The French Revolutions: Causes and Impacts Essay

Introduction, origin and experience of the 1789 revolution, origin and experience of the 1848 revolution, similarities.

Bibliography

France has had many major revolutions that changed the country’s face, politically, socially and economically. By the 1700s, it had a full strength monarch system of government in which the king held absolute power also known as an absolute monarchy, most typified by Louis XIV. The nobles that were allowed to make legislations were corrupt and often enriched themselves leaving the poor or the so-called third estates to lavish in poverty 1 . This paper will attempt to compare and contrast the two revolutions, which occurred in 1789 and 1848, focusing on their causes as well as the impacts associated with their occurrences.

The 1789 revolution took place at a time when the French monarchy had absolute power, governing the whole country and implementing high tax due to massive debt caused by wars that King Louis XVI had participated in including the American war of independence. Its causes were mainly the hard social, economic and political cataclysm that they had and were worsening each day 2 . The country was heading into bankruptcy, making life much more difficult; people died daily and were buried in pauper graves, privileges were given to the nobles and the church. This led to a surge in protests involving mainly of the public and their sympathizers in various French cities like Paris, Lyon, Marseille, among others. The monarch’s symbol of power was the Bastille jail in Paris that had been in place for the past 400 years and its attack signified the beginning of a republican government. This saw execution of King Louis amid protest from other European countries that supported the rule of monarchy, and duped France into wars with other states like Britain, which had a constitutional monarchy, Spain and the Netherlands as well as Belgium.

The impacts of this ‘terror’ were worsened by the soaring prices with the devaluation of French currency due to unprecedented war that was in existence. This prompted price control in almost all foodstuffs as the Jacobins seized power in a reign of terror. The national assembly that was constituted mainly by the third estate constituted a committee of public safety, whose days were numbered with the escalating famine and shortages that faced the country. Besides, workable laws were still in the process of making as they fought to install a feasible constitution. Tax levied by the Catholic Church, which owned the largest land in the country added more injury to already soaring economic problems. The effects were realized but at a price since even though rights of citizens were instilled, ravaging famine, wars and terror consumed the population 3 . This revolution took new shift as power changed hands from monarchy, through to the Robespierre, Jacobins, in 1794 then to Directory through to 1799 when Napoleon took over under Consulate. Secularism became rampant; innovations, wars, and the restoration of monarchy are some of the results that surfaced 4 . For instance, After the King’s execution, Revolutionary tribunal and public safety committee were instituted; this saw a reign of terror, with ruling faction brutally killing potential enemies irrespective of their age, sex or condition. Paris alone recorded about 1400 deaths in the last six weeks to 27 July 1794, when it was replaced by Directory in 1975. This brought together 500 representatives, in a bicameral legislature consisting of two chambers, which lasted about 4 years to 1799 when it was replaced by Consulate.

This revolution took place in Europe at a time when reforms were the main activity. This ended the reinstated monarchy that had replaced the earlier revolution 5 . A second republic was instituted and later saw the election of Louis Napoleon as its president although he went on to establish an empire that lasted another 23 years. The Orleans monarch had been put in place following a protest that saw the July monarch, Charles abdicate his throne and flee to England in 1830. This new monarch stood among three opposing factions, the socialists, legitimists, and the republicans. With Louis Philippe at the helm of Orleans’s rule, mainly supported by the elites, favors were given to the privileged set; this led to disenfranchisement of the working classes as well as most of the middle class. Another problem that caused this revolution was the fact that only landowners were allowed to vote, separating the poor from the rich. The leader never cared for the needs of his subjects as some people were not permitted in the political arena. He also opposed the formation of a parliamentary system of government. Furthermore, the country was facing another economic crisis, and depression of the economy due to poor harvest 6 Poor transport system affected aid efforts during the depression and the crushing of those who rebelled.

It started with banquets as protests were outlawed, resulting in protests and barricades once Philippe outlawed banquets forcing him to abdicate and flee to England as well. Provisional government was formed, in what was called a second republic. Unemployment relief was incorporated in government policies and universal suffrage enacted, which added 9 million more voters. Workshops were organized which ensured the ‘right to work’ for every French citizen. Other impacts included reduced trading and luxury as the wealthy fled and this meant servicing credits was a problem. Conservatism increased in the new government with struggles emerging between the classes. Eventually, politics tilted to the right and this revolution failed once again, ushering in the second empire.

The two revolutions had very many similarities in their origins; the first was started out of social and political problems like, unemployment, which was widely prevalent. Similarly, the second was also aimed at establishing the right to work. In both cases, forced protests were used to ensure that revolutions took place and they all failed; the first, giving way to emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and the second ushering emperor napoleon III. In both cases, corruption was rampant as could be seen in the nobles of the first monarchy and the elite who were favored in the second monarch. Financial crisis and expected economic depression was significant in causing the two revolutions. The impacts were also similar in some ways as there were no stable governments during the two revolutions.

The first revolution was more radical as it caused terror and war as compared to the second, which was less violent; this is evident in the assault on Bastille. The causes of the first revolution were more founded on the basic rights of the people as compared to the second. The first revolution occurred when there was limited freedom to the public with their rights restricted to one vote by the third estate, while in the second revolution, there were provisional governments that had liberated some of the restrictions like the universal suffrage and characterized by struggles between classes. The first revolution was the initiation of the revolutions that followed and was characterized with heavy loss of lives during the reign of terror, while the second was characterized by more political and social systems that enforced changes.

The two revolutions failed to fulfill all their goals although they made several crucial changes such as universal suffrages, which added 9 million new voters. Many thoughts have considered the revolutions to make a huge impact on British Philosophical, intellectual and political life, having a major impact on the Western history. Some of the sympathizers of the revolution like Thomas Paine among other English radicals shared their sentiment at first, as they believed it was a sign of liberty, fraternity and Equality. However, when it turned into exterminations and terror, it gave second thoughts to the earlier supporters. In the end, after the second revolution’s failure, a second state was put in office, led by Napoleon III; he purged the republicans, thereby dissolving the National Assembly, and then established a second empire, restoring the old order. It is imperative to note that the revolutions made great significance in the developments of Europe as a whole.

- Betts F. R., 2000. Europe In Retrospect: A Brief History of the Past two hundred years. Britannia,LLC .

- Cody D.2007. French Revolution. The Victorian Web .Doyle W.1990

- The Oxford history of the French revolution . (3rd Ed.). Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress . ISBN 0192852213 . Web.

- Emmet K.1989. A Cultural History of the French Revolution. New Haven: Yale University Press . Print.

- Rappot M. 2009. 1848: Year of Revolution . Basic Books . Web.

- Smitha E. F., 2002. The French Revolution. Macrohistory and World Report. Web.

- Walker L.H. 2001. Sweet and Consoling Virtue: The Memoirs of Madame Roland. Eighteenth-Century Studies, French Revolutionary Culture .

- E. F. Smitha, 2002, The French Revolution. Macrohistory and World Report . P. 1-8.

- D. Cody 2007. French Revolution. The Victorian Web .

- K. Emmet 1989. A Cultural History of the French Revolution. New Haven: Yale University Press . Print.

- L.H. Walker 2001. Sweet and Consoling Virtue: The Memoirs of Madame Roland. Eighteenth-Century Studies, French Revolutionary Culture . Pg. 403-419.

- M. Rappot 2009. 1848: Year of Revolution. Basic Books .

- F. R. Betts 2000. Europe In Retrospect: A Brief History of the Past two hundred years . Britannia,LLC .

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 26). The French Revolutions: Causes and Impacts. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-french-revolutions-causes-and-impacts/

"The French Revolutions: Causes and Impacts." IvyPanda , 26 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-french-revolutions-causes-and-impacts/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The French Revolutions: Causes and Impacts'. 26 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The French Revolutions: Causes and Impacts." December 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-french-revolutions-causes-and-impacts/.

1. IvyPanda . "The French Revolutions: Causes and Impacts." December 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-french-revolutions-causes-and-impacts/.

IvyPanda . "The French Revolutions: Causes and Impacts." December 26, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-french-revolutions-causes-and-impacts/.

- The Revolution of 1848 in France

- The Revolutions 1789-1815 and 1848

- Parallels Between the Revolutions of 1848 and Arab Revolutions

- History: The French Declaration of 1789

- Revolution and Napoleon Between the 1789 and the 1815

- Napoleon Bonaparte, His Rise and Fall

- The French and Russian Revolutions of 1789 and 1917

- Napoleon Bonaparte’s Invasion of Russia

- Western Civilization: The French Revolution 1789-99

- Napoleon Bonaparte and Its Revolutions

- “Invisible Cities” by Calvino

- "Renaissance and Reformation: The Intellectual Genesis" by Anthony Levi

- Economic Situation of the Later Roman Empire

- Intellectual, Scientific and Cultural Changes in Europe Towards the End of 19th Century

- The History of European Expansion From the 14th Century - During the Age of Discovery

Home — Essay Samples — History — French Revolution — Causes of the French Revolution: Political, Social, and Economic

Causes of The French Revolution: Political, Social, and Economic

- Categories: French Revolution

About this sample

Words: 741 |

Published: Sep 7, 2023

Words: 741 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Political causes of the french revolution, social causes of the french revolution, economic causes of the french revolution.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 468 words

1 pages / 486 words

2 pages / 701 words

5 pages / 2464 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on French Revolution

The American and French Revolutions were two significant events in world history that led to the establishment of new political and social systems. While both were revolutions against the existing political authority, they had [...]

The historical relationship between Toussaint L'Ouverture and Napoleon Bonaparte is a complex and multi-faceted one that has been the subject of much scholarly debate and analysis. Both figures played pivotal roles in the [...]

The American and French Revolutions are two pivotal events in world history that have shaped the modern political landscape. Both revolutions were fueled by a desire for freedom, equality, and democracy, but they unfolded in [...]

Revolutions are pivotal events in history that have shaped the political, social, and economic landscape of the world. Two of the most influential revolutions are the French and American Revolutions, which occurred in the 18th [...]

Did you know that a loaf of bread costed a week's salary for 98% of the population, which mainly included peasants, in France during the French Revolution? The French Revolutions, one of the major Revolutions in all of Europe [...]

The Reign of Terror, a period of extreme violence and chaos during the French Revolution, has been a subject of much debate among historians and scholars. Some argue that the Reign of Terror was a necessary response to the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

French Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 12, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The French Revolution was a watershed event in world history that began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens radically altered their political landscape, uprooting centuries-old institutions such as the monarchy and the feudal system. The upheaval was caused by disgust with the French aristocracy and the economic policies of King Louis XVI, who met his death by guillotine, as did his wife Marie Antoinette. Though it degenerated into a bloodbath during the Reign of Terror, the French Revolution helped to shape modern democracies by showing the power inherent in the will of the people.

Causes of the French Revolution

As the 18th century drew to a close, France’s costly involvement in the American Revolution , combined with extravagant spending by King Louis XVI , had left France on the brink of bankruptcy.

Not only were the royal coffers depleted, but several years of poor harvests, drought, cattle disease and skyrocketing bread prices had kindled unrest among peasants and the urban poor. Many expressed their desperation and resentment toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes—yet failed to provide any relief—by rioting, looting and striking.

In the fall of 1786, Louis XVI’s controller general, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, proposed a financial reform package that included a universal land tax from which the aristocratic classes would no longer be exempt.

Estates General

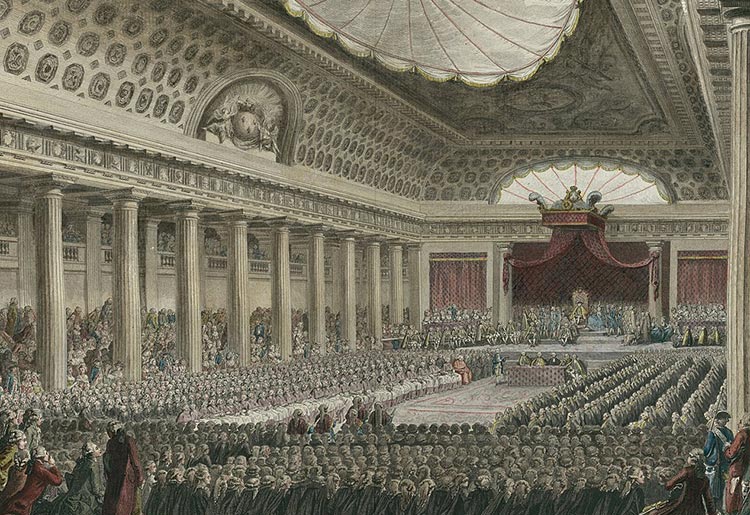

To garner support for these measures and forestall a growing aristocratic revolt, the king summoned the Estates General ( les états généraux ) – an assembly representing France’s clergy, nobility and middle class – for the first time since 1614.

The meeting was scheduled for May 5, 1789; in the meantime, delegates of the three estates from each locality would compile lists of grievances ( cahiers de doléances ) to present to the king.

Rise of the Third Estate

France’s population, of course, had changed considerably since 1614. The non-aristocratic, middle-class members of the Third Estate now represented 98 percent of the people but could still be outvoted by the other two bodies.

In the lead-up to the May 5 meeting, the Third Estate began to mobilize support for equal representation and the abolishment of the noble veto—in other words, they wanted voting by head and not by status.

While all of the orders shared a common desire for fiscal and judicial reform as well as a more representative form of government, the nobles in particular were loath to give up the privileges they had long enjoyed under the traditional system.

Tennis Court Oath

By the time the Estates General convened at Versailles , the highly public debate over its voting process had erupted into open hostility between the three orders, eclipsing the original purpose of the meeting and the authority of the man who had convened it — the king himself.

On June 17, with talks over procedure stalled, the Third Estate met alone and formally adopted the title of National Assembly; three days later, they met in a nearby indoor tennis court and took the so-called Tennis Court Oath (serment du jeu de paume), vowing not to disperse until constitutional reform had been achieved.

Within a week, most of the clerical deputies and 47 liberal nobles had joined them, and on June 27 Louis XVI grudgingly absorbed all three orders into the new National Assembly.

The Bastille

On June 12, as the National Assembly (known as the National Constituent Assembly during its work on a constitution) continued to meet at Versailles, fear and violence consumed the capital.

Though enthusiastic about the recent breakdown of royal power, Parisians grew panicked as rumors of an impending military coup began to circulate. A popular insurgency culminated on July 14 when rioters stormed the Bastille fortress in an attempt to secure gunpowder and weapons; many consider this event, now commemorated in France as a national holiday, as the start of the French Revolution.

The wave of revolutionary fervor and widespread hysteria quickly swept the entire country. Revolting against years of exploitation, peasants looted and burned the homes of tax collectors, landlords and the aristocratic elite.

Known as the Great Fear ( la Grande peur ), the agrarian insurrection hastened the growing exodus of nobles from France and inspired the National Constituent Assembly to abolish feudalism on August 4, 1789, signing what historian Georges Lefebvre later called the “death certificate of the old order.”

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

IIn late August, the Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen ( Déclaration des droits de l ’homme et du citoyen ), a statement of democratic principles grounded in the philosophical and political ideas of Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

The document proclaimed the Assembly’s commitment to replace the ancien régime with a system based on equal opportunity, freedom of speech, popular sovereignty and representative government.

Drafting a formal constitution proved much more of a challenge for the National Constituent Assembly, which had the added burden of functioning as a legislature during harsh economic times.

For months, its members wrestled with fundamental questions about the shape and expanse of France’s new political landscape. For instance, who would be responsible for electing delegates? Would the clergy owe allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church or the French government? Perhaps most importantly, how much authority would the king, his public image further weakened after a failed attempt to flee the country in June 1791, retain?

Adopted on September 3, 1791, France’s first written constitution echoed the more moderate voices in the Assembly, establishing a constitutional monarchy in which the king enjoyed royal veto power and the ability to appoint ministers. This compromise did not sit well with influential radicals like Maximilien de Robespierre , Camille Desmoulins and Georges Danton, who began drumming up popular support for a more republican form of government and for the trial of Louis XVI.

French Revolution Turns Radical

In April 1792, the newly elected Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria and Prussia, where it believed that French émigrés were building counterrevolutionary alliances; it also hoped to spread its revolutionary ideals across Europe through warfare.

On the domestic front, meanwhile, the political crisis took a radical turn when a group of insurgents led by the extremist Jacobins attacked the royal residence in Paris and arrested the king on August 10, 1792.

The following month, amid a wave of violence in which Parisian insurrectionists massacred hundreds of accused counterrevolutionaries, the Legislative Assembly was replaced by the National Convention, which proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French republic.

On January 21, 1793, it sent King Louis XVI, condemned to death for high treason and crimes against the state, to the guillotine ; his wife Marie-Antoinette suffered the same fate nine months later.

Reign of Terror

Following the king’s execution, war with various European powers and intense divisions within the National Convention brought the French Revolution to its most violent and turbulent phase.

In June 1793, the Jacobins seized control of the National Convention from the more moderate Girondins and instituted a series of radical measures, including the establishment of a new calendar and the eradication of Christianity .

They also unleashed the bloody Reign of Terror (la Terreur), a 10-month period in which suspected enemies of the revolution were guillotined by the thousands. Many of the killings were carried out under orders from Robespierre, who dominated the draconian Committee of Public Safety until his own execution on July 28, 1794.

Did you know? Over 17,000 people were officially tried and executed during the Reign of Terror, and an unknown number of others died in prison or without trial.

Thermidorian Reaction

The death of Robespierre marked the beginning of the Thermidorian Reaction, a moderate phase in which the French people revolted against the Reign of Terror’s excesses.

On August 22, 1795, the National Convention, composed largely of Girondins who had survived the Reign of Terror, approved a new constitution that created France’s first bicameral legislature.

Executive power would lie in the hands of a five-member Directory ( Directoire ) appointed by parliament. Royalists and Jacobins protested the new regime but were swiftly silenced by the army, now led by a young and successful general named Napoleon Bonaparte .

French Revolution Ends: Napoleon’s Rise

The Directory’s four years in power were riddled with financial crises, popular discontent, inefficiency and, above all, political corruption. By the late 1790s, the directors relied almost entirely on the military to maintain their authority and had ceded much of their power to the generals in the field.

On November 9, 1799, as frustration with their leadership reached a fever pitch, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup d’état, abolishing the Directory and appointing himself France’s “ first consul .” The event marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era, during which France would come to dominate much of continental Europe.

Photo Gallery

French Revolution. The National Archives (U.K.) The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State . Versailles, from the French Revolution to the Interwar Period. Chateau de Versailles . French Revolution. Monticello.org . Individuals, institutions, and innovation in the debates of the French Revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

History Grade 10 - Topic 3 Essay Questions

Causes of the French Revolution

Based on the 2012 Grade 10 NSC Exemplar Paper:

Grade 10 Past Exam Paper

Grade 10 Source Addendum

Grade 10 Past Exam Memo

Essay 1: What were the causes of the French Revolution?

In 1789 the bloody French Revolution began, which would continue till the late 1790’s. The aim of the revolution was to overthrow the monarchy and uproot the system of feudalism, and replace it with ideas of equality, liberty and fraternity. [1] The French revolution occurred for various reasons, including poor economic policies, poor leadership, an exploitative political- and social structures.

Political Causes

The political causes of the French revolution included the autocratic monarchy, bankruptcy and extravagant spending of royals. To understand the causes of the French Revolution, one needs to understand France’s political structure before the revolution began. An autocratic monarchy means that French society was governed by an all-powerful king or queen, believed to have been given divine right to rule by God. [2] These monarchs were hereditary rulers, which meant that the son or daughter of the monarch would be the next ruler. [3] As many believed the monarchs to be a “representative of God”, they did not question the orders of their rulers. But this unlimited power of the monarchs soon led to abuse. Under King Louis XIV reign all monarchs could have anyone arrested and imprisoned by the Letter de Cachet. The monarchs did not care for their subjects as even the innocent could be arrested and imprisoned at any time. This caused anxiety, panic and fear in France.

King Louis XIV reigned from 1643 to 1713. [4] After his death, his great-grandson, King Louis XV became king at the age of five. Both his parents and brother had passed away in 1712, and a regent, Philippe II, was appointed who would govern till he came of age. [5] When King Louis XV finally took the throne, he was a lazy leader who lacked self-confidence and spent more time with his mistresses than with the affairs of state. [6] His national policies never had firm direction. He became known as the “butterfly monarch”. [7] His involvement in the Seven Years War (1756 – 1763) drained France’s treasury. [8] While the country was bankrupt and many citizens were impoverished, taxes were generated to sustain a large army. [9] King Louis XV contributed to France’s bankruptcy due to overspending on his luxurious lifestyle and wars. [10]

The next leader, Louis XVI (1774 – 1793) reign also set the stage for a revolution. King Louis XVI is remembered as a simple man, but his wife Marie Antoinette lived in the lap of luxury. [11] Louis XVI inherited the kingdom and all the debt of France when he became king. He failed to fix the financial situation. The expensive upkeep of his palace and the unnecessary spending of Marie Antoinette angered the French population. Especially as the tax system excluded nobility from paying tax, while the poor paid for the royals’ luxurious lifestyles. By 1786 Charles de Calonne, the general of finances, warned against raising taxes of the poor as it could lead to unrest. [12] As King Louis XVI did not want to tax nobility, De Calonne had to approach European Banks for loans. [13] While King Louis was unable to fix France’s financial situation, his wife continued with her extravagant lifestyle. Marie-Antoinette’s never-minded response to the poor suffering is mostly reflected in the quote: “Let them eat cake”. [14] Even though no evidence could be found that she truly said it, the famous quote does portray the monarchy’s attitude. While many were starving, the monarchy turned a blind eye. This quote shows how oblivious they were to the suffering of their people.

The defective administration of generations of monarchs set the stage for a French revolution. The poor were no longer willing to pay for the monarchy’s extravagant lifestyles and unwise foreign policies. People were starting to revolt against the idea of “divine rule” and started to question the authority and wisdom of their monarchs.

Social Causes:

The second cause of the French revolution was based on the social structure of France. French society was based on the relics of feudalism, which divided the French population in to three classes based on the Estate System. [15] According to the Estate System, people’s status and rights were determined by the estate they owned. [16] The three estates included the clergy, the nobility and the peasants.

The first estate consisted of the clergy, which was subdivided into two groups, the upper and lower clergy. The higher clergy were at the top of the hierarchy in French society, while the lower clergy were impoverished. The higher clergy lived extravagantly, exploiting people and exempt from paying taxes. [17] While the lower clergy was also employed as workers of the church, monasteries and educational institutions, but not in high positions such as the higher clergy. [18]

The second estate consisted of the nobility, which included two groups, namely the court nobles and the provincial nobles. [19] They were also exempt from paying taxes. However, the provincial nobles actually cared for the people, while the court nobles only focused on leading scandalously wealthy lives. [20]

The third estate consisted of the peasants, which included the sweepers, farmers and cobblers. [21] They were the lowest classes in French society, who were forced to pay taxes to sustain the luxuriously living of the first and second estate.

But besides the unequal taxing given to the third estate, they were also unequally represented in court. The third estate represented 98% of the French population, yet they were outvoted by the first two estates. The third estate fought against this unequal representation and began to mobilize support for abolishing the noble veto. This meant that votes would be counted by the amount of people in favor or against a law, rather than nobles dictating laws. This led to opposition from the first two estates, who wanted to remain in control.

To fight against the current voting system, the Third Estate met on 17 June 1789 alone to change the title of National Assembly. [22] Three days later, they met at an indoor tennis court and undertook the Tennis Court Oath, declaring that would not end their fight until they achieved judicial, fiscal and governmental reform. [23] On 27 June, after 47 liberal nobles joined the Third Estate’s cause, Louis XVI accepted all three orders into a new assembly.

The rise of the third estate against the Estate System and unequal representation due to the class structure also gave rise to the French Revolution. The poor were angered to pay for the luxurious lifestyles of first and second estate. They were also tired of having 2% of the population veto all their rights and having inequal representation in court even though they made up 98% of French society.

Economic Causes

Another cause of the French revolution was the economic conditions of France. King Louis XIV “Seven Years War” left France bankrupt. His foreign policies led to expensive foreign wars, which emptied the coffers of the royal treasury. After his death, he was succeeded by Louis XVI. But as previously shown, even though the king was simple, his wife continued with frivolous spending. King Louis XVI also refused to listen to the economic counsel given to him, which led to necessary economic changes being ignored.

Firstly, when Louis XVI took the throne, Turgot was appointed Minister of Finance in 1774. Turgot’s first duty was to rid France of their debt. [24] He came up with a solution to appease the peasants and fix France’s financial situation by minimizing spending of the royal court and imposing taxes on all three estates. [25] However, Turgot’s solution was dismissed after Marie Antoinette intervened. Turgot was fired and Necker was appointed as the new Finance Minister in 1776. Necker remained King Louis XVI Finance Minister for seven years. [26] During his time he published a report of the income and expenses of the government, to appease the French population. [27] But in 1783, he was also fired. Finally, Calonne was appointed Minister of Finance in 1783. Calonne advised the king to improve France’s financial situation by approaching European banks for a loan. [28] The European banks were not keen to lend money to France, but Calonne was able to obtain a loan. Calonne’s solution proved problematic. When France finally did receive a loan, their debt doubled within three years from 300, 000, 000 to 600, 000, 000. [29] Thereafter, Calonne realized that his solution was not feasible and urged the king to impose taxes on all three classes. Finally, Calonne was also dismissed.

King Louis XVI economic decisions finally set the stage for the revolution. The monarchy refused to impose taxes on all three estates, while the royals continued living in a lap of luxury. These decisions created economic instability in France. The peasants were angered, as while they were starving, they had to maintain the standard of living for the rich. Therefore, the economic conditions in France was one of the main reasons for the revolution.

Ultimately, there was three main reasons for the French Revolution. The Estate System, economic policies and autocratic monarchy gave rise to a bloody revolution, which led to the need for equality, liberty and fraternity in France.

Essay 2: What is the Legacy of the French Revolution of 1789 or What were the consequences of the French Revolution?

Tip: If there is a term that is unfamiliar to you, please check out our French Revolution Glossary some definitions.

The Bloody French Revolution officially began when hundreds of French city workers stormed the Bastille fortress in Paris in 1789. [30] Although the revolution came to an end in the late 1790’s, its legacy (or consequences) had a significant impact on the World, especially other European countries. This statement will be examined by discussing various political and socio-economic legacies of the French Revolution of 1789, while discussing how the idea of the possibility that popular mobilization can overthrow established monarchies and aristocracies rose from the French Revolution of 1789.

Political Legacies:

When discussing the legacy of the French Revolution, it is important to understand the causes of the revolution as it gives one a better understanding of the desired outcomes. For example, one of the main causes was that French citizens who belonged to the Third Estate . grew significantly tired of the absolute power and wealth of the French monarchy and wanted a political system that represented the popular interests. Consequently, one of the direct consequences of the revolution was that France became a Republic; which indicated a step towards liberty, equality and democracy. [31] This need for liberty and equality spread to many other countries and especially to countries in central Europe, where popular protest and movements called for the election of parliaments and to ultimately demolish the feudalistic-approach of European life. [32]

As briefly mentioned, the French Revolution of 1789 demonstrated that an organized group of popular protest and mutual interests could demolish something as established as old monarchies and aristocracies. [33] This idea significantly led to the revolution of the slaves of Saint-Domingue, a French Colony on one of the Caribbean Islands, who mobilized themselves for the fight for their independence. [34] In 1804 this movement was able to finally break free from French colonial rule and establish the Republic of Haiti.

Socio-Economic Legacies:

When discussing the political movements that were influenced by the French Revolution, it is also important to discuss the Socio-Economic legacies that were influenced by the changes in the political environments. For example, the fall of the monarchy also meant that the French system of estates (based on Feudalism) also crumbled. This meant that the French middle class were able to gain better opportunities through acquiring more land (as the Church’s lands were nationalized) and having to pay less taxes (as they did not have to pay Feudal taxes anymore). [35] Furthermore, the elite classes (such as the nobles and corrupt clergy) lost most of their power and privileges. Therefore, it is evident that the revolution led to a significant change in the political, social and economic structures of France.

Growth of Nationalism

With the middle class and “peasants” (in this context, French farmers) gaining more opportunities and a better standard of living and the decline of Feudalism, as well as the loss of extreme privileges of the clergy and nobleman, a need for the growth in Nationalistic sentiments continued. Consequently, instead of the protection provided by the Feudalistic-structure , a French army was established. [36] Other examples of the lasting spread of French Nationalism, is the change of France’s flag (the Tricolore), the National anthem (the Marseillaise) and the creation of France’s National Day (Bastille Day). [37] The legacy of French Nationalism out of the French Revolution still exists today.

Conclusion:

When discussing the causes and outcomes of the French Revolution of 1789, it evident that the outcomes of the revolution had a lasting impact on the French political, social and economic way of life. As seen in the examples of the changing social structures, the change in the tax system and finally the strong rise in French Nationalism. It is also important to note the legacy created by the ideology of the French Revolution and its effect on many European countries. For example, as seen in the growth of the Jacobin movements. One of the most significant phenomena surrounding the French Revolution of 1789 and its legacy, is that the world was able to witness how people were able to organize themselves to fight for National interest and take down century old ways of life. This ultimately led to the legacy and the birth of the idea of the possibility of differing political ideologies. [38]

Tips & Notes:

- Check out our Essay Writing Skills for more tips on writing essays.

- Remember, this is just an example essay. You still need to use the work provided by your teacher or learned in class.

- It is important to check in with your teacher and make sure this meets his/her requirements. For example, they might prefer that you do not use headings in your essay.

This content was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by Ilse Brookes, Amber Fox-Martin & Simone van der Colff

[1] Author Unknown, “French Revolution”, History, (Uploaded: 9 November 2009), (Accessed: 29 April 2020), Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/france/french-revolution

[2] Author Unknown, “France Before the Revolution”, History Crunch, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 29 April 2020), Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/france/french-revolution

[3] Author Unknown, “France Before the Revolution”, History Crunch, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 29 April 2020), Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/france/french-revolution

[4] Author Unknown, “Louis XV”, Encyclopedia Britannica, (Uploaded: 11 February 2020), (Accessed 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Louis-XV

[7] V. Rana, “Causes of the French Revolution: Political, Social and Economic Causes’, History Discussion, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.historydiscussion.net/world-history/french-revolution/causes-of-french-revolution-political-social-and-economic-causes/1881

[8] Author Unknown, “The French Revolution (1789 – 1799)”, Sparknotes, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.sparknotes.com/history/european/frenchrev/section1/

[10] V. Rana, “Causes of the French Revolution: Political, Social and Economic Causes’, History Discussion, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.historydiscussion.net/world-history/french-revolution/causes-of-french-revolution-political-social-and-economic-causes/1881

[12] Author Unknown, “The French Revolution (1789 – 1799)”, Sparknotes, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.sparknotes.com/history/european/frenchrev/section1/

[14] J. M. Cunningham, “Did Marie-Antoinette really say “Let them eat Cake”?”, Encyclopedia Britannica, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.britannica.com/story/did-marie-antoinette-really-say-let-them

[15] Author Unknown, “France Before the Revolution”, History Crunch, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 29 April 2020), Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/france/french-revolution

[17] V. Rana, “Causes of the French Revolution: Political, Social and Economic Causes’, History Discussion, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.historydiscussion.net/world-history/french-revolution/causes-of-french-revolution-political-social-and-economic-causes/1881

[22] Author Unknown, “French Revolution”, History, (Uploaded: 9 November 2009), (Accessed: 29 April 2020), Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/france/french-revolution

[24] V. Rana, “Causes of the French Revolution: Political, Social and Economic Causes’, History Discussion, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.historydiscussion.net/world-history/french-revolution/causes-of-french-revolution-political-social-and-economic-causes/1881

[28] Author Unknown, “The French Revolution (1789 – 1799)”, Sparknotes, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.sparknotes.com/history/european/frenchrev/section1/

[29] V. Rana, “Causes of the French Revolution: Political, Social and Economic Causes’, History Discussion, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 30 April 2020), Available at: https://www.historydiscussion.net/world-history/french-revolution/causes-of-french-revolution-political-social-and-economic-causes/1881

[30] South African History Online, (2011), “The French Revolution,” Grade 10 – Topic 3, South African History Online (online), Available at https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/grade-10-topic-3-french-revolution-0 (Accessed: 6 June 2020)

[31] J. Battaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, (2011), “Grade 10 Learner’s Book,” Oxford in Search of History. Oxford University Press, South Africa.

[32] UKEssays, November 2018, “Legacies of the French Revolution,” UKEssays (online). Available at https://www.ukessays.com/essays/history/the-major-legacies-of-the-frenc… (Accessed 5 June 2020).

[33] UKEssays, November 2018, “Legacies of the French Revolution,” UKEssays (online). Available at https://www.ukessays.com/essays/history/the-major-legacies-of-the-frenc… (Accessed 5 June 2020).

[34] UKEssays, November 2018, “Legacies of the French Revolution,” UKEssays (online). Available at https://www.ukessays.com/essays/history/the-major-legacies-of-the-frenc… (Accessed 5 June 2020).

[35] J. Battaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, (2011), “Grade 10 Learner’s Book,” Oxford in Search of History. Oxford University Press, South Africa.

[36] J. Battaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, (2011), “Grade 10 Learner’s Book,” Oxford in Search of History. Oxford University Press, South Africa.

[37] J. Battaro & P. Visser & N. Worden, (2011), “Grade 10 Learner’s Book,” Oxford in Search of History. Oxford University Press, South Africa.

[38] UKEssays, November 2018, “Legacies of the French Revolution,” UKEssays (online). Available at https://www.ukessays.com/essays/history/the-major-legacies-of-the-frenc… (Accessed 5 June 2020).

[1] Battaro, J. & Visser, P. & Worden, N., 2011, Oxford in Search of History: Grade 10 Learner’s Book, Oxford University Press, South Africa.

[2] Goldstone, J.A. “A Fourth Generation of Revolutionary Theory”, Annual Reviews, (Vol. 4), 139 – 187.

[2] Schwartz, M. “History 151: The French Revolution: Causes, Outcomes, Confliction Interpretations”, (Accessed: 28 April 2020), Mount Holyoke Available at: https://www.mtholyoke.edu/courses/rschwart/hist151s03/french_rev_causes_consequences.htm

[3] South African History Online, November 2011, “The French Revolution”, Grade 10 – Topic 10 (online). Available at https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/grade-10-topic-3-french-revolution-0 (Accessed: 6 June 2020).

[4] Tulloch, S., Reader’s Digest Oxford Complete Wordfinder: A Unique and Powerful Combination of Dictionary and Thesaurus, London: The Reader’s Digest Association Limited, date unknown.

[5] UKEssays, November 2018, “Legacies of the French Revolution,” UKEssays (online). Available at https://www.ukessays.com/essays/history/the-major-legacies-of-the-frenc… (Accessed 5 June 2020).

Return to topic: The French Revolution

Return to SAHO Home

Return to History Classroom

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

- French Revolution and Napoleon

The 6 Main Causes of the French Revolution

The main causes of the french revolution remain debated. the middle class resented political exclusion, the lower classes didn't want to support the current feudal system and the government was on the brink of bankruptcty. here we take a deeper look into the main causes of the french revolution..

Sarah Roller

27 sep 2021, @sarahroller8.

This educational video is a visual version of this article and presented by Artificial Intelligence (AI). Please see our AI ethics and diversity policy for more information on how we use AI and select presenters on our website.

In 1789, France was the powerhouse of Europe, with a large overseas empire, strong colonial trade links as well as a flourishing silk trade at home, and was the centre of the Enlightenment movement in Europe. The Revolution which engulfed France shocked her European counterparts and changed the course of French politics and government completely. Many of its values – l iberté, égalité, fraternité – are still widely used as a motto today.

1. Louis XVI & Marie Antoinette

France had an absolute monarchy in the 18th century – life centred around the king, who had complete power. Whilst theoretically this could work well, it was a system heavily dependent on the personality of the king in question. Louis XVI was indecisive, shy and lacked the charisma and charm which his predecessors had so benefited from.

The court at Versailles , just outside Paris, had between 3,000 and 10,000 courtiers living there at any one time, all bound by strict etiquette. Such a large and complex social set required management by the king in order to manage power, bestow favours and keep a watchful eye over potential troublemakers. Louis simply didn’t have the capability or iron will necessary to do this.

Louis’ wife and queen, Marie Antoinette , was an Austrian-born princess whose (supposedly) profligate spending, Austrian sympathies and alleged sexual deviancy were targeted repeatedly. Incapable of acting in a way which might have transformed public opinion, the royal couple saw themselves become scapegoats for far more issues than those which they could control.

‘Marie Antoinette en chemise’, portrait of the queen in a muslin dress (by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1783)

Image Credit: Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As an absolute monarch, Louis was also held somewhat responsible – along with his advisors – for failures. Failures could only be blamed on advisors or external parties for so long, and by the late 1780s, the king himself was the target of popular discontent and anger rather than those around him: a dangerous position for an absolute monarch to be in. Whilst contemporaries may have perceived the king as being anointed by God, it was their subjects who permitted them to maintain this status.

2. Inherited problems

By no means did Louis XVI inherit an easy situation. The power of the French monarchy had peaked under Louis XIV, and by the time Louis XVI inherited, France found herself in an increasingly dire financial situation, weakened by the Seven Years War and American War of Independence .

With an old and inefficient taxation system which saw large portions of the wealthiest parts of French society exempt from major taxes, the burden was carried by the poorest and simply didn’t provide enough cash.

Variations by region also caused unhappiness: Brittany continued to pay the gabelle (salt tax) and the pays d’election no longer had regional autonomy, for example. The system was clunky and unfair, with some areas over-represented and some under-represented in government and through financial contributions. It was desperately in need of sweeping reforms. The French economy was also growing increasingly stagnant. Hampered by internal tolls and tariffs, regional trade was slow and the agricultural and industrial revolution which was hitting Britain was much slower to arrive, and to be adopted in France.

3. The Estates System & the bourgeoise

The Estates System was far from unique to France: this ancient feudal social structure broke society into 3 groups, clergy, nobility and everyone else. In the Medieval period, prior to the boom of the merchant classes, this system did broadly reflect the structure of the world. As more and more prosperous self-made men rose through the ranks, the system’s rigidity became an increasing source of frustration. The new bourgeoise class could only make the leap to the Second Estate (the nobility) through the practice of venality, the buying and selling of offices.

Following parlements blocking of reforms, Louis XVI was persuaded to call an assembly known as the Estates General, which had last been called in 1614. Each estate drew up a list of grievances, the cahier de doleances, which were presented to the king. The event turned into a stalemate, with the First and Second Estates continually voting to block the Third Estate out of a petty desire to keep their status firm, refusing to acknowledge the need to work together to achieve reform.

Opening of the Estates-General in Versailles 5 May 1789

Image Credit: Isidore-Stanislaus Helman (1743-1806) and Charles Monnet (1732-1808), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

These deep divisions between the estates were a major contributing factor to the eruption of revolution. With an ever-growing and increasingly loud Third Estate, the prospect of meaningful societal change began to increasingly appear to be something of a possibility.

4. Taxation & money

French finances were a mess by the late 18th century. The taxation system allowed the wealthiest to avoid paying virtually any tax at all, and given that wealth almost always equalled power, any attempt to push through radical financial reforms was blocked by the parlements. Unable to change the tax, and not daring to increase the burden on those who already shouldered it, Jacques Necker, the finance minister, raised money through taking out loans rather than raising taxes. Whilst this had some short term benefits, loans accrued interest and pushed the country further into debt.

In an attempt to add some form of transparency to royal expenditure and to create a more educated and informed populace, Necker published the Crown’s expenses and accounts in a document known as the Compte rendu au roi. Instead of placating the situation, it in fact gave the people an insight into something they had previously considered to be none of their concern.

With France on the brink of bankruptcy, and people more acutely aware and less tolerant of the feudal financial system they were upholding, the situation was becoming more and more delicate. Attempts to push through radical financial reforms were made, but Louis’ influence was too weak to force his nobles to bend to his will.

5. The Enlightenment

Historians debate the influence of Enlightenment in the French Revolution. Individuals like Voltaire and Rousseau espoused values of liberty, equality, tolerance, constitutional government and the separation of church and state. In an age where literacy levels were increasing and printing was cheap, these ideas were discussed and disseminated far more than previous movements had been.

Many also view the philosophy and ideals of the First Republic as being underpinned by Enlightenment ideas, and the motto most closely associated with the revolution itself – ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ – can be seen as a reflection of key ideas in Enlightenment pamphlets.

Voltaire, Portrait by Nicolas de Largillière, c. 1724

Image Credit: Nicolas de Largillière, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

6. Bad luck

Many of these issues were long term factors causing discontent and stagnation in France, but they had not caused revolution to erupt in the first 15 years of Louis’ reign. The real cost of living had increased by 62% between 1741 and 1785, and two successive years of poor harvests in 1788 and 1789 caused the price of bread to be dramatically inflated along with a drop in wages.

This added hardship added an extra layer of resentment and weight to the grievances of the Third Estate, which was largely made up of peasants and a few bourgeoise. Accusations of the extravagant spending of the royal family – irrespective of their truth – further exacerbated tensions, and the king and queen were increasingly targets of libelles and attacks in print.

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

Causes of French Revolution: Political, Social and Economic Causes

Causes of French Revolution: Political, Social and Economic Causes!

The three main causes of French revolution are as follows: 1. Political Cause 2. Social Cause 3. Economic Cause.

1. Political Cause:

During the eighteen the Century France was the centre of autocratic monarchy. The French Monarchs had unlimited power and they declared themselves as the “Representative of God”.

Image Source: 2.bp.blogspot.com/_8uW1gTbUKfs/TRarqf5sauI/AAAAAAAAAWE/atK90o6ZfTk/s1600/French-Revolution-Logo-FINAL.jpg

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Louis XIV was the exponent of this view. The French Monarchs engaged themselves in luxurious and extravagance at the royal court of Versailles. They enjoyed unlimited power. By the Letter de Catchet, they arrested any person at any time and imprisoned them. They paid no attention towards their subjects.

Louis XIV (1643-1715) of the Bourbon Dynasty was a powerful monarch. He was an efficient, hard-working and confident ruler. He participated in many wars. Louis XIV’s concept of unlimited royal power is revealed by his famous remarks, “I am the State”.

Louis XV (1715-1774) succeeded Louix XIV He was a ‘butterfly monarch’. His defective foreign policy weakened the economic condition of France. Louis XV fought the Seven Years War against England which brought nothing for France. France became bankrupt due to over expenditure in wars and luxury. He realised it later on. Before his death he cried-‘After me the Deluge’.

After Louis XV, Louis XVI (1774-1793) ascended the throne of France. During that period, the economic condition of France became weak. Louis XVI was an innocent and simple man. But he was influenced by his queen Marie Antoinette who always interfered in the state affairs.

Out of frustration he uttered-“Oh! What a burden of mine and they have taught me nothing.” Marie Antoinette was the daughter of Marie Theresa, the Austrian Empress. She always felt proud as she was the daughter of Austrain Empress. She always enjoyed luxurious and extravagant life. She sowed seed of the French Revolution. Thus, the autrocratic monarchy, defective administration, extravagant expenditure formed the political cause of the French Revolution.

2. Social Cause:

The Social condition of France during the eighteenth century was very miserable. The then French Society was divided into three classes— the Clergy, Nobles and Common People.

The Clergy belonged to the First Estate. The Clergy was subdivided into two groups i.e. the higher clergy and the lower clergy. The higher clergy occupied the top position in the society. They managed the churches, monasteries and educational institutions of France. They did not pay any tax to the monarch.

They exploited the common people in various ways. The higher clergy lived in the midst of scandalous luxury and extravagance. The common people had a strong hatred towards the higher clergy. On the other hand, the lower clergy served the people in true sense of the term and they lived a very miserable life.

The Nobility was regarded as the Second Estate in the French Society. They also did not pay any tax to the king. The Nobility was also sub divided into two groups-the Court nobles and the provincial nobles. The court nobles lived in pomp and luxury. They did not pay any heed towards the problems of the common people of their areas.

On the other hand, the provincial nobles paid their attention towards the problems of the people. But they did not enjoy the same privileges as the Court nobles enjoyed. The Third Estate formed a heterogenous class. The farmers, cobblers, sweepers and other lower classes belonged to this class. The condition of the farmers was very miserable.

They paid the taxes like Taille, Tithe and Gable. Inspite of this, the clergies and the nobles employed them in their fields in curve. The Bourgeoisie formed the top most group of the Third Estate. The doctors, lawyers, teachers, businessmen, writers and philosophers belonged to this class. They had the wealth and social status. But the French Monarch, influenced by the clergies and nobles, ranked them as the Third Estate.

So they influenced the people for revolution. They aroused the common people about their rights. Thus, the common people became rebellious. The lower Clergies and the provincial nobles also joined their hands with the common people along with the bourgeoisie. So the French Revolution is also known as the ‘Bourgeoisie Revolution’.

3. Economic Cause:

The economic condition of France formed another cause for the outbreak of the French Revolution. The economic condition of France became poor due to the foreign wars of Louis XIV, the seven years War of Louis XV and other expensive wars. During the reign period of Louis XVI, the royal treasury became empty as extravagant expenses of his queen Marie Antoinette.

To get rid of this condition. Louis XVI appointed Turgot as his Finance Minister in 1774. Turgot tried to minimise the expenditure of the royal court. He also advised the king to impose taxes on every classes of the society. But due to the interference of Queen Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI dismissed Turgot.

Then Necker was appointed as the Finance Minister in 1776. He published a report on the income and expenditure of the State in order to arouse the people. But he was also dismissed by the king.

The next person who was appointed by the King as the Finance Minister of France in 1783 was Callone. He adapted the policy of borrowing in order to meet the expenditure of the royal court. But due to this policy, the national debt of France increased from 300,000,000 to 600,000,000 Franks only in three years.

Then Callone proposed to impose taxes on all the classes. But he was dismissed by the king. In this situation, the king at last summoned the States General. The economic instability formed one of the most important causes of the French Revolution.

Related Articles:

- French Revolution: Influence, Causes and Course of the Revolution

- Coalitions: First, Second, Third and Fourth Coalition | French Revolution

- The Causes of French Revolution

- 6 Great Personalities of the French Revolution

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Social, Philosophical, and Economic Causes of the French Revolution

Related Papers

Constellations

Hayley Parsons

Luísa Tilhe

Marie Antoinette is remembered for many things. Among them, her lavish lifestyle and, perhaps most notably, the infamous "let them eat cake". She is, by all accounts, a symbol of everything the French Revolution was fighting against. As a result, we tend to think about the queen uncomplicatedly, letting her notoriety be the only thing we remember her for. This article will explore the complexity of her reputation in an attempt to understand the idea that Marie Antoinette's individual behavior wasn't so much the problem, but that she might have simply been at the wrong place at the wrong time.

Historical Reflections Reflexions Historiques

Thomas Kaiser

Courtney Herber

Palak Dhingra

Jade Thomas

This essay examines the debate concerning the interpretations of Marie Antoinette, which have changed a multitude of times through the course of history. This paper will examine several interpretations of Marie Antoinette; " the myths of the evil, decadent queen " versus " the real person " as well as how the primary sources, libelles, portraits, letters, have affected the modern interpretations of Antoinette. It does not attempt to ask which of the interpretations are 'correct' but rather seeks an answer to what the changing interpretations reveal about the general nature of history. The first section of this essay explores the primary sources; two portraits of Antoinette and several libelles, which attacked the aristocracy throughout Louis XVI's reign. The primary sources reflect two separate interpretations of the queen; the libelles reflect the bourgeois attitude of Antoinette-" the profligate and promiscuous " woman, and the portraits reflect a kind, matronly ideology about the Queen. The remainder of this response explores some of the modern sources and how they have been affected by the negative interpretations of the past. Stephan Zweig and Thomas Jefferson's account which reflects the émigrés account of Antoinette, opposed to Sofia Coppola's account of Antoinette, which features a sympathetic light shed over the teen queen, drawing attention to the loneliness she felt, and her young innocence.

Rai Farhatullah

Gender <html_ent glyph="@amp;" ascii="&"/> History

Clare Crowston

RELATED PAPERS

Álvaro Sanchez

Asian Journal of Medical Radiological Research

Academia I N T E R N A T I O N A L Journals

Murat Ugur Bozoglu

Alvaro Martel

IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement

Shouchen Dun

Limnology and Oceanography

Sandor Mulsow

Electronics And Electrical Engineering

Siamak Haghipour

Journal of Scleroderma and Related Disorders

Véronique Ramoni

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education

Daniel Brazeau

Romanica Olomucensia

Atinati Mamatsashvili

Frontiers in Immunology

Chung-Chih Tseng

Muhammad Fata

Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH)

Salleh Amat

Brazilian Journal of Development

Francisco Machado

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences

Noor Rahmat

Susan Gabriela Soliz Navia

Physics Letters B

Adam malik Malik

PLoS Pathogens

Jackson Orem

South African Journal of Marine Science

Sheldon Dudley

Cecylia Sadowska-Snarska

Journal of anatolian environmental and animal sciences

Fulya Sariyilmaz

Diagnostics

Eleftheria Sergaki

Karl-eric Magnusson

Journal of the American College of Cardiology

Afonso Shiozaki

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with JSH?

- About Journal of Social History

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Intellectual History and the Causes of the French Revolution

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jack R Censer, Intellectual History and the Causes of the French Revolution, Journal of Social History , Volume 52, Issue 3, Spring 2019, Pages 545–554, https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shy082

- Permissions Icon Permissions

From the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, historians, politicians, and even the interested public believed radical ideas to be at the bottom of this upheaval. Upstaged by social explanations, particularly in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, intellectual accounts have regained prominence, as recent scholarship has reiterated that ideas mattered. But what ideas? This essay focuses on those ideas that became evident at and around the outbreak of the revolution in 1788–89. For this period, a new wave of scholarship emphasizes not the idea of equality but rather historic rights and patriotism. In these accounts, Enlightenment notions of natural law provided the central justification for radicalizing the revolution as the decade proceeded. Beyond patriotism and rights, this essay also examines other competing discourses, especially those that challenged the church.

Many histories of the French Revolution, beginning with those written in the era itself, assumed, almost axiomatically, that the ideas of the philosophes had caused the “coming” of the event. 1 As social and other historians undermined that theory, intellectual historians moved in new directions, particularly toward the social history of ideas. Most visibly, in the 1960s, Robert Darnton and François Furet showed how subversive (even if not actually revolutionary) ideas had seeped into political culture through pornography and porous state borders. 2 Jürgen Habermas enlarged this vision by arguing that a “public sphere” had emerged in France that allowed subversive ideas and practices in various milieus, such as Freemasonry, the growing periodical press, and learned societies. 3 Still, few scholars claimed a direct link between these ideas and revolution.

Nonetheless, scholarly interest in ideas radically sharpened after the publication of François Furet’s Penser la revolution française in 1978, which opened up a new approach to intellectual history. 4 The first half of the book lambasted the Marxist explanation for the Revolution, which Furet labeled a “catechism” with class struggle at its absolute, immutable center. The twentieth-century Marxists who advocated this view saw themselves as the obvious heirs to the founding of the French republic, but Furet dismissed the Marxist interpretation as sheer fabrication.

Having pushed aside class conflict as the Revolution’s central dynamic, Furet succinctly posited his own theory that even before 1789 the monarchy was toothless. Into that power vacuum, sailed Rousseau’s Social Contract , a tract so powerful that its message eclipsed other ideologies and installed a potent logic—the absolute dominance of popular sovereignty. Yet, activating popular sovereignty required an advocate, an individual who could claim to embody the people’s will. Robespierre filled this role admirably, but he also created the potential for individual tyranny far more potent than that of a king whose authority was inherent in his body but surely did not represent the France of millions of people. From this fatal flaw eventually followed the Committee of Public Safety and the Terror. Furet’s theory was novel: by reducing the Revolution to the Terror, and blaming all of it on the logic of popular sovereignty derived from Rousseau, he tied the philosophe directly to the Revolution. Furet’s approach, drawn sharply to make a criticism of the Revolution as well as a scholarly point, was more specific than those that more generally connected the Enlightenment to the Revolution.

Although Furet’s interpretation did much to supplant Marxist and more traditional intellectual interpretations, it was criticized by scholars who contended that Rousseau’s fame had sprung far more from his sentimental writings than from the Social Contract . More recently, however, some scholars have resuscitated Rousseau’s influence. 5 Nonetheless, Furet provided no explanation for the revolutionaries’ acceptance of Rousseauian ideas other than the political vacuum and the rigorous logic springing from Rousseau’s belief that equality had no limits. How could these specific ideas hijack the mindset of a population?

Keith Baker articulated a parallel but different explanation for the acceptance of revolutionary ideology. 6 He put forth the abstract concept that every individual lives in an environment with discourses—ideational resources—that compete for attention. Facing these choices, people rather unconsciously pick and assemble notions that provide concrete solutions to material problems. In 1789, as governmental problems abounded, the elite—particularly dissatisfied elites—adopted three somewhat disparate discourses to frame their response. Baker labeled these three languages justice (opposition to despotism), reason (opposition to political views accepted because of their antiquity), and will (the right to implement enlightened concepts). The discourse of will approximated Furet’s notion of the role of equality and popular sovereignty. Yet Baker departed from Furet’s understanding of the way that ideology worked, adopting a more complex explanation for the creation of revolutionary ideology that included both chance and an alignment with material conditions. Nonetheless, Furet and Baker generally agreed on the important role of ideas or, more precisely, cultural change as a logic for revolution. 7

Continued work by Keith Baker, now collaborating with Dan Edelstein, remains highly visible, thanks in part to the impressive development of Stanford’s Digital Archive. 8 The architecture of the website springs from Edelstein’s and Baker’s priorities, which reflect their own understanding of the Revolution’s origins. Now, with a twenty-first century digital toolbox, Baker, Edelstein, and others at Stanford oversee technologists who are able to create algorithms that help scholars discover word associations, the building blocks for political discourse, on a far grander scale than what was possible even a few years ago. Still more important in extending their view of the power of ideas has been their new book Scripting Revolution , whose introduction confidently asserts that a revolution only assumes that form after being named a revolution. In practice, this theory implies that the French Revolution did not actually begin after the elections and the seizure of the Bastille in 1789 but instead only commenced later that year when Louis-Marie Prudhomme’s periodical Révolutions de Paris published a contemporary history of the events that labeled them revolutionary. Although Baker’s essay on the eighteenth-century use of the term “revolution” indicated the necessity of naming or “scripting,” he asserted this stronger point after Pierre Rétat pointed out Prudhomme’s essay. But what Rétat had begun in a fairly obscure article (that Baker carefully acknowledged and credited), Baker emphatically embraced and applied to all subsequent revolutions. In short, events called for the label; then, the label “revolution” defined subsequent actions. 9

Despite the significant achievements of Furet and Baker in reconceptualizing the intellectual origins of the Revolution, a new paradigm—classical republicanism—has exerted significant influence since 2000, at least in the English-speaking wing of the field. Baker would hardly contest this, it seems to me, since the convergence between the newer notion and his own arguments is considerable. In fact, he and his former student Johnson Kent Wright have done much to introduce this perspective to explain the French Revolution. 10 What neither they nor anyone else has provided is a standard definition of classical republicanism. For the purposes of this essay, one might assert that the essence of the term lies in the Greek and Roman defense of virtue and personal liberty against an empire. In the eighteenth century, according to this view, resistance fell to the nobility, which, motivated by honor, defended a populace that was itself only motivated by interest and largely incapable of taking up this necessary battle.

The ascendance of classical republicanism in accounts of the events of 1788–89 has tended to relegate the emphasis on natural rights (that Baker links to the language of “will”) to the subsequent radicalization of the Revolution. But this relationship was never quite settled, as Rousseau’s Social Contract advocated both republicanism and natural rights. Furthermore, advocates of classical republicanism also had their eye on equality, although they conceived of it more as the ennobling of all rather than leveling. In short, the equality born of natural law was minimized in 1788–89. Equality had proved difficult to accommodate consistently, much less realize, in the early part of revolutionary struggle driven by classical republicanism. 11

Worth noting as an aside is the prescience of two of the canonical works from a previous generation of scholars. Peter Gay clearly recognized the philosophes’ interest in the ancients but focused on their views that castigated religion, while Robert R. Palmer’s “intermediate bodies” are congruent with the resistance of elites, though clearly he imagined a social elite wider than the nobility of classical republicanism. 12

Evidence for how broad has been the reach of classical republicanism as an explanation for revolution are two distinguished studies in the related fields of fiscal policy and the economy. John Shovlin’s book, The Political Economy of Virtue details the debates beginning in the 1740 s between those who favored “virtuous” small producers over the wealthier, parasitic echelons of society. 13 His study depicts a battle between producers on one side and financiers and the comfortable on the other. Contemporaries believed that luxury and profit were derived from the exploitation of honest workers. Shovlin follows this division through the decades of the eighteenth century; though positions evolved, the rich and the oppressed remained opposed. To be sure, the author sometimes resorts to fancy footwork, as some entrepreneurial activities dropped by the rich and adopted by the poor apparently change from despicable to honored simply by virtue of who performed the work. He praises profit well earned by the hands of the poor and attacks that when the rich become the recipients.