Essay on Discrimination Of Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

Students are often asked to write an essay on Discrimination Of Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Discrimination Of Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

Introduction to indigenous peoples in the philippines.

The Philippines is home to many groups of indigenous peoples, each with their own culture and history. They live in various parts of the country, often in mountains and forests. Sadly, they face discrimination, which means they are treated unfairly because they are different.

Land Issues

One big problem is land. Many indigenous peoples have lost their land to businesses and even the government. This is bad because their land is very important to their way of life and beliefs.

Lack of Rights

Even though there are laws to protect them, these laws are not always followed. This means that indigenous peoples don’t always get the same chances in life, like going to good schools or getting good jobs.

Cultural Misunderstandings

Some people do not understand the cultures of indigenous peoples. They might think their traditions are strange or not important. This can lead to indigenous peoples feeling left out and not respected.

It is important to treat everyone fairly, including indigenous peoples. Everyone should learn about and respect their cultures and rights. This will help stop discrimination and make the Philippines a better place for all.

250 Words Essay on Discrimination Of Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

What is discrimination.

Discrimination means treating someone unfairly because they are different. In the Philippines, indigenous peoples often face this problem. Indigenous peoples are the first people who lived in a place. In the Philippines, they have their own cultures, languages, and ways of life.

One big issue for indigenous peoples is land. Their land is special because it’s where they live, get food, and practice their traditions. But sometimes, other people take this land for business or to use the resources. This leaves indigenous groups with less space and harms their way of life.

Lack of Education and Health

Many indigenous children do not go to school because there are no schools near them or they can’t afford it. Without education, it’s hard for them to find good jobs later. They also have trouble getting medical help when they are sick, which can make them feel forgotten.

Cultural Misunderstanding

Sometimes, people don’t understand the traditions and beliefs of indigenous peoples. This can lead to disrespect and making fun of them. It’s important to respect all cultures and learn about them.

What Can Be Done?

Everyone should be treated equally. The government and all people in the Philippines can help by making sure indigenous peoples have rights to their land, access to schools and hospitals, and respect for their culture. When we all work together, we can stop discrimination and make the Philippines a fair place for everyone.

500 Words Essay on Discrimination Of Indigenous Peoples In The Philippines

Understanding discrimination against indigenous peoples.

In the Philippines, there are many groups of people who have lived on the islands for thousands of years. These people are known as indigenous peoples. They have their own ways of life, languages, and traditions. But, they often face unfair treatment just because they are different from the majority of people in the country. This unfair treatment is called discrimination. It means treating someone badly for reasons that are not fair.

The Struggle for Land

One big problem for indigenous peoples is the fight over land. They have lived on their land for a very long time, but sometimes other people want to take it. These other people might want to use the land to build houses, grow crops, or start businesses. When this happens, the indigenous people can lose their homes and the places they use to find food or perform their traditions. This is not right because the land is a big part of who they are and how they live.

Lack of Respect for Culture

Indigenous peoples have their own cultures, which are the special ways they do things and understand the world. Sometimes, other people do not respect these cultures. They might think that these ways are not important or not as good as their own. This can make indigenous people feel like they are not valued and that their way of life is in danger.

Education and Jobs

Another problem is getting a good education and finding jobs. Often, schools are far away from where indigenous peoples live, and the schools might not teach about their culture. This can make it hard for children to learn and feel proud of where they come from. When it comes to jobs, many companies do not hire indigenous people, or they pay them less money. This is not fair because everyone should have the same chance to work and make a living.

Health and Well-being

Health is another area where indigenous peoples face challenges. They might not have easy access to doctors or medicine. Also, because they are often poor, they cannot always afford to pay for healthcare. This means they can get sick more often and have a harder time getting better.

To fix these problems, it is important for everyone to learn about and respect indigenous cultures. People should also speak up when they see discrimination happening. The government can help by making sure indigenous peoples have the same rights to land, education, jobs, and healthcare as everyone else.

In conclusion, indigenous peoples in the Philippines face many unfair situations. They struggle to keep their land, have their cultures respected, get good education and jobs, and stay healthy. But if people work together and treat each other fairly, we can make the Philippines a better place for everyone, including indigenous peoples. It is important to remember that even though we are different, we all deserve to be treated with respect and kindness.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Disney World

- Essay on Marijuana Legalization As A Form Of Medicine

- Essay on Diving

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How We Work

Support Office

What is atrocity prevention?

Bringing communities together

For states, by states

GAAMAC around the world

Community members

Thematic Initiative

Resource Library

Join GAAMAC

Contact the Support Office

Preventing hate speech, incitement and discrimination: the case of the Philippines

Hate speech, incitement to violence and discrimination in the Philippines, in particularly against Filipino Muslims and the Bangsamoro people, are deeply rooted in the country’s colonial and post-colonial history. A case study by GAAMAC’s Asia Pacific Study Group examines these causes and makes recommendations to address them.

In the Philippines, hate speech, incitement to violence and discrimination remain very serious concerns given the strong prejudice among the Christian Filipino majority against the Bangsamoro people; and the deep-seated animosity between Indigenous Peoples and Muslim communities, on the one hand, and Christians, on the other.

While hate speech against the Bangsamoro people is not new, the rise of online and social media use added a new dimension to the perpetuation of prejudices against them, as seen in the large volume of anti-Muslim messages circulated during and after the Mamasapano incident in January 2015 and the Marawi siege in May 2017. Notably, the messages online during these events mirror the antiMuslim prejudice portraying them as “traitors”, “violent savages”, “pirates”, “assassins”, “enslavers”, “cruel”, and “uncivilized” introduced during the Spanish and American colonisation and continued by the post-colonial Philippine state.

Hate speech witnessed during the Mamasapano incident and the Marawi siege cannot be divorced from a broader analysis of the historical and structural discrimination and injustices experienced by the Bangsamoro people. Hate speech during these two events has in turn undermined the overall formal and informal peace processes that sought to address the root of incitement to violence and discrimination.

An insufficient penal approach

The Philippine government has not enacted a law against hate speech, incitement to violence and discrimination. There are no legal provisions against such kinds of speech as jurisprudence on freedom of expression cases mainly focus on libel, defined as the public and malicious imputation of an act that tends to discredit or dishonour another person and which currently exists under the Revised Penal Code. This penal law on libel was expanded by the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 (Republic Act No. 10175) to apply to acts “committed through a computer system or any other similar means which may be devised in the future”.

In the context of state actors themselves being central to hate speech and discrimination and of the real threat of the use of laws to perpetuate marginalisation and to suppress dissent, a penal approach, such as criminalisation of libellous speech, offline and online, and its impact on freedom of speech remain a serious concern. Indeed, the United Nations Human Rights Council held that the Philippines’s criminalisation of libel does not conform with the freedom of expression clause of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Beyond penalization, a transformative approach

Considering hate speech and discriminations within the broader and historical context, civil society efforts emphasise a positive and transformative approach which is restorative and retributive rather than penal. These efforts have been pursued parallel to and at times jointly or in coordination with government agencies.

Government efforts, both at the national and the regional level, are also focused on transitional justice and reconciliation efforts, particularly in the creation of the Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) in 2014, “mandated to undertake a study and to make recommendations with a view to promote healing and reconciliation of the different communities that have been affected by the conflict.”

Many recommendations from the report of the TJRC, however, have not yet been acted upon.

Following the passage and ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law in 2019 and the establishment of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, there is a huge burden on the national government in taking immediate, concrete, and visible steps to deliver the dividends of peace to the Bangsamoro people and the rest of the country. Efforts must also be made to sustain the momentum of the peace process, including in building trust and understanding among different religious and ethnic groups in Mindanao and the Philippines.

This article is a summary of the chapter on the Philippines in the report Preventing Hate Speech, Incitement, And Discrimination – Lessons On Promoting Tolerance And Respect For Diversity In The Asia Pacific.

Read the chapter on the Philippines

Read the full report

Make sure you do not miss any updates! Sign up to our bimonthly newsletter.

Recent posts

High-Level Conference on “Building a Common Agenda for Prevention in the Western Balkans”

The Western Balkans Coalition for Genocide and Mass Atrocity Crimes Prevention, the Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC), and Impunity Watch organized a High-Level Conference on “Building a Common Agenda for Prevention in the Western Balkans” in Podgorica from 21-22 March 2024.

Press release: Strengthening national prevention efforts – the media and the National Gendarmerie

With the support of GAAMAC, CADHA will be raising awareness among the media and the National Gendarmerie of Côte d’Ivoire to strengthen their skills in the prevention of genocide and mass atrocities on March 5 and 14, 2024 in Abidjan.

UNESCO organizes workshops for GAAMAC Africa Working Group

21 February 24

UNESCO, a GAAMAC Informal Alliance, has organized two online workshops on Strengthening genocide prevention through education in Africa with the support of GAAMAC.

Privacy Overview

- Subscribe Now

Racism in the Philippines: Does it matter?

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The recent spike in racist violence in the United States along with the anti-Muslim “war on terror” led me to wonder about race and racism in the Philippines.

The experience of racism is nothing new among Filipinos, nor is it so simple. The term “Filipino” after all began as the racial designation for Spaniards born in the Philippines to distinguish them from those born in the Peninsula.

Because of the accident of birth, Filipinos, like Americanos, were regarded as “creoles.” Raised in the supposedly “backward” conditions of the colonies, creoles were treated as a race apart, seen by Europeans as beneath them. It was only in the last years of nineteenth century that youthful nationalists began to re-appropriate “Filipino.” They changed it from a racist term into a nationalist watchword to mean all those who suffered the common fate of Spanish oppression, and who felt a common stake in the future of the colony.

Nick Joaquin has written suggestively about “Filipino” as a creole identity located in between the white European on top and the dark skinned indio below. Not quite white and not quite native, the racial ambivalence that inheres in “Filipino” is everywhere evident today. On the one hand, there is a tendency to accept white norms of beauty and normalcy that denigrate non-white others. On the other hand, there is also a fascination with and acceptance of these same others once Filipinos come to know them.

The same can be said about white people.

Filipinos move between suspicion and trust, rejection and acceptance, depending on their relationship with them. Even Filipino-Americans with their white-like accents and behavior, are greeted with a similar ambivalence, regarded as estranged kin as much as foreign presences. We can see this, too, in the treatment of South Asians. The distinctions between and among Indians, Pakistanis and Sri Lankans tend to be conflated into the sinister turban-wearing, child-snatching, “5/6” figure of the “Bombay.” At the same time, there are few obstacles to their integration into successful members of rural and urban communities.

Koreans, Arabs and African-Americans are treated with similar ambivalence.

Their appearance and smells are the subject of deprecating comments meant to mark out their foreigness. But they are rarely targeted for violent assaults and manage to live relatively undisturbed in Filipino neighborhoods. The Japanese were once hated in the aftermath of World War II, but that memory has been largely set aside and they are now seen as friends and allies. There are no state-sanctioned policies or other institutional barriers to keep foreigners from inter-marrying with locals and living in the country. Their differences can be accounted for and they cease to pose a threat. Indeed, no anti-foreign riots have occurred, to my knowledge, since the seventeenth century pogroms against the Chinese.

Racial opportunists?

Among Filipinos then, racial feelings are loosely structured, unevenly policed and highly flexible. They run wide but shallow, capable of changing directions, largely dependent on social context. The thinness and contingency of race consciousness makes it seem as if Filipinos were racial opportunists.

As heirs of a racially liminal identity, it’s not surprising that Filipinos display racial sentiments that are characteristically protean. For example, the Philippines has a long tradition of anti-Chinese racism, as scholars such as Edgar Wickberg, Carol Hau and Richard Chu have pointed out. Spanish and American colonial policies cast the Chinese as foreign Others. Nonetheless, the Spaniards encouraged Christian conversion among the Chinese. They also promoted inter-marriage between Chinese men and Christianized native women as a way of assimilating the former. As a result, entire generations of Chinese mestizos emerged, many of whom made up the earliest generations of nationalists, including Rizal.

Yet mestizo nationalists, incorporating Spanish prejudices, were often virulently anti-Chinese themselves. This sort of nationalism yoked to anti-Sinicism dressed up as anti-comprador or anti-imperialist politics, is not entirely gone. It still rears its ugly head even within academic and literary circles today. The “Chinese,” imagined as an alien presence, is also seen as polluted and déclassé among the rich, and, in light of the conflict over the West Philippine Sea, grasping and greedy among everyone else.

American rule further heightened this sense of racial ambiguity. On the one hand, Americans invaded the Philippines in the wake of the most genocidal phase of white settler wars against Indians in the Southwest and at the height of anti-black lynching in many parts of the country. Many of the US officers who were veterans of the Indian wars did not hesitate to use the same exterminatory tactics on Filipino insurgents and civilians.

On the other hand, the Americans quickly realized they could not simply kill all Filipinos. They needed their help to end the war and govern the colony, and so embarked upon a policy of attraction and Filipinization. Dependent on the collaboration of Filipino creoles and mestizo elites, they could not afford to impose Jim Crow laws in the colony. Instead, socializing across racial lines, especially among colonial elites, became common. Where race relations were concerned, colonial Manila proved to be far more liberal than the segregated metropolis of Washington.

Still, the racist logic of colonial rule remained unassailable. It was encapsulated in the notion of “benevolent assimilation”: white Protestant males and females tutoring mestizo and brown Catholics and Non-Christian natives in the rudiments of Anglo-Saxon civilization. Filipinos came to incorporate these civilizational notions and saw themselves as more advanced than the non-Christian population of Moros and lumads. Filipino nationalism forged in the crucible of colonialism had an inescapably racist dimension.

Still, conflict always alternated with co-existence and cooperation in the relationship between these groups. As Patricio Abinales has pointed out, Muslim elites were far more politically integrated with the American colonial and Republican government than they had ever been under Spain and after Marcos. Religious differences were never simply cast in racial terms, but always inflected by class, ethno-linguistic and regional distinctions. They were often subsumed, at least in official discourse, by a nationalism that says: in the end, “we” are all Filipinos. However, as the current debates around the BBL show, the nationalization of minority groups tends to be provisional and tenuous. Many Filipinos still regard Moros either as a colonized population with lesser rights, or an alien people who threaten national sovereignty.

Dealing with lower classes

The use of racially tinged categories to both denigrate and embrace the Other continues to be a common practice among upper and middle class Filipinos when it comes to dealing with the lower classes. Thus are the poor often racialized, treated as if they were a different species altogether.

As in other countries, the outer limit of middle class life is defined by poverty. The “poor” exist as the accursed Other, living beyond the village gates. They are allowed inside only as servants. Like migrant workers in a foreign country, their movements in and out of the village are closely monitored and regulated by heavily armed security guards. Associated with ignorance and criminality, the poor pose a permanent existential threat to the middle class and the rich. The physical and cultural markers of class segregation – high walls, air conditioned cars, linguistic honorifics – regulate the proximity of the poor and neutralize the dangers coming from this putatively inferior race.

Take for example Vice President Jojo Binay and his family. They have been vilified in the press and social media for their corrupt practices. Mixed with these criticisms, though, is no small amount of racial animus. The Binays are seen as indio usurpers daring to claim for themselves mestizo social privileges. They stand accused not only of corruption but also of not knowing their place in the racial hierarchy.

The racialized denigration of the poor, however, has another side. They are also idealized in Catholic and nationalist discourses. For the Church, their abjection is construed as an invitation to exercise pity, or awa. Occasioning charitable acts, the poor can help us save our souls.

For nationalists, the poor comprise the majority and thus make up the “people.” They are thus not only the targets of development but also the agents of national liberation. The rural poor, along with non-Christian groups, are often fetishized as the repositories of cultural authenticity, of real Filipino “values” and pre-colonial “traditions.” This exoticizing regard for the poor and the non-Christian forms a durable substrate of nationalist fantasy. To wit: it is the poor and the non-Christians who are the real agents of historical change. Class differences can eventually be overcome to produce one race – a united nation as progressive as it is compassionate.

Today, skin color continues to serve as the gauge of social difference and the sign of class inequality. Light skinned mestizos – whether Chinese and European – tend to be endowed with considerable cultural capital regardless of their actual economic standing. The lightness of their skin serves as their calling card. It is the rare politician or celebrity – Nora Aunor comes to mind – who is not light skinned. Darker skinned folks become famous precisely by poking fun at their appearance, unless they are well-paid indios (think Manny Pacqiuao) or Filipino African-American athletes.

Light is still right: hence, the popularity of skin-lighteners and, for those who can afford it, cosmetic surgery to streamline bodily features along more Caucasian lines. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine any one of any social class preferring to look darker rather than lighter, to have a flatter rather than a straighter nose. Judging from the billboards that populate Manila, light skin continues to be the horizon of popular aesthetic aspiration. Lightness retains a certain socio-cultural caché, whereas darkness brings only ridicule or, at best, indifference.

Racial injustice

How can we understand the tenacity and flexibility of racial hierarchies? Why does race continue to be this vexed but ambiguous thing, omnipresent yet hard to pin down? And why does it even matter?

Race matters to the extent that racial injustice persists. In the US, white supremacy and the oppression of black people are two sides of the same racial coin. If anything, racism has taken on greater currency in the age of Obama. It is rooted in the unresolved legacy of slavery. If blacks are regarded as inferior to whites, it is because, for over 250 years, the former were legally available as the property of the latter. Slave labor is extorted and uncompensated work sanctioned by the State and exclusive to blacks. Simply put: to be white is to own your labor and its products; to be black is to be owned by whites. Despite a Civil War that abolished slavery and a civil rights movement that sought to restore blacks to full citizenship, problems of inequality and discrimination continue.

Small wonder, then, that first-generation immigrants – especially Filipinos – seeking to fit into the US quickly learn the language of racism and tend to identify upwards with the more dominant whites. The second generation, however, grows up in the US without the creole entitlement and anxieties of their parents. Instead, they are daily confronted with racial injustice and begin to identify with blacks and Latinos. The generational rift between first and second generation Filipino Americans in part comes out of a radically different understanding of the history and effects of racism and its close relation, sexism, in the US.

In the Philippines, the situation is, of course, different.

Given the absence of a history of racialized slavery, the problem of race tends to be folded into the language of class. The binary of white supremacy and black oppression are transmuted into the tension between the wealthy and the middle class versus the poor (and the non-Christian). Alternately, anti-Chinese racism also takes on a class character when the Filipino sees himself in the place of the poor native exploited by the wealthy predatory foreigner (even though, of course, most Chinese are neither wealthy nor predatory, much less foreign).

Once again, we see the protean nature of racial identification. The middle class can assume the position of the white colonizer when confronted with the dark Otherness of the poor. But it can also take on the position of the poor – the “people” in the nationalist imagination – when faced with what it considers to be an exploitive foreign presence. The post-colonial middle class, like its creole predecessor, seemingly can have it both ways. Historically in-between, it draws prestige from above when it feels menaced from below, and takes on prestige from below when threatened from above.

Prejudices vs OFWs

Let me end with one last example that shows why race matters.

This has to do with OFWs. Among Filipinos, they experience perhaps the most brutal forms of racial injustice, especially domestic workers. In places like Singapore or the Gulf States, they tend to live in slave-like conditions. Unprotected by local laws, they are subject to gross exploitation by recruiters, employers, and even Embassy personnel. They are also vulnerable to being trafficked and sexually abused. Symptomatic of this racial abjection is the way “Filipina” has come to be synonymous with “maid” or “care giver” in many places abroad.

Like slaves, OFWs are held captive, their movements severely restricted and monitored. Their employers usually keep their passports to prevent them from leaving. They are given very limited days off, or none at all, and they are often forbidden to inter-marry with locals. Those who escape are referred to as “runaways,” as if they were slaves. Local courts treat them as fugitives guilty of breaking their contracts, rather than as victims of abuse. When caught, they are subject to imprisonment and deportation.

Thus are OFWS positioned by the host country as a race apart. Their slave-like conditions reveal with great clarity the tight chains that bind racism with the gendered exploitation of labor that is an integral – and tragic – part of our current history. – Rappler.com

Vicente L. Rafael teaches history at the University of Washington, Seattle .

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}.

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Published daily by the Lowy Institute

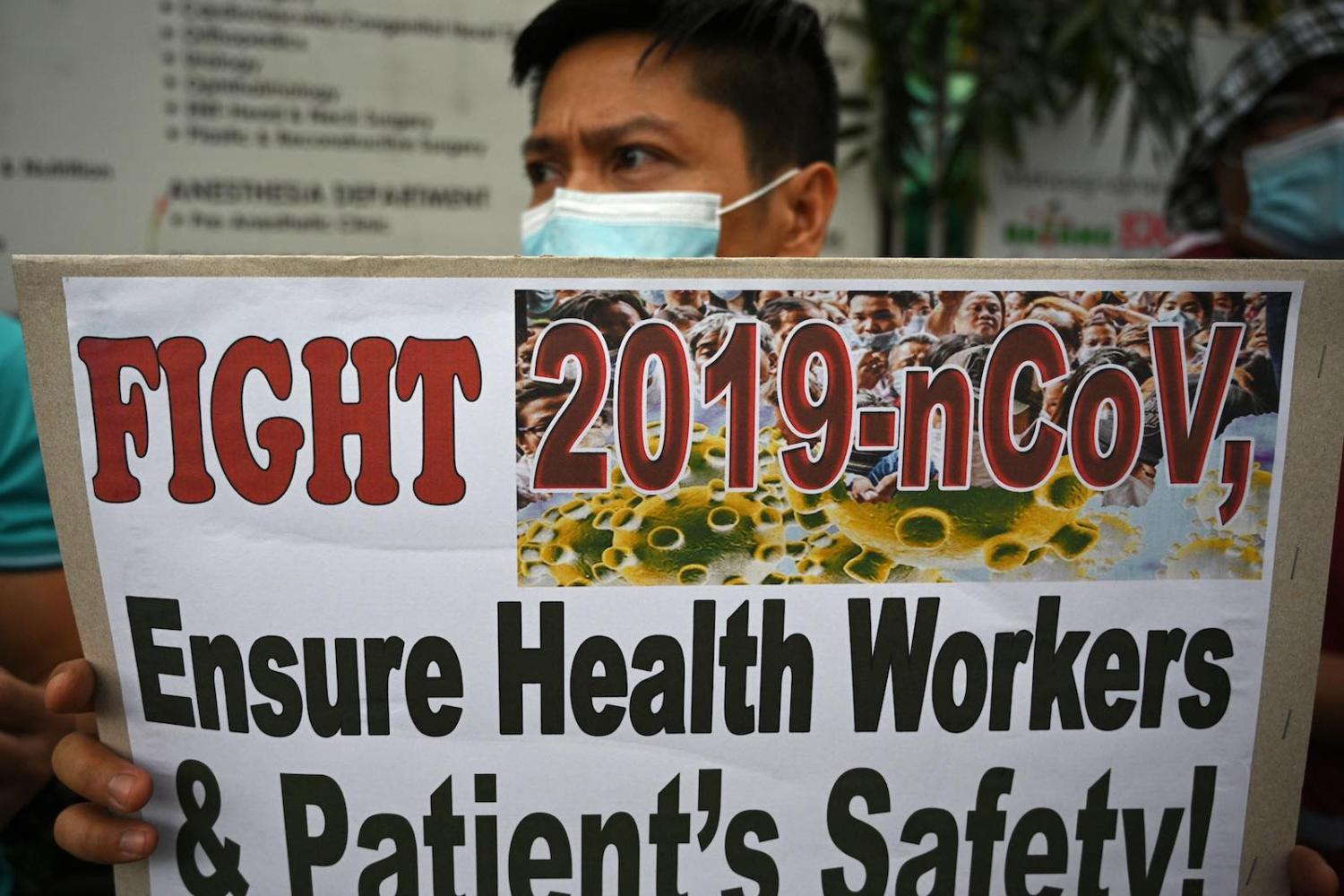

The politics of racism as the Philippines struggles with coronavirus

Rodrigo Duterte and his backers appears to be exploiting the public health crisis to wedge opponents at home.

- Philippines

- Coronavirus

It would almost seem nothing could further divide politics and society in the Philippines – and then the coronavirus arrived. Only three cases have been confirmed in the country, but rampant fears and unchecked anxieties are playing into the existing division.

The first half of President Rodrigo Duterte’s term consistently forced that gap wider, with disputes over the deadly war on drugs, attacks on the media, the judiciary, and more recently with the collapse in US relations . A public health crisis joins an already crowded set of headlines.

The Philippines is somewhat of an outlier in the region in its rhetoric towards China. While Duterte has stopped short of a “solidarity” visit to Beijing, unlike Cambodian counterpart Hun Sen , his government faces repeated accusations of courting goodwill with China at the expense of Filipinos.

Critics say the government had dragged its feet in issuing a travel ban on China and its territories in the wake of the virus outbreak, putting it out of step with much of Southeast Asia. While the utility of such bans is controversial, the optics gave the “yellows”, as the anti-Duterte opposition are known, fuel to the argument that the President is ceding sovereignty to China, first in the South China Sea, and now in public health.

It’s a claim that has followed Duterte since the early days of his leadership. Taking office in 2016 just weeks before an international tribunal ruling in favour of the Philippines’ claim to disputed waters in the South China Sea, the country’s official stance towards Beijing softened, prompting protest from left-leaning activists. A preoccupation with securing investment has high-profile critics wondering aloud if infrastructure projects could be “trojan horses with dire consequences for the Philippines”.

Now, by tying its initially slow response to the coronavirus to investment, the Duterte administration is struggling to establish credibility in a fight against anti-Chinese racism.

Authorities ordered tighter screening of passengers arriving in the country from Hubei province in early January but struggled to maintain control on information and public fears as the crisis escalated in China and then across Southeast Asia.

A slow down on flights between the Philippines and Wuhan temporarily allayed fears, but as the first known case in the Philippines was confirmed 30 January, public fears spiked. The 38-year-old Chinese national is believed to have contracted the virus in Wuhan, his home city. Just days later, a 44-year-old Chinese national died in a Manila hospital – the first coronavirus related death outside of China.

An order in late January to repatriate Filipinos based in China helped to stem criticism of the Duterte administration momentarily. Planes sent from Manila to bring nationals home would be loaded with donations of supplies for Hubei province’s hospital, Secretary of Foreign Affairs Teddy Locsin Jr. wrote in a typically expletive-laden Tweet: “ China helps us we help China ”.

When our plane goes to Hubei to evacuate Filipinos who want to leave plane will be loaded with food items, masks if we find any, everything. And DFA will pay for it because I don't give a shit about audit procedures in this case. China helps us we help China. I have spoken. https://t.co/bZL2jwGKAh — Teddy Locsin Jr. (@teddyboylocsin) February 7, 2020

Less kind words have been reserved for left wing critics. In an almost invert of domestic discourse everywhere, the hard right in the Philippines has consistently accused the left of “Sinophobia” in its demands to close borders. Conservative columnist for the Manila Times, Rigoberto D. Tiglao, laid out the argument in a column last week, dismissing critics as “rabidly anti-Duterte and anti-Marcos and racist.

And Tiglao has a point. Reports from across the world of heightened prejudice against the Chinese diaspora are a foolish and dispiriting response to the virus outbreak. Yet even so, the credibility of those lawmakers, journalists and conservative activists who otherwise offer fulsome support of Duterte’s other domestic policies – including the President’s well-known pattern of invective – seems stretched when it comes to racism.

Chinese-Filipinos are the country’s largest ethnic minority, and are well-represented in the upper echelons of the business and political community. Still, the long history has not shielded them from fears.

Indeed, Duterte’s own comments muddy the waters. He has linked anti-racist comments with the importance of China as a trade partner. “China has been kind to us, we can only also show the same favour to them. Stop this xenophobia thing,” he said shortly after the death of a Chinese national in early February. By making coronavirus and criticisms about the public health response an identity issue, it appears Duterte and his aligned supporters seeking to wedge the left by its own language and values. That criticism should be heard — but it’s the ethnic-Chinese minority who should be listened to.

Chinese-Filipinos are the country’s largest ethnic minority, and are well-represented in the upper echelons of the business and political community. Still, the long history has not shielded the community from fears. Binondo, Manila’s Chinatown and the oldest in the world, briefly became a hub for rumoured cases prior to the first confirmation.

Col Tiu, an ethnically-Chinese Filipina, wrote at length for Rappler about the stress and ostracisation the community is feeling. “I have never seen the Chinese be more sorry just for being Chinese. I have also never felt more ashamed for having a Chinese family name,” she said, noting cases of discrimination such as Chinese students singled out for self-quarantine by schools.

The last word should go to Teresita Ang See, a leader with the Chinese-Filipino community group Kaisa Para sa Kaunlaran. She is convinced that the associated racism is more detrimental to the country than a public health crisis. As she puts it : “The ‘you vs. us’ attitude, finger-pointing, and racism are deadlier and cause more permanent damage than the virus we are now fighting collectively as one humanity.”

Related Content

Southeast Asian democracies in declining health amid Covid-19

You may also be interested in, no end in sight for germany’s troubles with huawei, nz and australia: big brothers or distant cousins, why china tripled its heavy truck shipments to central asia: unravelling the influence of russia’s war in ukraine.

DISCRIMINATION

Discrimination is harming someone’s rights simply because of who they are or what they believe. discrimination is harmful and perpetuates inequality. it strikes at the very heart of being human..

We all have the right to be treated equally, regardless of our race, ethnicity, nationality, class, caste, religion, belief, sex, gender, language, sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics, age, health or other status. Yet all too often we hear heartbreaking stories of people who suffer cruelty simply for belonging to a “different” group from those in positions of privilege or power.

Discrimination occurs when a person is unable to enjoy his or her human rights or other legal rights on an equal basis with others because of an unjustified distinction made in policy, law or treatment. Amnesty International’s work is rooted in the principle of non-discrimination. Working with communities across the world, we challenge discriminatory laws and practices to ensure all people can enjoy their rights on an equal basis.

Discrimination can take various forms:

Direct discrimination is when an explicit distinction is made between groups of people that results in individuals from some groups being less able than others to exercise their rights. For example, a law that requires women, and not men, to provide proof of a certain level of education as a prerequisite for voting would constitute direct discrimination on the grounds of sex.

Indirect discrimination is when a law, policy, or practice is presented in neutral terms (that is, no explicit distinctions are made) but it disproportionately disadvantages a specific group or groups. For example, a law that requires everyone to provide proof of a certain level of education as a prerequisite for voting has an indirectly discriminatory effect on any group that is less likely to have achieved that level of education (such as disadvantaged ethnic groups or women).

Intersectional discrimination is when several forms of discrimination combine to leave a particular group or groups at an even greater disadvantage. For example, discrimination against women frequently means that they are paid less than men for the same work. Discrimination against an ethnic minority often results in members of that group being paid less than others for the same work. Where women from a minority group are paid less than other women and less than men from the same minority group, they are suffering from intersectional discrimination on the grounds of their sex, gender and ethnicity.

What drives discrimination?

At the heart of all forms of discrimination is prejudice based on concepts of identity, and the need to identify with a certain group. This can lead to division, hatred and even the dehumanization of other people because they have a different identity.

In many parts of the world, the politics of blame and fear is on the rise. Intolerance, hatred and discrimination is causing an ever-widening rift in societies. The politics of fear is driving people apart as leaders peddle toxic rhetoric, blaming certain groups of people for social or economic problems.

Some governments try to reinforce their power and the status quo by openly justifying discrimination in the name of morality, religion or ideology. Discrimination can be cemented in national law, even when it breaks international law – for example, the criminalization of abortion which denies women, girls and pregnant people the health services only they need. Certain groups can even be viewed by the authorities as more likely to be criminal simply for who they are, such as being poor, indigenous or black.

Toxic rhetoric and demonization

The politics of demonization is on the march across many parts of the world. Political leaders on every continent are advocating hatred on the grounds of nationality, race or religion by using marginalized groups as scapegoats for social and economic ills. Their words and actions carry weight with their supporters; the use of hateful and discriminatory rhetoric is likely to incite hostility and violence towards minority groups.

The dire consequences of this type of demonization have been witnessed in Myanmar, where decades of persecution culminated in 2017 with over 700,000 predominantly Muslim Rohingya having to flee to neighbouring Bangladesh after a vicious campaign of ethnic cleansing .

In the Philippines , the phenomenon of red-tagging has been happening for decades now but has intensified in the last few years under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Following the breakdown of peace talks between the government and the CPP in 2017, Duterte’s subsequent Executive Order (EO) 70 provides for a “Whole-of-Nation approach in defeating the Local Communist Terrorist Groups” and led to the creation of the NTF-ELCAC. Observers point to this moment in time as the beginning of a renewed campaign of red-tagging, threats and harassment against human rights defenders, political activists, lawyers, trade unionists and other targeted groups perceived to be affiliated with the progressive left.

Some key forms of discrimination

Racial and ethnic discrimination.

Racism affects virtually every country in the world. It systematically denies people their full human rights just because of their colour, race, ethnicity, descent (including caste) or national origin. Racism unchecked can fuel large-scale atrocities such as the 1994 genocide in Rwanda and more recently, apartheid and ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya people in Myanmar.

In India, members of the Dalit community are targeted, by members of dominant castes, for a range of human rights abuses. These crimes, which include gang rapes, killings and the destruction of their homes, often go uninvestigated by the police because of discriminatory attitudes which do not take crimes against Dalits seriously.

Amnesty International has also documented widespread discrimination faced by millions of Roma in Europe, including the threat of forced evictions, police harassment and the segregation of Romani children in school.

Discrimination against non-nationals, sometimes known as xenophobia

but discrimination against non-nationals is frequently based on racism or notions of superiority, and is often fuelled by politicians looking for scapegoats for social or economic problems in a country.

Since 2008, South Africa has experienced several outbreaks of violence against refugees, asylum seekers and migrants from other African countries, including killings, and looting or burning of shops and businesses. In some instances, the violence has been inflamed by the hate-filled rhetoric of politicians who have wrongly labelled foreign nationals “criminals” and accused them of burdening the health system.

Discrimination has also been a feature of the response of authorities to refugees and asylum seekers in other parts of the world. Many people in countries receiving refugees and asylum-seekers view the situation as a crisis with leaders and politicians exploiting these fears by promising, and in some cases enacting, abusive and unlawful policies.

For example, Hungary passed a package of punitive laws in 2018 , which target groups that the government has identified as supporting refugees and migrants. The authorities have also subjected refugees and asylum seekers to violent push-backs and ill-treatment and imposed arbitrary detention on those attempting to enter Hungarian territory.

We at Amnesty International disagree that it is a crisis of numbers. This is a crisis of solidarity . The causes that drive families and individuals to cross borders, and the short-sighted and unrealistic ways that politicians respond to them, are the problem.

Discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people

Everywhere in the world, people face discrimination because of who they love, who they are attracted to and who they are. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people risk being unfairly treated in all areas of their lives, whether it’s in education, employment, housing or access to health care, and they may face harassment and violence.

Some countries punish people for their sexual orientation or their gender identity with jail or even death. For example, in October 2019, Uganda’s Ethics and Integrity Minister announced that the government was planning to introduce the death penalty for consensual same-sex sexual acts.

In 2019, Amnesty International documented how gay and trans soldiers in South Korea face violence, harassment and pervasive discrimination due to the criminalization of consensual sex between men in the military; and examined the barriers to accessing gender-affirming treatments for transgender individuals in China . We also campaigned to allow Pride events to take place in countries such as Turkey, Lebanon and Ukraine.

It is extremely difficult, and in most cases, impossible for LGBTI people to live their lives freely and seek justice for abuses when the laws are not on their side. Even when they are, there is strong stigma and stereotyping of LGBTI identities that prevents them from living their lives as equal members of society or accessing rights and freedoms that are available to others. That’s why LGBTI activists campaign relentlessly for their rights: whether it’s to be free from discrimination to love who they want, have their gender legally recognized or to just be protected from the risk of assault and harassment.

See here for more information about Amnesty International’s work on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex rights.

Gender discrimination

In many countries, in all regions of the world, laws, policies, customs and beliefs exist that deny women and girls their rights.

By law, women cannot dress as they like (Saudi Arabia, Iran) or work at night (Madagascar) or take out a loan without their husband’s signature (Equatorial Guinea). In many countries, discriminatory laws place limits on a woman’s right to divorce, own property, exercise control over her own body and enjoy protection from harassment.

In the ongoing battle for justice, hundreds of thousands of women and girls take to the streets to claim their human rights and demand gender equality. In the USA, Europe and Japan, women protested against misogyny and abuse as part of the #MeToo marches. In Argentina, Ireland and Poland, women demonstrated to demand a stop to oppressive abortion laws. In Saudi Arabia, they called for an end to the driving ban, and in Iran, they demanded an end to forced hijab (veiling).

All over the world, women and girls have been at the forefront of demands for change.

Yet despite the stratospheric rise of women’s activism, the stark reality remains that many governments around the world openly support policies, laws and customs that subjugate and suppress women.

Globally, 40% of women of childbearing age live in countries where abortion remains highly restricted or inaccessible in practice even when allowed by law, and some 225 million do not have access to modern contraception.

Research by Amnesty International confirmed that while social media platforms allow people to express themselves by debating, networking and sharing , companies and governments have failed to protect users from online abuse, prompting many women in particular to self-censor or leave platforms altogether.

However, social media has given more prominence in some parts of the world to women’s calls for equality in the workplace, an issue highlighted in the calls to narrow the gender pay gap, currently standing at 23% globally. Women worldwide are not only paid less, on average, than men, but are more likely to do unpaid work and to work in informal, insecure and unskilled jobs. Much of this is due to social norms that consider women and their work to be of lower status.

Gender-based violence disproportionately affects women, ; yet it remains a human rights crisis that politicians continue to ignore.

Discrimination based on caste

Discrimination based on work and descent (also referred as caste discrimination) is widespread across Asia and Africa, affecting over 260 million people, including those in the diaspora. Owing to their birth identity, people from these communities are socially excluded, economically deprived and subjected to physical and psychological abuse. Discrimination based on work and descent is deeply rooted in society, it manifests itself in everyday lives, in individual perceptions to culture and customs, in social and economic structures, in education and employment, and in access to services, opportunities, resources and the market. Discrimination is perpetuated from generation to generation, and is in some cases deeply internalized, despite the existence in some countries of laws and affirmative action to tackle it. Amnesty International is committed to work in tandem with partners in advocating for the rights of communities affected on the basis of work and descent.

Discrimination based on disability

As many as 1 in 10 people around the world lives with a disability. Yet in many societies, people with disabilities must grapple with stigma, being ostracized and treated as objects of pity or fear.

Developing countries are home to about 80 per cent of people with disabilities. The overwhelming majority of people with disabilities – 82 per cent – live below the poverty line. Women with disabilities are two to three times more likely to encounter physical and sexual abuse than women without disabilities.

In Kazakhstan , current laws mean that thousands of people with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities have been declared “incapable” by law and put in the care of a guardian. Under this system they cannot exercise their rights and are not able to challenge the decision in court.

Amnesty International has also documented serious human rights abuses suffered by people with disabilities in Somalia , where they are at risk of forced marriage, rape and forced evictions.

The solution: What is Amnesty calling for?

Governments to:

- Get rid of discriminatory laws and release anyone who is in prison because of them.

- Protect everyone – whoever they are – from discrimination and violence.

- Introduce laws and policies that promote inclusion and diversity in all aspects of society.

- Take action to tackle the root causes of discrimination, including by challenging stereotypes and attitudes that underpin discrimination.

Working Against Discrimination in the Philippines

Become an amnesty supporter.

- Philippines

Southeast Asia’s Most Gay-Friendly Country Still Has No Law Against LGBT Discrimination

A t first glance, the deeply Catholic Philippines can seem surprisingly LGBT-friendly . In a nation of 110 million people, more than 110,000 showed up last week to Quezon City’s Pride festival , making it by far the largest LGBT congregation in Southeast Asia. The country also ranks highest in the region for LGBT social acceptance —according to a 2021 global index —and it’s made significant strides over the years toward greater inclusivity and equality.

And yet, for more than two decades, a bill that would criminalize discrimination based on one’s sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, or sex characteristics ( SOGIESC ) has languished in the Philippines’ Congress. Year after year, it’s practically become an annual tradition for legislation on the matter to be reintroduced and rejected, leaving LGBT people in many parts of the country with no legal recourse when they’re discriminated against.

Read more: A Year After Singapore Decriminalized Gay Sex, Its LGBT Community Turns Attention to Family

While many cities across the country have already instituted local ordinances to make SOGIESC-based discrimination illegal, Irish Inoceto, a Filipino LGBT activist and former employee of the Philippine Supreme Court, tells TIME that they have “no teeth at all” and that she has seen firsthand just how overdue and glaringly necessary such a nationwide law is.

Last October, Inoceto received a message on Facebook from an 11th grader just weeks before students were to be required back in classrooms after two years of COVID-prompted remote learning . The student, a transgender woman in Iloilo City, some 280 miles southeast of Manila, had met Inoceto through one of the routine LGBT rights seminars Inoceto facilitated across Iloilo City, where she used to be based. The student, who had attended some classes in person during a hybrid-remote period, told Inoceto that the school principal summoned her personally to say that men should not wear bras; she also said a school security officer policed her uniform. Meanwhile, another student at the same school who also identifies as a transgender woman similarly reached out to Inoceto to tell her that the principal rounded up all the students in her grade and declared that bakla (gay men) with long hair must cut it or be barred from school.

“The length of my hair is not the basis for my schooling,” the latter student, who is now 19 and requested anonymity for fear of further discrimination, tells TIME.

The situation prompted Inoceto to write to the school on both students’ behalfs. She cited Iloilo City’s own anti-discrimination ordinance that passed in 2018 , but she says her letter was ignored. Only after visiting the principal in person did Inoceto ultimately prevail in getting the school to back down on its attempts to curb both students’ gender expression. Any relief for Inoceto, however, was short-lived. The ordeal thrust her into the national spotlight and set in motion a saga that would ultimately force her to flee the country, where she continues to advocate for the national anti-discrimination bill to be passed.

Inoceto, who is now 46 years old, has spent half her life watching Philippine legislators fail to create a national anti-discrimination law for the LGBT community. Legislative records show the first version of what would later come to be known as the SOGIE Equality Bill was filed in the Philippine House of Representatives on Jan. 26, 2000. Successive Congresses have seen the bill progress through the legislative process to varying degrees, only to meet the same fate: at best, the entire lower chamber might approve it, only for the upper chamber—the Philippine Senate—to let it stall in deliberations.

The most recent version of the bill in the Senate would outlaw SOGIESC-based discriminatory practices like refusing admission to or expelling a person from schools, or imposing harsher than normal disciplinary sanctions on students. If passed, violators may pay a fine as high as 250,000 Philippine pesos ($4,535) or be jailed for as long as six years.

But the bill faces steep political resistance, particularly from Christian fundamentalists who, despite constituting a minority of the population compared to the Philippine’s overwhelming Catholic majority, represent a potent political force in the country : megachurches have galvanized fiercely loyal followings and fostered political power through electoral endorsements and the fielding of their own candidates.

Read more: In the Philippines, You Can Be Both Openly LGBT and Proudly Catholic. But It’s Not Easy

Opponents of the SOGIE Equality Bill have been accused of promulgating disinformation online as well as in the halls of Congress to obstruct its passage.

Two of the most vocal figures in the legislative efforts to block the bill are father and son duo Eddie and Joel Villanueva—a representative and senator, respectively. The elder Villanueva, who is also the founder of the Jesus is Lord megachurch, has describe the bill as “ imported ,” saying it doesn’t represent Filipino values, while the younger Villanueva has accused the bill of being a precursor to “ same-sex marriage .”

Reyna Valmores, chair of the Philippine LGBT rights group Bahaghari, has attended deliberations of the bill in the Philippine House as a resource person. She tells TIME the hearings can often feel like a “circus” of disinformation. “We have elected officials talking about how the SOGIE Equality Bill is going to legalize bestiality, is going to legalize having sex robots, and some other such nonsense.”

“It’s a matter of debates in Congress,” Valmores says. “But for many people, it’s a matter of survival.”

Soon after helping the two students in Iloilo City, Inoceto began to be targeted at a national scale—highlighting some of the extreme measures taken by prominent opponents of LGBT advocacy in the country.

Her name appeared in broadcasts from the Sonshine Media Network International, a television station owned by Apollo Quiboloy —a Philippine megachurch leader who is on the FBI’s most-wanted list for charges of sex trafficking women and children. Two anchors of a show on the network, Lorraine Badoy and Jeffrey “Ka Eric” Celiz, claimed that Inoceto was a member of the local communist insurgency group and has been using LGBT issues—such as her opposition to the gendered haircut policy—to recruit students from the Iloilo school. (TIME spoke to multiple students who denied that they had been recruited by Inoceto in any way.)

The sudden attention was confusing and frightening: “I’m an activist, but I’m not a big-time activist,” Inoceto tells TIME. “I work after hours and on weekends on my advocacy. So I was like, ‘Why me? And why issues on trans women students?’”

Red-tagging —a McCarthyism-like tactic of falsely labeling people as communists historically used in the Philippines to silence critics of the government, which has sometimes even led to victims being killed—has more and more been used against LGBT advocates in recent years. (Valmores from Bahaghari has also been red-tagged.)

Read more: You’ve Probably Heard of the Red Scare, Here’s the History You Didn’t Learn About the Anti-Gay ‘Lavender Scare’

After the broadcast, the country’s Commission on Human Rights issued a statement expressing concern over the anchors’ remarks, adding that the narrative they used “only serves to perpetuate the already disadvantageous plight of the LGBT who frequently face stigma, discrimination, and gender-based violence in our society.”

But that wasn’t the end of it. Inoceto saw her face posted across tarpaulins in the city, and her identity spread on social media. She even says her mother was visited by people who claimed to be police officers, asking her to stop her LGBT activism.

Concerned over the risks to her and her family’s safety, Inoceto says she applied for political asylum in France, where she is currently staying. She’s convinced that if the SOGIE Equality Bill had already been passed, she would have been protected from her harassment. “Right out the bat I was discriminated [against] because I was working towards inclusion,” she says.

Still, despite all the obstacles and dangerous disinformation wielded against the LGBT movement, Inoceto remains hopeful that the anti-discrimination bill in the Philippines will eventually pass—but not without sustained pressure put on the groups that are standing in its way. “Rights are fought for and won after so much struggle after all,” she says. “We just need to be stronger. In the meantime, we keep fighting the good fight.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Commercial Law

- Constitutional Law

- Criminal Law

- Law Related Discussion

- Legal Ethics

- Procedural Law

- Special Penal Laws

- Why Is SOGIE Bill Important? Understanding SOGIE Bill Through Historical, Legal, And Egalitarian Perspectives

by RALB Law

Why is SOGIE Bill important? In this article, we shall discuss the aforesaid topic. The equal protection article of the 1987 constitution , in particular, is intended to be fulfilled by the SOGIE [ Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Expression ] Equality Bill. It affirms that LGBTQ++ people are on an equal footing with everyone else and guarantees that their rights are upheld.

Law, Equality, and Justice

No matter what their circumstances, everyone has the right to respect and protection because they are human beings, not things. Human rights are also innate to being a human person, regardless of our disability, gender, sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, religion, or any other status.

We are all equally entitled to human rights, which are interrelated, indivisible, and interdependent. (What are human rights?) But nowadays, a growing threat to human beings’ rights is gradually spreading like wildfire in the whole world; it’s called Discrimination.

Why is SOGIE Bill important?

The bill also recognizes the Philippines’ obligations under international law, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Thus, it acknowledges that it is both a national and an international obligation to prevent prejudice against LGBTQ++ people.

In matters of gender and gender equality , among others, t his paper discusses how we can further understand the SOGIE Bill, also known as Senate Bill No. 689, “An An Act Prohibiting Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity or Expression (Sogie) and Providing Penalties Therefor”, through three different perspectives namely: Historical, Legal and Egalitarian. This essay also suggests recommendations on how to fill in the gaps and lapses of the bill’s current draft.

Historical Perspective

This paper’s historical perspective discusses the emergence of the LGBTQ ( lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning ) community and/or LGBTQIA+(( LGBTQIA Studies: Research and topic suggestions )) ( lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual ) category in the Philippines, as well as its progress and development.

May be as a gender expression , w e could also talk about the foundations of anti-discrimination and/or protection laws in the Philippines, which commonly lean towards the context of secular morality, which introduces non-establishment and free exercise clauses.

Significant progress has been made in recognizing the rights of LGBTQIA+ members in the Philippines, not only as human beings but also as civil personalities . These issues have broad political and possibly legal support and equal rights .

These members, however, continue to face barriers to full equality with other citizens. Several Philippine cities and provinces have specific laws protecting these members from discrimination.

Yet, these laws are not always effective, and those responsible for enforcing them are not always effective. In 2017, the House of Representatives unanimously passed the Anti-Discrimination Bill, which seeks to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Nonetheless, owing to stalling tactics by conservative senators, the bill did not pass the Senate in 2019. Other senators have already proposed new legislation to protect these senators.(( SOGIE Equality Bill passes Senate committee; still in limbo due to anti-LGBTQIA senators ))

Although societal tolerance for this community is high, and despite the fact that some religious leaders have publicly condemned same-sex relationships, members are still fighting for something much more than tolerance: social equality.(( Position Paper of Pro-Life Philippines Foundation, Inc. on Anti-Discrimination Bills on SOGIE ))

Even though LGBTQIA+ people are under-represented in political and business leadership positions, media representation of them is accurate and sympathetic.

Despite pushback from conservative politicians and religious leaders, there are many LGBTQIA+ organizations which work towards the legalization of same-sex marriage , legal gender recognition, and nationwide anti-discrimination bill.

To further deepen our understanding of the awareness of how the LGBTQIA+ Community came to being, we must first understand the history of the said community.

Filipino LGBTQIA+ youth today may not be aware of the history of a community where they belong. Many have long disregarded the community’s roots in the conservative culture of the Philippines.

The first account of women and gender crossing men playing significant roles in the Philippines society was the Babaylan , a priestess who was a bounty of knowledge and spirituality. The babaylan even had the power to take over the barangay (village) in the absence of the datu (community leader).

There were some babaylan who were male called asog, who were free to have homosexual relations without societal judgment The asog led revolts against the oppression of the Spanish colonial period, using various incantations to command the strength of the revolt.

During the 300-year Spanish colonization of the Philippines, an ideological shift was on the horizon. The Spanish introduced patriarchy and the machismo concept from the indigenous matriarchy, making gender crossing a mocked practice.

It wasn’t long before effeminate men were looked down on as well, leading to the development of regional vernacular for what the Tagalog all bakla (gay man, also means “confused”, “cowardly”). The American colonization period further reinforced of Western conceptualization of gender and sexuality, cementing it in formal education.

After the Second World War ended in 1942, gay rights activist Justo Justo established the Home of the Golden Gays in 1975. It was intended to be a home for elderly gay men who had been kicked out by their families, primarily due to a lack of financial contribution.

It has evolved into a loving community of vibrant and distinct individuals. Unfortunately, the home was forced to close after Justo died in 2012. The women’s movement of the 1980s was a high point in the lesbian community’s struggle to be visible in public. In recent decades, the lesbian community has felt invisible and ignored.

Lesbian issues have been subsumed under women’s and feminist studies, which were previously heterosexual in nature, as well as the gay movement, which previously prominently conceptualized lesbian women as female versions of homosexual men.

As a result, the lesbian community wished to have their voices heard in the fight against dictatorship. Finally, the underground women’s organization MAKIBAKA issued a position paper on the movement’s sexual orientation issues.

Later in the 1990s, the issue of gender and sexuality became a primary concern in the women’s movement, resulting in the formation of The Lesbian Collective, LESBOND, Can’t Live in the Closet, and the first National Lesbian Rights Conference.

The first LGBTQIA+ pride march held in the Philippines on June 26, 1994, to mark the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Riot, is another significant event in the movement’s history.

Not only was the march the first of its kind in Asia, but also in the Philippines. The Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) Manila and the Progressive Organization of Gays in the Philippines (PROGAY Philippines) jointly planned this event. There were just sixty (60) participants in the said march.

The public saw members of the LGBTQIA+ community speaking out for equality on such a large scale for the first time as they marched from EDSA to Quezon Avenue to Quezon Memorial Circle in Quezon City.

The LGBT Non-Discrimination Policy Resolution was recently published by the Psychological Association of the Philippines (PAP) in October 2011. This came about in reaction to several letters, phone calls, and concerns about ethics against a licensed psychologist who suggested conversion treatment for kids who come out as gay or lesbian in order to have a “happy family life.”

This policy statement reaffirmed the community’s members’ inherent equality and dignity as well as their right to be free from discrimination based on their sexual orientation and gender expression.

The American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 position that same-gender sexual orientations are a healthy, non-disordered variation of human sexuality, love, and relationships was further reinforced by this resolution. In November 2014, the resolution was later translated into Tagalog.

The members now benefit from the work that their forebears’ brothers and sisters did to advance LGBTQIA+ visibility and rights. To attain equality, there is still considerable work to be done. The Philippines currently lacks a comprehensive anti-discrimination statute.

While some Philippine laws outright restrict gender expression and overlook gender identity in workplaces, others are occasionally utilized to coerce the members. Thankfully, House Bill 267, also known as the Anti-SOGIE Discrimination Act (or “SOGIE” Bill), was presented on June 30, 2016, by Geraldine B. Roman, the first transgender member of Congress.

Beyond laws and policies, the members are crucial to realizing this vision of equality because they fight stigma and maintain visibility.

Recently, the Philippines has joined the list of nations that have enacted measures to combat discrimination (European Youth Center, 2008). The first law in the Philippines to fight discrimination that is only motivated by ignorance, prejudice, and unfavorable preconceptions is the anti-discrimination law in Cebu [(2012) Cebu Daily News].

Since the Anti-Discrimination Law affects a wide range of Filipinos—including those of different genders, impairments, sexual orientations, ages, nationalities, and religions—the law’s approval is already a fantastic “first step” toward change.

The 1987 Philippine Constitution provides that “The State values the dignity of every person and guarantees full respect for human rights”.(( Article II, Section 11, 1987 Constitution )) It also provides that “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor shall any person be denied the equal protection of the laws.”(( Article III, Section 1, 1987 Constitution ))

Republic Act No. 9710, otherwise known as the Magna Carta of Women (MCW), provides that “All individuals are equal as human beings by virtue of the inherent dignity of each human person. No one should therefore suffer discrimination based on ethnicity, gender, age, language, sexual orientation, race, color, religion, political or other opinions, national, social or geographical origin, disability, property, birth, or another status as established by human rights standards”.(( Section 3, RA 9710 )).

LGBT applicants for civil service tests are not allowed to be discriminated against, according to a Civil Service Commission Memorandum, Circular No. 29-2010. Additionally, a clause that prohibits discrimination in the selection for promotion based on numerous factors, including gender, is included in the CSC’s Revised Policies on Merit and Promotion plan.

The National Police Commission, on the other hand, forbids discrimination in recruiting, selection, and appointment practices based on gender by Memorandum Circular 2005-02.

The Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) has released a Memorandum reaffirming people of varied SOGIs’ freedom to dress in accordance with their preferred sexual orientation and gender identity.

Additionally, 25 LGUs have passed anti-discrimination laws that forbid discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, namely:

- Barangays Bagbag,

- Greater Lagro and Pansol in Quezon City,

- Angeles City in Pampanga,

- Antipolo City,

- Bacolod City,

- Batangas City,

- Baguio City,

- Butuan City,

- Candon City,

- Dagupan City,

- Davao City,

- General Santos City,

- Malabon City,

- Mandaue City,

- Marikina City,

- Puerto Princesa,

- Quezon City,

- Vigan City,

- Municipality of San Julian in Eastern Samar,

- Province of Agusan del Norte,

- Province of Batangas,

- Province of Dinagat Islands,

- Province of Cavite, and

- Province of Iloilo.

How the SOGIE Bill is understood may depend on the arrival of secularism in the Philippines. In the Philippines, morality plays a significant role in the formulation of laws. In 2014, Nicolo Bernardo, in his Book entitled PhiLawsophia: Philosophy and Theory of Law with Philippines Laws and Cases , defined “morality” by giving a distinction between secular morality and religious morality.((Bernardo, N. F., & Bernardo, O. B. (2017). Law, Justice, and Equality in Philawsophia: Philosophy and theory of law))

In sovereign countries where there is no separation of church and state, such as Islamic states and the Vatican, the law must reflect what the established religion considers moral.

For states that follow the non-establishment clause, such as, ideally, the Philippines, secular morality known as “public morals” are legal considerations. It is a morality based on popular ideas, legal sources, and common aspirations expressed in policies rather than religion. Obedience to state law is a secular moral principle in and of itself.

The Philippines is a secular state that is friendly to religions (Batalla and Baring, 2019). Ahmet Kuru in 2009 defined the secular state by two main characteristics, namely:

(1) the absence of institutional religious control of legislative and judicial processes, and

(2) constitutionally mandated neutrality towards religion, and non-establishment of an official religion or atheism.

The free exercise clause protects all citizens’ religious convictions and, to a lesser extent, religious practices. The establishment provision, which is more contentious, prohibits the government from excessively supporting, encouraging, or interfering with religion and religious activity.

While the Philippines’ “friendly” reputation benefits the country’s religious residents, it is also used against LGBTQIA+ people who are simply exercising their human rights. Students from the community are an example of this, as they are all too frequently subjected to bullying, discrimination, a lack of information about the LGBT community, and, in some cases, physical or sexual assault .

These wrongdoings have the potential to have a serious impact on students’ ability to pursue an education, which is guaranteed by both Philippine and international law. In recent years, policymakers and school officials in the Philippines have developed initiatives to address the major issue of bullying of LGBT adolescents.

In order to prevent harassment and discrimination in schools, especially on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, the Department of Education (DepEd), which is in responsible of overseeing primary and secondary schools, developed a Child Protection Policy in 2012.

Bullying and harassment based on sexual orientation and gender identity are prohibited under the Anti-Bullying Law of 2013, as well as the accompanying rules and regulations, which were passed by Congress in 2013.

By adopting these rules, educational institutions are making it quite apparent that they detest bullying and discrimination and do not support them. Although these policies appear to be sound on paper, they have not been effectively put into practice.

In the lack of appropriate implementation and supervision, many LGBT youth continue to experience bullying and harassment at school. The poor treatment that LGBT students experience from peers and teachers is made worse by the discriminatory practices that stigmatize and disenfranchise them as well as the lack of resources and information on LGBT problems in schools.

The occurrences detailed in this study highlight how crucial it is to strengthen and enforce protections for LGBTQIA+ adolescents in schools. These incidents could also be utilized to support the adoption of protective legislation for LGBTQIA+ people on a national level.

Legal Perspective

This discussion covers the bill’s components, its writers and their sources of inspiration, the measure’s advancement through the legislative process, common misconceptions about the bill, and its justification for being.

House Bill No. 4982 or “An Act Prohibiting Discrimination on the Basis of Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity or Expression (Sogie) and Providing Penalties Therefor” is the first of its kind in the country. Other anti-discrimination measures have been introduced in the past, but they never specifically addressed the SOGIE community, lumping the LGBTIA+ sector in with other groups like the disabled or indigenous people.

The first iteration of the SOGIE Equality Bill was introduced in the 11th Congress by the late Sen. Miriam Defensor-Santiago and Rep. Etta Rosales of the Akbayan.

Because of the arduous efforts of Representative Geraldine Roman from Bataan’s first congressional district, Representative Emmeline Aglipay-Villar from the Diwa Party List, and Representative Arlene “Kaka” Bag-ao from the Dinagat Islands, it is finally being fulfilled in the 17th Congress.

While the bill still needs to be approved by the Senate, its passage in the House is a significant victory for the LGBTQIA+ community. While the bill has already passed the lower house, it is still being debated in the Senate.

Senators Tito Sotto III, Manny Pacquiao, and Joel Villanueva, all of whom have been vocal about their religious beliefs, are among those who are vehemently opposed to its passage.

Several Christian organizations have also expressed their displeasure. According to the Christian Coalition for Righteousness, Justice, and Truth (CCRJT), the bill actually perpetuates rather than prevents discrimination because it discriminates against those who do not agree with the LGBTQIA+ community.

Proponents of the bill, on the other hand, vow to keep fighting for its passage into law. Senator Risa Hontiveros-Baraquel, Chairperson of the Senate Committee on Women, Children, Family Relations, and Gender Equality, emphasizes the importance of enacting legislation to protect people from sexual and gender-based discrimination and inequality, and laments the lack of such legislation.

The legislation starts by defining and introducing the concepts of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression. It also includes a glossary of terminology related to the previously mentioned themes.

Following that, it lists the acts that would be considered discriminatory and unlawful by the law, such as depriving members of the LGBTQIA+ community of rights based on their SOGIE, such as the right to access public services, use businesses and services, including housing, and apply for a professional license, among others.

Discrimination against an employee or anyone hired to provide services, refusal or revocation of accreditation to any organization due to an individual’s SOGIE, and denial of admission to or expulsion from an educational institution will all be punished.

Furthermore, the bill defines discrimination as the publication of information intended to “out” a person without that person’s consent, public speech designed to denigrate LGBTQ+ people, harassment and coercion of the latter by anyone, particularly those involved in law enforcement, and gender profiling.