An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.11(10); 2019 Oct

Classical Presentation of Acute Appendicitis in the Case of a Subhepatic Appendix

Simran k longani.

1 Medicine, Imperial College London, London, GBR

Ahmed Ahmed

2 Upper Gastrointestinal and Bariatric Surgery, Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust, London, GBR

Acute appendicitis is a very common surgical emergency diagnosed by combining the history, examination, and investigations to build a clinical picture. This presentation can become more complex with abnormal anatomical variations of the appendix. This case describes the rare clinical finding of a subhepatically located appendix and caecum in a 24-year-old female presenting with right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain. Examination findings were consistent with acute appendicitis. Ultrasonography identified the appendix as being located in the subhepatic region with laparoscopy confirming this finding and the presence of a malrotated caecal pole due to congenital adhesions. Laparoscopic appendectomy was subsequently performed therapeutically with no complications. This case focuses on the typical presentation of appendicitis and RLQ pain in a patient with an atypical anatomical structure. It aims to depict the importance of a widened knowledge of the aberrantly located appendix and how this can impact clinical presentation.

Introduction

Appendicitis is one of the most common causes of abdominal pain in the younger population and accounts for over 40,000 hospital admissions per year across England. Classic symptoms include right iliac fossa (RIF) pain, anorexia, nausea, constipation, and vomiting; however, these classical presentations only occur in 50% of people [ 1 ]. In the presence of an anatomical variant where the appendix is aberrantly located, as in this case study of a subhepatic appendix, the clinical picture can be skewed making the initial diagnosis of appendicitis more complex.

Case presentation

JN is a 24-year-old female who presented to the accident & emergency department (A&E) with a four-hour history of right lower quadrant (RLQ) abdominal pain. The pain originated in the umbilical region, radiating diffusely across the lower abdomen and subsequently localised to the RLQ. The pain was of sudden onset, sharp and colicky with progressing intensity. Over the counter, oral co-codamol 500mg (a combination analgesic of codeine phosphate and acetaminophen) was taken before presenting to A&E, which did not alleviate the pain. The pain was exacerbated by lifting the right leg and relieved by leaning forwards. Severity was rated eight on a scale of one to 10, with one being no pain and 10 being the most pain possible. This episode had not been preceded by previous abdominal pain, and she denied nausea or vomiting. She opened her bowels post-onset of the pain with no changes to the consistency of the stools and absence of blood or mucus. She denied urinary or infective symptoms. Past medical and surgical history was nil of note. Drug history included the oral contraceptive pill with no known drug allergies. There was no relevant family history. The patient did not smoke, reported alcohol consumption occasionally, and denied recreational drug use.

Examination

Under observation, JN was apyrexial with stable vital signs. The abdominal examination revealed a soft abdomen, tenderness on percussion, rebound tenderness in the RIF, and a positive psoas sign. She was not peritonitic and had a negative Rosving's sign and absent hernias.

Investigations

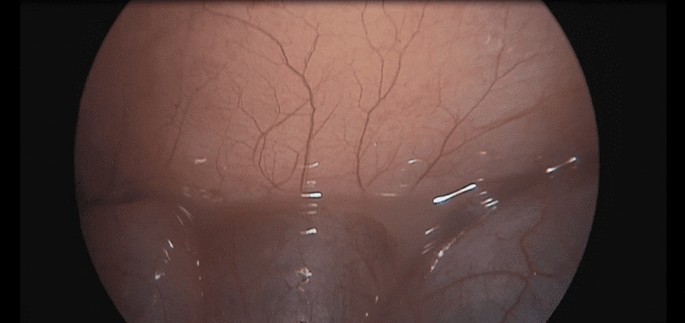

Based on the clinical presentation of JN, the initial impression pointed towards a provisional diagnosis of acute appendicitis, with ovarian cyst as a differential. Subsequent investigations revealed a negative urine dip and negative pregnancy test, which deemed a gynaecological cause unlikely. Blood results were all within normal ranges. Abdominal ultrasonography confirmed a diagnosis of appendicitis by the presence of free fluid within the RIF and within the 6mm appendix which was incompressible. These findings were in keeping with appendicitis. A key point to note is that the location of the appendix was a variant of the anatomical norm. It was visualised at the level of the right liver, indicating a subhepatically located appendix (Figure 1 ). This finding revised the diagnosis to subhepatic appendicitis.

JN was commenced on the following medications whilst in A&E: Electrolyte solution infusion 1000ml IV, Paracetamol 1g oral, Morphine 10mg oral, Metronidazole 500mg IV. Following this, she was transferred to theatres for surgery.

Surgical report

A laparoscopic appendicectomy was performed under general anaesthesia with the following ports: umbilical 12mm, left iliac fossa 5mm, suprapubic 5mm. Reporting on the operation, the small bowel was dilated from the terminal ileum to proximal jejunum. The caecum was lying at the hepatic flexure and resultantly the appendix base was posteroinferior to the inferior border of the liver. This was attributed to a congenital adhesion causing malrotation of the caecal pole. The appendix itself did not appear inflamed or perforated and there was no free pus. Serous fluid was present in the pelvis and right upper quadrant (RUQ). Other than these observations, the sigmoid colon, uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes were normal.

Upon discovering the anatomical variant, the adhesions were divided, caecum returned to the appropriate position in the RIF and appendix mobilised. There was diathermy and division of the appendicular artery. Vicryl endo-loops were applied, the appendix was divided and removed via the umbilical port. Finally, washout to the RIF and pelvis was performed and aspirated.

Following surgery, JN was stable and recovered well with mild bloating and tenderness. The patient was discharged with no prescription medication or follow up required.

It is rare for the caecum and appendix to be located subhepatically since subhepatic appendicitis makes up an annual incidence of 0.09 per 100,000 population [ 2 ]. In this patient, malrotation of the caecal pole resulted in the caecum being located at the hepatic flexure and appendix base posteroinferior to the inferior border of the liver. The cause, in this case, was attributed to congenital adhesions which tend to arise during physiological organogenesis or as a result of an abnormality in the embryonal development of the abdominal cavity [ 3 ].

The most reliable examination findings for acute appendicitis have been noted as tenderness on percussion, guarding, and rebound tenderness at the RIF [ 1 ]. When considering the anatomically higher appendix, it is noteworthy that examination findings are consistent with an appendix lying in the standard RIF location. Similar cases of subhepatic appendicitis accounted by Hafiz et al. (2017) and Ball et al. (2013) both report predominant RUQ pain as opposed to RLQ pain prompting an inaccurate consideration of biliary pathology [ 4 , 5 ]. In the case observed by Hafiz, a positive Murphy’s sign was also elicited despite previous cholecystectomy [ 4 ].

In many circumstances, atypical presentations of appendicitis are investigated using diagnostic laparoscopy. In this case, the initial intention of utilising a therapeutic approach of laparoscopic appendectomy reverted to diagnostic investigation upon discovery of the congenital adhesions and anatomical variation. Thus, laparoscopy proves beneficial for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in the case of anatomical variants.

Conclusions

To conclude, this was a 24-year-old female who presented with RLQ pain and was diagnosed with acute appendicitis. The patient had an appendix located posteroinferior to the inferior border of the liver; laparoscopy revealed congenital adhesions causing malrotation of the caecal pole. Therapeutic laparoscopic appendectomy was performed with no complications. This case raises awareness of a rare case of subhepatic appendicitis where the pain was localised to the RLQ, but the anatomical position of the appendix was in the RUQ. It is important for clinicians to be aware of such anatomical variants and the use of laparoscopic appendectomy as both an exploratory and therapeutic technique.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

Appendicitis

Author: Matthew Fannell MD, John Solms MD, J. Scott Wieters MD, Texas A&M College of Medicine, Baylor Scott & White Hospital

Editor: Eric Blazar, Inspira Vineland Medical Center, Rowan School of Medicine, 2019

Last updated: November, 2019

19 year old male presents with 2 day history of intermittent right lower quadrant abdominal pain. He reports that the pain has progressively worsened and has slowly moved from just below his belly button and it now more intense in the right lower quadrant. Also reports that the pain is made worse by walking and by the car ride to the ED. He complains of one episode of vomiting and intermittent nausea. No other significant medical history. On exam VS are Temp 100.4, HR 95, RR 18, BP 110/73 SpO2 99% on RA. Patient appears uncomfortable and is sitting quietly on the stretcher. Exam is pertinent for tenderness over the right lower quadrant of the abdomen with rebound tenderness. No other abnormal findings on exam.

Upon completion of this module, the student will be able to:

- Identify patients with suspected appendicitis

- Describe the classic history and physical exam findings in appendicitis, as well as atypical presentations

- Discuss the roles of laboratory tests and imaging in the diagnosis of appendicitis

- Describe the management options for appendicitis

Introduction

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common atraumatic surgical emergencies. It can affect patients at any age, however the incidence peaks around the second and third decades of life. Reports of male to female predominance are conflicting, with some sources citing either sex with a slight majority. In pregnancy, appendicitis is the most common non-obstetric surgical emergency. Although the incidence peaks earlier in life, appendicitis can present at any point in life. Thus, the diagnosis should be considered in patients of all ages with atraumatic abdominal pain.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

As with any patient presenting to the ED, the primary survey should precede all other management. A vast majority of patients who ultimately are diagnosed with appendicitis present with stable vital signs and airway, breathing, and circulation intact. However, any compromise in these areas must be addressed first. If necessary, resuscitation should begin with IV fluids to treat hypotension and antipyretics to treat fever. Pain should also be adequately managed

Presentation

The classic presentation of appendicitis occurs as follows:

- Vague epigastric or periumbilical pain.

- Nausea, vomiting and anorexia.

- Abdominal tenderness, migrating and then localizing to the right lower quadrant.

- Leukocytosis

This classic presentation though, is highly variable, especially at the extremes of age and due to the anatomical variation of appendix location. A retrocecal appendicitis may present a variety of ways including low back pain, left sided pain and even right upper quadrant pain.

Right lower quadrant pain and guarding generally have a high sensitivity (81%) for appendicitis, but are poorly specific (53%). Abdominal rigidity is also highly specific (83%) but has a low sensitivity (27%). The classic Psoas, Obturator and Rosving’s signs are all relatively poor predictors of appendicitis. No single exam finding should be used to rule in or rule out the disease.

Atypical presentations can occur in any patient, but more are more likely in extremes of age, and pregnant patients. Children can be more of a diagnostic challenge due to communication barriers and vague symptoms. In children less than four years old perforation rates can be as high as 90%.

Another high-risk population includes elderly patients presenting with subtle signs and significant comorbidities. They too can often present late. Immunosuppressed patients will likely have a decreased inflammatory response and may have more subtle signs, similar to the elderly population.

Maintaining a high level of suspicion for appendicitis is important. However, it is vital to consider a broad differential as well. A genital exam is paramount in both sexes. A testicular exam should be performed in males to evaluate possible torsion or other male GU etiology that would present with RLQ abdominal pain. Females of childbearing age require special attention to rule out gynecologic or obstetric pathology that can be misdiagnosed as appendicitis. These disease etiologies include ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, and tubo-ovarian abscess. The pregnant patient can also have atypical complaints secondary to a gravid uterus.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory Studies

There is no single lab test specific for the diagnosis of appendicitis. Many patients with appendicitis will have leukocytosis, however, 10-20% of patients will have a normal white blood cell count. The converse is also true. Many patients with leukocytosis will not have appendicitis, as many other pathologies cause an elevated WBC. Another inflammatory marker, C-reactive protein, can be used along with the WBC for supporting or ruling out appendicitis CRP alone cannot be used to rule in or rule out the disease1. Both an elevated CRP and WBC have a combined sensitivity of 98%, and if both labs are within normal limits the diagnosis is less likely.

Urine studies should be obtained. They are useful for determining pregnancy, and evaluating for infection and hematuria. Pyuria without bacteria present can be cause by inflamed appendix in close proximity to the ureter or bladder. Hematuria without other findings could suggest a ureteral stone as the cause of pain. Again, UA in isolation cannot rule out appendicitis.

Ultrasound is quickly becoming a more popular diagnostic tool in the Emergency Department. It is the preferred imaging modality in children and pregnant patients with suspected appendicitis due to the absence of radiation. One multicenter cohort study found ultrasound to be 72.5-86% sensitive and 96% specific for appendicitis in children. The diagnostic accuracy is variable depending on the skills of the sonographer and size of the patient. Ultrasound is typically much less sensitive in adults than children. A normal appendix on ultrasound is typically less than 6 mm and compressible. An appendix greater than 6-7 mm in diameter and noncompressible is indicative of appendicitis. Other findings that support the diagnosis are increase wall thickness, fecalith, and increased vascularity. Doppler flow can be used to demonstrate the increased vascularity of an inflamed appendix. An excellent resource for learning this skill is the Ultrasoundpodcast.com. ( http://www.ultrasoundpodcast.com/2011/08/appendix/ )

Computed Tomography

CT is currently the preferred imaging study for evaluating acute appendicitis in adult males and nonpregnant females. CT of the abdomen/pelvis is also more useful for evaluating alternative diagnoses, and diagnosing complications of appendicitis (perforation, abscess, etc.). As with ultrasound, an enlarged appendix over 6-7 mm, increased wall thickness, fecalith, and peri-appendiceal stranding can support the diagnosis. The overall sensitivity for IV contrast enhanced CT ranges from 95-100%, which is considerably better than ultrasound. Similarly, specificity is around 96%. One study showed that non–contrast CT (90 % sensitivity and 86% specificity) was inferior to CT with rectal only administered contrast (93% sensitivity and 95% specificity) and CT with both IV and oral contrast (100 % sensitivity and 89% specificity). However, given the slight increase in morbidity associated with oral and rectal contrast, along with improved resolution of newer CT scanners, most clinicians use IV contrast alone. While IV contrast is recommended for evaluation of suspected appendicitis, non-contrast CT still has excellent sensitivity, ranging from 89.5%-96% depending on the study. The ability to accurately use non-contrast CT studies is helpful in patients with relative contraindications, such as renal insufficiency and contrast allergy. Non-contrast CT scans are also quicker to obtain.

Image 1. CT image of appendicitis demonstrating a dilated appendix with periappendiceal stranding. Original image provided by J. Scott Wieters MD. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Utilizing MRI to diagnose appendicitis is typically reserved for pregnant patients after a non-diagnostic ultrasound. MRI has a similar diagnostic accuracy compared to CT, however emergent MRI often has limited availability, is expensive, and is more time consuming. As with ultrasound, MRI avoids radiation exposure however, the contrast medium used in the study, IV gadolinium, is a potential teratogen. Similar to using IV contrast with CT, IV gadolinium is not traditionally used in patients with renal insufficiency.

How to make the Diagnosis?

As mentioned above most cases of suspected appendicitis require lab test and imaging.

- In adults, complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, CRP, and urinalysis are a good starting point. Urine pregnancy should be obtained for all females of childbearing age.

- If the patient is a male or a nonpregnant female a CT scan would be the imaging modality of choice, preferably with IV contrast.

- If the patient is child, pregnant or you have a high suspicion for gynecologic disease, then ultrasound would be a more appropriate initial imaging modality.

- For low risk pediatric patients with an indeterminate ultrasound observation for serial exams is warranted to avoid radiation and/or contrast. Another reasonable option in a low risk patient would be to have them return to the emergency department in 12 to 24 hours for a repeat examination. This option to return is also applicable to patients with negative CT scans and persistent symptoms.

All patients discharged home after a negative workup should be counseled on very specific return precautions. No diagnostic test is perfect.

Clinical decision tools, such as the Alvarado score can be useful when considering the diagnosis of appendicitis. A calculator for the Alvarado score can be found here. A low score, <1-4, has approximately 96% sensitivity for ruling out appendicitis. In a meta-analysis the Alvarado score was inconsistent in children, tended to over predict appendicitis in women, but was well calibrated in adult males.

Acute appendicitis is traditionally treated surgically. Prompt appendectomy has been the standard treatment for decades. That said, there have been recent studies that call into question the reliance upon surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis given the morbidity associated with open appendectomy. In settings where laparoscopic technology exists, such as the vast majority of the United States, consensus remains that surgical intervention is superior; however, in resource limited settings there are compelling studies that suggest that IV antibiotics, or even in some cases oral antibiotics, can produce sufficient success in treatment to overcome the risk associated with open appendectomy. At this time, studies with greater power are needed for broad application of an antibiotics first approach. RebelEM non-operative treatment of appendicitis. Skeptics Guide to EM non-operative treatment of pediatric appendicitis. Of note, certain complicated cases like perforation with a walled off abscess may require drainage by interventional radiology. Decision making in these scenarios should be discussed with an interdisciplinary team for coordination of care.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed the patient should be made NPO and IV antibiotics should be started in the emergency department. Examples of appropriate antibiotics for uncomplicated appendicitis include ampicillin-sulbactam, or cefoxtin, or a combination of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin.

For complicated appendicitis (perforation, abscess, immunocompromise, etc.) a carbapenem, such as meropenem or imipenem, can be used or an extended spectrum penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor, such as piperacillin/tazobactam.

Do not forget IV fluid resuscitation, pain control and antiemetics. Analgesia with reasonable doses of opioids has not been shown to alter the abdominal exam.

Emergency Department Disposition

- OR for appendectomy

- Interventional Radiology for percutaneous drainage of abscess

- Observation in hospital for serial examinations

- Return in 12-24 hours for a repeat examination

Case Resolution

Patient is treated with IV morphine, ondansetron, and 1 liter Lactated Ringers bolus. Labs demonstrate an elevated WBC to 13.9k. CT of the abdomen/pelvis demonstrates an inflamed appendix with stranding in the right lower quadrant consistent with uncomplicated appendicitis. No evidence of perforation. A single dose of cefoxitin was administered and the on-call surgeon was consulted for surgical removal. Patient had an unremarkable operative course and was discharged home later that evening.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Maintain a broad differential diagnosis

- An afebrile patient with a normal WBC does not rule out appendicitis

- There is no single sign, symptom, or lab that completely rules out appendicitis

- Urinalysis with pyuria or hematuria can be appendicitis due to an inflamed appendix next to the bladder and hematuria may represent nephrolithiasis. .

- The localization of pain can be atypical due to the anatomic position of appendix and referred pain.

- Ultrasound should be used as the first imaging study in children and pregnant females

- Extremes of age have atypical presentations necessitating a high index of suspicion

- In females presenting with RLQ pain and tenderness, make sure gynecologic diseases have been appropriately considered including ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion, or tubo-ovarian abscess.

- Check the testicles! Do not miss torsion.

- Every patient discharged home after a negative workup should receive appropriate return precautions. No test is perfect.

- Please see additional pearls and pitfalls here

- Sengupta A, Bax G, Paterson-Brown S. White cell count and C-reactive protein measurement in patents with possible appendicitis . Ann R Coll Sure Engl. 2009;91(2):113-115.

- Anderson, BA et al. Am J Surg. 2005 Sep;190(3):474-8. A systematic review of whether oral contrast is necessary for the computed tomography diagnosis of appendicitis in adults.

- Cope, Z; Silen, WCope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen (22nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-973045-2. p. 67 – 104.

- Dearing, Daniel & A Recabaren, James & Alexander, Magdi. Can Computed Tomography Scan be Performed Effectively in the Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis without the Added Morbidity of Rectal Contrast?. The American surgeon. 2008. 74. 917-20.

- DeKoning, E. Acute Appendicitis. Chapter 84. In: Tintinalli J, ed. Emergency Medicine Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2011:574-78. Hlibczuk, V et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Jan;55(1):51-59.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.06.509. Diagnostic accuracy of noncontrast computed tomography for appendicitis in adults: a systematic review.

- Humes, D and Simpson, J. Clinical review: Acute appendicitis. BMJ 2006;333;530-534. doi:10.1136/bmj.38940.664363.

- Kharbanda, A and Sawaya, R. Acute Abdominal Pain in Children. Chapter 124. In: Tintinalli J, ed. Emergency Medicine Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2011:839-845.

- Mittal, MK et al. Performance of ultrasound in the diagnosis of appendicitis in children in a multicenter cohort. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Jul;20(7):697-702. doi: 10.1111/acem.12161

- Ohle, R. BMC Medicine. 2011, 9:139 doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-139. The Alvarado score for predicting acute appendicitis: a systematic review

- Salminen, Paulina et al. “Five-Year Follow-up of Antibiotic Therapy for Uncomplicated Acute Appendicitis in the APPAC Randomized Clinical Trial” JAMA vol. 320,12 (2018): 1259-1265.

- Smith, MP et al. Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria right lower quadrant pain–suspected appendicitis. [online publication]. Reston (VA): American College of Radiology (ACR); 2013.

- Talan, David A et al. “Antibiotics-First Versus Surgery for Appendicitis: A US Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Allowing Outpatient Antibiotic Management” Annals of emergency medicine vol. 70,1 (2016): 1-11.e9.

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

68 templates

33 templates

36 templates

34 templates

9 templates

35 templates

Acute Appendicitis Clinical Case

Acute appendicitis clinical case presentation, free google slides theme and powerpoint template.

There’s one part of the body that nobody knows why it’s there: the appendix. This organ is thought to be a remnant of our past, but the truth is that nowadays it doesn’t have any vital function in our organism. And if that wasn’t enough, sometimes it even causes harm! When the appendix becomes irritated and inflamed, it causes acute appendicitis, a severe condition that causes lots of pain to the person and that gets worse quickly. Speak about it, its causes and the treatment with this medical template focused on this condition.

Features of this template

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 30 different slides to impress your audience

- Contains easy-to-edit graphics such as graphs, maps, tables, timelines and mockups

- Includes 500+ icons and Flaticon’s extension for customizing your slides

- Designed to be used in Google Slides and Microsoft PowerPoint

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Includes information about fonts, colors, and credits of the free resources used

How can I use the template?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

CHAPTER 7: ACUTE APPENDICITIS

KATHRYN L. BUTLER

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case scenario, epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation.

- DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- WORKUP AND CHOICE OF IMAGING

- IMAGING FINDINGS

- SPECIAL IMAGING CONSIDERATIONS

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

A 27-year-old woman with no past medical history presents to the emergency room with 24 hours of abdominal pain. The day prior to presentation, she developed diffuse, vague abdominal discomfort. She lost her appetite and went to bed early secondary to malaise. The following morning, the pain worsened in intensity, became sharp, and localized to the right lower quadrant.

The patient is afebrile, with normal vital signs. On examination, she is focally tender to palpation in the right lower quadrant with voluntary guarding. Palpation of the left lower quadrant reproduces pain on the right. Her lab work is unremarkable with the exception of a mild leukocytosis to 13.

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common surgical diagnoses presenting to the emergency room. It occurs most frequently among patients between their teens and thirties, with a slight male predominance (1.4:1) and with the highest proportion of cases affecting patients aged 10 to 19 years. 1 , 2 Prompt recognition is paramount to prevent appendiceal perforation; however, appendicitis in women, children, and the elderly may present with an atypical constellation of signs and symptoms that delays diagnosis.

The appendix is a blind-ending pouch arising from the cecum at the point where the taenia coli converge. A true diverticulum, it contains all layers of the colonic wall. In appendicitis, a fecalith, tumor, or lymphocyte proliferation blocks the lumen, and the appendix distends with mucus. Distension compromises blood supply to the appendiceal wall, and stasis within the appendix allows for bacterial overgrowth. Bacteria then invade the compromised wall of the appendix, producing an inflammatory exudate that irritates the peritoneum. Local ischemia follows initial inflammation and progresses to perforation with the development of contained abscess, phlegmon, or generalized peritonitis.

The hallmark of appendicitis is abdominal pain that starts in the peri-umbilical region and is described as dull or cramping, followed by migration of discomfort to the right lower quadrant with a sharpening in quality. The peri-umbilical pain arises secondary to stimulation of visceral afferent nerve fibers at T8-T10 as intraluminal pressure increases. Pain becomes localized and sharp when inflammation extends to the serosa and irritates the parietal peritoneum. Other associated symptoms are nonspecific and may include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and low-grade fever. Patients may complain of dysuria if the appendiceal tip assumes a pelvic location.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Click here - to use the wp menu builder

- Privacy Policy

- Refund Policy

- Terms Of Service

- Nursing notes PDF

- Nursing Foundations

- Medical Surgical Nursing

- Maternal Nursing

- Pediatric Nursing

- Behavioural sciences

- BSC NURSING

- GNM NURSING

- MSC NURSING

- PC BSC NURSING

- HPSSB AND HPSSC

- Nursing Assignment

A Case Study on Appendicitis: Diagnosis, Management, and Nursing Care

A Case Study on Appendicitis: What is Appendicitis? , Diagnosis, Management, and Nursing Care,

Table of Contents

What is Appendicitis ?

Appendicitis is a common medical emergency that requires prompt diagnosis, management, and nursing care to prevent complications and improve patient outcomes. The purpose of A Case Study on Appendicitis is to discuss the clinical presentation, diagnosis, management, and nursing care of a patient with appendicitis.

A Case Study on Appendicitis

A 35-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a 24-hour history of right lower quadrant abdominal pain, nausea , and vomiting. He reported a loss of appetite and a low-grade fever. The patient denied any recent changes in bowel movements or urinary symptoms. His medical history was unremarkable, and he was not taking any medications. On physical examination, the patient appeared uncomfortable and had a temperature of 100.4°F. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in the right lower quadrant, guarding, and rebound tenderness. Laboratory tests showed an elevated white blood cell count and C-reactive protein level.

Diagnosis of Appendicitis

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation and laboratory findings, the diagnosis of acute appendicitis was suspected. An abdominal ultrasound was ordered, which revealed a dilated and inflamed appendix with a diameter of 1.2 cm. A CT scan was also performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of acute appendicitis and ruled out any complications such as perforation or abscess formation.

Management of Appendicitis

The patient was admitted to the hospital and started on intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover for possible bacterial infections. The patient was taken to the operating room for an emergency laparoscopic appendectomy. During the surgery, the appendix was found to be inflamed and edematous, but no signs of perforation were noted. The surgery was completed without any complications, and the patient was transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit for monitoring. The patient was able to tolerate a regular diet and was discharged home after 2 days of hospitalization with a prescription for oral antibiotics.

Nursing Care of Appendicitis

During the hospital stay, the nursing care of the patient with appendicitis included monitoring vital signs, administering medications, providing pain management, assessing for signs of infection, and promoting ambulation and deep breathing exercises to prevent postoperative complications. The nurse also provided patient education on wound care, signs of infection, and the importance of completing the course of antibiotics. The nurse encouraged the patient to report any adverse reactions to the medication and advised the patient to avoid heavy lifting and strenuous activity for at least 2 weeks after surgery.

Where is pain appendicitis?

The pain from appendicitis usually starts around the belly button and then moves to the lower right side of the abdomen. The pain may be dull and achy at first, but it can become sharp and severe as the condition progresses. The pain may also worsen with movement or coughing. Some people may also experience pain in the back or rectum, especially if the appendix is located in a different position than usual. It is important to seek medical attention if you experience any of these symptoms, as untreated appendicitis can lead to complications.

What food can cause appendicitis?

There is no clear evidence to suggest that any specific food causes appendicitis. Appendicitis is typically caused by a blockage of the appendix, usually from fecal matter, a foreign object, or enlarged lymphoid tissue. Bacteria can then infect the blocked appendix, causing inflammation and the symptoms of appendicitis.

While there is no food that is known to cause appendicitis, there are some dietary habits that may increase your risk of developing the condition. For example, a diet high in processed foods and low in fiber can lead to constipation, which in turn can increase the risk of a blockage in the appendix. Additionally, a diet high in red meat and low in vegetables has been associated with an increased risk of appendicitis.

It is important to maintain a balanced and healthy diet to reduce the risk of developing appendicitis and other gastrointestinal conditions. This includes consuming plenty of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins. Drinking plenty of water and staying hydrated is also important for maintaining a healthy digestive system.

Conclusion:A Case Study on Appendicitis

Appendicitis is a common medical emergency that requires prompt diagnosis, management, and nursing care to prevent complications and improve patient outcomes. Early recognition of the signs and symptoms of appendicitis and prompt referral to a healthcare provider is crucial in the timely diagnosis and management of the condition. The nurse plays a critical role in the assessment, management, and education of the patient with appendicitis to ensure optimal outcomes.

Please note that this article is for informational purposes only and should not substitute professional medical advice.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent articles, the advantages of electronic health records, nursing assessment: the first step in the nursing process, mental health nurse role and responsibilities, nursing diagnosis for wound infection, the effects of gravity on the human body, exploring the levels of communication, download nursing notes pdf, study material nurse recruitment exam solved paper pdf – i, sensory system and sense organs pdf, psychology note nursing pdf, study material nurse recruitment exam solved paper pdf – ii, anatomy and physiology the cardiovascular system nursing notes, male and female reproductive system pdf, human nervous system nursing pdf, case study on appendicitis nursing assignment, more like this, what is a nursing diagnosis, the role and qualities of mental health and psychiatric nurses, practical nursing: a career in caring, 4 core principles of nursing ethics, mental health nursing diagnosis care plan pdf, child pediatric health nursing notes -bsc nursing, mid-wifery pdf notes for nursing students, national health programmes in india pdf, reproductive system nursing notes pdf, primary health care nursing notes pdf, nursingenotes.com.

- STUDY NOTES

- SUBJECT NOTES

A Digital Platform For Nursing Study Materials

Latest Articles

The role of comprehensive assessment nursing, types of nurses and their salaries, exploring 5 definitions and models of health, most popular.

© Nursingenotes.com | All rights reserved |

Case report

- Open access

- Published: 18 January 2024

Left-sided appendicitis managed laparoscopically: a case report

- Tamara B. AlKeileh 1 ,

- Sali Elsayed 1 ,

- Raheemah Mahomed Adam 1 ,

- Mozamil Nour 2 &

- Tarun Bhagchandi 3

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 18 , Article number: 21 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

8735 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Appendicitis is one of the most common causes of acute abdominal pain and remains the most common abdominal-related emergency seen in emergency room that needs urgent surgery (Yang et al . in J Emerg Med 43:980–2, 2012. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.056, Wickramasinghe et al . in World J Surg 45:1999–2008, 2021. 10.1007/s00268-021-06077-5). The characteristic presentation is a vague epigastric or periumbilical discomfort or pain that migrates to the lower right quadrant in 50% of cases. Other related symptoms, such as nausea, anorexia, vomiting, and change in bowel habits, occur in varying percentages. The diagnosis is usually reached through comprehensive history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiological investigations as needed. Nowadays, computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis is considered the modality of choice for definitive assessment of patients being evaluated for possible appendicitis. Anatomical variations or an ectopic appendix are rarely reported or highlighted in literature.

Case presentation

Left-sided appendicitis is a rare (Hu et al . in Front Surg 2022. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.896116) and atypical presentation and has rarely been reported. The majority of these cases are associated with congenital midgut malrotation, situs inversus, or an extremely long appendix (Akbulut et al . in World J Gastroenterol 16:5598-5602, 2010. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i44.5598). This case is of significance to raise awareness regarding an anatomical variation of the appendix that might delay or mislead diagnosis of appendicitis and to confirm safety of a laparoscopic approach in dealing with a left-sided appendicitis case (Yang et al . in J Emerg Med 43:980–2, 2012. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.056). We report a case of left-sided appendicitis in a 12-year-old child managed successfully via a laparoscopic approach.

Appendicitis remains the most common abdominal-related emergency that needs urgent surgery (Akbulut et al . in World J Gastroenterol 16:5598–5602, 2010. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i44.5598). Left-sided appendicitis is a rare (Hu et al . in Front Surg 2022. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.896116, Hu et al. in Front Surg 9:896116, 2022. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.896116) and atypical presentation and has rarely been reported. Awareness regarding an anatomical variation of the appendix and diagnostic modalities on a computed tomography scan help avoid delay in diagnosis and management of such a rare entity (Vieira et al . in J Coloproctol 39(03):279–287, 2019. 10.1016/j.jcol.2019.04.003). A laparoscopic approach is a safe approach for management of left-sided appendicitis (Yang et al . in J Emerg Med 43:980–2, 2012. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.056, Hu et al . in Front Surg 9:896116, 2022. 10.3389/fsurg.2022.896116).

Peer Review reports

A 12-year-old boy of Arabic ethnicity, with good school performance, previously medically free and not on any medical treatment, and belonging to a middle class family with no known medical or inherited diseases in his family history, presented to our emergency room accompanied by his parents with typical acute appendicitis symptoms, yet was found on investigation to have an ectopic appendix on the left side of the abdomen.

Familiarity with the anatomy and anatomical variants of the appendix and colon is essential to make the correct diagnosis and choose the appropriate treatment modality without any delay. A majority of cases of patients with left-sided appendicitis have an associated midgut malrotation, situs inversus totalis, or a very long appendix. A computed tomography (CT) scan modality can help in an accurate diagnosis of these cases with anatomical variations and in preoperative planning of surgical approach.

Introduction

In an acute setting, early diagnosis of acute appendicitis is imperative to prevent further complications [ 1 ]. This can be made more difficult with atypical presentations or unusual anatomy of appendix, such as a left-sided appendix. From the surgical approach, laparoscopic intervention is advantageous, as it is minimally invasive with fewer complications; however, the operative technique and duration can be influenced by cases with atypical anatomical variants.

Reviewing medical literature, we only found a few cases that presented left-sided appendicitis or anatomic anomalies of the appendix. Most cases presented were linked to situs inversus. In our abstract, we present a unique case of left-sided appendicitis in a 12-year-old child who was found to have an arrested intestinal rotation that led to the abnormal position of his appendix.

The importance of reporting such cases is to highlight and bring the attention of surgeons to the likelihood of anomalic variations of the appendix, which can lead to a raised level of suspicion and early detection of appendicitis without any delay or complications due to delay.

A 12-year-old boy of Arabic ethnicity, with good school performance, previously medically free and not on any medical treatment, and belonging to a middle class family with no known medical or inherited diseases in family history, presented to our emergency room accompanied by his parents complaining of moderate-to-severe abdominal pain in the epigastric region of the abdomen for 1 day prior to presentation to the emergency room.

According to the patient and his mother, on the morning of presentation to our emergency room, the pain migrated and became more prominent in the lower right abdomen. He also developed recurrent vomiting and diarrhea episodes from the start of his illness episode, 1 day prior to his presentation to our emergency room, along with anorexia and feeling of fatigue; no fever was documented, but he had episodes of chills. On inquiring from mother, the patient had no recent history of upper respiratory tract infection and had no previous medical conditions or surgical interventions.

On physical examination, the patient was conscious, alert, and oriented, with no neurological deficit; he seemed ill and slightly dehydrated (with dry eyes and skin), and he was in pain. His vital signs showed a low-grade fever of 37.2 °C, pulse rate of 95 beats per minute, and blood pressure of 100/70 mmHg. His weight was 43 kg, and height was 152 cm.

On throat examination, he had no throat congestion nor enlarged tonsils. On chest examination, he had resonant chest, equal air entry at both lungs, and no wheezes or crackles. On abdominal physical examination, he was found to have generalized abdominal guarding and lower abdominal tenderness, with the most prominent tenderness in the lower right abdomen, and positive rebound tenderness in right iliac fossa. Other signs of appendicitis, such as Rovsing’s, psoas, and obturator signs, were not elicited, as the patient was in severe pain and withdrawing from any physical examination. A digital rectal examination was not performed, as the patient did not have constipation or blood in his stool, hence, in view of the clinical scenario, a digital rectal examination was thought to not add additional value in diagnosis.

Keeping in mind possible differential diagnosis of patient presentation in this case, gastroenteritis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, Meckel’s diverticulum, pyelonephritis or nephrolithiasis, typhilitis, testicular torsion, and acute appendicitis remain on the top of the list to prove or rule out, hence, further investigations were done accordingly [ 2 ].

The laboratory results were significant for leukocytosis (12.14 × 10 9 cells/L) with neutrophilia (80.4%). His hemoglobin was 12.4 g/dL, and CRP was only 3.0 mg/dL; his blood urea nitrogen/creatinine and electrolytes were normal.

An abdominal ultrasound revealed enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, but the appendix could not be visualized due to bowel gases.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, which showed an inflamed and thickened appendix measuring 1.1 cm in diameter, with mild free fluid in the pouch of Douglas. The findings were suggestive of acute appendicitis changes. The appendix was localized retrocecal, but the cecum was at the midline, and the tip of the appendix was seen at the left side of the urinary bladder.

Enlarged reactive mesenteric lymph nodes (Figs. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ).

CT of the abdomen showing enlarged appendix (10.50 mm) located to the left of the urinary bladder

CT of the abdomen (coronal view) showing the appendix (yellow) between the cecum (red) and rectum (green)

CT of the abdomen (axial cut) showing location of appendix toward the left side of the abdomen

CT of the abdomen (axial cut) illustrating the appendix (arrow) located laterally to the left of the urinary bladder

The patient was admitted to the hospital and was started on intravenous (IV) fluids and intravenous antibiotics; he received ceftriaxone 1 g IV every 12 h, metronidazole 500 mg IV every 8 h, and was prepared for surgery.

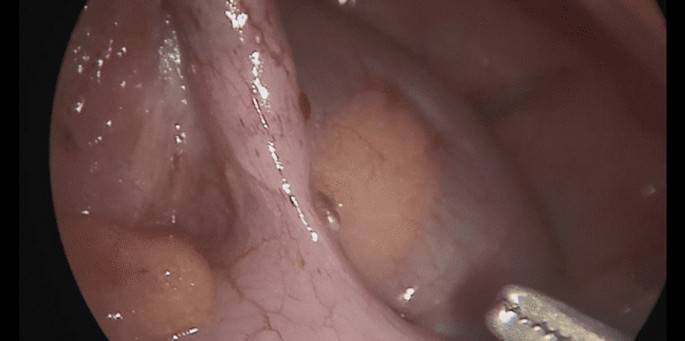

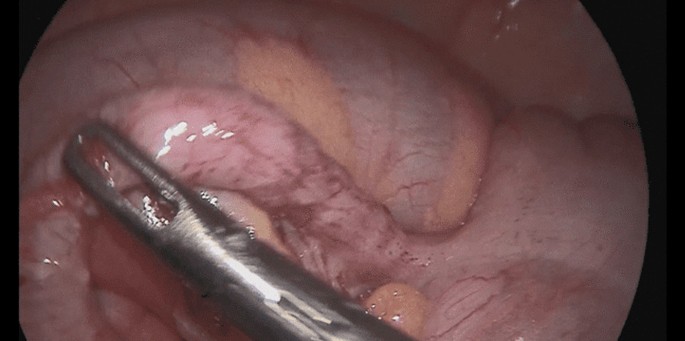

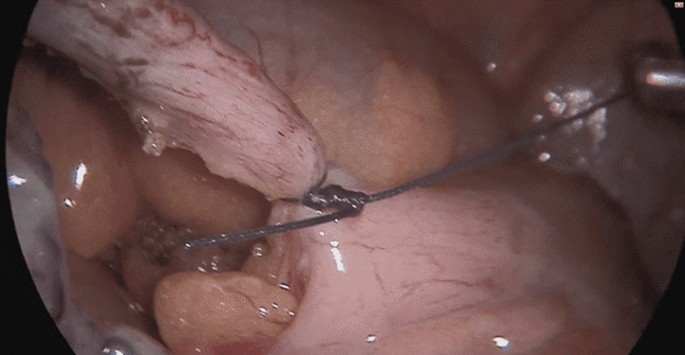

The patient underwent a laparoscopic exploration, and the surgical findings showed free pus collections at the pelvis, the right paracolic gutter, around the liver, and in between bowel loops/generalized peritonitis. The cecum and ascending colon were found to be pushed to left abdomen, adjacent to the descending and sigmoid colon, and the appendix tip was found to be in the left side of the pelvis to the left of the bladder and was inflamed, especially distally at the tip, measuring up to 1.2 cm in diameter, approximately, with a healthy-looking base arising from the cecum. (Figs. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ).

Laparoscopic view showing free pus in the lower left abdomen at the site of the inflamed appendix

Laparoscopic view showing free pus between the small bowel loops on the right of the abdomen

Laparoscopic view showing the appendix tip can be seen at the left iliac fossa between the cecum and sigmoid

Laparoscopic view showing the appendix base arising from the cecum seen at the left iliac fossa with the sigmoid colon behind

Laparoscopic view showing the left-sided appendix with the cecum and sigmoid seen in the lower left abdomen

Laparoscopic view showing the left appendix ligation of base

The trocars were placed as follows: a infraumbilical 10 mm trocar for camera port and a 5 mm trocar inserted through the incision at suprapubic area and another 10 mm trocar inserted through the incision at the right iliac fossa (in a regular right-sided appendix, this port is usually placed at the left iliac fossa); the monitor was placed on the left side of the patient and the surgeon and assistant on the right side.

The appendix was dissected and ligated at the base using an endoloop and then removed in an endobag. A pus swab culture was taken, and suctioning of the pus and abdominal lavage was performed, leaving a drain at the pelvis and another drain at the subhepatic and right paracolic area, where pus collections were found.

Postsurgery, the patient recovered well; he passed flatus on the second postoperative day and tolerated an oral soft diet. The drains were removed on the third postoperative day, and the patient was discharged home in good condition on the fourth postoperative day.

The histopathological result of the removed appendix revealed acute suppurative appendicitis and periappendicitis, which was negative for malignancy, and the pus culture had no growth.

Postdischarge from the hospital, the patient returned to the clinic accompanied by his parents after 1 week and was doing well clinically with no complaint. No wound infection developed. No further visits to the hospital or clinic related to his surgical condition were required since that date.

In summary, the case we presented is a case of 12-year-old, previously healthy, boy not known to have any medical illnesses who presented with symptoms of abdominal pain, recurrent vomiting, episodes of diarrhea, fatigue, anorexia, and chills. The boy looked ill and had lower abdominal tenderness with positive rebound tenderness on the lower right quadrant, yet investigations showed that he had an ectopic inflamed appendix on the left side, evident on an abdominal CT scan, which helped the surgical teams to plan his surgery accordingly. He underwent a successful laparoscopic appendectomy, and intraoperative findings showed that all the large bowel was on the left side of the abdomen, while the small bowel was on the right side of abdomen. In addition to the severely inflamed left-sided appendix, he was also found to have generalized peritonitis with multiple free pus collections all over the abdomen. He recovered well postoperatively and was discharged in good condition on the fourth day, and he was doing very well in his follow-up at the clinic.

The unique aspect of this case was the absence of situs inversus, and that the preoperative diagnosis led the surgical planning to successfully help and safely manage this case laparoscopically.

Left-sided appendicitis is a rare condition and, therefore, easy to misdiagnose, which could be challenging for surgeons to handle. A delay in diagnosis can lead to serious complications, such as a periappendiceal abscess, perforation, or gangrene [ 1 , 2 , 3 ].

Familiarity with the anatomy and anatomical variants of the appendix and colon is essential to make the correct diagnosis and choose the appropriate treatment modality without any delay [ 3 ]. Hence, a discussion on the anatomical variations and congenital abnormalities of these structures is encouraged to help in keeping medical and surgical teams alert to different possibilities and to avoid missing a patient’s condition.

A majority of cases of patients with left-sided appendicitis have associated midgut malrotation, situs inversus totalis, or a very long appendix [ 4 ]. Intestinal malrotation is a congenital rotational anomaly that occurs as a result of an arrest of normal rotation of the embryonic gut, and is said to occur in 1 in 6000 live births [ 5 ].

In our patient’s case, there was no situs inversus, despite the cecum and ascending colon being on the left side of the abdominal cavity, as well as the descending colon and sigmoid. The small intestine bowel loops were located on the right side of the abdomen, and the appendix was lying down in the pelvis to the left side of the bladder, far away from the lower right quadrant, which represents a sort of intestinal malrotation or arrested rotation.

Additionally, what is interesting in this case is the presence of typical appendicitis signs and symptoms in terms of pain migration, from the epigastric region to the lower right abdomen, and the most prominent tenderness being at the right iliac fossa, despite the later-identified location of the appendix on left side. This symptom also appears in about 18–34% of patients with situs inverses and midgut malrotation [ 4 ]

Keeping in mind possible differential diagnosis of patient presentation in this case, as gastroenteritis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, Meckel’s diverticulum, pyelonephritis or nephrolithiasis, typhilitis, and acute appendicitis remained on the top of the list of our differential diagnosis to prove or rule out, further investigations were done accordingly and proved the diagnosis of acute appendicitis with an ectopic appendix on the left.

In our patient’s case, the findings of right iliac fossa tenderness and rebound tenderness could additionally be attributed to the presence of free fluid collection in the right paracolic gutter, found intraoperatively as part of generalized peritonitis associated with the inflammation of his appendix. Another hypothesis is that it is assumed that, even though the viscera are transposed, the nervous system may not show the corresponding transposition, which may result in confusing signs and symptoms. In about 18.4–31% of patients with situs inversus totalis (SIT) and midgut malrotation (MM), the pain caused by left-sided appendicitis was reported in the lower right quadrant [ 4 ].

Of course, another interesting aspect of this case is the overwhelming inflammatory response to appendicitis despite the short clinical history the patient presented with.

Whether this can be attributed to an under developed omentum, which usually is the case in younger children, or to delay of presentation, the abnormal anatomy of the bowel and ectopic appendix, which led to progression of disease without obvious symptoms until the patient developed severe abdominal pain and presented to the emergency room, could not be determined.

Here, we can appreciate the benefit of an abdominal CT scan in such controversial cases where clinical signs and symptoms, as well as laboratory tests showing the presence of mild leukocytosis and neutrophilia, are correlated with the diagnosis of appendicitis, but the ultrasound scan failed to detect the appendix. It is known that ultrasound is the preferred initial examination in pediatric cases [ 6 ], because it is nearly as accurate as CT scans for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in this population without the use of ionizing radiation [ 7 ].

However, in this case, the ultrasound modality missed the findings, and the CT scan proved the high clinical suspicion of acute appendicitis and added the detection of an ectopic appendix. This was necessary in aiding preoperative planning, reducing operative time and complications, and guiding the surgeon to the exact location of the inflamed appendix.

Contrast-enhanced, thin-section (0.5 mm) CT scanning has become the preferred imaging technique in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis and its complications, with a high diagnostic accuracy of 95–98% [ 6 , 8 , 9 ].

In case abdominal CT is not available or could not be done in such a case scenario, then laparoscopic exploration is advised to avoid missing or delaying the diagnosis, which might end up causing serious harm to the patient’s health. Having a more refined understanding of the patients’ anatomy preoperatively is a necessary factor in deciding equipment needed, placing the port, and avoiding accidental injury during exploration, especially in rare anatomical cases. Once ectopic appendicitis is diagnosed, surgical treatment can be done laparoscopically with a high degree of safety [ 1 , 5 ].

Laparoscopic appendectomy is a safe and effective method for the treatment of ectopic appendicitis [ 1 , 5 , 10 ]. Laparoscopically, the abdominal and pelvic cavity can be explored to determine the diagnosis of ectopic appendicitis and exclude acute abdomen caused by other diseases. The laparoscopic approach is minimally invasive and reduces the incidence of wound infection and hernia, and it offers faster postoperative recovery and fewer complications [ 11 ].

Therefore, it is a safe and effective method for the treatment of ectopic appendicitis and the preferred modality of choice, provided the surgeon has good laparoscopic experience.

The question that arises in this case, and other cases with malrotation, for further discussion is if there is any need for further intervention for the malrotation in absence of any significant symptoms or complications related to it.

Left-sided appendicitis is a rare and atypical presentation and has been rarely reported. The majority of these cases are associated with congenital midgut malrotation, situs inversus, or an extremely long appendix [ 4 ].

Familiarity with the anatomy and anatomical variants of the appendix and colon is essential to make the right diagnosis and choose the right treatment modality with no delay.

Diagnosis is usually reached through a comprehensive history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiological investigations as needed.

Nowadays, CT of the abdomen and pelvis is considered the modality of choice for a definitive assessment of patients being evaluated for possible appendicitis [ 8 ].

Once ectopic appendicitis is diagnosed, a laparoscopic appendectomy can be done safely.

The laparoscopic approach reduces the incidence of wound infection and hernia and offers faster postoperative recovery and fewer complications [ 1 , 5 , 11 ].

Availability of data and materials

All documents related to this case are available on request.

Hu Q, Shi J, Sun Y. Left-sided appendicitis due to anatomical variation: a case report. Front Surg. 2022;9: 896116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.896116 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gadiparthi R, Waseem M. Pediatric appendicitis. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Google Scholar

Welte FJ, Grosso M. Left-sided appendicitis in a patient with congenital gastrointestinal malrotation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-1-92 .

Akbulut S, Ulku A, Senol A, Tas M, Yagmur Y. Left-sided appendicitis: review of 95 published cases and a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(44):5598–602. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i44.5598 .

Yang C-Y, Liu H-Y, Lin H-L, Lin J-N. Left-sided acute appendicitis: a pitfall in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(6):980–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.056 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Deshmukh S, Verde F, Johnson PT, Fishman EK, Macura KJ. Anatomical variants and pathologies of the vermix. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21(5):543–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-014-1206-4 .

de Vieira E, Bonato LM, Silva GG, Gurgel JL. Congenital abnormalities and anatomical variations of the vermiform appendix and mesoappendix. J Coloproctol. 2019;39(03):279–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcol.2019.04.003 .

Article Google Scholar

Lutfi Incesu M. Appendicitis imaging. Medscape; 2022. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/363818-overview . Accessed 15 Jun 2023.

Hu Q, Shi J, Sun Y. Left-sided appendicitis due to anatomical variation: a case report. Front Surg. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.896116 .

Wickramasinghe DP, Xavier C, Samarasekera DN. The worldwide epidemiology of acute appendicitis: an analysis of the global health data exchange dataset. World J Surg. 2021;45(7):1999–2008. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-06077-5 .

Krzyzak M, Mulrooney SM. Acute appendicitis review: background, epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. 2020;12(6): e8562. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8562 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement goes to Dr. Fadel Shabeeb, MD, FACS, FASCRS for raising additional questions for discussion that added value to the abstract.

No funding received for the preparation or publication of the case report.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of General Surgery, Mediclinic Al Noor Hospital, PO BOX 46713, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Tamara B. AlKeileh, Sali Elsayed & Raheemah Mahomed Adam

Department of Radiology, Mediclinic Al Noor Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Mozamil Nour

Department of General Anesthesiology, Mediclinic Al Noor Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Tarun Bhagchandi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

TA wrote the manuscript explaining the details of case and operation and performed literature review. SE reviewed and edited the manuscript. RA arranged the template of the case report and added further literature references. MN added the figures and captions of radiology. TB assisted in discussion of the case and choosing operative images.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tamara B. AlKeileh .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

AlKeileh, T.B., Elsayed, S., Adam, R.M. et al. Left-sided appendicitis managed laparoscopically: a case report. J Med Case Reports 18 , 21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04301-5

Download citation

Received : 01 October 2023

Accepted : 04 December 2023

Published : 18 January 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04301-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Left-sided appendicitis

- Laparoscopic surgery

- Gut malrotation

- Pediatric appendicitis

- Abdominal pain

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- ACS Foundation

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- ACS Archives

- Careers at ACS

- Federal Legislation

- State Legislation

- Regulatory Issues

- Get Involved

- SurgeonsPAC

- About ACS Quality Programs

- Accreditation & Verification Programs

- Data & Registries

- Standards & Staging

- Membership & Community

- Practice Management

- Professional Growth

- News & Publications

- Information for Patients and Family

- Preparing for Your Surgery

- Recovering from Your Surgery

- Jobs for Surgeons

- Become a Member

- Media Center

Our top priority is providing value to members. Your Member Services team is here to ensure you maximize your ACS member benefits, participate in College activities, and engage with your ACS colleagues. It's all here.

- Membership Benefits

- Find a Surgeon

- Find a Hospital or Facility

- Quality Programs

- Education Programs

- Member Benefits

- April 2024 | Volume 109, I...

- Are Antibiotics the Answer...

Are Antibiotics the Answer to Treating Appendicitis?

Tony Peregrin

April 10, 2024

Managing uncomplicated acute appendicitis can involve two treatment pathways—surgery or antibiotics—and is a clinical decision that has been rigorously debated in recent years, driven by data from several prominent clinical trials.

Surgical appendectomy has been the first-line option for treating uncomplicated appendicitis for more than 120 years, 1 although nonoperative management may be a safe alternative for a select patient population. Notably, in the US, only 6% of patients are treated with antibiotics for uncomplicated appendicitis, while the vast majority of patients are managed by laparoscopic appendectomy. 2

However, for some patients, particularly those who are not in a physical state that is conducive for surgery or are located in settings where resources are limited, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, nonoperative management for uncomplicated appendicitis is a viable alternative. 3

Before engaging in any patient-centered decision-making regarding treatment options, it is important to identify if the appendicitis is uncomplicated or complicated, as each disease presents varying degrees of severity. 2 Radiologic assessments, primarily a computed tomography (CT) scan, can quite reliably rule out complicated acute appendicitis and confirm that the patient’s appendix doesn’t have an appendicolith, abscess, or perforation and is, therefore, most likely the uncomplicated form of the disease.

“I was taught to operate on every single patient who was suspected of having acute appendicitis. At that time, we did not use imaging,” said Paulina Salminen, MD, PhD, FACS(Hon), professor of surgery at the University of Turku and Turku University Hospital in Finland. “So, we ended up having 30% to 40% negative appendectomies, especially in young female patients.”

While the APPAC and CODA trials demonstrated that it is likely safe to treat the first episode of uncomplicated appendicitis with antibiotics, clinicians are advised to have honest and straightforward conversations with patients about potential recurrence rates.

Dr. Salminen also is the lead investigator of the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) randomized trials, which focus on the treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

“The main point I want everybody to internalize is the fact that we are talking about two very different diseases,” explained Dr. Salminen. “After you decide that the patient has acute appendicitis, you have to figure out whether it’s the milder form, which is approximately 60% to 70% of cases, or if it is the more difficult form.” She said a primary goal of the inclusion criteria for the APPAC trials (and also clinically) was to rule out patients with complicated acute appendicitis.

Evidence for Antibiotics

The three APPAC trials function as a continuation of research stemming from the initial trial that compared nonoperative management with appendectomy in adults with CT-verified uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

The 5-year follow-up of the first trial (November 2009 to June 2012 in Finland) was completed in September 2017. Among the 530 patients who were selected for the randomized clinical trial, 257 individuals were in the antibiotics group. At the 1-year mark, 70 patients in the group received an appendectomy, with 30 additional patients requiring the procedure between 1 and 5 years. 4 The cumulative recurrence rate evaluated by appendectomy mandated by the study protocol for suspected recurrence was 34% at 2 years, 35.2% at 3 years, 37.1% at 4 years, and 39.1% at 5 years. 2

“Surgery is always a big deal, and everything we do carries risk,” said Drew Gunnells Jr., MD, FACS, assistant professor in the Division of Gastrointestinal Surgery at The University of Alabama at Birmingham. “Although an appendectomy is one of the more straightforward procedures we do, there's still risk associated with it. And, so, can we avoid surgical intervention for a disease that for a long time has been treated with surgery?”

According to Dr. Gunnells, as long as the chance for the patient with uncomplicated appendicitis requiring an operation in the future is minimal, treatment with antibiotics may be a safe option. “I think, based on the Comparison of Outcomes of Antibiotic Drugs and Appendectomy (CODA) trials and the APPAC trials, you’re not putting the patients at risk of undue harm by treating them with antibiotics. The question in my mind is: What's the recurrence rate of appendicitis, and are those patients going to need surgery in the future?”

CODA, a large, randomized clinical trial of antibiotics for appendicitis, was conducted at 25 US medical centers. From May 2016 to February 2020, 1,552 adults with appendicitis were randomly assigned to receive either antibiotics or appendectomies. According to findings presented at ACS Clinical Congress 2020 and published simultaneously in The New England Journal of Medicine , approximately half of the patients in the trial did not require an appendectomy up to 4 years after receiving antibiotics. 5

Despite these findings, clinicians are encouraged to review the data with a critical eye. “We need to have an evidence-based approach to treating uncomplicated appendicitis and not an eminence-based approach,” suggested Dr. Salminen, underscoring the importance of carefully assessing new and existing research in this area.

Dr. Paulina Salminen performs a laparoscopic appendectomy.

Risk of Recurrence

Benjamin H. Stone, MD, MBA, FACS, a general surgeon at The University of Kansas in Kansas City, also suggested focusing on the success and failure rates for both treatment options.

“We’ve had 100+ years of operative therapy for acute appendicitis—so we have a good track record to benchmark other management modalities,” Dr. Stone said. “Surgical therapy is at least 96% effective for this disease. We need to be candid and open about the fact that these results are not the same for nonoperative management. Most of the best studies, when we look at long-term data, have about a 25% failure rate compared to maybe a 1% to 4% failure rate for operative therapy.”

For example, the long-term data for the CODA trial revealed that 40% of patients who were prescribed antibiotics underwent subsequent appendectomy at 1 year and 46% received the procedure at 2 years, rising to 49% at 3 and 4 years. 5

“If you look at the patients with an appendicolith on their initial presentation in the CODA trial who ended up getting an appendectomy, it was about 50% in 2 years,” added Dr. Gunnells. “That number is fairly high in my mind, and those patients probably just need to have their appendices out to decrease their risk of recurrence in the future.”

“The more data we accrue long-term, we find that the recurrence rates continue to go up,” added Dr. Stone. “Those early benchmarks for near equivalence or non inferiority don't seem to hold up over time. I also think it’s important to keep in mind that patients don’t read these studies in depth, if at all, and there are exclusion criteria that need to be considered.”

Exclusion criteria for nonoperative management could include comorbid conditions and other concomitant acute presentations, chronic conditions such as Crohn’s disease, patients taking immunosuppressants or undergoing chemotherapy, as well as patients who are pregnant.

“We’re not trying to omit appendectomy,” explained Dr. Salminen. “We’re just trying to select the patients who would be best off with surgery and others who actually could do without surgery. The majority of recurrences happened during the first year and a half—and that’s quick. If you want to do nonoperative treatment with antibiotics, you need to inform the patients that if they have a recurrence or experience similar symptoms, they need to inform their next surgeon that they’ve already had one round of antibiotics to successfully treat the disease.”

Nonoperative management of uncomplicated acute appendicitis typically begins with intravenous antibiotics.

Paradigm Shifts: Past and Future

Over the last century, a couple of key paradigm shifts regarding the management of appendicitis have happened. After Reginald Herber Fitz published a study on appendicitis in 1886, where he officially named the procedure, Charles McBurney proposed an innovative muscle-splitting operation in 1893. 6

At that time, it was thought that all patients with appendicitis required an appendectomy. “We know that is not true. That realization was the first paradigm shift,” Dr. Salminen said, referring to nonoperative treatment. The second major paradigm that could occur in the future—exploring whether antibiotics can be omitted for uncomplicated acute appendicitis—would result from the findings of the APPAC IV trial, which is currently underway.

“What we’re trying to prove now with APPAC IV is whether or not we even need antibiotics,” said Dr. Salminen, noting that an optimized nonoperative treatment does not currently exist. Typically, nonoperative management begins with intravenous antibiotics followed by as many as 7 days or more of oral antibiotics. 7

“If symptomatic treatment is sufficient with results similar to antibiotics—this really will change the field because then we have a disease that for some patients actually resolves by itself without any specific treatment. So, if you don’t even need antibiotics, you really cannot justify operating on all the patients. That’s not good, evidenced-based medicine,” she said.

Another key component of the APPAC IV trial that could drive a major paradigm shift is the fact that researchers, led by Dr. Salminen, are conducting intravenous antibiotic therapy in the outpatient setting. The majority of patients in the trial will be discharged directly from the ER, which will help determine whether hospitalization can be avoided, saving resources and cutting costs.

“Something that is not always discussed when we’re comparing these studies are the resources that are required as far as money, personnel, and time, especially considering all the follow-up that is required for nonoperative management. Not everyone practices under those circumstances.” Dr. Benjamin Stone

Comparing Costs

Studies comparing the costs associated with nonoperative versus operative treatment are somewhat limited at this point. However, one study demonstrated higher medical costs for surgical treatment of uncomplicated appendicitis with a difference of $1,067 per patient. 2,8

Costs also were discovered to be higher for patients treated operatively in the APPAC trial, at both the 1- and 5-year follow-ups, where the costs were reportedly 1.6 and 1.4 times higher, respectively. 2 These costs included factors related to hospital length of stay and sick time as it correlated to productivity loss.

“This difference in costs to both the service providers and society overall strongly encourages further evaluation of antibiotic therapy as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated acute appendicitis,” noted Dr. Salminen and coauthors in a 2017 article published in the British Journal of Surgery that provided an economic evaluation of both treatment modalities in the APPAC trial. 9

Other clinicians assert that the appendectomy, considered the gold standard treatment, is the least expensive option because of its success rate.

“The reason that it’s the cheapest is because often it’s very effective,” said Dr. Stone. “I think it's the single most effective way of dealing with acute appendicitis as the lowest failure rate. We don't yet have the long-term follow-up that we need with nonoperative therapy to make certain these people aren't recurring, and we know they are, with up to 30% and 40% relapse rates.”

Dr. Stone, who currently practices in a community hospital setting, also highlighted the relevance of some other cost factors that are not routinely discussed in these economic evaluations.