Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples

Published on November 8, 2019 by Rebecca Bevans . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics . It is most often used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses, that arise from theories.

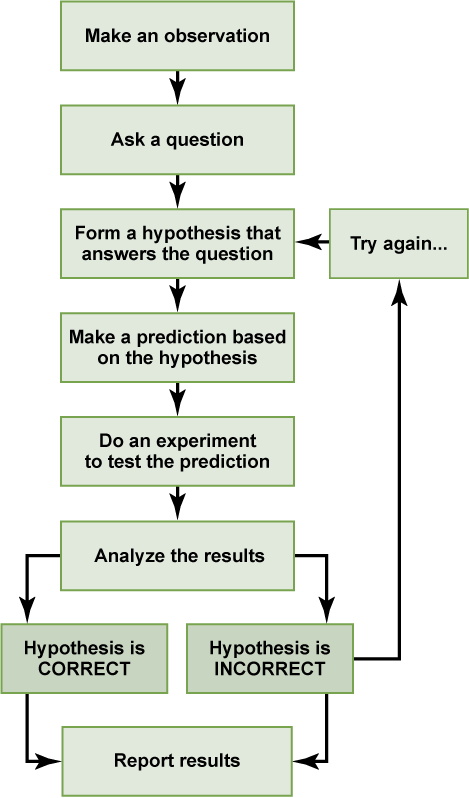

There are 5 main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis as a null hypothesis and alternate hypothesis (H o ) and (H a or H 1 ).

- Collect data in a way designed to test the hypothesis.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test .

- Decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

- Present the findings in your results and discussion section.

Though the specific details might vary, the procedure you will use when testing a hypothesis will always follow some version of these steps.

Table of contents

Step 1: state your null and alternate hypothesis, step 2: collect data, step 3: perform a statistical test, step 4: decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis, step 5: present your findings, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about hypothesis testing.

After developing your initial research hypothesis (the prediction that you want to investigate), it is important to restate it as a null (H o ) and alternate (H a ) hypothesis so that you can test it mathematically.

The alternate hypothesis is usually your initial hypothesis that predicts a relationship between variables. The null hypothesis is a prediction of no relationship between the variables you are interested in.

- H 0 : Men are, on average, not taller than women. H a : Men are, on average, taller than women.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

For a statistical test to be valid , it is important to perform sampling and collect data in a way that is designed to test your hypothesis. If your data are not representative, then you cannot make statistical inferences about the population you are interested in.

There are a variety of statistical tests available, but they are all based on the comparison of within-group variance (how spread out the data is within a category) versus between-group variance (how different the categories are from one another).

If the between-group variance is large enough that there is little or no overlap between groups, then your statistical test will reflect that by showing a low p -value . This means it is unlikely that the differences between these groups came about by chance.

Alternatively, if there is high within-group variance and low between-group variance, then your statistical test will reflect that with a high p -value. This means it is likely that any difference you measure between groups is due to chance.

Your choice of statistical test will be based on the type of variables and the level of measurement of your collected data .

- an estimate of the difference in average height between the two groups.

- a p -value showing how likely you are to see this difference if the null hypothesis of no difference is true.

Based on the outcome of your statistical test, you will have to decide whether to reject or fail to reject your null hypothesis.

In most cases you will use the p -value generated by your statistical test to guide your decision. And in most cases, your predetermined level of significance for rejecting the null hypothesis will be 0.05 – that is, when there is a less than 5% chance that you would see these results if the null hypothesis were true.

In some cases, researchers choose a more conservative level of significance, such as 0.01 (1%). This minimizes the risk of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis ( Type I error ).

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The results of hypothesis testing will be presented in the results and discussion sections of your research paper , dissertation or thesis .

In the results section you should give a brief summary of the data and a summary of the results of your statistical test (for example, the estimated difference between group means and associated p -value). In the discussion , you can discuss whether your initial hypothesis was supported by your results or not.

In the formal language of hypothesis testing, we talk about rejecting or failing to reject the null hypothesis. You will probably be asked to do this in your statistics assignments.

However, when presenting research results in academic papers we rarely talk this way. Instead, we go back to our alternate hypothesis (in this case, the hypothesis that men are on average taller than women) and state whether the result of our test did or did not support the alternate hypothesis.

If your null hypothesis was rejected, this result is interpreted as “supported the alternate hypothesis.”

These are superficial differences; you can see that they mean the same thing.

You might notice that we don’t say that we reject or fail to reject the alternate hypothesis . This is because hypothesis testing is not designed to prove or disprove anything. It is only designed to test whether a pattern we measure could have arisen spuriously, or by chance.

If we reject the null hypothesis based on our research (i.e., we find that it is unlikely that the pattern arose by chance), then we can say our test lends support to our hypothesis . But if the pattern does not pass our decision rule, meaning that it could have arisen by chance, then we say the test is inconsistent with our hypothesis .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Descriptive statistics

- Measures of central tendency

- Correlation coefficient

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Types of interviews

- Cohort study

- Thematic analysis

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Survivorship bias

- Availability heuristic

- Nonresponse bias

- Regression to the mean

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bevans, R. (2023, June 22). Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/hypothesis-testing/

Is this article helpful?

Rebecca Bevans

Other students also liked, choosing the right statistical test | types & examples, understanding p values | definition and examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

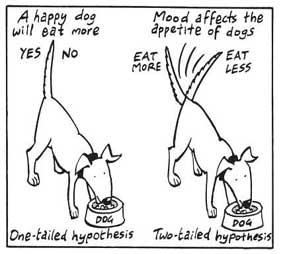

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Developing Theories & Hypotheses

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40843

2.5: Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

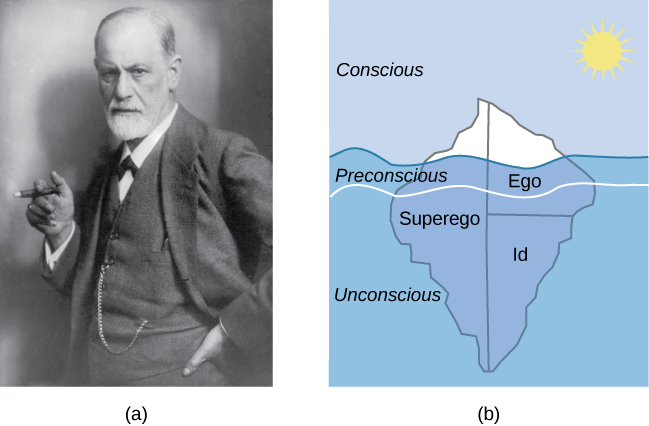

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965) [1] . He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [2] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

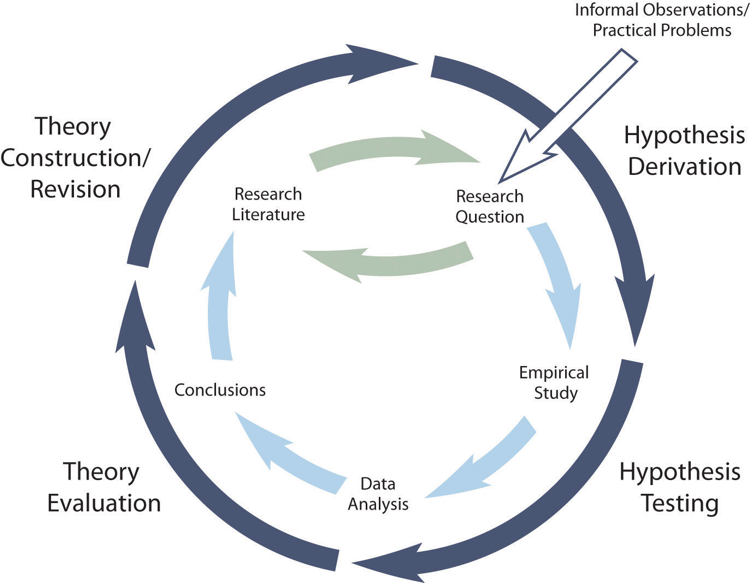

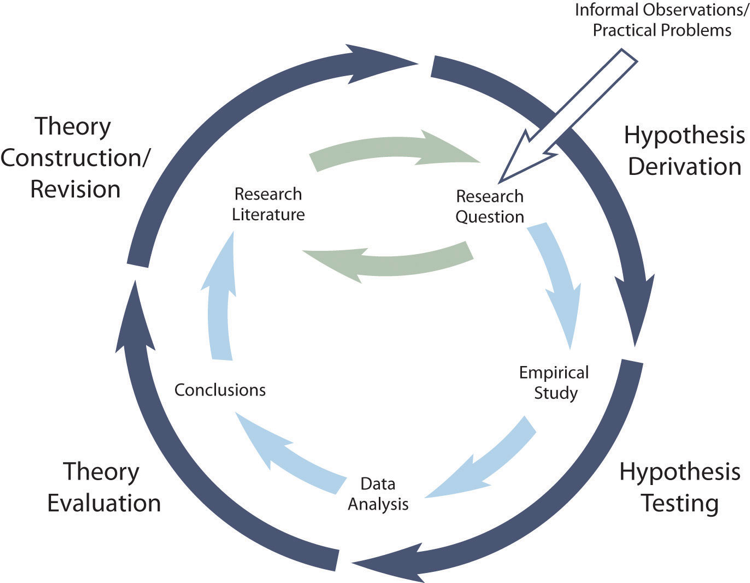

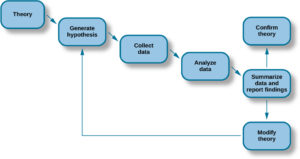

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [3] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] [4] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149 , 269–274 ↵

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

- First Online: 01 January 2024

Cite this chapter

- Hiroshi Ishikawa 3

Part of the book series: Studies in Big Data ((SBD,volume 139))

122 Accesses

This chapter will explain the definition and properties of a hypothesis, the related concepts, and basic methods of hypothesis generation as follows.

Describe the definition, properties, and life cycle of a hypothesis.

Describe relationships between a hypothesis and a theory, a model, and data.

Categorize and explain research questions that provide hints for hypothesis generation.

Explain how to visualize data and analysis results.

Explain the philosophy of science and scientific methods in relation to hypothesis generation in science.

Explain deduction, induction, plausible reasoning, and analogy concretely as reasoning methods useful for hypothesis generation.

Explain problem solving as hypothesis generation methods by using familiar examples.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aufmann RN, Lockwood JS et al (2018) Mathematical excursions. CENGAGE

Google Scholar

Bortolotti L (2008) An introduction to the philosophy of science. Polity

Cairo A (2016) The truthful art: data, charts, and maps for communication. New Riders

Cellucci C (2017) Rethinking knowledge: the heuristic view. Springer

Chang M (2014) Principles of scientific methods. CRC Press

Crease RP (2010) The great equations: breakthroughs in science from Pythagoras to Heisenberg. W. W. Norton & Company

Danks D, Ippoliti E (eds) Building theories: Heuristics and hypotheses in sciences. Springer

Diggle PJ, Chetwynd AG (2011) Statistics and scientific method: an introduction for students and researchers. Oxford University Press

DOAJ (2022) Directory of open access journal. https://doaj.org/ Accessed 2022

Gilchrist P, Wheaton B (2011) Lifestyle sport, public policy and youth engagement: examining the emergence of Parkour. Int J Sport Policy Polit 3(1):109–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2010.547866

Article Google Scholar

Google Maps. https://www.google.com/maps Accessed 2022.

Ishikawa H (2015) Social big data mining. CRC Press

Järvinen P (2008) Mapping research questions to research methods. In: Avison D, Kasper GM, Pernici B, Ramos I, Roode D (eds) Advances in information systems research, education and practice. Proceedings of IFIP 20th world computer congress, TC 8, information systems, vol 274. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09682-7-9_3

JAXA (2022) Martian moons eXploration. http://www.mmx.jaxa.jp/en/ . Accessed 2022

Lewton T (2020) How the bits of quantum gravity can buzz. Quanta Magazine. 2020. https://www.quantamagazine.org/gravitons-revealed-in-the-noise-of-gravitational-waves-20200723/ . Accessed 2022

Mahajan S (2014) The art of insight in science and engineering: Mastering complexity. The MIT Press

Méndez A, Rivera–Valentín EG (2017) The equilibrium temperature of planets in elliptical orbits. Astrophys J Lett 837(1)

NASA (2022) Mars sample return. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/missions/mars-sample-return-msr Accessed 2022

OpenStreetMap (2022). https://www.openstreetmap.org . Accessed 2022

Pólya G (2009) Mathematics and plausible reasoning: vol I: induction and analogy in mathematics. Ishi Press

Pólya G, Conway JH (2014) How to solve it. Princeton University Press

Rehm J (2019) The four fundamental forces of nature. Live science https://www.livescience.com/the-fundamental-forces-of-nature.html

Sadler-Smith E (2015) Wallas’ four-stage model of the creative process: more than meets the eye? Creat Res J 27(4):342–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2015.1087277

Siegel E, This is why physicists think string theory might be our ‘theory of everything.’ Forbes, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2018/05/31/this-is-why-physicists-think-string-theory-might-be-our-theory-of-everything/?sh=b01d79758c25

Zeitz P (2006) The art and craft of problem solving. Wiley

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Systems Design, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Hino, Tokyo, Japan

Hiroshi Ishikawa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hiroshi Ishikawa .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ishikawa, H. (2024). Hypothesis. In: Hypothesis Generation and Interpretation. Studies in Big Data, vol 139. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43540-9_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43540-9_2

Published : 01 January 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-43539-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-43540-9

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Developing a Hypothesis

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965) [1] . He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [2] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.3 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [3] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] [4] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149 , 269–274 ↵

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

A coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena.

A specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate.

A cyclical process of theory development, starting with an observed phenomenon, then developing or using a theory to make a specific prediction of what should happen if that theory is correct, testing that prediction, refining the theory in light of the findings, and using that refined theory to develop new hypotheses, and so on.

The ability to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and the possibility to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false.

Developing a Hypothesis Copyright © 2022 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Theories, Hypotheses, and Laws: Definitions, examples, and their roles in science

by Anthony Carpi, Ph.D., Anne E. Egger, Ph.D.

Listen to this reading

Did you know that the idea of evolution had been part of Western thought for more than 2,000 years before Charles Darwin was born? Like many theories, the theory of evolution was the result of the work of many different scientists working in different disciplines over a period of time.

A scientific theory is an explanation inferred from multiple lines of evidence for some broad aspect of the natural world and is logical, testable, and predictive.

As new evidence comes to light, or new interpretations of existing data are proposed, theories may be revised and even change; however, they are not tenuous or speculative.

A scientific hypothesis is an inferred explanation of an observation or research finding; while more exploratory in nature than a theory, it is based on existing scientific knowledge.

A scientific law is an expression of a mathematical or descriptive relationship observed in nature.

Imagine yourself shopping in a grocery store with a good friend who happens to be a chemist. Struggling to choose between the many different types of tomatoes in front of you, you pick one up, turn to your friend, and ask her if she thinks the tomato is organic . Your friend simply chuckles and replies, "Of course it's organic!" without even looking at how the fruit was grown. Why the amused reaction? Your friend is highlighting a simple difference in vocabulary. To a chemist, the term organic refers to any compound in which hydrogen is bonded to carbon. Tomatoes (like all plants) are abundant in organic compounds – thus your friend's laughter. In modern agriculture, however, organic has come to mean food items grown or raised without the use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, or other additives.

So who is correct? You both are. Both uses of the word are correct, though they mean different things in different contexts. There are, of course, lots of words that have more than one meaning (like bat , for example), but multiple meanings can be especially confusing when two meanings convey very different ideas and are specific to one field of study.

- Scientific theories

The term theory also has two meanings, and this double meaning often leads to confusion. In common language, the term theory generally refers to speculation or a hunch or guess. You might have a theory about why your favorite sports team isn't playing well, or who ate the last cookie from the cookie jar. But these theories do not fit the scientific use of the term. In science, a theory is a well-substantiated and comprehensive set of ideas that explains a phenomenon in nature. A scientific theory is based on large amounts of data and observations that have been collected over time. Scientific theories can be tested and refined by additional research , and they allow scientists to make predictions. Though you may be correct in your hunch, your cookie jar conjecture doesn't fit this more rigorous definition.

All scientific disciplines have well-established, fundamental theories . For example, atomic theory describes the nature of matter and is supported by multiple lines of evidence from the way substances behave and react in the world around us (see our series on Atomic Theory ). Plate tectonic theory describes the large scale movement of the outer layer of the Earth and is supported by evidence from studies about earthquakes , magnetic properties of the rocks that make up the seafloor , and the distribution of volcanoes on Earth (see our series on Plate Tectonic Theory ). The theory of evolution by natural selection , which describes the mechanism by which inherited traits that affect survivability or reproductive success can cause changes in living organisms over generations , is supported by extensive studies of DNA , fossils , and other types of scientific evidence (see our Charles Darwin series for more information). Each of these major theories guides and informs modern research in those fields, integrating a broad, comprehensive set of ideas.

So how are these fundamental theories developed, and why are they considered so well supported? Let's take a closer look at some of the data and research supporting the theory of natural selection to better see how a theory develops.

Comprehension Checkpoint

- The development of a scientific theory: Evolution and natural selection

The theory of evolution by natural selection is sometimes maligned as Charles Darwin 's speculation on the origin of modern life forms. However, evolutionary theory is not speculation. While Darwin is rightly credited with first articulating the theory of natural selection, his ideas built on more than a century of scientific research that came before him, and are supported by over a century and a half of research since.

- The Fixity Notion: Linnaeus

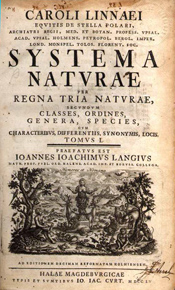

Figure 1: Cover of the 1760 edition of Systema Naturae .

Research about the origins and diversity of life proliferated in the 18th and 19th centuries. Carolus Linnaeus , a Swedish botanist and the father of modern taxonomy (see our module Taxonomy I for more information), was a devout Christian who believed in the concept of Fixity of Species , an idea based on the biblical story of creation. The Fixity of Species concept said that each species is based on an ideal form that has not changed over time. In the early stages of his career, Linnaeus traveled extensively and collected data on the structural similarities and differences between different species of plants. Noting that some very different plants had similar structures, he began to piece together his landmark work, Systema Naturae, in 1735 (Figure 1). In Systema , Linnaeus classified organisms into related groups based on similarities in their physical features. He developed a hierarchical classification system , even drawing relationships between seemingly disparate species (for example, humans, orangutans, and chimpanzees) based on the physical similarities that he observed between these organisms. Linnaeus did not explicitly discuss change in organisms or propose a reason for his hierarchy, but by grouping organisms based on physical characteristics, he suggested that species are related, unintentionally challenging the Fixity notion that each species is created in a unique, ideal form.

- The age of Earth: Leclerc and Hutton

Also in the early 1700s, Georges-Louis Leclerc, a French naturalist, and James Hutton , a Scottish geologist, began to develop new ideas about the age of the Earth. At the time, many people thought of the Earth as 6,000 years old, based on a strict interpretation of the events detailed in the Christian Old Testament by the influential Scottish Archbishop Ussher. By observing other planets and comets in the solar system , Leclerc hypothesized that Earth began as a hot, fiery ball of molten rock, mostly consisting of iron. Using the cooling rate of iron, Leclerc calculated that Earth must therefore be at least 70,000 years old in order to have reached its present temperature.

Hutton approached the same topic from a different perspective, gathering observations of the relationships between different rock formations and the rates of modern geological processes near his home in Scotland. He recognized that the relatively slow processes of erosion and sedimentation could not create all of the exposed rock layers in only a few thousand years (see our module The Rock Cycle ). Based on his extensive collection of data (just one of his many publications ran to 2,138 pages), Hutton suggested that the Earth was far older than human history – hundreds of millions of years old.

While we now know that both Leclerc and Hutton significantly underestimated the age of the Earth (by about 4 billion years), their work shattered long-held beliefs and opened a window into research on how life can change over these very long timescales.

- Fossil studies lead to the development of a theory of evolution: Cuvier

Figure 2: Illustration of an Indian elephant jaw and a mammoth jaw from Cuvier's 1796 paper.

With the age of Earth now extended by Leclerc and Hutton, more researchers began to turn their attention to studying past life. Fossils are the main way to study past life forms, and several key studies on fossils helped in the development of a theory of evolution . In 1795, Georges Cuvier began to work at the National Museum in Paris as a naturalist and anatomist. Through his work, Cuvier became interested in fossils found near Paris, which some claimed were the remains of the elephants that Hannibal rode over the Alps when he invaded Rome in 218 BCE . In studying both the fossils and living species , Cuvier documented different patterns in the dental structure and number of teeth between the fossils and modern elephants (Figure 2) (Horner, 1843). Based on these data , Cuvier hypothesized that the fossil remains were not left by Hannibal, but were from a distinct species of animal that once roamed through Europe and had gone extinct thousands of years earlier: the mammoth. The concept of species extinction had been discussed by a few individuals before Cuvier, but it was in direct opposition to the Fixity of Species concept – if every organism were based on a perfectly adapted, ideal form, how could any cease to exist? That would suggest it was no longer ideal.

While his work provided critical evidence of extinction , a key component of evolution , Cuvier was highly critical of the idea that species could change over time. As a result of his extensive studies of animal anatomy, Cuvier had developed a holistic view of organisms , stating that the

number, direction, and shape of the bones that compose each part of an animal's body are always in a necessary relation to all the other parts, in such a way that ... one can infer the whole from any one of them ...

In other words, Cuvier viewed each part of an organism as a unique, essential component of the whole organism. If one part were to change, he believed, the organism could not survive. His skepticism about the ability of organisms to change led him to criticize the whole idea of evolution , and his prominence in France as a scientist played a large role in discouraging the acceptance of the idea in the scientific community.

- Studies of invertebrates support a theory of change in species: Lamarck

Jean Baptiste Lamarck, a contemporary of Cuvier's at the National Museum in Paris, studied invertebrates like insects and worms. As Lamarck worked through the museum's large collection of invertebrates, he was impressed by the number and variety of organisms . He became convinced that organisms could, in fact, change through time, stating that

... time and favorable conditions are the two principal means which nature has employed in giving existence to all her productions. We know that for her time has no limit, and that consequently she always has it at her disposal.

This was a radical departure from both the fixity concept and Cuvier's ideas, and it built on the long timescale that geologists had recently established. Lamarck proposed that changes that occurred during an organism 's lifetime could be passed on to their offspring, suggesting, for example, that a body builder's muscles would be inherited by their children.

As it turned out, the mechanism by which Lamarck proposed that organisms change over time was wrong, and he is now often referred to disparagingly for his "inheritance of acquired characteristics" idea. Yet despite the fact that some of his ideas were discredited, Lamarck established a support for evolutionary theory that others would build on and improve.

- Rock layers as evidence for evolution: Smith

In the early 1800s, a British geologist and canal surveyor named William Smith added another component to the accumulating evidence for evolution . Smith observed that rock layers exposed in different parts of England bore similarities to one another: These layers (or strata) were arranged in a predictable order, and each layer contained distinct groups of fossils . From this series of observations , he developed a hypothesis that specific groups of animals followed one another in a definite sequence through Earth's history, and this sequence could be seen in the rock layers. Smith's hypothesis was based on his knowledge of geological principles , including the Law of Superposition.

The Law of Superposition states that sediments are deposited in a time sequence, with the oldest sediments deposited first, or at the bottom, and newer layers deposited on top. The concept was first expressed by the Persian scientist Avicenna in the 11th century, but was popularized by the Danish scientist Nicolas Steno in the 17th century. Note that the law does not state how sediments are deposited; it simply describes the relationship between the ages of deposited sediments.

Figure 3: Engraving from William Smith's 1815 monograph on identifying strata by fossils.

Smith backed up his hypothesis with extensive drawings of fossils uncovered during his research (Figure 3), thus allowing other scientists to confirm or dispute his findings. His hypothesis has, in fact, been confirmed by many other scientists and has come to be referred to as the Law of Faunal Succession. His work was critical to the formation of evolutionary theory as it not only confirmed Cuvier's work that organisms have gone extinct , but it also showed that the appearance of life does not date to the birth of the planet. Instead, the fossil record preserves a timeline of the appearance and disappearance of different organisms in the past, and in doing so offers evidence for change in organisms over time.

- The theory of evolution by natural selection: Darwin and Wallace

It was into this world that Charles Darwin entered: Linnaeus had developed a taxonomy of organisms based on their physical relationships, Leclerc and Hutton demonstrated that there was sufficient time in Earth's history for organisms to change, Cuvier showed that species of organisms have gone extinct , Lamarck proposed that organisms change over time, and Smith established a timeline of the appearance and disappearance of different organisms in the geological record .

Figure 4: Title page of the 1859 Murray edition of the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin.

Charles Darwin collected data during his work as a naturalist on the HMS Beagle starting in 1831. He took extensive notes on the geology of the places he visited; he made a major find of fossils of extinct animals in Patagonia and identified an extinct giant ground sloth named Megatherium . He experienced an earthquake in Chile that stranded beds of living mussels above water, where they would be preserved for years to come.

Perhaps most famously, he conducted extensive studies of animals on the Galápagos Islands, noting subtle differences in species of mockingbird, tortoise, and finch that were isolated on different islands with different environmental conditions. These subtle differences made the animals highly adapted to their environments .

This broad spectrum of data led Darwin to propose an idea about how organisms change "by means of natural selection" (Figure 4). But this idea was not based only on his work, it was also based on the accumulation of evidence and ideas of many others before him. Because his proposal encompassed and explained many different lines of evidence and previous work, they formed the basis of a new and robust scientific theory regarding change in organisms – the theory of evolution by natural selection .

Darwin's ideas were grounded in evidence and data so compelling that if he had not conceived them, someone else would have. In fact, someone else did. Between 1858 and 1859, Alfred Russel Wallace , a British naturalist, wrote a series of letters to Darwin that independently proposed natural selection as the means for evolutionary change. The letters were presented to the Linnean Society of London, a prominent scientific society at the time (see our module on Scientific Institutions and Societies ). This long chain of research highlights that theories are not just the work of one individual. At the same time, however, it often takes the insight and creativity of individuals to put together all of the pieces and propose a new theory . Both Darwin and Wallace were experienced naturalists who were familiar with the work of others. While all of the work leading up to 1830 contributed to the theory of evolution , Darwin's and Wallace's theory changed the way that future research was focused by presenting a comprehensive, well-substantiated set of ideas, thus becoming a fundamental theory of biological research.

- Expanding, testing, and refining scientific theories

- Genetics and evolution: Mendel and Dobzhansky

Since Darwin and Wallace first published their ideas, extensive research has tested and expanded the theory of evolution by natural selection . Darwin had no concept of genes or DNA or the mechanism by which characteristics were inherited within a species . A contemporary of Darwin's, the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel , first presented his own landmark study, Experiments in Plant Hybridization, in 1865 in which he provided the basic patterns of genetic inheritance , describing which characteristics (and evolutionary changes) can be passed on in organisms (see our Genetics I module for more information). Still, it wasn't until much later that a "gene" was defined as the heritable unit.

In 1937, the Ukrainian born geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky published Genetics and the Origin of Species , a seminal work in which he described genes themselves and demonstrated that it is through mutations in genes that change occurs. The work defined evolution as "a change in the frequency of an allele within a gene pool" ( Dobzhansky, 1982 ). These studies and others in the field of genetics have added to Darwin's work, expanding the scope of the theory .

- Evolution under a microscope: Lenski

More recently, Dr. Richard Lenski, a scientist at Michigan State University, isolated a single Escherichia coli bacterium in 1989 as the first step of the longest running experimental test of evolutionary theory to date – a true test meant to replicate evolution and natural selection in the lab.

After the single microbe had multiplied, Lenski isolated the offspring into 12 different strains , each in their own glucose-supplied culture, predicting that the genetic make-up of each strain would change over time to become more adapted to their specific culture as predicted by evolutionary theory . These 12 lines have been nurtured for over 40,000 bacterial generations (luckily bacterial generations are much shorter than human generations) and exposed to different selective pressures such as heat , cold, antibiotics, and infection with other microorganisms. Lenski and colleagues have studied dozens of aspects of evolutionary theory with these genetically isolated populations . In 1999, they published a paper that demonstrated that random genetic mutations were common within the populations and highly diverse across different individual bacteria . However, "pivotal" mutations that are associated with beneficial changes in the group are shared by all descendants in a population and are much rarer than random mutations, as predicted by the theory of evolution by natural selection (Papadopoulos et al., 1999).

- Punctuated equilibrium: Gould and Eldredge

While established scientific theories like evolution have a wealth of research and evidence supporting them, this does not mean that they cannot be refined as new information or new perspectives on existing data become available. For example, in 1972, biologist Stephen Jay Gould and paleontologist Niles Eldredge took a fresh look at the existing data regarding the timing by which evolutionary change takes place. Gould and Eldredge did not set out to challenge the theory of evolution; rather they used it as a guiding principle and asked more specific questions to add detail and nuance to the theory. This is true of all theories in science: they provide a framework for additional research. At the time, many biologists viewed evolution as occurring gradually, causing small incremental changes in organisms at a relatively steady rate. The idea is referred to as phyletic gradualism , and is rooted in the geological concept of uniformitarianism . After reexamining the available data, Gould and Eldredge came to a different explanation, suggesting that evolution consists of long periods of stability that are punctuated by occasional instances of dramatic change – a process they called punctuated equilibrium .

Like Darwin before them, their proposal is rooted in evidence and research on evolutionary change, and has been supported by multiple lines of evidence. In fact, punctuated equilibrium is now considered its own theory in evolutionary biology. Punctuated equilibrium is not as broad of a theory as natural selection . In science, some theories are broad and overarching of many concepts, such as the theory of evolution by natural selection; others focus on concepts at a smaller, or more targeted, scale such as punctuated equilibrium. And punctuated equilibrium does not challenge or weaken the concept of natural selection; rather, it represents a change in our understanding of the timing by which change occurs in organisms , and a theory within a theory. The theory of evolution by natural selection now includes both gradualism and punctuated equilibrium to describe the rate at which change proceeds.

- Hypotheses and laws: Other scientific concepts

One of the challenges in understanding scientific terms like theory is that there is not a precise definition even within the scientific community. Some scientists debate over whether certain proposals merit designation as a hypothesis or theory , and others mistakenly use the terms interchangeably. But there are differences in these terms. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for an observable phenomenon. Hypotheses , just like theories , are based on observations from research . For example, LeClerc did not hypothesize that Earth had cooled from a molten ball of iron as a random guess; rather, he developed this hypothesis based on his observations of information from meteorites.

A scientist often proposes a hypothesis before research confirms it as a way of predicting the outcome of study to help better define the parameters of the research. LeClerc's hypothesis allowed him to use known parameters (the cooling rate of iron) to do additional work. A key component of a formal scientific hypothesis is that it is testable and falsifiable. For example, when Richard Lenski first isolated his 12 strains of bacteria , he likely hypothesized that random mutations would cause differences to appear within a period of time in the different strains of bacteria. But when a hypothesis is generated in science, a scientist will also make an alternative hypothesis , an explanation that explains a study if the data do not support the original hypothesis. If the different strains of bacteria in Lenski's work did not diverge over the indicated period of time, perhaps the rate of mutation was slower than first thought.

So you might ask, if theories are so well supported, do they eventually become laws? The answer is no – not because they aren't well-supported, but because theories and laws are two very different things. Laws describe phenomena, often mathematically. Theories, however, explain phenomena. For example, in 1687 Isaac Newton proposed a Theory of Gravitation, describing gravity as a force of attraction between two objects. As part of this theory, Newton developed a Law of Universal Gravitation that explains how this force operates. This law states that the force of gravity between two objects is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between those objects. Newton 's Law does not explain why this is true, but it describes how gravity functions (see our Gravity: Newtonian Relationships module for more detail). In 1916, Albert Einstein developed his theory of general relativity to explain the mechanism by which gravity has its effect. Einstein's work challenges Newton's theory, and has been found after extensive testing and research to more accurately describe the phenomenon of gravity. While Einstein's work has replaced Newton's as the dominant explanation of gravity in modern science, Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation is still used as it reasonably (and more simply) describes the force of gravity under many conditions. Similarly, the Law of Faunal Succession developed by William Smith does not explain why organisms follow each other in distinct, predictable ways in the rock layers, but it accurately describes the phenomenon.

Theories, hypotheses , and laws drive scientific progress