Classics & Ancient History Warwick Classics Network

The revolt of boudica according to cassius dio, cassius dio published 80 volumes of history on ancient rome, beginning with the arrival of aeneas in italy and ending with the events of ad 229. written in ancient greek over 22 years, dio's work covers approximately 1,000 years of history. many of his 80 books have survived intact, or as fragments. the text below is dio's account of boudica's revolt from book lxii.

[Text below is from the Loeb edition translated by J. Jackson and accessed via Lacus Curtius ]

1 While this sort of child's play was going on in Rome, a terrible disaster occurred in Britain. Two cities were sacked, eighty thousand of the Romans and of their allies perished, and the island was lost to Rome. Moreover, all this ruin was brought upon the Romans by a woman, a fact which in itself caused them the greatest shame. Indeed, Heaven gave them indications of the catastrophe beforehand. 2 For at night there was heard to issue from the senate-house foreign jargon mingled with laughter, and from the theatre outcries and lamentations, though no mortal man had uttered the words or the groans; houses were seen under the water in the river Thames, and the ocean between the island and Gaul once grew blood-red at flood tide.

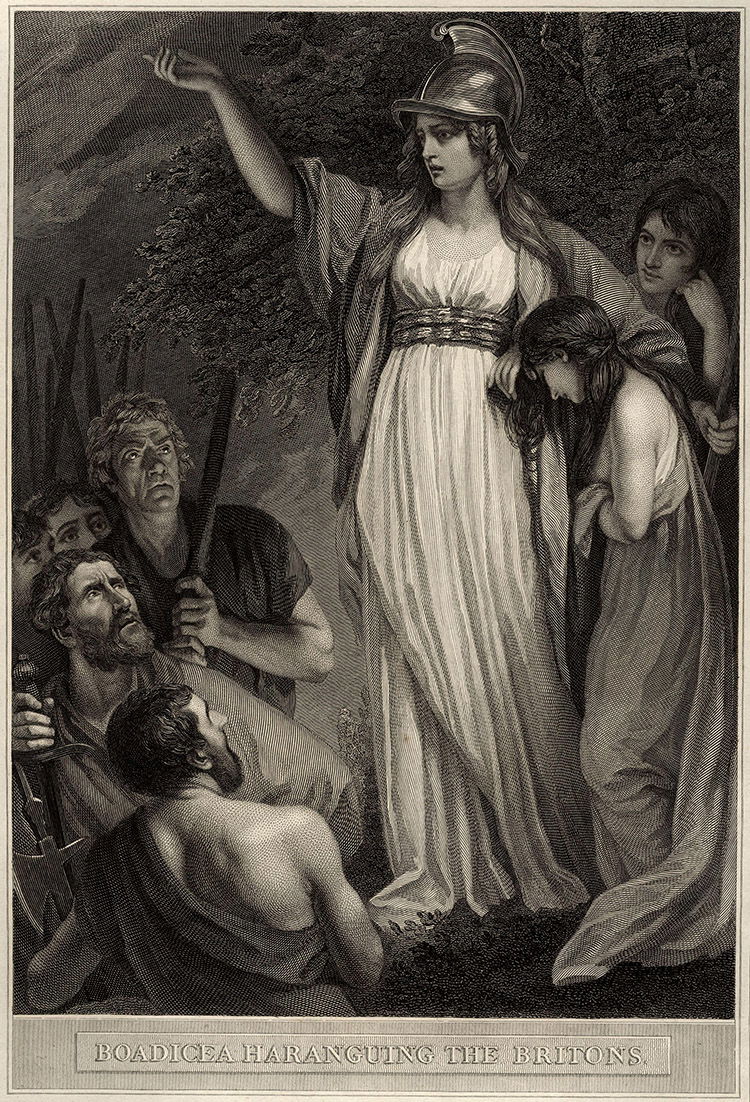

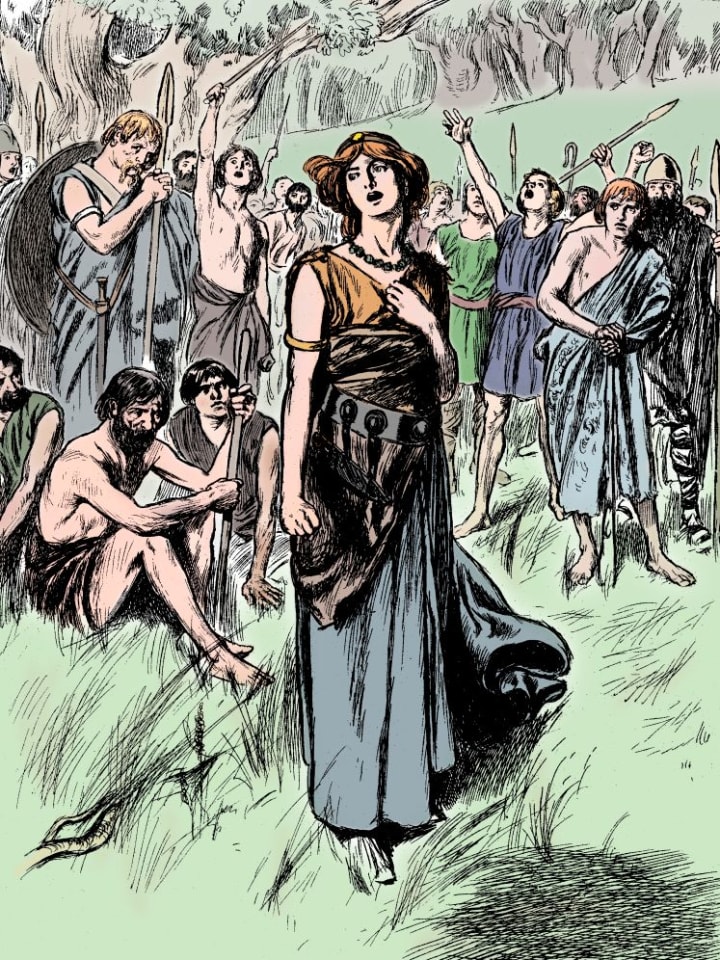

2 An excuse for the war was found in the confiscation of the sums of money that Claudius had given to the foremost Britons; for these sums, as Decianus Catus, the procurator of the island, maintained, were to be paid back. This was one reason for the uprising; another was found in the fact that Seneca, in the hope of receiving a good rate of interest, had lent to the islanders 40,000,000 sesterces that they did not want, and had afterwards called in this loan all at once and had resorted to severe measures in exacting it. 2 But the person who was chiefly instrumental in rousing the natives and persuading them to fight the Romans, the person who was thought worthy to be their leader and who directed the conduct of the entire war, was Buduica, a Briton woman of the royal family and possessed of greater intelligence than often belongs to women. 3 This woman assembled her army, to the number of some 120,000, and then ascended a tribunal which had been constructed of earth in the Roman fashion. In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce, and her voice was harsh; 4 a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace; and she wore a tunic of divers colours over which a thick mantle was fastened with a brooch. This was her invariable attire. She now grasped a spear to aid her in terrifying all beholders and spoke as follows:

3 "You have learned by actual experience how different freedom is from slavery. Hence, although some among you may previously, through ignorance of which was better, have been deceived by the alluring promises of the Romans, yet now that you have tried both, you have learned how great a mistake you made in preferring an imported despotism to your ancestral mode of life, and you have come to realize how much better is poverty with no master than wealth with slavery. 2 For what treatment is there of the most shameful or grievous sort that we have not suffered ever since these men made their appearance in Britain? Have we not been robbed entirely of most of our possessions, and those the greatest, while for those that remain we pay taxes? 3 Besides pasturing and tilling for them all our other possessions, do we not pay a yearly tribute for our very bodies? How much better it would be to have been sold to masters once for all than, possessing empty titles of freedom, to have to ransom ourselves every year! How much better to have been slain and to have perished than to go about with a tax on our heads! Yet why do I mention death? 4 For even dying is not free of cost with them; nay, you know what fees we deposit even for our dead. Among the rest of mankind death frees even those who are in slavery to others; only in the case of the Romans do the very dead remain alive for their profit. 5 Why is it that, though none of us has any money (how, indeed, could we, or where would we get it?), we are stripped and despoiled like a murderer's victims? And why should the Romans be expected to display moderation as time goes on, when they have behaved toward us in this fashion at the very outset, when all men show consideration even for the beasts they have newly captured?

4 "But, to speak the plain truth, it is we who have made ourselves responsible for all these evils, in that we allowed them to set foot on the island in the first place instead of expelling them at once as we did their famous Julius Caesar, — yes, and in that we did not deal with them while they were still far away as we dealt with Augustus and with Gaius Caligula and make even the attempt to sail hither a formidable thing. 2 As a consequence, although we inhabit so large an island, or rather a continent, one might say, that is encircled by the sea, and although we possess a veritable world of our own and are so separated by the ocean from all the rest of mankind that we have been believed to dwell on a different earth and under a different sky, and that some of the outside world, aye, even their wisest men, have not hitherto known for a certainty even by what name we are called, we have, notwithstanding all this, been despised and trampled underfoot by men who know nothing else than how to secure gain. 3 However, even at this late day, though we have not done so before, let us, my countrymen and friends and kinsmen, — for I consider you all kinsmen, seeing that you inhabit a single island and are called by one common name, — let us, I say, do our duty while we still remember what freedom is, that we may leave to our children not only its appellation but also its reality. For, if we utterly forget the happy state in which we were born and bred, what, pray, will they do, reared in bondage?

5 "All this I say, not with the purpose of inspiring you with a hatred of present conditions, — that hatred you already have, — nor with fear for the future, — that fear you already have, — but of commending you because you now of our own accord choose the requisite course of action, and of thanking you for so readily co-operating with me and with each other. 2 Have no fear whatever of the Romans; for they are superior to us neither in numbers nor in bravery. And here is the proof: they have protected themselves with helmets and breastplates and greaves and yet further provided themselves with palisades and walls and trenches to make sure of suffering no harm by an incursion of their enemies. For they are p91 influenced by their fears when they adopt this kind of fighting in preference to the plan we follow of rough and ready action. 3 Indeed, we enjoy such a surplus of bravery, that we regard our tents as safer than their walls and our shields as affording greater protection than their whole suits of mail. As a consequence, we when victorious capture them, and when overpowered elude them; and if we ever choose to retreat anywhere, we conceal ourselves in swamps and mountains so inaccessible that we can be neither discovered or taken. 4 Our opponents, however, can neither pursue anybody, by reason of their heavy armour, nor yet flee; and if they ever do slip away from us, they take refuge in certain appointed spots, where they shut themselves up as in a trap. 5 But these are not the only respects in which they are vastly inferior to us: there is also the fact that they cannot bear up under hunger, thirst, cold, or heat, as we can. They require shade and covering, they require kneaded bread and wine and oil, and if any of these things fails them, they perish; for us, on the other hand, any grass or root serves as bread, the juice of any plant as oil, any water as wine, any tree as a house. 6 Furthermore, this region is familiar to us and is our ally, but to them it is unknown and hostile. As for the rivers, we swim them naked, whereas they do not across them easily even with boats. Let us, therefore, go against them trusting boldly to good fortune. Let us show them that they are hares and foxes trying to rule over dogs and wolves."

6 When she had finished speaking, she employed a p93 species of divination, letting a hare escape from the fold of her dress; and since it ran on what they considered the auspicious side, the whole multitude shouted with pleasure, and Buduica, raising her hand toward heaven, said: 2 "I thank thee, Andraste, and call upon thee as woman speaking to woman; for I rule over no burden-bearing Egyptians as did Nitocris, nor over trafficking Assyrians as did Semiramis (for we have by now gained thus much learning from the Romans!), 3 much less over the Romans themselves as did Messalina once and afterwards Agrippina and now Nero (who, though in name a man, is in fact a woman, as is proved by his singing, lyre-playing and beautification of his person); nay, those over whom I rule are Britons, men that know not how to till the soil or ply a trade, but are thoroughly versed in the art of war and hold all things in common, even children and wives, so that the latter possess the same valour as the men. 4 As the queen, then, of such men and of such women, I supplicate and pray thee for victory, preservation of life, and liberty against men insolent, unjust, insatiable, impious, — if, indeed, we ought to term those people men who bathe in warm water, eat artificial dainties, drink unmixed wine, anoint themselves with myrrh, sleep on soft couches with boys for bedfellows, — boys past their prime at that, — and are slaves to a lyre-player and a poor one too. p95 5 Wherefore may this Mistress Domitia-Nero reign no longer over me or over you men; let the wench sing and lord it over Romans, for they surely deserve to be the slaves of such a woman after having submitted to her so long. But for us, Mistress, be thou alone ever our leader."

7 Having finished an appeal to her people of this general tenor, Buduica led her army against the Romans; for these chanced to be without a leader, inasmuch as Paulinus, their commander, had gone on an expedition to Mona, an island near Britain. This enabled her to sack and plunder two Roman cities, and, as I have said, to wreak indescribable slaughter. Those who were taken captive by the Britons were subjected to every known form of outrage. 2 The worst and most bestial atrocity committed by their captors was the following. They hung up naked the noblest and most distinguished women and then cut off their breasts and sewed them to their mouths, in order to make the victims appear to be eating them; afterwards they impaled the women on sharp skewers run lengthwise through the entire body. 3 All this they did to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and wanton behaviour, not only in all their other sacred places, but particularly in the grove of Andate. This was their name for Victory, and they regarded her with most exceptional reverence.

8 Now it chanced that Paulinus had already brought Mona to terms, and so on learning of the disaster in Britain he at once set sail thither from Mona. However, he was not willing to risk a conflict with the barbarians immediately, as he feared their numbers and their desperation, but was inclined to postpone battle to a more convenient season. But as he grew short of food and the barbarians pressed relentlessly upon him, he was compelled, contrary to his judgment, to engage them. 2 Buduica, at the head of an army of about 230,000 men, rode in a chariot herself and assigned the others to their several stations. Paulinus could not extend his line the whole length of hers, for, even if the men had been drawn up only one deep, they would not have reached far enough, so inferior were they in numbers; 3 nor, on the other hand, did he dare join battle in a single compact force, for fear of being surrounded and cut to pieces. He therefore separated his army into three divisions, in order to fight at several points at one and the same time, and he made each of the divisions so strong that it could not easily be broken through.

9 While ordering and arranging his men he also exhorted them, saying: "Up, fellow-soldiers! Up, Romans! Show these accursed wretches how far we surpass them even in the midst of evil fortune. It would be shameful, indeed, for you to lose ingloriously now what but a short time ago you won by your valour. Many a time, assuredly, have both we ourselves and our fathers, with far fewer numbers than we have at present, conquered far more numerous antagonists. 2 Fear not, then, their numbers or their spirit of rebellion; for their boldness rests on nothing more than headlong rashness unaided by arms or training. Neither fear them because they have burned a couple of cities; for they did not capture p99 them by force nor after a battle, but one was betrayed and the other abandoned to them. Exact from them now, therefore, the proper penalty for these deeds, and let them learn by actual experience the difference between us, whom they have wronged, and themselves."

10 1 After addressing these words to one division he came to another and said: "Now is the time, fellow-soldiers, for zeal, now is the time for daring. For if you show yourselves brave men to‑day, you will recover all that you have lost; if you overcome these foes, no one else will any longer withstand us. By one such battle you will both make your present possessions secure and subdue whatever remains; 2 for everywhere our soldiers, even though they are in other lands, will emulate you and foes will be terror-stricken. Therefore, since you have it within your power either to rule all mankind without a fear, both the nations that your fathers left to you and those that you yourselves have gained in addition, or else to be deprived of them altogether, choose to be free, to rule, to live in wealth, and to enjoy prosperity, rather than, by avoiding the effort, to suffer the opposite of all this."

11 1 After making an address of this sort to these men, he went on to the third division, and to them he said: "You have heard what outrages these damnable men have committed against us, nay more, you have even witnessed some of them. 2 Choose, then, whether you wish to suffer the same treatment yourselves as our comrades have suffered and to be driven p101 out of Britain entirely, besides, or else by conquering to avenge those that have perished and at the same time furnish to the rest of mankind an example, not only of benevolent clemency toward the obedient, but also of inevitable severity toward the rebellious. 3 For my part, I hope, above all, that victory will be ours; first, because the gods are our allies (for they almost always side with those who have been wronged); second, because of the courage that is our heritage, since we are Romans and have triumphed over all mankind by our valour; next, because of our experience (for we have defeated and subdued these very men who are now arrayed against us); and lastly, because of our prestige (for those with whom we are about to engage are not antagonists, but our slaves, whom we conquered even when they were free and independent). 4 Yet if the outcome should prove contrary to our hope, — for I will not shrink from mentioning even this possibility, — it would be better for us to fall fighting bravely than to be captured and impaled, to look upon our own entrails cut from our bodies, to be spitted on red-hot skewers, to perish by being melted in boiling water — in a word, to suffer as though we had been thrown to lawless and impious wild beasts. 5 Let us, therefore, either conquer them or die on the spot. Britain will be a noble monument for us, even though all the other Romans here should be driven out; for in any case our bodies shall for ever possess this land."

12 1 After addressing these and like words to them he raised the signal for battle. Thereupon the armies approached each other, the barbarians with much shouting mingled with menacing battle-songs, but the Romans silently and in order until they came within a javelin's throw of the enemy. 2 Then, while their foes were still advancing against them at a walk, the Romans rushed forward at a signal and charged them at full speed, and when the clash came, easily broke through the opposing ranks; but, as they were surrounded by the great numbers of the enemy, they had to be fighting everywhere at once. 3 Their struggle took many forms. Light-armed troops exchanged missiles with light-armed, heavy-armed were opposed to heavy-armed, cavalry clashed with cavalry, and against the chariots of the barbarians the Roman archers contended. The barbarians would assail the Romans with a rush of their chariots, knocking them helter-skelter, but, since they fought with breastplates, would themselves be repulsed by the arrows. Horseman would overthrow foot-soldiers and foot-soldiers strike down horseman; 4 a group of Romans, forming in close order, would advance to meet the chariots, and others would be scattered by them; a band of Britons would come to close quarters with the archers and rout them, while others were content to dodge their shafts at a distance; and all this was going on not at one spot only, but in all three divisions at once. 5 They contended for a long time, both parties being animated by the same zeal and daring. But finally, late in the day, the Romans prevailed; and they slew many in battle beside the wagons and the forest, and captured many alike. 6 Nevertheless, not a few made their escape and were preparing to fight again. In the meantime, however, Buduica fell sick and died. The Britons mourned her deeply and gave her a costly burial; but, feeling that now at last they were really defeated, they scattered to their homes. So much for affairs in Britain.

Historical Academy

Tacitus on Boudicca’s Revolt

When we think of great revolts in history, it’s hard not to acknowledge the fierce rebellion led by Boudicca against the Roman Empire. The story of this warrior queen and her courageous fight against Roman oppression is best documented by Tacitus, a prominent historian of ancient Rome.

In his works, Tacitus provides us with valuable insight into Boudicca’s revolt and the political climate that surrounded it. This article will delve into what exactly Tacitus has to say about this fascinating moment in history.

It’s important to note that Tacitus wasn’t just any historian – he had a unique perspective on the events he documented. As the son-in-law of Agricola, a key figure in Roman Britain, Tacitus had access to firsthand accounts and records that other historians didn’t. Additionally, his writings were critical of Rome’s imperial power, so we can expect an interesting take on Boudicca’s revolt from him.

Let’s dive into his account and uncover the details of this captivating uprising against one of history’s greatest empires.

Tacitus’ Background

In this article section, we will delve into the background of Tacitus, one of the most prominent historians who documented Boudicca’s revolt.

Gaius Cornelius Tacitus was a senator and historian of the Roman Empire who lived from approximately 56-120 AD. He is best known for his works ‘Annales,’ ‘Historiae,’ ‘Agricola,’ and ‘Germania,’ which provide valuable insights into Roman history during the reigns of various emperors.

Tacitus’ account of Boudicca’s revolt against Roman rule in Britain is found in his work ‘Annals.’ This historical narrative covers events from the death of Augustus in 14 AD to the death of Nero in 68 AD.

Boudicca, queen of the Iceni tribe, led a significant uprising against Roman occupation around 60-61 AD following her husband’s death and Rome’s mistreatment of her people. While there are few primary sources detailing this event, Tacitus’ account remains one of the most reliable and informative sources for historians studying Boudicca’s revolt.

As we have explored Tacitus’ background and his significance to our understanding of Boudicca’s revolt, it becomes clear that his work plays an essential role in reconstructing this pivotal event in ancient British history.

Despite limitations on primary source material, historians can rely on Tacitus’ accounts to gain a deeper insight into both Roman life during this time and the motivations behind Boudicca’s fight for justice against oppressive forces.

Causes Of The Revolt

Having delved into Tacitus’ background, we now shift our focus to the heart of the matter: the causes of Boudicca’s revolt. As a Roman historian, Tacitus provides valuable insight into the factors that led to this uprising against Roman rule in Britain around 60-61 AD.

The Boudican Revolt, as it came to be known, was a fierce and bloody conflict led by a female leader who inspired her people – the indigenous Iceni tribe – to rise up against their oppressors. From Tacitus’ accounts, we can identify three main causes of the revolt:

- Financial exploitation and heavy taxation: The Romans imposed burdensome taxes on the British tribes they had conquered. When King Prasutagus of the Iceni died, he left half his wealth to Rome in an attempt to secure peace and protection for his family. However, Roman officials seized all his property instead, disregarding his will and leaving his family destitute.

- Cultural imposition: The Romans sought to suppress Celtic religious practices and force their own beliefs upon native Britons. This cultural erasure sparked outrage among indigenous people who saw their traditions under threat from foreign invaders.

- Physical abuse: Tacitus describes horrific acts committed by Roman soldiers against Iceni nobles, including flogging Queen Boudicca herself and assaulting her daughters.

The culmination of these grievances fueled Boudicca’s determination to drive out the Romans from Britain once and for all. She rallied her people with impassioned speeches that painted a vivid picture of Roman atrocities and called for retribution through bloodshed.

Tacitus’ account provides a unique perspective on this female leader’s quest for justice in response to Rome’s tyranny over her people. As we delve deeper into this fascinating chapter of history, it becomes evident that the seeds of discontent sown by economic exploitation, cultural imposition, and physical abuse ultimately gave rise to a powerful force of resistance led by Boudicca.

This revolt, though ultimately unsuccessful in the long run, remains a symbol of resilience and bravery among the indigenous people of Britain.

Boudicca’s Motivations

Boudicca’s motivations for leading the British revolt against Roman rule are deeply rooted in history and personal grievances.

As a queen of the Iceni tribe, Boudicca had experienced firsthand the oppressive nature of Roman rule.

Tacitus, a Roman historian, provides valuable insight into the events that led to Boudicca’s revolt.

According to him, King Prasutagus, Boudicca’s husband, had made an agreement with Rome to divide his kingdom between his daughters and Emperor Nero upon his death.

However, when Prasutagus passed away, the Romans ignored this agreement and seized all of his property.

The mistreatment extended beyond the usurpation of their land; it was also personal.

Tacitus recounts how Boudicca was brutally flogged by Roman soldiers while her daughters were subjected to horrific acts of violence.

These atrocities fueled her motivations further and contributed significantly to her decision to lead the British revolt against Roman occupation.

Boudicca sought not only retribution for what had been done to her family but also liberation for all tribes suffering under Roman tyranny.

Boudicca was able to unite various tribes in a common cause against Rome by capitalizing on widespread resentment towards their oppressors.

Her impassioned speeches inspired thousands of warriors who shared her hatred for Rome and desired freedom from its grasp.

The strength of Boudicca’s convictions and her ability to rally others behind her cause led to a fierce rebellion that shook the foundations of Roman rule in Britain.

Although ultimately unsuccessful in achieving lasting independence from Rome, Boudicca’s revolt remains an enduring symbol of resistance against oppression and serves as a testament to her courage and determination in challenging one of history’s most powerful empires.

Roman Strategies

The sun glinted off polished helmets and gleaming swords as Suetonius Paulinus, the Roman governor of Britain, marshaled his forces to face the fierce revolt led by Boudicca. Utilizing his vast military skill, he had carefully chosen the location for the climactic battle that would determine the fate of Roman rule in Britain.

Surrounded by dense forest on three sides, Paulinus ensured that the legio XIV Gemina and their auxiliaries would be protected from any surprise attack and could capitalize on their superior discipline and training.

As Boudicca’s horde of British warriors descended upon them, Suetonius Paulinus calmly deployed his men in a narrow front to maximize their advantage in close-quarters combat. The battle raged as the Romans held firm against wave after wave of ferocious attacks, with both sides suffering heavy casualties.

Despite being significantly outnumbered, Paulinus’ troops displayed unwavering resolve and determination, knowing that their very survival depended on repelling the revolt.

As day turned into night and the dust settled on the battlefield, it became apparent that Suetonius Paulinus’ strategies had been successful. The Roman legions had held their ground against overwhelming odds and crushed Boudicca’s rebellion once and for all.

This decisive victory not only restored Rome’s control over Britain but also served as a testament to the power of disciplined military organization combined with exceptional leadership. With legio XIV Gemina etched into history for their role in quelling this uprising, future generations would remember how Rome met its adversaries head-on, even when faced with seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Battle Of Watling Street

The Battle of Watling Street was a critical confrontation in Boudicca’s revolt against Roman rule. The battle occurred in 61 AD and marked the end of the uprising led by Boudicca, queen of the Iceni tribe.

British history online has numerous accounts of this pivotal battle, which was also documented by Tacitus, the renowned Roman historian. Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, the Roman governor of Britain at that time, played a crucial role in defeating Boudicca and her army. Tacitus provided detailed descriptions of Gaius’ strategy during the battle.

By selecting a narrow battlefield with limited access points and a dense forest behind him, Gaius positioned his forces in a way that allowed them to maximize their strengths while minimizing their weaknesses. This tactical advantage proved to be vital as it enabled the Romans to overcome the numerical superiority of Boudicca’s forces.

Despite facing overwhelming odds, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and his troops emerged victorious in the Battle of Watling Street. This decisive victory effectively ended Boudicca’s revolt and solidified Roman control over Britain for centuries to come.

While Boudicca’s rebellion ultimately failed, her story remains an important part of British history online and serves as an enduring symbol of resistance against oppression.

Roman Victory And Aftermath

The Roman victory over Boudicca’s revolt was a significant turning point in the history of Roman Britain. Tacitus, the renowned Roman historian, provides us with an invaluable account of this event and its aftermath.

The Romans, led by their capable military leader Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, were able to quell the uprising and reestablish control over the province.

In the aftermath of Boudicca’s revolt, there were substantial changes in both the political and social landscape of Roman Britain. The Iceni and other British tribes that participated in the rebellion faced severe reprisals from their conquerors. Many leaders were executed or imprisoned, while thousands of people were enslaved as a punishment for their insubordination.

Tacitus also tells us that after this event, Rome implemented new strategies to prevent such uprisings from happening again. This included strengthening the Roman presence in Britain and building more fortifications throughout the region.

Despite these efforts to suppress future rebellions, it is important to recognize that Boudicca’s revolt had lasting effects on both sides of the conflict. For Rome, it served as a reminder of their vulnerability and prompted them to adapt their governance style by being more inclusive towards native Britons.

On the other hand, Boudicca’s courage and determination inspired generations of British leaders who continued to resist Rome’s dominance. In this sense, her legacy remains an enduring symbol of resistance against foreign oppression in British history.

British Resistance

Let’s take a trip back in time, as we dive deeper into the story of Boudicca’s revolt and the British resistance against Roman rule. Tacitus, the renowned Roman historian, provides us with a valuable insight into this tumultuous period in history education, revealing the tenacity and courage of those who fought against oppression.

Boudicca’s revolt was a monumental event that showcased the power of British resistance against their oppressors. The fearless queen Boudicca led her people to rise up against Gaius Suetonius and his formidable Roman legions. According to Tacitus, Boudicca was a striking figure – tall, with fierce eyes and long red hair – who inspired her followers through her passion and determination to reclaim their land from the Romans.

Her army managed to inflict significant damage on Roman settlements like Colchester, London, and St Albans before ultimately facing defeat at the hands of Suetonius’ disciplined forces.

As we reflect on this captivating chapter in history education, it is important not only to remember Boudicca’s revolt for its trailblazing spirit but also for how it has shaped our understanding of British resistance during that era. Tacitus’ accounts allow us to appreciate the resilience and bravery exhibited by Boudicca and her people while they fought for their freedom against an empire that seemed invincible at first glance.

Their story serves as a powerful reminder that even in times of overwhelming adversity, there will always be those who stand up and fight for what they believe is right.

Historical Significance

The historical significance of Boudicca’s revolt, as recorded by Tacitus, cannot be overstated. It serves as a stark reminder of the brutality and resilience exhibited by both the Roman Empire and the native tribes of Britain during this tumultuous period.

Suetonius’ decision to withdraw from Anglesey and focus on quelling Boudicca’s uprising was crucial in determining the outcome of this conflict. The Battle of Watling Street, where Boudicca’s forces were ultimately defeated, marked a turning point in Roman-British relations.

The events leading up to and including Boudicca’s revolt have left an indelible mark on history for several reasons:

- The sheer scale of devastation caused by the conflict is staggering, with Tacitus reporting that approximately 80,000 people lost their lives during the course of the rebellion.

- The revolt highlighted the harsh treatment of native Britons by Roman occupiers, who often dismissed them as barbarians and subjected them to cruel punishments.

- Boudicca herself has become a symbol of resistance against oppression, embodying courage in the face of insurmountable odds.

- Lastly, Tacitus’ account provides valuable insights into Roman military strategies and tactics employed during this time.

Without downplaying any aspect or event mentioned above, it is essential to recognize that these moments have shaped contemporary perspectives on ancient Rome and Britain. The enduring image of Boudicca leading her forces into battle against an imperial power serves as a testament to human bravery and tenacity.

Furthermore, it offers a unique lens through which historians can analyze gender roles within ancient societies – particularly regarding female leadership in times of war. As we continue to examine our past through primary sources like Tacitus’ works, we gain a deeper understanding not only about specific events like Battle Bridge but also about broader themes that continue to influence modern society today.

Tacitus’ Narrative

Having delved into the historical significance of Boudicca’s revolt, it is essential to examine Tacitus’ narrative, which serves as one of the primary sources for our understanding of this event.

As a Roman historian, Tacitus provides a comprehensive account of Boudicca’s revolt against the Roman Empire in his work ‘Annals.’ His narrative has been invaluable for modern historians seeking to piece together the details of this uprising and its impact on Roman Britain.

Tacitus’ account presents a detailed and vivid picture of Boudicca’s revolt, capturing not only the military aspects but also shedding light on the motives behind it. He describes how oppressive taxation and mistreatment by Roman officials led to widespread anger among the Britons, ultimately culminating in their decision to rise against their occupiers.

In doing so, Tacitus provides valuable context that helps modern historians better understand why this rebellion occurred and what fueled it.

While Tacitus’ narrative remains an indispensable source for studying Boudicca’s revolt, it is crucial to remember that his perspective was shaped by his role as a Roman historian. Consequently, some aspects of his account may be biased or influenced by prevailing attitudes towards the Britons within the empire.

Nevertheless, when his narrative is considered alongside other accounts by historians like Cassius Dio and archaeological evidence unearthed over time, we can begin to form a more nuanced understanding of this pivotal event in ancient British history.

Impact Of Tacitus’ Account

You won’t believe the far-reaching impact of Tacitus’ account on Boudicca’s revolt! Not only did his writings provide us with invaluable historical insights, but they also shaped our understanding of the events and their implications. This article section delves into those very effects, shedding light on how Tacitus’ work has influenced both academic discourse and popular imagination over time.

- First and foremost, Tacitus’ account has been a crucial source of information for historians studying Roman Britain.

- Second, it has shaped our perception of Boudicca as a powerful female leader and a symbol of resistance against Roman oppression.

- Third, his writings have informed modern interpretations of the conflict in literature, film, and other forms of media.

- Finally, the account has sparked debates among scholars regarding its accuracy and objectivity.

One cannot overstate the significance of Tacitus’ portrayal of Boudicca’s revolt in shaping her image as a heroic figure who fought valiantly for her people’s freedom. His vivid descriptions not only brought her story to life but also highlighted her exceptional leadership skills that defied traditional gender norms in ancient societies. This representation has contributed to Boudicca’s enduring legacy as an iconic symbol of female empowerment and resistance against tyranny – a figure that continues to inspire generations.

As we delve deeper into the influence of this seminal account on our understanding of history, it is essential to recognize its limitations as well. Some scholars have raised questions about its accuracy due to potential bias or exaggeration in Tacitus’ narrative style. Despite these concerns, there is no denying that his work remains an indispensable resource for comprehending Boudicca’s revolt and its broader implications on Roman Britain – enriching our knowledge and appreciation for this fascinating period in history.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Corrections

Boudica’s Revolt: When Britannia’s Warrior Queen Took On Rome

Roman rule of the newly conquered provinces of Britannia was brutal, harsh, and exploitative. Led by Boudica, the warrior queen of the Iceni, the Britons violently revolted against their oppressors.

Rome began its slow, piecemeal conquest of Britannia in 43 AD , subduing the various tribes one by one. Some tribes sought to preserve their independence by allying themselves with Rome. Prasutagus was one of eleven kings who surrendered to the Roman emperor Claudius following the initial Roman conquest in 43 AD. As such he was officially installed as king of the Iceni and ally of Rome. His long reign was remembered as being particularly prosperous. When Prasutagus died, he named the Roman emperor Nero as his co-heir along with his two daughters. While Prasutagus had hoped that this would ensure the safety of his kingdom, and his family, it instead set the stage for Boudica’s massive revolt.

Boudica And The Ravages Of The Romans

Boudica’s husband, Prasutagus, named the Roman emperor Nero as co-heir with his two daughters in his will. It was hoped that this act of deference would protect his lands and his family. However, the will was ignored, and local Roman officials moved to seize Prasutagus’ lands and property. Earlier loans that had been made to the leading men of Britannia were called in all at once by Decianus Catus, procurator of the province who demanded repayment in full. Roman centurions broke into Prasutagus’ home, ostensibly in search of the money. In the process, they scourged Prasutagus’ wife Boudica and raped his two daughters.

The sources agree that Boudica was herself, a woman of royal descent. She was said to have tall, with long tawny hair that hung below her waist. Her voice was strong, and harsh, which complimented her piercing stare. As befitted a woman of her stature in Britannia, she wore a large golden necklace, possibly a torc , and a colorful tunic fastened by a brooch. It was the harsh treatment that she and her daughters received at the hands of the Romans which was the immediate cause of this powerful woman’s revolt.

Call To Arms

Following the Roman assault on Boudica and her daughters, the Iceni began to conspire with their neighboring tribes, such as the Trinovantes and others. Boudica was soon chosen to lead the revolt; her oratory skills were said to be quite impressive. Not willing to leave anything to chance, Boudica also performed acts of divination to raise the morale of the army and hopefully guarantee victory. According to one story, she released a hare from within the folds of her dress and interpreted the direction it ran as the path laid out for the army by Andraste, a British goddess of victory.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

The timing of the revolt was well planned. Gaius Suetonius Paulinus , the Roman governor of Britain was on the far side of the island leading a military campaign. British rebels had taken refuge on the island of Mona (modern Anglesey in North Wales), stronghold of the druids . At the time of Boudica’s revolt , Suetonius and most of the Roman forces in Britain were occupied with this campaign. It would therefore take them a considerable amount of time to finish up their campaign and march back across the island. In the meantime, Boudica’s revolt would be able to spread and destroy any isolated Roman forces left behind in a piecemeal fashion.

Rage And Rebellion Against Rome

The first target of Boudica’s army was the city of Camulodunum (modern Colchester). This city was formerly the capital of the Trinovates. However, the Romans had seized most of the land and transformed the city into a colonia , a settlement established to reward Roman veterans for their service. Not only had the Roman veterans and other settlers mistreated the local Britons, but they also forced them to pay for the construction of a temple to the deceased emperor Claudius during whose reign the Romans had invaded Britain. As such, Camulodunum had become the focus of British resentment.

Boudica’s rebellion and approaching army had not gone unnoticed by the inhabitants of Camulodunum. They appealed to the procurator Decianus Catus for reinforcements, but he sent only a mere 200 additional cavalrymen. Boudica’s large army smashed its way into the city, methodically destroying everything in its path. A bronze statue of the emperor Nero, which probably stood in front of the temple to Claudius was toppled and decapitated. Its head was taken away as a trophy. The last defenders took refuge in the temple to Claudius where they were able to hold out for another two days before the Britons broke in. Modern archaeological excavations have confirmed the widespread destruction of the city.

A Legion And Londinium

During the attack on Camulodunum, an attempt was made to relieve the city by Quintus Petillius Cerialis . Brother in law of the future emperor Vespasian , Cerialis would later play a leading role in the Year of the Four Emperors and the Batavian Revolt. At the time of Boudica’s revolt, he was the commander of the Legio IX Hispania . Boudica’s already victorious army intercepted Cerialis’ forces before they could reach the ruins of Camulodunum. In the ensuing battle, all the Roman infantrymen were killed and Cerialis barely managed to escape back to the Roman camp with what was left of his cavalry. After this defeat, Decianus Catus, the man whose actions had started this chain of events fled to Gaul.

In the meantime, Suetonius and his forces had rapidly returned from their victorious campaign against Mona. Boudica’s next target appeared to be the city of Londinium . Founded shortly after the Roman conquest of 43 AD, Londinium was quickly becoming a thriving commercial center. However, Suetonius soon concluded that he lacked the numbers to defend the city and decided to abandon it. When Boudica’s army arrived, all those who had not evacuated were slaughtered and the city was burned to the ground. Modern archaeological excavations have revealed that the destruction extended to the city’s suburbs on the southern bank of the Thames river.

Suetonius Rallies The Romans

After the destruction of Londinium, Boudica’s army next attacked the municipium of Verulamium (modern St. Albans) . Here the archaeological evidence is limited, so the full extent of the destruction is unclear. According to the sources, the total number of people killed by Boudica’s forces in the three cities was 70,000-80,000. The numbers were so high because the Britons had no interest in taking slaves or prisoners and killed all they came across.

While Boudica destroyed Londinium and Verulamium, Suetonius was busy gathering as many soldiers as he could find. The Legio IX Hispania had been routed by Boudica’s forces earlier and was in no condition to fight, while the prefect of the Legio II Augusta was either unable or unwilling to converge with Suetonius’ army. Nevertheless, Suetonius was able to gather an army which included the Legio XIV Gemina and the Legio XX Valeria Victrix , along with several units of auxiliaries. This meant that Suetonius now had an army of around 10,000 with which to face Boudica’s army. Though greatly exaggerated by the sources as now numbering around 230,000-300,000, Boudica clearly had the far larger army.

Boudica’s Revolt: Battle For Britain

The exact location of the battle between Boudica’s Britons and Suetonius’ Romans is unknown. The sources describe the battlefield as being inside of a defile, and mention woods behind the Roman position. Traditionally, the battlefield is located along the Roman road known as Watling Street, possibly near the modern High Cross in Leicestershire at the junction of Watling Street and Fosse Way.

In any event, when the two armies met the British lines extended far beyond those of the Romans, who were greatly outnumbered. Boudica addressed her army from her chariot and gave a short speech before ordering an attack. However, in order to attack the Romans, Boudica’s army needed to pass through the defile which forced them together into an unwieldy mass. As the compact mass of Britons advanced, the Romans rained missiles down onto them.

When the Romans finally expended all their missiles they charged forward in a wedge-like formation. The disordered Britons attempted to retreat but were blocked by a cordon of their own wagons which had come up behind their army. Enraged by the destruction of so many towns and the deaths of so many Roman civilians, Suetonius’ soldiers gave no quarter to any British men, women, children, or animals.

Aftermath And Aftershocks

Boudica did not survive long after the defeat , though the sources are divided regarding her fate. According to one version, she committed suicide by ingesting poison, while in another version she died of an illness and was given a lavish funeral. Suetonius conducted a brutal punitive campaign against the tribes who had fought alongside Boudica. Fearing that Suetonius’ actions would provoke another rebellion, the emperor Nero replaced him with a more conciliatory governor. Catus Decianus, whose actions incited the rebellion and who fled to Gaul was relieved of his position and replaced. Surprisingly, there is no record of what became of Boudica’s two daughters.

While Boudica’s revolt did not last long it was serious enough to cause the Roman emperor Nero to consider abandoning Britain. This may have been the goal of the Britons who were said to have drawn inspiration from a similar revolt in Roman Germany led by Arminius . However, Suetonius’s victory was enough to confirm Roman control of the province . The Romans had many years of hard campaigning ahead and they never completely conquered the island of Britain.

Boudica’s Legacy Today

Ultimately, Boudica’s revolt was a failure. Yet her story was recorded by the Roman historian Tacitus, one of the greatest historians of Rome. So, while the memory of Boudica faded over time, she was never completely forgotten. In Britain, Boudica continued to feature in Medieval chronicles, such as in the 6th-century work of Gildas . Boudica was reintroduced by Polydore Vergil and Raphael Holinshed in the mid-16th century. Shortly thereafter, Boudica became associated with Elizabeth I who in 1588 sought to defend Britain from the Spanish Armada.

By the early modern period, there was renewed interest in her life and achievements. In the Victorian era interest in Boudica exploded. She was featured in poems, paintings, statuary, and even had several ships named after her. Suffragettes also adopted Boudica as one of their symbols in the early 20th century. Today there are permanent Boudica displays in some of the most important museums in England, such as the Museum of London , Colchester Castle Museum, and Verulamium Museum . There is even a 36 mi (58km) footpath called Boudica’s Way which passes through the countryside of Norfolk.

Emperor Claudius: 14 Facts about an Unlikely Hero

By Robert C. L. Holmes MA Ancient & Medieval History, BA Archaeology Robert Holmes has an MA in Ancient & Medieval History and a BA in Archaeology. He is an independent historian and author, who specializes in the Military History of the Ancient and Medieval World and has published over a dozen articles on related topics. Originally from Massachusetts, he now lives in Florida where he works doing public history leading tours, giving lectures, and educating people about the local history.

Frequently Read Together

7 Fascinating Women in Ancient Rome You Should Know

4 Celtic Warriors Who Became Figures of Legend

Roman Emperor Vespasian Restores Order To The Empire

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Boudica: Celtic War Queen Who Challenged Rome

She slaughtered a Roman army. She torched Londinium, leaving a charred layer almost half a meter thick that can still be traced under modern London. According to the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus, her army killed as many as 70,000 civilians in Londinium, Verulamium and Camulodunum, rushing ‘to cut throats, hang, burn, and crucify. Who was she? Why was she so angry?

Most of Boudica’s life is shrouded in mystery. She was born around AD 25 to a royal family in Celtic Britain, and as a young woman she married Prasutagus, who later became king (a term adopted by the Celts, but as practiced by them, more of an elected chief) of the Iceni tribe. They had two daughters, probably born during the few years immediately after the Roman conquest in ad 43. She may have been Iceni herself, a cousin of Prasutagus, and she may have had druidic training. Even the color of her hair is mysterious. Another Roman historian, Cassius Dio — who wrote long after she died — described it with a word translators have rendered as fair, tawny, and even flaming red, though Dio probably intended his audience to picture it as golden-blonde with perhaps a reddish tinge. Her name meant victory.

Boudica’s people once welcomed the Romans. Nearly 100 years earlier, when Gaius Julius Caesar made the first Roman foray into Britannia in 55 and 54 BC, the Iceni were among six tribes that offered him their allegiance. But this greatest of all Roman generals was unable to cope with either the power of the coastal tides or the guerrilla tactics of the other Britons who fought him. After negotiating a pro forma surrender and payment of tribute, Caesar departed.

For the next 97 years, no Roman military force set foot on British soil. The Iceni watched as their southern neighbors, the Catuvellauni, grew rich from exporting grain, cattle and hides, iron and precious metals, slaves and hunting dogs to Rome. From Rome, they imported luxury goods such as wine and olive oil, fine Italian pottery, and silver and bronze drinking cups, and they minted huge numbers of gold coins at their capital, Camulodunum.

A century of Roman emperors came and went. Then, in 41 Claudius (Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus) rose to the imperial purple. There were many practical reasons why he might have thought it useful to add Britannia to the empire, one being that the island was an important source of grain and other supplies needed in quantity by the Roman army. Stories abounded about the mineral wealth there. Outbreaks of unrest in Gaul were stirred up — so the Romans believed — by druid agitators from Britannia.

The most compelling reason for Claudius, however, was political. Born with a limp and a stutter, he had once been regarded as a fool and kept out of public view — although those handicaps were largely responsible for his survival amid the intrigue and murder that befell many members of his noble family. Now the emperor desperately needed a prestige boost of the sort that, in Rome, could be provided only by an important military victory. So when the chief of a minor British tribe turned up in Rome, complaining that he had been deposed and asking the emperor to restore his rule, Claudius must have thought it the perfect excuse to launch an invasion.

Boudica would have been about 18 years old in 43, the year Claudius invaded, old enough to be aware of the events that would transform her life. She may already have been married to Prasutagus, but the king of the Iceni was still Antedios, probably an older relative of Prasutagus. Antedios seems to have taken a neutral position toward Rome. Other tribes openly supported the conquest, but most, including the Icenis’ neighbor to the south, did not. Caradoc, king of the Catuvellauni (called Caractacus by the Romans), and his brother Togodumnus led an alliance of tribes to repel the invaders.

When the Roman troops landed at the far southeastern tip of Britannia, Caractacus and his allies harried them as they marched inland. Then the Britons retreated to gather into a single force on the other side of the River Medway. There, the Romans won a major battle in which Caractacus’ brother was either killed or mortally wounded. At that point, Emperor Claudius himself came to Britannia to seal the conquest with a victory at Camulodunum — now known as Colchester — where he accepted the formal submission of 11 British rulers, including Antedios of the Iceni.

Boudica and the Iceni may well have expected the Romans to sail away as they had in the past. They soon learned otherwise. Claudius built a Legio nary fortress at Camulodunum, stationed troops there and established other fortresses throughout eastern Britannia. He appointed the invasion forces’ commander, Aulus Plautius, as Britannia’s first Roman governor. Caractacus retreated westward, recruited fresh troops and continued to fight a guerrilla war against the Romans.

The ham-fisted Ostorius Scapula replaced Plautius in 47. Caractacus timed a series of raids to coincide with the change of governors, so Ostorius arrived to news of fighting. Was it this unpleasant reception that made Ostorius so mistrustful of all the Britons, even those who had surrendered? Or was he short-tempered because he already suffered from the illness from which he would die five years later? For whatever reason Ostorius decided to disarm those subject tribes that he felt he could not fully trust, including the Iceni. Established Roman law forbade subject populations to keep weapons other than those used for hunting game, but that was contrary to Celtic law and custom. The Iceni rebelled, and Ostorius defeated them. Antedios may have been killed in the rebellion. If not, it seems likely that Ostorius removed him immediately afterward and installed Prasutagus as client-king in his place. Boudica was now queen of the Iceni.

Two years later, in 49, Ostorius confiscated land in and around Camulodunum to set up a colonia . This was a town for retired Legio naries, in which each veteran was granted a homestead. The town gave the veterans a secure retirement and concentrated an experienced reserve force in the new province, on which Rome could call in case of emergency. In theory, it was supposed to provide a model of Roman civilization to which the natives might aspire. Unfortunately, the colonia at Camulodunum caused more problems than it solved. As it grew over the next decade, more and more Britons were driven off their land, some enslaved by the veterans, others executed and their heads exhibited on stakes.

The Iceni had once avoided trade with Rome, while the Catuvellauni grew rich from it. Now, the Iceni submitted, while the former king of the Catuvellauni fought Rome, and his people suffered the consequences. Ostorius finally defeated Caractacus in 51 and captured him in 52. That same year, Ostorius died. Rome replaced him with Didius Gallus, who provoked no internal rebellions, though the unconquered western tribes continued to fight.

Emperor Claudius was poisoned in 54, and Nero (Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus) succeeded him. Perhaps to deflect the suspicion that he had been involved in his uncle’s murder, Nero elevated Claudius to the status of a god and ordered a temple to him built at Camulodunum. Now the British chieftains would be obliged not only to worship once a year at the altar of the man who had invaded and occupied their lands, but also to finance the building of the extravagant and costly temple.

Rome further pressed British patience by calling for the repayment of money given or loaned to the tribes. It is possible that Antedios had received some of the money Claudius had handed out, and his successor, Prasutagus, was now expected to repay it. Prasutagus had probably also received an unwanted loan from Lucius Seneca, Roman philosopher and Nero’s tutor, who had pressed on the tribal leaders a total of 40 million sesterces, evidently an investment he hoped would bring a healthy return in interest. Now, the procurator — Rome’s financial officer, responsible for taxation and other monetary matters in Britannia — insisted the money from Claudius must be repaid. And Seneca, according to Dio, resorted to severe measures in exacting repayment of his loans. His agents, backed by force, may have showed up at the royal residence and demanded the money. Boudica would not have forgotten such an insult.

Caius Suetonius Paullinus, a man in the aggressive mold of Ostorius, became governor of Britain in 58. He began his term with a military campaign in Wales. By the spring of 61, he had reached its northwestern limit, the druid stronghold on the Isle of Mona. Tacitus described the forces Suetonius faced: The enemy lined the shore in a dense armed mass. Among them were black-robed women with disheveled hair like Furies, brandishing torches. Close by stood Druids, raising their hands to heaven and screaming dreadful curses. For a moment, the Romans stood paralyzed by fright. Then, urged by Suetonius and each other not to fear a horde of fanatical women, they attacked and enveloped the opposing forces in the flames of their own torches.

When the battle ended in a Roman victory, Suetonius garrisoned the island and cut down its sacred groves — the fearsome site of human sacrifices, according to Tacitus, who claimed it was a Celtic religious practice to drench their altars in the blood of prisoners and consult their gods by means of human entrails. In view of the routine, organized murder of the Roman gladiatorial games, one might wonder whether a Roman was in a position to criticize. Though the Celts did practice human sacrifice, most of their sacrifices consisted of symbolic deposits of such valuable objects as jewelry and weapons into sacred wells and lakes.

For Boudica and her people, news of the destruction of the druidic center on Mona, the razing of the sacred groves and the slaughter of druids must have been deeply painful. But Boudica suffered a more personal loss during this time. Prasutagus of the Iceni died sometime during the attack on Mona or its aftermath. He left behind a will whose provisions had no legal precedent under either Celtic or Roman law. It named the Roman emperor as co-heir with the two daughters of Prasutagus and Boudica, now in their teens. According to Celtic tradition, chiefs served by the consent of their people, and so could not designate their successors through their wills. And under Roman law, a client-king’s death ended the client relationship, effectively making his property and estates the property of the emperor until and unless the emperor put a new client-king into office. Prasutagus’ will may have been a desperate attempt to retain a degree of independence for his people and respect for his family. If it was, it did not succeed.

After Prasutagus died, the Roman procurator, Decianus Catus, arrived at the Iceni court with his staff and a military guard. He proceeded to take inventory of the estate. He regarded this as Roman property and probably planned to allocate a generous share for himself, following the habit of most Roman procurators. When Boudica objected, he had her flogged. Her daughters were raped.

At that point, Boudica decided the Romans had ruled in Britannia long enough. The building fury of other tribes, such as the Trinovantes to the south, made them eager recruits to her cause. Despite the Roman ban, they had secretly stockpiled weapons, and they now armed themselves and planned their assault. Dio wrote that before she attacked, Boudica engaged in a type of divination by releasing a hare from the fold of her tunic. When it ran on the side the Britons believed auspicious, they cheered. Boudica raised her hand to heaven and said, `I thank you Andraste.’ This religious demonstration is the reason some historians think she may have had druidic training.

Boudica mounted a tribunal made in the Roman fashion out of earth, according to Dio, who described her as very tall and grim in appearance, with a piercing gaze and a harsh voice. She had a mass of very fair hair which she grew down to her hips, and wore a great gold torque and a multi-colored tunic folded round her, over which was a thick cloak fastened with a brooch. Boudica’s tunic, cloak and brooch were typical Celtic dress for the time. The torque, the characteristic ornament of the Celtic warrior chieftain, was a metal band, usually of twisted strands of gold that fit closely about the neck, finished in decorative knobs worn at the front of the throat. Such torques may have symbolized a warrior’s readiness to sacrifice his life for the good of his tribe. If so, it is significant that Boudica wore one — they were not normally worn by women.

Tacitus, whose father-in-law served as a military tribune in Britain during that time, recounted the rebellion in detail. Boudica moved first against Camulodunum. Before she attacked, rebels inside the colonia conspired to unnerve the superstitious Romans. [F]or no visible reason, Tacitus wrote, the statue of Victory at Camulodunum fell down — with its back turned as though it were fleeing the enemy. Delirious women chanted of destruction at hand. They cried that in the local senate-house outlandish yells had been heard; the theater had echoed with shrieks; at the mouth of the Thames a phantom settlement had been seen in ruins. A blood-red color in the sea, too, and shapes like human corpses left by the ebb tide, were interpreted hopefully by the Britons — and with terror by the settlers.

Camulodunum pleaded for military assistance from Catus Decianus in Londinium, but he sent only 200 inadequately armed men to reinforce the town’s small garrison. In their overconfidence, the Romans had built no wall around Camulodunum. In fact, they had leveled the turf banks around the Legio nary fortress and built on the leveled areas. Misled by the rebel saboteurs, they did not bother to erect ramparts, dig trenches or even evacuate the women and elderly.

Boudica’s army overran the town, and the Roman garrison retreated to the unfinished temple, which had been one of the prime causes of the rebellion. After two days of fighting, it fell. Recent archaeological work shows how thorough the Britons were in their destruction. The buildings in Camulodunum had been made from a framework of timber posts encased in clay and would not have caught fire easily. But they were burned and smashed from one end of town to the other. So hot were the flames, some of the clay walls were fired as though in a pottery kiln and are preserved in that form to the present day.

The only Legio nary force immediately available to put down the rebellion was a detachment of Legio IX Hispania, under the command of Quintus Petilius Cerialis Caesius Rufus, consisting of some 2,000 Legio naries and 500 auxiliary cavalry. Cerialis did not wait to gather a larger force, but set out immediately for Camulodunum. He never got there. Boudica ambushed and slaughtered his infantry. Cerialis escaped with his cavalry and took shelter in his camp at Lindum.

Suetonius, mopping up the operation on Mona, now learned of the revolt and set sail down the River Dee ahead of his army. He reached Londinium before Boudica, but what he found gave no cause for optimism. Like Camulodunum, Londinium was unwalled. About 15 years old, it had been built on undeveloped ground near the Thames River, by means of which supplies and personnel could be shipped to and from Rome. It was a sprawling town, with few large buildings that might be pressed into service as defensive positions — a smattering of government offices, warehouses and the homes of wealthy merchants. Catus Decianus had already fled to Gaul. Suetonius decided to sacrifice Londinium to save the province and ordered the town evacuated. Many of the women and elderly stayed, along with others who were attached to the place.

Boudica killed everone she found when she reached Londinium. Dio described the savagery of her army: They hung up naked the noblest and most distinguished women and then cut off their breasts and sewed them to their mouths, in order to make the victims appear to be eating them; afterwards they impaled the women on sharp skewers run lengthwise through the entire body.

Verulamium, the old capital of the Catuvellauni tribe lying northwest of Londinium (outside of present-day St. Albans), met a similar fate. Rome had granted it the status of municipium, giving the townsfolk a degree of self-government and making its magistrates eligible for Roman citizenship. Boudica evidently punished the town for its close and willing association with Rome.

By then Suetonius had an army with him amounting to nearly 10,000 men, comprising Legio XIV and parts of Legio XX, which he had used for the attack on Mona, as well as some auxiliaries gathered from the nearest stations. He also sent an urgent summons to Legio II Augusta at Isca Dumnoniorum, present-day Exeter, but its commander, Poenius Posthumus, never responded. Evidently he was unwilling to march through the hostile territory of the Dumnonii, who had thrown their lot in with Boudica, and thereby risk sharing the fate of Cerialis’ men. At the head of his hastily summoned force, Suetonius marched to confront Boudica.

Precisely where they met is not known, but the most plausible guesses — based on Tacitus’ description of the favorable terrain where Suetonius positioned his force — include Mancetter in Warwickshire or along Old Roman Watling Street (now A5) near Towcaster. According to Tacitus: [Suetonius] chose a position in a defile with a wood behind him. There could be no enemy, he knew, except at his front, where there was open country without cover for ambushes. Suetonius drew up his regular troops in close order, with the light-armed auxiliaries at their flanks, and the cavalry massed on the wings. Dio wrote that Boudica’s troops numbered about 230,000 men. If we can believe this, Boudica’s army would have been more than 20 times the size of Suetonius’. Whatever the actual numbers were, it is clear that her forces greatly outnumbered his. But the Britons’ arms and training could not compare to the highly evolved arms and fighting techniques of the Roman Legio ns.

The forces of the Britons, wrote Tacitus, pranced about far and wide in bands of infantry and cavalry, their numbers without precedent and so confident that they brought their wives with them and set them in carts drawn up around the far edge of the battlefield to witness their victory. Boudica rode in a chariot with her daughters before her, and as she approached each tribe, she declared that the Britons were accustomed to engage in warfare under the leadership of women. The picture of Boudica riding about the battlefield to encourage her warriors rings true, but it is unlikely that any Roman understood what she said. She would have spoken in the Celtic tongue and had no need to inform her troops of their own customs. Tacitus puts those words in her mouth as a device to educate his Roman readers about a practice that must have struck them as exotic and strange.

The speech Tacitus reports Suetonius gave may be a closer reflection of what he said, appealing to his Legio ns to disregard the clamor and empty threats of the natives. He told them: There were more women visible in their ranks than fighting men, and they, unwarlike and poorly armed, routed on so many occasions, would immediately give way when they recognized the steel and courage of those who had always conquered them. Even when many Legio ns were involved, it was a few men who actually decided battles. It would redound to their honor that their small numbers won the glory of a whole army.

Legio ns and auxiliaries waited in the shelter of the narrow valley until Boudica’s troops came within range. Then they hurled their javelins at the Britons and ran forward in wedge formation, supported by the cavalry with their lances. The Roman infantrymen protected themselves with their capacious shields and used their short swords to strike at close range, driving the points into the Britons’ bellies, then stepping across the dead to reach the next rank. The Britons, who fought with long swords designed for slashing rather than stabbing, needed room to swing their blades and could not fight effectively at such close range. Furthermore, the light chariots that gave them an advantage when fighting on a wide plain were similarly ineffective, with the Romans emerging from a narrow, protected valley that prevented the chariots from reaching their flanks.

The result was an overwhelming Roman victory. Those Britons who survived ran, but the circle of the women’s wagons blocked their way, causing confusion and delay. The Romans did not refrain from slaughtering even the womenfolk, while the baggage animals too, transfixed with weapons, added to the piles of bodies, Tacitus reported, citing figures of 80,000 British casualties and 400 Roman dead and a slightly larger number wounded.

According to Tacitus, there were at least two notable casualties in the immediate wake of the battle. Upon learning of the victory, Poenius Posthumus felt so dishonored by the failure of his Legio II to have fought its way out to join Suetonius in full force that he committed suicide by falling upon his own sword. Boudica, Tacitus noted, ended her life with poison.

The rebellion was effectively over, but its initial success had shocked Rome. The overall Roman casualties are suggested by the number of troops Nero sent from Germany as reinforcements, according to Tacitus a total of 7,000, consisting of two thousand regular troops, which brought the ninth division to full strength, also eight auxiliary infantry battalions and a thousand cavalry. The civilian dead in Camulodunum, Londinium and Verulamium — some 70,000 if Tacitus’ figure is accurate — would have multiplied the toll. British unrest seems to have continued even after the decisive battle. Dio wrote that the Britons were regrouping and preparing to fight again at the time Boudica died.

When the Roman reinforcements arrived, Suetonius stationed them in new winter quarters. Tacitus wrote that, rather than turning to diplomacy, Suetonius ravaged with fire and sword those he believed to be still hostile or wavering. His punitive policy, calculated to crush the Britons rather than to reconcile them with Roman rule, was consistent with the policies that had caused the rebellion.

On top of that, a famine broke out. According to Tacitus, the Britons had expected to raid the Roman grain stores, and so had mustered all available men into the army and neglected to plant a crop. It is hard to believe an agricultural society, which both depended on grain for its own sustenance and produced it as a major export, would neglect to sow an entire year’s crop. But if they had planted, much of the crop was likely destroyed in Suetonius’ campaign of revenge.

To replace Catus Decianus, Rome sent a new procurator, Julius Classicianus. Tacitus heartily disapproved of Classicianus, sniping that he had a grudge against Suetonius and allowed his personal animosity to stand in the way of the national interest. Classicianus was a Celt from the Roman province of Gaul, and he seems to have done much to calm the angry Britons. He told them it would be well to await a new governor who would deal gently with those who surrendered. Then he reported to Rome that they should expect no end to hostilities unless a replacement were found for Suetonius.

Nero dispatched one of his administrators, a freed slave named Polyclitus, to investigate the situation. Evidently, Polyclitus supported Classicianus’ report. Soon afterward, when Suetonius lost some ships and their crews to a British raid, he was recalled. The new governor, Petronius Turpilianus, ended the punitive expeditions, following instead a policy of not provoking the enemy nor being provoked by them. Tacitus sneered at his slothful inactivity, but he brought peace to Britain.

Of Boudica, Dio wrote, The Britons mourned her deeply and gave her a costly burial. The Roman conquest had brought to the Iceni misfortune that ripened into disaster after their rebellion failed. But as time passed, Britannia became an orderly and respected part of the Roman empire. It remained so for another three centuries. Boudica’s people finally won what it seems they had wanted all along: respect, peace and a government that treated them with justice and honor.

This article was written by Margaret Donsbach and originally published in the April 2004 issue of Military History .

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Military History magazine today!

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

Seminoles Taught American Soldiers a Thing or Two About Guerrilla Warfare

During the 1835–42 Second Seminole War and as Army scouts out West, these warriors from the South proved formidable.

10 Pivotal Events in the Life of Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (1846-1917) led a signal life, from his youthful exploits with the Pony Express and in service as a U.S. Army scout to his globetrotting days as a showman and international icon Buffalo Bill.

Boudica: Warrior Woman of Roman Britain. Women in antiquity

C.t. mallan , university of western australia. [email protected].

It may be reasonably said of Boudica, that never has so much been written by so many about someone whom we know so little. Do we need another book about the chariot-riding virago from first-century Britain? From a strictly academic perspective, one is inclined to say no. However, from a commercial perspective, the answer is patently yes, if the volume of publications, popular or otherwise, which have appeared over the last twenty years is any gauge.

In strictly historical terms the Boudican revolt of 60/61 had little long-term impact. The revolt was, by any estimation, a historical cul-de-sac. Moreover, Boudica’s leadership was a failure, as disastrous for her people as for the inhabitants of the towns her warband destroyed. From what we can tell, the significance of the revolt was chiefly symbolic, confined (for all we know) to the minds of the conquerors, not those of the native population. The brutality of the revolting Iceni and Trinovanti following the sack of Colchester seared itself into the minds of the Romans much in the same way as the Black Hole of Calcutta or the massacre at the Bibighar Well at Cawnpore entered the consciousness of empire builders of a more recent age. Yet, most of all it was the fact that Boudica was a woman that has caught the imagination, from Tacitus, to Dio, to Xiphilinus, to the sculptor Thomas Thorneycroft, to Boudica’s modern biographers, of whom Gillespie will not be the last.

The great challenge facing anyone intending to write a biography of Boudica is the dearth of evidence. 1 Eight pages in Boissevain’s edition of Dio, six and a half in Fisher’s OCT of the Annales , most of it rhetorical in nature, and sundry archaeological material recovered from the Julio-Claudian destruction layers of Colchester, London, and St Albans is not a lot of material on which base a full-length biography. Unlike the revolts of Vercingetorix or Simon bar Kokhbar, we do not even possess coinage that can be tied to the revolt. Gillespie’s approach is to turn the problematic nature of our sources into a virtue by framing her biography of Boudica as “a comparative literary biography of Boudica” (p. x). In practice this means focusing on the role of Boudica in the narratives of the senatorial historians Cornelius Tacitus and Cassius Dio. Gillespie’s approach follows, in essence, that of Marguerite Johnson in her 2012 biography of Boudica for Bloomsbury’s Ancients in Action Series. As a commentary of the portrayals of Boudica in Tacitus and Dio, Gillespie’s work is commendable.

Gillespie begins with a potted history of Rome’s involvement with Britain from Caesar’s invasions of Britain in 55 and 54 down to the suppression of the Boudican revolt. From here, Gillespie turns to the figure of Boudica herself. Here our evidence is particularly sparse, and we are forced to draw on comparative evidence to build up a semblance of the historical Boudica. Gillespie identifies four key components to Boudica’s portrayal in the literary sources, that is as mother, queen, general, and priestess, and structures her biography around these aspects.

The following chapters (3 and 4) focus on the speeches given to Boudica by Tacitus and Cassius Dio. These chapters show Gillespie at her strongest, as she elucidates how the speeches written by the two senatorial historians play up some of the general themes of their works, and their Neronian narratives in particular. For Tacitus, Boudica embodies the familiar theme of the struggle for libertas from the grip of seruitium . Gillespie positions Tacitus’ Boudica in a line of Roman women from Rome’s mytho-historical past who represent catalysts for political change, and suggests that she emerges from the narrative as something of a cross between Lucretia and Brutus. In Chapter 5, Gillespie returns to Tacitus and considers Boudica in relation to the portrayals of other problematic duces feminae in both the Annales and in Latin literature more widely.

As with her discussion of Tacitus, Gillespie’s discussion of Dio is well-executed, especially in Chapter 4, although she shies away from engaging seriously with the problems posed by Xiphilinus’ epitome, upon which we are entirely dependent for Dio’s narrative of the revolt. The speech of Boudica is one of Dio’s great set-piece speeches, and one of several given to women in what survives of his Roman History . 2 Gillespie shows how the speech feeds into Dio’s pejorative assessment of Nero while also utilising innovative literary motifs. It is a pity that Gillespie has little to say about how the speech functions in relation to the three short speeches by Suetonius Paulinus (p. 114-5). Similarly, it would have been welcome had Gillespie offered some thoughts about how the speech of Julius Vindex (also preserved by Xiphilinus) responds to some of the themes present in the Boudica/Paulinus pairing.