When viewing this topic in a different language, you may notice some differences in the way the content is structured, but it still reflects the latest evidence-based guidance.

Breech presentation

- Overview

- Theory

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Follow up

- Resources

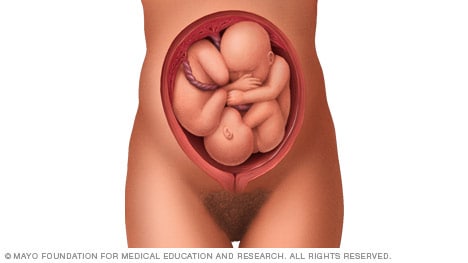

Breech presentation refers to the baby presenting for delivery with the buttocks or feet first rather than head.

Associated with increased morbidity and mortality for the mother in terms of emergency cesarean section and placenta previa; and for the baby in terms of preterm birth, small fetal size, congenital anomalies, and perinatal mortality.

Incidence decreases as pregnancy progresses and by term occurs in 3% to 4% of singleton term pregnancies.

Treatment options include external cephalic version to increase the likelihood of vaginal birth or a planned cesarean section, the optimal gestation being 37 and 39 weeks, respectively.

Planned cesarean section is considered the safest form of delivery for infants with a persisting breech presentation at term.

Breech presentation in pregnancy occurs when a baby presents with the buttocks or feet rather than the head first (cephalic presentation) and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality for both the mother and the baby. [1] Cunningham F, Gant N, Leveno K, et al. Williams obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1997. [2] Kish K, Collea JV. Malpresentation and cord prolapse. In: DeCherney AH, Nathan L, eds. Current obstetric and gynecologic diagnosis and treatment. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2002. There is good current evidence regarding effective management of breech presentation in late pregnancy using external cephalic version and/or planned cesarean section.

History and exam

Key diagnostic factors.

- buttocks or feet as the presenting part

- fetal head under costal margin

- fetal heartbeat above the maternal umbilicus

Other diagnostic factors

- subcostal tenderness

- pelvic or bladder pain

Risk factors

- premature fetus

- small for gestational age fetus

- nulliparity

- fetal congenital anomalies

- previous breech delivery

- uterine abnormalities

- abnormal amniotic fluid volume

- placental abnormalities

- female fetus

Diagnostic investigations

1st investigations to order.

- transabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound

Treatment algorithm

<37 weeks' gestation, ≥37 weeks' gestation not in labor, ≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: no imminent delivery, ≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: imminent delivery, contributors, natasha nassar, phd.

Associate Professor

Menzies Centre for Health Policy

Sydney School of Public Health

University of Sydney

Disclosures

NN has received salary support from Australian National Health and a Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship; she is an author of a number of references cited in this topic.

Christine L. Roberts, MBBS, FAFPHM, DrPH

Research Director

Clinical and Population Health Division

Perinatal Medicine Group

Kolling Institute of Medical Research

CLR declares that she has no competing interests.

Jonathan Morris, MBChB, FRANZCOG, PhD

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Head of Department

JM declares that he has no competing interests.

Peer reviewers

John w. bachman, md.

Consultant in Family Medicine

Department of Family Medicine

Mayo Clinic

JWB declares that he has no competing interests.

Rhona Hughes, MBChB

Lead Obstetrician

Lothian Simpson Centre for Reproductive Health

The Royal Infirmary

RH declares that she has no competing interests.

Brian Peat, MD

Director of Obstetrics

Women's and Children's Hospital

North Adelaide

South Australia

BP declares that he has no competing interests.

Lelia Duley, MBChB

Professor of Obstetric Epidemiology

University of Leeds

Bradford Institute of Health Research

Temple Bank House

Bradford Royal Infirmary

LD declares that she has no competing interests.

Justus Hofmeyr, MD

Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

East London Private Hospital

East London

South Africa

JH is an author of a number of references cited in this topic.

Differentials

- Transverse lie

- Antenatal corticosteroids to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality

- Caesarean birth

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer

Help us improve BMJ Best Practice

Please complete all fields.

I have some feedback on:

We will respond to all feedback.

For any urgent enquiries please contact our customer services team who are ready to help with any problems.

Phone: +44 (0) 207 111 1105

Email: [email protected]

Your feedback has been submitted successfully.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is Breech?

When a fetus is delivered buttocks or feet first

- Types of Presentation

Risk Factors

Complications.

Breech concerns the position of the fetus before labor . Typically, the fetus comes out headfirst, but in a breech delivery, the buttocks or feet come out first. This type of delivery is risky for both the pregnant person and the fetus.

This article discusses the different types of breech presentations, risk factors that might make a breech presentation more likely, treatment options, and complications associated with a breech delivery.

Verywell / Jessica Olah

Types of Breech Presentation

During the last few weeks of pregnancy, a fetus usually rotates so that the head is positioned downward to come out of the vagina first. This is called the vertex position.

In a breech presentation, the fetus does not turn to lie in the correct position. Instead, the fetus’s buttocks or feet are positioned to come out of the vagina first.

At 28 weeks of gestation, approximately 20% of fetuses are in a breech position. However, the majority of these rotate to the proper vertex position. At full term, around 3%–4% of births are breech.

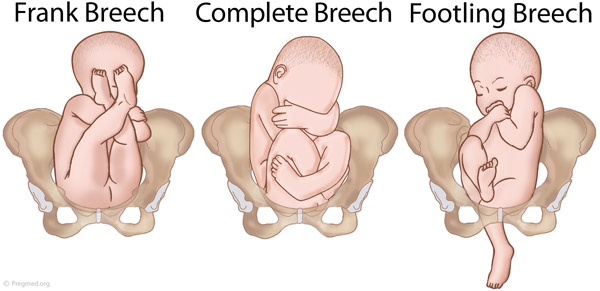

The different types of breech presentations include:

- Complete : The fetus’s knees are bent, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Frank : The fetus’s legs are stretched upward toward the head, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Footling : The fetus’s foot is showing first.

Signs of Breech

There are no specific symptoms associated with a breech presentation.

Diagnosing breech before the last few weeks of pregnancy is not helpful, since the fetus is likely to turn to the proper vertex position before 35 weeks gestation.

A healthcare provider may be able to tell which direction the fetus is facing by touching a pregnant person’s abdomen. However, an ultrasound examination is the best way to determine how the fetus is lying in the uterus.

Most breech presentations are not related to any specific risk factor. However, certain circumstances can increase the risk for breech presentation.

These can include:

- Previous pregnancies

- Multiple fetuses in the uterus

- An abnormally shaped uterus

- Uterine fibroids , which are noncancerous growths of the uterus that usually appear during the childbearing years

- Placenta previa, a condition in which the placenta covers the opening to the uterus

- Preterm labor or prematurity of the fetus

- Too much or too little amniotic fluid (the liquid that surrounds the fetus during pregnancy)

- Fetal congenital abnormalities

Most fetuses that are breech are born by cesarean delivery (cesarean section or C-section), a surgical procedure in which the baby is born through an incision in the pregnant person’s abdomen.

In rare instances, a healthcare provider may plan a vaginal birth of a breech fetus. However, there are more risks associated with this type of delivery than there are with cesarean delivery.

Before cesarean delivery, a healthcare provider might utilize the external cephalic version (ECV) procedure to turn the fetus so that the head is down and in the vertex position. This procedure involves pushing on the pregnant person’s belly to turn the fetus while viewing the maneuvers on an ultrasound. This can be an uncomfortable procedure, and it is usually done around 37 weeks gestation.

ECV reduces the risks associated with having a cesarean delivery. It is successful approximately 40%–60% of the time. The procedure cannot be done once a pregnant person is in active labor.

Complications related to ECV are low and include the placenta tearing away from the uterine lining, changes in the fetus’s heart rate, and preterm labor.

ECV is usually not recommended if the:

- Pregnant person is carrying more than one fetus

- Placenta is in the wrong place

- Healthcare provider has concerns about the health of the fetus

- Pregnant person has specific abnormalities of the reproductive system

Recommendations for Previous C-Sections

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that ECV can be considered if a person has had a previous cesarean delivery.

During a breech delivery, the umbilical cord might come out first and be pinched by the exiting fetus. This is called cord prolapse and puts the fetus at risk for decreased oxygen and blood flow. There’s also a risk that the fetus’s head or shoulders will get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis, leading to suffocation.

Complications associated with cesarean delivery include infection, bleeding, injury to other internal organs, and problems with future pregnancies.

A healthcare provider needs to weigh the risks and benefits of ECV, delivering a breech fetus vaginally, and cesarean delivery.

In a breech delivery, the fetus comes out buttocks or feet first rather than headfirst (vertex), the preferred and usual method. This type of delivery can be more dangerous than a vertex delivery and lead to complications. If your baby is in breech, your healthcare provider will likely recommend a C-section.

A Word From Verywell

Knowing that your baby is in the wrong position and that you may be facing a breech delivery can be extremely stressful. However, most fetuses turn to have their head down before a person goes into labor. It is not a cause for concern if your fetus is breech before 36 weeks. It is common for the fetus to move around in many different positions before that time.

At the end of your pregnancy, if your fetus is in a breech position, your healthcare provider can perform maneuvers to turn the fetus around. If these maneuvers are unsuccessful or not appropriate for your situation, cesarean delivery is most often recommended. Discussing all of these options in advance can help you feel prepared should you be faced with a breech delivery.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. If your baby is breech .

TeachMeObGyn. Breech presentation .

MedlinePlus. Breech birth .

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015 Apr 1;2015(4):CD000083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3

By Christine Zink, MD Dr. Zink is a board-certified emergency medicine physician with expertise in the wilderness and global medicine.

Breech presentation: diagnosis and management

Key messages.

- All women with a breech presentation should be offered an external cephalic version (ECV) from 37 weeks, if there are no contraindications.

- Elective caesarean section (ELCS) for a singleton breech at term has been shown to reduce perinatal and neonatal mortality rates.

- Planning for vaginal breech birth requires careful assessment of suitability criteria, contraindications and the ability of the service to provide experienced personnel.

In June 2023, we commenced a project to review and update the Maternity and Neonatal eHandbook guidelines, with a view to targeting completion in 2024. Please be aware that pending this review, some of the current guidelines may be out of date. In the meantime, we recommend that you also refer to more contemporaneous evidence.

Breech and external cephalic version

Breech presentation is when the fetus is lying longitudinally and its buttocks, foot or feet are presenting instead of its head.

Figure 1. Breech presentations

- Breech presentation occurs in three to four per cent of term deliveries and is more common in nulliparous women.

- External cephalic version (ECV) from 37 weeks has been shown to decrease the incidence of breech presentation at term and the subsequent elective caesarean section (ELCS) rate.

- Vaginal breech birth increases the risk of low Apgar scores and more serious short-term complications, but evidence has not shown an increase in long-term morbidity.

- Emergency caesarean section (EMCS) is needed in approximately 40 per cent of women planning a vaginal breech birth.

- 0.5/1000 with ELCS for breech >39 weeks gestation

- 2.0/1000 planned vaginal breech birth >39/40

- 1.0/1000 with planned cephalic birth.

- A reduction in planned vaginal breech birth followed publication of the Term Breech Trial (TBT) in 2001.

- Acquisition of skills necessary to manage breech presentation (for example, ECV) is important to optimise outcomes.

Clinical suspicion of breech presentation

- Abdominal palpation: if the presenting part is irregular and not ballotable or if the fetal head is ballotable at the fundus

- Pelvic examination: head not felt in the pelvis

- Cord prolapse

- Very thick meconium after rupture of membranes

- Fetal heart heard higher in the abdomen

In cases of extended breech, the breech may not be ballotable and the fetal heart may be heard in the same location as expected for a cephalic presentation.

If breech presentation is suspected, an ultrasound examination will confirm diagnosis.

Cord prolapse is an obstetric emergency. Urgent delivery is indicated after confirming gestation and fetal viability.

Diagnosis: preterm ≤36+6 weeks

- Breech presentation is a normal finding in preterm pregnancy.

- If diagnosed at the 35-36 week antenatal visit, refer the woman for ultrasound scan to enable assessment prior to ECV.

- Mode of birth in a breech preterm delivery depends on the clinical circumstances.

Diagnosis: ≥37+0 weeks

- determine type of breech presentation

- determine extension/flexion of fetal head

- locate position of placenta and exclude placenta praevia

- exclude fetal congenital abnormality

- calculate amniotic fluid index

- estimate fetal weight.

Practice points

- Offer ECV if there are no contraindications.

- If ECV is declined or unsuccessful, provide counselling on risks and benefits of a planned vaginal birth versus an ELCS.

- Inform the woman that there are fewer maternal complications with a successful vaginal birth, however the risk to the woman increases significantly if there is a need for an EMCS.

- Inform the woman that caesarean section increases the risk of complication in future pregnancies, including the risk of a repeat caesarean section and the risk of invasive placentation.

- If the woman chooses an ELCS, document consent and organise booking for 39 weeks gestation.

Information and decision making

Women with a breech presentation should have the opportunity to make informed decisions about their care and treatment, in partnership with the clinicians providing care.

Planning for birth requires careful assessment for risk of poor outcomes relating to planned vaginal breech birth. If any risk factors are identified, inform the woman that an ELCS is recommended due to increased perinatal risk.

Good communication between clinicians and women is essential. Treatment, care and information provided should:

- take into account women's individual needs and preferences

- be supported by evidence-based, written information tailored to the needs of the individual woman

- be culturally appropriate

- be accessible to women, their partners, support people and families

- take into account any specific needs, such as physical or cognitive disabilities or limitations to their ability to understand spoken or written English.

Documentation

The following should be documented in the woman's hospital medical record and (where applicable) in her hand-held medical record:

- discussion of risks and benefits of vaginal breech birth and ELCS

- discussion of the woman's questions about planned vaginal breech birth and ELCS

- discussion of ECV, if applicable

- consultation, referral and escalation

External cephalic version (ECV)

- ECV can be offered from 37 weeks gestation

- The woman must provide written consent prior to the procedure

- The success rate of ECV is 40-60 per cent

- Approximately one in 200 ECV attempts will lead to EMCS

- ECV should only be performed by a suitably trained, experienced clinician

- continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM)

- capability to perform an EMCS.

Contraindications

Table 1. Contraindications to ECV

Precautions

- Hypertension

- Oligohydramnios

- Nuchal cord

Escalate care to a consultant obstetrician if considering ECV in these circumstances.

- Perform a CTG prior to the procedure - continue until RANZCOG criteria for a normal antenatal CTG are met.

- 250 microg s/c, 30 minutes prior to the procedure.

- Administer Anti-D immunoglobulin if the woman is rhesus negative.

- Do not make more than four attempts at ECV, for a suggested maximum time of ten minutes in total.

- Undertake CTG monitoring post-procedure until RANZCOG criteria for a normal antenatal CTG are met.

Emergency management

Urgent delivery is indicated in the event of the following complications:

- abnormal CTG

- vaginal bleeding

- unexplained pain.

Initiate emergency response as per local guidelines.

Alternatives to ECV

There is a lack of evidence to support the use of moxibustion, acupuncture or postural techniques to achieve a vertex presentation after 35 weeks gestation.

Criteria for a planned vaginal breech birth

- Documented evidence of counselling regarding mode of birth

- Documentation of informed consent, including written consent from the woman

- Estimated fetal weight of 2500-4000g

- Flexed fetal head

- Emergency theatre facilities available on site

- Availability of suitably skilled healthcare professional

- Frank or complete breech presentation

- No previous caesarean section.

- Cord presentation

- Fetal growth restriction or macrosomia

- Any presentation other than a frank or complete breech

- Extension of the fetal head

- Fetal anomaly incompatible with vaginal delivery

- Clinically inadequate maternal pelvis

- Previous caesarean section

- Inability of the service to provide experienced personnel.

If an ELCS is booked

- Confirm presentation by ultrasound scan when a woman presents for ELCS.

- If fetal presentation is cephalic on admission for ELCS, plan ongoing management with the woman.

Intrapartum management

Fetal monitoring.

- Advise the woman that continuous EFM may lead to improved neonatal outcomes.

- Where continuous EFM is declined, perform intermittent EFM or intermittent auscultation, with conversion to EFM if an abnormality is detected.

- A fetal scalp electrode can be applied to the breech.

Position of the woman

- The optimal maternal position for birth is upright.

- Lithotomy may be appropriate, depending on the accoucheur's training and experience.

Pain relief

- Epidural analgesia may increase the risk of intervention with a vaginal breech birth.

- Epidural analgesia may impact on the woman's ability to push spontaneously in the second stage of labour.

Induction of labour (IOL)

See the IOL eHandbook page for more detail.

- IOL may be offered if clinical circumstances are favourable and the woman wishes to have a vaginal birth.

- Augmentation (in the absence of an epidural) should be avoided as adequate progress in the absence of augmentation may be the best indicator of feto-pelvic proportions.

The capacity to offer IOL will depend on clinician experience and availability and service capability.

First stage

- Manage with the same principles as a cephalic presentation.

- Labour should be expected to progress as for a cephalic presentation.

- If progress in the first stage is slow, consider a caesarean section.

- If an epidural is in situ and contractions are less than 4:10, consult with a senior obstetrician.

- Avoid routine amniotomy to avoid the risk of cord prolapse or cord compression.

Second stage

- Allow passive descent of the breech to the perineum prior to active pushing.

- If breech is not visible within one hour of passive descent, a caesarean section is normally recommended.

- Active second stage should be ½ hour for a multigravida and one hour for a primipara.

- All midwives and obstetricians should be familiar with the techniques and manoeuvres required to assist a vaginal breech birth.

- Ensure a consultant obstetrician is present for birth.

- Ensure a senior paediatric clinician is present for birth.

VIDEO: Maternity Training International - Vaginal Breech Birth

- Encouragement of maternal pushing (if at all) should not begin until the presenting part is visible.

- A hands-off approach is recommended.

- Significant cord compression is common once buttocks have passed the perineum.

- Timely intervention is recommended if there is slow progress once the umbilicus has delivered.

- Allow spontaneous birth of the trunk and limbs by maternal effort as breech extraction can cause extension of the arms and head.

- Grasp the fetus around the bony pelvic girdle, not soft tissue, to avoid trauma.

- Assist birth if there is a delay of more than five minutes from delivery of the buttocks to the head, or of more than three minutes from the umbilicus to the head.

- Signs that delivery should be expedited also include lack of tone or colour or sign of poor fetal condition.

- Ensure fetal back remains in the anterior position.

- Routine episiotomy not recommended.

- Lovset's manoeuvre for extended arms.

- Reverse Lovset's manoeuvre may be used to reduce nuchal arms.

- Supra-pubic pressure may aide flexion of the fetal head.

- Maricueau-Smellie-Veit manoeuvre or forceps may be used to deliver the after coming head.

Undiagnosed breech in labour

- This occurs in approximately 25 per cent of breech presentations.

- Management depends on the stage of labour when presenting.

- Assessment is required around increased complications, informed consent and suitability of skilled expertise.

- Do not routinely offer caesarean section to women in active second stage.

- If there is no senior obstetrician skilled in breech delivery, an EMCS is the preferred option.

- If time permits, a detailed ultrasound scan to estimate position of fetal neck and legs and estimated fetal weight should be made and the woman counselled.

Entrapment of the fetal head

This is an extreme emergency

This complication is often due to poor selection for vaginal breech birth.

- A vaginal examination (VE) should be performed to ensure that the cervix is fully dilated.

- If a lip of cervix is still evident try to push the cervix over the fetal head.

- If the fetal head has entered the pelvis, perform the Mauriceau-Smellie-Veit manoeuvre combined with suprapubic pressure from a second attendant in a direction that maintains flexion and descent of the fetal head.

- Rotate fetal body to a lateral position and apply suprapubic pressure to flex the fetal head; if unsuccessful consider alternative manoeuvres.

- Reassess cervical dilatation; if not fully dilated consider Duhrssen incision at 2, 10 and 6 o'clock.

- A caesarean section may be performed if the baby is still alive.

Neonatal management

- Paediatric review.

- Routine observations as per your local guidelines, recorded on a track and trigger chart.

- Observe for signs of jaundice.

- Observe for signs of tissue or nerve damage.

- Hip ultrasound scan to be performed at 6-12 weeks post birth to monitor for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). See Neonatal eHandbook - Developmental dysplasia of the hip .

More information

Audit and performance improvement.

All maternity services should have processes in place for:

- auditing clinical practice and outcomes

- providing feedback to clinicians on audit results

- addressing risks, if identified

- implementing change, if indicated.

Potential auditable standards are:

- number of women with a breech presentation offered ECV

- success rate of ECV

- ECV complications

- rate of planned vaginal breech birth

- breech birth outcomes for vaginal and caesarean birth.

For more information or assistance with auditing, please contact us via [email protected]

- Bue and Lauszus 2016, Moxibustion did not have an effect in a randomised clinical trial for version of breech position. Danish Medical Journal 63(2), A599

- Coulon et.al. 2014, Version of breech fetuses by moxibustion with acupuncture. Obstetrics and Gynecology 124(1), 32-39. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000303

- Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B 2012, Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD003928. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003928.pub3

- Evans J 2012, Essentially MIDIRS Understanding Physiological Breech Birth Volume 3. Number 2. February 2012

- Hoffmann J, Thomassen K, Stumpp P, Grothoff M, Engel C, Kahn T, et al. 2016, New MRI Criteria for Successful Vaginal Breech Delivery in Primiparae. PLoS ONE 11(8): e0161028. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0161028

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R 2012, Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD000051. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000051.pub2

- New South Wales Department of Health 2013, Maternity: Management of Breech Presentation HNELHD CG 13_01, NSW Government; 2013

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2017, External Cephalic Version and Reducing the Incidence of Term Breech Presentation. Green-top Guideline No. 20a . London: RCOG; 2017

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) 2016, Management of breech presentation at term , July 2016 C-Obs-11:

- The Royal Women's Hospital 2015, Management of Breech - Clinical Guideline

- Women's and Newborn Health Service, King Edward Memorial Hospital 2015, Complications of Pregnancy Breech Presentation

Abbreviations

Get in touch, version history.

First published: November 2018 Due for review: November 2021

Uncontrolled when downloaded

Related links.

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

- Fetal presentation before birth

The way a baby is positioned in the uterus just before birth can have a big effect on labor and delivery. This positioning is called fetal presentation.

Babies twist, stretch and tumble quite a bit during pregnancy. Before labor starts, however, they usually come to rest in a way that allows them to be delivered through the birth canal headfirst. This position is called cephalic presentation. But there are other ways a baby may settle just before labor begins.

Following are some of the possible ways a baby may be positioned at the end of pregnancy.

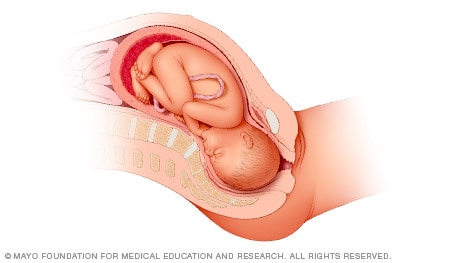

Head down, face down

When a baby is head down, face down, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput anterior position. This the most common position for a baby to be born in. With the face down and turned slightly to the side, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the birth canal. It is the easiest way for a baby to be born.

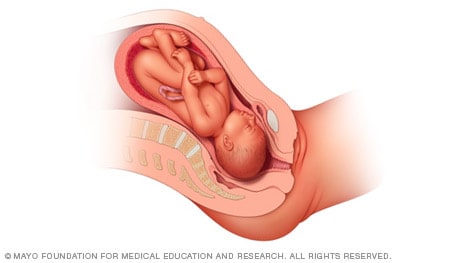

Head down, face up

When a baby is head down, face up, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput posterior position. In this position, it might be harder for a baby's head to go under the pubic bone during delivery. That can make labor take longer.

Most babies who begin labor in this position eventually turn to be face down. If that doesn't happen, and the second stage of labor is taking a long time, a member of the health care team may reach through the vagina to help the baby turn. This is called manual rotation.

In some cases, a baby can be born in the head-down, face-up position. Use of forceps or a vacuum device to help with delivery is more common when a baby is in this position than in the head-down, face-down position. In some cases, a C-section delivery may be needed.

Frank breech

When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a frank breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Most babies in a frank breech position are born by planned C-section.

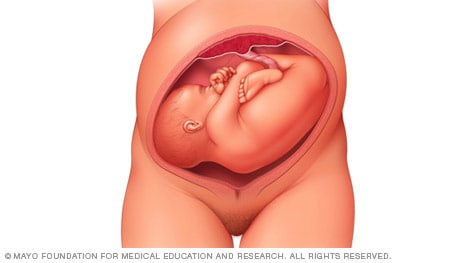

Complete and incomplete breech

A complete breech presentation, as shown below, is when the baby has both knees bent and both legs pulled close to the body. In an incomplete breech, one or both of the legs are not pulled close to the body, and one or both of the feet or knees are below the baby's buttocks. If a baby is in either of these positions, you might feel kicking in the lower part of your belly.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a complete or incomplete breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies in a complete or incomplete breech position are born by planned C-section.

When a baby is sideways — lying horizontal across the uterus, rather than vertical — it's called a transverse lie. In this position, the baby's back might be:

- Down, with the back facing the birth canal.

- Sideways, with one shoulder pointing toward the birth canal.

- Up, with the hands and feet facing the birth canal.

Although many babies are sideways early in pregnancy, few stay this way when labor begins.

If your baby is in a transverse lie during week 37 of your pregnancy, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of your health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a transverse lie, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies who are in a transverse lie are born by C-section.

If you're pregnant with twins and only the twin that's lower in the uterus is head down, as shown below, your health care provider may first deliver that baby vaginally.

Then, in some cases, your health care team may suggest delivering the second twin in the breech position. Or they may try to move the second twin into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

Your health care team may suggest delivery by C-section for the second twin if:

- An attempt to deliver the baby in the breech position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to have the baby delivered vaginally in the breech position.

- An attempt to move the baby into a head-down position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to move the baby to a head-down position.

In some cases, your health care team may advise that you have both twins delivered by C-section. That might happen if the lower twin is not head down, the second twin has low or high birth weight as compared to the first twin, or if preterm labor starts.

- Landon MB, et al., eds. Normal labor and delivery. In: Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Holcroft Argani C, et al. Occiput posterior position. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Frequently asked questions: If your baby is breech. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/if-your-baby-is-breech. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Hofmeyr GJ. Overview of breech presentation. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Strauss RA, et al. Transverse fetal lie. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Chasen ST, et al. Twin pregnancy: Labor and delivery. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Cohen R, et al. Is vaginal delivery of a breech second twin safe? A comparison between delivery of vertex and non-vertex second twins. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.2005569.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 31, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Obstetricks

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 3rd trimester pregnancy

- Fetal development: The 3rd trimester

- Overdue pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

- Prenatal care: 3rd trimester

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Obstet Gynaecol India

- v.62(4); 2012 Aug

Delivery in Breech Presentation: The Decision Making

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pt.J.N.M. Medical College and Dr. B.R.A.M Hospital, E-8, Shankar Nagar, Raipur, Chhattisgarh 492001 India

Nalini Mishra

Rajni dewangan.

To optimize the fetomaternal oucome using different modes of delivery in breech presentation.

Materials and Methods

265 women with different parity and gestational age having singleton breech were studied during Jan 2007 to Sep 2009 at Pt. J.N.M. Medical College and associated Dr. B.R.A.M. Hospital Raipur Chhattisgarh and were assigned to either planned or emergency cesarean section or trial of vaginal delivery after counseling. Fetomaternal outcome was compared in various modes of delivery.

Observations

Incidence of breech presentation was 2.1 %, prematurity was the most common cause. 113 (42.6 %) women delivered vaginally. 54 (20.4 %) were planned for cesarean section. Emergency cesarean section was done in 98 (37 %). Although perinatal morbidity and mortality was lower in caesarean section group as compared to vaginal delivery group, but the difference became statistically insignificant after adjustment for confounding factors. ( p = 0.14)

In view of insignificant difference in the fetomaternal outcome balanced decision about mode of delivery on a case by case basis will go a long way in improving both foetal and maternal outcome. Regular drill and conduct of vaginal breech delivery should be pursued in all maternity hospitals.

Introduction

About 3–4 % of all pregnancies have breech presentation at term. The management of term breech is highly controversial and varies among different institutions and even among different clinicians in the same institution. The decision to perform cesarean delivery is often based on personal experience or a fear of litigation.

From the historical perspective, vaginal delivery of the persistent breech presentation had been the tradition since the first century a . d . Intended vaginal delivery is the common practice in most developing countries. Probably, the obstetricians are also more conversant in the technique of assisted breech delivery. This protocol received a major setback in the year 2000 when Lancet published the results of the Term Breech Trial by Mary E Hannah, which clearly concluded that planned cesarean section is better than planned vaginal birth for the term fetus with breech presentation in terms of neonatal outcome [ 1 ]. Serious maternal complication was similar between the two groups. It evoked stinging criticism, itemizing the methodological errors and unsupportable conclusions [ 2 ]. There is an urgent need to evaluate it in context of the resource poor countries before accepting it as the “Last word.” An overall policy of planned cesarean section in all term breeches would prevent complications of vaginal delivery because there would be no vaginal breech delivery. This might result in shifting of the contemporary art of conducting such delivery to the shelves of medical history. On further analysis of the Term Breech Trial, an important interaction involved a country’s perinatal mortality rate. In the countries with a low perinatal mortality rate, planned cesarean section had much greater benefits for the infant, whereas in countries where the perinatal mortality rate is high, the same benefits were much lower than the entire group as a whole. As many as 39 additional cesareans might be needed to avoid one serious infant morbidity or death in comparison to as few as seven additional cesarean sections in countries with a low perinatal mortality rate. This important observation is much more pertinent in countries with limited facilities for cesarean section.

Unfortunately, the number of obstetricians able to conduct the vaginal breech delivery is declining quite fast. If the trend continues, what will happen when a woman with breech presentation at term gets admitted in advanced labor at a center where cesarean section cannot be performed urgently and the obstetrician present has never conducted a vaginal breech delivery? It will indeed be a very sad day for our specialty.

As the controversy continues, repeated evaluations and reviews of management in this subset of women are needed. The present study was conducted with an objective to optimize the perinatal outcome, while keeping the art of conducting and training vaginal breech deliveries alive.

A total of 265 women with singleton breech presentation with >28 weeks gestational age were included in the present study during the period from Jan 2007 to Sep. 2009 (33 months).

On admission, the demographic profile of the women, as well as a detailed menstrual and obstetric history, was noted. General, systemic, and obstetric examination was carried out. All women were subjected to a routine investigation and obstetric ultrasonography and afterward, they were assigned to either cesarean section (planned/emergency) or vaginal delivery on the basis of the obstetric examination (clinical and sonographical) and the presence of complicating factors. Women having standard indications of cesarean section in breech like fetopelvic disproportion, hyperextension of the head, footling presentation, and associated complications (medical or obstetric) were assigned to the planned cesarean section group, whereas the remaining women having term breech were given a trial of vaginal breech delivery. The plan of delivery for the both term and preterm breech was discussed with the women and their attendants because of limited beds in the intensive neonatal care unit as well as probable course and complication of vaginal delivery. A trial of vaginal delivery was given to those who consented to it.

Regular drills of vaginal breech delivery are conducted in the department. During a trial of vaginal delivery, monitoring of fetal heart rate and progress of labor was done. Assisted breech delivery was the method of choice, maintaining a principle of noninterference till the delivery of the scapula. The delivery of the extended arms was accomplished by Lovset’s method, whereas the delivery of the aftercoming head was conducted by the Burns Marshall Method or Mauriceau Smellie Veit maneuver. After delivery, the baby was attended by the pediatrician and the Apgar Score at 1 and 5 min was noted and the baby was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit if needed.

If fetal distress and arrest of progress in labor were suspected, the women were taken for emergency cesarean section. All the mothers and newborns were followed up for 7 days in the postnatal period. Data regarding the fetomaternal outcome were analyzed. Comparisons were made in terms of morbidity and mortality between groups of mothers and infants stratified by the mode of delivery.

The incidence of breech presentation in the present study was 2.1 %. It varies from 3 to 4 % in various studies [ 3 – 8 ]. A majority of the women were unbooked (55.5 %) and nulliparous (40.4 %). 77.3 % women were having term pregnancy (Table 1 ).

Table 1

Demographic profile ( n = 265)

Overall, 113 (42.6 %) women delivered vaginally, a majority of these were term. Planned cesarean section was done in 54 (20.4 %) for indications shown in Table 2 . Since this is the largest teaching hospital in the state with a greater number of referrals, a majority of unbooked women get admitted in labor and therefore could not be assigned the mode of delivery before hand. Emergency cesarean section had to be resorted to in 98 (37 %) women for various indications. A comparatively larger number of women in our study delivered vaginally as compared to the Term Breech Trial (33.2 %) [ 1 ], and the difference was alarming from the largest series containing 10,0730 women with only 4.9 % delivering vaginally [ 6 ]. As we have a very limited neonatal intensive care unit, we motivated women with low birth weight babies to deliver vaginally, but only after obtaining due consent for the same. A large number of vaginal births provided us with the opportunity to train our residents to conduct the vaginal breech delivery and to avoid cesarean section, thereby reducing operative burden upon the already over-worked obstetrics units. It also prevented uterine scar in a woman whose dwindling chances of hospital delivery in the next pregnancy could have compromised her obstetric future.

Table 2

Mode of delivery (N-265)

The incidence of overall neonatal morbidity was 3.4 % (Table 3 ), out of which 2.3 % was present in the vaginal delivery group, but this subgroup was constituted mainly by preterm babies (5 out of 9). Damage to soft tissue was sustained equally by the preterm infants of both the vaginal and cesarean groups (2 each). Such damage can be attributed to the fact that delivering the infants even by cesarean section is essentially the process of breech extraction. None of the injuries were life threatening.

Table 3

Neonatal morbidity in relation to different modes of delivery (N-265)

p value of preterm vaginal versus preterm cesarean section = 0.08 (nonsignificant)

Table 4 shows the overall incidence of perinatal mortality in the present study; it is 51 (19.2 %), out of which 40 (15.8 %) were found in the vaginal delivery group with only 13 (4.9 %) term and 27 (10.9 %) preterm deliveries. Only one (0.4 %) fatality was found in the planned cesarean section group in contrast to 10 (3.9 %) in the emergency cesarean section group. Perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality, and neonatal morbidity were significantly lower for the planned cesarean section group than for the planned vaginal birth group as reported by the Term Breech Trial and others [ 1 , 6 , 8 – 10 ]. In our study also, the perinatal mortality seems to be significantly higher in the vaginal delivery group, but since the primary objective of the study was to see the effect of mode of delivery on perinatal outcome, we have reassessed the perinatal mortality after excluding 24 cases of women admitted with intrauterine fetal demise (which also included 11 with congenital malformation). The adjusted number of 16 (6 %) is not significantly greater than the 11 (4.2 %) in the cesarean section group.

Table 4

Perinatal mortality in correlation with different modes of delivery ( n = 265)

p value (after excluding intrauterine demised) of vaginal versus cesarean section = 0.24 (nonsignificant)

Prematurity was the largest factor contributing to perinatal mortality. After excluding 31 (11.7 %) preterm births, the statistical difference between the term breech delivery in the vaginal delivery versus the cesarean section was not significant ( p = 0.14), although definitely higher for the vaginal group. The planned cesarean group at term pregnancy had a significantly better perinatal outcome ( p = 0.001), but the emergency cesarean section group did not prove to have the same advantage.

There was no maternal death in either group. Maternal morbidity in the cesarean section group was 3.4 % and in the vaginal group, it was 4.2 %. The difference was not significant statistically ( p = 0.5).

Table 5 depicts the comparable data of various studies after the Term Breech trial and shows a gradually increasing trend toward vaginal breech delivery, although almost universally concluding planned cesarean section to be better for the perinatal outcome. Our study is also in accordance with them, but the opportunity to plan the mode of delivery before labor is not provided to the obstetrician in a referral hospital like ours, and emergency cesarean section yielded comparable results in terms of perinatal outcome, a point also made by others [ 7 , 11 , 12 ]. We therefore recommend a very balanced decision regarding the mode of delivery in the tertiary centers of developing countries.

Table 5

Comparison of fetomaternal outcomes in different studies

When assisted vaginal breech delivery is accomplished after proper selection and counseling for women with breech presentation, cesarean section in preterm as well as term pregnancy can be avoided because the difference in terms of perinatal mortality and morbidity rates is not significant statistically between the vaginal and overall cesarean section groups after adjustment for confounding factors like prematurity and intrauterine fetal demise. Planned cesarean section is undoubtedly better. In countries where the majority of cesarean sections for breech presentation are done in emergency, a trial of vaginal delivery yields comparable results. Therefore, it is concluded that the balanced decision about the mode of delivery on a case by case basis as well as conduct, training, and regular drills of assisted breech delivery will go a long way to optimize the outcome of breech presentation in countries like ours.

Complications and Management of Breech Presentation

Cite this chapter.

- Joseph V. Collea 7 , 8

75 Accesses

1 Citations

The increased risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with vaginal delivery of the fetus in breech presentation has attracted the attention of obstetricians and midwives for centuries. From the Dark Ages to well into the nineteenth century, the perinatal morbidity and mortality from birth anoxia, injuries, and congenital malformations instilled in the superstitious and the uneducated the belief that breech presentation was an evil omen. 1 Primitive African tribes believed that breech presentation foretold the death of the child’s parents, 2 while noble attendants to the crowned heads of Europe whispered in birthing rooms that “children brought forth by their feet are cursed—they are born as monsters, crippled in mind and body, and destined to bring misfortune into the world. It would be better if they were not born.” 3

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Speert, H., 1958, Essays in Eponymy, Obstetric and Gynecologic Milestones , Macmillan, New York.

Google Scholar

Cianfrani, T., 1960, A Short History of Obstetrics and Gynecology , Charles C Thomas, Springfield, Ill.

Marx, R., 1949, The birth of an emperor, Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 89 :366.

DeLee, J. B., 1939, Year Book of Obstetrics and Gynecology , Year Book Medical Publishers, Chicago, Ill.

Hollick, F., 1848, The Matrons Manual of Midwifery and the Diseases of Women during Pregnancy , The American News Company, New York.

Piper, E. B., and Bachman, C., 1929, The prevention of fetal injuries in breech delivery, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 92 :217.

Article Google Scholar

Moore, W. T., and Steptoe, P. P., 1943, The experience of the Johns Hopkins Hospital with breech presentation: An analysis of 1,444 cases, South. Med. J. 36 :295.

Hall, J. E., and Kohl, S., 1956, Breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 72 :977.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Todd, W. D., and Steer, C. M., 1963, Term breech: Review of 1,006 term breech deliveries, Obstet. Gynecol. 22 :583.

Morgan, H. S., and Kane, S. H., 1964, An analysis of 16,327 breech births,/. Am. Med. Assoc. 187 :262.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hall, J. E., Kohl, S. G., O’Brien, F., et al. , 1965, Breech presentation and perinatal mortality, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 91 :655.

Morley, G. W., 1967, Breech presentation-A 15-year review, Obstet. Gynecol. 30 :745.

Neilson, D. R., 1970, Management of the large breech infant, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 107 :345.

Diddle, A. W., 1972, A study of 695 breech deliveries, Med. Times 100 :76.

Collea, J. V., Rabin, S. C, and Quilligan, E. J., Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , manuscript in preparation.

Vartan, C. K., 1940, Cause of breech presentation, Lancet 1 :595.

Weisman, A. I., 1944, An antepartum study of fetal polarity and rotation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 48 :550.

Vartan, C. K., 1945, The behavior of the fetus in utero, with special reference to the incidence of breech presentation at term,/. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Common. 52 :417.

Tompkins, P., 1946, An inquiry into the causes of breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 51 :595.

Stevenson, C. S., 1950, The principal cause of breech presentation in single term pregnancies, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 60 :41.

Collea, J. V., Benedetti, T., Hanson, V., et al. , Twin gestation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. , manuscript in preparation.

Braun, F. H. T., Jones, K. L., and Smith, D. W., 1975, Breech presentation as an indicator of fetal abnormality, J. Pediatr. 86 :419.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Brenner, W. E., Bruce, R. D., and Hendricks, C. H., 1974, The characteristics and perils of breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 118 :700.

Robinson, G. W., 1968, Birth characteristics of children with congenital dislocation of the hip, Am. J. Epidemiol. 87 :275.

Axelrod, F. B., Leistner, H. L., and Porges, R. F., 1974, Breech presentation among infants with familial dysautonomia, J. Pediatr. 84 :107.

Stevenson, C. S., 1949, X-ray visualization of the placenta: Experiences with soft tissue and cystographic techniques in the diagnosis of placenta previa, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 58 :15.

Johnson, C. E., 1970, Breech presentation at term, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 106 :865.

Stein, I. F., 1941, Deflexion attitudes in breech presentation, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 117 :1430.

Saling, E., and Müller-Holve, W., 1975, External cephalic version under tocolysis, J. Perinat. Med. 3 :115.

Patterson, S. P., Mulliniks, R. C, and Schreier, P. C, 1967, Breech presentation in the primigravida, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 98 :404.

Fischer-Rasmussen, W., and Trolle, D., 1967, Abdominal versus vaginal delivery in breech presentation, Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 46 :69.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Potter, E. L., 1940, Fetal and neonatal deaths, a Statistical analysis of 2,000 autopsies, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 115 :996.

Potter, M. G., Heaton, C. E., and Douglas, G. W., 1960, Intrinsic fetal risk in breech delivery, Obstet. Gynecol. 15 :158.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kian, L. S., 1963, Breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 86 :1050.

Eliot, B. W., and Hill, J. G., 1972, Method of breech management incorporating use of fetal blood sampling, Br. Med. J. 4 :703.

Wheeler, T., and Greene, K., 1975, Fetal heart rate monitoring during breech delivery, Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 82 :208.

Teteris, N. J., Botschner, A. W., Ullery, J. C., et al. , 1970, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 107 :762.

Goethals, T. R., 1940, Management of breech delivery, Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 70 :620.

Holland, E., 1922, Cranial stress in the fetus during labor and on the effects of excessive stress on the intracranial contents with an analysis of eighty-one cases of torn tentorium cerebelli and subdural cerebral hemorrhage, J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Emp. 29 :549.

Rubin, A., and Grimm, G., 1963, Results in breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 86 :1048.

Gold, E. M., Clyman, M. J., Wallace, H. M., et al. , 1953, Obstetric factors in birth injury, Obstet. Gynecol. 1 :43.

Ralis, Z. A., 1968, Trauma to newborn babies during breech delivery. Part I. Visceral organs and locomotor system, M.D. thesis, Faculty of Pediatrics, Charles University, Prague.

Ralis, Z. A., 1975, Birth trauma to muscles in babies born by breech delivery and its possible fatal consequences, Arch. Dis. Child. 50 :4.

Ward, S. V., and Sellers, T. B., 1950, Controversial issues in breech presentation, South. Med. J. 43 :879.

Tank, E. S., Davis, R., Holt, J. F., et al. , 1971, Mechanism of trauma during breech delivery, Obstet. Gynecol. 38 :761.

Tan, K. L., 1973, Brachial palsy, J . Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Commonw. 80 :60.

Byers, R. K., 1975, Spinal-cord injuries during birth, Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 17 :103.

Brans, Y. W., and Cassady, G., 1975, Neonatal spinal cord injuries, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 123 :918.

Wilcox, H. L., 1949, The attitude of the fetus in breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 58 :478.

Brakemann, O., 1936, Haltung und Konfiguration des Kindlichen Kopfes bei der Beckenendlage, Berurtsch. Gynaekol. 112 :154.

Lazar, M. R., and Salvaggio, A. T., 1959, Hyperextension of the fetal head in breech presentation, Obstet. Gynecol. 14 :198.

Caterini, H., Langer, A., Sama, J. C, et al. , 1975, Fetal risk in hyperextension of the fetal head in breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 123 :632.

Bhagwanani, S. G., Price, H. V., Laurence, K. M., et al. , 1973, Risks and prevention of cervical cord injury in the management of breech presentation with hyperextension of the fetal head, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 115 :1159.

Towbin, A., 1964, Spinal cord and brain stem injury at birth, Arch. Pathol. 77 :620.

Towbin, A., 1970, Central nervous system damage in the human fetus and newborn infant, Am.]. Dis. Child. 119 :529.

CAS Google Scholar

Evrard, J. R., and Hilrich, N., 1952, Hyperextension of the head in breech presen-tation, J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Emp. 59 :244.

Daugherty, C. M., Mickey, L. J., and Moore, J. T., 1953, Hyperextension of the fetal head in breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 66 :75.

Deacon, A. L., 1951, Hyperextension of the head in breech presentation, J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Emp. 58 :300.

Reis, R. A., and DeCosta, E. J., 1950, Hyperrotation and deflexion of the head in breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 60 :637.

Taylor, J. C, 1948, Breech presentation with hyperextension of the neck and intrauterine dislocation of cervical vertebrae, Obstet. Gynecol. 56 :381.

Minogue, M., 1974, Vaginal breech delivery in multiparae, J. Ir. Med. Assoc. 67 :117.

MacArthur, J. L., 1964, Reduction of the hazards of breech presentation by external cephalic version, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 88 :302.

Bock, J. E., 1969, The influence of prophylactic external cephalic version on the incidence of breech delivery, Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 48 :215.

Ranney, B., 1973, The gentle art of external cephalic version, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 116 :239.

Hibbard, L. T., and Schumann, W. R., 1973, Prophylactic external cephalic version in an obstetric practice, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 116 :511.

Ellis, R., 1968, External cephalic version under anesthesia, J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Commonw. 75 :865.

Marcus, R. G., Crewe-Brown, H., Krawitz, S., et al. , 1975, Feto-maternal hemorrhage following successful and unsuccessful attempts at external cephalic version, Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 82 :578.

Colcher, A. E., and Sussman, W., 1944, A practical technique for roentgen pelvimetry with a new positioning, Am. J. Roentgenol. 51 :207.

Eastman, N.J., 1948, Pelvic mensuration: A study in the perpetuation of error, Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 3 :301.

Russell, J. G. B., and Richards, B., 1971, A review of pelvimetry data, Br. J. Radiol. 44 :780.

Rovinsky, J. J., Miller, J. A., and Kaplan, S., 1973, Management of breech presentation at term, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 115 :497.

Joyce, D. N., Giwa-Osagie, F., and Stevenson, G. W., 1975, Role of pelvimetry in active management of labour, Br. Med. J. 4 :505.

Wolter, D. F., 1976, Patterns of management with breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 125 :733.

Harris, J. M., and Nissim, J. A., 1959, To do or not to do a cesarean section,/. Am. Med. Assoc. 169 :570.

Zatuchni, G. I., and Andros, G. J., 1967, Prognostic index for vaginal delivery in breech presentation at term, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 98 :854.

Schifrin, B. S., 1974, The case against pelvimetry, Contemp. Obstet. Gynecol. 4:77.

Kaupilla, O., 1975, The perinatal mortality in breech deliveries and observations on affecting factors, Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 39 .

Beisher, N. A., 1966, Pelvic contracture in breech presentation,/. Obstet, Gynaecol. Br. Commonw. 73 :421.

Milner, R. D. G., 1975, Neonatal mortality of breech deliveries with and without forceps to the after-coming head, Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 82 :783.

Reddin, P. C, 1974, Changing management of breech presentation, Missouri Med. 71 :584.

Wright, R. C, 1959, Reduction of perinatal mortality and morbidity in breech delivery through routine use of cesarean section, Obstet. Gynecol. 14 :758.

Lanka, L. D., and Nelson, H. B., 1969, Breech presentation with low fetal mortality — A comparative study, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 104 :879.

Smith, R. S., and Oldham, R. R., 1970, Breech delivery, Obstet. Gynecol. 36 :151.

Collea, J. V., Weghorst, G. R., and Paul, R. H., 1974, Singleton breech presentation-One year’s experience, in: Contributions to Gynecology and Obstetrics , Vol. 3 (G. P. Mandruzzato and P. G. Keller, eds.), S. Karger, Basle.

Collea, J. V., Rabin, S. C., Weghorst, G. R., et al. , 1978, The randomized management of term frank breech presentation: Vaginal delivery vs. cesarean section, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 131 :186.

Collea, J. V., Rabin, S. C, and Quilligan, E. J., The role of cesarean section in the management of breech presentation, manuscript in preparation.

Stewart, A. L., Turcan, D. M., Rawlings, G., et al. , 1977, Prognosis for infants weighing 1,000 grams or less at birth, Arch. Dis. Child. 52 :97.

Stewart, A. L., 1977, Follow-up of preterm infants, in: Preterm Labor: Proceedings of the 5th Study Group , Royal College of Ob-Gyn, London.

Zuspan, F. R., 1978, Problems encountered in the treatment of pregnancy-induced hypertension, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 131 :591.

Kubli, F., Boos, W., and Ruutgers, H., 1976, Cesarean section in the management of singleton breech presentation, 5th European Congress of Perinatal Medicine, Uppsala, Sweden.

Neimand, K. M., and Rosenthal, A. H., 1965, Oxytocin in breech presentation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 93 :230.

Bowen-Simpkins, P., and Fergusson, I. L. C., 1974, Lumbar epidural block and the breech presentation, Br. J. Anaesth. 46 :420.

Crawford, J. S., 1975, Lumbar epidural analgesia for the singleton breech presentation, Anesthesia 30 :119.

Pearse, W. H., and Danforth, D. N., 1977, Dystocia due to abnormal fetopelvic relations, in: Obstetrics and Gynecology , 3rd ed. (D. N. Danford, ed.), Harper & Row, Hagerstown, Maryland.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, D.C., 20007, USA

Joseph V. Collea

Department of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Columbia Hospital for Woman, Washington, D.C., 20037, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Aubrey Milunsky MB.B.Ch., M.R.C.P., D.C.H. & Emanuel A. Friedman M.D. &

Computational Mechanics Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Aubrey Milunsky MB.B.Ch., M.R.C.P., D.C.H.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Beth Israel Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Emanuel A. Friedman M.D.

University of California, San Diego, USA

Louis Gluck M.D.

School of Medicine, La Jolla, California, USA

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1981 Aubrey Milunsky, Emanuel A. Friedman, and Louis Gluck

About this chapter

Collea, J.V. (1981). Complications and Management of Breech Presentation. In: Milunsky, A., Friedman, E.A., Gluck, L. (eds) Advances in Perinatal Medicine. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-4451-4_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-4451-4_3

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4757-4453-8

Online ISBN : 978-1-4757-4451-4

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Make a “Good” Presentation “Great”

- Guy Kawasaki

Remember: Less is more.

A strong presentation is so much more than information pasted onto a series of slides with fancy backgrounds. Whether you’re pitching an idea, reporting market research, or sharing something else, a great presentation can give you a competitive advantage, and be a powerful tool when aiming to persuade, educate, or inspire others. Here are some unique elements that make a presentation stand out.

- Fonts: Sans Serif fonts such as Helvetica or Arial are preferred for their clean lines, which make them easy to digest at various sizes and distances. Limit the number of font styles to two: one for headings and another for body text, to avoid visual confusion or distractions.

- Colors: Colors can evoke emotions and highlight critical points, but their overuse can lead to a cluttered and confusing presentation. A limited palette of two to three main colors, complemented by a simple background, can help you draw attention to key elements without overwhelming the audience.

- Pictures: Pictures can communicate complex ideas quickly and memorably but choosing the right images is key. Images or pictures should be big (perhaps 20-25% of the page), bold, and have a clear purpose that complements the slide’s text.

- Layout: Don’t overcrowd your slides with too much information. When in doubt, adhere to the principle of simplicity, and aim for a clean and uncluttered layout with plenty of white space around text and images. Think phrases and bullets, not sentences.

As an intern or early career professional, chances are that you’ll be tasked with making or giving a presentation in the near future. Whether you’re pitching an idea, reporting market research, or sharing something else, a great presentation can give you a competitive advantage, and be a powerful tool when aiming to persuade, educate, or inspire others.

- Guy Kawasaki is the chief evangelist at Canva and was the former chief evangelist at Apple. Guy is the author of 16 books including Think Remarkable : 9 Paths to Transform Your Life and Make a Difference.

Partner Center

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Aug 11, 2016 • Download as PPTX, PDF •. 231 likes • 106,865 views. O. obgymgmcri. Abnormalities of labour (breech) Healthcare. 1 of 35. Download now. Breech presentation - Download as a PDF or view online for free.

Some key points: - Breech presentation is when the buttocks or lower limbs present first. It occurs in 3.5% of term deliveries and up to 25% of preterm deliveries. - Types include complete breech, frank breech, and footling breech. Diagnosis is made through inspection, palpation, auscultation, and ultrasound.

Download now. Breech Presentation. Aims and Objectives . Incidence 3-4% of. Causes / Risk. External Cephalic Version . Diagnosing a Breech . Types of Breech. Vaginal Examination extended.

Breech presentation occurs when the fetus lies longitudinally with the pelvic or podalic pole presenting at the birth canal instead of the head. It has an incidence of 3-15% depending on gestational age. There are various types of breech including complete, frank, and footling. Breech delivery can be managed through external cephalic version ...

DEFINITIO N Breech Presentation is the Presentation in which the Fetus in a longitudinal lie with the buttocks or feets closet to the cervix . 7. INCIDENC E *The percentage of breech delivery decrease with advancing gestational age from 22-25% of birth prior to 28 weeks. *3-4% of fetus present by breech at term *5% at 34 weeks , usually 3 in ...

Download now. Breech presentation. 1. BREECH PRESENTATION Dr Amit Kumar Shrestha MDGP Second Year Resident ( NAMS) Bharatpur Hospital Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2073-12-31. 2. -In breech presentation, the lie is longitudinal and the podalic pole presents at the pelvic brim. -It is the most common malpresentation.

Breech presentation refers to the baby presenting for delivery with the buttocks or feet first rather than head. Associated with increased morbidity and mortality for the mother in terms of emergency cesarean section and placenta previa; and for the baby in terms of preterm birth, small fetal size, congenital anomalies, and perinatal mortality.

Observational, usually retrospective, series have consistently favoured elective caesarean birth over vaginal breech delivery. A meta-analysis of 27 studies examining term breech birth, 5 which included 258 953 births between 1993 and 2014, suggested that elective caesarean section was associated with a two- to five-fold reduction in perinatal mortality when compared with vaginal breech ...

This pamphlet explains what a breech presentation is, the different types of breech presentation, discusses ECV and provides balanced information related to birth mode options along with visual representations of statistics comparing the perinatal mortality rate between cephalic vaginal birth, VBB and C/S. This pamphlet was also developed in ...

Epidemiology. Breech presentation occurs in 3% to 4% of all term pregnancies. A higher percentage of breech presentations occurs with less advanced gestational age. At 32 weeks, 7% of fetuses are breech, and 28 weeks or less, 25% are breech. Specifically, following one breech delivery, the recurrence rate for the second pregnancy was nearly 10% ...

At full term, around 3%-4% of births are breech. The different types of breech presentations include: Complete: The fetus's knees are bent, and the buttocks are presenting first. Frank: The fetus's legs are stretched upward toward the head, and the buttocks are presenting first. Footling: The fetus's foot is showing first.

Types of Breech Presentation. These options may include: External cephalic version (ECV): This procedure involves an atempt to manually turn the baby into a head-down position by applying pressure on the mother's abdomen. ECV is typically performed around 36-38 weeks of gestation and has a success rate of approximately 50%.

Breech and external cephalic version. Breech presentation is when the fetus is lying longitudinally and its buttocks, foot or feet are presenting instead of its head. Figure 1. Breech presentations. Breech presentation occurs in three to four per cent of term deliveries and is more common in nulliparous women.

Introduction. Breech presentation of the fetus in late pregnancy may result in prolonged or obstructed labour with resulting risks to both woman and fetus. Interventions to correct breech presentation (to cephalic) before labour and birth are important for the woman's and the baby's health. The aim of this review is to determine the most ...

This video discusses the types of breech presentation, the most common malpresentation, and how to identify them. The various maneuvers employed for breech v...

The most widely quoted study regarding the management of breech presentation at term is the 'Term Breech Trial'. Published in 2000, this large, international multicenter randomised clinical trial compared a policy of planned vaginal delivery with planned caesarean section for selected breech presentations.

Breech presentation occurs frequently among preterm babies in utero, however, most babies will spontaneously revert to a cephalic presentation. As a result approximately 3% of babies are in the breech position at term (Hickok DE et al, 1992). In clinical practice this presents challenges regarding mode of delivery

Frank breech. When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head.

Because breech presentations complicate only 3-5% of all deliveries, decreasing the cesarean delivery rate for breeches by 50% has minimal impact on the overall cesarean delivery rate. Hofmeyr from the Cochrane Database reviewed 6 randomized clinical trials of ECV versus no ECV at term. ECV was associated with significant reduction in breech ...

Incidence of breech presentation was 2.1 %, prematurity was the most common cause. 113 (42.6 %) women delivered vaginally. 54 (20.4 %) were planned for cesarean section. Emergency cesarean section was done in 98 (37 %). Although perinatal morbidity and mortality was lower in caesarean section group as compared to vaginal delivery group, but the ...

Abstract. The increased risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with vaginal delivery of the fetus in breech presentation has attracted the attention of obstetricians and midwives for centuries. From the Dark Ages to well into the nineteenth century, the perinatal morbidity and mortality from birth anoxia, injuries, and congenital ...

Types of breech presentations. Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada) — dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the MSD Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge.

A strong presentation is so much more than information pasted onto a series of slides with fancy backgrounds. Whether you're pitching an idea, reporting market research, or sharing something ...