Press ESC to close

Creating a Comprehensive Literature Review Map: A Step-by-Step Example

- backlinkworks

- Writing Articles & Reviews

- October 16, 2023

A literature review is an essential component of any academic research paper or thesis. IT involves examining existing literature, scholarly articles, books, and other sources related to your research topic. A literature review map acts as a visual representation of the concepts, studies, and theories that have been covered in the literature. In this article, we will guide you through the process of creating a comprehensive literature review map, step-by-step, to help you structure and organize your literature review effectively.

Step 1: Define Your Research Topic

The first step in creating a literature review map is to clearly define your research topic. Be specific and narrow down your focus to ensure that you have a manageable scope for your literature review. Take into consideration the research objectives or guiding questions that will shape your review.

Step 2: Identify Relevant Keywords

Once you have defined your research topic, identify the keywords and search terms that are most relevant to your study. Brainstorm a list of potential keywords that are commonly used in the literature related to your topic. These keywords will help you locate relevant sources during your literature search.

Step 3: Conduct a Thorough Literature Search

Using databases and search engines specific to your field of study, begin conducting a thorough literature search using the identified keywords. Take note of the key articles, books, and studies that are relevant to your research topic. In this step, IT is important to evaluate the credibility and quality of the sources to ensure that you are referring to reputable and reliable information.

Step 4: Read and Analyze the Literature

After collecting a substantial number of sources, carefully read and analyze each one. Highlight key concepts, methodologies, and findings that are relevant to your research. As you progress, make notes or annotations to help you remember important details and connections between different sources.

Step 5: Organize the Literature

Now that you have read and analyzed the literature, IT ‘s time to organize the information into a coherent structure. One effective way to do this is by using a literature review map. Start by creating categories or themes based on the concepts or theories that emerge from the literature. Group together similar ideas or findings to create a visual representation of the interconnectedness of the sources.

Step 6: Create the Literature Review Map

With your categorized information, you can now create the literature review map. This can be done using software such as Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, or dedicated mind mapping tools. Start with your main research topic in the center and branch out with subcategories based on the themes or concepts identified earlier. Connect relevant sources to each subcategory, illustrating how they contribute to the overall understanding of your research topic.

Step 7: Revise and Refine

Review your literature review map for coherence and completeness. Ensure that all the key sources are accurately placed within the appropriate category or subcategory. Check for any gaps in your coverage and make sure that the map represents a comprehensive overview of the literature on your research topic.

Q: How many sources should I include in my literature review map?

A: The number of sources you include will depend on the requirements of your research and the depth of analysis you aim to achieve. However, IT is generally recommended to thoroughly examine a range of sources, including both seminal texts and recent publications, to ensure a well-rounded and comprehensive literature review.

Q: How do I determine the credibility of the sources for my literature review?

A: Evaluating the credibility of your sources is crucial to ensure that you are basing your review on reputable information. Consider the author’s qualifications, the credibility and reputation of the publishing outlet, the presence of citations within the article, and the overall coherence and consistency of the research findings.

Q: Can I use a literature review map for disciplines outside of the humanities and social sciences?

A: Absolutely! While literature reviews are commonly associated with humanities and social sciences, they are applicable to any academic field. Whether you are conducting research in the sciences, engineering, or any other discipline, a literature review map will help you organize and present the relevant scholarly literature specific to your research topic.

By following these step-by-step guidelines, you can create a comprehensive literature review map that will serve as a valuable tool throughout your research. Remember to regularly update and refine your map as you progress in your studies. A well-organized literature review will not only demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of the field, but also provide a solid foundation for your own research and contribute to the wider scholarly conversation.

Understanding the Advantages of SATA Hard Drives

3) top 10 wordpress website packages for beginners.

Recent Posts

- Driving Organic Growth: How a Digital SEO Agency Can Drive Traffic to Your Website

- Mastering Local SEO for Web Agencies: Reaching Your Target Market

- The Ultimate Guide to Unlocking Powerful Backlinks for Your Website

- SEO vs. Paid Advertising: Finding the Right Balance for Your Web Marketing Strategy

- Discover the Secret Weapon for Local SEO Success: Local Link Building Services

Popular Posts

Shocking Secret Revealed: How Article PHP ID Can Transform Your Website!

Uncovering the Top Secret Tricks for Mastering SPIP PHP – You Won’t Believe What You’re Missing Out On!

Discover the Shocking Truth About Your Website’s Ranking – You Won’t Believe What This Checker Reveals!

Unlocking the Secrets to Boosting Your Alexa Rank, Google Pagerank, and Domain Age – See How You Can Dominate the Web!

10 Tips for Creating a Stunning WordPress Theme

Explore topics.

- Backlinks (2,425)

- Blog (2,744)

- Computers (5,318)

- Digital Marketing (7,741)

- Internet (6,340)

- Website (4,705)

- Wordpress (4,705)

- Writing Articles & Reviews (4,208)

How to Master at Literature Mapping: 5 Most Recommended Tools to Use

This article is also available in: Turkish , Spanish, Russian , and Portuguese

After putting in a lot of thought, time, and effort, you’ve finally selected a research topic . As the first step towards conducting a successful and impactful research is completed, what follows it is the gruesome process of literature review . Despite the brainstorming, the struggle of understanding how much literature is enough for your research paper or thesis is very much real. Unlike the old days of flipping through pages for hours in a library, literature has come easy to us due to its availability on the internet through Open Access journals and other publishing platforms. This ubiquity has made it even more difficult to cover only significant data! Nevertheless, an ultimate solution to this problem of conglomerating relevant data is literature mapping .

Table of Contents

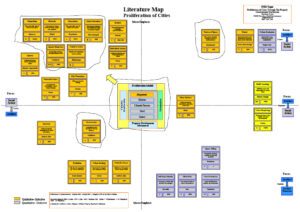

What is Literature Mapping?

Literature mapping is one of the key strategies when searching literature for your research. Since writing a literature review requires following a systematic method to identify, evaluate, and interpret the work of other researchers, academics, and practitioners from the same research field, creating a literature map proves beneficial. Mapping ideas, arguments, and concepts in a literature is an imperative part of literature review. Additionally, it is stated as an established method for externalizing knowledge and thinking processes. A map of literature is a “graphical plan”, “diagrammatic representation”, or a “geographical metaphor” of the research topic.

Researchers are often overwhelmed by the large amount of information they encounter and have difficulty identifying and organizing information in the context of their research. It is recommended that experts in their fields develop knowledge structures that are richer not only in terms of knowledge, but also in terms of the links between this knowledge. This knowledge linking process is termed as literature mapping .

How Literature Mapping Helps Researchers?

Literature mapping helps researchers in following ways:

- It provides concrete evidence of a student’s understanding and interpretation of the research field to share with both peers and professors.

- Switching to another modality helps researchers form patterns to see what might otherwise be hidden in the research area.

- Furthermore, it helps in identifying gaps in pertinent research.

- Finally, t lets researchers identify potential original areas of study and parameters of their work.

How to Make a Literature Map?

Literature mapping is not only an organizational tool, but also a reflexive tool. Furthermore, it distinguishes between declarative knowledge shown by identifying key concepts, ideas and methods, and procedural knowledge shown through classifying these key concepts and establishing links or relationships between them. The literature review conceptualizes research structures as a “knowledge production domain” that defines a productive and ongoing constructive element. Thus, the approaches emphasize the identity of different scientific institutions from different fields, which can be mapped theoretically, methodologically, or fundamentally.

The two literature mapping approaches are:

- Mapping with key ideas or descriptors: This is developed from keywords in research topics.

- Author mapping: This is also termed as citation matching that identifies key experts in the field and may include the use of citations to interlink them.

Generally, literature maps can be subdivided by categorization processes based on theories, definitions, or chronology, and cross-reference between the two types of mapping. Furthermore, researchers use mind maps as a deductive process, general concept-specific mapping (results in a right triangle), or an inductive process mapping to specific concepts (results in an inverted triangle).

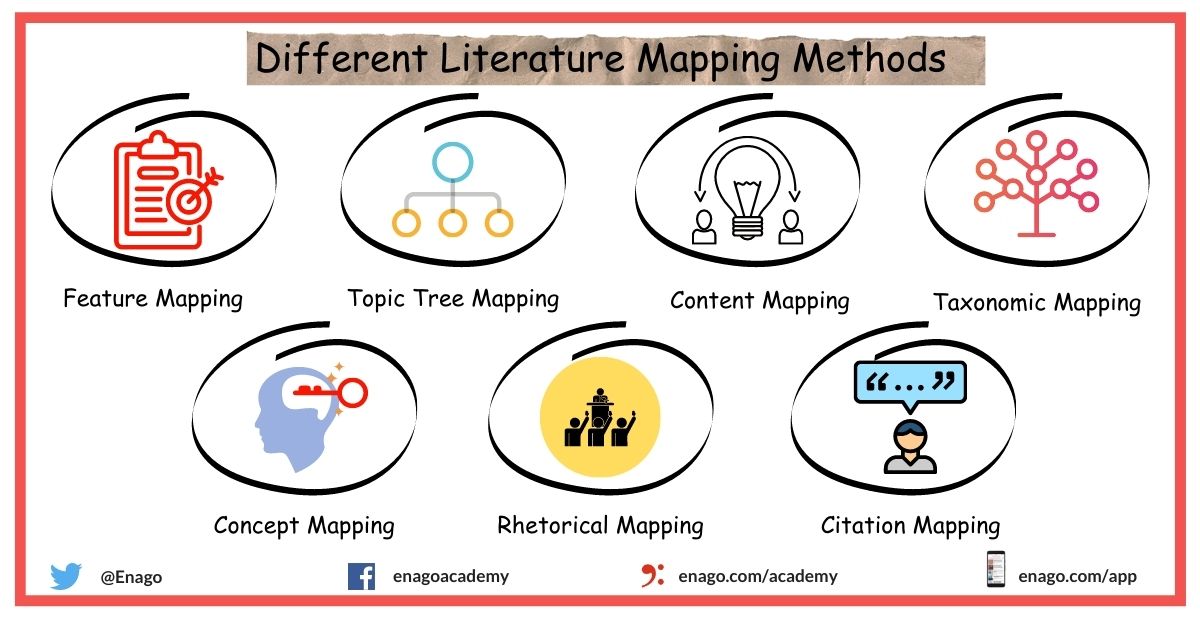

What are Different Literature Mapping Methods?

The different types of literature mapping and representations are as follows:

1. Feature Mapping:

Argument structures developed from summary registration pages.

2. Topic Tree Mapping:

Summary maps showing the development of the topic in sub-themes up to any number of levels.

3. Content Mapping:

Linear structure of organization of content through hierarchical classification.

4. Taxonomic Mapping:

Classification through standardized taxonomies.

5. Concept Mapping:

Linking concepts and processes allows procedural knowledge from declarative information. With a basic principle of cause and effect and problem solving, concept maps can show the relationship between theory and practice.

6. Rhetorical Mapping:

The use of rhetoric communication to discuss, influence, or persuade is particularly important in social policy and political science and can be considered a linking strategy. A number of rhetorical tools have been identified that can be used to present a case, including ethos, metaphor, trope, and irony.

7. Citation Mapping:

Citation mapping or matching is a research process established to specifically establish links between authors by citing their articles. Traditional manual citation indexes have been replaced by automated databases that allow visual mapping methods (e.g. ISI Web of Science). In conclusion, citation matching in a subject area can be effective in determining the frequency of authors and specific articles.

5 Most Useful Literature Mapping Tools

Technology has made the literature mapping process easier now. However, with numerous options available online, it does get difficult for researchers to select one tool that is efficient. These tools are built behind explicit metadata and citations when coupled with some new machine learning techniques. Here are the most recommended literature mapping tools to choose from:

1. Connected Papers

a. Connected Papers is a simple, yet powerful, one-stop visualization tool that uses a single starter article.

b. It is easy to use tool that quickly identifies similar papers with just one “Seed paper” (a relevant paper).

c. Furthermore, it helps to detect seminal papers as well as review papers.

d. It creates a similarity graph not a citation graph and connecting lines (based on the similarity metric).

e. Does not necessarily show direct citation relationships.

f. The identified papers can then be exported into most reference managers like Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley, etc.

2. Inciteful

a. Inciteful is a customizable tool that can be used with multiple starter articles in an iterative process.

b. Results from multiple seed papers can be imported in a batch with a BibTex file.

c. Inciteful produces the following lists of papers by default:

- Similar papers (uses Adamic/Adar index)

- “Most Important Papers in the Graph” (based on PageRank)

- Recent Papers by the Top 100 Authors

- The Most Important Recent Papers

d. It allows filtration of results by keywords.

e. Importantly, seed papers can also be directly added by title or DOI.

a. Litmaps follows an iterative process and creates visualizations for found papers.

b. It allows importing of papers using BibTex format which can be exported from most reference managers like Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley. In addition, it allows paper imports from an ORCID profile.

c. Keywords search method is used to find Litmaps indexed papers.

d. Additionally, it allows setting up email updates of “emergent literature”.

e. Its unique feature that allows overlay of different maps helps to look for overlaps of papers.

f. Lastly, its explore function allows finding related papers to add to the map.

4. Citation-based Sites

a. CoCites is a citation-based method for researching scientific literature.

b. Citation Gecko is a tool for visualizing links between articles.

c. VOSviewer is a software tool for creating and visualizing bibliometric networks. These networks are for example journals, may include researchers or individual publications, which can be generated based on citation, bibliographic matching , co-citation, or co-authorship relationships. VOSviewer also offers text mining functionality that can be used to create and visualize networks of important terms extracted from a scientific literature.

5. Citation Context Tools

a. Scite allow users to see how a publication has been cited by providing the context of the citation and a classification describing whether it provides supporting or contrasting evidence for the cited claim.

b. Semantic Scholar is a freely available, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature.

Have you ever mapped your literature? Did you use any of these tools before? Lastly, what are the strategies and methods you use for literature mapping ? Let us know how this article helped you in creating a hassle-free and comprehensive literature map.

It’s very good and detailed.

It’s very good and clearly . It teaches me how to write literature mapping.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

AI Assistance in Academia for Searching Credible Scholarly Sources

The journey of academia is a grand quest for knowledge, more specifically an adventure to…

- Language & Grammar

Best Plagiarism Checker Tool for Researchers — Top 4 to choose from!

While common writing issues like language enhancement, punctuation errors, grammatical errors, etc. can be dealt…

- Industry News

- Publishing News

2022 in a Nutshell — Reminiscing the year when opportunities were seized and feats were achieved!

It’s beginning to look a lot like success! Some of the greatest opportunities to research…

- Manuscripts & Grants

Writing a Research Literature Review? — Here are tips to guide you through!

Literature review is both a process and a product. It involves searching within a defined…

6 Tools to Create Flawless Presentations and Assignments

No matter how you look at it, presentations are vital to students’ success. It is…

2022 in a Nutshell — Reminiscing the year when opportunities were seized and feats…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Research Guides

Literature Review: A Self-Guided Tutorial

Using concept maps.

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Peer Review

- Reading the Literature

- Developing Research Questions

- Considering Strong Opinions

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Super Searching

- Finding the Full Text

- Citation Searching This link opens in a new window

- When to stop searching

- Citation Management

- Annotating Articles Tip

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- How to Review the Literature

- Using a Synthesis Matrix

- 7. Write literature review

Concept maps or mind maps visually represent relationships of different concepts. In research, they can help you make connections between ideas. You can use them as you are formulating your research question, as you are reading a complex text, and when you are creating a literature review. See the video and examples below.

How to Create a Concept Map

Credit: Penn State Libraries ( CC-BY ) Run Time: 3:13

- Bubbl.us Free version allows 3 mind maps, image export, and sharing.

- MindMeister Free version allows 3 mind maps, sharing, collaborating, and importing. No image-based exporting.

Mind Map of a Text Example

Credit: Austin Kleon. A map I drew of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing in 2008. Tumblr post. April 14, 2016. http://tumblr.austinkleon.com/post/142802684061#notes

Literature Review Mind Map Example

This example shows the different aspects of the author's literature review with citations to scholars who have written about those aspects.

Credit: Clancy Ratliff, Dissertation: Literature Review. Culturecat: Rhetoric and Feminism [blog]. 2 October 2005. http://culturecat.net/node/955 .

- << Previous: Reading the Literature

- Next: 1. Identify the question >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.williams.edu/literature-review

Something went wrong when searching for seed articles. Please try again soon.

No articles were found for that search term.

Author, year The title of the article goes here

LITERATURE REVIEW SOFTWARE FOR BETTER RESEARCH

“This tool really helped me to create good bibtex references for my research papers”

Ali Mohammed-Djafari

Director of Research at LSS-CNRS, France

“Any researcher could use it! The paper recommendations are great for anyone and everyone”

Swansea University, Wales

“As a student just venturing into the world of lit reviews, this is a tool that is outstanding and helping me find deeper results for my work.”

Franklin Jeffers

South Oregon University, USA

“One of the 3 most promising tools that (1) do not solely rely on keywords, (2) does nice visualizations, (3) is easy to use”

Singapore Management University

“Incredibly useful tool to get to know more literature, and to gain insight in existing research”

KU Leuven, Belgium

“Seeing my literature list as a network enhances my thinking process!”

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

“I can’t live without you anymore! I also recommend you to my students.”

Professor at The Chinese University of Hong Kong

“This has helped me so much in researching the literature. Currently, I am beginning to investigate new fields and this has helped me hugely”

Aran Warren

Canterbury University, NZ

“It's nice to get a quick overview of related literature. Really easy to use, and it helps getting on top of the often complicated structures of referencing”

Christoph Ludwig

Technische Universität Dresden, Germany

“Litmaps is extremely helpful with my research. It helps me organize each one of my projects and see how they relate to each other, as well as to keep up to date on publications done in my field”

Daniel Fuller

Clarkson University, USA

“Litmaps is a game changer for finding novel literature... it has been invaluable for my productivity.... I also got my PhD student to use it and they also found it invaluable, finding several gaps they missed”

Varun Venkatesh

Austin Health, Australia

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

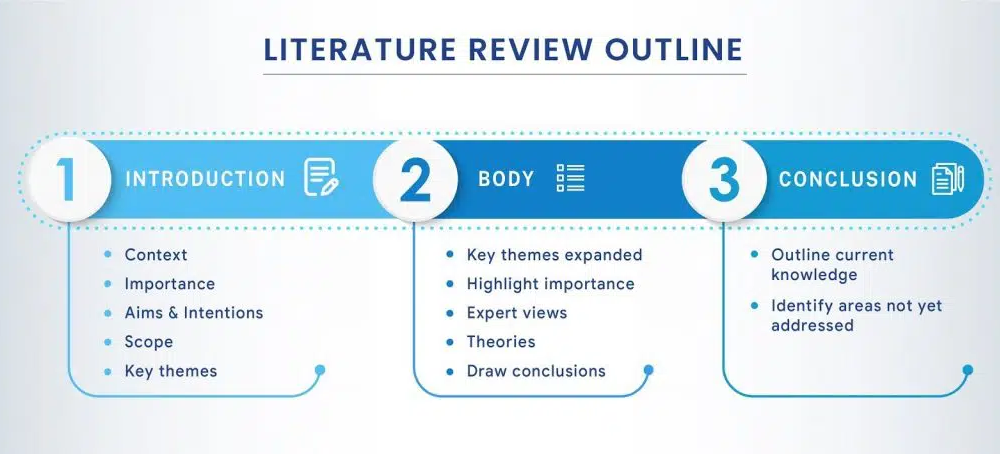

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- Concept Mapping

- Writing a Proposal

- For Faculty

Need help? Ask a librarian

Concept map example: Chocolate Purchasing Factors

What is concept mapping.

Concept Maps are a way to graphically represent ideas and how they relate to each other.

Concept maps may be simple designs illustrating a central theme and a few associated topics or complex structures that delineate hierarchical or multiple relationships.

J.D. Novak developed concept maps in the 1970's to help facilitate the research process for his students. Novak found that visually representing thoughts helped students freely associate ideas without being blocked or intimidated by recording them in a traditional written format.

Concept mapping involves defining a topic; adding related topics; and linking related ideas

Use Bubbl.us or search for more free mind-mapping tools on the web.

More Examples of Concept Maps

- Govt Factors in Consumer Choice

- Mental Health

- Social Psychology

- << Previous: Examples

- Next: Writing a Proposal >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 8:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.njit.edu/literaturereview

Literature Reviews

- Getting Started

- Choosing a Type of Review

- Developing a Research Question

- Searching the Literature

- Searching Tips

- ChatGPT [beta]

- Documenting your Search

- Using Citation Managers

- Concept Mapping

- Concept Map Definition

MindMeister

- Writing the Review

- Further Resources

Additional Tools

Google slides.

GSlides can create concept maps using their Diagram feature. Insert > Diagram > Hierarchy will give you some editable templates to use.

Tutorial on diagrams in GSlides .

MICROSOFT WORD

MS Word can create concept maps using Insert > SmartArt Graphic. Select Process, Cycle, Hierarchy, or Relationship to see templates.

NVivo is software for qualitative analysis that has a concept map feature. Zotero libraries can be uploaded using ris files. NVivo Concept Map information.

A concept map or mind map is a visual representation of knowledge that illustrates relationships between concepts or ideas. It is a tool for organizing and representing information in a hierarchical and interconnected manner. At its core, a concept map consists of nodes, which represent individual concepts or ideas, and links, which depict the relationships between these concepts .

Below is a non-exhaustive list of tools that can facilitate the creation of concept maps.

www.canva.com

Canva is a user-friendly graphic design platform that enables individuals to create visual content quickly and easily. It offers a diverse array of customizable templates, design elements, and tools, making it accessible to users with varying levels of design experience.

Pros: comes with many pre-made concept map templates to get you started

Cons : not all features are available in the free version

Explore Canva concept map templates here .

Note: Although Canva advertises an "education" option, this is for K-12 only and does not apply to university users.

www.lucidchart.com

Lucid has two tools that can create mind maps (what they're called inside Lucid): Lucidchart is the place to build, document, and diagram, and Lucidspark is the place to ideate, connect, and plan.

Lucidchart is a collaborative online diagramming and visualization tool that allows users to create a wide range of diagrams, including flowcharts, org charts, wireframes, and mind maps. Its mind-mapping feature provides a structured framework for brainstorming ideas, organizing thoughts, and visualizing relationships between concepts.

Lucidspark , works as a virtual whiteboard. Here, you can add sticky notes, develop ideas through freehand drawing, and collaborate with your teammates. Has only one template for mind mapping.

Explore Lucid mind map creation here .

How to create mind maps using LucidSpark:

Note: U-M students have access to Lucid through ITS. [ info here ] Choose the "Login w Google" option, use your @umich.edu account, and access should happen automatically.

www.figma.com

Figma is a cloud-based design tool that enables collaborative interface design and prototyping. It's widely used by UI/UX designers to create, prototype, and iterate on digital designs. Figma is the main design tool, and FigJam is their virtual whiteboard:

Figma is a comprehensive design tool that enables designers to create and prototype high-fidelity designs

FigJam focuses on collaboration and brainstorming, providing a virtual whiteboard-like experience, best for concept maps

Explore FigJam concept maps here .

Note: There is a " Figma for Education " version for students that will provide access. Choose the "Login w Google" option, use your @umich.edu account, and access should happen automatically.

www.mindmeister.com

MindMeister is an online mind mapping tool that allows users to visually organize their thoughts, ideas, and information in a structured and hierarchical format. It provides a digital canvas where users can create and manipulate nodes representing concepts or topics, and connect them with lines to show relationships and associations.

Features : collaborative, permits multiple co-authors, and multiple export formats. The free version allows up to 3 mind maps.

Explore MindMeister templates here .

- << Previous: Using Citation Managers

- Next: Writing the Review >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 10:31 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.umich.edu/litreview

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- How to Pick a Topic

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — How to Pick a Topic

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

Picking a Topic and Keywords to Research your Topic

Whether you are writing a literature review as a standalone work or as part of a paper, choosing a topic is an important part of the process. If you haven't select a topic yet for your literature view or you feel that your topic is too broad, this page is for you!

The key to successfully choosing a topic is to find one that is not too broad (impossible to adequately cover) but also not too narrow (not enough has been written about it). Use the tools below to help you brainstorm a topic and keywords that then you can use to search our many databases. Feel free to explore these different options or contact a Subject Specialist if you need more help!

Concept Mapping

- [REMOVE] Mind Mapping (also known as Concept Mapping) A helpful handout to show step by step how to create a concept map to map out a topic.

Picking a topic and search terms

Below are some useful links and handouts that help you develop your topic. Check the handouts in this page. They are useful to help you develop keywords/search terms or to learn the best way to search databases to find articles and books for your research.

- UVA Thinking Tool: Choosing a Topic and Search Terms Provides a template for focusing a research assignment through the brainstorming of ideas, keywords, and other terminology related to a topic.

- UW How to Improve Database Search Results Suggested strategies for retrieving relevant search results

- UCLA: Narrowing a Topic Useful tips on how to narrow a topic when you are getting too many results in your search. From the librarians at UCLA.

- UCLA: Broadering a Topic Useful tips on how to broaden your topic when you are getting few results in your search. From the librarians at UCLA.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Strategies to Find Sources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

Literature mapping.

- Manual Mapping

- Connected Papers

- Open Knowledge Maps

- Research Rabbit

What is Literature Mapping?

Literature mapping is a way of discovering scholarly articles by exploring connections between publications.

Similar articles are often linked by citations, authors, funders, keywords, and other metadata. These connections can be explored manually in a database such as Scopus or by the use of free browser-based tools such as Connected Papers , L itMaps , and Open Knowledge Maps .

The following is an introduction to these four methods.

Video Tutorial (24min)

Literature mapping in 30 minutes (slides).

- Literature Mapping in 30 Minutes Fall 2023 (slides)

- Next: Manual Mapping >>

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 3:29 PM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/litmapping

How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.

The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .

For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically.

- What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?

In some ways, chronology plays a part whichever way you decide to structure your literature review, because you will always, to a certain extent, be analysing how the literature has developed. However, with the chronological approach, the emphasis is very firmly on how the discussion has evolved over time , as opposed to how all the literature links together (which we’ll discuss next ).

Option 2: Thematic (grouped by theme)

The thematic approach to structuring a literature review means organising your literature by theme or category – for example, by independent variables (i.e. factors that have an impact on a specific outcome).

As you’ve been collecting and synthesising literature , you’ll likely have started seeing some themes or patterns emerging. You can then use these themes or patterns as a structure for your body discussion. The thematic approach is the most common approach and is useful for structuring literature reviews in most fields.

For example, if you were researching which factors contributed towards people trusting an organisation, you might find themes such as consumers’ perceptions of an organisation’s competence, benevolence and integrity. Structuring your literature review thematically would mean structuring your literature review’s body section to discuss each of these themes, one section at a time.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when structuring your literature review by themes:

- Are there any patterns that have come to light in the literature?

- What are the central themes and categories used by the researchers?

- Do I have enough evidence of these themes?

PS – you can see an example of a thematically structured literature review in our literature review sample walkthrough video here.

Option 3: Methodological

The methodological option is a way of structuring your literature review by the research methodologies used . In other words, organising your discussion based on the angle from which each piece of research was approached – for example, qualitative , quantitative or mixed methodologies.

Structuring your literature review by methodology can be useful if you are drawing research from a variety of disciplines and are critiquing different methodologies. The point of this approach is to question how existing research has been conducted, as opposed to what the conclusions and/or findings the research were.

For example, a sociologist might centre their research around critiquing specific fieldwork practices. Their literature review will then be a summary of the fieldwork methodologies used by different studies.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself when structuring your literature review according to methodology:

- Which methodologies have been utilised in this field?

- Which methodology is the most popular (and why)?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the various methodologies?

- How can the existing methodologies inform my own methodology?

3: The Conclusion Section

Once you’ve completed the body section of your literature review using one of the structural approaches we discussed above, you’ll need to “wrap up” your literature review and pull all the pieces together to set the direction for the rest of your dissertation or thesis.

The conclusion is where you’ll present the key findings of your literature review. In this section, you should emphasise the research that is especially important to your research questions and highlight the gaps that exist in the literature. Based on this, you need to make it clear what you will add to the literature – in other words, justify your own research by showing how it will help fill one or more of the gaps you just identified.

Last but not least, if it’s your intention to develop a conceptual framework for your dissertation or thesis, the conclusion section is a good place to present this.

Example: Thematically Structured Review

In the video below, we unpack a literature review chapter so that you can see an example of a thematically structure review in practice.

Let’s Recap

In this article, we’ve discussed how to structure your literature review for maximum impact. Here’s a quick recap of what you need to keep in mind when deciding on your literature review structure:

- Just like other chapters, your literature review needs a clear introduction , body and conclusion .

- The introduction section should provide an overview of what you will discuss in your literature review.

- The body section of your literature review can be organised by chronology , theme or methodology . The right structural approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

- The conclusion section should draw together the key findings of your literature review and link them to your research questions.

If you’re ready to get started, be sure to download our free literature review template to fast-track your chapter outline.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

27 Comments

Great work. This is exactly what I was looking for and helps a lot together with your previous post on literature review. One last thing is missing: a link to a great literature chapter of an journal article (maybe with comments of the different sections in this review chapter). Do you know any great literature review chapters?

I agree with you Marin… A great piece

I agree with Marin. This would be quite helpful if you annotate a nicely structured literature from previously published research articles.

Awesome article for my research.

I thank you immensely for this wonderful guide

It is indeed thought and supportive work for the futurist researcher and students

Very educative and good time to get guide. Thank you

Great work, very insightful. Thank you.

Thanks for this wonderful presentation. My question is that do I put all the variables into a single conceptual framework or each hypothesis will have it own conceptual framework?

Thank you very much, very helpful

This is very educative and precise . Thank you very much for dropping this kind of write up .

Pheeww, so damn helpful, thank you for this informative piece.

I’m doing a research project topic ; stool analysis for parasitic worm (enteric) worm, how do I structure it, thanks.

comprehensive explanation. Help us by pasting the URL of some good “literature review” for better understanding.

great piece. thanks for the awesome explanation. it is really worth sharing. I have a little question, if anyone can help me out, which of the options in the body of literature can be best fit if you are writing an architectural thesis that deals with design?

I am doing a research on nanofluids how can l structure it?

Beautifully clear.nThank you!

Lucid! Thankyou!

Brilliant work, well understood, many thanks

I like how this was so clear with simple language 😊😊 thank you so much 😊 for these information 😊

Insightful. I was struggling to come up with a sensible literature review but this has been really helpful. Thank you!

You have given thought-provoking information about the review of the literature.

Thank you. It has made my own research better and to impart your work to students I teach

I learnt a lot from this teaching. It’s a great piece.

I am doing research on EFL teacher motivation for his/her job. How Can I structure it? Is there any detailed template, additional to this?

You are so cool! I do not think I’ve read through something like this before. So nice to find somebody with some genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!

I’m asked to do conceptual, theoretical and empirical literature, and i just don’t know how to structure it

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Search form

You are here, structuring your ideas: creating a literature map.

It is important to have a plan of the areas to be discussed, using this to indicated how these will link together. In the overall structure of the literature review, there should be a logical flow of ideas and within each paragraph there should be a clear theme, around which related ideas are explored and developed. A literature map can be useful for this purpose as it enables you to create a visual representation of the themes and how they could relate to one another.

A literature map (Cresswell, 2011) is a two dimensional diagrammatic representation of information where links are made between concepts by drawing arrows (which could be annotated to define the nature of these links). Constructing a literature map helps you to:

- develop your understanding of the key issues and research findings in the literature

- to organise ideas in your mind

- to see more clearly how different research studies relate to one another and to group those with similar findings.

Your map can then be used as a plan for your literature review.

As well has helping you to organise the literature for your review, a literature map can be used to help you analyse the information in a particular journal article, supporting the exploration of strengths and weaknesses of the methodology and the resultant findings and enabling you to explore how key themes and concepts in the article link together.

It is important to represent the different views and any conflicting research findings that exist in the literature (Newby, 2014). There is a danger of selective referencing, only including literature that supports your own beliefs and findings, disregarding alternative views. This should be avoided as it is based on the assumption that your views are the correct ones, and it is possible that you could miss key ideas and findings that could take your research in new and exciting directions.

- research methods

- literature reviews

Creative Commons

- Directories

- Concept mapping

- Lit review-type sources

- Grey literature

- Public affairs news

- Discipline-specific tools

- Writing & research help

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Literature review toolkit for policy studies

Literature review toolkit for policy studies: Concept mapping

Why create a concept map.

A concept map is a visualization of key idea in your research and the relationships between them. To create a concept map, pick out the main concepts of your topic and brainstorm everything you know about them, drawing shapes around your concepts and clustering the shapes in a way that's meaningful to you. How can this help?

- Helps you pull back to see the broader concepts at play.

- Can help identify the subject-based tool where literature can be found.

- Helps clarify both what you already know and where you have gaps in your knowledge.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Lit review-type sources >>

- Last Updated: Jan 26, 2024 11:12 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/litreviewtoolkit

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Med Educ

- v.7(1); 2018 Feb

Writing an effective literature review

Lorelei lingard.

Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Health Sciences Addition, Western University, London, Ontario Canada

In the Writer’s Craft section we offer simple tips to improve your writing in one of three areas: Energy, Clarity and Persuasiveness. Each entry focuses on a key writing feature or strategy, illustrates how it commonly goes wrong, teaches the grammatical underpinnings necessary to understand it and offers suggestions to wield it effectively. We encourage readers to share comments on or suggestions for this section on Twitter, using the hashtag: #how’syourwriting?

This Writer’s Craft instalment is the first in a two-part series that offers strategies for effectively presenting the literature review section of a research manuscript. This piece alerts writers to the importance of not only summarizing what is known but also identifying precisely what is not, in order to explicitly signal the relevance of their research. In this instalment, I will introduce readers to the mapping the gap metaphor, the knowledge claims heuristic, and the need to characterize the gap.

Mapping the gap

The purpose of the literature review section of a manuscript is not to report what is known about your topic. The purpose is to identify what remains unknown— what academic writing scholar Janet Giltrow has called the ‘knowledge deficit’ — thus establishing the need for your research study [ 1 ]. In an earlier Writer’s Craft instalment, the Problem-Gap-Hook heuristic was introduced as a way of opening your paper with a clear statement of the problem that your work grapples with, the gap in our current knowledge about that problem, and the reason the gap matters [ 2 ]. This article explains how to use the literature review section of your paper to build and characterize the Gap claim in your Problem-Gap-Hook. The metaphor of ‘mapping the gap’ is a way of thinking about how to select and arrange your review of the existing literature so that readers can recognize why your research needed to be done, and why its results constitute a meaningful advance on what was already known about the topic.

Many writers have learned that the literature review should describe what is known. The trouble with this approach is that it can produce a laundry list of facts-in-the-world that does not persuade the reader that the current study is a necessary next step. Instead, think of your literature review as painting in a map of your research domain: as you review existing knowledge, you are painting in sections of the map, but your goal is not to end with the whole map fully painted. That would mean there is nothing more we need to know about the topic, and that leaves no room for your research. What you want to end up with is a map in which painted sections surround and emphasize a white space, a gap in what is known that matters. Conceptualizing your literature review this way helps to ensure that it achieves its dual goal: of presenting what is known and pointing out what is not—the latter of these goals is necessary for your literature review to establish the necessity and importance of the research you are about to describe in the methods section which will immediately follow the literature review.

To a novice researcher or graduate student, this may seem counterintuitive. Hopefully you have invested significant time in reading the existing literature, and you are understandably keen to demonstrate that you’ve read everything ever published about your topic! Be careful, though, not to use the literature review section to regurgitate all of your reading in manuscript form. For one thing, it creates a laundry list of facts that makes for horrible reading. But there are three other reasons for avoiding this approach. First, you don’t have the space. In published medical education research papers, the literature review is quite short, ranging from a few paragraphs to a few pages, so you can’t summarize everything you’ve read. Second, you’re preaching to the converted. If you approach your paper as a contribution to an ongoing scholarly conversation,[ 2 ] then your literature review should summarize just the aspects of that conversation that are required to situate your conversational turn as informed and relevant. Third, the key to relevance is to point to a gap in what is known. To do so, you summarize what is known for the express purpose of identifying what is not known . Seen this way, the literature review should exert a gravitational pull on the reader, leading them inexorably to the white space on the map of knowledge you’ve painted for them. That white space is the space that your research fills.

Knowledge claims

To help writers move beyond the laundry list, the notion of ‘knowledge claims’ can be useful. A knowledge claim is a way of presenting the growing understanding of the community of researchers who have been exploring your topic. These are not disembodied facts, but rather incremental insights that some in the field may agree with and some may not, depending on their different methodological and disciplinary approaches to the topic. Treating the literature review as a story of the knowledge claims being made by researchers in the field can help writers with one of the most sophisticated aspects of a literature review—locating the knowledge being reviewed. Where does it come from? What is debated? How do different methodologies influence the knowledge being accumulated? And so on.

Consider this example of the knowledge claims (KC), Gap and Hook for the literature review section of a research paper on distributed healthcare teamwork:

KC: We know that poor team communication can cause errors. KC: And we know that team training can be effective in improving team communication. KC: This knowledge has prompted a push to incorporate teamwork training principles into health professions education curricula. KC: However, most of what we know about team training research has come from research with co-located teams—i. e., teams whose members work together in time and space. Gap: Little is known about how teamwork training principles would apply in distributed teams, whose members work asynchronously and are spread across different locations. Hook: Given that much healthcare teamwork is distributed rather than co-located, our curricula will be severely lacking until we create refined teamwork training principles that reflect distributed as well as co-located work contexts.

The ‘We know that …’ structure illustrated in this example is a template for helping you draft and organize. In your final version, your knowledge claims will be expressed with more sophistication. For instance, ‘We know that poor team communication can cause errors’ will become something like ‘Over a decade of patient safety research has demonstrated that poor team communication is the dominant cause of medical errors.’ This simple template of knowledge claims, though, provides an outline for the paragraphs in your literature review, each of which will provide detailed evidence to illustrate a knowledge claim. Using this approach, the order of the paragraphs in the literature review is strategic and persuasive, leading the reader to the gap claim that positions the relevance of the current study. To expand your vocabulary for creating such knowledge claims, linking them logically and positioning yourself amid them, I highly recommend Graff and Birkenstein’s little handbook of ‘templates’ [ 3 ].

As you organize your knowledge claims, you will also want to consider whether you are trying to map the gap in a well-studied field, or a relatively understudied one. The rhetorical challenge is different in each case. In a well-studied field, like professionalism in medical education, you must make a strong, explicit case for the existence of a gap. Readers may come to your paper tired of hearing about this topic and tempted to think we can’t possibly need more knowledge about it. Listing the knowledge claims can help you organize them most effectively and determine which pieces of knowledge may be unnecessary to map the white space your research attempts to fill. This does not mean that you leave out relevant information: your literature review must still be accurate. But, since you will not be able to include everything, selecting carefully among the possible knowledge claims is essential to producing a coherent, well-argued literature review.

Characterizing the gap

Once you’ve identified the gap, your literature review must characterize it. What kind of gap have you found? There are many ways to characterize a gap, but some of the more common include:

- a pure knowledge deficit—‘no one has looked at the relationship between longitudinal integrated clerkships and medical student abuse’

- a shortcoming in the scholarship, often due to philosophical or methodological tendencies and oversights—‘scholars have interpreted x from a cognitivist perspective, but ignored the humanist perspective’ or ‘to date, we have surveyed the frequency of medical errors committed by residents, but we have not explored their subjective experience of such errors’

- a controversy—‘scholars disagree on the definition of professionalism in medicine …’

- a pervasive and unproven assumption—‘the theme of technological heroism—technology will solve what ails teamwork—is ubiquitous in the literature, but what is that belief based on?’

To characterize the kind of gap, you need to know the literature thoroughly. That means more than understanding each paper individually; you also need to be placing each paper in relation to others. This may require changing your note-taking technique while you’re reading; take notes on what each paper contributes to knowledge, but also on how it relates to other papers you’ve read, and what it suggests about the kind of gap that is emerging.

In summary, think of your literature review as mapping the gap rather than simply summarizing the known. And pay attention to characterizing the kind of gap you’ve mapped. This strategy can help to make your literature review into a compelling argument rather than a list of facts. It can remind you of the danger of describing so fully what is known that the reader is left with the sense that there is no pressing need to know more. And it can help you to establish a coherence between the kind of gap you’ve identified and the study methodology you will use to fill it.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mark Goldszmidt for his feedback on an early version of this manuscript.

PhD, is director of the Centre for Education Research & Innovation at Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, and professor for the Department of Medicine at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada.

Doing a literature review using digital tools (with Notion template)

I’ve recently revamped my literature review workflow since discovering Notion . Notion is an organization application that allows you to make various pages and databases. It’s kind of like your own personal wiki- you can link your pages and embed databases into another page, adding filters and sorting them using user-set properties. The databases are what I use the most. I’ve essentially transferred all of my excel sheets into Notion databases and find it much easier to filter and sort things now. In this post, I’ll go through how I do my literature review and share a Notion template that you can use.

I like to organize my literature review using various literature review tools along with two relational Notion databases: a ‘literature tracker’ and a ‘literature notes’ matrix. You can see a flow chart of my literature review process below (it’s inspired by this post by Jenn’s Studious Life and the three pass method for reading papers which I wrote about last week in this post ):

As you can see, this process involves a couple of decision points which helps me focus on the most important papers. This is an iterative process that keeps me up to date on relevant research in my field as I am getting new paper alerts in my inbox most days. I used this method quite successfully to write the literature review for my confirmation report and regularly add to it for the expanded version that will become part of my PhD thesis. In this post, I’ll break down how this works for me and how I implement my Notion databases to synthesise the literature I read into a coherent argument.

You can click on the links below to navigate to a particular section of this article:

The literature search

The literature tracker, the literature synthesis matrix, writing your literature review, iterating your literature review, my literature review notion template, some useful resources.

This is always the first step in building your literature review. There are plenty of resources online all about how to start with your search- I find a mixture of database search tools works for me.

The first thing to do when starting your literature review is to identify some keywords to use in your initial searches. It might be worth chatting to your supervisor to make a list of these and then add or remove terms to it as you go down different research routes. You can use keyword searches relevant to your research questions as well tools that find ‘similar’ papers and look at citation links. I also find that just looking through the bibliographies of literature in your field and seeing which papers are regularly cited gives you a good idea of the core papers in your area (you’ll start recognising the key ones after a while). Another method for finding literature is the snowballing method which is particularly useful for conducting a systematic review.

Here are some digital tools I use to help me find literature relevant to my research questions:

Library building and suggestions

Mendeley was my research management tool of choice prior to when I started using Notion to organize all of my literature and create my synthesis matrix. I still use Mendeley as a library just in case anything happens to my Notion. It’s easy to add new papers to your library using the browser extension with just one click. I like that Mendeley allows you to share your folders with colleagues and that I can export bib.tex files straight from my library into overleaf documents where I’m writing up papers and my thesis. You do need to make sure that all of the details are correct before you export the bib.tex files though as this is taken straight from the information plane. I also like to use the tag function in Mendeley to add more specific identifiers than my folders.