The Impact of Peer Interactions on Language Development Among Preschool English Language Learners: A Systematic Review

- Published: 20 November 2020

- Volume 50 , pages 49–59, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Princess-Melissa Washington-Nortey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8721-1710 1 ,

- Fa Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2839-6820 1 ,

- Yaoying Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3683-5347 1 ,

- Amber Brown Ruiz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3587-3747 1 ,

- Chin-Chih Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9503-8145 1 &

- Christine Spence ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6158-7082 1

3555 Accesses

11 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

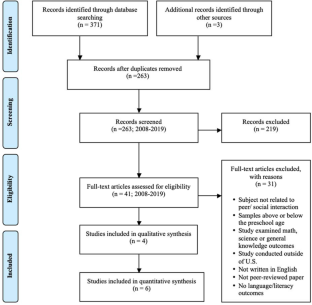

Studies showing that early language skills are important predictors of later academic success and social outcomes have prompted efforts to promote early language development among children at risk. Good social skills, a competence identified in many children who are English Language Learners (ELLs), have been posited in the general literature as facilitators of language development. Yet to date, a comprehensive review on the nature and impact of social interaction on language development among children who are ELLs has not been conducted. Using PRISMA procedures, a systematic review was conducted and 10 eligible studies published between 2008 and 2019 were identified. Findings revealed that despite their limited language capabilities, children who are ELLs can engage in complex speech during peer interaction. However, the nature and frequency of interactions, as well as the unique skill sets of communication partners may affect their development of relevant language skills. These findings have implications for policy and intervention development for preschool settings in the United States.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Early Language Intervention in School Settings: What Works for Whom?

The Influence of Teachers, Peers, and Play Materials on Dual Language Learners’ Play Interactions in Preschool

Jeffrey Trawick-Smith, Julia DeLapp, … Fatima Godina

An Exploration of Language and Social-Emotional Development of Children with and without Disabilities in a Statewide Pre-Kindergarten Program

Cailin J. Kerch, Carol A. Donovan, … Joy Winchester

Aikens, N., Tarullo, L., Hulsey, L., Ross, C., West, J., & Xue, Y. (2010). A Year in Head Start Children Families and Programs (No. 118a1d963bb04e23b24ea60039c88337). Mathematica Policy Research.

Atkins-Burnett, S., Xue, Y., & Aikens, N. (2017). Peer effects on children’s expressive vocabulary development using conceptual scoring in linguistically diverse preschools. Early Education and Development, 28 (7), 901–920.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, S., & Phillips, D. (2017). Is pre-K classroom quality associated with kindergarten and middle-school academic skills? Developmental Psychology, 53 (6), 1063.

Bell, E. R., Greenfield, D. B., Bulotsky-Shearer, R. J., & Carter, T. M. (2016). Peer play as a context for identifying profiles of children and examining rates of growth in academic readiness for children enrolled in head start. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108 (5), 740.

Bernstein, K. A. (2018). The perks of being peripheral: English learning and participation in a preschool classroom network of practice. TESOL Quarterly, 52 (4), 798–844.

Burchinal MR, Pace A, Alper R, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM (2016) Early language outshines other predictors of academic and social trajectories in elementary school. Presented at Assoc. Child. Fam. Conf. (ACF), Washington, DC, p. 11–13.

Bustamante, A. S., & Hindman, A. H. (2019). Classroom quality and academic school readiness outcomes in head start: The indirect effect of approaches to learning. Early Education and Development, 30 (1), 19–35.

Cabell, S. Q., Justice, L. M., McGinty, A. S., DeCoster, J., & Forston, L. D. (2015). Teacher–child conversations in preschool classrooms: Contributions to children’s vocabulary development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30, 80–92.

Carr, R. C., Mokrova, I. L., Vernon-Feagans, L., & Burchinal, M. R. (2019). Cumulative classroom quality during pre-kindergarten and kindergarten and children’s language, literacy, and mathematics skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 218–228.

Franco, X., Bryant, D. M., Gillanders, C., Castro, D. C., Zepeda, M., & Willoughby, M. T. (2019). Examining linguistic interactions of dual language learners using the language interaction snapshot (LISn). Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 48, 50–61.

Galindo, C., & Fuller, B. (2010). The social competence of latino kindergartners and growth in mathematical understanding. Developmental psychology, 46 (3), 579.

Guerrero, A. D., Fuller, B., Chu, L., Kim, A., Franke, T., Bridges, M., & Kuo, A. (2013). Early growth of mexican-american children: Lagging in preliteracy skills but not social development. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17 (9), 1701–1711.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., Owen, M. T., Golinkoff, R. M., Pace, A., & Suma, K. (2015). The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychological Science, 26 (7), 1071–1083.

Justice, L. M., Jiang, H., & Strasser, K. (2018). Linguistic environment of preschool classrooms: What dimensions support children’s language growth? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42, 79–92.

Justice, L. M., Petscher, Y., Schatschneider, C., & Mashburn, A. (2011). Peer effects in preschool classrooms: Is children’s language growth associated with their classmates’ skills? Child Development, 82 (6), 1768–1777.

Kyratzis, A. (2017). Peer ecologies for learning how to read: Exhibiting reading, orchestrating participation, and learning over time in bilingual Mexican-American preschoolers’ play enactments of reading to a peer. Linguistics and Education, 41, 7–19.

Kyratzis, A., Tang, Y. T., & Koymen, S. B. (2009). Codes, code-switching, and context: Style and footing in peer group bilingual play. Multilingua, 28, 265–290.

Mashburn, A. J., Justice, L. M., Downer, J. T., & Pianta, R. C. (2009). Peer effects on children’s language achievement during pre-kindergarten. Child Development, 80 (3), 686–702.

McWayne, C., & Cheung, K. (2009). A picture of strength: Preschool competencies mediate the effects of early behavior problems on later academic and social adjustment for head start children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30 (3), 273–285.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151 (4), 264–269.

National Education Association. (2015). Understanding the gaps: Who are we leaving behind and how far. NEA Education Policy and Practice & Priority Schools Departments and Center for Great Public Schools .

Pace, A., Luo, R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2017). Identifying pathways between socioeconomic status and language development. Annual Review of Linguistics, 3, 285–308.

Palermo, F., & Mikulski, A. M. (2014). The role of positive peer interactions and English exposure in Spanish-speaking preschoolers’ English vocabulary and letter-word skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly , 29 (4), 625–635.

Palermo, F., Mikulski, A. M., Fabes, R. A., Hanish, L. D., Martin, C. L., & Stargel, L. E. (2014). English exposure in the home and classroom: Predictions to spanish-speaking preschoolers’ english vocabulary skills. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35 (6), 1163–1187.

Pancsofar, N., & Vernon-Feagans, L. (2006). Mother and father language input to young children: Contributions to later language development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27 (6), 571–587.

Piker, R. A. (2013). Understanding influences of play on second language learning: A microethnographic view in one head start preschool classroom. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 11 (2), 184–200.

Pungello, E. P., Iruka, I. U., Dotterer, A. M., Mills-Koonce, R., & Reznick, J. S. (2009). The effects of socioeconomic status, race, and parenting on language development in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 45 (2), 544.

Rathbone, J., Hoffmann, T., & Glasziou, P. (2015). Faster title and abstract screening? Evaluating Abstrackr, a semi-automated online screening program for systematic reviewers. Systematic reviews, 4 (1), 80.

Romeo, R. R., Leonard, J. A., Robinson, S. T., West, M. R., Mackey, A. P., Rowe, M. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2018). Beyond the 30-million-word gap: Children’s conversational exposure is associated with language-related brain function. Psychological Science, 29 (5), 700–710.

Sawyer, B., Atkins-Burnett, S., Sandilos, L., Scheffner Hammer, C., Lopez, L., & Blair, C. (2018). Variations in classroom language environments of preschool children who are low-income and linguistically diverse. Early Education and Development, 29 (3), 398–416.

Schechter, C., & Bye, B. (2007). Preliminary evidence for the impact of mixed-income preschools on low-income children’s language growth. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22 (1), 137–146.

Spencer, T. D., Petersen, D. B., Slocum, T. A., & Allen, M. M. (2015). Large group narrative intervention in head start preschools: Implications for response to intervention. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13 (2), 196–217.

Stoddart, T., Solis, J., Tolbert, S., Bravo, M. (2010). A framework for the effective science teaching of English language learners in elementary schools. Teaching science with Hispanic ELLs in K-16 classrooms, 151–181.

Suskind, D., Suskind, B., Lewinter-Suskind, L. (2015). Thirty million words: Building a child's brain: tune in, talk more, take turns. Dutton Books.

Vernon-Feagans, L., Mokrova, I. L., Carr, R. C., Garrett-Peters, P. T., Burchinal, M. R., & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2019). Cumulative years of classroom quality from kindergarten to third grade: Prediction to children’s third grade literacy skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 531–540.

Weiland, C., & Yoshikawa, H. (2014). Does higher peer socio-economic status predict children’s language and executive function skills gains in prekindergarten? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35 (5), 422–432.

Wong, K., Boben, M., Thomas, M. C. (2018). Disrupting the early learning status quo: Providence Talks as innovative policy in diverse urban communities.

Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Justice, L. M., & Logan, J. A. (2019). The mediating role of classroom quality on peer effects and language gain in pre-kindergarten ECSE classrooms. Applied Developmental Science, 23 (1), 90–103.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Virginia Commonwealth University, 1015 West Main Street, Richmond, VA, 23284-2020, USA

Princess-Melissa Washington-Nortey, Fa Zhang, Yaoying Xu, Amber Brown Ruiz, Chin-Chih Chen & Christine Spence

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fa Zhang .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Washington-Nortey, PM., Zhang, F., Xu, Y. et al. The Impact of Peer Interactions on Language Development Among Preschool English Language Learners: A Systematic Review. Early Childhood Educ J 50 , 49–59 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01126-5

Download citation

Accepted : 20 October 2020

Published : 20 November 2020

Issue Date : January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01126-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- English language learners

- Peer interactions

- Language development

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

How young children learn language and speech: Implications of theory and evidence for clinical pediatric practice

Pediatric clinicians are on the front line for prevention of language and speech disorders. This review uses prevailing theories and recent data to justify strategies for prevention, screening and detection, diagnosis, and treatment of language and speech disorders. Primary prevention efforts rest on theories that language learning is the product of the interaction of the child’s learning capacities with the language environment. Language learning occurs in a social context with active child engagement. These theories support parent education and public programs that increase children’s exposure to child-directed speech. Early detection of delays requires clinician knowledge of language milestones and recognition of high-risk indicators for disorders. Male sex, bilingual environments, birth order, and chronic otitis media with effusion are not adequate explanations for clinically significant delays in language or speech. Current guidelines recommend both general and autism-specific screening. Sex, and environmental and genetic factors explain primary language and speech disorders. Secondary and tertiary prevention requires early identification of children with language and speech disorders in association with chromosomal, genetic, neurological, and other health conditions. Systematic reviews find that speech-language therapy, alone or in conjunction with other developmental services, is effective for many disorders. Speech-language interventions alter the environment and encourage children’s targeted responding to improve language and speech skills.

Introduction

Learning language seems like a monumental task for the young child. The world’s languages contain thousands of words that can be combined to convey an infinite number of meanings. Children are born without knowing which of the world’s languages they must learn. If born in Brazil, they must learn Portuguese; if born in the Philippines, they must learn Tagalog. If born in Belgium or Quebec, or into an immigrant or refugee family, they may need to learn two different languages simultaneously. Despite these challenges, most children acquire the fundamentals of language effortlessly in the toddler-preschool years, without formal instruction or explicit feedback. By age 5, they have a vocabulary of thousands of words; create sentences with complex grammatical features; differentiate literal from non-literal meanings, such as humor or metaphor; observe the social conventions of conversation; and apply language skills in the service of learning to read. By age 8, their speech sound inventory is mature.

Variation in the rate and efficiency of language development is substantial. Approximately 16% of children experience delays in the initial phases of language learning and approximately half of those children show persistent difficulties ( 1 ). Among children ages 3 to 5 years, speech and language impairment is the most prevalent eligibility criteria that warrants enrollment in special education preschool services ( Figure 1 ) ( 2 ). Among school aged children, the category of learning disabilities, often a late manifestation of language and speech disorders, predominates as the eligibility criterion for special education; however, speech-language impairment ranks second. Deficits in language or speech that are sufficiently severe to interfere with daily functioning, including learning, communication, and/or social interactions meet criteria as a disability.

Percentages of the >750,000 children ages 3 to 5 years in special education services across the United States by eligibility criteria.

Pediatric clinicians are on the front line for primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of language and speech disorders ( 3 ). Primary prevention, like immunizations, prevents the condition from occurring. Secondary prevention requires early detection and treatment of a disorder to result in a milder variant than would have occurred otherwise. Tertiary prevention may not change the disorder but improves functional outcomes of affected children. The over-riding objective of this review is to empower pediatric clinicians with prevailing theories, recent evidence, and recommendations to be used to promote primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of language and speech disorders.

Definitions

Language is the distinctly human form of communication that binds human social groups. Language uses arbitrary but socially-agreed upon signals (words and sentences) in a rule-governed system to convey meaning. Unlike animal communication, human language uses signals creatively to communicate beyond the here-and-now, allowing discussion of past or future events and abstract, hypothetical, or imaginary ideas. Speech is the usual output of the language system, created by the complex and coordinated movements of respiratory, laryngeal, velopharyngeal, and oral structures. Other outputs include sign languages or written language. Language is subdivided into receptive (ability to understand) and expressive (ability to produce) language. Language is further thought to be comprised of interacting subsystems or components: phonology (the system of speech sounds), lexicon (vocabulary), syntax (grammar), semantics (meaning) and pragmatics (social aspects of language that take into account the speaker and the context). Speech is also comprised of subsystems: articulation (speech sounds), voice and resonance, and fluency.

Primary prevention

Language learning is a product of the interaction of the child’s learning capacities with the language environment ( 4 ). Insights about how young children learn language derive from computer simulation models based on “parallel distributed processing” or “connectionist frameworks,” that are designed to mimic characteristics of human brain structure and function ( 5 ). Basic processing units in these models are simple and highly interactive, analogous to neurons in the brain. Units that become active simultaneously develop connections and connections that occur in unison form networks. Knowledge is conceptualized as patterns of activity within the network; learning represents changes in the patterns of activity within and across networks. Networks do not require any initial biases or built-in organization but rather organize based on experiences in the environment. These models can explain how infants can learn whatever language they are exposed to. These computer models have been found to explain many of the phenomena of language learning, such as how children learn to correctly conjugate both regular verbs and irregular verbs ( 5 ).

A challenge for the infant is segmenting the sound stream into meaningful units, such as words, that serve as inputs for learning. Children use “statistical learning” for this purpose. Statistical properties of sound sequences vary. For example, sounds that occur within words have a higher frequency of co-occurrence than sounds that occur between words. Infants, as young as age 8-month, unconsciously detect these distributional statistical properties and use them to segment the continuous sound stream into word-like units ( 6 ). Sequential statistical learning allows the young child to detect sequential ordering and co-occurrence of words within sentences to explain the acquisition of syntax ( 7 ). Moreover, infants and children can take advantage of statistics of word-referent co-occurrences to learn the meaning of words ( 8 ). Statistical learning is facilitated when parents use child-directed language, colloquially known as baby talk. Child-directed language is characterized by limited vocabulary, short sentences, multiple repetitions, relatively few errors, and exaggerated intonation ( 9 ).

An important ingredient for language learning is the social context. Early language learning requires human interactions; televisions and computers are not sufficient. Warm, mutually respectful, low stress exchanges between infants and competent language users, adults or other children, facilitate learning. Language learning requires the child’s active engagement with the input. Children must monitor the input, detecting, for example, differences between what they heard and what they might have said or what they thought a word meant. Recognition of the discrepancy helps children progress in learning semantics and syntax. Talking about what a child is doing or expanding what a child has just said facilitates the child’s active engagement.

Another challenge for the infant is learning to map speech perception to speech production ( 10 ). Most of the structures that generate speech sounds in the vocal tract are hidden from view. “Mirror neurons” that fire both when an individual performs an action and when the individual perceives others performing the same action are plausible mechanisms for linking perception to production. Human mirror neuron populations appear to be clustered in several cortical areas in the brain, including the pre-frontal cortex, which are often implicated in language use ( 10 ).

Primary prevention of language and speech delays or disorders may be achieved by providing children with a rich language environment within positive social relationships. Therefore, recommendations that primary care clinicians can give to parents of infants and young toddlers are as follows:

- Speak often to infants and young children. Baby talk, the use of simple sentences with exaggerated intonation, is well suited to children’s learning needs.

- Use language to describe or explain what a young child is doing or to expand what a child has just said in order to engage the child for language learning.

- Use of language during social interactions, such as reading books and playing. Reading is associated with more language input than meals, baths, or play ( 11 ).

- Limit screen time ( 12 ) in favor of active interactions.

- Support public policy initiatives that provide education to parents about language learning, such as nurse home visiting programs, or that support effective language environments for children, such as publicly funded universal preschool.

Early detection of language and speech delays

Early detection of language and speech delays is predicated on knowledge of the pattern of development. Table 1 documents milestones in the development of language and speech from infancy to age 8 years. Children produce their first words at about age 1 year. Initial lexical growth is slow, approximately 1–2 words/week. Once the vocabulary reaches about 50 words, the pace of development accelerates. Lexical growth increases to 1–2 new words/day and children begin combining words into two-word phrases. The “vocabulary spurt” has been attributed to biological factors, such as myelination of white matter language pathways ( 13 ). An increase in the pace of learning also conforms to self-organization of a neural network ( 5 ). Between ages 2 and 4 years, children build their lexicon and grammatical skills. Patterns of development vary across children, most likely as a function of their experiences in the environment. By school age, all of the fundamentals of language are typically mastered. Children may still show immaturities in motor speech skills to age 8 years, but intelligibility at school age should be about 100%.

Key Milestones in the development of receptive and expressive language, and speech

Developmental surveillance may detect children at high risk for disorders in language and speech. Surveillance uses all clinical approaches (history, physical and neurological exam, observations) at all health supervision visits. “Red flags” ( Table 2 ) are delays or differences that indicate a high prevalence for persistent disorders and should prompt an evaluation:

Red flags indicting high risk of language or speech disorder and prompting evaluation

The America Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends developmental screening with a validated instrument at least at ages 9, 18, and 24 to 30 months of age ( 14 , 15 ). Screening establishes whether a non- or pre-symptomatic child is at high or low risk for a language or speech disorder. A two-step screening process is important. The first step should use a general screening instrument, such as two commercial products, the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status ( http://www.pedstest.com/ ), the Ages and Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition (ASQ-3) ( http://agesandstages.com/products-services/asq3/ ), or other tools that have been developed for use in low and middle income countries ( 16 , 17 ). The second screen establishes the risk of autism spectrum disorder, using an instrument such as the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up (M-CHAT-R/F) ( 18 ). Autism screening alone may not be sufficient for establishing risk of language and speech disorders, which are more prevalent than autism ( Figure 1 ). Autism screening may detect some children missed on global screens.

Screening is not necessary when the child is known to have delays, has another condition associated with language or speech disorder, such as hearing loss or preterm birth (see below), or is enrolled in therapy for language or speech. In such cases, further description of the child’s strengths and difficulties may be useful for monitoring the child’s progress. The following commercially available instruments could be used in such situations within the clinical setting:

- MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory ( https://mb-cdi.stanford.edu/ ), a parent report instrument for children age 8–37 months.

- Language Development Survey, a parent report instrument for children age 18–35 months ( http://www.aseba.org/research/language.html ).

- The Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale of The Capute Scales ( http://www.brookespublishing.com/resource-center/screening-and-assessment/the-capute-scales/ ), a combination of direct assessment and parent report for children birth to 36 months.

- Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile (CSBS DP) Infant Toddler Checklist ( http://brookespublishing.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/csbs-dp-itc.pdf ), an direct assessment of social communication for children age 6–24 months.

Variations in language and speech development that do not cause delay

Boys may show mild delays in the development of language and speech skills compared to girls ( 19 ). However, the differences are modest. Boys have higher rates of language and speech disorders than girls. Therefore, the probability that a boy with an early delay will develop a disorder is high.

Children raised in bilingual environments are capable of learning two languages at the same time ( 20 ), even children with disabilities, such as Down syndrome ( 21 ). Bilingual children may have smaller vocabularies in each of their languages than monolingual children, though their combined vocabulary should be comparable in size to that of monolingual children ( 22 ). They may initially show mixing of the two languages, though over time separation of the two languages occurs ( 22 ).

Another source of variation is the child’s birth order. Later-born children are likely to hear less adult-generated language directed toward them, but more likely to overhear conversations between adults and their older siblings and have the older siblings as role models ( 23 ). Overall, studies show that later-born children do not acquire language at a later age than do firstborns. Clinicians should use the same assessment and management approaches in the care of later-born children as they do with first-born children with comparable delays

Chronic otitis media with effusion does not cause developmental delays in language or speech. Randomized clinical trials comparing early tympanostomy tube placement to watchful waiting showed that the operation did not change the outcomes in preschool or school aged children ( 24 , 25 ). Chronic otitis media is more prevalent in situations that also put language learning at risk, including poverty, crowding, limited breast feeding, and parental smoking ( 26 ), suggesting that it may be marker for adverse conditions that are associated with poor language or speech development. Clinicians should consider multiple reasons that children with chronic otitis media with effusion develop language or speech delays.

In summary, it is a misconception that children from the following categories with delays in early language or speech development will catch up to peers without any intervention:

- Children from bilingual homes

- Later born children

- Children with chronic otitis media with effusion

In all these cases, the same thresholds should be used to define delays and disorders and the same clinical procedures should be followed.

Language and speech delays

The term” delays” implies that the development of language or speech skills is slower than expected for age and follows the usual developmental pattern. A delay becomes clinically relevant when the rate of development falls < 75% expected, such as when a skill expected at 18 months is not present in a 24-month child (18/24=3/4 or 75% the expected rate). Approximately half of children who are delayed in language at age 2 years catch up by age 3 years. Children who show good symbolic play skills and/or normal receptive language despite delayed expressive language have a better prognosis than those with delays in symbolic play and receptive language. Children with either language or speech delay should receive a comprehensive pediatric evaluation. Table 3 describes the components of a comprehensive pediatric evaluation. Based on the results of that assessment, the clinician may refer the child for treatment or place the child on an enhanced surveillance schedule. Factors that cause language or speech delays and should prompt treatment are as follows.

Evaluation of a child with language or speech delay or disorder

Environmental factors.

A recent systematic review found that family environmental factors, such as socioeconomic status and parental education, parental health, and the level of engagement of parents with children are all associated with the rate of language development ( 27 ). Variation in the amount of language a child hears may mediate the effect of adverse social conditions on development. The classic observation that social class impacts language outcomes came from the work of Hart and Risley ( 28 ) who estimated the number of words children heard by recording weekly samples of conversations in their homes. Children of low socioeconomic status (SES) were exposed to 30 million fewer words than children of high SES. Recent studies using day-long recordings of home language have confirmed that amount of speech that children hear at age 16 or 18 months predicts lexical growth and speed of language processing at older ages ( 11 , 29 ). In interpreting these environmental influences on child language, it is important to recognize the possibility of shared genetic variance between parent and child ( 30 ).

Infants raised in orphanages have profound delays in the development of language and speech along with many other health and developmental disorders ( 31 ). The Bucharest Early Intervention project demonstrated that these devastating effects could be eliminated though placement in foster care before 15 months of age. Adverse effects were moderated through placement in foster care before but not after 24 months of age ( 32 ). These encouraging data demonstrate the plasticity of language in its earliest stages.

Sex differences.

Boys have higher rates of language and speech delays and disorders than girls ( 33 ). This finding may be reflective of genetic variation, implicating sex chromosomes. Male sex is associated with pro-inflammatory forces and placental lesions ( 34 ). The maternal immune response against the invading interstitial trophoblast may be an initial event leading ultimately to sex differences in language disorders. Another possibility is that prenatal hormones, such as testosterone, exert important influences on the developing brain, influencing structural features such as the degree of laterality or difference between the left and right hemisphere ( 35 ).

Biological factors interact with environmental factors to explain sex differences in language and speech. Girls prefer to remain in close proximity and engage in social interactions with adults; boys prefer active, rough and tumble play. Sex differences interact with SES. Boy-girl sex differences have been found in low-SES but not high SES children ( 19 ). Clinicians are often slow to refer boys with language delays for treatment on the assumption that the child will eventually catch up. However, since boys are at higher risk than girls for disorders, clinicians should proceed to evaluation and treatment when a delay is detected.

Genetic factors.

Genetic variation appears to be important for variation in how quickly and efficiently children learn ( 36 ). Disorders of speech and language cluster in families; the median incidence of language difficulties was found to be over 3-times higher in families of children with language impairment than in unaffected families ( 37 ). Twin studies have confirmed that concordance of speech and language disorders is higher in monozygotic pairs than it is in dizygotic twins pairs. The presence of reading disorders in the family also put children at risk for language disorders ( 38 ).

The first reports identifying a specific genetic alteration associated with language and speech disorders came from studies of a large three-generation family, called the KE family, in which approximately half of the members had complex speech difficulties. A single nucleotide change on a gene called FOXP2, located on chromosome 7q31differentiated affected and unaffected family members. Curiously, this gene is one of a family of genes controlling transcription of other genes rather than coding traits. One theory is that FOXP2 influences the expression of other genes, such as CNTNAP2, that encodes a neurexin and is expressed in the developing human cortex. Genetic variation in CNTNAP2 has been associated with language impairment.

Beyond these findings, it has proven difficult to identify specific genes associated with language and speech disorders ( 39 ). It is possible that multiple genes may be involved ( 40 ) or that despite behavioral similarities, the disorders are heterogeneous, each with a distinctive genetic etiology. Decisions about genetic testing for children with speech and language disorder should be individualized, based on the phenotype, symptom severity, family history and related factors.

Primary disorders of language and speech

Secondary or tertiary prevention is predicated on early detection of language or speech disorders and prompt treatment, because early treatment is generally associated with better outcomes than delayed treatment. Language disorders represent deficiencies in the ability to express or understand human communication. Delays become disorders when they persist to school age, follow different developmental trajectories, are severe, and/or negatively impact functioning. One classification of language disorders subdivides them into receptive, expressive, and mixed expressive-receptive language disorders. However, this classification system may not be accurate. Difficulties with language expression may be accompanied by limitations in language comprehension and processing that are subtle and more difficult to detect than the problems of expression [REF]. An alternative classification of disorders of language is based on the aspects of language affected ( Figure 2 ), aligned with subcomponents of phonology (the system of speech sounds), lexicon (vocabulary), syntax (grammar), semantics (meaning) and pragmatics (social aspects of language that take into account the speaker and the context). Speech disorders can also affect one or more subcomponents ( Figure 2 ), representing difficulties with speech sounds, vocal quality and resonance, and/or fluidity.

Components of language and speech

A persistent and serious delay in the acquisition of language skills in the absence of other developmental, health, or mental health conditions goes by many names: spoken language disorder, primary, or specific language impairment (SLI)( 41 ). SLI indicates that though the language disorder is the most relevant finding, associated conditions, may also be present. SLI is clinically heterogeneous. Usually, difficulties with syntax are prominent (Figure 3). Other features may include delays in phonologic development, semantics, and/or pragmatics. Children with SLI typically present with delayed emergence of single words, phrases, and sentences. Comprehension often appears relatively spared. Speech skills also may or may not be impaired.

Several general neuropsychological processes, such as speed of language processing and memory, are associated with SLI. Speed of language processing at age 18 months, as measured in an eye tracking task, has been found to be associated with measures of language skills up to age 8 years ( 42 ). Children who are late talkers at age 2 years and at high risk for SLI have slower speed of processing than children with typical early language. Slow speed of processing may result in SLI because affected children have difficulty understanding, anticipating, and learning from rapid-paced speech or sentences of increasing length. Deficits in phonological short-term and working memory are also associated with SLI ( 43 ), presumably because it is essential to hold sound patterns in mind in order to learn new words and structures. Phonological short-term memory can be measured by a non-word repetition task that requires children to listen to novel phonetic sequences of varying lengths and repeat them back. At older ages, children with SLI may meet criteria for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and/or may have difficulties with executive functions, such as response inhibition, working memory, organization or planning. Children with SLI are at risk for later reading disorders because reading rests on a foundation of language abilities ( 44 ).

Disorders of speech may occur in isolation or in conjunction with disorders of language. Articulation disorders are motor speech disorders that represents difficulties producing specific sounds of the language (Figure 3). Mild articulation disorders are highly prevalent and rarely disrupt communication or social functions. Severe articulation disorders may impact other domains of function. Dysarthria is a disorder of the muscle movements required for speech production and often occurs in the aftermath of brain injury. Childhood Apraxia of Speech is considered a disorder of planning and executing speech sounds. Hallmarks of the condition include delays in the onset of babbling or single word productions, errors in articulating vowel sounds, inconsistent errors in producing words, increasing difficulty with words or phrases of increasing length, increased difficulty with production of spontaneous as opposed to well-rehearsed sentences, and effortful speech. The importance of differentiating Childhood Apraxia of Speech from other disorders is that the treatment approach is distinctive; children typically require an approach that emphasizes motor programming and motor learning to improve production of speech sounds. They also need intensive and frequent practice of staged and specific speech targets.

Stuttering is a disorder of fluency (Figure 3). Children often experience dysfluency before age 4 years as their thinking processes outpace their speech processes. Developmental dysfluency involves repetition of entire words or phrases. Stuttering is a non-developmental problem that includes repetition of individual speech sounds (p-p-p-pop); prolongations (mmmme); abnormal pauses between sounds; excessive use of fillers, such as uh or um; and use of behavioral strategies, such as self-slapping to try to get the words out. Even at ages < 4, the presence of the features of stuttering should prompt referral for further evaluation and treatment.

Speech-Language Disorders secondary to known conditions.

Secondary and tertiary prevention require early detection and treatment of language and speech disorders among children with other health or neurodevelopmental conditions. The use of parent-reported questionnaires or direct observation language and speech instruments within pediatric subspecialty care is recommended for children, especially for those who are not receiving speech-language pathology services, early intervention or special education (see above). Recommendations for the evaluation of children with language and speech delays or disorders are designed to rule out known causes, including adverse psychosocial conditions ( Table 2 ).

- Hearing loss . Language and speech disorders are highly likely with severe to profound hearing loss (threshold > 55 decibels). Individuals with mild (threshold of 26–40 decibels) to moderate (threshold of 41 to 55 decibels) sensorineural hearing loss may be able to detect and discriminate vowel sounds and low-frequency consonants, such as /m/ and /b/, but may not detect or discriminate high-frequency consonants, such as /f /, /th/ and /sh/. Universal newborn hearing screening has increased early identification of children with moderate to profound hearing loss. Reevaluation of hearing in children with language or speech abnormalities is critical because the newborn test may have been a false negative, the hearing loss may be mild, or the child may have a progressive hearing loss.

- Global developmental delay and intellectual disability. Language and speech delay may be the initial presentation of children with global developmental delays. If delays persist and are accompanied by deficits in adaptive skills, children may meet criteria for intellectual disability. Intellectual disability ranges from mild (IQ 55–69) to profound levels (IQ < 25). Language skills are generally commensurate with other developmental abilities. Even children with severe intellectual disability (IQ 25–39) typically learn at least minimal language skills.

- Autism . Autism is defined by two key criteria: deficits in the domain of social communication and excessive restricted or repetitive behaviors. The presenting problem in autism is often delays or regression in speech and language skills. The prevalence of autism had been increasing over the last two decades and has stabilized over the last 8 years ( 45 ). Prognosis is better when children receive early intervention services than when behavior management and education are delayed. For these reasons, consideration of the diagnosis of autism is critically important in the evaluation of children with language delay.

- Known genetic variations . Chromosomal and genetics conditions have distinctive profiles in terms of speech and language. For example, in trisomy 21 or Down syndrome, deficits in speech and language skills are often more severe than deficits in non-verbal skills. In Williams Syndrome (WS), caused by a deletion on chromosome 7, deficits in non-verbal skills are more severe than deficits in language. Fragile X is caused by a trinucleotide repeats and mutations in the FMR1 gene. Individuals with Fragile X have deficient language skills in association with poor social skills, high levels of anxiety, and frequent hyperactivity. About 20–25% of individuals with Fragile X meet criteria for a diagnosis of autism.

- Neurological disorders. Structural brain injuries may affect language and speech. Children with injury to left or right hemisphere frontal and temporal regions may show delays in the early phases of language development and subsequent disorders, though their symptoms are milder than those of adults with similar injuries ( 46 , 47 ). Notably, environmental factors influence the rate of language learning after brain injury. By age 5, children from high SES families with brain injury outperformed children without brain injury from low SES families ( 48 ). Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have found that children with early left hemisphere injury show multiple pathways of plasticity, associated with variation in outcome ( 49 ) Specific epilepsy syndromes are associated with language and speech disorders. Landau Kleffner is a rare seizure disorder associated with regression in speech and language skills and therefore part of the differential diagnosis in autism with regression. However, whereas the regression in autism typically occurs before age 3, the regression in Landau Kleffner occurs later. The cardinal finding is auditory agnosia, a profound disruption of language comprehension with resulting adverse effects on language production. Other neurological conditions with effects on language and speech include tuberous sclerosis.

- Cleft palate . Cleft palate is failure of fusion of the hard and/or soft palate. Even if the defect is repaired, weak velopharyngeal muscles allow air to flow through the nose rather than out the mouth in the production of speech sounds, resulting in hypernasal speech. Children with cleft palate, even as an isolated condition and not part of a broader syndrome, may also experience delays or disorders in the development of language as well as speech though the reasons are not clear.

- Other health conditions. Meta-analyses show that children born preterm show persistent delays in the development of language ( 50 ), independent of socioeconomic status, and even among samples that include only children without major disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, and sensory impairments ( 51 ). These deficits have been attributed to subtle neurological deficits that may be present even in the absence of telltale signs on neuroimaging. Similarly, children with congenital heart disease show delays in the development of language, associated with changes in white matter ( 52 ).

Management and Treatment

Children with language or speech delays or disorders have failed to learn language from observation and social participation. Therefore, watchful waiting is rarely a good approach. Therapy is warranted. The speech-language pathologist is the professional charged with designing and implementing the treatment plan for a child with language or speech delays or disorders. Speech-language pathology services alone may be adequate for the child with mild to moderate language or speech delays or isolated disorders without complications. Early intervention for children birth to 3 or special education services for children over age 3 is appropriate for children with moderate to severe language and speech disorders, other developmental conditions, and/or behavioral challenges that compromise participation and cooperation. Referral to therapy services is appropriate even while the comprehensive evaluation of the disorder is ongoing because of the long delays for many diagnostic services.

Though the causes of language and speech disorders are diverse, including genetic or neurological conditions, manipulation of the child’s experience in the environment is the main lever available to improve the child’s skills and functioning. The speech-language pathologist, implicitly or explicitly, creates environments that increases the odds of the child’s learning the weak or missing skill. Effective language interventions may provide a higher number of effective language learning episodes than would be available to children in their typical environment. Therapy may increase the child’s opportunities to listen and speak, increase the salience of elements that the child has not mastered, and/or encourage expression of weak and developing skills. Therapy may also provide corrective feedback, such as recasting, that facilitates learning correct forms. Critical ingredients for therapeutic intervention, analogous to primary learning, are the child’s active engagement and a warm supportive relationship. Therapy for toddlers and preschoolers is typically play-based rather than drill. The specific activities chosen for a session focus on interests of the child. An example of home-based speech-language therapy can be found at the following url: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gTPS0cX4VQ .

The data on the efficacy or effectiveness of speech and/or language therapy, especially using randomized controlled trials is limited. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that speech and language therapy is generally effective for children with phonological or expressive vocabulary difficulties but less clear for children with expressive syntax difficulties. Little evidence was available considering the effectiveness of intervention for children with receptive language difficulties ( 53 ).

Children often get a minimal dose of speech-language therapy, such as 30 to 60 minutes of therapy a week or less. The low dose of treatment is driven in part by child factors, such as children’s relatively weak attentional capacity and by systems issues, such as high costs and limited availability of therapists. Participation of parents, family members and teachers in the program leverages the otherwise limited intensity of service. A systematic review found no significant differences between interventions administered by trained parents and clinicians ( 53 ). A second systematic review reported that home programs can lead to growth in a child’s skills and are more effective than no intervention, provided that a high dose of program is delivered by parents who have received direct training in the intervention techniques ( 54 ). Another strategy to increase the dose of treatment is to provide group therapy sessions; the duration of treatment is not the 30 to 60 minutes reserved for a single child, but 2 to 3 hours for 4 to 8 children. The added advantage of group therapy is that children practice their developing skills with other children in semi-naturalistic settings. A systematic review found no differences in the effects of individual versus group therapies ( 41 ). Language and speech therapy are often part of a child’s individual educational plan at school. Teachers as well as parents should know the goals and strategies that the speech-language pathologists are using and apply them in the classroom to maximize the impact of therapeutic services.

As children age, it becomes increasingly important that they can use language and speech skills in the service of functional domains, including learning, communication, and social interaction. A systematic review of school-based treatment procedures addressing social communication behaviors found that gains were seen in conversational abilities, including topic management skills, narrative production, and repairs of inadequate or ambiguous comments ( 55 ).

For children with poor motivation or disordered behavior, behavioral measures may be included with rewards and consequences for desired and undesired behaviors, respectively. Behavioral approaches are typically required for children with autism who lack motivation to communicate. Developmental and naturalistic behavioral techniques are particularly appropriate for young children because they can be applied in everyday activities. For children with motor speech disorders, especially Childhood Apraxia of Speech, a motor learning component is included in the therapy; the child practices carefully planned sequences of emerging sound patterns. Examples of therapies for Childhood Apraxia of Speech can be found at the following website: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sq7vFWLqodM . Recommendations for therapy for Childhood Apraxia of Speech include frequent but short sessions, at least four times per week, with family and school participation in the treatment program; preliminary evidence demonstrates promising outcomes ( 56 ). Use of non-speech oral motor exercises, such as blowing, lip strengthening, and lateral tongue movements are not beneficial for the treatment of motor speech disorders primarily because speech sounds do not use the oral mechanisms in the same movements as eating or drinking. However, cues to placement of the tongue or lips for proper speech sound production may be helpful. For children with extremely limited verbal output, assistive and augmentative communication devices (AACs), such as sign language, picture exchange, or voice activated software, may also be considered. AAC methods are often taught in schools. Unfortunately, high technology devices may not be able to travel home with the student. In addition, family members may not learn the AAC methods and therefore cannot help their child to use the technique in home and community settings. To be most effective, AAC parents and teachers should get training in the use of the AAC method and should encourage the child to use the method in all communication settings.

Language is a distinctly human form of symbolic communication. Delays and disorders of language and speech are prevalent ( 1 ). The main points of this review and the clinical implications are as follows:

- Research shows that the amount of child-directed speech is a strong contributor to the child’s language development ( 11 , 27 , 28 ). Based on clinical consensus in relation to these data, primary care clinicians play a role in primary prevention of language and speech disorders by counseling families about the importance of the learning environment. The US Preventive Services Task Force concluded that no studies have yet examined the effects of screening on speech and language or other functional outcomes ( 57 ). However, based on some research and consensus, professional organizations recommend a developmental screening at age 9, 18 and 24 or 30 months and, in addition, autism screening at 18 and 24 or 30 months ( 14 , 15 ).

- Research shows that bilingualism ( 19 ), later birth order ( 22 ), and otitis media ( 23 – 25 ) are not causes of language delays. Therefore, children with delays and these conditions should be managed in the same manner as all other children with delays.

- The specific diagnoses of language and speech disorders are predicated on the component of language or speech affected. Additionally, disorders may be classified as primary when no other major disorder is present ( 41 ). Disorders may be secondary to other conditions, including severe psychosocial deprivation, hearing loss, global developmental delay or intellectual disability, known genetic variants, and neurological conditions, and other health conditions, such as prematurity.

- Speech-language therapy has been shown to be useful for some though not all disorders of language and speech disorders ( 53 , 57 ). Nonetheless, based on this research, clinical consensus is that children should be referred for language and/or speech therapy, either in isolation or as part of an early intervention or special education program.

- On-going monitoring by the primary care clinician may allow early detection of attention deficits, executive function limitations, or reading disorders, all of which may be associated with language or speech disorders. The ultimate goal of all screening, assessment, referral and on-going monitoring is to allow children to reach their maximal functional capacity for language and speech and to participate fully and joyfully within the human community.

Disorders of language and speech based on affected component

ABP Content Specifications :

Content specifications for general pediatrics.

Domain 1: A. Normal Growth and Development, 4. Language Development

Domain 1: D. Screening and Disease Prevention, 3. Psychosocial Screenings

Domain 5: A. Cognition, language, learning, and neurodevelopment 1. Clinical presentation (eg, development delay - cognition, language, learning or social)

Domain 5: A. Cognition, language, learning, and neurodevelopment. 2. Disorders and conditions, c. Autism

Practice Gaps:

To prevent delays and disorders and to provide effective clinical care to children with disorders of language and speech occur, pediatric clinicians must become familiar with prevailing theories, evidence, and recommendations of professional organizations. Pediatricians should not postpone evaluation and treatment for boys, children from bilingual environments, second- or third-born children, or children with chronic otitis media with effusion.

Acknowledgments

Funding source : Ballinger-Swindells Endowed Professorship for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine

Abbreviations

Conflict of Interest and Financial Disclosure statements: None

Learning objectives: By completion of this article, readers should be able to

1. Apply current theories regarding how young children learn language and speech to accomplish primary prevention of language and speech disorders

2. List key milestones of typical language development and indicators of high risk status for language or speech disorders to assist in early detection of disorders

3. Justify the use of both general and autism-specific screening tools for screening language and speech disorders

4. Discuss primary and secondary causes of language and speech disorders to develop strategies for secondary prevention

5. Evaluate intensity and nature of speech-language pathology therapy to treat children with language disorders as part of secondary and tertiary prevention

- Open access

- Published: 15 March 2022

A review of academic literacy research development: from 2002 to 2019

- Dongying Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6835-5129 1

Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education volume 7 , Article number: 5 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

16k Accesses

12 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

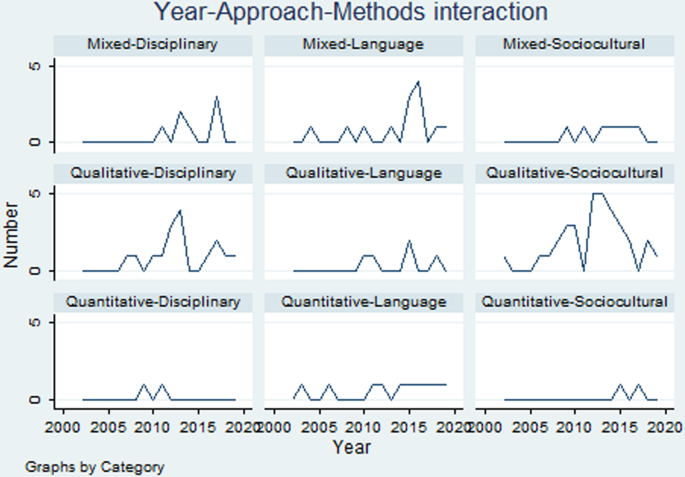

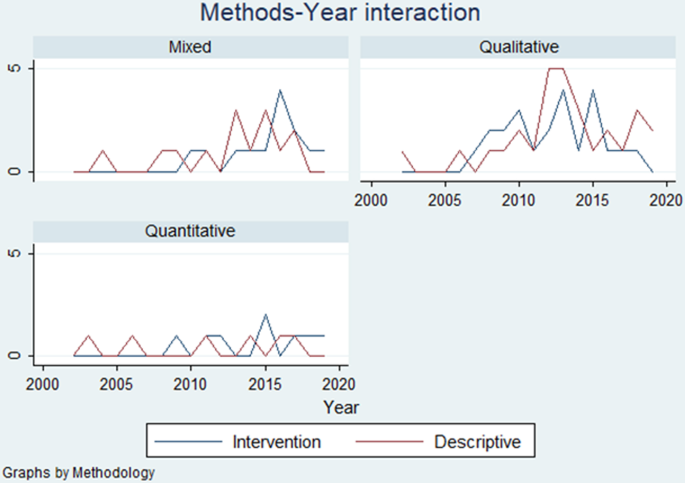

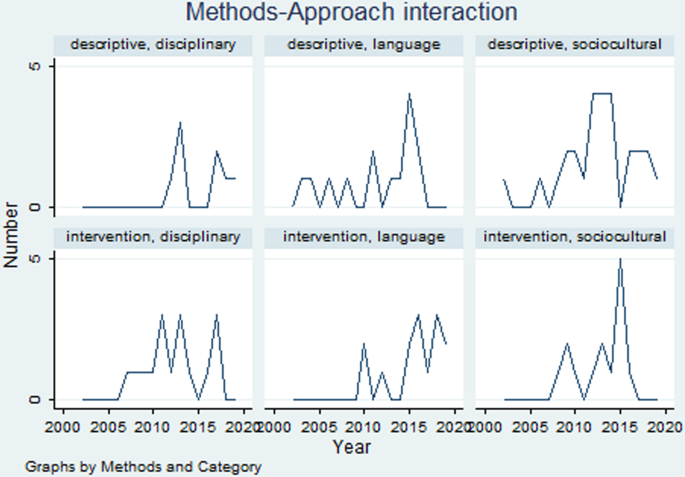

Academic literacy as an embodiment of higher-order language and thinking skills within the academic community bears huge significance for language socialization, resource distribution and even power disposition within the larger sociocultural context. However, although the notion of academic literacy has been initiated for more than twenty years, there still lacks a clear definition and operationalization of the construct. The study conducted a systematic review of academic literacy research based on 94 systematically selected research papers on academic literacy from 2002 to 2019 from multiple databases. These papers were then coded respectively in terms of their research methods, types (interventionistic or descriptive), settings and research focus. Findings demonstrate (1) the multidimensionality of academic literacy construct; (2) a growing number of mixed methods interventionistic studies in recent years; and (3) a gradual expansion of academic literacy research in ESL and EFL settings. These findings can inform the design and implementation of future academic literacy research and practices.

Introduction

Academic literacy as an embodiment of higher order thinking and learning not only serves as a prerequisite for knowledge production and communication within the disciplines but also bears huge significance for individual language and cognitive development (Flowerdew, 2013 ; Moje, 2015 ). Recent researches on academic literacy gradually moved from regarding literacy as discrete, transferrable skills to literacy as a social practice, closely associated with disciplinary epistemology and identity (Gee, 2015 ). The view of literacy learning as both a textual and contextual practice is largely driven by the changing educational goal under the development of twenty-first century knowledge economy, which requires learners to be active co-constructors of knowledge rather than passive recipients (Gebhard, 2004 ). Academic literacy development in this sense is considered as a powerful tool for knowledge generation, communication and transformation.

However, up-till-now, there still seems to lack a clear definition and operationalization of the academic literacy construct that can guide effective pedagogy (Wingate, 2018 ). This can possibly lead to a peril of regarding academic literacy as an umbrella term, with few specifications on the potential of the construct to afford actual teaching and learning practices. In this sense, a systematic review in terms of how the construct was defined, operationalized and approached in actual research settings can embody huge potential in bridging the gap between theory and practice.

Based on these concerns, the study conducts a critical review of academic literacy research over the past twenty years in terms of the construct of the academic literacy, their methods, approaches, settings and keywords. A mixed methods approach is adopted to combine qualitative coding with quantitative analysis to investigate diachronic changes. Results of the study can enrich the understandings of the construct of academic literacy and its relations to actual pedagogical practices while shedding light on future directions of research.

Literature review

Academic literacy as a set of literacy skills specialized for content learning is closely associated with individual higher order thinking and advanced language skill development (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008 ). Recent researches suggest that the development of the advanced literacy skills can only be achieved via students’ active engagement in authentic and purposeful disciplinary learning activities, imbued with meaning, value and emotions (Moje et al., 2008 ). Therefore, contrary to the ‘autonomous model’ of literacy development which views literacy as a set of discrete, transferrable reading and writing skills, academic literacy development is viewed as participation, socialization and transformation achieved via individual’s expanding involvement in authentic and meaningful disciplinary learning inquiries (Duff, 2010 ; Russell, 2009 ). Academic literacy development in this sense is viewed as a powerful mediation for individual socialization into the academic community, which is in turn closely related to issues of power disposition, resource distribution and social justice (Broom, 2004 ). In this sense, academic literacy development is by no means only a cognitive issue but situated social and cultural practices widely shaped by power, structure and ideology (Lillis & Scott, 2007 ; Wenger, 1998 ).

The view of literacy learning as a social practice is typically reflected in genre and the ‘academic literacies’ model. Genre, as a series of typified, recurring social actions serves as a powerful semiotic tool for individuals to act together meaningfully and purposefully (Fang & Coatoam, 2013 ). Academic literacy development in this sense is viewed as individual’s gradual appropriation of the shared cultural values and communicative repertoires within the disciplines. These routinized practices of knowing, doing and being not only serve to guarantee the hidden quality of disciplinary knowledge production but also entail a frame of action for academic community functioning (Fisher, 2019 ; Wenger, 1998 ). Therefore, academic literacy development empowers individual thinking and learning in pursuit of effective community practices.

Complementary to the genre approach, the ‘academic literacies’ model “views student writing and learning as issues at the level of epistemology and identities rather than skill or socialization” from the lens of critical literacy, power and ideology (Lea & Street, 1998 , p. 159). Drawing from ‘New Literacies’, the ‘academic literacies’ model approaches literacy development within the power of social discourse with the hope to open up possibilities for innovations and change (Lea & Street, 2006 ). Academic literacy development in this sense is regarded as a powerful tool for access, communication and identification within the academic community, and is therefore closely associated with issues of social justice and equality (Gee, 2015 ).

The notion of genre and ‘academic literacies’ share multiple resemblances with English for Academic Purposes (EAP), which according to Charles ( 2013 , p. 137) ‘is concerned with researching and teaching the English needed by those who use the language to perform academic tasks’. As can be seen, both approaches regard literacy learning as highly purposeful and contextual, driven by the practical need to ‘foregrounding the tacit nature of academic conventions’ (Lillis & Tuck, 2016 , p. 36). However, while EAP is more text-driven, ‘academic literacies’ are more practice-oriented (Lillis & Tuck, 2016 ). That is rather than focusing on the ‘normative’ descriptions of the academic discourse, the ‘academic literacies’ model lays more emphasis on learner agency, personal experiences and sociocultural diversity, regarded as a valuable source for individual learning and the transformation of community practices (Lillis & Tuck, 2016 ). This view of literacy learning as meaningful social participation and transformation is now gradually adopted in the approach of critical EAP (Charles, 2013 ).

In sum, all these approaches regard academic literacy development as multi-dimensional, encompassing both linguistic, cognitive and sociocultural practices (Cumming, 2013 ). However, up-till-now, there still seems to lack a clear definition and operationalization of the academic literacy construct that can guide concrete pedagogies. Short and Fitzsimmons ( 2007 , p. 2) provided a tentative definition of academic literacy from the following aspects:

Includes reading, writing, and oral discourse for school Varies from subject to subject Requires knowledge of multiple genres of text, purposes for text use, and text media Is influenced by students’ literacies in contexts outside of school Is influenced by students’ personal, social, and cultural experiences.

This definition has specified the main features of academic literacy as both a cognitive and sociocultural construct; however, more elaborations may be needed to further operationalize the construct in real educational and research settings. Drawing from this, Allison and Harklau ( 2010 ) and Fang ( 2012 ) specified three general approaches to academic literacy research, namely: the language, cognitive (disciplinary) and the sociocultural approach, which will be further elaborated in the following.

The language-based approach is mainly text-driven and lays special emphasis on the acquisition of language structures, skills and functions characteristic of content learning (Allison & Harklau, 2010 , p. 134; Uccelli et al., 2014 ), and highlights explicit instruction on academic language features and discourse structures (Hyland, 2008 ). This notion is widely influenced by Systemic Functional Linguistics which specifies the intricate connections between text and context, or linguistic choices and text meaning-making potential under specific communicative intentions and purposes (Halliday, 2000 ). This approach often highlights explicit consciousness-raising activities in text deconstruction as embodied in the genre pedagogy, facilitated by corpus-linguistic research tools to unveil structures and patterns of academic language use (Charles, 2013 ).

One typical example is data driven learning (DDL) or ‘any use of a language corpus by second or foreign language learners’ (Anthony, 2017 , p. 163). This approach encourages ‘inductive, self-directed’ language learning under the guidance of the teacher to examine and explore language use in real academic settings. These inquiry-based learning processes not only make language learning meaningful and purposeful but also help form more strategic and autonomous learners (Anthony, 2017 ).

In sum, the language approach intends to unveil the linguistic and rhetorical structure of academic discourse to make it accessible and available for reflection. However, academic literacy development entails more than the acquisition of academic language skills but also the use of academic language as tool for content learning and scientific reasoning (Bailey et al., 2007 ), which is closely connected to individual cognitive development, knowledge construction and communication within the disciplines (Fang, 2012 ).

Therefore, the cognitive or disciplinary-based approach views academic literacy development as higher order thinking and learning in academic socialization in pursuit of deep, contextualized meaning (Granville & Dison, 2005 ). This notion highlights the cognitive functions of academic literacy as deeply related to disciplinary epistemologies and identities, widely shaped by disciplinary-specific ways of knowing, doing and thinking (Moje, 2015 ). Just as mentioned by Shanahan ( 2012 , p. 70), ‘approaching a text with a particular point of view affects how individuals read and learn from texts’, academic literacy development is an integrated language and cognitive endeavor.

One typical example in this approach is the Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach (CALLA) initiated by Chamot and O’Malley ( 1987 ), proposing the development of a curriculum that integrates mainstream content subject learning, academic language development and learning strategy instruction. This approach embeds language learning within an authentic, purposeful content learning environment, facilitated by strategy training. Another example is the Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP model) developed by Echevarría et al. ( 2013 ). Sheltered instruction, according to Short et al. ( 2011 , p. 364) refers to ‘a subject class such as mathematics, science, or history taught through English wherein many or all of the students are second language learners’. This approach integrates language and content learning and highlights language learning for subject matter learning purposes (Allison & Harklau, 2010 ). To make it more specifically, the SIOP model promotes the use of instructional scaffolding to make content comprehensible while advancing students’ skills in a new language (Echevarría et al., 2013 , p. 18). Over the decade, this notion integrating language and cognitive development within the disciplines has gradually gained its prominence in bilingual and multilingual education (Goldenberg, 2010 ).

Complementary to the language and cognitive approach, the sociocultural approach contends literacy learning as a social issue, widely shaped by power, structure and ideology (Gee, 2015 ; Lea & Street, 2006 ). This approach highlights the role of learner agency and identity in transforming individual/community learning practices (Lillis & Scott, 2007 ). Academic literacy in this sense is viewed as a sociocultural construct imbued with meaning, value and emotions as a gateway for social access, power distribution and meaning reconstruction (Moje et al., 2008 ).

However, despite the various approaches to academic literacy teaching and learning, up-till-now, there still seems to be a paucity of research that can integrate these dimensions into effective intervention and research practices. Current researches on academic literacy development either take an interventionistic or descriptive approach. The former usually takes place within a concrete educational setting under the intention to uncover effective community teaching and learning practices (Engestrom, 1999 ). The later, on the contrary, often takes a more naturalistic or ethnographic approach with the hope to provide an in-depth account of individual/community learning practices (Lillis & Scott, 2007 ). These descriptions are often aligned to larger sociocultural contexts and the transformative role of learner agency in collective, object-oriented activities (Engeström, 1987 ; Wenger, 1998 ).

These different approaches to academic literacy development are influenced by the varying epistemological stances of the researcher and specific research purposes. However, all these approaches have pointed to a common conception of academic literacy as a multidimensional construct, widely shaped by the sociocultural and historical contexts. This complex and dynamic nature of literacy learning not only enables the constant innovation and expansion of academic literacy construct but also opens up the possibilities to challenge the preconceived notions of relevant research and pedagogical practices.

Based on these concerns, the study intends to conduct a critical review of the twenty years’ development of academic literacy research in terms of their definition of the academic literacy construct, research approaches, methodologies, settings and keywords with the hope to uncover possible developmental trends in interaction. Critical reflections are drawn from this systematic review to shed light on possible future research directions.

Through this review, we intended the address the following three research questions:

What is the construct of academic literacy in different approaches of academic literacy research?

What are the possible patterns of change in term of academic literacy research methods, approaches and settings over the past twenty years?

What are the main focuses of research within each approach of academic literacy development?

Methodology

The study adopts mixed methods to provide a systematic review of academic literacy research over the past twenty years. The rationale for choosing a mixed method is to integrate qualitative text analysis on the features of academic literacy research with quantitative corpus analysis applied on the initial coding results to unveil possible developmental trends.

Inclusion criteria

To locate academic literacy studies over the past twenty years, the researcher conducted a keyword search of ‘academic literacy’ within a wide range of databases within the realm of linguistic and education. For quality control, only peer-reviewed articles from the Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science) were selected. This initial selection criteria yielded 127 papers containing a keyword of ‘academic literacy’ from a range of high-quality journals in linguistics and education from a series of databases, including: Social Science Premium Collection, ERIC (U.S. Dept. of Education), ERIC (ProQuest), Taylor & Francis Online—Journals, Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, Informa—Taylor & Francis (CrossRef), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (Web of Science), ScienceDirect Journals (Elsevier), ScienceDirect (Elsevier B.V.), Elsevier (CrossRef), ProQuest Education Journals, Sage Journals (Sage Publications), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, JSTOR Archival Journals, Wiley Online Library etc. Among these results, papers from Journal of Second Language Writing, Language and Education, English for Specific Purposes, Teaching in Higher Education, Journal of English for Academic Purposes and Higher Education Research & Development are among the most frequent.

Based on these initial results, the study conducted a second-round detailed sample selection. The researcher manually excluded the irrelevant papers which are either review articles, papers written in languages other than English or not directly related to literacy learning in educational settings. After the second round of data selection, a final database of 94 high-quality papers on academic literacy research within the time span between 2002 and 2019 were generated. However, considering the time of observation in this study, only researches conducted before October 2019 were included, which leads to a slight decrease in the total number of researches accounted in that year.

Coding procedure

Coding of the study was conducted from multiple perspectives. Firstly, the study specified three different approaches to academic literacy study based on their different understandings and conceptualizations of the construct (Allison & Harklau, 2010 ). Based on this initial classification, the study then conducted a new round of coding on the definitions of academic literacy, research methods, settings within each approach to look for possible interactions. Finally, a quantitative keywords frequency analysis was conducted in respective approaches to reveal the possible similarities and differences in their research focus. Specific coding criteria are specified as the following.

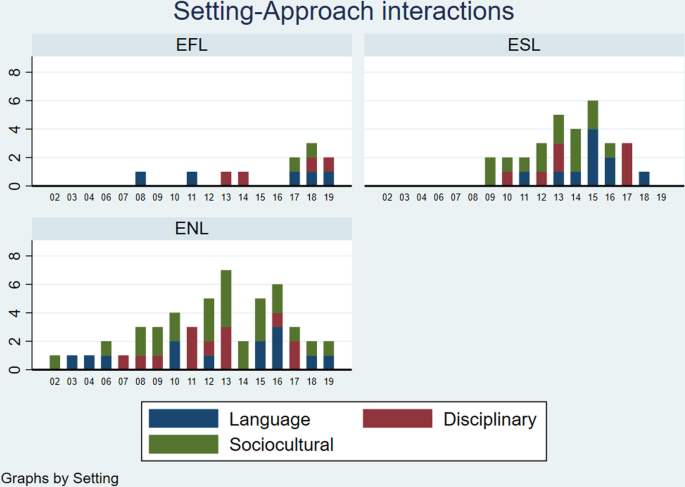

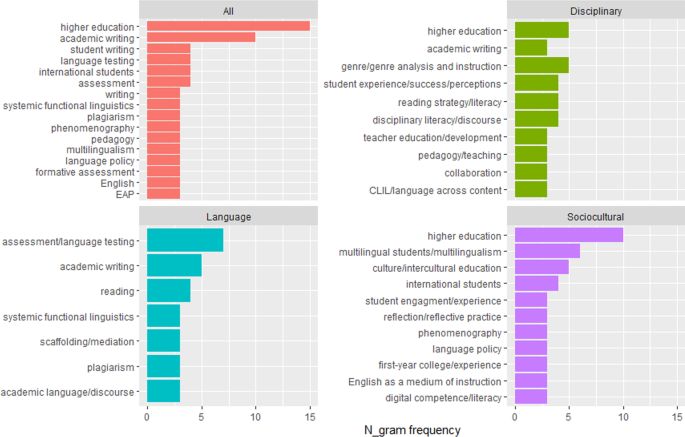

Firstly, drawing from Allison and Harklau ( 2010 ), the study classified all the researches in the database into three broad categories: language, disciplinary and sociocultural. While the language approach mainly focuses on the development of general or disciplinary-specific academic language features (Hyland, 2008 ), the disciplinary approach views academic literacy development as deeply embedded in the inquiry of disciplinary-specific values, cultures and epistemologies and can only be achieved via individual’s active engagement in disciplinary learning and inquiry practices (Moje, 2015 ). The sociocultural approach, largely influenced by the ‘academic literacies’ model (Lea & Street, 1998 ) contends that academic literacy development entails more than individual socialization into the academic community but is also closely related to issues as power, identity and epistemology (Gee, 2015 ; Lillis, 2008 ).