- Search by keyword

- Search by citation

Page 1 of 8

Longitudinal studies of bipolar patients and their families: translating findings to advance individualized risk prediction, treatment and research

Bipolar disorder is a broad diagnostic construct associated with significant phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity challenging progress in clinical practice and discovery research. Prospective studies of well-c...

- View Full Text

Sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of current rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: a multicenter Chinese study

Rapid cycling bipolar disorder (RCBD), characterized by four or more episodes per year, is a complex subtype of bipolar disorder (BD) with poorly understood characteristics.

Type of cycle, temperament and childhood trauma are associated with lithium response in patients with bipolar disorders

Lithium stands as the gold standard in treating bipolar disorders (BD). Despite numerous clinical factors being associated with a favorable response to lithium, comprehensive studies examining the collective i...

How effective are mood stabilizers in treating bipolar patients comorbid with cPTSD? Results from an observational study

Multiple traumatic experiences, particularly in childhood, may predict and be a risk factor for the development of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (cPTSD). Unfortunately, individuals with bipolar disord...

Perceived loneliness and social support in bipolar disorder: relation to suicidal ideation and attempts

The suicide rate in bipolar disorder (BD) is among the highest across all psychiatric disorders. Identifying modifiable variables that relate to suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) in BD may inform preventi...

Effectiveness of ultra-long-term lithium treatment: relevant factors and case series

The phenomenon of preventing the recurrences of mood disorders by the long-term lithium administration was discovered sixty years ago. Such a property of lithium has been unequivocally confirmed in subsequent ...

Prevention of suicidal behavior with lithium treatment in patients with recurrent mood disorders

Suicidal behavior is more prevalent in bipolar disorders than in other psychiatric illnesses. In the last thirty years evidence has emerged to indicate that long-term treatment of bipolar disorder patients wit...

Correlations between multimodal neuroimaging and peripheral inflammation in different subtypes and mood states of bipolar disorder: a systematic review

Systemic inflammation-immune dysregulation and brain abnormalities are believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of bipolar disorder (BD). However, the connections between peripheral inflammation and the brai...

Lithium: how low can you go?

Why is lithium [not] the drug of choice for bipolar disorder a controversy between science and clinical practice.

During over half a century, science has shown that lithium is the most efficacious treatment for bipolar disorder but despite this, its prescription has consistently declined internationally during recent deca...

Biomarkers for neurodegeneration impact cognitive function: a longitudinal 1-year case–control study of patients with bipolar disorder and healthy control individuals

Abnormalities in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-amyloid-beta (Aβ)42, CSF-Aβ40, CSF-Aβ38, CSF-soluble amyloid precursor proteins α and β, CSF-total-tau, CSF-phosphorylated-tau, CSF-neurofilament light protein (NF-L)...

Cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder in people with bipolar disorder: a case series

Social anxiety disorder increases the likelihood of unfavourable outcomes in people with bipolar disorder. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the first-line treatment for social anxiety disorder. However, ...

Lithium prescription trends in psychiatric inpatient care 2014 to 2021: data from a Bavarian drug surveillance project

Lithium (Li) remains one of the most valuable treatment options for mood disorders. However, current knowledge about prescription practices in Germany is limited. The objective of this study is to estimate the...

Lifetime risk of severe kidney disease in lithium-treated patients: a retrospective study

Lithium is an essential psychopharmaceutical, yet side effects and concerns about severe renal function impairment limit its usage.

Factors associated with suicide attempts in the antecedent illness trajectory of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia

Factors associated with suicide attempts during the antecedent illness trajectory of bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia (SZ) are poorly understood.

Behavioral lateralization in bipolar disorders: a systematic review

Bipolar disorder (BD) is often seen as a bridge between schizophrenia and depression in terms of symptomatology and etiology. Interestingly, hemispheric asymmetries as well as behavioral lateralization are shi...

High lithium concentration at delivery is a potential risk factor for adverse outcomes in breastfed infants: a retrospective cohort study

Neonatal effects of late intrauterine and early postpartum exposure to lithium through mother’s own milk are scarcely studied. It is unclear whether described symptoms in breastfed neonates are caused by place...

Key questions on the long term renal effects of lithium: a review of pertinent data

For over half a century, it has been widely known that lithium is the most efficacious maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder. Despite thorough research on the long-term effects of lithium on renal functio...

Controversies regarding lithium-associated weight gain: case–control study of real-world drug safety data

The impact of long-term lithium treatment on weight gain has been a controversial topic with conflicting evidence. We aim to assess reporting of weight gain associated with lithium and other mood stabilizers c...

Differential diagnosis of unipolar versus bipolar depression by GSK3 levels in peripheral blood: a pilot experimental study

The differential diagnosis of patients presenting for the first time with a depressive episode into unipolar disorder versus bipolar disorder is crucial to establish the correct pharmacological therapy (antide...

Supra-second interval timing in bipolar disorder: examining the role of disorder sub-type, mood, and medication status

Widely reported by bipolar disorder (BD) patients, cognitive symptoms, including deficits in executive function, memory, attention, and timing are under-studied. Work suggests that individuals with BD show imp...

Association between childhood trauma, cognition, and psychosocial function in a large sample of partially or fully remitted patients with bipolar disorder and healthy participants

Childhood trauma (CT) are frequently reported by patients with bipolar disorder (BD), but it is unclear whether and how CT contribute to patients’ cognitive and psychosocial impairments. We aimed to examine th...

Countering the declining use of lithium therapy: a call to arms

For over half a century, it has been widely known that lithium is the most efficacious treatment for bipolar disorder. Yet, despite this, its prescription has consistently declined over this same period of tim...

Paediatric bipolar disorder: an age-old problem

Nrx-101 (d-cycloserine plus lurasidone) vs. lurasidone for the maintenance of initial stabilization after ketamine in patients with severe bipolar depression with acute suicidal ideation and behavior: a randomized prospective phase 2 trial.

We tested the hypothesis that, after initial improvement with intravenous ketamine in patients with bipolar disorder (BD) with severe depression and acute suicidal thinking or behavior, a fixed-dose combinatio...

The IBER study: a feasibility randomised controlled trial of imagery based emotion regulation for the treatment of anxiety in bipolar disorder

Intrusive mental imagery is associated with anxiety and mood instability within bipolar disorder and therefore represents a novel treatment target. Imagery Based Emotion Regulation (IBER) is a brief structured...

Mitochondrial genetic variants associated with bipolar disorder and Schizophrenia in a Japanese population

Bipolar disorder (BD) and schizophrenia (SZ) are complex psychotic disorders (PSY), with both environmental and genetic factors including possible maternal inheritance playing a role. Some studies have investi...

Differential characteristics of bipolar I and II disorders: a retrospective, cross-sectional evaluation of clinical features, illness course, and response to treatment

The distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II disorder and its treatment implications have been a matter of ongoing debate. The aim of this study was to examine differences between patients with bipolar I a...

Neonatal admission after lithium use in pregnant women with bipolar disorders: a retrospective cohort study

Lithium is the preferred treatment for pregnant women with bipolar disorders (BD), as it is most effective in preventing postpartum relapse. Although it has been prescribed during pregnancy for decades, the sa...

Rates and associations of relapse over 5 years of 2649 people with bipolar disorder: a retrospective UK cohort study

Evidence regarding the rate of relapse in people with bipolar disorder (BD), particularly from the UK, is lacking. This study aimed to evaluate the rate and associations of clinician-defined relapse over 5 yea...

Exploratory study of ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation and age of onset of bipolar disorder

Sunlight contains ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation that triggers the production of vitamin D by skin. Vitamin D has widespread effects on brain function in both developing and adult brains. However, many people l...

Characteristics of rapid cycling in 1261 bipolar disorder patients

Rapid-cycling (RC; ≥ 4 episodes/year) in bipolar disorder (BD) has been recognized since the 1970s and associated with inferior treatment response. However, associations of single years of RC with overall cycl...

Clinicians’ preferences and attitudes towards the use of lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders around the world: a survey from the ISBD Lithium task force

Lithium has long been considered the gold-standard pharmacological treatment for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders (BD) which is supported by a wide body of evidence. Prior research has shown a st...

Phenotype fingerprinting of bipolar disorder prodrome

Detecting prodromal symptoms of bipolar disorder (BD) has garnered significant attention in recent research, as early intervention could potentially improve therapeutic efficacy and improve patient outcomes. T...

Predictors of adherence to electronic self-monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder: a contactless study using Growth Mixture Models

Several studies have reported on the feasibility of electronic (e-)monitoring using computers or smartphones in patients with mental disorders, including bipolar disorder (BD). While studies on e-monitoring ha...

Racial differences in the major clinical symptom domains of bipolar disorder

Across clinical settings, black individuals are disproportionately less likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder compared to schizophrenia, a traditionally more severe and chronic disorder with lower expec...

Methylomic biomarkers of lithium response in bipolar disorder: a clinical utility study

Response to lithium (Li) is highly variable in bipolar disorders (BD). Despite decades of research, no clinical predictor(s) of response to Li prophylaxis have been consistently identified. Recently, we develo...

A compelling need to empirically validate bipolar depression

Structured physical exercise for bipolar depression: an open-label, proof-of concept study.

Physical exercise (PE) is a recommended lifestyle intervention for different mental disorders and has shown specific positive therapeutic effects in unipolar depressive disorder. Considering the similar sympto...

Experiences that matter in bipolar disorder: a qualitative study using the capability, comfort and calm framework

When assessing the value of an intervention in bipolar disorder, researchers and clinicians often focus on metrics that quantify improvements to core diagnostic symptoms (e.g., mania). Providers often overlook...

Emotion regulation in bipolar disorder type-I: multivariate analysis of fMRI data

Bipolar disorder type-I (BD-I) patients are known to show emotion regulation abnormalities. In a previous fMRI study using an explicit emotion regulation paradigm, we compared responses from 19 BD-I patients a...

Lithium levels and lifestyle in patients with bipolar disorder: a new tool for self-management

Patients should get actively involved in the management of their illness. The aim of this study was to assess the influence of lifestyle factors, including sleep, diet, and physical activity, on lithium levels...

Reduced parenting stress following a prevention program decreases internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder

Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (OBD) are at risk for developing mental disorders, and the literature suggests that parenting stress may represent an important risk factor linking parental psychopat...

Stigma in people living with bipolar disorder and their families: a systematic review

Stigma affects different life aspects in people living with bipolar disorder and their families. This study aimed to examining the experience of stigma and evaluating predictors, consequences and strategies to...

Lithium use in childhood and adolescence, peripartum, and old age: an umbrella review

Lithium is one of the most consistently effective treatment for mood disorders. However, patients may show a high level of heterogeneity in treatment response across the lifespan. In particular, the benefits o...

Risk of childhood trauma exposure and severity of bipolar disorder in Colombia

Bipolar disorder (BD) is higher in developing countries. Childhood trauma exposure is a common environmental risk factor in Colombia and might be associated with a more severe course of bipolar disorder in Low...

A systematic review on the effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy for improving mood symptoms in bipolar disorders

Evidence-based psychotherapies available to treat patients with bipolar disorders (BD) are limited. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) may target several common symptoms of BD. We conducted a systematic review...

Bipolar disorder and sexuality: a preliminary qualitative pilot study

Individuals with mental health disorders have a higher risk of sexual problems impacting intimate relations and quality of life. For individuals with bipolar disorder (BD) the mood shifts might to a particular...

Long-term lithium therapy and risk of chronic kidney disease, hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcemia: a cohort study

Lithium is well recognized as the first-line maintenance treatment for bipolar disorder (BD). However, besides therapeutic benefits attributed to lithium therapy, the associated side effects including endocrin...

The association of genetic variation in CACNA1C with resting-state functional connectivity in youth bipolar disorder

CACNA1C rs1006737 A allele, identified as a genetic risk variant for bipolar disorder (BD), is associated with anomalous functional connectivity in adults with and without BD. Studies have yet to investigate the ...

- Editorial Board

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

- ISSN: 2194-7511 (electronic)

Bipolar disorders

Affiliations.

- 1 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Pharmacology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, ON, Canada. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Institute for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation Strategic Research Centre, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Mental Health Drug and Alcohol Services, Barwon Health, Geelong, VIC, Australia; Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Centre for Youth Mental Health, Florey Institute for Neuroscience and Mental Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Department of Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

- 3 Department of Psychiatry, Adult Division, Kingston General Hospital, Kingston, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, Queen's University School of Medicine, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada; Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada.

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 5 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia; Mood Disorders Program, Hospital Universitario San Vicente Fundación, Medellín, Colombia.

- 6 Copenhagen Affective Disorders Research Centre, Psychiatric Center Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark; Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 7 Discipline of Psychiatry, Northern Clinical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Department of Academic Psychiatry, Northern Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, Australia.

- 8 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 9 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Dauten Family Center for Bipolar Treatment Innovation, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

- 10 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 11 Hospital Clinic, Institute of Neuroscience, University of Barcelona, IDIBAPS, CIBERSAM, Barcelona, Spain.

- 12 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Psychiatric Research Unit, Psychiatric Centre North Zealand, Hillerød, Denmark.

- 13 Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London and South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust, Bethlem Royal Hospital, London, UK.

- 14 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- PMID: 33278937

- DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31544-0

Bipolar disorders are a complex group of severe and chronic disorders that includes bipolar I disorder, defined by the presence of a syndromal, manic episode, and bipolar II disorder, defined by the presence of a syndromal, hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode. Bipolar disorders substantially reduce psychosocial functioning and are associated with a loss of approximately 10-20 potential years of life. The mortality gap between populations with bipolar disorders and the general population is principally a result of excess deaths from cardiovascular disease and suicide. Bipolar disorder has a high heritability (approximately 70%). Bipolar disorders share genetic risk alleles with other mental and medical disorders. Bipolar I has a closer genetic association with schizophrenia relative to bipolar II, which has a closer genetic association with major depressive disorder. Although the pathogenesis of bipolar disorders is unknown, implicated processes include disturbances in neuronal-glial plasticity, monoaminergic signalling, inflammatory homoeostasis, cellular metabolic pathways, and mitochondrial function. The high prevalence of childhood maltreatment in people with bipolar disorders and the association between childhood maltreatment and a more complex presentation of bipolar disorder (eg, one including suicidality) highlight the role of adverse environmental exposures on the presentation of bipolar disorders. Although mania defines bipolar I disorder, depressive episodes and symptoms dominate the longitudinal course of, and disproportionately account for morbidity and mortality in, bipolar disorders. Lithium is the gold standard mood-stabilising agent for the treatment of people with bipolar disorders, and has antimanic, antidepressant, and anti-suicide effects. Although antipsychotics are effective in treating mania, few antipsychotics have proven to be effective in bipolar depression. Divalproex and carbamazepine are effective in the treatment of acute mania and lamotrigine is effective at treating and preventing bipolar depression. Antidepressants are widely prescribed for bipolar disorders despite a paucity of compelling evidence for their short-term or long-term efficacy. Moreover, antidepressant prescription in bipolar disorder is associated, in many cases, with mood destabilisation, especially during maintenance treatment. Unfortunately, effective pharmacological treatments for bipolar disorders are not universally available, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. Targeting medical and psychiatric comorbidity, integrating adjunctive psychosocial treatments, and involving caregivers have been shown to improve health outcomes for people with bipolar disorders. The aim of this Seminar, which is intended mainly for primary care physicians, is to provide an overview of diagnostic, pathogenetic, and treatment considerations in bipolar disorders. Towards the foregoing aim, we review and synthesise evidence on the epidemiology, mechanisms, screening, and treatment of bipolar disorders.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Anticonvulsants / therapeutic use

- Antidepressive Agents / therapeutic use

- Antimanic Agents / therapeutic use

- Antipsychotic Agents / therapeutic use

- Bipolar Disorder / classification*

- Bipolar Disorder / drug therapy*

- Bipolar Disorder / genetics

- Bipolar Disorder / psychology

- Carbamazepine / therapeutic use

- Cardiovascular Diseases / complications

- Cardiovascular Diseases / mortality

- Child Abuse / psychology

- Comorbidity

- Depressive Disorder, Major / drug therapy*

- Depressive Disorder, Major / genetics

- Depressive Disorder, Major / psychology

- Environmental Exposure / adverse effects

- Lamotrigine / therapeutic use

- Lithium / therapeutic use

- Mania / drug therapy

- Mania / psychology

- Suicide / psychology

- Suicide Prevention*

- Valproic Acid / therapeutic use

- Young Adult

- Anticonvulsants

- Antidepressive Agents

- Antimanic Agents

- Antipsychotic Agents

- Carbamazepine

- Valproic Acid

- Lamotrigine

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Special Report: Bipolar Disorder II—Frequently Neglected, Misdiagnosed

- Trisha Suppes , M.D., Ph.D. ,

- Holly A. Swartz , M.D. ,

- Sara Schley

Search for more papers by this author

Unlike its cousin, bipolar I disorder, which has been extensively studied and depicted in popular literature and on screen, bipolar II disorder is poorly understood, underdiagnosed, and insufficiently treated. This has often resulted in an over 10-year delay in diagnosis.

Even experienced clinicians know surprisingly little about bipolar II disorder (BD II), despite its inclusion as a distinct entity in DSM since 1994. An abundance of studies supports conceptualization of BD II as a unique phenotype within the bipolar illness spectrum, although many fail to recognize it as distinct disorder apart from bipolar I disorder (BD I).

Alternatively, BD II is considered a “lesser form” of BD I, despite numerous studies showing comparable illness severity and risk of suicide in these two BD subtypes. Perhaps because of its under-recognition, treatment studies of BD II are limited, and too often results from studies of patients with BD I are simply applied to those with BD II with no direct evidence supporting this practice. BD II is an understudied and unmet treatment challenge in psychiatry.

In this review, we will provide a broad overview of BD II including differential diagnosis, course of illness, comorbidities, and suicide risk. We will summarize treatment studies specific to BD II, identifying gaps in the literature. This review will reveal similarities between BD I and II, including suicide risk and predominance of depression over the course of illness, but also differences between the phenotypes in treatment response, for example to antidepressants.

We highlight the perspective of an expert by experience who discusses her lived experiences of BD II in an accompanying interview ( Interview With an Expert by Lived Experience ).

Diagnosis History

Alternating states of mania and melancholia are among the earliest described human diseases, first noted by ancient Greek physicians, philosophers, and poets. Hippocrates (460-337 B.C.E.), who formulated the first known classification of mental disorders, systematically described bipolar mood states: melancholia, mania, and paranoia. More than two millennia later, Emil Kraepelin, recognized as one of the founders of modern psychiatry, described manic-depressive illness as a singular disease characterized by alternating cycles of mania or melancholia. However, Kraepelin was more focused on mood changes and cycling than the polarity of episodes per se. Thus, his concept included what we now term recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD) . Nevertheless, his and other formulations from this period provide background for our modern concepts of bipolar disorder, differentiating it from unipolar depression (MDD and related disorders).

The hiding in plain sight of patients with BD II was brought to awareness by David L. Dunner, M.D., in the 1960s. When examining a cohort of individuals with mood disorders in a study by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), he identified a subgroup of patients with recurrent episodes of depression who also had a history of at least one period of hypomania and a strong family history of bipolar disorder. This subgroup was found to have a different course of illness compared with those with recurrent depression and a history of mania (BD I). Thanks to this work, BD II was recognized as a distinct disorder, separate from BD I. It finally entered the DSM lexicon in 1994 in DSM-IV and was added to ICD-10 even more recently.

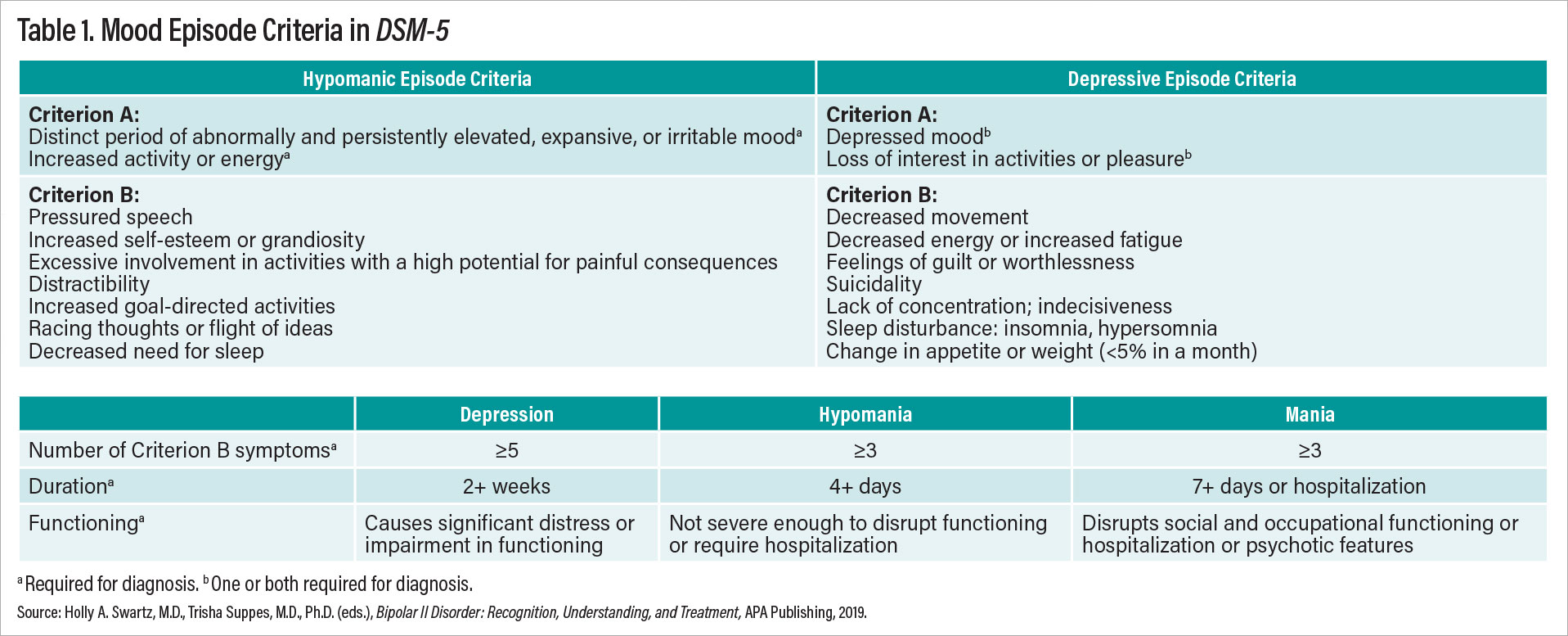

Conceptualization of bipolar disorders continues to evolve as the field learns more; for example, changes were made to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for BD such that Criteria A for both mania and hypomania now include increased energy as well as elevated or irritable mood (see Table 1). Thus, BD II is now recognized as a disorder of energy as well as mood.

DSM focuses on categorial diagnoses—that is, thresholds for absence or presence of disease. In parallel to this framework, many have argued for considering bipolar disorders along a continuous spectrum of illness. Thus, the term bipolar spectrum is used to describe both the spectrum of severity across BD symptoms as well as combinations of mood symptoms with manic/hypomanic and depressive components. Some refer to BD II as a part of the bipolar spectrum. These concepts reflect a growing awareness that dimensional descriptions of mood disorders may better map onto continuous biological markers of disease, compared with DSM ’s categorical approach, but the debate about diagnostic boundaries and disease etiology continues. Importantly, conceptualizations of BD as a spectrum condition versus discrete diagnostic categories (that is, BD I or BD II) are not mutually exclusive but rather speak to ongoing efforts to understand and best describe the phenomenology of BD.

Differential Diagnosis

The validity of BD II as a separate disorder has been reified through multiple empirical studies. The clinical diagnosis is reliably separable from BD I, as seen in APA clinical trials preparing for DSM-5 and in careful clinical interviews. In DSM-5 field trials to assess reliability of diagnoses, BD I was among the most recognizable, but BD II fell in the acceptable range and well above MDD as a reliable diagnostic entity. Family studies also support the diagnosis of BD II as an independent entity with distinct familial heritability, according to a 1976 study by Dunner et al. and a 1990 study by J. Raymond DePaulo, M.D., et al., and the authors of this report. Finally, genetic studies have found correlations suggesting the heterogeneity between BD I and BD II is “nonrandom,” supporting the concept of distinct conditions.

BD II diagnosis requires at least one lifetime hypomanic episode and one major depressive episode. Despite clarity of BD II diagnostic criteria, clinicians struggle to accurately identify it in practice. BD II is often either missed or incorrectly diagnosed, resulting in an over 10-year delay in diagnosis. Difficulties in accurate diagnosis arise from several sources. First, DSM-5 criteria for the depressive phase of BD II are identical to those required for a major depressive episode, which make BD II and MDD cross-sectionally indistinguishable. This is particularly notable as MDD diagnoses make up a substantial percent of the incorrect diagnoses for patients with BD II. Second, hypomania, which by definition is a less severe form of mania, may be difficult for patients to distinguish from a “normal” mood state when accompanied by extra energy and good mood. Third, mixed hypomanic mood states are very common in BD II, and in fact more common than euphoric hypomanic states. Mixed mood states are characterized by the presence of symptoms of opposite polarity during a depressive or hypomanic episode. In a mixed hypomania, patients might believe they are simply irritable and angry in the context of depression rather than recognizing the additional hypomanic symptoms warranting a diagnosis of mixed hypomanic state. Finally, patients rarely present for treatment in the midst of a hypomanic episode, a mood state that is either perceived as ego-syntonic or simply not identified as part of their illness during mixed hypomania.

The primary reason patients with BD II seek care is depression. Depression dominates the course of BD II, both in the early and late stages. However, retrospectively identifying episodes of hypomania during a depressive episode can be challenging. Further, many individuals see hypomania (either the euphoric or mixed variant) as part of “normal” mood rather than part of a bipolar spectrum, contributing to misreporting of mood episodes. Especially after unrelenting episodes of depression, it is understandable that many would perceive hypomania as a return to baseline. However, under-recognition of hypomania contributes to incorrect diagnoses. In sum, many individuals with BD II fail to recall, recognize, or report histories of hypomania, leading to an MDD (mis)diagnosis.

In psychiatry, all diagnoses are a one-way road. Individuals who have ever met criteria for a manic episode will continue to carry the diagnosis of BD I—even without further manic episodes. Similarly, patients who have a distant episode of hypomania and at least one prior major depressive episode would be considered to have BD II disorder, even in the absence of additional hypomanic episodes that meet symptom and duration criteria. Thus, accurate diagnosis of BD II relies on careful history taking. To improve diagnostic acumen, it is essential that clinicians systematically screen all patients with MDD for BD and ask careful questions about prior episodes of hypomania.

Course of Illness and Comorbidity

Kraepelin noted before the medication era that the course of illness for patients with BD generally progresses into more persistent and severe depression with aging. While he was primarily referring to manic-depressive illness, which we would call BD I today, the same principle applies to patients with BD II. In the NIMH collaborative study by Lewis Judd, M.D., et al., which included long-term follow-up of up to 20 years, patients with BD II experienced a course of illness characterized by more depressive episodes and fewer well intervals over time.

There is a longstanding debate in the literature whether patients with BD II suffer the same impairments and risks as those with BD I. BD II was previously—and incorrectly—labeled a “less severe” version of BD I. In fact, studies consistently show comparable disease burden in BD I and II. A recent Swedish study by Alina Karanti, M.D., et al. reported higher rates of depressive episodes, illness onset at a younger age, and significantly higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity (anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and ADHD) among patients with BD II compared with those with BD I. In this Swedish sample, (n>8,700) no differences were noted in substance abuse between BD I and BD II. Interestingly, individuals with BD II generally obtained more education and achieved a higher level of independence than those with BD I.

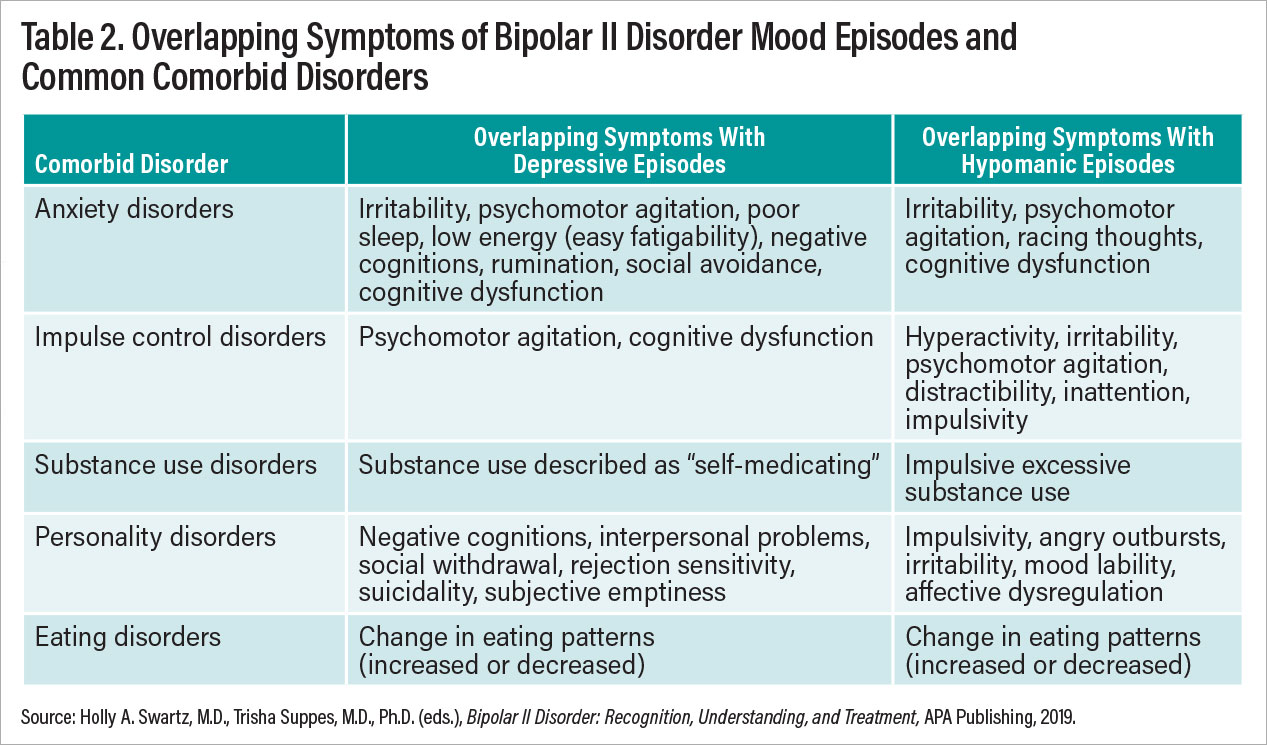

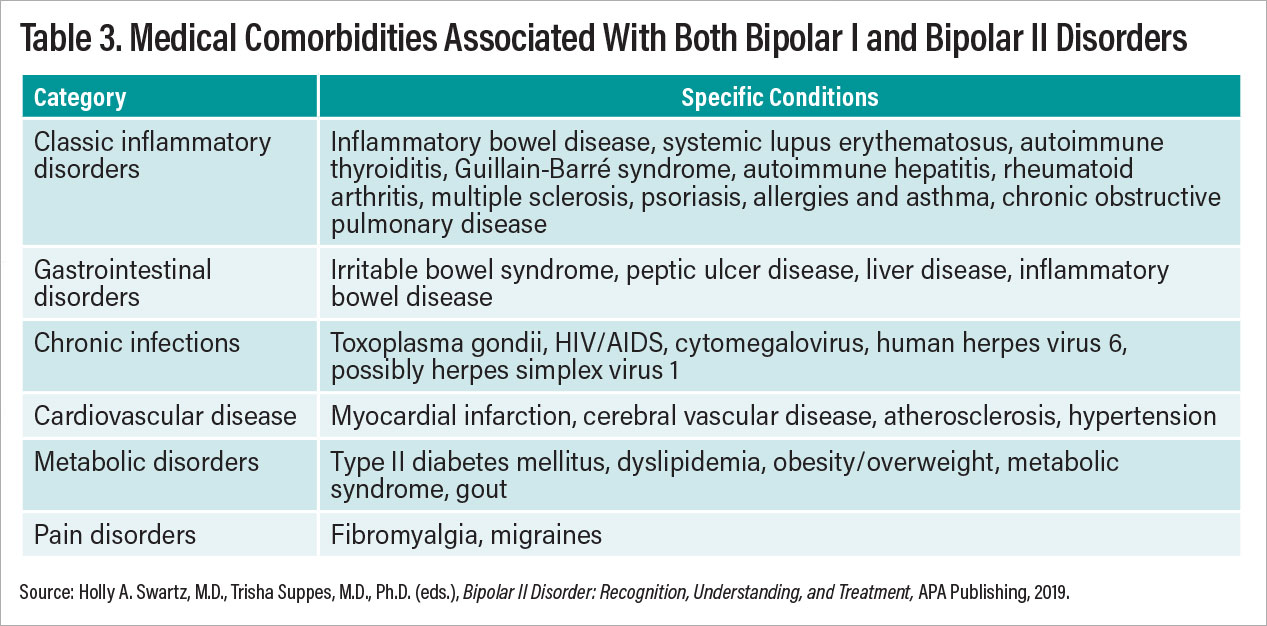

High rates of psychiatric comorbidity in patients with BD II further compound the challenge of differential diagnosis. There is considerable overlap between BD II and anxiety disorders. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder also frequently co-occurs. Approximately 20% of individuals with BD II also meet criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD), and up to 40% of those with BPD are incorrectly diagnosed as having BD I or II. Tables 2 and 3 show estimated co-occurring psychiatric illnesses for patients with BD II. The diagnosis of BD II requires a careful clinical interview of both past and current symptomatology.

Suicide is a significant risk for all patients with BD, and historically patients with BD I were viewed as having a higher risk than BD II due to the extremities of mania. However, data from a number of sources support that suicide risk is high across all patients with BD, and relatively little difference is found in risk for patients with BD I versus BD II. Older studies have suggested this risk may be higher for patients with BD II than BD I, and, indeed, the Swedish bipolar registry database study recently indicated that the rate of suicide attempts was significantly higher in patients with BD II though no data on completed suicides were provided. Overall, the reports from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide found that the risk for suicide was estimated at 164 of 100,000 per year in patients with BD versus 10 of 100,000 per year in the general population (see the reference by Ayal Schaffer, M.D., at the end of this report).

Treatment of BD II

Treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder often give only a passing nod to distinguishing appropriate treatments for BD I versus BD II. The combined guidelines by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) were unusual in making a point of distinguishing the evidence base for BD I versus BD II. They are reported in a 2018 paper by Lakshmi N. Yatham, M.D., et al. (see reference at end of article).

These guidelines have a separate section devoted to BD II, and they clearly state that one cannot directly apply studies on patients with BD I to management of patients with BD II. The conclusion of these guidelines is that there are too few controlled studies in patients with BD II to make detailed evidence-based recommendations or develop evidence-based treatment algorithms. Below is a brief overview of our current knowledge of treatments for patients with BD II with medication and/or psychotherapy.

Antidepressants

It is worth highlighting that, while monotherapy antidepressants would be viewed as an inappropriate practice for patients with BD I depression, studies suggest that the risks and benefits may be different for those with BD I and BD II. In at least one study, risk of switching to hypomania was no greater with lithium than with sertraline monotherapy. Other studies have shown antidepressant monotherapy to be an efficacious monotherapy for BD II. Meta-analyses on risk of antidepressant-induced switches are inconclusive, though the risk of treatment-emergent (hypo)mania due to medication appears to be less in patients with BD II than in patients with BD I depression receiving monotherapy antidepressants. Absent conclusive data on antidepressant switch rates, without a past record of good response to antidepressant monotherapy, current treatment guidelines suggest starting with lithium or a mood stabilizer before adding or switching to antidepressant monotherapy. Additionally, it is important to note that antidepressants in some patients may worsen the overall course of illness and may not be efficacious in some patients with BD II. Any patient who experiences hypomania or mania (which must be distinguished from transient activation symptoms) while on antidepressant medication should be presumed to be on the bipolar spectrum.

Antipsychotics

Most atypical antipsychotics have not been studied for the treatment of both BD I and BD II depression, with two notable exceptions. Quetiapine registration trials included individuals with BD II, with post-hoc analyses demonstrating efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy for BD II depression. Lumateperone is the first antipsychotic formally studied for depression response in patients with BD II since quetiapine trials in the early 2000s. Lumateperone, in randomized, controlled trials, performed as well or better for BD II than BD I, according to a 2021 study by Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D., et al. Cariprazine and lurasidone, while both FDA approved to treat bipolar depression, were never formally studied in patients with BD II. There have been case series supporting their use in BD II depression, but no randomized, controlled trials have been carried out. FDA approval to treat patients with BD II depression with lumateperone came in 2021, 15 years after quetiapine was approved. This glacial rate of accruing new FDA-approved compounds for BD II speaks to the need for more studies in this population.

Lithium and Anticonvulsants

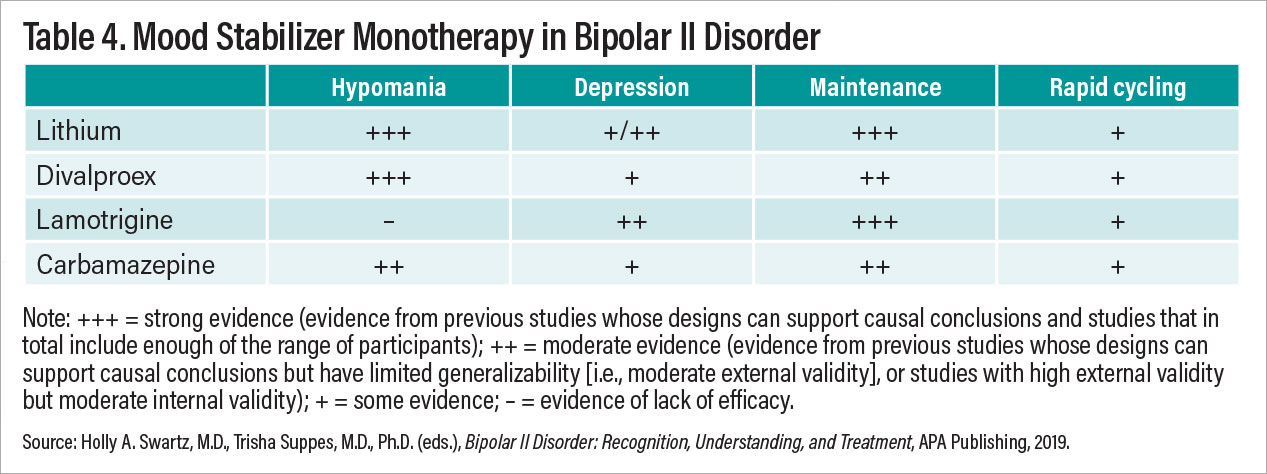

While we might expect lithium to be the frontrunner treatment for managing BD II, study results are varied. Certainly, for hypomania and maintenance treatment of patients with BD II, lithium is a top choice. Lithium has a disappointingly poor track record for treating BD II depression with little indication that response rates are superior to those of antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics. Lamotrigine has good evidence for preventing new depression episodes in the context of BD (both BD II and I). The evidence, however, is less robust for treating acute depression in patients with BD II. In clinical practice, many clinicians prescribe lamotrigine, especially as an adjunctive treatment, for BD II depression, but our ability to make firm recommendations with confidence about lamotrigine is limited.

Other Therapies

Rapid-acting therapies are on the rise across all treatments for depression. There has been a recent surge of clinical work and research examining transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), ketamine, and psychedelics and related compounds. More work is needed specifically focused on BD II depression before firm conclusions may be drawn.

There is limited evidence supporting the use of TMS for BD II depression. This evidence base is developing, and more information is forthcoming on the utility of TMS for BD II depression.

Ketamine and Psychedelic Studies

Racemic ketamine has been in use for many years as an anesthetic and more recently was approved by the FDA as intranasal esketamine (the s-enantiomer of racemic ketamine) as a treatment for MDD. Three small studies of racemic ketamine suggest that it is effective for BD II depression. A 2022 observational study by Farhan Fancy et al. assessing patients with BD I versus BD II treated with racemic ketamine included more than 60 patients (n=35 BD II). In this largest open observational study to date involving ketamine and BD, patients with BD II demonstrated a more robust response than those with BD I. More studies are in development exploring this new use of an old drug; to date, there is no information on the role of esketamine for bipolar depression, let alone BD II.

Recently, it’s been difficult to pick up a journal or look at other media without seeing something about psychedelics and related compounds. There is a surge of interest in psychedelics for MDD, although evidence about their effectiveness is still early and with rare exceptions involves small samples. There is one report on treatment of depression with psilocybin in patients with BD II. In this pilot study, 15 patients with BD II were given a one-time dose of psilocybin (25 mg) and provided preparatory, dosing, and integration therapy consistent with psilocybin studies in MDD. In this small open study by Scott Aaronson, M.D., et al., the rate of response at 3 and 12 weeks was more robust than has been observed in MDD studies. An ongoing study is assessing the durability of patients’ response to psilocybin administered one time for patients with BD II depression. While no notable adverse events or increased mood lability were noted in this small sample to date, further study is needed to assess benefits and harms.

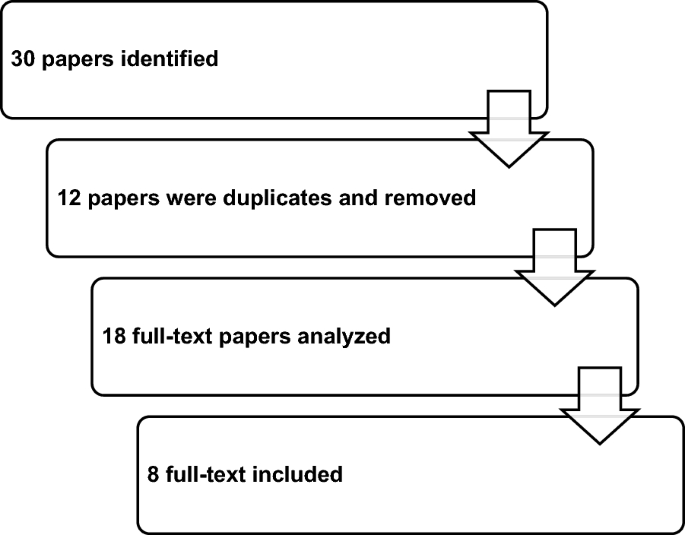

Psychotherapy

Most information about psychotherapy for BD II is derived from trials of interventions for BD in general that also included a subset of individuals with BD II. A recent systematic review of psychotherapies for BD II identified over 1,000 individuals with BD II who participated in randomized, controlled trials testing psychosocial interventions to treat depression or prevent recurrence of mood symptoms. However, relatively few of these trials—only eight of 27—examined outcomes in those with BD II separately. From this review, we concluded that there is preliminary evidence supporting the efficacy of several evidence-based psychotherapies for BD II: cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, family focused therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), and functional remediation. None of these psychotherapies have undergone rigorous testing in randomized, controlled trials focused specifically on BD II depression, with the exception of IPSRT, pointing to the need for additional research in this area. To our knowledge, no meta-analysis of psychotherapy for BD II has been published.

IPSRT, the only psychosocial intervention to be tested in a randomized, controlled trial consisting of participants with BD II only (rather than a mixed patient population of BD I and II), focuses on helping individuals develop more regular routines to stabilize underlying disturbances in circadian rhythms. Because abnormalities in circadian biology have been implicated in the genesis of bipolar disorders, including BD II, a chronobiologic behavioral approach may be especially helpful to mitigate BD II symptoms.

Conclusions

BD II is a relatively common disorder affecting approximately 0.4% of the population. Its prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are comparable to that of BD I. Evidence supports conceptualizing BD II as a distinct phenotype, separable from both BD I and MDD. Compared with BD I and MDD, far less is known about BD II and how to treat it. Further, despite being reliably diagnosed in DSM-5 field trials, BD II is frequently misdiagnosed in practice, resulting in a decade-long lag between onset of symptoms and appropriate diagnosis. A neglected condition, BD II causes unnecessary suffering in those who are misdiagnosed or for whom appropriate treatments are unclear. More research is urgently needed to improve identification and treatments for BD II. ■

David L. Dunner, M.D., et al. “ Heritable Factors in the Severity of Affective Illness ,” Biological Psychiatry , February 1976.

J. Raymond DePaulo, M.D., et al. “ Bipolar II Disorder in Six Sisters ,” Journal of Affective Disorders , August 1990.

Lewis Judd, M.D., et al. “ Long-Term Symptomatic Status of Bipolar I vs. Bipolar II Disorders ,” International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, June 2003.

Alina Karanti, Ph.D., et al. “ Characteristics of Bipolar I and II Disorder: A Study of 8766 Individuals ,” Bipolar Disorders , June 2020.

Ayal Schaffer, M.D., et al. “ A Review of Factors Associated With Greater Likelihood of Suicide Attempts and Suicide Deaths in Bipolar Disorder: Part II of a Report of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide in Bipolar Disorder ,” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , November 2015.

Lakshmi N. Yatham, M.D., et al. “ Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Bipolar Disorder ,” Bipolar Disorders , March 2018.

Joseph R. Calabrese, M.D., et al. “ Efficacy and Safety of Lumateperone for Major Depressive Episodes Associated With Bipolar I or Bipolar II Disorder: A Phase 3 Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial ,” American Journal of Psychiatry , December 2021.

Farhan Fancy, et al. “ Real-World Effectiveness of Repeated Ketamine Infusions for Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression ,” Bipolar Disorders , December 14, 2022.

Scott Aaronson, M.D., et al. “ COMP360 Psilocybin Therapy Shows Potential in Open-Label Study in Type II Bipolar Disorder ,” Global Newswire, December 8, 2022.

Trisha Suppes, M.D., Ph.D., is a professor of psychiatry, staff psychiatrist at the VA Palo Alto, and director of the Exploratory Therapeutics Laboratory at Stanford University.

Holly A. Swartz, M.D., is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and director of the Center for Advanced Psychotherapy at Western Psychiatric Hospital.

They are co-editors of Bipolar II Disorder: Recognition, Understanding, and Treatment from APA Publishing. APA members may purchase the book at a discount.

Sara Schley is the author of Brainstorm: From Broken to Blessed on the Bipolar Spectrum (Seed Systems, 2022). She is the founder of a consulting business and has worked with hundreds of renowned companies worldwide.

Innovations in the treatment of bipolar disorder Stanford University School of Medicine

Servings our Nation's Veterans Stanford University School of Medicine in Collaboration with VA Palo Alto Healthcare System

The bipolar and depression research program.

The Bipolar and Depression Research Program is a clinical research program focused on treatment of individuals with bipolar and major depressive disorders directed by Drs. Trisha Suppes and Michael Ostacher . It is located on the campus of the VA Palo Alto Health Care System and affiliated with the VA and the Stanford School of Medicine. All studies are open to the general public as well as veterans and active duty military personnel. Our research focuses on Bipolar Disorder, including Bipolar Disorder that occurs with Generalized Anxiety Disorder or Life Time Panic Disorder, Major Depressive Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). We have several current studies underway. A new division of our research efforts is addressing moods disorders using exploratory therapeutics. Compounds under consideration for depressed individuals: Psilocybin and Pramipexole.

Learn more about our current studies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 08 February 2021

Bipolar I disorder: a qualitative study of the viewpoints of the family members of patients on the nature of the disorder and pharmacological treatment non-adherence

- Nasim Mousavi 1 ,

- Marzieh Norozpour ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8894-9178 1 ,

- Zahra Taherifar 2 ,

- Morteza Naserbakht 3 &

- Amir Shabani 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 21 , Article number: 83 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Bipolar disorder is a common psychiatric disorder with a massive psychological and social burden. Research indicates that treatment adherence is not good in these patients. The families’ knowledge about the disorder is fundamental for managing their patients’ disorder. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the knowledge of the family members of a sample of Iranian patients with bipolar I disorder (BD-I) and to explore the potential reasons for treatment non-adherence.

This study was conducted by qualitative content analysis. In-depth interviews were held and open-coding inductive analysis was performed. A thematic content analysis was used for the qualitative data analysis.

The viewpoints of the family members of the patients were categorized in five themes, including knowledge about the disorder, information about the medications, information about the treatment and the respective role of the family, reasons for pharmacological treatment non-adherence, and strategies applied by families to enhance treatment adherence in the patients. The research findings showed that the family members did not have enough information about the nature of BD-I, which they attributed to their lack of training on the disorder. The families did not know what caused the recurrence of the disorder and did not have sufficient knowledge about its prescribed medications and treatments. Also, most families did not know about the etiology of the disorder.

The lack of knowledge among the family members of patients with BD-I can have a significant impact on relapse and treatment non-adherence. These issues need to be further emphasized in the training of patients’ families. The present findings can be used to re-design the guidelines and protocols in a way to improve treatment adherence and avoid the relapse of BD-I symptoms.

Peer Review reports

Bipolar I disorder (BD-I) is a chronic and recurrent psychiatric disorder in which a person has a manic episode for 1 week, which may present before or after hypomanic or major depressive episodes [ 1 ].

BD-I is accompanied by chronic stress, disability, increased risk of sudden mood swings, higher rates of comorbid disorders and moral, financial, and legal problems. The disorder is ranked the sixth debilitating disease according to the World Health Organization (WHO). BD-I is considered the most expensive mental disorder in terms of the health and behavioral care required by the patients and the burden on governmental institutions and insurance companies [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. According to a report by the Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the average annual income of an Iranian household in 2012 was 209,050,000 Rials. The direct annual cost of one BD-I patient consists of 10% of this average family income [ 5 ].

BD-I affects the patient’s life and has long-term consequences that are visible in the patient’s social performance and quality of life [ 6 , 7 ]. Severe impairment in job performance is observed in about 30% of the patients with BD-I. In such cases, functional improvement falls substantially behind symptom improvement [ 1 ].

Pharmacological treatment is the first-line treatment for BD-I. Evidence shows that about 40% of patients with BD-I do not have good medication adherence, which translates into a higher probability of symptom relapse, hospitalization, and increased suicide risk [ 8 ]. In a study in Tehran, Iran, poor treatment adherence was noticed in about 30% of BD-I patients [ 9 ]. Another study from Iran [ 10 ] also reported the prevalence of poor compliance in BD-I patients after the first episode of mania as 38.1% during a 17-month follow-up period. Therefore, it is of great importance to better understand and investigate the underlying reasons for treatment non-adherence in BD-I patients.

Given the changes implemented in health care systems over the last two decades and the resultant focus on community-based services, the role of families in caring for BD-I patients has become more prominent [ 6 ]. The insufficient knowledge of families about the disorder, its symptoms, and medications has made the management of BD-I more difficult and eventually imposes additional costs on them [ 6 ]. The higher is the cost imposed on the family, the more likely is it for the family members to show adverse reactions to the BD-I patients, which itself leads to a higher chance of disorder relapse [ 3 ].

In Iran, the general public is acquainted with various types of psychiatric illnesses through mass media and public educational websites such as the website of the Iranian Psychiatric Association ( https://iranmentalhealth.com ) and other Persian public written sources. Patients with BD-I and their families become familiar with the treatment process after consulting a general practitioner, a psychiatrist, or a psychologist, and, if necessary, the patients are admitted to the hospital through a psychiatrist. In addition to medical treatment, they receive the necessary training and information about their treatment process in the hospital. Furthermore, an association called ABR (Association of Mental Health Promotion), with an active website ( http://abrcharity.ir ), independently monitors patients, including those with bipolar disorder, after discharge.

Many studies have examined the views and roles of patients with BD-I and their caregivers and also the importance of family awareness and its impact on medication adherence. Tacchi & Scott [ 11 ] and Veligan et al. [ 12 ] suggest that the family members’ beliefs about the nature of BD-I and the information they have about the disorder affect the patient’s medication adherence. The review of literature showed no precise studies conducted to explore the knowledge, information, and opinions of family members of BD-I patients about the disorder and the causes of their medication non-adherence.

In a previous study in Iran [ 13 ], the authors held qualitative interviews with the family members of patients with BD-I and reported that treatment non-adherence is a major problem in these patients. They also reported that the patients and their families did not have sufficient knowledge about the nature of this disorder. Considering these findings about the insufficient knowledge of the family members of BD-I patients and the high rate of treatment non-adherence, it is necessary to conduct more studies to investigate the possible causes of treatment non-adherence and families’ knowledge and beliefs about this disorder in Iran. This study was thus carried out to explore the viewpoints of the family members of BD-I patients about the nature of this disorder and the potential causes of treatment non-adherence. The results can be used for revising the psychoeducation guidelines for BD-I patients, as clinical guidelines mandate the inclusion of psychoeducation in the treatment plan adopted for these patients. The results can also be used to design a protocol to address the disorder relapse, which can have substantial consequences in terms of reducing healthcare costs.

The findings of this study are reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [ 14 ].

Study samples’ characteristics

The participants were the family members of patients diagnosed with BD-I. The patients had been admitted to Iran Psychiatry Hospital in Tehran, Iran, and were receiving pharmacological treatments.

This study used purposive sampling to select the participants. From November 2017 to April 2018, 12 patients were interviewed by two psychiatrists based on the DSM-5 criteria [ 1 ] and received the diagnosis of BD-I. Then these diagnoses were confirmed by A.SH. and their families were invited to participate in the study.

None of the family members refused to participate in the study and they all completed the entire course of the study. The mean age of the participants was 50.83 years. There were three male (25%) and nine female (75%) participants (Table 1 ). Table 2 shows further details on patients’ characteristics.

Data collection

After diagnosing patients with BD-I, and obtaining the written consent of the family members of patients to participate in this study, data were collected by in-depth interviews from family members of patients, conducted at the hospital’s conference hall. No one else was present at the time of the interviews except for the interviewer and the participant. Each interview lasted approximately 20 min and was digitally recorded for subsequent analyses. Two female PhD candidates (N. M. and M. N.) in clinical psychology at the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran, who had already received training on the implementation of qualitative studies, held the interviews. They did not know any of the participants. The interviewers introduced themselves to the participants before the beginning of each interview. The interview questions were provided by the authors. The interviews were held only once and were not repeated. Data saturation was reached with 12 participants, and no further participants were interviewed after reaching this number. Data saturation occurs when no new information is obtained by conducting further interviews [ 15 ].

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used for the qualitative data analysis [ 16 , 17 ]. To this end, the six steps proposed by Clark and Brown [ 17 ] were used.

The raw data derived from the interviews were used for the analysis. The content of the interviews were transcribed verbatim immediately after each interview. Field notes were made during the interviews and were reviewed in this stage. Three authors (M. N., N. M., and Z. T.) read the interviews several times for immersing in the data and getting familiar with it. Line-by-line coding was then applied to generate the initial codes. These steps were performed manually by the three authors without using any computer programs. One author encoded each interview and the interview was then read by another author and encoded again. The individually-extracted codes were then integrated and modified, if necessary.

In the next step, by linking the codes together, their common patterns and concepts were extracted and potential themes and subthemes were identified, keeping the research questions in mind. The data related to the themes were then collected and examined to verify the accuracy of the themes and subthemes, which resulted in five final themes.

Several statements were selected from the interviews as examples and are reported in the results section. To preserve participants’ anonymity, their names and ages are not mentioned in the results; instead, they are represented by random numbers.

Taking into account comprehensiveness, homogeneity, and overlap, the components of the family members’ viewpoints on the nature of the disorder and the reasons for pharmacological treatment non-adherence were categorized into five themes, including knowledge about the disorder, information about the medications, information about the treatment and the respective role of the family, reasons for pharmacological treatment non-adherence, and strategies applied by families to enhance treatment adherence in the patients.

Each of the themes contained several subthemes, which were themselves made up of some open codes. These subthemes contained recurrent codes and concepts that shared a common meaning.

Table 3 presents the themes, subthemes and examples of some of the codes.

Theme one: knowledge about the disorder

Most interviewees did not have sufficient or accurate knowledge about the nature of BD-I, the signs and symptoms of depression and mania cycles, and the outcome of the disorder. They mentioned the lack of training or inadequate training (especially by healthcare providers) as the main cause of insufficient knowledge about BD-I. Additionally, most families did not have a good understanding of the etiology of BD-I.

Some of them considered BD-I as a genetic abnormality, while others considered factors such as adolescent maltreatment, parents’ unusual conditions during sexual intercourse, and the lack of proper training before parenthood as potential causes of BD-I.

Participant No. 5 (a patient’s wife): “I was told that he has a nervous problem.” Participant No. 3 (a patient‘s mother): "I have a theory about having babies. I think that not everyone should have children. The husband and wife should be screened and monitored for two years to see if they understand the matter clearly. Do you see these anomalies now? ... These shameful movies they watch … The person is not feeling well when raising their kid … From an Islamic point of view, from a human’s point of view, both the husband and wife need to be monitored. Their food and other things should also be monitored to see if they can have a healthy baby.”

Participant No. 7 (a patient’s mother): "Because this boy is always impressed by me, sometimes I tell myself, maybe I didn’t fully understand him during his puberty. Sometimes I blame myself, as he has said this many times. I always blame myself … . Sometimes he says, ‘You did this to me, that’s why I’m sick now and take drugs’. For example, when hitting puberty, in the first or second year of high school, he used to get up late and so he got to school very late. Then the school’s principal complained to me, ‘Why is he late again?’ And he says, ‘Why did you wake me up early in the morning? You did this to me.” Participant No. 10 (a patient’s mother), referring to her son's divorce: "That's why he's so broken.” Participant No. 11 (a patient’s sister): "Bipolar disorder has a genetic background. I think there would be no one out there who suffered from the disorder unless they got the genes. It is a genetic disorder, but it emerges when a patient experiences a series of shocking events. Well, some have higher potentials, such as those who get very angry. I mean, the anger itself is not part of the disorder, but in angry people, shocking events affect the patient more rapidly.”

Theme two: information about the medications

Many family members had a misconception about the treatment of the disorder and the effects of psychotropic medications on the patients. In other words, they were unable to accurately identify the therapeutic effects of the administered medications and the time it took for the patients to show signs of improvement. Also, some participants were unaware of the side-effects of the prescribed medications. Some mentioned side-effects like memory loss and drug addiction; however, almost all the participants believed that pharmacological treatment is necessary for the patients despite the side-effects.

Participant No. 1 (a patient’s mother): "The problem of her running away from home with her boyfriend was a big burden for us, but as the prescribed meds began to show their effectiveness, this problem was gradually solved and we finally managed to put up with her aggressiveness and other problems. That is, we were saying to ourselves, ‘This is a period of angriness; we had better not said this, not done that’... We thought the medication was working. But now they’ve told me, ‘No, your patient has not recovered at all, has not been cured.”

Participant No. 1 (a patient's mother): "Her first psychiatrist, who has been visiting her for eight years, was frequently asking if she studies, watches TV or goes to work at all. ‘Whenever she goes back to these routines, then she has recovered,’ the therapist would say. Recently, she’s always been saying, ‘I would love to go to work’ and so on. Once, her employer told her to do some cleaning, and she had responded, ‘I’m not your servant.’ She suddenly broke it off and said, ‘I won’t go to work anymore.’ She didn’t sleep at all, saying, ‘I work so much, but I don’t feel exhausted at all.’ We were also excited and thought ‘Yeah, so this doctor's meds have been good; she’s getting back to normal, she’s working,’ She was frequently organizing her closet, like an obsession.”

Participant No. 3 (a patient’s mother): “I can’t remember the side-effects but I’ve heard about them in classes. My daughter is taking lithium now but she gets these chills. Her stomach is not well. Its side-effects are such that they affect her memory. However, when we compare the pros and cons, we have to take it. "

Theme three: information about the treatment

The regular intake of medications, stress control, work, exercise, regular visits to a psychiatrist or psychologist, and the need to provide insight into the patient’s illness through education were noted by the families in this part. Some participants believed that psychotherapy sessions cannot help treat this disorder while some had completely false or superstitious beliefs about treatment of the disorder.

Participant No. 4 (a patient's son): "Our patient doesn’t accept justifications. When you bring them to classes and convince them that ‘You are sick, and you have to take this medication because of this and that, and we have evidence that you have this disorder,’ and then we show it to them, prove it like in the movies, say that this disorder is serious because of so and so reasons, I think, it would be much easier.”

Participant No. 1 (a patient’s mother): "They sent us to get counseling. Of course, my daughter did not cooperate and didn’t come with. So, I got an appointment under my name to get information and find out how to deal with this disorder. Then the psychologist said, 'No, your daughter is diagnosed with bipolar disorder; this is an acute illness. Counseling does not work for her. She should take medications –a lot of them. And since the doc said those words, we withdrew from counseling altogether.”

Participant No. 5 (a patient’s wife): "My mother-in-law says, ‘If God gives him a baby, he’ll be fine.’ Because his ex-wife also failed to bear a child for him.”

Theme four: information about the role of the family in the treatment

Most families defined their role as helping the patient recover and adhere to their treatment, reminding them to take the medications, encouraging them to go to the doctor, not leaving them alone, and doing whatever they wanted to do so that things went as the patient wished. The patients also appeared to feel guilty when their families tried to comfort them, and this pattern was observed in several of the participants in this study.

Participant No. 6 (a patient’s husband): "We should put up with her, love her, not argue about what she says, listen to her, get her to do exercise to keep busy. I'm here now and I brought her with me too instead of leaving her alone to think about stuff.”

Participant No. 2 (a patient’s mother): "You should be good to them, listen to them, make home a peaceful environment, and not argue.”

Participant No. 8 (a patient’s wife): “I don't know. If he just thinks that everything is okay, all will be okay; but such feelings don’t last forever.”

Participant No. 2 (a patient’s mother): "I tell him to take his meds on time … Say, ‘Let's go to the park to take a look around ... Don't stay at home too much. God is merciful; it won’t be that bad’ … I talk to him, I comfort him sometimes, tell him that I’m ill too because I feel your pain.’ I really do. I’ve been crying alone at home many times. God, what will happen at the end?"(She cries).

Theme five: reasons for pharmacological treatment non-adherence

As for this theme, the participants noted issues that were mostly about the comments made by other people, including relatives or care-providers, such as doctors or specialists in other disciplines. An interesting observation was made by a participant who mentioned a celebrity talking on TV about the inefficiency of medications; following these comments, the patient had stopped taking his medications. Another issue was that the families’ constant changing of the patient’s physician contributed to their medication non-adherence. Another reason noted for non-adherence was that the patients did not suffer from mania symptoms and found that it was not so crucial for them to take the medications. Additionally, some patients reported the physical discomfort and weakness (e.g., impotence) experienced as side-effects of the prescribed medications a reason for their medication non-adherence.

Participant No. 2 (a patient’s mother): "She didn't take the meds for seven to eight months. Her friend had told her ‘Your eyes look different. When you take the medicine, your eyes turn into a strange shape. Get rid of them.’ After seven months, her disease relapsed.”

Participant No. 6 (a patient’s husband): "If we go to a party somewhere and someone asks her, ‘Oh, you take drugs?’ … But that person is not aware of the matter, cause she might look all well, and that person doesn’t know what’s actually happening in my wife’s mind, who then has to admit that she is alright."

Participant No. 7 (a patient’s mother): "At one point at work, some colleagues told him, ‘You will become addicted to the medicines, you will get sick.’ Then, he put the medicines aside and became pessimistic about his work. ‘This job has made me sick,’ so he said and left his job all of a sudden. He had a great job, not a difficult one. He could manage it by himself very easily.”

Participant No. 3 (a patient’s mother): “My son had gone to a doctor to remove the corn on his feet. The doctor had checked his medicine prescriptions and asked, ‘What are these you’re taking? You won’t be able to conceive a baby in the future. It’ll affect you poorly’ and so on. My son keeps repeating what the doctor told him.”

Participant No. 1 (a patient’s mother): "That emergency nurse who came to our house told us to change her doctor. Since then, she has kept repeating this sentence. She threw out all her medicines.”

Participant No. 3 (a patient’s mother): “Since the beginning of the new year, he’s began to no longer take his medications. In Khandevaneh, Footnote 1 Mr. Mehran Ghafourian (a famous Iranian actor) said, ‘I was in a bad mood ... I had depression. I put the medications aside and started exercising.’ My son stopped taking his medicines on hearing those words. I asked him many times to go see a doctor but he said no. He continued to not take his medicines and then his disorder worsened. He was frequently beating us up until we took him to the hospital with the help of the police.”

Participant No. 3 (a patient’s mother): “There was a child psychiatrist on a TV talk. We took our son to her office. We used to visit a counselor as well. The psychiatrist prescribed him some medications. We didn’t know what the medications were. He was taking his medicines. In the middle of therapy, we stopped it. Then, my son-in-law, who is a doctor, said ‘Dr. A -his professor- is a very good doctor.’ My son used to go to Dr. A. earlier when he was a college student. He was taking medicines and he believed in him so much. Then again, my eldest daughter, who is a physician, said ‘Dr. B. is a very helpful therapist. All the doctors, engineers, and educated people go to visit him.’ Then he went there ... And two years ago, I took him to Dr. S. too, to help him get rid of his substance abuse." (This participant named seven different doctors).

Participant No. 4 (a patient’s son) discussed the reasons for the patient’s refusal to take the medications and said: "Well, he doesn't actually believe in the disorder being a real one (in the manic episode). Maybe now he takes the pill in front of you, but you know that it is not something that bothers him. You take pills more easily if you have actual pain, but when you don’t, you ask yourself ‘Why do I have to take all these pills?”

Participant No. 11 (a patient’s sister): “We can note the poor behaviors of those around him. He considers any weaknesses he experiences (e.g., sexual problems) a side-effect of the medicines he’s taking. And he’s linking everything to the medicines and thinking they’re going to make him different from the others.”

The findings of this study regarding the viewpoints of the family members of patients with BD-I were categorized into five themes. Although qualitative studies do not allow for the identification of the extent and relative importance of every condition, recurrent themes and concepts stated by the participants at different individual and social levels were extracted.

Research suggests that there is a relationship between families’ knowledge and beliefs about the disorder and the patients’ medication adherence [ 12 ]. The attitudes and knowledge of the family members have a significant influence on the patient’s own beliefs and attitudes and affect the patient’s decision about treatment compliance [ 18 ]. In agreement with previous studies [ 19 , 20 ], the family caretakers in this study were shown to lack sufficient information and knowledge about the nature of BD-I. In addition, many participants had inaccurate or false information and insisted on these false beliefs. A review study on treatment acceptance found that brief interventions focused on relapse prevention and psychoeducation-based interventions have the greatest impact on relapse prevention [ 21 ]. Maintaining the patients’ circadian rhythms (especially sleep rhythm), controlling activity levels, verifying and controlling initial symptoms of mania and depressive episodes, and not using narcotics or stimulants have been recommended in approved psychotherapy protocols for bipolar patients [ 22 ]. Nonetheless, the participants in this study did not discuss any of these important factors. The lack of knowledge about these important issues among families can have a significant impact on relapse and treatment non-adherence in the patients. These points need to be further emphasized in training patients’ families.

In a qualitative study on bipolar patients and their families, Peters, Pontin, Lobban, and Morriss [ 23 ] found that the viewpoints of patients and their families play an important role in managing the disorder; however, the families usually get despondent about participating in this process, and their perception was that some mental health workers believe that family involvement makes their work more complicated. Meanwhile, the present study showed that, in Iran, families do not have enough information about their role in preventing disorder relapse and attribute their patient’s relapse only to factors such as medication withdrawal, unemployment, lack of community support, and financial problems. Most of them believed that if everything goes as the patient wishes, the disorder will not relapse.

Furthermore, the participants did not have adequate information about the non-pharmacological treatment options available for this disorder and the role that psychologists can play in helping the patients enhance their medication adherence and prevent the symptoms of relapse. A variety of behavioral, cognitive, and emotion-focused interventions are used in the management of bipolar disorders [ 22 ]. Nevertheless, the participants did not have sufficient knowledge about these treatments. The observation that many psychologists in Iran appear unwilling to participate in the treatment of bipolar disorder patients seems to play a role in this lack of knowledge. According to Farhoudian et al. [ 24 ], only about 1.5% of all the studies on psychiatric disorders conducted in Iran between 1973 and 2003 involved bipolar and cyclothymic patients. In a qualitative study on bipolar-II patients and their families, Fisher et al. [ 25 ] found that the number of resources available to patients for deciding about their treatment has increased and their priorities have been given increasing attention; yet, the patients’ and their families’ preferences are not fully considered.

Similar to the studies carried out by Jönsson, Wijk, Skärsäter & Danielson [ 26 ] and Shamsaei, Mohamad Khan Kermanshahi, and Vanaki [ 27 ], in the present study, the patients and their families were struggling with the acceptance, understanding, and management of the disorder. According to the participants, the families’ lack of insight into the patients’ disorder contributed significantly to their medication non-adherence. This finding is in line with Scott and Pope’s [ 28 ] research, but Delmas, Proudfoot, Parker, and Manicavasagar [ 29 ] stated that the rejection of treatment is a complex issue that depends on various factors.