- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

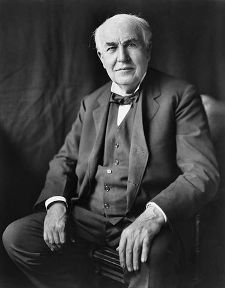

Thomas Edison

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 17, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

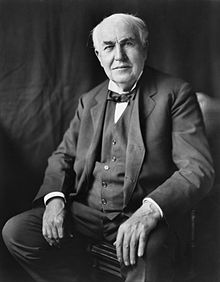

Thomas Edison was a prolific inventor and savvy businessman who acquired a record number of 1,093 patents (singly or jointly) and was the driving force behind such innovations as the phonograph, the incandescent light bulb, the alkaline battery and one of the earliest motion picture cameras. He also created the world’s first industrial research laboratory. Known as the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” for the New Jersey town where he did some of his best-known work, Edison had become one of the most famous men in the world by the time he was in his 30s. In addition to his talent for invention, Edison was also a successful manufacturer who was highly skilled at marketing his inventions—and himself—to the public.

Thomas Edison’s Early Life

Thomas Alva Edison was born on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio. He was the seventh and last child born to Samuel Edison Jr. and Nancy Elliott Edison, and would be one of four to survive to adulthood. At age 12, he developed hearing loss—he was reportedly deaf in one ear, and nearly deaf in the other—which was variously attributed to scarlet fever, mastoiditis or a blow to the head.

Thomas Edison received little formal education, and left school in 1859 to begin working on the railroad between Detroit and Port Huron, Michigan, where his family then lived. By selling food and newspapers to train passengers, he was able to net about $50 profit each week, a substantial income at the time—especially for a 13-year-old.

Did you know? By the time he died at age 84 on October 18, 1931, Thomas Edison had amassed a record 1,093 patents: 389 for electric light and power, 195 for the phonograph, 150 for the telegraph, 141 for storage batteries and 34 for the telephone.

During the Civil War , Edison learned the emerging technology of telegraphy, and traveled around the country working as a telegrapher. But with the development of auditory signals for the telegraph, he was soon at a disadvantage as a telegrapher.

To address this problem, Edison began to work on inventing devices that would help make things possible for him despite his deafness (including a printer that would convert electrical telegraph signals to letters). In early 1869, he quit telegraphy to pursue invention full time.

Edison in Menlo Park

From 1870 to 1875, Edison worked out of Newark, New Jersey, where he developed telegraph-related products for both Western Union Telegraph Company (then the industry leader) and its rivals. Edison’s mother died in 1871, and that same year he married 16-year-old Mary Stillwell.

Despite his prolific telegraph work, Edison encountered financial difficulties by late 1875, but one year later—with the help of his father—Edison was able to build a laboratory and machine shop in Menlo Park, New Jersey, 12 miles south of Newark.

With the success of his Menlo Park “invention factory,” some historians credit Edison as the inventor of the research and development (R&D) lab, a collaborative, team-based model later copied by AT&T at Bell Labs , the DuPont Experimental Station , the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) and other R&D centers.

In 1877, Edison developed the carbon transmitter, a device that improved the audibility of the telephone by making it possible to transmit voices at higher volume and with more clarity.

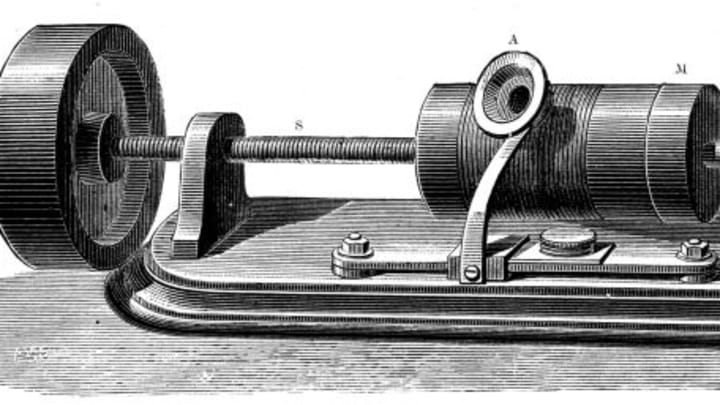

That same year, his work with the telegraph and telephone led him to invent the phonograph, which recorded sound as indentations on a sheet of paraffin-coated paper; when the paper was moved beneath a stylus, the sounds were reproduced. The device made an immediate splash, though it took years before it could be produced and sold commercially.

Edison and the Light Bulb

In 1878, Edison focused on inventing a safe, inexpensive electric light to replace the gaslight—a challenge that scientists had been grappling with for the last 50 years. With the help of prominent financial backers like J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilt family, Edison set up the Edison Electric Light Company and began research and development.

He made a breakthrough in October 1879 with a bulb that used a platinum filament, and in the summer of 1880 hit on carbonized bamboo as a viable alternative for the filament, which proved to be the key to a long-lasting and affordable light bulb. In 1881, he set up an electric light company in Newark, and the following year moved his family (which by now included three children) to New York.

Though Edison’s early incandescent lighting systems had their problems, they were used in such acclaimed events as the Paris Lighting Exhibition in 1881 and the Crystal Palace in London in 1882.

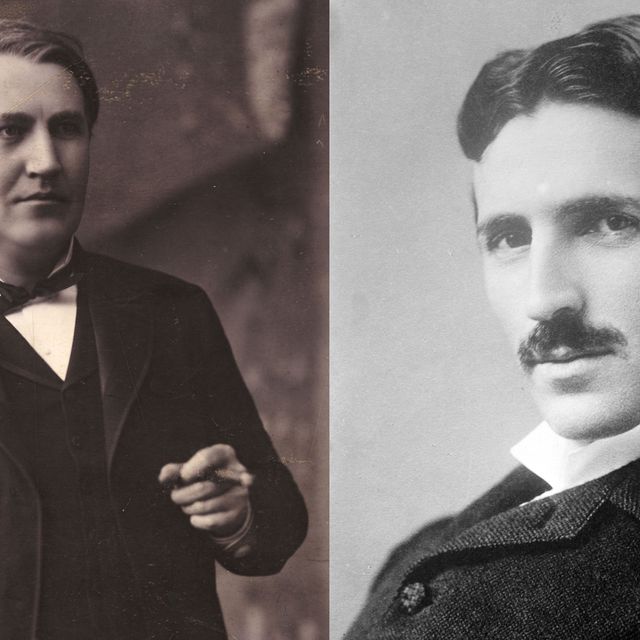

Competitors soon emerged, notably Nikola Tesla, a proponent of alternating or AC current (as opposed to Edison’s direct or DC current). By 1889, AC current would come to dominate the field, and the Edison General Electric Co. merged with another company in 1892 to become General Electric .

Later Years and Inventions

Edison’s wife, Mary, died in August 1884, and in February 1886 he remarried Mirna Miller; they would have three children together. He built a large estate called Glenmont and a research laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, with facilities including a machine shop, a library and buildings for metallurgy, chemistry and woodworking.

Spurred on by others’ work on improving the phonograph, he began working toward producing a commercial model. He also had the idea of linking the phonograph to a zoetrope, a device that strung together a series of photographs in such a way that the images appeared to be moving. Working with William K.L. Dickson, Edison succeeded in constructing a working motion picture camera, the Kinetograph, and a viewing instrument, the Kinetoscope, which he patented in 1891.

After years of heated legal battles with his competitors in the fledgling motion-picture industry, Edison had stopped working with moving film by 1918. In the interim, he had had success developing an alkaline storage battery, which he originally worked on as a power source for the phonograph but later supplied for submarines and electric vehicles.

In 1912, automaker Henry Ford asked Edison to design a battery for the self-starter, which would be introduced on the iconic Model T . The collaboration began a continuing relationship between the two great American entrepreneurs.

Despite the relatively limited success of his later inventions (including his long struggle to perfect a magnetic ore-separator), Edison continued working into his 80s. His rise from poor, uneducated railroad worker to one of the most famous men in the world made him a folk hero.

More than any other individual, he was credited with building the framework for modern technology and society in the age of electricity. His Glenmont estate—where he died in 1931—and West Orange laboratory are now open to the public as the Thomas Edison National Historical Park .

Thomas Edison’s Greatest Invention. The Atlantic . Life of Thomas Alva Edison. Library of Congress . 7 Epic Fails Brought to You by the Genius Mind of Thomas Edison. Smithsonian Magazine .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, a brief biography of thomas edison.

Last updated: February 26, 2015

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

211 Main Street West Orange, NJ 07052

973-736-0550 x11 Phones are monitored as staff are available with messages being checked Wednesday - Sunday. If a ranger is unavailable to take your call, we kindly ask that you leave us a detailed message with return contact information and we will be happy to get back to you as soon as possible. Thank you.

Stay Connected

Biography of Thomas Edison, American Inventor

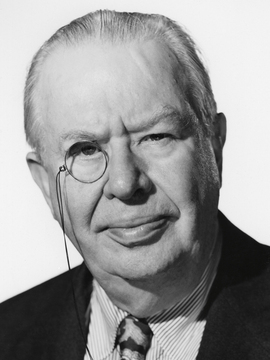

Underwood Archives / Getty Images

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847–October 18, 1931) was an American inventor who transformed the world with inventions including the lightbulb and the phonograph. He was considered the face of technology and progress in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Fast Facts: Thomas Edison

- Known For : Inventor of groundbreaking technology, including the lightbulb and the phonograph

- Born : February 11, 1847 in Milan, Ohio

- Parents : Sam Edison Jr. and Nancy Elliott Edison

- Died : October 18, 1931 in West Orange, New Jersey

- Education : Three months of formal education, homeschooled until age 12

- Published Works : Quadruplex telegraph, phonograph, unbreakable cylinder record called the "Blue Ambersol," electric pen, a version of the incandescent lightbulb and an integrated system to run it, motion picture camera called a kinetograph

- Spouse(s) : Mary Stilwell, Mina Miller

- Children : Marion Estelle, Thomas Jr., William Leslie by Mary Stilwell; and Madeleine, Charles, and Theodore Miller by Mina Miller

Thomas Alva Edison was born to Sam and Nancy on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio, the son of a Canadian refugee and his schoolteacher wife. Edison's mother Nancy Elliott was originally from New York until her family moved to Vienna, Canada, where she met Sam Edison, Jr., whom she later married. Sam was the descendant of British loyalists who fled to Canada at the end of the American Revolution, but when he became involved in an unsuccessful revolt in Ontario in the 1830s he was forced to flee to the United States. They made their home in Ohio in 1839. The family moved to Port Huron, Michigan, in 1854, where Sam worked in the lumber business.

Education and First Job

Known as "Al" in his youth, Edison was the youngest of seven children, four of whom survived to adulthood, and all of them were in their teens when Edison was born. Edison tended to be in poor health when he was young and was a poor student. When a schoolmaster called Edison "addled," or slow, his furious mother took him out of the school and proceeded to teach him at home. Edison said many years later, "My mother was the making of me. She was so true, so sure of me, and I felt I had someone to live for, someone I must not disappoint." At an early age, he showed a fascination for mechanical things and chemical experiments.

In 1859 at the age of 12, Edison took a job selling newspapers and candy on the Grand Trunk Railroad to Detroit. He started two businesses in Port Huron, a newsstand and a fresh produce stand, and finagled free or very low-cost trade and transport in the train. In the baggage car, he set up a laboratory for his chemistry experiments and a printing press, where he started the "Grand Trunk Herald," the first newspaper published on a train. An accidental fire forced him to stop his experiments on board.

Loss of Hearing

Around the age of 12, Edison lost almost all of his hearing. There are several theories as to what caused this. Some attribute it to the aftereffects of scarlet fever, which he had as a child. Others blame it on a train conductor boxing his ears after Edison caused a fire in the baggage car, an incident Edison claimed never happened. Edison himself blamed it on an incident in which he was grabbed by his ears and lifted to a train. He did not let his disability discourage him, however, and often treated it as an asset since it made it easier for him to concentrate on his experiments and research. Undoubtedly, though, his deafness made him more solitary and shy in dealing with others.

Telegraph Operator

In 1862, Edison rescued a 3-year-old from a track where a boxcar was about to roll into him. The grateful father, J.U. MacKenzie, taught Edison railroad telegraphy as a reward. That winter, he took a job as a telegraph operator in Port Huron. In the meantime, he continued his scientific experiments on the side. Between 1863 and 1867, Edison migrated from city to city in the United States, taking available telegraph jobs.

Love of Invention

In 1868, Edison moved to Boston where he worked in the Western Union office and worked even more on inventing things. In January 1869 Edison resigned from his job, intending to devote himself full time to inventing things. His first invention to receive a patent was the electric vote recorder, in June 1869. Daunted by politicians' reluctance to use the machine, he decided that in the future he would not waste time inventing things that no one wanted.

Edison moved to New York City in the middle of 1869. A friend, Franklin L. Pope, allowed Edison to sleep in a room where he worked, Samuel Laws' Gold Indicator Company. When Edison managed to fix a broken machine there, he was hired to maintain and improve the printer machines.

During the next period of his life, Edison became involved in multiple projects and partnerships dealing with the telegraph. In October 1869, Edison joined with Franklin L. Pope and James Ashley to form the organization Pope, Edison and Co. They advertised themselves as electrical engineers and constructors of electrical devices. Edison received several patents for improvements to the telegraph. The partnership merged with the Gold and Stock Telegraph Co. in 1870.

American Telegraph Works

Edison also established the Newark Telegraph Works in Newark, New Jersey, with William Unger to manufacture stock printers. He formed the American Telegraph Works to work on developing an automatic telegraph later in the year.

In 1874 he began to work on a multiplex telegraphic system for Western Union, ultimately developing a quadruplex telegraph, which could send two messages simultaneously in both directions. When Edison sold his patent rights to the quadruplex to the rival Atlantic & Pacific Telegraph Co. , a series of court battles followed—which Western Union won. Besides other telegraph inventions, he also developed an electric pen in 1875.

Marriage and Family

His personal life during this period also brought much change. Edison's mother died in 1871, and he married his former employee Mary Stilwell on Christmas Day that same year. While Edison loved his wife, their relationship was fraught with difficulties, primarily his preoccupation with work and her constant illnesses. Edison would often sleep in the lab and spent much of his time with his male colleagues.

Nevertheless, their first child Marion was born in February 1873, followed by a son, Thomas, Jr., in January 1876. Edison nicknamed the two "Dot" and "Dash," referring to telegraphic terms. A third child, William Leslie, was born in October 1878.

Mary died in 1884, perhaps of cancer or the morphine prescribed to her to treat it. Edison married again: his second wife was Mina Miller, the daughter of Ohio industrialist Lewis Miller, who founded the Chautauqua Foundation. They married on February 24, 1886, and had three children, Madeleine (born 1888), Charles (1890), and Theodore Miller Edison (1898).

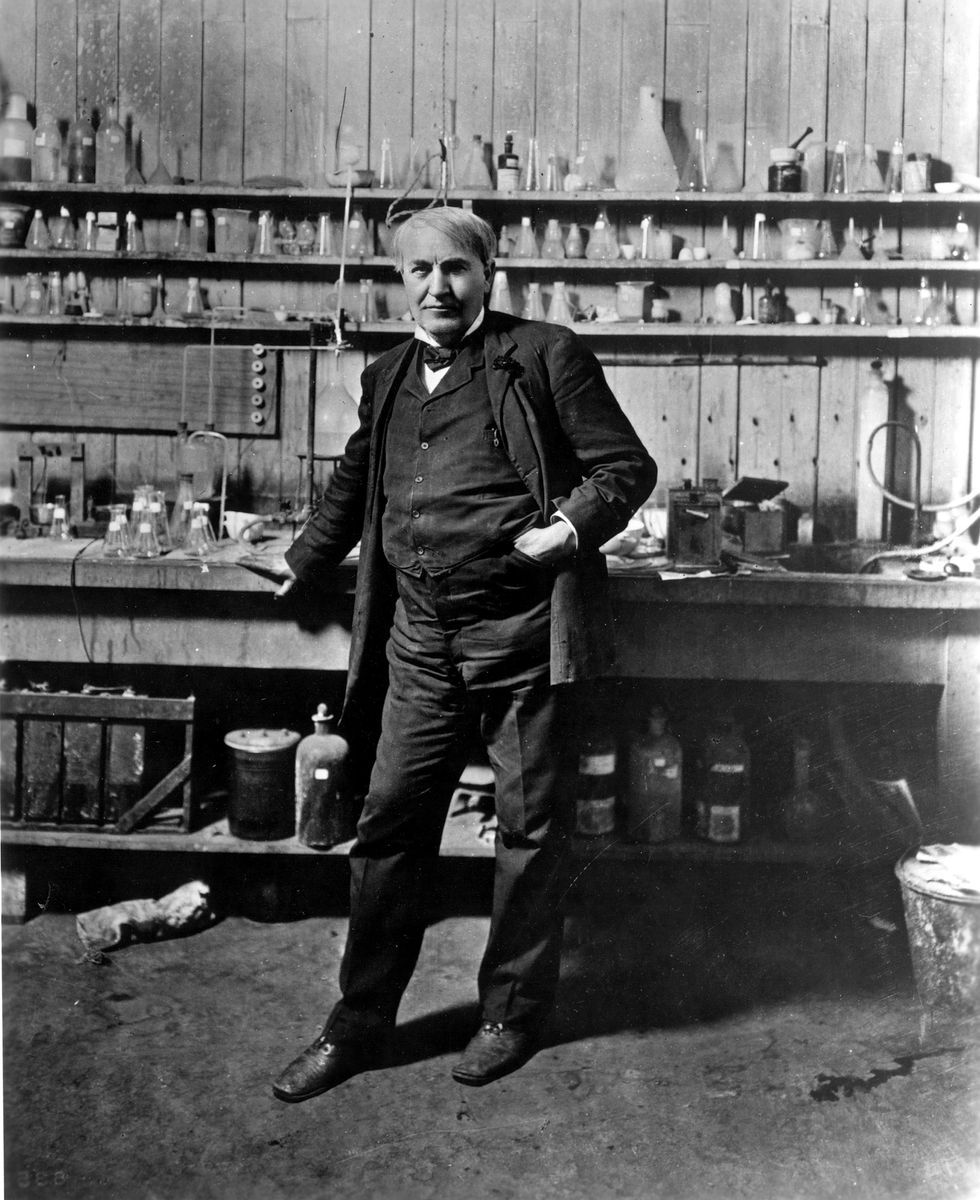

Edison opened a new laboratory in Menlo Park , New Jersey, in 1876. This site later become known as an "invention factory," since they worked on several different inventions at any given time there. Edison would conduct numerous experiments to find answers to problems. He said, "I never quit until I get what I'm after. Negative results are just what I'm after. They are just as valuable to me as positive results." Edison liked to work long hours and expected much from his employees .

In 1879, after considerable experimentation and based on 70 years work of several other inventors, Edison invented a carbon filament that would burn for 40 hours—the first practical incandescent lightbulb .

While Edison had neglected further work on the phonograph, others had moved forward to improve it. In particular, Chichester Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter developed an improved machine that used a wax cylinder and a floating stylus, which they called a graphophone . They sent representatives to Edison to discuss a possible partnership on the machine, but Edison refused to collaborate with them, feeling that the phonograph was his invention alone. With this competition, Edison was stirred into action and resumed his work on the phonograph in 1887. Edison eventually adopted methods similar to Bell and Tainter's in his phonograph.

Phonograph Companies

The phonograph was initially marketed as a business dictation machine. Entrepreneur Jesse H. Lippincott acquired control of most of the phonograph companies, including Edison's, and set up the North American Phonograph Co. in 1888. The business did not prove profitable, and when Lippincott fell ill, Edison took over the management.

In 1894, the North American Phonograph Co. went into bankruptcy, a move which allowed Edison to buy back the rights to his invention. In 1896, Edison started the National Phonograph Co. with the intent of making phonographs for home amusement. Over the years, Edison made improvements to the phonograph and to the cylinders which were played on them, the early ones being made of wax. Edison introduced an unbreakable cylinder record, named the Blue Amberol, at roughly the same time he entered the disc phonograph market in 1912.

The introduction of an Edison disc was in reaction to the overwhelming popularity of discs on the market in contrast to cylinders. Touted as being superior to the competition's records, the Edison discs were designed to be played only on Edison phonographs and were cut laterally as opposed to vertically. The success of the Edison phonograph business, though, was always hampered by the company's reputation of choosing lower-quality recording acts. In the 1920s, competition from radio caused the business to sour, and the Edison disc business ceased production in 1929.

Ore-Milling and Cement

Another Edison interest was an ore milling process that would extract various metals from ore. In 1881, he formed the Edison Ore-Milling Co., but the venture proved fruitless as there was no market for it. He returned to the project in 1887, thinking that his process could help the mostly depleted Eastern mines compete with the Western ones. In 1889, the New Jersey and Pennsylvania Concentrating Works was formed, and Edison became absorbed by its operations and began to spend much time away from home at the mines in Ogdensburg, New Jersey. Although he invested much money and time into this project, it proved unsuccessful when the market went down, and additional sources of ore in the Midwest were found.

Edison also became involved in promoting the use of cement and formed the Edison Portland Cement Co. in 1899. He tried to promote the widespread use of cement for the construction of low-cost homes and envisioned alternative uses for concrete in the manufacture of phonographs, furniture, refrigerators, and pianos. Unfortunately, Edison was ahead of his time with these ideas, as the widespread use of concrete proved economically unfeasible at that time.

Motion Pictures

In 1888, Edison met Eadweard Muybridge at West Orange and viewed Muybridge's Zoopraxiscope. This machine used a circular disc with still photographs of the successive phases of movement around the circumference to recreate the illusion of movement. Edison declined to work with Muybridge on the device and decided to work on his motion picture camera at his laboratory. As Edison put it in a caveat written the same year, "I am experimenting upon an instrument which does for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear."

The task of inventing the machine fell to Edison's associate William K. L. Dickson. Dickson initially experimented with a cylinder-based device for recording images, before turning to a celluloid strip. In October 1889, Dickson greeted Edison's return from Paris with a new device that projected pictures and contained sound. After more work, patent applications were made in 1891 for a motion picture camera, called a Kinetograph, and a Kinetoscope, a motion picture peephole viewer.

Kinetoscope parlors opened in New York and soon spread to other major cities during 1894. In 1893, a motion picture studio, later dubbed the Black Maria (the slang name for a police paddy wagon which the studio resembled), was opened at the West Orange complex. Short films were produced using a variety of acts of the day. Edison was reluctant to develop a motion picture projector, feeling that more profit was to be made with the peephole viewers.

When Dickson assisted competitors on developing another peephole motion picture device and the eidoscope projection system, later to develop into the Mutoscope, he was fired. Dickson went on to form the American Mutoscope Co. along with Harry Marvin, Herman Casler, and Elias Koopman. Edison subsequently adopted a projector developed by Thomas Armat and Charles Francis Jenkins and renamed it the Vitascope and marketed it under his name. The Vitascope premiered on April 23, 1896, to great acclaim.

Patent Battles

Competition from other motion picture companies soon created heated legal battles between them and Edison over patents. Edison sued many companies for infringement. In 1909, the formation of the Motion Picture Patents Co. brought a degree of cooperation to the various companies who were given licenses in 1909, but in 1915, the courts found the company to be an unfair monopoly.

In 1913, Edison experimented with synchronizing sound to film. A Kinetophone was developed by his laboratory and synchronized sound on a phonograph cylinder to the picture on a screen. Although this initially brought interest, the system was far from perfect and disappeared by 1915. By 1918, Edison ended his involvement in the motion picture field.

In 1911, Edison's companies were re-organized into Thomas A. Edison, Inc. As the organization became more diversified and structured, Edison became less involved in the day-to-day operations, although he still had some decision-making authority. The goals of the organization became more to maintain market viability than to produce new inventions frequently.

A fire broke out at the West Orange laboratory in 1914, destroying 13 buildings. Although the loss was great, Edison spearheaded the rebuilding of the lot.

World War I

When Europe became involved in World War I, Edison advised preparedness and felt that technology would be the future of war. He was named the head of the Naval Consulting Board in 1915, an attempt by the government to bring science into its defense program. Although mainly an advisory board, it was instrumental in the formation of a laboratory for the Navy that opened in 1923. During the war, Edison spent much of his time doing naval research, particularly on submarine detection, but he felt the Navy was not receptive to many of his inventions and suggestions.

Health Issues

In the 1920s, Edison's health became worse and he began to spend more time at home with his wife. His relationship with his children was distant, although Charles was president of Thomas A. Edison, Inc. While Edison continued to experiment at home, he could not perform some experiments that he wanted to at his West Orange laboratory because the board would not approve them. One project that held his fascination during this period was the search for an alternative to rubber.

Death and Legacy

Henry Ford , an admirer and a friend of Edison's, reconstructed Edison's invention factory as a museum at Greenfield Village, Michigan, which opened during the 50th anniversary of Edison's electric light in 1929. The main celebration of Light's Golden Jubilee, co-hosted by Ford and General Electric, took place in Dearborn along with a huge celebratory dinner in Edison's honor attended by notables such as President Hoover , John D. Rockefeller, Jr., George Eastman , Marie Curie , and Orville Wright . Edison's health, however, had declined to the point that he could not stay for the entire ceremony.

During the last two years of his life, a series of ailments caused his health to decline even more until he lapsed into a coma on October 14, 1931. He died on October 18, 1931, at his estate, Glenmont, in West Orange, New Jersey.

- Israel, Paul. "Edison: A Life of Invention." New York, Wiley, 2000.

- Josephson, Matthew. "Edison: A Biography." New York, Wiley, 1992.

- Stross, Randall E. "The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World." New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007.

- Thomas Edison's Greatest Inventions

- The Failed Inventions of Thomas Alva Edison

- What Was Menlo Park?

- Thomas Edison's 'Muckers'

- Edison's Invention of the Phonograph

- History of Electricity

- Major Innovators of Early Motion Pictures

- Great Father-Son Inventor Duos

- Famous Thomas Edison Quotes

- A Timeline for the Invention of the Lightbulb

- The Most Important Inventions of the 19th Century

- Notable American Inventors of the Industrial Revolution

- A Look at the 6 Technologies That Revolutionized Communications

- Biography of Granville T. Woods, American Inventor

- History and Timeline of the Battery

- Reginald Fessenden and the First Radio Broadcast

A Brief Biography of Thomas Alva Edison

Written by John D. Venable

“But the man whose clothes were always wrinkled, whose hair was always tousled and who frequently lacked a shave probably did more than any other one man to influence the industrial civilization in which we live.

To him we owe the phonograph and motion picture which spice hours of leisure; the universal electric motor and the nickel-iron-alkaline storage battery with their numberless commercial uses; the magnetic ore separator, the fluorescent lamp, the basic principles of modern electronics. Medicine thanks him for the fluoroscope, which he left to the public domain without patent. Chemical research follows the field he opened in his work on coal-tar derivatives, synthetic carbolic acid, and a source of natural rubber that can be grown in the United States.

His greatest contribution, perhaps, was the incandescent lamp – the germ from which sprouted the great power utility systems of our day…Although his formal education stopped at the age of 12, his whole life was consumed by a passion for self-education, and he was a moving force behind the establishment of a great scientific journal.

The number of patents – 1100 – far exceeds that of any other inventor. And the 2500 notebooks in which he recorded the progress of thousands of experiments are still being gleaned of unused material. Once, asked in what his interests lay, Edison smilingly responded, ‘Everything.’ If we ask ourselves where the fruits of his life are seen, we might well answer, ‘Everywhere.’”

Thomas Alva Edison

The story of a great american .

Journeying from Holland, the Edison family originally landed in Elizabethport, New Jersey, about 1730. In Colonial times, they farmed a large tract of land not far from West Orange, New Jersey, where Thomas A. Edison made his home some 160 years later. Their fortunes fluctuated with their politics. Like many well-to-do landowners of that time, John Edison, a great-grandfather of the inventor, remained a Loyalist during the revolution, suffered imprisonment and was under sentence of execution from which he was saved only through the efforts of his own and his wife’s prominent Whig relatives. His lands were confiscated, however, and the family migrated to Nova Scotia, where they remained until 1811, when they moved to Vienna, Ontario. Edison’s grandfather, Captain Samuel Edison, served with the British in the War of 1812.

In Ontario, Edison’s father, another Samuel, met and married Nancy Elliott, schoolteacher and daughter of a minister whose family had originally come from Connecticut where her grandfather Ebenezer Elliott had served as a captain in Washington’s army.

The younger Samuel now became involved in another political struggle – the much later and unsuccessful Canadian counterpart of the American Revolution known as the Papineau-MacKenzie Rebellion. Upon the failure of this movement, he was forced to escape across the border to the United States, and after innumerable dangers and hardships, finally reached the town of Milan, Ohio, where he decided to settle.

Thomas Edison’s Early Days

The brick cottage in which Thomas Alva Edison was born on February 11, 1847, still stands in Milan, Ohio. Its humble size and simple design serve as a constant reminder that in America, a humble beginning does not hamper the rise to success.

Even as a boy of pre-school age, “Al” Edison was extraordinarily inquisitive; he wanted to find out things for himself. The story is told of how he tried – unsuccessfully – to solve the mystery of hatching eggs by sitting on them himself, in his brother-in-law’s barn. Among other tales of his youth in Milan are his narrow escape from drowning in the barge canal that ran alongside the Edison home, and his public spanking in the town square after he accidentally had set fire to his father’s barn.

When he was seven years old, his family moved again; this time to Port Huron, Michigan. But, unlike their earlier migrations by wagon, the trip was made by railroad train and lake schooner.

Edison’s formal schooling was of short duration and of little value to him. To use his own words, he “was usually at the foot of the class.” His teacher did not have the patience to cope with so active and inquisitive a mind, so his mother withdrew him from school and capably undertook the task of his education herself. In spite of his lack of formal schooling, Edison recognized the great worth of education and, in his later years, sponsored the famous Edison scholarships for outstanding high school graduates who were selected each year through a national contest.

Young Tom’s First Laboratory

Most of Edison’s vast knowledge was acquired through independent study and training. At the age of eleven, for example, he had his own chemical laboratory in the cellar of his Port Huron home and had read such books as Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” Sears’ “History of the World,” Burton’s “Anatomy of Melancholy,” and the “Dictionary of Sciences.”

At twelve, his parents permitted him to take a job as newsboy and candy “butcher” on the train of the Grand Trunk Railroad running from Port Huron to Detroit. In this, his first job, Edison exhibited a knack for business and an ambition that far exceeded that of the average boy of his years. He maintained a chemical laboratory in the train’s baggage car, which also served to house a printing press on which young Edison ran off copies of “The Weekly Herald,” the first newspaper ever edited, published and printed aboard a moving train. In addition, he became a middle-man for fresh vegetables and fruit, buying from the farmers along the route and selling to Detroit markets.

When only thirteen years old, he was earning several dollars a day, a tidy sum even for a man in that period. Already he was putting into practice a theory followed through his life – that hard work and sound thinking recognize no substitutes.

One of the most widely known stories about Edison is the one which attributes his deafness to a quick-tempered trainman who soundly boxed his ears when Edison’s traveling laboratory caused a fire to break out in the baggage car.

Only part of the tale is true: the fire broke out and the trainman boxed his ears, but Edison himself never believed his deafness resulted from this incident. He traced it to a later occasion when another trainman thoughtlessly picked him up by the ears to help him aboard a train that was pulling out of a station.

It was during this period that a dramatic incident occurred which altered the entire course of Edison’s career and which, therefore, may well have also altered the course of world progress. At Mt. Clemens, Michigan, the young Edison risked his own life to save the station agent’s little boy from death under a moving freight car. The grateful father taught him telegraphy as a reward. Edison’s association with telegraphy brought to a climax his interest in electricity – a word with which the name of Edison was to become inseparably associated – and led him into studies and experiments which resulted in some of the world’s greatest inventions.

A Telegrapher at Seventeen

Edison’s skill as a sender and receiver earned him a job as a regular telegrapher on the Grand Trunk line at Stratford Junction, Ontario, when only seventeen years of age. His creative imagination, however, proved his downfall in this instance. He was fired when a supervisor happened across the secret of one of the young inventor’s creations – a device for automatically “reporting in” on the wire in Morse code every hour, when, in actuality, Edison was napping to make up for sleep lost in pursuing his studies.

As a telegrapher, Edison traveled throughout the middle west, always studying and experimenting to improve the crude telegraph apparatus of the era. Turning eastward, Edison went to Boston where he went to work for Western Union as an operator. In his spare time, he created his first invention to be patented – a machine for electrically recording and counting the “Ayes” and “Nays” cast by members of a legislative body. While the invention earned him no money, because members of Congress could not be interested in any device to speed up proceedings, it did teach him a commercial lesson. Then and there he decided never again to invent anything unless he was sure it was wanted.

From Boston, Edison went to New York, where he landed, poor and in debt, in 1869. While working as an employee of the Gold and Stock Telegraph Company and later as a partner with Franklin L. Pope in their own electrical engineering company. Edison invented the Universal Stock Printer. For this device he received $40,000, the first money an invention brought him.

To Edison, the mere possession of money meant nothing; its only value rested in its ability to provide the tools and equipment necessary for further work and experiment. With the $40,000 he opened a factory in Newark, New Jersey, in 1870, where he manufactured stock tickers and devoted his energies to invention.

By the time he was twenty-three, his established methods of hard work and sound thinking had catapulted him to a point on the road to success rarely attained by one so young.

Edison’s Hectic Years

With his success as an inventor and manufacturer at the age of twenty-three, Thomas Alva Edison in 1870 plunged into a period of feverish endeavor that has no parallel in the lives of other great men of science. His fertile brain and boundless energy drove him from one great invention to another, each of which, in turn, launched new manufacturing enterprises, giving employment to thousands of people. Few were his working days that did not extend through twenty of the twenty-four hours. The group of men who worked closely with him as his immediate assistants earned him the name of the “insomnia squad” as they tried valiantly to follow the pace set by the “boss.”

Actually there was no “boss” since, as the men who worked with him have testified, he worked harder, longer, and looked less like the owner of the plant than anyone present. A casual visitor, we are told, would have regarded Edison as one of the least likely persons to have been in charge, judging by outward appearances. Democracy walked with him through his laboratory.

Work in his Newark plants constantly demanded more time for production than creation, so in 1876, in order to devote more of his energies to invention, he turned the management of his factories over to trusted assistants and established laboratories at Menlo Park, New Jersey.

Before moving to Menlo Park, however, Edison made one of his great discoveries, an electrical phenomenon he called “etheric force.” This was the discovery that electrically generated waves would traverse an open circuit – the principle on which wireless telegraphy and radio are founded. The idea that electricity would traverse space was almost beyond belief at that time.

In a related field of research, Edison also discovered that messages could be sent through space by induction, in which a current generated in one set of wires induced a like current to flow through another set of wires between which no connection existed. As a result of this research, he received patents in 1885 on the transmission of signals, by induction, between moving train and a station and between ship and shore.

Edison Aids Marconi

Guglielmo Marconi had become a personal friend of Edison’s and, because of this friendship, Edison made these patents available to him rather than to a competitor who offered more money. Thus, these patents helped Marconi to become recognized as the inventor of the wireless telegraph.

Edison was the first to give credit where credit was due, even though some of his earlier experiments and discoveries laid the groundwork for his successors.

It was at Newark, too, that Edison invented the “electric pen,” forerunner of the mimeograph machine.

With the opening of his Menlo Park laboratories, Edison devoted most of his time to invention rather than to the manufacture of things. The results were astounding.

One of the greatest of the many “firsts” attributed to Edison is the carrying out of research on an organized basis. Before Edison did this, the process of invention was usually a one-man and one-brain undertaking. At Menlo Park, Edison surrounded himself with scientific apparatus and trained assistants who handled the drudgery and time-consuming details of research, making possible his most acclaimed invention, the incandescent electric lamp. Menlo Park itself was an experiment for Edison, and he did not really perfect his invention of organized research in industry until eleven years later, when he transferred operations to West Orange on a greatly enlarged scale.

Edison’s Favorite – The Phonograph

The carbon telephone transmitter which made the telephone commercially practical was invented by Edison in 1877, the same year he gave the world the phonograph.

Until Edison produced the carbon transmitter, telephone communication had been highly impractical. He sold his rights in the invention to Western Union which, in turn, reached an agreement with the company backed by Alexander Graham Bell, and for many years thereafter telephone instruments bore the names of both Bell and Edison. To use Edison’s expression, it was fifty-fifty – he invented the transmitter and Bell the receiver.

Edison’s carbon transmitter later helped to make radio possible in that the same principle was adopted in developing a practical microphone.

The phonograph not only was Edison’s favorite invention, but it probably was one of the most original ever created. In most instances, the inventor is the man who first perfects a device or method for achieving a result which for a long period of time had been a goal of experimentation and research by others as well as himself. But in the case of the phonograph, the idea of recording sound for later reproduction had not been conceived until Edison received inspiration while experimenting with the automatic telegraph. Just as amazing, perhaps, is the fact that his first phonograph, although just a crude model, was a complete success.

Lawyer Steals Edison Patents

Edison worked at breakneck speed during the decade following 1876. Not alone was his own tireless constitution responsible for this pace; the period was one of unending competition and no holds were barred by his competitors. Despite his almost inhuman capacity for work, others in some instances gained recognition for creations that were rightfully his. On one occasion, a lawyer entrusted to file applications for fifty-seven new patents stole the papers instead and sold them to Edison’s rivals.

The desire for revenge formed no part of Edison’s character, as revealed by his reaction to the theft of these patents. Even after long years had gone by he steadfastly refused to name the dishonest attorney. “His family might suffer,” he told associates who suggested that he make public the lawyer’s name.

Edison followed a policy which, absurd though it may sound today in contrast to the secrecy now surrounding most inventive endeavor, permitted the press to know and report even minute advances he made in experiments leading to the perfection of the first practical incandescent lamp.

The Edison Lamp

Others before and in the same period with Edison toiled long and hard to produce a practical incandescent lamp. The idea was not original with him, but it required the Edison genius to solve the difficult problems involved.

Many persons tried to deprive Edison of the honor of having been the first to perfect a practical incandescent electric lamp, but they all met with failure. Edison’s claim was to genuine to be set aside, even by the courts which, for one reason or another, might have been inclined to bias.

An English jurist considering the claim of an English inventor, for example, might well be inclined to rule against Edison, if such a ruling were at all possible. But Lord Justice Fry, sitting in one of Great Britain’s Royal Courts of Justice, made this commentary on the claims of Joseph W. Swan, an English inventor: “Swan could not do what Edison did…the difference between a carbon rod (as employed by Swan) and a carbon filament (Mr. Edison’s method) was the difference between success and failure.

“Mr. Edison used the filament instead of the rod for a definite purpose, and by diminution of the sectional area made a physical law subserve the end he had in view. The smallness of size, then, was no casual matter, but was intended to bring about, and did bring about, a result which the rod could never produce, and so converted failure into success.”

Edison realized that the invention of a practical lamp alone was not enough to replace gas as the most-used means of lighting. Therefore, his work on the electric light is even more astonishing, because in addition to perfecting a commercially practical lamp he also invented a ‘complete generation and distribution system, including dynamos, conductors, fuses, meters, sockets, and numerous other devices. Of 1,097 United States patents granted to Edison during his lifetime – by far the greatest number ever granted to one individual – 356 dealt with electric lighting and the generation and distribution of electricity.

The "Edison Effect"

The year 1883 was significant for Edison in that, by his discovery of what was to become known as the “Edison effect,” he pushed aside a veil of darkness behind which were to be found all the wonders of electronics. Edison in this achievement discovered the previously unknown phenomenon by which an independent wire or plate, when placed between the legs of the filament in an electric bulb, serves as a valve to control the flow of current. This discovery unearthed the fundamental principle on which rests the modern science of electronics.

In that year, 1883, Edison filed a patent on an electrical indicator employing the “Edison effect,” the first application in the field of electronics.

The facilities of Menlo Park were proving inadequate to meet the requirements of Edison’s amazing ability. He began looking around for a place more suitable for his needs. This he found in the little Essex County community of West Orange in northern New Jersey. He gave the orders that set workmen to the task of building a new and greater research laboratory.

The West Orange Laboratory

Thomas Alva Edison entered into a new and the fullest phase of his career when, at age of forty, he moved his talents and tools from Menlo Park to his great new laboratory at West Orange, New Jersey, on November 24, 1887.

One of his first undertakings was the development of his favorite creation, the phonograph. The pressure of his work in connection with the perfection and installation of electric lighting systems throughout the country had made it impossible for him to concentrate on the phonograph, but now he went to work in earnest to see that the instrument fulfilled the high destiny he had held out for it from its beginning ten years earlier.

During the first four years of his occupancy of his new laboratory at West Orange, he took out more than eighty patents on improvements on the cylinder phonograph and its businessman’s counterpart, the dictating machine.

At the same time, Edison interested himself in an entirely different field, one that was as new to the world as it was to him. That field was the motion picture. Eadweard Muybridge and others had done some experimental work, but had only hinted of motion pictures. Muybridge, for example, by the employment of multiple cameras strung along a racetrack, had taken successive shots of a trotting horse, but he offered no method whereby the pictures could be viewed in motion.

The Motion Picture Camera

Two things led Edison to the invention of the motion picture camera: His idea that motion could be captured by having one camera that would take repeated pictures at high speed, and a new celluloid film developed by George Eastman for use in still photography that proved adaptable to Edison’s proposed camera.

To Edison’s mind, motion pictures would do for the eye what the phonograph did for the ear. Thus, we find that on Oct. 6, 1889, when they first projected an experimental motion picture in his laboratory, he gave birth to sound pictures as well. The first movie actually was a “talkie.” The picture was accompanied by synchronized sound from a phonograph record.

He applied for a patent on the motion picture camera on July 31, 1891. The first commercial showing of motion pictures occurred three years later, April 14, 1894, with the opening of a “peephole” Kinetoscope parlor at 1155 Broadway, New York City.

Several men developed machines for projecting motion pictures. The best such projector, to Edison’s mind, was one built by Thomas Armat. Edison acquired rights to Armat’s crude machine and then perfected it in his West Orange laboratory.

Commercial projection of motion pictures as we know it today began on April 23, 1896, at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall, New York City, where the Edison Vitascope, embodying the basic principles of Armat’s invention with improvements by Edison, was used.

The vitascope was Edison’s name for the motion picture projector. When he added sound, he called it the kinetophone, which he introduced commercially in 1913, or 13 years before Hollywood adopted that means of improving motion picture entertainment.

With Wilhelm Konrad Roentgen’s discovery of the X-ray in 1895, Edison turned his attention to the mysteries of these invisible rays. Within a few months he developed the fluoroscope, which invention he did not patent, choosing to leave it to the public domain because of its universal need in medicine and surgery. On May 16, 1896, he applied for a patent on the first fluorescent electric light, an invention that stemmed directly from his experimentation with the X-ray.

At the turn of the century, Edison propelled himself into one of the greatest sagas of science – his search for the acidless battery. Others scoffed at his theory that somewhere in nature there existed the elements for a battery which would not destroy itself by corrosive action, but Edison was not to be denied. After 10 years exhaustive experimentation he produced the alkaline storage battery, which today is employed in hundreds of industrial applications, such as providing power for mine haulage and inter- and intra-plant transportation, and in railway train lighting.

No field of scientific endeavor seemed foreign to his talents. When, in 1914, a shortage of carbolic acid developed because World War I had cut off European supplies, Edison quickly devised a method of making domestic carbolic acid and was producing a ton a day within a month.

Edison and the War

New problems were heaped on Edison by the approaching entry of the United States into the war and the destruction by fire of his giant West Orange manufacturing plant. Almost before the embers died, new buildings began to rise from the ruins.

America at that time was almost entirely dependent upon foreign sources for fundamental coal-tar derivatives vital to many manufacturing processes. These derivatives were to become increasingly essential for the production of explosives, so Edison established plants for their manufacture. His work is recognized as having laid the groundwork for the most important development of the coal-tar chemical industry in the nation today.

Josephus Daniels, then-Secretary of the Navy, foresaw the country’s need for technological advances in its preparedness program. His mind turned to one man, Thomas Edison, to undertake such a program, and in 1915, Edison became president of the newly created Naval Consulting Board, forerunner of the Navy Department’s great research division of today. A colossal bronze head of the inventor, honoring him as the founder of the Naval Research Laboratories, was unveiled December 3, 1952, on the mall at the Anacostia, Maryland, Laboratories.

Edison arranged for leading scientists to serve with him on the consulting board and also made available to the government the facilities of his laboratory. Much of the consulting board’s effort was directed against the German submarine menace. Among the many inventions and ideas turned over to the Navy were devices and methods for detecting submarines by sound from moving vessels and for detecting enemy planes, for locating gun positions by range sounding, improved torpedoes, a high-speed signalling shutter for searchlights, and underwater searchlights. These and many other devices and formulas of prime importance came out of the Edison laboratory.

With the end of the war, Edison, although he had passed the 70 mark, thought only in terms of scientific and industrial progress. There would be time enough to think of taking it easy when he reached 100, he said. “My desire,” he once said of this period of his life, “is to do everything within my power to further free the people from drudgery, and create the largest possible measure of happiness, and prosperity.”

Honors Come to Edison

A great many honors and awards had been bestowed upon Edison by persons, societies, and countries throughout the world. To him, such things were nice to have but were not to be sought after. He could never get over being embarrassed when some new medal came his way. But one of his greatest honors was yet to come. On Oct. 20, 1928, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor – the nation’s highest award in recognition of services rendered.

A year later, on Oct. 21, 1929, the 50th anniversary of his invention of the incandescent light, the world again paid homage to him. In ceremonies participated in by Herbert Hoover, then-president of the United States, Henry Ford, Albert Einstein, and other world figures, Edison re-enacted the making of the first practical incandescent lamp.

Time was running out for Edison, even though his keen mind and energies refused to admit it. Creative thought and hard work still constituted his creed, and at the age of 80 he was launched on another great experiment. Remembering his nation’s lack of preparedness for World War I, he attacked the problem of rubber so that, in the event of another war, the United States would not be dependent upon foreign sources for this vital material. From goldenrod grown in his experimental gardens at Fort Myers, Fla., Edison was to produce rubber before his death.

A peaceful death enveloped him at his home, Glenmont, in Llewellyn Park, West Orange, on Oct. 18, 1931. He was 84 years old. His lifetime had embraced four wars and as many depressions. His achievements, more so than those of any one man, had helped to lift America to the pinnacle of greatness. The world was his beneficiary.

Thomas Edison

By jake rossen | oct 24, 2019.

SCIENTISTS (1847–1931); MILAN, OHIO

Thomas Alva Edison was an inventor unlike any throughout history—and his impact can still be felt in your everyday life. Born in Milan, Ohio, on February 11, 1847, Edison's inventions, which included perfecting the light bulb and phonograph, radically transformed modern civilization and helped make the 20th century one of the most technologically progressive eras ever.

1. Thomas Edison's list of inventions includes more than just the light bulb.

While Thomas Edison's most enduring contribution to modern life will forever remain the incandescent light bulb, he took out a total of 1093 patents that both he and his staff brought to life. Some of Thomas Edison's inventions included:

- The phonograph, the very first machine that could capture and play back sound.

- The stencil-pen, a writing instrument powered by electricity and that is thought to be the predecessor to the tattoo gun.

- The carbon transmitter, which improved the volume and clarity of voices on the telephone.

- He also helped improve existing inventions, such as the stock ticker and the automatic telegraph.

2. Thomas Edison's six children had a lot to live up to, and Thomas Alva Edison Jr. had a lot to live down.

Across two marriages , the first to Mary Stilwell from 1871 to her death in 1884 and the second to Mina Miller in 1886, Edison had six children:

- Marion Estelle Edison (with Stilwell)

- Thomas Alva Edison Jr. (with Stilwell)

- William Leslie Edison (with Stilwell)

- Madeleine Edison (with Miller)

- Charles Edison (with Miller)

- Theodore Miller Edison (with Miller)

Edison attempted to instill a love of knowledge in each of his children, though his methods were not always kind. Admonishing daughter Madeline to answer homework questions at breakfast, Edison would touch her with a hot spoon on her hand if she answered too slowly or incorrectly.

This environment was apparently too hostile for one of his sons, Thomas Alva Edison Jr. , who dropped out of prep school at age 17 and was later chastised by the press for marketing dubious inventions like the Vitalizer, a piece of headgear that promised to make the wearer think faster. In 1904, the post office charged the Vitalizer's distributor with postal fraud. In order to prevent his son from further besmirching the family name, Edison began giving his son an allowance to keep him out of the spotlight.

3. Thomas Edison has a controversial association with an elephant named Topsy.

In the 1890s, Edison's direct current (DC) electrical power was vying for supremacy with Nikola Tesla's alternating current (AC) power. During this time, Edison and his supporters argued that AC was dangerous and tried to prove it by electrocuting animals. Of course, DC could kill just as easily. In 1903, electricity was famously used to kill Topsy, a circus elephant who had been marked for execution after she had killed a spectator. Though Edison is often mentioned in conjunction with the animal's execution, a 2017 Smithsonian article claims he did not witness it and may not have even heard of the story. However, a company working under the Edison Manufacturing banner was on hand to film the sad display, and people erroneously assumed the inventor had something to do with it. But by that point, the Tesla vs. Edison war was long over, and the more versatile AC power had won out.

4. Thomas Edison's Menlo Park property was a site of both triumph and tragedy.

When Edison was 28, he purchased a housing development in Raritan Township, New Jersey, and used the property as the site for his house and laboratory. It was there that, over the course of a decade, Edison and his staff invented more than 400 items. But the site was also home to tragedy. Edison's first wife, Mary, died of a morphine overdose in 1884 while trying to manage pain following the birth of their third child. Edison distanced himself from the area after that, destroying his house and facilities. The township was renamed Edison, New Jersey, in 1954. Today, it's the site of the Thomas Edison Center at Menlo Park, where visitors can get a glimpse of Edison's many inventions.

5. Some of Thomas Edison's siblings suffered unfortunate fates.

Thomas Edison had six siblings:

- William Pitt

- Harriet Ann ("Tannie")

When Edison was born in Milan, Ohio in 1847, he was the seventh and last child of parents Samuel Edison and Nancy Elliott Edison. Unfortunately, Edison didn't get a chance to know all of his siblings. Of his parents' seven children (Marion, William Pitt, Harriet Ann, Carlile, Samuel, Eliza, and Thomas) only four survived . Carlile, Samuel, and Eliza all died in childhood.

6. The Civil War inspired Thomas Edison's interest in invention.

When Thomas Edison was 7 years old, his family relocated to Port Huron, Michigan. Edison, who went by "Al," short for his middle name of Alva, was a disinterested school student and was eventually taught at home by his mother. At 15, he decided to travel across the country, sending and receiving messages over the telegraph for trains and the Union Army during the Civil War. The experience inspired his lifelong passion for invention.

7. Thomas Edison credited a longtime physical ailment as a key factor in his success.

Beginning in childhood, Edison suffered from profound hearing loss. No one is exactly sure what caused it, though Edison himself blamed it on a train conductor who once picked him up by the ears, causing damage. More likely, ear infections affected his ability to hear. However it happened, Edison said his hearing loss led to his incredible ability to concentrate and to deeply focus on whatever task was at hand.

8. Thomas Edison's final breaths before death became a museum piece.

During his career, Edison became friends with automobile pioneer Henry Ford. As Edison's health began to deteriorate and he was eventually relegated to a wheelchair, Ford bought one for himself so that they could race. When, in 1931, it seemed as if Edison's final days were numbered, some believe that Ford asked Edison's son Charles to try and capture his father's last breath in a test tube. While Charles did not do that, Edison's room did contain test tubes during his final moments that were close to his bed. Charles asked that they be sealed with paraffin and he gave one to Ford. Labeled "Edison's Last Breath?" it's currently located at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Most Notable Thomas Edison Inventions:

- Incandescent light bulb

- Electric vote recorder

- Carbon telephone transmitter

- Alkaline battery

- Electric pen

Famous Thomas Edison Quotes:

- "Genius is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration."

- "The value of an idea lies in the using of it."

- "I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work."

Biography Online

Thomas Edison Biography

Thomas Edison (1847 – 1931) was an American inventor and businessman who developed and made commercially available – many key inventions of modern life. His Edison Electric company was a pioneering company for delivering DC electricity directly into people’s homes. He filed over 1,000 patents for a variety of different inventions. Crucially, he used mass-produced techniques to make his inventions available at low cost to households across America. His most important inventions include the electric light bulb, the phonograph, the motion picture camera, an electric car and the electric power station.

“None of my inventions came by accident. I see a worthwhile need to be met and I make trial after trial until it comes. What it boils down to is one per cent inspiration and ninety-nine per cent perspiration.”

– Thomas Edison, interview 1929

Short Biography Thomas Edison

As a youngster, he tried various odd jobs to earn a living. This including selling candy, vegetables and newspapers. He had a talent for business, and he successfully printed the Grand Trunk Herald along with his other newspapers. This included selling photos of his hero, Abraham Lincoln . He was able to spend his extra income on a growing chemistry set.

Unfortunately, from an early age, Edison developed a severe deafness, which ultimately left him almost 90% deaf. He would later refuse any medical treatment, saying it would be too difficult to retrain his thinking process. He seemed to take his deafness in his stride, and never saw it as a disability.

From childhood, Edison loved to experiment, especially with chemicals. However, these experiments often got Edison into difficulties. A chemistry experiment once exploded on a train, and when working on a night shift at Western Union, his lead-acid battery leaked sulphuric acid through the floor onto his boss’ desk. Edison was fired the next day.

However Edison was undimmed and, despite scrapping by in impoverished conditions for the next few years, he was able to spend most of his time working on inventions. He received his first patent on June 1, 1869, for the stock ticker. This would later earn him a considerable sum.

In the 1870s, he sold the rights to the quadruplex telegraph to Western Union for $10,000. This gave him the financial backing to establish a proper research laboratory and extend his experiments and innovations. Edison once described his invention methods as involving a lot of hard work and repeated trial and error until a method was successful.

“During all those years of experimentation and research, I never once made a discovery. All my work was deductive, and the results I achieved were those of invention, pure and simple. I would construct a theory and work on its lines until I found it was untenable. … I speak without exaggeration when I say that I have constructed 3,000 different theories in connection with the electric light, each one of them reasonable and apparently likely to be true. Yet only in two cases did my experiments prove the truth of my theory.”

– “Talks with Edison” by G.P Lathrop in Harper’s magazine, Vol. 80 (Feb. 1890), p. 425

By 1877, he had developed the phonograph (an early form of the gramophone player) This received widespread interest, and people were astonished at one of the first audio recording devices. This unique invention earned Edison the nickname ‘The Wizard of Menlo Park ‘ Edison’s device would later be improved upon by others, but he made a big step in creating the first recording device.

With William Joseph Hammer, Edison started producing the electric light bulb, and it was a great commercial success. Edison’s great advance was to use a carbonised bamboo filament that could last over 1,000 hours. In 1878, he formed the Edison Electric light Company to profit from this invention. Edison successfully predicted that he could make electric light so cheap, it would soon come universal. To capitalise on the success of the electric light bulb, he also worked on electricity distribution. His first power station was able to distribute DC current to 59 customers in lower Manhattan.

Edison’s studios now took up two blocks, and it was able to stock a huge range of natural resources, meaning that almost anything and everything could be used in trying to improve designs. This was a big factor in enabling Edison to be so successful in this era of innovation.

During the fledgeling years of electricity generation, Edison became involved in a battle between his DC current system and the AC (alternative current) system favoured by George Westinghouse (and developed by Nikola Tesla , who worked for Edison for two years before leaving in a pay dispute.)

This became known as the ‘current war’ and both sides were desperate to show the superiority of their system. The Edison company even, on occasion, electrocuted animals to show how dangerous the rival AC current was.

During World War One, Edison was asked to serve as a naval consultant, but Edison only wanted to work on defensive weapons. He was proud that he made no invention that could be used to kill. He maintained a strong belief in non-violence.

“Nonviolence leads to the highest ethics, which is the goal of all evolution. Until we stop harming all other living beings, we are still savages.”

Edison was also a great admirer of the Enlightenment thinker Thomas Paine . He wrote a book praising Paine in 1925; he also shared similar religious beliefs to Thomas Paine – no particular religion, but belief in a Supreme Being.

Edison made many important inventions and development in media. These included the Kinetoscope (or peephole view), the first motion pictures and improved photographic paper.

After the death of his first wife, Mary Stilwell in 1884, Edison left Menlo Park and moved to West Orange, New Jersey. In 1886, he remarried Mina Miller. In West Orange, he became friends with the industrial magnate, Henry Ford and was an active participant in the Civitan club – which involved doing things for the local community. His pace of invention slowed down in these final years, but he still kept busy, such as trying to find a domestic source of natural rubber. He was also involved in the first electric train to depart from Hoboken in 1930.

Throughout his life, he took an active interest in finding the optimal diet and believed a good diet could play a large role in improving health. In 1903, he was quoted as saying:

“The doctor of the future will give no medicine, but will instruct his patient in the care of the human frame, in diet and in the cause and prevention of disease.”

He had six children, three from each marriage. Edison died of diabetes on October 18, 1931.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Thomas Edison” , Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net Published 17th July 2013. Last updated 5 March 2018.

Quotes by Thomas Edison

“Through all the years of experimenting and research, I never once made a discovery. I start where the last man left off. … All my work was deductive, and the results I achieved were those of invention pure and simple.”

As quoted in Makers of the Modern World: The Lives of Ninety-two Writers, Artists, Scientists, Statesmen, Inventors, Philosophers, Composers, and Other Creators who Formed the Pattern of Our Century (1955) by Louis Untermeyer, p. 227

“We don’t know a millionth of one percent about anything.”

As quoted in Golden Book (April 1931), according to Stevenson’s Book of Quotations (Cassell 3rd edition 1938) by Burton Egbert Stevenson

“If we did all the things we are capable of doing, we would literally astound ourselves.”

As quoted in Motivating Humans: Goals, Emotions, and Personal Agency Beliefs (1992) by Martin E. Ford, p. 17

“To invent, you need a good imagination and a pile of junk.”

As quoted in Behavior-Based Robotics (1998) by Ronald C. Arkin. p. 8

“Just because something doesn’t do what you planned it to do doesn’t mean it’s useless.”

“Everyone steals in commerce and industry. I’ve stolen a lot, myself. But I know how to steal! They don’t know how to steal!”

As quoted in Tesla: The Modern Sorcerer (1999) by Daniel Blair Stewart, p. 411

“I consider Paine our greatest political thinker. As we have not advanced, and perhaps never shall advance, beyond the Declaration and Constitution, so Paine has had no successors who extended his principles.”

The Philosophy of Paine (1925)

“In ‘Common Sense’ Paine flared forth with a document so powerful that the Revolution became inevitable. Washington recognized the difference, and in his calm way said that matters never could be the same again..”

The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World

The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World at Amazon

Related pages

- Top 10 Inventors

- Greatest modern inventions

- Americans who changed the world

- 100 most influential people

External links

- Thomas Edison homepage

Thomas Edison

- Occupation: Businessman and Inventor

- Born: February 11, 1847 in Milan, Ohio

- Died: October 18, 1931 in West Orange, New Jersey

- Best known for: Inventing many useful items including the phonograph and a practical light bulb

- His middle name was Alva and his family called him Al.

- His first two kids had the nicknames Dot and Dash.

- He set up his first lab in his parent's basement at the age of 10.

- He was partially deaf.

- His first invention was an electric vote recorder.

- His 1093 patents are the most on record.

- He said the words to "Mary had a little lamb" as the first recorded voice on the phonograph.

- Listen to a recorded reading of this page:

Most realized that, even though he was far from being a perfect human being - and may not have really had the always amiable and avuncular personality that was so often ascribed to him by myth makers -Thomas Edison was an essentially good man with a powerful mission.

Driven by a superhuman desire to fulfill the promise of objective persistent research and create things to serve and uplift all of mankind, no one did more to help realize our founders dream of creating a brand new country that - at its best - would be seen by everyone as "a shining new city upon a hill, whose light would be going out to the world...."

Because of the peculiar voids that Edison sometime evinced in areas such as cognition, speech, grammar, etc., a number of medical authorities have argued that he may have been plagued by a fundamental learning disability that went well beyond mere deafness.... A few of have conjectured that this mysterious ailment - along with his lack of a formal education - may account for why he always seemed to "think so differently" compared to others of his time: "Always tenaciously clinging to those unique methods of analysis and experimentation with which he alone alwaya seemed to feel so comfortable...." Whatever the impetus for his unique personality and traits, his incredible ability to come up with a meaningful new patent every two weeks throughout his working career "added more to the collective wealth of the world - and had more impact upon shaping modern civilization - than the accomplishments of any figure since Gutenberg...." Accordingly, most serious science and technology historians grant that he was indeed "The most influential figure of our millennium."

Notes: In 1929, Edison's close friend, Henry Ford, completed the task of moving Edison's original Menlo Park laboratory to the Greenfield Village museum in Dearborn, Mich. In 1962 his existing laboratory and home in West Orange, N.J. were designated as National Historic Sites.

Copyright © Gerald Beals June, 1999. All rights registered and reserved. Please Note: Absolutely no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form - or stored by any means in a database or retrieval system - without the prior written and express permission of the author.

Please note : Infringements will be (in fact one is currently being) prosecuted to the full extent of the law.

gerrybeals@ verizon.net

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Professionals & Academics

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $34.65 $ 34 . 65 FREE delivery Monday, May 13 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: EarthPositive

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $6.63 $ 6 . 63 FREE delivery May 10 - 16 Ships from: ThriftBooks-Phoenix Sold by: ThriftBooks-Phoenix

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

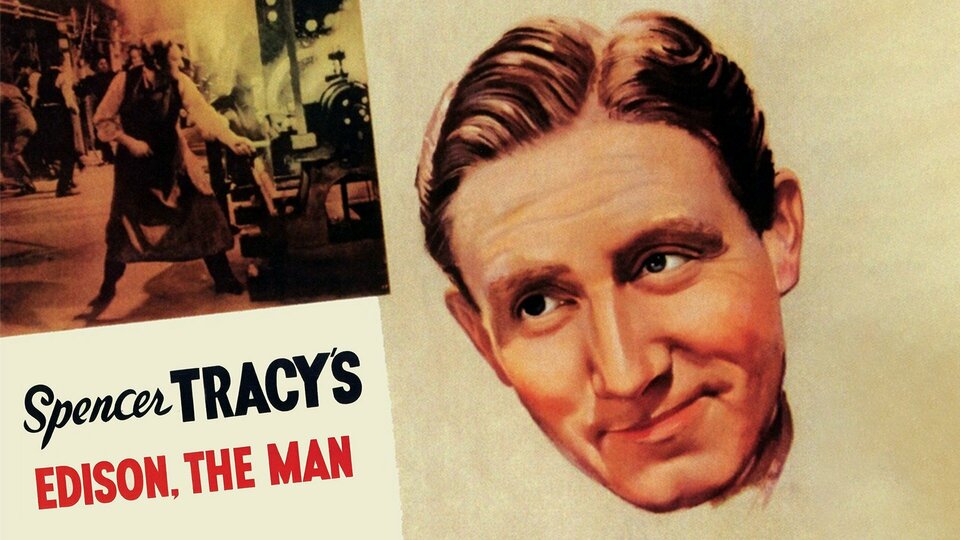

Edison: A Biography 1st Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 0471548065

- ISBN-13 978-0471548065

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Wiley

- Publication date February 11, 1992

- Language English

- Dimensions 6.12 x 1.43 x 9 inches

- Print length 528 pages

- See all details

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

From the publisher, product details.

- Publisher : Wiley; 1st edition (February 11, 1992)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 528 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0471548065

- ISBN-13 : 978-0471548065

- Item Weight : 1.6 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.12 x 1.43 x 9 inches

- #2,723 in Scientist Biographies

- #26,685 in Engineering (Books)

- #51,010 in Unknown

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- The Midwest

- Reading Lists

The 10 Best Books on Thomas Edison

Essential books on thomas edison.

There are countless books on Thomas Edison, and it comes with good reason, as one of America’s foremost businessmen, his inventions, which include the phonograph, the motion picture camera, and early versions of the electric light bulb, have had a widespread impact on the modern industrialized world.

“One might think that the money value of an invention constitutes its reward to the man who loves his work. But speaking for myself, I can honestly say this is not so…I continue to find my greatest pleasure, and so my reward, in the work that precedes what the world calls success,” he remarked.

In order to get to the bottom of what inspired one of history’s most consequential figures to the heights of societal contribution, we’ve compiled a list of the 10 best books on Thomas Edison.

Edison by Edmund Morris