Education in Africa

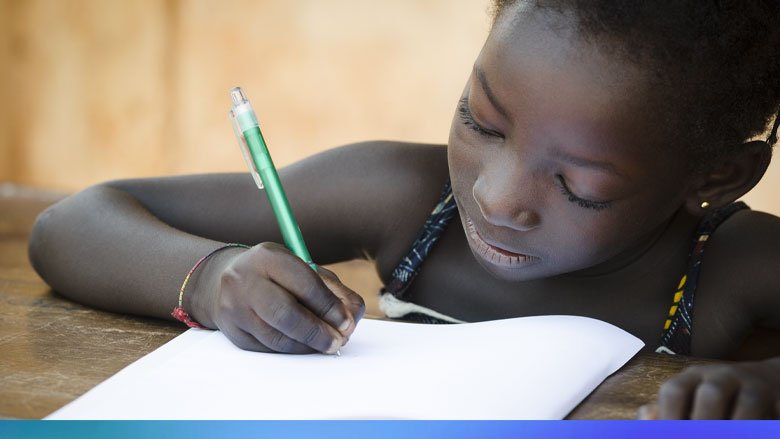

Sub-Saharan Africa has the fastest growing child population in the world. Yet, the current education system is at capacity, and the demand will increase with nearly 750 million children expected to be of school age by 2060. This rapid increase in cohorts of children and young people presents a significant fiscal pressure on governments in terms of service delivery needs, early childhood development interventions, and sustained investment in accessible and quality education for all, especially girls.

In 2024, the African Union is focused on the theme of education: “Educate an African fit for the 21st Century.” The World Bank’s work in support of the AU Year of Education will focus on four topics: Foundational Learning; Jobs and Skills; Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) and Higher Education; and Education Finance. Below is an overview of recent activities and stories in these key areas.

Foundational Learning

- Learning to read, reading to learn: Four lessons from Aprender+ in Mozambique

- Yearning for Learning: 7 Lessons from Western and Central Africa

Jobs and Skills

- Transforming education and skills development in Africa

- An Education in Poultry Farming for Nzingoula Delaunay

STEM and Higher Education

- Youth in Tanzania Reach for the Skies to Make Their Dreams in Aviation Come True

- Science High Schools in Burkina Faso: the cherished dreams of young scientists

Education Finance

- In Chad, proper schools are finally being built again in the Nya Pendé region

EDUCATION IN EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICA

EDUCATING YOUTH TO TRANSFORM WESTERN AND CENTRAL AFRICA

The World Bank and Education

The World Bank Group is the largest financier of education in the developing world, working in 90 countries and committed to helping them reach SDG4: access to inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030.

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Welcome to the United Nations

Africa grapples with huge disparities in education

Get monthly e-newsletter.

At the dawn of independence, incoming African leaders were quick to prioritize education on their development agendas. Attaining universal primary education, they maintained, would help postindependence Africa lift itself out of abject poverty.

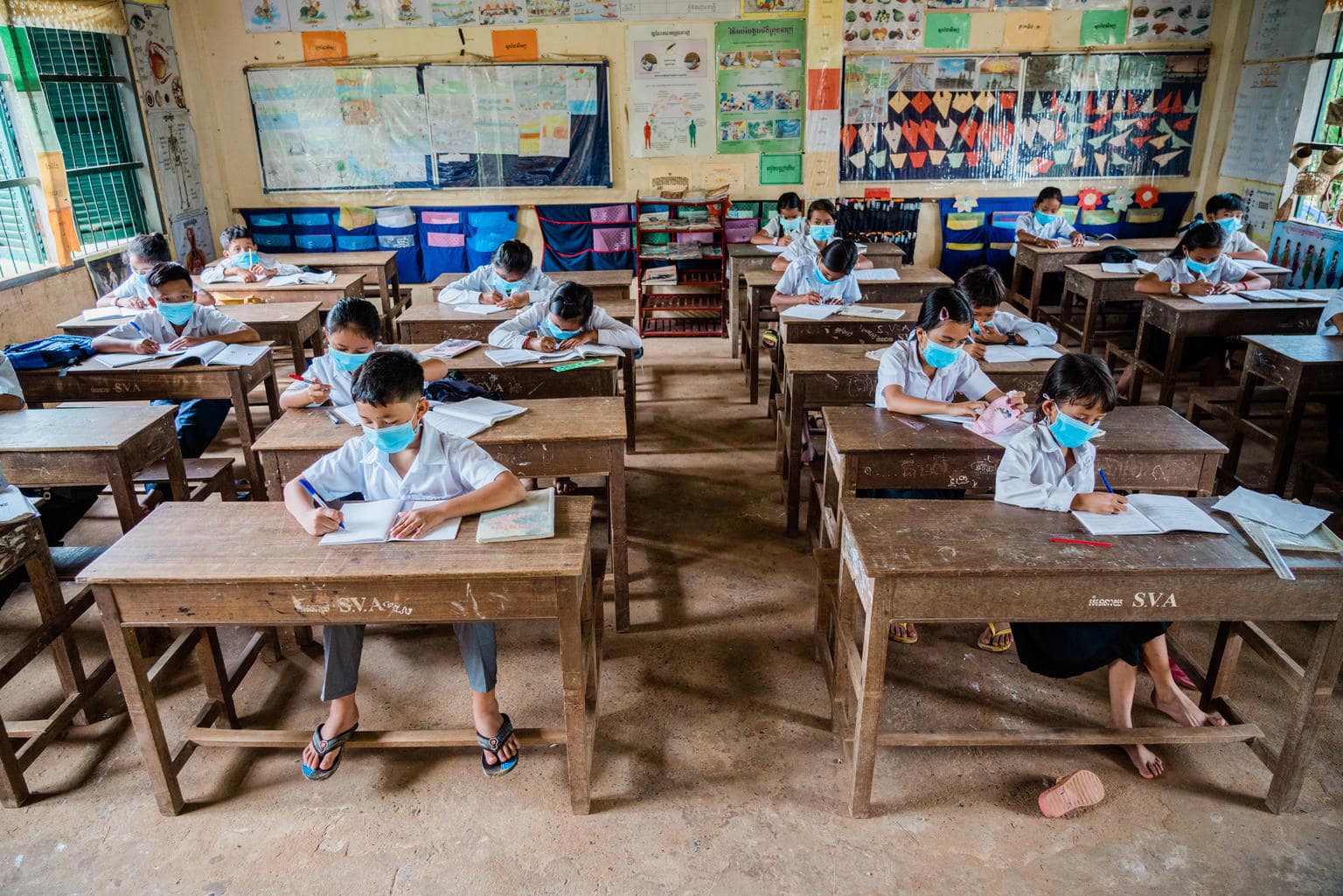

As governments began to build schools and post teachers even to the farthest corners of the continent, with help from religious organizations and other partners, children began to fill the classrooms and basic education was under way.

Africa’s current primary school enrolment rate is above 80% on average, with the continent recording some of the biggest increases in elementary school enrolment globally in the last few decades, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which is tasked with coordinating international cooperation in education, science, culture and communication. More children in Africa are going to school than ever before.

Yet despite the successes in primary school enrolment, inequalities and inefficiencies remain in this critical sector.

According to the African Union (AU), the recent expansion in enrolments “masks huge disparities and system dysfunctionalities and inefficiencies” in education subsectors such as preprimary, technical, vocational and informal education, which are severely underdeveloped.

It is widely accepted that most of Africa’s education and training programs suffer from low-quality teaching and learning, as well as inequalities and exclusion at all levels. Even with a substantial increase in the number of children with access to basic education, a large number still remain out of school.

A newly released report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Income Inequality Trends in sub-Saharan Africa: Divergence, Determinants and Consequences, identifies the unequal distribution of essential facilities, such as schools, as one the drivers of wide income disparities.

Ayodele Odusola, the lead editor of the report and UNDP’s chief economist, makes the following point: “Quality education is key to social mobility and can thus help reduce poverty, although it may not necessarily reduce [income] inequality.”

To address education inequality, he says, governments must invest heavily in child and youth development through appropriate education and health policies and programmes.

Higher-quality education, he says, improves the distribution of skilled workers, and state authorities can use this increased supply to build a fairer society in which all people, rich or poor, have equal opportunities. As it is now, only the elites benefit from quality education.

“Wealthy leaders in Africa send their children to study in the best universities abroad, such as Harvard. After studies, they come back to rule their countries, while those from poor families who went to public schools would be lucky to get a job even in the public sector,” notes Mr. Odusola.

Another challenge facing policy makers and pedagogues is low secondary and tertiary enrolment. Angela Lusigi, one of the authors of the UNDP report, says that while Africa has made significant advances in closing the gap in primary-level enrolments, both secondary and tertiary enrolments lag behind. Only four out of every 100 children in Africa is expected to enter a graduate and postgraduate institution, compared to 36 out of 100 in Latin America and 14 out of 100 in South and West Asia.

“In fact, only 30 to 50% of secondary-school-aged children are attending school, while only 7 to 23% of tertiary-school-aged youth are enrolled. This varies by subregion, with the lowest levels being in Central and Eastern Africa and the highest enrolment levels in Southern and North Africa,” Ms. Lusigi, who is also the strategic advisor for UNDP Africa, told Africa Renewal.

According to Ms. Lusigi, many factors account for the low transition from primary to secondary and tertiary education. The first is limited household incomes, which limit children’s access to education. A lack of government investment to create equal access to education also plays a part.

“The big push that led to much higher primary enrolment in Africa was subsidized schooling financed by both public resources and development assistance,” she said. “This has not yet transitioned to providing free access to secondary- and tertiary-level education.”

Another barrier to advancing from primary to secondary education is the inability of national institutions in Africa to ensure equity across geographical and gender boundaries. Disabled children are particularly disadvantaged.

“Often in Africa, decisions to educate children are made within the context of discriminatory social institutions and cultural norms that may prevent young girls or boys from attending school,” says Ms. Lusigi.

Regarding gender equality in education, large gaps exist in access, learning achievement and advanced studies, most often at the expense of girls, although in some regions boys may be the ones at a disadvantage.

UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics reports that more girls than boys remain out of school in sub-Saharan Africa, where a girl can expect to receive only about nine years of schooling while boys can expect 10 years (including some time spent repeating classes).

More girls than boys drop out of school before completing secondary or tertiary education in Africa. Globally, women account for two-thirds of the 750 million adults without basic literacy skills.

Then there is the additional challenge of Africa’s poorly resourced education systems, the difficulties ranging from the lack of basic school infrastructure to poor-quality instruction. According to the Learning Barometer of the Brookings Institution, a US-based think tank, up to 50% of the students in some countries are not learning effectively.

Results from regional assessments by the UN indicate “poor learning outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa, despite upward trend in average learning achievements.” Many children who are currently in school will not learn enough to acquire the basic skills needed to lead successful and productive lives. Some will leave school without a basic grasp of reading and mathematics.

The drivers of inequality in education are many and complex, yet the response to these challenges revolves around simple and sound policies for inclusive growth, the eradication of poverty and exclusion, increased investment in education and human development, and good governance to ensure a fairer distribution of assets.

With an estimated 364 million Africans between the ages of 15 and 35, the continent has the world’s youngest population, which offers an immense opportunity for investing in the next generation of African leaders and entrepreneurs. Countries can start to build and upgrade education facilities and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all.

The AU, keeping in mind that the continent’s population will double in the next 25 years, is seeking through its Continental Education Strategy for Africa 2016–2025 to expand access not just to quality education, but also to education that is relevant to the needs of the continent.

The AU Commission deputy chairperson, Thomas Kwesi Quartey, says governments must address the need for good education and appropriate skills training to stem rising unemployment.

Institutions of higher learning in Africa, he says, need to review and diversify their systems of education and expand the level of skills to make themselves relevant to the demands of the labour market.

“Our institutions are churning out thousands of graduates each year, but these graduates cannot find jobs because the education systems are traditionally focused on preparing graduates for white-collar jobs, with little regard to the demands of the private sector, for innovation or entrepreneurship,” said Mr. Quartey during the opening of the European Union–Africa Business Forum in Brussels, Belgium, in June 2017.

He noted that if African youths are not adequately prepared for the job market, “Growth in technical fields that support industrialization, manufacturing and development in the value chains will remain stunted.” Inequality’s inclusion among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities) serves as an important reminder to leaders in Africa to take the issue seriously.

For a start, access to early childhood development programmes, especially for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, can help reduce inequality by ensuring that all children begin formal schooling with strong foundations.

The UNDP, through its new strategic plan (for 2018 through 2021), will work to deliver development solutions for diverse contexts and a range of development priorities, including poverty eradication, jobs and livelihoods, governance and institutional capacity and disaster preparedness and management.

Also in this issue

Combating Africa’s inequalities

Young African women turn to coding

Closing Africa’s wealth gap

Corporate boardrooms: where are the women?

Tackling inequality by ‘lifting stones’

Digital revolution holds bright promises for Africa

Protectionist ban on imported used clothing

New Africa-wide initiative will create jobs

UN-AU decry absence of women in crucial peacebuilding activities

A visa-free Africa still facing hurdles

Ending albino persecution in Africa

African solutions urgently sought for agricultural revolution

Towards a food-secure africa.

Forgotten war: a crisis deepens in Libya but where are the cameras?

Thriving societies need social cohesion, justice and inclusion — Ms. Nell Bolton

Elite Kenyan marathoner championing battle against Gender-Based Violence

More from africa renewal.

Using the creatives to boost intra-African trade

We use cookies. Read more about them in our Privacy Policy.

- Accept site cookies

- Reject site cookies

Search results:

- Afghanistan

- American Samoa

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Bolivia (Plurinational State of)

- Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- British Virgin Islands

- Brunei Darussalam

- Burkina Faso

- Cayman Islands

- Central African Republic

- Channel Islands

- China, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- China, Macao Special Administrative Region

- China, Taiwan Province of China

- Cook Islands

- Côte d'Ivoire

- Democratic People's Republic of Korea

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Dominican Republic

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Falkland Islands (Malvinas)

- Faroe Islands

- French Guiana

- French Polynesia

- Guinea-Bissau

- Humanitarian Action Countries

- Iran (Islamic Republic of)

- Isle of Man

- Kosovo (UNSCR 1244)

- Lao People's Democratic Republic

- Liechtenstein

- Marshall Islands

- Micronesia (Federated States of)

- Netherlands (Kingdom of the)

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- North Macedonia

- Northern Mariana Islands

- OECD Fragile Contexts

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

- Republic of Korea

- Republic of Moldova

- Russian Federation

- Saint Barthélemy

- Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Saint Lucia

- Saint Martin (French part)

- Saint Pierre and Miquelon

- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- Sint Maarten

- Solomon Islands

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- State of Palestine

- Switzerland

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Timor-Leste

- Trinidad and Tobago

- Turkmenistan

- Turks and Caicos Islands

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United Republic of Tanzania

- United States

- Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)

- Virgin Islands U.S.

- Wallis and Futuna

Search countries

Search for data in 238 countries

- SDG Progress Data

- Child Marriage

- Immunization

- Benchmarking child-related SDGs

- Maternal and Newborn Health Disparities

- Continuity of essential health services

- Country profiles

- Interactive data visualizations

- Journal articles

- Publications

- Data Warehouse

Education overview

- Current status

- Available data

- Recent resources

- Notes on the data

Education is vital to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals

Every child learns. The Sustainable Development Goals are interdependent and achieving SDG4 – ensuring inclusive and equitable education for all by 2030 – will have transformative effects on other goals. SDG4 spans a spectrum of education levels, from pre-primary to youth and adult education. It emphasizes learning outcomes, skills acquisition, and equity in both development and emergency settings. UNICEF advocates high-quality, child-friendly basic education for all, in line with the ambition of the Global Education 2030 Agenda. To meet the vision brought forth by the Education 2030 Framework of Action and SDG4, UNICEF released its own Education Strategy 2019–2030 , ‘Every Child Learns’, outlining three distinct goals: (1) Equitable access to learning opportunities; (2) Improved learning and skills for all; and (3) Improved learning and protection for children in emergencies and fragile contexts.

Education data

Are children really learning exploring foundational skills in the midst of a learning crisis.

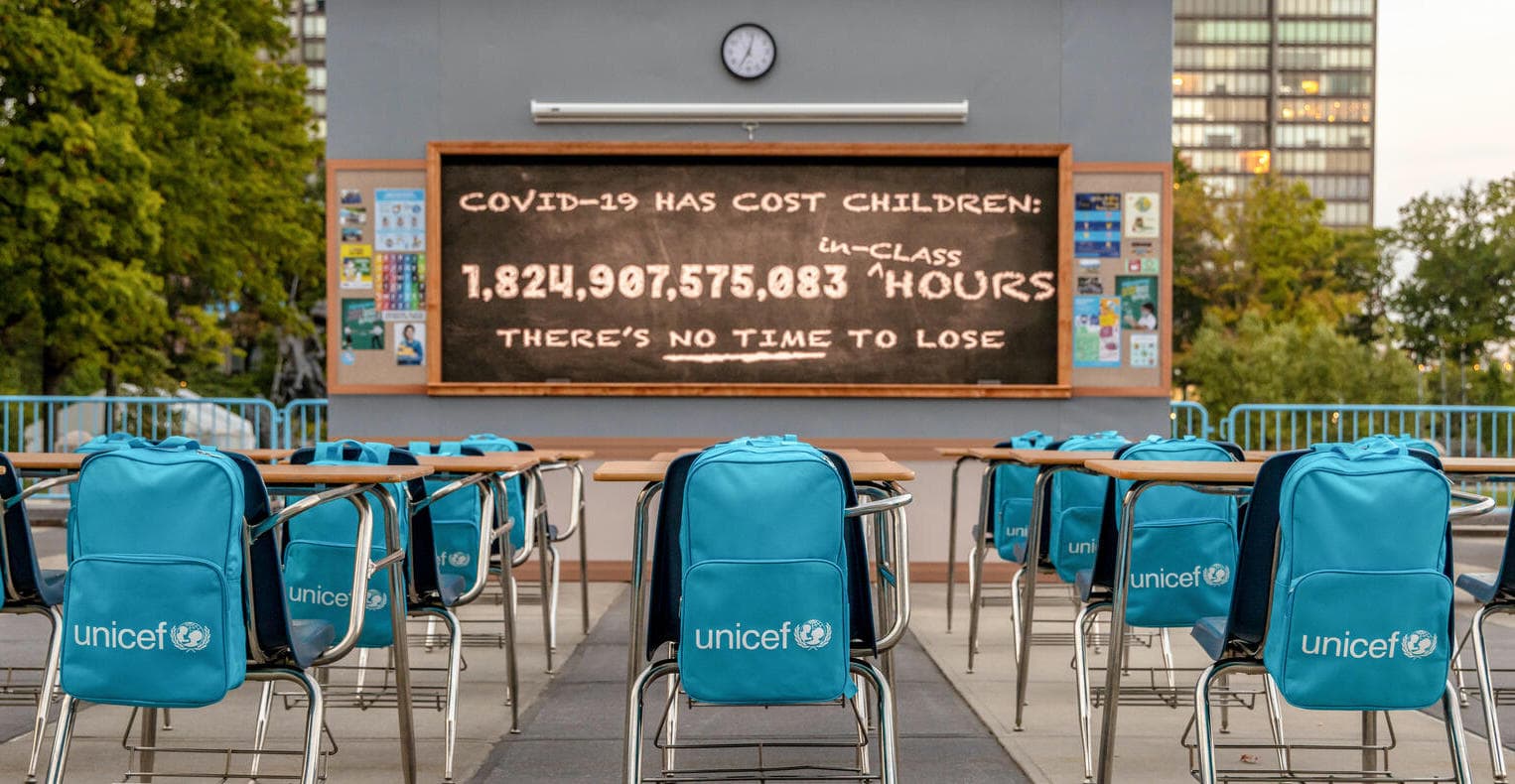

The State of Global Education: From crisis to recovery

Education for children with disabilities

Ensuring equal access to education in future crises: Findings of the new Remote Learning Readiness Index

Education disrupted: The second year of the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures

How are children progressing through school? An Education Pathway Analysis

Which children have internet access at home? Insights from household survey data (blog post)

How many children and young people have internet access at home?

Georgia education fact sheets

What Have We Learnt? Findings from a survey of ministries of education on national responses to COVID-19

EduView Dashboard

COVID-19: Are children able to continue learning during school closures?

Promising practices for equitable remote learning: Emerging lessons from COVID-19 education responses in 127 countries

Guidelines for adapting the Foundational Learning Module to non-multiple indicator cluster household surveys

MICS – Education Analysis for Global Learning and Equity

A Future Stolen: Young and out-of-school

Fixing the Broken Promise of Education for All – Findings from the Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children

Suriname education fact sheets

UNICEF strategic plan country and regional education profiles

Lao PDR education country report

Notes on the Data

Definition of indicators.

Gender parity index – The ratio of female-to-male values of a given indicator. A GPI of 1 indicates parity between the sexes.

Literacy rate – Total number of literate persons in a given age group, expressed as a percentage of the total population in that age group. The adult literacy rate measures literacy among persons aged 15 years and older, and the youth literacy rate measures literacy among persons aged 15 to 24 years.

Out-of-school population – Total number of primary or lower secondary-school-age children who are not enrolled in primary (ISCED 1) or secondary (ISCED 2 and 3) education.

Pre-primary school gross enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in pre-primary school, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official pre-primary school age.

Primary school gross enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in primary school, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official primary school age.

Primary school net attendance ratio – Number of children attending primary or secondary school who are of official primary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official primary school age. Because of the inclusion of primary-school-age children attending secondary school, this indicator can also be referred to as a primary adjusted net attendance ratio.

Primary school net enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in primary or secondary school who are of official primary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official primary school age. Because of the inclusion of primary-school-age children enrolled in secondary school, this indicator can also be referred to as a primary adjusted net enrolment ratio.

Secondary school net attendance ratio – Number of children attending secondary or tertiary school who are of official secondary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official secondary school age. Because of the inclusion of secondary-school-age children attending tertiary school, this indicator can also be referred to as a secondary adjusted net attendance ratio.

Secondary school net enrolment ratio – Number of children enrolled in secondary school who are of official secondary school age, expressed as a percentage of the total number of children of official secondary school age. Secondary net enrolment ratio does not include secondary-school-age children enrolled in tertiary education, owing to challenges in age reporting and recording at that level.

Survival rate to last primary grade – Percentage of children entering the first grade of primary school who eventually reach the last grade of primary school.

Related Topics

- Pre-primary education

- Primary education

- Secondary education

- Learning and skills

- Remote learning and digital connectivity

Join our community

Receive the latest updates from the UNICEF Data team

- Don’t miss out on our latest data

- Get insights based on your interests

The dataset you are about to download is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license.

Improving access to quality public education in Africa

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, rebecca winthrop rebecca winthrop director - center for universal education , senior fellow - global economy and development @rebeccawinthrop.

February 11, 2022

- 19 min read

On February 8, 2022, Rebecca Winthrop testified before the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee. Her written testimony on improving access to quality public education in Africa follows. View the full hearing .

Chairwoman Bass, Vice Chairwoman Omar, Ranking Member Smith, and other distinguished members of the subcommittee, thank you for inviting me to testify today on the importance of and path forward for helping all of Africa’s children and youth get the century education they deserve. This topic is one that I am deeply committed to advancing however I can, and today I will share my insights both as a former practitioner working on education initiatives across sub-Saharan Africa and as a current scholar at the Brookings Institution working on global education issues. My colleague, Emiliana Vegas, and I co-direct the Center for Universal Education at Brookings where our team currently focuses on addressing education inequality in countries around the world, including through working closely with 35 African partners from national governments to nonprofit organizations across 21 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Our work is also heavily informed by our team of Echidna Global Scholars who are girls’ education leaders around the globe, including 12 scholars leading work on gender equality in education in six countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

As the committee is already well aware, ensuring all Africa’s children and youth have high-quality education opportunities that prepare them for the 21st century world we live in is not only the right thing to do — children everywhere have a right to a quality education — but is also the smart thing to do. It falls squarely within four overarching buckets central to the U.S. government’s (USG) strategic interests.

- The growth in the world’s labor market is in Africa. As other parts of the world begin to age, Africa will grow its population and today’s children will be the talent tomorrow’s global companies will be recruiting. In the next 30 years, it is projected that sub-Saharan Africa’s working-age population will increase more than twofold—accounting for 68 percent of the world’s total growth . Economists have shown that when controlling for other factors, increasing girls’ and boys’ years of schooling (and the skills they learn while there) has a positive effect on economic growth. Ensuring girls’ secondary education is particularly impactful. Providing high-quality education today will help build the skills for the world’s future workforce, increase incomes, grow economies, and expand U.S. markets and trading partners.

- Providing education equitably across a country’s population can reduce the risk of violent conflict. Especially in countries with large youth populations, equitable education provisions can support political stability by sending the signal that the government is attending to people’s needs and giving people more tools to resolve disputes peacefully. This “pacifying effect” of education, as conflict researchers often refer to it, can help reduce the risk of civil war and the growth of ungovernable territories and safe havens for violent extremism. Ultimately, it helps promote the safety and security of the U.S.

- Global health. Educated girls and women can better seek and negotiate life-saving health care for themselves and their children. Global studies have shown increased education—particularly for girls—leads to less infant deaths, less maternal mortality, and less infection from viruses (HIV/AIDs). The evidence is so strong for girls’ education that some health researchers call it a “social vaccine.” Healthier communities mean less strains on health systems, a particularly timely interest of the U.S. given the global COVID-19 pandemic.

- Climate change. Increased levels of education support communities’ resilience in the face of climate change and can help reduce communities’ carbon footprints by leading to smaller, more sustainable families. Educating and empowering women can decrease death rates and displacement due to weather-related disasters, and could result in an estimated 85 gigaton reduction of carbon dioxide by 2050, which is not only in the U.S.’s interest, but the world’s.

Given the importance of educating Africa’s children and youth, I would urge the committee to bolster USG attention, funding, and support to increase access to quality education. I offer the below four recommendations for the committee to consider as possible ways to do this.

Recommendation 1: Harness the innovative capacity of African communities

Across the continent, African communities are innovating to solve their problems, often with very little resources. With limited access to physical banks, in Kenya a cellphone company started a global revolution in personal finance (and financial inclusion) in 2007 by inventing mobile money . This idea of “a bank in your pocket” accessed through personal cell phones has spread rapidly across the world. In 2021, Nollywood—Africa’s Hollywood—was the second most prolific film industry in the world. Started less than two decades ago by Kenneth Nnebue with frugal, straight to VHS films, Africa’s film industry is now giving America’s century-old film industry a run for its money. In South Africa, farmers are optimizing their agriculture practices with the help of a platform that combines satellite, drone, and artificial intelligence technology. Today’s innovators are standing on the shoulders of a long line of cutting-edge creatives as Africa’s history demonstrates.

All too often in the U.S., the dire news headlines about Africa obscure the ingenuity and innovative capacity of African communities. Focusing solely on the great needs of communities, without simultaneously recognizing their tremendous assets to solve problems, can create a hard-to-see but nonetheless dangerous mindset that Africans cannot be true partners in the identification and design of solutions to problems the USG is interested in addressing.

Related Content

Rebecca Winthrop, Adam Barton, Mahsa Ershadi, Lauren Ziegler

September 30, 2021

David Istance, Alejandro Paniagua, Rebecca Winthrop, Lauren Ziegler

September 19, 2019

Rebecca Winthrop

July 14, 2020

The U.S. Government Strategy on International and Basic Education established in 2019 provides a welcome shift in focusing on partnerships and local ownership. This is one important part of the strategy that should be continued and strengthened. For example, USAID funding has traditionally gone mainly to U.S.-based organizations that have deep technical expertise, excellent administrative capabilities, and sophisticated know-how on navigating USG procurement processes. Often these U.S. organizations will sub-grant to local nonprofits, universities, or networks once a grant is awarded to help implement a specific set of activities. Recently however, especially with the guidance of the Government Strategy on International and Basic Education, USAID is awarding more grants directly to local organizations, beginning to involve local organizations in discussions about the design of programs, and—in a handful of cases—the usual relationship between U.S. and local organizations has been flipped (the local organization is the lead or “prime” and the U.S. organization is its subgrantee).

This increased participation of local actors is not only important to enhance local “ownership” and “sustainability” of USG-funded projects, which is the main rationale in the strategy, but also to harness the creative ideas local organizations and communities can bring to solving some of their most pressing problems. At the Center for Universal Education at Brookings, one of my areas of focus has been on bottom-up innovation and examining the potential it has to help accelerate, or leapfrog, the pace at which education is improving. Having conducted a review of over 3,000 education innovations across 160 countries in my study—” Leapfrogging Inequality: Remaking Education to Help Young People Thrive ” — we found a dynamic innovation sector in every corner of the globe. Of the countries with the most innovations, 1 in 4 were in Africa. Many innovations have the potential to radically bend the curve and close the “100-year-gap,” which is the estimated time it will take (prior to COVID) for the most marginalized African children to catch up in terms of education outcomes with their more enfranchised peers. However, most innovations occurred on the margins of education systems and are hampered by limited attention, funding, and organizational support.

Across its education work in Africa, the USG policy directives, agency strategies, and operations would do well to not only tap into this innovative capacity within African communities, but understand and support the conditions that would help unleash its potential. This is both a mindset and an implementation approach that should be embraced across whatever thematic priorities the USG is investing in. Below are two specific examples of actions the USG could take to support this direction:

- In its ongoing bilateral support for education in Africa, the USG should continue the work of increasingly co-designing and directly supporting local organizations. The many U.S.-based organizations working on education in Africa have many talented and thoughtful team members who should be tapped for their expertise, but they should not be the only ones at the table helping design USG programs nor the only ones leading implementation. As a neutral convener of global education policy debates, we frequently get requests from our African partners, including government officials, to help brainstorm ideas on how to tackle a particular problem “free from the difficulties of managing the priorities of multiple donors” as one partner put it. One concrete way for the USG to advance this is to invest in a design-thinking process with African partners at the center and multiple actors from across a range of disciplines assisting in brainstorming how to “leapfrog” or rapidly accelerate progress in addressing a particular problem (e.g., low literacy levels or high youth unemployment). Systematically supporting “ leapfrog labs ,” a virtual space to conduct this process, could be one way to deepen USG’s work in this area.

- The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) is the largest global fund dedicated to improving education primarily in low-income countries. With work in over 40 African partner countries, GPE puts country voices at the center of its model by supporting ministries of education to develop strong policies building on inclusive consultation with local and international organizations. Ministers of education in Africa and countries around the world have called on GPE to “shift from business as usual” and are keenly interested in strategies that can accelerate the pace of change and ensure “our collective efforts transform the teaching and learning experience.” Supporting this call to action through increased funding to GPE is another concrete way to move this work forward. Currently, the USG gives $125 million annually to GPE, a far cry from the over $1.5 billion annual contribution the USG gives to the global fund for health.

Recommendation 2: Support enriched teaching and learning experiences to improve foundational literacy and numeracy

Africa’s young children are failing to master basic literacy and numeracy skills, which are crucial if they hope to have any longevity in their educational journeys. It is very difficult to explore and master the diverse curricular subjects from history to science that are required as children progress through school without strong reading abilities and foundational understanding of mathematics. According to UNESCO’s recent Global Education Monitoring Report , only 18 percent of all primary-school age children in sub-Saharan Africa achieve minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics, many of whom are enrolled in school. The World Bank and UNESCO Institute of Statistics are tracking this crisis through their work on “ learning poverty ,” which is defined as those children in school who cannot read by age 10, together with those children out-of-school whom they assume cannot read. The organizations argue that if children do not master reading by age 10, they are unlikely to do so later in life.

The USG has over the last decade invested heavily in addressing this “learning crisis,” including developing internal staff capacity and international partner collaboration. The needs in this area are so great that the USG should continue to support partners to address foundational literacy and numeracy. A mix of approaches will be needed to address this challenge given that approaches for stable contexts will not be the same needed for situations of instability. With the COVID-19 pandemic, rising levels of conflict, and increasing climate related disasters, a nimble approach to adapting strategies should be fostered across all USG agencies working on education.

Related Books

Rebecca Winthrop Adam Barton, Eileen McGivney

June 5, 2018

In contexts where children are regularly attending school, the focus should be on the classroom-based teaching and learning strategies that have been shown to be effective and able to scale . For example, one cost-effective approach is Teaching at the Right Level which uses differentiated instruction (grouping students by level rather than grade) and interactive pedagogical methods to improve student learning outcomes. Pioneered in India by the nonprofit Pratham, this has also been shown to be effective in Africa. One rigorous study in Kenya demonstrated that dividing classrooms into groups based on students’ learning level increased test scores for all students .

There are many children however who need different approaches, largely because they are not able to access stable schooling provisions either because they are out of school or live in contexts of conflict or instability, which is a situation only exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report, only two of three children in sub-Saharan Africa who enter primary school complete it. UNICEF estimates that in the region nearly 250 million children were affected by pandemic related school closures, on top of the approximately 100 million children out of school before the pandemic, approximately 40 million of whom are of primary-school age. Additionally, 14 African countries are on the World Bank’s most recent list of fragile and conflict affected situations as experiencing at least medium intensity conflict.

In these contexts, it is important to consider flexible approaches to improving foundational literacy and numeracy. One approach is to use accelerated learning programs that help children who have missed several years of schooling catch-up and re-enter school. One example of this type of program is the Luminos Fund’s Second Chance program focused on out-of-school children ages 8-14 in Ethiopia and Liberia. Young adults from the students’ communities are recruited and trained to lead a program where students learn literacy and numeracy through interactive, activity-based approaches. The program covers the first three years of school in 10-months after which time students enter primary school. A longitudinal evaluation found that that this form of “catch-up” learning is far from being a handicap for students but rather an asset. Students in the Second Chance program complete primary school at a rate that is nearly double that of government students, they outperform their peers in English and math, are happier and more confident, and have higher aspiration to continue their education beyond the primary years.

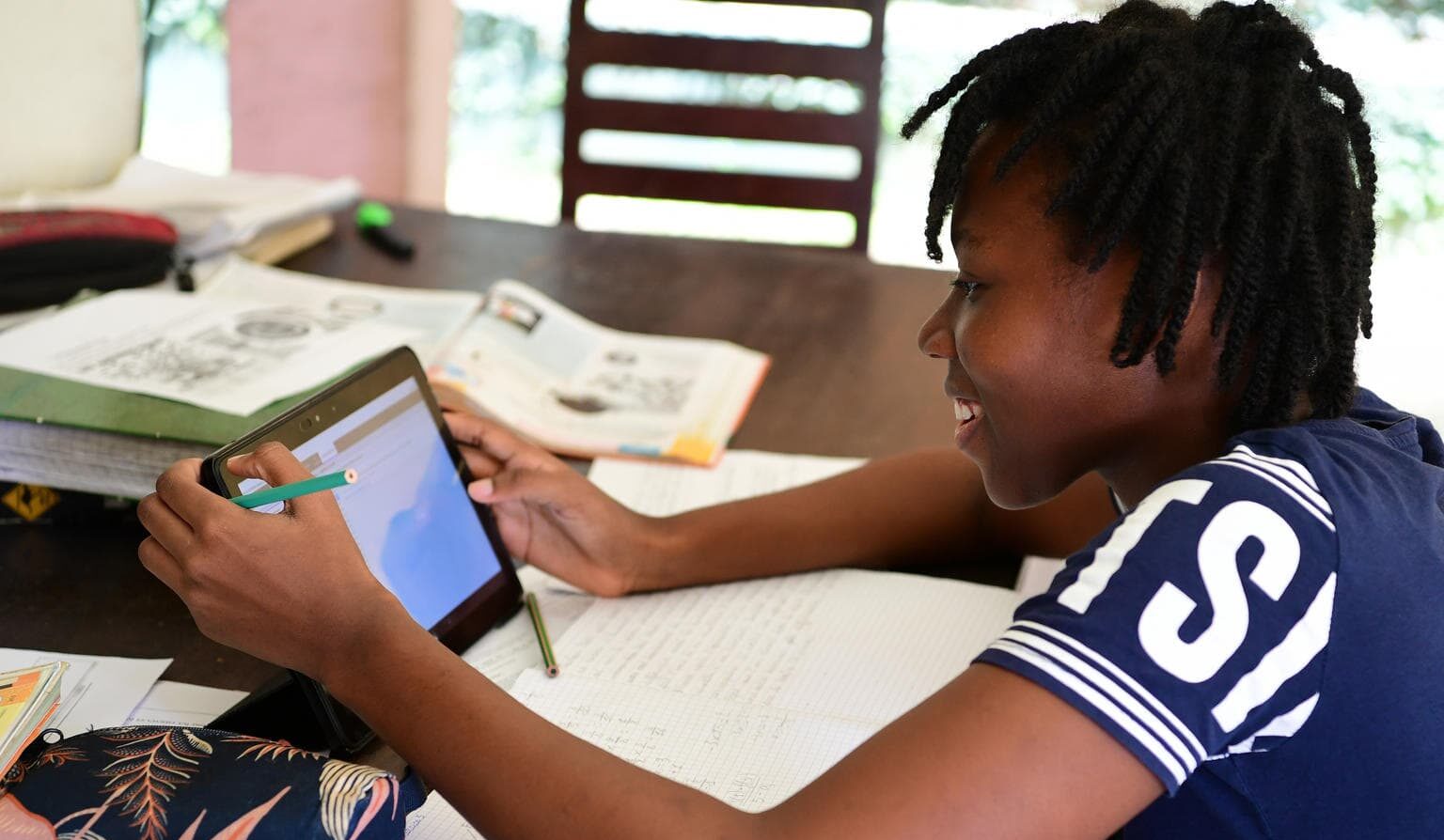

Some flexible learning approaches also have the potential to support children’s literacy and numeracy learning in diverse situations from in and out of school. The teacher shortage in sub-Saharan Africa is acute with an estimated 15 million more teachers needed. Unwieldly class sizes and limited teaching time due to teacher absenteeism, which remains high , requires innovative learning approaches in the short- to medium-term while systems strengthen their human resources recruitment, training, support, and deployment. One promising example of a foundational learning strategy that could “face both ways” for in and out-of-school children is technology-enabled, child-directed personalized learning. Most technology-based learning programs require students to have a certain level of basic literacy. One exception is the X-prize winners onebillion and KitKit School that have helped young children build literacy and numeracy skills starting from zero via solar powered tablets. In a collaboration with the government of Malawi and their partner VSO, the scaling nonprofit Imagine Worldwide is testing the effectiveness of supporting foundational learning in schools with severely overcrowded classrooms. With 40 minutes a day of learning on the tablet, an initial randomized control trial found significant positive effects on overall gains in literacy and numeracy translating to 5.3 months of additional literacy learning.

Across all these contexts, whether children are in or out of school, the global education community has been increasingly paying attention to the important role of families in children’s educational success. In the Center for Universal Education’s recent work “ Collaborating to improve and transform education systems: A playbook for family school engagement ,” we found a number of creative family engagement strategies with strong evidence showing the positive effects on children’s learning. From building community literacy skills and habits that support children’s learning outside of school to SMS messages to caregivers for math practice with their children at home, there are many innovative approaches deployed in African communities. Some approaches, such as improving family-school communication on the benefits of education, are highly cost-effective in helping improve student learning outcomes due to their ability to be implemented at wide scale. The COVID-19 pandemic and the likely growing instability facing many African communities makes strengthening family-school engagement no longer a nice-to-have but a crucial component of supporting children’s learning.

Recommendation 3: Increase investments in improved models of learning that prepare African youth for the future of work

Africa is the youngest continent in the world and for many young people a quality, traditional secondary education can be difficult to come by. In sub-Saharan Africa before the pandemic, of the 98 percent of children who enroll in primary school, only 9 percent make it to tertiary education and only 6 percent graduate. University preparation is important, but the main focus should be on flexible secondary education pathways that prepare young people for work. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the struggle of young people continuing their education.

Demands for secondary education have grown in the region following the large push with the Millennium Development Goals for universal primary completion. This is a particular concern for the countries housing the largest numbers of young people. In 2020, almost half of poor people in sub-Saharan Africa lived in just five economies : Nigeria (79 million), the Democratic Republic of Congo (60 million), Tanzania (28 million), Ethiopia (26 million), and Madagascar (20 million). Serious investments must be made to deliver on these demands. According to the Education Commission, sub-Saharan Africa needs to invest $175 billion per year through 2050 to support secondary education for all. This is a far cry from the $25 billion that was invested in secondary education in 2015.

Crucially, these investments must not come at the expense of continuing to support and strengthen primary education. Inclusive and equitable education systems must be built on a strong early learning foundation, otherwise it will be the most well-off young people who continue to access secondary education and leave their most marginalized peers behind.

This is an area that needs significant attention and it is a gap in the USG’s education work globally. Currently, initiatives on workforce training for out-of-school youth reach only small numbers and frequently are costly , and would not be sufficient for responding to the demand for secondary education. Instead what is needed is a reinvention of secondary education itself. Multiple, flexible pathways so that young people who drop out may have on-roads to re-enter will be crucial. Many Africans are already experimenting with reinventing secondary education. For example, the Ministry of Education in Ghana is deploying a year-round, two-shift schooling approach to accommodate the large numbers of secondary school students interested in the limited seats in physical school buildings. A South Africa program is partnering secondary schools in marginalized communities with companies struggling to hire employees. A Nigerian early-stage venture capital firm is betting on African education innovation and has started a Future of Learning Fund to seed the private sector education entrepreneurs.

Crowding in investment, innovative ideas, new actors, and robust partnerships to help African youths choose from multiple secondary education learning models could be an important role the USG could play. This is an area that is particularly well suited to public-private partnerships. The whole of USG Strategy on International and Basic Education lends itself well to this work given the wide range of agencies with diverse expertise, tools, and networks that could be deployed. Mobilizing U.S. private sector actors could be one way of greatly expanding the existing USG work on this topic.

Recommendation 4: Lead on system transformation in the face of climate change

Globally, the education sector is just beginning to grapple with what a resilient, climate-smart education system looks like. Finding ways to support flexible, adaptive education ecosystems that are resilient in the face of climate impacts and help spur climate action is something countries around the world will increasingly struggle with.

Already communities across sub-Saharan Africa are facing the climate related impacts on education. Climate change and its associated impact on weather and climate patterns widens inequality gaps in sub-Saharan Africa . Floods, droughts, fires, heat spells, and heavy rain can lead to destruction of school buildings, roads, and bridges; reduce access to sanitation and food supplies; and contribute to the spread of vector borne diseases— all of which can impact school attendance rates, performance outcomes, and dropout rates . Disruptive weather events disproportionately affect girls and young women around the globe, particularly in low-income countries, who are often forced out of school due to damaged infrastructure or other reasons. According to estimates from the Malala Fund, by 2025 more than 12 million girls will be at risk of not completing their education every year as a result of climate change .

The USG has done some initial work in this area, particularly on disaster risk reduction, but it could play a much bigger role and exert real leadership in this area. Developing climate-smart education systems are cross-cutting endeavors. For example, supporting foundational literacy and numeracy materials that speak to topics in environmental education and youth post-primary education focused on green economy jobs. There is increasing demand from students, teachers, and communities to incorporate climate change education and political windows of opportunity with the first international agreement between Ministers of Education and Ministers of the Environment to collaborate to prioritize climate change education coming out of COP26.

High-quality climate change education has the power to spur climate action, but to date the education sector has not been at the table as a partner in climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. Globally, less than 25 percent of countries’ national plans to address climate change mention the education of children and youth. There are, however, effective approaches to build on to advance this work. In “ Unleashing the creativity of teachers and students to combat climate change ,” my co-author Christina Kwauk and I highlight a range of practices including climate action projects at schools that both help build community resilience, deepen students’ science learning, and allow them to practice applying academic knowledge to solve problems in the real world.

In conclusion, I urge the USG to renew the whole of USG Strategy on International and Basic Education when it expires in 2023 with attention to the above four recommendations. In 2010, I published a report titled “ Punching Below Its Weight: The U.S. Government Approach to Education in the Developing World .” The title was in part in reference to the 13 USG agencies I found working on education in the developing world with very little coordination and collaboration. The Strategy on International and Basic Education has finally helped address this by providing the policy support needed for agencies to collaborate, and there are good examples of the synergies that have resulted (e.g., CDC training developing country ministries of education on COVID-19 information). A renewed whole of government strategy that brings additional funding, expertise, and networks to supporting education in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the areas above, would be one that truly punches above its weight.

Education Access & Equity Global Education

Global Economy and Development

Middle East & North Africa South Africa Sub-Saharan Africa West Africa

Center for Universal Education

Sopiko Beriashvili, Michael Trucano

April 26, 2024

Michael Trucano, Sopiko Beriashvili

April 25, 2024

Online only

9:00 am - 10:00 am EDT

- Skip to content

- Skip to main menu

- Skip to more DW sites

Why education remains a challenge in Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rate of education exclusion globally, according to the UN. Nearly 60% of youth aged 15 to 17 are not in school. Activists on the continent are now fighting to change that.

Education is considered a universal human right, as well as an issue of public good and responsibility. However, there are still many — particularly children in developing African countries — who do not enjoy this right.

As the world marks the fourth International Day of Education under the theme "Changing Course, Transforming Education," The United Nations (UN) is calling for action.

In many African nations, those who can afford education send their children to private schools in the city. But that is not an option for many in rural areas, or for poorer families.

According to the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), over one-fifth of African children between the ages of 6 and 11 are not in school, while nearly 60% of youth between the ages of 15 and 17 are not enrolled.

The education of girls is of particular concern: 9 million girls on the continent between the ages of 6 and 11 will never attend school, compared to 6 million boys. By the time they reach adolescence, girls have a 36% exclusion rate compared to 32% for boys.

Many obstacles to learning

It is still common in many areas to find children on farms or playing on the streets instead of attending school.

Some countries lack proper school structures, and many are dilapidated.

"There are no toilets, desks, or even chairs in my school," Umaru Harisa, a primary school student in Nigeria, told DW. He also complained that his school is very far from his home.

"I think our teachers are dedicated, but it's very hard to learn with nothing to help us," he said.

Differing attitudes towards the value of formal education is another major problem. Skepticism of Western-style learning and the belief that girls don't need an education compounded with regional instability have created a challenging environment for learning to thrive.

Tackling worrying dropout rates

In South Africa, at least 40% of all students drop out of school before completing grade 12. Girls make up the majority of this group.

The consequences of youth prematurely dropping out of school are severe and long-lasting, with many often trapped in a vicious cycle of unemployment and poverty.

"I should have continued with my studies instead of falling pregnant," Akhona Wanda, a teen mother in South Africa told DW.

Nontathu Wanda, Akhona's mother, explained that she wants a better future for her daughter, and accessing education is crucial to achieving that goal.

"It is very important for her to finish school in order to fulfill her dreams," she told DW.

Engagement key to education

Girls like Akhona need support beyond the classroom, however most African countries lack programs to empower girls holistically.

One example of such an initiative is Isibindi Ezikoleni — which roughly translates to "Courage in Schools" — organized by the National Association of Childcare Workers in South Africa. The program focuses on tackling the root causes of disengaging from school to prevent students from dropping out.

"What I have learned in this group since grade 8 is how to be responsible and take care of myself as a girl," one student told DW.

South African youth worker Nomvula Piri stresses the importance of constantly engaging with children who drop out of school and encouraging them to return and continue their studies.

She has helped several pregnant schoolgirls including Akhona return to class after giving birth.

"I ensured that she got her homework and did not fall behind," Piri told DW. "She could always speak to other teachers or me. It was really important for her to continue with her schoolwork during that time.

'Out of the darkness'

In northern Nigeria's Minchika village, local authorities are also encouraging children to stay in the classroom.

Yunus Musa, the co-founder of the Give North Education campaign — which advocates basic education for all, not just a privileged few — has dedicated his life to helping rural kids access education. He believes getting African children back to school is key to society's progress, especially in developing nations.

"Only education brings my people out of the darkness," Musa told DW. "Without this education, there won't be any record of achievement."

Alhaji Ibrahim Sani, a local community leader in Nigeria, says activists like Musa are making an impact.

"We used to write letters to parents and deliver them house by house to encourage the children to go to school," he told DW. " Sometimes, the children here even take themselves to school to enroll. But still, the main thing discouraging school attendance is the distance from the school to the village."

Edited by: Chrispin Mwakideu and Ineke Mules

Explore more

Covid-19: africa's education dilemma, niger's bazoum emphasizes education for post-covid relief funds, un gender equality forum will focus on labor, exclusion, related topics.

Publication

Education in Africa. Placing equity at the heart of policy. Continental report

Learning to read and write, and do simple maths, is a basic requirement to be able to navigate in today’s increasingly globalized and competitive world. Providing children with quality education opens the door for them to a lifetime of better opportunities. These translate not only in terms of the jobs that they will be able to have and how much they will earn, but it also has an impact on their physical and mental health.

Although many countries in Africa are taking significant steps to ensure quality education for all, too many children are still being left behind. One in five primary school age children are not in the classroom. And almost six in ten adolescents are out of school. This is due to several interlinking factors such as geographical location, gender, extreme poverty, disability, crises, conflict, and displacement.

In this comprehensive new analysis, UNESCO explores how these factors impact a child’s access to quality learning. It highlights the importance of addressing barriers to inclusion through actions such as making secondary education compulsory, building more schools, developing adapted curricula, improving the quality of teachers, and providing financial and academic assistance to children. The report aims to provide African governments with guidelines and advice as they try to overcome these challenges.

to prioritize equal opportunity in education

Related items

- Priority Africa

- Sharing knowledge

- Featured articles

- Topics: Display

- Region: Africa

- UNESCO Office in Dakar and Regional Bureau for Education

- SDG: SDG 4 - Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

- See more add

This article is related to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals .

Other recent publications

Why digital inclusion must be at the centre of resetting education in Africa

Image: REUTERS/Thomas Mukoya.

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Sampson Kofi Adotey

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Digital Communications is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, digital communications.

- COVID-19 school closures in Africa have widened existing educational, socio-economic and gender inequalities.

- Along with poor access to distance learning resources, the continent's children have been hard hit.

- Digital technology could level the playing field, but huge public-private sector investment is needed.

The world continues to deal with the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on every sector of the economy and the wellbeing of its people. The path to recovery from the pandemic presents a unique opportunity for systems redesign or better still, a reset. However, one cannot overlook the negative impacts of the pandemic which only exacerbated the existing inequalities across the world.

Have you read?

These 5 industries can drive digital financial inclusion , how can africa prepare its education system for the post-covid world, why more needs to be done to promote gender equality in africa.

Many school children across Africa received no education after several governments shut down schools as part of the strategy to quell the spread of the virus. Parents, especially in remote and rural areas looked on as nothing could be done about their children’s education. No instruction, feedback or interaction with their teachers took place. Even in cases where this happened, fewer topics and less content was transmitted through distance learning modules either facilitated by the television or radio.

Unfair distribution of opportunities

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa constitute 87% of the countries in the world where more than 30% of primary school age girls remain out of school . Young girls and many other vulnerable groups of children continued to experience unique challenges detrimental to their access to education, especially distance learning. Study materials, guides for learning and even tutoring remained inaccessible as reports of harassment by fathers or uncles heightened. Guardians with low or no levels of formal education continued to grapple with supporting their wards with home learning.

Several African governments have rolled out a number of interventions to facilitate distance learning. A number of great innovations have emerged as a result of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education. The acute disparities in accessing education in Africa remains a huge challenge, despite incremental investments by both private and public sector in recent months. Nonetheless, 89% of learners across Sub-Saharan Africa still do not have access to household computers and 82% lack internet access . As schools reopen, there will be a need to play catch up for lost time. However, children living in rural farming communities are most likely to be excluded once again as a result of the clash with crop cultivation periods.

Children living in conflict zones, those with learning difficulites, and those living in extreme poverty seem to have been left out in such difficult times. As parents lost their sources of livelihoods due to the pandemic, the already strained living conditions worsened.

Equal access to education in the digital age

While we may not be out of the woods yet with the pandemic, one thing remains true. A reset of our education system is necessary. Especially if we are committed to unlocking human capabilities and harnessing the demographic dividend of the continent. The socio-economic background of a family should not determine a child’s ability to access quality education or become successful in life.

Education should be a basic human right. Technology is increasingly playing a role in the quality of education and more importantly how learning is done. The online education market is expected to reach $350 billion by 2025 as flexible learning technologies scale-up. Online education enables learners to access resources from any location, at any time, at their own pace, and can be tailored to their individual interests. Huge potential lies with these technologies. Training can be easily scaled-up if the relevant infrastructure is in place.

To address the digital divide and the challenges that hamper access to quality education, we must think of inclusive and innovative ways of transferring knowledge and digital skills to young Africans in rural, underserved and marginalized areas to enhance their prospects of becoming active participants and contributors in the digital and knowledge economies.

African governments must boldly pursue a collaborative approach in transforming education and enforce digital inclusion by investing in both basic and digital infrastructure such as digital public service delivery, internet coverage, and data storage capacity among others. By laying the groundwork for improved access to services and technologies, we will be bridging the gaps in learning and teaching which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Geographies in Depth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Global South leaders: 'It’s time for the Global North to walk the talk and collaborate'

Pooja Chhabria

April 29, 2024

How can Japan navigate digital transformation ahead of a ‘2025 digital cliff’?

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

April 25, 2024

What is desertification and why is it important to understand?

Andrea Willige

April 23, 2024

$400 billion debt burden: Emerging economies face climate action crisis

Libby George

April 19, 2024

How Bengaluru's tree-lovers are leading an environmental restoration movement

Apurv Chhavi

April 18, 2024

The World Bank: How the development bank confronts today's crises

Efrem Garlando

April 16, 2024

Global Education

By Hannah Ritchie, Veronika Samborska, Natasha Ahuja, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser

A good education offers individuals the opportunity to lead richer, more interesting lives. At a societal level, it creates opportunities for humanity to solve its pressing problems.

The world has gone through a dramatic transition over the last few centuries, from one where very few had any basic education to one where most people do. This is not only reflected in the inputs to education – enrollment and attendance – but also in outcomes, where literacy rates have greatly improved.

Getting children into school is also not enough. What they learn matters. There are large differences in educational outcomes : in low-income countries, most children cannot read by the end of primary school. These inequalities in education exacerbate poverty and existing inequalities in global incomes .

On this page, you can find all of our writing and data on global education.

Key insights on Global Education

The world has made substantial progress in increasing basic levels of education.

Access to education is now seen as a fundamental right – in many cases, it’s the government’s duty to provide it.

But formal education is a very recent phenomenon. In the chart, we see the share of the adult population – those older than 15 – that has received some basic education and those who haven’t.

In the early 1800s, fewer than 1 in 5 adults had some basic education. Education was a luxury; in all places, it was only available to a small elite.

But you can see that this share has grown dramatically, such that this ratio is now reversed. Less than 1 in 5 adults has not received any formal education.

This is reflected in literacy data , too: 200 years ago, very few could read and write. Now most adults have basic literacy skills.

What you should know about this data

- Basic education is defined as receiving some kind of formal primary, secondary, or tertiary (post-secondary) education.

- This indicator does not tell us how long a person received formal education. They could have received a full program of schooling, or may only have been in attendance for a short period. To account for such differences, researchers measure the mean years of schooling or the expected years of schooling .

Despite being in school, many children learn very little

International statistics often focus on attendance as the marker of educational progress.

However, being in school does not guarantee that a child receives high-quality education. In fact, in many countries, the data shows that children learn very little.

Just half – 48% – of the world’s children can read with comprehension by the end of primary school. It’s based on data collected over a 9-year period, with 2016 as the average year of collection.

This is shown in the chart, where we plot averages across countries with different income levels. 1

The situation in low-income countries is incredibly worrying, with 90% of children unable to read by that age.

This can be improved – even among high-income countries. The best-performing countries have rates as low as 2%. That’s more than four times lower than the average across high-income countries.

Making sure that every child gets to go to school is essential. But the world also needs to focus on what children learn once they’re in the classroom.

Millions of children learn only very little. How can the world provide a better education to the next generation?

Research suggests that many children – especially in the world’s poorest countries – learn only very little in school. What can we do to improve this?

- This data does not capture total literacy over someone’s lifetime. Many children will learn to read eventually, even if they cannot read by the end of primary school. However, this means they are in a constant state of “catching up” and will leave formal education far behind where they could be.

Children across the world receive very different amounts of quality learning

There are still significant inequalities in the amount of education children get across the world.

This can be measured as the total number of years that children spend in school. However, researchers can also adjust for the quality of education to estimate how many years of quality learning they receive. This is done using an indicator called “learning-adjusted years of schooling”.

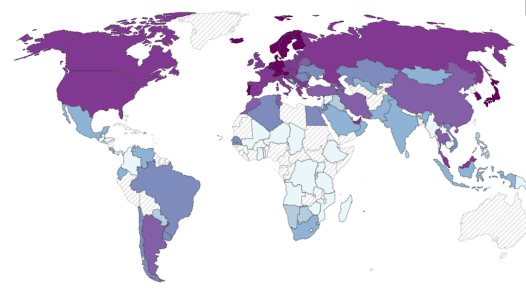

On the map, you see vast differences across the world.

In many of the world’s poorest countries, children receive less than three years of learning-adjusted schooling. In most rich countries, this is more than 10 years.

Across most countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa – where the largest share of children live – the average years of quality schooling are less than 7.

- Learning-adjusted years of schooling merge the quantity and quality of education into one metric, accounting for the fact that similar durations of schooling can yield different learning outcomes.

- Learning-adjusted years is computed by adjusting the expected years of school based on the quality of learning, as measured by the harmonized test scores from various international student achievement testing programs. The adjustment involves multiplying the expected years of school by the ratio of the most recent harmonized test score to 625. Here, 625 signifies advanced attainment on the TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) test, with 300 representing minimal attainment. These scores are measured in TIMSS-equivalent units.

Hundreds of millions of children worldwide do not go to school

While most children worldwide get the opportunity to go to school, hundreds of millions still don’t.

In the chart, we see the number of children who aren’t in school across primary and secondary education.

This number was around 260 million in 2019.

Many children who attend primary school drop out and do not attend secondary school. That means many more children or adolescents are missing from secondary school than primary education.

Access to basic education: almost 60 million children of primary school age are not in school

The world has made a lot of progress in recent generations, but millions of children are still not in school.

The gender gap in school attendance has closed across most of the world

Globally, until recently, boys were more likely to attend school than girls. The world has focused on closing this gap to ensure every child gets the opportunity to go to school.

Today, these gender gaps have largely disappeared. In the chart, we see the difference in the global enrollment rates for primary, secondary, and tertiary (post-secondary) education. The share of children who complete primary school is also shown.

We see these lines converging over time, and recently they met: rates between boys and girls are the same.

For tertiary education, young women are now more likely than young men to be enrolled.

While the differences are small globally, there are some countries where the differences are still large: girls in Afghanistan, for example, are much less likely to go to school than boys.

Research & Writing

Talent is everywhere, opportunity is not. We are all losing out because of this.

Access to basic education: almost 60 million children of primary school age are not in school, interactive charts on global education.

This data comes from a paper by João Pedro Azevedo et al.

João Pedro Azevedo, Diana Goldemberg, Silvia Montoya, Reema Nayar, Halsey Rogers, Jaime Saavedra, Brian William Stacy (2021) – “ Will Every Child Be Able to Read by 2030? Why Eliminating Learning Poverty Will Be Harder Than You Think, and What to Do About It .” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9588, March 2021.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

- Education Statistics

Education Statistics (EdStats)

- DBE Structure

- Contact the DBE

- Western Cape

- Northern Cape

- KwaZulu-Natal

- Eastern Cape

- Media Releases

- Basic Education Sector Insights

- Newsletter: Thuto

- Parliamentary Questions

- Newsletter: DG Provincial Engagements

- Call for Comments

- Government Notices

- Green Papers

- Regulations

- White Papers

- Publications

- Three Stream Model

- ABC Motsepe Schools Eisteddfod

- Funza Lushaka

- Health Promotion

- National School Nutrition Programme

- Quality Assurance and Skills Development

- Safety in Schools

- Second Chance Programme

- Sector Progress, Performance and Research

- Early Grade Reading Study

- Home Education

- South African Sign Language

- Physical Planning and Rural Schooling

- National Curriculum Statements Grades R-12

- National Curriculum Framework for Children from Birth to Four

- Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements (CAPS)

- LTSM National Catalogue

- Digital Content

- Mind the Gap Study Guides

- Graded Readers and Big Book HL

- IIAL Resources

- National Senior Certificate (NSC) Examinations

- National Circulars

- Annual National Assessments

- Senior Certificate

- Certification Services

- Parents and Guardians

- Education Districts

Success by Numbers

Education statistics in south africa report, school realities report.

About Us Education in SA Contact Us Vacancies Provincial Offices Branches

Newsroom Media Releases Speeches Opinion Pieces Multimedia

Examinations Grade 12 Past Exam papers ANA Exemplars Matric Results

Curriculum Curriculum Assessment Policy Statements Practical Assessment Tasks School Based Assessment Mind the Gap Study Guides Learning and Teaching Support Materials

Research EMIS Research Protocols Schools Masterlist Data

Teacher Development Initial Teacher Education National Recruitment Database National Teaching Awards Register as an Educator

Information for... Certification Services Learners Teachers Parents and Guardians Principals Education Districts SGB's Researcher

National Office Address: 222 Struben Street, Pretoria Call Centre: 0800 202 933 | [email protected] Switchboard: 012 357 3000

Certification [email protected] 012 357 4511/3

Government Departments Provincial Departments of Education Government Services

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Education in Africa. Of all regions, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rates of education exclusion. Over one-fifth of children between the ages of about 6 and 11 are out of school, followed by one-third of youth between the ages of about 12 and 14. According to UIS data, almost 60% of youth between the ages of about 15 and 17 are not in school.

Highlights This report, "Transforming Education in Africa: An evidence-based overview and recommendations for long-term improvements", highlights the progress made in the continent's education sector over the past decade from the perspective of the Sustainable Development Goals and the objectives of the Continental Education Strategy for Africa (CESA 2016-2025).

5 TRANSFORMING EDUCATION IN AFRICA: AN EVIDENCE-BASED OVERVIEW AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LONG-TERM IMPROVEMENTS FIGURE 1.1: Composition and evolution of the African population (in millions)..... 9 FIGURE 1.2: Africa's share of the world's population aged 3 to 24, 2000 to 2030..... 10 FIGURE 1.3: Literacy rate by age group and

The share of the population attending university in the late colonial era was extremely low. University enrolment rates have increased in many African countries. Image: Rebecca Simson. Around the time of independence, Kenya had roughly 400 university students (1961), while Tanzania and Zambia had 300 students each (1963).

Out-of-school numbers are growing in sub-Saharan Africa. Download the report. It is estimated that 244 million children and youth between the ages of 6 and 18 worldwide were out of school in 2021, of which 118.5 million were girls and 125.5 million were boys. The results are based on a new, improved way of measuring out-of-school rates by the ...

As Africa has the youngest population in the world—nearly 800 million Africans are under the age of 25, with 677 million between ages 3 and 24—accelerating investment in education is vital for ...

Education in Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa has the fastest growing child population in the world. Yet, the current education system is at capacity, and the demand will increase with nearly 750 million children expected to be of school age by 2060. This rapid increase in cohorts of children and young people presents a significant fiscal pressure on ...

The Leveraging Education Analysis for Results Network (LEARN) will bring together the Continental Education Strategy for Africa (CESA) implementation clusters on education planning, curriculum and teacher development and act as a catalyst for cross-cluster collaboration to address the critical issue for foundational learning in Africa.

Only four out of every 100 children in Africa is expected to enter a graduate and postgraduate institution, compared to 36 out of 100 in Latin America and 14 out of 100 in South and West Asia ...

4n In Senegal students from poor households and rural areas are at a disadvantage in completing education. Proportion of 15- to 19-year-olds who completed years of education, by wealth quintile and area, Senegal, 2014 (%) Source: World Bank EdStats estimates based on Demographic and Health Surveys.

Education Data Release - September 2023 New education data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) released this week track country progress towards Sustainable Development Goal objectives for education (SDG 4). The UIS has been reporting education data since its founding in 1999. As the custodian agency for SDG 4, the UIS provides high quality and reliable education

Justin van Fleet examines the data and trends from the Center for Universal Education's new interactive, the Africa Learning Barometer, which identifies a baseline assessment of learning in Africa.

UIS (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund WAEMU West Africa Economic and Monetary Union ... Expenditure by level of education in African countries, 2019 .....12 Figure 2.7: Education budget credibility rates by item in select countries ...