How to Write Critical Reviews

When you are asked to write a critical review of a book or article, you will need to identify, summarize, and evaluate the ideas and information the author has presented. In other words, you will be examining another person’s thoughts on a topic from your point of view.

Your stand must go beyond your “gut reaction” to the work and be based on your knowledge (readings, lecture, experience) of the topic as well as on factors such as criteria stated in your assignment or discussed by you and your instructor.

Make your stand clear at the beginning of your review, in your evaluations of specific parts, and in your concluding commentary.

Remember that your goal should be to make a few key points about the book or article, not to discuss everything the author writes.

Understanding the Assignment

To write a good critical review, you will have to engage in the mental processes of analyzing (taking apart) the work–deciding what its major components are and determining how these parts (i.e., paragraphs, sections, or chapters) contribute to the work as a whole.

Analyzing the work will help you focus on how and why the author makes certain points and prevent you from merely summarizing what the author says. Assuming the role of an analytical reader will also help you to determine whether or not the author fulfills the stated purpose of the book or article and enhances your understanding or knowledge of a particular topic.

Be sure to read your assignment thoroughly before you read the article or book. Your instructor may have included specific guidelines for you to follow. Keeping these guidelines in mind as you read the article or book can really help you write your paper!

Also, note where the work connects with what you’ve studied in the course. You can make the most efficient use of your reading and notetaking time if you are an active reader; that is, keep relevant questions in mind and jot down page numbers as well as your responses to ideas that appear to be significant as you read.

Please note: The length of your introduction and overview, the number of points you choose to review, and the length of your conclusion should be proportionate to the page limit stated in your assignment and should reflect the complexity of the material being reviewed as well as the expectations of your reader.

Write the introduction

Below are a few guidelines to help you write the introduction to your critical review.

Introduce your review appropriately

Begin your review with an introduction appropriate to your assignment.

If your assignment asks you to review only one book and not to use outside sources, your introduction will focus on identifying the author, the title, the main topic or issue presented in the book, and the author’s purpose in writing the book.

If your assignment asks you to review the book as it relates to issues or themes discussed in the course, or to review two or more books on the same topic, your introduction must also encompass those expectations.

Explain relationships

For example, before you can review two books on a topic, you must explain to your reader in your introduction how they are related to one another.

Within this shared context (or under this “umbrella”) you can then review comparable aspects of both books, pointing out where the authors agree and differ.

In other words, the more complicated your assignment is, the more your introduction must accomplish.

Finally, the introduction to a book review is always the place for you to establish your position as the reviewer (your thesis about the author’s thesis).

As you write, consider the following questions:

- Is the book a memoir, a treatise, a collection of facts, an extended argument, etc.? Is the article a documentary, a write-up of primary research, a position paper, etc.?

- Who is the author? What does the preface or foreword tell you about the author’s purpose, background, and credentials? What is the author’s approach to the topic (as a journalist? a historian? a researcher?)?

- What is the main topic or problem addressed? How does the work relate to a discipline, to a profession, to a particular audience, or to other works on the topic?

- What is your critical evaluation of the work (your thesis)? Why have you taken that position? What criteria are you basing your position on?

Provide an overview

In your introduction, you will also want to provide an overview. An overview supplies your reader with certain general information not appropriate for including in the introduction but necessary to understanding the body of the review.

Generally, an overview describes your book’s division into chapters, sections, or points of discussion. An overview may also include background information about the topic, about your stand, or about the criteria you will use for evaluation.

The overview and the introduction work together to provide a comprehensive beginning for (a “springboard” into) your review.

- What are the author’s basic premises? What issues are raised, or what themes emerge? What situation (i.e., racism on college campuses) provides a basis for the author’s assertions?

- How informed is my reader? What background information is relevant to the entire book and should be placed here rather than in a body paragraph?

Write the body

The body is the center of your paper, where you draw out your main arguments. Below are some guidelines to help you write it.

Organize using a logical plan

Organize the body of your review according to a logical plan. Here are two options:

- First, summarize, in a series of paragraphs, those major points from the book that you plan to discuss; incorporating each major point into a topic sentence for a paragraph is an effective organizational strategy. Second, discuss and evaluate these points in a following group of paragraphs. (There are two dangers lurking in this pattern–you may allot too many paragraphs to summary and too few to evaluation, or you may re-summarize too many points from the book in your evaluation section.)

- Alternatively, you can summarize and evaluate the major points you have chosen from the book in a point-by-point schema. That means you will discuss and evaluate point one within the same paragraph (or in several if the point is significant and warrants extended discussion) before you summarize and evaluate point two, point three, etc., moving in a logical sequence from point to point to point. Here again, it is effective to use the topic sentence of each paragraph to identify the point from the book that you plan to summarize or evaluate.

Questions to keep in mind as you write

With either organizational pattern, consider the following questions:

- What are the author’s most important points? How do these relate to one another? (Make relationships clear by using transitions: “In contrast,” an equally strong argument,” “moreover,” “a final conclusion,” etc.).

- What types of evidence or information does the author present to support his or her points? Is this evidence convincing, controversial, factual, one-sided, etc.? (Consider the use of primary historical material, case studies, narratives, recent scientific findings, statistics.)

- Where does the author do a good job of conveying factual material as well as personal perspective? Where does the author fail to do so? If solutions to a problem are offered, are they believable, misguided, or promising?

- Which parts of the work (particular arguments, descriptions, chapters, etc.) are most effective and which parts are least effective? Why?

- Where (if at all) does the author convey personal prejudice, support illogical relationships, or present evidence out of its appropriate context?

Keep your opinions distinct and cite your sources

Remember, as you discuss the author’s major points, be sure to distinguish consistently between the author’s opinions and your own.

Keep the summary portions of your discussion concise, remembering that your task as a reviewer is to re-see the author’s work, not to re-tell it.

And, importantly, if you refer to ideas from other books and articles or from lecture and course materials, always document your sources, or else you might wander into the realm of plagiarism.

Include only that material which has relevance for your review and use direct quotations sparingly. The Writing Center has other handouts to help you paraphrase text and introduce quotations.

Write the conclusion

You will want to use the conclusion to state your overall critical evaluation.

You have already discussed the major points the author makes, examined how the author supports arguments, and evaluated the quality or effectiveness of specific aspects of the book or article.

Now you must make an evaluation of the work as a whole, determining such things as whether or not the author achieves the stated or implied purpose and if the work makes a significant contribution to an existing body of knowledge.

Consider the following questions:

- Is the work appropriately subjective or objective according to the author’s purpose?

- How well does the work maintain its stated or implied focus? Does the author present extraneous material? Does the author exclude or ignore relevant information?

- How well has the author achieved the overall purpose of the book or article? What contribution does the work make to an existing body of knowledge or to a specific group of readers? Can you justify the use of this work in a particular course?

- What is the most important final comment you wish to make about the book or article? Do you have any suggestions for the direction of future research in the area? What has reading this work done for you or demonstrated to you?

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Open access

- Published: 08 October 2021

Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application

- Micah D. J. Peters 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Casey Marnie 1 ,

- Heather Colquhoun 4 , 5 ,

- Chantelle M. Garritty 6 ,

- Susanne Hempel 7 ,

- Tanya Horsley 8 ,

- Etienne V. Langlois 9 ,

- Erin Lillie 10 ,

- Kelly K. O’Brien 5 , 11 , 12 ,

- Ӧzge Tunçalp 13 ,

- Michael G. Wilson 14 , 15 , 16 ,

- Wasifa Zarin 17 &

- Andrea C. Tricco ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4114-8971 17 , 18 , 19

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 263 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

36k Accesses

176 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis with a growing suite of methodological guidance and resources to assist review authors with their planning, conduct and reporting. The latest guidance for scoping reviews includes the JBI methodology and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—Extension for Scoping Reviews. This paper provides readers with a brief update regarding ongoing work to enhance and improve the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews as well as information regarding the future steps in scoping review methods development. The purpose of this paper is to provide readers with a concise source of information regarding the difference between scoping reviews and other review types, the reasons for undertaking scoping reviews, and an update on methodological guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews.

Despite available guidance, some publications use the term ‘scoping review’ without clear consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardised use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the review’s objective(s) and question(s) are critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews.

Rigourous, high-quality scoping reviews should clearly follow up to date methodological guidance and reporting criteria. Stakeholder engagement is one area where further work could occur to enhance integration of consultation with the results of evidence syntheses and to support effective knowledge translation. Scoping review methodology is evolving as a policy and decision-making tool. Ensuring the integrity of scoping reviews by adherence to up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well-informed decision-making.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Given the readily increasing access to evidence and data, methods of identifying, charting and reporting on information must be driven by new, user-friendly approaches. Since 2005, when the first framework for scoping reviews was published, several more detailed approaches (both methodological guidance and a reporting guideline) have been developed. Scoping reviews are an increasingly common approach to evidence synthesis which is very popular amongst end users [ 1 ]. Indeed, one scoping review of scoping reviews found that 53% (262/494) of scoping reviews had government authorities and policymakers as their target end-user audience [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews can provide end users with important insights into the characteristics of a body of evidence, the ways, concepts or terms have been used, and how a topic has been reported upon. Scoping reviews can provide overviews of either broad or specific research and policy fields, underpin research and policy agendas, highlight knowledge gaps and identify areas for subsequent evidence syntheses [ 3 ].

Despite or even potentially because of the range of different approaches to conducting and reporting scoping reviews that have emerged since Arksey and O’Malley’s first framework in 2005, it appears that lack of consistency in use of terminology, conduct and reporting persist [ 2 , 4 ]. There are many examples where manuscripts are titled ‘a scoping review’ without citing or appearing to follow any particular approach [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This is similar to how many reviews appear to misleadingly include ‘systematic’ in the title or purport to have adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement without doing so. Despite the publication of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and other recent guidance [ 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ], many scoping reviews continue to be conducted and published without apparent (i.e. cited) consideration of these tools or only cursory reference to Arksey and O’Malley’s original framework. We can only speculate at this stage why many authors appear to be either unaware of or unwilling to adopt more recent methodological guidance and reporting items in their work. It could be that some authors are more familiar and comfortable with the older, less prescriptive framework and see no reason to change. It could be that more recent methodologies such as JBI’s guidance and the PRISMA-ScR appear more complicated and onerous to comply with and so may possibly be unfit for purpose from the perspective of some authors. In their 2005 publication, Arksey and O’Malley themselves called for scoping review (then scoping study) methodology to continue to be advanced and built upon by subsequent authors, so it is interesting to note a persistent resistance or lack of awareness from some authors. Whatever the reason or reasons, we contend that transparency and reproducibility are key markers of high-quality reporting of scoping reviews and that reporting a review’s conduct and results clearly and consistently in line with a recognised methodology or checklist is more likely than not to enhance rigour and utility. Scoping reviews should not be used as a synonym for an exploratory search or general review of the literature. Instead, it is critical that potential authors recognise the purpose and methodology of scoping reviews. In this editorial, we discuss the definition of scoping reviews, introduce contemporary methodological guidance and address the circumstances where scoping reviews may be conducted. Finally, we briefly consider where ongoing advances in the methodology are occurring.

What is a scoping review and how is it different from other evidence syntheses?

A scoping review is a type of evidence synthesis that has the objective of identifying and mapping relevant evidence that meets pre-determined inclusion criteria regarding the topic, field, context, concept or issue under review. The review question guiding a scoping review is typically broader than that of a traditional systematic review. Scoping reviews may include multiple types of evidence (i.e. different research methodologies, primary research, reviews, non-empirical evidence). Because scoping reviews seek to develop a comprehensive overview of the evidence rather than a quantitative or qualitative synthesis of data, it is not usually necessary to undertake methodological appraisal/risk of bias assessment of the sources included in a scoping review. Scoping reviews systematically identify and chart relevant literature that meet predetermined inclusion criteria available on a given topic to address specified objective(s) and review question(s) in relation to key concepts, theories, data and evidence gaps. Scoping reviews are unlike ‘evidence maps’ which can be defined as the figural or graphical presentation of the results of a broad and systematic search to identify gaps in knowledge and/or future research needs often using a searchable database [ 15 ]. Evidence maps can be underpinned by a scoping review or be used to present the results of a scoping review. Scoping reviews are similar to but distinct from other well-known forms of evidence synthesis of which there are many [ 16 ]. Whilst this paper’s purpose is not to go into depth regarding the similarities and differences between scoping reviews and the diverse range of other evidence synthesis approaches, Munn and colleagues recently discussed the key differences between scoping reviews and other common review types [ 3 ]. Like integrative reviews and narrative literature reviews, scoping reviews can include both research (i.e. empirical) and non-research evidence (grey literature) such as policy documents and online media [ 17 , 18 ]. Scoping reviews also address broader questions beyond the effectiveness of a given intervention typical of ‘traditional’ (i.e. Cochrane) systematic reviews or peoples’ experience of a particular phenomenon of interest (i.e. JBI systematic review of qualitative evidence). Scoping reviews typically identify, present and describe relevant characteristics of included sources of evidence rather than seeking to combine statistical or qualitative data from different sources to develop synthesised results.

Similar to systematic reviews, the conduct of scoping reviews should be based on well-defined methodological guidance and reporting standards that include an a priori protocol, eligibility criteria and comprehensive search strategy [ 11 , 12 ]. Unlike systematic reviews, however, scoping reviews may be iterative and flexible and whilst any deviations from the protocol should be transparently reported, adjustments to the questions, inclusion/exclusion criteria and search may be made during the conduct of the review [ 4 , 14 ]. Unlike systematic reviews where implications or recommendations for practice are a key feature, scoping reviews are not designed to underpin clinical practice decisions; hence, assessment of methodological quality or risk of bias of included studies (which is critical when reporting effect size estimates) is not a mandatory step and often does not occur [ 10 , 12 ]. Rapid reviews are another popular review type, but as yet have no consistent, best practice methodology [ 19 ]. Rapid reviews can be understood to be streamlined forms of other review types (i.e. systematic, integrative and scoping reviews) [ 20 ].

Guidance to improve the quality of reporting of scoping reviews

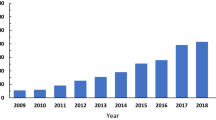

Since the first 2005 framework for scoping reviews (then termed ‘scoping studies’) [ 13 ], the popularity of this approach has grown, with numbers doubling between 2014 and 2017 [ 2 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is the most up-to-date and advanced approach for reporting scoping reviews which is largely based on the popular PRISMA statement and checklist, the JBI methodological guidance and other approaches for undertaking scoping reviews [ 11 ]. Experts in evidence synthesis including authors of earlier guidance for scoping reviews developed the PRISMA-ScR checklist and explanation using a robust and comprehensive approach. Enhancing transparency and uniformity of reporting scoping reviews using the PRISMA-ScR can help to improve the quality and value of a scoping review to readers and end users [ 21 ]. The PRISMA-ScR is not a methodological guideline for review conduct, but rather a complementary checklist to support comprehensive reporting of methods and findings that can be used alongside other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. For this reason, authors who are more familiar with or prefer Arksey and O’Malley’s framework; Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s extension of that framework or JBI’s methodological guidance could each select their preferred methodological approach and report in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR checklist.

Reasons for conducting a scoping review

Whilst systematic reviews sit at the top of the evidence hierarchy, the types of research questions they address are not suitable for every application [ 3 ]. Many indications more appropriately require a scoping review. For example, to explore the extent and nature of a body of literature, the development of evidence maps and summaries; to inform future research and reviews and to identify evidence gaps [ 2 ]. Scoping reviews are particularly useful where evidence is extensive and widely dispersed (i.e. many different types of evidence), or emerging and not yet amenable to questions of effectiveness [ 22 ]. Because scoping reviews are agnostic in terms of the types of evidence they can draw upon, they can be used to bring together and report upon heterogeneous literature—including both empirical and non-empirical evidence—across disciplines within and beyond health [ 23 , 24 , 25 ].

When deciding between whether to conduct a systematic review or a scoping review, authors should have a strong understanding of their differences and be able to clearly identify their review’s precise research objective(s) and/or question(s). Munn and colleagues noted that a systematic review is likely the most suitable approach if reviewers intend to address questions regarding the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness or effectiveness of a specified intervention [ 3 ]. There are also online resources for prospective authors [ 26 ]. A scoping review is probably best when research objectives or review questions involve exploring, identifying, mapping, reporting or discussing characteristics or concepts across a breadth of evidence sources.

Scoping reviews are increasingly used to respond to complex questions where comparing interventions may be neither relevant nor possible [ 27 ]. Often, cost, time, and resources are factors in decisions regarding review type. Whilst many scoping reviews can be quite large with numerous sources to screen and/or include, there is no expectation or possibility of statistical pooling, formal risk of bias rating, and quality of evidence assessment [ 28 , 29 ]. Topics where scoping reviews are necessary abound—for example, government organisations are often interested in the availability and applicability of tools to support health interventions, such as shared decision aids for pregnancy care [ 30 ]. Scoping reviews can also be applied to better understand complex issues related to the health workforce, such as how shift work impacts employee performance across diverse occupational sectors, which involves a diversity of evidence types as well as attention to knowledge gaps [ 31 ]. Another example is where more conceptual knowledge is required, for example, identifying and mapping existing tools [ 32 ]. Here, it is important to understand that scoping reviews are not the same as ‘realist reviews’ which can also be used to examine how interventions or programmes work. Realist reviews are typically designed to ellucide the theories that underpin a programme, examine evidence to reveal if and how those theories are relevant and explain how the given programme works (or not) [ 33 ].

Increased demand for scoping reviews to underpin high-quality knowledge translation across many disciplines within and beyond healthcare in turn fuels the need for consistency, clarity and rigour in reporting; hence, following recognised reporting guidelines is a streamlined and effective way of introducing these elements [ 34 ]. Standardisation and clarity of reporting (such as by using a published methodology and a reporting checklist—the PRISMA-ScR) can facilitate better understanding and uptake of the results of scoping reviews by end users who are able to more clearly understand the differences between systematic reviews, scoping reviews and literature reviews and how their findings can be applied to research, practice and policy.

Future directions in scoping reviews

The field of evidence synthesis is dynamic. Scoping review methodology continues to evolve to account for the changing needs and priorities of end users and the requirements of review authors for additional guidance regarding terminology, elements and steps of scoping reviews. Areas where ongoing research and development of scoping review guidance are occurring include inclusion of consultation with stakeholder groups such as end users and consumer representatives [ 35 ], clarity on when scoping reviews are the appropriate method over other synthesis approaches [ 3 ], approaches for mapping and presenting results in ways that clearly address the review’s research objective(s) and question(s) [ 29 ] and the assessment of the methodological quality of scoping reviews themselves [ 21 , 36 ]. The JBI Scoping Review Methodology group is currently working on this research agenda.

Consulting with end users, experts, or stakeholders has been a suggested but optional component of scoping reviews since 2005. Many of the subsequent approaches contained some reference to this useful activity. Stakeholder engagement is however often lost to the term ‘review’ in scoping reviews. Stakeholder engagement is important across all knowledge synthesis approaches to ensure relevance, contextualisation and uptake of research findings. In fact, it underlines the concept of integrated knowledge translation [ 37 , 38 ]. By including stakeholder consultation in the scoping review process, the utility and uptake of results may be enhanced making reviews more meaningful to end users. Stakeholder consultation can also support integrating knowledge translation efforts, facilitate identifying emerging priorities in the field not otherwise captured in the literature and may help build partnerships amongst stakeholder groups including consumers, researchers, funders and end users. Development in the field of evidence synthesis overall could be inspired by the incorporation of stakeholder consultation in scoping reviews and lead to better integration of consultation and engagement within projects utilising other synthesis methodologies. This highlights how further work could be conducted into establishing how and the extent to which scoping reviews have contributed to synthesising evidence and advancing scientific knowledge and understandings in a more general sense.

Currently, many methodological papers for scoping reviews are published in healthcare focussed journals and associated disciplines [ 6 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Another area where further work could also occur is to gain greater understanding on how scoping reviews and scoping review methodology is being used across disciplines beyond healthcare including how authors, reviewers and editors understand, recommend or utilise existing guidance for undertaking and reporting scoping reviews.

Whilst available guidance for the conduct and reporting of scoping review has evolved over recent years, opportunities remain to further enhance and progress the methodology, uptake and application. Despite existing guidance, some publications using the term ‘scoping review’ continue to be conducted without apparent consideration of available reporting and methodological tools. Because consistent and transparent reporting is widely recongised as important for supporting rigour, reproducibility and quality in research, we advocate for authors to use a stated scoping review methodology and to transparently report their conduct by using the PRISMA-ScR. Selection of the most appropriate review type for the stated research objectives or questions, standardising the use of methodological approaches and terminology in scoping reviews, clarity and consistency of reporting and ensuring that the reporting and presentation of the results clearly addresses the authors’ objective(s) and question(s) are also critical components for improving the rigour of scoping reviews. We contend that whilst the field of evidence synthesis and scoping reviews continues to evolve, use of the PRISMA-ScR is a valuable and practical tool for enhancing the quality of scoping reviews, particularly in combination with other methodological guidance [ 10 , 12 , 44 ]. Scoping review methodology is developing as a policy and decision-making tool, and so ensuring the integrity of these reviews by adhering to the most up-to-date reporting standards is integral to supporting well informed decision-making. As scoping review methodology continues to evolve alongside understandings regarding why authors do or do not use particular methodologies, we hope that future incarnations of scoping review methodology continues to provide useful, high-quality evidence to end users.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available upon request.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Article Google Scholar

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:15.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Peters M, Marnie C, Tricco A, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Paiva L, Dalmolin GL, Andolhe R, dos Santos W. Absenteeism of hospital health workers: scoping review. Av enferm. 2020;38(2):234–48.

Visonà MW, Plonsky L. Arabic as a heritage language: a scoping review. Int J Biling. 2019;24(4):599–615.

McKerricher L, Petrucka P. Maternal nutritional supplement delivery in developing countries: a scoping review. BMC Nutr. 2019;5(1):8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fusar-Poli P, Salazar de Pablo G, De Micheli A, et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:33–46.

Jowsey T, Foster G, Cooper-Ioelu P, Jacobs S. Blended learning via distance in pre-registration nursing education: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;44:102775.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: JBI; 2020.

Google Scholar

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):28.

Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Inf Libr J. 2019;36(3):202–22.

Brady BR, De La Rosa JS, Nair US, Leischow SJ. Electronic cigarette policy recommendations: a scoping review. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):88–104.

Truman E, Elliott C. Identifying food marketing to teenagers: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):67.

Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):224.

Moher D, Stewart L, Shekelle P. All in the family: systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):183.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Ghassemi M, et al. Same family, different species: methodological conduct and quality varies according to purpose for five types of knowledge synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;96:133–42.

Barker M, Adelson P, Peters MDJ, Steen M. Probiotics and human lactational mastitis: a scoping review. Women Birth. 2020;33(6):e483–e491.

O’Donnell N, Kappen DL, Fitz-Walter Z, Deterding S, Nacke LE, Johnson D. How multidisciplinary is gamification research? Results from a scoping review. Extended abstracts publication of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play. Amsterdam: Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. p. 445–52.

O’Flaherty J, Phillips C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: a scoping review. Internet High Educ. 2015;25:85–95.

Di Pasquale V, Miranda S, Neumann WP. Ageing and human-system errors in manufacturing: a scoping review. Int J Prod Res. 2020;58(15):4716–40.

Knowledge Synthesis Team. What review is right for you? 2019. https://whatreviewisrightforyou.knowledgetranslation.net/

Lv M, Luo X, Estill J, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a scoping review. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(15):2000125.

Shemilt I, Simon A, Hollands GJ, et al. Pinpointing needles in giant haystacks: use of text mining to reduce impractical screening workload in extremely large scoping reviews. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(1):31–49.

Khalil H, Bennett M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Peters M. Evaluation of the JBI scoping reviews methodology by current users. Int J Evid-based Healthc. 2020;18(1):95–100.

Kennedy K, Adelson P, Fleet J, et al. Shared decision aids in pregnancy care: a scoping review. Midwifery. 2020;81:102589.

Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Recio-Saucedo A, Griffiths P. Characteristics of shift work and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;57:12–27.

Feo R, Conroy T, Wiechula R, Rasmussen P, Kitson A. Instruments measuring behavioural aspects of the nurse–patient relationship: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(11-12):1808–21.

Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):33.

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–4.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, et al. Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):31.

Cooper S, Cant R, Kelly M, et al. An evidence-based checklist for improving scoping review quality. Clin Nurs Res. 2021;30(3):230–240.

Pollock A, Campbell P, Struthers C, et al. Stakeholder involvement in systematic reviews: a scoping review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):208.

Tricco AC, Zarin W, Rios P, Pham B, Straus SE, Langlois EV. Barriers, facilitators, strategies and outcomes to engaging policymakers, healthcare managers and policy analysts in knowledge synthesis: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e013929.

Denton M, Borrego M. Funds of knowledge in STEM education: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;1(2):71–92.

Masta S, Secules S. When critical ethnography leaves the field and enters the engineering classroom: a scoping review. Stud Eng Educ. 2021;2(1):35–52.

Li Y, Marier-Bienvenue T, Perron-Brault A, Wang X, Pare G. Blockchain technology in business organizations: a scoping review. In: Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii international conference on system sciences ; 2018. https://core.ac.uk/download/143481400.pdf

Houlihan M, Click A, Wiley C. Twenty years of business information literacy research: a scoping review. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2020;15(4):124–163.

Plug I, Stommel W, Lucassen P, Hartman T, Van Dulmen S, Das E. Do women and men use language differently in spoken face-to-face interaction? A scoping review. Rev Commun Res. 2021;9:43–79.

McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. Reporting scoping reviews - PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;123:177–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the other members of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) working group as well as Shazia Siddiqui, a research assistant in the Knowledge Synthesis Team in the Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto.

The authors declare that no specific funding was received for this work. Author ACT declares that she is funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. KKO is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Episodic Disability and Rehabilitation with the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of South Australia, UniSA Clinical and Health Sciences, Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre, Playford Building P4-27, City East Campus, North Terrace, Adelaide, 5000, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters & Casey Marnie

Adelaide Nursing School, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 101 Currie St, Adelaide, 5001, South Australia

Micah D. J. Peters

The Centre for Evidence-based Practice South Australia (CEPSA): a Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, 5006, Adelaide, South Australia

Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, Terrence Donnelly Health Sciences Complex, 3359 Mississauga Rd, Toronto, Ontario, L5L 1C6, Canada

Heather Colquhoun

Rehabilitation Sciences Institute (RSI), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Heather Colquhoun & Kelly K. O’Brien

Knowledge Synthesis Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 1053 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1Y 4E9, Canada

Chantelle M. Garritty

Southern California Evidence Review Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, 90007, USA

Susanne Hempel

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 774 Echo Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5N8, Canada

Tanya Horsley

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH), World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Etienne V. Langlois

Sunnybrook Research Institute, 2075 Bayview Ave, Toronto, Ontario, M4N 3M5, Canada

Erin Lillie

Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 160-500 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M5G 1V7, Canada

Kelly K. O’Brien

Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation (IHPME), University of Toronto, St. George Campus, 155 College Street 4th Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M6, Canada

UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organisation, Avenue Appia 20, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland

Ӧzge Tunçalp

McMaster Health Forum, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Michael G. Wilson

Department of Health Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, McMaster University, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada

Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, 209 Victoria Street, East Building, Toronto, Ontario, M5B 1T8, Canada

Wasifa Zarin & Andrea C. Tricco

Epidemiology Division and Institute for Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, 155 College St, Room 500, Toronto, Ontario, M5T 3M7, Canada

Andrea C. Tricco

Queen’s Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, School of Nursing, Queen’s University, 99 University Ave, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 3N6, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MDJP, CM, HC, CMG, SH, TH, EVL, EL, KKO, OT, MGW, WZ and AT all made substantial contributions to the conception, design and drafting of the work. MDJP and CM prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andrea C. Tricco .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

Author ACT is an Associate Editor for the journal. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Peters, M.D.J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H. et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev 10 , 263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Download citation

Received : 29 January 2021

Accepted : 27 September 2021

Published : 08 October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Scoping reviews

- Evidence synthesis

- Research methodology

- Reporting guidelines

- Methodological guidance

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

PSY290 - Research Methods

- Identifying & Locating Empirical Research Articles

- Survey & Test Instruments

Writing a Critical Review

Sample summaries, verbs to help you write the summary, how to read a scholarly article.

- APA Citation Style Help

A critical review is an academic appraisal of an article that offers both a summary and critical comment. They are useful in evaluating the relevance of a source to your academic needs. They demonstrate that you have understood the text and that you can analyze the main arguments or findings. It is not just a summary; it is an evaluation of what the author has said on a topic. It’s critical in that you thoughtfully consider the validity and accuracy of the author’s claims and that you identify other valid points of view.

An effective critical review has three parts:

- APA citation of article

- Clearly summarizes the purpose for the article and identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the research. (In your own words – no quotations.)

- Evaluates the contribution of the article to the discipline or broad subject area and how it relates to your own research.

Steps to Write a Critical Review:

- Create and APA style citation for the article you are reviewing.

- Skim the text: Read the title, abstract, introduction, and conclusion.

- Read the entire article in order to identify its main ideas and purpose.

Q. What were the authors investigating? What is their thesis? Q. What did the authors hope to discover?

D. Pay close attention to the methods used by the authors to collection information.

Q. What are the characteristics of the participants? (e.g.) Age/gender/ethnicity

Q. What was the procedure or experimental method/surveys used?

Q. Are their any flaws in the design of their study?

E. Review the main findings in the “Discussion” or “Conclusion” section. This will help you to evaluate the validity of their evidence, and the credibility of the authors. Q. Are their conclusions convincing? Q. Were their results significant? If so, describe how they were significant. F. Evaluate the usefulness of the text to YOU in the context of your own research.

Q. How does this article assist you in your research?

Q. How does it enhance your understanding of this issue?

Q. What gaps in your research does it fill?

Good Summary:

Hock, S., & Rochford, R. A. (2010). A letter-writing campaign: linking academic success and civic engagement. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 3 (2), 76-82.

Hock & Rochford (2010) describe how two classes of developmental writing students were engaged in a service-learning project to support the preservation of an on-campus historical site. The goal of the assignment was to help students to see how they have influence in their community by acting as engaged citizens, and to improve their scores on the ACT Writing Sample Assessment (WSA) exam. The authors report that students in developmental classes often feel disempowered, especially when English is not their first language. This assignment not only assisted them in elevating their written communication skills, but it also gave real-life significance to the assignment, and by extension made them feel like empowered members of the community. The advancement in student scores serves as evidence to support my research that when students are given assignments which permit local advocacy and active participation, their academic performance also improves.

Bad Summary:

Two ELL classes complete a service-learning project and improve their writing scores. This article was good because it provided me with lots of information I can use. The students learned a lot in their service-learning project and they passed the ACT exam.

Remember you're describing what someone else has said. Use verbal cues to make this clear to your reader. Here are some suggested verbs to use:

* Adapted from: http://www.laspositascollege.edu/raw/summaries.php

- << Previous: Survey & Test Instruments

- Next: APA Citation Style Help >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 5:43 PM

- URL: https://paradisevalley.libguides.com/PSY290

Write a Critical Review

Introduction, how can i improve my critical review, ask us: chat, email, visit or call.

Video: How to Integrate Critical Voice into Your Literature Review

Video: Note-taking and Writing Tips to Avoid Plagiarism

More help: Writing

- Book Writing Appointments Get help on your writing assignments.

- To introduce the source, its main ideas, key details, and its place within the field

- To present your assessment of the quality of the source

In general, the introduction of your critical review should include

- Author(s) name

- Title of the source

- What is the author's central purpose?

- What methods or theoretical frameworks were used to accomplish this purpose?

- What topic areas, chapters, sections, or key points did the author use to structure the source?

- What were the results or findings of the study?

- How were the results or findings interpreted? How were they related to the original problem (author's view of evidence rather than objective findings)?

- Who conducted the research? What were/are their interests?

- Why did they do this research?

- Was this research pertinent only within the author’s field, or did it have broader (even global) relevance?

- On what prior research was this source-based? What gap is the author attempting to address?

- How important was the research question posed by the researcher?

- Your overall opinion of the quality of the source. Think of this like a thesis or main argument.

- Present your evaluation of the source, providing evidence from the text (or other sources) to support your assessment.

In general, the body of your critical review should include

- Is the material organized logically and with appropriate headings?

- Are there stylistic problems in logical, clarity or language?

- Were the author(s) able to answer the question (test the hypothesis) raised

- What was the objective of the study?

- Does all the information lead coherently to the purpose of the study?

- Are the methods valid for studying the problem or gap?

- Could the study be duplicated from the information provided?

- Is the experimental design logical and reliable?

- How are the data organized? Is it logical and interpretable?

- Do the results reveal what the researcher intended?

- Do the authors present a logical interpretation of the results?

- Have the limitations of the research been addressed?

- Does the study consider other key studies in the field or other research possibilities or directions?

- How was the significance of the work described?

- Follow the structure of the journal article (e.g. Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion) - highlighting the strengths and weaknesses in each section

- Present the weaknesses of the article, and then the strengths of the article (or vice versa).

- Group your ideas according to different research themes presented in the source

- Group the strengths and weaknesses of the article into the following areas: originality, reliability, validity, relevance, and presentation

Purpose:

- To summarize the strengths and weaknesses of the article as a whole

- To assert the article’s practical and theoretical significance

In general, the conclusion of your critical review should include

- A restatement of your overall opinion

- A summary of the key strengths and weaknesses of the research that support your overall opinion of the source

- Did the research reported in this source result in the formation of new questions, theories or hypotheses by the authors or other researchers?

- Have other researchers subsequently supported or refuted the observations or interpretations of these authors?

- Did the research provide new factual information, a new understanding of a phenomenon in the field, a new research technique?

- Did the research produce any practical applications?

- What are the social, political, technological, or medical implications of this research?

- How do you evaluate the significance of the research?

- Find out what style guide you are required to follow (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago) and follow the guidelines to create a reference list (may be called a bibliography or works cited).

- Be sure to include citations in the text when you refer to the source itself or external sources.

- Check out our Cite Your Sources Guide for more information.

- Read assignment instructions carefully and refer to them throughout the writing process.

- Make an outline of your main sections before you write.

- If your professor does not assign a topic or source, you must choose one yourself. Select a source that interests you and is written clearly so you can understand it.

- << Previous: Start Here

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:58 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/CriticalReview

Suggest an edit to this guide

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Digital Health Device Collection

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

- What is a Systematic Review?

Types of Reviews

- Manuals and Reporting Guidelines

- Our Service

- 1. Assemble Your Team

- 2. Develop a Research Question

- 3. Write and Register a Protocol

- 4. Search the Evidence

- 5. Screen Results

- 6. Assess for Quality and Bias

- 7. Extract the Data

- 8. Write the Review

- Additional Resources

- Finding Full-Text Articles

Review Typologies

There are many types of evidence synthesis projects, including systematic reviews as well as others. The selection of review type is wholly dependent on the research question. Not all research questions are well-suited for systematic reviews.

- Review Typologies (from LITR-EX) This site explores different review methodologies such as, systematic, scoping, realist, narrative, state of the art, meta-ethnography, critical, and integrative reviews. The LITR-EX site has a health professions education focus, but the advice and information is widely applicable.

Review the table to peruse review types and associated methodologies. Librarians can also help your team determine which review type might be appropriate for your project.

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91-108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review?

- Next: Manuals and Reporting Guidelines >>

- Last Updated: Mar 20, 2024 2:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

Jetting Phenomenon in Cold Spray: A Critical Review on Finite Element Simulations

- Published: 15 April 2024

Cite this article

- S. Rahmati 1 ,

- J. Mostaghimi 1 ,

- T. Coyle 1 &

- A. Dolatabadi 1

84 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This paper offers a concise critical review of finite element studies of the jetting phenomenon in cold spray (CS). CS is a deposition technique wherein solid particles impact a substrate at high velocities, inducing severe plastic deformation and material deposition. These high-velocity particle impacts lead to the ejection of material in a jet-like shape at the periphery of the particle/substrate interface, a phenomenon known as "jetting". Jetting has been the subject of numerous studies over recent decades and remains a point of debate. Two main mechanisms, Adiabatic Shear Instability (ASI) and Hydrodynamic Pressure-Release (HPR), have been proposed to explain the jetting phenomenon. These mechanisms are mainly elucidated through finite element method (FEM) simulations, a numerical technique rooted in continuum mechanics. However, it is important to emphasize that FEM is limited by the equations established for analysis, and as such, its predictive capabilities are confined to those principles clearly defined within these equations. The choice of employed equations and approaches significantly influence the outcomes and predictions in FEM. While recognizing FEM's capabilities, this study reviews the ASI and HPR mechanisms within the context of CS. Additionally, this paper reviews FEM's algorithms and the core principles that govern FEM in calculating plastic deformation, which can lead to the formation of jetting.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Numerical simulation of friction extrusion: process characteristics and material deformation due to friction

George Diyoke, Lars Rath, … Benjamin Klusemann

Theories and Applications of CFD–DEM Coupling Approach for Granular Flow: A Review

Mahmoud A. El-Emam, Ling Zhou, … Ramesh Agarwal

Semi-confined blast loading: experiments and simulations of internal detonations

M. Kristoffersen, F. Casadei, … T. Børvik

H. Assadi, H. Kreye, F. Gärtner, and T. Klassen, Cold Spraying—A Materials Perspective, Acta Mater. , 2016, 116 , p 382-407. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACTAMAT.2016.06.034

Article CAS Google Scholar

K. Kim, M. Watanabe, and S. Kuroda, Jetting-Out Phenomenon Associated with Bonding of Warm-Sprayed Titanium Particles onto Steel Substrate, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2009, 18 , p 490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-009-9379-1

A.A. Tiamiyu, Y. Sun, K.A. Nelson, and C.A. Schuh, Site-Specific Study of Jetting, Bonding, and Local Deformation During High-Velocity Metallic Microparticle Impact, Acta Mater. , 2021, 202 , p 159-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2020.10.057

M. Razavipour, S. Rahmati, A. Zúñiga, D. Criado, and B. Jodoin, Bonding Mechanisms in Cold Spray: Influence of Surface Oxidation During Powder Storage, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2020 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-020-01123-5

Article Google Scholar

R. Nikbakht, M. Saadati, T.-S. Kim, M. Jahazi, H.S. Kim, and B. Jodoin, Cold Spray Deposition Characteristic and Bonding of CrMnCoFeNi High Entropy Alloy, Surf. Coat. Technol. , 2021, 425 , p 127748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2021.127748

H. Assadi, F. Gärtner, T. Stoltenhoff, and H. Kreye, Bonding Mechanism in Cold Gas Spraying, Acta Mater. , 2003, 51 , p 4379-4394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6454(03)00274-X

M. Hassani-Gangaraj, D. Veysset, V.K. Champagne, K.A. Nelson, and C.A. Schuh, Adiabatic Shear Instability is Not Necessary for Adhesion in Cold Spray, Acta Mater. , 2018, 158 , p 430-439. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACTAMAT.2018.07.065

H. Assadi, F. Gärtner, T. Klassen, and H. Kreye, Comment on ‘Adiabatic Shear Instability is Not Necessary for Adhesion in Cold Spray,’ Scr. Mater. , 2019, 162 , p 512-514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2018.10.036

M. Hassani-Gangaraj, D. Veysset, V.K. Champagne, K.A. Nelson, and C.A. Schuh, Response to Comment on “Adiabatic Shear Instability is Not Necessary for Adhesion in Cold Spray,” Scr. Mater. , 2019, 162 , p 515-519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2018.12.015

S. Rahmati and A. Ghaei, The Use of Particle/Substrate Material Models in Simulation of Cold-Gas Dynamic-Spray Process, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2014, 23 , p 530-540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-013-0051-4

W.H. Johnson and G.R. Cook, A constitutive model and data for metals subjected to large strains, high strain rates and high. Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics, The Hague, Netherlands (1983), p. 541-547

C.Y. Gao and L.C. Zhang, A Constitutive Model for Dynamic Plasticity of FCC Metals, Mater. Sci. Eng. A , 2010, 527 , p 3138-3143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2010.01.083

P. Landau, S. Osovski, A. Venkert, V. Gärtnerová, and D. Rittel, The Genesis of Adiabatic Shear Bands, Sci. Rep. , 2016, 6 , p 37226. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37226

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

V. Abaqus, 6.14 Online Documentation Help Theory Manual: Dassault Systms , Simulia Inc., Johnston, 2016.

Google Scholar

M. Grujicic, C.L. Zhao, W.S. DeRosset, and D. Helfritch, Adiabatic Shear Instability Based Mechanism for Particles/Substrate Bonding in the Cold-Gas Dynamic-Spray Process, Mater. Des. , 2004, 25 , p 681-688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2004.03.008

G. Bae, Y. Xiong, S. Kumar, K. Kang, and C. Lee, General Aspects of Interface Bonding in Kinetic Sprayed Coatings, Acta Mater. , 2008, 56 , p 4858-4868. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACTAMAT.2008.06.003

C.J. Akisin, C.J. Bennett, F. Venturi, H. Assadi, and T. Hussain, Numerical and Experimental Analysis of the Deformation Behavior of CoCrFeNiMn High Entropy Alloy Particles onto Various Substrates During Cold Spraying, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2022, 31 , p 1085-1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-022-01377-1

Q. Chen, W. Xie, V.K. Champagne, A. Nardi, J.-H. Lee, and S. Müftü, On Adiabatic Shear Instability in Impacts of Micron-Scale Al-6061 Particles with Sapphire and Al-6061 Substrates, Int. J. Plast. , 2023, 166 , p 103630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijplas.2023.103630

L. Palodhi and H. Singh, On the Dependence of Critical Velocity on the Material Properties During Cold Spray Process, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2020, 29 , p 1863-1875. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-020-01105-7

F. Meng, S. Yue, and J. Song, Quantitative Prediction of Critical Velocity and Deposition Efficiency in Cold-Spray: A Finite-Element Study, Scr. Mater. , 2015, 107 , p 83-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2015.05.026

F. Meng, H. Aydin, S. Yue, and J. Song, The Effects of Contact Conditions on the Onset of Shear Instability in Cold-Spray, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2015, 24 , p 711-719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-015-0229-z

C.-J. Li, W.-Y. Li, and H. Liao, Examination of the Critical Velocity for Deposition of Particles in Cold Spraying, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2006, 15 , p 212-222. https://doi.org/10.1361/105996306X108093

W.-Y. Li and W. Gao, Some Aspects on 3D Numerical Modeling of High Velocity Impact of Particles in Cold Spraying by Explicit Finite Element Analysis, Appl. Surf. Sci. , 2009, 255 , p 7878-7892. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APSUSC.2009.04.135

W.-Y. Li, H. Liao, C.-J. Li, G. Li, C. Coddet, and X. Wang, On High Velocity Impact of Micro-Sized Metallic Particles in Cold Spraying, Appl. Surf. Sci. , 2006, 253 , p 2852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2006.05.126

M.A. Adaan-Nyiak and A.A. Tiamiyu, Recent Advances on Bonding Mechanism in Cold Spray Process: A Review of Single-Particle Impact Methods, J. Mater. Res. , 2023, 38 , p 69-95. https://doi.org/10.1557/s43578-022-00764-2

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

W.-Y. Li, S. Yin, and X.-F. Wang, Numerical Investigations of the Effect of Oblique Impact on Particle Deformation in Cold Spraying by the SPH Method, Appl. Surf. Sci. , 2010, 256 , p 3725-3734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.01.014

M. Yu, W.-Y. Li, F.F. Wang, and H.L. Liao, Finite Element Simulation of Impacting Behavior of Particles in Cold Spraying by Eulerian Approach, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2012, 21 , p 745-752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-011-9717-y

B. Yildirim, S. Muftu, and A. Gouldstone, Modeling of high velocity impact of spherical particles, Wear , 2011, 270 , p 703-713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2011.02.003

S. Lepi, Practical Guide to Finite Elements: A Solid Mechanics Approach , Taylor & Francis, Oxford, 1998.

R. Hedayati and M. Sadighi, Bird Strike: An Experimental Theoretical and Numerical Investigation , Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2015.

K.H. Huebner, D.L. Dewhirst, D.E. Smith, and T.G. Byrom, The Finite Element Method for Engineers , Wiley, New York, 2001.

P. Wriggers, Nonlinear Finite Element Methods , Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2008.

L.M. Pereira, A. Zúñiga, B. Jodoin, R.G.A. Veiga, and S. Rahmati, Unraveling Jetting Mechanisms in High-Velocity Impact of Copper Particles Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Addit. Manuf. , 2023, 75 , p 103755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103755

F. Dunne and N. Petrinic, Introduction to Computational Plasticity , OUP Oxford, Oxford, 2005.

Book Google Scholar

E.A. de Souza Neto, D. Peric, and D.R.J. Owen, Computational Methods for Plasticity: Theory and Applications , Wiley, New York, 2011.

A. Khoei, Computational Plasticity in Powder Forming Processes , Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2010.

Q.H. Shah and H. Abid, LS-DYNA for Beginners: An Insight Into Ls-Prepost and Ls-Dyna , LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbrucken, 2012.

L.M. Kachanov, Fundamentals of the Theory of Plasticity , Dover Publications, Mineola, 2013.

M. Okereke and S. Keates, Finite Element Applications: A Practical Guide to the FEM Process , Springer, Cham, 2018.

C.Y. Gao, FE Realization of a Thermo-Visco-Plastic Constitutive Model Using VUMAT in ABAQUS/Explicit Program. Computational Mechanics: Proceedings of International Symposium on Computational Mechanics (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009), p. 301

L. Ming and O. Pantalé, An Efficient and Robust VUMAT Implementation of Elastoplastic Constitutive Laws in Abaqus/Explicit Finite Element Code, Mech. Ind. , 2018, 19 , p 308. https://doi.org/10.1051/meca/2018021

G.N. Devi, S. Kumar, T.B. Mangalarapu, G. Vinay, N.M. Chavan, and A.V. Gopal, Assessing Critical Process Condition for Bonding in Cold Spraying, Surf. Coat. Technol. , 2023, 470 , p 129839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.129839

Z. Dai, F. Xu, J. Wang, and L. Wang, Investigation of Dynamic Contact Between Cold Spray Particles and Substrate Based on 2D SPH Method, Int. J. Solids Struct. , 2023, 284 , p 112520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2023.112520

S. Rahmati, A. Zúñiga, B. Jodoin, and R.G.A. Veiga, Deformation of Copper Particles Upon Impact: A Molecular Dynamics Study of Cold Spray, Comput. Mater. Sci. , 2020, 171 , p 109219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2019.109219

N. Deng, D. Qu, K. Zhang, G. Liu, S. Li, and Z. Zhou, Simulation and Experimental Study on Cold Sprayed WCu Composite with High Retainability of W Using Core-Shell Powder, Surf. Coat. Technol. , 2023, 466 , p 129639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2023.129639

P. Khamsepour, C. Moreau, and A. Dolatabadi, Effect of Particle and Substrate Pre-heating on the Oxide Layer and Material Jet Formation in Solid-State Spray Deposition: A Numerical Study, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2023, 32 , p 1153-1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-022-01509-7

S. Rahmati and B. Jodoin, Physically Based Finite Element Modeling Method to Predict Metallic Bonding in Cold Spray, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2020, 29 , p 611-629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-020-01000-1

S. Rahmati, R.G.A. Veiga, A. Zúñiga, and B. Jodoin, A Numerical Approach to Study the Oxide Layer Effect on Adhesion in Cold Spray, J. Therm. Spray Technol. , 2021 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-021-01245-4

W.Y. Li, C. Zhang, C.-J. Li, and H. Liao, Modeling Aspects of High Velocity Impact of Particles in Cold Spraying by Explicit Finite Element Analysis, ASM Int. , 2009, 18 , p 921-933.

CAS Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Advanced Coating Technologies, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

S. Rahmati, J. Mostaghimi, T. Coyle & A. Dolatabadi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to S. Rahmati .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A: Cuboid Model

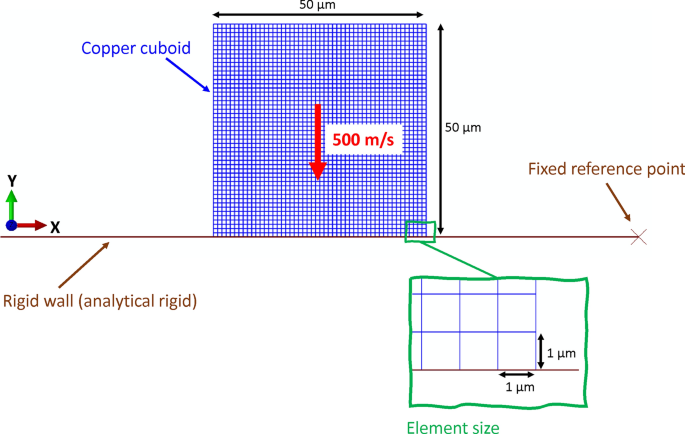

In the ABAQUS/Explicit software (Ref 14 ), a two-dimensional Lagrangian model employing four-node plane strain elements was employed to simulate the impact of a 50 µm copper cuboid onto a rigid wall (utilizing analytical rigid (Ref 14 )). A mesh size of 1 µm was opted for to ensure accurate representation of the extensive deformation induced during high-velocity impacts. It's worth noting that various element sizes were evaluated, and 1 μm was selected for its promising results in this study. A schematic representation of the simulation setup is shown in Fig. 16 . The impact velocity was set at 500 m/s, and the initial temperature was maintained at room temperature (300 K). Outputs were saved for each increment to capture the progressive behavior. For contact formulation, surface-to-surface contact was employed. The underside of the cuboid that collided with the substrate was defined as the slave surface (second surface), while the rigid wall surface was selected as the master surface (first surface) (Ref 14 ). The contact property was configured with a normal behavior (hard contact) using the default settings (Ref 14 ). Additionally, the material behavior was assumed to be linear elastic in this simulation The material properties utilized for this simulation are outlined in Table 1 .

Schematic representation of the simulation setup used in this study

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Rahmati, S., Mostaghimi, J., Coyle, T. et al. Jetting Phenomenon in Cold Spray: A Critical Review on Finite Element Simulations. J Therm Spray Tech (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-024-01766-8

Download citation

Received : 14 December 2023

Revised : 28 February 2024

Accepted : 20 March 2024

Published : 15 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-024-01766-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- finite elements method

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Transformations That Work

- Michael Mankins

- Patrick Litre

More than a third of large organizations have some type of transformation program underway at any given time, and many launch one major change initiative after another. Though they kick off with a lot of fanfare, most of these efforts fail to deliver. Only 12% produce lasting results, and that figure hasn’t budged in the past two decades, despite everything we’ve learned over the years about how to lead change.

Clearly, businesses need a new model for transformation. In this article the authors present one based on research with dozens of leading companies that have defied the odds, such as Ford, Dell, Amgen, T-Mobile, Adobe, and Virgin Australia. The successful programs, the authors found, employed six critical practices: treating transformation as a continuous process; building it into the company’s operating rhythm; explicitly managing organizational energy; using aspirations, not benchmarks, to set goals; driving change from the middle of the organization out; and tapping significant external capital to fund the effort from the start.

Lessons from companies that are defying the odds

Idea in Brief

The problem.

Although companies frequently engage in transformation initiatives, few are actually transformative. Research indicates that only 12% of major change programs produce lasting results.

Why It Happens

Leaders are increasingly content with incremental improvements. As a result, they experience fewer outright failures but equally fewer real transformations.

The Solution

To deliver, change programs must treat transformation as a continuous process, build it into the company’s operating rhythm, explicitly manage organizational energy, state aspirations rather than set targets, drive change from the middle out, and be funded by serious capital investments.

Nearly every major corporation has embarked on some sort of transformation in recent years. By our estimates, at any given time more than a third of large organizations have a transformation program underway. When asked, roughly 50% of CEOs we’ve interviewed report that their company has undertaken two or more major change efforts within the past five years, with nearly 20% reporting three or more.

- Michael Mankins is a leader in Bain’s Organization and Strategy practices and is a partner based in Austin, Texas. He is a coauthor of Time, Talent, Energy: Overcome Organizational Drag and Unleash Your Team’s Productive Power (Harvard Business Review Press, 2017).

- PL Patrick Litre leads Bain’s Global Transformation and Change practice and is a partner based in Atlanta.

Partner Center

This paper is in the following e-collection/theme issue:

Published on 22.4.2024 in Vol 26 (2024)