An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Treatment Guidelines for PTSD: A Systematic Review

Alicia martin.

1 Discipline of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT 2617, Australia; [email protected] (M.N.); [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (G.P.); [email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] (J.K.C.)

Mark Naunton

Gregory peterson.

2 School of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS 7001, Australia

Jackson Thomas

Julia k. christenson, associated data.

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Background: The aim of this review was to assess the quality of international treatment guidelines for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and identify differences between guideline recommendations, with a focus on the treatment of nightmares. Methods: Guidelines were identified through electronic searches of MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, Embase and Science Direct, as well as web-based searches of international guideline repositories, websites of psychiatric organisations and targeted web-searches for guidelines from the three most populous English-speaking countries in each continent. Data in relation to recommendations were extracted and the AGREE II criteria were applied to assess for quality. Results: Fourteen guidelines, published between 2004–2020, were identified for inclusion in this review. Only five were less than 5 years old. Three guidelines scored highly across all AGREE II domains, while others varied between domains. Most guidelines consider both psychological and pharmacological therapies as first-line in PTSD. All but one guideline recommended cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as first-line psychological treatment, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as first-line pharmacological treatment. Most guidelines do not mention the targeted treatment of nightmares as a symptom of PTSD. Prazosin is discussed in several guidelines for the treatment of nightmares, but recommendations vary widely. Most PTSD guidelines were deemed to be of good quality; however, many could be considered out of date. Recommendations for core PTSD symptoms do not differ greatly between guidelines. However, despite the availability of targeted treatments for nightmares, most guidelines do not adequately address this. Conclusions: Guidelines need to be kept current to maintain clinical utility. Improvements are most needed in the AGREE II key domains of ‘applicability’, ‘rigour of development’ and ‘stakeholder involvement’. Due to the treatment-resistant nature of nightmares, guideline development groups should consider producing more detailed recommendations for their targeted treatment. More high-quality trials are also required to provide a solid foundation for making these clinical recommendations for the management of nightmares in PTSD.

1. Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating mental condition that can significantly impact the sufferer’s quality of life [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. A study by Rapaport et al. found that 59% of patients suffering from PTSD had severely impaired overall quality of life based on the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire [ 4 ]. Stein et al. found that 38.9% of patients with PTSD had missed at least one work day in the last month due to emotional problems, compared to only 5.4% of people who did not suffer from a mental health condition, and Kessler reported that a PTSD diagnosis increases the likelihood of being homeless by 150% [ 5 , 6 ]. PTSD is also commonly associated with comorbidities of depression and substance use disorders, and a significantly increased risk of suicide [ 7 ].

PTSD comprises four symptom clusters: ‘avoidance’, ‘numbing’, ‘hyper-arousal’ and the hallmark ‘re-experiencing’ or ‘intrusive symptoms’, which include unwanted thoughts, flashbacks and nightmares [ 8 ]. Nightmares are often resistant to general PTSD treatment and have been linked with a five-fold increase in suicidality [ 9 ]. Nightmares should therefore be considered one of the most important symptoms to treat, yet they are often overlooked as a secondary symptom of PTSD [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. In addition, there appears to be few recommendations for the treatment of nightmares in guidelines, even though there are targeted treatments available, such as image rehearsal therapy (IRT) and pharmacotherapies including prazosin, terazosin and some atypical antipsychotics [ 13 , 14 ].

PTSD can be treated using psychological therapies, pharmacotherapy or a combination of the two. The recommended psychological therapies in Australia include trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitisation reprocessing (EMDR) [ 15 , 16 ]. For pharmacotherapy in PTSD, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants are recommended [ 15 , 16 ].

Evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of PTSD are valuable resources for psychiatrists and other health professionals to aid in the development of appropriate individual treatment plans for their patients, whilst also deterring the implementation of potentially ineffective or harmful treatments [ 17 , 18 ]. It can be difficult for healthcare professionals to keep up with and critically appraise the enormous volume of newly-published research in their field [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Evidence indicates that clinical psychiatric practice is often not in line with current guideline recommendations and hence may not reflect the best available evidence [ 22 , 23 ]. There are many barriers to implementing guidelines into practice. These include a perceived lack of time to review lengthy guidelines, an oversupply of guidelines (often with conflicting recommendations), a lack of usefulness in patients with significant comorbidities, a belief that current practice is best care based on past clinical experience, and an aversion to the perceived “rigidity” of guideline recommendations [ 19 , 21 , 22 ]. Every guideline is developed using different methodologies which can influence the quality of recommendations.

This review aimed to assess the quality of international treatment guidelines for PTSD, as well as identify differences between guideline recommendations, with a focus on the treatment of nightmares.

2. Materials and Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement was followed to report the results of this review [ 24 ]. The review was registered with PROSPERO on the 21st of December 2017, registration number: CRD42017084122 [ 25 ].

2.1. Search Strategy

Relevant guidelines were identified via an electronic search of databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, PubMed, Embase and Science Direct, conducted in October 2017 using the search terms in Table 1 . There were no date restrictions imposed; however, searches were restricted to the English language. A secondary search following the same methods was completed in September 2020 to identify any guidelines published after the initial search. Database searching was supplemented by web-based searches of guideline repositories ( www.guidelines.gov , clinicalguidelines.gov.au and https://www.g-i-n.net/ (accessed date: 5 October 2017 and 21 September 2020), websites of international psychiatric organisations and targeted web-searches for guidelines from the three most populous English-speaking countries in each continent using combinations of the country names and search terms in Table 1 . The latter was an additional step in an attempt to systematically capture any country-specific guidelines that were not listed in a guideline repository and may have otherwise been missed due to the search engine’s algorithm preferencing already identified guidelines. Reference lists of relevant guidelines were also searched manually for further relevant guidelines.

Search Terms.

2.2. Selection Criteria

All treatment guidelines for PTSD or nightmares were considered for inclusion. Guidelines were excluded if they were specific to children or adolescents, were based entirely on other guidelines, did not make clear recommendations for treatments or were specific to complex PTSD. Complex PTSD is caused by exposure to an extreme or prolonged stressor from which escape is difficult or impossible (such as childhood abuse), presenting with a range of symptoms in addition to core PTSD symptoms, and for which there is a lack of available evidence for diagnosis and treatment [ 26 ].

Titles/abstracts of all identified records were reviewed and assessed for relevance by one researcher (AM). Full-text documents of relevant records were then obtained and reassessed against the inclusion criteria by the same researcher. Any concerns were rectified by consensus with two additional researchers (MN and SK).

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Data from relevant guidelines were independently extracted into a table by one researcher (AM). The following data were extracted: guideline title, author/institution, country, publication date, methodology for development of recommendations, first-line treatment recommendations and recommendations for the targeted treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares. No statistical analyses were completed.

2.4. Evaluation of Guideline Quality

The AGREE II instrument is a validated tool for the appraisal of health-related guidelines [ 27 ]. It consists of a checklist of 23 items grouped into six domains: scope and purpose; stakeholder involvement; rigour of development; clarity and presentation; applicability; and editorial independence. Each item is given a score from 1–7, with a score of 7 indicating that reporting of that item is exceptional and all criteria for the item have been met and a score of 1 indicating reporting of the item is absent or reporting criteria were not met. A quality score is then calculated for each of the 6 domains. This score is reported as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain and can then be used to interpret the strengths and limitations of the guideline, noting that there is no accepted cut-off score to define a ‘good’ guideline. The ‘Recommended for use?’ assessment (with options of Yes, No or Yes with modifications) is based on whether the guideline scored reasonably across all domains, the overall readability and usability of the guideline, and if the content is current. On completion of the AGREE II online tutorial, three reviewers (AM, JC & KM) independently assessed each guideline against the AGREE II criteria. They later met and agreed by consensus on the final averaged scores.

The search strategy identified a total of 133 records, of which, 14 guidelines matched the criteria for inclusion in this review. The secondary search in September 2020 identified updated versions of three previously identified guidelines. Reasons for exclusion of records are summarised in Figure 1 . The general characteristics of each guideline are summarised in Table 2 .

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Characteristics of included guidelines.

CBT = cognitive behaviour therapy, CPT = cognitive processing therapy, CT = cognitive therapy, EMDR = eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, IRT = image rehearsal therapy, PE = prolonged exposure, SNRI = serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, TCA = tricyclic antidepressant. * This guideline has not been reviewed since its publication in 2006. It is the policy of the Canadian Psychiatric Association to review clinical practice guidelines every 5 years, and any document that does not explicitly state that it has been reviewed should be considered as a historical document only. It is included in this review for interest, but we acknowledge that it is not considered current guidance.

3.1. Guideline Characteristics

The fourteen guidelines identified in this review were published between 2004 and 2020, with only five less than 5 years old. There were four guidelines from the US, three from international organisations (the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry and the World Health Organisation) two each from Australia, Canada and the UK, and one from South Africa. Their recommendations were based on evidence from conducting a systematic review, a consensus process, or a combination of the two.

3.2. Assessment of Guideline Quality

Domain scores and guideline abbreviations are presented in Table 3 . All guidelines scored well in domain 1 ‘scope and purpose’. It had the second highest median score of 87% (range: 68–100%) and two guidelines (Phoenix & VA) scored 100% in this domain.

AGREE II assessment scores * for each guideline.

Y/M = Yes with modifications. * Domain 1. Scope and Purpose is concerned with the overall aim of the guideline, the specific health questions, and the target population (items 1–3). Domain 2. Stakeholder Involvement focuses on the extent to which the guideline was developed by appropriate stakeholders and represents the views of its intended users (items 4–6). Domain 3. Rigour of Development relates to the process used to gather and synthesise the evidence, the methods to formulate the recommendations, and to update them (items 7–14). Domain 4. Clarity of Presentation deals with the language, structure, and format of the guideline (items 15–17). Domain 5. Applicability pertains to the likely barriers and facilitators to implementation, strategies to improve uptake, and resource implications of applying the guideline (items 18–21). Domain 6. Editorial Independence is concerned with the formulation of recommendations not being unduly biased with competing interests (items 22–23). ** The ISTSS guidelines are published as a book for purchase. The Methodology and Recommendations document is available publicly on the internet, but the Evidence Summary documents, and reference lists are available for members only. These documents were requested but not supplied, so it is likely the ISTSS guideline would have scored higher in certain categories if these documents were available.

Scores in domain 2 ‘stakeholder involvement’ were more varied, with two guidelines scoring below 50% (AASM & WFSBP) yet four scoring above 90% (Phoenix, VA, APoA & NICE) (range 30–100%). Scores in domain 3 ‘rigour of development’ varied similarly to domain 2, with one guideline scoring below 50% (SASOP) and two above 90% (APoA & WHO) (Range: 44–92%). The highest scores were seen in domain 4 ‘clarity of presentation’, with a median score of 90% (range 71–100%). This is in contrast with domain 5 ‘applicability’, which saw high variability and a median score of just 49% (range 30–74%). Finally, domain 6 ‘editorial independence’ had the greatest variability between guidelines, with four scores of 90% or more (AASM, Phoenix, eTG and APoA) and four scores of 50% or less (CPA, WFSBP, ISTSS & SASOP) (range: 26–100%). Overall, the PTSD guidelines were of reasonably high quality; six are recommended for use, six are recommended with modifications, and two are not recommended for use after quality assessment ( Table 3 ).

3.3. Recommendations in Guidelines

Five guidelines (36%) recommended that pharmacological interventions should be second-line to psychological interventions, while the others made no specific recommendation for one over the other. All fourteen guidelines (100%) recommended CBT (in various forms) as a first-line psychological treatment for PTSD. EMDR was also included as a first-line psychological option in 43%of the guidelines (Phoenix, BAP, WHO, eTG, NICE and ISTSS). All guidelines except one (93%), AASM, which was specific to treating nightmares, recommended an SSRI as first-line pharmacological treatment for PTSD if pharmacological treatment was indicated. Some recommended SSRIs broadly, while others specifically recommended only paroxetine, fluoxetine or sertraline. Most guidelines (71%) also included the serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine as a first-line pharmacological treatment option. The WHO guideline also included tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as a first-line pharmacological recommendation.

Eight guidelines (57%) did not mention the targeted treatment of nightmares as a symptom of PTSD. Of the six guidelines (43%) that did mention targeted treatment, all mentioned prazosin as a potential option; although the strength of recommendations varied from no recommendation to first-line. Two guidelines (14%) also recommended IRT for targeted treatment of nightmares (AASM and APiA).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this review is the first study comparing international treatment guidelines for PTSD using a validated tool.

4.1. Quality of Guidelines

The AGREE II domains needing most attention were the critical ones of ‘applicability’, ‘rigour of development’ and ‘stakeholder involvement’. The Phoenix, APoA, WHO, NICE and VA guidelines received the highest scores across all domains (all >50%), while the ADAC and WFSBP guidelines received the lowest scores across all domains and were not recommended for use. Overall, guidelines scored well in the ‘scope and purpose’ and ‘clarity of presentation’ domains, consistently and clearly describing the guideline objectives and target populations. Scores in the stakeholder involvement domain varied. Low scores were generally due to a lack of information provided about the guideline development group members and/or a lack of consultation with patient representatives for their views and preferences.

No guidelines achieved a perfect score in the ‘rigour of development’ domain. While some guidelines scored highly, generally the external review process was missing entirely or lacked rigour. The SASOP guidelines scored particularly low in this domain, as the development process was not systematic. Each chapter was written by an expert or group of experts in the field, but there was no systematic evidence search described. However, this guideline was designed to be specific to a South African population, in which there is a lack of published evidence to review. Hence, a guideline based on experts’ clinical knowledge could be highly relevant, and still recommended for use despite low scores in some domains. All guidelines generally had lower scores in the applicability domain, while the editorial independence domain saw the greatest variance, with scores between 26–100%. Low scores in applicability were generally due to failure to identify barriers to implementation of the guidelines, as well as a lack of tools provided to aid implementation. In addition, very few guidelines performed economic evaluations to assess the potential resource implications of the application of their recommendations. While many guidelines scored highly in the ‘editorial independence’ domain, low scores were generally due to a lack of acknowledgement of the funding body or failure to state that no funding was received, highlighting a potential risk of bias in some guidelines.

The ‘rigour of development’ domain requires guideline developers to describe a procedure for updating the guideline. Seven guidelines (50%) described an intention for updates to occur. Some described a specific time interval (most commonly 5 years), while others stated updates were due only when new information becomes available. Interestingly, three of the remaining seven guidelines (50%) that did not describe an intention to update (BAP, ISTSS, VA) were updated versions of previous guidelines. While one could assume that one update means regular updates are planned, even updated guidelines should describe a procedure to be updated again, to remain valid. Of the seven guidelines (50%) that did describe an intention to be updated, two (eTG, WHO) are due for update based on the time interval they described. In addition, some guidelines that did not describe a time interval were likely to be due for update, although the ideal frequency of updates for clinical guidelines is unclear. A study by Shakelle et al. investigating how quickly clinical guidelines become outdated found that after 5.8 years, 50% of guidelines were no longer valid [ 40 ]. They concluded that all guidelines should generally be reassessed for validity at 3-year intervals [ 40 ]. However, a strict time interval recommendation is impractical in many cases, so the authors acknowledged that a 3-year interval will not always be suitable [ 40 ]. The evidence in certain fields is unlikely to change in 3 years, or even 10 years, while other rapidly evolving fields may require updates more frequently [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. However, when making the recommendation to update a guideline “when new information becomes available” there must be a robust procedure in place to ensure new information is found and included in a timely manner to maintain the validity of the guideline [ 42 ].

4.2. Recommendations in Guidelines

SSRIs are universally accepted as first-line pharmacological treatment of PTSD in clinical guidelines. The evidence is strongest for paroxetine and fluoxetine, as well as the SNRI venlafaxine which is also commonly recommended as a first-line pharmacological treatment for PTSD [ 43 ]. A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of pharmacological treatment for PTSD found statistically significant improvements in PTSD symptom severity with paroxetine, fluoxetine and venlafaxine, when compared to placebo, with effect sizes similar to those seen for antidepressants in depression, although it should be noted these effect sizes are relatively small [ 43 ]. When all SSRIs were grouped together and compared to placebo, a small positive effect size was seen; however, based on current evidence it seems that greater benefit would be seen using either paroxetine or fluoxetine over other SSRIs [ 43 ].

TCAs were also recommended as a first-line pharmacological option in the WHO guideline, although it should be noted that pharmacological options were not recommended first-line unless CBT and EMDR are unavailable, have failed or there is severe comorbid depression. The evidence for TCAs is considered inferior to SSRIs and venlafaxine in most guidelines, and adverse effects are of greater concern. However, a recent systematic review of pharmacotherapy for combat-related PTSD found TCAs to have similar efficacy to SSRIs and, as such, more research in this area may be warranted [ 44 ].

Around one third of guidelines recommended psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy for first-line treatment of PTSD. This recommendation is supported by a recent meta-analysis comparing the two treatment approaches head to head, which found significantly greater effect sizes for trauma-focused psychotherapies compared to medications for treating PTSD [ 45 ]. However, this recommendation will not be appropriate for all patients; for example, cost of treatment may be a crucial factor for the patient, appropriate psychotherapy may not be readily available to patients in rural areas, patients may have comorbidities such as depression which could benefit from medications, or they may simply prefer medication over psychotherapy. In these situations, clinicians must use clinical judgement to determine the most appropriate course of action for the patient.

All guidelines included in this review described CBT as the first-line psychological treatment for PTSD. CBT is a broad term that can encompass several specific therapies, such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure therapy (PE) and image rehearsal therapy (IRT), which have a focus on cognitive, behavioural and emotional processing techniques [ 46 ]. Several guidelines use the term ‘trauma-focused CBT’, which tends to encompass CBT as well as trauma-focused psychotherapies, such as EMDR. However, some guidelines recommended EMDR as a separate therapy, which can be confusing when comparing recommendations [ 45 ]. A recent meta-analysis comparing CBT to EMDR found that EMDR was slightly superior to CBT for intrusive and arousal symptoms, but found no significant difference between groups for avoidance symptoms [ 47 ]. In addition, a systematic review of CBT for PTSD found that specific trauma-focused therapies were all superior to supportive, non-trauma-focused therapies [ 46 ]. Based on these findings, it is reasonable for guidelines to use the broad term “trauma-focused psychotherapies”, which includes CBT, CPT, PE and EMDR, as they all have comparable evidence for safety and efficacy, and the use of this term may reduce confusion while allowing for flexibility in treatment selection.

Eight (57%) of the guidelines (APoA, CPA, eTG, ISTSS, NICE, Phoneix and WFSBP, WHO) did not address the targeted treatment of nightmares, despite the fact that nightmares are often resistant to treatment and are associated with a significantly increased suicide risk [ 9 , 11 , 12 ]. Prazosin is recommended as first-line treatment for nightmares in PTSD in two guidelines (ADAC and AASM) while others recommended it as third-line therapy or included no specific recommendation but discussed potential for its use. In addition, the guidelines that did address targeted treatment often lacked significant depth and detail in both the evidence search and clarity of recommendations when compared to their recommendations for core PTSD symptoms. Three recently published meta-analyses investigating the efficacy of prazosin for PTSD nightmares found prazosin to be significantly more effective than placebo in reducing trauma-related nightmares [ 3 , 10 , 48 ]. These findings were based on improvements in the clinician-administered PTSD scale (CAPS) “distressing dreams item”, which is a measure of both the frequency and intensity of nightmares. Improvements were statistically significant and of large magnitude based on Cohen’s convention [ 3 , 10 , 48 ]. They did, however, highlight some important limitations, namely, small sample sizes and a lack of variability in both the research groups and participants, who were overwhelmingly male, combat veterans. Additionally, two more recent RCTs [ 49 , 50 ], not included in these meta-analyses, with relatively larger sample sizes, found no significant difference between prazosin and placebo in improving the CAPS distressing dreams item, or for any other primary outcome measures. While earlier positive trials for prazosin did not exclude participants with psychosocial instability, both negative studies excluded these patients. It is postulated that prazosin may only be effective in a sub-group of patients experiencing more severe adrenergic dysfunction, who may have been excluded from the negative studies [ 50 , 51 ]. While further research in this area is required, it remains important that guidelines consider the targeted treatment of nightmares in PTSD. Two guidelines also recommended IRT for targeted treatment of nightmares in PTSD. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis comparing IRT to prazosin found IRT to be equally effective as prazosin in treating nightmares in PTSD [ 14 ]. The most effective treatment, however, was IRT in combination with CBT for insomnia, which showed significant improvement in sleep quality when compared to prazosin or IRT alone ( p = 0.03] [ 14 ]. It should be noted that there were significantly more trials investigating IRT than prazosin, and these included larger and more variable cohorts of participants, suggesting that the evidence for IRT is more robust than that for prazosin, yet IRT is recommended less frequently in treatment guidelines [ 14 ].

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this review include the use of the AGREE II criteria to assess the quality of each identified guideline, the development of a systematic method to search grey literature for guidelines, and a focus on the targeted treatment of nightmares. The AGREE II criteria is a validated assessment tool, which has been used in several similar systematic reviews of treatment guidelines in the area of mental health treatment [ 52 , 53 , 54 ]. It is also acknowledged that assessment using the AGREE II criteria can be relatively subjective, with no pre-defined cut-off scores.

Many systematic reviews of treatment guidelines do not clearly describe the method by which grey literature was searched to locate guidelines, or do not describe a systematic method that could be repeated by other researchers. Often, guidelines are not published in journals, and instead are posted on the webpages of the author organisation, or in guideline repositories, meaning that grey literature searches should form a major part of the search process [ 55 ]. Our grey literature search method was unique, transparent and systematic, and could be repeated by other researchers for future systematic reviews of treatment guidelines in any area of health care. This review also had a strong focus on the treatment of nightmares in PTSD, which are often resistant to general PTSD treatments [ 9 ]. Critical appraisal of the guidelines highlighted a lack of information about the targeted treatment of nightmares, despite the availability and importance of such treatments. A limitation of this review is the restriction to guidelines written in the English language, and although our method for searching the grey literature was highly systematic, it remains possible that eligible guidelines could have been missed.

5. Conclusions

There are a plethora of treatment guidelines being produced world-wide to aid health professionals in clinical decision making. However, it is important for health professionals to be able to identify which guidelines can be the most trusted. This review assessed the quality of international treatment guidelines for PTSD. We identified that many PTSD guidelines could be considered out of date require improvement in the AGREE II key domains of ‘applicability’, ‘rigour of development’ and ‘stakeholder involvement’. We have also highlighted a significant lack of information regarding the targeted treatment of nightmares, despite the availability of both psychological and pharmacological treatments. Due to the treatment-resistant nature of nightmares in PTSD and significantly increased risk of suicide, guideline development groups should consider producing more detailed recommendations for their treatment. In part, this is dependent on the availability of a solid evidence base if making specific treatment suggestions. Therefore, there is a need for more well-designed RCTs to establish the true clinical efficacy of targeted treatments for nightmares in PTSD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N., S.K., J.T., A.M.; methodology, M.N., S.K., J.T. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M., J.K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.N., S.K., G.P., J.T. and J.K.C.; supervision, M.N., S.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Open access

- Published: 28 September 2018

Posttraumatic stress disorder: from diagnosis to prevention

- Xue-Rong Miao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0665-8271 1 ,

- Qian-Bo Chen 1 ,

- Kai Wei 1 ,

- Kun-Ming Tao 1 &

- Zhi-Jie Lu 1

Military Medical Research volume 5 , Article number: 32 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

54k Accesses

43 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic impairment disorder that occurs after exposure to traumatic events. This disorder can result in a disturbance to individual and family functioning, causing significant medical, financial, and social problems. This study is a selective review of literature aiming to provide a general outlook of the current understanding of PTSD. There are several diagnostic guidelines for PTSD, with the most recent editions of the DSM-5 and ICD-11 being best accepted. Generally, PTSD is diagnosed according to several clusters of symptoms occurring after exposure to extreme stressors. Its pathogenesis is multifactorial, including the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, immune response, or even genetic discrepancy. The morphological alternation of subcortical brain structures may also correlate with PTSD symptoms. Prevention and treatment methods for PTSD vary from psychological interventions to pharmacological medications. Overall, the findings of pertinent studies are difficult to generalize because of heterogeneous patient groups, different traumatic events, diagnostic criteria, and study designs. Future investigations are needed to determine which guideline or inspection method is the best for early diagnosis and which strategies might prevent the development of PTSD.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a recognized clinical phenomenon that often occurs as a result of exposure to severe stressors, such as combat, natural disaster, or other events [ 1 ]. The diagnosis of PTSD was first introduced in the 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association) in 1980 [ 2 ].

PTSD is a potentially chronic impairing disorder that is characterized by re-experience and avoidance symptoms as well as negative alternations in cognition and arousal. This disease first raised public concerns during and after the military operations of the United States in Afghanistan and Iraq, and to date, a large number of research studies report progress in this field. However, both the underlying mechanism and specific treatment for the disease remain unclear. Considering the significant medical, social and financial problems, PTSD represents both to nations and to individuals, all persons caring for patients suffering from this disease or under traumatic exposure should know about the risks of PTSD.

The aim of this review article is to present the current understanding of PTSD related to military injury to foster interdisciplinary dialog. This article is a selective review of pertinent literature retrieved by a search in PubMed, using the following keywords: “PTSD[Mesh] AND military personnel”. The search yielded 3000 publications. The ones cited here are those that, in the authors’ view, make a substantial contribution to the interdisciplinary understanding of PTSD.

Definition and differential diagnosis

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a prevalent and typically debilitating psychiatric syndrome with a significant functional disturbance in various domains. Both the manifestation and etiology of it are complex, which has caused difficulty in defining and diagnosing the condition. The 3rd edition of the DSM introduced the diagnosis of PTSD with 17 symptoms divided into three clusters in 1980. After several decades of research, this diagnosis was refined and improved several times. In the most recent version of the DSM-5 [ 3 ], PTSD is classified into 20 symptoms within four clusters: intrusion, active avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood as well as marked alterations in arousal and reactivity. The diagnosis requirement can be summarized as an exposure to a stressor that is accompanied by at least one intrusion symptom, one avoidance symptom, two negative alterations in cognitions and mood symptoms, and two arousal and reactivity turbulence symptoms, persisting for at least one month, with functional impairment. Interestingly, in the DSM-5, PTSD has been moved from the anxiety disorder group to a new category of ‘trauma- and stressor-related disorders’, which reflects the cognizance alternation of PTSD. In contrast to the DSM versions, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) has proposed a substantially different approach to diagnosing PTSD in the most recent ICD-11 version [ 4 ], which simplified the symptoms into six under three clusters, including constant re-experiencing of the traumatic event, avoidance of traumatic reminders and a sense of threat. The diagnosis requires at least one symptom from each cluster which persists for several weeks after exposure to extreme stressors. Both diagnostic guidelines emphasize the exposure to traumatic events and time of duration, which differentiate PTSD from some diseases with similar symptoms, including adjustment disorder, anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and personality disorder. Patients with the major depressive disorder (MDD) may or may not have experienced traumatic events, but generally do not have the invasive symptoms or other typical symptoms that PTSD presents. In terms of traumatic brain injury (TBI), neurocognitive responses such as persistent disorientation and confusion are more specific symptoms. It is worth mentioning that some dissociative reactions in PTSD (e.g., flashback symptoms) should be recognized separately from the delusions, hallucinations, and other perceptual impairments that appear in psychotic disorders since they are based on actual experiences. The ICD-11 also recognizes a sibling disorder, complex PTSD (CPTSD), composed of symptoms including dysregulation, negative self-concept, and difficulties in relationships based on the diagnosis of PTSD. The core CPTSD symptom is PTSD with disturbances in self-organization (DSO).

In consideration of the practical applicability of the PTSD diagnosis, Brewin et al. conducted a study to investigate the requirement differences, prevalence, comorbidity, and validity of the DSM-5 and ICD-11 for PTSD criteria. According to their study, diagnostic standards for symptoms of re-experiencing are higher in the ICD-11 than the DSM, whereas the standards for avoidance are less strict in the ICD-11 than in the DSM-IV [ 5 ]. It seems that in adult subjects, the prevalence of PTSD using the ICD-11 is considerably lower compared to the DSM-5. Notably, evidence suggested that patients identified with the ICD-11 and DSM-5 were quite different with only partially overlapping cases; this means each diagnostic system appears to find cases that would not be diagnosed using the other. In consideration of comorbidity, research comparing these two criteria show diverse outcomes, as well as equal severity and quality of life. In terms of children, only very preliminary evidence exists suggesting no significant difference between the two. Notably, the diagnosis of young children (age ≤ 6 years) depends more on the situation in consideration of their physical and psychological development according to the DSM-5.

Despite numerous investigations and multiple revisions of the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, it remains unclear which type and what extent of stress are capable of inducing PTSD. Fear responses, especially those related to combat injury, are considered to be sufficient enough to trigger symptoms of PTSD. However, a number of other types of stressors were found to correlate with PTSD, including shame and guilt, which represent moral injury resulting from transgressions during a war in military personnel with deeply held moral and ethical beliefs. In addition, military spouses and children may be as vulnerable to moral injury as military service members [ 6 ]. A research study on Canadian Armed Forces personnel showed that exposure to moral injury during deployments is common among military personnel and represents an independent risk factor for past-year PTSD and MDD [ 7 ]. Unfortunately, it seems that pre- and post-deployment mental health education was insufficient to moderate the relationship between exposure to moral injury and adverse mental health outcomes.

In general, a large number of studies are focusing on the definition and diagnostic criteria of PTSD and provide considerable indicators for understanding and verifying the disease. However, some possible limitations or discrepancies continue to exist in current research studies. One is that although the diagnostic criteria for a thorough examination of the symptoms were explicit and accessible, the formal diagnosis of PTSD using structured clinical interviews was relatively rare. In contrast, self-rating scales, such as the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) [ 8 ] and the Impact of Events Scale (IES) [ 9 ], were used frequently. It is also noteworthy that focusing on PTSD explicitly could be a limitation as well. The complexity of traumatic experiences and the responses to them urge comprehensive investigations covering all aspects of physical and psychological maladaptive changes.

Prevalence and importance

Posttraumatic stress disorder generally results in poor individual-level outcomes, including co-occurring disorders such as depression and substance use, and physical health problems. According to the DSM-5 reporting, more than 80% of PTSD patients share one or more comorbidities; for instance, the morbidity of PTSD with concurrent mild TBI is 48% [ 8 ]. Moreover, cognitive impairment has been identified frequently in PTSD. The reported incidence rate for PTSD ranges from 5.4 to 16.8% in military service members and veterans [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ], which is almost double those in the general population. The estimated prevalence of PTSD varies depending on the group of patients studied, the traumatic events occurred, and the measurement method used (Table 1 ). However, it still reflects the profound effect of this mental disease, especially with the rise in global terrorism and military conflict in recent years. While PTSD can arise at any life stage in any population, most research in recent decades has focused on returned veterans; this means most knowledge regarding PTSD has come from the military population. Meanwhile, the impact of this disease on children has received scant attention.

The discrepancy of PTSD prevalence in males and females is controversial. In a large study of OEF/OIF veterans, the prevalence of PTSD in males and females was similar, although statistically more prevalent in men versus women (13% vs. 11%) [ 15 ]. Another study on the Navy and Marine Corps showed a slightly higher incidence for PTSD in the women compared to men (6.6% vs. 5.3%) [ 12 ]. However, the importance of combat exposure is unclear. Despite a lower level of combat exposure than male military personnel, females generally have considerably higher rates of military sexual trauma, which is significantly associated with the development of PTSD [ 16 ].

It is reported that 44–72% of veterans suffer high levels of stress after returning to civilian life. Many returned veterans with PTSD show emotion regulation problems, including emotion identification, expression troubles and self-control issues. Nevertheless, a meta-analytic investigation of 34 studies consistently found that the severity of PTSD symptoms was significantly associated with anger, especially in military samples [ 17 ]. Not surprisingly, high levels of PTSD and emotional regulation troubles frequently lead to poor family functioning or even domestic violence in veterans. According to some reports, parenting difficulties in veteran families were associated with three PTSD symptom clusters. Evans et al. [ 18 ] conducted a survey to evaluate the impact of PTSD symptom clusters on family functioning. According to their analysis, avoidance symptoms directly affected family functioning, whereas hyperarousal symptoms had an indirect association with family functioning. Re-experience symptoms were not found to impact family functioning. Notably, recent epidemiologic studies using data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) reported that veterans with PTSD were linked to suicide ideations and behaviors [ 19 ] (e.g., non-suicidal self-injury, NSSI), in which depression as well as other mood disruptions, often serve as mediating factors.

Previously, there was a controversial attitude toward the vulnerability of young children to PTSD. However, growing evidence suggests that severe and persistent trauma could result in stress responses worse than expected as well as other mental and physical sequelae in child development. The most prevalent traumatic exposures for young children above the age of 1 year were interpersonal trauma, mostly related to or derived from their caregivers, including witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) and maltreatment [ 20 ]. Unfortunately, because of the crucial role that caregivers play in early child development, these types of traumatic events are especially harmful and have been associated with developmental maladaptation in early childhood. Maladaptation commonly represents a departure from normal development and has even been linked to more severe effects and psychopathology. In addition, the presence of psychopathology may interfere with the developmental competence of young children. Research studies have also broadened the investigation to sequelae of PTSD on family relationships. It is proposed that the children of parents with symptoms of PTSD are easily deregulated or distressed and appear to face more difficulties in their psychosocial development in later times compared to children of parents without. Meanwhile, PTSD veterans described both emotional (e.g., hurt, confusion, frustration, fear) and behavioral (e.g., withdrawal, mimicking parents’ behavior) disruption in their children [ 21 ]. Despite the increasing emphasis on the effects of PTSD on young children, only a limited number of studies examined the dominant factors that influence responses to early trauma exposures, and only a few prospective research studies have observed the internal relations between early PTSD and developmental competence. Moreover, whether exposure to both trauma types in early life is associated with more severe PTSD symptoms than exposure to one type remains an outstanding question.

Molecular mechanism and predictive factors

The mechanisms leading to posttraumatic stress disorder have not yet been fully elucidated. Recent literature suggests that both the neuroendocrine and immune systems are involved in the formulation and development of PTSD [ 22 , 23 ]. After traumatic exposures, the stress response pathways of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system are activated and lead to the abnormal release of glucocorticoids (GC) and catecholamines. GCs have downstream effects on immunosuppression, metabolism enhancement, and negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis by binding to the GC receptor (GR), thus connecting the neuroendocrine modulation with immune disturbance and inflammatory response. A recent meta-analysis of 20 studies found increased plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a), interleukin-1beta (IL-1b), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in individuals with PTSD compared to healthy controls [ 24 ]. In addition, some other studies speculate that there is a prospective association of C-reactive protein (CRP) and mitogen with the development of PTSD [ 25 ]. These findings suggest that neuroendocrine and inflammatory changes, rather than being a consequence of PTSD, may in fact act as a biological basis and preexisting vulnerability for developing PTSD after trauma. In addition, it is reported that elevated levels of terminally differentiated T cells and an altered Th1/Th2 balance may also predispose an individual to PTSD.

Evidence indicates that the development of PTSD is also affected by genetic factors. Research has found that genetic and epigenetic factors account for up to 70% of the individual differences in PTSD development, with PTSD heritability estimated at 30% [ 26 ]. While aiming to integrate genetic studies for PTSD and build a PTSD gene database, Zhang et al. [ 27 ] summarized the landscape and new perspective of PTSD genetic studies and increased the overall candidate genes for future investigations. Generally, the polymorphisms moderating HPA-axis reactivity and catecholamines have been extensively studied, such as FKBP5 and catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT). Other potential candidates for PTSD such as AKT, a critical mediator of growth factor-induced neuronal survival, were also explored. Genetic research has also made progress in other fields. For example, researchers have found that DNA methylation in multiple genes is highly correlated with PTSD development. Additional studies have found that stress exposure may even affect gene expression in offspring by epigenetic mechanisms, thus causing lasting risks. However, some existing problems in the current research of this field should be noted. In PTSD genetic studies, variations in population or gender difference, a wide range of traumatic events and diversity of diagnostic criteria all may attribute to inconsistency, thus leading to a low replication rate among similar studies. Furthermore, PTSD genes may overlap with other mental disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. All of these factors indicate an urgent need for a large-scale genome-wide study of PTSD and its underlying epidemiologic mechanisms.

It is generally acknowledged that some mental diseases, such as major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, are associated with massive subcortical volume change. Recently, numerous studies have examined the relationship between the morphology changes of subcortical structures and PTSD. One corrected analysis revealed that patients with PTSD show a pattern of lower white matter integrity in their brains [ 28 ]. Prior studies typically found that a reduced volume of the hippocampus, amygdala, rostral ventromedial prefrontal cortex (rvPFC), dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), and the caudate nucleus may have a relationship with PTSD patients. Logue et al. [ 29 ] conducted a large neuroimaging study of PTSD that compared eight subcortical structure volumes (nucleus accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, pallidum, putamen, thalamus, and lateral ventricle) between PTSD patients and controls. They found that smaller hippocampi were particularly associated with PTSD, while smaller amygdalae did not show a significant correlation. Overall, rigorous and longitudinal research using new technologies, such as magnetoencephalography, functional MRI, and susceptibility-weighted imaging, are needed for further investigation and identification of morphological changes in the brain after a traumatic exposure.

Psychological and pharmacological strategies for prevention and treatment

Current approaches to PTSD prevention span a variety of psychological and pharmacological categories, which can be divided into three subgroups: primary prevention (before the traumatic event, including prevention of the event itself), secondary prevention (between the traumatic event and the development of PTSD), and tertiary prevention (after the first symptoms of PTSD become apparent). The secondary and tertiary prevention of PTSD has abundant methods, including different forms of debriefing, treatments for Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) or acute PTSD, and targeted intervention strategies. Meanwhile, the process of primary prevention is still in its infancy and faces several challenges.

Based on current research on the primary prevention of post-trauma pathology, psychological and pharmacological interventions for particular groups or individuals (e.g., military personnel, firefighters, etc.) with a high risk of traumatic event exposure were applicable and acceptable for PTSD sufferers. Of the studies that reported possible psychological prevention effects, training generally included a psychoeducational component and a skills-based component relating to stress responses, anxiety reducing and relaxation techniques, coping strategies and identifying thoughts, emotion and body tension, choosing how to act, attentional control, emotion control and regulation [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. However, efficiency for these training has not been evaluated yet due to a lack of high-level evidence-based studies. Pharmacological options have targeted the influence of stress on memory formation, including drugs relating to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the autonomic nerve system (especially the sympathetic nerve system), and opiates. Evidence has suggested that pharmacological prevention is most effective when started before and early after the traumatic event, and it seems that sympatholytic drugs (alpha and beta-blockers) have the highest potential for primary prevention of PTSD [ 33 ]. However, one main difficulty limiting the exploration in this field is related to rigorous and complex ethical issues, as the application of pre-medication for special populations and the study of such options in hazardous circumstances possibly touches upon questions of life and death. Significantly, those drugs may have potential side effects.

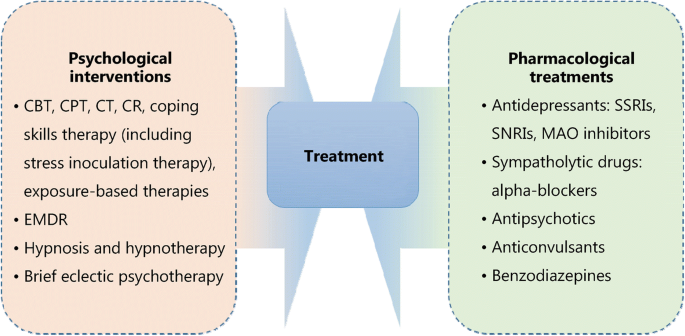

There are several treatment guidelines for patients with PTSD produced by different organizations, including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (VA, DoD) [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Additionally, a large number of research studies are aiming to evaluate an effective treatment method for PTSD. According to these guidelines and research, treatment approaches can be classified as psychological interventions and pharmacological treatments (Fig. 1 ); most of the studies provide varying degrees of improvement in individual outcomes after standard interventions, including PTSD symptom reduction or remission, loss of diagnosis, release or reduction of comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions, quality of life, disability or functional impairment, return to work or to active duty, and adverse events.

Psychological and pharmacological strategies for treatment of PTSD. CBT. Cognitive behavioral therapy; CPT. Cognitive processing therapy; CT. Cognitive therapy; CR. Cognitive restructuring; EMDR. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; SSRIs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs. Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; MAO. Monoamine oxidase

Most guidelines identify trauma-focused psychological interventions as first-line treatment options [ 39 ], including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), cognitive therapy (CT), cognitive restructuring (CR), coping skills therapy (including stress inoculation therapy), exposure-based therapies, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), hypnosis and hypnotherapy, and brief eclectic psychotherapy. These treatments are delivered predominantly to individuals, but some can also be conducted in family or group settings. However, the recommendation of current guidelines seems to be projected empirically as research on the comparison of outcomes of different treatments is limited. Jonas et al. [ 40 ] performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis of the evidence for treatment of PTSD. The study suggested that all psychological treatments showed efficacy for improving PTSD symptoms and achieving the loss of PTSD diagnosis in the acute phase, and exposure-based treatments exhibited the strongest evidence of efficacy with high strength of evidence (SOE). Furthermore, Kline et al. [ 41 ] conducted a meta-analysis evaluating the long-term effects of in-person psychotherapy for PTSD in 32 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 2935 patients with long-term follow-ups of at least 6 months. The data suggested that all studied treatments led to lasting improvements in individual outcomes, and exposure therapies demonstrated a significant therapeutic effect as well with larger effect sizes compared to other treatments.

Pharmacological treatments for PTSD include antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, sympatholytic drugs such as alpha-blockers, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines. Among these medications, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, topiramate, risperidone, and venlafaxine have been identified as efficacious in treatment. Moreover, in the Jonas network meta-analysis of 28 trials (4817 subjects), they found paroxetine and topiramate to be more effective for reducing PTSD symptoms than most other medications, whereas evidence was insufficient for some other medications as research was limited [ 40 ]. It is worth mentioning that in these studies, efficacy for the outcomes, unlike the studies of psychological treatments, was mostly reported as a remission in PTSD or depression symptoms; other outcomes, including loss of PTSD diagnosis, were rarely reported in studies.

As for the comparative evidence of psychological with pharmacological treatments or combinations of psychological treatments and pharmacological treatments with other treatments, evidence was insufficient to draw any firm conclusions [ 40 ]. Additionally, reports on adverse events such as mortality, suicidal behaviors, self-harmful behaviors, and withdrawal of treatment were relatively rare.

PTSD is a high-profile clinical phenomenon with a complicated psychological and physical basis. The development of PTSD is associated with various factors, such as traumatic events and their severity, gender, genetic and epigenetic factors. Pertinent studies have shown that PTSD is a chronic impairing disorder harmful to individuals both psychologically and physically. It brings individual suffering, family functioning disorders, and social hazards. The definition and diagnostic criteria for PTSD remain complex and ambiguous to some extent, which may be attributed to the complicated nature of PTSD and insufficient research on it. The underlying mechanisms of PTSD involve changes in different levels of psychological and molecular modulations. Thus, research targeting the basic mechanisms of PTSD using standard clinical guidelines and controlled interference factors is needed. In terms of treatment, psychological and pharmacological interventions could relief PTSD symptoms to different degrees. However, it is necessary to develop systemic treatment as well as symptom-specific therapeutic methods. Future research could focus on predictive factors and physiological indicators to determine effective prevention methods for PTSD, thereby reducing its prevalence and preventing more individuals and families from struggling with this disorder.

Abbreviations

American Psychiatric Association

Acute stress disorder

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Catechol-O-methyl-transferase

Cognitive processing therapy

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder

Cognitive restructuring

C-reactive protein

Cognitive therapy

Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Disturbances in self-organization

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids receptor

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

International classification of diseases

Impact of events scale

Interleukin-1beta

Interleukin-6

Institute of Medicine

Intimate partner violence

International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

Monoamine oxidase

Major depressive disorder

United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

Non-suicidal self-injury

Posttraumatic diagnostic scale

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Randomized controlled trials

Rostral ventromedial prefrontal cortex

Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors;

Strength of evidence

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

DoD Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense

Veterans Health Administration

World Health Organization

White J, Pearce J, Morrison S, Dunstan F, Bisson JI, Fone DL. Risk of post-traumatic stress disorder following traumatic events in a community sample. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(3):1–9.

Article Google Scholar

Kendell RE. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd ed., revised (DSM-III-R). America J Psychiatry. 1980;145(10):1301–2.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. America J Psychiatry. 2013. doi: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 .

Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Cloitre M, Reed GM, Van OM, et al. Proposals for mental disorders specifically associated with stress in the international classification of Diseases-11. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1683–5.

Brewin CR, Cloitre M, Hyland P, Shevlin M, Maercker A, Bryant RA, et al. A review of current evidence regarding the ICD-11 proposals for diagnosing PTSD and complex PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58(1): 1–15.

Google Scholar

Nash WP, Litz BT. Moral injury: a mechanism for war-related psychological trauma in military family members. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16(4):365–75.

Nazarov A, Fikretoglu D, Liu A, Thompson M, Zamorski MA. Greater prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in deployed Canadian Armed Forces personnel at risk for moral injury. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137(4):342–54.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol Assess. 1997;9(9):445–51.

Gnanavel S, Robert RS. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edit) and the impact of events scale-revised. Chest. 2013;144(6):1974–5.

Reijnen A, Rademaker AR, Vermetten E, Geuze E. Prevalence of mental health symptoms in Dutch military personnel returning from deployment to Afghanistan: a 2-year longitudinal analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):341–6.

Sundin J, Herrell RK, Hoge CW, Fear NT, Adler AB, Greenberg N, et al. Mental health outcomes in US and UK military personnel returning from Iraq. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(3):200–7.

Macera CA, Aralis HJ, Highfill-McRoy R, Rauh MJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder after combat zone deployment among navy and marine corps men and women. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(6):499–505.

Macgregor AJ, Tang JJ, Dougherty AL, Galarneau MR. Deployment-related injury and posttraumatic stress disorder in US military personnel. Injury. 2013;44(11):1458–64.

Sandweiss DA, Slymen DJ, Leardmann CA, Smith B, White MR, Boyko EJ, et al. Preinjury psychiatric status, injury severity, and postdeployment posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):496–504.

Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Gima K, Chu A, Marmar CR. Getting beyond "Don't ask; don't tell": an evaluation of US veterans administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):714–20.

Street AE, Rosellini AJ, Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Hill ED, Monahan J, et al. Developing a risk model to target high-risk preventive interventions for sexual assault victimization among female U.S. army soldiers. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4(6):939–56.

Olatunji BO, Ciesielski BG, Tolin DF. Fear and loathing: a meta-analytic review of the specificity of anger in PTSD. Behav Ther. 2010;41(1):93–105.

Evans L, Cowlishaw S, Hopwood M. Family functioning predicts outcomes for veterans in treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23(4):531–9.

Mckinney JM, Hirsch JK, Britton PC. PTSD symptoms and suicide risk in veterans: serial indirect effects via depression and anger. J Affect Disord. 2017;214(1):100–7.

Briggsgowan MJ, Carter AS, Ford JD. Parsing the effects violence exposure in early childhood: modeling developmental pathways. J Pediatric Psychol. 2012;37(1):11–22.

Enlow MB, Blood E, Egeland B. Sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms in young children exposed to interpersonal trauma in early life. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(6):686–94.

Newport DJ, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Opin eurobiol. 2009;14(1 Suppl 1):13.

Neigh GN, Ali FF. Co-morbidity of PTSD and immune system dysfunction: opportunities for treatment. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;29:104–10.

Passos IC, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Costa LG, Kunz M, Brietzke E, Quevedo J, et al. Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1002.

Eraly SA, Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Barkauskas DA, Biswas N, Agorastos A, et al. Assessment of plasma C-reactive protein as a biomarker of posttraumatic stress disorder risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):423.

Lebois LA, Wolff JD, Ressler KJ. Neuroimaging genetic approaches to posttraumatic stress disorder. Exp Neurol. 2016;284(Pt B):141–52.

Zhang K, Qu S, Chang S, Li G, Cao C, Fang K, et al. An overview of posttraumatic stress disorder genetic studies by analyzing and integrating genetic data into genetic database PTSD gene. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83(1):647–56.

Bolzenius JD, Velez CS, Lewis JD, Bigler ED, Wade BSC, Cooper DB, et al. Diffusion imaging findings in US service members with mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000378 [Epub ahead of print].

Logue MW, Rooij SJHV, Dennis EL, Davis SL, Hayes JP, Stevens JS, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a multi-site ENIGMA-PGC study. Biol. Psychiatry . 2018;83(3):244–53.

Sijaric-Voloder S, Capin D. Application of cognitive behavior therapeutic techniques for prevention of psychological disorders in police officers. Health Med. 2008;2(4):288–92.

Deahl M, Srinivasan M, Jones N, Thomas J, Neblett C, Jolly A. Preventing psychological trauma in soldiers: the role of operational stress training and psychological debriefing. Brit J Med Psychol. 2000;73(1):77–85.

Wolmer L, Hamiel D, Laor N. Preventing children's posttraumatic stress after disaster with teacher-based intervention: a controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(4):340–8 348.e1–2.

Skeffington PM, Rees CS, Kane R. The primary prevention of PTSD: a systematic review. J Trauma Dissociation. 2013;14(4):404–22.

Jaques H. Introducing the national institute for health and clinical excellence. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(17):2111–2.

PubMed Google Scholar

Schnyder U. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). Psychosomatik Und Konsiliarpsychiatrie. 2008;2(4):261.

Bulger RE. The institute of medicine. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1992;2(1):73–7.

Anderle R, Brown DC, Cyran E. Department of Defense[C]. African Studies Association. 2011;2011:340–2.

Feussner JR, Maklan CW. Department of Veterans Affairs[J]. Med Care. 1998;36(3):254–6.

Sripada RK, Rauch SA, Liberzon I. Psychological mechanisms of PTSD and its treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(11):99.

Jonas DE, Cusack K, Forneris CA, Wilkins TM, Sonis J, Middleton JC, et al. Psychological and pharmacological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Agency Healthcare Res Quality (AHRQ). 2013;4(1):1–760.

Kline AC, Cooper AA, Rytwinksi NK, Feeny NC. Long-term efficacy of psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:30–40.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Jamie Bono for providing professional writing suggestions.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371084 and 31171013 by ZJL), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81100276 by XRM).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Third Affiliated Hospital of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China

Xue-Rong Miao, Qian-Bo Chen, Kai Wei, Kun-Ming Tao & Zhi-Jie Lu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ZJL and XRM conceived the project. QBC, KW and KMT conducted the article search and acquisition. XRM and QBC analyzed the data. XRM wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and discussed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xue-Rong Miao .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Miao, XR., Chen, QB., Wei, K. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from diagnosis to prevention. Military Med Res 5 , 32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-018-0179-0

Download citation

Received : 20 March 2018

Accepted : 10 September 2018

Published : 28 September 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-018-0179-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive impairment

- Psychological interventions

- Neuroendocrine

Military Medical Research

ISSN: 2054-9369

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Breakthrough Study on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

A collaboration of researchers, institutions and databases makes advances on the understanding of the genetic component of ptsd.

- Joseph McClain - [email protected]

Media contact:

- Miles Martin - [email protected]

Published Date

Share this:, article content.

The Psychiatric Genetics Consortium (PGC), a consortium of researchers led by scientists at University of California San Diego School of Medicine has made significant advancements in the understanding of the neurobiology of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition the World Health Organization says affects some 250 million people around the world.

The group recently announced their findings from a genome-wide association study of 1,222,822 people in a paper recently published in the journal Nature Genetics .

Caroline M. Nievergelt, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego School of Medicine, is the co-first author on the paper, together with Adam X. Maihofer, PhD., an assistant project scientist in Nievergelt’s lab. PGC-PTSD co-chair Murray B. Stein M.D., M.P.H., professor of psychiatry and public health at UC San Diego is also a co-author of the study.

Nievergelt explained that the work confirmed previous neurobiological studies of PTSD and built upon them, identifying 95 loci — positions of genes on a chromosome — significant to PTSD, including 80 new loci.

“As the number of samples has increased, we have gained a better understanding of the genetic factors that contribute to PTSD risk,” Stein said.

The paper underscores the importance of heritability in PTSD risk and notes that the identified genes influence processes related to PTSD symptoms such as stress, fear and threat responses. She said their findings also point to possible associations among PTSD and other mental and physical disorders.

The PGC was formed in 2007, dedicated to finding genes that predispose an individual to psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, Nievergelt said. She added that each disorder is addressed by one of 11 working groups, one of which is the PGC for PTSD, which she chairs.

Nievergelt explained that the benefits of research by a consortium extend beyond the hive-mind input of numerous collaborators working toward a common goal. A genome-wide association study (GWAS) examines and compares genomes of a large number of people in a search for genetic markers associated with a specific condition. A GWAS for polygenic disorders such as PTSD necessarily requires an enormous sample size, she noted.

“And no one PI (principal investigator) is able to get nearly enough subjects for a genome-wide association study, so through the consortium we have a large number of collaborators combining data from all over the world,” Nievergelt said.

The PCG for PTSD consortium includes researchers from a wide number of research institutions and universities worldwide. Notable participants include co-chairs Karestan Koenen, Ph.D., from the Harvard Chan School of Public Health and the Broad Institute of MIT, and Kerry Ressler, M.D., Ph.D., of Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital.

{/exp:typographee}

The brain, DNA, and a fractured glass effect as a PTSD metaphor. Photo by Adobe AI.

The consortium’s database was assembled from various sources, representing a variety of causes and levels of trauma. Nievergelt said the sources included the Marine Resiliency Study, in which U.S. Marine Corps members were assessed before and after going to war, and Army STARRS, a longitudinal study of U.S. Army soldiers. Another is the Grady Trauma Project that includes victims of violent crime, mostly African American individuals from inner cities. Other datasets incorporated into the PGC for PTSD megadata list came from Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and the VA Million Veterans Program. The consortium also incorporated data from Europe and Latin America.

At an appropriate stage, the consortium members agree on a data freeze and begin their examination, seeking to identify specific genes likely to be associated with PTSD. The paper represents “a milestone” in the understanding of the genetic component of PTSD, Nievergelt said.

“It’s the first time that we actually have a very strong genetic signal,” said Maihofer, who analyzed the data. The genetic signal — essentially a mapping of RNA or DNA activity relevant to PTSD — allowed the consortium to pinpoint specific genes and analyze pathways of gene expression for future research or even for eventual treatment strategies, Maihofer explained.

Nievergelt says there are several directions the consortium wants to take in terms of next steps. One is to increase and diversify the sample size. She said the group has received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health to go to Africa and enroll African people in the genetics study, an effort lead by co-chair Koenen. “That will help us improve risk prediction for other people of African ancestry, a group that has been relatively neglected in earlier studies,” Nievergelt noted.

UC San Diego co-authors

Authors affiliated with the University of California San Diego School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry, in addition to first authors Caroline M. Nievergelt and Adam X. Maihofer, are: Dewleen G. Baker, Carol E. Franz, William S. Kremen, Elizabeth A. Mikita, Sonya B. Norman, Matthew S. Panizzon and Murray B. Stein, also affiliated with the UCSD Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science. Other UC San Diego authors are Anders M. Dale, of the Department of Radiology, Department of Neurosciences, and Wesley K. Thompson, of the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science.

Other noteworthy participants in the study

PGC-PTSD co-chairs:

Kerry J. Ressler, of the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School; McLean Hospital, and Department of Medicine (Biomedical Genetics), Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine; as well as Karestan C. Koenen, of the Department of Epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research; and McLean Hospital Developmental Biopsychiatry Research Program.

Writing group members are:

Elizabeth G. Atkinson, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine; Chia-Yen Chen, Biogen Inc.,Translational Sciences; Karmel W. Choi, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital; Jonathan R. I. Coleman, King’s College London, National Institute for Health and Care Research Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre, and King’s College London, Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience; Nikolaos P. Daskalakis, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research in the Department of Psychiatry of Harvard Medical School, and the McLean Hospital, Center of Excellence in Depression and Anxiety Disorders; Laramie E. Duncan, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University; Renato Polimanti, VA Connecticut Healthcare Center, and the Department of Psychiatry of Yale University School of Medicine.

Competing interest