Conference Papers

What this handout is about.

This handout outlines strategies for writing and presenting papers for academic conferences.

What’s special about conference papers?

Conference papers can be an effective way to try out new ideas, introduce your work to colleagues, and hone your research questions. Presenting at a conference is a great opportunity for gaining valuable feedback from a community of scholars and for increasing your professional stature in your field.

A conference paper is often both a written document and an oral presentation. You may be asked to submit a copy of your paper to a commentator before you present at the conference. Thus, your paper should follow the conventions for academic papers and oral presentations.

Preparing to write your conference paper

There are several factors to consider as you get started on your conference paper.

Determine the structure and style

How will you structure your presentation? This is an important question, because your presentation format will shape your written document. Some possibilities for your session include:

- A visual presentation, including software such as PowerPoint or Prezi

- A paper that you read aloud

- A roundtable discussion

Presentations can be a combination of these styles. For example, you might read a paper aloud while displaying images. Following your paper, you might participate in an informal conversation with your fellow presenters.

You will also need to know how long your paper should be. Presentations are usually 15-20 minutes. A general rule of thumb is that one double-spaced page takes 2-2.5 minutes to read out loud. Thus an 8-10 page, double-spaced paper is often a good fit for a 15-20 minute presentation. Adhere to the time limit. Make sure that your written paper conforms to the presentation constraints.

Consider the conventions of the conference and the structure of your session

It is important to meet the expectations of your conference audience. Have you been to an academic conference previously? How were presentations structured? What kinds of presentations did you find most effective? What do you know about the particular conference you are planning to attend? Some professional organizations have their own rules and suggestions for writing and presenting for their conferences. Make sure to find out what they are and stick to them.

If you proposed a panel with other scholars, then you should already have a good idea of your panel’s expectations. However, if you submitted your paper individually and the conference organizers placed it on a panel with other papers, you will need additional information.

Will there be a commentator? Commentators, also called respondents or discussants, can be great additions to panels, since their job is to pull the papers together and pose questions. If there will be a commentator, be sure to know when they would like to have a copy of your paper. Observe this deadline.

You may also want to find out what your fellow presenters will be talking about. Will you circulate your papers among the other panelists prior to the conference? Will your papers address common themes? Will you discuss intersections with each other’s work after your individual presentations? How collaborative do you want your panel to be?

Analyze your audience

Knowing your audience is critical for any writing assignment, but conference papers are special because you will be physically interacting with them. Take a look at our handout on audience . Anticipating the needs of your listeners will help you write a conference paper that connects your specific research to their broader concerns in a compelling way.

What are the concerns of the conference?

You can identify these by revisiting the call for proposals and reviewing the mission statement or theme of the conference. What key words or concepts are repeated? How does your work relate to these larger research questions? If you choose to orient your paper toward one of these themes, make sure there is a genuine relationship. Superficial use of key terms can weaken your paper.

What are the primary concerns of the field?

How do you bridge the gap between your research and your field’s broader concerns? Finding these linkages is part of the brainstorming process. See our handout on brainstorming . If you are presenting at a conference that is within your primary field, you should be familiar with leading concerns and questions. If you will be attending an interdisciplinary conference or a conference outside of your field, or if you simply need to refresh your knowledge of what’s current in your discipline, you can:

- Read recently published journals and books, including recent publications by the conference’s featured speakers

- Talk to people who have been to the conference

- Pay attention to questions about theory and method. What questions come up in the literature? What foundational texts should you be familiar with?

- Review the initial research questions that inspired your project. Think about the big questions in the secondary literature of your field.

- Try a free-writing exercise. Imagine that you are explaining your project to someone who is in your department, but is unfamiliar with your specific topic. What can you assume they already know? Where will you need to start in your explanation? How will you establish common ground?

Contextualizing your narrow research question within larger trends in the field will help you connect with your audience. You might be really excited about a previously unknown nineteenth-century poet. But will your topic engage others? You don’t want people to leave your presentation, thinking, “What was the point of that?” By carefully analyzing your audience and considering the concerns of the conference and the field, you can present a paper that will have your listeners thinking, “Wow! Why haven’t I heard about that obscure poet before? She is really important for understanding developments in Romantic poetry in the 1800s!”

Writing your conference paper

I have a really great research paper/manuscript/dissertation chapter on this same topic. Should I cut and paste?

Be careful here. Time constraints and the needs of your audience may require a tightly focused and limited message. To create a paper tailored to the conference, you might want to set everything aside and create a brand new document. Don’t worry—you will still have that paper, manuscript, or chapter if you need it. But you will also benefit from taking a fresh look at your research.

Citing sources

Since your conference paper will be part of an oral presentation, there are special considerations for citations. You should observe the conventions of your discipline with regard to including citations in your written paper. However, you will also need to incorporate verbal cues to set your evidence and quotations off from your text when presenting. For example, you can say: “As Nietzsche said, quote, ‘And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you,’ end quote.” If you use multiple quotations in your paper, think about omitting the terms “quote” and “end quote,” as these can become repetitive. Instead, signal quotations through the inflection of your voice or with strategic pauses.

Organizing the paper

There are numerous ways to effectively organize your conference paper, but remember to have a focused message that fits the time constraints and meets the needs of your audience. You can begin by connecting your research to the audience’s concerns, then share a few examples/case studies from your research, and then, in conclusion, broaden the discussion back out to general issues in the field.

Don’t overwhelm or confuse your audience

You should limit the information that you present. Don’t attempt to summarize your entire dissertation in 10 pages. Instead, try selecting main points and provide examples to support those points. Alternatively, you might focus on one main idea or case study and use 2-4 examples to explain it.

Check for clarity in the text

One way to anticipate how your ideas will sound is to read your paper out loud. Reading out loud is an excellent proofreading technique and is a great way to check the clarity of your ideas; you are likely to hear problems that you didn’t notice in just scanning your draft. Help listeners understand your ideas by making sure that subjects and verbs are clear and by avoiding unnecessarily complex sentences.

Include verbal cues in the text

Make liberal use of transitional phrases like however, therefore, and thus, as well as signpost words like first, next, etc.

If you have 5 main points, say so at the beginning and list those 5 ideas. Refer back to this structure frequently as you transition between sections (“Now, I will discuss my fourth point, the importance of plasma”).

Use a phrase like “I argue” to announce your thesis statement. Be sure that there is only one of these phrases—otherwise your audience will be confused about your central message.

Refer back to the structure, and signal moments where you are transitioning to a new topic: “I just talked about x, now I’m going to talk about y.”

I’ve written my conference paper, now what?

Now that you’ve drafted your conference paper, it’s time for the most important part—delivering it before an audience of scholars in your field! Remember that writing the paper is only one half of what a conference paper entails. It is both a written text and a presentation.

With preparation, your presentation will be a success. Here are a few tips for an effective presentation. You can also see our handout on speeches .

Cues to yourself

Include helpful hints in your personal copy of the paper. You can remind yourself to pause, look up and make eye contact with your audience, or employ body language to enhance your message. If you are using a slideshow, you can indicate when to change slides. Increasing the font size to 14-16 pt. can make your paper easier to read.

Practice, practice, practice

When you practice, time yourself. Are you reading too fast? Are you enunciating clearly? Do you know how to pronounce all of the words in your paper? Record your talk and critically listen to yourself. Practice in front of friends and colleagues.

If you are using technology, familiarize yourself with it. Check and double-check your images. Remember, they are part of your presentation and should be proofread just like your paper. Print a backup copy of your images and paper, and bring copies of your materials in multiple formats, just in case. Be sure to check with the conference organizers about available technology.

Professionalism

The written text is only one aspect of the overall conference paper. The other is your presentation. This means that your audience will evaluate both your work and you! So remember to convey the appropriate level of professionalism.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Adler, Abby. 2010. “Talking the Talk: Tips on Giving a Successful Conference Presentation.” Psychological Science Agenda 24 (4).

Kerber, Linda K. 2008. “Conference Rules: How to Present a Scholarly Paper.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , March 21, 2008. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Conference-Rules-How-to/45734 .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Present a Research Paper | Academic Conference Edition

So you’ve just secured a speaking slot at an academic conference and are getting ready for your presentation. Congrats! However, securing a speaker slot is hard enough; now, you have to turn that fantastic research paper into an even more fantastic presentation.

There are many benefits to presenting your research at an academic conference. You can establish your credibility in the field, meet experts, researchers, editors, and other stakeholders and share your work and talk about what you do with others.

Too much pressure?

Don’t worry; you’ll learn about all the key elements you need to include in your presentation and the dos and don’ts of presenting at a conference in this article.

Key Elements to Include in Your Presentation

You already know that a conference presentation introduces a research paper or discussion topic. A good conference presentation delivers this information in a clear, concise, and interesting way to trigger discussion, curiosity, and interest from the audience. Ensure you have a good presentation by keeping the following things in mind:

- Write a detailed outline (with a thesis, main arguments, and supporting evidence) and come well-prepared (practice, practice, practice)

- Introduce the topic or research

- Talk about your sources and methods used

- Indicate whether there are conflicting views about your topic or research to trigger discussion

- Make a statement about your results

- Use visuals, handouts, slides, or any other presentation tools to your advantage.

Remember, you must address or briefly touch on your finished paper’s main points or arguments during your presentation . Don’t skip entire sections of your research. See more dos and don’ts below.

Dos and Don’ts of Presenting Your Paper at a Conference

1. understand the presentation requirements.

You must first understand your audience to understand the presentation requirements better. Understanding your audience will help you present your work in a way that is relatable and exciting to them. Do your research on the conference criteria and your audience demographics .

Remember, the audience members may not be experts in your field, so make sure you provide adequate background information and any associated facts or data during your presentation. The presented data should answer any research questions you have previously asked in your paper. Consider also contacting other speakers to understand what topics are being covered.

Next, you must ensure any audiovisual tech you need for your presentation will be up and running . Ask the conference producer important questions (if they haven’t told you already), such as:

- Will you speak through a microphone, and if so, which kind (gooseneck, lavalier, wireless)?

- How far away will audience members be able to see (good to know for slide and visual creation)?

- Suppose the conference uses projection stands, equipment, or remote controls that you haven’t used before. Will it take long to familiarize yourself with them (especially good to know if you need to arrive at the conference much earlier)?

- What kind of projector or another tech will be available, and what files can you use for your presentation?

Lastly, you’ll want to know your time limit for the presentation . A typical speaking slot is anywhere from five to ten minutes, with an additional five minutes for questions and answers. Find out from the conference producer and ensure you stick to that (especially while practicing to make it easier for the day of the presentation).

2. Include a Hook and CTA

An engaging introduction and conclusion are just as vital in your paper as in your presentation. Think about how you’ll hook the audience into your presentation and what they’ll leave with (key quotes or takeaways). Don’t forget about a call to action (CTA) at the end; what will the audience members do after watching your presentation?

3. Create a Visual Design

If you’re creating visuals (slideshow, PowerPoint, etc.), ensure all audience members towards the back can clearly see the visuals, and don’t overwhelm them with too many. Additionally, remember that the slides and visuals are there to help your presentation, not replace it. Keep the following tricks in mind for slide creation:

- Keep text to a minimum (only the main talking points)

- Use bullet points as necessary to support your main points

- Choose appropriate fonts and backgrounds (ensure fonts are easy-to-read and straightforward and be aware of background color in contrast with font colors)

- Choose relevant, high-quality images (but you don’t need to include images on each slide).

1. Don't Wing Your Presentation

Your presentation format should look something like this:

- Title (1 slide)

- Research topic and question (1 slide)

- Research Methods (1 slide)

- Data Collected (3-5 slides)

- Research Findings (1-2 slides)

- Implications (1 slide)

- Conclusions (1 slide).

Remember not to simply read off what you wrote in your paper; your presentation should be brief and concise, with only the main talking points. You’re not reading; you’re presenting. Ensure you don’t use present tense when describing results , only past tense. Additionally, don’t use complicated graphs or charts, or distracting colors, shapes, patterns, etc., on the slides.

2. Don’t Look Unprofessional

First impressions matter, especially if this is the first time you’re presenting a paper at a conference. Before you actually present, you want to ensure you’re presentable . Think about your presentation wardrobe. While you may think it’s too early, remembers that you will only have a few seconds or minutes to make a good first impression on your audience.

Additionally, be active and engaging while presenting. Don’t have your hands in your pockets, don’t look down too often, and don’t read your presentation word-for-word from your notes. If you look bored, there’s a high chance that your audience will be bored too.

3. Don't Skip Out on Practicing Your Presentation

Practice your presentation in advance. Learn it inside and out. Practice in front of a mirror while timing yourself. Practice runs are a great way to work on your timing and presentation skills. You want to practice your presentation at least ten times .

To get as close to the real thing as possible, you have to practice your presentation in front of an audience too. You can ask a few friends or colleagues to listen and watch your presentation and give you feedback. In this way, you’ll be able to make any final tweaks to your content before conference presentation day.

Additionally, encourage your listeners to ask questions, as this can prepare you for the Q&A on conference day. Jot down a few answers to common questions within your notes in case they come up again from conference audience members.

Orvium Helps You Stay On Task

Presenting a paper at a conference is a special thing in a researcher’s life, regardless of the presentation jitters you may have. Remember that you must understand the presentation requirements , including a hook and call to action, and create a visual design. Try avoiding the don’ts, and most importantly, don’t forget to practice.

Orvium understands that sometimes it may be hard to find reviewers to listen to your presentation. That’s why we invite everyone to collaborate on our open platform . You can find fellow researchers, publishers, and reviewers and form communities with like-minded people from different disciplines to set you up for success.

We also put together a Full Guide to Planning an Academic Conference to help you with any other conference questions you may have.

And finally, if you like this post we recommend you to read the next one ''How to Get a Speaking Slot | Academic Conference Edition'' and don't forget to follow us on social media ( Twitter , Facebook , Linkedin e Instagram ).

- Academic Resources

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox.

Now check your inbox and click the link to confirm your subscription.

Please enter a valid email address

Oops! There was an error sending the email, please try later.

Roberto Rabasco

+10 years’ experience working for Deutsche Telekom, Just Eat or Asos. Leading, designing and developing high-availability software solutions, he built his own software house in '16

Recommended for you

How to Write a Research Funding Application | Orvium

Increasing Representation and Diversity in Research with Open Science | Orvium

Your Guide to Open Access Week 2023

Reference management. Clean and simple.

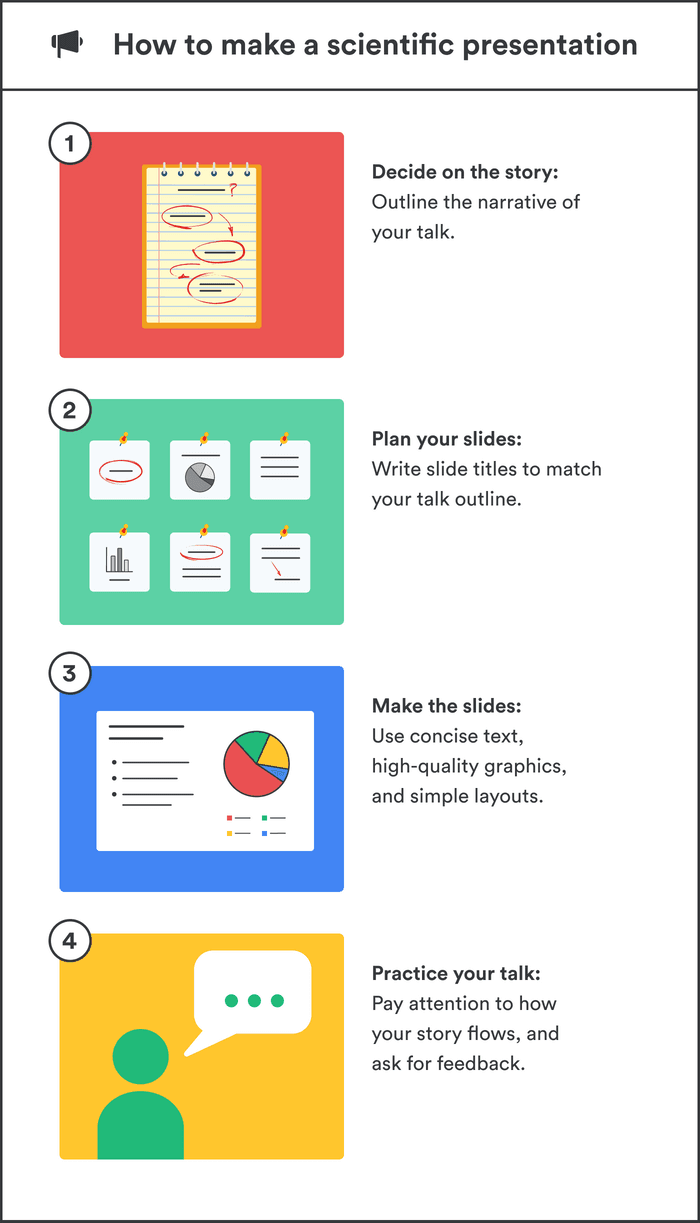

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Ten tips for presenting a conference paper

Advice from a guide prepared by two academics will help you to impress a conference audience.

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

Speaking at academic conferences can be a scary prospect . Here is some advice from “ How to give a conference paper ” by Edward James, emeritus professor of medieval history at University College Dublin , and Farah Mendlesohn, professor of literary history at Anglia Ruskin University

- A conference paper is not an article. You can fit about 2,100 words into a 20-minute paper session. If you try to fit in more, you will either gabble or run over time. Both are not just embarrassing, they are plain rude .

- If it is an international conference, there will be people there to whom English is a second or third language. Even if their English is good, they may not be familiar with your accent. Speak clearly.

- Smile when you start. The importance of this cannot be overstated. Smiling lifts the voice (this is why singers often smile on high notes). It makes you sound enthusiastic even if you aren’t. The audience is on your side. It doesn’t want you to fail. On the whole, this should be an enjoyable experience, and it will be the more so if you start by realising we are all in this together.

- Do not read to the desk. If you hold the paper up at nose level, you will be talking to the room. This helps both to project the voice and to maintain contact with the audience.

- You can fit in only one theoretical idea. There is time to expand on it and to explain how it applies to the texts you are discussing, but you do not have time to discuss more than one.

- Start the paper with your thesis. Even if this isn’t how you write, you need to think of a paper as a guided tour. Your audience needs some clue as to where it is going.

- There is a good chance [that your study of a subject] is incomplete. This is good . It will make the paper seem open to argument. The trick is not to let it look directionless.

- Encourage questions, leave things open, say things like “I haven’t yet thought x through fully” or “I’m planning to consider y at a later date…”. It will enable the audience to feel they can contribute to the development of your ideas. [With] really beautiful papers, all that is left for the audience to do is say “wow”. It’s awkward for the audience: they want to be able to comment; and it’s embarrassing for the presenter who thinks no one liked their paper.

- “Preparation” is important but not “rehearsal”. Too much rehearsal may make you sound dull. The aim is for a paper that sounds spontaneous, but isn’t. Do not practise reading the paper aloud (it will sound tired by the time we hear it), but do practise reading to punctuation from a range of texts.

- Whatever you do, do not imagine that you can take a section of a paper written for a journal, or a chapter written for a book, and simply read it out. A paper written for academic publication is rarely suitable for reading out loud. Get used to the idea that you should write a paper specifically for the conference. It will be less dense, less formal, with shorter sentences, and more signposts for the listeners.

These tips have been reproduced with the consent of the authors and a full version of this guide, which also includes tips on speaking without reading, is available for download here .

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Related articles

How to give a good academic conference paper

Tricks of presenting a successful academic conference paper are revealed by co-author of a popular public speaking guide

Related universities

NIH raises postdoctoral salaries, but below target

Top US funding agency manages record increase in key programme for younger scientists, and sees gains in overall equity, while absorbing net cut in its annual budget

How to win the citation game without becoming a cynic

Boosting your publication metrics need not come at the expense of your integrity if you bear in mind these 10 tips, says Adrian Furnham

Black vice-chancellor eyes new generation of minority researchers

David Mba creates fully funded PhD studentships after taking reins at Birmingham City University

Evaristo fears Goldsmiths cuts imperil black literature master’s

Booker Prize-winning author is latest arts leader to speak out against job shedding at celebrated university

Featured jobs

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

- Presenting the Research Paper

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Writing the Research Paper

Writing an Abstract

Oral presentation, compiling a powerpoint.

Abstract : a short statement that describes a longer work.

- Indicate the subject.

- Describe the purpose of the investigation.

- Briefly discuss the method used.

- Make a statement about the result.

Oral presentations usually introduce a discussion of a topic or research paper. A good oral presentation is focused, concise, and interesting in order to trigger a discussion.

- Be well prepared; write a detailed outline.

- Introduce the subject.

- Talk about the sources and the method.

- Indicate if there are conflicting views about the subject (conflicting views trigger discussion).

- Make a statement about your new results (if this is your research paper).

- Use visual aids or handouts if appropriate.

An effective PowerPoint presentation is just an aid to the presentation, not the presentation itself .

- Be brief and concise.

- Focus on the subject.

- Attract attention; indicate interesting details.

- If possible, use relevant visual illustrations (pictures, maps, charts graphs, etc.).

- Use bullet points or numbers to structure the text.

- Make clear statements about the essence/results of the topic/research.

- Don't write down the whole outline of your paper and nothing else.

- Don't write long full sentences on the slides.

- Don't use distracting colors, patterns, pictures, decorations on the slides.

- Don't use too complicated charts, graphs; only those that are relatively easy to understand.

- << Previous: Writing the Research Paper

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 12:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

- 4 minute read

- 121.9K views

Table of Contents

A research paper presentation is often used at conferences and in other settings where you have an opportunity to share your research, and get feedback from your colleagues. Although it may seem as simple as summarizing your research and sharing your knowledge, successful research paper PowerPoint presentation examples show us that there’s a little bit more than that involved.

In this article, we’ll highlight how to make a PowerPoint presentation from a research paper, and what to include (as well as what NOT to include). We’ll also touch on how to present a research paper at a conference.

Purpose of a Research Paper Presentation

The purpose of presenting your paper at a conference or forum is different from the purpose of conducting your research and writing up your paper. In this setting, you want to highlight your work instead of including every detail of your research. Likewise, a presentation is an excellent opportunity to get direct feedback from your colleagues in the field. But, perhaps the main reason for presenting your research is to spark interest in your work, and entice the audience to read your research paper.

So, yes, your presentation should summarize your work, but it needs to do so in a way that encourages your audience to seek out your work, and share their interest in your work with others. It’s not enough just to present your research dryly, to get information out there. More important is to encourage engagement with you, your research, and your work.

Tips for Creating Your Research Paper Presentation

In addition to basic PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, think about the following when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Know your audience : First and foremost, who are you presenting to? Students? Experts in your field? Potential funders? Non-experts? The truth is that your audience will probably have a bit of a mix of all of the above. So, make sure you keep that in mind as you prepare your presentation.

Know more about: Discover the Target Audience .

- Your audience is human : In other words, they may be tired, they might be wondering why they’re there, and they will, at some point, be tuning out. So, take steps to help them stay interested in your presentation. You can do that by utilizing effective visuals, summarize your conclusions early, and keep your research easy to understand.

- Running outline : It’s not IF your audience will drift off, or get lost…it’s WHEN. Keep a running outline, either within the presentation or via a handout. Use visual and verbal clues to highlight where you are in the presentation.

- Where does your research fit in? You should know of work related to your research, but you don’t have to cite every example. In addition, keep references in your presentation to the end, or in the handout. Your audience is there to hear about your work.

- Plan B : Anticipate possible questions for your presentation, and prepare slides that answer those specific questions in more detail, but have them at the END of your presentation. You can then jump to them, IF needed.

What Makes a PowerPoint Presentation Effective?

You’ve probably attended a presentation where the presenter reads off of their PowerPoint outline, word for word. Or where the presentation is busy, disorganized, or includes too much information. Here are some simple tips for creating an effective PowerPoint Presentation.

- Less is more: You want to give enough information to make your audience want to read your paper. So include details, but not too many, and avoid too many formulas and technical jargon.

- Clean and professional : Avoid excessive colors, distracting backgrounds, font changes, animations, and too many words. Instead of whole paragraphs, bullet points with just a few words to summarize and highlight are best.

- Know your real-estate : Each slide has a limited amount of space. Use it wisely. Typically one, no more than two points per slide. Balance each slide visually. Utilize illustrations when needed; not extraneously.

- Keep things visual : Remember, a PowerPoint presentation is a powerful tool to present things visually. Use visual graphs over tables and scientific illustrations over long text. Keep your visuals clean and professional, just like any text you include in your presentation.

Know more about our Scientific Illustrations Services .

Another key to an effective presentation is to practice, practice, and then practice some more. When you’re done with your PowerPoint, go through it with friends and colleagues to see if you need to add (or delete excessive) information. Double and triple check for typos and errors. Know the presentation inside and out, so when you’re in front of your audience, you’ll feel confident and comfortable.

How to Present a Research Paper

If your PowerPoint presentation is solid, and you’ve practiced your presentation, that’s half the battle. Follow the basic advice to keep your audience engaged and interested by making eye contact, encouraging questions, and presenting your information with enthusiasm.

We encourage you to read our articles on how to present a scientific journal article and tips on giving good scientific presentations .

Language Editing Plus

Improve the flow and writing of your research paper with Language Editing Plus. This service includes unlimited editing, manuscript formatting for the journal of your choice, reference check and even a customized cover letter. Learn more here , and get started today!

- Manuscript Preparation

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

You may also like.

What is a Good H-index?

What is a Corresponding Author?

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to content

- Home – AI for Research

How to present a paper at a conference

Conference paper presentation is a recurrent activity in the life of many scholars. It can be an opportunity not only to showcase your writing prowess but also how powerful an oral presenter you can be. However, though it can be an exciting and career-boosting event, especially for younger inexperienced researchers, it can also be a potential banana skin for any presenter that is not well prepared. The few tips below should make your presentation a breeze.

Make out time for several rehearsals

Whether it is exams you want to write or a conference paper you want to present, adequate preparation is key. Repeated rehearsals of your presentation is one effective way of preparing for the audience you are going to face. Find a space you’ll turn into a mock conference venue and continuously rehearse your presentation there.

You may also want to have a mock audience that will help to evaluate your performance in each rehearsal session in addition to offering useful advice based on their observations. Take note of these observations and any advice, especially constructive criticisms, and endeavor to improve in the areas your mock audience finds you wanting.

If possible, watch videos of previous presentations of the conference organiser. While watching try to observe if the organiser has a particular way of arranging the presentation hall and if the audience is of a particular size in terms of number, how the audience interacts with the presenter, and how the organiser moderates the conference, among others.

All these visual and audio observations will present you with a clearer idea of how to rehearse most effectively. Remember, practice makes perfect, so the more you practice the more you are on your way to an outstanding presentation.

Present authoritatively

A conference paper presentation can be a great opportunity to boost your personality by impressing an audience that may include senior professional colleagues and potential employers from all over the world. Therefore you need to exude authoritativeness in every sentence you make and convince the audience that you not only possess a deep understanding of the subject matter you are presenting but that you can also effectively educate anyone who cares to listen.

Needless to remind you that the best way to authoritativeness is via a painstaking study of all aspects of your paper because knowledge is power so you can only be authoritative if you have a thorough understanding of your topic

However, while arguing forcefully and authoritatively, try to appear modest and friendly rather than overconfident and arrogant. Be sure to include some examples in certain contexts for easier comprehension by your audience.

Adhere to the allotted time

Each conference proceeding is a collection of several papers presented by different scholars. Because of this multiplicity of presentations, conference organisers usually have a time ceiling per presentation (often less than 30 minutes). Your paper may be such that can take more than 30 minutes to be comprehensively presented orally. But with limited time, you do not have the luxury of a comprehensive or elaborate presentation. This means that you have to tailor or rehearse your presentation to reflect only the most important details of your work and nothing else.

These important details should include the purpose of your research, the major theories that underpin it, your research methods, key findings and the significance or importance of the findings, your conclusion(s), and recommendations based on your findings and suggestions for future research. You may also want to tell the audience if you faced any limitations while conducting your research.

In a nutshell, try to conclude your presentation within the allocated time to avoid encroaching on the time of the next presenter and/or being embarrassed by the moderators. It will appear inconsiderate and unprofessional if you encroach on the time reserved for other presenters or conference activities.

Be prepared for the occasional lapses in technology

In these digital days, technology tools and gadgets usually play a disruptive role in many human gatherings, including academic conferences. So chances are that your presentation may be technology-assisted. This means that you need to have a number of “what ifs” in mind as you get ready for the presentation date.

What if the paper you electronically submitted to the organizer is no longer accessible for one reason or another? What if the flash drive or memory card you stored a spare copy of the file fails? The logic here is to preempt any inconveniences that technological failure may cause and have enough soft and hard copy back-ups of your paper so that all your hard work is not ruined by digital inefficiency.

Be open to interacting with the audience

Consider yourself a teacher entering the classroom to disseminate knowledge to learners. Therefore, like every good teacher, you have to adopt a variety of appropriate teaching methods, especially the learner-centered method that encourages active student/audience participation which can come in the form of questions.

Moreover, many conference proceedings usually include question and answer sessions so you must be adequately prepared since questions can come from any part of your paper.

Overcome stage fright

Even though there is nothing to fear or be anxious about (especially if you have rehearsed your presentation repeatedly), stage fright is usually experienced by first-time and younger presenters who are a little bit overwhelmed by the occasion or size of the audience. If you notice early signs of stage fright, try to take deep breaths and be as calm as possible. The more you talk, the more confident you’ll become, and with time the fright usually stops.

Make occasional eye contact with your audience

Remember to frequently maintain eye contact with your audience while presenting your paper. Shying away from eye contact with them can be interpreted as a lack of confidence to face an audience. It can also make the organisers feel you have poor presentation skills.

Consider visuals

Though you will not have time to speak as elaborately as you’ll like, you can still consider using visuals if you and the conference organiser think it will make the presentation better. Using visuals in presentations helps make things clearer for the audience in terms of improved understanding, especially when discussing abstract concepts.

It can be a wise idea to have a chat with presenters at previous editions of the conference you’ll be participating in. This will help you learn from their experience in all aspects of the preparation and give you a clearer picture of what to expect at the conference. If you know any of the conference organisers, it will also help to have a chat with him or her for information on how to prepare and what to expect.

Presenting a conference paper can be a chance for many scholars to enhance their self-esteem and career prospects in front of an audience that may include potential employers, senior colleagues, and other influential personalities. However, the exercise can become a nightmare to forget if you are not well prepared. The few tips above will assist your preparation and hopefully, help you present excellently.

Related posts

How to supervise PhD students?

How to supervise graduate students, leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Privacy Overview

Adding {{itemName}} to cart

Added {{itemName}} to cart

Department of History

- Why Study History?

- Undergraduate

- Think and Do

- Full Site Navigation

- Degree Programs

- Highlighted Courses

- Student Resources

- Undergraduate Advisors

- History Club

- Prospective Students

- Public History PhD Students

- Get Involved

- Graduate Resources

- Faculty Publications

- Digital Humanities

- Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies

- Brick By Brick Blog

- History Faculty Interview Series

Tips for Presenting Conference Papers

Any effective conference presentation must do three things: effectively communicate your arguments and evidence, persuade your audience that they are true, and be interesting and entertaining. These tips will help you accomplish those goals.

Before the Conference

When presenting a paper at a conference, you will be delivering a document that was originally far lengthier than what you will be reading. Therefore, editing your paper will be necessary to present your work in full considering the given time restrictions presented to you at the time of your acceptance to the conference. Typically, most conferences allow each presenter approximately 15- 20 minutes, though this is not always standard and times may vary.

Editing Your Paper

Your time restriction will guide your editing process. What does this mean? It means that you know that you have a certain amount of time to convey the most important aspects of your work. As a general rule, you will have time to make one major point. State it, develop it, and repeat it. You will want to edit your paper accordingly with three necessary components: argument, evidence, and a conclusion. Extract your argument and the strongest supporting evidence from your larger body of work.

An effective rule of thumb to remember while editing is that your primary sources inform your narrative. This is the evidence that you will want to use for your conference paper. Secondary source evidence, while beneficial to your overall work, could weigh down a short and concise conference paper.

After you have extracted a rough draft of your paper in this way, go through and edit for clarity. A conference paper is different than a printed paper; you are presenting the information in an oral format and audience members will not be able to slow you down or ask you to repeat a point that they miss. Make the paper clear for them the first time around.

- Clearly state your argument, almost to the point that you declare that you are stating your argument.

- Organize your information in a highly structured The more transparent your structure, the more likely an audience will be able to follow what you are saying.

- Use clear topic sentences.

- Remove clauses which can be lethal, turning them in to more simple, declarative statements that are easy to understand and easy to read.

- Look for dependent clauses. Sentences with semicolons or dependent clauses may be hard to understand for your listening audience. Listeners also have a difficult time understanding deviation from the narrative so be sure to use examples sparingly.

- Consider your audience. Think about who is going to be there; you will be addressing peers and even distinguished scholars in your field, but you may also be delivering to an audience that is unfamiliar with your field. Think about how your paper will sound when it is being read to this audience.

- Remember to avoid excessive jargon. You will most likely be presenting to a mixed crowd; not everyone will be familiar with jargon related to your topic.

- Use quotations sparingly. It can be difficult to clearly project other voices in your narrative. Paraphrase where you can and only use quotes to add punch when necessary.

- Limit the number of characters you introduce to only your “A list.” Most audience members will not be able to keep up with all of the secondary characters important in your narrative. They may begin to feel lost if you introduce too many persons, especially if they are not as familiar as Poe, Lincoln, Wolfe, MLK, or Joyce.

Once you have written your conference paper, seek peer review. Ask a fellow graduate student or someone who can give you constructive feedback to comment on your paper.

After the preliminary edits, you will begin the second phase of editing which is only determined after you begin practicing reading your paper aloud.

Practice Reading Your Paper

As a general rule, you will want to read directly from your paper during the conference. This will keep you from straying off topic, forgetting vital information, running over time, or rambling. After sufficient practice, if you feel comfortable going off script and think that your talk can be more effective by doing so, do it.

Incessantly practice reading your conference paper aloud and time yourself. Practice reading your paper alone, in front of a mirror, in front of peers, even record or tape yourself. This is the only way you will be able to gauge how quickly or how slowly you will read your paper on the day of the conference.

Practice making eye contact with your audience. If this is anxiety-inducing, at least pretend to do so by casting your gaze toward the back and sides of the room. Be careful not to ignore one side of the audience. Many speakers “side” unconsciously.

If your presentation will include the use of visual aids, be sure to practice with them. Be careful that you continue to face the audience when you refer them to your visuals. Do not read off your visuals.

Timing yourself will also be an indicator of whether or not you need further edits to shorten your paper so it may be presented in full in accordance to the time restrictions. For the average speaker, one double spaced page takes about two minutes to read. This is simply an average. Read at a normal and comfortable pace according to you. If it takes you longer to read, then shorten your paper. It is that simple. You do not want to read so quickly on the day of the conference that your audience may find it distracting or worse yet, they may not be able to follow what you are saying or miss key information that is essential to your argument.

The more you practice reading your conference paper, the more familiar you will become with it. Familiarity is essential because it will allow you to naturally project the rhetorical nuances you want to incorporate in your reading. Your overall tone will improve and you will be able to naturally emphasize the words that you find most important. This will prevent you from delivering a boring paper.

How your paper looks to you will also be important. It’s your paper; no one else is going to see the copy from which you read, so design it in a way that aids your presentation. Some useful formatting techniques you can adopt for your paper include:

- Enlarging your font from a standard 12 to perhaps 14 or 16-point. This will help you see more clearly when you are standing at a podium.

- Paginate. Considering that you will not want to staple your pages together, this is a simple way to ensure that your pages do not come out of order before your presentation.

- Use different colors and/or fonts on words, sentences, or even paragraphs if you need additional visual cues for adding emphasis.

- Make yourself notes in the margin such as “breathe” or “slow down” if you have a tendency to get nervous and speak too quickly.

- If you are using Power Point to aide your presentation, mark in the text of your paper when you need to switch slides. It can be easy to forget to change slides, causing you to have to play catch-up with the slide show, to the detriment of your overall presentation.

If you consider using any of the above formatting techniques, remember to practice with them extensively. Nothing could be worse than forgetting what one of your silent signals was supposed to mean. Using some of these suggestions could be helpful, but using too many could be distracting.

Prior to the conference, you want to edit your paper according to your time restrictions and make it as lean and clear as possible.

A Note On Timeliness

Please submit your paper to the scholar who will be commenting on it in a timely manner. You want to provide them ample time to reflect on your work and make a good impression on anyone and all attendants of the conference. Most of the time the conference committee will give you a deadline by which time you need to submit the long version of your conference paper to them. They will then circulate it to the appropriate persons. Do not miss the deadline to submit your paper. It is unprofessional and will reflect poorly on you. If you make substantial changes to your conference paper after you have already submitted it to the conference committee (say you find new sources that better evidences your argument), send an updated version of your paper directly to the commenter with a polite note addressing what changes you made and why you felt the need to make them at this time.

On the Day of the Conference

Confronting anxiety.

On the day you are to give your paper, don’t be nervous about being nervous. Even the most seasoned professionals feel anxiety about speaking in front of large groups of people and this is a signifier that you are taking this form of scholarly discourse seriously. That added nervous energy can actually be of benefit to you. Channel it into your presentation to add vigor. This is what will help you avoid the trap of delivering a boring presentation.

Bodily Motions & Physical Signs of Anxiety

There are certain rules of conduct that generally apply to most conference settings that you will want to note, particularly your bodily motion and how you present your paper. Even though you will most likely be nervous, try to avoid showing any indication of discomfort through fidgeting or the use of your hands as you speak. Persistently moving your hands and body can be distracting to the audience and you want all attention to be on your words, not on your motions. Try to keep your hands on the lectern, perhaps using your finger to help keep your place as you move your eyes from paper to audience. Your hands can also be used discreetly to help you most effectively transition from page to page as you read.

Professor Linda K. Kerber, in her article, “Conference Rules” describes a technique called “sliding” that is the most effective, non-distracting way to transition from page to page as you read. Many students are used to reading a paper, with one page in front of them and simply turning it upside down to reveal the next page to read. This will leave you an upside down stack in the order in which you began. This method, while not uncommon, can be distracting when turning the page and can lead to unnecessary sound in the microphone or distracting pauses as your audience waits for you to reorient yourself. To avoid this, the “sliding method” should be employed. Begin with the first two pages in front of you. Then proceed to slide the second page onto the first. This not only is a discreet way to move your pages, but it also gives you the advantage of seeing what is forthcoming. Once you have your bodily motions in check, your final task is to assess how to deliver your paper.

Reading the Paper is Part of Conference Etiquette

Many students agonize over the strict adherence to reading directly from the paper for the fear of it being boring, this does not have to be the case. Your personality and cadence are the determining factors between boring and engaging. Remember this because reading your paper is an absolute necessity, especially if this is your first time giving a paper.

Forget all of the inclinations and preconceived notions you have acquired in the past about what a presentation is supposed to be, conferences have a structure all their own. Prior to a graduate conference, many students remember the days of undergraduate when they were told not to read off a paper when presenting. The standard presentation of your work that you once knew is no longer good for the etiquette that is necessary for a conference. Even the most seasoned historians still deliver a conference paper by reading directly off the page. If you feel the urge to improvise or speak off the cuff, remember that you will have an opportunity to speak extemporaneously during the Q & A portion of the conference.

Speaking Off the Cuff Can Ruin an Opportunity for a Good First Impression

It is imperative that you read from the paper, because there are many instances when people begin to speak loosely and this can be devastating for numerous reasons. You may run out of time before you are able to completely present your work. You could loose track of what you are saying and your speech could become tangential. Do not let this happen to you. That can be highly embarrassing and you want to make a good first impression on fellow colleagues and distinguished scholars. You want to be remembered for the content of your work and not for the blunders of your presentation. Reading directly from the page does not assure you a stellar presentation, but it does guarantee that you will not make the massive mistake of getting off topic and will help ensure that you stay within your time limit.

The Two-Minute Warning

During your presentation you will be given a two-minute warning. If the warning comes earlier than expected, this may be the only instance where improvisation is acceptable. You will want to cut to the chase and make sure that you have discussed the most important parts of your paper and conclude before time runs out. Touch on your topic sentences for the rest of the paper and then finish strong with your conclusion. If you know in advance that you will be at risk of running over time, you should make additional cuts. If you do not want to make additional cuts but know that you will be cutting it close on presentation day, have a contingency plan. Create a secondary cue card with your main points and conclusion. When you see the two-minute warning and know you will not be able to read the remainder of your paper, switch over to your cue card. Your main goal at the end of your presentation will be to emphasize the arguments you have made and why they matter.

Handling Comments and the Q&A

The commenter is there to help you. You may think you can remember all he/she has to say about your work, but this cannot be assured, especially if you are nervous while listening. Make sure that your write down his/her comments, critiques, suggestions, and questions. The commenter’s advice will help you strengthen your work as a historian and conference presenter.

The Q&A can be scary. Remember to breathe and take the questions in stride. It might help to write down the question being asked before you attempt to answer it. This will help you digest the question in full and allow you to answer it thoroughly. Not hearing or remember all parts of a person’s question can increase your anxiety when answering and cause you to misspeak.

Don’t Forget the Positives

Beyond the rules and etiquette of a conference, remember that you are there to engage in an exciting scholarly endeavor. Yes, you are making yourself vulnerable intellectually, but bear in mind that all of the distinguished scholars you are speaking before, have also been in your shoes. They are not there to embarrass you, but to support your work and push you further with their inquiries. Embrace the experience, know you are among academic friends and know that as a scholar, you are better for it.

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

What Makes a Great Conference Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide