- Open access

- Published: 06 March 2024

The evolving role of social media in enhancing quality of life: a global perspective across 10 countries

- Roy Rillera Marzo 1 , 2 ,

- Hana W. Jun Chen 3 ,

- Absar Ahmad 4 ,

- Hui Zhu Thew 5 ,

- Ja Shen Choy 6 ,

- Chee Han Ng 6 ,

- Chen Loong Alyx Chew 6 ,

- Petra Heidler 7 , 8 ,

- Isabel King 9 ,

- Rajeev Shrestha 10 ,

- Farzana Rahman 11 ,

- Jehan Akhter Rana 12 ,

- Tornike Khoshtaria 13 ,

- Arian Matin 14 ,

- Nugzar Todua 15 ,

- Burcu Küçük Biçer 16 ,

- Erwin Faller 17 , 18 ,

- Randy A. Tudy 19 ,

- Aries Baldonado 20 ,

- Criselle Angeline Penamante 21 , 22 ,

- Rafidah Bahari 23 ,

- Delan Ameen Younus 24 ,

- Zjwan Mohammed Ismail 25 ,

- Masoud Lotfizadeh 26 ,

- Shehu Muhammad Hassan 27 ,

- Rahamatu Shamsiyyah Iliya 28 ,

- Asari E. Inyang 29 ,

- Theingi Maung Maung 30 ,

- Win Myint Oo 31 ,

- Ohnmar Myint 32 ,

- Anil Khadka 33 ,

- Swosti Acharya 34 ,

- Soe Soe Aye 35 ,

- Thein Win Naing 36 ,

- Myat Thida Win 37 ,

- Ye Wint Kyaw 38 ,

- Pramila Pudasaini Thapa 39 ,

- Josana Khanal 40 ,

- Sudip Bhattacharya 41 ,

- Khadijah Abid 42 ,

- Mochammad Fahlevi 43 ,

- Mohammed Aljuaid 44 ,

- Radwa Abdullah El-Abasir 45 &

- Mohamed E. G. Elsayed 46 , 47

Archives of Public Health volume 82 , Article number: 28 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1143 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Excessive or inappropriate use of social media has been linked to disruptions in regular work, well-being, mental health, and overall reduction of quality of life. However, a limited number of studies documenting the impact of social media on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) are available globally.

This study aimed to explore the perceived social media needs and their impact on the quality of life among the adult population of various selected countries.

Methodology

A cross-sectional, quantitative design and analytical study utilized an online survey disseminated from November to December 2021.

A total of 6689 respondents from ten countries participated in the study. The largest number of respondents was from Malaysia (23.9%), followed by Bangladesh (15.5%), Georgia (14.8%), and Turkey (12.2%). The prevalence of social media users was over 90% in Austria, Georgia, Myanmar, Nigeria, and the Philippines. The majority of social media users were from the 18–24 age group. Multiple regression analysis showed that higher education level was positively correlated with all four domains of WHOQoL. In addition, the psychological health domain of quality of life was positively associated in all countries. Predictors among Social Media Needs, Affective Needs (β = -0.07), and Social Integrative Needs (β = 0.09) were significantly associated with psychological health.

The study illuminates the positive correlation between higher education levels and improved life quality among social media users, highlighting an opportunity for policymakers to craft education-focused initiatives that enhance well-being. The findings call for strategic interventions to safeguard the mental health of the global social media populace, particularly those at educational and health disadvantages.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The development of internet technology has revolutionized the way people live. As a result, social media has become an integral part of daily life. It is hard to find a person who has internet access but does not use social media. Carr and Hayes [ 1 ] defined social media as “Internet-based channels that allow users to interact and selectively self-present opportunistically, either in real-time or asynchronously, with both broad and narrow audiences who derive value from user-generated content and the perception of interaction with others”. Examples of widely used social media platforms include Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, WhatsApp, and other apps that enable online social interaction. Over time, the use of social media has increased significantly, primarily for obtaining information, conducting research, creating a social image, interacting with the wider community, and expressing emotions with each other [ 2 ].

Furthermore, communities rely heavily on social media as it can change their perception and behaviour according to the information they receive via social media; also, they spend much time using it [ 3 ]. On average, users spend worldwide 2.24 hrs per day on social media, 30 min more than in 2015 [ 4 ]. In January 2021, 4.2 billion people were using social media globally, which is expected to reach six billion by 2027 [ 4 ].

A new paradigm of social interaction has evolved with the arrival of social media. It brought both positive and negative effects on human life. In one aspect, it provided an opportunity to connect with distant and diverse community/family relatives and information sources, allowing close and frequent interaction and an opportunity in helping to solve each other’s emotional and other daily life challenges [ 5 , 6 ]. Some studies report an increment in quality of life, and some reported no significant improvement [ 7 , 8 , 9 ].

The global assimilation of social media into everyday life has ushered in a complex array of impacts on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), exhibiting profound diversity across various cultures and demographics. This variation necessitates a collaborative international policy approach that both recognizes and respects these differences, enabling targeted strategies to mitigate the risks and amplify the benefits of social media on a global scale. It is essential to foster research that highlights cultural nuances to optimize social media’s role in enhancing QoL universally. A study conducted among adolescents in the Netherlands reported decreased HRQoL with the longer use of social media [ 10 ]. Particularly, the excessive or inappropriate use of social media is reported to cause more anxiety-like mental health-related problems (stress, anxiety and depression) than minimizing it [ 11 , 12 ]. The literature has determined that it has affected people’s regular work routine, well-being, happiness and mental health [ 13 , 14 ]. Furthermore, Oberst et al., 2017, stated that there is a higher potential for using social media among people already suffering from depression and anxiety-like mental illnesses [ 15 ]. Additionally, increased mental health-related problems have been linked to higher social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 16 ]. The concept of digital well-being was widely discussed during the pandemic, as social media was a major source of information [ 17 ].

A recent meta-analysis found insufficient evidence confirming the relationship between well-being and problematic use of social media [ 12 , 18 ]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital health literacy was crucial and linked to improved vaccine confidence and uptake [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. However, beyond digital health literacy, social media usage has certainly impacted the QoL [ 20 ]. Rodriguez et al. [ 23 ] concluded that the impact of social media differs based on the social media user’s demographic, personality and cultural variances. In addressing this analytical gap, the current research aims to delineate the specific social media needs and their consequential effects on life quality within an international context. Thus, the finding of one location may not accurately reflect the situation of different places of people sufficiently. Despite several studies outlining the negative impact of COVID-19 on health and QoL [ 24 , 25 , 26 ], limited evidence is available to examine the impact of social media use on quality of life. There have been only a few global studies documenting the impact of social media on HRQoL. The social media usage has become a pervasive element of human interaction. The handling of social media or the Internet affects the physical, mental, and spiritual health of the people and as such the QoL [ 7 , 9 , 27 , 28 ]. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the perceived social media needs and their impact on the QoL among the adult population of various selected countries. Our research introduces novel insights by providing a multi-country analysis that contrasts the effect of social media on QoL in varied cultural contexts, offering a granular understanding of its role across diverse global populations. It is the first of its kind to employ a comparative cross-national approach to examine the interplay between social media needs and life quality post the COVID-19 pandemic, filling a critical gap in existing literature.

Materials and methods

A quantitative-based cross-sectional study was conducted in the countries Austria, Bangladesh, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Philippines, Turkey from November 2021 to December 2021. The inclusion criteria for this study were citizens residing in the involved countries, aged 18 years and above, reachable via phone or over the internet, using a network connection, and willing to participate in this study.

The study sample size was calculated using an adjusted single population proportion formula with an additional 30% of the non-response rate, giving rise to the final sample size, n = 490. Non-probability convenience sampling will be used for sample collection.

This study used an online questionnaire available in both in their native language and English versions. In addition, three experts did the back-to-back translation. The questionnaire was adapted from validated sources: WHO Quality of Life-BREF [ 29 ] and the Social Networking Sites Uses and Needs questionnaire [ 2 ]. The online questionnaire consists of 4 sections and a total of 65 items. Section A: Sociodemographic profile (10 items), Section B: Social Networking Sites Usage and Needs (SNSUN) (27 items) and Section C: Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) (26 items). The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire consists of 26 instruments, of which 24 items are differentiated into four domains, namely physical health (seven items), psychological health (six items), social relationships (three items) and environment (eight items). The WHOQOL-BREF has shown good discriminant validity, content validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability [ 29 ]. The reliability of Physical health domain, psychological health, social relationship and environment were 0.71–0.79, 0.70–0.74, 0.80–0.87 and 0.81–0.89, respectively. The cut-off point for a predictor of overall good QoL of the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire is set to be > 60 to maintain sensitivity and positive predictive value [ 30 ].

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 for windows was used to analyze the data. The continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were expressed as proportions and frequencies. Bivariate analyses were performed to identify the possible significant factors for the four domains of the WHOQoL scale. An independent sample t-test was performed for two group comparisons. Linear regression was performed to determine the factors associated with the four domains of the WHOQoL scale. A p -value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all the analyses.

A total of 6689 respondents from ten countries participated in the study. The largest number of respondents was from Malaysia (23.9%), followed by Bangladesh (15.5%), Georgia (14.8%), and Turkey (12.2%). The least respondents were from Myanmar (1.2%) and Nigeria (1.8%). Among the subjects, the majority (35.3%) were in the age group between 18 and 24, followed by 25–44 (27.5%). More than half of the respondents were female (51.5%). Around 47% were married, and 45% were single. Maximum (44.7%) respondents were tertiary level education, and most of their income sources were work (46%). Over half were employed (51.5%), and around 40% were not employed. The living arrangements for 81% of respondents were with family, and more than three quarters of the respondents were residing in an urban area. Around 19.4% were living with an illness (Table 1 ).

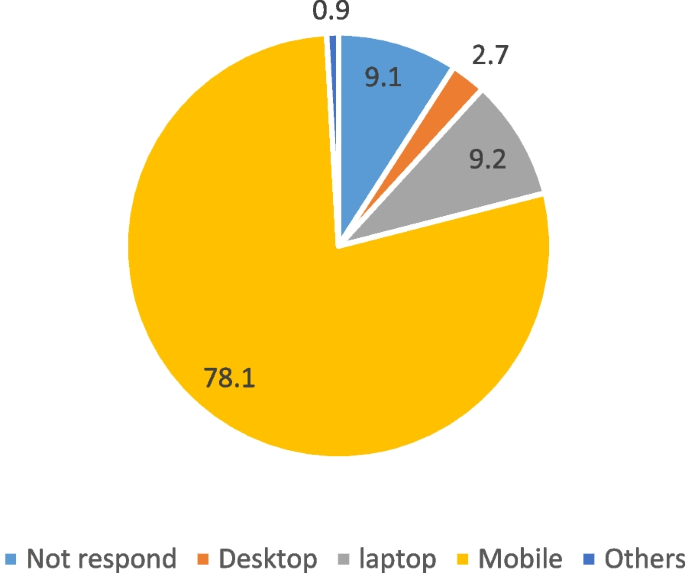

Table 2 demonstrates the prevalence of social media users. Age group, gender, marital status, highest qualification, Income source, employment status, living arrangements, residential area, and health condition were statistically significant with social media use. The prevalence of social media users was over 90% in Austria, Georgia, Myanmar, Nigeria, and the Philippines. The age-wise majority of uses of social media was higher in the age group 18–24. However, social media services among males were higher (91.8%) than for females (90%). Marital status as a ‘single’ was more prevalent (97%), and tertiary education (95.6%) reported a higher social media use. In addition, the prevalence was higher (97.3%) among respondents who are financially dependent on the parents. Also, employed respondents had a higher prevalence (94.5%) of social media use compared to unemployed (88.00). Respondents with living arrangements with family also reported higher use of social media. Likewise, those staying in the urban area, and those without illnesses (93%), had a higher prevalence of social media use. About 388 respondents’ did not report their income source, residential area, and health condition. Figure 1 represents the device that prefers to use social media. Most respondents used mobile devices (78.1%), followed by laptops or notebooks (9.2%) for social media use.

Device prefer to use social media

Table 3 shows the frequency of selected social networking sites. Over half (52%) of the participants used Facebook daily, while only 8.1% used Twitter. WhatsApp was used by 44.8% every day. More than one-third (37.4%) of the respondents used Instagram daily, 44.8 % used YouTube daily, and 35.3% of participants Google every day.

Table 4 presents perceived social media needs and QoL among participants. The mean score of social media needs were 8.0 (3.15), 11.31 (4.32), 7.1 (3.09), 9.4 (3.98), and 14.39 (5.22) for the diversions, cognitive needs, affective needs, personal integrative and integrative social needs respectively. Almost 39.8 and 43.2 percent of the participants self-reported poor QoL and poor health satisfaction (a score less than four is considered a poor QoL and poor health satisfaction). The mean score of the perceived QoL for domains was 61.38 (15.73), 59.36 (16.98), 57.93 (24.15), and 60.3 (18.72) for the physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environments domain, respectively.

Table 5 presents the relationship between social media needs and QoL by country. The average physical QoL was the highest in Nigeria (68.55 ± 13.24) and lowest in Austria (55.31 ± 10.24). Similarly, psychological QoL was also higher in Nigeria (69.24 ± 13.46) and lowest in Austria (51.04 ± 10.15). Social relationship QoL was higher in Austria (73.47 ± 18.49) and lowest in Iran (53.65 ± 23.99). Furthermore, the environment QoL was highest in Nigeria (69.2 ± 15.87) and the lowest in Iran (54.2 ± 20.13).

Those who used social media for diversion were statistically significant in all three QoL domains. In addition, they were significantly associated with physical, psychological, and social QoL. Those who used social media for cognitive needs were significantly associated with the physical, psychological, and environmental domains of QoL compared with those who did not use it. Those who used social media for affective needs were statistically significant for social and environmental QoL. Social media used for personal integrative or to enhance credibility and status were statistically significant in the social relationship domain of QoL ( p = 0.001) and environmental QoL ( p < 0.001). However, social media needs for social integrative needs or interaction with friends and family were statistically significant in three domains physical ( p < 0.001), psychological (< 0.001), and social relationship ( p = 0.022).

In the multiple regression analysis (Table 6 ), all the determinants were included together, where the dependent variable was all four domains of QoL. All countries were positively associated with the physical and psychological health domain. Similarly, all countries except Malaysia and Nigeria were not significantly associated with the environmental QoL.

Secondary (β = 0.08) and tertiary educated respondents (β = 0.125), whose work was ‘business’ (β = 0.02) were not significantly associated with the physical health psychological health, social relationship, and environmental QoL. Living with family (β = 0.04), and ‘other’ living arrangements (β = 0.047) were positively associated with physical health domain of QoL. However, living in care centres (β = -0.041) and having an illness (β = -0.09) were negatively related to physical health quality. Social media needs for affective needs (β = -0.073) and social integrative needs (β = 0.07) were significantly associated with the physical health domain of QoL.

The psychological health domain of QoL was positively associated in all countries. Sociodemographic predictors for psychological health domain of QoL showed that male gender (β = 0.03), primary (β = 0.07), secondary (β = 0.16), postsecondary (β = 0.16), and tertiary level of education (β = 0.19) were positively associated. In addition, those working in ‘business’ (β = 0.03), and whose parents were working (β = 0.07) and doing ‘other’ work (β = 0.03), living with ‘others’ (β = 0.05) were positively associated with the psychological health domain of QoL.

Those who are not employed (β = -0.04) and retired (β = -0.03), or reported to live in care centres (β = -0.05), had an illness (β = -0.14), showed a negative association with the psychological health domain of QoL.

Predictors among social media needs, Affective Needs (β = -0.07), and Social Integrative Needs (β = 0.09) were significantly associated with psychological health. All participating countries were negatively associated with social relationships. The social relationship is positively associated with age (β = -0.07), secondary education level (β = -0.10), Postsecondary (β = 0.11) and tertiary level education (β = 0.149), and parents were working (β = 0.04), Living with ‘Others’ (β = 0.04), and having an illness (β = -0.11). Affective needs for social media (β = -0.07) were negatively associated with the social relationship domain of QoL. However, Social Integrative Needs (β = 0.065) were positively related to social relationships. Age (β = 0.05), male gender (β = 0.03), primary (β = 0.06), secondary (β = 0.15), postsecondary (β = 0.16), and tertiary (β = 0.207) level of education, working in business (β = 0.03), Working parents(β = 0.05), retirement status(β = -0.03), Living with ‘Others’(β = 0.05), living in care centres (β = -0.05), having illness (β = -0.128) were positively associated with environment QoL. However, among social media needs, affective Needs (β = -0.07) were negatively related to the environmental health domain of QoL, and integrative social needs (β = 0.08) were positively associated with environment.

Our world today is undeniably digital. Social media has become the go-to guide for over 61.4 percent of the global population. Despite the widespread use of social media among people of all ages, limited studies have explored the impact of social media on the overall quality of life (QoL) of populations [ 7 , 9 , 27 , 28 ]. Specifically, this study sought to fill this gap by assessing the perceived social media needs and QoL among the adult population across ten countries.

For country statistics, our study findings showed that the percentage of social media users was highest in regions of Southeast Asia (Myanmar, Philippines), Southern Europe (Austria), West Asia (Georgia) and West Africa (Nigeria), whereas the lowest number of social media users was reported in the Middle East (Iran, Iraq). These results were aligned with the Global Social Media Research Summary 2021/2022, which ranked Southeast Asia - sixth, Southern Europe - seventh, and West Asia – ninth for the highest social network penetration rate [ 31 ].

In terms of sociodemographic, among 6689 participants recruited in this study, over one-third were young adults ranged from 18–24 years. According to previous studies conducted in United States in 2015, the mean age of respondents was 28.8 years old, suggesting the usage of social media among working age group [ 32 ]. As compared to our study conducted in 2021, is seen increasing trend for young adults’ social media users. Similarly, the in Global Social Media Research Summary 2021/2022 found that Generation Z aged 10–25 showed an increasing trend in social media use [ 31 ]. Generation X and Millennials aged 26–57 showed a decreasing trend in social media usage due to increasing real-life responsibilities and an increasing trend for the Boomer generation as social media allows connection and communication with the younger generation [ 31 ]. A systematic review conducted on social media sites and older users also shows the ability for intergenerational communication is the main driving factor for the elderly to use social media sites [ 33 ]. This study also found that social media usage was slightly higher in males than females. Consistent with the Global Social Media Research Summary 2021/2022, male users predominate social media usage across all age ranges except those aged 45 years and above [ 31 ].

Interestingly, our study findings suggested that the most used social media platforms were Facebook and its associate media sites, WhatsApp, and Instagram, which are under the parent company - Meta. These findings were consistent with the Global Social Media Research Summary 2021/2022, indicating that Facebook was the most visited social media platform, predominantly visited by those aged 58 years and above [ 31 ]. Google was ranked the first most visited website worldwide, and its subsidiary company YouTube remains the top video-sharing site. YouTube and Instagram are mostly visited by those ages 18–24 at 89% and 74%, respectively. Contrary to the Global Social Media Research Summary 2021/2022, Twitter was the second most used social media platform compared to our study that showed Twitter had the least usage [ 31 ].

Country-wise QOL assessment, this study found that the mean scores for perceived QOL were lower in all domains compared to Portugal [ 34 ]; lower in psychological health and social relationship domains compared to Brazil [ 35 ] and higher for physical and environmental health domains than Brazil and Malawi [ 35 , 36 ]. Despite our study deduced that Nigerians perceived higher QOL than Malaysian and Turkish people in all domains, Skevington et al. found contradictory findings [ 37 ]. Except the social health domain was in line with our study, the mean score for the physical health domain was higher in Malaysia than in Nigeria and Turkey. Similarly, the mean score for the psychological health domain in Malaysia and Nigeria were equally higher than in Turkey. Furthermore, they also revealed that environmental health domain scores were higher in Malaysia than in Turkey and Nigeria [ 37 ]. However, it is noteworthy that these comparisons are interpreted with due caution as a previous study showed that physical and psychological domains of WHOQOL-BREF were less invariant than social relationship and environmental domains. Only 11 out of 24 facet items, excluding four facets that were fixed as reference items for which their invariance could not be assessed, were found to have invariant factor loadings and thresholds in the study mentioned above [ 38 ]. Alarming as it may sound, meaningful comparisons still can be made, provided that the proportion of non-invariant items is rather small [ 38 ].

Multiple regression analysis of sociodemographic backgrounds and four domains of WHOQOL index value showed that higher education level was positively correlated with all four domains of WHOQOL-BREF. Likewise, previous studies also reported that education level was significantly associated with physical, psychological, social relationship and environment health domain [ 34 , 35 , 39 ]. In our study, living with family and others led to better physical health scores than living alone. These findings were consistent with a previous study conducted by Patrício et al. in 2014, suggesting that living with parents, partners, or children could result in better physical health [ 34 ]. Contrary, existing literature proved unequivocally that living alone was linked deleteriously to a rise in blood pressure, poorer sleep quality, detrimental effects on immune stress response and deterioration in cognition levels over time in the elderly, which can ultimately jeopardize overall physical health [ 40 ].

In line with previous studies, gender was also determined as one of the predictors for the psychological health domain in our study, in which males were found to have better QoL than females [ 31 , 35 , 41 ]. However, controversial results were also found in some studies, ascertained that gender was not correlated with psychological health [ 39 , 42 ]. Our findings could be attributed to women’s multiple social burdens of being wives, mothers or carers, single parents or widows and the effects of their vulnerability to domestic and sexual violence [ 43 ]. Another study on older women living in low, densely populated areas in the central southern region of Portugal also shows that they are susceptible to ageing and exhibit a greater dependency on their loved ones, making them vulnerable to psychological and physical health [ 44 ].

Our study also revealed that employment status is related to psychological health, in which employed individuals had better psychological health than those who were unemployed. Similar findings were found in two studies which suggested that employment influences the QoL of the general population [ 31 , 34 ]. However, existing literature also argues that retired individuals have better psychological health than employed individuals, mainly due to workplace violence experience, poor psychosocial job quality and low job control [ 45 , 46 ]. Meanwhile, a possible explanation for our finding is that unemployment leads to the deprivation of several latent functions of employment, such as financial strain, social contacts, time structure and personal status or identity in institutions, which are also fundamental psychological needs that are important for mental health [ 47 ]. Moreover, prolonged uncertainty, self-doubt and anxiety among those unemployed also lead to a further decrement in psychological health.

In addition, our study also found that living with illness and in care centres were negatively correlated with psychological health. This finding is in accordance with a previous study conducted by Ghasemi et al. [ 48 ], suggested that older adults who prefer to live with their families could have better QoL. However, in contrast, Chung found that community-dwelling elderly had 3.14 higher odds of depression compared to nursing home elderly [ 49 ]. Nevertheless, poor psychological health among those living in residential homes could be due to the loss of freedom, social status, autonomy and self-esteem, neglect from children and approaching death [ 50 ]. As for people with illnesses, similar to our findings, numerous literatures have suggested that living with illness can affect moods, emotions, behaviour of a person, and eventually leading to poorer mental health [ 31 , 34 , 35 , 39 ].

Other than that, there was a positive association between age and environment QoL. Previous study supported the idea that personal and national ageing encourages individual pro-environmental behaviour [ 51 ], which is consistent with the theory of generativity. As people age, they may increasingly seek self-transcendence and meaning in life and pursue pro-social goals, and the practice of environmentally friendly actions may become one way for older persons to impart such wisdom. Besides, older people may become more involved in environmental issues due to their enhanced perceived effects of environmental risks on human health [ 51 ]. Furthermore, our findings on the positive association between education and environmental health was supported by another study, which suggested that decreasing the number of secondary school dropouts might increase pro-environmental behaviour [ 52 ]. The possible reason was that additional education explicitly teaches people the value of the environment [ 52 ].

As for social media needs, our study revealed that affective and social integrative needs were significantly associated with the physical health domain of QoL. According to previous research, people who actively engage in online social networks were more likely to be socially active by having online interactions and new friends. This may have favourable effects on their physical well-being [ 53 ]. Controversially, previous literature also found strong feelings of dependency on Facebook was correlated with poorer physical health [ 54 ].

Moreover, our study revealed that affective and social integrative needs were significantly associated with psychological health. In fact, it is known that humans genetically have a strong desire to connect with people, especially to share their feelings. By utilizing social media, users who enjoy virtual connections would gain many advantages, which could potentially affect their emotional well-being and psychological health [ 55 ]. In line with our study, previous research revealed a positive correlation between online social media use for interaction and psychological health [ 56 ]. Indeed, social media can provide opportunities to engage and support individuals with mental health issues [ 57 ]. Contrary, a systematic review of 16 studies found a negative association between social integrative needs and psychological health. It found that some teens had anxiety from social media due to fear of missing out, and they would regularly check all their friends’ messages [ 58 ]. In addition, a recent study revealed that taking a 1-week break from using social media can substantially improve well-being, depression, and anxiety [ 59 ].

Interestingly, for social relationship domain of QoL, our study findings suggested that it has a negative correlation with affective needs, whereas a positive association with social integrative needs. This might be due to social media use for affective needs often produces unrealistic expectations as people may compare their physical and virtual relationships [ 60 ]. Another possible reason was that certain characteristics of social media users like social isolation might influence real-life social relationship quality. However, particularly for students with introvert personality, they were more likely to communicate online as online chatting is more comfortable for them [ 61 ]. In addition, our finding could be attributable to the benefit of relational reconnection from social media, in which social media use can improve social connectedness especially during COVID-19 lockdowns [ 62 , 63 ]. Preventive measures and practices towards COVID-19 have restrained physical contacts and meetings, which highlighted the crucial need for social media platform in communication [ 64 ]. In fact, social media has been the platform for promoting health and disseminating health information globally during the pandemic [ 20 , 28 ]. Infectious diseases will continue to emerge and re-emerge, leading to unpredictable epidemics and difficult challenges to public health [ 65 , 66 ]. As going digital is indispensable, this underscores the importance of social media in daily needs fulfillment to enable better well-being and QoL.

Furthermore, the impact of social media use on physical, psychological, and social QoL was found to be statistically significant when used for diversion, aligning with earlier findings that problematic use of social networking sites correlates with attempts to alleviate boredom [ 67 ]. Studies have also linked problematic use of social media with poor psychological health outcomes [ 68 ], depression [ 69 ], and anxiety [ 70 ]. The biopsychosocial paradigm—encompassing withdrawal, conflict, tolerance, salience, mood modification, and relapse—provides a framework for understanding problematic social media use [ 71 ]. Social media, when used to alter mood or escape problems, can lead to addictive behaviors. The obsession with social media, reflected in its salience, may contribute to sedentary habits and lower levels of physical activity, which increase the risk of non-communicable diseases [ 72 ]. Additionally, excessive use can lead to irritability in the absence of social media, potentially harming social interactions [ 60 ]. It is imperative for government policies to target the resultant sedentary lifestyles and mental health issues arising from social media use. Moreover, the promulgation of such policies via social media channels is advisable to ensure broad dissemination and enhance the efficacy of government-public communication [ 73 ].

Strengths and limitations

The study leverages a large and culturally diverse sample from 10 countries, enhancing the understanding of social media’s effects on QoL on an international scale. The use of well-validated instruments, the WHOQOL-BREF and SNSUN scales, adds rigor to the research outcomes. It also thoughtfully considers the influence of education on QoL, providing nuanced insights into the social implications of social media use. The study is, however, limited by a convenience sampling method that may not be representative of the global population, potentially biasing the results. Unequal sample sizes across countries pose a challenge for valid cross-cultural comparisons and understanding the differential impact of social media. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to track changes over time or establish causality. Recommendations for future research include adopting probability sampling methods to improve representativeness and balance. Ensuring equal sample distribution across participating countries will enhance the validity of international comparisons. Longitudinal studies are suggested to better understand the causal relationships between social media use and QoL over extended periods.

Conclusions

Social media usage has become a pervasive part of individuals interaction. Intensive handling and interaction affect the physical, mental, and spiritual health of the people and as such the QoL. This study aimed to explore the perceived social media needs and their impact on the QoL among the adult population of various selected countries. A significant proportion of the survey population reported poor QoL and poor health satisfaction. Physical and psychological QoL was poor among Austrian people, whereas social relationship QoL was higher in Austria. Furthermore, social relationship QoL and environmental QoL was lower among the Iranian population, and this can be tackled by disseminating appropriate policy interventions. Those with illness reported poor physical health quality and it is important to adopt a holistic approach to tackle the problems of those already battling with illness. Finally, higher education acts as a safety net against psychological health; therefore, uneducated or low educated need intrinsic focus to tackle the menace of psychological health. As to what they can do to resolve the issue of low physical and psychological QoL. The significance of these findings lies in their ability to support additional study on social media, mental health and physical and psychological QoL. This finding may interest policymakers to address this topic to public health, in higher boards, companies, and educational sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Carr CT, Hayes RA. Social media: defining, developing, and divining. Atl J Commun. 2015;23(1):46–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2015.972282 .

Article Google Scholar

Ali I, Danaee M, Firdaus A. Social networking sites usage & needs scale (SNSUN): a new instrument for measuring social networking sites’ usage patterns and needs. J Inf Telecommun. 2020;4(2):151–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/24751839.2019.1675461 .

Brailovskaia J, Margraf J, Schneider S. Social media as source of information, stress symptoms, and burden caused by Coronavirus (COVID-19). Eur Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000452 .

Statista. Number of worldwide social network users 2027. 2023. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ . Cited 2023 Feb 1.

Naslund JA, Bondre A, Torous J, Aschbrenner KA. Social media and mental health: benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;5:245–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00134-x .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wang JL, Jackson LA, Gaskin J, Wang HZ. The effects of Social Networking Site (SNS) use on college students’ friendship and well-being. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;37:229–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.051 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Collis A, Eggers F. Effects of restricting social media usage on wellbeing and performance: a randomized control trial among students. PLoS One. 2022;17(8 August):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272416 .

von Lieres JS, Cauvery G. The impact of social media use on young adults’ quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic in south India. 2022. p. 318–24. https://doi.org/10.1109/ghtc55712.2022.9910989 .

Saini N, Sangwan G, Verma M, Kohli A, Kaur M, Lakshmi PVM. Effect of social networking sites on the quality of life of college students: a cross-sectional study from a city in North India. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8576023 .

You Y, Yang-Huang J, Raat H, Van Grieken A. Social media use and health-related quality of life among adolescents: cross-sectional study. JMIR Ment Health. 2022;9(10):e39710. https://doi.org/10.2196/39710 . https://mental.jmir.org/2022/10/e39710 .

Boursier V, Gioia F, Musetti A, Schimmenti A. Facing loneliness and anxiety during the COVID-19 isolation: the role of excessive social media use in a sample of Italian adults. Front Psych. 2020;11:586222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586222 .

Shannon H, Bush K, Villeneuve PJ, Hellemans KGC, Guimond S. Problematic social media use in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health. 2022;9(4). https://doi.org/10.2196/preprints.33450 . https://doi.org/10.2196/33450 .

Abi-Jaoude E, Naylor KT, Pignatiello A. Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health. CMAJ. 2020;192(6):E136–41. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190434 .

Brooks S. Does personal social media usage affect efficiency and well-being? Comput Hum Behav. 2015;46:26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.053 .

Oberst U, Wegmann E, Stodt B, Brand M, Chamarro A. Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: the mediating role of fear of missing out. J Adolesc. 2017;55:51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.008 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, Chen S, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bhattacharya S, Bhattacharya S, Vallabh V, Marzo RR, Juyal R, Gokdemir O. Digital Well-being Through the Use of Technology–A Perspective. Int J Matern Child Health AIDS. 2023;12(1):e588. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.588 .

Huang C. A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(1):12–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020978434 .

Alhassan RK, Aberese-Ako M, Doegah PT, Immurana M, Dalaba MA, Manyeh AK, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among the adult population in Ghana: evidence from a pre-vaccination rollout survey. Trop Med Health. 2021;49(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-021-00357-5 .

Marzo RR, Chen HWJ, Abid K, Chauhan S, Kaggwa MM, Essar MY, et al. Adapted digital health literacy and health information seeking behavior among lower income groups in Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022;10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.998272 . Cited 2022 Sep 26.

Marzo RR, Shrestha R, Sapkota B, Acharya S, Shrestha N, Pokharel M, et al. Perception towards vaccine effectiveness in controlling COVID-19 spread in rural and urban communities: a global survey. Front Public Health. 2022;10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.958668 . Cited 2023 Feb 1.

Marzo RR, Su TT, Ismail R, Htay MNN, Essar MY, Chauhan S, et al. Digital health literacy for COVID-19 vaccination and intention to be immunized: a cross sectional multi-country study among the general adult population. Front Public Health. 2022;10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.998234 . Cited 2022 Sep 26.

Rodriguez M, Aalbers G, McNally RJ. Idiographic network models of social media use and depression symptoms. Cogn Ther Res. 2021:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10236-2 .

Hwaij RA, Ghrayeb F, Marzo RR, AlRifai A. Palestinian healthcare workers mental health challenges during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Med Res Arch. 2022;10(10). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v10i10.3125 .

Marzo RR, ElSherif M, Abdullah MSAMB, Thew HZ, Chong C, Soh SY, et al. Demographic and work-related factors associated with burnout, resilience, and quality of life among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional study from Malaysia. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1021495. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1021495 .

Marzo RR, Khaled Y, ElSherif M, Abdullah MSAMB, Thew HZ, Chong C, et al. Burnout, resilience and the quality of life among Malaysian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1021497. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1021497 .

von Lieres JS, Cauvery G. The impact of social media use on young adults’ quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic in South India. In: 2022 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC). IEEE; 2022. p. 318–24. https://doi.org/10.1109/ghtc55712.2022.9910989 .

Chen HWJ, Marzo RR, Sapa NH, Ahmad A, Anuar H, Baobaid MF, et al. Trends in health communication: social media needs and quality of life among older adults in Malaysia. Healthcare. 2023;11:1455. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101455 .

WHOQoL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291798006667 .

Silva PAB, Soares SM, Santos JFG, Silva LB. Cut-off point for WHOQOL-bref as a measure of quality of life of older adults. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48:390–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-8910.2014048004912 .

Bouchrika I. Global social media research summary: 2023 penetration & impact. 2022. Available from: https://research.com/education/global-social-media-research . Cited 2023 Feb 1.

Campisi J, Folan D, Diehl G, Kable T, Rademeyer C. Social media users have different experiences, motivations, and quality of life. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(3):774–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.042 .

Nef T, Ganea RL, Müri RM, Mosimann UP. Social networking sites and older users–a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(7):1041–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610213000355 .

Patrício B, Jesus LMT, Cruice M, Hall A. Quality of life predictors and normative data. Soc Indic Res. 2014;119(3):1557–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0559-5 .

Cruz LN, Polanczyk CA, Camey SA, Hoffmann JF, Fleck MP. Quality of life in Brazil: normative values for the WHOQOL-bref in a southern general population sample. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1123–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9845-3 .

Colbourn T, Masache G, Skordis-Worrall J. Development, reliability and validity of the Chichewa WHOQOL-BREF in adults in lilongwe, Malawi. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):346. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-346 .

Skevington SM. Qualities of life, educational level and human development: an international investigation of health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(10):999–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0138-x .

Theuns P, Hofmans J, Mazaheri M, Van Acker F, Bernheim JL. Cross-national comparability of the WHOQOL-BREF: a measurement invariance approach. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(2):219–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9577-9 .

Nedjat S, HolakouieNaieni K, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R, Montazeri A. Quality of life among an Iranian general population sample using the World Health Organization’s quality of life instrument (WHOQOL-BREF). Int J Public Health. 2011;56(1):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00650.x .

Luanaigh CÓ, Lawlor BA. Loneliness and the health of older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1213–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2054 .

Ohaeri JU, Awadalla AW, Gado OM. Subjective quality of life in a nationwide sample of Kuwaiti subjects using the short version of the WHO quality of life instrument. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol. 2009;44(8):693–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0131-4 .

Zorba E, Bayrakdar A, Gönülateş S, Sever O. Analysis of the level of life quality of university students. Online J Recreation Sports. 2017;6(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.22282/ojrs.2017.5 .

Roberts B, Browne J. A systematic review of factors influencing the psychological health of conflict-affected populations in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(8):814–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2010.511625 .

Goes M, Lopes M, Oliveira H, Fonseca C, João M. Quality-of-life profile of the elderly residing in a very low population density rural area. In: Review. 2019. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-7170/v1 . Cited 2023 Feb 1.

Lindwall M, Berg AI, Bjälkebring P, Buratti S, Hansson I, Hassing L, et al. Psychological health in the retirement transition: rationale and first findings in the HEalth, Ageing and Retirement Transitions in Sweden (HEARTS) study. Front Psychol. 2017;8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01634 . Cited 2023 Feb 1.

Shields M, Dimov S, Kavanagh A, Milner A, Spittal MJ, King TL. How do employment conditions and psychosocial workplace exposures impact the mental health of young workers? A systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(7):1147–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02077-x .

Zechmann A, Paul KI. Why do individuals suffer during unemployment? Analyzing the role of deprived psychological needs in a six-wave longitudinal study. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24:641–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000154.supp .

Ghasemi H, Harirchi M, Masnavi A, Rahgozar M, Akbarian M. Comparing quality of life between seniors living in families and institutionalized in nursing homes. Soc Welf Q. 2011;10(39):177–200. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/280727 .

Chung S. Residential status and depression among Korean elderly people: a comparison between residents of nursing home and those based in the community. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16(4):370–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00747.x .

Simeão SFDAP, Martins GADL, Gatti MAN, Conti MHSD, Vitta AD, Marta SN. Comparative study of quality of life of elderly nursing home residents and those attending a day Center. Cien Saude Colet. 2018;23(11):3923–34.

Wang Y, Hao F, Liu Y. Pro-environmental behavior in an aging world: evidence from 31 countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041748 .

Meyer A. Does education increase pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecol Econo. 2015;116:108–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.04.018 .

McCrae N, Gettings S, Purssell E. Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Adolesc Res Rev. 2017;2(4):315–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0053-4 .

Dibb B. Social media use and perceptions of physical health. Heliyon. 2019;5(1):e00989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00989 .

Graciyal DG, Viswam D. Social media and emotional well-being: pursuit of happiness or pleasure. Asia Pacif Media Educ. 2021;31(1):99–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1326365x211003737 .

Tobi SNM, Ma’on SN, Ghazali N. The use of online social networking and quality of life. In: 2013 international conference on technology, informatics, management, engineering and environment. 2013. p. 131–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/time-e.2013.6611978 .

Taylor-Jackson J, Moustafa AA. The relationships between social media use and factors relating to depression. In: The nature of depression. 2021. p. 171–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-817676-4.00010-9 .

Karim F, Oyewande AA, Abdalla LF, Ehsanullah RC, Khan S, Karim F, et al. Social media use and its connection to mental health: a systematic review. Cureus J Med Sci. 2020;12(6). Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/31508-social-media-use-and-its-connection-to-mental-health-a-systematic-review . Cited 2023 Feb 1.

Lambert J, Barnstable G, Minter E, Cooper J, McEwan D. Taking a one-week break from social media improves well-being, depression, and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2022;25(5):287–93. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0324 .

Christensen S. Social media use and its impact on relationships and emotions - ProQuest. Ann Arbor; 2018. Available from: https://www.proquest.com/openview/cb7d5ac2cd818724237760ce7e0a9ce2/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y . Cited 2023 Feb 1.

Bonetti L, Campbell MA, Gilmore L. The relationship of loneliness and social anxiety with children’s and adolescents’ online communication. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(3):279–85. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0215 .

Allen KA, Ryan T, Gray DL, McInerney DM, Waters L. Social media use and social connectedness in adolescents: the positives and the potential pitfalls. Educ Dev Psychol. 2014;31(1):18–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2014.2 .

Abdalqader M, Shebl H, Ghazi H, Baobaid MF, Wei Jun HC, Hasan TN, et al. The facts about Corona virus disease (COVID-19): the current scenario and important lessons. Glob J Public Health Med. 2020;2(SP1):168–78. https://doi.org/10.37557/gjphm.v2iSP1.48 .

Abdalqader M, Baobaid MF, Ghazi HF, Hasan TN, Mohammed MF, Abdalrazak HA, et al. The Malaysian Movement Control Order (MCO) impact and its relationship with practices towards Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among a private university students in Selangor. Malays J Public Health Med. 2020;20(2):49–55. https://doi.org/10.37268/mjphm/vol.20/no.2/art.523 .

Najimudeen M, Chen HWJ, Jamaluddin NA, Myint MH, Marzo RR. Monkeypox in pregnancy: susceptibility, maternal and fetal outcomes, and one health concept. Int J MCH AIDS. 2022;11(2):e594. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.594 .

Chen HWJ, Marzo RR, Tang HC, Mawazi SM, Essar MY. One mutation away, the potential zoonotic threat—neocov, planetary health impacts and the call for sustainability. J Public Health Res. 2022;10(1). https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2941 .

Stockdale LA, Coyne SM. Bored and online: reasons for using social media, problematic social networking site use, and behavioral outcomes across the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. J Adolesc. 2020;79:173–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.010 .

Huang C. Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2017;20(6):346–54. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0758 .

Twenge JM, Martin GN, Campbell WK. Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion. 2018;18:765–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000403.supp .

Elhai JD, Yang H, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. COVID-19 anxiety symptoms associated with problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese adults. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:576–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.080 .

Kırcaburun K, Griffiths MD. Problematic Instagram use: the role of perceived feeling of presence and escapism. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(4):909–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9895-7 .

Kolhar M, Kazi RNA, Alameen A. Effect of social media use on learning, social interactions, and sleep duration among university students. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(4):2216–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.01.010 .

Widayat RM, Aji JS, Kurniawan C. A systematic review of social media and government in the social science discipline. J Contemp Governance Public Policy. 2023;4(1):59–74. Available from: https://journal.ppishk.org/index.php/jcgpp/article/view/100 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study extend their appreciation to the Research Supporting Project, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this study (RSP-2024R481).

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Humanities and Health Sciences, Curtin University, Miri, Malaysia

Roy Rillera Marzo

Global Public Health, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Subang Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

International Medical School, Management and Science University, Shah Alam, Selangor, 40610, Malaysia

Hana W. Jun Chen

College of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry, Birsa Agricultural University, Ranchi, Jharkhand, 834006, India

Absar Ahmad

Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Hui Zhu Thew

Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia

Ja Shen Choy, Chee Han Ng & Chen Loong Alyx Chew

Institute International Trade and Sustainable Economy, University of Applied Sciences Krems, Krems an der Donau, Austria

Petra Heidler

Department of Health Sciences, St. Pölten University of Applied Sciences, St. Pölten, Austria

Department of Exercise Physiology, School of Health, University of the Sunshine Coast, Sippy Downs, QLD, Australia

Isabel King

Palliative Care and Chronic Disease, Green Pastures Hospital, PO Box 28, Pokhara, Province Gandaki, 33700, Nepal

Rajeev Shrestha

Department of Research & Administration, Bangladesh National Nutrition Council, Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Farzana Rahman

Department of Coordination, National Nutrition Council, Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Jehan Akhter Rana

Faculty of Healthcare Economics and Management, University Geomedi, Tbilisi, Georgia

Tornike Khoshtaria

School of Business, International Black Sea University, Tbilisi, Georgia

Arian Matin

School of Economics and Business, Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia

Nugzar Todua

Department of Medical Education and Informatics, Gazi University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey

Burcu Küçük Biçer

Pharmacy Department, School of Allied Health Sciences, San Pedro College, Davao City, Philippines

Erwin Faller

Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Bournemouth University, Poole, UK

Faculty of the College of Education, University of Southeastern Philippines, Davao City, Philippines

Randy A. Tudy

College of Nursing, Saint Alexius College, Koronadal City, Philippines

Aries Baldonado

Department of Psychology, College of Science, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Criselle Angeline Penamante

Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cyberjaya, Cyberjaya, Malaysia

Rafidah Bahari

Department of Medical Microbiology, College of Medicine, University of Duhok, Duhok, Iraq

Delan Ameen Younus

Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Technical Health and Medical College, Erbil Polytechnique University, Erbil, Iraq

Zjwan Mohammed Ismail

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran

Masoud Lotfizadeh

Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

Shehu Muhammad Hassan

Department of Public Health, Distance Learning Centre, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

Rahamatu Shamsiyyah Iliya

School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, UK

Asari E. Inyang

Asian Institute of Medicine, Science and Technology, Bedong, Kedah, Malaysia

Theingi Maung Maung

ASEAN Institute for Health Development, Mahidol University, Salaya, Thailand

Win Myint Oo

Regional Public Health Department, Ayeyarwady Region, Pathein, Myanmar

Ohnmar Myint

Department of Public Health Modern Technical College Affiliated to Pokhara University, Lalitpur, Nepal

Anil Khadka

Manmohan Cardiothoracic Vascular and Transplant Centre, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, 44600, Nepal

Swosti Acharya

Department of Paediatrics, RCSI Program Perdana University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Soe Soe Aye

Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cyberjaya, Cyberjaya, Malaysia

Thein Win Naing

Department of Internal Medicine, University of Cyberjaya, Cyberjaya, Malaysia

Myat Thida Win

Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, SEGi University, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia

Ye Wint Kyaw

Life Skill Education Institutes/Yeti Health Science Academy, Kathmandu, Nepal

Pramila Pudasaini Thapa

Department of Public Health (Purbanchal University), Kathmandu, Nepal

Josana Khanal

Department of Community and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Deoghar, Jharkhand, India

Sudip Bhattacharya

Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan

Khadijah Abid

Management Department, BINUS Online Learning, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, 11480, Indonesia

Mochammad Fahlevi

Department of Health Administration, College of Business Administration, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Mohammed Aljuaid

Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford Richard Doll Building, Old Road Campus, Oxford, OX3 7LF, UK

Radwa Abdullah El-Abasir

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy III, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany

Mohamed E. G. Elsayed

Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Carl von Ossietzky University Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the o the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Roy Rillera Marzo or Mohammed Aljuaid .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The protocol was approved from the Ethics Committee of Management and Science University. (Ref: EA-L1-01-IMS-2023-06-0003). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Consent for publication

All of the authors have read and approved this current version of the manuscript and its submission to your journal. None of the authors have any conflict of interest to declare. We confirm that the paper has not been submitted to any other journal for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Marzo, R.R., Jun Chen, H.W., Ahmad, A. et al. The evolving role of social media in enhancing quality of life: a global perspective across 10 countries. Arch Public Health 82 , 28 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01222-z

Download citation

Received : 18 August 2023

Accepted : 25 November 2023

Published : 06 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01222-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social media needs

- Quality of life

- Affective needs

- Epidemiology

- Determinants

Archives of Public Health

ISSN: 2049-3258

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Social media research: We are publishing more but with weak influence

Roles Methodology

Affiliation Department of Marketing, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Roles Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Business Administration, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, Jounieh, Lebanon

- Samer Elhajjar,

- Laurent Yacoub

- Published: February 8, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297241

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The purpose of this paper is to address the chasm between academic research on social media as an expanding academic discipline and at the same time a growing marketing function. A bibliometric analysis indicated the evolution of academic research on social media. The results of a survey of 280 social media practitioners shed the light on the gap between academic social media research and the practice of professionals. A qualitative study also offered novel insights and recommendations for future developments in academic research on social media. The findings of this paper showed that academic research on social media is growing in terms of the number of publications but is struggling in three areas: visibility, relevance, and influence on practitioners. This study contributes to the body of knowledge on social media. The implications of our study are derived from the importance of our findings on the directions to publish more relevant and timely academic research on social media. While extensive studies exist on social media, their influence on practitioners is still limited.

Citation: Elhajjar S, Yacoub L (2024) Social media research: We are publishing more but with weak influence. PLoS ONE 19(2): e0297241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297241

Editor: Alhamzah F. Abbas, UTM Skudai: Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, MALAYSIA

Received: July 27, 2023; Accepted: January 1, 2024; Published: February 8, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Elhajjar, Yacoub. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files. The data underlying the results presented in the study are from Scopus ( http://www.scopus.com/ ).

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In the early 1960s, academics began to advocate that marketing should gain rigor by relying on a scientific approach that respects requirements in terms of the state of knowledge, the hypotheses development, the methodology, and the analysis and interpretation of results [ 1 – 5 ]. This traditional conception of rigor has, over the years, fuelled the need to acquire tools to better evaluate, recognise and promote it. Thus, first in the United States, and now in almost all countries, various stakeholders use rankings of scientific journals, mainly Anglo-Saxon, which often consider their impact factors according to the Journal Citation Report (JCR) of the Science Citation Index or the Social Science Citation Index. Quality accreditation bodies for higher education management institutions have also followed suit by offering journal ranking lists.

However, since the early 1980s, the debate between rigor and relevance in the production and dissemination of marketing knowledge has been prominent in the literature. There is a serious concern about how academics are evaluating the impact of their research. As if the focus of marketing researchers is to improve their citation records rather than developing practical implications for practitioners. Shouldn’t marketing scholarship, when applied to practical issues, aim to harmonize rigor and relevance right from the start? How did we arrive at this risk of divorce and the need to reconcile thoroughness and applicability?

In fact, in some fields, such as pharmacy, where breakthroughs in medical procedures and the discovery of new pharmaceuticals result in societal benefits, the influence of research is simple to grasp. This effect is more difficult to detect in social media. In the discipline of marketing, for example, there have been allegations that research has strayed too far from the interests of practitioners. In turn, researchers point out the flaws in present professional methods [ 6 ]. Indeed, some in the marketing research community believe that many practical concerns that worry professional marketers are unworthy of researchers’ attention. This is mainly because of a long-standing misguidance of business schools [ 7 ] since their research is less and less influential [ 8 – 11 ]. Several studies confirm that the impact of academic research on business practices has been disappointing and that innovations have come from the consulting community, the business press, and professional associations [ 12 – 15 ].

This article aimed to identify whether there is a gap between rigor and relevance in academic research on social media. It also proposed ways for marketing researchers to foster relevance. In general, this article responded to two research questions: Is there a chasm between academic social media research and social media practitioners? How to reconcile the rigor and relevance of social media research?

The originality of this research lies in its specific focus on bridging the potential gap between rigor and relevance within the realm of academic research on social media. While social media has become an integral part of contemporary society and communication [ 16 ], there is a growing concern that academic investigations in this domain may sometimes prioritize theoretical rigor at the expense of practical applicability [ 17 ]. By addressing this issue, the research seeks to contribute significantly to the field by shedding light on the balance between rigorous methodologies and the real-world applicability of social media research findings. This unique perspective not only emphasizes the importance of ensuring academic work remains pertinent and useful in a rapidly evolving digital landscape but also offers valuable insights for researchers, educators, and policymakers striving to navigate the intricate intersection of academia and social media’s dynamic environment.

To answer our research questions, the paper was structured as follows. First, we examined the theoretical foundations of academic marketing research. Second, the research design and methodology of our three investigations were then described. Our first study involved a social media research bibliometric analysis with the goal of describing the evolution and development of academic social media research. Our second study gathered feedback and information from social media practitioners. Our third study listed suggestions for academic researchers. The three studies worked in tandem to create a comprehensive picture of academic research on social media. They offered historical context, practical insights, and actionable recommendations, collectively contributing to a holistic understanding of how researchers can bridge the gap between rigor and relevance in the dynamic realm of social media. Lastly, we listed the contributions of our study and their implications for future research.

Literature review

Academic marketing research has two purposes: first, to advance marketing theory, and second, to improve marketing practice [ 18 ]. On the one hand, theory ought to give academics fresh ideas, conceptual frameworks, and resources to aid in their understanding of marketing phenomena. On the other side, research should give marketers direction for making better decisions. As a result, marketing academics should address issues with the development of marketing theory’s rigor and its applicability to marketing practice [ 19 ]. Nevertheless, leading academic voices have expressed worry about the gap between marketing theory and practice. Reibstein et al. [ 20 ], for example, have questioned if marketing academia has lost its way, while Sheth and Sisodia [ 21 ] have urged for a reform. In a similar vein, Hunt [ 22 ] advised revising both marketing’s discipline and practice, while McCole [ 23 ] proposed strategies to refocus marketing theory on changing practice. Rust et al. [ 24 ] argue for reorienting marketing in firms to become more customer-centric, and Kotler [ 25 ] advocates for marketing theory and practice to conform to environmental imperatives. Also, because the business landscape is dynamic, Webster Jr. and Lusch [ 26 ] believe that marketing’s goal, premises, and models should be rethought. Finding answers to these problems keeps marketing from becoming obsolete [ 27 ] and marginalised [ 20 ], both as a discipline and as an organizational function [ 28 ].

According to the literature [ 29 , 30 ], marketing scholars have lost sight of both rigor and relevance. As a result, many scholarly journals have made it normal practice to provide implications and suggestions [ 31 ], their actual influence has been insignificant [ 20 ]. Many marketing academics have failed to address substantive topics [ 18 ], resulting in a loss of relevance [ 30 , 20 ] and a drop in marketing expertise [ 32 ].

The efforts of certain institutions (e.g., Marketing Science Institute), conferences (e.g., Theory + Practice in Marketing–TPM), and leading journals’ special issues on marketing theory and practice to bridge this gap are well recognised, with the goal of fostering dialogue and collaboration between marketing scholars and practitioners. Several solutions for bridging the marketing theory–practice gap have also emerged from existing literature: adopting the perspective of rigor–and–relevance in research [ 27 , 33 ]; focusing on emerging phenomena [ 34 , 35 ]; positioning research implications to the higher business level rather than the narrow level of the marketing department [ 36 ]; running role-relevant research driven by a deep understanding of the core tasks of the marketing department; translating research results into actionable recommendations [ 23 , 37 ].

In sum, marketing research has been criticised for not having an impact on practice since it is primarily focused on writing for other scholars and not for practitioners who might benefit from marketing research to address practical issues. Equivalently, publishing marketing research that is more useful for practitioners implies that there should be a well-functioning nexus between the theory and the marketing tools and techniques that practitioners need to deal with practical issues. In the context of social media, we still don’t know whether academic publications have an impact on practitioners. In other terms, one may ask whether social media practitioners read academic articles or refer to these publications in their practices.

Our paper considered the gaps between the theory and practice of social media and identifies where they exist. Some possible explanations for the gaps can be explored which may be of interest to both academics working in the field.

We conducted a bibliometric study, consisting of the collection, summarizing, assessing, and monitoring of published research, to create an up-to-date overview of the current marketing research on social media and statistically assess the associated literature [ 38 , 39 ]. Scopus, one of the most complete databases of academic articles, served as our data source. It indexes 12,850 periodicals in various categories and contains articles published since 1966. Scopus was chosen over Web of Science for two reasons. First, as researchers faced a trade‐off between data coverage and cleanliness, Scopus has been discovered to have a larger coverage (60% larger) than Web of Science [ 40 ]. Second, bibliometric studies in marketing research often employ only one database to avoid data homogeneity problems that could arise when using numerous databases [ 41 ].

To search the database, we first identified two keywords related to our study: “social media”, and “social media marketing”, we ran a query using a combination of these keywords (adopting the Boolean operator “OR”) in the fields related to “title,” “abstract,” and “keywords.” We considered works published only in business journals until October 2022. Proceedings, book chapters, and books were excluded from further consideration. To filter this data, we relied on a screening process. Documents were excluded based on whether they are not published in English and/or not available for the project team.

We placed the highest priority on maintaining the reliability of our dataset, which we accomplished by adhering to protocol. This protocol was carried out in four distinct phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion, as elaborated in Fig 1 . Using Mendeley’s robust features, we structured all identified studies in an organized format consisting of author names, titles, and publication years. Additionally, we conducted a thorough check to detect and remove any duplicate studies, ensuring the dataset’s cleanliness and integrity.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297241.g001

After applying our selection criteria rigorously, our initial search of the Scopus database produced a substantial dataset comprising 5345 research works. This dataset encompassed a wide range of information, including author names, article titles, the countries of corresponding authors, publication counts, comprehensive citation statistics (total citations, average article citations, and the number of citing articles, both with and without self-citations), journal sources, keywords, geographical distribution by countries, and author-level metrics. A detailed workflow outlining our selection process is depicted in Fig 1 , providing a comprehensive overview of our systematic approach.

To further enhance the comprehensiveness of our research, we implemented a backward search strategy. In this phase, we scrutinized the reference lists of the retained studies for our final review but did not identify any additional studies relevant to our research objectives.

Once we finalized our ultimate dataset, we examined the complete text of each article. We extracted and organized all pertinent information essential for our review. To streamline this process, we developed a structured data extraction tool specifically designed to record and concisely summarize the crucial details necessary to address our research inquiries. This approach aimed to minimize potential human errors and enhance procedural transparency.

The data coding phase unfolded in two distinct steps. Initially, we subjected the data extraction form to a rigorous pilot evaluation using a select sample of the finalized articles. Two of our co-authors independently conducted data extractions from this sample, allowing for a meticulous cross-check to identify and rectify any technical issues, including completeness and the form’s usability. In the second step of data coding, each article received a unique identifier. One co-author examined the complete text of each article, coding the data into specific categories, such as article title, publication year, geographic market focus, and research theme. To ensure the utmost accuracy and reliability, a second co-author rigorously reviewed the extraction form and conducted a random sample check for cross-validation. Any discrepancies or disagreements that arose during this process were thoroughly discussed and resolved to maintain the integrity of our data coding efforts.