- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures—Challenges and Opportunities for China

- 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Rush Medical College, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois

- 2 Jefferson College of Population Health, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- 3 Institute for Healthcare Informatics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

- Original Investigation Application of Patient-Reported Outcome Measurements in Clinical Trials in China Hui Zhou, MSc; Mi Yao, MD; Xiaodan Gu, MBBS; Mingrui Liu, BP; Ruifeng Zeng, MBBS; Qin Li, MNS; Tingjia Chen, MD; Wen He, MD; Xiao Chen, PhD; Gang Yuan, MD, PhD JAMA Network Open

In 2016, The People’s Republic of China (PRC) formally passed the blueprint of Healthy China 2030, working toward the national goal of reaching a health standard on par with high-income countries by 2030. 1 In 2021, the Chinese government approved its 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the PRC, which includes a comprehensive strategy for advancing the quality of health care delivered by its national health system. 2 Yet, achieving this goal for China’s diverse population of 1.4 billion people is often complex, depending on employment, insurance type, geodemographic location, socioeconomic status, health care workforce supply, and many other variables. 3 In addition, PRC overall health care expenditures as a percentage of gross domestic product have increased by more than 42% since 2010, with the most currently available data showing 7.1% in 2020. 4

Over the past several years, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and derivative standardized patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have come into widespread use in other countries, including use, for example, as part of industry-sponsored clinical trials, population outcomes and comparative effectiveness research, health care delivery system program evaluation, and health insurance coverage determinations. 5 PROs are intended to provide objective and subjective assessments of a variety of dimensions, for example, health-related quality of life (eg, I do not socialize with friends much anymore), physical capacity (eg, I have difficulty walking 3 city blocks), mental and cognitive changes (eg, I sometimes have trouble concentrating), functional status (eg, I am unable to lift more than 5 pounds on the job), symptoms (eg, I experience moderate pain on most days), and overall well-being (eg, I am in poor health). Data on PROs are usually collected via standardized, psychometrically developed, and validated survey-type instruments that are often used by clinicians and researchers to evaluate health care delivery from the perspectives of individual patients. A PROM is often then generated, which is most typically a summary composite score of the individual PRO item response scores captured by the survey instrument.

Using a cross-sectional survey of interventional clinical trials using data from the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry and the ClinicalTrials.gov databases, Chinese researchers have evaluated the current applications of PROMs in clinical trials in the PRC. 6 As the authors note, this study documents the major increase from 2010 to 2020 in the number of clinical trials originating in the PRC that include the application and characteristics of PRO instruments and PROMs as primary and secondary outcomes in clinical trials across China. Only 29.7% of the selected 10 093 eligible PRO-related trials were categorized according to those that precisely listed PRO tools as outcomes, and 70.3% did not incorporate PROMs into the analyses. Also documented was a striking use imbalance by regional provincial locations, sponsors, clinical phases, and a relative lack of diversity of PROMs deployed. Most trials were in phase 4, performed in hospitals, and located in the most populous eastern Chinese provinces. The authors accurately conclude that there is a need for more widespread, robust, and correctly targeted use of standardized PROMs in clinical trials across the PRC.

In the important context of achieving its goals outlined in Healthy China 2030, the PRC has been aggressively evaluating the new improvements to the Chinese health care delivery system. Much is required to generate better quality of evidence and measurement of cost-effectiveness for guideline-directed medical therapies indicated for major chronic conditions and other, less common diseases. As such, the discovery of new insights reported by Zhou et al 6 requires more widespread and consistent deployment of well-constructed PROMs that provide the best understanding of which PROs matter most to patients and other subsequent relevant stakeholders interested in the resultant data.

The benefit of this well-done study by Zhou et al 6 is that it exposes both challenges and opportunities for the all-important future of PROM development and implementation—not just for the PRC, but for the entire international field. Fortunately, several reliable and publicly available resources and repositories for PROMs now exist widely, such as Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality-of-Life Instrument database, and Online Guide to Quality-of-Life Assessment. 5 , 6 The joint initiative between the Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments initiative and the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials initiative helps facilitate agreement among PROMs-focused stakeholders with regard to the selection of outcomes (eg, constructs or domains) and outcome measurement instruments for clinical trials. 7

Measure development and evaluation standards are also in use by consensus-driven groups (eg, the National Quality Forum) for the various and complex design domains of true PROMs, including content validity (including face validity), structural validity, internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, hypotheses testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity, and responsiveness. Initial PROM development and subsequent evaluation should include a formal evidence review and standardized quality of evidence grading process for each PROM item property, taking into account the number of studies, the methodologic quality of the studies, and the consistency of the results of the measurement properties. 5 Several sophisticated statistical-based methods are also often required, such as systematic review, meta-analysis, interrater reliability, internal consistency, factor analysis, analysis of variance, bayesian estimation, risk adjustment, and exclusion and missing data analysis. From empirical data generated through PROMs, it is now also becoming important to determine causal relationships between changes in PROs to generalizable improvements in at least 1 health care delivery system structure, process, intervention, or service.

Data for PROMs generated through traditional methods, such as self-reported questionnaires, structured interviews, and clinical assessments during patient encounters, is rapidly moving toward electronic data capture and storage in patient records. PROM data are now often collected through digital health interfaces that automate accurate and complete response capture and interoperable data transmission to electronic health records, clinical registries, and data analytic platforms. Translations of country- and language-specific PRO instruments may require additional psychometric testing that is appropriately sensitive to racial, ethnic, and cultural nuances of different target populations. As such, the generation of PROMs is becoming more resource intensive in terms of development, field testing, and ongoing evaluation, such as detection of changes consistent with improvement or worsening in specific and aggregate patient health outcomes.

Most recently, for-profit digital health firms have aggressively entered this market, touting sophisticated and parsimonious measure development and field-testing capability; robust interoperable data science-driven storage and access platforms; advanced data analytical expertise (eg, supervised machine learning and artificial intelligence); patient-centered interfaces for meaningful, team-based shared decision-making; and cost-effectiveness evaluation methods for assessing precision and multifactorial health outcomes. Hence, the standards generated today by more traditional stakeholders, such as regulators, policy-makers, health technology assessment authorities, and researchers may become less relevant and outdated for future PROM developments.

All of these diverse groups are necessary for the emergence of new tenets for a global learning health system necessary to achieve the worldwide goal of improving personalized population health. Building on and expanding these extensive advances should not, therefore, require the invention of a new wheel.

Published: May 11, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.11652

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2022 Casey DE Jr. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Donald E. Casey Jr, MD, MPH, MBA, Department of Internal Medicine, Rush Medical College, 1717 W Congress Pkwy, 10th Floor, Chicago, IL 60612 ( [email protected] ).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Casey reported being an active member of National Quality Forum Patient Experience and Function Committee and does not receive any financial remuneration for its activities.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this commentary represent those of the author alone and should not be interpreted as policy of the National Quality Forum.

See More About

Casey DE. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures—Challenges and Opportunities for China. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2211652. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.11652

Manage citations:

© 2024

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Committee to Examine the Methodology for the Assessment of Research-Doctorate Programs; Ostriker JP, Kuh CV, editors. Assessing Research-Doctorate Programs: A Methodology Study. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003.

Assessing Research-Doctorate Programs: A Methodology Study.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

4 Quantitative Measures

This chapter proposes and describes the quantitative measures relevant to the assessment of research-doctorate programs. These measures are valuable because they

- Permit comparisons across programs,

- Allow analyses of the correlates of the qualitative reputational measure,

- Provide potential students with a variety of dimensions along which to compare program characteristics, and

- Are easily updateable so that, even if assessing reputation is an expensive and time-intensive process, updated quantitative measures will allow current comparisons of programs.

Of course, quantitative measures can be subject to distortion just as reputational measures can be. An example would be a high citation count generated by a faulty result, but these distortions are different from and may be more easily identified and corrected than those involving reputational measures. Each quantitative measure reflects a dimension of the quality of a program, while reputational measures are more holistic and reflect the weighting of a variety of factors depending on rater preferences.

The Panel on Quantitative Measures recommended to the Committee several new data-collection approaches to address concerns about the 1995 Study. Evidence from individuals and organizations that corresponded with the Committee and the reactions to the previous study both show that the proposed study needs to provide information to potential students concerning the credentials required for admission to programs and the context within which graduate education occurs at each institution. It is important to present evidence on educational conditions for students as well as data on faculty quality. Data on post-Ph.D. plans are collected by the National Science Foundation and, although inadequate for those biological sciences in which postdoctoral study is expected to follow the receipt of a degree, they do differentiate among programs in other fields and should be reported in this context. It is also important to collect data to provide a quantitative basis for the assessment of scholarly work in the graduate programs.

With these purposes in mind, the Panel focused on quantitative data that could be obtained from four different groups of respondents in universities that are involved in doctoral education:

University-wide. These data reflect resources available to, and characteristics of, doctoral education at the university level. Examples include: library resources, health care, child care, on-campus housing, laboratory space (by program), and interdisciplinary centers. Program-specific. These data describe the characteristics of program faculty and students. Examples include: characteristics of students offered admission, information on program selectivity, support available to students, completion rates, time to degree, and demographic characteristics of faculty. Faculty-related. These data cover the disciplinary subfield, doctoral program connections, Ph.D. institution, and prior employment for each faculty member as well as tenure status and rank. Currently enrolled students. These data cover professional development, career plans and guidance, research productivity, research infrastructure, and demographic characteristics for students who have been admitted to candidacy in selected fields.

In addition to these data, which would be collected through surveys, data on research funding, citations, publications, and awards would be gathered from awarding agencies and the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), as was done in the 1995 Study.

The mechanics of collecting these data have been greatly simplified since 1993 by the development of questionnaires and datasets that can be made available on the Web as well as software that permits easy analysis of large datasets. This technology makes it possible to expand the pool of potential raters of doctoral programs.

- MEASURABLE CHARACTERISTICS OF DOCTORAL PROGRAMS

The 1995 Study presented data on 17 characteristics of doctoral programs and their students beyond reputational measures. These are shown in Table 4–1 . Although these measures are interesting and useful, it is now possible to gather data that will paint a far more nuanced picture of doctoral programs. Indicators of what data would be especially useful have been pointed out in a number of recent discussions and surveys of doctoral education.

TABLE 4–1

Data Recommended for Inclusion in the Next Assessment of Research-Doctorate Programs. Bolded Elements Were Not Collected for the 1995 Study.

Institutional Variables

In the 1995 Study, data were presented on size, type of control, level of research and development funding, size of the graduate school, and library characteristics (total volumes and serials). These variables paint a general picture of the environment in which a doctoral program exists. Does it reside in a big research university? Does the graduate school loom large in its overall educational mission? The Committee added to these measures that were specifically related to doctoral education. Does the institution contribute to health care for doctoral students and their families? Does it provide graduate student housing? Are day care facilities provided on campus? All these variables are relevant to the quality of life of the doctoral student, who is often married and subsisting on a limited stipend.

The Committee took an especially hard look at the quantitative measures of library resources. The number of books and serials is not an adequate measure in the electronic age. Many universities participate in library consortia and digital material is a growing portion of their acquisitions. The Committee revised the library measures by asking for budget data on print serials, electronic serials, and other electronic media as well as for the size of library staff.

An addition to the institutional data collection effort is the question about laboratory space. Although this is a program characteristic, information about laboratory space is provided to the National Science Foundation and to government auditors at the institutional level. This is a measure of considerable interest for the laboratory sciences and engineering, and the Committee agreed that it should be collected as a possible correlate of quality.

Program Characteristics

The 1995 Study included data about faculty, students, and graduates gathered through institutional coordinators, Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) and the NSF Doctorate Records File (DRF). For the humanities, it gathered data on honors and awards from the granting organizations. Most of the institutional coordinators did a conscientious and thorough job, but the Committee believes that it would be helpful to pursue a more complex data-collection strategy that would include a program data collector (usually the director of graduate studies) in addition to the key institutional coordinator, a questionnaire to faculty, and questionnaires to students in selected programs. This approach was tested with the help of the pilot institutions. The institutional coordinator sent the NRC e-mail addresses of respondents for each program. The NRC then provided the respondent a password and the Web address of the program questionnaire. A similar procedure was followed for faculty whose names were provided by the program respondents. Copies of the questionnaires may be found in Appendix D .

In 1995, programs were asked for the number of faculty engaged in doctoral education and the percentage of faculty who were full professors. They were also asked for the numbers of Ph.D.s granted in the previous 3 years, their graduate enrollment both full-time and part-time, and the percentage of females in their total enrollment. Data on doctoral recipients, such as time to degree and demographic characteristics, came entirely from the DRF and represented only those who had completed their degrees.

The Committee believed that more informative data could be collected directly from the program respondents. Following the 1995 Study, a number of questions had been raised about the DRF data on time to degree. More generally, the Committee observed that data on graduates alone gave a possibly biased picture of the composition and funding of students enrolled in the program. The program questionnaire contains questions that are directly relevant to these concerns.

In the area of faculty characteristics, the program questionnaire requests the name, e-mail address, rank, tenure status, and demographic characteristics (gender, race/ ethnicity, and citizenship status) of each faculty member associated with the program. Student data requested include characteristics of students offered admission, information on program selectivity, support available to students, completion rates, and time to degree. It also asks whether the program requires a master's degree prior to admission to the doctoral program, since this is a crucial consideration affecting the measurement of time to degree. The questionnaire also permits construction of a detailed profile of the percentage of students receiving financial aid and the nature of that aid. Finally, the questionnaire asks a variety of questions related to program support of doctoral education: whether student teaching is mentored, whether students are provided with their own workspaces, whether professional development is encouraged through travel grants, and whether excellence in the mentoring of graduate students by faculty is rewarded. These are all “yes/no” questions that impose little respondent burden.

Faculty Characteristics

In the 1995 Study, a brief faculty questionnaire was administered to the raters who produced the reputational rankings. These raters were drawn from a sample of faculty nominated by their institutional coordinators. The sample size reflected the number of programs in each field. The brief questionnaire asked raters the year, institution, and date of their highest degree as well as their current field of specialization. The Committee believes that the faculty questionnaire should be modified to collect certain other data. For example, the university origins of current faculty are a direct measure of which graduate programs are training Ph.D.s who become faculty at research universities. Data on date of degree would also permit a comparison of origins of recently hired faculty as compared to faculty hired, for example, more than 20 years ago. Although subfield data were collected for the 1995 Study, they were not used. They could be useful in improving program descriptions for potential graduate students and for assuring that specialist programs are rated by knowledgeable peers in the same specialty.

The Committee also believes that additional questions asked of faculty could permit a richer description of interdisciplinarity. For example, faculty could list all programs in which they have participated, either by teaching or serving on dissertation committees. Many faculty would be listed as members of more than one graduate program, and for the purposes of the reputational survey, the Committee recommends that they be listed as program faculty for all programs with which they are associated. To avoid the possibility of double counting the output of productive faculty, objective measures should be attributed pro rata among the various programs in which they are listed. The decision as to how to prorate an effort should be made by the faculty member with guidance that they should try to describe how time devoted to doctoral education (teaching and student mentoring) has been allocated among the programs for the past 3-year period.

The Committee was concerned that programs might want to associate a well-known faculty member with as many programs as possible in order to boost its rating, even if he or she were not involved with the program. Allocation of publications should serve to discourage this behavior.

Student Characteristics and Views

Student observations have not been a part of past assessments of research-doctorate programs. Past studies have included data about demographic characteristics and about sources of financial support of Ph.D. recipients drawn from the DRF and about graduate student enrollment collected from the doctoral institutions. Another student measure was “educational effectiveness of the doctoral program,” and for reasons discussed in Chapter 6 , the Committee is recommending the elimination of this measure. The approach for measuring student processes and outcomes is discussed in Chapter 5 .

- PILOT TRIAL FINDINGS

The pilot trials were conducted over a 3-month period. The most important finding was that 3 months was barely sufficient for dealing with the study questionnaires. The full study should probably allow at least 4–6 months for data submission. The answers to many of the questions are prepared for other data collection efforts, but additional time is needed to customize answers to fit the taxonomy and to permit time for follow-up with nonrespondents.

All institutions carried out the trial through a single point of contact for the campus. This single point of contact worked with institutional research offices and program contacts to answer questions as well as interacted with NRC staff to assure that data definitions were uniform.

Electronic data collection worked well for institutions, programs, and faculty. We learned that it was better not to provide a hard copy alternative (as contrasted to Web response), since hard copy data simply had to be re-entered in databases once it was received by the NRC. All the pilot institutions store and access institutional and program data electronically. E-mail is the standard mode of communication with faculty and the rates of faculty response (60 percent) were high for a one-wave administration.

The Committee also learned that more precise definitions are needed to guide respondents. For example, when asking for data about “first-year doctoral students” a distinction may be needed about whether the students have a master's in the field. Care needs to be taken not to include terminal master's students, and precise definitions of “full-time” and “part-time” should be included.

The Committee learned the following from the questionnaire responses:

Institutional Questionnaire

- Library expenditures: Not all institutions separate e-media expenditures from print expenditures.

- Space: The questionnaire needs to provide guidance about how to allocate shared space. Answers to space questions also depend on how well the institution's programs fit the taxonomy. If the fit is poor, the allocation of space is arbitrary.

- Graduate student awards and support are more appropriately queried at the program level.

Program questionnaire

- Programs had difficulty filling out the inception cohort matrix but believed they could have done it if they had had more lead time.

- Programs knew who their competitors were for doctoral students.

- Programs that required GREs knew the averages and minima. For programs that do not require GREs, it would be helpful to ask what percentage of applicants submit GRE scores as well as report averages and minima only for those programs that are above a certain level (e.g., 80 percent).

- Requests for faculty lists and faculty data should be separate from requests for other program data.

Faculty questionnaire

- E-mail notifications must have a sufficiently informative subject heading so that they are not mistaken for spam.

- Questionnaires should contain a due date.

- Faculty associated with more than one program should be asked to fill out only one questionnaire. The NRC needs to develop procedures to duplicate information for the other programs with which a faculty member is associated.

- Some faculty identified their program by a name other than that of the program that submitted their name. A procedure must be developed to resolve this problem.

Each pilot institution was asked to provide comments on the questionnaires. These comments, some of which are reported above, will be used as background material for the committee that conducts the full study. Draft questionnaires for the full study should be reviewed by a number of institutional researchers from a diverse set of institutions as well as by survey researchers.

Data Collected from Other Sources

The Committee recommends that most of the quantitative data presented in the 1995 Study from other sources be collected again. These include: publication and citation data from ISI, data on research grants from government agencies and large private foundations, data on books from the Arts and Humanities Citation Index, and data on awards and honors from a large set of foundations and professional societies. Student data from the Doctorate Record File should be considered for inclusion but checked for inconsistencies against institutional and program records. In the case of inconsistencies, a validation process should be designed.

- RECOMMENDATIONS

The Committee recommends that the data listed in Bold type in Table 4–1 be added to the quantitative measures that were collected for the 1995 Study.

- Cite this Page National Research Council (US) Committee to Examine the Methodology for the Assessment of Research-Doctorate Programs; Ostriker JP, Kuh CV, editors. Assessing Research-Doctorate Programs: A Methodology Study. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. 4, Quantitative Measures.

- PDF version of this title (7.5M)

In this Page

Other titles in this collection.

- The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health

Recent Activity

- Quantitative Measures - Assessing Research-Doctorate Programs Quantitative Measures - Assessing Research-Doctorate Programs

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Do successful PhD outcomes reflect the research environment rather than academic ability?

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected] , [email protected]

Affiliation Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition (IPAN), School of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Health, Office of Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, Australia

- Daniel L. Belavy,

- Patrick J. Owen,

- Patricia M. Livingston

- Published: August 5, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Maximising research productivity is a major focus for universities world-wide. Graduate research programs are an important driver of research outputs. Choosing students with the greatest likelihood of success is considered a key part of improving research outcomes. There has been little empirical investigation of what factors drive the outcomes from a student's PhD and whether ranking procedures are effective in student selection. Here we show that, the research environment had a decisive influence: students who conducted research in one of the University's priority research areas and who had experienced, research-intensive, supervisors had significantly better outcomes from their PhD in terms of number of manuscripts published, citations, average impact factor of journals published in, and reduced attrition rates. In contrast, students’ previous academic outcomes and research training was unrelated to outcomes. Furthermore, students who received a scholarship to support their studies generated significantly more publications in higher impact journals, their work was cited more often and they were less likely to withdraw from their PhD. The findings suggest that experienced supervisors researching in a priority research area facilitate PhD student productivity. The findings question the utility of assigning PhD scholarships solely on the basis of student academic merit, once minimum entry requirements are met. Given that citations, publication numbers and publications in higher ranked journals drive university rankings, and that publications from PhD student contribute approximately one-third of all research outputs from universities, strengthening research infrastructure and supervision teams may be more important considerations for maximising the contribution of PhD students to a university’s international standing.

Citation: Belavy DL, Owen PJ, Livingston PM (2020) Do successful PhD outcomes reflect the research environment rather than academic ability? PLoS ONE 15(8): e0236327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327

Editor: Sergi Lozano, Universitat de Barcelona, SPAIN

Received: October 3, 2019; Accepted: July 3, 2020; Published: August 5, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Belavy et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Participants did not give consent for their data to be published in online databanks and data are accessible with appropriate ethical approvals. Interested parties may contact the authors and/or the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee [email protected] to gain access to the data.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

A research doctorate degree comprises a process of independent research that produces an original contribution to knowledge [ 1 ]. The Australian Commonwealth Government supports [ 2 ] both domestic and overseas students undertaking research doctorate degrees, known as PhDs. These scholarships, which comprise a stipend for three years, are competitive. For this reason, when students apply for scholarships for their PhD studies, prior academic performance and research training play a key role in deciding whether the applicant receives a scholarship. However, is assigning scholarships predominately on the basis of academic grades and previous research experience effective in determining who will succeed?

A university’s international and national ranking is important for its reputation and marketing to prospective students [ 3 ]. Citation rates, number of publications and impact factor of journals faculty publish in, influence the ranking of a university. The Quacquarelli Symonds University Rank [ 4 ] is weighted 30% by the number of citations per faculty member, the Times Higher Education World Ranking [ 5 ] 30% by the number of citations and 6% by the number of publications per academic, and the Academic Ranking of World Universities [ 6 ] 20% by number of highly cited researchers, 20% by number of papers published in Nature or Science and 20% by the number of publications in total.

PhD students are important drivers of research outputs from universities, with one analysis [ 7 ] showing that one-third of research publications was from doctoral students. It is important to consider to what extent the procedures by which universities select students who go on to produce higher numbers of highly cited publications in high impact journals. We are not aware of any prior research that has examined this topic.

Waldinger [ 8 ] showed that the quality of academic staff (in departments of mathematics at German universities in the 1930s) influenced the likelihood of whether a doctoral student would become a full professor later in their career. Waldinger also showed that the amount of citations the scientific work of a doctoral student received through their entire subsequent scientific career was influenced by the status of their supervisor. Other factors, such as, the reputation of a department [ 9 ], the reputation the group leader [ 10 ], and access to resources and equipment [ 11 ], the number of full-professors on staff [ 12 ] influenced the research output of the academics involved in that group. Less information is available on the impact of student academic ability or prior research training on PhD outcomes: one analysis found that the reputation of a given department was more important for employment outcomes post-PhD than the accomplishments of the student during their studies [ 13 ]. Overall, the evidence available implies that the research environment may have an inordinate impact on the PhD student outcomes (e.g. citations, number of publications, impact factor of journals of those publications).

Here we examine the relationship between information known about applicants and their proposed supervisory teams at the time of scholarship application with the subsequent research outputs, as measured by number of citations, number of publications and the impact of journals of those publications.

Materials and methods

Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee reviewed this project (2019–191) and found it to be compliant with the Ethical Considerations in Quality Assurance and Evaluation Activities guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and determined that no further ethics review was required. Consent was not obtained and the data analysed anonymously.

Over a four year period, 2010–2013, 324 PhD scholarship applications were submitted to the Faculty of Health at one university in Australia ( Fig 1 ). In these applications, data were collated on:

- the grade the student achieved for their prior research training degree and their rank in this degree (top, middle, bottom third of first class honours or second class honours; or their equivalency to this),

- the grade point average achieved in their undergraduate degree (ranked on a scale of 1 to 5 with 5 = high distinction grade point average plus prizes awarded, 4 = high distinction grade point average, 3 = distinction, 2 = credit, 1 = pass).

- whether the applicant had published in a scientific journal (‘yes’ or ‘no’)

- research environment: whether the primary supervisor was located in a strategic research centre or institute within the university (‘yes’ or ‘no’).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

In 2010 to 2013, applications were submitted for PhD scholarships and in July 2018 data on publication outputs and completion of degree were obtained. Overall, 11 students did not enrol in PhD despite an offer with scholarship being made and 37 withdrew from their studies after starting.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.g001

At the time of ranking for scholarships, the review panel scored each application on the basis of their academic merit and the research experience, alignment of the proposed research with the strategic research goals of the Faculty and university, and the experience of the supervisory team (as expressed by prior PhD completions, student progress, external grants, previous student publications, supervisor track record). In July 2018, these scores were reviewed by two independent assessors experienced in the scholarship ranking process and consensus was attained. Subsequent to this, following variables were generated:

- quartile of the academic merit scores in which each student was located.

- strategic alignment score achieved maximum points (‘yes’ or ‘no’). The presence or absence of a maximum score was taken for this variable as there were few instances of low scores on this criterion and data were skewed to the maximum score.

- supervisor team scores achieved maximum points (‘yes’ or ‘no’). The presence or absence of maximum score was taken for this variable as there were few instances of low scores on this criterion and data were skewed to the maximum score.

- level of academic appointment of the primary supervisor (lecturer/senior lecturer, associate professor, or full professor)

Data on whether the applicant subsequently enrolled (if ‘no’ they were excluded from further analysis; Fig 1 ), whether they completed their studies (‘yes’ or ‘no’), and whether the student received a scholarship to support his/her study (‘yes’ or ‘no’) obtained from another university database.

The university tracks publication outputs of its faculty and students. In July 2018, these data were obtained to link the number of publications by the student with their primary supervisor, the impact factor of the journals in which these publications appeared, and the number of citations received by the publications in Web of Science by the cut-off data of data access. Publications were matched on the basis of student name and primary supervisor name. If a change of primary supervisor occurred during student candidature, publication matches with the new primary supervisor were included as well. If the student had enrolled in a PhD but achieved no publications within the time-period examined, data were coded as zero publications, zero citations and zero average impact factor. Datasets were merged in using custom written code implemented in the 'R' statistical environment (version 3.4.0 https://www.r-project.org/ ). Where repeat applications were submitted in subsequent years by the same person, only the data available at the first application was used in further analysis. Prior to statistical analysis, all identifying information was removed.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software version 15 (College Station TX, USA). Univariate associations between continuous dependent variables (number of publications, number of citations, number of citations per publication, average publication impact factor) and explanatory variables were assessed by the Kruskal-Wallis H test or Mann-Whitney U test (both non-parametric tests), as well as one-way analysis of variance and t-tests (both parametric tests). Univariate associations between withdrawal (yes/no) and independent variables were assessed by penalized maximum likelihood [ 14 , 15 ] logistic regression. We categorised the explanatory variables as follows: student specific factors (student research degree rank, student undergraduate rank, student prior publication, student academic merit), supervisor specific factors (supervisor located in a strategic research centre, supervisor academic level, supervisor team scores achieved maximum points), research topic related factors (strategic alignment score achieved maximum points), and whether a scholarship was awarded. To investigate which variables were more important than others for PhD student outcome metrics, factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) as well as stepwise multiple linear regression models with both forward and backward selection were used to assess the association between the dependent variables and the independent variables. We further conducted factorial ANOVA to assess the association between the dependent variables and independent variables. Stepwise penalized maximum likelihood logistic regression models were used to predict withdrawal from PhD (yes/no) based on independent variables. An adjusted alpha level of 0.10 to enter and 0.20 to remove were used for all step-wise regression models. An alpha-level of 0.05 was adopted for all other statistical tests, including the assessment of the final step-wise regression models.

Primary analyses involved 198 students who enrolled in PhD (61% of 324 applications; Fig 1 ). The descriptive data on the characteristics of the students are shown in Table 1 . In the whole cohort, median (25 th percentile, 75 th percentile) and mean (standard deviation; SD) number of publications were 1.0 (0.0, 3.0) and 2.8 (4.4), impact factor 0.86 (0.00, 2.61) and 1.59 (2.36), citations per publication 0.0 (0.0, 4.5) and 3.5 (7.4) and total citations 0.0 (0.0, 17.0) and 19.6 (49.8). S1 Table presents the stability of the explanatory variables across each year of student applications. The relationship between ranking criteria and PhD student output metrics are shown in Table 2 (non-parametric analyses) and Table 3 (parametric analyses). Findings of both non-parametric and parametric analyses were similar. Non-parametric ( S1 Table ) and parametric ( S2 Table ) effect sizes as well as variability among variables by year of application ( S3 Table ) are reported in the data supplement.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.t003

Number of publications

On univariate analysis (Tables 2 and 3 , Fig 2 ), primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre (non-parametric and parametric both: P≤0.014), supervisory teams who received a maximum score (both: P≤0.014), being awarded a scholarship (both: P<0.001), student academic merit score (non-parametric: P = 0.017, parametric: P = 0.758) were associated with this outcome, but student undergraduate performance (both: P≥0.588), student research training degree outcome (e.g. first-class honours upper band; both: P≥0.262), research topic (both: P≥0.347), primary supervisor academic level (both: P≥0.107) were not.

Data are non-parametric effect sizes (95% confidence interval) for each parameter. See S1 Table for more detail and Tables 2 and 3 for more detail on each parameter. Student academic merit score from scholarship panel ranking showed moderate effect sizes, yet these students received 46% of all scholarships and multivariate analyses showed that receiving a scholarship was more important than the student's academic merit (see Results for more detail). Other markers of student ability and prior research training were unrelated to outcomes from the PhD. The score assigned by the panel to the alignment of the research topic with research priorities was unrelated to outcomes.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.g002

Step-wise regression models ( Table 4 ) showed that receiving a scholarship (P = 0.001), primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre (P = 0.018) remained in final model for number of publications, and whilst 'research topic' remained in the final model, it was not significant (P = 0.076). Factorial ANOVA ( S4 Table ) yielded similar results (having a scholarship, supervisory teams who received a maximum score, primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre were associated, but not student related variables).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.t004

Number of citations

On univariate analysis (Tables 2 and 3 , Fig 2 ), primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre (non-parametric and parametric P both≤0.010), supervisory teams who received a maximum score (both: P≤0.012), being awarded a scholarship (both: P<0.001) were associated with this outcome, but student undergraduate performance (both: P≥0.668), student research training degree outcome (e.g. first-class honours upper band; both: P≥0.237), student academic merit score (both: P≥0.080), research topic (both: P≥0.202), primary supervisor academic level (both: P≥0.482) were not.

Step-wise regression models ( Table 4 ) showed that supervisory team who received a maximum score (P = 0.039) and the receiving a scholarship (P = 0.053), but in this case the scholarship award was not significant. Factorial ANOVA ( S4 Table ) yielded similar results (having a scholarship and supervisory teams who received a maximum score were associated, but not student related variables).

Citations per publications

On univariate analysis (Tables 2 and 3 , Fig 2 ), primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre (non-parametric and parametric P both P≤0.009), supervisory teams who received a maximum score (non-parametric: P<0.001, parametric: P = 0.159), being awarded a scholarship (both: P≤0.048) were associated with this outcome, but student undergraduate performance (both: P≥0.640), student research training degree outcome (e.g. first-class honours upper band; both: P≥0.668), student academic merit score (both: P≥0.082), research topic (both: P≥0.185), primary supervisor academic level (both: P≥0.160) were not.

Step-wise regression models ( Table 4 ) showed that primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre (P = 0.079) and supervisory team achieving maximum score (P = 0.087) remained in the final model, but neither terms were significant. Factorial ANOVA ( S4 Table ) yielded similar results (having a scholarship and supervisory teams who received a maximum score approached, but did not reach, significance).

Average impact factor

On univariate analysis (Tables 2 and 3 , Fig 2 ), primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre (non-parametric and parametric P both P≤0.001), supervisory teams who received a maximum score (both: P≤0.005), being awarded a scholarship (both: P<0.001), student academic merit score (both: P≤0.005), were associated with this outcome, but student undergraduate performance (both: P≥0.077), student research training degree outcome (e.g. first-class honours upper band; both: P≥0.238), research topic (both: P≥0.161), primary supervisor academic level (both: P≥0.125) were not.

Step-wise regression models ( Table 4 ) showed that receiving a scholarship (P<0.001) and primary supervisor being located in a strategic research centre (P = 0.051) remained in the final model, with the latter not achieving statistical significance. Factorial ANOVA ( S4 Table ) yielded similar results (having a scholarship was significant, but supervisor related variables approached, but did not reach, significance; student related variables were not significant).

Drop-out from PhD

Odds ratios for student attrition is shown in Table 1 . Students were more than two times more likely to withdraw from their PhD when the supervisory team did not achieve maximum score (odds ratio [95% confidence interval] 2.88[1.39, 5.93], P = 0.004) or a scholarship was not awarded (odds ratio [95% confidence interval] 3.04[1.37, 6.73], P = 0.006). No other independent variables significantly predicted the likelihood of withdrawal.

The final multiple logistic regression model (χ 2 = 13.80, df = 3, P = 0.003) for predicting withdrawal from PhD included maximum supervisory team score (OR = 3.29, P = 0.013; i.e. lower risk of withdrawal when the supervisor score was maximum), student undergraduate degree grades (OR = 0.58, P = 0.047; i.e. reduced risk for each GPA rank lower) and receiving a scholarship (OR = 2.30, P = 0.090; i.e. lower risk when scholarship received), albeit the latter was not significant.

Associations between explanatory variables

Students in the highest quartile of academic merit received the most (42%) of all scholarships awarded. Of those in the highest quartile of academic merit, 79% received scholarships, compared to 62% in the second quartile, 20% in the third quartile and 22% in the lowest quartile.

Students who received a scholarship were more often supervised by strong supervisory teams (χ 2 = 9.346, P = 0.002; Table 5 ) and by supervisors who were located in a strategic research centre (χ 2 = 8.225, P = 0.004; Table 5 ). Supervisors who were in a strategic research centre were more likely to attract students in the highest quartile of academic merit (χ 2 = 3.899, P = 0.048; Table 6 ). Supervisory teams who received a maximum score were more likely to attract students in the highest quartile of academic merit (χ 2 = 10.147, P = 0.001; Table 6 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.t005

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.t006

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first analysis of PhD student outcomes in relation to their research environment, their academic abilities and prior research training. The key finding was that the 'research environment', such as whether the supervisor was in a research centre or institute and the research experience of the supervision team, were most significant predictors of, with the largest effect sizes for, student outcomes. In contrast, the students' previous academic outcomes and previous research training were not predictors. Receiving a PhD scholarship had a significant influence on positive student outcomes and was more important than students being judged as having the highest academic merit. Receiving a scholarship occurred more frequently in students tied to stronger supervisory teams and supervisors in strategic research centres.

Entry to a PhD is typically restricted to those students with a minimum grade in a prior Masters or Honours degree [ 16 ]. At our university, prospective PhD students are required to have completed a research project with a dissertation of at least 25% of one year full-time study at Honours or Masters level and their grade needs to have been at least 70%. Our findings suggest that once students meet the minimum academic ability for entry into PhD, any further ability or research training above that does not influence the outcome of their PhD. This is in line with findings that scientist’s intelligence quotient does not correlate with their citation rates [ 17 ].

By contrast, it is the research environment in which the student is embedded that is decisive for the outcomes of their PhD; including the strength of their supervisory team. This is in line with the hypothesis of “accumulative advantage”, also known as “Matthew effects” in science [ 18 ] where differences between scientists at an early stage of their career become reinforced over time [ 19 ]. The standing of a PhD supervisor directly influences [ 8 ] the future career trajectory, and number of citations, their students receive throughout their career. Also, the standing of a department influences the future employment chances of its PhD graduates, on average, more than the individual achievements of those students [ 13 ]. The impact of teacher quality is seen in other areas of education [ 20 , 21 ], although ‘PhD supervisor quality’ is assessed differently to teacher quality in school and undergraduate education.

There are other factors known to impact the number and impact of publication outputs. Research collaboration has clearly been shown to lead to higher impact publications [ 22 – 25 ]. In the health-sciences field, publications of higher levels of evidence [ 26 ] are more likely to be cited. Similarly interventional (rather than observational) and prospective (rather than retrospective) studies [ 25 , 27 ], as well as randomised controlled trials and basic science papers [ 28 ] are more likely to be cited. Papers published in high impact factor journals will be more often cited simply for that reason [ 23 , 25 ]. We argue these factors are more likely to be determined by the research culture in which the student are embedded, as opposed to being determined by the student alone.

We also showed that receiving a PhD scholarship contributed to the students’ outcomes, in particular with more publications arising, more citations higher impact factor journals. In step-wise regression, we found that impact of the scholarship persisted for the number of publications and average impact factor of the journals in which the students published. This finding is in line with prior work [ 29 ] that showed PhD students receiving scholarships to support their studies published more peer reviewed papers. Similar to prior work [ 29 ], our results showed that receiving a scholarship was also associated with lower withdrawal rates.

Students were awarded scholarships based on their prior academic performance [ 30 ]. At this university, whilst the student’s academic merit contributed to 60% of their total ranking score, in practice this was the most decisive factor in determining which applicants were offered scholarships first. We show here, however, that the most significant attributes for PhD success were research environment and the performance metrics of the supervision team. How these attributes may influence employment opportunities post PhD also warrants further investigation.

Strengthening the research environment is also worthy of further investigation. Prior work [ 12 ] has shown that very few university departments rely solely on a small number of high-performing researchers for its research productivity. We show here that supervisor team quality has a key impact on the PhD student’s outcomes. Therefore, having more highly trained researchers is likely to lead to overall higher research student productivity, such as in having a higher percentage of faculty members who are at full-professor level [ 12 ]. Strategies for strengthening the research capacity of academic staff and potential supervisors include [ 31 ] structured research mentoring of academic staff, formal requirements for further academic research training.

The strengths of this analysis include being a prospective analysis of outcomes based on data that were known at the time of student selection. The limitations of the analysis were that it was focussed on one faculty at one university. It was not possible to conduct this analysis more widely at our university or at other universities as not all faculties and universities collate the same data on their PhD applicants. It would be relevant to examine such patterns at a wider range of universities, however obtaining such data from other universities is further complicated by data from scholarship ranking being confidential internal university information. Whilst this study was comprised one university, we believe its findings can easily be extrapolated to other regions of Australia and/or the world. Furthermore, we focussed on outcomes from PhDs that relate to university ranking procedures. Other outcomes, such as employment achieved post-PhD, student satisfaction, mental health are important to consider more widely.

Conclusions

In conclusion, to best of our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the relative importance of the environment versus student ability in the allocation and outcomes of their PhD. Our key finding was that the research environment is likely more important for supporting PhD students to produce larger numbers of highly cited publications in higher impact journals. Once the minimum level of academic ability and research training is met for entry to PhD, working with a strong research focussed supervisory team, being embedded in a research intensive institute, and receiving a scholarship are also important factors for publication and citation outcomes.

Supporting information

S1 table. non-parametric effect sizes between the ranking criteria of the 198 unique phd applications and researcher metrics..

Data are Cohen’s d. Bold = P<0.05. GPA: Grade point average.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.s001

S2 Table. Parametric effect sizes between the ranking criteria of the 198 unique PhD applications and researcher metrics.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.s002

S3 Table. Variability among variables by year of application.

Dependent variables are mean (standard deviation), expect withdrawing from PhD which are number (percentage within year). Explanatory variables are number (percentage within year). GPA: Grade point average.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.s003

S4 Table. Results from factorial ANOVA.

Data are F-value (corresponding P-value). ANOVA fits explanatory variables sequentially to the dependent variables. Explanatory variables were fitted to the dependent variables in the order above (i.e. top variable at left fitted first, followed by the second to top variable). This therefore accounted for potential association of student related factors first to PhD outcomes, with then having a scholarship and then supervisor related factors considered. Despite accounting for student related variables first, having a scholarship and supervisor quality were most consistently associated with outcomes from a student’s PhD.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236327.s004

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Grant Michie, Rachelle DeBrito and their teams for assistance with access to enrolment and publication output data, Steve Sawyer for assistance in reviewing and accessing the scholarship application data and biostatistician A/Prof Steven Bowe for statistical advice.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 2. Australian Government Department of Education. Research Training Program. Research Training Program https://www.education.gov.au/research-training-program (2019).

- 4. QS World University Rankings Methodology https://www.topuniversities.com/qs-world-university-rankings/methodology (2018).

- 5. World University Rankings 2019: methodology https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/world-university-rankings-2019-methodology (2018).

- 6. Academic Ranking of World Universities Methodology http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU-Methodology-2018.html (2018).

- PubMed/NCBI

- 16. Haidar, H. PhD admission requirements. What is a PhD? https://www.topuniversities.com/blog/what-phd .

- 21. Rowe, K. The importance of teacher quality as a key determinant of students’ experiences and outcomes of schooling. in 15–23 (2003).

- 30. The University of Melbourne. How are graduate research scholarships awarded? https://education.unimelb.edu.au/study/scholarships/scholarship-support .

The Strathclyde inventory as a measure of outcome in person-centred therapy

Downloadable content.

- Stephen, Susan.

- Strathclyde Thesis Copyright

- University of Strathclyde

- Doctoral (Postgraduate)

- Doctor of Philosophy (PhD)

- Counselling Unit.

- School of Psychological Sciences and Health.

- Person-centred therapy, like other humanistic therapies, proposes a potentiality model in which psychological growth, not simply the reduction of symptoms, is the anticipated outcome of therapy. Although substantial evidence of the effectiveness of person-centred therapy using medical model concepts exists, there is a need to develop measures that test outcome in therapy according to the person-centred theory of change. The Strathclyde Inventory (SI) is a brief self-report instrument designed to measure congruent functioning (described elsewhere as Rogers' fully functioning person, or congruence) for use as an outcome measure in therapy. The main purpose of this innovative three-part mixed method study was to investigate the validity of the SI as an outcome measure from multiple perspectives using data collected from a large UK-based clinical population. The first study evaluated the internal structure and reliability/precision of the instrument using the Rasch model. The second study investigated patterns of change in SI scores over the course of therapy seeking evidence of sensitivity to change, as well as convergent and construct validity. The third study tested the validity of change in SI scores as a measure of congruent functioning via a meta-synthesis of a series of eight systematic case studies examining client improvement and deterioration in therapy identified by pre-post change in SI scores. The results supported the validity of the SI as an internally consistent and precise unidimensional instrument that is able to identify meaningful change in congruent functioning within a UK-based clinical population. A brief 12-item version of the instrument was produced. An evidence-based, theoretically coherent, developmental pathway for congruent functioning was proposed, identifying self-acceptance as a pivot point. Overall, the results of this three-part study established that change in participants' scores during therapy demonstrated a high degree of variation and proposed an explanation for different post-therapy outcomes in congruent functioning.

- Dixon, Diane

- Elliott, Robert, 1950-

- Doctoral thesis

- 10.48730/0bxy-dv30

- 9912876793402996

Student Learning Outcomes: Ph.D.

Examples of student learning outcomes for phd programs.

Source: Adapted from student learning outcomes in a range of graduate programs at Brigham Young University .

All Disciplines

All graduates will be able to:

- Critically apply theories, methodologies, and knowledge to address fundamental questions in their primary area of study. (Research, Critical Thinking, Content Knowledge)

- Pursue research of significance in the discipline or an interdisciplinary or creative project. Students plan and conduct this research or implement this project under the guidance of an advisor while developing the intellectual independence that typifies true scholarship. (Research, Critical and Creative Thinking)

- Demonstrate skills in oral and written communication sufficient to publish and present work in their field and to prepare grant proposals. (Communication)

- Follow the principles of ethics in their field and in academia. (Ethics)

- Demonstrate, through service, the value of their discipline to the academy and community at large. (Service, Content Knowledge)

- Demonstrate a mastery of skills and knowledge at a level required for college and university undergraduate teaching in their discipline and assessment of student learning. (Content Knowledge, Teaching)

- Interact productively with people from diverse backgrounds as both leaders/mentors and team members with integrity and professionalism. (Communication, Leadership)

Discipline or Degree-specific Skills, Knowledge, and Values

Graduates in [discipline or degree] will be able to:

- as defined by the program

Last updated 8/22/2013

- Open access

- Published: 26 August 2020

Understanding the mental health of doctoral researchers: a mixed methods systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-synthesis

- Cassie M. Hazell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5868-9902 1 ,

- Laura Chapman 2 ,

- Sophie F. Valeix 3 ,

- Paul Roberts 4 ,

- Jeremy E. Niven 5 &

- Clio Berry 6

Systematic Reviews volume 9 , Article number: 197 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

57 Citations

74 Altmetric

Metrics details

Data from studies with undergraduate and postgraduate taught students suggest that they are at an increased risk of having mental health problems, compared to the general population. By contrast, the literature on doctoral researchers (DRs) is far more disparate and unclear. There is a need to bring together current findings and identify what questions still need to be answered.

We conducted a mixed methods systematic review to summarise the research on doctoral researchers’ (DRs) mental health. Our search revealed 52 articles that were included in this review.

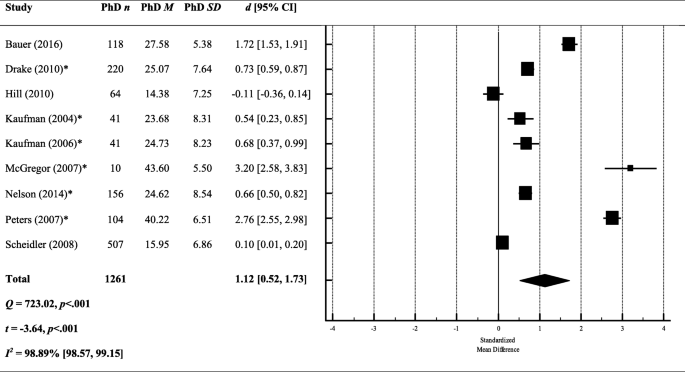

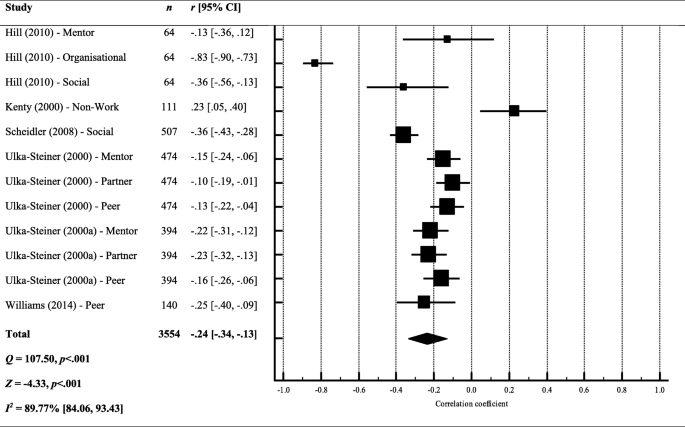

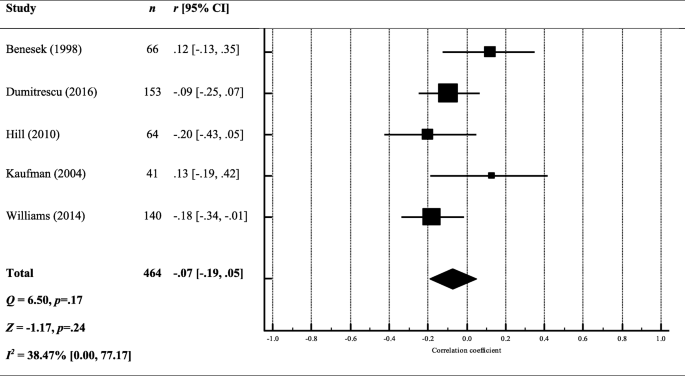

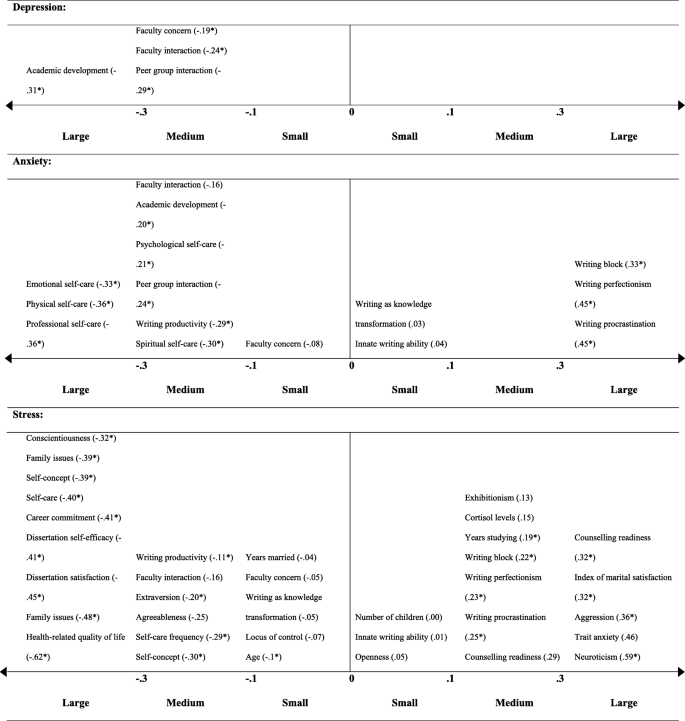

The results of our meta-analysis found that DRs reported significantly higher stress levels compared with population norm data. Using meta-analyses and meta-synthesis techniques, we found the risk factors with the strongest evidence base were isolation and identifying as female. Social support, viewing the PhD as a process, a positive student-supervisor relationship and engaging in self-care were the most well-established protective factors.

Conclusions

We have identified a critical need for researchers to better coordinate data collection to aid future reviews and allow for clinically meaningful conclusions to be drawn.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO registration CRD42018092867

Peer Review reports

Student mental health has become a regular feature across media outlets in the United Kingdom (UK), with frequent warnings in the media that the sector is facing a ‘mental health crisis’ [ 1 ]. These claims are largely based on the work of regulatory authorities and ‘grey’ literature. Such sources corroborate an increase in the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst students. In 2013, 1 in 5 students reported having a mental health problem [ 2 ]. Only 3 years later, however, this figure increased to 1 in 4 [ 3 ]. In real terms, this equates to 21,435 students disclosing mental health problems in 2013 rising to 49,265 in 2017 [ 4 ]. Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) demonstrates a 210% increase in the number of students terminating their studies reportedly due to poor mental health [ 5 ], while the number of students dying by suicide has consistently increased in the past decade [ 6 ].

This issue is not isolated to the UK. In the United States (US), the prevalence of student mental health problems and use of counselling services has steadily risen over the past 6 years [ 7 ]. A large international survey of more than 14,000 students across 8 countries (Australia, Belgium, Germany, Mexico, Northern Ireland, South Africa, Spain and the United States) found that 35% of students met the diagnostic criteria for at least one common mental health condition, with highest rates found in Australia and Germany [ 8 ].

The above figures all pertain to undergraduate students. Finding equivalent information for postgraduate students is more difficult, and where available tends to combine data for postgraduate taught students and doctoral researchers (DRs; also known as PhD students or postgraduate researchers) (e.g. [ 4 ]). The latest trend analysis based on data from 36 countries suggests that approximately 2.3% of people will enrol in a PhD programme during their lifetime [ 9 ]. The countries with the highest number of DRs are the US, Germany and the UK [ 10 ]. At present, there are more than 281,360 DRs currently registered across these three countries alone [ 11 , 12 ], making them a significant part of the university population. The aim of this systematic review is to bring attention specifically to the mental health of DRs by summarising the available evidence on this issue.

Using a mixed methods approach, including meta-analysis and meta-synthesis, this review seeks to answer three research questions: (1) What is the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst DRs? (2) What are the risk factors associated with poor mental health in DRs? And (3) what are the protective factors associated with good mental health in DRs?

Literature search

We conducted a search of the titles and abstracts of all article types within the following databases: AMED, BNI, CINAHL, Embase, HBE, HMIC, Medline, PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. The same search terms were used within all of the databases, and the search was completed on the 13th April 2018. Our search terms were selected to capture the variable terms used to describe DRs, as well as the terms used to describe mental health, mental health problems and related constructs. We also reviewed the reference lists of all the papers included in this review. Full details of the search strategy are provided in the supplementary material .

Inclusion criteria

Articles meeting the following criteria were considered eligible for inclusion: (1) the full text was available in English; (2) the article presented empirical data; (3) all study participants, or a clearly delineated sub-set, were studying at the doctoral level for a research degree (DRs or equivalent); and (4) the data collected related to mental health constructs. The last of these criteria was operationalised (a) for quantitative studies as having at least one mental health-related outcome measure, and (b) for qualitative studies as having a discussion guide that included questions related to mental health. We included university-published theses and dissertations as these are subjected to a minimum level of peer-review by examiners.

Exclusion criteria

In order to reduce heterogeneity and focus the review on doctoral research as opposed to practice-based training, we excluded articles where participants were studying at the doctoral level, but their training did not focus on research (e.g. PsyD doctorate in Clinical Psychology).

Screening articles

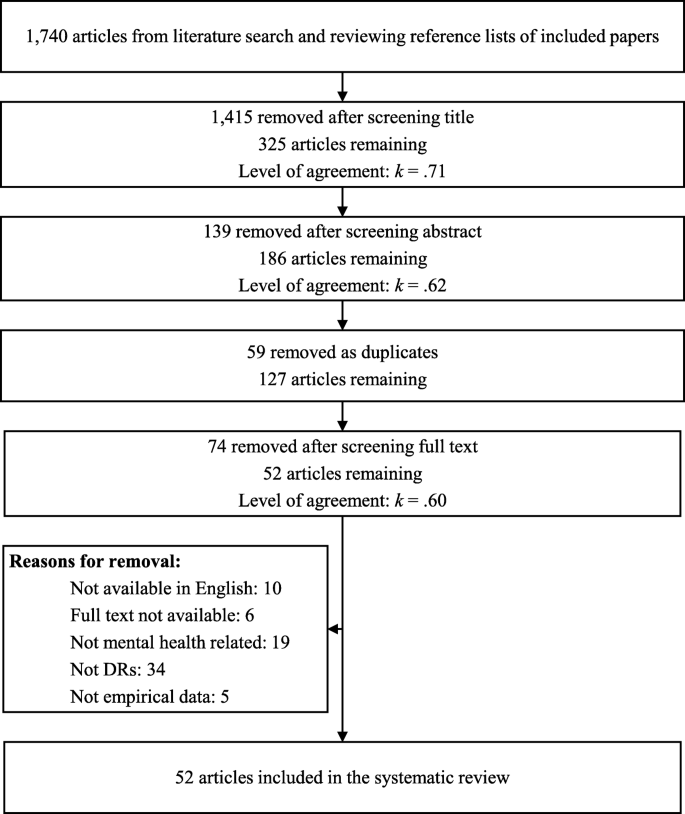

Papers were screened by one of the present authors at the level of title, then abstract, and finally at full text (Fig. 1 ). Duplicates were removed after screening at abstract. At each level of screening, a random 20% sub-set of articles were double screened by another author, and levels of agreement were calculated (Cohen’s kappa [ 13 ]). Where disagreements occurred between authors, a third author was consulted to decide whether the paper should or should not be included. All kappa values evidence at least moderate agreement between authors [ 14 ]—see Fig. 1 for exact kappa values.

PRISMA diagram of literature review process

Data extraction

This review reports on both quantitative and qualitative findings, and separate extraction methods were used for each. Data extraction was performed by authors CH, CB, SV and LC.

Quantitative data extraction

The articles in this review used varying methods and measures. To accommodate this heterogeneity, multiple approaches were used to extract quantitative data. Where available, we extracted (a) descriptive statistics, (b) correlations and (c) a list of key findings. For all mental health outcome measures, we extracted the means and standard deviations for the DR participants, and where available for the control group (descriptive statistics). For studies utilising a within-subjects study design, we extracted data where a mental health outcome measure was correlated with another construct (correlations). Finally, to ensure that we did not lose important findings that did not use descriptive statistics or correlations, we extracted the key findings from the results sections of each paper (list of key findings). Key findings were identified as any type of statistical analysis that included at least one mental health outcome.

Qualitative data extraction

In line with the meta-ethnographic method [ 15 ] and our interest in the empirical data as well as the authors’ interpretations thereof, i.e. the findings of each article [ 16 ], the data extracted from the articles comprised both results/findings and discussion/conclusion sections. For articles reporting qualitative findings, we extracted the results and discussion sections from articles verbatim. Where articles used mixed methods, only the qualitative section of the results was extracted. Methodological and setting details from each article were also extracted and provided (see Appendix A) in order to contextualise the studies.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis, descriptive statistics.

We present frequencies and percentages of the constructs measured, the tools used and whether basic descriptive statistics ( M and SD ) were reported. The full data file is available from the first author upon request.

Effect sizes