- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Background of The Study

Definition:

Background of the study refers to the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being studied. It provides the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and the significance of the study.

The background of the study usually includes a discussion of the relevant literature, the gap in knowledge or understanding, and the research questions or hypotheses to be addressed. It also highlights the importance of the research topic and its potential contributions to the field. A well-written background of the study sets the stage for the research and helps the reader to appreciate the need for the study and its potential significance.

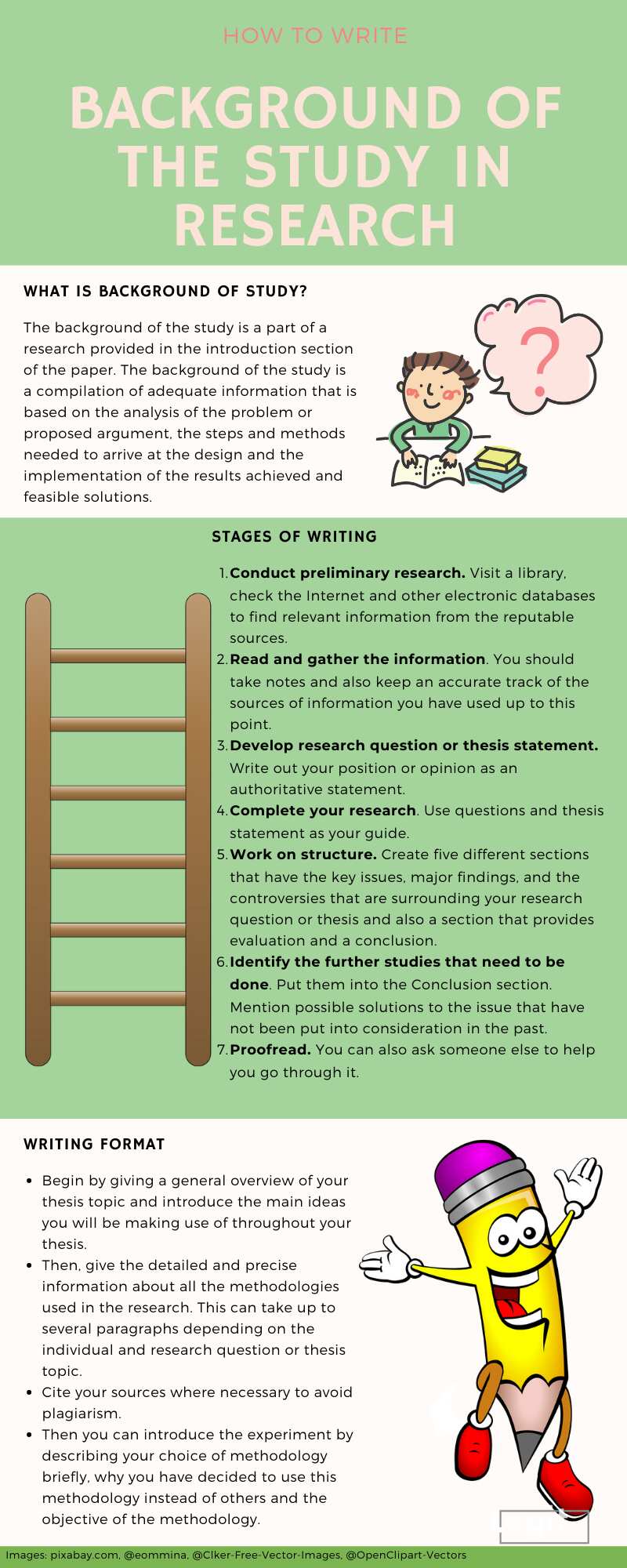

How to Write Background of The Study

Here are some steps to help you write the background of the study:

Identify the Research Problem

Start by identifying the research problem you are trying to address. This problem should be significant and relevant to your field of study.

Provide Context

Once you have identified the research problem, provide some context. This could include the historical, social, or political context of the problem.

Review Literature

Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature on the topic. This will help you understand what has been studied and what gaps exist in the current research.

Identify Research Gap

Based on your literature review, identify the gap in knowledge or understanding that your research aims to address. This gap will be the focus of your research question or hypothesis.

State Objectives

Clearly state the objectives of your research . These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Discuss Significance

Explain the significance of your research. This could include its potential impact on theory , practice, policy, or society.

Finally, summarize the key points of the background of the study. This will help the reader understand the research problem, its context, and its significance.

How to Write Background of The Study in Proposal

The background of the study is an essential part of any proposal as it sets the stage for the research project and provides the context and justification for why the research is needed. Here are the steps to write a compelling background of the study in your proposal:

- Identify the problem: Clearly state the research problem or gap in the current knowledge that you intend to address through your research.

- Provide context: Provide a brief overview of the research area and highlight its significance in the field.

- Review literature: Summarize the relevant literature related to the research problem and provide a critical evaluation of the current state of knowledge.

- Identify gaps : Identify the gaps or limitations in the existing literature and explain how your research will contribute to filling these gaps.

- Justify the study : Explain why your research is important and what practical or theoretical contributions it can make to the field.

- Highlight objectives: Clearly state the objectives of the study and how they relate to the research problem.

- Discuss methodology: Provide an overview of the methodology you will use to collect and analyze data, and explain why it is appropriate for the research problem.

- Conclude : Summarize the key points of the background of the study and explain how they support your research proposal.

How to Write Background of The Study In Thesis

The background of the study is a critical component of a thesis as it provides context for the research problem, rationale for conducting the study, and the significance of the research. Here are some steps to help you write a strong background of the study:

- Identify the research problem : Start by identifying the research problem that your thesis is addressing. What is the issue that you are trying to solve or explore? Be specific and concise in your problem statement.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the relevant literature on the topic. This should include scholarly articles, books, and other sources that are directly related to your research question.

- I dentify gaps in the literature: After reviewing the literature, identify any gaps in the existing research. What questions remain unanswered? What areas have not been explored? This will help you to establish the need for your research.

- Establish the significance of the research: Clearly state the significance of your research. Why is it important to address this research problem? What are the potential implications of your research? How will it contribute to the field?

- Provide an overview of the research design: Provide an overview of the research design and methodology that you will be using in your study. This should include a brief explanation of the research approach, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- State the research objectives and research questions: Clearly state the research objectives and research questions that your study aims to answer. These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

- Summarize the chapter: Summarize the chapter by highlighting the key points and linking them back to the research problem, significance of the study, and research questions.

How to Write Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are the steps to write the background of the study in a research paper:

- Identify the research problem: Start by identifying the research problem that your study aims to address. This can be a particular issue, a gap in the literature, or a need for further investigation.

- Conduct a literature review: Conduct a thorough literature review to gather information on the topic, identify existing studies, and understand the current state of research. This will help you identify the gap in the literature that your study aims to fill.

- Explain the significance of the study: Explain why your study is important and why it is necessary. This can include the potential impact on the field, the importance to society, or the need to address a particular issue.

- Provide context: Provide context for the research problem by discussing the broader social, economic, or political context that the study is situated in. This can help the reader understand the relevance of the study and its potential implications.

- State the research questions and objectives: State the research questions and objectives that your study aims to address. This will help the reader understand the scope of the study and its purpose.

- Summarize the methodology : Briefly summarize the methodology you used to conduct the study, including the data collection and analysis methods. This can help the reader understand how the study was conducted and its reliability.

Examples of Background of The Study

Here are some examples of the background of the study:

Problem : The prevalence of obesity among children in the United States has reached alarming levels, with nearly one in five children classified as obese.

Significance : Obesity in childhood is associated with numerous negative health outcomes, including increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers.

Gap in knowledge : Despite efforts to address the obesity epidemic, rates continue to rise. There is a need for effective interventions that target the unique needs of children and their families.

Problem : The use of antibiotics in agriculture has contributed to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which poses a significant threat to human health.

Significance : Antibiotic-resistant infections are responsible for thousands of deaths each year and are a major public health concern.

Gap in knowledge: While there is a growing body of research on the use of antibiotics in agriculture, there is still much to be learned about the mechanisms of resistance and the most effective strategies for reducing antibiotic use.

Edxample 3:

Problem : Many low-income communities lack access to healthy food options, leading to high rates of food insecurity and diet-related diseases.

Significance : Poor nutrition is a major contributor to chronic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Gap in knowledge : While there have been efforts to address food insecurity, there is a need for more research on the barriers to accessing healthy food in low-income communities and effective strategies for increasing access.

Examples of Background of The Study In Research

Here are some real-life examples of how the background of the study can be written in different fields of study:

Example 1 : “There has been a significant increase in the incidence of diabetes in recent years. This has led to an increased demand for effective diabetes management strategies. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of a new diabetes management program in improving patient outcomes.”

Example 2 : “The use of social media has become increasingly prevalent in modern society. Despite its popularity, little is known about the effects of social media use on mental health. This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health in young adults.”

Example 3: “Despite significant advancements in cancer treatment, the survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer remains low. The purpose of this study is to identify potential biomarkers that can be used to improve early detection and treatment of pancreatic cancer.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Proposal

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in a proposal:

Example 1 : The prevalence of mental health issues among university students has been increasing over the past decade. This study aims to investigate the causes and impacts of mental health issues on academic performance and wellbeing.

Example 2 : Climate change is a global issue that has significant implications for agriculture in developing countries. This study aims to examine the adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers to climate change and identify effective strategies to enhance their resilience.

Example 3 : The use of social media in political campaigns has become increasingly common in recent years. This study aims to analyze the effectiveness of social media campaigns in mobilizing young voters and influencing their voting behavior.

Example 4 : Employee turnover is a major challenge for organizations, especially in the service sector. This study aims to identify the key factors that influence employee turnover in the hospitality industry and explore effective strategies for reducing turnover rates.

Examples of Background of The Study in Thesis

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in the thesis:

Example 1 : “Women’s participation in the workforce has increased significantly over the past few decades. However, women continue to be underrepresented in leadership positions, particularly in male-dominated industries such as technology. This study aims to examine the factors that contribute to the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles in the technology industry, with a focus on organizational culture and gender bias.”

Example 2 : “Mental health is a critical component of overall health and well-being. Despite increased awareness of the importance of mental health, there are still significant gaps in access to mental health services, particularly in low-income and rural communities. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a community-based mental health intervention in improving mental health outcomes in underserved populations.”

Example 3: “The use of technology in education has become increasingly widespread, with many schools adopting online learning platforms and digital resources. However, there is limited research on the impact of technology on student learning outcomes and engagement. This study aims to explore the relationship between technology use and academic achievement among middle school students, as well as the factors that mediate this relationship.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are some examples of how the background of the study can be written in various fields:

Example 1: The prevalence of obesity has been on the rise globally, with the World Health Organization reporting that approximately 650 million adults were obese in 2016. Obesity is a major risk factor for several chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. In recent years, several interventions have been proposed to address this issue, including lifestyle changes, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery. However, there is a lack of consensus on the most effective intervention for obesity management. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of different interventions for obesity management and identify the most effective one.

Example 2: Antibiotic resistance has become a major public health threat worldwide. Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria are associated with longer hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and increased mortality. The inappropriate use of antibiotics is one of the main factors contributing to the development of antibiotic resistance. Despite numerous efforts to promote the rational use of antibiotics, studies have shown that many healthcare providers continue to prescribe antibiotics inappropriately. This study aims to explore the factors influencing healthcare providers’ prescribing behavior and identify strategies to improve antibiotic prescribing practices.

Example 3: Social media has become an integral part of modern communication, with millions of people worldwide using platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Social media has several advantages, including facilitating communication, connecting people, and disseminating information. However, social media use has also been associated with several negative outcomes, including cyberbullying, addiction, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on mental health and identify the factors that mediate this relationship.

Purpose of Background of The Study

The primary purpose of the background of the study is to help the reader understand the rationale for the research by presenting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem.

More specifically, the background of the study aims to:

- Provide a clear understanding of the research problem and its context.

- Identify the gap in knowledge that the study intends to fill.

- Establish the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field.

- Highlight the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

- Provide a rationale for the research questions or hypotheses and the research design.

- Identify the limitations and scope of the study.

When to Write Background of The Study

The background of the study should be written early on in the research process, ideally before the research design is finalized and data collection begins. This allows the researcher to clearly articulate the rationale for the study and establish a strong foundation for the research.

The background of the study typically comes after the introduction but before the literature review section. It should provide an overview of the research problem and its context, and also introduce the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

Writing the background of the study early on in the research process also helps to identify potential gaps in knowledge and areas for further investigation, which can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design. By establishing the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field, the background of the study can also help to justify the research and secure funding or support from stakeholders.

Advantage of Background of The Study

The background of the study has several advantages, including:

- Provides context: The background of the study provides context for the research problem by highlighting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem. This allows the reader to understand the research problem in its broader context and appreciate its significance.

- Identifies gaps in knowledge: By reviewing the existing literature related to the research problem, the background of the study can identify gaps in knowledge that the study intends to fill. This helps to establish the novelty and originality of the research and its potential contribution to the field.

- Justifies the research : The background of the study helps to justify the research by demonstrating its significance and potential impact. This can be useful in securing funding or support for the research.

- Guides the research design: The background of the study can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design by identifying key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem. This ensures that the research is grounded in existing knowledge and is designed to address the research problem effectively.

- Establishes credibility: By demonstrating the researcher’s knowledge of the field and the research problem, the background of the study can establish the researcher’s credibility and expertise, which can enhance the trustworthiness and validity of the research.

Disadvantages of Background of The Study

Some Disadvantages of Background of The Study are as follows:

- Time-consuming : Writing a comprehensive background of the study can be time-consuming, especially if the research problem is complex and multifaceted. This can delay the research process and impact the timeline for completing the study.

- Repetitive: The background of the study can sometimes be repetitive, as it often involves summarizing existing research and theories related to the research problem. This can be tedious for the reader and may make the section less engaging.

- Limitations of existing research: The background of the study can reveal the limitations of existing research related to the problem. This can create challenges for the researcher in developing research questions or hypotheses that address the gaps in knowledge identified in the background of the study.

- Bias : The researcher’s biases and perspectives can influence the content and tone of the background of the study. This can impact the reader’s perception of the research problem and may influence the validity of the research.

- Accessibility: Accessing and reviewing the literature related to the research problem can be challenging, especially if the researcher does not have access to a comprehensive database or if the literature is not available in the researcher’s language. This can limit the depth and scope of the background of the study.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Effective Background of the Study: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

The background of the study in a research paper offers a clear context, highlighting why the research is essential and the problem it aims to address.

As a researcher, this foundational section is essential for you to chart the course of your study, Moreover, it allows readers to understand the importance and path of your research.

Whether in academic communities or to the general public, a well-articulated background aids in communicating the essence of the research effectively.

While it may seem straightforward, crafting an effective background requires a blend of clarity, precision, and relevance. Therefore, this article aims to be your guide, offering insights into:

- Understanding the concept of the background of the study.

- Learning how to craft a compelling background effectively.

- Identifying and sidestepping common pitfalls in writing the background.

- Exploring practical examples that bring the theory to life.

- Enhancing both your writing and reading of academic papers.

Keeping these compelling insights in mind, let's delve deeper into the details of the empirical background of the study, exploring its definition, distinctions, and the art of writing it effectively.

What is the background of the study?

The background of the study is placed at the beginning of a research paper. It provides the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being explored.

It offers readers a snapshot of the existing knowledge on the topic and the reasons that spurred your current research.

When crafting the background of your study, consider the following questions.

- What's the context of your research?

- Which previous research will you refer to?

- Are there any knowledge gaps in the existing relevant literature?

- How will you justify the need for your current research?

- Have you concisely presented the research question or problem?

In a typical research paper structure, after presenting the background, the introduction section follows. The introduction delves deeper into the specific objectives of the research and often outlines the structure or main points that the paper will cover.

Together, they create a cohesive starting point, ensuring readers are well-equipped to understand the subsequent sections of the research paper.

While the background of the study and the introduction section of the research manuscript may seem similar and sometimes even overlap, each serves a unique purpose in the research narrative.

Difference between background and introduction

A well-written background of the study and introduction are preliminary sections of a research paper and serve distinct purposes.

Here’s a detailed tabular comparison between the two of them.

What is the relevance of the background of the study?

It is necessary for you to provide your readers with the background of your research. Without this, readers may grapple with questions such as: Why was this specific research topic chosen? What led to this decision? Why is this study relevant? Is it worth their time?

Such uncertainties can deter them from fully engaging with your study, leading to the rejection of your research paper. Additionally, this can diminish its impact in the academic community, and reduce its potential for real-world application or policy influence .

To address these concerns and offer clarity, the background section plays a pivotal role in research papers.

The background of the study in research is important as it:

- Provides context: It offers readers a clear picture of the existing knowledge, helping them understand where the current research fits in.

- Highlights relevance: By detailing the reasons for the research, it underscores the study's significance and its potential impact.

- Guides the narrative: The background shapes the narrative flow of the paper, ensuring a logical progression from what's known to what the research aims to uncover.

- Enhances engagement: A well-crafted background piques the reader's interest, encouraging them to delve deeper into the research paper.

- Aids in comprehension: By setting the scenario, it aids readers in better grasping the research objectives, methodologies, and findings.

How to write the background of the study in a research paper?

The journey of presenting a compelling argument begins with the background study. This section holds the power to either captivate or lose the reader's interest.

An effectively written background not only provides context but also sets the tone for the entire research paper. It's the bridge that connects a broad topic to a specific research question, guiding readers through the logic behind the study.

But how does one craft a background of the study that resonates, informs, and engages?

Here, we’ll discuss how to write an impactful background study, ensuring your research stands out and captures the attention it deserves.

Identify the research problem

The first step is to start pinpointing the specific issue or gap you're addressing. This should be a significant and relevant problem in your field.

A well-defined problem is specific, relevant, and significant to your field. It should resonate with both experts and readers.

Here’s more on how to write an effective research problem .

Provide context

Here, you need to provide a broader perspective, illustrating how your research aligns with or contributes to the overarching context or the wider field of study. A comprehensive context is grounded in facts, offers multiple perspectives, and is relatable.

In addition to stating facts, you should weave a story that connects key concepts from the past, present, and potential future research. For instance, consider the following approach.

- Offer a brief history of the topic, highlighting major milestones or turning points that have shaped the current landscape.

- Discuss contemporary developments or current trends that provide relevant information to your research problem. This could include technological advancements, policy changes, or shifts in societal attitudes.

- Highlight the views of different stakeholders. For a topic like sustainable agriculture, this could mean discussing the perspectives of farmers, environmentalists, policymakers, and consumers.

- If relevant, compare and contrast global trends with local conditions and circumstances. This can offer readers a more holistic understanding of the topic.

Literature review

For this step, you’ll deep dive into the existing literature on the same topic. It's where you explore what scholars, researchers, and experts have already discovered or discussed about your topic.

Conducting a thorough literature review isn't just a recap of past works. To elevate its efficacy, it's essential to analyze the methods, outcomes, and intricacies of prior research work, demonstrating a thorough engagement with the existing body of knowledge.

- Instead of merely listing past research study, delve into their methodologies, findings, and limitations. Highlight groundbreaking studies and those that had contrasting results.

- Try to identify patterns. Look for recurring themes or trends in the literature. Are there common conclusions or contentious points?

- The next step would be to connect the dots. Show how different pieces of research relate to each other. This can help in understanding the evolution of thought on the topic.

By showcasing what's already known, you can better highlight the background of the study in research.

Highlight the research gap

This step involves identifying the unexplored areas or unanswered questions in the existing literature. Your research seeks to address these gaps, providing new insights or answers.

A clear research gap shows you've thoroughly engaged with existing literature and found an area that needs further exploration.

How can you efficiently highlight the research gap?

- Find the overlooked areas. Point out topics or angles that haven't been adequately addressed.

- Highlight questions that have emerged due to recent developments or changing circumstances.

- Identify areas where insights from other fields might be beneficial but haven't been explored yet.

State your objectives

Here, it’s all about laying out your game plan — What do you hope to achieve with your research? You need to mention a clear objective that’s specific, actionable, and directly tied to the research gap.

How to state your objectives?

- List the primary questions guiding your research.

- If applicable, state any hypotheses or predictions you aim to test.

- Specify what you hope to achieve, whether it's new insights, solutions, or methodologies.

Discuss the significance

This step describes your 'why'. Why is your research important? What broader implications does it have?

The significance of “why” should be both theoretical (adding to the existing literature) and practical (having real-world implications).

How do we effectively discuss the significance?

- Discuss how your research adds to the existing body of knowledge.

- Highlight how your findings could be applied in real-world scenarios, from policy changes to on-ground practices.

- Point out how your research could pave the way for further studies or open up new areas of exploration.

Summarize your points

A concise summary acts as a bridge, smoothly transitioning readers from the background to the main body of the paper. This step is a brief recap, ensuring that readers have grasped the foundational concepts.

How to summarize your study?

- Revisit the key points discussed, from the research problem to its significance.

- Prepare the reader for the subsequent sections, ensuring they understand the research's direction.

Include examples for better understanding

Research and come up with real-world or hypothetical examples to clarify complex concepts or to illustrate the practical applications of your research. Relevant examples make abstract ideas tangible, aiding comprehension.

How to include an effective example of the background of the study?

- Use past events or scenarios to explain concepts.

- Craft potential scenarios to demonstrate the implications of your findings.

- Use comparisons to simplify complex ideas, making them more relatable.

Crafting a compelling background of the study in research is about striking the right balance between providing essential context, showcasing your comprehensive understanding of the existing literature, and highlighting the unique value of your research .

While writing the background of the study, keep your readers at the forefront of your mind. Every piece of information, every example, and every objective should be geared toward helping them understand and appreciate your research.

How to avoid mistakes in the background of the study in research?

To write a well-crafted background of the study, you should be aware of the following potential research pitfalls .

- Stay away from ambiguity. Always assume that your reader might not be familiar with intricate details about your topic.

- Avoid discussing unrelated themes. Stick to what's directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure your background is well-organized. Information should flow logically, making it easy for readers to follow.

- While it's vital to provide context, avoid overwhelming the reader with excessive details that might not be directly relevant to your research problem.

- Ensure you've covered the most significant and relevant studies i` n your field. Overlooking key pieces of literature can make your background seem incomplete.

- Aim for a balanced presentation of facts, and avoid showing overt bias or presenting only one side of an argument.

- While academic paper often involves specialized terms, ensure they're adequately explained or use simpler alternatives when possible.

- Every claim or piece of information taken from existing literature should be appropriately cited. Failing to do so can lead to issues of plagiarism.

- Avoid making the background too lengthy. While thoroughness is appreciated, it should not come at the expense of losing the reader's interest. Maybe prefer to keep it to one-two paragraphs long.

- Especially in rapidly evolving fields, it's crucial to ensure that your literature review section is up-to-date and includes the latest research.

Example of an effective background of the study

Let's consider a topic: "The Impact of Online Learning on Student Performance." The ideal background of the study section for this topic would be as follows.

In the last decade, the rise of the internet has revolutionized many sectors, including education. Online learning platforms, once a supplementary educational tool, have now become a primary mode of instruction for many institutions worldwide. With the recent global events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rapid shift from traditional classroom learning to online modes, making it imperative to understand its effects on student performance.

Previous studies have explored various facets of online learning, from its accessibility to its flexibility. However, there is a growing need to assess its direct impact on student outcomes. While some educators advocate for its benefits, citing the convenience and vast resources available, others express concerns about potential drawbacks, such as reduced student engagement and the challenges of self-discipline.

This research aims to delve deeper into this debate, evaluating the true impact of online learning on student performance.

Why is this example considered as an effective background section of a research paper?

This background section example effectively sets the context by highlighting the rise of online learning and its increased relevance due to recent global events. It references prior research on the topic, indicating a foundation built on existing knowledge.

By presenting both the potential advantages and concerns of online learning, it establishes a balanced view, leading to the clear purpose of the study: to evaluate the true impact of online learning on student performance.

As we've explored, writing an effective background of the study in research requires clarity, precision, and a keen understanding of both the broader landscape and the specific details of your topic.

From identifying the research problem, providing context, reviewing existing literature to highlighting research gaps and stating objectives, each step is pivotal in shaping the narrative of your research. And while there are best practices to follow, it's equally crucial to be aware of the pitfalls to avoid.

Remember, writing or refining the background of your study is essential to engage your readers, familiarize them with the research context, and set the ground for the insights your research project will unveil.

Drawing from all the important details, insights and guidance shared, you're now in a strong position to craft a background of the study that not only informs but also engages and resonates with your readers.

Now that you've a clear understanding of what the background of the study aims to achieve, the natural progression is to delve into the next crucial component — write an effective introduction section of a research paper. Read here .

Frequently Asked Questions

The background of the study should include a clear context for the research, references to relevant previous studies, identification of knowledge gaps, justification for the current research, a concise overview of the research problem or question, and an indication of the study's significance or potential impact.

The background of the study is written to provide readers with a clear understanding of the context, significance, and rationale behind the research. It offers a snapshot of existing knowledge on the topic, highlights the relevance of the study, and sets the stage for the research questions and objectives. It ensures that readers can grasp the importance of the research and its place within the broader field of study.

The background of the study is a section in a research paper that provides context, circumstances, and history leading to the research problem or topic being explored. It presents existing knowledge on the topic and outlines the reasons that spurred the current research, helping readers understand the research's foundation and its significance in the broader academic landscape.

The number of paragraphs in the background of the study can vary based on the complexity of the topic and the depth of the context required. Typically, it might range from 3 to 5 paragraphs, but in more detailed or complex research papers, it could be longer. The key is to ensure that all relevant information is presented clearly and concisely, without unnecessary repetition.

You might also like

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Beyond Google Scholar: Why SciSpace is the best alternative

Types of Literature Review — A Guide for Researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

What is the Background of a Study and How Should it be Written?

- 3 minute read

- 835.1K views

Table of Contents

The background of a study is one of the most important components of a research paper. The quality of the background determines whether the reader will be interested in the rest of the study. Thus, to ensure that the audience is invested in reading the entire research paper, it is important to write an appealing and effective background. So, what constitutes the background of a study, and how must it be written?

What is the background of a study?

The background of a study is the first section of the paper and establishes the context underlying the research. It contains the rationale, the key problem statement, and a brief overview of research questions that are addressed in the rest of the paper. The background forms the crux of the study because it introduces an unaware audience to the research and its importance in a clear and logical manner. At times, the background may even explore whether the study builds on or refutes findings from previous studies. Any relevant information that the readers need to know before delving into the paper should be made available to them in the background.

How is a background different from the introduction?

The introduction of your research paper is presented before the background. Let’s find out what factors differentiate the background from the introduction.

- The introduction only contains preliminary data about the research topic and does not state the purpose of the study. On the contrary, the background clarifies the importance of the study in detail.

- The introduction provides an overview of the research topic from a broader perspective, while the background provides a detailed understanding of the topic.

- The introduction should end with the mention of the research questions, aims, and objectives of the study. In contrast, the background follows no such format and only provides essential context to the study.

How should one write the background of a research paper?

The length and detail presented in the background varies for different research papers, depending on the complexity and novelty of the research topic. At times, a simple background suffices, even if the study is complex. Before writing and adding details in the background, take a note of these additional points:

- Start with a strong beginning: Begin the background by defining the research topic and then identify the target audience.

- Cover key components: Explain all theories, concepts, terms, and ideas that may feel unfamiliar to the target audience thoroughly.

- Take note of important prerequisites: Go through the relevant literature in detail. Take notes while reading and cite the sources.

- Maintain a balance: Make sure that the background is focused on important details, but also appeals to a broader audience.

- Include historical data: Current issues largely originate from historical events or findings. If the research borrows information from a historical context, add relevant data in the background.

- Explain novelty: If the research study or methodology is unique or novel, provide an explanation that helps to understand the research better.

- Increase engagement: To make the background engaging, build a story around the central theme of the research

Avoid these mistakes while writing the background:

- Ambiguity: Don’t be ambiguous. While writing, assume that the reader does not understand any intricate detail about your research.

- Unrelated themes: Steer clear from topics that are not related to the key aspects of your research topic.

- Poor organization: Do not place information without a structure. Make sure that the background reads in a chronological manner and organize the sub-sections so that it flows well.

Writing the background for a research paper should not be a daunting task. But directions to go about it can always help. At Elsevier Author Services we provide essential insights on how to write a high quality, appealing, and logically structured paper for publication, beginning with a robust background. For further queries, contact our experts now!

How to Use Tables and Figures effectively in Research Papers

- Research Process

The Top 5 Qualities of Every Good Researcher

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

What Is Background in a Research Paper?

So you have carefully written your research paper and probably ran it through your colleagues ten to fifteen times. While there are many elements to a good research article, one of the most important elements for your readers is the background of your study.

What is Background of the Study in Research

The background of your study will provide context to the information discussed throughout the research paper . Background information may include both important and relevant studies. This is particularly important if a study either supports or refutes your thesis.

Why is Background of the Study Necessary in Research?

The background of the study discusses your problem statement, rationale, and research questions. It links introduction to your research topic and ensures a logical flow of ideas. Thus, it helps readers understand your reasons for conducting the study.

Providing Background Information

The reader should be able to understand your topic and its importance. The length and detail of your background also depend on the degree to which you need to demonstrate your understanding of the topic. Paying close attention to the following questions will help you in writing background information:

- Are there any theories, concepts, terms, and ideas that may be unfamiliar to the target audience and will require you to provide any additional explanation?

- Any historical data that need to be shared in order to provide context on why the current issue emerged?

- Are there any concepts that may have been borrowed from other disciplines that may be unfamiliar to the reader and need an explanation?

Related: Ready with the background and searching for more information on journal ranking? Check this infographic on the SCImago Journal Rank today!

Is the research study unique for which additional explanation is needed? For instance, you may have used a completely new method

How to Write a Background of the Study

The structure of a background study in a research paper generally follows a logical sequence to provide context, justification, and an understanding of the research problem. It includes an introduction, general background, literature review , rationale , objectives, scope and limitations , significance of the study and the research hypothesis . Following the structure can provide a comprehensive and well-organized background for your research.

Here are the steps to effectively write a background of the study.

1. Identify Your Audience:

Determine the level of expertise of your target audience. Tailor the depth and complexity of your background information accordingly.

2. Understand the Research Problem:

Define the research problem or question your study aims to address. Identify the significance of the problem within the broader context of the field.

3. Review Existing Literature:

Conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known in the area. Summarize key findings, theories, and concepts relevant to your research.

4. Include Historical Data:

Integrate historical data if relevant to the research, as current issues often trace back to historical events.

5. Identify Controversies and Gaps:

Note any controversies or debates within the existing literature. Identify gaps , limitations, or unanswered questions that your research can address.

6. Select Key Components:

Choose the most critical elements to include in the background based on their relevance to your research problem. Prioritize information that helps build a strong foundation for your study.

7. Craft a Logical Flow:

Organize the background information in a logical sequence. Start with general context, move to specific theories and concepts, and then focus on the specific problem.

8. Highlight the Novelty of Your Research:

Clearly explain the unique aspects or contributions of your study. Emphasize why your research is different from or builds upon existing work.

Here are some extra tips to increase the quality of your research background:

Example of a Research Background

Here is an example of a research background to help you understand better.

The above hypothetical example provides a research background, addresses the gap and highlights the potential outcome of the study; thereby aiding a better understanding of the proposed research.

What Makes the Introduction Different from the Background?

Your introduction is different from your background in a number of ways.

- The introduction contains preliminary data about your topic that the reader will most likely read , whereas the background clarifies the importance of the paper.

- The background of your study discusses in depth about the topic, whereas the introduction only gives an overview.

- The introduction should end with your research questions, aims, and objectives, whereas your background should not (except in some cases where your background is integrated into your introduction). For instance, the C.A.R.S. ( Creating a Research Space ) model, created by John Swales is based on his analysis of journal articles. This model attempts to explain and describe the organizational pattern of writing the introduction in social sciences.

Points to Note

Your background should begin with defining a topic and audience. It is important that you identify which topic you need to review and what your audience already knows about the topic. You should proceed by searching and researching the relevant literature. In this case, it is advisable to keep track of the search terms you used and the articles that you downloaded. It is helpful to use one of the research paper management systems such as Papers, Mendeley, Evernote, or Sente. Next, it is helpful to take notes while reading. Be careful when copying quotes verbatim and make sure to put them in quotation marks and cite the sources. In addition, you should keep your background focused but balanced enough so that it is relevant to a broader audience. Aside from these, your background should be critical, consistent, and logically structured.

Writing the background of your study should not be an overly daunting task. Many guides that can help you organize your thoughts as you write the background. The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to your research topic and should be done with strong knowledge and thoughtful writing.

The background of a research paper typically ranges from one to two paragraphs, summarizing the relevant literature and context of the study. It should be concise, providing enough information to contextualize the research problem and justify the need for the study. Journal instructions about any word count limits should be kept in mind while deciding on the length of the final content.

The background of a research paper provides the context and relevant literature to understand the research problem, while the introduction also introduces the specific research topic, states the research objectives, and outlines the scope of the study. The background focuses on the broader context, whereas the introduction focuses on the specific research project and its objectives.

When writing the background for a study, start by providing a brief overview of the research topic and its significance in the field. Then, highlight the gaps in existing knowledge or unresolved issues that the study aims to address. Finally, summarize the key findings from relevant literature to establish the context and rationale for conducting the research, emphasizing the need and importance of the study within the broader academic landscape.

The background in a research paper is crucial as it sets the stage for the study by providing essential context and rationale. It helps readers understand the significance of the research problem and its relevance in the broader field. By presenting relevant literature and highlighting gaps, the background justifies the need for the study, building a strong foundation for the research and enhancing its credibility.

The presentation very informative

It is really educative. I love the workshop. It really motivated me into writing my first paper for publication.

an interesting clue here, thanks.

thanks for the answers.

Good and interesting explanation. Thanks

Thank you for good presentation.

Hi Adam, we are glad to know that you found our article beneficial

The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to YOUR research topic.

Awesome. Exactly what i was looking forwards to 😉

Hi Maryam, we are glad to know that you found our resource useful.

my understanding of ‘Background of study’ has been elevated.

Hi Peter, we are glad to know that our article has helped you get a better understanding of the background in a research paper.

thanks to give advanced information

Hi Shimelis, we are glad to know that you found the information in our article beneficial.

When i was studying it is very much hard for me to conduct a research study and know the background because my teacher in practical research is having a research so i make it now so that i will done my research

Very informative……….Thank you.

The confusion i had before, regarding an introduction and background to a research work is now a thing of the past. Thank you so much.

Thanks for your help…

Thanks for your kind information about the background of a research paper.

Thanks for the answer

Very informative. I liked even more when the difference between background and introduction was given. I am looking forward to learning more from this site. I am in Botswana

Hello, I am Benoît from Central African Republic. Right now I am writing down my research paper in order to get my master degree in British Literature. Thank you very much for posting all this information about the background of the study. I really appreciate. Thanks!

The write up is quite good, detailed and informative. Thanks a lot. The article has certainly enhanced my understanding of the topic.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

- Editing Services

- Academic Editing Services

- Admissions Editing Services

- Admissions Essay Editing Services

- AI Content Editing Services

- APA Style Editing Services

- Application Essay Editing Services

- Book Editing Services

- Business Editing Services

- Capstone Paper Editing Services

- Children's Book Editing Services

- College Application Editing Services

- College Essay Editing Services

- Copy Editing Services

- Developmental Editing Services

- Dissertation Editing Services

- eBook Editing Services

- English Editing Services

- Horror Story Editing Services

- Legal Editing Services

- Line Editing Services

- Manuscript Editing Services

- MLA Style Editing Services

- Novel Editing Services

- Paper Editing Services

- Personal Statement Editing Services

- Research Paper Editing Services

- Résumé Editing Services

- Scientific Editing Services

- Short Story Editing Services

- Statement of Purpose Editing Services

- Substantive Editing Services

- Thesis Editing Services

Proofreading

- Proofreading Services

- Admissions Essay Proofreading Services

- Children's Book Proofreading Services

- Legal Proofreading Services

- Novel Proofreading Services

- Personal Statement Proofreading Services

- Research Proposal Proofreading Services

- Statement of Purpose Proofreading Services

Translation

- Translation Services

Graphic Design

- Graphic Design Services

- Dungeons & Dragons Design Services

- Sticker Design Services

- Writing Services

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Tips for Writing an Effective Background of the Study

The Background of the Study is an integral part of any research paper that sets the context and the stage for the research presented in the paper. It's the section that provides a detailed context of the study by explaining the problem under investigation, the gaps in existing research that the study aims to fill, and the relevance of the study to the research field. It often incorporates aspects of the existing literature and gives readers an understanding of why the research is necessary and the theoretical framework that it is grounded in.

The Background of the Study holds a significant position in the process of research. It serves as the scaffold upon which the entire research project is built. It helps the reader understand the problem, its significance, and how your research will contribute to the existing body of knowledge. A well-articulated background can provide a clear roadmap for your study and assist others in understanding the direction and value of your research. Without it, readers may struggle to grasp the purpose and importance of your work.

The aim of this blog post is to guide budding researchers, students, and academicians on how to craft an effective Background of the Study section for their research paper. It is designed to provide practical tips, highlight key components, and elucidate common mistakes to avoid. By the end of this blog post, readers should have a clear understanding of how to construct a compelling background that successfully contextualizes their research, highlights its significance, and sets a clear path for their investigation.

Understanding the background of the study

The Background of the Study in a research context refers to a section of your research paper that discloses the basis and reasons behind the conduction of the study. It sets the broader context for your research by presenting the problem that your study intends to address, giving a brief overview of the subject domain, and highlighting the existing gaps in knowledge. This section also presents the theoretical or conceptual framework and states the research objectives, and often includes the research question or hypothesis . The Background of the Study gives your readers a deeper understanding of the purpose, importance, and direction of your study.

How it fits into the overall structure of a research paper

The Background of the Study typically appears after the introduction and before the literature review in the overall structure of a research paper. It acts as a bridge between the general introduction, where the topic is initially presented, and the more specific aspects of the paper such as the literature review, methodology , results , and discussion. It provides necessary information to help readers understand the relevance and value of the study in a wider context, before zooming in to specific details of your research.

Difference between the background of the study, introduction, and literature review

Now that we understand the role of the Background of the Study within a research paper, let's delve deeper to differentiate it from two other crucial components of the paper - the Introduction and the Literature Review.

- Background of the Study: This section provides a comprehensive context for the research, including a statement of the problem , the theoretical or conceptual framework, the gap that the study intends to fill, and the overall significance of the research. It guides the reader from a broad understanding of the research context to the specifics of your study.

- Introduction: This is the first section of the research paper that provides a broad overview of the topic , introduces the research question or hypothesis , and briefly mentions the methodology used in the study. It piques the reader's interest and gives them a reason to continue reading the paper.

- Literature Review: This section presents an organized summary of the existing research related to your study. It helps identify what we already know and what we do not know about the topic, thereby establishing the necessity for your research. The literature review allows you to demonstrate how your study contributes to and extends the existing body of knowledge.

While these three sections may overlap in some aspects, each serves a unique purpose and plays a critical role in the research paper.

Components of the background of the study

Statement of the problem.

This is the issue or situation that your research is intended to address. It should be a clear, concise declaration that explains the problem in detail, its context, and the negative impacts if it remains unresolved. This statement also explains why there's a need to study the problem, making it crucial for defining the research objectives.

Importance of the study

In this component, you outline the reasons why your research is significant. How does it contribute to the existing body of knowledge? Does it provide insights into a particular issue, offer solutions to a problem, or fill gaps in existing research? Clarifying the importance of your study helps affirm its value to your field and the larger academic community.

Relevant previous research and literature

Present an overview of the major studies and research conducted on the topic. This not only shows that you have a broad understanding of your field, but it also allows you to highlight the knowledge gaps that your study aims to fill. It also helps establish the context of your study within the larger academic dialogue.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. It presents the theories, concepts, or ideas which are relevant to the study and explains how these theories apply to your research. It helps to connect your findings to the broader constructs and theories in your field.

Research questions or hypotheses

These are the specific queries your research aims to answer or the predictions you are testing. They should be directly aligned with your problem statement and clearly set out what you hope to discover through your research.

Potential implications of the research

This involves outlining the potential applications of your research findings in your field and possibly beyond. What changes could your research inspire? How might it influence future studies? By explaining this, you underscore the potential impact of your research and its significance in a broader context.

How to write a comprehensive background of the study

Identify and articulate the problem statement.

To successfully identify and articulate your problem statement, consider the following steps:

- Start by clearly defining the problem your research aims to solve. The problem should be specific and researchable.

- Provide context for the problem. Where does it arise? Who or what is affected by it?

- Clearly articulate why the problem is significant. Is it a new issue, or has it been a long-standing problem in your field? How does it impact the broader field or society at large?

- Express the potential adverse effects if the problem remains unresolved. This can help underscore the urgency or importance of your research.

- Remember, while your problem statement should be comprehensive, aim for conciseness. You want to communicate the gravity of the issue in a precise and clear manner.

Conduct and summarize relevant literature review

A well-executed literature review is fundamental for situating your study within the broader context of existing research. Here's how you can approach it:

- Begin by conducting a comprehensive search for existing research that is relevant to your problem statement. Make use of academic databases, scholarly journals, and other credible sources of research.

- As you read these studies, pay close attention to their key findings, research methodologies, and any gaps in the research that they've identified. These elements will be crucial in the summary of your literature review.

- Make an effort to analyze, rather than just list, the studies. This means drawing connections between different research findings, contrasting methodologies, and identifying overarching trends or conflicts in the field.

- When summarizing the literature review, focus on synthesis . Explain how these studies relate to each other and how they collectively relate to your own research. This could mean identifying patterns, themes, or gaps that your research aims to address.

Describe the theoretical framework

The theoretical framework of your research is crucial as it grounds your work in established concepts and provides a lens through which your results can be interpreted. Here's how to effectively describe it:

- Begin by identifying the theories, ideas, or models upon which your research is based. These may come from your literature review or your understanding of the subject matter.

- Explain these theories or concepts in simple terms, bearing in mind that your reader may not be familiar with them. Be sure to define any technical terms or jargon that you use.

- Make connections between these theories and your research. How do they relate to your study? Do they inform your research questions or hypotheses?

- Show how these theories guide your research methodology and your analysis. For instance, do they suggest certain methods for data collection or specific ways of interpreting your data?

- Remember, your theoretical framework should act as the "lens" through which your results are viewed, so it needs to be relevant and applicable to your study.

Formulate your research questions or hypotheses

Crafting well-defined research questions or hypotheses is a crucial step in outlining the scope of your research. Here's how you can effectively approach this process:

- Begin by establishing the specific questions your research aims to answer. If your study is more exploratory in nature, you may formulate research questions. If it is more explanatory or confirmatory, you may state hypotheses.

- Ensure that your questions or hypotheses are researchable. They should be specific, clear, and measurable with the methods you plan to use.

- Check that your research questions or hypotheses align with your problem statement and research objectives. They should be a natural extension of the issues outlined in your background of the study.

- Finally, remember that well-crafted research questions or hypotheses will guide your research design and help structure your entire paper. They act as the anchors around which your research revolves.

Highlight the potential implications and significance of your research

To conclude your Background of the Study, it's essential to highlight the potential implications and significance of your work. Here's how to do it effectively:

- Start by providing a clear explanation of your research's potential implications. This could relate to the advancement of theoretical knowledge or practical applications in the real world.

- Discuss the importance of your research within the context of your field. How does it contribute to the existing body of knowledge? Does it challenge current theories or practices?

- Highlight how your research could influence future studies. Could it open new avenues of inquiry? Does it suggest a need for further research in certain areas?

- Finally, consider the practical applications of your research. How could your findings be used in policy-making, business strategies, educational practices, or other real-world scenarios?

- Always keep in mind that demonstrating the broader impact of your research increases its relevance and appeal to a wider audience, extending beyond the immediate academic circle.

Following these guidelines can help you effectively highlight the potential implications and significance of your research, thereby strengthening the impact of your study.

Practical tips for writing the background of the study

Keeping the section concise and focused.

Maintain clarity and brevity in your writing. While you need to provide sufficient detail to set the stage for your research, avoid unnecessary verbosity. Stay focused on the main aspects related to your research problem, its context, and your study's contribution.

Ensuring the background aligns with your research questions or hypotheses

Ensure a clear connection between your background and your research questions or hypotheses. Your problem statement, review of relevant literature, theoretical framework, and the identified gap in research should logically lead to your research questions or hypotheses.

Citing your sources correctly

Always attribute the ideas, theories, and research findings of others appropriately to avoid plagiarism . Correct citation not only upholds academic integrity but also allows your readers to access your sources if they wish to explore them in depth. The citation style may depend on your field of study or the requirements of the journal or institution.

Bridging the gap between existing research and your study

Identify the gap in existing research that your study aims to fill and make it explicit. Show how your research questions or hypotheses emerged from this identified gap. This helps to position your research within the broader academic conversation and highlights the unique contribution of your study.

Avoiding excessive jargon

While technical terms are often unavoidable in academic writing, use them sparingly and make sure to define any necessary jargon for your reader. Your Background of the Study should be understandable to people outside your field as well. This will increase the accessibility and impact of your research.

Common mistakes to avoid while writing the background of the study

Being overly verbose or vague.

While it's important to provide sufficient context, avoid being overly verbose in your descriptions. Also, steer clear of vague or ambiguous phrases. The Background of the Study should be clear, concise, and specific, giving the reader a precise understanding of the study's purpose and context.

Failing to relate the background to the research problem

The entire purpose of the Background of the Study is to set the stage for your research problem. If it doesn't directly relate to your problem statement, research questions, or hypotheses, it may confuse the reader. Always ensure that every element of the background ties back to your study.

Neglecting to mention important related studies

Not mentioning significant related studies is another common mistake. The Background of the Study section should give a summary of the existing literature related to your research. Omitting key pieces of literature can give the impression that you haven't thoroughly researched the topic.

Overusing technical jargon without explanation

While certain technical terms may be necessary, overuse of jargon can make your paper inaccessible to readers outside your immediate field. If you need to use technical terms, make sure you define them clearly. Strive for clarity and simplicity in your writing as much as possible.

Not citing sources or citing them incorrectly

Academic integrity is paramount in research writing. Ensure that every idea, finding, or theory that is not your own is properly attributed to its original source. Neglecting to cite, or citing incorrectly, can lead to accusations of plagiarism and can discredit your research. Always follow the citation style guide relevant to your field.

Writing an effective Background of the Study is a critical step in crafting a compelling research paper. It serves to contextualize your research, highlight its significance, and present the problem your study seeks to address. Remember, your background should provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of research, identify gaps in existing literature, and indicate how your research will fill these gaps. Keep your writing concise, focused, and jargon-free, making sure to correctly cite all sources. Avoiding common mistakes and adhering to the strategies outlined in this post will help you develop a robust and engaging background for your study. As you embark on your research journey, remember that the Background of the Study sets the stage for your entire research project, so investing time and effort into crafting it effectively will undoubtedly pay dividends in the end.

Header image by Flamingo Images .

Related Posts

How to Prove a Thesis Statement: Analyzing an Argument

Perfecting Your Thesis Statement

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Elevate your research paper with expert editing services

What is the Background in a Research Paper?

An effective Background section in your manuscript establishes the context for your study. And while original research requires novel findings, providing the necessary background information for these findings may be just as important. It lets your readers know that your findings are novel, important, and worthy of their time and attention.

Updated on October 3, 2022

A good Background section explains the history and nature of your research question in relation to existing literature – a “state of the art.” This section, along with the rationale, helps readers understand why you chose to study this problem and why your study is worthwhile. This article will show you how to do this.

Read on to better understand the:

- Real purpose of the Background section

- Typical length of a Background section and its placement

- Elements of an effective Background

What is the Background section of a research paper?

The Background section is an essential element of every study, answering:

- What do we already know about the topic?

- How does your study relate to what's been done so far in your field?

- What is its scope?

- Why does the topic warrant your interest and their interest?

- How did you develop the research question that you'll later introduce?

In grant writing, a Background section is often referred to as the “state of the art,” and this is a useful term to have in mind when writing this part of your paper.

What comes next?

After you make the above points,

- Formulate your research question/hypothesis . Research aims and objectives should be closely related to how you'll fill the gap you've identified in the literature. Your research gap is the central theme of your article and why people should read it.

- Summarize how you'll address it in the paper . Your methodology needs to be appropriate for addressing the “problem” you've identified.

- Describe the significance of your study . Show how your research fits into the bigger picture.

Note that the Background section isn't the same as the research rationale. Rather, it provides the relevant information the reader needs so they can follow your rationale. For example, it

- Explains scientific terms

- Provides available data and statistics on the topic

- Describes the methods used so far on your topic. Especially if these are different from what you're going to do. Take special care here, because this is often where peer reviewers focus intently.

This is a logical approach to what comes after the study's background. Use it and the reader can easily follow along from the broader information to the specific details that come later. Crucially, they'll have confidence that your analysis and findings are valid.

Where should the background be placed in a research paper?

Usually, the background comes after the statement of the problem, in the Introduction section. Logically, you need to provide the study context before discussing the research questions, methodology, and results.

The background can be found in:

The abstract

The background typically forms the first few sentences of the abstract. Why did you do the study? Most journals state this clearly. In an unstructured (no subheadings) abstract, it's the first sentence or two. In a structured abstract, it might be called the Introduction, Background, or State-of-the-Art.

PLOS Medicine , for example, asks for research article abstracts to be split into three sections: Background, Methods and Findings, and Conclusions. Journals in the humanities or social sciences might not clearly ask for it because articles sometimes have a looser structure than STEM articles.

The first part of the Introduction section

In the journal Nature , for example, the Introduction should be around 200 words and include

- Two to three sentences giving a basic introduction to the field.

- The background and rationale of the study are stated briefly.

- A simple phrase “Here we show ...”, or “In this study, we show ....” (to round out the Introduction).

The Journal of Organic Chemistry has similar author guidelines.

The Background as a distinct section

This is often the case for research proposals or some types of reports, as discussed above. Rather than reviewing the literature, this is a concise summary of what's currently known in the field relevant to the question being addressed in this proposed study.