An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Med

Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers

Ylona chun tie.

1 Nursing and Midwifery, College of Healthcare Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

Melanie Birks

Karen francis.

2 College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Australia, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Background:

Grounded theory is a well-known methodology employed in many research studies. Qualitative and quantitative data generation techniques can be used in a grounded theory study. Grounded theory sets out to discover or construct theory from data, systematically obtained and analysed using comparative analysis. While grounded theory is inherently flexible, it is a complex methodology. Thus, novice researchers strive to understand the discourse and the practical application of grounded theory concepts and processes.

The aim of this article is to provide a contemporary research framework suitable to inform a grounded theory study.

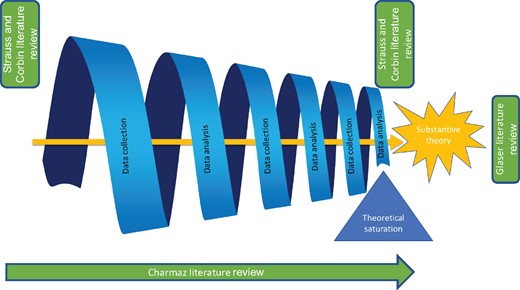

This article provides an overview of grounded theory illustrated through a graphic representation of the processes and methods employed in conducting research using this methodology. The framework is presented as a diagrammatic representation of a research design and acts as a visual guide for the novice grounded theory researcher.

Discussion:

As grounded theory is not a linear process, the framework illustrates the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and iterative and comparative actions involved. Each of the essential methods and processes that underpin grounded theory are defined in this article.

Conclusion:

Rather than an engagement in philosophical discussion or a debate of the different genres that can be used in grounded theory, this article illustrates how a framework for a research study design can be used to guide and inform the novice nurse researcher undertaking a study using grounded theory. Research findings and recommendations can contribute to policy or knowledge development, service provision and can reform thinking to initiate change in the substantive area of inquiry.

Introduction

The aim of all research is to advance, refine and expand a body of knowledge, establish facts and/or reach new conclusions using systematic inquiry and disciplined methods. 1 The research design is the plan or strategy researchers use to answer the research question, which is underpinned by philosophy, methodology and methods. 2 Birks 3 defines philosophy as ‘a view of the world encompassing the questions and mechanisms for finding answers that inform that view’ (p. 18). Researchers reflect their philosophical beliefs and interpretations of the world prior to commencing research. Methodology is the research design that shapes the selection of, and use of, particular data generation and analysis methods to answer the research question. 4 While a distinction between positivist research and interpretivist research occurs at the paradigm level, each methodology has explicit criteria for the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. 2 Grounded theory (GT) is a structured, yet flexible methodology. This methodology is appropriate when little is known about a phenomenon; the aim being to produce or construct an explanatory theory that uncovers a process inherent to the substantive area of inquiry. 5 – 7 One of the defining characteristics of GT is that it aims to generate theory that is grounded in the data. The following section provides an overview of GT – the history, main genres and essential methods and processes employed in the conduct of a GT study. This summary provides a foundation for a framework to demonstrate the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in a GT study as presented in the sections that follow.

Glaser and Strauss are recognised as the founders of grounded theory. Strauss was conversant in symbolic interactionism and Glaser in descriptive statistics. 8 – 10 Glaser and Strauss originally worked together in a study examining the experience of terminally ill patients who had differing knowledge of their health status. Some of these suspected they were dying and tried to confirm or disconfirm their suspicions. Others tried to understand by interpreting treatment by care providers and family members. Glaser and Strauss examined how the patients dealt with the knowledge they were dying and the reactions of healthcare staff caring for these patients. Throughout this collaboration, Glaser and Strauss questioned the appropriateness of using a scientific method of verification for this study. During this investigation, they developed the constant comparative method, a key element of grounded theory, while generating a theory of dying first described in Awareness of Dying (1965). The constant comparative method is deemed an original way of organising and analysing qualitative data.

Glaser and Strauss subsequently went on to write The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (1967). This seminal work explained how theory could be generated from data inductively. This process challenged the traditional method of testing or refining theory through deductive testing. Grounded theory provided an outlook that questioned the view of the time that quantitative methodology is the only valid, unbiased way to determine truths about the world. 11 Glaser and Strauss 5 challenged the belief that qualitative research lacked rigour and detailed the method of comparative analysis that enables the generation of theory. After publishing The Discovery of Grounded Theory , Strauss and Glaser went on to write independently, expressing divergent viewpoints in the application of grounded theory methods.

Glaser produced his book Theoretical Sensitivity (1978) and Strauss went on to publish Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists (1987). Strauss and Corbin’s 12 publication Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques resulted in a rebuttal by Glaser 13 over their application of grounded theory methods. However, philosophical perspectives have changed since Glaser’s positivist version and Strauss and Corbin’s post-positivism stance. 14 Grounded theory has since seen the emergence of additional philosophical perspectives that have influenced a change in methodological development over time. 15

Subsequent generations of grounded theorists have positioned themselves along a philosophical continuum, from Strauss and Corbin’s 12 theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism, through to Charmaz’s 16 constructivist perspective. However, understanding how to position oneself philosophically can challenge novice researchers. Birks and Mills 6 provide a contemporary understanding of GT in their book Grounded theory: A Practical Guide. These Australian researchers have written in a way that appeals to the novice researcher. It is the contemporary writing, the way Birks and Mills present a non-partisan approach to GT that support the novice researcher to understand the philosophical and methodological concepts integral in conducting research. The development of GT is important to understand prior to selecting an approach that aligns with the researcher’s philosophical position and the purpose of the research study. As the research progresses, seminal texts are referred back to time and again as understanding of concepts increases, much like the iterative processes inherent in the conduct of a GT study.

Genres: traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory

Grounded theory has several distinct methodological genres: traditional GT associated with Glaser; evolved GT associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke; and constructivist GT associated with Charmaz. 6 , 17 Each variant is an extension and development of the original GT by Glaser and Strauss. The first of these genres is known as traditional or classic GT. Glaser 18 acknowledged that the goal of traditional GT is to generate a conceptual theory that accounts for a pattern of behaviour that is relevant and problematic for those involved. The second genre, evolved GT, is founded on symbolic interactionism and stems from work associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke. Symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective that relies on the symbolic meaning people ascribe to the processes of social interaction. Symbolic interactionism addresses the subjective meaning people place on objects, behaviours or events based on what they believe is true. 19 , 20 Constructivist GT, the third genre developed and explicated by Charmaz, a symbolic interactionist, has its roots in constructivism. 8 , 16 Constructivist GT’s methodological underpinnings focus on how participants’ construct meaning in relation to the area of inquiry. 16 A constructivist co-constructs experience and meanings with participants. 21 While there are commonalities across all genres of GT, there are factors that distinguish differences between the approaches including the philosophical position of the researcher; the use of literature; and the approach to coding, analysis and theory development. Following on from Glaser and Strauss, several versions of GT have ensued.

Grounded theory represents both a method of inquiry and a resultant product of that inquiry. 7 , 22 Glaser and Holton 23 define GT as ‘a set of integrated conceptual hypotheses systematically generated to produce an inductive theory about a substantive area’ (p. 43). Strauss and Corbin 24 define GT as ‘theory that was derived from data, systematically gathered and analysed through the research process’ (p. 12). The researcher ‘begins with an area of study and allows the theory to emerge from the data’ (p. 12). Charmaz 16 defines GT as ‘a method of conducting qualitative research that focuses on creating conceptual frameworks or theories through building inductive analysis from the data’ (p. 187). However, Birks and Mills 6 refer to GT as a process by which theory is generated from the analysis of data. Theory is not discovered; rather, theory is constructed by the researcher who views the world through their own particular lens.

Research process

Before commencing any research study, the researcher must have a solid understanding of the research process. A well-developed outline of the study and an understanding of the important considerations in designing and undertaking a GT study are essential if the goals of the research are to be achieved. While it is important to have an understanding of how a methodology has developed, in order to move forward with research, a novice can align with a grounded theorist and follow an approach to GT. Using a framework to inform a research design can be a useful modus operandi.

The following section provides insight into the process of undertaking a GT research study. Figure 1 is a framework that summarises the interplay and movement between methods and processes that underpin the generation of a GT. As can be seen from this framework, and as detailed in the discussion that follows, the process of doing a GT research study is not linear, rather it is iterative and recursive.

Research design framework: summary of the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and processes.

Grounded theory research involves the meticulous application of specific methods and processes. Methods are ‘systematic modes, procedures or tools used for collection and analysis of data’. 25 While GT studies can commence with a variety of sampling techniques, many commence with purposive sampling, followed by concurrent data generation and/or collection and data analysis, through various stages of coding, undertaken in conjunction with constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling and memoing. Theoretical sampling is employed until theoretical saturation is reached. These methods and processes create an unfolding, iterative system of actions and interactions inherent in GT. 6 , 16 The methods interconnect and inform the recurrent elements in the research process as shown by the directional flow of the arrows and the encompassing brackets in Figure 1 . The framework denotes the process is both iterative and dynamic and is not one directional. Grounded theory methods are discussed in the following section.

Purposive sampling

As presented in Figure 1 , initial purposive sampling directs the collection and/or generation of data. Researchers purposively select participants and/or data sources that can answer the research question. 5 , 7 , 16 , 21 Concurrent data generation and/or data collection and analysis is fundamental to GT research design. 6 The researcher collects, codes and analyses this initial data before further data collection/generation is undertaken. Purposeful sampling provides the initial data that the researcher analyses. As will be discussed, theoretical sampling then commences from the codes and categories developed from the first data set. Theoretical sampling is used to identify and follow clues from the analysis, fill gaps, clarify uncertainties, check hunches and test interpretations as the study progresses.

Constant comparative analysis

Constant comparative analysis is an analytical process used in GT for coding and category development. This process commences with the first data generated or collected and pervades the research process as presented in Figure 1 . Incidents are identified in the data and coded. 6 The initial stage of analysis compares incident to incident in each code. Initial codes are then compared to other codes. Codes are then collapsed into categories. This process means the researcher will compare incidents in a category with previous incidents, in both the same and different categories. 5 Future codes are compared and categories are compared with other categories. New data is then compared with data obtained earlier during the analysis phases. This iterative process involves inductive and deductive thinking. 16 Inductive, deductive and abductive reasoning can also be used in data analysis. 26

Constant comparative analysis generates increasingly more abstract concepts and theories through inductive processes. 16 In addition, abduction, defined as ‘a form of reasoning that begins with an examination of the data and the formation of a number of hypotheses that are then proved or disproved during the process of analysis … aids inductive conceptualization’. 6 Theoretical sampling coupled with constant comparative analysis raises the conceptual levels of data analysis and directs ongoing data collection or generation. 6

The constant comparative technique is used to find consistencies and differences, with the aim of continually refining concepts and theoretically relevant categories. This continual comparative iterative process that encompasses GT research sets it apart from a purely descriptive analysis. 8

Memo writing is an analytic process considered essential ‘in ensuring quality in grounded theory’. 6 Stern 27 offers the analogy that if data are the building blocks of the developing theory, then memos are the ‘mortar’ (p. 119). Memos are the storehouse of ideas generated and documented through interacting with data. 28 Thus, memos are reflective interpretive pieces that build a historic audit trail to document ideas, events and the thought processes inherent in the research process and developing thinking of the analyst. 6 Memos provide detailed records of the researchers’ thoughts, feelings and intuitive contemplations. 6

Lempert 29 considers memo writing crucial as memos prompt researchers to analyse and code data and develop codes into categories early in the coding process. Memos detail why and how decisions made related to sampling, coding, collapsing of codes, making of new codes, separating codes, producing a category and identifying relationships abstracted to a higher level of analysis. 6 Thus, memos are informal analytic notes about the data and the theoretical connections between categories. 23 Memoing is an ongoing activity that builds intellectual assets, fosters analytic momentum and informs the GT findings. 6 , 10

Generating/collecting data

A hallmark of GT is concurrent data generation/collection and analysis. In GT, researchers may utilise both qualitative and quantitative data as espoused by Glaser’s dictum; ‘all is data’. 30 While interviews are a common method of generating data, data sources can include focus groups, questionnaires, surveys, transcripts, letters, government reports, documents, grey literature, music, artefacts, videos, blogs and memos. 9 Elicited data are produced by participants in response to, or directed by, the researcher whereas extant data includes data that is already available such as documents and published literature. 6 , 31 While this is one interpretation of how elicited data are generated, other approaches to grounded theory recognise the agency of participants in the co-construction of data with the researcher. The relationship the researcher has with the data, how it is generated and collected, will determine the value it contributes to the development of the final GT. 6 The significance of this relationship extends into data analysis conducted by the researcher through the various stages of coding.

Coding is an analytical process used to identify concepts, similarities and conceptual reoccurrences in data. Coding is the pivotal link between collecting or generating data and developing a theory that explains the data. Charmaz 10 posits,

codes rely on interaction between researchers and their data. Codes consist of short labels that we construct as we interact with the data. Something kinaesthetic occurs when we are coding; we are mentally and physically active in the process. (p. 5)

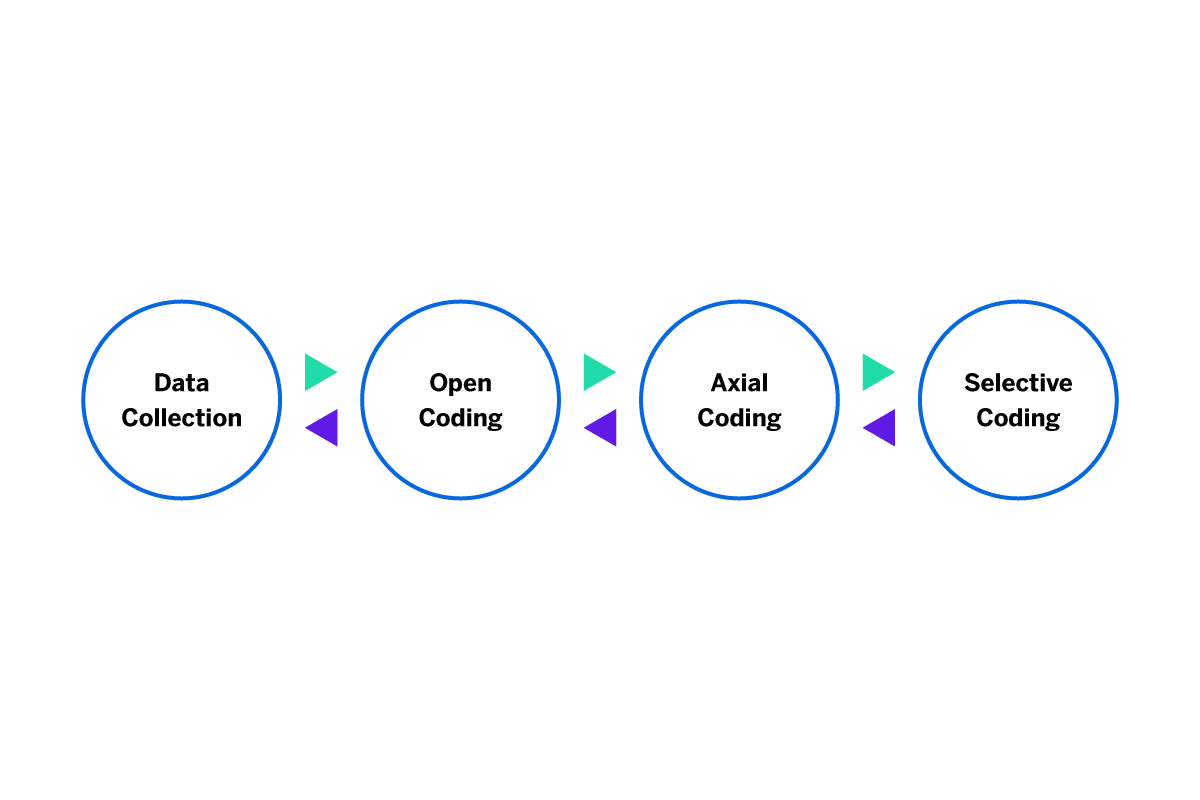

In GT, coding can be categorised into iterative phases. Traditional, evolved and constructivist GT genres use different terminology to explain each coding phase ( Table 1 ).

Comparison of coding terminology in traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory.

Adapted from Birks and Mills. 6

Coding terminology in evolved GT refers to open (a procedure for developing categories of information), axial (an advanced procedure for interconnecting the categories) and selective coding (procedure for building a storyline from core codes that connects the categories), producing a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 6 , 12 , 32 Constructivist grounded theorists refer to initial, focused and theoretical coding. 9 Birks and Mills 6 use the terms initial, intermediate and advanced coding that link to low, medium and high-level conceptual analysis and development. The coding terms devised by Birks and Mills 6 were used for Figure 1 ; however, these can be altered to reflect the coding terminology used in the respective GT genres selected by the researcher.

Initial coding

Initial coding of data is the preliminary step in GT data analysis. 6 , 9 The purpose of initial coding is to start the process of fracturing the data to compare incident to incident and to look for similarities and differences in beginning patterns in the data. In initial coding, the researcher inductively generates as many codes as possible from early data. 16 Important words or groups of words are identified and labelled. In GT, codes identify social and psychological processes and actions as opposed to themes. Charmaz 16 emphasises keeping codes as similar to the data as possible and advocates embedding actions in the codes in an iterative coding process. Saldaña 33 agrees that codes that denote action, which he calls process codes, can be used interchangeably with gerunds (verbs ending in ing ). In vivo codes are often verbatim quotes from the participants’ words and are often used as the labels to capture the participant’s words as representative of a broader concept or process in the data. 6 Table 1 reflects variation in the terminology of codes used by grounded theorists.

Initial coding categorises and assigns meaning to the data, comparing incident-to-incident, labelling beginning patterns and beginning to look for comparisons between the codes. During initial coding, it is important to ask ‘what is this data a study of’. 18 What does the data assume, ‘suggest’ or ‘pronounce’ and ‘from whose point of view’ does this data come, whom does it represent or whose thoughts are they?. 16 What collectively might it represent? The process of documenting reactions, emotions and related actions enables researchers to explore, challenge and intensify their sensitivity to the data. 34 Early coding assists the researcher to identify the direction for further data gathering. After initial analysis, theoretical sampling is employed to direct collection of additional data that will inform the ‘developing theory’. 9 Initial coding advances into intermediate coding once categories begin to develop.

Theoretical sampling

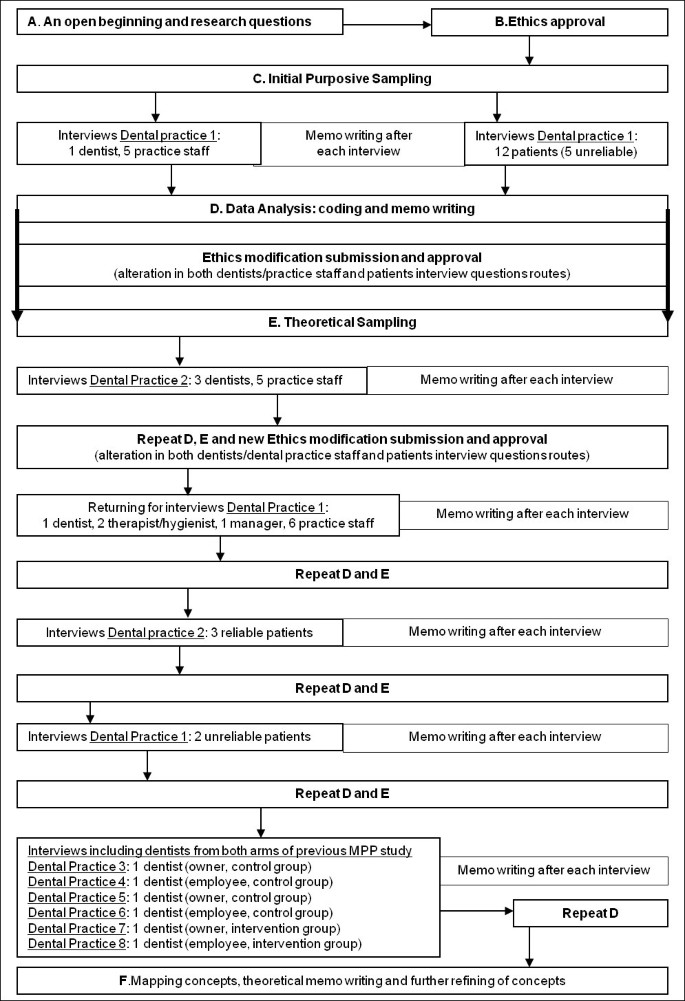

The purpose of theoretical sampling is to allow the researcher to follow leads in the data by sampling new participants or material that provides relevant information. As depicted in Figure 1 , theoretical sampling is central to GT design, aids the evolving theory 5 , 7 , 16 and ensures the final developed theory is grounded in the data. 9 Theoretical sampling in GT is for the development of a theoretical category, as opposed to sampling for population representation. 10 Novice researchers need to acknowledge this difference if they are to achieve congruence within the methodology. Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sampling as ‘the process of identifying and pursuing clues that arise during analysis in a grounded theory study’ (p. 68). During this process, additional information is sought to saturate categories under development. The analysis identifies relationships, highlights gaps in the existing data set and may reveal insight into what is not yet known. The exemplars in Box 1 highlight how theoretical sampling led to the inclusion of further data.

Examples of theoretical sampling.

Thus, theoretical sampling is used to focus and generate data to feed the iterative process of continual comparative analysis of the data. 6

Intermediate coding

Intermediate coding, identifying a core category, theoretical data saturation, constant comparative analysis, theoretical sensitivity and memoing occur in the next phase of the GT process. 6 Intermediate coding builds on the initial coding phase. Where initial coding fractures the data, intermediate coding begins to transform basic data into more abstract concepts allowing the theory to emerge from the data. During this analytic stage, a process of reviewing categories and identifying which ones, if any, can be subsumed beneath other categories occurs and the properties or dimension of the developed categories are refined. Properties refer to the characteristics that are common to all the concepts in the category and dimensions are the variations of a property. 37

At this stage, a core category starts to become evident as developed categories form around a core concept; relationships are identified between categories and the analysis is refined. Birks and Mills 6 affirm that diagramming can aid analysis in the intermediate coding phase. Grounded theorists interact closely with the data during this phase, continually reassessing meaning to ascertain ‘what is really going on’ in the data. 30 Theoretical saturation ensues when new data analysis does not provide additional material to existing theoretical categories, and the categories are sufficiently explained. 6

Advanced coding

Birks and Mills 6 described advanced coding as the ‘techniques used to facilitate integration of the final grounded theory’ (p. 177). These authors promote storyline technique (described in the following section) and theoretical coding as strategies for advancing analysis and theoretical integration. Advanced coding is essential to produce a theory that is grounded in the data and has explanatory power. 6 During the advanced coding phase, concepts that reach the stage of categories will be abstract, representing stories of many, reduced into highly conceptual terms. The findings are presented as a set of interrelated concepts as opposed to presenting themes. 28 Explanatory statements detail the relationships between categories and the central core category. 28

Storyline is a tool that can be used for theoretical integration. Birks and Mills 6 define storyline as ‘a strategy for facilitating integration, construction, formulation, and presentation of research findings through the production of a coherent grounded theory’ (p. 180). Storyline technique is first proposed with limited attention in Basics of Qualitative Research by Strauss and Corbin 12 and further developed by Birks et al. 38 as a tool for theoretical integration. The storyline is the conceptualisation of the core category. 6 This procedure builds a story that connects the categories and produces a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 24 Birks and Mills 6 contend that storyline can be ‘used to produce a comprehensive rendering of your grounded theory’ (p. 118). Birks et al. 38 had earlier concluded, ‘storyline enhances the development, presentation and comprehension of the outcomes of grounded theory research’ (p. 405). Once the storyline is developed, the GT is finalised using theoretical codes that ‘provide a framework for enhancing the explanatory power of the storyline and its potential as theory’. 6 Thus, storyline is the explication of the theory.

Theoretical coding occurs as the final culminating stage towards achieving a GT. 39 , 40 The purpose of theoretical coding is to integrate the substantive theory. 41 Saldaña 40 states, ‘theoretical coding integrates and synthesises the categories derived from coding and analysis to now create a theory’ (p. 224). Initial coding fractures the data while theoretical codes ‘weave the fractured story back together again into an organized whole theory’. 18 Advanced coding that integrates extant theory adds further explanatory power to the findings. 6 The examples in Box 2 describe the use of storyline as a technique.

Writing the storyline.

Theoretical sensitivity

As presented in Figure 1 , theoretical sensitivity encompasses the entire research process. Glaser and Strauss 5 initially described the term theoretical sensitivity in The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Theoretical sensitivity is the ability to know when you identify a data segment that is important to your theory. While Strauss and Corbin 12 describe theoretical sensitivity as the insight into what is meaningful and of significance in the data for theory development, Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sensitivity as ‘the ability to recognise and extract from the data elements that have relevance for the emerging theory’ (p. 181). Conducting GT research requires a balance between keeping an open mind and the ability to identify elements of theoretical significance during data generation and/or collection and data analysis. 6

Several analytic tools and techniques can be used to enhance theoretical sensitivity and increase the grounded theorist’s sensitivity to theoretical constructs in the data. 28 Birks and Mills 6 state, ‘as a grounded theorist becomes immersed in the data, their level of theoretical sensitivity to analytic possibilities will increase’ (p. 12). Developing sensitivity as a grounded theorist and the application of theoretical sensitivity throughout the research process allows the analytical focus to be directed towards theory development and ultimately result in an integrated and abstract GT. 6 The example in Box 3 highlights how analytic tools are employed to increase theoretical sensitivity.

Theoretical sensitivity.

The grounded theory

The meticulous application of essential GT methods refines the analysis resulting in the generation of an integrated, comprehensive GT that explains a process relating to a particular phenomenon. 6 The results of a GT study are communicated as a set of concepts, related to each other in an interrelated whole, and expressed in the production of a substantive theory. 5 , 7 , 16 A substantive theory is a theoretical interpretation or explanation of a studied phenomenon 6 , 17 Thus, the hallmark of grounded theory is the generation of theory ‘abstracted from, or grounded in, data generated and collected by the researcher’. 6 However, to ensure quality in research requires the application of rigour throughout the research process.

Quality and rigour

The quality of a grounded theory can be related to three distinct areas underpinned by (1) the researcher’s expertise, knowledge and research skills; (2) methodological congruence with the research question; and (3) procedural precision in the use of methods. 6 Methodological congruence is substantiated when the philosophical position of the researcher is congruent with the research question and the methodological approach selected. 6 Data collection or generation and analytical conceptualisation need to be rigorous throughout the research process to secure excellence in the final grounded theory. 44

Procedural precision requires careful attention to maintaining a detailed audit trail, data management strategies and demonstrable procedural logic recorded using memos. 6 Organisation and management of research data, memos and literature can be assisted using software programs such as NVivo. An audit trail of decision-making, changes in the direction of the research and the rationale for decisions made are essential to ensure rigour in the final grounded theory. 6

This article offers a framework to assist novice researchers visualise the iterative processes that underpin a GT study. The fundamental process and methods used to generate an integrated grounded theory have been described. Novice researchers can adapt the framework presented to inform and guide the design of a GT study. This framework provides a useful guide to visualise the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in conducting GT. Research conducted ethically and with meticulous attention to process will ensure quality research outcomes that have relevance at the practice level.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Grounded Theory

Definition:

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research methodology that aims to generate theories based on data that are grounded in the empirical reality of the research context. The method involves a systematic process of data collection, coding, categorization, and analysis to identify patterns and relationships in the data.

The ultimate goal is to develop a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, which is based on the data collected and analyzed rather than on preconceived notions or hypotheses. The resulting theory should be able to explain the phenomenon in a way that is consistent with the data and also accounts for variations and discrepancies in the data. Grounded Theory is widely used in sociology, psychology, management, and other social sciences to study a wide range of phenomena, such as organizational behavior, social interaction, and health care.

History of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory was first introduced by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s as a response to the limitations of traditional positivist approaches to social research. The approach was initially developed to study dying patients and their families in hospitals, but it was soon applied to other areas of sociology and beyond.

Glaser and Strauss published their seminal book “The Discovery of Grounded Theory” in 1967, in which they presented their approach to developing theory from empirical data. They argued that existing social theories often did not account for the complexity and diversity of social phenomena, and that the development of theory should be grounded in empirical data.

Since then, Grounded Theory has become a widely used methodology in the social sciences, and has been applied to a wide range of topics, including healthcare, education, business, and psychology. The approach has also evolved over time, with variations such as constructivist grounded theory and feminist grounded theory being developed to address specific criticisms and limitations of the original approach.

Types of Grounded Theory

There are two main types of Grounded Theory: Classic Grounded Theory and Constructivist Grounded Theory.

Classic Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Glaser and Strauss, and emphasizes the discovery of a theory that is grounded in data. The focus is on generating a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, without being influenced by preconceived notions or existing theories. The process involves a continuous cycle of data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories and subcategories that are grounded in the data. The categories and subcategories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that explains the phenomenon.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Charmaz, and emphasizes the role of the researcher in the process of theory development. The focus is on understanding how individuals construct meaning and interpret their experiences, rather than on discovering an objective truth. The process involves a reflexive and iterative approach to data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories that are grounded in the data and the researcher’s interpretations of the data. The categories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that accounts for the multiple perspectives and interpretations of the phenomenon being studied.

Grounded Theory Conducting Guide

Here are some general guidelines for conducting a Grounded Theory study:

- Choose a research question: Start by selecting a research question that is open-ended and focuses on a specific social phenomenon or problem.

- Select participants and collect data: Identify a diverse group of participants who have experienced the phenomenon being studied. Use a variety of data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis to collect rich and diverse data.

- Analyze the data: Begin the process of analyzing the data using constant comparison. This involves comparing the data to each other and to existing categories and codes, in order to identify patterns and relationships. Use open coding to identify concepts and categories, and then use axial coding to organize them into a theoretical framework.

- Generate categories and codes: Generate categories and codes that describe the phenomenon being studied. Make sure that they are grounded in the data and that they accurately reflect the experiences of the participants.

- Refine and develop the theory: Use theoretical sampling to identify new data sources that are relevant to the developing theory. Use memoing to reflect on insights and ideas that emerge during the analysis process. Continue to refine and develop the theory until it provides a comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon.

- Validate the theory: Finally, seek to validate the theory by testing it against new data and seeking feedback from peers and other researchers. This process helps to refine and improve the theory, and to ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Write up and disseminate the findings: Once the theory is fully developed and validated, write up the findings and disseminate them through academic publications and presentations. Make sure to acknowledge the contributions of the participants and to provide a detailed account of the research methods used.

Data Collection Methods

Grounded Theory Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Interviews : One of the most common data collection methods in Grounded Theory is the use of in-depth interviews. Interviews allow researchers to gather rich and detailed data about the experiences, perspectives, and attitudes of participants. Interviews can be conducted one-on-one or in a group setting.

- Observation : Observation is another data collection method used in Grounded Theory. Researchers may observe participants in their natural settings, such as in a workplace or community setting. This method can provide insights into the social interactions and behaviors of participants.

- Document analysis: Grounded Theory researchers also use document analysis as a data collection method. This involves analyzing existing documents such as reports, policies, or historical records that are relevant to the phenomenon being studied.

- Focus groups : Focus groups involve bringing together a group of participants to discuss a specific topic or issue. This method can provide insights into group dynamics and social interactions.

- Fieldwork : Fieldwork involves immersing oneself in the research setting and participating in the activities of the participants. This method can provide an in-depth understanding of the culture and social dynamics of the research setting.

- Multimedia data: Grounded Theory researchers may also use multimedia data such as photographs, videos, or audio recordings to capture the experiences and perspectives of participants.

Data Analysis Methods

Grounded Theory Data Analysis Methods are as follows:

- Open coding: Open coding is the process of identifying concepts and categories in the data. Researchers use open coding to assign codes to different pieces of data, and to identify similarities and differences between them.

- Axial coding: Axial coding is the process of organizing the codes into broader categories and subcategories. Researchers use axial coding to develop a theoretical framework that explains the phenomenon being studied.

- Constant comparison: Grounded Theory involves a process of constant comparison, in which data is compared to each other and to existing categories and codes in order to identify patterns and relationships.

- Theoretical sampling: Theoretical sampling involves selecting new data sources based on the emerging theory. Researchers use theoretical sampling to collect data that will help refine and validate the theory.

- Memoing : Memoing involves writing down reflections, insights, and ideas as the analysis progresses. This helps researchers to organize their thoughts and develop a deeper understanding of the data.

- Peer debriefing: Peer debriefing involves seeking feedback from peers and other researchers on the developing theory. This process helps to validate the theory and ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Member checking: Member checking involves sharing the emerging theory with the participants in the study and seeking their feedback. This process helps to ensure that the theory accurately reflects the experiences and perspectives of the participants.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple sources of data to validate the emerging theory. Researchers may use different data collection methods, different data sources, or different analysts to ensure that the theory is grounded in the data.

Applications of Grounded Theory

Here are some of the key applications of Grounded Theory:

- Social sciences : Grounded Theory is widely used in social science research, particularly in fields such as sociology, psychology, and anthropology. It can be used to explore a wide range of social phenomena, such as social interactions, power dynamics, and cultural practices.

- Healthcare : Grounded Theory can be used in healthcare research to explore patient experiences, healthcare practices, and healthcare systems. It can provide insights into the factors that influence healthcare outcomes, and can inform the development of interventions and policies.

- Education : Grounded Theory can be used in education research to explore teaching and learning processes, student experiences, and educational policies. It can provide insights into the factors that influence educational outcomes, and can inform the development of educational interventions and policies.

- Business : Grounded Theory can be used in business research to explore organizational processes, management practices, and consumer behavior. It can provide insights into the factors that influence business outcomes, and can inform the development of business strategies and policies.

- Technology : Grounded Theory can be used in technology research to explore user experiences, technology adoption, and technology design. It can provide insights into the factors that influence technology outcomes, and can inform the development of technology interventions and policies.

Examples of Grounded Theory

Examples of Grounded Theory in different case studies are as follows:

- Glaser and Strauss (1965): This study, which is considered one of the foundational works of Grounded Theory, explored the experiences of dying patients in a hospital. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of dying, and that was grounded in the data.

- Charmaz (1983): This study explored the experiences of chronic illness among young adults. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained how individuals with chronic illness managed their illness, and how their illness impacted their sense of self.

- Strauss and Corbin (1990): This study explored the experiences of individuals with chronic pain. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the different strategies that individuals used to manage their pain, and that was grounded in the data.

- Glaser and Strauss (1967): This study explored the experiences of individuals who were undergoing a process of becoming disabled. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of becoming disabled, and that was grounded in the data.

- Clarke (2005): This study explored the experiences of patients with cancer who were receiving chemotherapy. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the factors that influenced patient adherence to chemotherapy, and that was grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory Research Example

A Grounded Theory Research Example Would be:

Research question : What is the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process?

Data collection : The researcher conducted interviews with first-generation college students who had recently gone through the college admission process. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis: The researcher used a constant comparative method to analyze the data. This involved coding the data, comparing codes, and constantly revising the codes to identify common themes and patterns. The researcher also used memoing, which involved writing notes and reflections on the data and analysis.

Findings : Through the analysis of the data, the researcher identified several themes related to the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process, such as feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of the process, lacking knowledge about the process, and facing financial barriers.

Theory development: Based on the findings, the researcher developed a theory about the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process. The theory suggested that first-generation college students faced unique challenges in the college admission process due to their lack of knowledge and resources, and that these challenges could be addressed through targeted support programs and resources.

In summary, grounded theory research involves collecting data, analyzing it through constant comparison and memoing, and developing a theory grounded in the data. The resulting theory can help to explain the phenomenon being studied and guide future research and interventions.

Purpose of Grounded Theory

The purpose of Grounded Theory is to develop a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, process, or interaction. This theoretical framework is developed through a rigorous process of data collection, coding, and analysis, and is grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory aims to uncover the social processes and patterns that underlie social phenomena, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these processes and patterns. It is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings, and is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

The ultimate goal of Grounded Theory is to generate a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, and that can be used to explain and predict social phenomena. This theoretical framework can then be used to inform policy and practice, and to guide future research in the field.

When to use Grounded Theory

Following are some situations in which Grounded Theory may be particularly useful:

- Exploring new areas of research: Grounded Theory is particularly useful when exploring new areas of research that have not been well-studied. By collecting and analyzing data, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the social processes and patterns underlying the phenomenon of interest.

- Studying complex social phenomena: Grounded Theory is well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that involve multiple social processes and interactions. By using an iterative process of data collection and analysis, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the complexity of the social phenomenon.

- Generating hypotheses: Grounded Theory can be used to generate hypotheses about social processes and interactions that can be tested in future research. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for further research and hypothesis testing.

- Informing policy and practice : Grounded Theory can provide insights into the factors that influence social phenomena, and can inform policy and practice in a variety of fields. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for intervention and policy development.

Characteristics of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research method that is characterized by several key features, including:

- Emergence : Grounded Theory emphasizes the emergence of theoretical categories and concepts from the data, rather than preconceived theoretical ideas. This means that the researcher does not start with a preconceived theory or hypothesis, but instead allows the theory to emerge from the data.

- Iteration : Grounded Theory is an iterative process that involves constant comparison of data and analysis, with each round of data collection and analysis refining the theoretical framework.

- Inductive : Grounded Theory is an inductive method of analysis, which means that it derives meaning from the data. The researcher starts with the raw data and systematically codes and categorizes it to identify patterns and themes, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these patterns.

- Reflexive : Grounded Theory requires the researcher to be reflexive and self-aware throughout the research process. The researcher’s personal biases and assumptions must be acknowledged and addressed in the analysis process.

- Holistic : Grounded Theory takes a holistic approach to data analysis, looking at the entire data set rather than focusing on individual data points. This allows the researcher to identify patterns and themes that may not be apparent when looking at individual data points.

- Contextual : Grounded Theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the context in which social phenomena occur. This means that the researcher must consider the social, cultural, and historical factors that may influence the phenomenon of interest.

Advantages of Grounded Theory

Advantages of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Flexibility : Grounded Theory is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings. It is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

- Validity : Grounded Theory aims to develop a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, which enhances the validity and reliability of the research findings. The iterative process of data collection and analysis also helps to ensure that the research findings are reliable and robust.

- Originality : Grounded Theory can generate new and original insights into social phenomena, as it is not constrained by preconceived theoretical ideas or hypotheses. This allows researchers to explore new areas of research and generate new theoretical frameworks.

- Real-world relevance: Grounded Theory can inform policy and practice, as it provides insights into the factors that influence social phenomena. The theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be used to inform policy development and intervention strategies.

- Ethical : Grounded Theory is an ethical research method, as it allows participants to have a voice in the research process. Participants’ perspectives are central to the data collection and analysis process, which ensures that their views are taken into account.

- Replication : Grounded Theory is a replicable method of research, as the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be tested and validated in future research.

Limitations of Grounded Theory

Limitations of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Grounded Theory can be a time-consuming method, as the iterative process of data collection and analysis requires significant time and effort. This can make it difficult to conduct research in a timely and cost-effective manner.

- Subjectivity : Grounded Theory is a subjective method, as the researcher’s personal biases and assumptions can influence the data analysis process. This can lead to potential issues with reliability and validity of the research findings.

- Generalizability : Grounded Theory is a context-specific method, which means that the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. This can limit the applicability of the research findings.

- Lack of structure : Grounded Theory is an exploratory method, which means that it lacks the structure of other research methods, such as surveys or experiments. This can make it difficult to compare findings across different studies.

- Data overload: Grounded Theory can generate a large amount of data, which can be overwhelming for researchers. This can make it difficult to manage and analyze the data effectively.

- Difficulty in publication: Grounded Theory can be challenging to publish in some academic journals, as some reviewers and editors may view it as less rigorous than other research methods.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and...

ANOVA (Analysis of variance) – Formulas, Types...

Graphical Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Grounded Theory Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Your complete guide to grounded theory research.

11 min read If you have an area of interest, but no hypothesis yet, try grounded theory research. You conduct data collection and analysis, forming a theory based on facts. Read our ultimate guide for everything you need to know.

What is grounded theory in research?

Grounded theory is a systematic qualitative research method that collects empirical data first, and then creates a theory ‘grounded’ in the results.

The constant comparative method was developed by Glaser and Strauss, described in their book, Awareness of Dying (1965). They are seen as the founders of classic grounded theory.

Research teams use grounded theory to analyze social processes and relationships.

Because of the important role of data, there are key stages like data collection and data analysis that need to happen in order for the resulting data to be useful.

The grounded research results are compared to strengthen the validity of the findings to arrive at stronger defined theories. Once the data analysis cannot continue to refine the new theories down, a final theory is confirmed.

Grounded research is different from experimental research or scientific inquiry as it does not need a hypothesis theory at the start to verify. Instead, the evolving theory is based on facts and evidence discovered during each stage.Also, grounded research also doesn’t have a preconceived understanding of events or happenings before the qualitative research commences.

Free eBook: Qualitative research design handbook

When should you use grounded theory research?

Grounded theory research is useful for businesses when a researcher wants to look into a topic that has existing theory or no current research available. This means that the qualitative research results will be unique and can open the doors to the social phenomena being investigated.

In addition, businesses can use this qualitative research as the primary evidence needed to understand whether it’s worth placing investment into a new line of product or services, if the research identifies key themes and concepts that point to a solvable commercial problem.

Grounded theory methodology

There are several stages in the grounded theory process:

1. Data planning

The researcher decides what area they’re interested in.

They may create a guide to what they will be collecting during the grounded theory methodology. They will refer to this guide when they want to check the suitability of the qualitative data, as they collect it, to avoid preconceived ideas of what they know impacting the research.

A researcher can set up a grounded theory coding framework to identify the correct data. Coding is associating words, or labels, that are useful to the social phenomena that is being investigated. So, when the researcher sees these words, they assign the data to that category or theme.

In this stage, you’ll also want to create your open-ended initial research questions. Here are the main differences between open and closed-ended questions:

These will need to be adapted as the research goes on and more tangents and areas to explore are discovered. To help you create your questions, ask yourself:

- What are you trying to explain?

- What experiences do you need to ask about?

- Who will you ask and why?

2. Data collection and analysis

Data analysis happens at the same time as data collection. In grounded theory analysis, this is also known as constant comparative analysis, or theoretical sampling.

The researcher collects qualitative data by asking open-ended questions in interviews and surveys, studying historical or archival data, or observing participants and interpreting what is seen. This collected data is transferred into transcripts.

The categories or themes are compared and further refined by data, until there are only a few strong categories or themes remaining. Here is where coding occurs, and there are different levels of coding as the categories or themes are refined down:

- Data collection (Initial coding stage): Read through the data line by line

- Open coding stage: Read through the transcript data several times, breaking down the qualitative research data into excerpts, and make summaries of the concept or theme.

- Axial coding stage: Read through and compare further data collection to summarize concepts or themes to look for similarities and differences. Make defined summaries that help shape an emerging theory.

- Selective coding stage: Use the defined summaries to identify a strong core concept or theme.

During analysis, the researcher will apply theoretical sensitivity to the collected data they uncover, so that the meaning of nuances in what they see can be fully understood.

This coding process repeats until the researcher has reached theoretical saturation. In grounded theory analysis, this is where all data has been researched and there are no more possible categories or themes to explore.

3. Data analysis is turned into a final theory

The researcher takes the core categories and themes that they have gathered and integrates them into one central idea (a new theory) using selective code. This final grounded theory concludes the research.

The new theory should be a few simple sentences that describe the research, indicating what was and was not covered in it.

An example of using grounded theory in business

One example of how grounded theory may be used in business is to support HR teams by analyzing data to explore reasons why people leave a company.

For example, a company with a high attrition rate that has not done any research on this area before may choose grounded theory to understand key reasons why people choose to leave.

Researchers may start looking at the quantitative data around departures over the year and look for patterns. Coupled with this, they may conduct qualitative data research through employee engagement surveys , interview panels for current employees, and exit interviews with leaving employees.

From this information, they may start coding transcripts to find similarities and differences (coding) picking up on general themes and concepts. For example, a group of excepts like:

- “The hours I worked were far too long and I hated traveling home in the dark”

- “My manager didn’t appreciate the work I was doing, especially when I worked late”

- There are no good night bus routes home that I could take safely”

Using open coding, a researcher could compare excerpts and suggest the themes of managerial issues, a culture of long hours and lack of traveling routes at night.

With more samples and information, through axial coding, stronger themes of lack of recognition and having too much work (which led people to working late), could be drawn out from the summaries of the concepts and themes.

This could lead to a selective coding conclusion that people left because they were ‘overworked and under-appreciated’.

With this information, a grounded theory can help HR teams look at what teams do day to day, exploring ways to spread workloads or reduce them. Also, there could be training supplied to management and employees to engage professional development conversations better.

Advantages of grounded theory

- No need for hypothesis – Researchers don’t need to know the details about the topic they want to investigate in advance, as the grounded theory methodology will bring up the information.

- Lots of flexibility – Researchers can take the topic in whichever direction they think is best, based on what the data is telling them. This means that exploration avenues that may be off-limits in traditional experimental research can be included.

- Multiple stages improve conclusion – Having a series of coding stages that refine the data into clear and strong concepts or themes means that the grounded theory will be more useful, relevant and defined.

- Data-first – Grounded theory relies on data analysis in the first instance, so the conclusion is based on information that has strong data behind it. This could be seen as having more validity.

Disadvantages of grounded theory

- Theoretical sensitivity dulled – If a researcher does not know enough about the topic being investigated, then their theoretical sensitivity about what data means may be lower and information may be missed if it is not coded properly.

- Large topics take time – There is a significant time resource required by the researcher to properly conduct research, evaluate the results and compare and analyze each excerpt. If the research process finds more avenues for investigation, for example, when excerpts contradict each other, then the researcher is required to spend more time doing qualitative inquiry.

- Bias in interpreting qualitative data – As the researcher is responsible for interpreting the qualitative data results, and putting their own observations into text, there can be researcher bias that would skew the data and possibly impact the final grounded theory.

- Qualitative research is harder to analyze than quantitative data – unlike numerical factual data from quantitative sources, qualitative data is harder to analyze as researchers will need to look at the words used, the sentiment and what is being said.

- Not repeatable – while the grounded theory can present a fact-based hypothesis, the actual data analysis from the research process cannot be repeated easily as opinions, beliefs and people may change over time. This may impact the validity of the grounded theory result.

What tools will help with grounded theory?

Evaluating qualitative research can be tough when there are several analytics platforms to manage and lots of subjective data sources to compare. Some tools are already part of the office toolset, like video conferencing tools and excel spreadsheets.

However, most tools are not purpose-built for research, so researchers will be manually collecting and managing these files – in the worst case scenario, by pen and paper!

Use a best-in-breed management technology solution to collect all qualitative research and manage it in an organized way without large time resources or additional training required.

Qualtrics provides a number of qualitative research analysis tools, like Text iQ , powered by Qualtrics iQ, provides powerful machine learning and native language processing to help you discover patterns and trends in text.

This also provides you with research process tools:

- Sentiment analysis — a technique to help identify the underlying sentiment (say positive, neutral, and/or negative) in qualitative research text responses

- Topic detection/categorisation — The solution makes it easy to add new qualitative research codes and group by theme. Easily group or bucket of similar themes that can be relevant for the business and the industry (eg. ‘Food quality’, ‘Staff efficiency’ or ‘Product availability’)

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

An Introduction to Grounded Theory with a Special Focus on Axial Coding and the Coding Paradigm

- Open Access

- First Online: 27 April 2019

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Maike Vollstedt 4 &

- Sebastian Rezat 5

Part of the book series: ICME-13 Monographs ((ICME13Mo))

94k Accesses

128 Citations

8 Altmetric

In this chapter we introduce grounded theory methodology and methods. In particular we clarify which research questions are appropriate for a grounded theory study and give an overview of the main techniques and procedures, such as the coding procedures, theoretical sensitivity, theoretical sampling, and theoretical saturation. We further discuss the role of theory within grounded theory and provide examples of studies in which the coding paradigm of grounded theory has been altered in order to be better suitable for applications in mathematics education. In our exposition we mainly refer to grounded theory techniques and procedures according to Strauss and Corbin (Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 1990 ), but also include other approaches in the discussion in order to point out the particularities of the approach by Strauss and Corbin.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory Methods

Grounded Theory Methodology: Principles and Practices

- Grounded theory

- Coding procedures

- Coding paradigm

- Coding families

- Theoretical sensitivity

1 Introduction

In 1967, sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss published their seminal book “The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research” (Glaser and Strauss 1967 ), which lays the foundation for one of the most prominent and influential qualitative research methodologies in the social sciences and beyond. With their focus on theory development, they dissociate themselves from mere theory verification and the concomitant separation of the context of theory discovery and the context of theory justification, which was the prominent scientific method at that time. With their approach to qualitative research, they also go beyond the mere description of phenomena. Originally, the book was written as a book for young researchers. One of its main intentions was to legitimate qualitative research (Mey and Mruck 2011 ).

Quite soon after their joint publication in 1967, Glaser and Strauss developed grounded theory in different directions and started to argue their own understanding of grounded theory methodology and methods apart from each other in different ways, Glaser primarily on his own, Strauss also together with Juliet Corbin (Glaser 1978 ; Strauss 1987 ; Strauss and Corbin 1990 ). Later, students of Glaser and Strauss further developed the different interpretations of grounded theory methodology so that today there is a second generation of grounded theory researchers, namely Juliet Corbin, Adele E. Clarke, and Kathy Charmaz (Morse et al. 2009 ). As those further developments of grounded theory resulted in different research methodologies, it has been suggested to talk about grounded theory methodologies in plural or at least to acknowledge that there are numerous modi operandi involving grounded theory methods in different fields of research as well as different national traditions (Mey and Mruck 2011 ). In Germany, for instance, it is still most common to work with the grounded theory methodology version that was published by Strauss and Corbin in 1990 (German translation from 1996 ). The second generation’s developments are still hardly noticed.

As this chapter is an introduction to grounded theory methodology and methods, our aim is to outline the common core of the different approaches to grounded theory. Therefore, we give a short introduction to grounded theory as a methodology (Sect. 4.2 ) and its techniques and procedures (Sect. 4.3 ). We further discuss an issue that lies at the heart of grounded theory, namely the role of theory within the methodology (Sect. 4.4 ). There, we also describe some examples of studies that used grounded theory as the main methodology, but took a specific stance to theory development in using the methodology.

2 A Short Positioning of Grounded Theory

This section provides a short overview of grounded theory as a methodology. We aim to answer two questions: 1. What is a grounded theory? 2. What kind of research questions are appropriate for a grounded theory study?

2.1 What Is Grounded Theory?

There is no simple answer to this question as the term grounded theory adheres to different research elements. In the first place, grounded theory is a methodology, which is characterized by the iterative process and the interrelatedness of planning, data collection, data analysis, and theory development. Grounded theory further provides a particular set of systematic methods, which support abstraction from the data in order to develop a theory that is grounded in the empirical data. These methods include different coding procedures, which are based on the method of constant comparison. New data are gathered continuously and new cases are included in the analysis based on their potential contribution to the further development and refinement of the evolving theory. This sampling method is called theoretical sampling . The iterative process of data collection according to theoretical sampling, data analysis, and theory development is continued until new data do not contribute any longer to a substantial development of the theory, i.e. until theoretical saturation is achieved. The theory that is the product of this process is also referred to as grounded theory . The quality of a grounded theory is not evaluated according to the standard criteria of test theory, i.e. objectivity, reliability and validity, but according to criteria such as credibility, plausibility, and trustworthiness.

2.2 What Kind of Research Questions Are Appropriate for a Grounded Theory Study?

According to the usual scientific procedure, the research question is at the outset of any scientific endeavour. It is the essence of what the researcher wants to know. The overall purpose of the study is to find an answer to the research question. Methodology and related methods are but a vehicle to find the (possibly best) answer to the research question. Ideally, it should be the research question that determines the methodology and not vice versa. Thus, it is important to ask what kind of research questions are appropriate for a grounded theory study. The character of the research question will influence the methodology and the choice of methods. We will try to characterize the kind of questions to which grounded theory could probably provide a good answer.

The overarching goal of grounded theory is to develop theory. Therefore, grounded theory studies may be carried out related to research phenomena or objects, which lack a (sufficient) theoretical foundation. It may be, that no theory exists for the phenomena under study or that the existing theories are insufficient in that

they lack important concepts;

the relationships among the concepts are not elaborated enough;

the relevance of the concepts and their relationships has not been corroborated for the population or the context under study.

Due to the origins of grounded theory in the social sciences, the main epistemological interest lies in predicting and explaining behavior in social interaction. Thus, Strauss and Corbin ( 1990 ) stress the orientation towards action and processes of grounded theory research questions.

3 A Short Introduction to the Methods and Techniques of Grounded Theory

The methods and techniques of grounded theory make use of different elements: some relate to the collection, some to the evaluation of data, and some refer to the research process. The following section gives a short introduction to the most important methods and techniques to make the start of working with grounded theory easier for a newcomer to this vast field. A more detailed description of the procedures and techniques can be found in the original literature describing grounded theory (e.g., Glaser 1978 ; Strauss 1987 ; Strauss and Corbin 1990 ). Note that technical terms and procedures may differ (slightly) when adhering to literature from different traditions of grounded theory. Even within one tradition of grounded theory, the methodology may also change over time (see Sect. 4.3.3.2 for an example with relation to the coding paradigm proposed by Strauss and Corbin 1990 and Corbin and Strauss 2015 respectively). To gain a more practical idea about the application of grounded theory, we suggest looking at Vollstedt ( 2015 ) for an example of the application of grounded theory methods in an international comparative study in mathematics education carried out in Germany and Hong Kong.

3.1 Theoretical Sensitivity and Sensitizing Concepts

When starting to work with grounded theory, there is no fixed theory at hand with which to evaluate the data. On the contrary, the researcher moves into an open field of study with many unclear aspects. As described above, important concepts are missing, and/or their relationship is not elaborated enough. The longer the researcher will have worked in this field, the clearer those unclear aspects will (hopefully) become. In order to make sense of the data, an important ability of the researcher is theoretical sensitivity. The notion of theoretical sensitivity is closely linked to grounded theory and Glaser ( 1978 ) even devoted a whole book to this issue. Corbin and Strauss ( 2015 ) describe sensitivity as “having insights as well as being tuned into and being able to pick up on relevant issues, events, and happenings during collection and analysis of the data” (p. 78). According to Glaser with the assistance of Holton ( 2004 ) the essence of theoretical sensitivity is the “ability to generate concepts from data and to relate them according to normal models of theory in general” (para. 43). They further sum up a number of single abilities that characterize the theoretical sensitivity of a researcher. These are “the personal and temperamental bent to maintain analytic distance, tolerate confusion and regression while remaining open, trusting to preconscious processing and to conceptual emergence […] the ability to develop theoretical insight into the area of research combined with the ability to make something of these insights […] the ability to conceptualize and organize, make abstract connections, visualize and think multivariately” (para. 43).

The opinions about how a researcher might develop theoretical sensitivity differ between the two founders of grounded theory and are in fact one of the main differences between their approaches. While Glaser (with the assistance of Holton 2004 ) suggests that the “first step in gaining theoretical sensitivity is to enter the research setting with as few predetermined ideas as possible” (para. 43), Strauss and Corbin ( 1990 ) name different sources of theoretical sensitivity: these are respective literature, the professional and personal experience of the researcher as well as the analytical process itself. However, the researcher is not supposed to follow the beaten track of the literature or his/her personal experience, but to question these and go beyond in order to get novel theoretical insight. In “Basics of qualitative research” Strauss and Corbin ( 1990 ) describe techniques to foster theoretical sensitivity. These are questioning, analyzing single words, phrases or sentences, and comparing, thus techniques, which pervade grounded theory in general.

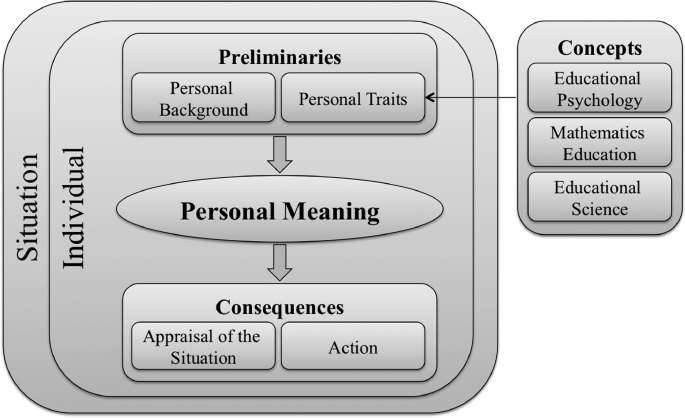

3.2 Interdependence of Data Collection, Analysis, and Development of Theory