Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

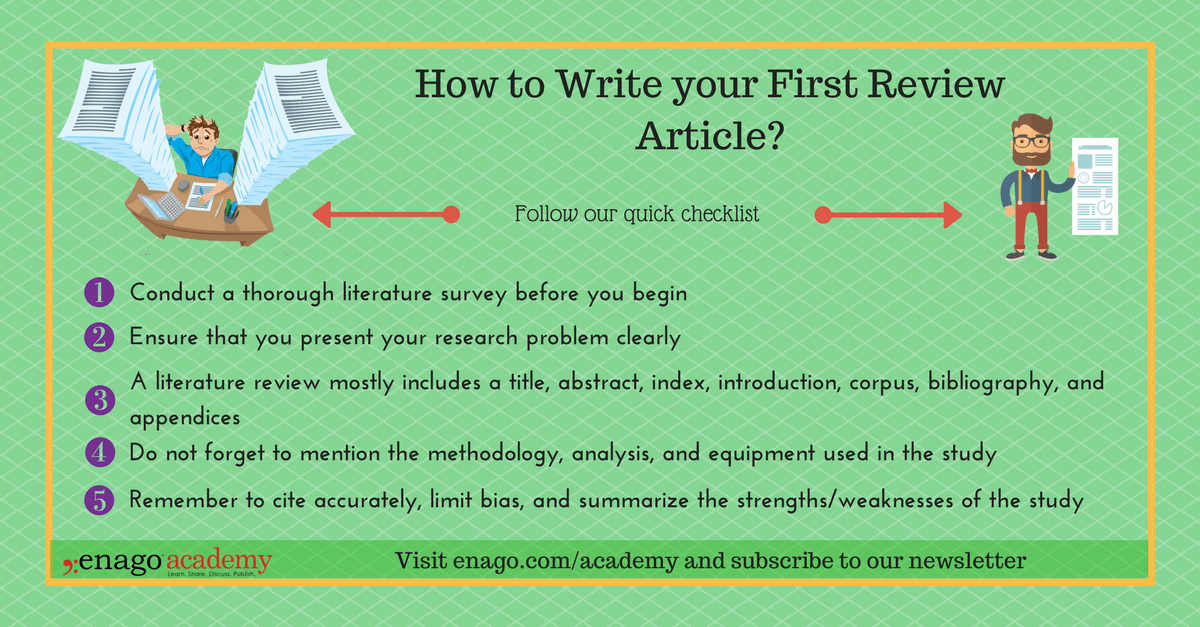

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing a Literature Review

Hundreds of original investigation research articles on health science topics are published each year. It is becoming harder and harder to keep on top of all new findings in a topic area and – more importantly – to work out how they all fit together to determine our current understanding of a topic. This is where literature reviews come in.

In this chapter, we explain what a literature review is and outline the stages involved in writing one. We also provide practical tips on how to communicate the results of a review of current literature on a topic in the format of a literature review.

7.1 What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide a synthesis and evaluation of the existing literature on a particular topic with the aim of gaining a new, deeper understanding of the topic.

Published literature reviews are typically written by scientists who are experts in that particular area of science. Usually, they will be widely published as authors of their own original work, making them highly qualified to author a literature review.

However, literature reviews are still subject to peer review before being published. Literature reviews provide an important bridge between the expert scientific community and many other communities, such as science journalists, teachers, and medical and allied health professionals. When the most up-to-date knowledge reaches such audiences, it is more likely that this information will find its way to the general public. When this happens, – the ultimate good of science can be realised.

A literature review is structured differently from an original research article. It is developed based on themes, rather than stages of the scientific method.

In the article Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Marco Pautasso explains the importance of literature reviews:

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications. For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively. Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests. Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read. For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way (Pautasso, 2013, para. 1).

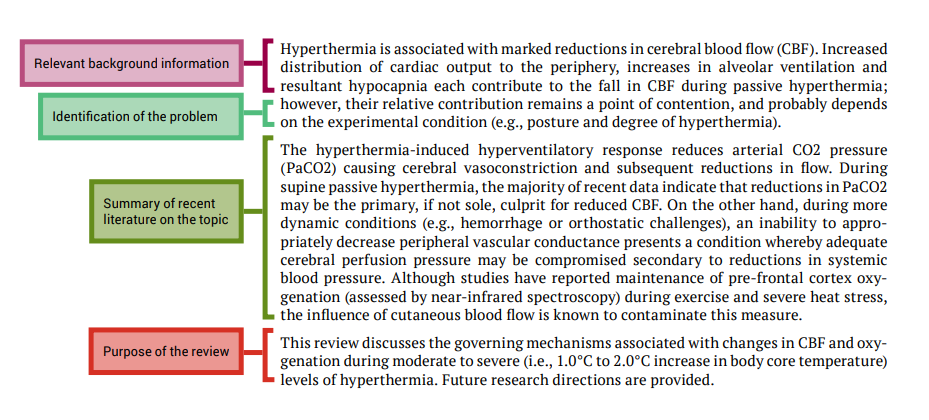

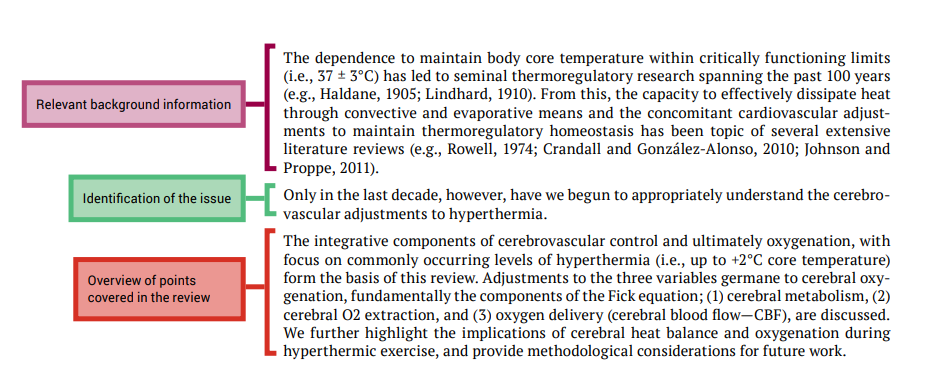

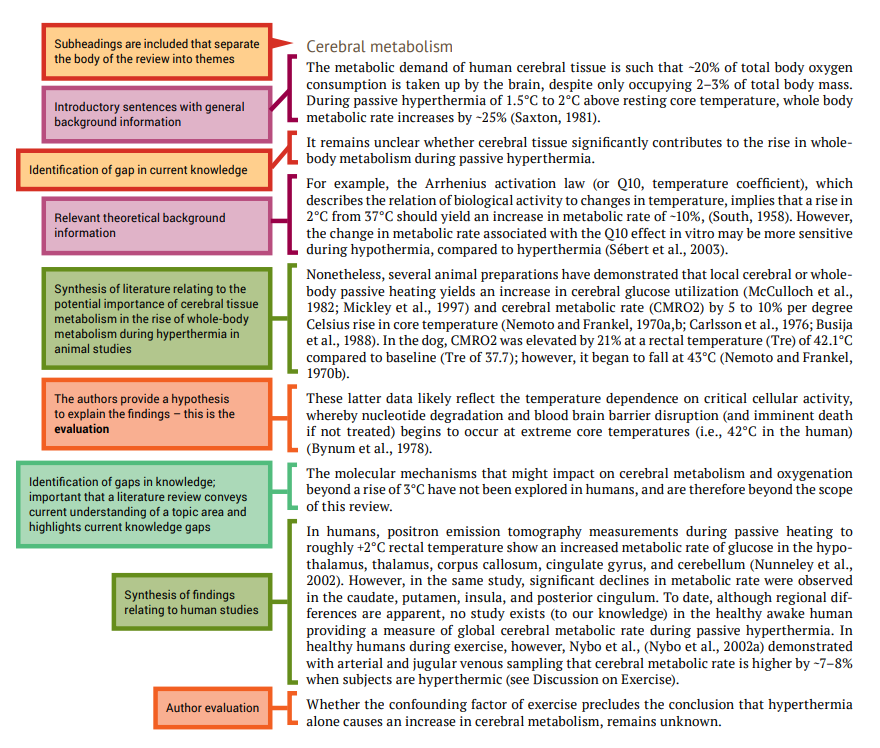

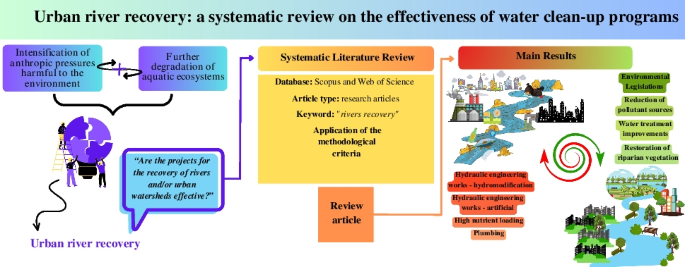

An example of a literature review is shown in Figure 7.1.

Video 7.1: What is a literature review? [2 mins, 11 secs]

Watch this video created by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky Library called ‘ What is a literature review? Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button below.

Examples of published literature reviews

- Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review

- Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review

- Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology

7.2 Steps of writing a literature review

Writing a literature review is a very challenging task. Figure 7.2 summarises the steps of writing a literature review. Depending on why you are writing your literature review, you may be given a topic area, or may choose a topic that particularly interests you or is related to a research project that you wish to undertake.

Chapter 6 provides instructions on finding scientific literature that would form the basis for your literature review.

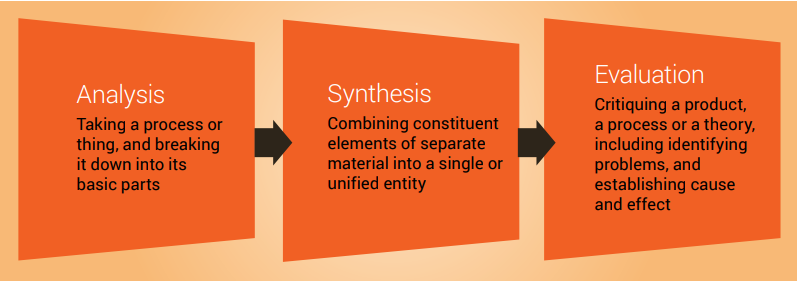

Once you have your topic and have accessed the literature, the next stages (analysis, synthesis and evaluation) are challenging. Next, we look at these important cognitive skills student scientists will need to develop and employ to successfully write a literature review, and provide some guidance for navigating these stages.

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation are three essential skills required by scientists and you will need to develop these skills if you are to write a good literature review ( Figure 7.3 ). These important cognitive skills are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

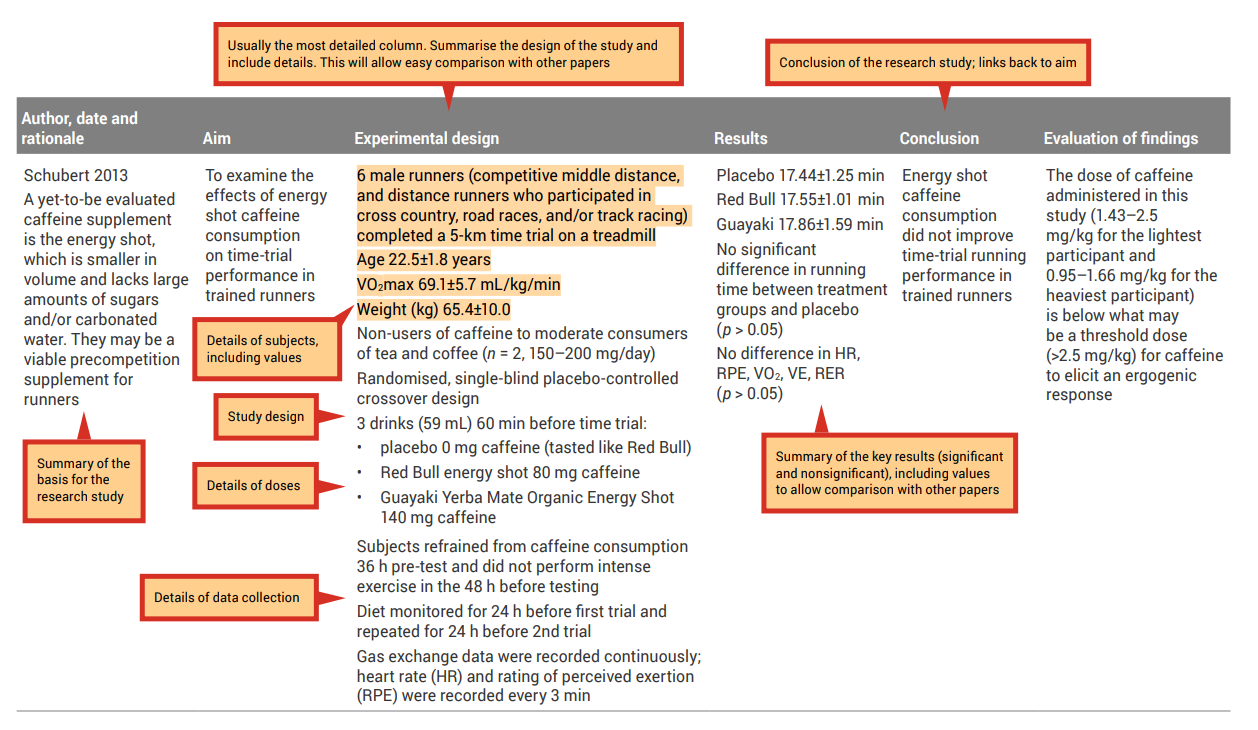

The first step in writing a literature review is to analyse the original investigation research papers that you have gathered related to your topic.

Analysis requires examining the papers methodically and in detail, so you can understand and interpret aspects of the study described in each research article.

An analysis grid is a simple tool you can use to help with the careful examination and breakdown of each paper. This tool will allow you to create a concise summary of each research paper; see Table 7.1 for an example of an analysis grid. When filling in the grid, the aim is to draw out key aspects of each research paper. Use a different row for each paper, and a different column for each aspect of the paper ( Tables 7.2 and 7.3 show how completed analysis grid may look).

Before completing your own grid, look at these examples and note the types of information that have been included, as well as the level of detail. Completing an analysis grid with a sufficient level of detail will help you to complete the synthesis and evaluation stages effectively. This grid will allow you to more easily observe similarities and differences across the findings of the research papers and to identify possible explanations (e.g., differences in methodologies employed) for observed differences between the findings of different research papers.

Table 7.1: Example of an analysis grid

Table 7.3: Sample filled-in analysis grid for research article by Ping and colleagues

Source: Ping, WC, Keong, CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41. Used under a CC-BY-NC-SA licence.

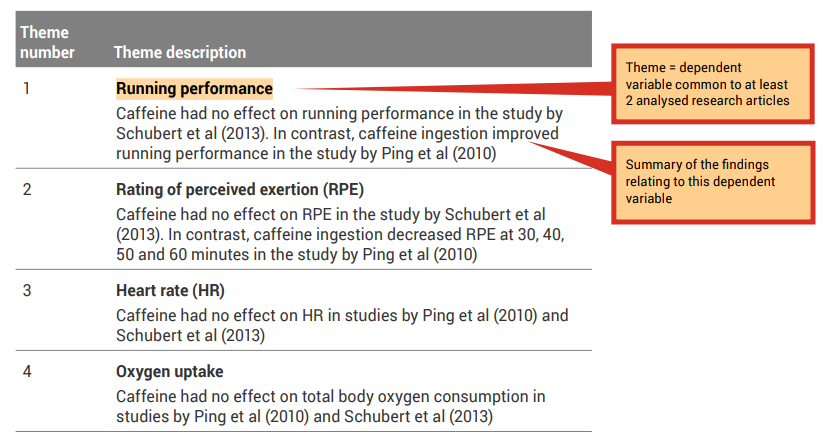

Step two of writing a literature review is synthesis.

Synthesis describes combining separate components or elements to form a connected whole.

You will use the results of your analysis to find themes to build your literature review around. Each of the themes identified will become a subheading within the body of your literature review.

A good place to start when identifying themes is with the dependent variables (results/findings) that were investigated in the research studies.

Because all of the research articles you are incorporating into your literature review are related to your topic, it is likely that they have similar study designs and have measured similar dependent variables. Review the ‘Results’ column of your analysis grid. You may like to collate the common themes in a synthesis grid (see, for example Table 7.4 ).

Step three of writing a literature review is evaluation, which can only be done after carefully analysing your research papers and synthesising the common themes (findings).

During the evaluation stage, you are making judgements on the themes presented in the research articles that you have read. This includes providing physiological explanations for the findings. It may be useful to refer to the discussion section of published original investigation research papers, or another literature review, where the authors may mention tested or hypothetical physiological mechanisms that may explain their findings.

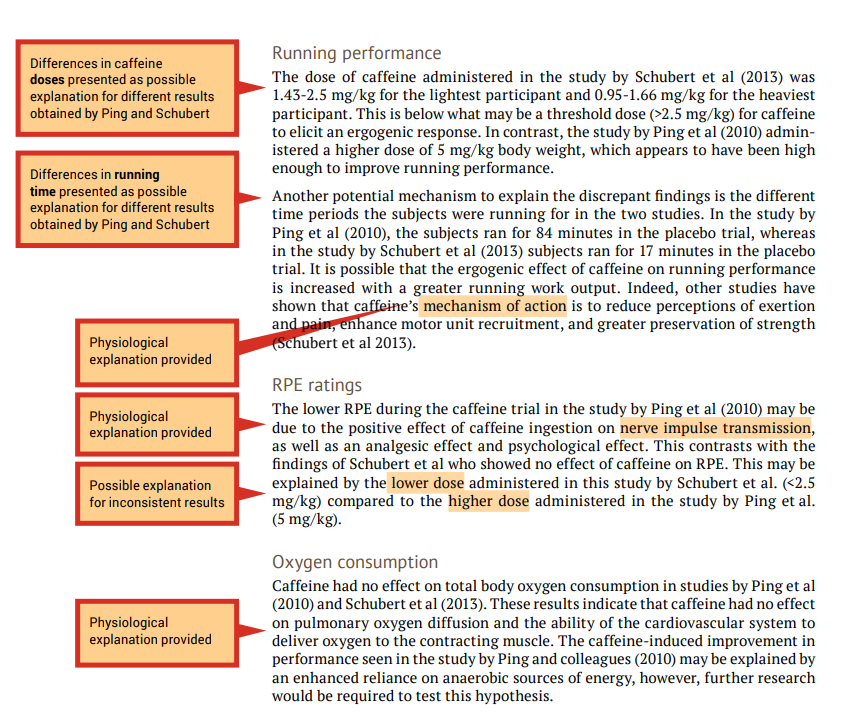

When the findings of the investigations related to a particular theme are inconsistent (e.g., one study shows that caffeine effects performance and another study shows that caffeine had no effect on performance) you should attempt to provide explanations of why the results differ, including physiological explanations. A good place to start is by comparing the methodologies to determine if there are any differences that may explain the differences in the findings (see the ‘Experimental design’ column of your analysis grid). An example of evaluation is shown in the examples that follow in this section, under ‘Running performance’ and ‘RPE ratings’.

When the findings of the papers related to a particular theme are consistent (e.g., caffeine had no effect on oxygen uptake in both studies) an evaluation should include an explanation of why the results are similar. Once again, include physiological explanations. It is still a good idea to compare methodologies as a background to the evaluation. An example of evaluation is shown in the following under ‘Oxygen consumption’.

7.3 Writing your literature review

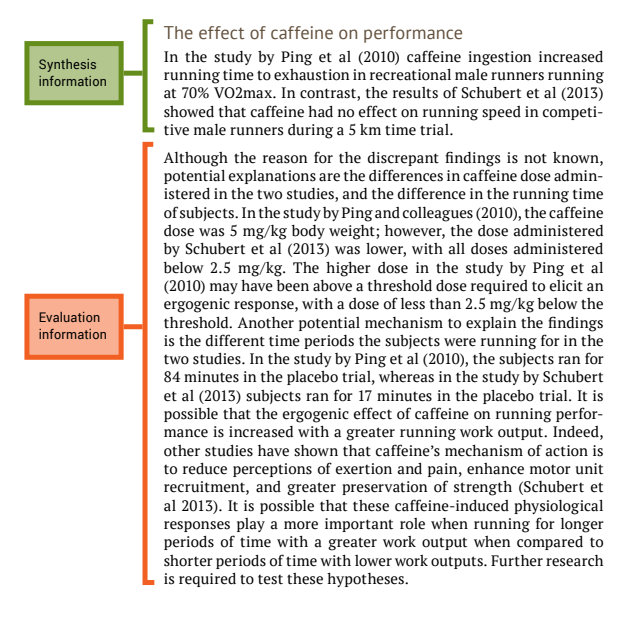

Once you have completed the analysis, and synthesis grids and written your evaluation of the research papers , you can combine synthesis and evaluation information to create a paragraph for a literature review ( Figure 7.4 ).

The following paragraphs are an example of combining the outcome of the synthesis and evaluation stages to produce a paragraph for a literature review.

Note that this is an example using only two papers – most literature reviews would be presenting information on many more papers than this ( (e.g., 106 papers in the review article by Bain and colleagues discussed later in this chapter). However, the same principle applies regardless of the number of papers reviewed.

The next part of this chapter looks at the each section of a literature review and explains how to write them by referring to a review article that was published in Frontiers in Physiology and shown in Figure 7.1. Each section from the published article is annotated to highlight important features of the format of the review article, and identifies the synthesis and evaluation information.

In the examination of each review article section we will point out examples of how the authors have presented certain information and where they display application of important cognitive processes; we will use the colour code shown below:

This should be one paragraph that accurately reflects the contents of the review article.

Introduction

The introduction should establish the context and importance of the review

Body of literature review

The reference section provides a list of the references that you cited in the body of your review article. The format will depend on the journal of publication as each journal has their own specific referencing format.

It is important to accurately cite references in research papers to acknowledge your sources and ensure credit is appropriately given to authors of work you have referred to. An accurate and comprehensive reference list also shows your readers that you are well-read in your topic area and are aware of the key papers that provide the context to your research.

It is important to keep track of your resources and to reference them consistently in the format required by the publication in which your work will appear. Most scientists will use reference management software to store details of all of the journal articles (and other sources) they use while writing their review article. This software also automates the process of adding in-text references and creating a reference list. In the review article by Bain et al. (2014) used as an example in this chapter, the reference list contains 106 items, so you can imagine how much help referencing software would be. Chapter 5 shows you how to use EndNote, one example of reference management software.

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Copyright note:

- The quotation from Pautasso, M 2013, ‘Ten simple rules for writing a literature review’, PLoS Computational Biology is use under a CC-BY licence.

- Content from the annotated article and tables are based on Schubert, MM, Astorino, TA & Azevedo, JJL 2013, ‘The effects of caffeinated ‘energy shots’ on time trial performance’, Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2062–2075 (used under a CC-BY 3.0 licence ) and P ing, WC, Keong , CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41 (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence ).

Bain, A.R., Morrison, S.A., & Ainslie, P.N. (2014). Cerebral oxygenation and hyperthermia. Frontiers in Physiology, 5 , 92.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149.

How To Do Science Copyright © 2022 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

The beauty of what science can do when urgently needed

Career Q&A 26 MAR 24

‘Woah, this is affecting me’: why I’m fighting racial inequality in prostate-cancer research

Career Q&A 20 MAR 24

So … you’ve been hacked

Technology Feature 19 MAR 24

Superconductivity case shows the need for zero tolerance of toxic lab culture

Correspondence 26 MAR 24

Cuts to postgraduate funding threaten Brazilian science — again

Is AI ready to mass-produce lay summaries of research articles?

Nature Index 20 MAR 24

Peer-replication model aims to address science’s ‘reproducibility crisis’

Nature Index 13 MAR 24

Numbers highlight US dominance in clinical research

Postdoctoral Fellow

We are seeking a highly motivated PhD and/or MD graduate to work in the Cardiovascular research lab in the Tulane University Department of Medicine.

New Orleans, Louisiana

School of Medicine Tulane University

Posdoctoral Fellow Positions in Epidemiology & Multi-Omics Division of Network Medicine BWH and HMS

Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School are seeking applicants for 3 postdoctoral positions.

Boston, Massachusetts

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH)

Postdoctoral Scholar - Ophthalmology

Memphis, Tennessee

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC)

Principal Investigator in Modeling of Plant Stress Responses

Join our multidisciplinary and stimulative research environment as Associate Professor in Modeling of Plant Stress Responses

Umeå (Kommun), Västerbotten (SE)

Umeå Plant Science Centre and Integrated Science Lab

Postdoctoral Associate- Cellular Neuroscience

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Research in the Biological and Life Sciences: A Guide for Cornell Researchers: Literature Reviews

- Books and Dissertations

- Databases and Journals

- Locating Theses

- Resource Not at Cornell?

- Citing Sources

- Staying Current

- Measuring your research impact

- Plagiarism and Copyright

- Data Management

- Literature Reviews

- Evidence Synthesis and Systematic Reviews

- Writing an Honors Thesis

- Poster Making and Printing

- Research Help

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a body of text that aims to review the critical points of current knowledge on a particular topic. Most often associated with science-oriented literature, such as a thesis, the literature review usually proceeds a research proposal, methodology and results section. Its ultimate goals is to bring the reader up to date with current literature on a topic and forms that basis for another goal, such as the justification for future research in the area. (retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literature_review )

Writing a Literature Review

The literature review is the section of your paper in which you cite and briefly review the related research studies that have been conducted. In this space, you will describe the foundation on which your research will be/is built. You will:

- discuss the work of others

- evaluate their methods and findings

- identify any gaps in their research

- state how your research is different

The literature review should be selective and should group the cited studies in some logical fashion.

If you need some additional assistance writing your literature review, the Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines offers a Graduate Writing Service .

Demystifying the Literature Review

For more information, visit our guide devoted to " Demystifying the Literature Review " which includes:

- guide to conducting a literature review,

- a recorded 1.5 hour workshop covering the steps of a literature review, a checklist for drafting your topic and search terms, citation management software for organizing your results, and database searching.

Online Resources

- A Guide to Library Research at Cornell University

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students North Carolina State University

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting Written by Dena Taylor, Director, Health Sciences Writing Centre, and Margaret Procter, Coordinator, Writing Support, University of Toronto

- How to Write a Literature Review University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz

- Review of Literature The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Print Resources

- << Previous: Writing

- Next: Evidence Synthesis and Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Oct 25, 2023 11:28 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/bio

Literature review: your definitive guide

Joanna Wilkinson

This is our ultimate guide on how to write a narrative literature review. It forms part of our Research Smarter series .

How do you write a narrative literature review?

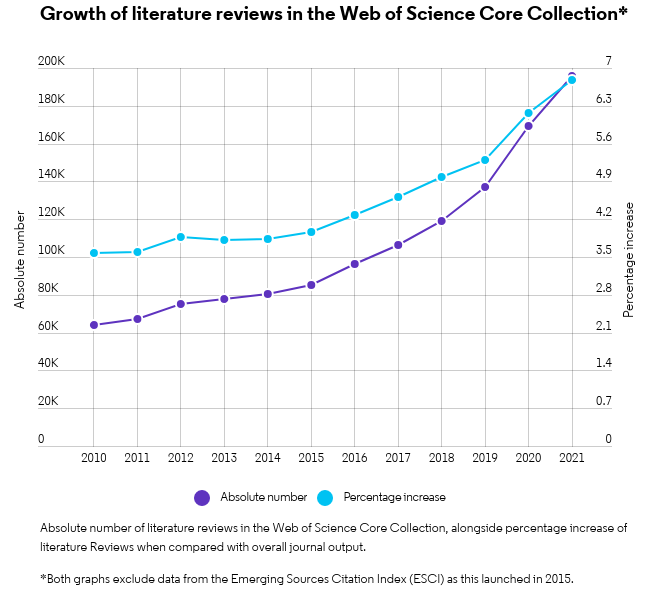

Researchers worldwide are increasingly reliant on literature reviews. That’s because review articles provide you with a broad picture of the field, and help to synthesize published research that’s expanding at a rapid pace .

In some academic fields, researchers publish more literature reviews than original research papers. The graph below shows the substantial growth of narrative literature reviews in the Web of Science™, alongside the percentage increase of reviews when compared to all document types.

It’s critical that researchers across all career levels understand how to produce an objective, critical summary of published research. This is no easy feat, but a necessary one. Professionally constructed literature reviews – whether written by a student in class or an experienced researcher for publication – should aim to add to the literature rather than detract from it.

To help you write a narrative literature review, we’ve put together some top tips in this blog post.

Best practice tips to write a narrative literature review:

- Don’t miss a paper: tips for a thorough topic search

- Identify key papers (and know how to use them)

- Tips for working with co-authors

- Find the right journal for your literature review using actual data

- Discover literature review examples and templates

We’ll also provide an overview of all the products helpful for your next narrative review, including the Web of Science, EndNote™ and Journal Citation Reports™.

1. Don’t miss a paper: tips for a thorough topic search

Once you’ve settled on your research question, coming up with a good set of keywords to find papers on your topic can be daunting. This isn’t surprising. Put simply, if you fail to include a relevant paper when you write a narrative literature review, the omission will probably get picked up by your professor or peer reviewers. The end result will likely be a low mark or an unpublished manuscript, neither of which will do justice to your many months of hard work.

Research databases and search engines are an integral part of any literature search. It’s important you utilize as many options available through your library as possible. This will help you search an entire discipline (as well as across disciplines) for a thorough narrative review.

We provide a short summary of the various databases and search engines in an earlier Research Smarter blog . These include the Web of Science , Science.gov and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).

Like what you see? Share it with others on Twitter:

[bctt tweet=”Writing a #LiteratureReview? Check out the latest @clarivateAG blog for top tips (from topic searches to working with coauthors), examples, templates and more”]

Searching the Web of Science

The Web of Science is a multidisciplinary research engine that contains over 170 million papers from more than 250 academic disciplines. All of the papers in the database are interconnected via citations. That means once you get started with your keyword search, you can follow the trail of cited and citing papers to efficiently find all the relevant literature. This is a great way to ensure you’re not missing anything important when you write a narrative literature review.

We recommend starting your search in the Web of Science Core Collection™. This database covers more than 21,000 carefully selected journals. It is a trusted source to find research papers, and discover top authors and journals (read more about its coverage here ).

Learn more about exploring the Core Collection in our blog, How to find research papers: five tips every researcher should know . Our blog covers various tips, including how to:

- Perform a topic search (and select your keywords)

- Explore the citation network

- Refine your results (refining your search results by reviews, for example, will help you avoid duplication of work, as well as identify trends and gaps in the literature)

- Save your search and set up email alerts

Try our tips on the Web of Science now.

2. Identify key papers (and know how to use them)

As you explore the Web of Science, you may notice that certain papers are marked as “Highly Cited.” These papers can play a significant role when you write a narrative literature review.

Highly Cited papers are recently published papers getting the most attention in your field right now. They form the top 1% of papers based on the number of citations received, compared to other papers published in the same field in the same year.

You will want to identify Highly Cited research as a group of papers. This group will help guide your analysis of the future of the field and opportunities for future research. This is an important component of your conclusion.

Writing reviews is hard work…[it] not only organizes published papers, but also positions t hem in the academic process and presents the future direction. Prof. Susumu Kitagawa, Highly Cited Researcher, Kyoto University

3. Tips for working with co-authors

Writing a narrative review on your own is hard, but it can be even more challenging if you’re collaborating with a team, especially if your coauthors are working across multiple locations. Luckily, reference management software can improve the coordination between you and your co-authors—both around the department and around the world.

We’ve written about how to use EndNote’s Cite While You Write feature, which will help you save hundreds of hours when writing research . Here, we discuss the features that give you greater ease and control when collaborating with your colleagues.

Use EndNote for narrative reviews

Sharing references is essential for successful collaboration. With EndNote, you can store and share as many references, documents and files as you need with up to 100 people using the software.

You can share simultaneous access to one reference library, regardless of your colleague’s location or organization. You can also choose the type of access each user has on an individual basis. For example, Read-Write access means a select colleague can add and delete references, annotate PDF articles and create custom groups. They’ll also be able to see up to 500 of the team’s most recent changes to the reference library. Read-only is also an option for individuals who don’t need that level of access.

EndNote helps you overcome research limitations by synchronizing library changes every 15 minutes. That means your team can stay up-to-date at any time of the day, supporting an easier, more successful collaboration.

Start your free EndNote trial today .

4.Finding a journal for your literature review

Finding the right journal for your literature review can be a particular pain point for those of you who want to publish. The expansion of scholarly journals has made the task extremely difficult, and can potentially delay the publication of your work by many months.

We’ve written a blog about how you can find the right journal for your manuscript using a rich array of data. You can read our blog here , or head straight to Endnote’s Manuscript Matcher or Journal Citation Report s to try out the best tools for the job.

5. Discover literature review examples and templates

There are a few tips we haven’t covered in this blog, including how to decide on an area of research, develop an interesting storyline, and highlight gaps in the literature. We’ve listed a few blogs here that might help you with this, alongside some literature review examples and outlines to get you started.

Literature Review examples:

- Aggregation-induced emission

- Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering

- Object based image analysis for remote sensing

(Make sure you download the free EndNote™ Click browser plugin to access the full-text PDFs).

Templates and outlines:

- Learn how to write a review of literature , Univ. of Wisconsin – Madison

- Structuring a literature review , Australian National University

- Matrix Method for Literature Review: The Review Matrix , Duquesne University

Additional resources:

- Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Editor, PLoS Computational Biology

- Video: How to write a literature review , UC San Diego Psychology

Related posts

Unlocking u.k. research excellence: key insights from the research professional news live summit.

For better insights, assess research performance at the department level

Getting the Full Picture: Institutional unification in the Web of Science

How to Write a Good Scientific Literature Review

Nowadays, there is a huge demand for scientific literature reviews as they are especially appreciated by scholars or researchers when designing their research proposals. While finding information is less of a problem to them, discerning which paper or publication has enough quality has become one of the biggest issues. Literature reviews narrow the current knowledge on a certain field and examine the latest publications’ strengths and weaknesses. This way, they are priceless tools not only for those who are starting their research, but also for all those interested in recent publications. To be useful, literature reviews must be written in a professional way with a clear structure. The amount of work needed to write a scientific literature review must be considered before starting one since the tasks required can overwhelm many if the working method is not the best.

Designing and Writing a Scientific Literature Review

Writing a scientific review implies both researching for relevant academic content and writing , however, writing without having a clear objective is a common mistake. Sometimes, studying the situation and defining the work’s system is so important and takes equally as much time as that required in writing the final result. Therefore, we suggest that you divide your path into three steps.

Define goals and a structure

Think about your target and narrow down your topic. If you don’t choose a well-defined topic, you can find yourself dealing with a wide subject and plenty of publications about it. Remember that researchers usually deal with really specific fields of study.

It is time to be a critic and locate only pertinent publications. While researching for content consider publications that were written 3 years ago at the most. Write notes and summarize the content of each paper as that will help you in the next step.

Time to write

Check some literature review examples to decide how to start writing a good literature review . When your goals and structure are defined, begin writing without forgetting your target at any moment.

Related: Conducting a literature survey? Wish to learn more about scientific misconduct? Check out this resourceful infographic.

Here you have a to-do list to help you write your review :

- A scientific literature review usually includes a title, abstract, index, introduction, corpus, bibliography, and appendices (if needed).

- Present the problem clearly.

- Mention the paper’s methodology, research methods, analysis, instruments, etc.

- Present literature review examples that can help you express your ideas.

- Remember to cite accurately.

- Limit your bias

- While summarizing also identify strengths and weaknesses as this is critical.

Scholars and researchers are usually the best candidates to write scientific literature reviews, not only because they are experts in a certain field, but also because they know the exigencies and needs that researchers have while writing research proposals or looking for information among thousands of academic papers. Therefore, considering your experience as a researcher can help you understand how to write a scientific literature review.

Have you faced challenges while drafting your first literature review? How do you think can these tips help you in acing your next literature review? Let us know in the comments section below! You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to copyrights answered by our team that comprises eminent researchers and publication experts.

Thank you for your information. It adds knowledge on critical review being a first time to do it, it helps a lot.

yes. i would like to ndertake the course Bio ststistics

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

AI Assistance in Academia for Searching Credible Scholarly Sources

The journey of academia is a grand quest for knowledge, more specifically an adventure to…

- Manuscripts & Grants

Writing a Research Literature Review? — Here are tips to guide you through!

Literature review is both a process and a product. It involves searching within a defined…

- AI in Academia

How to Scan Through Millions of Articles and Still Cut Down on Your Reading Time — Why not do it with an AI-based article summarizer?

Researcher 1: “It’s flooding articles every time I switch on my laptop!” Researcher 2: “Why…

How to Master at Literature Mapping: 5 Most Recommended Tools to Use

This article is also available in: Turkish, Spanish, Russian, and Portuguese

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Improving Your Chances of Publication in International Peer-reviewed Journals

Types of literature reviews Tips for writing review articles Role of meta-analysis Reporting guidelines

How to Scan Through Millions of Articles and Still Cut Down on Your Reading Time —…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

8 Tips for Writing a Scientific Literature Review Article

A scientific literature review article provides a thorough overview of the current knowledge on a certain topic. The main goal is to consider the difficulties or knowledge gaps in the field and help to fill them out. To write one requires lots of reading, but it can be an intensely satisfying process and produce a work that will be referenced and serve as a resource for students and young researchers.

Unlike an original research article, a literature review usually does not present results, such as from surveys or experiments. It’s mainly based on the combination of a thorough literature survey of published work together with the author’s critical discussion on the subject.

There are different types of literature reviews , like systematic, scoping, and conceptual, but overall, they’re all extremely valuable and useful for the scientific community, in their own way.

The eight steps below will give a simple how on writing a review.

Why to write a scientific literature review

One final note on the why before the how regarding reviews, 8 tips on how to write a scientific literature review (and a good one), 1. define a relevant question or questions that you intend to answer with the review (critical step), 2. do a literature survey, 3. create a datasheet to organize all the important information contained in each material collected, 4. define a structure for the text, 5. add context to your work, 6. extract relevant information from the literature material you selected, 7. add critical discussion, 8. make sure the english is sharp, clear, and well-edited.

There are plenty of reasons to take on the task of writing a review rather than conducting novel research.

First, as a review’s author, you can improve your knowledge of the theme and be on top of the recent findings. You can start to more closely follow the work of leading researchers and get new insights for your own research. And you position yourself as a thought-leader and knowledge-leader in the area. For an up-and-coming area, this is extremely useful.

For example, this review of the remote work literature by Charalampous et al. has been very valuable to me when I completed my dissertation. I connected with the lead author on ResearchGate. and I value our interaction .

If you’re a master’s or PhD candidate, by writing a review you’ll be producing starting material to be used on your dissertation or thesis, not to mention, obviously, that you’ll learn about the review-writing process.

And as mentioned, a good literature review article garners recognition and a considerable number of citations.

Reviews are the mark of a true scholar.

Research studies can be classified as qualitative or quantitative and whether your literature review is focused on one of these classes or the other will have an influence on its design.

The following tips below generally fit both qualitative and quantitative articles, although adaptations can be made in specific topics.

These tips don’t necessarily need to follow the exact order. Reviews can be iterative, and you’ll naturally happen across new references .

That will be your scope. Importantly, keep lists of topics that are and are not within your scope. This will help to determine what you’ll ultimately include in your initial survey.

Search for articles on the theme using appropriate keywords (research terms) and filters.

Include keywords associated with concepts or variables of your interest and also list synonyms or related terms.

For example, let’s say you want to write about drug abuse among college students. You can use the keywords such as “drug abuse”, “substance abuse”, “college students”, “university students”, and “undergraduate students”.

You can add filters to select articles in a specific language (e.g., English or Spanish) or that have been published recently (e.g., last 5 years), for example.

As we see with “college” and “university”, there are commonly different ways to say the same thing, and Boolean operators will help you here. Specifics are given below.

You can do the search directly on publishers’ and journals’ websites, on the reference lists of relevant papers, and using.

For these databases, ideally, you’ll have a good online library to use. There are also ways to find research articles for free .

You can choose from multidisciplinary sources (e.g., Google Scholar , Scopus , Web of Science ), or sources specific to a given area (e.g., Open Edition for social sciences, PubMed for biomedical sciences).

To complement the review, look for materials other than research articles by visiting government websites, international organization websites, and credible newspaper articles.

However you do your search, keep the following in mind:

- Check that there are no similar recent reviews addressing the very same question. Otherwise, there’s obviously no point in going further unless you’re taking a different angle.

- Consider if there’s enough research material to write about. Available literature can vary significantly from topic to topic. Try to examine if there are sufficient articles to make a robust discussion, contrast results and ideas, or make any conclusion. If there is no previous literature review on the subject, even a small number of papers may be OK. If other reviews have already been published, investigate what else has emerged since it was released.

- If your survey results in too many articles, narrow it down by adding new keywords or filters that match the specifications you consider most important. Look for topics that haven’t yet been thoroughly reviewed or for which there are conflicting data worthy of discussion.

- Use Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”, “NOT”, etc.) together with the keywords to filter the results. Let’s take the same example on drug abuse among college students and imagine you don’t want alcohol to be included as a type of drug abuse in your search. In this case, you can combine keywords and operators this way: “drug abuse” OR “substance abuse” AND “college students” NOT alcohol.

Do a first selection of the articles by reading their titles and abstracts. If that doesn’t provide enough information for you, read the results and conclusions. There’s usually no need to get into the introduction or methods until later.

Eliminate works that don’t match the scope of the review. Then, organize the final data in a way to facilitate the writing process later on.

A based way to do this is using an Excel or Google Sheets spreadsheet. The rows represent each article and columns represent important groups of information such as authors, year of publication, methodology, main findings, etc.

Even better can be to use referencing software such as Mendeley to label and organize the works you download.

Although a literature review’s structure may vary based on journal guidelines and your preferences, it should at least contain a title, keywords, abstract, introduction, main text, discussion, conclusion, and references.

If you’re working on a systematic review, you can add a Methods section to describe the criteria you’ve used to select articles to review. You may also end the review with Future Perspectives for the field, considering your knowledge of the theme.

At this point, you can start considering journals for submission.

As there are many journal options out there, you may find it helpful to use journal finder tools like those at Elsevier , Springer , Wiley , and others .

Carefully read the instructions for authors and the formatting requirements of the journal you choose. Not all journals accept review articles, but there are some journals exclusively dedicated to them.

If publication time is important for you, check the journal or inquire directly to find the normal time for publication.

Start by creating an introduction, ideally not too long, addressing the main concepts and the current state of the field.

Call attention to the relevance of the theme and make clear why a review is needed and how it can be helpful. Then specify the goals of the review and what exactly the reader will find in your text.

If you are doing a more rigorous review, mention data sources and research methods used to select articles and define inclusion and exclusion criteria.

See this systematic literature review about social media and mental health problems in adolescents.

Note that already in the introduction the authors explore the scenario of mental health in adolescents, explain the concept of social media and contextualize what is known and what are the gaps regarding the relationship between social media and mental health problems in adolescents.

As a rigorous systematic literature review, a Methods section gives full details on how the survey was conducted.

In the main text, write about the articles’ findings, including the methods and parameters used. Does this especially if your review is focused on quantitative studies.

When dealing with qualitative studies, you may present the sampling methods applied.

Extract enough information to answer your research questions. You can group articles with similar characteristics and split the text on subheadings accordingly.

You also have the option to mention articles chronologically, if that’s relevant to the work.

Remember to summarize information so the text is objective and clear. You can work with appropriate graphical schemes, images, and tables – these can help the reader to better understand and memorize the important information.

See this literature review on the detection of depression and mental illness signs using social media . The authors divided the main text into subtopics according to the methods used by the analyzed articles to detect signs of mental illness.

A figure is provided to illustrate each method and the number of articles that used it. The review also presents a table summarizing important information from the articles.

Include your point of view and indicate the strengths and weaknesses of the works you wrote about. Address debate on conflicting results, when necessary.

This fits interestingly into the discussion of contrasting concepts, theories, and assumptions presented in different qualitative studies, for instance. Also, recognize the limitations of your own work.

Provide the main conclusion of your literature review. In this final section of the review, it may be interesting to make suggestions for future research.

See this review about the associations between maternal nutrition and breast milk composition . In the subheadings of the main text (“Main results” section), the authors discuss the results of the articles investigated and emphasize conflicting information among studies.

A final discussion is provided addressing the limitations of the studies. The main conclusions obtained from the literature review are presented in the final paragraph.

See this review about maternal obesity and breastfeeding characteristics . The authors present the findings of their literature survey and a “Discussion” section with explanations and possible confounding factors involved.

An individual topic is dedicated to the limitations of their review (for example, the authors say that “9 of the 18 studies included used self-reported maternal weight and height. Such estimates are not completely accurate with the possible risk of misclassification of BMI categories” [Turcksin et al., 2014, p. 180). Special sections approaching the implications of their findings for future research and for clinical practice are also provided.

Check for spelling and grammar mistakes and add all the references correctly. Use reference management software to avoid wasting time with formatting. There are free and user-friendly options to do so (e.g., Zotero , Mendeley ).

Better is to get a professional scientific edit . There are options available for editing. Choose the one that works for you, and make sure they’re capable and qualified.

Good luck with your review!

Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review . Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 24 (2):218i234.

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26 (2):91-108.

Turcksin, R., Bel, S., Galjaard, S., & Devlieger, R. (2014). Maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity and duration: a systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition , 10 (2), 166-183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00439.x

Wee, B. V., & Banister, D. (2016). How to write a literature review paper? Transport Reviews, 36 (2), 278-288.

Privacy Overview

Privacy Policy - Terms and Conditions

How to write a good scientific review article

Affiliation.

- 1 The FEBS Journal Editorial Office, Cambridge, UK.

- PMID: 35792782

- DOI: 10.1111/febs.16565

Literature reviews are valuable resources for the scientific community. With research accelerating at an unprecedented speed in recent years and more and more original papers being published, review articles have become increasingly important as a means to keep up to date with developments in a particular area of research. A good review article provides readers with an in-depth understanding of a field and highlights key gaps and challenges to address with future research. Writing a review article also helps to expand the writer's knowledge of their specialist area and to develop their analytical and communication skills, amongst other benefits. Thus, the importance of building review-writing into a scientific career cannot be overstated. In this instalment of The FEBS Journal's Words of Advice series, I provide detailed guidance on planning and writing an informative and engaging literature review.

© 2022 Federation of European Biochemical Societies.

Publication types

- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

How to Conduct a Literature Review (Health Sciences and Beyond)

What is a literature review, traditional (narrative) literature review, integrative literature review, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, scoping review.

- Developing a Research Question

- Selection Criteria

- Database Search

- Documenting Your Search

- Organize Key Findings

- Reference Management

Ask Us! Health Sciences Library

The health sciences library.

Call toll-free: (844) 352-7399 E-mail: Ask Us More contact information

Related Guides

- Systematic Reviews by Roy Brown Last Updated Oct 17, 2023 282 views this year

- Write a Literature Review by John Glover Last Updated Oct 16, 2023 1700 views this year

A literature review provides an overview of what's been written about a specific topic. There are many different types of literature reviews. They vary in terms of comprehensiveness, types of study included, and purpose.

The other pages in this guide will cover some basic steps to consider when conducting a traditional health sciences literature review. See below for a quick look at some of the more popular types of literature reviews.

For additional information on a variety of review methods, the following article provides an excellent overview.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. Review. PubMed PMID: 19490148.

- Next: Developing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 12:22 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.vcu.edu/health-sciences-lit-review

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 9 methods for literature reviews.

Guy Paré and Spyros Kitsiou .

9.1. Introduction

Literature reviews play a critical role in scholarship because science remains, first and foremost, a cumulative endeavour ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). As in any academic discipline, rigorous knowledge syntheses are becoming indispensable in keeping up with an exponentially growing eHealth literature, assisting practitioners, academics, and graduate students in finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the contents of many empirical and conceptual papers. Among other methods, literature reviews are essential for: (a) identifying what has been written on a subject or topic; (b) determining the extent to which a specific research area reveals any interpretable trends or patterns; (c) aggregating empirical findings related to a narrow research question to support evidence-based practice; (d) generating new frameworks and theories; and (e) identifying topics or questions requiring more investigation ( Paré, Trudel, Jaana, & Kitsiou, 2015 ).

Literature reviews can take two major forms. The most prevalent one is the “literature review” or “background” section within a journal paper or a chapter in a graduate thesis. This section synthesizes the extant literature and usually identifies the gaps in knowledge that the empirical study addresses ( Sylvester, Tate, & Johnstone, 2013 ). It may also provide a theoretical foundation for the proposed study, substantiate the presence of the research problem, justify the research as one that contributes something new to the cumulated knowledge, or validate the methods and approaches for the proposed study ( Hart, 1998 ; Levy & Ellis, 2006 ).

The second form of literature review, which is the focus of this chapter, constitutes an original and valuable work of research in and of itself ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Rather than providing a base for a researcher’s own work, it creates a solid starting point for all members of the community interested in a particular area or topic ( Mulrow, 1987 ). The so-called “review article” is a journal-length paper which has an overarching purpose to synthesize the literature in a field, without collecting or analyzing any primary data ( Green, Johnson, & Adams, 2006 ).

When appropriately conducted, review articles represent powerful information sources for practitioners looking for state-of-the art evidence to guide their decision-making and work practices ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, high-quality reviews become frequently cited pieces of work which researchers seek out as a first clear outline of the literature when undertaking empirical studies ( Cooper, 1988 ; Rowe, 2014 ). Scholars who track and gauge the impact of articles have found that review papers are cited and downloaded more often than any other type of published article ( Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008 ; Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, Haynes, & Hedges, 2003 ; Patsopoulos, Analatos, & Ioannidis, 2005 ). The reason for their popularity may be the fact that reading the review enables one to have an overview, if not a detailed knowledge of the area in question, as well as references to the most useful primary sources ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Although they are not easy to conduct, the commitment to complete a review article provides a tremendous service to one’s academic community ( Paré et al., 2015 ; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Most, if not all, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of medical informatics publish review articles of some type.

The main objectives of this chapter are fourfold: (a) to provide an overview of the major steps and activities involved in conducting a stand-alone literature review; (b) to describe and contrast the different types of review articles that can contribute to the eHealth knowledge base; (c) to illustrate each review type with one or two examples from the eHealth literature; and (d) to provide a series of recommendations for prospective authors of review articles in this domain.

9.2. Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

As explained in Templier and Paré (2015) , there are six generic steps involved in conducting a review article:

- formulating the research question(s) and objective(s),

- searching the extant literature,

- screening for inclusion,

- assessing the quality of primary studies,

- extracting data, and

- analyzing data.

Although these steps are presented here in sequential order, one must keep in mind that the review process can be iterative and that many activities can be initiated during the planning stage and later refined during subsequent phases ( Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013 ; Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ).

Formulating the research question(s) and objective(s): As a first step, members of the review team must appropriately justify the need for the review itself ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ), identify the review’s main objective(s) ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ), and define the concepts or variables at the heart of their synthesis ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ; Webster & Watson, 2002 ). Importantly, they also need to articulate the research question(s) they propose to investigate ( Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ). In this regard, we concur with Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey (2011) that clearly articulated research questions are key ingredients that guide the entire review methodology; they underscore the type of information that is needed, inform the search for and selection of relevant literature, and guide or orient the subsequent analysis. Searching the extant literature: The next step consists of searching the literature and making decisions about the suitability of material to be considered in the review ( Cooper, 1988 ). There exist three main coverage strategies. First, exhaustive coverage means an effort is made to be as comprehensive as possible in order to ensure that all relevant studies, published and unpublished, are included in the review and, thus, conclusions are based on this all-inclusive knowledge base. The second type of coverage consists of presenting materials that are representative of most other works in a given field or area. Often authors who adopt this strategy will search for relevant articles in a small number of top-tier journals in a field ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In the third strategy, the review team concentrates on prior works that have been central or pivotal to a particular topic. This may include empirical studies or conceptual papers that initiated a line of investigation, changed how problems or questions were framed, introduced new methods or concepts, or engendered important debate ( Cooper, 1988 ). Screening for inclusion: The following step consists of evaluating the applicability of the material identified in the preceding step ( Levy & Ellis, 2006 ; vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). Once a group of potential studies has been identified, members of the review team must screen them to determine their relevance ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). A set of predetermined rules provides a basis for including or excluding certain studies. This exercise requires a significant investment on the part of researchers, who must ensure enhanced objectivity and avoid biases or mistakes. As discussed later in this chapter, for certain types of reviews there must be at least two independent reviewers involved in the screening process and a procedure to resolve disagreements must also be in place ( Liberati et al., 2009 ; Shea et al., 2009 ). Assessing the quality of primary studies: In addition to screening material for inclusion, members of the review team may need to assess the scientific quality of the selected studies, that is, appraise the rigour of the research design and methods. Such formal assessment, which is usually conducted independently by at least two coders, helps members of the review team refine which studies to include in the final sample, determine whether or not the differences in quality may affect their conclusions, or guide how they analyze the data and interpret the findings ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Ascribing quality scores to each primary study or considering through domain-based evaluations which study components have or have not been designed and executed appropriately makes it possible to reflect on the extent to which the selected study addresses possible biases and maximizes validity ( Shea et al., 2009 ). Extracting data: The following step involves gathering or extracting applicable information from each primary study included in the sample and deciding what is relevant to the problem of interest ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Indeed, the type of data that should be recorded mainly depends on the initial research questions ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ). However, important information may also be gathered about how, when, where and by whom the primary study was conducted, the research design and methods, or qualitative/quantitative results ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Analyzing and synthesizing data : As a final step, members of the review team must collate, summarize, aggregate, organize, and compare the evidence extracted from the included studies. The extracted data must be presented in a meaningful way that suggests a new contribution to the extant literature ( Jesson et al., 2011 ). Webster and Watson (2002) warn researchers that literature reviews should be much more than lists of papers and should provide a coherent lens to make sense of extant knowledge on a given topic. There exist several methods and techniques for synthesizing quantitative (e.g., frequency analysis, meta-analysis) and qualitative (e.g., grounded theory, narrative analysis, meta-ethnography) evidence ( Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005 ; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

9.3. Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

EHealth researchers have at their disposal a number of approaches and methods for making sense out of existing literature, all with the purpose of casting current research findings into historical contexts or explaining contradictions that might exist among a set of primary research studies conducted on a particular topic. Our classification scheme is largely inspired from Paré and colleagues’ (2015) typology. Below we present and illustrate those review types that we feel are central to the growth and development of the eHealth domain.

9.3.1. Narrative Reviews

The narrative review is the “traditional” way of reviewing the extant literature and is skewed towards a qualitative interpretation of prior knowledge ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). Put simply, a narrative review attempts to summarize or synthesize what has been written on a particular topic but does not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from what is reviewed ( Davies, 2000 ; Green et al., 2006 ). Instead, the review team often undertakes the task of accumulating and synthesizing the literature to demonstrate the value of a particular point of view ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ). As such, reviewers may selectively ignore or limit the attention paid to certain studies in order to make a point. In this rather unsystematic approach, the selection of information from primary articles is subjective, lacks explicit criteria for inclusion and can lead to biased interpretations or inferences ( Green et al., 2006 ). There are several narrative reviews in the particular eHealth domain, as in all fields, which follow such an unstructured approach ( Silva et al., 2015 ; Paul et al., 2015 ).