An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Behav Sci (Basel)

Impact of Films: Changes in Young People’s Attitudes after Watching a Movie

Nowadays films occupy a significant portion of the media products consumed by people. In Russia, cinema is being considered as a means of individual and social transformation, which makes a contribution to the formation of the Russian audience’s outlook, including their attitudes towards topical social issues. At the same time, the question of the effectiveness of films’ impact remains an open question in psychological science. According to the empirical orientation of our approach to the study of mass media influence, our goal was to obtain new data on the positive impact of films based on specific experimental research. The task was to identify changes in the attitudes of young people, as the most active viewers, towards topical social issues after watching a specifically selected film. Using a psychosemantic technique that included 25 scales designed to identify attitudes towards elderly people, respondents evaluated their various characteristics before and after watching the film. Using a number of characteristics related to the motivational, emotional and cognitive spheres, significant changes were revealed. At the same time, significant differences were found in assessments of the elderly between undergraduate students and postgraduate students. After watching the film, postgraduate students’ attitudes towards elderly people changed in a positive way, while undergraduate students’ negative assessments only worsened. The revealed opposite trends can be explained by individual differences of respondents, which include age, educational status as an indicator of individual psychological characteristics, the experience of interaction with elderly people and, as a result, attitudes towards elderly people at the time before watching the movie. The finding that previous attitudes mediate the impact of the film complements the ideas of the contribution of individual differences to media effects. Most of the changes detected immediately after watching the movie did not remain over time. A single movie viewing did not have a lasting effect on viewers’ attitudes, and it suggests the further task of identifying mechanisms of the sustainability of changes.

1. Introduction

With the development of information technology, a person’s immersion in the field of mass media is steadily increasing. A significant portion of consumed media products is occupied by cinema. According to sociological surveys, going to the cinema is the most popular way of spending leisure time in Russia today ( http://www.fond-kino.ru/news/kto-ty-rossijskij-kinozritel/ ); the audiences of cinemas are growing, the core of which are 18-24 years olds, as well as the frequency of visits—every tenth Russian goes to the cinema several times a month ( https://wciom.ru/index.php?id=236&uid=1785 ; https://wciom.ru/fileadmin/file/reports_conferences/2018/2018-04-03_kino.pdf ; http://www.fond-kino.ru/news/portret-kinoauditorii-rezultaty-monitoringa-za-i-kvartal-2019-goda/ ), the opportunities and frequency of Internet viewings is expanding, while interest in TV shows is also increasing. The importance of the role that cinema plays in Russia is also confirmed by the close attention currently being paid to the development of the cinema industry: the priority topics of state financing are defined (e.g., “Law and order: the heroes of modern society in the fight against crime terror, extremism and corruption”, “On the continuity of military generations, on the successors of military traditions”, "Images, patterns of behavior and creative motivation of our contemporary—a man of labor, in the military or a scientist"), while state programs are being launched to open new cinema theatres in small towns. Сinema becomes a “tool for broadcasting state ideology to the masses” (according to S. Zizek [ 1 ]), and is also being considered as a “means of individual and social transformation” (according to T. Kashani [ 2 ]) [ 3 ]. As a result, films are expected to form beliefs, influence opinions and change attitudes, including towards topical social issues.

However, the question of the efficiency of films remains open in psychology. In general, this is a key issue for mass communication research: how much emotion, cognition and behavior are changed under the influence of mass media [ 4 , 5 ]. There are various concepts about this: from “theories of a minimal effect” to “theories of a strong effect” [ 6 ]. Thus, for example, cultivation theory considers that mass communication contributes to the assimilation of commonly accepted values, norms and forms of behavior [ 7 ]; and a meta-analysis of studies leads to the conclusion that there is a relationship between the broadcast mass media image of reality and people’s attitudes towards it [ 8 , 9 ]. Despite criticisms, cultivation theory is currently being developed [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. On the other hand, supporters of the opposite viewpoint point out the weak effects of mass communication, caused, for example, by the fact that people are becoming more and more subject of their mass media activity as a result of a wider variety of sources of information now and expanding their choices [ 14 , 15 ].

It seems difficult to identify a single mechanism of mass media impact on the human psyche and behavior and to obtain an unambiguous answer to the question about its efficiency [ 6 ]. This is due to the interconnection of various factors that mediate the influence of mass media (personal experience, realistic content, depth of identification with heroes, personality traits, etc.) [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], as well as those factors that constantly impact persons besides those in the media. Therefore, our thoughts and ideas about this issue are largely based on empirical research data, and are not limited to one theory [ 19 ].

When referring to research of cinema, we can find data on the diverse effects of film exposure. It should be noted that the effectiveness of the impact is determined by what it is directed at: it is more difficult to change human behavior than to influence opinions or attitudes [ 4 , 6 ]. In this regard, there is still a debatable problem on the influence of the media on the aggressive behavior of people [ 20 ]. This research focuses on the potential of pro-social, "humanistic" impact of films and their effectiveness in solving topical social issues. The studies reveal the influence of films on people’s beliefs and opinions, stereotypes and attitudes. Movies can have a significant impact on gender and ethnic stereotypes [ 21 , 22 ], change attitudes towards certain groups of people and cause newly formed opinions on various issues. For example, HIV films contributed to sympathy to people living with HIV [ 4 ], TV series with transgender characters contributed to positive attitudes towards transgender persons [ 23 ]; the portrayal of mental disorders in movies had an effect on people’s knowledge about and attitudes toward the mentally ill [ 24 , 25 ]. Also, viewing an empathy-arousing film about immigrants induced more positive attitudes toward them [ 26 ], and watching a movie offering a positive depiction of gay men reduced homophobia [ 27 ]. Other films influenced people’s attitude towards smoking and their intentions to quit [ 28 , 29 ], while a series with a positive donation message helped viewers to make decisions about their own donation [ 30 ]. It has been shown that emotional involvement in viewing, evaluated using surveys drawing on theories of social learning and social representations, increases the effectiveness of influence [ 30 ]; immersion in narrative, that correlates with the need for cognition, and is characterized by a shift of focus from the real world to the depicted one, explains the power of impact within the framework of transportation theory [ 31 , 32 ].

Cinema can change people’s opinions on specific issues without affecting more stable constructs: for example, the film “JFK” dedicated to the Kennedy assassination influenced judgments about the causes of this crime, but generally did not change the political beliefs of the audience [ 33 ]; at the same time, the movies “Argo” and “Zero Dark Thirty” changed viewers’ opinions about the U.S. government that reflected in an improvement in sentiments about this government and its institutions [ 34 ]. Movies create images of other countries and stimulate interest in them. For example, European films shaped young viewers’ ideas about other European countries—such results were obtained in a study of the role of films and series in the daily life of young Germans through interviews and focus groups [ 35 ]. Another study showed that whether the movies were violent, scary or happy, the more the viewers were immersed in the stories, the more favorable impressions they had of the places featured in them [ 36 ].

Various positive effects of films on children and adolescents were revealed. Dramatic films taught teenagers about social interaction with the opposite sex and adults [ 37 ], had a positive impact on their self-concept [ 38 ], and, as shown by experiments, increased ethnic tolerance [ 39 ]; humanistically oriented movies improved skills of children in communicating with peers, increased their desire to help and understand others [ 40 , 41 ].

One of the prime examples of positive impact is Cli-fi movies, which clearly show what we can expect in the near future, and offers ways to think about what can be done to avoid the darkest predictions. Thus, after watching the film “The Day After Tomorrow” (2004), viewers recognized their responsibility for the Earth’s ecology and the need to change consumer attitudes towards nature [ 42 ]. In general, the screening of films on climate issues increases the number of online requests and media discussions on these issues [ 43 ].

It should be noted that when analyzing the impact of films, conclusions about their effectiveness are the result of different methodological approaches, which have varying advantages and limitations. Content analysis reveals the images, attitudes, stereotypes broadcast by films (e.g., stereotypical portrayals of India [ 44 ], or images of scientists and current scientific ideas [ 45 ]) on large data sets; however, questions remain about effectiveness, strength and sustainability of the impact on the audience. The influence of films can be investigated through a survey of viewers; based on this, conclusions are drawn about the links between a person’s attitudes and his/her viewer experience, such as in the study of gender attitudes and their correlations with teen movie-viewing habits [ 21 ]. In experimental studies, exposure effects are detected using pre- and post-film questionnaires; however, the time interval between testing and a film screening, such as a few weeks before viewing the film or a several days after [ 26 , 27 , 29 ], can lead to distortion of the results that are caused by the influence on the viewers’ attitudes of other factors besides the film; moreover, usually it is not investigated whether new attitudes are retained over time. Often the effects of films are analyzed in experimental conditions where participants watch only short cut scenes from existing films [ 24 ], which limits the extrapolation of the results.

According to the empirical orientation of our approach, the goal was to obtain new data on the positive impact of films based on a specific experimental study. The task was to identify changes in young people’s attitudes towards topical social issues after watching a specifically selected film. Participants had to watch the full version of an existing fiction film. They were tested just before and immediately after watching the movie in order to avoid the influence of other variables on viewers’ attitudes. Repeated testing (two weeks after the first viewing) was intended to reveal the sustainability of the changes caused by the film.

In the process of developing the design of the work, it was specified what attitudes would be studied. The choice was determined, first of all, by the social relevance of the topic, but outside the focus of the media in order to reduce the impact of other media sources, and on the other hand, by the availability of a suitable film. Important topics as ethnic stereotypes, attitudes toward people with disabilities, etc. were considered. However, the choice of the topics had to be restricted for various reasons. For example, identifying attitudes toward certain professions (e.g., engineer), whose prestige has significantly declined in Russia in recent decades, was difficult due to the lack of relevant films popularizing them. At the same time, despite the availability of humanistically oriented films dedicated to people with disabilities, the identification of changes in attitudes to them was complicated by the need to take into account additional factors caused by increased attention to the topic and active discussion in various media, which could distort the influence of a film.

Given the limitations and opportunities for the implementation of research tasks, the subject of this study the attitudes towards elderly people. At present, attention to the topic concerning elderly people is growing in Russia, but there is still a prevalence of negative stereotypes [ 46 ]. A characteristic manifestation of age discrimination against the elderly—ageism—is a biased attitude towards them, especially among young people, as well as a low assessment of their intellectual abilities, activity and "usefulness" for society.

Studies show that the mass media have a significant impact on negative attitudes towards the elderly [ 47 ]: children have already demonstrated the same stereotypes of the elderly that were depicted in the media [ 48 ], while young people at large viewed the elderly in general as ineffective, dependent, lonely, poor, angry and disabled, which corresponded to the negative representations of elderly people in the most popular teen movies that cultivated their stereotypes [ 49 ]. Research of TV films from the 1980s–1990s revealed the stereotypes of elderly people as being social outsiders [ 50 ], but at the same time a display of positive prejudice contributed to an increase in tolerance towards them within society.

Improving the attitudes of young people towards elderly people is an important social and educational task, the solution of which involves the use of diverse opportunities. Various social projects can be implemented for this purpose, for example, "friendly visitor" types of programs in which young people visit the elderly [ 51 , 52 ], but also mass media, including films, which have a high potential for impact [ 53 , 54 ]. It was found that watching documentary films had a positive effect on both knowledge about aging and attitudes towards the elderly [ 55 ]; these films significantly improved empathy towards elderly people among university students [ 56 ].

We suggested that fiction movies, popular especially among young people, could contribute to changing existing biased attitudes towards elderly people. Based on this, the hypothesis states that there is a connection between watching a positive film about the elderly and changes in young people’s attitudes towards them in a positive way.

2.1. Participants

A total of 70 individuals participated in this study. Group one contained 40 students of The State Academic University for Humanities (25% male and 75% female). The average age was 19 (M = 19, standard deviation SD = 2.4). Group two consisted of 30 postgraduate students from Russian Academy of Sciences (47% male and 53 % female). The average age was 24 (M = 24, standard deviation SD = 1.6).

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (Review Board).

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. film.

The film—“The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” (2011), the main characters of which were elderly people, was chosen to be shown to the respondents ( https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1412386/ ). Prior to this, a qualitative analysis of empirical material revealed the impact of this film on the attitudes towards elderly people among Russian viewers of different ages. Their reviews on the film, taken from Internet resources devoted to cinema, indicated cognitive effects, expressed in positive changes of ideas about the elderly; the film was perceived quite optimistically and gave hope [ 19 ]. It was supposed that the movie that humorously shows various situations happening to the elderly heroes would also affect the opinion of young people about elderly people, as it allowed to look at them from new viewpoints, to see that age is not an obstacle to having a full life, and even, conversely, open up new prospects.

2.2.2. Measures

To achieve the goal of the study, a psychosemantic approach is used, which is the most appropriate for studying a person’s attitudes towards various objects of reality by reconstructing individual meanings [ 57 ]. This approach allows us to determine the differences in evaluations of the same object (caused by mass media as well), made by different groups of respondents at different times. For example, changes in the stereotypes of viewers were revealed in relation to representatives of another nation (Russians about the Japanese) during viewing of a TV show [ 57 ]. In this work, the psychosemantic technique was used, developed specifically to identify attitudes towards the elderly (based on the Kelly’s Repertoire lattice method) [ 46 ]. The technique included 25 7-point scales, according to which respondents rated elderly people. For comparative analysis, the modern youth were evaluated by participants with the same scales.

The respondents also noted the frequency of watching movies ("every day"/"several times a week"/"several times a month"/"several times a year and less"), and evaluated the level of enjoying the film shown ("did not like"/"rather did not like than liked"/"rather liked than disliked"/"liked").

2.3. Procedure

The study was conducted in three stages: the respondents filled out the psychosemantic test before watching the film, then immediately after viewing and again in 2 weeks. During stage 3, only group one participated in the study.

The respondents did not see the film before participating in the study.

2.4. Statistical Methods

In accordance with the data characteristics, non-parametric comparative methods were used. To determine the differences in the assessments before and after watching the movie, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. To determine the differences in the assessments between different groups of respondents, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. The IBM SPSS Statistics 20 statistical software package was used for data processing.

3. Results and Discussion

As a result of the preliminary data analysis of the group one (students), significant differences were obtained in the assessments given by them to the elderly before and immediately after watching the movie (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.05). However, the analysis of the combined sample (students and postgraduate students) did not reveal such significant differences. Therefore, it was decided to compare the assessments of these two groups of respondents. It appeared that the evaluation of elderly people differed among students and postgraduate students before the film was shown (18 of 25 scales, Mann—Whitney test, p < 0.05). This result could be explained by the individual differences of the participants (students and postgraduates), which led to the necessity to correct the hypothesis and form additional research tasks, including the comparison of groups. Further analysis was carried out separately for each group of respondents, but not for the united group.

Significant differences shown by respondents of the group one before and immediately after watching the film (students) were found in 12 out of the 25 scales ( Table 1 ).

Changes in assessments of the elderly people after watching the film (students).

Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Only the significant differences are represented: b—based on negative ranks, c—based on positive ranks. * inversive scales: a higher rating means a more negative attitude

The group of students revealed changes associated with ideas about activities. The respondents saw the elderly as having less initiative, and being purposeless and weak. Moreover, they defined elderly people’s way of life as more passive, having no desire for knowledge or for living a full life. The results immediately after watching the film demonstrated that the audience perceived the elderly as being those who strived less to learn new things and perceived them to be less positive and more limited in their interests. Also, the changes of assessments related to the emotional sphere were discovered. The elderly were characterized as even more unrestrained and conflict-prone with a tendency towards depression and showing no emotions.

Comparative analysis of assessments of elderly people before and after watching the film, given by respondents of the group two (postgraduate students), showed significant differences on 14 of the 25 scales ( Table 2 ). Postgraduate students evaluated the elderly, unlike students, more positively after watching the film. Changes on 9 common scales (purposeless - purposeful, cheerful - prone to depression, passive - initiative, conflict - peaceful, traditional - modern, etc.) for students and postgraduate students turned out to be of different directions. After watching the film, the elderly seemed to be more purposeful, active and successful, responsible and with a good sense of humor. There were changes in assessments of the emotional sphere (more cheerful, peaceful) and cognitive (more intelligent) in references to novelty and life in general (the strive to learn new things, the desire for a full life).

Changes in assessments of elderly people after watching the film (postgraduates).

Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The significant differences are only represented: b—based on positive ranks, c—based on negative ranks. * inversive scales: higher rating means more negative attitude.

Thus, the data revealed changes in attitude towards the elderly people after watching the film. According to a number of their characteristics related to motivational aspects—regulatory, emotional and cognitive spheres—significant changes were revealed, but the tendency of these changes was unexpected. After group one (students) watched the film, a tendency of worsening assessments was found. It was also determined that before the film, students described the elderly more negatively as being less intelligent and interesting, more conflict prone, angry and aggressive than young people (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.01). This generally negative attitude can be explained by a special view of quite young people on the "old age". But why, despite the attempt of the filmmakers to make the image of the elderly positive enough, did the film fail to change students’ attitude? Instead, it made the image of elderly persons even less attractive. Meanwhile, there was an opposite trend in group two (postgraduate students). Their assessments of elderly people after watching the film changed for the better. The postgraduate students, unlike undergraduate students, had already demonstrated a more "adequate" view on the elderly before watching the film. Despite a number of negative assessments, the elderly were seen by them as smart and striving for a full life, sociable and interesting.

Comparison of the two groups of respondents confirmed significant differences between students and postgraduate students in the evaluation of the elderly after watching the film ( Table 3 ). The assessments given by undergraduate students and postgraduates differed significantly on 21 out of 25 scales.

Comparison of groups of undergraduate students and postgraduates by assessments after watching the film.

Mann-Whitney U test. The significant differences are only represented.

The opposite tendencies found in assessments after watching the film could be explained by differences in individual characteristics of respondents, which were not initially considered in our study as factors mediating the impact of the film: age of respondents (more subtle differentiation), educational status, as an indicator of individual psychological characteristics and experiences of interactions with elderly people. The suggestion of differences between students and postgraduates by personality is consistent with the results of other studies [ 58 ], and is indirectly confirmed by the fact that only about 1 out of 40 students become postgraduate students (data for Russia). In our study, differences between students and postgraduate students already manifested in differences in their attitudes towards the elderly before watching the film.

Then the film, which showed some negative aspects of life for elderly people (loneliness, needlessness, diseases, fears, physical limitations “comic” behavior), despite the optimistic ending, could strengthen the negative attitudes of very young people (students) towards the elderly, whose images might not yet be fully formed. On the other hand, postgraduate students might have a more complex view on elderly people, because of age and more diverse interactions with the elderly, for example, in scientific work. In this case, their perceptions of the film could be focused on its positive ideas, strengthening their previously formed positive image of an elderly person. In addition, postgraduate students, who have chosen the scientific career path, most likely have a high level of analytical skills that contributed to more complex perceptions of the world and a deep assessment of the phenomena that could affect their attitudes towards the older generation and the interpretation of their images in the movies. At the same time, the characteristics of the film itself, as well as the cultural differences between its creators and viewers, might cause additional negative impacts on students’ perceptions. Comedy, as a genre, could have an opposite effect. Younger people perceived the desire of older characters to give their lives new meanings in their own way and they saw a futility in these attempts. Respondents with more experience could be more tolerant to the specifics of the genre, and their perception of the film was more complicated and implemented in a broader context.

Thus, comparison of the results of the analysis for both groups of respondents suggests that the different changes in viewers’ attitudes towards objects of reality that occur after watching a movie can be explained by differences in the attitudes before watching the film. This effect can also be explained by the degree of identification with the characters [ 31 , 59 , 60 ], which is influenced by the previous attitudes of the viewers. For example, a study of the impact of films on attitudes towards migrants showed that greater identification with the characters induced more positive attitudes toward immigration, but only when previous prejudice was low or moderate [ 26 ]. In this regard, the various effects of the film on students and postgraduate students could be caused by the different degrees of their identification with the characters of the film, despite the fact that a large difference in age with the characters could complicate this process for all participants in the study. The conclusion that previous attitudes mediate the impact of the film complements the ideas of the contribution of individual differences to media effects [ 61 ]. In addition, this conclusion has practical value: in order to achieve the desired impact of films, it is necessary to identify the viewers’ individual attitudes before a screening.

At the third stage of the study, it was examined whether changes remained over time. Two weeks after watching the movie, respondents (group one) re-took the test.

Significant differences were found only on 4 scales (strives to a full life - lost the meaning of life, craving for spirituality - limited interests, quickly tired – high in stamina, traditional - modern) ( Table 4 ). The continuing changes in the characteristics related to the inferiority and limitations of elderly people’s lives may indicate the most striking and memorable moments in the film that had the greatest impact on viewers. The assessments of the other characteristics did not differ significantly from those that were identified before watching the film. That leads to the conclusion that a single movie viewing, in general, did not have a lasting effect on the viewers’ attitudes toward the elderly. Most of the changes discovered immediately after watching the movie did not remain over time. Studying the mechanisms of the formation of sustainable changes is a task for future research. One of the directions of such research could be to investigate the influence of additional cognitive processing (e.g., discussion after watching the movie) on the viewers’ attitudes towards objects and the sustainability of changes over time.

Changes in assessments of the elderly people 2 weeks after watching the film (students).

Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Only the significant differences are represented: b—based on negative ranks, c—based on positive ranks. * inversive scales: a higher rating means a more negative attitude.

The correlation between the gender of the respondents and changes in attitudes after watching the film was determined by comparing the assessments separately for males and females in each group. As a result, in group one, women were found to have significant differences in ratings on 13 scales, and men in three, two of which were common (no desire to learn anything - the desire to learn new skills, traditional - modern, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.05). The data showed greater changes in the attitudes among women than among men after watching the film. At the same time, a comparison of the male and female participants in the group two did not reveal such results. The analysis found an equal number of significant differences in assessments (on 10 scales) before and after watching the film (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.05). Thus, it can be assumed that gender had a lower impact on changes in attitudes after watching a film than other individual characteristics of respondents.

The data on the frequency of watching movies was obtained: 56% of respondents watch movies several times a week and more often, 44%—several times a month and less often. However, there were no differences between these viewers in the assessments before and after watching the film (Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05). The degree of general interest in cinema did not affect the change of viewers’ attitudes after watching the film.

It was not possible to determine the connection between liking the film and the changes in attitudes, since the differentiation of respondents by this factor was not found. Only six young people noted they did not like the film, while the others gave it a positive evaluation.

The study has limitations caused due to an assumption of no significant differences between students and postgraduates in the effectiveness of the film’s impact on them. The revealed differences between undergraduate students and postgraduate students led to the initial sample of young people being divided into two samples with smaller sizes already used during the research. In addition, for the same reason, some variables that could more accurately demonstrate the differences between students and postgraduate students and explain the effects of the film were not considered. The respondents’ attitudes before watching the film were taken into account, as well as additional factors on the impact effectiveness, such as the degree of general interest in cinema and liking of the viewed film, which could presumably increase its impacts. But a deeper study, for example, of the processes of identifying viewers with the film characters, probably linked to the viewers’ attitudes before watching, could reinforce these findings.

4. Conclusions

As a result of the study, changes in the viewers’ attitudes after watching the film were identified. Young people changed their assessments of regulatory, cognitive and emotional characteristics of the elderly people after watching a film about the elderly. At the same time, significant differences were found between students and postgraduate students in their assessments of the elderly. After watching the film, students’ negative attitudes towards elderly people got worse, while postgraduate students’ assessments, on the contrary, changed for the better. The revealed opposite trends can be explained by individual differences between the respondents, which include age, educational status as an indicator of individual psychological characteristics, experience of interaction with elderly people and, as a result, attitudes towards elderly people at the time before watching the film. Most of the changes in the viewers’ attitudes detected immediately after watching the movie did not remain over time.

In general, the study confirms the potential for a positive impact, as in the case of improving the postgraduates’ attitudes, but at the same time demonstrates the need to take into account the individual differences of viewers to achieve desired results. In particular, differences in attitudes before watching a movie are probably causes of differences in the effectiveness of the film’s impact. The initially negative attitude towards elderly people among students could contribute to the negative influence of the film on them. The obtained results form the basis of further research and pose the important questions: clarifying the contribution of individual differences to the effectiveness of the impact, forecasting the positive influence of movies on different groups of people and determining the mechanisms of the sustainability of changes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the engagement and involvement of the research participants.

The research was carried out within a state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, project №0159-2019-0005.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Essay on Impact of Cinema in Life for Students and Children

500 words essay on impact of cinema in life.

Cinema has been a part of the entertainment industry for a long time. It creates a massive impact on people all over the world. In other words, it helps them give a break from monotony. It has evolved greatly in recent years too. Cinema is a great escape from real life.

Furthermore, it helps in rejuvenating the mind of a person. It surely is beneficial in many ways, however, it is also creating a negative impact on people and society. We need to be able to identify the right from wrong and make decisions accordingly.

Advantages of Cinema

Cinema has a lot of advantages if we look at the positive side. It is said to be a reflection of the society only. So, it helps us come face to face with the actuality of what’s happening in our society. It portrays things as they are and helps in opening our eyes to issues we may have well ignored in the past.

Similarly, it helps people socialize better. It connects people and helps break the ice. People often discuss cinema to start a conversation or more. Moreover, it is also very interesting to talk about rather than politics and sports which is often divided.

Above all, it also enhances the imagination powers of people. Cinema is a way of showing the world from the perspective of the director, thus it inspires other people too to broaden their thinking and imagination.

Most importantly, cinema brings to us different cultures of the world. It introduces us to various art forms and helps us in gaining knowledge about how different people lead their lives.

In a way, it brings us closer and makes us more accepting of different art forms and cultures. Cinema also teaches us a thing or two about practical life. Incidents are shown in movies of emergencies like robbery, fire, kidnapping and more help us learn things which we can apply in real life to save ourselves. Thus, it makes us more aware and teaches us to improvise.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Disadvantages of Cinema

While cinema may be beneficial in many ways, it is also very damaging in various areas. Firstly, it stereotypes a lot of things including gender roles, religious practices, communities and more. This creates a false notion and a negative impact against that certain group of people.

People also consider it to be a waste of time and money as most of the movies nowadays are not showing or teaching anything valuable. It is just trash content with objectification and lies. Moreover, it also makes people addicts because you must have seen movie buffs flocking to the theatre every weekend to just watch the latest movie for the sake of it.

Most importantly, cinema shows pretty violent and sexual content. It contributes to the vulgarity and eve-teasing present in our society today. Thus, it harms the young minds of the world very gravely.

Q.1 How does cinema benefit us?

A.1 Cinema has a positive impact on society as it helps us in connecting to people of other cultures. It reflects the issues of society and makes us familiar with them. Moreover, it also makes us more aware and helps to improvise in emergency situations.

Q.2 What are the disadvantages of cinema?

A.2 Often cinema stereotypes various things and creates false notions of people and communities. It is also considered to be a waste of time and money as some movies are pure trash and don’t teach something valuable. Most importantly, it also demonstrates sexual and violent content which has a bad impact on young minds.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essays About Movies: 7 Examples and 5 Writing Prompts

Check out our guide with essays about movies for budding videographers and artistic students. Learn from our helpful list of examples and prompts.

Watching movies is a part of almost everyone’s life. They entertain us, teach us lessons, and even help us socialize by giving us topics to talk about with others. As long as movies have been produced, everyone has patronized them. Essays about movies are a great way to learn all about the meaning behind the picture.

Cinema is an art form in itself. The lighting, camera work, and acting in the most widely acclaimed movies are worthy of praise. Furthermore, a movie can be used to send a message, often discussing issues in contemporary society. Movies are entertaining, but more importantly, they are works of art. If you’re interested in this topic, check out our round-up of screenwriters on Instagram .

5 Helpful Essay Examples

1. the positive effects of movies on human behaviour by ajay rathod, 2. horror movies by emanuel briggs, 3. casablanca – the greatest hollywood movie ever (author unknown).

- 4. Dune Review: An Old Story Reshaped For The New 2021 Audience by Oren Cohen

5. Blockbuster movies create booms for tourism — and headaches for locals by Shubhangi Goel

- 6. Moonage Daydream: “Who Is He? What Is He?” by Jonathan Romney

- 7. La Bamba: American Dreaming, Chicano Style by Yolanda Machado

1. My Favorite Movie

2. movies genres, 3. special effects in movies, 4. what do you look for in a movie, 5. the evolution of movies.

“Films encourage us to take action. Our favourite characters, superheroes, teach us life lessons. They give us ideas and inspiration to do everything for the better instead of just sitting around, waiting for things to go their way. Films about famous personalities are the perfect way to affect social behaviour positively. Films are a source of knowledge. They can help learn what’s in the trend, find out more about ancient times, or fill out some knowledge gaps.”

In this movie essay, Rathod gives readers three ways watching movies can positively affect us. Movie writers, producers, and directors use their platform to teach viewers life skills, the importance of education, and the contrast between good and evil. Watching movies can also help us improve critical thinking, according to Briggs. Not only do movies entertain us, but they also have many educational benefits. You might also be interested in these essays about consumerism .

“Many people involving children and adults can effect with their sleeping disturbance and anxiety. Myths, non-realistic, fairy tales could respond differently with being in the real world. Horror movies bring a lot of excitement and entertainment among you and your family. Horror movies can cause physical behavior changes in a person by watching the films. The results of watching horror movies shows that is has really effect people whether you’re an adult, teens, and most likely happens during your childhood.”

In his essay, Briggs acknowledges why people enjoy horror movies so much but warns of their adverse effects on viewers. Most commonly, they cause viewers nightmares, which may cause anxiety and sleep disorders. He focuses on the films’ effects on children, whose more sensitive, less developed brains may respond with worse symptoms, including major trauma. The films can affect all people negatively, but children are the most affected.

“This was the message of Casablanca in late 1942. It was the ideal opportunity for America to utilize its muscles and enter the battle. America was to end up the hesitant gatekeeper of the entire world. The characters of Casablanca, similar to the youthful Americans of the 1960s who stick headed the challenge development, are ‘genuine Americans’ lost in a hostile region, battling to open up another reality.”

In this essay, the author discusses the 1942 film Casablanca , which is said to be the greatest movie ever made, and explains why it has gotten this reputation. To an extent, the film’s storyline, acting, and even relatability (it was set during World War II) allowed it to shine from its release until the present. It invokes feelings of bravery, passion, and nostalgia, which is why many love the movie. You can also check out these books about adaption .

4. Dune Review: An Old Story Reshaped For The New 2021 Audience by Oren Cohen

“Lady Jessica is a powerful woman in the original book, yet her interactions with Paul diminish her as he thinks of her as slow of thought. Something we don’t like to see in 2021 — and for a good reason. Every book is a product of its time, and every great storyteller knows how to adapt an old story to a new audience. I believe Villeneuve received a lot of hate from diehard Dune fans for making these changes, but I fully support him.”

Like the previous essay, Cohen reviews a film, in this case, Denis Villeneuve’s Dune , released in 2021. He praises the film, writing about its accurate portrayal of the epic’s vast, dramatic scale, music, and, interestingly, its ability to portray the characters in a way more palatable to contemporary audiences while staying somewhat faithful to the author’s original vision. Cohen enjoyed the movie thoroughly, saying that the movie did the book justice.

“Those travelers added around 630 million New Zealand dollars ($437 million) to the country’s economy in 2019 alone, the tourism authority told CNBC. A survey by the tourism board, however, showed that almost one in five Kiwis are worried that the country attracts too many tourists. Overcrowding at tourist spots, lack of infrastructure, road congestion and environmental damage are creating tension between locals and visitors, according to a 2019 report by Tourism New Zealand.”

The locations where successful movies are filmed often become tourist destinations for fans of those movies. Goel writes about how “film tourism” affects the residents of popular filming locations. The environment is sometimes damaged, and the locals are caught off guard. Though this is not always the case, film tourism is detrimental to the residents and ecosystem of these locations. You can also check out these essays about The Great Gatsby .

6. Moonage Daydream: “Who Is He? What Is He?” by Jonathan Romney

“Right from the start, Brett Morgen’s Moonage Daydream (2022) catches us off guard. It begins with an epigraph musing on Friedrich Nietzsche’s proclamation that “God is dead,” then takes us into deep space and onto the surface of the moon. It then unleashes an image storm of rockets, robots, and star-gazers, and rapid-fire fragments of early silent cinema, 1920s science fiction, fifties cartoons, and sixties and seventies newsreel footage, before lingering on a close-up of glittery varnish on fingernails.”

Moonage Daydream is a feature film containing never-before-seen footage of David Bowie. In this essay, Romney delves into the process behind creating the movie and how the footage was captured. It also looks at the director’s approach to creating a structured and cohesive film, which took over two years to plan. This essay looks at how Bowie’s essence was captured and preserved in this movie while displaying the intricacies of his mind.

7. La Bamba: American Dreaming, Chicano Style by Yolanda Machado

“A traumatic memory, awash in hazy neutral tones, arising as a nightmare. Santo & Johnny’s mournful “Sleep Walk” playing. A sudden death, foreshadowing the passing of a star far too young. The opening sequence of Luis Valdez’s La Bamba (1987) feels like it could be from another film—what follows is largely a celebration of life and music.”

La Bamba is a well-known movie about a teenage Mexican migrant who became a rock ‘n’ roll star. His rise to fame is filled with difficult social dynamics, and the star tragically dies in a plane crash at a young age. In this essay, Machado looks at how the tragic death of the star is presented to the viewer, foreshadowing the passing of the young star before flashing back to the beginning of the star’s career. Machado analyses the storyline and directing style, commenting on the detailed depiction of the young star’s life. It’s an in-depth essay that covers everything from plot to writing style to direction.

5 Prompts for Essays About Movies

Simple and straightforward, write about your favorite movie. Explain its premise, characters, and plot, and elaborate on some of the driving messages and themes behind the film. You should also explain why you enjoy the movie so much: what impact does it have on you? Finally, answer this question in your own words for an engaging piece of writing.

From horror to romance, movies can fall into many categories. Choose one of the main genres in cinema and discuss the characteristics of movies under that category. Explain prevalent themes, symbols, and motifs, and give examples of movies belonging to your chosen genre. For example, horror movies often have underlying themes such as mental health issues, trauma, and relationships falling apart.

Without a doubt, special effects in movies have improved drastically. Both practical and computer-generated effects produce outstanding, detailed effects to depict situations most would consider unfathomable, such as the vast space battles of the Star Wars movies. Write about the development of special effects over the years, citing evidence to support your writing. Be sure to detail key highlights in the history of special effects.

Movies are always made to be appreciated by viewers, but whether or not they enjoy them varies, depending on their preferences. In your essay, write about what you look for in a “good” movie in terms of plot, characters, dialogue, or anything else. You need not go too in-depth but explain your answers adequately. In your opinion, you can use your favorite movie as an example by writing about the key characteristics that make it a great movie.

From the silent black-and-white movies of the early 1900s to the vivid, high-definition movies of today, times have changed concerning movies. Write about how the film industry has improved over time. If this topic seems too broad, feel free to focus on one aspect, such as cinematography, themes, or acting.

For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers .

If you’re looking for more ideas, check out our essays about music topic guide !

Meet Rachael, the editor at Become a Writer Today. With years of experience in the field, she is passionate about language and dedicated to producing high-quality content that engages and informs readers. When she's not editing or writing, you can find her exploring the great outdoors, finding inspiration for her next project.

View all posts

MovieScope Magazine

- Advertise with movieScope

- Announcement

- Ask The Agent

- Distribution

- Industry Insider

- Location Focus

- Script Talk

- Cinematography

- DVD/ Blu-Ray

The Psychology of Film: How Movies Affect Our Emotions and Perceptions

Cinema, with its mesmerizing visuals and compelling narratives, has the power to transcend mere entertainment and delve into the intricate realm of human psychology. The way we respond to films, both emotionally and cognitively, offers a fascinating exploration into the psychology of film—how movies become more than just a sequence of scenes but a journey that profoundly influences our emotions and perceptions.

Emotional Impact of Movies: Stirring the Soul One of the most potent aspects of film psychology lies in the emotional impact movies have on viewers. Whether it’s the heart-wrenching drama that brings tears to our eyes or the exhilarating adventure that quickens our pulse, films have an unparalleled ability to stir a wide spectrum of emotions. This emotional resonance is a testament to the storytelling prowess of filmmakers and their capacity to create empathetic connections with the audience.

Cinematic Influence on Perception: Shaping Perspectives Movies don’t merely evoke emotions; they also shape our perceptions of the world. From cultural insights to societal norms, films act as a lens through which we view and interpret reality. The cinematic influence on perception extends beyond mere entertainment, contributing to the formation of beliefs, attitudes, and even the way we understand complex social issues.

Psychology of Storytelling: Tapping into Universal Narratives At the heart of film psychology is the psychology of storytelling. Narratives in films tap into universal themes and archetypes that resonate with the collective human experience. Whether it’s the hero’s journey or the exploration of love and loss, these storytelling elements engage our minds on a deep psychological level, triggering emotional responses that connect us to the shared narratives of humanity.

Film and Mood Regulation: Escapism and Catharsis Movies serve as a powerful tool for mood regulation. The act of watching a film allows viewers to escape from the demands of daily life, immersing themselves in alternate realities. From the cathartic release of tension in a comedy to the introspective contemplation induced by a thought-provoking drama, films provide a unique avenue for regulating and expressing emotions.

Cognitive Responses to Films: Engaging the Mind The psychological impact of films extends beyond emotions to cognitive responses. The visual and auditory stimulation in movies engages various cognitive processes, including attention, memory, and problem-solving. The intricate narratives and complex characters challenge the mind, fostering intellectual engagement that goes beyond passive observation.

Psychological Effects of Movie Genres: Crafting Experiences Different movie genres elicit distinct psychological effects. Horror films tap into our primal fears, triggering adrenaline and the fight-or-flight response. Romantic movies evoke feelings of love and connection, while action films elicit excitement and suspense. The choice of genre becomes a deliberate tool for filmmakers to craft specific psychological experiences for their audience.

Cinematic Empathy: Understanding Through Film Characters Cinematic empathy, the ability to understand and share the feelings of film characters, is a central aspect of film psychology. Viewers form emotional connections with characters, experiencing their joys and sorrows. This empathetic engagement not only enhances the viewing experience but also contributes to the development of emotional intelligence and empathy in real-life relationships.

Film and Memory Formation: The Art of Retention Movies have a unique capacity to enhance memory formation. The combination of visuals, dialogue, and music creates a multisensory experience that aids in the retention of information. Iconic scenes, memorable quotes, and the emotional impact of films become etched into our memories, shaping our cultural references and personal recollections.

Viewer Perception in Cinema: Active Participation In the psychology of film, viewers are not passive recipients but active participants in the cinematic experience. The choices made by directors, the visual aesthetics, and the narrative structures invite viewers to interpret and engage with the content actively. This participatory nature deepens the psychological connection between the audience and the film.

In conclusion, the psychology of film is a captivating exploration into the intricate ways movies influence our emotions, perceptions, and cognitive responses. From the emotional resonance of storytelling to the shaping of cultural perspectives, cinema is a potent force that goes beyond entertainment, leaving an indelible mark on the psyche of those who embark on its cinematic journeys. As we continue to be enthralled by the magic of the silver screen, the psychology of film remains a dynamic and evolving field, offering endless possibilities for understanding the complex interplay between storytelling, emotions, and the human mind.

View all posts

LEAVE A RESPONSE Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You Might Also Like

The Inbetweeners Movie 2 To Start Shooting 7 December – movieScope

– . – Frozen

– . – location focus, – . – ashley jones (producer).

Latest News

Homemade Treats: Elevating Comfort Food with Personal Touch

Aneka Seafood: Sebuah Pangilan untuk Memuaskan Selera

Tuna Eyeballs: A Culinary Adventure in Japanese Cuisine 2024

Burger Raja: Perpaduan Unik Cita Rasa Keraton Yogyakarta dalam Dunia Fast Food

Kawaii Plushies: Bringing Joy and Comfort into Your Home

Inovasi Paratha: Kreasi Chef pada Hidangan Klasik di Restoran

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 July 2018

A psychology of the film

- Ed S. Tan 1 , 2

Palgrave Communications volume 4 , Article number: 82 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

167k Accesses

28 Citations

67 Altmetric

Metrics details

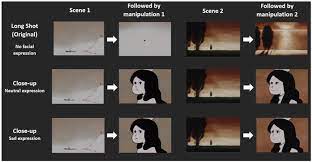

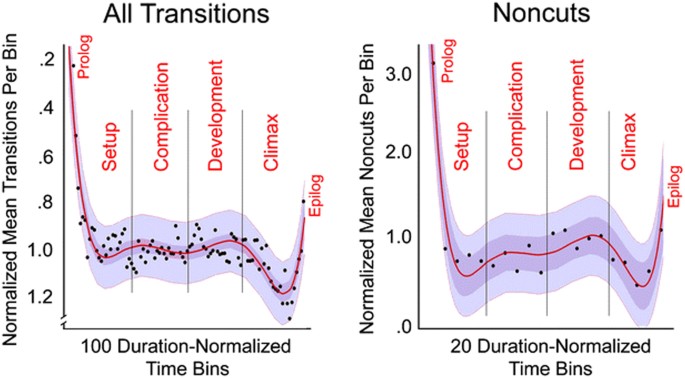

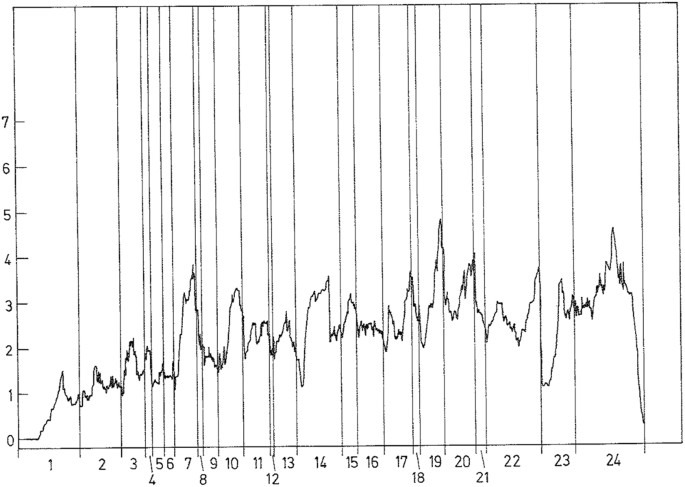

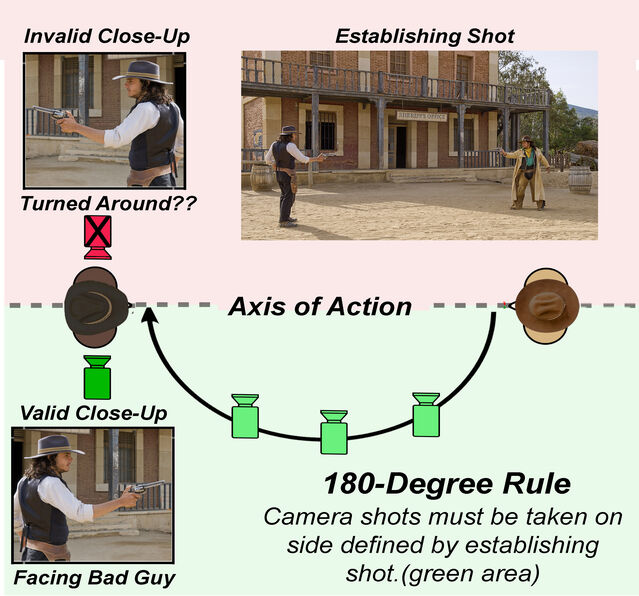

- Cultural and media studies

The cinema as a cultural institution has been studied by academic researchers in the arts and humanities. At present, cultural media studies are the home to the aesthetics and critical analysis of film, film history and other branches of film scholarship. Probably less known to most is that research psychologists working in social and life science labs have also contributed to the study of the medium. They have examined the particular experience that motion pictures provide to the film audience and the mechanisms that explain the perception and comprehension of film, and how movies move viewers and to what effects. This article reviews achievements in psychological research of the film since its earliest beginnings in the 1910s. A leading issue in the research has been whether understanding films is a bottom-up process, or a top-down one. A bottom-up explanation likens film-viewing to highly automated detection of stimulus features physically given in the supply of images; a top-down one to the construction of scenes from very incomplete information using mental schemata. Early film psychologists tried to pinpoint critical features of simple visual stimuli responsible for the perception of smooth movement. The riddle of apparent motion has not yet been solved up to now. Gestalt psychologists were the first to point at the role of mental structures in seeing smooth movement, using simple visual forms and displays. Bottom-up and top-down approaches to the comprehension of film fought for priority from the 60s onwards and became integrated at the end of the century. Gibson’s concept of direct perception led to the identification of low-level film-stylistic cues that are used in mainstream film production, and support film viewers in highly automated seamless perception of film scenes. Hochberg’s argument for the indispensability of mental schemata, too, accounted for the smooth cognitive construction of portrayed action and scenes. Since the 90s, cognitive analyses of narration in film by film scholars from the humanities have revolutionised accounts of the comprehension of movies. They informed computational content analyses that link low-level film features with meaningful units of film-story-telling. After a century of research, some perceptual and cognitive mechanisms that support our interaction with events in the real world have been uncovered. Today, the film experience at large has reappeared on the agenda. An integration of top-down and bottom-up mechanisms is sought in explaining the remarkable intensity of the film experience. Advances are now being made in grasping what it is like to enjoy movies, by describing the absorbing and moving qualities of the experience. As an example, a current account of film viewers' emotional experience is presented. Further advances in our understanding of the film experience and its underlying mechanisms can be expected if film psychologists team up with cognitive film studies, computer vision and the neurosciences. This collaboration is also expected to allow for research into mainstream and other genres as forms of art.

Similar content being viewed by others

Art films foster theory of mind

Movie editing influences spectators’ time perception

Cortical network responses map onto data-driven features that capture visual semantics of movie fragments

An agenda for the psychology of the film.

At the time of the first kinetoscope and cinema exhibitions in 1894–1895, thanks to devices such as the Phenakistoscope, Zoetrope and Praxinoscope, moving images had been popular for decades. Just before that time, academic psychology turned to the identification of the mechanisms underlying the functioning of the mind. Perception psychologists began to study apparent movement of experimental visual stimuli under controlled conditions because they found moving stimuli interesting cases in human perception, or as part of the study of psychological aesthetics founded by Gustav Fechner and Wilhelm Wundt. The publication of The Photoplay: A Psychological Study marked the beginning of the psychology of the film. Hugo Münsterberg was trained by Wundt and recruited by William James to lead the experimental psychology lab at Harvard. Importantly, Münsterberg was also an avid cinemagoer as his analyses of theatrical films of his time may tell, and a professing cinephile at that. Münsterberg set two tasks for the study of the film: one was to describe the functioning of psychological mechanisms in the reception of film; the other to give an account of film as an artistic medium.

Münsterberg shared his contemporaries’ and even today’s spectators’ fascination for the wonder of moving images and their apparent reality. He described the film experience as a 'unique inner experience' that due to the simultaneous character of reality and pictorial representation “brings our mind into a peculiar complex state” (p. 24).

In the first part of The Photoplay , explores how film characteristically addresses the mechanisms of the basic psychological functions investigated by experimental psychology—namely perception, attention, memory and emotion. Footnote 1 In The Photoplay the imagination is the psychological faculty that theatrical movies ultimately play upon; attention, perception, memory and emotion are also directed by the film, but contribute to the film experience as building blocks for the imagination in the first place. One of the ways that films entertain the imagination is by mimicking the psychological functions. Film scenes may represent as-if perceptions, as-if thoughts, as-if streams of associations, and as-if emotions or more generally: display subjectivity. Footnote 2 Second, the film creates an imagined world that deviates from real world scenes as we perceive these in real life. Liberated from real life perceptual constraints involves the spectator’s self in 'shaping reality by the demands of our soul' (p. 41). Third, Münsterberg has a nuanced view of the automaticity of responses to film. On the one hand, it is the spectator’s choice—based on their interest—which ideas from memory and the imagination to fit to images presented on screen; they are felt as 'our subjective supplements' (p. 46). On the other, the film’s suggestions function to control associated ideas, '… not felt as our creation but as something to which we have to submit' (p. 46). And yet in Münsterberg’s view the film does not dictate psychological responses in any way. Footnote 3

Finally, The Photoplay provides abundant and compelling introspective reports of the film experience and so probes into the phenomenology of film, that is, what it is like to watch a movie. I think it is fair to say that for Münsterberg the film experience is the ultimate explanandum for a psychology of the film. In order to account for that phenomenology by mechanism of the mind proper descriptions of the film experience are needed, and introspective reports are an indispensable starting point for these.

The other task Münsterberg set himself was to propose an account of the film as a form of art. Part two of The Photoplay proposes that the film experience includes an awareness of unreality of perceived scenes. This awareness is taken as fundamental for psychological aesthetics; all forms of art are perceived to go beyond the mere imitation of nature. Footnote 4 Münsterberg showed himself a formalist in that he theorised that aesthetic satisfaction depends not on recognition of similarity with the real world or practical needs, but on the sense of an 'inner agreement and harmony [of the film’s parts]' (p. 73). Footnote 5 But in order to qualify as art, according to Münsterberg film was not to deviate too much from realistic representation that distinguishes theatrical movies from non-mainstream forms.

Münsterberg’s agenda is in retrospect quite complete. The detailed investigation of psychological mechanisms and aesthetics of film is followed by a last chapter on the social functions of the photoplay. The thoughts forwarded in it are more global than those on perception and aesthetics. The immediate effect of theatrical films on their audience is enjoyment due to their freeing the imagination, and their easy accessibility to consciousness 'which no other art can furnish us' (p. 95). Enjoyment comes with additional gratifications such as a feeling of vitality, experiencing emotions, learning and above all aesthetic emotion.

In a final section behavioral effects of successful films are discussed. Here the film psychologist vents concerns on what we now refer to as undesirable attitude changes and social learning, especially in young audiences. The agenda of today's social science research on mass media effects (e.g. Dill, 2013 ) is not all that different from Münsterberg's in the last chapter of The Photoplay.

The two tasks that Münsterberg worked on set the agenda for the psychology of film in the century after The Photoplay . It is clearly recognisable in the psychology of the film as we know it today. Footnote 6 But the promising debut made in 1916 was not followed up until the nineteen seventies, or so it seems. James Gibson lamented in his last book on visual perception that whereas the technology of the cinema had reached peak levels of applied science, its psychology had so far not developed at all (1979, p. 292). The cognitive revolution in psychology of the 60s paved the way for its upsurge in the early 80s. But some qualifications need to be made on the seeming moratorium. First, Rudolf Arnheim developed since the 1920s a psychology of artistic film form. Second, although not visible as a coherent psychology of the film, laboratory research on issues in visual perception of the moving image—in particular studies of apparent movement—continued.

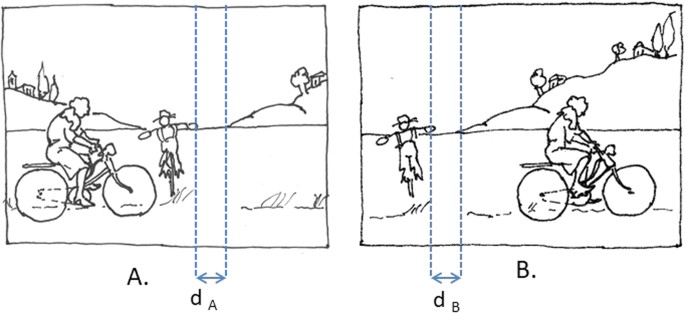

Gestalt psychology and film form

Rudolf Arnheim’s essays published first in 1932 added analytic force to Münsterberg’s conviction that film is not an imitation of life. Film and Reality ( 1957 ) highlights shortcomings of film in representing scenes as we know them from natural perception. Footnote 7 In the same essay, it is pointed out that comparing a filmic representation of a scene with its natural perception is what analytic philosophers would call an error of category. In The Making of Film ( 1957 ) Arnheim presented an inventory of formative means for artistic manipulations of visual scenes, including delimitation and point of view, distance to objects and mobility of framing. It is argued that chosen manipulations often go against the most realistic options. For example, ideal viewpoints and canonical distances are often dismissed in favour of more revealing options. Footnote 8 Arnheim’s aesthetics of film gravitates towards acknowledged artistic productions more than to the 'naturalistic narrative film' (e.g., 1957 , p. 116–117) the more moderate art form that Münsterberg tended to prefer.

Arnheim was informed by such founders of Gestalt psychology as Wertheimer, Köhler and Koffka. This school held that natural perception results from the mind’s activity. It organises sensory inputs into patterns according to formal principles such as simplicity, regularity, order and symmetry. Arnheim developed into the leading Gestalt theorist of aesthetics of the 20th century. In his 1974 book he analysed a great number of pictorial, sculptural, architectural, musical and poetic works of art while only rarely referring to film. Footnote 9 The cornerstone aesthetic property of art works including film is expression, defined by Arnheim as 'modes of organic or inorganic behaviour displayed in the dynamic appearance of perceptual objects or events' ( 1974 , p. 445). Expression’s dynamic appearance is a structural creation of the mind imposing itself on sound, touch, muscular sensations and vision. Expressive qualities are in turn, the building blocks of symbolic meaning that art works including film add to the representation of objects and events as we know them in the outer world. Thus, Arnheim’s theory of expression and meaning in the arts seems to echo Münsterberg’s formalist position on the perception of 'inner harmony' as the determinant of film spectators’ aesthetic satisfaction.

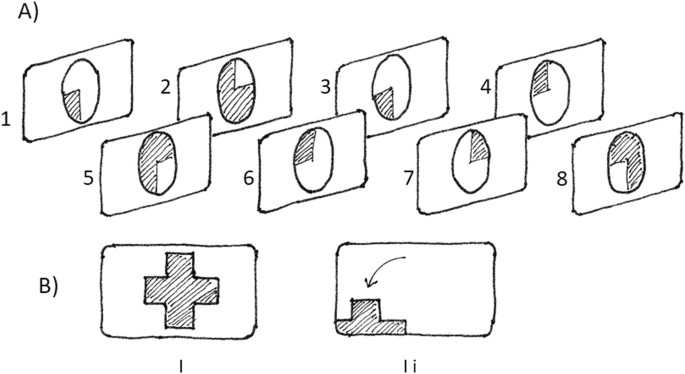

Apparent motion

Münsterberg shared the amazement that moving images awakened in early film audiences. He considered the experience of movement a central issue for the psychology of the film. The experience of movement in response to a series of changing still pictures has been studied in psychology and physiology under the rubric of apparent motion . Footnote 10 In Münsterberg’s days, international psychology labs were probing the perception of movement in response to experimental stimuli that were perceived as moving images. Well-known examples include apparent motion induced by the subsequent views of single stationary lines in different positions that result in phi movement , the perception of one moving shape or line. Researchers in this area have continued to study the perception of movement in film as only one of many interesting visual stimuli, such as shapes painted on rotating disks, or dynamic computer-generated lights, shapes and objects of many kinds. Why and how we see motion has been as basic to the study of visual perception as questions of perception of colour, depth, and shape. Helmholtz proposed that what we need to explain is how retinal images that correspond one-to one, i.e., optically with a scene in the world are transformed into mental images, or percepts that we experience. In the case of apparent motion, we also need to understand how a succession of retinal images are perceived as one or more objects in motion Footnote 11 Apparent motion in film viewing needs to be smooth, Footnote 12 and depends on frame rates and masking effects. (The latter effects refer to dampening of the visual impact of one frame by a subsequently presented black frame).

Münsterberg’s conviction that the perception of movement needs a cognitive contribution from the viewer clashes with alternative explanations that rely on prewired visual mechanisms that automatically and immediately pick up the right stimulus features causing an immediate perception of motion, without the mind adding anything substantial. The inventors of nineteenth century moving image devices explained the illusion of movement by the slowness of the eye, possibly following P.M. Roget’s report on apparent motion to the Royal Society in 1824. In the early years of cinema, the persistence of vision account was meant to add precision to this explanation. It proposed that the retina, the optic nerve or the brain could not keep up with a rapid succession of projected frames, and that afterimages would bridge the intervals between subsequent frames. Anderson and Fisher ( 1978 ) and Anderson and Anderson ( 1993 ) have argued why the notion is false and misleading. It suggests that film viewers’ perceptual system sluggishly pile up retina images on top of one another. However, this would lead them to blur which obviously is not the case. The Andersons refer to the explanation as a myth because it is based on a mistaken conception of film viewing as a passive process. Even with the characteristically very small changes between subsequent frames characteristic of motion picture projection, the visual system performs an active integrative role in distinguishing what has changed from one image to another. This integrating mechanism in film viewing is exactly the same as in perceiving motion in real world scenes. Mechanistic explanations have since been founded on growing insights in the neuroscience of vision, such as single cell activity recordings in response to precisely localised stimulus features. Footnote 13 'Preprocessing' of visual input before it arrives in the cortex takes place in the retina and the lateral geniculate nucleus, which have specialised cells or trajectories for apprehending various aspects of motion. There are major interactions between perceptual modules. Footnote 14 Physiological and anatomical findings in the primate visual system, as well as clinical evidence, support the distinction of separate channels for the perception of movement on the one hand, and form, colour and depth on the other (Livingstone and Hubel, 1987 ). Research on how exactly the cortical integration systems for vision are organised has not yet come to a close. A variety of anatomical subsystems have been identified Footnote 15 , and there is room for task variables in the explanation of motion perception. Footnote 16 The operation of task variables in presumably automated processes (e.g., attentional set, induced by specific task instructions) complicates accounts of apparent motion and the perception of movement based on lowest processing levels.

Non-trivial and clear-cut contributions of the mind to smooth apparent motion have been proposed by Gestalt psychologists. Arnheim ( 1974 ) considered the perception of movement as subsidiary to that of change. The mind uses Gestalt principles such as good continuation and object consistency to perceive patterns in ongoing stimuli. Movement is the perception of developing sequences and events. Footnote 17 Gestalt psychologists have attempted to identify stimulus features that are perceived as a spatiotemporal pattern of 'good' motion, and they discovered various types of apparent motion have been distinguished as a function of stimulus features. In an overview volume, Kolers ( 1972 ) presented phi and beta motion as the major variants. Phi , the most famous, was first documented by Wertheimer in 1912 . An image of an object is presented twice in succession in different positions. Footnote 18 Pure or beta motion that is objectless motion, was the novel and amazing observation; the perception seemed to be a sum or integration by the mind beyond the stimulus parts, and asked for an explanation. It is also experienced when the objects in the subsequent presentations are different.

Wertheimer and those after him looked for mechanisms of the mind that could complement the features of the stimulus responsible for apparent motion in its various forms. Footnote 19 Other studies of apparent motion, too, indicated that simple models of stimulus features alone could not explain apparent motion. Footnote 20 One of the best examples of what the cognitive system adds to stimulus features is induced motion (Duncker, 1929 ). When we see a small target being displaced relative to a framework surrounding it, we invariably see the target moving irrespective of whether it is the target or the frame that is displaced. Ubiquitous film examples are shots of moving vehicles, with mobile or static framing.

In this summary and incomplete overview of the field, we could not make a strict distinction between mechanist and cognitive explanations for the perception of movement in film. The current state of research does not allow for it. Footnote 21 Kolers’s conclusions on the state of the field closing his 1972 volume on motion perception seem still valid. He inferred from then extant research that there must be separate mechanisms for extracting information from the visual stimulus and for selecting and supplementing the information into a visual experience of smooth object motion or motion brief. He concluded that 'The impletions of apparent motion make it clear that although the visual apparatus may select from an array [of] features to which it responds, the features themselves do not create the visual experience. Rather, that experience is generated from within, by means of supplementative mechanisms whose rules are accomodative and rationalizing rather than analytical' (p.198). But even if after Koler's analysis some perceptual (Cutting, 1986) or brain mechanisms (Zacks, 2015) have been identified today we still do not know enough about the self-supplied supplementations. Footnote 22

Perception and cognition of scenes

Mental representation and event comprehension.

Contributions of the mind can go considerably beyond apparent motion, i.e., the perception of smooth motion from one frame to another. The cognitive revolution in academic psychology that took off in the 1960s broadened the conceptualisation of contributions of the mind to the film experience beyond the narrower stimulus-response paradigms that had dominated psychological science until the 1960s. The cognitive revolution went beyond Gestalt notions of patterns applied by the mind on stimulus information. It introduced the concept of mental representation as a key to understanding the relation between sensory impressions from the environment on the one hand, and people’s responses to it. Moreover, these cognitive structures were seen functional in mental operations such as retrieval and accommodation of schemas from memory, inference and attribution. These were quite complex in comparison to perceptual and psychophysical responses. In the past 30 years, they have come to encompass event, action, person, cultural, narrative and formal-stylistic schemas. The cognitive turn in film psychology has stimulated a growing exchange with humanist film scholarship, resulting in advances in the elaboration of cognitive structural notions. Early applications of the cognitive perspective in the psychology of the film can be found in the 1940s and 50s in work by Albert Michotte ( 1946 ) and Heider and Simmel. Footnote 23

Against mental representation: direct perception of film events