- Business Analytics for Managers: Leading with Data

- Entrepreneurial Leadership & Influence

- Entrepreneurial Leadership Essentials

- The Entrepreneurship Bootcamp: A New Venture Entrepreneurship Program

- Executive Leadership Program: Owning Your Leadership

- Innovation & Growth Post-Crisis

- Navigating Volatility & Uncertainty as an Entrepreneurial Leader

- Resilient Leadership

- Strategic Planning & Management in Retailing

- Leadership Program for Women & Allies

- Online Offerings Asia

- The Entrepreneurial Family

- Mastering Generative AI in Your Business

- Rapid Innovation Event Series

- Executive Entrepreneurial Leadership Certificate

- Graduate Certificate Credential

- Part-Time MBA

- Help Me Decide

- Entrepreneurial Leadership

- Inclusive Leadership

- Entrepreneurship

- Strategic Innovation

- Custom Programs

- Corporate Partner Program

- Sponsored Programs

- Get Customized Insights

- Business Advisory

- B-AGILE (Corporate Accelerator)

- Corporate Degree Programs

- Recruit Undergraduate Students

- Student Consulting Projects

- Graduate Student Outcomes

- Graduate Student Coaching

- Guest Rooms

- Resources & Tips

- Babson Academy Team

- One Hour Entrepreneurship Webinar

- Price-Babson Symposium for Entrepreneurship Educators

- Babson Fellows Program for Entrepreneurship Educators

- Babson Fellows Program for Entrepreneurship Researchers

- Building an Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

- Certificate in Youth Entrepreneurship Education

- Global Symposia for Entrepreneurship Educators (SEE)

- Babson Build

- Babson Entrepreneurial Thought & Action® (BETA) Workshop

- Entrepreneurial Mindset

- Custom Student Programs

- Facts and Stats

- Mission, Vision, & Values

- College Rankings & Accolades

- Babson’s Strategy in Action

- Community Updates

- Our Process

- Task Forces

- Multimodal Communications and Engagement Plan

- Notable Alumni

- Babson College History

- Roger Babson

- Babson Globe

- Accreditation

- For News Media

- Student Complaint Information

- Entrepreneurial Leadership at Babson

- Entrepreneurial Thought & Action

- Immersive Curriculum

- Babson, Olin, & Wellesley Partnership

- Prior Academic Year Publications

- The Babson Collection

- Teaching Innovation Fund

- The Proposal Process

- Services Provided

- Funding Support Sources

- Post-Award Administration

- Five Steps to Successful Grant Writing

- Simple Budget Template

- Simple Proposal Template

- Curriculum Innovation

- Digital Transformation Initiative

- Herring Family Entrepreneurial Leadership Village

- Stephen D. Cutler Center for Investments and Finance

- Weissman Foundry at Babson College

- Meeting the Moment

- Community Messages

- College Leadership

- Dean of the College & Academic Leadership

- Executives in Residence

- Entrepreneurs in Residence

- Filmmaker in Residence

- Faculty Profiles

- Research and Publications

- News and Events

- Contact Information

- Student Resources

- Division Faculty

- Undergraduate Courses

- Graduate Courses

- Areas of Study

- Language Placement Test

- Make An Appointment

- The Wooten Prize for Excellence in Writing

- How To Become a Peer Consultant

- grid TEST images

- Student Research

- Carpenter Lecture Series

- Visiting Scholars

- Undergraduate Curriculum

- Student Groups and Programming

- Seminar Series

- Best Projects of Fall 2021

- Publications

- Academic Program

- Past Conferences

- Course Listing

- Math Resource Center

- Emeriti Faculty Profiles

- Arthur M. Blank School for Entrepreneurial Leadership

- Anti-Racism Educational Resources

- Clubs & Organizations

- Safe Zone Training

- Ways to Be Gender Inclusive

- External Resources

- Past Events

- Meet the Staff

- JEDI Student Leaders

- Diversity Suite

- Leadership Awards

- Creativity Contest

- Share Your Service

- Featured Speakers

- Black Business Expo

- Heritage Months & Observances

- Bias-Related Experience Report

- Course Catalog

The Blank School engages Babson community members and leads research to create entrepreneurial leaders.

Looking for a specific department's contact information?

Learn about open job opportunities, employee benefits, training and development, and more.

- Why Babson?

- Evaluation Criteria

- Standardized Testing

- Class Profile & Acceptance Rate

- International Applicants

- Transfer Applicants

- Homeschool Applicants

- Advanced Credits

- January Admission Applicants

- Tuition & Expenses

- How to Apply for Aid

- International Students

- Need-Based Aid

- Weissman Scholarship Information

- For Parents

- Access Babson

- Contact Admission

- January Admitted Students

- Fall Orientation

- January Orientation

- How to Write a College Essay

- Your Guide to Finding the Best Undergraduate Business School for You

- What Makes the Best College for Entrepreneurship?

- Six Types of Questions to Ask a College Admissions Counselor

- Early Decision vs Early Action vs Regular Decision

- Entrepreneurship in College: Why Earning a Degree Is Smart Business

- How to Use Acceptance Rate & Class Profile to Guide Your Search

- Is College Worth It? Calculating Your ROI

- How Undergraduate Experiential Learning Can Pave the Way for Your Success

- What Social Impact in Business Means for College Students

- Why Study the Liberal Arts and Sciences Alongside Your Business Degree

- College Concentrations vs. Majors: Which Is Better for a Business Degree?

- Finding the College for You: Why Campus Environment Matters

- How Business School Prepares You for a Career Early

- Your College Career Resources Are Here to Help

- Parent’s Role in the College Application Process: What To Know

- What A College Honors Program Is All About

Request Information

- Business Foundation

- Liberal Arts & Sciences Foundation

- Foundations of Management & Entrepreneurship (FME)

- Socio-Ecological Systems

- Advanced Experiential

- Hands-On Learning

- Business Analytics

- Computational & Mathematical Finance

- Environmental Sustainability

- Global & Regional Studies

- Historical & Political Studies

- Identity & Diversity

- International Business Environment

- Justice, Citizenship, & Social Responsibility

- Leadership, People, & Organizations

- Legal Studies

- Literary & Visual Arts

- Managerial Financial Planning & Analytics

- Operations Management

- Quantitative Methods

- Real Estate

- Retail Supply Chain Management

- Social & Cultural Studies

- Strategy & Consulting

- Technology Entrepreneurship

- Undergraduate Faculty

- Global Study

- Summer Session

- Other Academic Opportunities

- Reduced Course Load Policy

- Leadership Opportunities

- Athletics & Fitness

- Social Impact and Sustainability

- Bryant Hall

- Canfield and Keith Halls

- Coleman Hall

- Forest Hall

- Mandell Family Hall

- McCullough Hall

- Park Manor Central

- Park Manor North

- Park Manor South

- Park Manor West

- Publishers Hall

- Putney Hall

- Van Winkle Hall

- Woodland Hill Building 8

- Woodland Hill Buildings 9 and 10

- Gender Inclusive Housing

- Student Spaces

- Policies and Procedures

- Health & Wellness

- Mental Health

- Religious & Spiritual Life

- Advising & Tools

- Internships & Professional Opportunities

- Connect with Employers

- Professional Paths

- Undergraduate News

- Request Info

- Plan a Visit

- How to Apply

98.7% of the Class of 2022 was employed or continuing their education within six months of graduation.

- Application Requirements

- Full-Time Merit Awards

- Part-Time Merit Awards

- Tuition & Deadlines

- Financial Aid & Loans

- Admission Event Calendar

- Admissions Workshop

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Contact Admissions

- Data Scientist Career Path & Business Analytics: Roles, Jobs, & Industry Outlook

- How to Improve Leadership Skills in the Workplace

- Is a Master’s in Business Analytics Worth It?

- Is a Master’s in Leadership Worth It? Yes. Find Out Why.

- The Big Question: Is an MBA Worth It?

- Is Online MBA Worth It? In a Word, Yes.

- Master in Finance Salary Forecast

- Masters vs MBA: How Do I Decide

- MBA Certificate: Everything You Need to Know

- MBA Salary Florida What You Can Expect to Make After Grad School

- Preparing for the GMAT: Tips for Success

- Admitted Students

- Find Your Program

- Babson Full Time MBA

- Master of Science in Management in Entrepreneurial Leadership

- Master of Science in Finance

- Master of Science in Business Analytics

- Certificate in Advanced Management

- Part-Time Flex MBA Program

- Part-Time Online MBA

- Blended Learning MBA - Miami

- Business Analytics and Machine Learning

- Quantitative Finance

- International Business

- STEM Masters Programs

- Consulting Programs

- Graduate Student Services

- Centers & Institutes

- Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

- Kids, Partners, & Families

- Greater Boston & New England

- Recreation & Club Sports

- Campus Life

- Career & Search Support

- Employer Connections & Opportunities

- Full Time Student Outcomes

- Part Time Student Outcomes

- The Grad CCD Podcast

- Visit & Engage

Review what you'll need to apply for your program of interest.

Need to get in touch with a member of our business development team?

- Contact Babson Executive Education

- Contact Babson Academy

- Email the B-Agile Team

- Your Impact

- Ways to Give

- Make Your Mark

- Barefoot Athletics Challenge

- Roger’s Cup

- Alumni Directory

- Startup Resources

- Career Resources

- Back To Babson

- Going Virtual 2021

- Boston 2019

- Madrid 2018

- Bangkok 2017

- Cartagena 2015

- Summer Receptions

- Sunshine State Swing

- Webinar Library

- Regional Clubs

- Affinity Groups

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Classes and Reunion

- Babson Alumni Advisory Board

- College Advancement Ambassadors

- Visiting Campus

- Meet the Team

- Social Media

- Babson in a Box

- Legacy Awards

When you invest in Babson, you make a difference.

Your one-stop shop for businesses founded or owned by Babson alumni.

Prepare for the future of work.

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Meet the Faculty Director

- Visit & Engage

- Lifelong Learning

- Babson Street

- Professional

- Faculty & Staff Programs

Learn to Lead a Thriving Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem

In our increasingly dynamic and unpredictable world, an entrepreneurial mindset is quickly becoming a must-have trait. In order to best serve today’s students and prepare them for tomorrow’s future, university administrators and educators must understand the university-based entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Developing a thriving entrepreneurship education ecosystem is a collaborative effort. Institutions whose entrepreneurship education ecosystems are just beginning to form can accelerate their trajectory with the right network and support. Lay the groundwork to catalyze your school’s entrepreneurship efforts with proven frameworks and action plans from the No. 1 college for entrepreneurship in the United States.

- Watch the Q&A Webinar

Watch a video recording of professors Candida Brush and Patricia Greene discussing the program with prospective attendees and providing an overview of format, curriculum, and learning outcomes.

What Will You Learn?

Gain the approach, plan, guidance, and network of support you need to develop a high-impact entrepreneurship education ecosystem within your institution. Join entrepreneurship educator peers from around the world as you learn a hands-on approach for making progress on your campus. During this program for academic entrepreneurs, you will cover topics such as:

- Assessing your entrepreneurial ecosystem to understand gaps, opportunities, and barriers to progress

- How to develop strategies for overcoming challenges in moving your entrepreneurial initiatives forward

- Networking across the ecosystem to acquire resources, engage stakeholders, and build your reputation

- Leading change both inside and outside your institution

- Key success factors for how institutions create and develop entrepreneurship education ecosystems

- Assembling the resources to build and grow an entrepreneurship education ecosystem

- Gaining the tools to reflect on and amplify your personal entrepreneurial leadership capabilities

When faculty collaborate, as we are with this course, the exchange of ideas provides incredible opportunities for methods that engage students and foster optimal learning.

At A Glance

Who should attend.

This program is well suited for entrepreneurship faculty and administrators who are leading a center, institute, accelerator/incubator, or entrepreneurship project or initiative and who are interested in entrepreneurship education ecosystem development.

- Register Now

What You Need to Know

This three-week online program includes:

- Monday, February 19 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Monday, February 26 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Monday, March 4 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Monday, March 11 from 9–11 a.m. EST

- Approximately 20 hours of session and self-paced work throughout the program.

Program materials include case studies, self-assessments, team projects, discussion boards, reflection exercises, and oral presentations.

A 10% discount is available for Babson Collaborative members. Please email [email protected] for more information about discounts.

Meet the Faculty

Candida Brush, Professor

Renowned entrepreneurship professor Candida Brush is a pioneering entrepreneurship researcher. She has co-authored reports for the OECD, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, and the Goldman Sachs Foundation, and presented her work at the World Economic Forum in Davos and to the U.S. Department of Commerce. She has authored more than 160 publications including 13 books, and is one of the most highly cited researchers in the field.

Patricia Greene, Professor Emerita

Patricia Greene is Professor Emerita at Babson College. From 2017-2019, she served as the presidentially appointed 18th Director of the Women’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor. Prior to her term in Washington, D.C., she held the Paul T. Babson Chair in Entrepreneurial Studies at Babson College where she formerly served as Provost (2006-2008) and Dean of the Undergraduate School (2003-2006). Dr. Greene’s research focuses on the identification, acquisition, and combination of entrepreneurial resources, particularly by women and minority entrepreneurs. She is a founding member of the Diana Project and the founding national academic director for Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses Program.

What Makes Babson Academy Different?

At Babson Academy, we believe entrepreneurship education changes the world. To date, we have impacted more than 8,700 educators and students from 1,300 educational institutions in more than 80 countries. Our goal? Advancing global entrepreneurial learning across universities worldwide.

Our programs are about more than theory; they’re about action, and equipping you with the practical tools and strategies necessary to have an immediate impact on your institution.

Our Experts in the News

Faculty for the Building an Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem program have deep expertise in building and growing robust entrepreneurship education ecosystems, all backed by Babson’s 28-year track record as the No. 1 College for entrepreneurship education in the United States.

Amplifying Entrepreneurial Learning Outside the Classroom

Candida Brush served as Babson’s Entrepreneurship Division chair for a decade before eventually becoming vice provost. In that role, she oversaw five of Babson’s academic centers, each focusing on different aspects of entrepreneurship, from family businesses to social enterprises.

Four Approaches to Teaching an Entrepreneurship Method

Patti Greene explains how teaching an entrepreneurship method rather than a process is the best way to combat unpredictability. There are four complementary techniques for teaching entrepreneurship as a method and each requires students to reach beyond their prediction-focused ways of knowing, analyzing, and talking.

Appreciating the Value of Entrepreneurial Women

According to Professor Candida Brush’s Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report, “the research highlights areas where women entrepreneurs have made significant progress, how ecosystems influence and are influenced by women entrepreneurs, and where there are still gaps, challenges, and opportunities.”

Want More Resources for Entrepreneurship Educators?

Become a Babson Collaborative member today, and join forces with 29 member institutions from 21 countries and counting. Gain access to a members-only portal, curriculum resources, the latest field research, the Collaborative WhatsApp community, and unparalleled networking with fellow entrepreneurship educators.

How and when will I have access to the course materials?

Course materials are provided via Canvas, Babson’s online learning portal. Materials will be made available to participants approximately one to seven days prior to the first live online session, depending on the amount of pre-work that participants are expected to complete in advance.

Where can I find the schedule for the days and times of the live online sessions?

The schedule will be sent to registered participants in the registration confirmation email (see the link in your confirmation email to the EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW document).

Do I need to join the virtual sessions live? Will they be recorded?

We highly recommend that participants join the live online sessions. It is an opportunity to ask questions, participate in rich discussion, and learn from the experience of your program peers. Session recordings will not consistently be available, and as such, it is expected that participants engage live in the virtual sessions.

What technology do you use for the live online programs?

- Canvas, Babson’s online learning portal —course calendar, readings, pre-work, faculty bios, presentations and post-session recordings are posted here.

- Video-conferencing Platform —we will use a virtual meeting application (like Webex or Zoom) that allows you to see and communicate with other participants simultaneously and in real time. Your instructor can share documents and interactive media, invite participants to share content, and engage with you in real-time participation. Links to sessions and more information will be provided on Canvas.

What do I need to participate? How do I prepare for the live online sessions?

Live sessions will be delivered via WeChat and Zoom.

Prior to each virtual session, please ensure you are prepared with the following:

- A computer/laptop with a webcam (built-in or external camera) for optimal viewing, but you may also join from a tablet or cellphone.

- Internet connection or cell hotspot

- Operating system: Windows: 7,8.1, or 10; Apple: OS 10.9 or higher

- Recommended browsers for optimal experience: HIGHLY RECOMMEND Google Chrome. Internet Explorer 11, Firefox 52, Safari 11 are not as optimal but should work as well. (Microsoft Edge, Internet Explorer 8, 9, 10, and Safari 7 are not recommended.)

- Headset with microphone (recommended but optional)

- Test your connection, audio and microphone by joining a Zoom test meeting.

What happens if I have technical issues?

Additional, detailed instructions will be provided on Canvas. Babson staff will be online and available to assist you, and will identify themselves during each live online delivery. Contact the staff via the chat function for help, or email them if needed. Contact information is available in the EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW document.

How long will I have access to the online materials?

Course materials on Canvas will be available for six months following the completion of the program.

When is payment due and what types of payment do you accept?

Payment is due in full at the time of registration. Babson accepts Visa, MasterCard, or American Express.

Do you offer discounts?

Discounts on Babson Academy courses are available for the following:

- Alumni of Babson College (undergraduate or graduate)

- Babson Collaborative members

- Groups of three or more registering at the same time

Please email [email protected] for more information and for discount codes before registering. In addition, please note that discounts cannot be combined.

Do you offer online programs for large groups from the same company?

Yes, we can customize a program to your company’s specific needs from our diverse certificate and courses portfolio. Please email [email protected] for additional information.

What will I receive upon completion of the program?

Each program participant receives a certificate of completion. We invite participants to add the program to their LinkedIn profile. Note that a certificate will not be provided if there is insufficient evidence of participation.

Do you have translation for non-English speaking participants?

We do not offer translation in our programs. Although we do not require the TOEFL, all Babson Academy programs are taught in English, so it is a prerequisite that you speak, read, and write English proficiently.

Where can I find information for in-person programs?

Explore Babson Academy’s full suite of programs .

What is your cancellation policy for live online programs?

Registration changes must be requested in writing to Babson Academy.

- Cancellations receive a 100% refund

- Substitutions* are allowed, subject to a $250 administration fee

- One-Time Transfers* allowed subject to a $250 administration fee, to be utilized within a one-year period

- Cancellations receive a 50% refund

- One-Time Transfers* are not allowed

- Cancellations do not receive a refund

- Substitutions* are not allowed

*Substitutions and transfers are subject to approval to ensure that participants and programs are suitable.

By submitting this form, you agree to receive communications from Babson College and our representatives about our educational programs and activities via phone and/or email. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking Unsubscribe from an email.

Ready to Talk Now?

Contact Babson Academy [email protected]

How to Inspire Entrepreneurial Thinking in Your Students

Explore more.

- Course Design

- Experiential Learning

- Perspectives

- Student Engagement

T he world is in flux. The COVID-19 pandemic has touched every corner of the globe, profoundly impacting our economies and societies as well as our personal lives and social networks. Innovation is happening at record speed. Digital technologies have transformed the way we live and work.

At the same time, world leaders are collaborating to tackle the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals , which aim to address issues related to health, education, gender equality, energy, and more. Private sector leaders, too, are recognizing that it makes good business sense to be aware of corporations’ social and environmental impact.

So, how can we as educators prepare our students to succeed in this tumultuous and uncertain—yet hopeful and exhilarating—global environment? As the world changes, so do the skills students need to build their careers—and to build a better society. For students to acquire these evolving skills, we believe educators must help students develop an entrepreneurial mindset.

6 Ways You Can Inspire Entrepreneurial Thinking Among Your Students

An entrepreneurial mindset —attitudes and behaviors that encapsulate how entrepreneurs tend to think and act—enables one to identify and capitalize on opportunities, change course when needed, and view mistakes as an opportunity to learn and improve.

If a student decides to become an entrepreneur, an entrepreneurial mindset is essential. And for students who plan to join a company, nonprofit, or government agency, this mindset will enable them to become intrapreneurs —champions of innovation and creativity inside their organizations. It can also help in everyday life by minimizing the impact of failure and reframing setbacks as learning opportunities.

“As the world changes, so do the skills students need to build their careers—and to build a better society.”

Effective entrepreneurship professors are skilled at nurturing the entrepreneurial mindset. They, of course, have the advantage of teaching a subject that naturally demands students think in this way. However, as we will explore, much of what they do in their classroom is transferable to other subject areas.

We interviewed top entrepreneurship professors at leading global institutions to understand the pedagogical approaches they use to cultivate this mindset in their students. Here, we will delve into six such approaches. As we do, think about what aspects of their techniques you can adopt to inspire entrepreneurial thinking in your own classroom.

1. Encourage Students to Chart Their Own Course Through Project-Based Learning

According to Ayman Ismail, associate professor of entrepreneurship at the American University in Cairo, students are used to pre-packaged ideas and linear thinking. “Students are often told, ‘Here’s X, Y, Z, now do something with it.’ They are not used to exploring or thinking creatively,” says Ismail.

To challenge this linear pattern, educators can instead help their students develop an entrepreneurial mindset through team-based projects that can challenge them to identify a problem or job to be done, conduct market research, and create a new product or service that addresses the issue. There is no blueprint for students to follow in developing these projects, so many will find this lack of direction confusing—in some cases even frightening. But therein lies the learning.

John Danner, who teaches entrepreneurship at Princeton University and University of California, Berkeley, finds his students similarly inhibited at the start. “My students come in trying to understand the rules of the game,” he says. “I tell them the game is to be created by you.”

Danner encourages students to get comfortable navigating life’s maze of ambiguity and possibility and to let their personal initiative drive them forward. He tells them, “At best you have a flashlight when peering into ambiguity. You can shine light on the next few steps.”

In your classroom: Send students on an unstructured journey. Dive right in by asking them to identify a challenge that will hone their problem-finding skills and encourage them to work in teams to find a solution. Do not give them a blueprint.

For example, in our M²GATE virtual exchange program, we teamed US students with peers located in four countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. We asked them to identify a pressing social issue in MENA and then create a product or service to address it. One of the teams identified the high rate of youth unemployment in Morocco as an issue. They discovered that employers want workers with soft skills, but few schools provide such training. Their solution was a low-cost after-school program to equip students ages 8-16 with soft skills.

2. Help Students Think Broadly and Unleash Their Creativity

Professor Heidi Neck says her students at Babson College struggle with problem finding at the start of the entrepreneurial journey. “They are good at solving problems, but not as good at finding the problem to solve,” she explains. “For example, they know that climate change is a problem, and they’re interested in doing something about it, but they’re not sure what problem within that broad area they can focus on and find a market for.”

Professor Niko Slavnic, who teaches entrepreneurship at IEDC-Bled School of Management in Slovenia and the ESSCA School of Management in France, says he first invests time in teaching his students to unlearn traditional ways of thinking and unleash their creativity. He encourages students to get outside their comfort zones. One way he does this is by having them make paper airplanes and then stand on their desks and throw them. Many ask, “Should we do this? Is this allowed?” When his students start to question the rules and think about new possibilities, this indicates to Slavnic that they are primed for the type of creative exploration his course demands.

“When students start to question the rules and think about new possibilities, this indicates to Professor Niko Slavnic that they are primed for the type of creative exploration his course demands.”

In your classroom: Think about the concept of “unlearning.” Ask yourself if students are entering your class with rigid mindsets or attitudes based on rules and structures that you would like to change. For example, they may be coming into your classroom with the expectation that you, the instructor, have all the answers and that you will impart your wisdom to them throughout the semester. Design your course so that students spend more time than you do presenting, with you acting more as an advisor (the “guide on the side”).

3. Prompt Students to Take Bold Actions

Geoff Archer, an entrepreneurship professor at Royal Roads University in Canada, says Kolb’s theory of experiential learning underpins the entrepreneurial management curriculum he designed. Archer takes what he calls a “ready-fire-aim approach,” common in the startup world—he throws students right into the deep end. They are tasked with creating a for-profit business from scratch and operating it for a month. At the end of the semester, they must come up with a “pitch deck”—a short presentation providing potential investors with an overview of their proposed new business—and an investor-ready business plan.

This approach can be met with resistance, especially with mature learners. “They’re used to winning, and it’s frustrating and more than a bit terrifying to be told to do something without being given more structure upfront,” says Archer.

Professor Rita Egizii, who co-teaches with Archer, says students really struggled when instructed to get out and talk with potential customers about a product they were proposing to launch as part of their class project. “They all sat outside on the curb on their laptops. For them, it’s not normal and not okay to make small experiments and fail,” says Egizii.

Keep in mind that, culturally, the taboo of failure—even on a very small scale and even in the name of learning—can be ingrained in the minds of students from around the world.

The benefit of this permutation, explains Archer, is that students are writing plans based on actual experiences—in this case, customer interactions. Moving the starting blocks forward offers many benefits, including getting the students out of the classroom and out of their heads earlier, reminding them that the market’s opinion of their solution is far more important than their own. This also affords students more time to reflect and maximize the potential of their minimum viable product or experiment.

In your classroom: Invite students to bring their lived experiences and workplace knowledge into their studies. This can be just as powerful as the more famous exhortation to “get out of the classroom.” As Egizii sees it, “student-directed experiential learning provides a comfortable and relatable starting point from which they can then diverge their thinking.”

4. Show Students What They Can Achieve

For Eric Fretz, a lecturer at the University of Michigan, the key to launching his students on a successful path is setting the bar high, while at the same time helping them understand what is realistic to achieve. “You will never know if your students can jump six feet unless you set the bar at six feet,” he says.

His undergraduate students work in small teams to create a product in three months and generate sales from it. At the start of the semester, he typically sees a lot of grandiose ideas—a lot of “fluff and BS” as he calls it. Students also struggle with assessing the viability of their ideas.

To help, Fretz consults with each team extensively, filtering through ideas together until they can agree upon a feasible one that fulfills a real need. The real magic of his course is in the coaching and support he provides.

“People know when you’re investing in them and giving them your attention and energy,” Fretz says. He finds that coaching students in the beginning of the course helps assuage their concerns about embarking on an open-ended team project, while also supporting initiative and self-reliance.

In your classroom: Design ways to nudge your students outside their comfort zones, while also providing support. Like Fretz, you should set high expectations, but also adequately guide students.

5. Teach Students the Value of Changing Course

A key part of the entrepreneurial mindset is to be able to course-correct, learn from mistakes, and move on. Entrepreneurship professors position hurdles as learning opportunities. For example, Danner tells his students that his class is a laboratory for both aspiring and failing. He advises them to expect failure and think about how they are going to deal with it.

“A key part of the entrepreneurial mindset is to be able to course-correct, learn from mistakes, and move on.”

Ismail believes letting his students fail in class is the best preparation for the real world. He let one student team pursue a project for the entire semester around a product he knew had no potential. Two days before the end of the course, he told them as such. From his perspective, their frustration was the best learning experience they could have and the best training he could offer on what they will experience in real life. This reflects a key component of the entrepreneurial mindset— the ability to view mistakes as opportunities .

In your classroom: Build into your course some opportunities for students to make mistakes. Show them how mistakes are an opportunity to learn and improve. In entrepreneurship speak, this is called a “pivot.” Can you build in opportunities for students to face challenges and have to pivot in your course?

6. Communicate with Students Regularly to Establish New Ways of Thinking

Professor Neck realized that to nurture the entrepreneurial mindset in her students, she needed to provide them with opportunities to do so outside of class. She now encourages her students to establish a daily, reflective practice. She even designed a series of daily “mindset vitamins” that she sends to her students via the messaging platform WhatsApp. Students are not expected to reply to the messages, but rather to simply consume and absorb them.

Some messages relate specifically to entrepreneurship, such as: “How can you get started with nothing?” And others apply to life in general: “What has been your proudest moment in life so far? How can you create more moments like that? What did it feel like the last time you failed?”

In your classroom: Communicate with your students outside the classroom with messages that reinforce the mindset change you are seeking to achieve in your course. Social media and apps such as WhatsApp and Twitter make it easy to do so.

All Students Can Benefit from an Entrepreneurial Mindset

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that an entrepreneurial mindset is critical for addressing today’s problems. Adapting to risk, spotting opportunity, taking initiative, communicating and collaborating, being flexible, and problem solving—these are ways in which we have responded to the pandemic. And they’re all part of the entrepreneurial mindset. By instilling this way of thinking in our students, we will equip them to handle tomorrow’s challenges—as well as to identify and take advantage of future opportunities.

Thinking about which of these entrepreneurial approaches you can adopt in your own teaching may require you to redesign portions of your courses or even create a new course from scratch. We encourage you to be open to experimenting and trying out some of these ideas. Like the best entrepreneurs, don’t be afraid to fail.

Also, be open with your students. Let them know you are trying out some new things and solicit their feedback. If needed, you can always pivot your class and involve them in the exercise of co-creating something better together. In the process, you will also be modeling the entrepreneurial mindset for your students.

Amy Gillett is the vice president of education at the William Davidson Institute , a non-profit located at the University of Michigan. She oversees design and delivery of virtual exchanges, entrepreneurship development projects, and executive education programs. Over the past two decades, she has worked on a wide variety of global programs, including 10,000 Women , equipping over 300 Rwandan women with skills to scale their small businesses, and the NGO Leadership Workshops—one-week training programs held in Poland and Slovakia designed to enhance the managerial capability and sustainability of nongovernmental organizations in Central and Eastern Europe.

Kristin Babbie Kelterborn co-leads the Entrepreneurship Development Center (EDC) at the William Davidson Institute. She collaborates with the EDC’s faculty affiliates to design and implement projects that support entrepreneurs in building and growing their businesses in low- and middle-income countries.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- Our Mission

How Teaching Builds Entrepreneurial Skills

Whether you’re pursuing a new passion or a side project, these teaching skills will serve you well in your endeavors.

At the end of my 17th year working in education, I started a plant-based (vegan) deli slice business, and although I didn’t have any experience in business or the food industry, it was a pleasant surprise to discover that my experiences teaching and working within educational systems proved invaluable as an entrepreneur.

Although entrepreneurship is often associated with business, The Balance defines an entrepreneur more broadly, as “someone who develops an enterprise around an innovation.” Whether you are a teacherpreneur , considering a side hustle, or even thinking about a career change, I’ve identified 10 principles of transferable qualities and skills from teaching that apply to the world of entrepreneurship.

10 entrepreneurial teacher Qualities and Skills

1. Centered on values: Teaching is a caring profession. Teachers care for students by providing a safe, productive learning environment and helping students improve their skills, build their knowledge, and cultivate their dispositions.

The world needs more entrepreneurs who are not just out to make money, but actually are “making the world a better place,” to quote this Silicon Valley parody . Teachers, with their commitment to helping others, can direct entrepreneurship toward benevolent goals and work toward those goals with kindness. And they can leverage a knack for communicating the deeper “why” behind their actions.

2. Educating others: Teachers, of course, help students learn. As an entrepreneur, you will also need to educate and communicate with customers who need to understand the products or services that you are offering.

As experts in designing, facilitating, and assessing learning, teachers can help others understand their entrepreneurial projects. Customers frequently asked me how to use the vegan deli slices that I was selling, so, like a good formative assessor, I used that information to advance learning. I created QR codes that appear on the back of every package and take customers to a webpage with illustrations of possible uses—a multimodal approach to addressing “pain points” in learning.

3. Marketing: Teachers find ways to help students see the value in their learning. It is no small feat to appeal to students’ myriad interests, preferences, and identities.

Appealing to customers is similar. For example, working with youth helped me recognize that superheroes are timeless, which led to my creation of a plant-based superhero logo, which has resonated with my customers.

4. Persistence: Teaching can be hard. Students have many strengths, needs, preferences, advantages, and disadvantages, so it is inevitable that teachers’ efforts sometimes fall short and don’t lead to advances in students’ learning. Yet, in those moments, teachers keep trying—again and again.

That persistence is helpful in entrepreneurship, since there are inevitable setbacks. As one of many examples, I think of a time when my attempt to slice a garbanzo-bean-based vegan “meat” created, instead, a pile of mush. Rather than give up, I sent samples of the product to industrial slicer manufacturers who can slice it more effectively. Flexibility and problem-solving, the roots of persistence, are as needed in business as in the classroom.

5. Being a learner: Teachers model lifelong learning by demonstrating a growth mindset and applying strategies to advance their learning. Since entrepreneurial projects are new by nature, they too require learning. Whether pursuing a new degree or a professional certification, or shadowing a master in a craft or trade, embracing the qualities and habits of mind that make learning most effective will serve teachers well in many contexts beyond school-based professional learning.

6. Navigating systems: From licensure to fingerprinting, teachers navigate many facets of the education system, and the tenacity needed to do so can also come to fruition as an entrepreneur. In my case, using the state’s teacher credentialing system prepared me to navigate federal, state, and local food and health regulations—necessary, if not the most exciting, components of starting a food-based business in a safe and effective way.

7. Developing rapport: Most teachers get a new flock of students every semester or year and learn strategies for quickly developing rapport with them—which can be crucial to success. To do so, teachers build trust, listen actively, and find shared interests with students. And those skills can also be invaluable in helping entrepreneurs quickly build rapport with collaborators, colleagues, contractors, and customers in their business projects.

8. Connections in the community: Whatever your endeavor, you probably already have connections who can help you if you identify and leverage them. As a teacher, you are embedded in the community, and the colleagues and families whom you know can be valuable resources.

After I announced that I was leaving my position to start my business, my colleagues offered helpful feedback on early versions of my plant-based deli slices that informed future iterations. Who in your community can support your entrepreneurial project?

9. Planning: Teachers do a lot of planning. The skills involved in mapping out steps needed to advance toward reaching a certain goal, and adjusting along the way, resemble business planning.

In my business plan, I project revenue/sales for the next few years. As I compare the actual sales to those projects, I make adjustments that resemble the interplay of a unit plan in teaching. Starting with a goal and working backward to identify next steps needed to achieve it, and applying knowledge of assessment to track progress, are invaluable skills.

10. Content knowledge: The content that you teach may be directly applicable to an entrepreneurial project. I have a background in science education, and my understanding of measurements and experimentation has been helpful as I’ve tinkered with recipes and scaled my business.

For example, I cool the batter for one of my products in molds. For the prototype, I used a duct pipe lined with parchment paper, followed by candle molds. After scouring the internet for food-safe options, I landed on stainless steel cheese molds.

Each day, teachers build their entrepreneurial tool kit, perhaps without knowing it. Whether forging a new career path or crafting an educational initiative alongside your life as a teacher, educator entrepreneurs have much to offer in shaping a better future.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Can Entrepreneurship Be Taught in a Classroom?

- Ashish K. Bhatia

- Natalia Levina

How some business schools rewrote the script.

As the pandemic reshapes entire industries, the need for agile entrepreneurs have never been more urgent. But traditional business education isn’t always optimized for preparing the next generation of leaders for an uncertain, rapidly changing world. Nevertheless, some business schools have pioneered new teaching models designed to teach entrepreneurship more effectively by focusing on “effectuation,” or leveraging existing resources to take action. New research sheds light on two new models for entrepreneurship education: Rotman’s operating theater classroom, in which startups are interrogated in front of an audience of students, and Darden’s rewiring approach, in which students are encouraged to embrace an action-oriented, collaborative mindset.

In these difficult times, we’ve made a number of our coronavirus articles free for all readers. To get all of HBR’s content delivered to your inbox, sign up for the Daily Alert newsletter.

In early April, a Thai student in our entrepreneurship class saw a shortage of high quality, low cost hand sanitizer across Thailand. To support the Covid relief effort and generate revenue, he quickly shifted his family’s medical supply company to sanitizer production. Closer to home, when Dollaride, a business incubated in NYU’s Future Labs, recognized that the pandemic had eliminated demand for their shared commuting van business in New York, they refreshed their business model to leverage their existing vans, technology, and routes to support burgeoning package delivery demands.

- AB Ashish K. Bhatia is a Clinical Associate Professor of Management & Entrepreneurship and the Academic Director of the B.S. in Business, Technology, and Entrepreneurship Program at NYU Stern School of Business. See Ashish’s faculty bio here .

- NL Natalia Levina is the Toyota Motors Corporation Term Professor of Information Systems at NYU Stern School of Business and Director of the Fubon Center for Technology, Business and Innovation. See Natalia’s faculty bio here .

Partner Center

- Understanding Poverty

Entrepreneurship Education and Training Programs around the World: Dimensions for Success

- This page in:

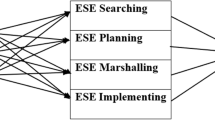

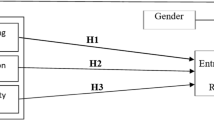

Extra-curricular support for entrepreneurship among engineering students: development of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions

The mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness

Individual entrepreneurial orientation for entrepreneurial readiness

Introduction.

In the era of the knowledge economy, entrepreneurship has emerged as a fundamental driver of social and economic development. As early as 1911, Schumpeter proposed the well-known theory of economic development, wherein he first introduced the concepts of entrepreneurship and creative destruction as driving forces behind socioeconomic development. Numerous endogenous growth theories, such as the entrepreneurial ecosystem mechanism of Acs et al. ( 2018 ), which also underscores the pivotal role of entrepreneurship in economic development, are rooted in Schumpeter’s model. Recognized as a key means of cultivating entrepreneurs and enhancing their capabilities (Jin et al., 2023 ), entrepreneurship education (EE) has received widespread attention over the past few decades, especially in the context of higher education (Wong & Chan, 2022 ).

Driven by international trends and economic demands, China places significant emphasis on nurturing innovative talent and incorporating EE into the essential components of its national education system. The State Council’s “Implementation Opinions on Deepening the Reform of Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education” (hereafter referred to as the report) underscores the urgent necessity for advancing reforms in innovation and EE in higher education institutions. This initiative aligns with the national strategy of promoting innovation-driven development and enhancing economic quality and efficiency. Furthermore, institutions at various levels are actively and eagerly engaging in EE.

Despite the positive strides made in EE in China, its development still faces a series of formidable practical challenges. As elucidated in the report, higher education institutions face challenges such as a delay in the conceptualization of EE, inadequate integration with specialized education, and a disconnect from practical applications. Furthermore, educators exhibit a deficiency in awareness and capabilities, which manifests in a singular and less effective teaching methodology. The shortage of practical platforms, guidance, and support emphasizes the pressing need for comprehensive innovation and EE systems. These issues necessitate collaborative efforts from universities, industry, and policymakers.

Internationally established solutions for the current challenges have substantially matured, providing invaluable insights and guidance for the development of EE in the Chinese context. In the late 20th century, the concept of the entrepreneurial university gained prominence (Etzkowitz et al., 2000 ). Then, entrepreneurial universities expanded their role from traditional research and teaching to embrace a “third mission” centered on economic development. This transformation entailed fostering student engagement in entrepreneurial initiatives by offering resources and guidance to facilitate the transition of ideas into viable entrepreneurial ventures. Additionally, these entrepreneurial universities played a pivotal role in advancing the triple helix (TH) model (Henry, 2009 ). The TH model establishes innovation systems that facilitate knowledge conversion into economic endeavors by coordinating the functions of universities, government entities, and industry. The robustness of this perspective has been substantiated through comprehensive theoretical and empirical investigations (Mandrup & Jensen, 2017 ).

Therefore, this study aims to explore how EE in Chinese universities can adapt to new societal trends and demands through the guidance of TH theory. This research involves two major themes: educational objectives and content. Educational objectives play a pivotal role in regulating the entire process of educational activities, ensuring alignment with the principles and norms of education (Whitehead, 1967 ), while content provides a practical pathway to achieving these objectives. Specifically, the study has three pivotal research questions:

RQ1: What is the present landscape of EE research?

RQ2: What unified macroscopic goals should be formulated to guide EE in Chinese higher education?

RQ3: What specific EE system should be implemented to realize the identified goals in Chinese higher education?

The structure of this paper is as follows: First, we conduct a comprehensive literature review on EE to answer RQ1 , thereby establishing a robust theoretical foundation. Second, we outline our research methodology, encompassing both framework construction and case studies and providing a clear and explicit approach to our research process. Third, we derive the objectives and content model of EE guided by educational objectives, entrepreneurial motivations, and entrepreneurial process theories. Fourth, focusing on a typical university in China as our research subject, we conduct a case study to demonstrate the practical application of our research framework. Finally, we end the paper with the findings for RQ2 and RQ3 , discussions on the framework, and conclusions.

Literature review

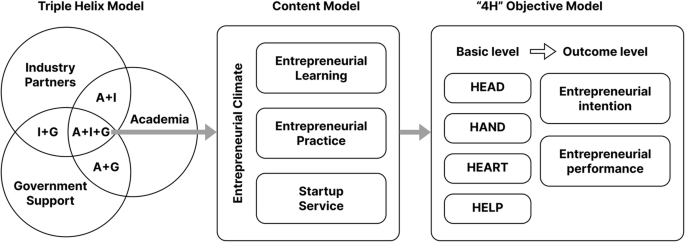

The notion of TH first appeared in the early 1980s, coinciding with the global transition from an industrial to a knowledge-based economy (Cai & Etzkowitz, 2020 ). At that time, the dramatic increase in productivity led to overproduction, and knowledge became a valuable mechanism for driving innovation and economic growth (Mandrup & Jensen, 2017 ). Recognizing the potential of incorporating cutting-edge university technologies into industry and facilitating technology transfer and innovation, the US government took proactive steps to enhance the international competitiveness of American industries. This initiative culminated in the enactment of relevant legislation in 1980, which triggered a surge in technology transfer, patent licensing, and the establishment of new enterprises within the United States. Subsequently, European and Asian nations adopted similar measures, promoting the transformation of universities’ identity (Grimaldi et al., 2011 ). Universities assumed a central role in technology transfer, the formation of businesses, and regional revitalization within the knowledge society rather than occupying a secondary position within the industrial community. The conventional one-to-one relationships between universities, companies, and the government evolved into a dynamic TH model (Cai & Etzkowitz, 2020 ). Beyond their traditional roles in knowledge creation, wealth production, and policy coordination, these sectors began to engage in multifaceted interactions, effectively “playing the role of others” (Ranga & Etzkowitz, 2013 ).

The TH model encompasses three fundamental elements: 1) In a knowledge-based society, universities assume a more prominent role in innovation than in industry; 2) The three entities engage in collaborative relationships, with innovation policies emerging as a result of their mutual interactions rather than being solely dictated by the government; and 3) Each entity, while fulfilling its traditional functions, also takes on the roles of the other two parties (Henry, 2009 ). This model is closely aligned with EE.

On the one hand, EE can enhance the effectiveness of TH theory by strengthening the links between universities, industry, and government. The TH concept was developed based on entrepreneurial universities. The emerging entrepreneurial university model integrates economic development as an additional function. Etzkowitz’s research on the entrepreneurial university identified a TH model of academia-industry-government relations implemented by universities in an increasingly knowledge-based society (Galvao et al., 2019 ). Alexander and Evgeniy ( 2012 ) articulated that entrepreneurial universities are crucial to the implementation of triple-helix arrangements and that by integrating EE into their curricula, universities have the potential to strengthen triple-helix partnerships and boost the effectiveness of the triple-helix model.

On the other hand, TH theory also drives EE to achieve high-quality development. Previously, universities were primarily seen as sources of knowledge and human resources. However, they are now also regarded as reservoirs of technology. Within EE and incubation programs, universities are expanding their educational capabilities beyond individual education to shaping organizations (Henry, 2009 ). Surpassing their role as sources of new ideas for existing companies, universities blend their research and teaching processes in a novel way, emerging as pivotal sources for the formation of new companies, particularly in high-tech domains. Furthermore, innovation within one field of the TH influences others (Piqué et al., 2020 ). An empirical study by Alexander and Evgeniy ( 2012 ) outlined how the government introduced a series of initiatives to develop entrepreneurial universities, construct innovation infrastructure, and foster EE growth.

Overview of EE

EE occupies a crucial position in driving economic advancement, and this domain has been the focal point of extensive research. Fellnhofer ( 2019 ) examined 1773 publications from 1975 to 2014, introducing a more closely aligned taxonomy of EE research. This taxonomy encompasses eight major clusters: social and policy-driven EE, human capital studies related to self-employment, organizational EE and TH, (Re)design and evaluation of EE initiatives, entrepreneurial learning, EE impact studies, and the EE opportunity-related environment at the organizational level. Furthermore, Mohamed and Sheikh Ali ( 2021 ) conducted a systematic literature review of 90 EE articles published from 2009 to 2019. The majority of these studies focused on the development of EE (32%), followed by its benefits (18%) and contributions (12%). The selected research also addressed themes such as the relationship between EE and entrepreneurial intent, the effectiveness of EE, and its assessment (each comprising 9% of the sample).

Spanning from 1975 to 2019, these two reviews offer a comprehensive landscape of EE research. The perspective on EE has evolved, extending into multiple dimensions (Zaring et al., 2021 ). However, EE does not always achieve the expected outcomes, as challenges such as limited student interest and engagement as well as persistent negative attitudes are often faced (Mohamed & Sheikh Ali, 2021 ). In fact, the challenges faced by EE in most countries may be similar. However, the solutions may vary due to contextual differences (Fred Awaah et al., 2023 ). Furthermore, due to this evolution, there is a need for a more comprehensive grasp of pedagogical concepts and the foundational elements of modern EE (Hägg & Gabrielsson, 2020 ). Based on the objectives of this study, four specific themes were chosen for an in-depth literature review: the objectives, contents and methods, outcomes, and experiences of EE.

Objectives of EE

The objectives of EE may provide significant guidance for its implementation and the assessment of its effectiveness, and EE has evolved to form a diversified spectrum. Mwasalwiba ( 2010 ) presented a multifaceted phenomenon in which EE objectives are closely linked to entrepreneurial outcomes. These goals encompass nurturing entrepreneurial attitudes (34%), promoting new ventures (27%), contributing to local community development (24%), and imparting entrepreneurial skills (15%). Some current studies still emphasize particular dimensions of these goals, such as fostering new ventures or value creation (Jones et al., 2018 ; Ratten & Usmanij, 2021 ). These authors further stress the significance of incorporating practical considerations related to the business environment, which prompts learners to contemplate issues such as funding and resource procurement. This goal inherently underscores the importance of entrepreneurial thinking and encourages learners to transition from merely being students to developing entrepreneurial mindsets.

Additionally, Kuratko and Morris ( 2018 ) posit that the goal of EE should not be to produce entrepreneurs but to cultivate entrepreneurial mindsets in students, equipping them with methods for thinking and acting entrepreneurially and enabling them to perceive opportunities rapidly in uncertain conditions and harness resources as entrepreneurs would. While the objectives of EE may vary based on the context of the teaching institution, the fundamental goal is increasingly focused on conveying and nurturing an entrepreneurial mindset among diverse stakeholders. Hao’s ( 2017 ) research contends that EE forms a comprehensive system in which multidimensional educational objectives are established. These objectives primarily encompass cultivating students’ foundational qualities and innovative entrepreneurial personalities, equipping them with essential awareness of entrepreneurship, psychological qualities conducive to entrepreneurship, and a knowledge structure for entrepreneurship. Such a framework guides students towards independent entrepreneurship based on real entrepreneurial scenarios.

Various studies and practices also contain many statements about entrepreneurial goals. The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework, which was issued by the EU in 2016, delineates three competency domains: ideas and opportunities, resources and action. Additionally, the framework outlines 15 specific entrepreneurship competencies (Jun, 2017 ). Similarly, the National Content Standards for EE published by the US Consortium encompass three overarching strategies for articulating desired competencies for aspiring entrepreneurs: entrepreneurial skills, ready skills, and business functions (Canziani & Welsh, 2021 ). First, entrepreneurial skills are unique characteristics, behaviors, and experiences that distinguish entrepreneurs from ordinary employees or managers. Second, ready skills, which include business and entrepreneurial knowledge and skills, are prerequisites and auxiliary conditions for EE. Third, business functions help entrepreneurs create and operate business processes in business activities. These standards explain in the broadest terms what students need to be self-employed or to develop and grow a new venture. Although entrepreneurial skills may be addressed in particular courses offered by entrepreneurship faculties, it is evident that business readiness and functional skills significantly contribute to entrepreneurial success (Canziani & Welsh, 2021 ).

Contents and methods of EE

The content and methods employed in EE are pivotal factors for ensuring the delivery of high-quality entrepreneurial instruction, and they have significant practical implications for achieving educational objectives. The conventional model of EE, which is rooted in the classroom setting, typically features an instructor at the front of the room delivering concepts and theories through lectures and readings (Mwasalwiba, 2010 ). However, due to limited opportunities for student engagement in the learning process, lecture-based teaching methods prove less effective at capturing students’ attention and conveying new concepts (Rahman, 2020 ). In response, Okebukola ( 2020 ) introduced the Culturo-Techno-Contextual Approach (CTCA), which offers a hybrid teaching and learning method that integrates cultural, technological, and geographical contexts. Through a controlled experiment involving 400 entrepreneurship development students from Ghana, CTCA has been demonstrated to be a model for enhancing students’ comprehension of complex concepts (Awaah, 2023 ). Furthermore, learners heavily draw upon their cultural influences to shape their understanding of EE, emphasizing the need for educators to approach the curriculum from a cultural perspective to guide students in comprehending entrepreneurship effectively.

In addition to traditional classroom approaches, research has highlighted innovative methods for instilling entrepreneurial spirit among students. For instance, students may learn from specific university experiences or even engage in creating and running a company (Kolb & Kolb, 2011 ). Some scholars have developed an educational portfolio that encompasses various activities, such as simulations, games, and real company creation, to foster reflective practice (Neck & Greene, 2011 ). However, some studies have indicated that EE, when excessively focused on applied and practical content, yields less favorable outcomes for students aspiring to engage in successful entrepreneurship (Martin et al., 2013 ). In contrast, students involved in more academically oriented courses tend to demonstrate improved intellectual skills and often achieve greater success as entrepreneurs (Zaring et al., 2021 ). As previously discussed, due to the lack of a coherent theoretical framework in EE, there is a lack of uniformity and consistency in course content and methods (Ribeiro et al., 2018 ).

Outcomes of EE

Research on the outcomes of EE is a broad and continually evolving field, with most related research focusing on immediate or short-term impact factors. For example, Anosike ( 2019 ) demonstrated the positive effect of EE on human capital, and Chen et al. ( 2022 ) proposed that EE significantly moderates the impact of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial competencies in higher education students through an innovative learning environment. In particular, in the comprehensive review by Kim et al. ( 2020 ), six key EE outcomes were identified: entrepreneurial creation, entrepreneurial intent, opportunity recognition, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and orientation, need for achievement and locus of control, and other entrepreneurial knowledge. One of the more popular directions is the examination of the impact of EE on entrepreneurial intentions. Bae et al. ( 2014 ) conducted a meta-analysis of 73 studies to examine the relationship between EE and entrepreneurial intention and revealed little correlation. However, a meta-analysis of 389 studies from 2010 to 2020 by Zhang et al. ( 2022 ) revealed a positive association between the two variables.

Nabi et al. ( 2017 ) conducted a systematic review to determine the impact of EE in higher education. Their findings highlight that studies exploring the outcomes of EE have primarily concentrated on short-term and subjective assessments, with insufficient consideration of longer-term effects spanning five or even ten years. These longer-term impacts encompass factors such as the nature and quantity of startups, startup survival rates, and contributions to society and the economy. As noted in the Eurydice report, a significant impediment to advancing EE is the lack of comprehensive delineation concerning education outcomes (Bourgeois et al., 2016 ).

Experiences in the EE system

With the deepening exploration of EE, researchers have turned to studying university-centered entrepreneurship ecosystems (Allahar and Sookram, 2019 ). Such ecosystems are adopted to fill gaps in “educational and economic development resources”, such as entrepreneurship curricula. A growing number of universities have evolved an increasingly complex innovation system that extends from technology transfer offices, incubators, and technology parks to translational research and the promotion of EE across campuses (Cai & Etzkowitz, 2020 ). In the university context, the entrepreneurial ecosystem aligns with TH theory, in which academia, government, and industry create a trilateral network and hybrid organization (Ranga & Etzkowitz, 2013 ).

The EE system is also a popular topic in China. Several researchers have summarized the Chinese experience in EE, including case studies and overall experience, such as the summary of the progress and system development of EE in Chinese universities over the last decade by Weiming et al. ( 2013 ) and the summary of the Chinese experience in innovation and EE by Maoxin ( 2017 ). Other researchers take an in-depth look at the international knowledge of EE, such as discussions on the EE system of Denmark by Yuanyuan ( 2015 ), analyzes of the ecological system of EE at the Technical University of Munich by Yubing and Ziyan ( 2015 ), and comparisons of international innovation and EE by Ke ( 2017 ).

In general, although there has been considerable discussion on EE, the existing body of work has not properly addressed the practical challenges faced by EE in China. On the one hand, the literature is fragmented and has not yet formed a unified and mature theoretical framework. Regarding what should be taught and how it can be taught and assessed, the answers in related research are ambiguous (Hoppe, 2016 ; Wong & Chan, 2022 ). On the other hand, current research lacks empirical evidence in the context of China, and guidance on how to put the concept of EE into practice is relatively limited. These dual deficiencies impede the effective and in-depth development of EE in China. Consequently, it is imperative to comprehensively redefine the objectives and contents of EE to provide clear developmental guidance for Chinese higher education institutions.

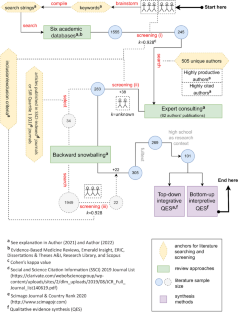

Research methodology

To answer the research questions, this study employed a comprehensive approach by integrating both literature-based and empirical research methods. The initial phase focused on systematically reviewing the literature related to entrepreneurial education, aiming to construct a clear set of frameworks for the objectives and content of EE in higher education institutions. The second phase involved conducting a case study at T-University, in which the theoretical frameworks were applied to a real-world context. This case not only contributed to validating the theoretical constructs established through the literature review but also provided valuable insights into the practical operational dynamics of entrepreneurial education within the specific university setting.

Conceptual framework stage

This paper aims to conceptualize the objective and content frameworks for EE. The methodology sequence is as follows: First, we examine the relevant EE literature to gain insights into existing research themes. Subsequently, we identify specific research articles based on these themes, such as “entrepreneurial intention”, “entrepreneurial self-efficacy”, and “entrepreneurial approach”, among others. Third, we synthesize the shared objectives of EE across diverse research perspectives through an analysis of the selected literature. Fourth, we construct an objective model for EE within higher education by integrating Bloom’s educational objectives ( 1956 ) and Gagne’s five learning outcomes ( 1984 ), complemented by entrepreneurship motivation and process considerations. Finally, we discuss the corresponding content framework.

Case study stage

To further elucidate the conceptual framework, this paper delves into the methods for the optimization of EE in China through a case analysis. Specifically, this paper employs a single-case approach. While a single case study may have limited external validity (Onjewu et al., 2021 ), if a case study informs current theory and conceptualizes the explored issues, it can still provide valuable insights from its internal findings (Buchanan, 1999 ).

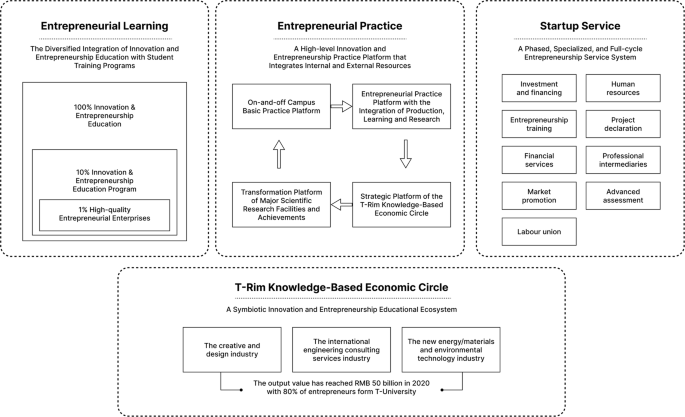

T-University, which is a comprehensive university in China, is chosen as the subject of the case study for the following reasons. First, T-University is located in Shanghai, which is a Chinese international technological innovation center approved by the State Council. Shanghai’s “14th Five-Year Plan” proposes the establishment of a multichannel international innovation collaboration platform and a global innovation cooperation network. Second, T-University has initiated curriculum reforms and established a regional knowledge economy ecosystem by utilizing EE as a guiding principle, which aligns with the characteristics of its geographical location, history, culture, and disciplinary settings. This case study will showcase T-University’s experiences in entrepreneurial learning, entrepreneurial practice, startup services, and the entrepreneurial climate, elucidating the positive outcomes of this triangular interaction and offering practical insights for EE in other contexts.

The data collection process of this study was divided into two main stages: field research and archival research. The obtained data included interview transcripts, field notes, photos, internal documents, websites, reports, promotional materials, and published articles. In the initial stage, we conducted a 7-day field trip, including visits to the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Institute, the Career Development Centre, the Academic Affairs Office, and the Graduate School. Moreover, we conducted semistructured interviews with several faculty members and students involved in entrepreneurship education at the university to understand the overall state of implementation of entrepreneurship education at the university. In the second stage, we contacted the Academic Affairs Office and the Student Affairs Office at the university and obtained internal materials related to entrepreneurship education. Additionally, we conducted a comprehensive collection and created a summary of publicly available documents, official school websites, public accounts, and other electronic files. To verify the validity of the multisource data, we conducted triangulation and ultimately used consistent information as the basis for the data analysis.

For the purpose of our study, thematic analysis was employed to delve deeply into the TH factors, the objective and content frameworks, and their interrelationships. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within data. This approach emphasizes a comprehensive interpretation of the data, as it extracts information from multiple perspectives and derives valuable conclusions through summary and induction (Onjewu et al., 2021 ). Therefore, thematic analysis likely serves as the foundation for most other qualitative data analysis methods (Willig, 2013 ). In this study, three researchers individually conducted rigorous analyses and comprehensive reviews to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data. Subsequently, they engaged in collaborative discussions to explore their differences and ultimately reach a consensus.

Framework construction

Theoretical basis of ee in universities.

The study is grounded in the theories of educational objectives, planned behavior, and the entrepreneurial process. Planned behavior theory can serve to elucidate the emergence of entrepreneurial activity, while entrepreneurial process theory can be used to delineate the essential elements of successful entrepreneurship.

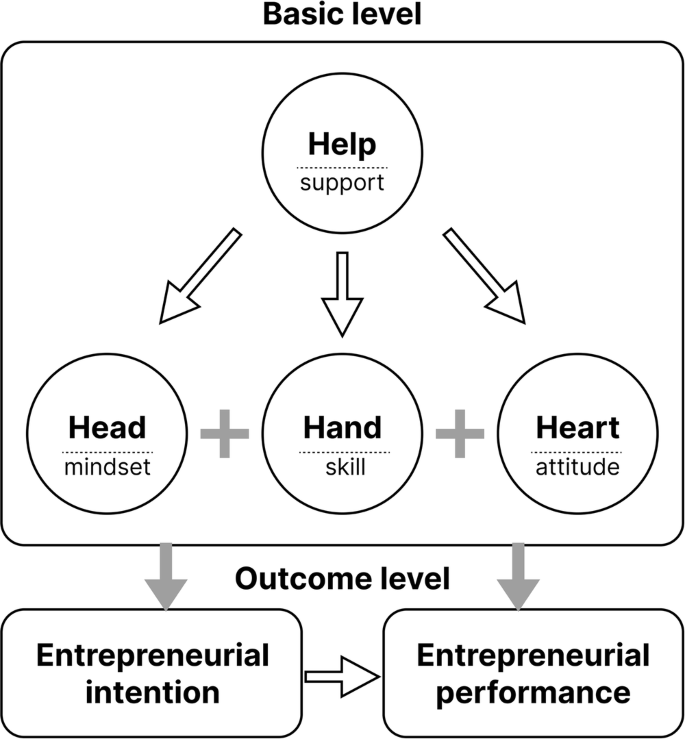

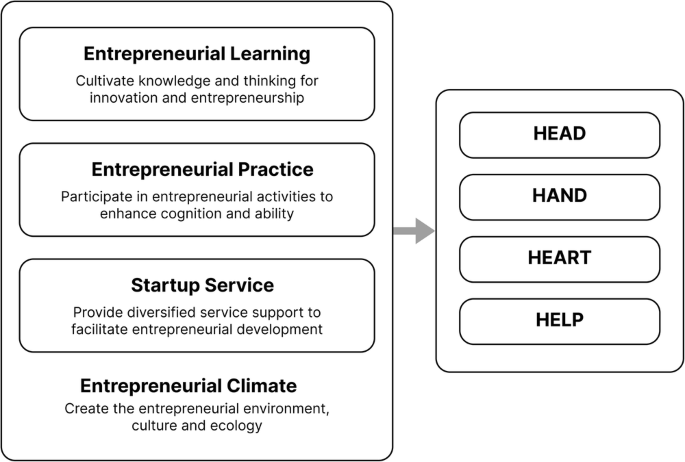

Theory of educational objectives. The primary goal of education is to assist students in shaping their future. Furthermore, education should directly influence students and facilitate their future development. Education can significantly enhance students’ prospects by imparting specific skills and fundamental principles and cultivating the correct attitudes and mindsets (Bruner, 2009 ). According to “The Aims of Education” by Whitehead, the objective of education is to stimulate creativity and vitality. Gagne identifies five learning outcomes that enable teachers to design optimal learning conditions based on the presentation of these outcomes, encompassing “attitude,” “motor skills,” “verbal information,” “intellectual skills,” and “cognitive strategies”. Bloom et al. ( 1956 ) argue that education has three aims, which concern the cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains. Gedeon ( 2017 ) posits that EE involves critical input and output elements. The key objectives encompass mindset (Head), skill (hand), attitude (heart), and support (help). The input objectives include EE teachers, resources, facilities, courses, and teaching methods. The output objectives encompass the impacts of the input factors, such as the number of students, the number of awards, and the establishment of new companies. The primary aims of Gedeon ( 2017 ) correspond to those of Bloom et al. ( 1956 ).

Theory of planned behavior. The theory of planned behavior argues that human behavior is the outcome of well-thought-out planning (Ajzen, 1991 ). Human behavior depends on behavioral intentions, which are affected by three main factors. The first is derived from the individual’s “attitude” towards taking a particular action; the second is derived from the influence of “subjective norms” from society; and the third is derived from “perceived behavioral control” (Ajzen, 1991 ). Researchers have adopted this theory to study entrepreneurial behavior and EE.

Theory of the entrepreneurship process. Researchers have proposed several entrepreneurial models, most of which are processes (Baoshan & Baobao, 2008 ). The theory of the entrepreneurship process focuses on the critical determinants of entrepreneurial success. The essential variables of the entrepreneurial process model significantly impact entrepreneurial performance. Timmons et al. ( 2004 ) argue that successful entrepreneurial activities require an appropriate match among opportunities, entrepreneurial teams, resources, and a dynamic balance as the business develops. Their model emphasizes flexibility and equilibrium, and it is believed that entrepreneurial activities change with time and space. As a result, opportunities, teams, and resources will be unbalanced and need timely adjustment.

4H objective model of EE

Guided by TH theory, the objectives of EE should consider universities’ transformational identity in the knowledge era and promote collaboration among students, faculty, researchers, and external players (Mandrup & Jensen, 2017 ). Furthermore, through a comprehensive analysis of the literature and pertinent theoretical underpinnings, the article introduces the 4H model for the EE objectives, as depicted in Fig. 1 .

The 4H objective model of entrepreneurship education.