- Environment

- Campus Reviews – Inside Dope

- Counsellors

- In Conversation

- Online Education

- Social Issue

- Student Speak

- Study Abroad – Foreign shores

- Career Features

- Out Of The Box Careers

- Young Achievers Prodigy

- Youth Issues

- Current Affairs

- Cover Story

- Love & Dating

- Makeover (Refresh)

- Mental Health

- Model Watch

- Point of View

- Relationships

- Rising Star

- Comic Strip

- Event Diary

- Horoscope – Star Struck

- Recipes – Celebrity Tadka

- Gadgets – Technology

- Nightlife – After dark

- Restaurants – Restometer

Bachelor Of Science In Microbiology: Top Colleges, Fees, Job

Unlocking The Significance Of SEO In Digital Marketing

10 Aeronautical Engineering Colleges In India To Watch Out For

Top Government Jobs For Pharm D Freshers

Ink in Your Veins: Explore Exciting Careers in Publishing

Exploring Career Opportunities at ISRO and Accessible Paths to Space Industry

400 Children Came Together To Reimagine Peace At A Unique Event…

Sustainability Accelerator Programme 2024 For Youth

Global Events To Look Forward To In 2024

Peach Fuzz Is The Colour Of 2024, Use It To Your…

AIESEC In Navi Mumbai Is Conducting Global Village At Nexus Seawoods…

Mastering the Art of Saying No: A Guide for People Pleasers

Top 5 Summer Destinations in India for Refreshing Air

How To Achieve Clean Girl Makeup Look: A Complete Guide

Anxiety Attacks in Confined Spaces: Tips for Coping and Supporting

The Origin Of Pirates

How to speed up recovery after a car accident .

The First-Ever National Creators Award Held In New Delhi

Gen Z Finds Voting Attractive: Here’s Why You Should Vote This…

Five Reasons to Upgrade to iPhone 15 and iPhone 15 Pro…

Hidden Gems: Exploring Emerging Music Genres in 2023

Ten Must-Read Romance Novels: A Global Love Affair

CS2 Server Issues, How to Download, Ranked Modes, and More –…

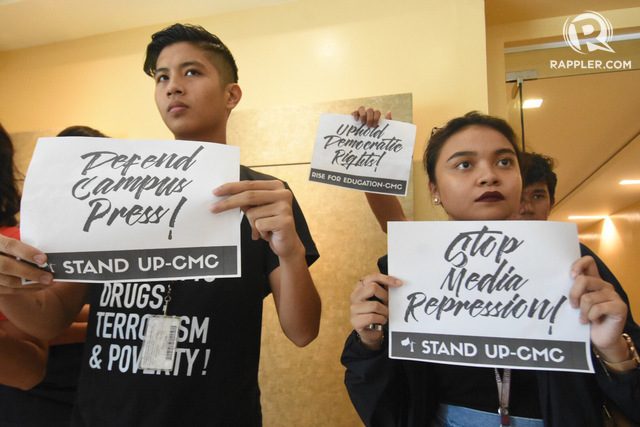

What is campus journalism & why do students need it.

In 1991, the Philippine Government passed the Campus Journalism Act, one of the strongest laws which supports the development and promotion of student journalism, rights of the youth, and preserving the integrity of student publications. The law also states that anyone who obstructs or coerces any student publication and a student journalist shall be penalized.

Since the 18 th century, students raised their voices to demand social and political changes in their universities and countries. They then began to write letters and petitions as a form of protest. By the end of the 19 th century, universities and colleges in the U.S had weekly newspapers and many of them even had dailies. By 1973, more than 1,200 university newspapers had been published

We’ve all been a part of our school/college newspapers or magazines, be it in photos, published articles, essays, and more. However, there is more to it than just commissioning, writing and editing articles, it fosters a sense of liberalism, freedom of speech, the expression of societal issues, and other ‘tabooed’ topics that you won’t find in textbooks. Typically, a campus newspaper or magazine functions exactly how the media is supposed to – reporting the news, help determine which issues should be discussed, and keep people actively involved in society and politics.

Campus journalism exists in three main forms –

- School-sponsored – where the income arrives from university.

- Independent – a student publication not affiliated with the school

- Online – in the form of blogs, podcasts, or PDF copies of printed versions.

It gives students the opportunity to hone and practice their journalistic skills, and be the voice of change by getting readers to think about pressing issues that they probably wouldn’t have read anywhere else. Certain student communities also look to expand their horizons beyond just the campus, and discuss topics such as gender equality, human rights or even the protection of animals.

One of the biggest benefits of campus journalism is that you never get into trouble, unlike the case with mainstream media in society. However, this does not mean that reportage has ‘no limits’. Campus newspapers and magazines have established certain boundaries and authorities can even take action should these boundaries be crossed. An article in Careers 360 says the The Scholar’s Avenue lost it’s funding after publishing a report on the poor condition of the hospital, at IIT-Kharagpur. However, articles that are controversial in nature often get heavy editing or may even be completely scrapped.

Certain campus newspapers are always solely run by the students themselves, they have a presiding faculty member steering the ship. However, this doesn’t mean you will have to filter out your opinions, the faculty’s sole purpose is to serve as an advisor, that will be instrument in establishment and growth. However, being a part of a dynamic team will teach you soft-skills more than any classroom could, like effective communication and management skills.

Campus Journalism does not have to limit itself to the university level, but should also have an important stake at a National level too. Afterall, the youth are the change makers, and will determine he future of any society by formulating, amending, and implementing national policies.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Everything You Need To Know About Building A Career In Ethical Hacking

Exploring High-Demand Careers in the Electronics Industry

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Policy

Scaling New Peaks: Gokyo and Its Trailblazing Founder

InsightOut: The Importance of Student Journalism to Campus Life

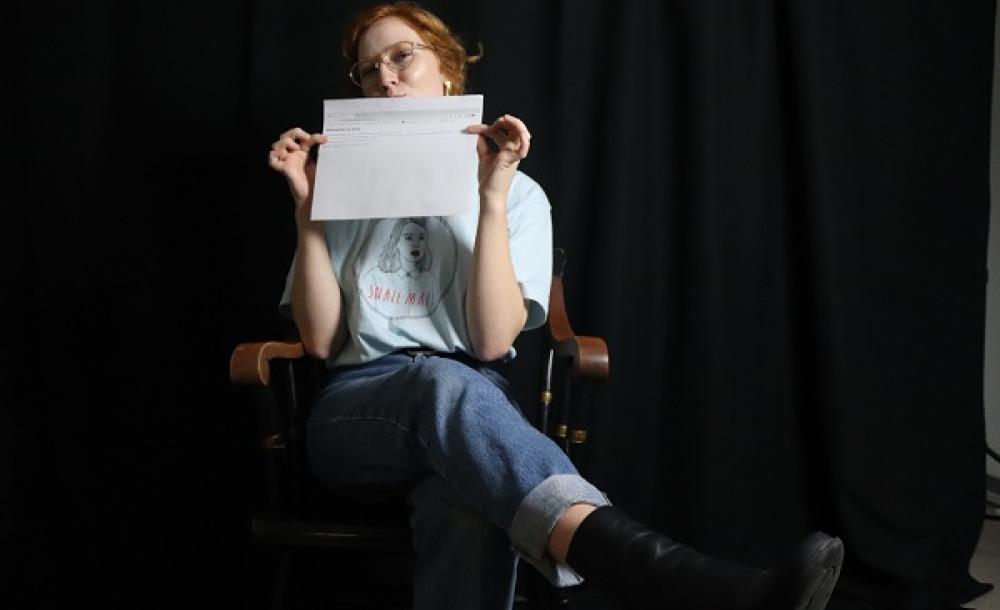

Chiara Greco is a fourth-year student studying Philosophy and English at St. Mike ’ s College. Since her second year she has been involved with student journalism and harbours a deep passion for the field. She is currently the Editor in Chief of The Mike , our official student newspaper.

The Importance of Student Journalism to Campus Life

When I reflect on the importance of student journalism, especially in a time when we have been struck with a global pandemic, my immediate reaction is to create a defence of the field. To rake up all the reasons in my head why student journalism is important and worthwhile. While I can’t be sure where this response came from, I am sure that many people question the choice of being a student journalist—of the added stress without perhaps the large reward or payoff, or even exposure, that professional journalists get in breaking stories. While I’ve been told the career path I have chosen may be a “dying field” I’ve still prospered through my experience and, if anything, this global pandemic has shown me exactly why student journalism is so important.

In a time of social distancing the importance of staying connected through stories, media, and news is so pertinent. Our current global crisis has unveiled the dependence we all have on media and news to connect us. I’ll be the first to admit that virtual living—and learning, for that matter—can be very impersonal, and presents a challenge to most. But the job of student journalists is to bridge this gap between virtual life and ‘normal’ life for students across the university community. Student journalism is a pillar of university life on campus, and with our new-found virtual world, student journalists are those who will form the path towards online community. Stories are the basis of life, the overarching connection we all have to each other, and it is through journalism that these stories get communicated.

While my experience will not speak for everyone, I understand the importance of representing the masses, of being a voice to and for the unheard, and of cultivating a personal experience through our shared stories. Student newspapers like The Mike are an avenue in which this cultivation takes place—and, frankly, it’s hard to imagine university life without student newspapers or the journalists who staff them.

My time at St. Michael’s College has been defined by my involvement with The Mike, starting at the beginning of my second year. From working on the news team to becoming the Editor in Chief, I’ve understood that student journalists have a nuanced responsibility to their peers. We have a responsibility not only to hold our school accountable but also to be a reliable source of student life and news. Integrity, facts, and accountability summarize the three pillars which have come to define my experience of student journalism, and they will continue to guide me through my role with student publications.

Over the summer as I prepared for my role as Editor-in-Chief I faced many challenges in reinventing the paper as an online periodical. The future of The Mike fell into my hands, and while it may have seemed like a large task to take on, especially with the challenges of the pandemic, I was privileged to represent the St. Mike’s community. As I transitioned into my role I began to prepare for things none of my predecessors had to ready for—how to run a printed student newspaper during a global pandemic. With no precedent, changing the course of The Mike meant I had to evaluate the immense role student newspapers have within the university community. To put it simply, without student newspapers one of the most crucial aspects of student life would be taken away. In this way, The Mike ’ s achievements and success translate directly into St. Mike’s overall successes and achievements.

For as long as can be remembered The Mike has delivered students with a print version of the paper across campus newsstands. But the newspaper has been forced to make some hard decisions, such as forgoing our printed paper for now. But since The Mike’s inception our intake of news as students has changed drastically. While an online publication may take away the feeling of holding a physical copy of your work, we now rely more than ever on online avenues to give us news and connection, so The Mike ’ s online home has gone through a complete 180. We’ve changed our website and delivery to allow more students to access and stay up to date with our publication and newsletters.

It is the duty of student journalists to deliver their colleagues’ voices on campus. The importance of cultivating a community across borders is exactly why student journalism is so valuable, because without it the distance between us would be far exacerbated. Student journalists, like professionals in the field, need to become experts on our own community. We need to become a voice for those students who may otherwise not be represented on campus. But this wide range of representation is only accomplished if students contribute their voices. The more voices published in The Mike , the more the diverse and accurate the representation of our community. So while a printed copy of the paper would be an ultimate goal, we have to remember the importance of accessibility and inclusivity when representing the student community. In a time of social distance, it only makes sense for student journalists to present student life as such.

While this pandemic has taught me many things, both good and bad, navigating my role as a student journalist and Editor in Chief of The Mike will perhaps be one of my biggest takeaways. Student journalism is at the heart of every university and college campus. It’s what connects us all.

Read other InsightOut posts .

- Research & Learn

Table of Contents

The role of student publications on campus.

Use: The video adaptation of this lesson and the script can be used during digital or in-person journalism program orientations, class lectures, or as part of remarks while onboarding new student newspaper staff.

- Complete video adaptation for online teaching (length, 5:52)

- Sample remarks for in-person instruction

- Additional resources for students

The Role of Student Publications on Campus: Video Adaptation

Download in-person instructions

Sample Remarks for In-Person Instruction

Student journalists and publications play a vital role in informing their fellow students about campus events, serving as a check on their school’s administration, and uncovering stories that outside media might miss.

With more and more local news outlets shuttering, many college newspapers are the primary source of information about not only what’s happening on campuses but also their surrounding communities.

For example, student newspapers across the country covered Black Lives Matter protests of regional and national significance. From The A&T Register at North Carolina A&T State University to The Collegian at California State University Fresno to The Minnesota Daily (a 121-year old student newspaper) at the University of Minnesota, student publications reported on protests on their campuses and across their surrounding communities, shedding light on alleged institutional racism and civil injustice.

During the pandemic, student publications played a key role in holding administrators and students accountable. For instance, The Michigan Daily exposed a COVID-19 outbreak among the fraternities and sororities at University of Michigan, Arizona State University’s student publication reported on students leaving their dorms while they were supposed to be under quarantine, and the student paper at the University of South Carolina alerted the public to the ways in which the administration was withholding information about COVID-19 clusters.

Moving forward, student media will continue to have an important role to play.

Types of Student Publications

Publications can have a variety of formats, including print and digital newspapers, student blogs, journals, and class publications.

Most student newspapers fit into one of two broad categories: classroom publications and editorially independent publications.

Classroom papers, sometimes referred to as lab publications, are primarily teaching tools for publishing stories, and the work is usually directed, assigned, and graded by a professor. In this kind of class, your professor can exercise their academic freedom to maintain much more control over what is published. That being said, they still must approach grading and publishing in a viewpoint neutral way.

With respect to editorially independent papers (which can be funded either through student fees collected by the university or independent sources) students are responsible for content, sometimes with the guidance of a faculty member or an advisor. These advisors act as sounding boards when brainstorming stories, share institutional knowledge, provide advice on ethical issues, and make sure student journalists’ rights are being respected. At public schools and at private schools that commit themselves to free speech, administrators and faculty cannot dictate what can and cannot be published.

In regard to funding, student publications have the same rights as any other recognized student organization. Administrators and student governments must be viewpoint-neutral when making funding decisions. For example, a school cannot deny or rescind funding based on reporting that represents the school in a negative light or angers alumni and donors.

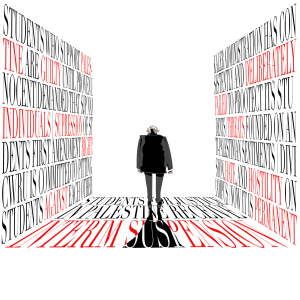

Protecting Your Rights as Student Journalists

Student publications are protected by the First Amendment at public universities. At private universities, their treatment should be consistent with university policy—which, at most private schools, clearly expresses a commitment to freedom of speech, if not freedom of the press specifically.

Despite robust protections for student journalists, some colleges have attempted to censor or punish student publications, particularly when student journalists have been critical of the administration or have written about topics the administration finds objectionable.

Among some of the tactics administrators have used to silence journalists are defunding a publication, using the threat of an investigation, insisting on prior review before publication, and putting pressure on journalists and student media advisors to steer coverage.

Having a recorded or written record is key to pushing back against censorship. If anyone does try to silence you, utilize your reporting skills to make sure you maintain a record of communication and alert your advisor.

Other students, university staff members, and sometimes even administrators, have been known to steal or destroy free papers distributed on campus for publishing unpopular opinions or unfavorable coverage. This kind of action is vandalism or theft and should be treated and reported on as such.

The best way to protect against censorship, particularly administrative censorship, is to know your rights and make sure your reporting is ethically sound. Good journalism practices should already avoid the kind of unprotected speech, such as obscenity or defamation, that a school might try to use to justify interfering with student editorial judgment.

Be clear with sources about what is on and off the record, make sure you know your state’s laws regarding recording conversations, and always try to clearly identify yourself as an on-duty reporter when attending events you’re covering.

Student publications play a vital role in informing students about events and occurrences on campus, exposing wrongdoing, holding leadership accountable, and informing the larger community about relevant events. In order to perform these important services, publications should be autonomous and free from editorial interference or censorship by administrators.

Additional Resources for Students

Student Press Censorship — What Does it Look Like?

Under Pressure: The Warning Signs of Student Newspaper Censorship

A Citizen’s Guide to Recording the Police

Student Press Law Center’s Public Records Letter Generator

- Share this selection on Twitter

- Share this selection via email

- A timeline of CWRU and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict March 22, 2024 • Zachary Treseler , Shivangi Nanda , and Darcy Chew

- Students for Justice in Palestine receives interim suspension following alleged violation of CWRU’s Code of Conduct March 14, 2024 • Téa Tamburo , News Editor

- SpectrumU, CWRU’s cable-streaming service, available to students March 1, 2024 • Zachary Treseler , News Editor

The Observer

The importance of student journalism

Beau Bilinovich , Development Editor September 30, 2022

As staff members of The Observer, we like to tout ourselves as the voice of the student body. We are the platform for students from all walks of life and backgrounds, allowing all to share their stories and ideas with the campus community. But what does it actually mean—the voice of the student body? Why does what we, as student journalists, do matter? What’s the point, anyway?

Being a writer, I sometimes ask myself those questions. Whenever I write an article, I feel as if I’m just sending it off into the silent void where, save for a few of my family members (who are awesome), no one truly cares. Of course, that isn’t true. The conversations we as writers create with the community of Case Western Reserve University and the surrounding Cleveland community are important. It’s one of the ways we connect with the people around us.

So what do we gain from student journalism?

Student journalism can act as a model for the real world, where people can freely and openly discuss ideas, debate and point to the problems that need to be addressed. As opposed to state or even federal politics, schools offer a smaller, more confined community. It’s easier to see the effects of a change in, for example, university policy, since we are around each other all the time and see the direct effects immediately. When we familiarize ourselves with campus-wide issues, we can learn to understand strategies for resolving them.

That skill—figuring out how to resolve conflicts—is needed now more than ever. 60% of rural youth and 30% of urban youth live in “civic deserts,” where limited opportunities are available to meet people, discuss issues and address problems. Trying to cure the maladies that plague the country nationally is hard enough. But by engaging in conversations on the campus level, students can more easily meet and find solutions to the issues specific to a school’s community.

For us at CWRU, that means calling to attention when the administration has an inadequate response to changes in housing policies, as happened last semester, or to the violent crimes that frequent this place we call home—issues that we are all too familiar with. For students at Virginia Commonwealth University, that means being on the front lines and covering police brutality protests. And countless school papers reported on the pandemic and its effects on the student body, including ourselves.

Hence by working together to figure out solutions to the problems affecting the campus community, we can build bridges. Figuring out solutions forces us to see each other. It brings the community closer together. This connection is valuable—especially since we as young adults were affected the most by loneliness and social isolation due to the pandemic.

Student journalism also enables young Americans to have their voices heard, broadcast and uplifted. Much of the political power in this country is held by older Americans: The average ages of members of the Senate and House of Representatives is 62.9 years and 57.6 years, respectively. President Joe Biden is currently the oldest president in history at 79 years old. Moreover, voter turnout for younger Americans in 2020 lagged behind older Americans by about 25%.

Seeing so much authority in the hands of only a fraction of the U.S. population can feel crushing. The connection that student journalists have with their community can help to mitigate these feelings and give young voices a sense of validity, especially when our concerns are often silenced.

No student newspaper is at the same level as The Washington Post or The New York Times. We aren’t Daniel Ellsberg uncovering classified government documents detailing two decades’ worth of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam, but our work still has value in its own way. But as a student newspaper, we do cover issues personal to us, the student body. We shine a light on the issues that large media outlets might not pick up on, the issues that we have to face every day on campus. That’s what truly matters.

So that is what it means to be the voice of the student body. It’s not that we speak for all students, but rather that we bring conversations forward and unite together to determine how we can change this university for the better. Obviously, no writer can speak for every individual; differences in values make this near impossible. But we can share in a common understanding that CWRU, and all other universities, should be places for students to thrive.

Beau Bilinovich (he/him) is a fourth-year student majoring in aerospace engineering. When not struggling to turn in his homework at the last minute, he...

LTTE: An open letter to President Kaler and Provost Ward

Editorial: By suspending SJP, CWRU’s administration furthers a culture of distrust

Are sports stars and celebrities really overpaid?

After LeBron left: Where the Cavaliers stand in the wake of LeBron James’ departure

Editorial: CWRU falls out of top 50 in university rankings, but this didn’t have to happen

A timeline of CWRU and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict

Is CWRU "A sound investment?"

Students for Justice in Palestine receives interim suspension following alleged violation of CWRU’s Code of Conduct

"The Marvels": MCU Phase 5’s highly anticipated trio

America and CWRU's parking problem

Caitlin Clark: We know her, we love her but we just can’t pay her

Laughter is the best medicine: Why every CWRU student should attend stand-up comedy shows

How redefining body positivity can lead to happier and healthier lives

America and CWRU’s parking problem

Eclipsed by clouds: It is too soon to get hyped

Why reading hard books is important, despite how difficult it can be

Beyond the bin: A new approach to dining hall food can help reduce food waste

84% of CWRU undergraduate students are involved in research: What’s the big deal?

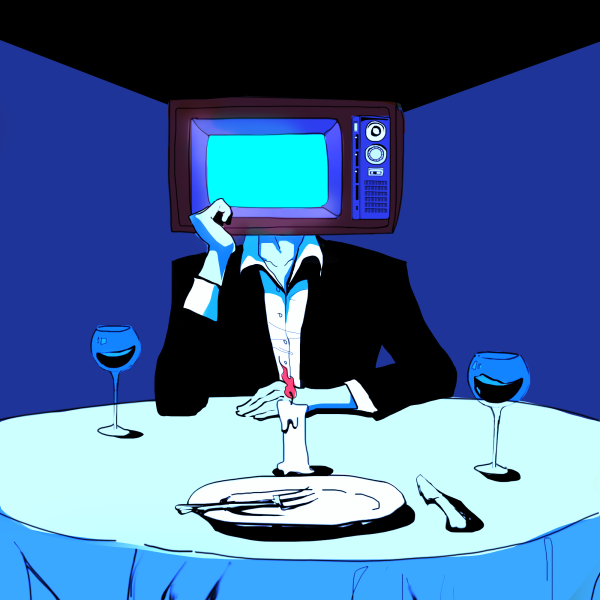

Entertainment tech is too good for our own good

Humanities write essays, but STEM fills in bubbles—this is a problem

- The State of CWRU

- Faculty Insight

- Inside the Circle

- Outside the Circle

- Clubs & Organizations

- Film and Television

- Local Events

- What to do this Week

- Climate Action Week Essays

- Letters to the Editor

- Editor’s Note

- Cleveland & National Sports

- Fall Sports

- Winter Sports

- Spring Sports

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Sunday March 31, 2024

- Book Review

- TBS Graduates

- Climate Change

Related News

- Cook your career to perfection as a chef!

- When can I get off the ‘adulthood’ roller coaster?

- BGMEA to host career summit for university graduates

- Being a carpenter of words...

- Your university is the cornerstone of your career

Campus journalism: A stepping stone for future professionals

An increasing number of university students are taking up campus journalism gigs despite not having a formal journalism background.

Between 2007 and 2011, Rajib Nandy, a dedicated student of Communication and Journalism at Chittagong University, emerged as a formidable force as he took on the role of a campus correspondent for two national dailies. Undeterred by the absence of a salary, he fearlessly covered a wide spectrum of campus events, exploring politics, crime, education, health, culture, research and more.

Rajib left no stone unturned in his journalistic pursuits, crafting several exclusive stories.

Notably, he revealed a shocking tale, exposing the construction of an opulent rest house for a then-president of the country, concealed under the guise of the university's convocation preparations, with a staggering cost of over Tk1 crore.

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

But there's more to his own story. As a campus journalist, Rajib had to overcome many challenges. In 2009, when he was a third-year student, a defamation case was filed against him after he broke another exclusive story about some allegations made about a professor at the university.

At that time, Rajib worked for Samakal and armed with solid evidence in the form of documents, he received unwavering support from his editors. After enduring a year and a half of legal battles, he emerged victorious in the defamation case.

In 2010, he also covered the exclusive story of the world's last amphibious species, Fejervarya asmati. Rajib's exceptional work earned him the recognition of his editor, who doubled his salary as a testament to his remarkable talent.

Amid all this, Rajib maintained his grades and found a way to be the top student for the four years of his bachelor's degree.

Now he is an assistant professor in the same department. Besides teaching, he is also a researcher and contributes news and opinion pieces to several media outlets in Bangladesh and India.

To Rajib, campus journalism is a stepping stone for future professionals.

"The experience of student journalism can be a great benefit, whether they [students] keep working in journalism after graduation or switch to other fields like communication, public relations, administration, research or teaching," he says.

"To become a campus journalist, it is important to have good news sense, an ever-curious mindset, and the ability to tell a story engagingly, irrespective of the medium," Rajib adds.

Current scenario of campus journalism

An increasing number of university students are taking up campus journalism despite not having a formal journalism background. This surge is driven by the high demand for campus journalists within the dynamic media industry.

Student politics have always been of great interest to Bangladeshi audiences, and anything affecting university students is inherently linked to the well-being of the entire nation.

"And now that there are so many new newspapers, TV channels and online portals, university students are getting more opportunities to become campus journalists than before," explains Sirajul Islam Rubel, former general secretary of Dhaka University Journalists Association.

Nishat Parvez, an assistant professor of Journalism and Media Studies at Jahangirnagar University, also believes that campus journalism has been thriving for quite some time now.

"In recent years, campus journalists have been very active. At Jahangirnagar University, they are unearthing administrative corruption, ragging, environmental pollution, problems of the students and several other issues through their reports and pushing the authorities for change," she says.

However, one major complaint is that campus journalists are brutally underpaid. Most begin their careers without any salary, especially when working for online portals or relatively unknown media houses. Even when appointed by leading media houses and brought under the payscale, monthly salary rarely surpasses Tk15,000.

Perks of becoming a campus journalist

The biggest advantage of being involved in campus journalism lies in the fact that it prepares one to become a full-fledged journalist later on in life.

Suzon Ali, former president of the Rajshahi University Journalist Association, majored in English Language and Literature. But thanks to his experience as a campus journalist, he has become the Rajshahi district staff correspondent for New Age. "Had I waited for my student life to be over and then joined any media house to pursue my dream, it would have made my journey much harder," says Suzon.

According to Shabnam Azim, associate professor of Mass Communication and Journalism at Dhaka University, the current curriculum covers everything a student needs to become a journalist.

Still, she believes that the practical application of theoretical knowledge always helps. So, teachers always encourage students if they pursue a part-time career in campus journalism.

"It provides the students with valuable experience," Shabnam says.

Manjur Hossain Mahi, a third-year student of Mass Communication and Journalism at Dhaka University, shares the same perspective. While acknowledging that campus journalism does not bring him significant financial rewards, he views the time invested in this profession as a valuable investment.

As a campus journalist, he is expanding his network by getting acquainted with new people, visiting new places and sharpening his communication skills.

Additionally, he can also keep a tab on current affairs.

The preliminary test of the 45th BCS took place in May, and Mahi claims he was familiar with most of the general knowledge and current affairs questions. "Because I covered some of those stories myself!" he says.

Campus journalism also provides students with a respectable identity and brings them closer to their teachers.

"Most people on the campus keep us in high regard, and teachers also pay extra attention to us," says Shakil Hosen, a third-year student of Political Science at the same university, who has also taken up the role of a campus correspondent for Dhaka Times.

Some argue campus journalism has lost its spark. One of them is Badruddoza Babu, a leading investigative journalist of the country who also teaches part-time at Dhaka and Jahangirnagar universities.

In the early 2000s, during his student years, he made his mark in journalism while working for the prestigious weekly magazine Shaptahik 2000. His captivating coverage of Dhaka University included a groundbreaking exposé on concealed firearms found within the residential halls.

But he thinks such news coverage in recent times has become few and far between.

"There was a time when a campus reporter had at least one front page lead in the national dailies every month. But lately, I do not see much in-depth reporting by them, as they often remain preoccupied with covering trivial events and political press conferences," he says.

Campus journalism has other challenges too.

Foremost, it is almost like a 24/7 job, and a campus journalist always has to be on their feet, if need be. And that can hamper one's study.

"Sometimes after a long day's work, I sit down to grab a meal, but suddenly my phone rings and I hear something big is happening on campus. At that point, I must run immediately to cover the news, even if that results in my studies getting compromised," shares Mahi.

Meeting deadlines also takes a huge toll on them. They are asked to submit a piece of news by 6:30 pm. But some events take place after the time frame. Then they face the challenge of submitting the news by 10 pm for the second edition.

Being a journalist can also put students up against the administration and student wing of the ruling party. "I faced threats of getting jailed several times because I tried to bring up the truth, which didn't go well with the people of the administration and the ruling party," says Suzon.

There have even been several reports of campus journalists getting physically assaulted while simply trying to do their job. Sometimes it also becomes challenging to gather information from the higher authorities.

In many cases, reporters are asked to apply through the Right to Information Act. But that is a very complex and time-consuming process, and campus journalists cannot afford to wait that long for one story.

"So, it is better to establish reliable sources among the higher authorities so that we can gather necessary information quickly," says Mahi.

Shabnam also admits that campus journalists have to weather pressures from different sectors. "There are many risks for them. But my advice for them would be: never surrender to power or lose objectivity, rather try to handle every situation technically."

Meanwhile, some students also lose interest in the job after a certain period and decide to switch to another profession.

"But I think it's good that they are making up their mind while they're still young. Campus journalists are exposed to the harsh realities of life sooner, so they have plenty of time left to pursue something else," says Rubel.

What opportunities are there for female students?

Female students are still reluctant to become journalists, notes Nishat Parvez. "Recent studies suggest the number is even lower in the management level than the entry level," she adds.

Jakia Jahan, a lecturer of Mass Communication and Journalism, attributes religious fundamentalism as well as women's communication apprehension and lack of interest in the profession to the low rate.

However, a handful of female students are showing enthusiasm to become campus journalists nowadays.

Autoshi Sen, a second-year student of Mass Communication and Journalism at Dhaka University, is the first female student from her department to become a campus journalist.

"It was far from easy. Many doubted my abilities and said I wouldn't be fit for the job. I got a job from Naya Shatabdi, a relatively new newspaper. Though I have already proved my worth, bigger media houses are reluctant to offer me a job," says Autoshi.

Authoshi had to face harassment several times for being a female reporter. Many people are still not ready to accept that female journalists can work and compete neck and neck with their male counterparts.

However, thanks to her role as a campus journalist, Autoshi has recently got the opportunity to become a presenter at Bangladesh Television. She expects that following in her footsteps, more female students will become campus journalists.

Marjan Akter, a Master's student of Communication and Journalism at Chittagong University, shares a similar experience as she serves as a campus correspondent for Samakal.

From her family to her surroundings, everyone was sceptical. They said it's not a women's job. The campus is one hour away from her home in Chattogram, and they asked how she could attend events that are taking place in the evening.

Marjan also had to face harassment from the student wing of the ruling party once when she went to cover one of their events.

"But after doing this job for one and a half years, I have become more confident and mentally stronger than ever," says Marjan.

Career / Campus Journalism

While most comments will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive, moderation decisions are subjective. Published comments are readers’ own views and The Business Standard does not endorse any of the readers’ comments.

Top Stories

MOST VIEWED

How 'Italy fever' burns and builds Madaripur

The ‘nomadic’ watermelon farmers of char kakra.

The migrant buffalos of haor

Where to buy Eid shoes from?

More videos from tbs.

Alonso slipped, who is taking charge of Liverpool?

India-US relations strained over Kejriwal issue

Patenga Container Terminal set for April start

The military was behind spreading Rohingya hatred on Facebook: UN

Journalism Ethics 101: A Survival Guide for Student Journalists Navigating a Shifting World

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Focus Areas

- Journalism and Media Ethics

- Journalism and Media Ethics Resources

- Ethical Considerations for Student Reporters, Editors, and News Consumers

10 Ethical Guidelines for Student Journalists

Delaney Nothaft was a 2019-2020 Hackworth Fellow at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics.

A free press is essential to informing the public, speaking truth to power, and connecting people with their communities — including college campuses. Student journalism has grown in importance for college communities that are now often dispersed across the country and globe due to social distancing. At the same time, many student journalists and student editors struggle with uncertainties about how to report ethically, which often stem from their professional inexperience, competing interests, and a wish to fit in with their peers. The 10 ethical guidelines for student journalists are designed to help journalists of the future not only make it through their immediate deadline, but also safeguard democracy and foster social cohesion with their reporting.

First, let’s address a few preliminary questions you might have:

Why do college newspapers matter?

College newspapers are training grounds for journalists of the future — a future in which truth itself is under assault and democracy is more imperiled than ever. In order to preserve the press and freedom that empowers it to speak truth to power, we need to equip student journalists to confront the challenges faced by professional journalism.

Are college newspapers any different from regular newspapers?

Yes. Student journalists are immersed in the communities they report on, and while that gives them access and insight, it also requires systems and procedures to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. Furthermore, student journalists are often beholden to authority figures who control their budgets and may seek to influence coverage and limit criticism. Such power imbalances and conflicts of interest, combined with student journalists’ relative inexperience, are a recipe for a journalism environment riddled with ethical potholes.

Why do student journalists need a particular set of ethical guidelines?

A college campus is a unique community with its own structure, policies, power dynamics and stakeholders. The role of the student press requires it to hold accountable the same powers that provide its funding — a scary position for any journalist to be in, never mind a college kid trying to fit in and make the grade. It’s a difficult environment in which to take a principled stand, or to even know what the principled stand is, and ethical resources can only help!

As a Hackworth fellow in 2019-2020, I set out to research ethical issues in college newspapers. During fall quarter, I conducted ethnographic observation of SCU’s campus paper, The Santa Clara (TSC), as well as several interviews with the newsroom staff, and a thematic analysis of TSC content, along with outside research on student newspapers from around the country. Under the direction and guidance of Dr. Anita Varma (assistant director of Journalism & Media Ethics at the Markkula Center), I developed 10 ethical guidelines for student journalism to prioritize.

1. Treat people with dignity and respect

Journalists, and reporters in particular, are often the “butt” of late night talk show jokes, where they are portrayed as “pushy” or “sensationalizers.” These jokes are funny because there is a layer of truth to them – there are some journalists who are willing to go to extreme lengths to get the story. Don’t forget, though, that you can get the story while treating everyone with dignity and respect. A “good story” doesn’t justify causing harm to those in your path. This includes everyone you interact with: all the stakeholders in the story, your colleagues, and the community as a whole.

It’s important to note that you can still hold people accountable while still treating them with respect. In fact, holding people accountable is respecting them – you are respecting their autonomy as individuals making decisions. A tough question is not inherently disrespectful. Treating people with dignity and respect means being accurate in your portrayals, giving people an opportunity to respond, and being sensitive to sources’ vulnerabilities and needs.

For example, before labeling anyone, the newsroom should check to see if that label would cause significant psychological harm to a source or the source’s community. What is your news organization’s style when referring to students’ immigration status? If you’re unsure, consult with advisors and members of that stakeholder group. They are the best experts.

If you’re a student editor, be sure you respect student reporters’ dignity as well. It is good practice to consult the reporter when making edits that have to do with clarity of the content. Reporters are held accountable by the public, which is a good thing – but editors should also make sure that the content they are going to be held accountable for is what the reporter intended.

2. Identify and acknowledge all stakeholders

Striving for truth can be complicated. The implications of a particular event or issue are often difficult to comprehend or anticipate if you’re covering a story for the first time. A good starting point is to identify as many stakeholders as possible. Remember, your scope can always be trimmed later, but by starting broad you are less likely to miss things. However, it is important to note that you should not amplify a voice that will inflict psychological or physical harm on the community. Giving a voice to a White supremacist or a conspiracy theorist with unfounded arguments doesn’t do anything to serve the community or truth-telling.

Furthermore, not all voices should be given equal weight. There is often an assumption that journalists should be neutral. However, the truth is rarely neutral. For example, some may argue that when reporting on a racist event, it would “violate neutrality” to use the word “racist” — even when there is an empirically demonstrable pattern of racist behavior at hand. Similarly, it is unethical to prioritize neutrality in the face of basic human rights violations.

It is the role of journalists to inform the public about what is happening, not to couch reality in jargon or sugar-coat with euphemisms to avoid controversy which can be misleading or even deceptive. When, for example, acts of racism are empirically substantiated, don’t use softened phrases like “racially charged.”

3. Provide context

I offer an analogy for the importance of context:

A man eats an apple.

A man eats the first fully synthetic apple.

A soldier eats the first fully synthetic apple designed to increase strength and repair injuries, making him invincible.

Facts mean nothing without context. This is a goofy example, but the point is that journalists must make context decisions that can drastically change the meaning of the story. Take this more serious example:

A man was shot.

A man was shot by police officers.

A Black man was shot by police officers in Phoenix, a city that was still reeling after the death of another Black man shot by officers two weeks ago. Both victims were unarmed.

Ask questions like these until the context becomes clearer:

- What is happening, and why is it happening?

- Who are the people involved?

- What is their history?

- What is the history of events like this? Is it significant?

- Is there statistically significant data?

- Which stakeholders should I talk to for a better grasp on this?

- Ask your sources, “How do you know that?”

4. Emphasize equity

One of the fundamental missions of a newspaper is to give voice to the voiceless. Knowledge is power, and by sharing stories you may be able to change hearts and minds. It’s important to choose these stories wisely. Whose voice should be elevated, and why? Here are some important questions to consider:

- Are people suffering?

- If so, why are they suffering?

- Is someone inflicting the suffering?

- Is their suffering visible?

- Are fundamental human rights being violated?

- Are the people who are suffering marginalized, meaning they are prevented from full civic participation?

- Could this story advance an “us versus them” narrative that will further stoke division? How might you avoid this trope?

5. Practice courage and prudence

Journalists have a duty to report the truth so that the powerful are held accountable and the public can make informed decisions. Journalists should perform this duty with both courage and prudence. Courage is doing the right thing even if you’re afraid. Courage for a journalist can mean putting yourself in jeopardy of physical harm, but it also includes moral, intellectual, emotional, social and psychological bravery. It takes courage to face hostility or ridicule from readers and authorities. Prudence is being reasonable and not reckless. To practice prudence as a journalist means you are careful and use sound judgment.

An example of a virtuous journalist is Marty Baron, the current editor of The Washington Post and the former editor of The Boston Globe. He led the newspaper and the “Spotlight” team that investigated the Catholic church for covering up and protecting priests who were abusing children. He showed courage when he took on the Catholic church. And he was prudent – he required irrefutable data and source testimony because he didn’t want to leave the story open to accusations of rushing to judgment.

6. Be rigorous editors

Rigor makes people better at everything they do. The editing process is crucial for ensuring rigor in student newspapers since student reporters are still cultivating their skills. Here are a few suggestions for editing policies:

- In a student setting, editors are often also reporters, and they are still learning themselves, so the more eyes on a story the better. Consider editing horizontally, in addition to vertically.

- Make reporters aware of edits, even if they are not present on production night.

- Consider requiring at least two drafts of a story.

- Remember, the more eyes you have on a story, the higher the odds become that mistakes will be caught and corrected prior to publication.

7. Engage the community

The newspaper exists to make the community better, so input from the community is essential. It is vital to ask what is important to your audience to gain insight as to what is going on in the community and why it matters. Being open and accessible will build trust, which will lead to better relationships, which will lead to better leads and better stories. Remember to prioritize dignity and respect — don’t make enemies with the community. If you’re not trusted, your work means nothing. Be collaborative. Aspire to make a positive difference in the lives of all the people who comprise your college community.

8. Strive for accuracy

Journalistic credibility is derived from accuracy. Journalism has been described as presenting “the facts” and also “the truth about the facts.” A commitment to accuracy is essential and requires rigorous examination and enforcement. Here are some guideposts as a starting point:

- Seek and prioritize first-hand sources.

- Double-check facts and keep a record of how you have verified those facts.

- Confirm claims with at least two sources.

- Ensure facts are presented in context and are true to their intended meaning.

- Don’t allow deadline pressures to compromise standards.

- Don’t give credence to people you know aren’t being honest by including their quotes. University officials may make false claims – that doesn’t mean you have to amplify them uncritically.

- Challenge your assumptions and have an open mind.

- If you feel emotionally invested or emotionally divested in a story, acknowledge those feelings and seek feedback to ensure you’re including relevant perspectives.

- Be transparent and show your work.

- Don’t be fooled by increasingly sophisticated digital manipulation. Remain skeptical (even/especially if an image has gone viral on social media) and seek verifiable evidence.

- Headlines, cutlines and display text must share accuracy standards.

- Admit your mistakes and correct them.

9. Actively diversify the newsroom

In a close-knit college community, it can be tempting to suggest your friends join the school newspaper with you. Friends can bring out the best in us, but they can also cloud our judgement (you may look at them through “love eyes.”) Friends may be less afraid to call you out — or they might not call you out because they want to preserve the friendship. This is problematic for accountability, and can worsen blind spots in newsrooms. Of course, it’s not a bad thing to be friends with your coworkers. Just be cognizant to encourage people of all different backgrounds and opinions to join the newspaper, even if your social circle is mostly homogenous. Diversity strengthens journalism.

10. Demand & model a culture of organizational integrity

Organizational integrity means creating a climate that aligns values, attitudes, language, and behaviors with ethical principles. In other words: talk the talk and walk the walk of ethical journalism. Being insensitive or indifferent to potentially harmful behaviors is indicative of a culture that lacks integrity. To bring this full circle – each member of the newspaper has a responsibility to cultivate a culture that values dignity and respect for community members and for each other.

- The Board of Regents

- Office of the University President

- UP System Officials and Offices

- The UP Charter

- University Seal

- Budget and Finances

- University Quality Policy

- Principles on Artificial Intelligence

- UP and the SDGs

- International Linkages

- Philosophy of Education

- Constituent Universities

- Academic Programs

- Undergraduate Admissions | UPCAT

- Graduate Admissions

- Varsity Athletic Admission System

- Student Learning Assistance System

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Academics and Research

- Public Service

- Search for: Search Button

Democracy and Disinformation: The role of campuses, campus journalism, citizen journalism and fact-checking in the struggle for democracy

“A large part of the struggle to keep democracy alive in this country—in any country—will be the struggle to keep our campuses free.” Such were the words spoken by University of the Philippines Visayas (UP Visayas) Chancellor Clement Camposano at the 3rd National Conference on Democracy and Disinformation, hosted this year virtually by UP Visayas.

For Camposano, colleges and universities, particularly UP, have become the subject of disinformation campaigns on social media. He characterized the attacks on the platforms as a vilification campaign, which not only poses a challenge to members of the university community, but also to the country’s democracy at large. “The University is under siege because there is a campaign of vilification against it, a campaign intent on portraying our campuses not only as breeding grounds of radicalism. . . but also as safe havens for enemies of the state,” he added.

Speaking to an online audience largely composed of the academe, particularly campus journalists, the chancellor underscored the role of campus journalists in challenging disinformation, particularly among members of the university community. “To keep democracy from breathing its last, we need to keep our campuses alive. Alive with ideas, with disputations, with political dreams of all sorts. Alive with politics, broadly construed,” he said.

Disinformation and government accountability

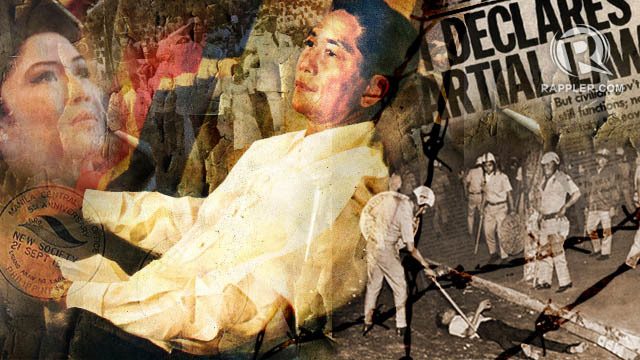

Speaking of campus journalists, Senator Risa Hontiveros underscored their role in the fight against the dictatorship of President Ferdinand Marcos. She particularly highlighted the Philippine Collegian and its editor Abraham Sarmiento, Jr., quoting his words, “kung hindi tayo kikilos? Kung hindi tayo kikibo, sino ang kikibo? Kung hindi ngayon, kailan pa?” which were a challenge to fellow students to stand for freedom of speech and democracy.

Hontiveros also recalled how the Marcos dictatorship immediately closed down media organizations after proclaiming Martial Law, resulting to the growth of clandestine media organizations which would later emerge during the 1986 People Power Revolution. “The role of the media in protecting our democracy cannot be understated,” she said, mentioning its role as providing check and balance of government, acting as the virtual 4th branch of government.

The former broadcast journalist also paid tribute to local media organizations all over the country, including regional newspapers in the Visayas and Mindanao, whose relentless reports on the pivotal moments during Martial Law aided in the fight against state-sponsored disinformation and the restoration of democracy. “The Filipino media’s courage and ingenuity paved the way for more and more Filipinos to know the truth. For more Filipinos to wake up from a deep, deep slumber,” she added.

The senator also emphasized how the media plays an important role in providing the public with information which serves as the baseline of facts, from which people of different persuasions can have a rational discussion. “Without media, and if all we’re fed is propaganda or dis- and misinformation, this can polarize societies and skew public debates,” she said. She said that this lack of a common set of evidence-based facts will not only mean distortions of reality, but it will also make government accountability impossible.

Speaking likewise on the accountability of government, Rappler Chief Executive Officer Maria Ressa said it was important for people to have accurate information from the media, as it will enable them to demand accountability and transparency from their government. “If we don’t have facts, we can’t have a shared reality and we cannot hold government to account, protect our rights, and protect our democracy,” she said.

Ressa, who has been the subject of several law suits regarding the ownership of Rappler and a supposed libelous news article against a businessman, views the charges against her as harassment of the media by the Duterte administration. She has been the subject of disinformation efforts by trolls on social media with the use of memes, altered images and misquotes. She has also been threatened by dubious social media users via messages and comments. “We have been demolished. We have been attacked, like Leila de Lima. Like Leni Robredo. We have been ridiculed. We have been dehumanized,” she said.

Aside from threats against journalists, Ressa also highlighted how social media platforms in recent years have been used to disseminate false information on the Marcos dictatorship. Coupled with constant attacks on journalists and media organizations, these are intended not to disprove what one already knows and has learned from studies, but to sow doubt. “The goal is not to make you believe something, although they seed a metanarrative for it. But the goal is to make you doubt everything. Because if you don’t trust anyone, then you’re not gonna do anything,” she added.

Citizen journalism and newsrooms

Also speaking on the role of citizens in exacting accountability in governance, the former head of ABS-CBN Bayan Mo iPatrol Mo , Inday Espina-Varona, said social media have over the years, become platforms where aside from personal rants, users can share issues of public concern. She is however careful to distinguish a citizen journalist from an ordinary social media user. “When you say you are a citizen journalist, you may not be a professional practitioner of journalism, but you report with the basics of journalism,” she said. That would include sharing accurate information and unadulterated multimedia materials like videos, audio materials or photos, to news organizations.

Emphasizing the importance of facts, the veteran journalist said one does not need to be a journalist to have the obligation to respect the truth. She even highlighted how one well known pro-administration blogger excused herself from being factual in her online postings by saying she is not a journalist. “You don’t need to be a journalist to be able to appreciate the need to be loyal to facts,” she said.

Aside from respecting facts, Varona said social media users, particularly citizen journalists, must also adopt journalism ethics in posting information online. This, along with loyalty to facts and training from news organizations, would be important skills in documenting and reporting social and political events. And speaking from her experience, she shared how enthusiastic ordinary citizens were in learning about the basics of journalism, enabling them to share stories of their community. “The citizen journalist does not make stories based on assignments, like us professional journalists; rather they report on the important things that matter to them, their communities, their lives. So, it is even more important for them to get the skills right.” she added.

Speaking of the role of citizen journalists in newsrooms, ABS-CBN Desk Editor and Producer Israel Malasa recounted how their newsroom broke the story of the Maguindanao Massacre in 2009, after they received information from a Bayan Patroller.

Malasa related how in November 2009, they received a photo from a Bayan Patroller of what were the bodies of the victims of the massacre. Working as the desk editor for the broadcast company’s Regional Network Group, based in Quezon City, he and his colleagues had to verify the information. “There was this photo that was sent to news by a Bayan Patroller. So, what we did was vet it. We called the authorities. The editors and reporters called up their various sources. And then it was confirmed that it was the massacre site,” he said. Without that courageous citizen journalist, he added, news of the horrendous incident would not have been known.

Tracing the roots of citizen journalism, Malasa illustrated how it began long before social media, when viewers of news programs such as TV Patrol, would send them information on community concerns such as ill-maintained roads and ditches, defective electricity posts and others. These stories were featured in a segment called Citizen Patrol. What made a difference between then and now was that the newsroom still needed to send a crew for these stories. “Back then what we would do is send a crew to the community. The crew would then engage the resident, the Citizen Patroller or citizen journalist, as how we call them now, get the facts and go to the authorities, interview, and then a solution about a particular problem is reached,” he said.

For Malasa, citizen journalists have contributed much to newsrooms, particularly with stories in different communities all over the country, which could not have been covered if information had not been provided to news organizations. “Citizen journalism, or information from the public, is in a way valuable, because it shows that it is not only the reporter who has knowledge of what is happening in society. If people on the ground are helping, if they are providing the facts, as long as it is substantiated, it is vetted, checked, it is an enormous contribution to a news organization,” said the UP Visayas alumnus.

Much has changed since then, as citizen journalists now can record their own materials and send their own information to the networks. For National Union of Journalists in the Philippines Chair Nonoy Espina, anyone can be a journalist as long as the person has the motivation, proper training and ethics. “[Ordinary] people can be very, very good journalists, if they have the motivation, and if they are given the skills to do it,” he said.

For Espina, training remains an important aspect of journalism which both citizen and professional journalists must have, as these are essentials in news gathering and crafting a story. “Putting a story together is not that easy. We might make it seem easy, but it actually isn’t. From gathering the facts to actually putting the story together,” he said.

And while citizen journalists may have undergone training, Espina, like Malasa, still suggests newsrooms must vet stories coming from the communities, as those in news organizations are more steeped in the professional standards of journalism and the legal regulations which affect the practice should there be lapses. Newsrooms, he also said, are liable, should libel cases arise from erroneous reporting. Referring to journalists and editors he said “If a story gets past you, especially an erroneous story, then you didn’t do your job. That is your fault. Then, you have to take responsibility for that.”

Espina however is quick to add that the collaboration between citizen journalists and professional journalists has been beneficial, particularly in situations which made it necessary for both to work together. “Actually, the best combination is the citizen journalist and the journalist. They should always work together. If one is separated from the other, then there is a disconnect [in the story they are working on],” he said.

Fact-checking vs disinformation

For investigative journalist and UP Associate Professor Yvonne Chua, one of the avenues where the public and journalism professionals best intersect in the age of disinformation is in fact-checking. As an educator, she has been teaching courses in fact-checking in the UP College of Mass Communication. “Fact-checking is increasingly becoming an important component of media literacy initiatives. In journalism education is an essential component,” she said.

Emphasizing journalism as a discipline of verification, Chua said the concept and practice of fact-checking in journalism has quickly evolved in recent years. In the past, the task of the practice of fact-checking in a news organization was undertaken by editors, who ensured the factual accuracy of the stories submitted by reporters before these were published. “The fact-checking we now refer to, has expanded to include verifying, and often debunking textual and visual claims, especially falsehoods, made by individuals, groups or institutions, ranging from our public officials, public figures, to netizens that produce user-generated content,” she said.

Sharing some notes from a recent study she was part of, Chua illustrated how the majority or 57% of the 19,621 respondents they had from all over the country, said disinformation is a serious problem. About 28% see it as somewhat of a concern. While 15% see no problem at all with disinformation. Among the age groups, she said those between ages 18 to 24 were more likely to view the proliferation of false information as serious.

The same age group also viewed disinformation as having possible effects on the elections. Despite these reactions, the respondents revealed they don’t verify news as much as they should. “Despite being aware that disinformation is a problem and could affect elections, the proportion of young Filipinos who have never verified the news or information that reaches them, is significantly higher than the 7% national average,” she added.

Also with regard to the results of the survey she and her colleagues conducted, the respondents defined ‘fake news’ as news which are bad for the president or the country, with a significant number of respondents from the 14 to 17 age group, agreeing. “It’s a sentiment that we know is often spouted by populist authoritarian leaders including our own,” she said.

Aside from concerns on disinformation, Chua said the study also revealed the lack of know-how among the respondents in how to verify news and information they came across. “This self-confessed gap in knowledge and skills certainly needs to be addressed,” said the journalism professor.

Viewing fact-checking as an invaluable tool for aspiring journalists, Chua views the course as essential in journalism education, particularly in the wake of the massive proliferation of disinformation and misinformation. The skills can either be included in teaching journalism ethics or as a stand-alone course. In recent years, she and her students have been involved in several projects where they verified the claims of political candidates and leaders. Among these are Tsek.ph and Factrakers .

In the interest of keeping fact-checkers safe from possible threats and intimidation from those who may dislike their findings, Chua said it is important that those involved in these projects refrain from posting unvetted fact checks on their personal social media accounts. They must also process negative feedback on their stories. And they must also consider whether their stories should have bylines or not.

Campus publications and democracy

Discussing threats and intimidation of campuses, UP Associate Professor Diosa Labiste talked about how in recent years, disinformation has taken the form of hate speech and red tagging, particularly against the UP community. Citing studies she did with Chua, she illustrated the similarities between hate speech and red tagging and how these contribute to the proliferation of disinformation online.

For the former community journalist, red-tagging, much like disinformation, is made up of false or fabricated accusations disseminated by trolls online. It has from minimal to almost no basis in fact. It also vilifies activists, critics of the administration and journalists. And similar to hate speech, it uses threats, harassment, some even resulting to arrests and deaths. Labiste believes the vilification of the university community while serious, can be met with stories coming from campus journalists who continue to provide accurate stories of issues and concerns confronting its members.

Underscoring the need for news reports that are fact-checked and verified, Labiste said campus journalists can fill gaps left by mainstream media in the exigencies of day-to-day news reporting. These means, young journalists-in-training can provide content which cannot be found in the commercial media. “Some news are not so sexy for commercial media or mainstream media to cover. But campus press has been covering these issues,” she said.

Labiste said that aside from providing unique content on news events, campus press can pursue stories which provide differing perspectives, diverse issues and more vigorous discussions and debate. It also provides students with the capacity for citizen-witnessing, which blurs the line between news producer and news consumer, as well as that between a journalist and an advocate. “Campus journalism is a form of counter speech because it intervenes to help citizens and communities make sense of information amid lies and ‘fake news.’”

For John Nery, a journalist, columnist and educator, campus journalism remains a strong pillar in the struggle against disinformation, not only in colleges and universities, but also in society at large. “Yes, we should use our campus publications to discuss school concerns; but at the same time, we have to realize that we actually occupy a position of privilege, and that our campuses are surrounded by what we call communities at risk,” he said.

School publications, according to Nery, act not only as hubs for public discourse of those in the academic community, but they can also function as public spaces for discussions of social issues which confront a community. Using UP Visayas and other higher education institutions in Iloilo as examples, he said their publications can serve as venues for conversations. “Why shouldn’t the school publications of UP Visayas, of the University of Iloilo, of PHINMA, and other Iloilo-based schools, talk about what’s happening in Iloilo? And by doing so, turn their school publications into their own version of the public square,” he added.

Emphasizing the dynamism of the youth in campuses, Nery underscored their capacity for reinvention and innovation, particularly at a time when there is a need for stories and voices from various communities in the country. Highlighting the potentials of campus journalists and publications, he said they could “very easily turn our campus publications from campus loudspeakers into community megaphones. We can use our campus newspapers, our campus news websites, into a forum where we can talk about the concerns of the people who live around us, literally.”

Summing up the conflict between disinformation and democracy in the country, a veteran human rights lawyer, Chel Diokno, said that the country was already suffering from an epidemic even before the onset of the novel Coronavirus disease 2019 or COVID-19. “This is a different kind of epidemic. It did not affect our human bodies. But rather, the human body politic. And that really was what we experienced, the last few years. An epidemic of extra judicial killings. An epidemic of abuse of power. And an epidemic that uses fear and violence,” he said.

According to Diokno, the current health pandemic has only served to exacerbate the difficulties ordinary Filipinos face. But in the same breath, he also highlighted how social media platforms have also served to condemn some of the questionable actions of public officials in the implementation of regulations of the public health emergency. He quickly added how sadly enough, the situation has also illustrated how the law is implemented differently for different groups of people. “We saw how poor people who violated quarantine regulations were given the full brunt of the law. While those who were connected or associated with those in power, just got a pat, sometimes even a mere reprimand, or not even that,” he said.

Affirming his belief in the power of the people, the chairman of the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG) said citizens must always: speak truth to power; remain vigilant even in difficult times; call out falsehoods particularly those disseminated online; and, ultimately hold those involved accountable for their actions. He was also quick to add that all these actions necessitate the involvement of individuals and communities from different backgrounds.

Expressing faith in the transformative power of the right to suffrage, Diokno said it is important for citizens to choose the right leaders for the country. And for that to happen, those in colleges and universities must call on everyone to properly exercise the right to vote. “At the end of the day, given the way our situation politically is run, we will have a golden opportunity, especially you, young people, to choose our future leaders, our next leaders, and to determine the future of our country, when the next elections come along.”

Aside from Diokno, Nery, UP Professors Labiste and Chua, the journalists Varona, Espina and Malasa, and Senator Hontiveros, former UP Student Regent and Youth Act Now Against Tyranny National Convenor Raoul Danniel Manuel also gave a talk on the role of the youth as defenders of press freedom. A UP alumna and ACCRALAW Associate Lawyer Kate Aubrey Hojilla also talked about press freedom and the Philippine Constitution.

Another UP alumna, Dr. Beverly Lorraine Ho, Director for Health Promotion of the Department of Health and Special Assistant to the Secretary for Universal Health Coverage, shared her experience in handling the department’s information campaign on the COVID 19 pandemic. Endy Bayuni, Jakarta Post Senior Editor and member of the Facebook Oversight Board, also talked about Campus Journalism and how the social media platform tackles disinformation.

Aside from the speakers, presentations on the proliferation of myths and misinformation on the Marcoses were also given. Miguel Reyes and Joel Ariate, Jr. of the UP Third World Studies Center talked about publications. While Dr. Earvin Cabalquinto of Deakin University, and Dr. Cheryll Ruth Soriano of De La Salle University Manila talked about revisionists videos online.

The 3rd National Conference on Democracy and Disinformation was hosted by UP Visayas on February 22, 24 and 26, 2021 as a project with the Consortium on Democracy and Disinformation. The consortium is a network of academics, journalists, bloggers and civil society groups. Among those which support the network are the University of the Philippines, the Ateneo de Manila University, De La Salle Philippines and Holy Angel University. For more information on the consortium, visit https://fightdisinfo.ph/ .

The conference was also held in partnership with MOVE.PH, Daily Guardian, UPV Division of Humanities, UPV Information and Publications Office and DYUP 102.7 FM. For videos of the conference, please visit https://www.facebook.com/DandD2021 .

Share this:

University of the philippines.

University of the Philippines Media and Public Relations Office Fonacier Hall, Magsaysay Avenue, UP Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Telephone number: (632) 8981-8500 Comments and feedback: [email protected]

University of the Philippines © 2024

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, journalism on campus.

What do Lorde, Shrek, and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston have in common? They’re all subjects I’ve written about for the Arts section of The Harvard Crimson!

The Crimson is Harvard’s independent daily newspaper, and it’s entirely written and produced by students. While classes, activities, and campus jobs have come and go, The Arts Board of The Crimson has remained a constant in my college life.

My high school may not have had a newspaper, but by the time I graduated I was certain that I wanted to be a journalist.

I had been bit by the political bug (much to my apolitical parents’ chagrin) and spent hours on hours reading all the longform and political journalism I could find. I searched The Atlantic, Politico, CNN, The New York Times, and other outlets for interesting pieces — frequently exhausting each publication’s free article allowance before the first week of the month was up.

The summer before my senior year of high school I was fortunate enough to participate in the Princeton University Summer Journalism Program, a summer “bootcamp” of sorts that introduces low-income students to the field of journalism as well as guides them through the college admissions process. I left PUSJP with a game plan for my future:

Step 1: Get into college.

Step 2. Write for my college newspaper.

Easy enough, right? I’ll spare you the lengthy details on Step 1. After a flurry of SAT exams, college essay edits, and last-minute finishing of my Common Application I was accepted to Harvard in December of my senior year of high school. As soon as I got to campus I made a point to find out when The Crimson’s first Open House would be.

I remember being nervous as I walked up to the unassuming brick building on Plympton St. in Cambridge — a stone’s throw away from Harvard Yard — but the feeling went away as soon as I saw the smiling faces waiting to greet me at the door.

I was rushed through a quick tour of the building the ended in a large meeting room where each board (News, Editorial, Arts, Design, etc.) gave their “elevator pitches” for joining their section of The Crimson. While I had walked in the building with plans of becoming the next big Politico writer, I felt myself compelled by the friendly faces and welcoming attitude of the Arts Board representatives. I went to my first Arts meeting the next week and never looked back.

This is the photo for my satirical piece: "My Guilty Pleasure is the Crimson Arts Internal Service Error." Photo by: Kathryn S. Kuhar