incoherent in a situation where multiple persons have a privilege with respect to the same rival good: consider the rules of basketball, which permit members of either team to compete for possession of the ball, and even to “steal” the ball from opponents. If the other team exercises its liberty to steal the ball, the original possessor cannot appeal to the referee to get it back.

No sound argument for a regime of property rights can rely on considerations of negative liberty alone. Rights entail that others have correlative duties. To have a property right to something is to have a claim against others, enforceable by the state, that they not act in particular ways with respect to that thing. Property rights, by definition, are massive constraints on negative liberty: to secure the right of a single individual owner to some property, the negative liberty of everyone else—billions of people—must be constrained. Judged by a metric of negative liberty alone, recognition of property rights inherently amounts to a massive net loss of total negative freedom. The argument applies equally well to rights in one’s person, showing again the inability of considerations of negative liberty alone to ground rights. “It is impossible to create rights, to impose obligations, to protect the person, life, reputation, property, subsistence, or liberty itself, but at the expense of liberty” ( Bentham, 1838–1843 : I.1, 301).

What could justify this gigantic net loss of negative liberty? If we want to defend this loss as a net gain in overall freedom, we must do so by appealing to one of the other conceptions of freedom—positive freedom, or republican freedom. Excellent arguments can be provided to defend private property rights in terms of positive freedom. Someone who has invested their labor in some external good with the aim of creating something worth more than the original raw materials has a vital interest in assurance that they will have effective access to this good in the future. Such assurance requires the state’s assistance in securing that good against others’ negative liberty interest in taking possession of it. To have a claim to the state’s assistance in securing effective access to a good, against others’ negative liberty interests in it, is to have a right to positive freedom .

Considerations of republican freedom also supply excellent arguments for private property. In a system of privileges alone, contests over possession of external objects would be settled in the interests of the stronger parties. Because individuals need access to external goods to survive, the stronger could then condition others’ access on their subjection to the possessors’ arbitrary will. Only a system of private property rights can protect the weaker from domination by the stronger. The republican argument for rights in one’s own body follows even more immediately from such considerations, since to be an object of others’ possession is per se to be dominated by them.

Thus, there are impeccable freedom-based arguments for individual property rights. But they depend on treating individuals’ interests in either positive or republican freedom as overriding others’ negative liberty interests. Against this, libertarians such as Nozick could argue that the proper conception of negative liberty is a moralized one, such that interference with others’ negative freedom does not count as an infringement of liberty unless it is unjust . Such a moralized view of liberty is implicit in Nozick’s moralized accounts of coercion and voluntariness (1969: 450; 2013: 262–263). Hence, no genuine sacrifice of others’ negative liberty is involved in establishing a just system of property rights.

In response, we must consider what could justify claims to negative liberty rights in property. The problem arises with special clarity once we consider the pervasiveness of prima facie conflicts of property rights, as in cases of externalities settled by tort law or land use regulation. Whenever prima facie negative liberty rights conflict, we must decide between them either by weighing their value in terms of non-liberty considerations, or in terms of some other conception of freedom—positive or republican. If we appeal to considerations other than freedom, we treat freedom as subordinate to other values. For example, desert-based arguments for property rights, which point to the fact that the individual created the object of property, or added value to it through their labor—treat freedom as subordinate to the social goal of rewarding people according to their just deserts. Similarly, Nozick’s resolution of conflicting claims in terms of a moralized notion of negative liberty covertly imports utilitarian considerations to do the needed normative work ( Fried, 2011 ). To base the justification of property rights on considerations of freedom itself, we must regard freedom as a value or interest and not immediately as a right. That is, we must regard freedom as a nonmoralized consideration. Otherwise we have no basis in freedom for justifying property rights or resolving property disputes when uses of property conflict.

A contractualist framework can offer a freedom-based justification of private property rights that departs from libertarian premises. In this picture, the principles of right are whatever principles persons would rationally choose (or could not reasonably reject) to govern their interpersonal claims, given that they are, and understand themselves to be, free and equal in relation to one another. If they chose a regime of privileges only, this would amount to anarchist communism, in which the world is an unregulated commons. Such a regime would lead to depleted commons—razed forests, extinct game, destroyed fisheries. It would also give everyone a greater incentive to take what others produced than to produce themselves. Few would invest their labor in external things, everyone would be poor, and meaningful opportunities would be rare. By contrast, adoption of an institutional scheme of extensive private property rights, including broad freedoms of exchange and contract, would create vastly richer opportunities for peaceful and cooperative production on terms of mutual freedom and equality. All have an overwhelming common interest in sustaining an institutional infrastructure of private property rights that generates more positive freedom —better opportunities—for all.

This argument justifies rights to negative freedom with respect to external property in terms of positive freedom. It does not suppose, as libertarian arguments do, that the liberty interests of the individual override the common interest. Rather, it claims that people have a common interest in sustaining a regime of individual rights to property. On this view, individual rights are not justified by the weight of the individual interest they protect, but by the fact that everyone has a common interest in relating to each other through a shared infrastructure of individual rights ( Raz, 1994 ). The infrastructure of private property rights is a public good, justified by its promotion of opportunities—of positive freedom—for all. A well-designed infrastructure provides a framework within which individuals can relate to one another as free and equal persons.

So far, the argument is one of evaluative priority only. It has been argued that if one wants to justify private property rights in terms of freedom, one must grant evaluative priority to positive or republican over negative freedom. Discussion of the implications of this argument for the content of a just scheme of private property rights—to whether a just scheme would look more libertarian, or more egalitarian—will be postponed to the last section of this chapter.

3. Republican Freedom and the Justification of Inalienable Rights

If negative freedom were the only conception of freedom, it would be difficult to offer a freedom-based justification of inalienable rights. If Sarah’s right is inalienable, then she is immune from anyone changing her right. This could look attractive, except that it entails that she is disabled from changing her own right—that she lacks the power to waive others’ correlative duties to respect that right ( Hohfeld, 1913–1914 : 44–45, 55). This is a constraint on her higher-order negative liberty. This liberty is higher-order because it concerns not the liberty to exercise the right, but the liberty over the right itself.

Inalienable rights might also leave the individual with an inferior set of positive freedoms than if her rights are alienable. Contracts involve an exchange of rights. There is a general presumption that voluntary and informed contracts produce gains for both sides. To make Sarah’s right inalienable prevents her from exchanging it for rights she values more, and thereby reduces her opportunities or positive freedom.

However, there are strategic contexts in which individuals can get much better opportunities if some of their rights are inalienable ( Dworkin, 1982 : 55–56). In urgent situations, when one party cannot hold out for better terms, the other can exploit that fact and offer terms that are much worse than what they would otherwise be willing to offer. Peter, seeing Michelle drowning, might condition his tossing her a life ring on her agreeing to become his slave, if her rights in herself were fully alienable. But if she had an inalienable right to self-ownership, Peter could not exploit her desperation to subject her to slavery, but would offer her better terms.

Such considerations leave libertarians torn between accepting and rejecting the validity of voluntary contracts into slavery. 4 Those tempted by the negative liberty case in favor of full alienability of rights should recall the antislavery arguments of the Republican Party before the Civil War. Republicans objected to slavery because it enabled slaveholders to subordinate even free men to their dominion. The Slave Power—politically organized proslavery interests—undermined the republican character of government. It suppressed the right to petition Congress (via the gag rule against hearing antislavery petitions), censored the mail (against antislavery literature), and forced free men, against their conscience, to join posses to hunt down alleged fugitive slaves. It violated equal citizenship by effectively granting additional representation to slaveowners for their property in slaves (via the three-fifths rule for apportioning representatives). By insisting on the right to hold slaves in the territories, the Slave Power threatened the prospects of free men to secure their independence by staking out individual homesteads. Slave plantations would acquire vast territories, crowding out opportunities for independent family farms. Chattel slavery of blacks threatened to reduce whites to wage slaves, subordinate to their employers for their entire working lives ( Foner, 1995 ).

The Republican antislavery argument is similar to the positive liberty argument above: it stresses how the constitution of a scheme of liberty rights provides the public infrastructure for a society of free and equal persons. The critical point is to institute a scheme of individual rights that can sustain relations of freedom and equality—understood as personal independence and nondomination—among persons. While the Republican Party limited its arguments to securing relations of nondomination among men, feminist abolitionists extended their arguments to married women, who, like slaves, lacked the rights to own property, make contracts, sue and be sued in court, keep their earned income, and move freely without getting permission from their masters (husbands) ( Sklar, 2000 ). Like the positive liberty argument for individual rights, it recognizes how individuals have a vital stake in other people’s liberty rights being secure against invasion or appropriation by others. The stability of this public infrastructure of freedom depends on individual rights being inalienable.

It is to no avail to reply that a libertarian scheme of fully alienable rights that permits voluntary slavery would reject the forced slavery of the antebellum South, along with the violations of free speech and republican government needed to secure the institution of slavery against state “interference.” For the Republicans’ antislavery argument was about the stability of certain rights configurations under realistic conditions. It was that a society that enforces rights to total domination of one person over another will not be able to sustain itself as a free society of equals over time. How the dominators acquired those rights, whether by force or contract, is irrelevant to this argument. Slaveholders, in the name of protection of their private property rights, used the immense economic power they gained from slavery to seize the state apparatus and crush republican liberties. This is a version of the classical republican antiplutocratic argument against extreme wealth inequality. But it was also directed toward the threat that slavery posed to economic independence of free men—to their prospects for self-employment, for freedom from subjection to an employer.

Debra Satz ( 2010 : 180, 232n40), citing Genicot (2002) , offers a similar argument against debt bondage, adapted to contemporary conditions. Two dynamics threaten the ability of workers to maintain their freedom if they have the power to alienate their right to quit to their creditor/employer. First, the availability of debt bondage may restrict opportunities to obtain credit without bondage. Bondage functions as a guarantee against destitute debtors’ default: they put up their own labor as collateral. However, the institution of debt bondage makes it more difficult to establish formalized credit and labor markets by which alternative methods of promoting loan repayment (such as credit ratings and garnishing wages) make credit available without bondage.

Second, living under conditions of bondage makes people servile, humble, and psychologically dependent—psychological dispositions that they are likely to transmit to their children. Servile people lack a vivid conception of themselves as rights-bearers and lack the assertiveness needed to vindicate their rights. Moreover, the poor are unlikely to hang on to their freedom for long, given their strategic vulnerability when others are already giving up their alienable rights under hard bargaining. A system of fully alienable libertarian rights is thus liable to degenerate into a society of lords and bondsmen, unable to reproduce the self-understandings that ground libertarian rights. A free society cannot be sustained by people trained to servility and locked into strategic games where some individuals’ alienation of their liberty rights puts others’ liberties at risk ( Satz, 2010 : 173–180).

This argument generalizes. Workers may have a permanent interest in retaining other rights besides the formal right to quit, so as to prevent the authority relations constitutive of employment from conversion into relations of domination. For example, they have a permanent interest against sexual and other forms of discriminatory harassment. Under U.S. law, workers have inalienable rights against such degrading treatment. In addition, since lower-level workers have minimal freedom at work, but spend their workdays following others’ orders, they have a vital interest in secure access to a limited length of the working day—in having some hours in which they act under their own direction. This is the purpose of maximum hours laws, which forbid employers from conditioning a job offer on having to work too many hours per week. The logic in both cases is strategic: once employers are free to make such unwelcome “offers” (or rather, threats), the decision of some to accept removes better offers from other workers’ choice sets, and thereby deprives them of both positive and republican freedom.

As in the case of contractual slavery, libertarians are divided over this type of argument. Mill (1965 : XI, §12) supported maximum hours laws as an exception to laissez faire, on strategic grounds. The early Nozick would probably have accepted laws against sexual harassment, because conditioning a job on putting up with a hostile atmosphere or compliance with the boss’s sexual demands makes workers worse off relative to a normative baseline of not being subject to unwelcome sexual affronts, and hence counts as coercive. 5 However, the Nozick of Anarchy, State, and Utopia would have rejected such laws as interfering with freedom of contract, given that he accepted contractual slavery. Eric Mack (1981) also upholds an absolute principle of freedom of contract, and so would be committed to the alienability of rights against sexual harassment and even assault in labor contracts.

Mack recognizes that it is disingenuous to claim that restraints on freedom of contract that improve workers’ choice sets violate their freedom of contract. Hence minimum wage laws, if they only raise wages and do not increase unemployment, do not violate workers’ rights. His complaint is that such restraints violate employers’ rights, coercing them into offering better terms to workers than they wanted to make. They treat employers as mere resources to be used by others in pursuit of goals the employer does not share ( Mack, 1981 : 6–8). This argument, if applied to laws against sexual harassment and similar forms of personal domination, is bizarre. One would have thought that employers who threaten their workers with job loss if they do not put up with sexual subordination are treating them as mere resources to be used by the employer in pursuit of goals the workers do not share.

Mack contrasts a morality of “social goals” with one of deontological side constraints, claiming that the former treats people as mere means and the latter treats people as ends in themselves. A deontology of complete alienability of rights in one’s person, however, leads to a society in which some are made others’ partial or total property, reduced to instruments of the others’ arbitrary wills, and deprived of all three kinds of freedom. That they entered such a state by choice does not undermine the conclusion. Rather, it proves that liberty does not only upset equality—it also upsets liberty. To be more precise: negative liberty upsets liberty.

Suppose our “social goal” is to sustain a society in which individuals relate to each other as free persons—which is to say, as equal and independent, not subject to the arbitrary will of others? That would seem to be not merely unobjectionable to a libertarian, but the very point of a libertarian view. The scheme of rights required to realize such a society cannot be devised without tending to the likely consequences of choices made within it. The infrastructure of rights needed to sustain a society in which individuals relate to each other as free persons requires that the rights most fundamental to the ability to exercise independent agency be inalienable, so that no one becomes subject to another’s domination. Thus, the fundamental freedom-based rationale for inalienable rights is based on considerations of republican freedom. It entails that a free society requires substantial authority egalitarianism.

4. Freedom, Equality, and the Definition of Property Rights

I conclude with some remarks on the definition of property rights. Much libertarian writing supposes that as soon as an argument is given to justify a right to private property in something, this justifies all the classical incidents of property—including rights to exclude, use, alter, and destroy it, to give, barter, or sell all or any parts of it or any rights to it, to rent, loan, or lease it for income, all with unlimited duration ( Honoré, 1961 ). Why is a separate argument not required for each of these incidents? Shouldn’t the nature and function of the property in question play a role in determining which rights are attached to it, and for how long? For example, while the right to destroy is easily granted to most chattels, the positive liberty of future generations provides compelling reasons to deny it to property in land and water resources. Such interests also justify limits on dividing property into parcels or rights bundles too small to use ( Heller, 1998 ). It is also questionable how any case for intellectual property rights can be grounded in considerations of negative liberty, given that a regime of universal privilege with respect to ideas does not interfere with the liberties of authors and inventors to create and use their works. A freedom-based case for intellectual property can only be made on positive liberty grounds, and then only justify limited terms for copyrights and patents, given the role of the intellectual commons in expanding cultural and technological opportunities.

A just system of legal rules of property, contract, banking, employment, and so forth constitutes a public infrastructure that can sustain a free society of equals over time. Since, in a well-ordered society, members sustain this infrastructure by paying taxes and complying with its rules, each member has a legitimate claim that the rules secure their access to opportunities generated by that infrastructure. The case is no different from the system of public roads. Fair distributions of access to opportunity matter here, too. A system of roads that accommodates only cars, with no pedestrian sidewalks, crosswalks, and stop lights, denies adequate opportunities for freedom of movement to those without cars. It would be absurd for drivers to object to pedestrian infrastructure because it interferes with their negative liberty. They have no claim that the publicly supported infrastructure be tailored to their interests alone.