ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

A thematic analysis investigating the impact of positive behavioral support training on the lives of service providers: “it makes you think differently”.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 2 Acquired Brain Injury Ireland, Co., Offaly, Ireland

- 3 Future Directions CIC, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom

Positive behavioral support (PBS) employs applied behavioral analysis to enhance the quality of life of people who behave in challenging ways. PBS builds on the straightforward and intuitively appealing notion that if people know how to control their environments, they will have less need to behave in challenging ways. Accordingly, PBS focuses on the perspective of those who have behavioral issues, and assesses success via reduction in incidences of challenging behaviors. The qualitative research presented in this report approaches PBS from a different viewpoint and, using thematic analysis, considers the impact of PBS training on the lived experience of staff who deliver services. Thirteen support staff who work for a company supplying social care and supported living services for people with learning disabilities and complex needs in the northwest of England took part. Analysis of interviews identified five major themes. These were: (1) training: enjoyable and useful; (2) widening of perspective: different ways of thinking; (3) increased competence: better outcomes; (4) spill over into private lives: increased tolerance in relationships; and (5) reflecting on practice and moving to a holistic view: “I am aware that people…are not just being naughty.” These themes evidenced personal growth on the part of service providers receiving training. Explicitly, they demonstrated that greater awareness of PBS equipped recipients with an appropriate set of values, and the technical knowledge required to realize them.

Introduction

Positive behavioral support (PBS) is the application of applied behavioral analysis (ABA) ( Baer et al., 1968 ; Allen et al., 2005 ). Hence, researchers define PBS as “the scientific study of behavior change, using the principles of behavior, to evoke or elicit a targeted behavioral change” ( Furman and Lepper, 2018 , p. 104) in people with challenging behaviors. Its primary goal is to enhance the quality of life of people who behave in challenging ways ( LaVigna and Willis, 2005 ). Hence, a key focus is individual environments. These can be adapted so that challenging behavior is less necessary. Particularly, through the acquisition of more socially effective alternative behaviors, where people are motivated to replace inappropriate, stigmatizing, or destructive ways of responding ( LaVigna and Willis, 2005 ).

The core idea that PBS builds on is straightforward and intuitively appealing: if people know how to control their environments, they will have less need to behave in challenging ways ( Hassiotis et al., 2014 ). PBS imparts this knowledge via instruction, and considers the efficacy of training from the point of view of quality of life of the person behaving in challenging ways, and in terms of reduction in incidences of challenging behaviors (e.g., McClean et al., 2005 ; Walsh et al., 2018 ). In this context, behaving in challenging ways refers to “Culturally abnormal behavior of such intensity, frequency and duration that may put the person or others physical safety in jeopardy or seriously limit the use of community activities” ( Emerson, 2001 , p. 7).

PBS is an important treatment framework in the field of learning disability ( Hassiotis et al., 2014 ; Gore et al., 2019 ). PBS is also a useful approach for those working with teenagers and young adolescents, groups for whom challenging behaviors can have a serious impact on the services that they receive ( Bohanon et al., 2006 ). An important pathway through which challenging behaviors can negatively affect service delivery is via the staff who deliver the services. As such, staff welfare is of fundamental importance ( Williams and Glisson, 2013 ).

Traditionally, expert opinion rather than user-perceptions has driven behavioral interventions ( LaVigna and Willis, 2005 ). In contrast, some theorists switch the focus of PBS to person-focused training of stakeholders (i.e., McClean et al., 2005 ; Grey and McClean, 2007 ), for example, the person presenting with challenging behavior, their families, and service providers. From this perspective, those people impacted by the behavior are paramount – rather than passive recipients of instruction from an “expert.” Stakeholders are active participants in assessment, determining intervention strategies, evaluation of these strategies, and thinking about what outcomes might influence service user’s quality of life ( World Health Organization, 2006 ). In working environments where resources are scarce, even when the benefits of staff training appear evident, justifying incumbent costs can prove difficult ( Dench, 2005 ). In this context, acknowledging the central role of stakeholders with regard to the implementation of PBS ( Dench, 2005 ), it is vital that researchers consider the impact of PBS training on those who deliver the support.

The present study explored how training in PBS affected the lived experience of those receiving training. Thus, it adopted the view that training is a “collaborative project” to which people commit themselves and meaning making is understood as residing between people rather than within individuals. Previous research in PBS has tended to focus on the impact of PBS on incidents of challenging behavior ( Walsh et al., 2018 ). An important, and yet unanswered, question was whether those trained to deliver PBS, with a view to improving the lives of others, experienced any benefit from such training in their own lives.

Materials and Methods

Approach to data collection.

This study, consistent with Braun and Clarke (2006) , used thematic analysis in an open-ended way, to investigate how participants experienced the impact of PBS training in both their professional and private lives. The researchers employed a purposive sampling strategy whereby they engaged with a service provider who delivers PBS training to staff as part of their on-going professional development.

Ethical Protocol

The study received full ethical approval from the Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) ethics committee. All participants provided written informed consent. The study brief informed them that they were free to withdraw at any time, should they wish to do so. Participants consented to the recording of interviews, which were subsequently anonymized and transcribed. Interviews were stored on a password-protected (encrypted) computer, which housed all data.

Interview Process

Participant interviews occurred in their place of work on a prearranged and mutually agreed day. Interviews were semi-structured; a guide provided a loose structure within which to explore the topics of interest. The central question was “what impact has PBS training in the lives of those who receive it?” Where appropriate, the interviewer prompted participants to expand on relevant and interesting responses.

Participants

Purposeful sampling is a widely used technique in qualitative research whereby those cases most likely to be information-rich on the point of interest are selected in order to effectively use limited resources ( Patton, 2002 ). To this end, only staff who had received PBS training were recruited. All staff approached for participation were over the age of 18 and all were permanent employees. The researchers sent an email to potential staff participants requesting volunteers to take part in interviews with regard to their experience of PBS training. A similar advertisement appeared also notice boards in common areas. Respondents participated without incentives. Thirteen participants were interviewed for the purpose of this study. As the goal of the study was to gain a depth of understanding on the point of interest (i.e., participants’ experience of PBS training), through the recruitment of a homogenous 1 sample, data such as mean age etc. are not reported as it might convey the unwarranted impression of generalizability and quantitative robustness.

The service provider delivering the training in PBS was a Community Interest Company providing social care and supported living services for people with learning disabilities and complex needs in the northwest of England. The company is a value-based, high-quality social care provider whose goal is to enable meaningful living among clients. The service provider works with people across a range of environments to provide a continuum of support ranging from a few hours of home care to 24/7 supported living services, and higher levels of support in residential services. All clients are over the age of 16. Supported individuals may have a mental health diagnosis, autism, complex health, profound multiple disabilities, be young people in transition, or have a learning disability, forensic history, acquired brain injury, or dementia.

The company has embedded PBS within service provision. In addition to training staff in PBS, the company has a PBS lead who ensures that staff training remains current. The company also has trained active support champions who facilitate the application of learning to practice.

All staff receive 3-day induction training, which includes consideration of autism, communication, and positive behavioral support. All managers have a level 2 training day covering PBS key components, values, theory, and process. Managers learn also how to develop individual PBS plans, which include functional assessment. PBS plans are evidence based, with 80% of the plan being proactive in order to ensure the achievement of good client outcomes. Training emphasizes that all behavior is for a reason.

All staff receive active support training. This outlines that participation and engagement represent meaningful activities that anybody can engage. The service provider has PBS champions that support staff practically in their job, ensuring that active support is embedded as part of the culture. This role ensures the people supported are empowered in their environment regardless of their ability and actively participate and engage in every part of their life.

Additionally, the company distributes Monthly Newsletters to staff as an additional teaching aid. These share good news stories including information on telecare and other technology designed to give people more choice and control over their lives. Alongside this, training facilitators provide further specialist training. Finally, teams use a training DVD produced by service users to embed staff training.

Data Analysis

This study used thematic analysis ( Braun and Clarke, 2006 ). This required the transcription of interview recordings and followed coding stages. Initially, the authors read and re-read transcripts in order to identify potential themes, which they then forwarded to the lead author. The second level of analysis involved both the first and last authors reviewing these initial codes. They considered particularly how to retain the diversity of the initial codes, while producing overarching elements, higher level sub-themes. The research question, the impact of PBS training in the lives of participants, informed this process. At the third stage, analysis conducted by the first and last authors identified quotes that were congruent with the overarching themes. Next, the authors reviewed themes prior to defining and naming them. Finally, once themes were finalized, by the first and last authors, the write-up of the report began.

The analysis produced five themes.

Training: Enjoyable and Useful

Almost all participants reported that the training that they received was both enjoyable and useful. Illustrative examples appear below.

One participant stated:

MOLLY: I really enjoyed the course and everything and it did make me understand a little bit more.

Participants highlight the enjoyment that they derive from their PBS training course and they explicitly tie this enjoyment to their capacity to internalize it.

ANN: Just listen. Enjoy it. You’ll take something from it even if you do not realize that you do. You think back to what it actually was and you realize that you did take a lot from it.

Widening of Perspective: “Different Ways of Thinking”

In their accounts, most participants highlighted how their perspectives broadened following PBS training.

CATH: “ This is a different way of thinking and getting staff to think differently.”

Participants gave examples of changes in their thinking such as exploring why a person might be upset (Molly), looking for triggers (Maria) being more aware of the possibilities for support in a given moment (p1, Ann) and many participants noted a widening of perspective:

ZOE: “ I see it differently now when somebody is getting anxious. We only see people for a short time. Not that we would leave anybody anxious but it makes you think differently. Thinking outside the box.”

“Increased Competence: Better Outcomes”

A third theme is perceptions of increased competence, and the role of increased competence in promoting better client outcomes.

HEATHER: “ I know what to do in a certain situation whereas some people who hadn’t had it wouldn’t know what to do.”

Participants noted more detailed understanding of triggers (Freya) and better ability to read the communicative intent of clients (Molly). One participant reported that clients “ don’t get to that agitated point like you can prevent it from happening because you know that the reason they are, like, representing the challenging behavior is that they want something or something’s annoyed them.” (Ann).

Other participants reported better outcomes for clients as a result:

ROBIN: “ One person I support has been with [service provider] for 11 years and has always been supported 1:1. I would say roughly he was having 3 incidents a week. (Since PBS was introduced) he has been going out on his own now for 2 months on local walks, walking 2 miles. I don’t think we have had incidents in 2 months. PBS has made it easier, the paperwork side, trying to show staff they wouldn’t be at fault. The staff were scared. I was 5, 6 years ago, but when you come to think about it, it’s better for the person.”

Spill Over Into Private Lives: Increased Tolerance in Relationships

Many participants describe the impact PBS training made in their lives beyond the workplace. Participants say they can apply the principles directly with their family members.

MARIA: “ At home, my children … will come to talk to me, they need attention, and I say ‘I’m talking on the phone, you have to wait’, but now, instead of shouting at them I give them attention but not stop, ask them to write it and come to me, then I will tell you what to do.... To know that there is a reason for any behavior, and how to handle it.”

MAUREEN: “ It (PBS training) has impacted on outside as my partner has high anxiety levels. I have looked at triggers, I have tried to reduce his anxieties using PBS and the techniques.”

ANN: My sister, my middle sister, she’s got learning disabilities. So, like, cos it is simple things like you have got to recognize that most of the challenging behavior is because they are trying to communicate something. Even that feel good factor, or they are just doing it to release some stimulation. But you just need to realize that there is a reason behind all of it, is not there? It’s not just the naughty child, or whatever people use as an excuse.

In terms of indirect impact on participants’ private lives, they spoke about being less judgmental and more effective in their close personal relationships after PBS training:

MARIA: I apply it in my everyday life, especially to be non-judgemental.

ZOE: Yes, because when I had the training we talked about when you have a bad day how you would react, and how your partner would (react) to you…(as a result) I tried something different.

Deeper Understanding of People

Participants reflected on a theme that their philosophy of people had changed. For example, they noted a different attitude to behaviors outside work.

HEATHER: “ I’m aware of people when I’m out (outside of work) that they have got behavioral problems and they’re not just being naughty.”

Commensurate with this change in philosophy is a different or deeper understanding of how people need to be treated.

ANN: It’s encouragement, rather than punishment. That’s what I have taken from it, less telling off and more understanding and encouragement .

Traditionally, expert opinion rather than user-perceptions has driven behavioral interventions ( LaVigna and Willis, 2005 ). Training in PBS is important because it switches focus to the training of stakeholders. The impact of PBS training on staff has been under researched ( Dench, 2005 ). Dench (2005) argues that organizational best practice means that personal development should link to institutional goals and that training evaluation should include qualitative perspectives. It was therefore vital to consider the impact training in PBS has on staff from a qualitative point of view. Staff are key stakeholders and active participants in assessment, determining intervention strategies, evaluation of these strategies, and thinking about what outcomes might affect service user’s quality of life. Vygotsky regarded learning as the ingrowing of lived experience into personal meaning, an outside-in approach ( Frawley, 1997 ). This outside-in perspective lends itself readily to a consideration of how being trained in PBS influences the lived experience of those receiving training. Our results show, within the cohort sampled, that the impact on individuals was overwhelmingly positive.

Specifically, the participants in our research reported that PBS training was enjoyable. This was the case at both emotional and cognitive levels, where training represented both participant’s experience as well as its environmental context ( Wankel, 1993 ). Thus, consistent with Dench (2005) , enjoyment constituted a framework for further embedding training content. Participants also described a widening of perspective – this experience is consistent with the person-based focus advocated by PBS. Moreover, a widening perspective is congruent with the approach advocated by educationalists who build on Vygotsky’s legacy to move education and training away from a focus on test performance to addressing individual capabilities in a grounded and creative manner (e.g., Craft et al., 2008 ).

PBS training is perhaps best conceived as a “collaborative project”, an aggregate of actions that are directed toward an aim. However, at the same time, a project is not equated with its aim, “a unit of educative work in which the most prominent feature was some form of positive and concrete achievement”. Participant 8 spoke about a client who had shifted from three incidents of challenging behavior per week pre PBS training to a position where the client is now going out, unaccompanied, for 2-mile walks.

When a project manages to achieve relatively permanent changes in the social practices of a community, it evolves from being a social movement into an institution. This fits well with Dench (2005) , who argues that best practice in training leads to an integration between human resource development and management policies and processes. There was evidence that this was indeed the case with our participants. For example, one participant expressed a desire to have all staff undergo PBS training at induction, and for the implementation of annual refresher training. Participants described also how the benefits of PBS training have “spilled over” into their private lives. Specifically, people who received training described how their marital, sibling, and parental relationships improved. Increased self-efficacy ( Bandura, 1997 ) is a key factor in how individuals’ personal development opportunities link to specified organizational goals.

Our final theme pertained to the deeper understanding of people whom participants describe because of their training. Several of those interviewed made reference to moving beyond considerations based around ideas of people “being naughty” and reflected on a move to a more holistic approach, where their attitude was significantly less judgmental, efficacious, and increasingly tolerant [e.g., “I apply it in my everyday life, especially to be non-judgemental. To know that there is a reason for any behavior and how to handle it” ( Gore et al., 2013 )].

These themes all appear to link with the concept of perceived control, and perceptions of personal control are key to managing both work and home environments in positive ways. According to Bandura (1997) , knowing how to develop and exercise efficacy is a useful basis for well-being enhancement. Social norms convey standards of conduct, when participants adopt these, as they clearly did in the present study, a self-regulatory system consistent with these standards emerges ( Bandura, 1986 ). From an organizational perspective, this last point is key. Training staff in PBS produced elevated perceptions of increased control. Such perceived control is of benefit to both the individuals and their organization ( Bandura, 1997 ). In the current climate, where resources are scarce, all expenditure, including that on training, must, and should, be fully justified. The results of the current study clearly suggest that training staff in PBS offers benefits at the level of service provision as well as at both personal and corporate levels.

Limitations and Future Research

The present paper identified the importance of perceived control. This is an important finding, which requires cautious interpretation because researchers define perceived control in different ways ( Chipperfield et al., 2012 ). Some employ the classic definition, which refers to beliefs about influence. Other theorists prefer a liberal interpretation that denotes perceived control as a psychological state of control. The emphasis with this delineation is whether individuals feels “in or out of” control. The former conceptualization focuses on specific outcomes, whereas the latter is broad and general. This distinction is one which might usefully be considered in future studies. Of importance will be investigating the extent to which vocational training increases perceived control across life domains. The implicit assumption within the present paper was that the benefits were broad (extended beyond practice to family and relationships generally). However, this is difficult to establish without further consideration of different contexts/situations.

In addition, other factors limit the generalizability of findings presented in this report. Specifically, conclusions derive from a small-scale qualitative study centering on a single service provider. Consequently, it is unclear whether the observed benefits extend across service providers and organizations. This is something that subsequent studies should investigate. This could include evaluation of similar service providers, service providers generally, and extend eventually to consider the benefits of occupational training. Clearly, if research evidences that training benefits both clients and practitioners, this from a vocational and practical perspective indicates that it necessitates resourcing.

Noting the limited scope of the current study, further work could examine the outcomes using larger samples and relevant objective psychometric measures, for example, scales assessing perceived control, self-efficacy, and well-being. Longitudinal analysis might establish causal relationships and reveal whether benefits sustained over time. Furthermore, larger samples allow the testing of predictive relationships and the development of models.

Acknowledging these limitations, readers should best consider the study findings in terms of transferability rather than in terms of generalizability. It is also necessary to put on the record the specific interests of the author and research team, which may have inadvertently influenced both the content and findings presented in this report. In particular, their interest and in the service provider and the accompanying community psychology project.

PBS training equips those who receive it with a set of values, as well as the technical knowledge required to realize those values ( Walsh et al., 2018 ). An important goal of PBS training, in common with training in all fields, is that the training is internalized by those who receive it in order to widen their perspectives and contribute positively to wider institutional and societal well-being. There is evidence that the training has been internalized, in Vygotsky’s sense of the inter-psychological becoming the intra-psychological. Staff understand themselves as having benefitted from PBS training and they believe this benefit extending beyond their professional lives. This perceived gain speaks to the importance of training. Particularly, it evidences the positive impact it has on both the lives of those who receive it as well as on the lives of those around them. As such, PBS training fits with a holistic approach to service provision that is mindful of the importance of caregiver well-being in addition to client well-being (see MacDonald and McGill, 2013 ). In sum, what the themes identified in this research evidence, and share, is growth on the part of those who received training in PBS.

Ethics Statement

The study received full ethical approval from MMU ethics committee. Participants were advised that they were free to withdraw at any time, should they wish to do so. All interviews were recorded with the permission of participants and they were later anonymized and transcribed. Anonymized interviews were stored on a password-protected computer for later analysis.

Author Contributions

NDa, S-JS-L, and SR collected data. All authors participated in thematic analysis. RW, BM, and NDa wrote up the final report with feedback and contribution from all authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Homogenous on the point of interest – PBS training.

Allen, D., James, W., Evans, J., Hawkins, S., and Jenkins, R. (2005). Positive behavioural support: definition, current status and future directions. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 10, 4–11. doi: 10.1108/13595474200500014

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., and Risley, T. (1968). Current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1, 91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (ed.) (1997). Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. Self-efficacy in changing societies (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press), 1–45.

Bohanon, H., Fenning, P., Carney, K. L., Minnis-Kim, M. J., Anderson-Harriss, S., Moroz, K. B., et al. (2006). Schoolwide application of positive behavior support in an urban high school: a case study. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 8, 131–145. doi: 10.1177/10983007060080030201

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chipperfield, J. G., Newall, N. E., Perry, R. P., Stewart, T. L., Bailis, D. S., and Ruthig, J. C. (2012). Sense of control in late life: health and survival implications. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1081–1092. doi: 10.1177/0146167212444758

Craft, A., Chappell, K., and Twining, P. (2008). Learners reconceptualising education: widening participation through creative engagement? Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 45, 235–245. doi: 10.1080/14703290802176089

Dench, C. (2005). A model for training staff in positive behaviour support. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 10, 24–30. doi: 10.1108/13595474200500017

Emerson, E. (2001). Challenging behaviour: Analysis and intervention in people with severe intellectual disabilities . Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Frawley, W. (1997). Vygotsky and cognitive science . London: Harvard University Press.

Furman, T. M., and Lepper, T. L. (2018). Applied behavior analysis: definitional difficulties. Psychol. Rec. 68, 103–105. doi: 10.1007/s40732-018-0282-3

Gore, N. J., McGill, P., and Hastings, R. P. (2019). Making it meaningful: caregiver goal selection in positive behavioral support. J. Child Fam. Stud. 28, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01398-5

Gore, N. J., McGill, P., Toogood, S., Allen, D., Hughes, J. C., Baker, P., et al. (2013). Definition and scope for positive behavioural support. Int. J. Posit. Behav. Support 3, 14–23.

Grey, I. M., and McClean, B. (2007). Service user outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support using person-focused training: a control group study. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 20, 6–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00335.x

Hassiotis, A., Strydom, A., Crawford, M., Hall, I., Omar, R., Vickerstaff, V., et al. (2014). Clinical and cost effectiveness of staff training in positive behaviour support (PBS) for treating challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 14, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0219-6

LaVigna, G., and Willis, T. (2005). A positive behavioural support model for breaking the barriers to social and community inclusion. Tizard Learn. Disabil. Rev. 10, 16–23. doi: 10.1108/13595474200500016

MacDonald, A., and McGill, P. (2013). Outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support: a systematic review. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 25, 17–33. doi: 10.1007/s10882-012-9327-8

McClean, B., Dench, C., Grey, I., Shanahan, S., Fitzsimons, E., Hendler, J., et al. (2005). Person focused training: a model for delivering positive behavioural supports to people with challenging behaviours. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 49, 340–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00669.x

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods . 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Walsh, S., Dagnall, N., Ryan, S., Doyle, N., Scarbrough-Lang, S., and McClean, B. (2018). Investigating the impact of staff training in positive behavioural support on service users’ quality of life. Learn. Disabil. Pract. 21, 25–29. doi: 10.7748/ldp.2018.e1902

Wankel, L. M. (1993). The importance of enjoyment to adherence and psychological benefits from physical activity. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 24, 151–169.

Williams, N. J., and Glisson, C. (2013). Reducing turnover is not enough: the need for proficient organizational cultures to support positive youth outcomes in child welfare. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 35, 1871–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.09.002

World Health Organization (2006). Quality of care: A process for making strategic choices in health systems . World Health Organization.

Keywords: positive behavioral support (PBS), training, thematic analysis, staff experience, challenging behavior

Citation: Walsh RS, McClean B, Doyle N, Ryan S, Scarborough-Lang S-J, Rishton A and Dagnall N (2019) A Thematic Analysis Investigating the Impact of Positive Behavioral Support Training on the Lives of Service Providers: “It Makes You Think Differently”. Front. Psychol . 10:2408. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02408

Received: 11 January 2019; Accepted: 09 October 2019; Published: 29 October 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Walsh, McClean, Doyle, Ryan, Scarborough-Lang, Rishton and Dagnall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: R. Stephen Walsh, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Practical thematic...

Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis

- Related content

- Peer review

- Catherine H Saunders , scientist and assistant professor 1 2 ,

- Ailyn Sierpe , research project coordinator 2 ,

- Christian von Plessen , senior physician 3 ,

- Alice M Kennedy , research project manager 2 4 ,

- Laura C Leviton , senior adviser 5 ,

- Steven L Bernstein , chief research officer 1 ,

- Jenaya Goldwag , resident physician 1 ,

- Joel R King , research assistant 2 ,

- Christine M Marx , patient associate 6 ,

- Jacqueline A Pogue , research project manager 2 ,

- Richard K Saunders , staff physician 1 ,

- Aricca Van Citters , senior research scientist 2 ,

- Renata W Yen , doctoral student 2 ,

- Glyn Elwyn , professor 2 ,

- JoAnna K Leyenaar , associate professor 1 2

- on behalf of the Coproduction Laboratory

- 1 Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 2 Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 3 Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté), Lausanne, Switzerland

- 4 Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- 5 Highland Park, NJ, USA

- 6 Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA

- Correspondence to: C H Saunders catherine.hylas.saunders{at}dartmouth.edu

- Accepted 26 April 2023

Qualitative research methods explore and provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, including people’s beliefs, perspectives, and experiences. Whether through analysis of interviews, focus groups, structured observation, or multimedia data, qualitative methods offer unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. However, many clinicians and researchers hesitate to use these methods, or might not use them effectively, which can leave relevant areas of inquiry inadequately explored. Thematic analysis is one of the most common and flexible methods to examine qualitative data collected in health services research. This article offers practical thematic analysis as a step-by-step approach to qualitative analysis for health services researchers, with a focus on accessibility for patients, care partners, clinicians, and others new to thematic analysis. Along with detailed instructions covering three steps of reading, coding, and theming, the article includes additional novel and practical guidance on how to draft effective codes, conduct a thematic analysis session, and develop meaningful themes. This approach aims to improve consistency and rigor in thematic analysis, while also making this method more accessible for multidisciplinary research teams.

Through qualitative methods, researchers can provide deep contextual understanding of real world issues, and generate new knowledge to inform hypotheses, theories, research, and clinical care. Approaches to data collection are varied, including interviews, focus groups, structured observation, and analysis of multimedia data, with qualitative research questions aimed at understanding the how and why of human experience. 1 2 Qualitative methods produce unique insights in applied health services research that other approaches cannot deliver. In particular, researchers acknowledge that thematic analysis is a flexible and powerful method of systematically generating robust qualitative research findings by identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. 3 4 5 6 Although qualitative methods are increasingly valued for answering clinical research questions, many researchers are unsure how to apply them or consider them too time consuming to be useful in responding to practical challenges 7 or pressing situations such as public health emergencies. 8 Consequently, researchers might hesitate to use them, or use them improperly. 9 10 11

Although much has been written about how to perform thematic analysis, practical guidance for non-specialists is sparse. 3 5 6 12 13 In the multidisciplinary field of health services research, qualitative data analysis can confound experienced researchers and novices alike, which can stoke concerns about rigor, particularly for those more familiar with quantitative approaches. 14 Since qualitative methods are an area of specialisation, support from experts is beneficial. However, because non-specialist perspectives can enhance data interpretation and enrich findings, there is a case for making thematic analysis easier, more rapid, and more efficient, 8 particularly for patients, care partners, clinicians, and other stakeholders. A practical guide to thematic analysis might encourage those on the ground to use these methods in their work, unearthing insights that would otherwise remain undiscovered.

Given the need for more accessible qualitative analysis approaches, we present a simple, rigorous, and efficient three step guide for practical thematic analysis. We include new guidance on the mechanics of thematic analysis, including developing codes, constructing meaningful themes, and hosting a thematic analysis session. We also discuss common pitfalls in thematic analysis and how to avoid them.

Summary points

Qualitative methods are increasingly valued in applied health services research, but multidisciplinary research teams often lack accessible step-by-step guidance and might struggle to use these approaches

A newly developed approach, practical thematic analysis, uses three simple steps: reading, coding, and theming

Based on Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, our streamlined yet rigorous approach is designed for multidisciplinary health services research teams, including patients, care partners, and clinicians

This article also provides companion materials including a slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams, a sample thematic analysis session agenda, a theme coproduction template for use during the session, and guidance on using standardised reporting criteria for qualitative research

In their seminal work, Braun and Clarke developed a six phase approach to reflexive thematic analysis. 4 12 We built on their method to develop practical thematic analysis ( box 1 , fig 1 ), which is a simplified and instructive approach that retains the substantive elements of their six phases. Braun and Clarke’s phase 1 (familiarising yourself with the dataset) is represented in our first step of reading. Phase 2 (coding) remains as our second step of coding. Phases 3 (generating initial themes), 4 (developing and reviewing themes), and 5 (refining, defining, and naming themes) are represented in our third step of theming. Phase 6 (writing up) also occurs during this third step of theming, but after a thematic analysis session. 4 12

Key features and applications of practical thematic analysis

Step 1: reading.

All manuscript authors read the data

All manuscript authors write summary memos

Step 2: Coding

Coders perform both data management and early data analysis

Codes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Step 3: Theming

Researchers host a thematic analysis session and share different perspectives

Themes are complete thoughts or sentences, not categories

Applications

For use by practicing clinicians, patients and care partners, students, interdisciplinary teams, and those new to qualitative research

When important insights from healthcare professionals are inaccessible because they do not have qualitative methods training

When time and resources are limited

Steps in practical thematic analysis

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

We present linear steps, but as qualitative research is usually iterative, so too is thematic analysis. 15 Qualitative researchers circle back to earlier work to check whether their interpretations still make sense in the light of additional insights, adapting as necessary. While we focus here on the practical application of thematic analysis in health services research, we recognise our approach exists in the context of the broader literature on thematic analysis and the theoretical underpinnings of qualitative methods as a whole. For a more detailed discussion of these theoretical points, as well as other methods widely used in health services research, we recommend reviewing the sources outlined in supplemental material 1. A strong and nuanced understanding of the context and underlying principles of thematic analysis will allow for higher quality research. 16

Practical thematic analysis is a highly flexible approach that can draw out valuable findings and generate new hypotheses, including in cases with a lack of previous research to build on. The approach can also be used with a variety of data, such as transcripts from interviews or focus groups, patient encounter transcripts, professional publications, observational field notes, and online activity logs. Importantly, successful practical thematic analysis is predicated on having high quality data collected with rigorous methods. We do not describe qualitative research design or data collection here. 11 17

In supplemental material 1, we summarise the foundational methods, concepts, and terminology in qualitative research. Along with our guide below, we include a companion slide presentation for teaching practical thematic analysis to research teams in supplemental material 2. We provide a theme coproduction template for teams to use during thematic analysis sessions in supplemental material 3. Our method aligns with the major qualitative reporting frameworks, including the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). 18 We indicate the corresponding step in practical thematic analysis for each COREQ item in supplemental material 4.

Familiarisation and memoing

We encourage all manuscript authors to review the full dataset (eg, interview transcripts) to familiarise themselves with it. This task is most critical for those who will later be engaged in the coding and theming steps. Although time consuming, it is the best way to involve team members in the intellectual work of data interpretation, so that they can contribute to the analysis and contextualise the results. If this task is not feasible given time limitations or large quantities of data, the data can be divided across team members. In this case, each piece of data should be read by at least two individuals who ideally represent different professional roles or perspectives.

We recommend that researchers reflect on the data and independently write memos, defined as brief notes on thoughts and questions that arise during reading, and a summary of their impressions of the dataset. 2 19 Memoing is an opportunity to gain insights from varying perspectives, particularly from patients, care partners, clinicians, and others. It also gives researchers the opportunity to begin to scope which elements of and concepts in the dataset are relevant to the research question.

Data saturation

The concept of data saturation ( box 2 ) is a foundation of qualitative research. It is defined as the point in analysis at which new data tend to be redundant of data already collected. 21 Qualitative researchers are expected to report their approach to data saturation. 18 Because thematic analysis is iterative, the team should discuss saturation throughout the entire process, beginning with data collection and continuing through all steps of the analysis. 22 During step 1 (reading), team members might discuss data saturation in the context of summary memos. Conversations about saturation continue during step 2 (coding), with confirmation that saturation has been achieved during step 3 (theming). As a rule of thumb, researchers can often achieve saturation in 9-17 interviews or 4-8 focus groups, but this will vary depending on the specific characteristics of the study. 23

Data saturation in context

Braun and Clarke discourage the use of data saturation to determine sample size (eg, number of interviews), because it assumes that there is an objective truth to be captured in the data (sometimes known as a positivist perspective). 20 Qualitative researchers often try to avoid positivist approaches, arguing that there is no one true way of seeing the world, and will instead aim to gather multiple perspectives. 5 Although this theoretical debate with qualitative methods is important, we recognise that a priori estimates of saturation are often needed, particularly for investigators newer to qualitative research who might want a more pragmatic and applied approach. In addition, saturation based, sample size estimation can be particularly helpful in grant proposals. However, researchers should still follow a priori sample size estimation with a discussion to confirm saturation has been achieved.

Definition of coding

We describe codes as labels for concepts in the data that are directly relevant to the study objective. Historically, the purpose of coding was to distil the large amount of data collected into conceptually similar buckets so that researchers could review it in aggregate and identify key themes. 5 24 We advocate for a more analytical approach than is typical with thematic analysis. With our method, coding is both the foundation for and the beginning of thematic analysis—that is, early data analysis, management, and reduction occur simultaneously rather than as different steps. This approach moves the team more efficiently towards being able to describe themes.

Building the coding team

Coders are the research team members who directly assign codes to the data, reading all material and systematically labelling relevant data with appropriate codes. Ideally, at least two researchers would code every discrete data document, such as one interview transcript. 25 If this task is not possible, individual coders can each code a subset of the data that is carefully selected for key characteristics (sometimes known as purposive selection). 26 When using this approach, we recommend that at least 10% of data be coded by two or more coders to ensure consistency in codebook application. We also recommend coding teams of no more than four to five people, for practical reasons concerning maintaining consistency.

Clinicians, patients, and care partners bring unique perspectives to coding and enrich the analytical process. 27 Therefore, we recommend choosing coders with a mix of relevant experiences so that they can challenge and contextualise each other’s interpretations based on their own perspectives and opinions ( box 3 ). We recommend including both coders who collected the data and those who are naive to it, if possible, given their different perspectives. We also recommend all coders review the summary memos from the reading step so that key concepts identified by those not involved in coding can be integrated into the analytical process. In practice, this review means coding the memos themselves and discussing them during the code development process. This approach ensures that the team considers a diversity of perspectives.

Coding teams in context

The recommendation to use multiple coders is a departure from Braun and Clarke. 28 29 When the views, experiences, and training of each coder (sometimes known as positionality) 30 are carefully considered, having multiple coders can enhance interpretation and enrich findings. When these perspectives are combined in a team setting, researchers can create shared meaning from the data. Along with the practical consideration of distributing the workload, 31 inclusion of these multiple perspectives increases the overall quality of the analysis by mitigating the impact of any one coder’s perspective. 30

Coding tools

Qualitative analysis software facilitates coding and managing large datasets but does not perform the analytical work. The researchers must perform the analysis themselves. Most programs support queries and collaborative coding by multiple users. 32 Important factors to consider when choosing software can include accessibility, cost, interoperability, the look and feel of code reports, and the ease of colour coding and merging codes. Coders can also use low tech solutions, including highlighters, word processors, or spreadsheets.

Drafting effective codes

To draft effective codes, we recommend that the coders review each document line by line. 33 As they progress, they can assign codes to segments of data representing passages of interest. 34 Coders can also assign multiple codes to the same passage. Consensus among coders on what constitutes a minimum or maximum amount of text for assigning a code is helpful. As a general rule, meaningful segments of text for coding are shorter than one paragraph, but longer than a few words. Coders should keep the study objective in mind when determining which data are relevant ( box 4 ).

Code types in context

Similar to Braun and Clarke’s approach, practical thematic analysis does not specify whether codes are based on what is evident from the data (sometimes known as semantic) or whether they are based on what can be inferred at a deeper level from the data (sometimes known as latent). 4 12 35 It also does not specify whether they are derived from the data (sometimes known as inductive) or determined ahead of time (sometimes known as deductive). 11 35 Instead, it should be noted that health services researchers conducting qualitative studies often adopt all these approaches to coding (sometimes known as hybrid analysis). 3

In practical thematic analysis, codes should be more descriptive than general categorical labels that simply group data with shared characteristics. At a minimum, codes should form a complete (or full) thought. An easy way to conceptualise full thought codes is as complete sentences with subjects and verbs ( table 1 ), although full sentence coding is not always necessary. With full thought codes, researchers think about the data more deeply and capture this insight in the codes. This coding facilitates the entire analytical process and is especially valuable when moving from codes to broader themes. Experienced qualitative researchers often intuitively use full thought or sentence codes, but this practice has not been explicitly articulated as a path to higher quality coding elsewhere in the literature. 6

Example transcript with codes used in practical thematic analysis 36

- View inline

Depending on the nature of the data, codes might either fall into flat categories or be arranged hierarchically. Flat categories are most common when the data deal with topics on the same conceptual level. In other words, one topic is not a subset of another topic. By contrast, hierarchical codes are more appropriate for concepts that naturally fall above or below each other. Hierarchical coding can also be a useful form of data management and might be necessary when working with a large or complex dataset. 5 Codes grouped into these categories can also make it easier to naturally transition into generating themes from the initial codes. 5 These decisions between flat versus hierarchical coding are part of the work of the coding team. In both cases, coders should ensure that their code structures are guided by their research questions.

Developing the codebook

A codebook is a shared document that lists code labels and comprehensive descriptions for each code, as well as examples observed within the data. Good code descriptions are precise and specific so that coders can consistently assign the same codes to relevant data or articulate why another coder would do so. Codebook development is iterative and involves input from the entire coding team. However, as those closest to the data, coders must resist undue influence, real or perceived, from other team members with conflicting opinions—it is important to mitigate the risk that more senior researchers, like principal investigators, exert undue influence on the coders’ perspectives.

In practical thematic analysis, coders begin codebook development by independently coding a small portion of the data, such as two to three transcripts or other units of analysis. Coders then individually produce their initial codebooks. This task will require them to reflect on, organise, and clarify codes. The coders then meet to reconcile the draft codebooks, which can often be difficult, as some coders tend to lump several concepts together while others will split them into more specific codes. Discussing disagreements and negotiating consensus are necessary parts of early data analysis. Once the codebook is relatively stable, we recommend soliciting input on the codes from all manuscript authors. Yet, coders must ultimately be empowered to finalise the details so that they are comfortable working with the codebook across a large quantity of data.

Assigning codes to the data

After developing the codebook, coders will use it to assign codes to the remaining data. While the codebook’s overall structure should remain constant, coders might continue to add codes corresponding to any new concepts observed in the data. If new codes are added, coders should review the data they have already coded and determine whether the new codes apply. Qualitative data analysis software can be useful for editing or merging codes.

We recommend that coders periodically compare their code occurrences ( box 5 ), with more frequent check-ins if substantial disagreements occur. In the event of large discrepancies in the codes assigned, coders should revise the codebook to ensure that code descriptions are sufficiently clear and comprehensive to support coding alignment going forward. Because coding is an iterative process, the team can adjust the codebook as needed. 5 28 29

Quantitative coding in context

Researchers should generally avoid reporting code counts in thematic analysis. However, counts can be a useful proxy in maintaining alignment between coders on key concepts. 26 In practice, therefore, researchers should make sure that all coders working on the same piece of data assign the same codes with a similar pattern and that their memoing and overall assessment of the data are aligned. 37 However, the frequency of a code alone is not an indicator of its importance. It is more important that coders agree on the most salient points in the data; reviewing and discussing summary memos can be helpful here. 5

Researchers might disagree on whether or not to calculate and report inter-rater reliability. We note that quantitative tests for agreement, such as kappa statistics or intraclass correlation coefficients, can be distracting and might not provide meaningful results in qualitative analyses. Similarly, Braun and Clarke argue that expecting perfect alignment on coding is inconsistent with the goal of co-constructing meaning. 28 29 Overall consensus on codes’ salience and contributions to themes is the most important factor.

Definition of themes

Themes are meta-constructs that rise above codes and unite the dataset ( box 6 , fig 2 ). They should be clearly evident, repeated throughout the dataset, and relevant to the research questions. 38 While codes are often explicit descriptions of the content in the dataset, themes are usually more conceptual and knit the codes together. 39 Some researchers hypothesise that theme development is loosely described in the literature because qualitative researchers simply intuit themes during the analytical process. 39 In practical thematic analysis, we offer a concrete process that should make developing meaningful themes straightforward.

Themes in context

According to Braun and Clarke, a theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set.” 4 Similarly, Braun and Clarke advise against themes as domain summaries. While different approaches can draw out themes from codes, the process begins by identifying patterns. 28 35 Like Braun and Clarke and others, we recommend that researchers consider the salience of certain themes, their prevalence in the dataset, and their keyness (ie, how relevant the themes are to the overarching research questions). 4 12 34

Use of themes in practical thematic analysis

Constructing meaningful themes

After coding all the data, each coder should independently reflect on the team’s summary memos (step 1), the codebook (step 2), and the coded data itself to develop draft themes (step 3). It can be illuminating for coders to review all excerpts associated with each code, so that they derive themes directly from the data. Researchers should remain focused on the research question during this step, so that themes have a clear relation with the overall project aim. Use of qualitative analysis software will make it easy to view each segment of data tagged with each code. Themes might neatly correspond to groups of codes. Or—more likely—they will unite codes and data in unexpected ways. A whiteboard or presentation slides might be helpful to organise, craft, and revise themes. We also provide a template for coproducing themes (supplemental material 3). As with codebook justification, team members will ideally produce individual drafts of the themes that they have identified in the data. They can then discuss these with the group and reach alignment or consensus on the final themes.

The team should ensure that all themes are salient, meaning that they are: supported by the data, relevant to the study objectives, and important. Similar to codes, themes are framed as complete thoughts or sentences, not categories. While codes and themes might appear to be similar to each other, the key distinction is that the themes represent a broader concept. Table 2 shows examples of codes and their corresponding themes from a previously published project that used practical thematic analysis. 36 Identifying three to four key themes that comprise a broader overarching theme is a useful approach. Themes can also have subthemes, if appropriate. 40 41 42 43 44

Example codes with themes in practical thematic analysis 36

Thematic analysis session

After each coder has independently produced draft themes, a carefully selected subset of the manuscript team meets for a thematic analysis session ( table 3 ). The purpose of this session is to discuss and reach alignment or consensus on the final themes. We recommend a session of three to five hours, either in-person or virtually.

Example agenda of thematic analysis session

The composition of the thematic analysis session team is important, as each person’s perspectives will shape the results. This group is usually a small subset of the broader research team, with three to seven individuals. We recommend that primary and senior authors work together to include people with diverse experiences related to the research topic. They should aim for a range of personalities and professional identities, particularly those of clinicians, trainees, patients, and care partners. At a minimum, all coders and primary and senior authors should participate in the thematic analysis session.

The session begins with each coder presenting their draft themes with supporting quotes from the data. 5 Through respectful and collaborative deliberation, the group will develop a shared set of final themes.

One team member facilitates the session. A firm, confident, and consistent facilitation style with good listening skills is critical. For practical reasons, this person is not usually one of the primary coders. Hierarchies in teams cannot be entirely flattened, but acknowledging them and appointing an external facilitator can reduce their impact. The facilitator can ensure that all voices are heard. For example, they might ask for perspectives from patient partners or more junior researchers, and follow up on comments from senior researchers to say, “We have heard your perspective and it is important; we want to make sure all perspectives in the room are equally considered.” Or, “I hear [senior person] is offering [x] idea, I’d like to hear other perspectives in the room.” The role of the facilitator is critical in the thematic analysis session. The facilitator might also privately discuss with more senior researchers, such as principal investigators and senior authors, the importance of being aware of their influence over others and respecting and eliciting the perspectives of more junior researchers, such as patients, care partners, and students.

To our knowledge, this discrete thematic analysis session is a novel contribution of practical thematic analysis. It helps efficiently incorporate diverse perspectives using the session agenda and theme coproduction template (supplemental material 3) and makes the process of constructing themes transparent to the entire research team.

Writing the report

We recommend beginning the results narrative with a summary of all relevant themes emerging from the analysis, followed by a subheading for each theme. Each subsection begins with a brief description of the theme and is illustrated with relevant quotes, which are contextualised and explained. The write-up should not simply be a list, but should contain meaningful analysis and insight from the researchers, including descriptions of how different stakeholders might have experienced a particular situation differently or unexpectedly.

In addition to weaving quotes into the results narrative, quotes can be presented in a table. This strategy is a particularly helpful when submitting to clinical journals with tight word count limitations. Quote tables might also be effective in illustrating areas of agreement and disagreement across stakeholder groups, with columns representing different groups and rows representing each theme or subtheme. Quotes should include an anonymous label for each participant and any relevant characteristics, such as role or gender. The aim is to produce rich descriptions. 5 We recommend against repeating quotations across multiple themes in the report, so as to avoid confusion. The template for coproducing themes (supplemental material 3) allows documentation of quotes supporting each theme, which might also be useful during report writing.

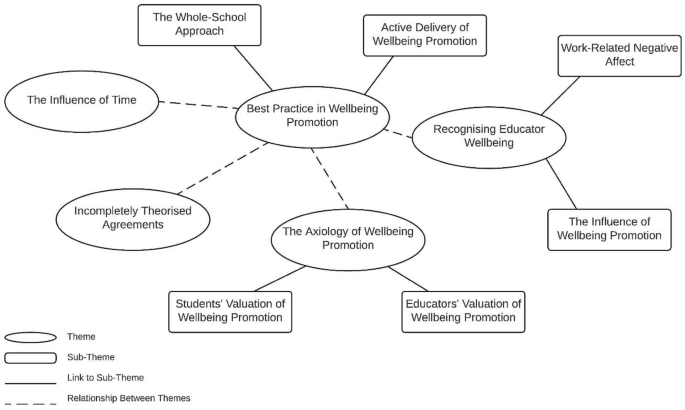

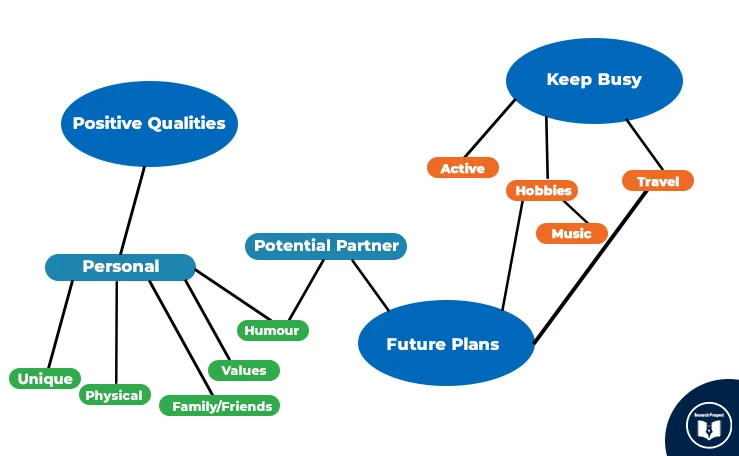

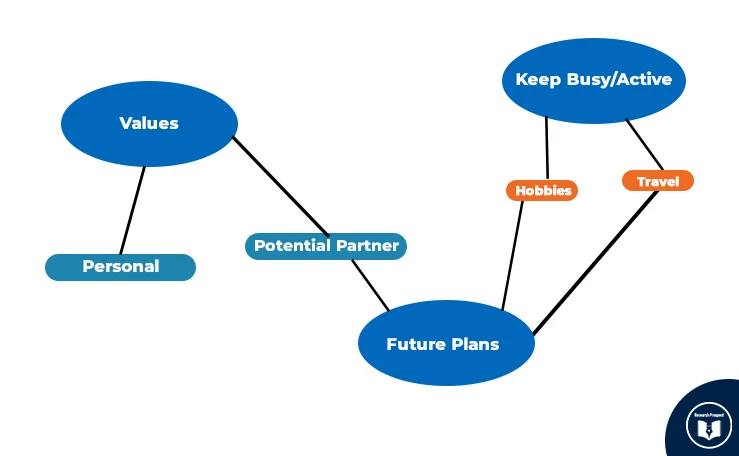

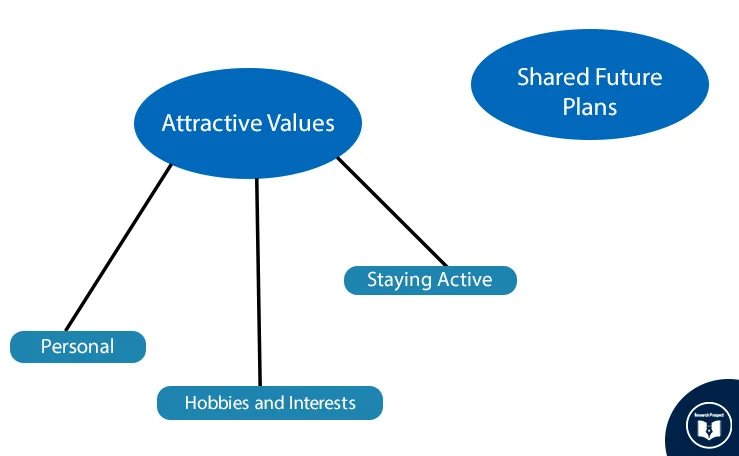

Visual illustrations such as a thematic map or figure of the findings can help communicate themes efficiently. 4 36 42 44 If a figure is not possible, a simple list can suffice. 36 Both must clearly present the main themes with subthemes. Thematic figures can facilitate confirmation that the researchers’ interpretations reflect the study populations’ perspectives (sometimes known as member checking), because authors can invite discussions about the figure and descriptions of findings and supporting quotes. 46 This process can enhance the validity of the results. 46

In supplemental material 4, we provide additional guidance on reporting thematic analysis consistent with COREQ. 18 Commonly used in health services research, COREQ outlines a standardised list of items to be included in qualitative research reports ( box 7 ).

Reporting in context

We note that use of COREQ or any other reporting guidelines does not in itself produce high quality work and should not be used as a substitute for general methodological rigor. Rather, researchers must consider rigor throughout the entire research process. As the issue of how to conceptualise and achieve rigorous qualitative research continues to be debated, 47 48 we encourage researchers to explicitly discuss how they have looked at methodological rigor in their reports. Specifically, we point researchers to Braun and Clarke’s 2021 tool for evaluating thematic analysis manuscripts for publication (“Twenty questions to guide assessment of TA [thematic analysis] research quality”). 16

Avoiding common pitfalls

Awareness of common mistakes can help researchers avoid improper use of qualitative methods. Improper use can, for example, prevent researchers from developing meaningful themes and can risk drawing inappropriate conclusions from the data. Braun and Clarke also warn of poor quality in qualitative research, noting that “coherence and integrity of published research does not always hold.” 16

Weak themes

An important distinction between high and low quality themes is that high quality themes are descriptive and complete thoughts. As such, they often contain subjects and verbs, and can be expressed as full sentences ( table 2 ). Themes that are simply descriptive categories or topics could fail to impart meaningful knowledge beyond categorisation. 16 49 50

Researchers will often move from coding directly to writing up themes, without performing the work of theming or hosting a thematic analysis session. Skipping concerted theming often results in themes that look more like categories than unifying threads across the data.

Unfocused analysis

Because data collection for qualitative research is often semi-structured (eg, interviews, focus groups), not all data will be directly relevant to the research question at hand. To avoid unfocused analysis and a correspondingly unfocused manuscript, we recommend that all team members keep the research objective in front of them at every stage, from reading to coding to theming. During the thematic analysis session, we recommend that the research question be written on a whiteboard so that all team members can refer back to it, and so that the facilitator can ensure that conversations about themes occur in the context of this question. Consistently focusing on the research question can help to ensure that the final report directly answers it, as opposed to the many other interesting insights that might emerge during the qualitative research process. Such insights can be picked up in a secondary analysis if desired.

Inappropriate quantification

Presenting findings quantitatively (eg, “We found 18 instances of participants mentioning safety concerns about the vaccines”) is generally undesirable in practical thematic analysis reporting. 51 Descriptive terms are more appropriate (eg, “participants had substantial concerns about the vaccines,” or “several participants were concerned about this”). This descriptive presentation is critical because qualitative data might not be consistently elicited across participants, meaning that some individuals might share certain information while others do not, simply based on how conversations evolve. Additionally, qualitative research does not aim to draw inferences outside its specific sample. Emphasising numbers in thematic analysis can lead to readers incorrectly generalising the findings. Although peer reviewers unfamiliar with thematic analysis often request this type of quantification, practitioners of practical thematic analysis can confidently defend their decision to avoid it. If quantification is methodologically important, we recommend simultaneously conducting a survey or incorporating standardised interview techniques into the interview guide. 11

Neglecting group dynamics

Researchers should concertedly consider group dynamics in the research team. Particular attention should be paid to power relations and the personality of team members, which can include aspects such as who most often speaks, who defines concepts, and who resolves disagreements that might arise within the group. 52

The perspectives of patient and care partners are particularly important to cultivate. Ideally, patient partners are meaningfully embedded in studies from start to finish, not just for practical thematic analysis. 53 Meaningful engagement can build trust, which makes it easier for patient partners to ask questions, request clarification, and share their perspectives. Professional team members should actively encourage patient partners by emphasising that their expertise is critically important and valued. Noting when a patient partner might be best positioned to offer their perspective can be particularly powerful.

Insufficient time allocation

Researchers must allocate enough time to complete thematic analysis. Working with qualitative data takes time, especially because it is often not a linear process. As the strength of thematic analysis lies in its ability to make use of the rich details and complexities of the data, we recommend careful planning for the time required to read and code each document.

Estimating the necessary time can be challenging. For step 1 (reading), researchers can roughly calculate the time required based on the time needed to read and reflect on one piece of data. For step 2 (coding), the total amount of time needed can be extrapolated from the time needed to code one document during codebook development. We also recommend three to five hours for the thematic analysis session itself, although coders will need to independently develop their draft themes beforehand. Although the time required for practical thematic analysis is variable, teams should be able to estimate their own required effort with these guidelines.

Practical thematic analysis builds on the foundational work of Braun and Clarke. 4 16 We have reframed their six phase process into three condensed steps of reading, coding, and theming. While we have maintained important elements of Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, we believe that practical thematic analysis is conceptually simpler and easier to teach to less experienced researchers and non-researcher stakeholders. For teams with different levels of familiarity with qualitative methods, this approach presents a clear roadmap to the reading, coding, and theming of qualitative data. Our practical thematic analysis approach promotes efficient learning by doing—experiential learning. 12 29 Practical thematic analysis avoids the risk of relying on complex descriptions of methods and theory and places more emphasis on obtaining meaningful insights from those close to real world clinical environments. Although practical thematic analysis can be used to perform intensive theory based analyses, it lends itself more readily to accelerated, pragmatic approaches.

Strengths and limitations

Our approach is designed to smooth the qualitative analysis process and yield high quality themes. Yet, researchers should note that poorly performed analyses will still produce low quality results. Practical thematic analysis is a qualitative analytical approach; it does not look at study design, data collection, or other important elements of qualitative research. It also might not be the right choice for every qualitative research project. We recommend it for applied health services research questions, where diverse perspectives and simplicity might be valuable.

We also urge researchers to improve internal validity through triangulation methods, such as member checking (supplemental material 1). 46 Member checking could include soliciting input on high level themes, theme definitions, and quotations from participants. This approach might increase rigor.

Implications

We hope that by providing clear and simple instructions for practical thematic analysis, a broader range of researchers will be more inclined to use these methods. Increased transparency and familiarity with qualitative approaches can enhance researchers’ ability to both interpret qualitative studies and offer up new findings themselves. In addition, it can have usefulness in training and reporting. A major strength of this approach is to facilitate meaningful inclusion of patient and care partner perspectives, because their lived experiences can be particularly valuable in data interpretation and the resulting findings. 11 30 As clinicians are especially pressed for time, they might also appreciate a practical set of instructions that can be immediately used to leverage their insights and access to patients and clinical settings, and increase the impact of qualitative research through timely results. 8

Practical thematic analysis is a simplified approach to performing thematic analysis in health services research, a field where the experiences of patients, care partners, and clinicians are of inherent interest. We hope that it will be accessible to those individuals new to qualitative methods, including patients, care partners, clinicians, and other health services researchers. We intend to empower multidisciplinary research teams to explore unanswered questions and make new, important, and rigorous contributions to our understanding of important clinical and health systems research.

Acknowledgments

All members of the Coproduction Laboratory provided input that shaped this manuscript during laboratory meetings. We acknowledge advice from Elizabeth Carpenter-Song, an expert in qualitative methods.

Coproduction Laboratory group contributors: Stephanie C Acquilano ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1215-5531 ), Julie Doherty ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5279-6536 ), Rachel C Forcino ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9938-4830 ), Tina Foster ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6239-4031 ), Megan Holthoff, Christopher R Jacobs ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5324-8657 ), Lisa C Johnson ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7448-4931 ), Elaine T Kiriakopoulos, Kathryn Kirkland ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9851-926X ), Meredith A MacMartin ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6614-6091 ), Emily A Morgan, Eugene Nelson, Elizabeth O’Donnell, Brant Oliver ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7399-622X ), Danielle Schubbe ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9858-1805 ), Gabrielle Stevens ( http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9001-178X ), Rachael P Thomeer ( http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5974-3840 ).

Contributors: Practical thematic analysis, an approach designed for multidisciplinary health services teams new to qualitative research, was based on CHS’s experiences teaching thematic analysis to clinical teams and students. We have drawn heavily from qualitative methods literature. CHS is the guarantor of the article. CHS, AS, CvP, AMK, JRK, and JAP contributed to drafting the manuscript. AS, JG, CMM, JAP, and RWY provided feedback on their experiences using practical thematic analysis. CvP, LCL, SLB, AVC, GE, and JKL advised on qualitative methods in health services research, given extensive experience. All authors meaningfully edited the manuscript content, including AVC and RKS. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This manuscript did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Ziebland S ,

- ↵ A Hybrid Approach to Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research: Using a Practical Example. 2018. https://methods.sagepub.com/case/hybrid-approach-thematic-analysis-qualitative-research-a-practical-example .

- Maguire M ,

- Vindrola-Padros C ,

- Vindrola-Padros B

- ↵ Vindrola-Padros C. Rapid Ethnographies: A Practical Guide . Cambridge University Press 2021. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=n80HEAAAQBAJ

- Schroter S ,

- Merino JG ,

- Barbeau A ,

- ↵ Padgett DK. Qualitative and Mixed Methods in Public Health . SAGE Publications 2011. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=LcYgAQAAQBAJ

- Scharp KM ,

- Korstjens I

- Barnett-Page E ,

- ↵ Guest G, Namey EE, Mitchell ML. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research . SAGE 2013. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=-3rmWYKtloC

- Sainsbury P ,

- Emerson RM ,

- Saunders B ,

- Kingstone T ,

- Hennink MM ,

- Kaiser BN ,

- Hennink M ,

- O’Connor C ,

- ↵ Yen RW, Schubbe D, Walling L, et al. Patient engagement in the What Matters Most trial: experiences and future implications for research. Poster presented at International Shared Decision Making conference, Quebec City, Canada. July 2019.

- ↵ Got questions about Thematic Analysis? We have prepared some answers to common ones. https://www.thematicanalysis.net/faqs/ (accessed 9 Nov 2022).

- ↵ Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications. 2022. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/thematic-analysis/book248481 .

- Kalpokas N ,

- Radivojevic I

- Campbell KA ,

- Durepos P ,

- ↵ Understanding Thematic Analysis. https://www.thematicanalysis.net/understanding-ta/ .

- Saunders CH ,

- Stevens G ,

- CONFIDENT Study Long-Term Care Partners

- MacQueen K ,

- Vaismoradi M ,

- Turunen H ,

- Schott SL ,

- Berkowitz J ,

- Carpenter-Song EA ,

- Goldwag JL ,

- Durand MA ,

- Goldwag J ,

- Saunders C ,

- Mishra MK ,

- Rodriguez HP ,

- Shortell SM ,

- Verdinelli S ,

- Scagnoli NI

- Campbell C ,