- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

How Singapore is Pioneering the Way to Creating a Greener Urban Environment

..jpg?1644514229)

- Written by Jullia Joson

- Published on February 13, 2022

Singapore as of late is continually building its reputation as a City in Nature , with Singaporean design long having a strong consciousness to acknowledge that green spaces matter. Urban planners and architects alike have taken a conscientious decision to weave in nature throughout the city as it continues to uproot new buildings and developments, incorporating the implementation of plant life in any form, whether it be through green roofs, cascading vertical gardens, or verdant walls.

This article will explore the pioneering actions taking place in Singapore to create a more biodiverse city and nation, and how this provides a view of how other major cities can adopt similar initiatives over the next decade to provide a blueprint for the future.

Landscape architects, Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl , and the Singaporean government statutory board, National Parks Board , have led the way in creating the biodiverse garden-filled city that Singapore is today. Additionally, the research of Yun Hye Hwang of the National University of Singapore and the Future Cities Lab is presently focused on exploring how to shape sustainable cities and settlement systems through science, by design.

Singapore is already leading the way in efforts to create a greener urban environment following the aftermath of COP26 , and whilst its initiative to green Singapore was originally focused on giving the city-state a distinct and intentionally desirable image, today this approach is praised for its ability to tackle issues surrounding urban heat, assist with sustainable water management, and improve biodiversity in the city. Several projects have been implemented to continue dealing with these raising issues and providing sustainable design solutions to further the 'greening' of the city.

Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park by Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl is one of Singapore's most popular heartland parks. As part of a much-needed park upgrade and plans to improve the capacity of the Kallang channel along the edge of the park, works were carried out to transform what was once a utilitarian concrete channel into a naturalized river, creating new spaces for the community to enjoy.

"The project was designed to maximize the catchment of water that falls naturally on the island, as well as creating a sense of ownership that will run through generations, so people will want to protect the natural environment." – Leonard Ng, Country Director

The project is part of the Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters (ABC Waters) Program , a long-term initiative of Singapore's Public Utilities Board to transform the country's water bodies beyond their functions of drainage and water supply, into vibrant new spaces for community bonding and recreation.

"The project encourages a biodiverse ecosystem – with birds and otters, among others, colonising the space because it was designed for people and nature to coexist in harmony. When people feel closer to nature and want to preserve it, this is successful biophilic design - using nature to energise and charge people and allowing them to reconnect with nature as our ancestors did." – Leonard Ng, Country Director

Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl (with CPG Consultants) was also responsible for some of the developments at Jurong Lake Gardens , Singapore's first national gardens in the heartlands. The 53-hectare Lakeside Garden aims to restore the landscape heritage of the swamp and forest as a canvas for recreation and community activities. The design is reminiscent of a conscious effort to bring back the nature that was once unique to the Jurong area.

.jpg?1644514319)

Lastly for Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl's landscape projects is Kampung Admiralty (with WOHA), a flagship project that brings together a multitude of programs under one roof. WOHA’s architectural scheme builds upon a layered 'club sandwich' approach. The abundance of greenery present within the design of the housing development serves as an ideal venue for the community to relax and strengthen their relationships with one another, with tree planting strategies comprising the likes of biodiversity, foliage, and fruit trees.

._1.jpg?1644514203)

Future Cities Lab Global aims to strengthen the capacity of Singapore and Switzerland to research, understand, and actively respond to the challenges of global environmental sustainability. Professor Thomas Schröpfer from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (a Principal Investigator at the Future Cities Lab Global) comments:

"Singapore has been a very interesting case study to look at as it is very dense and there is an extreme pressure on development. As it grows, the only way the city can go is up - to become a vertical city. Over the last 10 years the government has introduced new policies that incentivise green architecture and there are many interesting cases in the context of Singapore – within buildings, as well in the urban design strategies that architects deploy."

Future Cities Lab's research continues to look into the environmental performance of green buildings, improving the urban climate, assisting the issues of overheating through cooling, and measuring the positive impact on biodiversity. They believe that the main challenge in achieving a 'city in nature' is the public acceptance that humans need to coexist with other living beings.

Yun Hye Hwang from the National University of Singapore (NUS) is continually exploring the possibilities of growing connections between academic findings and practical applications of urban greening in real-world situations, believing that green spaces are vital to building quality of life.

The Ventus Naturalized Garden on the main campus of NUS is a prime example of alternative landscape technology that allows spontaneous plants to overgrow the existing monotonous campus lawn with minimal design interventions. It provides a connection between a woodland park and a secondary forest, demonstrating that even a small piece of land can accommodate a variety of flora, whilst still serving as part of an ecological network at the city scale.

In 2021, the Singapore government launched its Green Plan 2030 , a whole-of-nation movement to get every Singaporean on board; getting everyone motivated to help transform Singapore into a glowing global city of sustainability. Some key programs of the Green Plan include setting aside 50% more land (around 200 hectares) for nature parks which will all be within a 10-minute walk to a respective household and aiming to plant one million more trees across the island to absorb more CO2, resulting in the population enjoying cleaner air, and cooler shade.

With the vision of creating a City in a Garden and enhancing the community's overall wellbeing, the National Parks Board of Singapore has spent decades aiming to 'green' its roads and infrastructure, transforming the country's parks and gardens into spaces welcome for everyone to enjoy, and setting aside areas of core biodiversity to conserve Singapore's native biodiversity. As Singapore continually transitions into a City of Nature, a biophilic design approach is important in restoring habitats and ensuring that the wider community is engaged in sustaining the national greening efforts.

Today, Singapore is one of the greenest cities in the world. The lush urban greenery that we have is a result of sustained and dedicated efforts to green up Singapore over the past few decades." – Damian Tang, Senior Director/Design, National Parks Board

Following challenges like extreme weather patterns induced by climate change and increased urbanization, there is an evergrowing demand to build a more liveable, sustainable, and climate-resilient Singapore for present and future generations. National Parks Board also runs over 3,500 educational programs across their various green spaces which are key in enabling the community a closer experience of nature and in promoting mental wellbeing. Tang shares that the City in Nature vision is the country's next bound of urban planning:

“At National Parks Board, we have five key strategies to transform Singapore into a City in Nature: conserving and extending Singapore’s natural capital; intensifying nature in gardens and parks; restoring nature into the urban landscape; strengthening connectivity between Singapore’s green spaces; developing excellence in veterinary care, animal and wildlife management.” – Damian Tang, Senior Director/Design, National Parks Board

As of today, almost half of Singapore's land is covered in green space and many of its citizens benefitted from the use of the implemented parks during the lockdowns that were most notable during the height of the pandemic, acting as green lungs, inviting the opportunity breathing and exercising space within a dense city environment.

Image gallery

..jpg?1644514229)

- Sustainability

想阅读文章的中文版本吗?

..jpg?1644514229)

新加坡如何在打造绿色城市环境中引领先锋

You've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

Government agencies communicate via .gov.sg websites (e.g. go.gov.sg/open) . Trusted website s

Look for a lock ( ) or https:// as an added precaution. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

#ChallengeAccepted Singapore's Urban Planning

As a small city-state with limited land, Singapore doesn’t have the luxury of space for all our different needs. How might we cram in more homes, schools, hospitals, offices, industries, transport for more people? How do we balance building facilities with preserving nature? And how do we account for changes the future can bring?

We look ahead, and plan. #ChallengeAccepted

Singapore’s urban planning approach takes the long view, with both the Long Term Plan (formerly known as Concept Plan) and the Master Plan.

The Long Term Plan provides broad strategies for Singapore’s physical development over the next 40-50 years, so that we can meet our population and development needs. Previous versions have set out Singapore’s critical infrastructure like our MRT system and airport, and developed the strategy for Jurong Island.

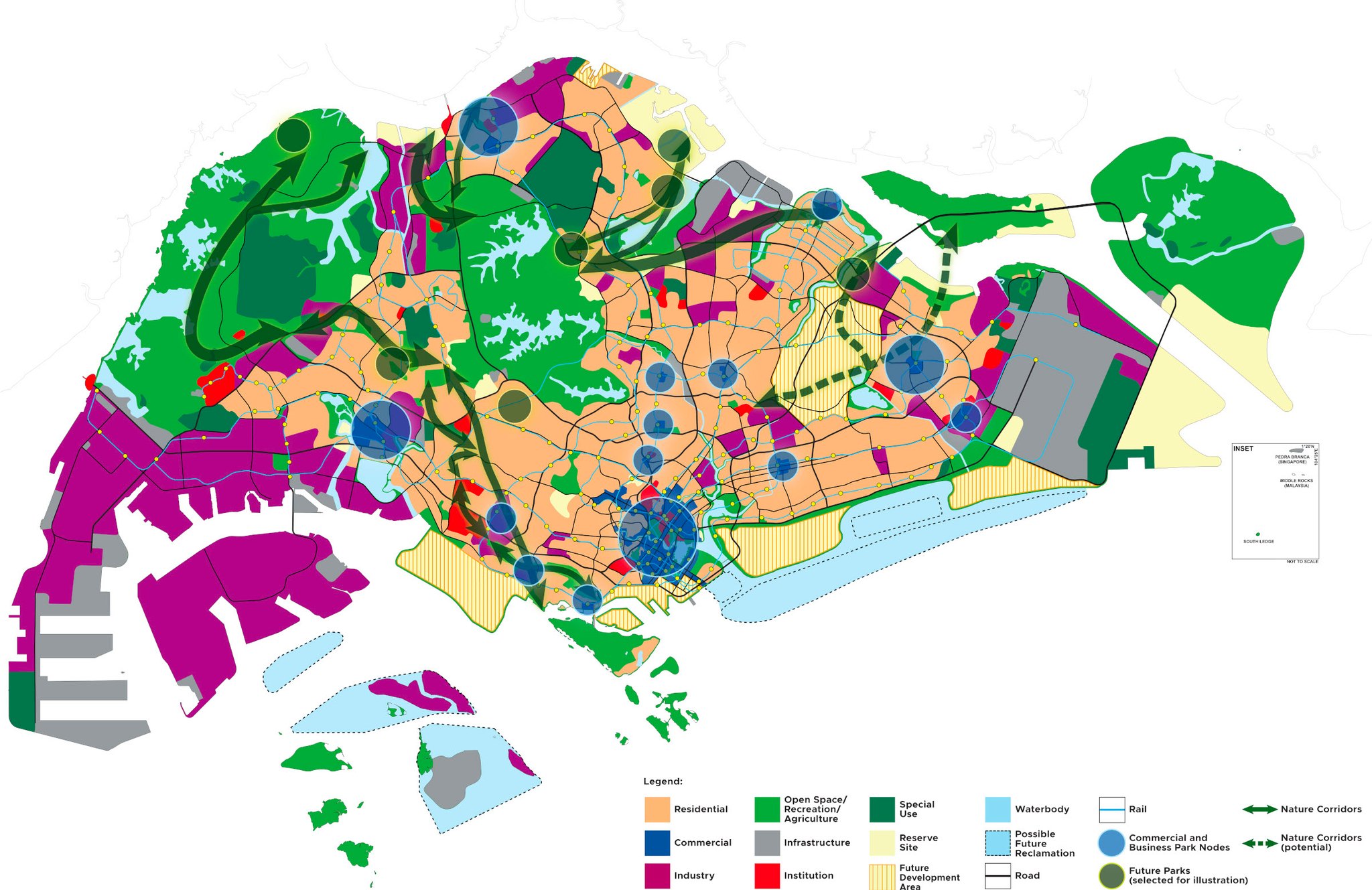

On the other hand, the Master Plan digs into the details. It’s reviewed once every five years, and focuses on specific plots of land to guide Singapore’s development over the next 10-15 years. For example, the 2003 Master Plan announced the Southern Ridges, which would link the Mount Faber, Telok Blangah Hill, and Kent Ridge.

In Apr 2019, then-Minister for National Development Lawrence Wong said, “space will always be a constraint on our little island. But through human ingenuity, we can come up with innovative ways to overcome our space constraints — by optimising land use.” And build a Singapore that is liveable and enjoyable for all.

Check out URA’s latest 50-year plan here .

Visit ConnexionSG Facebook & Instagram

Format Brief City Singapore Metro Area Singapore Location Type Central Business District Land Uses Entertainment Hotel Mixed Residential Open space Retail Skating Rink Keywords Accessible transportation network Education Garden Gathering space Light show Outdoor activities Public art Revitalization ULI Urban Open Space Award 2015 Finalist Waterfront promenade Site Size 140 acres acres hectares Date Started 1970 Date Opened 2010

A brief is a short version of a case study.

Located at the heart of Singapore’s city center, against the backdrop of its signature skyline, Marina Bay presents an exciting array of opportunities for living, working, and playing. A successful example of Singapore’s long-term planning, the larger Marina Bay area was progressively reclaimed over a 40-year period starting in the 1970s. The central business district was seamlessly extended, and a new city center was created around an urban waterfront. This development aligns with Singapore’s plan for continued growth as a business and financial hub by raising the city-state’s international profile while stimulating growth and investment.

Become a member today to view this case study.

Unlimited access to this robust content is a key benefit of ULI membership. View a “Free Look” case study to see what you are missing, and consider becoming a member to gain unlimited access to ULI Case Studies.

Project Owner Urban Redevelopment Authority, Singapore

Project Designer Urban Redevelopment Authority, Singapore

Project Website marina-bay.sg

Principal Author(s) Kathleen Carey, Daniel Lobo, Kathryn Craig, Steven Gu, Kelsey Padgham, James Mulligan, David James Rose, Betsy Van Buskirk, Anne Morgan, Craig Chapman

Source Transformative Urban Open Space http://uli.org/awards/transformative-urban-open-space/

Sign in with your ULI account to get started

Don’t have an account? Sign up for a ULI guest account.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, silver cities: planning for an ageing population in singapore. an urban planning policy case study of kampung admiralty.

Archnet-IJAR

ISSN : 2631-6862

Article publication date: 25 April 2022

Issue publication date: 6 June 2022

This paper explores ways in which Singapore adapts its planning policy and practices to meet the needs of its growing silver population, particularly the relationship between ageing related policies and its urban development strategies.

Design/methodology/approach

The research assesses Singapore's urban planning policies for the ageing population against the WHO framework for age-friendly cities using Kampung Admiralty (KA) (a pioneering project of integrated housing cum community for the ageing population) as a case study for the analysis. The methodology adopted includes a post-occupancy evaluation and a walking tour of the selected case study (Kampung Admiralty), and an analysis of Singapore's ageing policies in relation to urban planning governance.

The study examines the role and significance of a multi-agency collaborative governance structure in ageing planning policies with diverse stakeholders in the project. The evaluation carried out on KA reveals the challenges and opportunities in urbanisation planning for the ageing population. This paper concludes by emphasising the potential of multi-collaborative governance and policymaking in creating an inclusive, liveable built environment for the ageing population in Singapore, particularly but also potential implications for other ASEAN tropical cities.

Practical implications

The case study identified key issues in Singapore's urban planning for betterment in ageing and highlighted the requirement for enhancing urban planning strategies.

Originality/value

This article fulfils an identified need for the Singapore government to address the issue of ageing by providing affordable and silver-friendly housing to its ageing population.

- Ageing population

- Inclusive urban planning

- Kampung Admiralty

- Silver cities

Acknowledgements

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors. This research was supported by the JCUA and JCUS cross-collaboration scheme #IRG20200016. The authors would also like to express their thanks to Pedro Santa Rivera for his comments and review on Kampung Admiralty's planning policy and Prince Sultan University for their support.

Azzali, S. , Yew, A.S.Y. , Wong, C. and Chaiechi, T. (2022), "Silver cities: planning for an ageing population in Singapore. An urban planning policy case study of Kampung Admiralty", Archnet-IJAR , Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 281-306. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-09-2021-0252

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Building a Liveable City: Urban Planning and Real Estate

2 July 2019

Khoo Teng Chye, Executive Director, Centre for Liveable Cities, Ministry of National Development | Past Chair, ULI Singapore [This article was first published in CLC Insights]

Since the 1960s, Singapore has been transformed from an overcrowded urban slum into one of the world’s most liveable cities, with a population density that has almost tripled. Urban planning — so vital in building the city — also impacted the real estate industry. How can the industry become more proactive in shaping Singapore’s future? This question can be explored through the four main phases of how urban planning and real estate development have evolved together over the decades.

Four phases of how Singapore has evolved since the 1960s. Source: CLC

1960s to 1970s: Land for Urban Redevelopment and Basic Infrastructure

In the 1960s, faced with overcrowded slums and fragmented land ownership, the government’s top priority was solving the chronic, very serious housing problem and ensuring enough land for new towns and urban renewal. With a successful public housing programme, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) built some 50,000 flats in its first five years, more than the 23,000 flats built by the former Singapore Improvement Trust since 1927.*

Land Acquisition

Then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, in a parliamentary debate, outlined two broad principles for amending legislation on land acquisition: (1) No private landowner should benefit from development at public expense; and (2) Prices paid on acquisition for public purposes should not be higher than what the land would have been worth otherwise. “Increases in land values, because of public development, should not benefit the landowner, but should benefit the community at large,”^ he said.

Hence, the Land Acquisition Act was amended in 1966 to strengthen government powers to acquire land, and to limit compensation. Much of the land the government now owns was acquired by development agencies: HDB for housing, JTC for industrial estates, Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) for the Central Area, Public Utilities Board for utilities, Port of Singapore Authority for the port and Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore for the airport. From 1960 to 2007, land owned by the public sector doubled from 44 per cent to over 85 per cent.

Concept Plan 1971 outlining Singapore’s urban structure for a modern city and safeguarding land for development Source: URA

Land Planning

Once the government became the biggest landowner, it began building new towns and redeveloping the Central Area comprehensively and rapidly. A United Nations Development Programme team, working with a young team of planners, architects and engineers here, drew up the Concept Plan in 1971 after four years of study — Singapore’s first strategic land use and transport blueprint for the urban structure of a modern city.

The real estate industry, quite small then, did not play a significant role in Singapore’s development. The government was nevertheless concerned that, with higher zoning and plot ratios, owners of private developments would enjoy excessive profits. Hence, the development charge, a betterment tax, was introduced and conscientiously implemented. This was unlike in Britain, where the idea came from, as a lack of political consensus there restricted its implementation.

The urban planning system then was inherited from the colonial-era Town Planning Act, and a 1958 master plan too rigid and inappropriate for a rapidly growing Singapore. Based on the Concept Plan, agencies drew up their own plans for HDB towns, JTC industrial parks, URA’s Central Area plans and other infrastructure plans. The Planning Department’s main task was to ensure that land was carefully safeguarded for new towns, the Central Area, roads, and subway and utility reserves.

1970s to 1980s: Building the City in Partnership with the Private Sector

The task of urban renewal now began in earnest, as URA became planner and master developer of the Central Business District.

The key person responsible was Alan Choe, my first boss at URA, a young, dynamic architect-planner who learnt a lot about urban renewal in the West, especially from the Boston Redevelopment Authority. He adopted some of Boston’s methods, wisely adapted to suit Singapore. As an architect, he developed very detailed urban design guidelines for places like Shenton Way, Golden Shoe District, the Orchard Road belt and the Golden Mile strip.

URA Sale of Sites Source: URA , Changing the face of Singapore through the URA sale of sites, 1995, Pg 5

What distinguished Singapore’s approach from many other cities was how the private sector was involved to implement the plan through URA’s Sale of Sites programme (now the Government Land Sales programme). It was creatively conceived to involve developers through a transparent tender process. As long as developers built according to guidelines, they had no problem obtaining planning approval. To attract bidders, incentives such as property tax concessions as well as financing through a 10-year instalment plan were given. All these significantly derisked projects by reducing uncertainty and approval time.

However, even with these incentives, businessmen had to be persuaded to delve into the risky business of real estate. Choe told of how he had to call on business people like S.P. Tao, a shipping tycoon then, to tender for URA sites. Choe had to sell the new city vision, how the government would make it happen in partnership with the private sector, with URA providing the planning vision and guidance, putting in infrastructure and coordinating overall development as master developer.

This was Singapore’s Public-Private-Partnership approach to urban renewal. The approach quickly gained confidence among developers risking their capital, who saw the tremendous upside of helping to build a rapidly growing city.

The sale of sites programme was a key instrument to encourage certain types of development, such as offices for financial institutions, shopping, entertainment and hotels along Orchard Road and the Havelock Road belt. It also promoted high-density living, with a new housing typology in high-rise condominiums with green spaces and community facilities based on planning guidelines.

Again, Choe, as an architect, introduced the idea of awarding sites by giving design very serious consideration. For developers, the stakes became so high that they hired top international architects like I.M. Pei (Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation Building), Kenzo Tange (Overseas Union Bank Centre), Paul Rudolph (Concourse) and John Portman (Marina Square).

OCBC Building I.M. Pei

OUB Centre Kenzo Tange

Concourse Paul Rudolph

Marina Square John Portman

At that time, URA’s guidelines were not publicised, so there was uncertainty over planning requirements. This lack of transparency made public officials susceptible to corrupt practices. Property had a boom-and-bust market, with the government releasing more land during periods of boom and withholding sales when prices fell. Attractive financial incentives also created a volatile market.

Things came to a head, and Member of Parliament Tan Soo Khoon, in a famous speech in 1986, called the property market a “casino”, with URA as “banker”. This was after a property market crash when some developers could not find funds to continue development, and returned the sites to URA undeveloped. A Cabinet minister committed suicide when investigated by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau.

The new city was being built in partnership with the private sector, but the planning system needed to catch up. These events prompted a serious overhaul of the planning regime when S. Dhanabalan took over as National Development Minister in 1987.

1990s to 2000s: Building a City of Character

Changes to the planning system.

The changes were quite sweeping, making the system more open, transparent and stable. I was part of the team that brought about many of these changes, as MND’s first Director of Strategic Planning, working closely with Lim Hng Kiang, then Deputy Secretary.

URA took on a clearer role as planner and regulator, and no longer as developer. It returned most of its land holdings. Zoning was simplified and plot ratio calculations streamlined with the abolition of net floor area, so that only one parameter, gross floor area, was used. This removed a lot of administrative effort and uncertainty under the old regime. A team led by MND created what is now known as the development charge table, which tells developers upfront what they must pay.

Headline ‘Developers give up two URA land parcels’ Source: Singapore Monitor, 28 April 1984 Full article here

Headline ‘Option for Pontiac to revive Rahardja Centre project’ Source: Times, 3 Aug 1989

With the new transparency, the real estate industry began to attract international capital, and new instruments like Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), which were pioneered by Singapore in this region, resulted in a more mature and sophisticated capital market.

All financial incentives for sale of sites were withdrawn as, by now, the banking and finance industry had the confidence and expertise to finance development. Land was released in a steady stream rather than along with market vagaries.

However, a surplus of capital internationally and Singapore being seen as a safe haven meant that the government had to periodically intervene, especially in the residential property market, with cooling measures.

The 1991 Concept Plan — unveiled as “ Living the Next Lap ” — envisaged building a northeast corridor and decentralising with regional and subregional centres. The master plan became a forward-looking and public plan with the introduction of Development Guide Plans (DGPs), which clearly expressed planning intentions for 55 DGP areas, with clear zoning, plot ratios and other detailed urban design guidelines, so that developers knew exactly what they were allowed to build.

A Liveable and Sustainable City

There was also a continuing focus on building a liveable, sustainable city of character.

There began in the late 1980s a strong emphasis on retaining built heritage. URA did extensive surveys of historic areas, and drew up a conservation master plan and strategy which involved URA becoming the conservation authority, setting guidelines for conserving buildings, gazetting buildings and districts, and bringing in the private sector, again using the sale of sites mechanism. Projects such as Clarke Quay, Bugis Junction and Chijmes were sold, as were many shophouses in Chinatown, Little India and Kampong Glam.

The Singapore River master plan saw the creation of a district of old warehouses adaptively reused for shopping, offices, hotels and homes, juxtaposed with modern buildings. New modes of sale were experimented with, such as auctions, the two-envelope system, and fixed land prices for the two integrated resort projects. The Marina Bay Financial Centre (MBFC) was sold using an option pricing method to reduce development risk, as the objective was to sell a big piece of land for master development by the private sector.

Clover By The Park condominium next to Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters features at Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park. Source: littledayout.com

To advance sustainability and make the city greener and more liveable, more emphasis was placed on promoting Green Mark buildings and high-rise greenery. The Active, Beautiful, Clean (ABC) Waters programme saw strong interest in creating water projects, which commanded a premium. Projects along the waterway in Punggol Eco-town all began to include variations of “water” in their names.

The sale of sites programme was also used to promote sustainable green buildings, with sites sold by tender being required to achieve a minimum Green Mark in selected strategic areas such as Marina Bay, Jurong Lake District, Kallang Riverside, Paya Lebar Central, Woodlands Regional Centre and Punggol Eco-town. Today, sites in strategic areas are required to be designed and built using the Design for Manufacturing and Assembly and Building Information Modelling systems.

As Singapore has come a long way as a well-planned, liveable and sustainable city, the real estate industry, now highly sophisticated and professional, also continues to innovate.

The transparency of a forward-looking master plan also gave rise to a new phenomenon of en-bloc development, flourishing especially during market upcycles, as owners of strata titles and even landed properties banded together to sell their properties for redevelopment. This helped to realise the master plan, while government policy facilitated this with lower thresholds of ownership.

WHAT’S NEXT?

But what’s next for Singapore — how will the city develop? How should we plan for it? How can the real estate industry help to shape the future?

Continuous Building, and Draft Master Plan 2019

As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has said, “we are not done building Singapore yet”.** There are many exciting new opportunities at Marina Bay, Greater Southern Waterfront, Jurong Lake District and, further down the line, Paya Lebar when the airbase is closed. Exhibitions on these plans, such as the one on the draft 2019 Master Plan at the URA Centre, will help people understand the challenges of building a liveable and sustainable city with all its constraints. While some precious greenery will be developed, many new ideas such as nature parks will more than replace the losses. To face new challenges, Singapore has to continue to innovate systemically, like before.

Challenges for Singapore

What are these new challenges?

Climate change, changing demographics (especially ageing and a more diverse society), rapid technological change, social media, lifestyle trends towards co-working, co-living, a sharing economy with ride-sharing, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence and big data.

Beyond the Master Plan, in order to solve the problems these challenges will bring, and create new opportunities, more systemic ideas are needed. For example, building a city in nature, or a city for all ages.

But what is the role of the real estate industry? For universities, research and education in urban systems is critical. Singapore has built up a significant store of knowledge, which should be shared, and used to create new knowledge. Our universities are actively undertaking urban systems research with CLC and other agencies with studio projects such as in Tampines, one-north, and Orchard Road. The National University of Singapore (NUS) is rather proud that its real estate department is just about the only one in the world that is part of the architecture and urban planning school rather than the business school.

CapitaLand-CDL Joint Venture for Prime Site in Sengkang Centre. Source: CapitaLand Limited (2019). CapitaLand-CDL joint venture wins prime site in Sengkang Central

Involvement of Other Stakeholders

But what role can developers and real estate financial institutions play in shaping the city? I sense that the industry is beginning to take a much broader view of their role. URA has received strong support for its Business Improvement Districts pilot schemes, where property owners come together to do place management for neighbourhoods. Orchard Road Business Association is active in reshaping Orchard Road. Developers are becoming master developers, rather than being led by government. In Sengkang, CapitaLand and City Developments Limited are building an integrated commercial-cum-community development including a community centre and hawker centre.

CLC and URA sponsored the Urban Land Institute (ULI), an international organisation of real estate professionals, to bring in an international panel to give views on how the private sector can participate in Jurong Lake District . This intensive process included interviewing 60 industry professionals from government, the private sector and academia. New forms of partnership are developing between the public and private sectors.

Internationally, the industry is spreading its wings. Companies are doing city master planning in Asia, Africa and Middle East. Singapore has major integrated city and township projects in Suzhou, Tianjin, Guangzhou and Amaravati. To offer an integrated package, it is also essential to involve smaller companies and other parts of the real estate value chain, such as legal and financial services.

Infrastructure Asia was set up by Enterprise Singapore to promote Singapore as an infrastructure finance hub. There is good potential for the industry to grow, as the region is urbanising very rapidly and the need for well-planned, liveable cities is urgent. Singapore is often looked upon as a model, but how can we better “sell” brand Singapore and public and private sector expertise as an integrated package?

Singapore was built primarily by public sector agencies in the earlier years. Later, the private sector became an active partner, producing a boom period. This was followed by a period of putting in place a good urban planning system and building a highly sophisticated real estate industry.

Can Singapore now become a global hub to take to the world this new partnership between the private and public sectors in creating urban systems solutions? That is our collective challenge.

* Savage, Victor, and Eng Teo. “Singapore Landscape: A Historical Overview of Housing Change.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, vol. 6, no. 1, 1985.

^ Singapore Parliamentary Debates. (10 June 1964). Vol. 23, Col. 25. See also observations by then-P.M. Lee Kuan Yew and then Minister for Law and National Development E. W. Barker during the second and third readings of the Land Acquisition (Amendment No 2) Bill in 1964-66 and Singapore Parliamentary Debates. (16 June 1965). Vol. 23, Col. 811; and (26 October 1966). Vol 25. Col 410.

** Lee, Hsien Loong. “National Day Message 2018.” Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, 8 Aug. 2018, www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/national-daymessage-2018.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Choy Chan Pong and Kwek Sian Choo for their inputs; as well as Phua Shi Hui for research assistance, Koh Buck Song for editing the text and Ng Yong Yi for layout design. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the Ministry of National Development. If you would like to provide feedback on this article, please contact [email protected] .

About the Author

Technologies Driving More Cost-Effective Construction in Singapore

Experts from public and private sectors touch on some of the new technologies being used.

- Construction/Engineering

- Event Recap

- Market Conditions - Technology, New/Disruptive

- Singapore Conference

Sign in with your ULI account to get started

Don’t have an account? Sign up for a ULI guest account.

International Case Studies of Smart Cities: Singapore, Republic of Singapore

Advertisement

Singapore as a long-term case study for tropical urban ecosystem services

- Published: 24 August 2016

- Volume 20 , pages 277–291, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- D. A. Friess 1

5196 Accesses

25 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Ecosystem services have gained rapid interest for understanding urban-environment interactions. However, while the term “ecosystem services” is relatively novel, their principles have influenced urban planning for decades. This study assesses the wealth of urban ecosystem services research conducted in the tropical city state of Singapore, in particular their historical local use and implicit and explicit incorporation into land use planning, and shows how Singapore is exporting their experiences to other cities around the world. Singapore is an important model for urban ecosystem services research, as the nation has experienced rapid urban development and has a 100 % urban population. Singapore also historically utilized ecosystem services in urban decision making long before the concept was popularized. For example, forests were conserved since 1868 for climatic regulation and for the watershed protection services provided to Singapore’s first reservoirs, and green spaces have been conserved for cultural ecosystem services since the 1920s. Urban ecosystem services were formally incorporated into national planning in the 1960s through the “Garden City” urban planning vision. Singapore is now a leading case study for tropical urban climatology and carbon sequestration, exporting its experiences globally through bilateral agreements and the construction of eco-cities in China, and the creation and promotion of a global City Biodiversity Index to assess urban ecosystem service provision in cities across the globe. Consolidating and understanding case study cities such as Singapore is important if we are to understand how to incorporate multiple ecosystem services into large scale planning frameworks, and provides an important tropical example in a research field dominated by western, temperate case studies.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Opportunities for increasing resilience and sustainability of urban social–ecological systems: insights from the urbes and the cities and biodiversity outlook projects.

Maria Schewenius, Timon McPhearson & Thomas Elmqvist

Understanding Urban Regulating Ecosystem Services in the Global South

Urban Nature and Urban Ecosystem Services

While originally named the “Garden City” vision, government agencies now refer to this as the “City in a Garden”.

AGC (2016) Parks and trees act (chapter 216). Attorney-General’s Chambers, Government of Singapore. Singapore

AVA (2014) AVA Vision, Issue 1 2014. Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore, Government of Singapore. Singapore

AVA (2015) Working together as one: annual report 2014/15. Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore, Government of Singapore. Singapore

Bolund P, Hunhammar S (1999) Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol Econ 29:293–301

Article Google Scholar

Brauman KA, Daily GC, Duarte TK, Mooney HA (2007) The nature and value of ecosystem services: an overview highlighting hydrologic services. Ann R Environ Res 32:67–98

Brook BW, Sodhi NS, Ng PKL (2003) Catostrophic extinctions follow deforestation in Singapore. Nature 424:430–423

Caprotti F (2014) Critical research on eco-cities? A walk through the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City, China. Cities 36:10–17

CBD (2012) User’s manual for the City Biodiversity Index. Convention on Biological Diversity. Montreal

Chang I-CC, Leitner H, Sheppard E (2016) A Green Leap forward? Eco-state restructuring and the Tianjin-Binhai Eco-City model. Reg Stud. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2015.1108519

Google Scholar

Chou R, Lee HB (1997) Commercial marine fish farming in Singapore. Aquac Res 28:767–776

Chow WTL, Roth M (2006) Temporal dynamics of the urban heat island of Singapore. Int J Climatol 26:2243–2260

Chow WTL, Cheong BD, Ho BH (2016a) A multimethod approach towards assessing urban flood patterns and its associated vulnerabilities in Singapore. Adv Meteorol 2016:7159132

Chow WTL, Akbar SN, Heng SL, Roth M (2016b) Assessment of measured and perceived microclimates within a tropical urban forest. Urban For Urban Green 16:62–75

Corlett RT (1992) The ecological transformation of Singapore, 1819-1990. J Biogeogr 19:411–420

Corlett RT (1995) Rain forest in the city. National Parks Board, Government of Singapore. Singapore

Costanza R, d’Arge R, de Groot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O’Neill RV, Paruelo J, Raskin RG, Sutton P, van den Belt M (1997) The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387:253–260

Article CAS Google Scholar

Daily GC, Polasky S, Goldstein J, Kareiva PM, Mooney HA, Pejchar L, Ricketts TH, Salzman J, Shallenberger R (2009) Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver. Front Ecol Environ 7:21–28

De Koninck R, Drolet J, Gird M (2008) Singapore: an atlas of perpetual territorial transformation. NUS Press, Singapore

Dobbs C, Nitschke CR, Kendal D (2014) Global drivers and tradeoffs of three urban vegetation ecosystem services. PLoS ONE 9, e113000

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dobby EHG (1940) Singapore: town and country. Geogr Rev 30:84–109

Donato DC, Kauffman JB, Murdiyarso D, Kurnianto S, Stidham M, Kanninen M (2011) Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics. Nat Geosci 4:293–297

Estoque RC, Murayama Y (2013) Landscape pattern and ecosystem service value changes: implications for environmental sustainability planning for the rapidly urbanizing summer capital of the Philippines. Landsc Urban Plan 116:60–72

Estoque RC, Murayama Y (2014) Measuring sustainability based upon various perspectives: a case study of a hill station in Southeast Asia. Ambio 43:943–956

Estoque RC, Murayama Y (2015) Intensity and spatial pattern of urban land changes in the megacities of Southeast Asia. Land Use Pol 48:213–222

FAO (1976) National plan for development of aquaculture in Singapore. In: Aquaculture Planning in Asia. Aquaculture Development and Coordinating Programme, Food and Agricultural Organization, Bangkok

Fisher B, Turner RK, Morling P (2009) Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol Econ 68:643–653

Friess DA, Phelps J, Leong RC, Lee WK, Wee AKS, Sivasothi N, Oh RRY, Webb EL (2012) Mandai mangrove, Singapore: lessons for the conservation of Southeast Asia’s mangroves. Raffles Bull Zool S25:55–65

Friess DA, Richards DR, Phang VXH (2016) Mangrove forests store high densities of carbon across the tropical urban landscape of Singapore. Urb Ecosyst

Gibson-Hill CA (1950) The fishing boats operated from Singapore Island. J Malayan Branch Royal Asiatic Soc 23:148–170

Gómez-Baggethun E, de Groot R, Lomas PL, Montes C (2010) The history of ecosystem services in economic theory and practice: from early notions to markets and payment schemes. Ecol Econ 69:1209–1218

Gómez-Baggethun E, Gren A, Barton SN, Langemeyer J, McPhearson T, O’Farrell P, Andersson E, Hamstead Z, Kremer P (2013) Urban ecosystem services. In: Elqvist T et al (eds) Urbanization, biodiversity and ecosystem services: challenges and opportunities. Springer, Amsterdam, pp 175–251

Chapter Google Scholar

Grimm NB, Faeth SH, Golubiewski NE, Redman CL, Wu J, Bai X, Briggs JM (2008) Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 319:756–760

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Haase D et al (2014) A quantitative review of urban ecosystem service assessments: concepts, models and implementation. Ambio 43:413–433

Hassan R (1969) Population change and urbanization in Singapore. Civilisations 19:169–188

Henderson J (2013) Urban parks and green spaces in Singapore. Manag Leis 18:213–225

Hill RD (1980) Singapore – an Asian City State. GeoJournal 4:5–12

Hilton MJ, Manning SS (1995) Conversion of coastal habitats in Singapore: indications of unsustainable development. Environ Conserv 22:307–322

Huang S (2001) Planning for a tropical city of excellence: urban development challenges for Singapore in the 21 st century. Built Environ 27:112–128

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: mitigation of climate change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Working Group 3. Geneva

Jim CY (2013) Sustainable urban greening strategies for compact cities in developing and developed economies. Urban Ecosyst 16:741–761

Khan H (1988) Role of agriculture in a City-State Economy: the case of Singapore. ASEAN Econ Bull 5:178–182

Kohsaka et al (2013) Indicators for management of urban biodiversity and ecosystem services: City Biodiversity Index. In Elqvist T et al (eds) Urbanization, biodiversity and ecosystem services: challenges and opportunities. Springer, Amsterdam. pp. 699–718

Kong L, Yeoh BS (1996) Social constructions of nature in urban Singapore. Southeast Asian Stud 34:402–423

Kuan KJ (1988) Environmental improvement in Singapore. Ambio 17:233–237

Lai S, Loke LH, Hilton MJ, Bouma TJ, Todd PA (2015) The effects of urbanization on coastal habitats and the potential for ecological engineering: a Singapore case study. Ocean Coast Manag 103:78–85

Lele S, Springate-Baginski O, Lakerveld R, Deb D, Dash P (2013) Ecosystem services: origins, contributions, pitfalls and alternatives. Conserv Soc 11:343–358

Li Y, Zhu X, Sun X, Wang F (2010) Landscape effects of environmental impact on bay-area wetlands under rapid urban expansion and development policy: a case study of Lianyungang, China. Landsc Urban Plan 94:218–227

Lim J-J (1976) Singapore: surmounting assessables, encountering intangibles. Southeast Asian Affairs 1:319–338

Lundholm JT, Richardson PJ (2010) Habitat analogues for reconciliation ecology in urban and industrial environments. J Appl Ecol 47:966–975

McKinney ML (2002) Urbanization, biodiversity and conservation. Bioscience 52:883–890

MEA (2005) Ecosystems and wellbeing. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Washington DC

Meng M, Zhang J, Wong WY (2015) Intergrated foresight urban planning in Singapore. Urban Des Plan 169:1–13

MEWR (2002) The Singapore green plan 2012. Ministry of Environment and Water Resources, Government of Singapore. Singapore

MEWR (2015) Sustainable Singapore Blueprint 2015. Ministry of Environment and Water Resources, Government of Singapore. Singapore

MND (2013) Land use plan to support Singapore’s future population. Ministry of National Development, Government of Singapore. Singapore

MND 2014. Ministry of National Development. www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/data/budget_2014/download/45%20MND%202014.pdf . Accessed 16 Apr 2016

NCCS (2012) Climate change and Singapore: challenges, opportunities, partnerships. National Climate Change Secretariat, Government of Singapore. Singapore

NEA (2014) Singapore’s third national communication and biennial update report under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. National Environment Agency, Government of Singapore. Singapore

NEA (2016) El Niño and La Niña. National Environment Agency, Government of Singapore. www.nea.gov.sg/training-knowledge/weather-climate/el-nino-la-nina . Accessed 16 Apr 2016

Ngo KM, Turner BL, Muller-Landau HC, Davies SJ, Larjavaara M, Hassan NF, Lum S (2013) Carbon stocks in primary and secondary tropical forests in Singapore. For Ecol Manag 296:81–89

Nguyen VT, Gin KY-H, Reinhard M, Lio C (2012) Occurrence, fate, and fluxes of perfluorochemicals (PFCs) in an urban catchment: Marina Reservoir, Singapore. Water Sci Technol 66:2439–2446

Nichol JE (1993) Monitoring Singapore’s microclimate. Geogr Info Syst 4:51–55

Nieuwolt S (1966) The urban microclimate of Singapore. J Trop Geogr 22:30–37

Nowak DJ, Crane DE (2002) Carbon storage and sequestration by urban trees in the USA. Environ Pollut 116:381–389

NPTD (2013) A sustainable population for a dynamic Singapore. Population white paper. National Population and Talent Division, Ministry of National Development, Government of Singapore. Singapore

O’Dempsey T (2014) Singapore’s changing landscape since c. 1800. In: Barnard T (ed) Nature contained: environmental histories of Singapore. NUS Press, Singapore

Ooi GL (1992) Public policy and park development in Singapore. Land Use Policy 9:64–75

Peng CY, Zhang J (2012) Addressing urban water resource scarcity in China from water resource planning experiences of Singapore. Adv Mater Res 433-440:1213-1218

Phang VXH, Chou LM, Friess DA (2015) Ecosystem carbon stocks across a tropical intertidal habitat mosaic of mangrove forest, seagrass meadow, mudflat and sandbar. Earth Surf Process Landf 40:1387–1400

Power A (2010) Ecosystem services and agriculture: tradeoffs and synergies. Philos Trans R Soc B 365:2959–2971

PUB (2014) Managing stormwater for our future. Public Utilities Board, Government of Singapore. Singapore

PUB (2015) Our water, our future. Public Utilities Board, Government of Singapore. Singapore

Richards DR, Friess DA (2015) A rapid indicator of cultural ecosystem service usage at a fine spatial scale: content analysis of social media photographs. Ecol Indic 53:187–195

Roth M, Chow WTL (2012) A historical review and assessment of urban heat island research in Singapore. Singap J Trop Geogr 33:381–397

Saw LE, Lim FK, Carrasco LR (2015) The relationship between natural park usage and happiness does not hold in a tropical city-state. PLoS ONE 10, e0133781

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Seto KC, Güneralp B, Hutyra LR (2012) Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:16083–16088

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Straits Times (2013) Government to track Singapore’s carbon emissions. The Straits Times. www.straitstimes.com/singapore/government-to-track-singapores-carbon-emissions . Accessed 16 Apr 2016

Straits Times (2016) March 2016 driest and second warmest on record; hot weather to continue. The Straits Times. www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/march-2016-driest-and-second-warmest-on-record-hot-weather-to-continue . Accessed 16 Apr 2016

Swanwick C, Dunnet N, Woolley H (2003) Nature, role and value of green space in towns and cities: an overview. Built Environ 29:94–106

Taha H (1997) Urban climates and heat islands: albedo, evapotranspiration, and anthropogenic heat. Energy Build 25:99–103

Tan PY, Ismail MR (2015) The effects of urban forms on photosynthetically active radiation and urban greenery in a compact city. Urban Ecosyst 18:937–961

Tan PY, Yeo B, Yip WX, Lua HS (2009) Carbon storage and sequestration by urban trees in Singapore. Centre for Urban Greenery and Ecology, National Parks Board, Government of Singapore. Singapore

Tan CL, Wong NH, Jusuf SK (2013a) Outdoor mean radiant temperature estimation in the tropical urban environment. Build Environ 64:118–129

Tan PY, Wang J, Sia A (2013b) Perspectives on five decades of the urban greening of Singapore. Cities 32:24–32

Tan PY, Feng Y, Hwang YH (2016) Deforestation in a tropical compact city (Part A). Sm and Sustain Built Environ 5:47–72

Taylor L, Taylor C, Davis A (2013) The impact of urbanisation on avian species: the inextricable link between people and birds. Urban Ecosyst 16:481–498

Tenerelli P, Demšar U, Luque S (2016) Crowdsourcing indicators for cultural ecosystem services: a geographically weighted approach for mountain landscapes. Ecol Indic 64:237–248

Thiagarajah J, Wong SKM, Richards DR, Friess DA (2015) Historical and contemporary cultural ecosystem service values in the rapidly urbanizing city state of Singapore. Ambio 44:666–677

Tortajada C (2006) Water management in Singapore. Int J Water Res Dev 22:227–240

Turner RK, Daily GC (2008) The ecosystem services framework and natural capital conservation. Environ Res Econ 39:25–35

Uchiyama Y, Hayashi K, Kohsaka R (2015) Typology of cities based on City Biodiversity Index: exploring biodiversity potentials and possible collaborations among Japanese cities. Sustainability 7:14371–14384

UN DESA (2015) World urbanization prospects. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York

URA (2001) Concept Plan 2001. Urban Redevelopment Authority, Government of Singapore. Singapore

URA (2014) Master Plan 2014. Urban Redevelopment Authority, Government of Singapore. Singapore

URA (2015) Parks and waterbodies plan. Urban Redevelopment Authority, Government of Singapore. Singapore

Velasco E, Roth M (2012) Review of Singapore’s air quality and greenhouse gas emissions: current situation and opportunities. J Air Water Manag Assoc 62:625–641

Velasco E, Roth M, Tan SH, Quak M, Nabarro SD, Norford L (2013) The role of vegetation in the CO 2 flux from a tropical urban neighbourhood. Atmos Chem Phys 13:10185–10202

Wang J, Da L, Song K, Li B-L (2008) Temporal variations of surface water quality in urban, suburban and rural areas during rapid urbanization in Shanghai, China. Environ Pollut 152:287–393

Webb R (1998) Urban forestry in Singapore. Arboricultural J 22:271–286

Wheatley JJ (1885) Further notes on the rainfall of Singapore. J Straits Branch Royal Asiatic Soc 15:61–67

Wong TH, Brown RR (2009) The water sensitive city: principles for practice. Water Sci Technol 60(3):673–682

Wong NH, Jusof SK (2010) Study on the microclimate condition along a green pedestrian canyon in Singapore. Archit Sci Rev 53:196–212

Wong NH, Cheong KWD, Yan H, Soh J, Ong CL, Sia A (2002) The effects of rooftop garden on energy consumption of a commercial building in Singapore. Energy Build 35:353–364

Wong NH, Chen Y, Ong CL, Sia A (2003) Investigation of thermal benefits of rooftop garden in the tropical environment. Build Environ 38:261–270

World Bank (2009) Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-City: a case study of an emerging Eco-City in China. Technical Assistance Report 59012, the World Bank, Washington DC

WRI (2015) Aqueduct projected water stress country rankings. World Resources Institute. www.wri.org/sites/default/files/aqueduct-water-stress-country-rankings-technical-note.pdf . Accessed 14 Apr 2016

Yaakub SM, Lim RL, Lim WL, Todd PA (2013) The diversity and distribution of seagrass in Singapore. Nat Singapore 6:105–111

Yaakub SM, McKenzie LJ, Erftemeijer PL, Bouma T, Todd PA (2014) Courage under fire: seagrass persistence adjacent to a highly urbanised city-state. Mar Pollut Bull 83:417–424

Yee AT, Ang WF, Teo S, Liew SC, Tan HT (2010) The present extent of mangrove forests in Singapore. Nat Singapore 3:139–145

Yee AT, Corlett RT, Liew SC, Tan HT (2011) The vegetation of Singapore – an updated map. Gardens Bull Singapore 63:205–212

Yuen B (1996) Creating the garden city: the Singapore experience. Urban Stud 33:955–970

Yuen B, Kong L, Briffett C (1999) Nature and the Singapore resident. GeoJournal 49:323–331

Zhao W, Zhu X, Sun X, Shu Y, Li Y (2015) Water quality changes in response to urban expansion: spatially varying relations and determinants. Environ Sci Pollut Res 22:16977–17011

Ziegler AD, Terry JP, Oliver GJH, Friess DA, Chuah CJ, Chow WTL, Wasson RJ (2014) Increasing Singapore’s resilience to drought. Hydrol Process 28:4543–4548

Ziter C (2016) The biodiversity-ecosystem service relationship in urban areas: a quantitative review. Oikos. doi: 10.1111/oik.02883

Download references

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education (R-109-000-166-112). Thank you to the National Parks Board for their continued support for urban ecosystem services research. Thank you to the National Archives of Singapore, the Ministry of Information and the Arts, Primary Production Department (now the Agri-food & Veterinary Authority) and the Singapore Tourism Board for permission to reproduce their photographs. Thank you to Winston Chow (National University of Singapore) for assisting with the translation of Fig. 5 .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Geography, National University of Singapore, 1 Arts Link, Singapore, 117570, Singapore

D. A. Friess

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to D. A. Friess .

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

SOI Table 1

A summary of data-driven case studies of ecosystem service provision and associated factors conducted in Singapore. (DOCX 26.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Friess, D.A. Singapore as a long-term case study for tropical urban ecosystem services. Urban Ecosyst 20 , 277–291 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-016-0592-7

Download citation

Published : 24 August 2016

Issue Date : April 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-016-0592-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- City biodiversity index

- Cultural ecosystem services

- Garden city

- Urban heat island

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Sustainable cities: innovative urban planning in Singapore

Cities present a sustainability conundrum: though they are the most efficient way to provide infrastructure and services for large populations, they are, in absolute terms, incredibly inefficient.

Cities cover just 2% of the Earth's surface yet consume about 75% of the world's resources, and given that more of the world's population now live in cities than in rural areas, it's clear they are key to tackling climate change and reducing resource use.

Urban administrators face huge challenges to make cities more sustainable. From traffic jams and inefficient buildings to social inequality and housing, the problems are complex and hard to tackle — but not insurmountable.

Some cities are forging ahead with the use of innovative urban planning, technological and governance models, showing that with the right focus and resources, cities can become "smart" or more sustainable.

According to the latest Siemens' Green City Index for Asia , Singapore is the best-performing city in the region when measured against a range of sustainability criteria.

"Singapore is at the leading edge of sustainability," says Nicholas You, chairman of the World Urban Campaign Steering Committee at UN-Habitat . "It's an island state with limited resources so it had no choice but to go green if it wanted to survive economically."

Singapore's experiences have important lessons for other urban centres. Take its water treatment. In 1963, water functionality was shared between multiple ministries and agencies, which made it difficult to formulate a coordinated, long-term strategy.

With a rising population and finite freshwater resources, action was needed, so ministers set up a national water agency, PUB, which became the sole body responsible for the collection, production, distribution and reclamation of water in the city.

Today, its water operation has been transformed. Two thirds of Singapore's land surface is now a water catchment area with water stored in 17 reservoirs, including the Marina Basin, right in the heart of the city.

Called NEWater, wastewater is collected and treated to produce water that's good enough to drink. This meets 30% of the city's water needs, a target that will be increased to 50% of future needs by 2060.

Earlier this year, Siemens was contracted to identify CO2 reduction opportunities in transport, residential and non-industrial buildings, and IT/communications in the Tampines district.

As part of the city's plan to reduce CO2 emissions by 30% by 2030, Siemens will report back in 2013 with implementation costs, a plan to implement the changes and the design of pilots to trail three technological solutions.

"This will be a good test-bed for new technologies to prove what we can do," says Dr Roland Busch, Siemens' CEO of infrastructure and cities sector. "It's a way to demonstrate in the highly competitive environment that is Singapore, that we can bring energy efficiency to the next level in addressing all the basic needs of cities."

EDF and Veolia recently signed an agreement with Singapore's Housing Development Board (HDB), the city-state's largest developer, to develop software that will help it develop sustainable, urban planning solutions in HDB towns.

ForCity will simulate the built environment of a city and its impact on resources, the environment, people and intervention costs to help the HDB make its towns function more efficiently and become more pleasant to live in. The tool will be trialed in the Jurong East district of Singapore.

Transport is another sector that has seen investment recently. On an island of 4.8 million people with limited space, moving people around as efficiently as possible is key to its economic viability. A decade ago, city administrators warned that congestion could cost Singapore's economy $2-3bn a year if transport infrastructure was not improved.

Then, there were two separate transport-charging systems in the city: road tolls and public transport, including the metro and buses. But since 2009, after a series of smart card innovations, people have been able to use e-Symphony, an IBM-designed payment card that can be used to pay for road tolls, bus travel, taxis, the metro, and even shopping.

The card can process 20 million fare transactions a day and collects extensive traffic data, allowing city administrators to constantly tweak routes to ensure the most efficient journeys and minimise congestion.

All these measures combine to make Singapore a smarter city. "What we have done is to research and try to distill the principles for Singapore's success in sustainable urban development – we call it a liveability framework," says Khoo Teng Chye, executive director at the Centre for Liveable Cities based in Singapore.

"Quality of life, environmental sustainability and competitive economics. These are the components that make cities liveable."

As the competition for resources increases and cities expand to accommodate rising populations, even those without the geographic constraints of Singapore will have to embrace smart city principles. If they don't, they will lose out financially, unable to attract businesses and talent from cities that do. The planet simply can't sustain current levels of resource use and environmental degradation. It's not a choice; cities have to change.

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional . Become a GSB member to get more stories like this direct to your inbox

- Built Environment

- Smart cities

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, and also known as the Lion City, is a leading global city-state that is situated 137km (81 miles) north of the equator, and just south of Peninsular Malaysia. Singapore is one of the most densely populated independent country in the world.

Urban Planning Traditions and Processes Analysis. As in Curitiba's case, a thorough examination of Singapore's planning history and the consideration of theories and practices used in the process, their evolution and innovations were relevant to answer these questions. ... Newman P (2013) Biophilic urbanism: a case study on Singapore. Aust ...

In 2021, the Singapore government launched its Green Plan 2030, a whole-of-nation movement to get every Singaporean on board; getting everyone motivated to help transform Singapore into a glowing ...

Graphical representation of the structure of the building analysis (FONTE ONLINE) 4 .1. De ta i ls o f t h e pro j ec t. Marina Bay Sands is an integrated resort, conceived by architect Moshe ...

Planning Transport and Mobility in Singapore, the "Transit Metropolis" ... A Case Study on Urban Transportation Development and Management in Singapore. Urban Infrastructure Development, 26. Brandon Chye is an MPhil candidate in Development Studies at Oxford's Department of International Development. His main research focuses on the study ...

Abstract. This paper outlines the characteristics of an emerging new planning paradigm called biophilic urbanism by detailing a case study of Singapore, which, over a number of years, has ...

We look ahead, and plan. #ChallengeAccepted. Singapore's urban planning approach takes the long view, with both the Long Term Plan (formerly known as Concept Plan) and the Master Plan. The Long Term Plan provides broad strategies for Singapore's physical development over the next 40-50 years, so that we can meet our population and ...

Marina Bay. A brief is a short version of a case study. Located at the heart of Singapore's city center, against the backdrop of its signature skyline, Marina Bay presents an exciting array of opportunities for living, working, and playing. A successful example of Singapore's long-term planning, the larger Marina Bay area was progressively ...

Singapore, with a land area of 690 km 2 , is located just 1° north of the equator in the subregion of Southeast Asia. It has a present population of 5 million and a pro-jected population under its long-term development plan of 6.5 million. Singapore is at the same time both a city and a country, with the city center occupying an area of about ...

The methodology adopted includes a post-occupancy evaluation and a walking tour of the selected case study (Kampung Admiralty), and an analysis of Singapore's ageing policies in relation to urban planning governance.,The study examines the role and significance of a multi-agency collaborative governance structure in ageing planning policies ...

Describes the transformation of Singapore's city center from an overcrowded, slum-filled decrepit urban core into the modern global financial center of today, and reviews how the urban renewal process worked through legislative, policy, and government organizational reforms. Three selected areas along the waterfront, the Golden Shoe District, the Singapore River, and the Marina Bay ...

planning information for any land parcel. These ideas helped shape the vision for the ePlanner, a one-stop geospatial analytics tool. The Challenge Having quick and easy access to data is the foundation for using data analytics to support effective digital urban planning. Since the 1990s, Singapore's Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA)

The National University of Singapore (NUS) is rather proud that its real estate department is just about the only one in the world that is part of the architecture and urban planning school rather than the business school. CapitaLand-CDL Joint Venture for Prime Site in Sengkang Centre. Source: CapitaLand Limited (2019).

This case study is one of ten international studies developed by the Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements (KRIHS), in association with the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), for the cities of Anyang, Medellin, Namyangju, Orlando, Pangyo, Rio de Janeiro, Santander, Singapore, Songdo, and Tel Aviv. At the IDB, the Competitiveness and Innovation Division (CTI), the Fiscal and ...

Singapore Blueprint (SSB), which outlined five-year plans to make Singapore a liveable and lively city-state, and key strategies for Singapore's sustainable development in the long term. Singapore is also pursuing green growth actively. The National Climate Change Strategy 2012 places emphasis on green growth opportunities.

Adopting a case study of the Singapore River waterfront, this paper analyses three forms of urban reclamation. They include reclaiming functionality, aimed at infusing the waterfront with new land uses; reclaiming access, as a way of opening up the landscape to more people; and reclaiming the local, as a way to commemorate local cultures and ...

Singapore is an important case study through which to study tropical urban ecosystem services, as it has experienced rapid urbanization in recent decades, though its structured urban planning framework has put urban ecosystem services central to decision making for almost 150 years. There are also secondary reasons to highlight Singapore as an ...

According to the latest Siemens' Green City Index for Asia, Singapore is the best-performing city in the region when measured against a range of sustainability criteria. "Singapore is at the ...

This study selects Singapore as a case study area to demonstrate the proposed framework for the following reasons. First, Singapore is a cosmopolitan island city-state with approximately five million residents. It is well-known for its economic success and sophisticated urban planning and management.

Case Study of a Modern Day Eden - Singapore. " Almost all of Singapore is less than 30 years old, the city represents the ideological production of the past three decades in its pure form, uncontaminated by surviving contextual remnants. It is managed by a regime that has excluded accident and randomness; even its nature is entirely remade.

The methodology adopted includes a post-occupancy evaluation and a walking tour of the selected case study (Kampung Admiralty), and an analysis of Singapore's ageing policies in relation to urban ...

Third, using Singapore as a case study, this paper provides insights for government planning agencies and enhances the comprehensive understanding of the spatial equity of regional parks, community parks, and urban parks overall, from the perspective of recreational opportunities and recreational environment quality.

The 2019 Master Plan According to the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), the URA Master Plan is a statutory land use plan that guides Singapore's developments in the medium term over the next 10 to 15 years. Figure 3. Master Plan Map for Singapore, 2019 The current Master Plan, released in 2019, focuses on the themes of livable and inclusive communities, sustainability, sustainable mobility ...