Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on January 27, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about action research.

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasizes that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

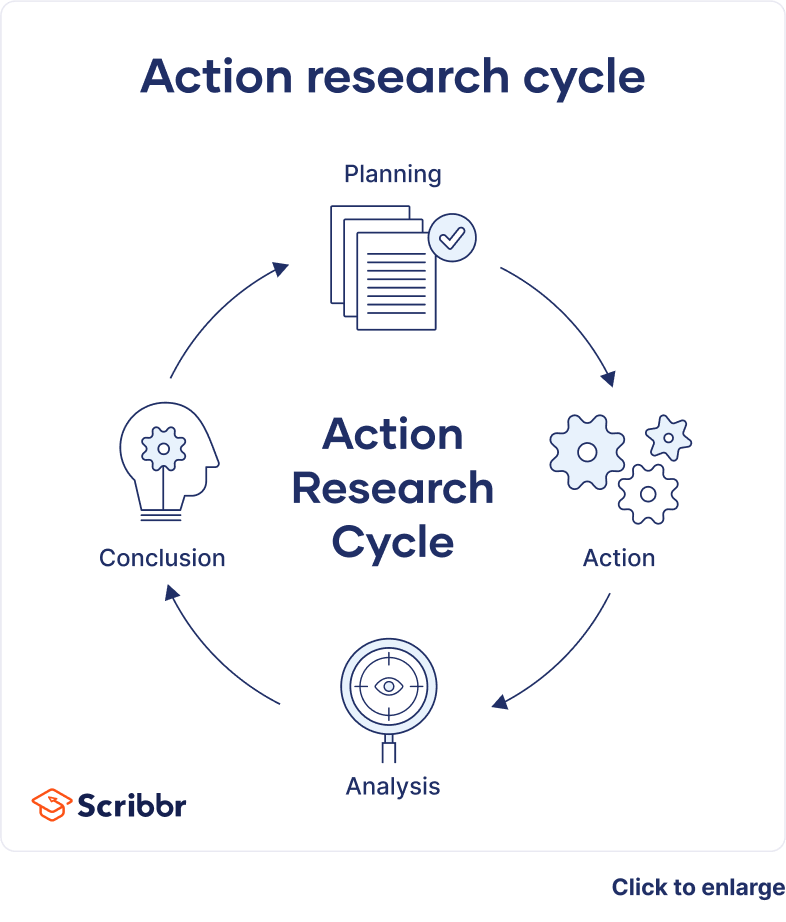

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualized like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualize systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyze existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilized, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardized test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mold their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalizability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th edition). Routledge.

Naughton, G. M. (2001). Action research (1st edition). Routledge.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, primary research | definition, types, & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Action Research vs. Case Study

What's the difference.

Action research and case study are both research methodologies used in social sciences to investigate and understand complex phenomena. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. Action research is a collaborative and participatory approach that involves researchers and practitioners working together to identify and solve practical problems in real-world settings. It aims to bring about positive change and improvement in the context being studied. On the other hand, case study is an in-depth and detailed examination of a particular individual, group, or situation. It focuses on understanding the unique characteristics and dynamics of the case being studied and often involves extensive data collection and analysis. While action research emphasizes practical application and problem-solving, case study emphasizes detailed exploration and understanding of a specific case.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Action research and case study are two widely used research methodologies in various fields. While both approaches aim to gain insights and understanding, they differ in their focus, design, and implementation. This article will explore the attributes of action research and case study, highlighting their similarities and differences.

Action Research

Action research is a participatory approach that involves collaboration between researchers and practitioners to address real-world problems. It emphasizes the active involvement of stakeholders in the research process, aiming to bring about practical change and improvement. Action research typically follows a cyclical process, consisting of planning, action, observation, and reflection.

One of the key attributes of action research is its focus on generating knowledge that is directly applicable to the context in which it is conducted. It aims to bridge the gap between theory and practice by actively involving practitioners in the research process. This participatory nature allows for a deeper understanding of the complexities and nuances of the problem being investigated.

Action research often involves multiple iterations, with each cycle building upon the insights gained from the previous one. This iterative approach allows for continuous learning and adaptation, enabling researchers to refine their interventions and strategies based on the feedback received. It also promotes a sense of ownership and empowerment among the participants, as they actively contribute to the research process.

Furthermore, action research is characterized by its emphasis on collaboration and co-learning. It encourages the exchange of ideas and knowledge between researchers and practitioners, fostering a sense of shared responsibility and collective action. This collaborative approach not only enhances the quality of the research but also increases the likelihood of successful implementation of the findings.

In summary, action research is a participatory and iterative approach that aims to generate practical knowledge through collaboration between researchers and practitioners. It focuses on addressing real-world problems and promoting positive change within specific contexts.

Case study, on the other hand, is an in-depth investigation of a particular phenomenon, event, or individual. It involves the detailed examination of a specific case or cases to gain a comprehensive understanding of the subject under study. Case studies can be conducted using various research methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis.

One of the key attributes of case study research is its ability to provide rich and detailed insights into complex phenomena. By focusing on a specific case, researchers can delve deep into the intricacies and unique aspects of the subject, uncovering valuable information that may not be easily captured through other research methods.

Case studies are often used to explore and understand real-life situations in their natural settings. They allow researchers to examine the context and dynamics surrounding the case, providing a holistic view of the phenomenon under investigation. This contextual understanding is crucial for gaining a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the subject.

Furthermore, case studies are particularly useful when the boundaries between the phenomenon and its context are not clearly defined. They allow for the exploration of complex and multifaceted issues, enabling researchers to capture the interplay of various factors and variables. This holistic approach enhances the validity and reliability of the findings.

Moreover, case studies can be exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory in nature, depending on the research questions and objectives. They can be used to generate hypotheses, provide detailed descriptions, or test theoretical frameworks. This versatility makes case study research applicable in various fields, including psychology, sociology, business, and education.

In summary, case study research is an in-depth investigation of a specific phenomenon, providing rich and detailed insights into complex situations. It focuses on understanding the context and dynamics surrounding the case, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of multifaceted issues.

Similarities

While action research and case study differ in their focus and design, they also share some common attributes. Both approaches aim to gain insights and understanding, albeit through different means. They both involve the collection and analysis of data to inform decision-making and improve practice.

Furthermore, both action research and case study can be conducted in naturalistic settings, allowing for the examination of real-life situations. They both emphasize the importance of context and seek to understand the complexities and nuances of the phenomena under investigation.

Moreover, both methodologies can involve multiple data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. They both require careful planning and design to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

Additionally, both action research and case study can contribute to theory development. While action research focuses on generating practical knowledge, it can also inform and contribute to theoretical frameworks. Similarly, case studies can provide empirical evidence that can be used to refine and expand existing theories.

In summary, action research and case study share common attributes, including their aim to gain insights and understanding, their focus on real-life situations, their emphasis on context, their use of multiple data collection methods, and their potential contribution to theory development.

Action research and case study are two distinct research methodologies that offer unique approaches to gaining insights and understanding. Action research emphasizes collaboration, participation, and practical change, while case study focuses on in-depth investigation and contextual understanding. Despite their differences, both approaches contribute to knowledge generation and have the potential to inform theory and practice. Researchers should carefully consider the nature of their research questions and objectives to determine which approach is most suitable for their study.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, an action research case study: digital equity and educational inclusion during an emergent covid-19 divide.

Journal for Multicultural Education

ISSN : 2053-535X

Article publication date: 22 January 2021

Issue publication date: 4 June 2021

This paper aims to share responses from current literature, a small case study about perceptions and practices of the school of education faculty toward multicultural and educational issues concerning the rapid rise in online environments during coronavirus (COVID-19) experiences and just-in-time strategies for addressing digital equity and educational inclusion in K-16 online educational settings.

Design/methodology/approach

This is a conceptual paper that emerged from an action research case study. The study included four faculty in an urban school of education. The faculty participants were asked to provide examples of educational inclusion strategies used during transitioning their courses and advising to online environments in a Research I university. Faculty included one educational leadership, one sports management, one special education and one teacher education professor. Central issues explored practices related to language, technology access, curriculum design and technological competencies and assessment. A driving question was: How do institutions, schools or educators provide learning opportunities to support digital equity and inclusive education practice to maintain and strengthen relationships and core practices of multicultural education during a time of physical distancing during COVID-19? And what are the experiences, barriers, successes?

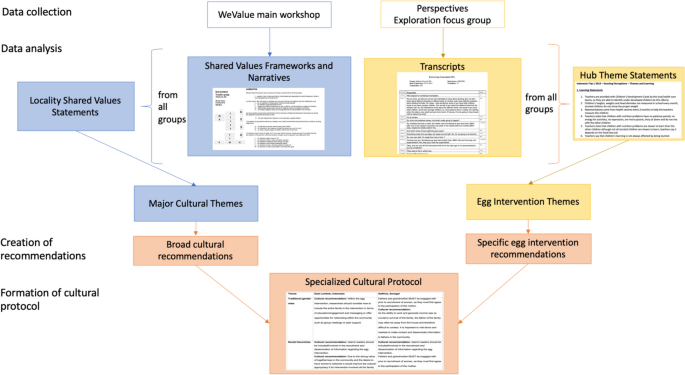

Research-based transformative knowledge, real situations and practical resources for considering inclusive education curriculum concepts were found that are connecting educators, teachers, learners and communities during this time of crisis.

Research limitations/implications

Methodological limitations that influenced the research design include conducting research in a totally virtual environment, small sample size, lack of diversity in curriculum content and one research site. The data collection was limited to written responses from the faculty participants. This action research study took place in a time frame limited by COVID-19 conditions during a four-month period.

Practical implications

In theory and practice, this new online movement suggests learners, teachers, educators and leaders are gaining experience and knowledge about resources and strategies for using new technologies, assessments and flexible curriculum as powerful tools for building language, curriculum and social-cultural communication bonds across generations and including special needs populations. Such new and emerging strategies could be used to bridge gaps in a time of distancing to support inclusive and equitable learning environments in education to minimize the effects of an emergent COVID-19 digital divide. Social learning culture as constructed, performed and captured in patterns of cooperation among faculties shows the world becoming more open and less restricted by borders. In conclusion, an emerging new conceptual framework is presented in Figure 2 to support action planning to bridge the digital equity access and learning gaps created by COVID-19.

Social implications

It is in times of strife and difficulty that problems and issues become exacerbated. While some educators easily adapted and took on the challenges of online learning, others needed time for learning and mourning (literally and figuratively). The issues of equity and access have become even more apparent as this paper takes inventory of intersections between multicultural education, special education, sports education and K-16 education overall. This is an excellent time to reflect on how education can address the cultural, economic and social barriers that impact student learning globally for all learners.

Originality/value

The brief collective case study reports educational experiences during a time of crisis that stimulates creative and innovative approaches to creating inclusive and equitable online learning environments to address diverse learning needs. The various and often contrasting educator responses from faculty facing digital and educational challenges present ideas that might be applicable in the global learning environment beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Online learning

- New technologies

- Transformative knowledge

Acknowledgements

World Council on Curriculum and Instruction -WCCI (UNESCO-NGO) Newsletter, Winter 2020 Content cited by Toh Swee-Hin (S.H.Toh) President, WCCI. Professor Emeritus, University of Alberta. Laureate, UNESCO Prize for Peace Education (2000).

Pittman, J. , Severino, L. , DeCarlo-Tecce, M.J. and Kiosoglous, C. (2021), "An action research case study: digital equity and educational inclusion during an emergent COVID-19 divide", Journal for Multicultural Education , Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 68-84. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-09-2020-0099

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Qualitative study design: Action research

- Qualitative study design

- Phenomenology

- Grounded theory

- Ethnography

- Narrative inquiry

- Action research

- Case Studies

- Field research

- Focus groups

- Observation

- Surveys & questionnaires

- Study Designs Home

Action research / Participatory Action Research

These methods focus on the emancipation, collaboration and empowerment of the participants. This methodology is appropriate for collaborative research with groups, especially marginalised groups, where there is more flexibility in how the research is conducted and considers feedback from the participants.

Has three primary characteristics:

Action oriented, participants are actively involved in the research.

involvement by participants in the research, collaborative process between participant and researcher - empowerment of participants. The participants have more of a say in what is being researched and how they want the research to be conducted.

cycle is iterative so that it is flexible and responsive to a changing situation.

- Questionnaires

- Oral recordings

- Focus groups,

- Photovoice (use of images or video to capture the local environment / community and to share with others)

- Informal conversations

Produces knowledge from marginalised people's point of view and can lead to more personalised interventions.

Provides a voice for people to speak about their issues and the ability to improve their own lives. People take an active role in implementing any actions arising from the research.

Transforms social reality by linking theory and practice.

Limitations

Open ended questions are mainly used, and these can be misinterpreted by researcher – data needs to be cross-checked with other sources.

Data ownership between researcher and research participants needs to be negotiated and clearly stated from the beginning of the project.

Ethical considerations with privacy and confidentiality.

This method is not considered scientific as it is more fluid in its gathering of information and is considered an unconventional research method – thus it may not attract much funding.

Example questions

- What is the cultural significance of yarning amongst Aboriginal people?

Macro Question:

- “What would it take to improve the stability of young people’s living situations?”

Micro Questions:

- “What can we do to better engage with accommodation service providers?”

- “What can we do to improve the service knowledge of young people?”

- “What can we do to measure stability outcomes for our clients?”

(Department of Social Services)

Example studies

- Miller, A., Massey, P. D., Judd, J., Kelly, J., Durrheim, D. N., Clough, A. R., . . . Saggers, S. (2015). Using a participatory action research framework to listen to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia about pandemic influenza. Rural and Remote Health , 15(3), 2923-2923.

- Spinney, A. (2013). Safe from the Start? An Action Research Project on Early Intervention Materials for Children Affected by Domestic and Family Violence. Children & Society, 27(5), 397-405. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00454.x

- Department of Social Services. (2019). On PAR - Using participatory action research to improve early intervention.

- Liamputtong, P. (2013). Qualitative research methods (4th ed.). South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Mills, J., & Birks, M. (2014). Qualitative Methodology: A Practical Guide. Retrieved from https://methods.sagepub.com/book/qualitative-methodology-a-practical-guide doi:10.4135/9781473920163

- << Previous: Narrative inquiry

- Next: Case Studies >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 11:12 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/qualitative-study-designs

Home » Education » Difference Between Action Research and Case Study

Difference Between Action Research and Case Study

Main difference – action research vs case study.

Research is the careful study of a given field or problem in order to discover new facts or principles. Action research and case study are two types of research, which are mainly used in the field of social sciences and humanities. The main difference between action research and case study is their purpose; an action research study aims to solve an immediate problem whereas a case study aims to provide an in-depth analysis of a situation or case over a long period of time.

1. What is Action Research? – Definition, Features, Purpose, Process

2. What is Case Study? – Definition, Features, Purpose, Process

What is Action Research

Action research is a type of a research study that is initiated to solve an immediate problem. It may involve a variety of analytical, investigative and evaluative research methods designed to diagnose and solve problems. It has been defined as “a disciplined process of inquiry conducted by and for those taking the action. The primary reason for engaging in action research is to assist the “actor” in improving and/or refining his or her actions” (Sagor, 2000). This type of research is typically used in the field of education. Action research studies are generally conductors by educators, who also act as participants.

Here, an individual researcher or a group of researchers identify a problem, examine its causes and try to arrive at a solution to the problem. The action research process is as follows.

Action Research Process

- Identify a problem to research

- Clarify theories

- Identify research questions

- Collect data on the problem

- Organise, analyse, and interpret the data

- Create a plan to address the problem

- Implement the above-mentioned plan

- Evaluate the results of the actions taken

The above process will keep repeating. Action research is also known as cycle of inquiry or cycle of action since it follows a specific process that is repeated over time.

What is a Case Study

A case study is basically an in-depth examination of a particular event, situation or an individual. It is a type of research that is designed to explore and understand complex issues; however, it involves detailed contextual analysis of only a limited number of events or situations. It has been defined as “an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context; when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evidence are used.” (Yin, 1984)

Case studies are used in a variety of fields, but fields like sociology and education seem to use them the most. They can be used to probe into community-based problems such as illiteracy, unemployment, poverty, and drug addiction.

Case studies involve both quantitative and qualitative data and allow the researchers to see beyond statistical results and understand human conditions. Furthermore, case studies can be classified into three categories, known as exploratory, descriptive and explanatory case studies.

However, case studies are also criticised since the study of a limited number of events or cases cannot easily establish generality or reliability of the findings. The process of a case study is generally as follows:

Case Study Process

- Identifying and defining the research questions

- Selecting the cases and deciding techniques for data collection and analysis

- Collecting data in the field

- Evaluating and analysing the data

- Preparing the report

Action Research : Action research is a type of a research study that is initiated to solve an immediate problem.

Case Study : Case study is an in-depth analysis of a particular event or case over a long period of time.

Action Research : Action research involves solving a problem.

Case Study : Case studies involve observing and analysing a situation.

Action Research : Action research studies are mainly used in the field of education.

Case Study : Case studies are used in many fields; they can be specially used with community problems such as unemployment, poverty, etc.

Action Research : Action research always involve providing a solution to a problem.

Case Study : Case studies do not provide a solution to a problem.

Participants

Action Research : Researchers can also act as participants of the research.

Case Study : Researchers generally don’t take part in the research study.

Zainal, Zaidah. Case study as a research method . N.p.: n.p., 7 June 2007. PDF.

Soy, Susan K. (1997). The case study as a research method . Unpublished paper, University of Texas at Austin.

Sagor, Richard. Guiding school improvement with action research . Ascd, 2000.

Image Courtesy: Pixabay

About the Author: Hasa

Hasanthi is a seasoned content writer and editor with over 8 years of experience. Armed with a BA degree in English and a knack for digital marketing, she explores her passions for literature, history, culture, and food through her engaging and informative writing.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

The case study approach

Sarah crowe.

1 Division of Primary Care, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Kathrin Cresswell

2 Centre for Population Health Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Ann Robertson

3 School of Health in Social Science, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Anthony Avery

Aziz sheikh.

The case study approach allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The value of the case study approach is well recognised in the fields of business, law and policy, but somewhat less so in health services research. Based on our experiences of conducting several health-related case studies, we reflect on the different types of case study design, the specific research questions this approach can help answer, the data sources that tend to be used, and the particular advantages and disadvantages of employing this methodological approach. The paper concludes with key pointers to aid those designing and appraising proposals for conducting case study research, and a checklist to help readers assess the quality of case study reports.

Introduction

The case study approach is particularly useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context. Our aim in writing this piece is to provide insights into when to consider employing this approach and an overview of key methodological considerations in relation to the design, planning, analysis, interpretation and reporting of case studies.

The illustrative 'grand round', 'case report' and 'case series' have a long tradition in clinical practice and research. Presenting detailed critiques, typically of one or more patients, aims to provide insights into aspects of the clinical case and, in doing so, illustrate broader lessons that may be learnt. In research, the conceptually-related case study approach can be used, for example, to describe in detail a patient's episode of care, explore professional attitudes to and experiences of a new policy initiative or service development or more generally to 'investigate contemporary phenomena within its real-life context' [ 1 ]. Based on our experiences of conducting a range of case studies, we reflect on when to consider using this approach, discuss the key steps involved and illustrate, with examples, some of the practical challenges of attaining an in-depth understanding of a 'case' as an integrated whole. In keeping with previously published work, we acknowledge the importance of theory to underpin the design, selection, conduct and interpretation of case studies[ 2 ]. In so doing, we make passing reference to the different epistemological approaches used in case study research by key theoreticians and methodologists in this field of enquiry.

This paper is structured around the following main questions: What is a case study? What are case studies used for? How are case studies conducted? What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided? We draw in particular on four of our own recently published examples of case studies (see Tables Tables1, 1 , ,2, 2 , ,3 3 and and4) 4 ) and those of others to illustrate our discussion[ 3 - 7 ].

Example of a case study investigating the reasons for differences in recruitment rates of minority ethnic people in asthma research[ 3 ]

Example of a case study investigating the process of planning and implementing a service in Primary Care Organisations[ 4 ]

Example of a case study investigating the introduction of the electronic health records[ 5 ]

Example of a case study investigating the formal and informal ways students learn about patient safety[ 6 ]

What is a case study?

A case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is an established research design that is used extensively in a wide variety of disciplines, particularly in the social sciences. A case study can be defined in a variety of ways (Table (Table5), 5 ), the central tenet being the need to explore an event or phenomenon in depth and in its natural context. It is for this reason sometimes referred to as a "naturalistic" design; this is in contrast to an "experimental" design (such as a randomised controlled trial) in which the investigator seeks to exert control over and manipulate the variable(s) of interest.

Definitions of a case study

Stake's work has been particularly influential in defining the case study approach to scientific enquiry. He has helpfully characterised three main types of case study: intrinsic , instrumental and collective [ 8 ]. An intrinsic case study is typically undertaken to learn about a unique phenomenon. The researcher should define the uniqueness of the phenomenon, which distinguishes it from all others. In contrast, the instrumental case study uses a particular case (some of which may be better than others) to gain a broader appreciation of an issue or phenomenon. The collective case study involves studying multiple cases simultaneously or sequentially in an attempt to generate a still broader appreciation of a particular issue.

These are however not necessarily mutually exclusive categories. In the first of our examples (Table (Table1), 1 ), we undertook an intrinsic case study to investigate the issue of recruitment of minority ethnic people into the specific context of asthma research studies, but it developed into a instrumental case study through seeking to understand the issue of recruitment of these marginalised populations more generally, generating a number of the findings that are potentially transferable to other disease contexts[ 3 ]. In contrast, the other three examples (see Tables Tables2, 2 , ,3 3 and and4) 4 ) employed collective case study designs to study the introduction of workforce reconfiguration in primary care, the implementation of electronic health records into hospitals, and to understand the ways in which healthcare students learn about patient safety considerations[ 4 - 6 ]. Although our study focusing on the introduction of General Practitioners with Specialist Interests (Table (Table2) 2 ) was explicitly collective in design (four contrasting primary care organisations were studied), is was also instrumental in that this particular professional group was studied as an exemplar of the more general phenomenon of workforce redesign[ 4 ].

What are case studies used for?

According to Yin, case studies can be used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur[ 1 ]. These can, for example, help to understand and explain causal links and pathways resulting from a new policy initiative or service development (see Tables Tables2 2 and and3, 3 , for example)[ 1 ]. In contrast to experimental designs, which seek to test a specific hypothesis through deliberately manipulating the environment (like, for example, in a randomised controlled trial giving a new drug to randomly selected individuals and then comparing outcomes with controls),[ 9 ] the case study approach lends itself well to capturing information on more explanatory ' how ', 'what' and ' why ' questions, such as ' how is the intervention being implemented and received on the ground?'. The case study approach can offer additional insights into what gaps exist in its delivery or why one implementation strategy might be chosen over another. This in turn can help develop or refine theory, as shown in our study of the teaching of patient safety in undergraduate curricula (Table (Table4 4 )[ 6 , 10 ]. Key questions to consider when selecting the most appropriate study design are whether it is desirable or indeed possible to undertake a formal experimental investigation in which individuals and/or organisations are allocated to an intervention or control arm? Or whether the wish is to obtain a more naturalistic understanding of an issue? The former is ideally studied using a controlled experimental design, whereas the latter is more appropriately studied using a case study design.

Case studies may be approached in different ways depending on the epistemological standpoint of the researcher, that is, whether they take a critical (questioning one's own and others' assumptions), interpretivist (trying to understand individual and shared social meanings) or positivist approach (orientating towards the criteria of natural sciences, such as focusing on generalisability considerations) (Table (Table6). 6 ). Whilst such a schema can be conceptually helpful, it may be appropriate to draw on more than one approach in any case study, particularly in the context of conducting health services research. Doolin has, for example, noted that in the context of undertaking interpretative case studies, researchers can usefully draw on a critical, reflective perspective which seeks to take into account the wider social and political environment that has shaped the case[ 11 ].

Example of epistemological approaches that may be used in case study research

How are case studies conducted?

Here, we focus on the main stages of research activity when planning and undertaking a case study; the crucial stages are: defining the case; selecting the case(s); collecting and analysing the data; interpreting data; and reporting the findings.

Defining the case

Carefully formulated research question(s), informed by the existing literature and a prior appreciation of the theoretical issues and setting(s), are all important in appropriately and succinctly defining the case[ 8 , 12 ]. Crucially, each case should have a pre-defined boundary which clarifies the nature and time period covered by the case study (i.e. its scope, beginning and end), the relevant social group, organisation or geographical area of interest to the investigator, the types of evidence to be collected, and the priorities for data collection and analysis (see Table Table7 7 )[ 1 ]. A theory driven approach to defining the case may help generate knowledge that is potentially transferable to a range of clinical contexts and behaviours; using theory is also likely to result in a more informed appreciation of, for example, how and why interventions have succeeded or failed[ 13 ].

Example of a checklist for rating a case study proposal[ 8 ]

For example, in our evaluation of the introduction of electronic health records in English hospitals (Table (Table3), 3 ), we defined our cases as the NHS Trusts that were receiving the new technology[ 5 ]. Our focus was on how the technology was being implemented. However, if the primary research interest had been on the social and organisational dimensions of implementation, we might have defined our case differently as a grouping of healthcare professionals (e.g. doctors and/or nurses). The precise beginning and end of the case may however prove difficult to define. Pursuing this same example, when does the process of implementation and adoption of an electronic health record system really begin or end? Such judgements will inevitably be influenced by a range of factors, including the research question, theory of interest, the scope and richness of the gathered data and the resources available to the research team.

Selecting the case(s)