Healthy Eating Learning Opportunities and Nutrition Education

Healthy eating learning opportunities includes nutrition education and other activities integrated into the school day that can give children knowledge and skills to help choose and consume healthy foods and beverages. 1 Nutrition education is a vital part of a comprehensive health education program and empowers children with knowledge and skills to make healthy food and beverage choices. 2-8

US students receive less than 8 hours of required nutrition education each school year, 9 far below the 40 to 50 hours that are needed to affect behavior change. 10,11 Additionally, the percentage of schools providing required instruction on nutrition and dietary behaviors decreased from 84.6% to 74.1% between 2000 and 2014. 9

Given the important role that diet plays in preventing chronic diseases and supporting good health, schools would ideally provide students with more hours of nutrition education instruction and engage teachers and parents in nutrition education activities. 5, 12 Research shows that nutrition education can teach students to recognize how healthy diet influences emotional well-being and how emotions may influence eating habits. However, because schools face many demands, school staff can consider ways to add nutrition education into the existing schedule. 11

Nutrition education can be incorporated throughout the school day and in various locations within a school. This provides flexibility allowing schools to use strategies that work with their settings, daily schedule, and resources.

In the Classroom

Nutrition education can take place in the classroom, either through a stand-alone health education class or combined into other subjects including 2,5 :

- Counting with pictures of fruits and vegetables.

- Learning fractions by measuring ingredients for a recipe.

- Examining how plants grow.

- Learning about cultural food traditions.

Nutrition education should align with the National Health Education Standards and incorporate the characteristics of an effective health education curriculum .

Farm to School

Farm-to-school programs vary in each school or district, but often include one or more of the following strategies:

- Purchasing and serving local or regionally produced foods in the school meal programs.

- Educating students about agriculture, food, health, and nutrition.

- Engaging students in hands-on learning opportunities through gardening, cooking lessons, or farm field trips.

Students who participate in farm-to-school activities have increased knowledge about nutrition and agriculture, are more willing to try new foods, and consume more fruits and vegetables. 14-17

School Gardens

School garden programs can increase students’ nutrition knowledge, willingness to try fruit and vegetables, and positive attitudes about fruits and vegetables. 18-22 School gardens vary in size and purpose. Schools may have window sill gardens, raised beds, greenhouses, or planted fields.

Students can prepare the soil for the garden, plant seeds, harvest the fruits and vegetables, and taste the food from the garden. Produce from school gardens can be incorporated into school meals or taste tests. Classroom teachers can teach lessons in math, science, history, and language arts using the school garden.

In the Cafeteria

Cafeterias are learning labs where students are exposed to new foods through the school meal program, see what balanced meals look like, and may be encouraged to try new foods through verbal prompts from school nutrition staff, 23 or taste tests. 24-25 Cafeterias may also be decorated with nutrition promotion posters or student artwork promoting healthy eating. 24

Other Opportunities

Schools can add messages about nutrition and healthy eating into the following:

- Morning announcements.

- School assemblies.

- Materials sent home to parents and guardians. 24

- Staff meetings.

- Parent-teacher group meetings.

These strategies can help reinforce messages about good nutrition and help ensure that students see and hear consistent information about healthy eating across the school campus and at home. 2

Shared use agreements can extend healthy eating learning opportunities. As an example, an after-school STEM club could gain access to school gardens as learning labs.

CDC Parents for Healthy Schools: Ideas for Parents

Nutrition: Gardening Interventions | The Community Guide

Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025

Introduction to School Gardens

Learning Through the Garden

National Farm-to-School Network

National Farm to School Network Resource Database

National Health Education Standards

Team Nutrition Curricula

USDA Farm to School

USDA Team Nutrition

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2011;60(RR-5):1–76.

- Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards. National Health Education Standards: Achieving Excellence. 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool, 2012, Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/hecat/index.htm. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Price C, Cohen D, Pribis P, Cerami J. Nutrition education and body mass index in grades K–12: a systematic review. J Sch Health. 2017;87:715–720.

- Meiklejohn S, Ryan L, Palermo C. A systematic review of the impact of multi-strategy nutrition education programs on health and nutrition of adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav . 2016;48:631–646.

- Silveira JA, Taddei JA, Guerra PH, Nobre MR. The effect of participation in school-based nutrition education interventions on body mass index: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled community trials. Prev Med . 2013;56:237–243.

- County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. School-based Nutrition Education Programs website. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/take-action-to-improve-health/what-works-for-health/policies/school-based-nutrition-education-programs . Accessed on April 9, 2019.

- Results from the School Health Policies and Practices Study 2014 . Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

- Connell DB, Turner RR, Mason EF. Results of the school health education evaluation: health promotion effectiveness, implementation, and costs . J Sch Health . 1985;55(8):316–321.

- Institute of Medicine. Nutrition Education in the K–12 Curriculum: The Role of National Standards: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014.

- Murimi MW, Moyeda-Carabaza AF, Nguyen B, Saha S, Amin R, Njike V. Factors that contribute to effective nutrition education interventions in children: a systematic review. Nutr Rev . 2018;76(8):553–580.

- Hayes D, Contento IR, Weekly C. Position of the American Dietetic Association, School Nutrition Association, and Society for Nutrition Education: comprehensive school nutrition services. J Acad Nutr Diet . 2018; 118:913–919.

- Joshi A, Misako Azuma A, Feenstra G. Do farm-to-school programs make a difference? Findings and future research needs . J Hunger Environ Nutr . 2008;3:229–246.

- Moss A, Smith S, Null D, Long Roth S, Tragoudas U. Farm to school and nutrition education: Positively affecting elementary school-aged children’s nutrition knowledge and consumption behavior. Child Obes . 2013;9(1):51–6.

- Bontrager Yoder AB, Liebhart JL, McCarty DJ, Meinen A, Schoeller D, Vargas C, LaRowe T. Farm to elementary school programming increases access to fruits and vegetables and increases their consumption among those with low intake . J Nutr Educ Behav . 2014;46(5):341–9.

- The National Farm to School Network. The Benefits of Farm to School website. http://www.farmtoschool.org/Resources/BenefitsFactSheet.pdf . Accessed on June 14, 2019.

- Berezowitz CK, Bontrager Yoder AB, Schoeller DA. School gardens enhance academic performance and dietary outcomes in children. J Sch Health . 2015;85:508–518.

- Davis JN, Spaniol MR, Somerset S. Sustenance and sustainability: maximizing the impact of school gardens on health outcomes. Public Health Nutr . 2014;18(13):2358–2367.

- Langellotto GA, Gupta A. Gardening increases vegetable consumption in school-aged children: A meta-analytical synthesis. Horttechnology . 2012;22(4):430–445.

- Community Preventative Services Task Force. Nutrition: Gardening Interventions to Increase Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among Children. Finding and Rationale Statement .. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Nutrition-Gardening-Fruit-Vegetable-Consumption-Children-508.pdf . Accessed on May 16, 2019.

- Savoie-Roskos MR, Wengreen H, Durward C. Increasing Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Children and Youth through Gardening-Based Interventions: A Systematic Review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2017;11(2):240–50.

- Schwartz M. The influence of a verbal prompt on school lunch fruit consumption: a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:6.

- Fulkerson JA, French SA, Story M, Nelson H, Hannan PJ. Promotions to increase lower-fat food choices among students in secondary schools: description and outcomes of TACOS (Trying Alternative Cafeteria Options in Schools). Public Health Nutr. 2003 ;7(5):665–674.

- Action for Healthy Kids. Tips for Hosting a Successful Taste Test website. http://www.actionforhealthykids.org/tools-for-schools/find-challenges/classroom-challenges/701-tips-for-hosting-a-successful-taste-test . Accessed on May 19, 2019.

Healthy Youth

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Nutrition and healthy eating

- Nutrition basics

- Healthy diets

- Healthy cooking

- Healthy menus and shopping strategies

- Nutritional supplements

Do you feel like you can't keep up with the latest nutrition news because it's always changing? It's true that knowledge about nutrition and diet evolves over time. But there are some nutrition basics that can help you sort through the latest research and advice.

Nutrition basics come down to eating wholesome foods that support your health.

Want to go beyond the basics? Talk to a healthcare professional, such as a dietitian. You can ask for diet advice that takes into account your health, lifestyle and food preferences.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov. Accessed June 13, 2023.

- Zeratsky KA (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. June 21, 2023.

- Hensrud DD, ed. Add 5 habits. In: The Mayo Clinic Diet. 3rd ed. Mayo Clinic Press; 2023.

- Dietary supplements: What you need to know. Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/WYNTK-Consumer/ Accessed June 13, 2023.

- Vitamins, minerals and supplements: Do you need to take them? Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. https://www.eatright.org/health/essential-nutrients/supplements/vitamins-minerals-and-supplements-do-you-need-to-take-them. Accessed June 22, 2023.

Products and Services

- Available Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Cook Smart, Eat Well

- Nutritional Supplements at Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diet Bundle

- The Mayo Clinic Diet Online

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on High Blood Pressure

- A Book: Live Younger Longer

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

- Health foods

- Antioxidants

- Alcohol use

- Alkaline water

- Artificial sweeteners and other sugar substitutes

- Autism spectrum disorder and digestive symptoms

- Breastfeeding nutrition: Tips for moms

- Butter vs. margarine

- Caffeine content

- Caffeine: How much is too much?

- Is caffeine dehydrating?

- Timing calcium supplements

- Calorie calculator

- COVID-19 and vitamin D

- Can vitamins help prevent a heart attack?

- Can whole-grain foods lower blood pressure?

- Can zinc supplements help treat hidradenitis suppurativa?

- Carbohydrates

- Chart of high-fiber foods

- Cholesterol: Top foods to improve your numbers

- Clear liquid diet

- Coconut water: Is it super hydrating?

- Coffee and health

- Cuts of beef

- DASH diet: Recommended servings

- Sample DASH menus

- Diet soda: How much is too much?

- Dietary fats

- Dietary fiber

- Diverticulitis attack triggers

- Diverticulitis diet

- Vitamin C and mood

- Prickly pear cactus

- Does soy really affect breast cancer risk?

- Don't get tricked by these 3 heart-health myths

- Eggs and cholesterol

- Enlarged prostate: Does diet play a role?

- Fasting diet: Can it improve my heart health?

- Fiber supplements

- Ground flaxseed

- Food safety

- Foodborne illness

- Gluten sensitivity and psoriasis: What's the connection?

- Gluten-free diet

- Gout diet: What's allowed, what's not

- Grass-fed beef

- Guide to herbs and spices

- Healthy meals start with planning

- Heartburn medicines and B-12 deficiency

- High-protein diets

- How to track saturated fat

- Intermittent fasting

- Is there a special diet for Crohn's disease?

- Low-fiber diet

- Low-glycemic index diet

- Meatless meals

- Mediterranean diet

- Menus for heart-healthy eating

- Moldy cheese

- Monosodium glutamate (MSG)

- Multivitamins for kids

- Nuts and your heart: Eating nuts for heart health

- Omega-3 in fish

- Omega-6 fatty acids

- Organic foods

- Phenylalanine

- Picnic Problems: High Sodium

- Portion control

- Prenatal vitamins

- Probiotics and prebiotics

- Safely reheat leftovers

- Sea salt vs. table salt

- Taurine in energy drinks

- Nutrition and pain

- Vitamin C megadoses

- Underweight: Add pounds healthfully

- Vegetarian diet

- Vitamin D and MS: Any connection?

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Can a lack of vitamin D cause high blood pressure?

- Vitamin D for babies

- Vitamin D toxicity

- Vitamins for MS: Do supplements make a difference?

- Water after meals

- Daily water requirement

- What is BPA?

- Whole grains

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Healthy Food Choices in Schools

3 Ways Nutrition Influences Student Learning Potential and School Performance

Advocates of child health have experimented with students’ diets in the United States for more than twenty years. Initial studies focused on benefits of improving the health of students are apparent. Likewise, improved nutrition has the potential to positively influence students’ academic performance and behavior.

Though researchers are still working to definitively prove the link, existing data suggests that with better nutrition students are better able to learn, students have fewer absences, and students’ behavior improves, causing fewer disruptions in the classroom. [1]

Improve Nutrition to Increase Brain Function

Several studies show that nutritional status can directly affect mental capacity among school-aged children. For example, iron deficiency, even in early stages, can decrease dopamine transmission, thus negatively impacting cognition. [2] Deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals, specifically thiamine, vitamin E, vitamin B, iodine, and zinc, are shown to inhibit cognitive abilities and mental concentration. [3] Additionally, amino acid and carbohydrate supplementation can improve perception, intuition, and reasoning. [4] There are also a number of studies showing that improvements in nutrient intake can influence the cognitive ability and intelligence levels of school-aged children. [5]

Provide a Balanced Diet for Better Behaviors and Learning Environments

Good Nutrition helps students show up at school prepared to learn. Because improvements in nutrition make students healthier, students are likely to have fewer absences and attend class more frequently. Studies show that malnutrition leads to behavior problems [6] , and that sugar has a negative impact on child behavior. [7] However, these effects can be counteracted when children consume a balanced diet that includes protein, fat, complex carbohydrates, and fiber. Thus students will have more time in class, and students will have fewer interruptions in learning over the course of the school year. Additionally, students’ behavior may improve and cause fewer disruptions in the classroom, creating a better learning environment for each student in the class.

Promote Diet Quality for Positive School Outcomes

Sociologists and economists have looked more closely at the impact of a student’s diet and nutrition on academic and behavioral outcomes. Researchers generally find that a higher quality diet is associated with better performance on exams, [8] and that programs focused on increasing students’ health also show modest improvements in students’ academic test scores. [9] Other studies find that improving the quality of students’ diets leads to students being on task more often, increases math test scores, possibly increases reading test scores, and increases attendance. [10] Additionally, eliminating the sale of soft drinks in vending machines in schools and replacing them with other drinks had a positive effect on behavioral outcomes such as tardiness and disciplinary referrals. [11]

Every student has the potential to do well in school. Failing to provide good nutrition puts them at risk for missing out on meeting that potential. However, taking action today to provide healthier choices in schools can help to set students up for a successful future full of possibilities.

Contributor

David Just Phd- Cornell Center for Behavioral Economics in Child Nutrition Programs

[1] Sorhaindo, A., & Feinstein, L. (2006). What is the relationship between child nutrition and school outcomes. Wider Benefits of Learning Research Report No.18. Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning

[2] Pollitt E. (1993). Iron deficiency and cognitive function. Annual Review of Nutrition, 13, 521–537.

[3] Chenoweth, W. (2007). Vitamin B complex deficiency and excess. In R. Kliegman, H. Jenson, R. Behrman, & B. Stanton (Eds.), Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18 th edition . Philadelphia: Saunders.

Greenbaum, L. (2007a). Vitamin E deficiency. In R. Kliegman, H. Jenson, R. Behrman, & B. Stanton (Eds.), Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18 th Edition . Philadelphia: Saunders.

Greenbaum, L. (2007b). Micronutrient mineral deficiencies. In R. Kliegman, H. Jenson, R. Behrman, & B. Stanton (Eds.), Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18 th Edition . Philadelphia: Saunders.

Bryan, J., Osendarp, S., Hughes, D., Calvaresi, E., Baghurst, K. & van Klinken, J. (2004). Nutrients for cognitive development in school-aged children. Nutrition Reviews, 62 (8), 295–306.

Delange, F. (2000) The role of iodine in brain development. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 59 , 75–79. Sandstead, H. (2000). Causes of iron and zinc deficiencies and their effects on brain. Journal of Nutrition, 130 , 347–349.

[4] Lieberman, H. (2003). Nutrition, brain function, and cognitive performance. Appetite, 40, 245–254.

Frisvold, D. (2012). Nutrition and cognitive achievement: An evaluation of the school breakfast program. Working Paper, Emory University.

[5] Benton, D. & Roberts, G. (1988). Effect of vitamin and mineral supplementation on intelligence in a sample of schoolchildren. The Lancet, 1, 140–143.

Schoenthaler, S., Amos, S., Doraz, W., Kelly, M., & Wakefield, J. (1991). Controlled trial of vitamin – mineral supplementation on intelligence and brain function. Personality and Individual Differences, 12, 343–350.

Benton, D. & Buts, J. (1990). Vitamins/mineral supplementation and intelligence. The Lancet, 335, 1158–1160.

Nelson, M. (1992) Vitamin and mineral supplementation and academic performance in schoolchildren. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 51, 303–313.

Eysenck, H., & Schoenthaler, S. (1997). Raising IQ level by vitamin and mineral supplementation. In R. Sternberg and E. Grigorenko (Eds.), Intelligence, heredity and environment (pp. 363 – 392). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[6] Kleinman, R., Murphy, J., Little, M., Pagano, M., Wehler, C., Regal, K., & Jellinek, M. (1998) Hunger in children in the United States: Potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics, 101(1), e3.

[7] Jones, T., Borg, W., Boulware, S., McCarthy, G., Sherwin, R., Tamborlane, W. (1995). Enhanced adrenomedullary response and increased susceptibility to neuroglygopenia: Mechanisms underlying the adverse effect of sugar ingestion in children. Journal of Pediatrics, 126, 171–177.

[8] Florence, M., Asbridge, M., & Veugelers, P. (2008). Diet quality and academic performance. Journal of School Health, 78, 209–215.

[9] Meyers, A., Sampson, A., Wietzman, M., Rogers, B., & Kayne, H. (1989). School breakfast program and school performance. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 143, 1234–1239.

Kleinman, R., Murphy, J., Little, M., Pagano, M., Wehler, C., Regal, K., & Jellinek, M. (1998) Hunger in children in the United States: Potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics, 101(1), e3.

[10] Powell, C., Walker, S., Chang, S., & Grantham-McGregor, S. (1998). Nutrition and education: A randomized trial of the effects of breakfast in rural primary school children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68, 873–879.

Cueto, S. (2001). Breakfast and dietary balance: The enKid study. Public Health Nutrition, 4, 1429–1431.

Storey, H., Pearce, J., Ashfield-Watt, P., Wood, L., Baines, E., & Nelson, M. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of the effect of school food and dining room modifications on classroom behaviour in secondary school children. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 65, 32–38.

Hollar, D., Messiah, S., Lopez-Mitnik, G., Hollar, T., Almon, M., & Agatston, A. (2010). Effect of a two-year obesity prevention intervention on percentile changes in body mass index and academic performance in low income elementary school children. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 646–653.

[11] Price, J. (2012). De-fizzing schools: The effect on student behavior of having vending machines in schools. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 41(1), 92–99.

What you need to know about education for health and well-being

Why focus on education for health and well-being.

Children and young people who receive a good quality education are more likely to be healthy, and likewise those who are healthy are better able to learn.

Globally, learners face a range of challenges that stand in the way of their education, their schooling and their futures. A few of these are related to their health and well-being. Estimates show that some 246 million learners experience violence in and around school every year and 73 million children live in extreme poverty, food insecurity and hunger. Pregnancy related complications are the leading cause of death among girls aged 15-19, and the COVID-19 pandemic has vividly highlighted the unmet needs of learners and their mental health.

UNESCO works to promote the physical and mental health and well-being of learners. By reducing health-related barriers to learning, such as gender inequality, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), early and unintended pregnancy, violence and discrimination, and malnutrition, UNESCO, governments and school systems can pose serious threats to the well-being of learners, and to the completion of all learners’ education.

Why is health and well-being key for learners?

The link between education to health and well-being is clear. Education develops the skills, values and attitudes that enable learners to lead healthy and fulfilled lives, make informed decisions, and engage in positive relationships with everyone around them. Poor health can have a detrimental effect on school attendance and academic performance. Health-promoting schools that are safe and inclusive for all children and young people are essential for learning.

Statistics show that higher levels of education among mothers improve children’s nutrition and vaccination rates, while reducing preventable child deaths, maternal mortality and HIV infections. Maternal deaths would be reduced by two thirds, saving 98,000 lives, if all girls completed primary education. There would be two‑thirds fewer child marriages, and an increase in modern contraceptive use, if all girls completed secondary education.

At UNESCO, education for health and well-being refers to resilient, health-promoting education systems that integrate school health and well-being as a fundamental part of their daily mission. Only then will our learners be prepared to thrive, to learn and to build healthy, peaceful and sustainable futures for all.

- The relevance and contributions of education for health and well-being to the advancement of human rights, sustainable development & peace: thematic paper , UNESCO, 2022

How is UNESCO advancing learners’ health and well-being for school and life?

UNESCO has a long-standing commitment to improve health and education outcomes for learners. Guided by the UNESCO Strategy on Education for Health and Well-Being, UNESCO envisions a world where learners thrive and works across three priority areas to ensure all learners are empowered through:

- school systems that promote their physical and mental health and well-being

- quality, gender-transformative comprehensive sexuality education that includes HIV, life skills, family and rights

- safe and inclusive learning environments free from all forms of violence, bullying, stigma and discrimination

Through its unique expertise, wide network and a range of strategic partnerships, UNESCO supports tailored interventions in formal educational settings at regional and country levels, with a focus on adolescents. Key areas of actions include: technical guidance at global levels, and targeted and holistic action at national levels such as the Our Rights, Our Lives, Our Future (O3) programme; joint efforts through the Global Partnership Forum for comprehensive sexuality education and the School-related gender-based violence working group ; guidance on school health and nutrition; advocacy around the International Day against violence and bullying at school ; capacity-building and knowledge generation such as the Health and education resource centre .

UNESCO aims to make health education appropriate and relevant for different age groups including young learners and adolescents, thus working closely with young people and youth networks. It identifies adolescence (ages 10-19) as ‘a critical window of opportunity to invest in education, skills and competencies; with benefits for well-being now, into future adult life, and for the next generation’ and a time when schools should impart healthy habits that will empower adolescents to become healthy citizens. Young People Today is an initiative aiming to improve the health and well-being of young people in the Eastern and Southern Africa region.

Why is comprehensive sexuality education key for learners’ health and well-being?

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) is widely recognised as a key intervention to advance gender equality, healthy relationships and sexual and reproductive health, all of which have been shown to positively improve education and health outcomes.

At UNESCO, CSE is a curriculum-based process of teaching and learning about the cognitive, emotional, physical and social aspects of sexuality. It offers life-saving knowledge and develops the values, skills and behaviours young people need to make informed choices for their health and well-being while promoting respect for human rights, gender equality and diversity. CSE empowers learners to realize their health, well-being and dignity, develop respectful relationships and understand their sexual and health rights throughout their lives. Effective CSE is delivered in an age-appropriate manner.

Without correct knowledge on sexual and reproductive health, learners face risks directly impacting their education and future. For example, early and unintended pregnancy increases the risk of absenteeism, poor academic attainment and early drop-out from school for girls, while also having educational implications for young fathers.

Through its O3 flagship programme, UNESCO contributes to the health and well-being of young people in Africa with a view to reducing new HIV infections, early and unintended pregnancy, gender-based violence, and child and early marriage. The O3 programme has benefitted over 28 million learners so far and has introduced ‘O3Plus’, focusing on actions in favour of young people in tertiary education.

UNESCO’s Foundation for Life and Love campaign (#CSEandMe) aims to highlight the benefits of good quality CSE for all young people. Because CSE is about relationships, gender, puberty, consent, and sexual and reproductive health, for all young people.

Why is UNESCO building back healthy and resilient schools?

As the education of 1.6 billion learners came to a halt as a result of the unprecedented COVID-19 global health pandemic, the world became witness to the crucial importance of schools as lifelines for learners’ health and well-being. Schools are a social safety net providing essential health education and services including meals, identifying signs of mistreatment or violence, establishing links to health services, fostering social connections and promoting physical activity. And without this safety net, millions of learners were at risk.

For example, early and forced marriage and unintended adolescent pregnancy rose during the pandemic and lockdown periods. This resulted in more dropouts from school, leaving learners and girls in particular out of school. The pandemic vividly illustrated the interlinkages between education and health, and the urgent need to work across sectors to advance the interests of future generations, building back resilient education systems to prevent, prepare for and respond to health crises. It also highlighted learners’ unmet need for support around their mental health.

Learner mental health and well-being is an integral part of UNESCO’s work on health education and the promotion of safe and inclusive learning environments. UNESCO joined with UNICEF and the WHO to launch a Technical Advisory Group of experts to advise educational institutions on ensuring schools respond appropriately to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Related items

- Health education

- Nutrition education

- Topics: hea

- See more add

- Submit Member Login

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

Current Issue Links

- Articles in Press

- Past Issues

- Supplement: SNEB 2023 International Conference Proceedings

Submit Mobile

- Submit article Opens in new window

- Call For Papers

- Article Collections

- Submit Article Opens in new window

- Aims and Scope

- For Authors

- Supports Open Access Opens in new window

- Society Membership Opens in new window

- Journal Club Opens in new window

- Facebook Opens in new window

- YouTube Opens in new window

- LinkedIn Opens in new window

Featured This Month

SNAP Student Rules Are Not So Snappy: Lessons Learned From a Qualitative Study of California County Agency Workers

The Influence of the School Neighborhood Food Retail Environment on Unhealthy Food Purchasing Behaviors Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review

Call for Papers: Learn more about our current calls for papers

Professional benefits of being a Reviewer

- Current Issue

Participant Insights From a Family-based Meal Kit Delivery Intervention

A Qualitative Study of Breastfeeding Experiences Among Mothers Who Used Galactagogues to Increase Their Milk Supply

Learning What Works: A Mixed-Methods Study of American Self-identified Food Conservers

Associations between subjective social status and health behaviors among college students, in the news, press release.

Confusing Assistance Requirements Contribute to Food Insecurity Among College Students

Suzanna M. Martinez, PhD, MS, University of California San Francisco, highlights a new study that illustrates how challenging SNAP rules are for college students and those involved in their implementation. The research supports simplifying the student SNAP process to increase participation for eligible students, especially for historically minoritized racial and ethnic groups and low-income students for whom equitable access to SNAP benefits is critical.

Read the Article

Household Food Waste Reduced Through Whole-Family Food Literacy Intervention

How can parents and kids work together to reduce household food waste? Amar Laila, PhD, University of Guelph, discusses the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a new pilot study of Weeknight Supper Savers, a whole-family food literacy intervention that teaches how to prepare, store, and eat leftovers. The tool successfully encouraged families to prepare meals together and reduced food waste.

Participants in School-Based Gardening and Food Programs Benefit From Lasting Impacts on Dietary Behaviors

Christine St. Pierre, MPH, RD, presents the results of a new study to determine the impact on dietary behaviors on current and former elementary school students who participated in FRESHFARM FoodPrints’ school-based gardening and food education classes over the past 15 years. Analysis revealed how this early learning positively influenced food decisions as children grew older, extending into adulthood.

Poor Diet Quality During Adolescence Is Linked to Serious Health Risks

- New Resources

Volume 55, Issue 1 – Slow Cooked: An Unexpected Life in Food Politics by Marion Nestle reviewed by Dr. Jennifer Wilkins, Cornell University. For the full review see this issue .

Volume 54, Issue 12 – Quick recap of the review of The Vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health by Dr. Kritika Gupta, Center for Research Evaluation, the University of Mississippi, reviews. For the full review see this issue .

Volume 54, Issue 11 – Quick recap of the review of Motivational Interviewing in Nutrition and Fitness with Dr. Mateja R. Savoie-Roskos. For the full review see this issue .

Online First

Perceived impacts of urban gardens and peer nutritional counseling for people living with hiv in the dominican republic.

School Nutrition Stakeholders Find Utility in MealSim : An Agent-Based Model

A qualitative study of the meaning of food and religious identity.

NEFPAT Plus: A Valid and Reliable Tool for Assessing the Nutrition Environment in Food Pantries

Journal of nutrition education and behavior.

The Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior ( JNEB ), the official peer-reviewed journal of the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior Opens in new window , since 1969, serves as a global resource to advance nutrition education and behavior related research, practice, and policy. JNEB publishes original research, as well as papers focused on emerging issues, policies and practices broadly related to nutrition education and behavior. These topics include, but are not limited to, nutrition education interventions; theoretical interpretation of behavior; epidemiology of nutrition and health; food systems; food assistance programs; nutrition and behavior assessment; and public health nutrition.

The Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior (SNEB) Opens in new window represents the unique professional interests of nutrition educators in the United States and worldwide. SNEB is dedicated to promoting effective nutrition education and communication to support and improve healthful behaviors and has a vision of healthy communities through nutrition education and advocacy. SNEB provides forums for sharing innovative strategies for nutrition education, expressing a range of views on important issues, and disseminating research findings. Members of SNEB educate individuals, families, fellow professionals, and students, and influence policy makers about nutrition, food, and health.

- More Journal Metrics Opens in new window

- Submit a Manuscript Opens in new window

- Top Social Media Articles

- Time to Online Publication Opens in new window

Most Read (Last 30 Days)

Hierarchy of Food Needs

- Ellyn Satter

Participant Perspectives on the Impact of a School-Based, Experiential Food Education Program Across Childhood, Adolescence, and Young Adulthood

Most cited (previous 3 years).

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- List of Issues

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submit Your Manuscript

- Statistical Methods

- Guidelines for Authors of Educational Material Reviews

- Permission to Reuse

- About Open Access

- Researcher Academy

- For Reviewers

- General Guidelines

- Methods Paper Guidelines

- Qualitative Guidelines

- Quantitative Guidelines

- Questionnaire Methods Guidelines

- Statistical Methods Guidelines

- Systematic Review Guidelines

- Perspective Guidelines

- GEM Reviewing Guidelines

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Disclosures

- Abstracting/Indexing

- Impact/Metrics

- Contact Information

- Editorial Staff and Board

- Info for Advertisers

- Member Access Instructions

- New Content Alerts

- Sponsored Supplements

- Statistical Reviewers

- Reviewer Appreciation

- New Resources for Nutrition Educators

- Submit New Resources for Review

- Guidelines for Writing Reviews of New Resources for Nutrition Educators

- Podcast/Webinars

- New Resources Podcasts

- Press Release & Other Podcasts

- Collections

- Society News

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Nutrition and Healthy Eating

Goal: improve health by promoting healthy eating and making nutritious foods available..

Many people in the United States don’t eat a healthy diet. Healthy People 2030 focuses on helping people get the recommended amounts of healthy foods — like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains — to reduce their risk for chronic diseases and improve their health. 1 The Nutrition and Healthy Eating objectives also aim to help people get recommended amounts of key nutrients, like calcium and potassium.

People who eat too many unhealthy foods — like foods high in saturated fat and added sugars — are at increased risk for obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and other health problems. Strategies and interventions to help people choose healthy foods can help reduce their risk of chronic diseases and improve their overall health.

Some people don’t have the information they need to choose healthy foods. Other people don’t have access to healthy foods or can’t afford to buy enough food. Public health interventions that focus on helping everyone get healthy foods are key to reducing food insecurity and hunger and improving health.

Objective Status

Learn more about objective types

Related Objectives

The following is a sample of objectives related to this topic. Some objectives may include population data.

Nutrition and Healthy Eating — General

Adolescents.

- Heart Disease and Stroke

Overweight and Obesity

Other topics you may be interested in.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015). 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Retrieved from https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines/guidelines/

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Basic Nutrition

Printable Materials and Handouts

Find printable handouts and fact sheets that can be used for health fairs, classes, and other food or nutrition-related events.

Cook up something new in your kitchen with these healthy, delicious recipes.

View four tips to help you save money when food shopping and help the environment.

View printable brochures and handouts with healthy eating tips based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 , including:

- Build a Healthy Eating Routine

- Cut Down on Added Sugars

Browse the MyPlate collection of printable tip sheets and resources. These materials are in the public domain.

Want your kids to learn how to build a healthy meal? Use these clever activity sheets to find ideas and tips!

View this fact sheet with nutrition tips for breastfeeding moms.

View printable materials about food safety, including guides, activity books, and tip sheets.

View lessons, workshops, activities, and curricula for teachers. Topics include food, nutrition, physical activity, and food safety.

Use this checklist to track healthy eating and exercise habits throughout your day!

View tips for building healthy eating habits in infants, toddlers, and preschoolers. This fact sheet is available in 13 languages.

Printable fact sheets for living with and managing diabetes.

FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition developed “Everyday Food Safety” resources to increase food safety awareness among young adults ages 18 – 29. Check out the materials available to use in your classroom, health expo, waiting room, or website.

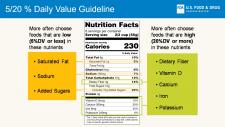

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has updated the Nutrition Facts label on packaged foods and beverages with a new design, making it easier to make informed choices towards healthy eating habits.

This one-page handout highlights the key changes being made to the new Nutrition Facts Label.

Share these tips to reduce food waste, save money, and protect the environment.

Browse handouts and recipes for the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet. Topics include getting more potassium, staying on track, and meal tracking for different calorie levels.

Looking for materials about healthy aging for older adults? Download or order these free handouts and booklets on exercise, nutrition, and other health topics.

View science-based fact sheets and handouts for health fairs and community events.

The Sisters Together program encourages Black women ages 18 and older to reach and maintain a healthy weight. Learn how to bring the program to your community.

Download, print,or order a free copy of this brochure on eating disorders. Also available in Spanish.

Access vitamin and mineral supplement fact sheets for the consumer or health professional. Available in PDF format, and in Spanish.

Find handouts that teach how to build a healthy eating routine, cut down on added sugars, cut down on sodium, and cut down on saturated fat.

Print and share these fact sheets and posters to help people learn key recommendations from the Physical Activity Guidelines. Find materials for adults, older adults, parents and kids, and during and after pregnancy.

Browse by health topic or resource type to find 1-page printable fact sheets written at the 6th- to 8th-grade reading level in English or Spanish.

Challenge yourself to eating fruits and vegetables in new ways by following along to this 30-day calendar.

What are healthy cooking methods, and what equipment do you need for each method? Read this handout to find out.

Use this 31-day calendar to challenge yourself to one choice for a healthy weight each day.

View a table of spices to learn about their flavors and uses.

Use this handout to measure your hunger level on a scale of 1 to 10.

Find handouts to help you manage your weight with healthy eating and physical activity.

Use this handout to plan weekly meals and create a grocery list.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach

Anna zajacova.

Western University

Elizabeth M. Lawrence

University of North Carolina

Adults with higher educational attainment live healthier and longer lives compared to their less educated peers. The disparities are large and widening. We posit that understanding the educational and macro-level contexts in which this association occurs is key to reducing health disparities and improving population health. In this paper, we briefly review and critically assess the current state of research on the relationship between education and health in the United States. We then outline three directions for further research: We extend the conceptualization of education beyond attainment and demonstrate the centrality of the schooling process to health; We highlight the dual role of education a driver of opportunity but also a reproducer of inequality; We explain the central role of specific historical socio-political contexts in which the education-health association is embedded. This research agenda can inform policies and effective interventions to reduce health disparities and improve health of all Americans.

URGENT NEED FOR NEW DIRECTIONS IN EDUCATION-HEALTH RESEARCH

Americans have worse health than people in other high-income countries, and have been falling further behind in recent decades ( 137 ). This is partially due to the large health inequalities and poor health of adults with low education ( 84 ). Understanding the health benefits of education is thus integral to reducing health disparities and improving the well-being of 21 st century populations. Despite tremendous prior research, critical questions about the education-health relationship remain unanswered, in part because education and health are intertwined over the lifespans within and across generations and are inextricably embedded in the broader social context.

We posit that to effectively inform future educational and heath policy, we need to capture education ‘in action’ as it generates and constrains opportunity during the early lifespans of today’s cohorts. First, we need to expand our operationalization of education beyond attainment to consider the long-term educational process that precedes the attainment and its effect on health. Second, we need to re-conceptualize education as not only a vehicle for social success, valuable resources, and good health, but also as an institution that reproduces inequality across generations. And third, we argue that investigators need to bring historical, social and policy contexts into the heart of analyses: how does the education-health association vary across place and time, and how do political forces influence that variation?

During the past several generations, education has become the principal pathway to financial security, stable employment, and social success ( 8 ). At the same time, American youth have experienced increasingly unequal educational opportunities that depend on the schools they attend, the neighborhoods they live in, the color of their skin, and the financial resources of their family. The decline in manufacturing and rise of globalization have eroded the middle class, while the increasing returns to higher education magnified the economic gaps among working adults and families ( 107 ). In addition to these dramatic structural changes, policies that protected the welfare of vulnerable groups have been gradually eroded or dismantled ( 129 ). Together, these changes triggered a precipitous growth of economic and social inequalities in the American society ( 17 ; 106 ).

Unsurprisingly, health disparities grew hand in hand with the socio-economic inequalities. Although the average health of the US population improved over the past decades ( 67 ; 85 ), the gains largely went to the most educated groups. Inequalities in health ( 53 ; 77 ; 99 ) and mortality ( 86 ; 115 ) increased steadily, to a point where we now see an unprecedented pattern: health and longevity are deteriorating among those with less education ( 92 ; 99 ; 121 ; 143 ). With the current focus of the media, policymakers, and the public on the worrisome health patterns among less-educated Americans ( 28 ; 29 ), as well as the growing recognition of the importance of education for health ( 84 ), research on the health returns to education is at a critical juncture. A comprehensive research program is needed to understand how education and health are related, in order to identify effective points of intervention to improve population health and reduce disparities.

The article is organized in two parts. First, we review the current state of research on the relationship between education and health. In broad strokes, we summarize the theoretical and empirical foundations of the education-health relationship and critically assess the literature on the mechanisms and causal influence of education on health. In the second part, we highlight gaps in extant research and propose new directions for innovative research that will fill these gaps. The enormous breadth of the literature on education and health necessarily limits the scope of the review in terms of place and time; we focus on the United States and on findings generated during the rapid expansion of the education-health research in the past 10–15 years. The terms “education” and “schooling” are used interchangeably. Unless we state otherwise, both refer to attained education, whether measured in completed years or credentials. For references, we include prior review articles where available, seminal papers, and recent studies as the best starting points for further reading.

THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN EDUCATION AND HEALTH

Conceptual toolbox for examining the association.

Researchers have generally drawn from three broad theoretical perspectives to hypothesize the relationship between education and health. Much of the education-health research over the past two decades has been grounded in the Fundamental Cause Theory ( 75 ). The FCT posits that social factors such as education are ‘fundamental’ causes of health and disease because they determine access to a multitude of material and non-material resources such as income, safe neighborhoods, or healthier lifestyles, all of which protect or enhance health. The multiplicity of pathways means that even as some mechanisms change or become less important, other mechanisms will continue to channel the fundamental dis/advantages into differential health ( 48 ). The Human Capital Theory (HCT), borrowed from econometrics, conceptualizes education as an investment that yields returns via increased productivity ( 12 ). Education improves individuals’ knowledge, skills, reasoning, effectiveness, and a broad range of other abilities, which can be utilized to produce health ( 93 ). The third approach, the Signaling or Credentialing perspective ( 34 ; 125 ) has been used to explain the observed large discontinuities in health at 12 or 16 years of schooling, typically associated with the receipt of a high school and college degrees, respectively. This perspective views earned credentials as a potent signal about one’s skills and abilities, and emphasizes the economic and social returns to such signals. Thus all three perspectives postulate a causal relationship between education and health and identify numerous mechanisms through which education influences health. The HCT specifies the mechanisms as embodied skills and abilities, FCT emphasizes the dynamism and flexibility of mechanisms, and credentialism identifies social responses to educational attainment. All three theoretical approaches, however, operationalize the complex process of schooling solely in terms of attainment and thus do not focus on differences in educational quality, type, or other institutional factors that might independently influence health. They also focus on individual-level factors: individual attainment, attainment effects, and mechanisms, and leave out the social context in which the education and health processes are embedded.

Observed associations between education and health

Empirically, hundreds of studies have documented “the gradient” whereby more schooling is linked with better health and longer life. A seminal 1973 book by Kitagawa and Hauser powerfully described large differences in mortality by education in the United States ( 71 ), a finding that has since been corroborated in numerous studies ( 31 ; 42 ; 46 ; 109 ; 124 ). In the following decades, nearly all health outcomes were also found strongly patterned by education. Less educated adults report worse general health ( 94 ; 141 ), more chronic conditions ( 68 ; 108 ), and more functional limitations and disability ( 118 ; 119 ; 130 ; 143 ). Objective measures of health, such as biological risk levels, are similarly correlated with educational attainment ( 35 ; 90 ; 140 ), showing that the gradient is not a function of differential reporting or knowledge.

The gradient is evident in men and women ( 139 ) and among all race/ethnic groups ( 36 ). However, meaningful group differences exist ( 60 ; 62 ; 91 ). In particular, education appears to have stronger health effects for women than men ( 111 ) and stronger effects for non-Hispanic whites than minority adults ( 134 ; 135 ) even if the differences are modest for some health outcomes ( 36 ). The observed variations may reflect systematic social differences in the educational process such as quality of schooling, content, or institutional type, as well as different returns to educational attainment in the labor market across population groups ( 26 ). At the same time, the groups share a common macro-level social context, which may underlie the gradient observed for all.

To illustrate the gradient, we analyzed 2002–2016 waves of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from adults aged 25–64. Figure 1 shows the levels of three health outcomes across educational attainment levels in six major demographic groups predicted at age 45. Three observations are noteworthy. First, the gradient is evident for all outcomes and in all race/ethnic/gender groups. Self-rated health exemplifies the staggering magnitude of the inequalities: White men and women without a high school diploma have about 57% chance of reporting fair or poor health, compared to just 9% for college graduates. Second, there are major group differences as well, both in the predicted levels of health problems, as well as in the education effects. The latter are not necessarily visible in the figures but the education effects are stronger for women and weaker for non-white adults as prior studies showed (table with regression model results underlying the prior statement is available from the authors). Third, an intriguing exception pertains to adults with “some college,” whose health is similar to high school graduates’ in health outcomes other than general health, despite their investment in and exposure to postsecondary education. We discuss this anomaly below.

Predicted Probability of Health Problems

Source: 2002–2016 NHIS Survey, Adults Age 25–64

Pathways through which education impacts health

What explains the improved health and longevity of more educated adults? The most prominent mediating mechanisms can be grouped into four categories: economic, health-behavioral, social-psychological, and access to health care. Education leads to better, more stable jobs that pay higher income and allow families to accumulate wealth that can be used to improve health ( 93 ). The economic factors are an important link between schooling and health, estimated to account for about 30% of the correlation ( 36 ). Health behaviors are undoubtedly an important proximal determinant of health but they only explain a part of the effect of schooling on health: adults with less education are more likely to smoke, have an unhealthy diet, and lack exercise ( 37 ; 73 ; 105 ; 117 ). Social-psychological pathways include successful long-term marriages and other sources of social support to help cope with stressors and daily hassles ( 128 ; 131 ). Interestingly, access to health care, while important to individual and population health overall, has a modest role in explaining health inequalities by education ( 61 ; 112 ; 133 ), highlighting the need to look upstream beyond the health care system toward social factors that underlie social disparities in health. Beyond these four groups of mechanisms that have received the most attention by investigators, many others have been examined, such as stress, cognitive and noncognitive skills, or environmental exposures ( 11 ; 43 ). Several excellent reviews further discuss mechanisms ( 2 ; 36 ; 66 ; 70 ; 93 ).

Causal interpretation of the education-health association

A burgeoning number of studies used innovative approaches such as natural experiments and twin design to test whether and how education causally affects health. These analyses are essential because recommendations for educational policies, programs, and interventions seeking to improve population health hinge on the causal impact of schooling on health outcomes. Overall, this literature shows that attainment, measured mostly in completed years of schooling, has a causal impact on health across numerous (though not all) contexts and outcomes.

Natural experiments take advantage of external changes that affect attainment but are unrelated to health, such as compulsory education reforms that raise the minimum years of schooling within a given population. A seminal 2005 study focused on increases in compulsory education between 1915 and 1939 across US states and found that a year of schooling reduced mortality by 3.6% ( 78 ). A re-analysis of the data indicated that taking into account state-level mortality trends rendered the mortality effects null but it also identified a significant and large causal effect on general health ( 88 ). A recent study of a large sample of older Americans reported a similar pattern: a substantial causal effect of education for self-rated health but not for mortality ( 47 ). School reform studies outside the US have reported compelling ( 122 ) or modest but significant ( 32 ) effects of schooling on health, although some studies have found nonsignificant ( 4 ), or even negative effects ( 7 ) for a range of health outcomes.

Twin design studies compare the health of twins with different levels of education. This design minimizes the influence of family resources and genetic differences in skills and health, especially for monozygotic twins, and thus serves to isolate the effect of schooling. In the US, studies using this design generated robust evidence of a causal effect of education on self-rated health ( 79 ), although some research has identified only modest ( 49 ) or not significant ( 3 ; 55 ) effects for other physical and mental health outcomes. Studies drawing on the large twin samples outside of the US have similarly found strong causal effects for mortality ( 80 ) and health ( 14 ; 16 ; 51 ) but again some analyses yielded no causal effects on health ( 13 ; 83 ) or health behaviors ( 14 ). Beyond our brief overview, readers may wish consult additional comprehensive reviews of the causal studies ( 40 ; 45 ; 89 ).

The causal studies add valuable evidence that educational attainment impacts adult health and mortality, even considering some limitations to their internal validity ( 15 ; 88 ). To improve population health and reduce health disparities, however, they should be viewed as a starting point to further research. First, the findings do not show how to improve the quality of schooling or its quantity for in the aggregate population, or how to overcome systematic intergenerational and social differences in educational opportunities. Second, their findings do take into account contexts and conditions in which educational attainment might be particularly important for health. In fact, the variability in the findings may be attributable to the stark differences in contexts across the studies, which include countries characterized by different political systems, different population groups, and birth cohorts ranging from the late 19 th to late 20 th centuries that were exposed to education at very different stages of the educational expansion process ( 9 ).

TOWARD A SOCIALLY-EMBEDDED UNDERSTANDING OF THE EDUCATION-HEALTH RELATIONSHIP

To date, the extensive research we briefly reviewed above has identified substantial health benefits of educational attainment in most contexts in today’s high-income countries. Still, many important questions remain unanswered. We outline three critical directions to gain a deeper understanding of the education-health relationship with particular relevance for policy development. All three directions shift the education-health paradigm to consider how education and health are embedded in life course and social contexts.

First, nearly universally, the education-health literature conceptualizes and operationalizes education in terms of attainment, as years of schooling or completed credentials. However, attainment is only the endpoint, although undoubtedly important, of an extended and extensive process of formal schooling, where institutional quality, type, content, peers, teachers, and many other individual, institutional, and interpersonal factors shape lifecourse trajectories of schooling and health. Understanding the role of the schooling process in health outcome is relevant for policy because it can show whether interventions should be aimed at increasing attainment, or whether it is more important to increase quality, change content, or otherwise improve the educational process at earlier stages for maximum health returns. Second, most studies have implicitly or explicitly treated educational attainment as an exogenous starting point, a driver of opportunities in adulthood. However, education also functions to reproduce inequality across generations. The explicit recognition of the dual function of education is critical to developing education policies that would avoid unintended consequence of increasing inequalities. And third, the review above indicates substantial variation in the education-health association across different historical and social contexts. Education and health are inextricably embedded in these contexts and analyses should therefore include them as fundamental influences on the education-health association. Research on contextual variation has the potential to identify contextual characteristics and even specific policies that exacerbate or reduce educational disparities in health.

We illustrate the key conceptual components of future research into the education-health relationship in Figure 2 . Important intergenerational and individual socio-demographic factors shape educational opportunities and educational trajectories, which are directly related to and captured in measures of educational attainment. This longitudinal and life course process culminates in educational disparities in adult health and mortality. Importantly, the macro-level context underlies every step of this process, shaping each of the concepts and their relationships.

Enriching the conceptualization of educational attainment

In most studies of the education-health associations, educational attainment is modeled using years of schooling, typically specified as a continuous covariate, effectively constraining each additional year to have the same impact. A growing body of research has substituted earned credentials for years. Few studies, however, have considered how the impact of additional schooling is likely to differ across the educational attainment spectrum. For example, one additional year of education compared to zero years may be life-changing by imparting basic literacy and numeracy skills. The completion of 14 rather than 13 years (without the completion of associated degree) could be associated with better health through the accumulation of additional knowledge and skills as well, or perhaps could be without health returns, if it is associated with poor grades, stigma linked to dropping out of college, or accumulated debt ( 63 ; 76 ). Examining the functional form of the education-health association can shed light on how and why education is beneficial for health ( 70 ). For instance, studies found that mortality gradually declines with years of schooling at low levels of educational attainment, with large discontinuities at high school and college degree attainment ( 56 ; 98 ). Such findings can point to the importance of completing a degree, not just increasing the quantity (years) of education. Examining mortality, however, implicitly focused on cohorts who went to school 50–60 years ago, within very different educational and social contexts. For findings relevant to current education policies, we need to focus on examining more recent birth cohorts.

A particularly provocative and noteworthy aspect of the functional form is the attainment group often identified as “some college:” adults who attended college but did not graduate with a four-year degree. Postsecondary educational experiences are increasingly central to the lives of American adults ( 27 ) and college completion has become the minimum requirement for entry into middle class ( 65 ; 87 ). Among high school graduates, over 70% enroll in college ( 22 ) but the majority never earn a four-year degree ( 113 ). In fact,, the largest education-attainment group among non-elderly US adults comprises the 54 million adults (29% of total) with some college or associate’s degree ( 113 ). However, as in Figure 1 , this group often defies the standard gradient in health. Several recent studies have found that the health returns to their postsecondary investments are marginal at best ( 110 ; 123 ; 142 ; 144 ). This finding should spur new research to understand the outcomes of this large population group, and to glean insights into the health returns to the postsecondary schooling process. For instance, in the absence of earning a degree, is greater exposure to college education in terms of semesters or earned credits associated with better health or not? How do the returns to postsecondary schooling differ across the heterogeneous institutions ranging from selective 4-year to for-profit community colleges? How does accumulated college debt influence both dropout and later health? Can we identify circumstances under which some college education is beneficial for health? Understanding the health outcomes for this attainment group can shed light on the aspects of education that are most important for improving health.

A related point pertains to the reliability and validity of self-reported educational attainment. If a respondent reports 16 completed years of education, for example, are they carefully counting the number of years of enrollment, or is 16 shorthand for “completed college”? And, is 16 years the best indicator of college completion in the current context when the median time to earn a four-year degree exceeds 5 years ( 30 )? And, is longer time in college given a degree beneficial for health or does it signify delayed or disrupted educational pathways linked to weaker health benefits ( 132 )? How should we measure part-time enrollment? As studies begin to adjudicate between the health effects of years versus credentials ( 74 ) in the changing landscape of increasingly ‘nontraditional’ pathways through college ( 132 ), this measurement work will be necessary for unbiased and meaningful analyses. An in-depth understanding may necessitate primary data collection and qualitative studies. A feasible direction available with existing data such as the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97) is to assess earned college credits and grades rather than years of education beyond high school.

As indicated in Figure 2 , beyond a more in-depth usage of the attainment information, we argue that more effective conceptualization of the education-health relationship as a developmental life course process will lead to important findings. For instance, two studies published in 2016 used the NLSY97 data to model how gradual increases in education predict within-individual changes in health ( 39 ; 81 ). Both research teams found that gradual accumulation of schooling quantity over time was not associated with gradual improvements in health. The investigators interpreted the null findings as an absence of causal effects of education on health, especially once they included important confounders (defined as cognitive and noncognitive skills and social background). Alternatively, perhaps the within-individual models did not register health because education is a long-term, developing trajectory that cannot be reduced to point-in-time changes in exposure. Criticisms about the technical aspects of theses studies notwithstanding ( 59 ), we believe that these studies and others like them, which wrestle with the question of how to capture education as a long-term process grounded in the broader social context, and how this process is linked to adult health, are desirable and necessary.

Education as (re)producer of inequality

The predominant theoretical framework for studying education and health focuses on how education increases skills, improves problem-solving, enhances employment prospects, and thus opens access to other resources. In sociology, however, education is viewed not (only) as increasing human capital but as a “sieve more than a ladder” ( 126 ), an institution that reproduces inequality across generations ( 54 ; 65 ; 103 ; 114 ). The mechanisms of the reproduction of inequality are multifarious, encompassing systematic differences in school resources, quality of instruction, academic opportunities, peer influences, or teacher expectations ( 54 ; 114 ; 132 ). The dual role of education, both engendering and constraining social opportunities, has been recognized from the discipline’s inception ( 52 ) and has remained the dominant perspective in sociology of education ( 18 ; 126 ). Health disparities research, which has largely dismissed the this perspective as “specious” ( 93 ), could benefit from pivoting toward this complex sociological paradigm.

As demonstrated in Figure 2 , parental SES and other background characteristics are key social determinants that set the stage for one’s educational experiences ( 20 ; 120 ). These characteristics, however, shape not just attainment, but the entire educational and social trajectories that drive and result in particular attainment ( 21 ; 69 ). Their effects range from the differential quality and experiences in daycare or preschool settings ( 6 ), K-12 education ( 24 ; 136 ), as well as postsecondary schooling ( 5 ; 127 ). As a result of systematically different experiences of schooling over the early life course stratified by parental SES, children of low educated parents are unlikely to complete higher education: over half of individuals with college degrees by age 24 came from families in the top quartile of family income compared to just 10% in the bottom quartile ( 23 ).

Unfortunately, prior research has generally operationalized the differences in educational opportunities as confounders of the education-health association or as “selection bias” to be statistically controlled, or best as a moderating influence ( 10 ; 19 ). Rather than remove the important life course effects from the equation, studies that seek to understand how educational and health differences unfold over the life course, and even across generations could yield greater insight ( 50 ; 70 ). A life course, multigenerational approach can provide important recommendations for interventions seeking to avoid the unintended consequence of increasing disparities. Insofar as socially advantaged individuals are generally better positioned to take advantage of interventions, research findings can be used to ensure that policies and programs result in decreasing, rather than unintentionally widening, educational and health disparities.

Education and health in social context

Finally, perhaps the most important and policy-relevant emerging direction to improving our understanding of the education-health relationship is to view both as inextricably embedded within the broad social context. As we highlight in Figure 2 , this context underlies every feature of the development of educational disparities in health. In contrast to the voluminous literature focusing on individual-level schooling and health, there has been a “startling lack of attention to the social/political/economic context” in which the relationships are grounded ( 33 ). By context, we mean the structure of a society that varies across time and place, encompassing all major institutions, policy environments, as well as gender, race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic stratification. Under what circumstances, conditions, and policies are the associations between education and health stronger or weaker?