SEARCH NYCourts.gov

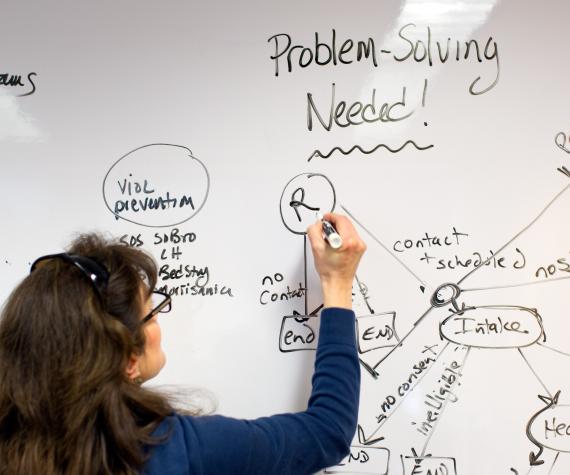

PROBLEM-SOLVING COURTS

The New York State Unified Court System serves the needs of approximately 19,750,000 people, the fourth-largest state population in the nation. Our 1,200 state judges, 2,400 town and village judges and 15,500 non-judicial employees work in over 300 state courts and 1,300 town and village courts spread throughout 62 counties in 13 judicial districts and hear 3,500,000 filings.

To meet the challenges of such a large system, more than two decades ago, the New York State Unified Court System began to establish problem-solving courts. These courts help judges and court staff to better respond to the needs of litigants and the community. Problem-solving courts look to the underlying issues that bring people into the court system, and employ innovative approaches to address those issues. Through intensive judicial monitoring, coordination with outside services, treatment where appropriate, the removal of barriers between courts and increased communication with stakeholders, these courts are able to change the way our system manages cases and responds to individuals, families and communities.

Problem-solving courts take different forms depending on the problems they are designed to address. Drug and mental health courts focus on treatment and rehabilitation. Community courts combine treatment, community responsibility, accountability, and support to both litigants and victims. Sex offense courts employ judicial monitoring and the use of mandated programs and probation to ensure compliance and facilitate access to services. Human trafficking courts center around victims and many cases are resolved without criminal charges. The Adolescent Diversion parts address the unique needs of adolescents in the criminal justice system.

The Unified Court System is committed to the administration of justice in the problem-solving courts, while enhancing public safety.

Chief of Policy and Planning

Contact Info

For further information on Problem-Solving Courts or if you would like to schedule a court visit, please contact the Division of Policy and Planning at [email protected]

Information

Justice Dashboard

- Publications

Explore Data of Countries

Find out how people in different countries around the world experience justice. What are the most serious problems people face? How are problems being resolved? Find out the answers to these and more.

- Burkina Faso

- General population

- IDPs and host communities

- The Netherlands

Solving & Preventing

Guidelines for Justice Problems

Justice Services

Innovation is needed in the justice sector. What services are solving justice problems of people? Find out more about data on justice innovations.

The Gamechangers

The 7 most promising categories of justice innovations, that have the potential to increase access to justice for millions of people around the world.

Justice Innovation Labs

Explore solutions developed using design thinking methods for the justice needs of people in the Netherlands, Nigeria, Uganda and more.

Creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework where innovations and new justice services develop

Rules of procedure, public-private partnerships, creative sourcing of justice services, and new sources of revenue and investments can help in creating an enabling regulatory and financial framework.

Forming a committed coalition of leaders

A committed group of leaders can drive change and innovation in justice systems and support the creation of an enabling environment.

Find out how specific justice problems impact people, how their justice journeys look like, and more.

- Employment Justice

- Family Justice

- Land Justice

- Neighbour Justice

- Crime Justice

- Problem-Solving Courts in the US

Trend Report 2021 – Delivering Justice / Case Study: Problem-Solving Courts in the US

Author: Isabella Banks , Justice Sector Advisor

Introduction

Problem-solving courts are specialised courts that aim to treat the problems that underlie and contribute to certain kinds of crime (Wright, no date). “Generally, a problem-solving court involves a close collaboration between a judge and a community service team to develop a case plan and closely monitor a participant’s compliance, imposing proper sanctions when necessary” (Ibid). In the past three decades, problem-solving courts have become a fixture in the American criminal justice landscape, with over 3,000 established nationwide. All 50 states have appointed a statewide drug court coordinator, and at least 13 have introduced the broader position of statewide problem-solving court coordinator (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010; J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

What does it mean for a court to be problem-solving?

Although a number of different types of problem-solving courts exist across the US, they are generally organised around three common principles: problem-solving, collaboration, and accountability (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. iii.).

Problem-solving courts are focused on solving the underlying problems of those who perpetrate or are affected by crime. This includes reducing recidivism as well as rehabilitating participants (with the exception of domestic violence courts, as elaborated below), victims and the broader community (Ibid. p. iii.).

Problem-solving courts are also characterised by interdisciplinary collaboration among stakeholders in and outside of the criminal justice system. Dedicated staff who have been assigned to the problem-solving court work together to develop court policies and resolve individual cases in a relatively non-adversarial way. Ongoing collaboration between court staff and public agencies, service providers and clinical experts is also essential for providing appropriate treatment to problem-solving court participants (Ibid. p. 38). Because problem-solving courts aim to address the impact of crime on the community and increase public trust in justice, they also have frequent contact with community members and organisations and regularly solicit local input on their work (Ibid. p. 39).

Problem-solving courts aim to hold individuals with justice system involvement, service providers and themselves accountable to the broader community. For individuals with justice system involvement, this means holding them accountable for their criminal behaviour by promoting and monitoring their compliance with court mandates. In order to comply, problem-solving court participants must understand what is expected of them, regularly appear for status hearings, and have clear (extrinsic and intrinsic) incentives to complete their mandates.

For service providers, this means providing services based on a coherent, specified and effective model, and accurately and regularly informing the court about participants’ progress. Problem-solving courts are also responsible for assessing the quality of service delivery and making sure models are adhered to (Ibid. p. 43-44).

Lastly and perhaps most fundamentally, problem-solving courts must hold themselves to “the same high standards expected of participants and stakeholders” (Ibid. p. 44-45). This means monitoring implementation and outcomes of their services using up-to-date data.

What does problem-solving justice look like in practice?

Problem-solving justice comes in different forms. The original, best known, and most widespread problem-solving court model is the drug court. The first drug was created in 1989, after a judge in Miami Dade county became frustrated seeing the same drug cases cycling through her court and began experimenting with putting defendants into treatment (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020). This approach (elaborated in the sections that follow) gradually gained traction, and there are now over 3,000 drug courts across the US (Strong and Kyckelhahn 2016).

This proliferation of drug courts helped stimulate the emergence of three other well-known problem-solving court models: mental health, domestic violence and community courts (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. iii.). Mental health courts are similar to drug courts in that they focus on rehabilitation, but different in that they aim for the improved social functioning and stability of their participants rather than complete abstinence (Ibid. p. 51). Domestic violence courts are unique in that they do not universally embrace participant treatment and rehabilitation as an important goal. Instead, many – thought not all – are primarily focused on victim support and safety and participant accountability and deterrence (Ibid. p. 52).

Community courts “seek to address crime, public safety, and quality of life problems at the neighbourhood level. Unlike other problem-solving courts…community courts do not specialise in one particular problem. Rather, the goal of community courts is to address the multiple problems and needs that contribute to social disorganisation in a designated geographical area. For this reason, community courts vary widely in response to varying local needs, conditions, and priorities” (Lee et al. 2013). There are now over 70 community courts in operation around the world (Lee et al. 2013, p.1). Some are based in traditional courthouses, while others work out of storefronts, libraries or former schools. Though they typically focus on criminal offences, some community courts extend their jurisdiction to non-criminal matters to meet specific needs of the communities they serve as well (Ibid. p. 1.). Regardless of location and jurisdiction, all community courts take a proactive approach to community safety and experiment with different ways of providing appropriate services and sanctions (Wright n.d.).

Other less common problem-solving models include veterans courts, homeless courts, reentry courts, trafficking courts, fathering courts, and truancy courts (Ibid).

The principles and practices of problem-solving justice can also be applied within non-specialised courts that already exist. In a 2000 resolution that was later reaffirmed in 2004, the Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrators advocated for, “Encourag[ing], where appropriate, the broad integration over the next decade of the principles and methods of problem-solving courts into the administration of justice to improve court processes and outcomes while preserving the rule of law” (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. 3). Key features of a problem-solving approach to justice – which will be elaborated in the sections that follow – include: individualised screening and problem assessment; individualised treatment and service mandate; direct engagement of the participant; a focus on outcomes; and system change (Ibid. p. iv).

Problems and impacts

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts measured and mapped the following as a first step towards people-centred justice.

- The most prevalent justice problems within the population served

- The justice problems with greatest impact on the population served

- The justice problems that are most difficult to resolve and therefore tend to remain ongoing

- The groups most vulnerable to (systemic and daily) injustices within the population served

As their name suggests, problem-solving courts emerged to address the most prevalent, impactful, and difficult to resolve justice problems within the populations they serve. The first drug (and Drinking While Driving or DWI) courts were created as a response to the increase in individuals with substance use disorders in the criminal justice system and their levels of recidivism. Similarly, mental health courts “seek to address the growing number of [individuals with mental health needs] that have entered the criminal justice system” (Wright n.d.). As one interviewee put it, “The biggest mental health provider [in Los Angeles] is the county jail” (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 5, 2020).

Drug and mental health problems are among the most common issues faced by individuals responsible for both minor and more serious crime. These issues are difficult to resolve because judges – who have historically had little understanding of treatment and addiction – are inclined to hand down harsh sentences when defendants relapse or fail to complete their court mandate (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 5, 2020). This trend was particularly acute in the 1980s, when the war on drugs resulted in draconian sentencing laws that reduced judicial discretion (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

In order to understand and meet the needs of their unique populations, problem-solving courts track measures of problem prevalence and severity. As noted in the first section, early and individualised screening and problem assessment is a key feature of problem-solving justice. The purpose of such screenings is to “understand the full nature of the [participant’s] situation and the underlying issues that led to justice involvement.”

For drug courts, relevant measures of problem severity may include: drug of choice; years of drug use; age of first use; criminal history; and treatment history (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. 50). Mental health courts typically assess the nature and severity of their participants’ underlying mental health issues, and may also look at participant stability (in terms of health care, housing, compliance with prescribed medications, and hospitalisations) (Ibid. p. 51).

Domestic violence courts and community courts are somewhat unique in that the primary population they serve include victims and members of the community as well as individuals with justice system involvement. Domestic violence courts focus on assessing the needs of victims of domestic violence in order to connect them with safety planning and other individualised services. Likewise, in addition to identifying the problems that impact individual participants, community courts focus on assessing the problems that impact the underserved (and also often disserved) neighbourhoods where they work. These should be identified through outreach in the relevant community but often include concentrations of lower level crimes – such as vandalism, shoplifting, and prostitution – as well as distrust of traditional justice actors (Ibid. p. 55-56).

Now that technical assistance is broadly available for problem-solving courts across the US, individualised screening and problem assessment has become increasingly data-driven and informed by validated needs assessment tools (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

Over the years, problem-solving courts have also become more adept at identifying groups within the populations they serve that are particularly vulnerable to injustice. The advancement of brain science, for example, has influenced many problem-solving courts to treat participants under 25 differently and give them an opportunity to age out of crime. Young people transitioning out of foster care are particularly vulnerable to justice involvement given their sudden lack of family support. Trafficked individuals, who used to be treated as criminals, are now widely recognised as victims (Ibid). Specialised problem-solving courts, diversion programs, and training initiatives have emerged to understand the unique needs and vulnerabilities of this population (Wright n.d.).

Problem-solving courts have also become more aware of racial inequities in the populations selected to receive treatment (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 16, 2020). Drug court participants in particular are often disproportionately white, with racial breakdowns that do not mirror the racial breakdowns of those arrested. This is largely a result of eligibility requirements tied to federal drug court funding, which has historically restricted individuals with violent criminal histories from participating. Drug courts have also been accused of cherry-picking participants who were most likely to be successful to improve their numbers and receive more funding. Both of these phenomena have had the effect of excluding disproportionate numbers of people of colour from drug treatment (Ibid). In addition to taking steps to mitigate these inequities, drug courts have increasingly come to recognise that cherry-picking low-risk cases reduces their effectiveness overall (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

Defining + Monitoring Outcomes

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts researched and identified the outcomes that people in the target population expect from justice processes.

In 1993, the first community court was set up in the Midtown neighbourhood of New York City (Lee et al. 2013, p.1). Inspired by the Midtown model, the Red Hook Community Justice Center was established in a particularly disadvantaged area of Brooklyn seven years later. Like the Midtown Court, the goal of the Red Hook Community Justice Center was “to replace short-term jail sentences with community restitution assignments and mandated participation in social services” (Taylor 2016).

In the planning stages however, residents of Red Hook were not happy to learn that a new court was being introduced in their community. Though sustained community outreach, Red Hook court staff were able to change these negative perceptions and convince residents they wanted to do something different. They began by asking the community what outcomes were most important to them (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 5, 2020).

This early engagement helped the Red Hook planners realise that tracking outcomes related to people’s presence in the court would not be enough to assess the court’s impact in the community. They would also need to look at outcomes that were meaningful to residents, asking questions like: How can we disrupt crime hot spots? How safe does the community feel? Do residents feel safe walking to the park, or the train? At what times? (Ibid).

Although the Red Hook community court model has since been replicated in different parts of the world, the experiences of two of these international courts illustrate that identifying the outcomes that community members expect from justice processes can sometimes be a challenge.

In 2005, England opened its first community court: the North Liverpool Community Justice Centre (NLCJC). A 2011 evaluation of the NLCJC acknowledged its innovative approach and “potentially transformative effect on criminal justice” but also noted:

How and why the Centre needs to connect with the public it is charged with serving remains one of the most complex and enduring concerns for staff...how consistently and how effectively the ‘community’ was contributing to the workings of the Centre provided a constant source of uncertainty” (Mair and Millings 2011).

After eight years of operation, the NLCJC was closed in 2013. Observers have since noted that a lack of grassroots community engagement in the planning and operation of the NLCJC was among the primary reasons that it ultimately failed to take hold (Murray and Blagg 2018; J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

One year after the NLCJC opened in England, the Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC) was piloted in the Collingwood neighbourhood of Melbourne, Australia. At the time, Collingwood had the highest crime rate in Melbourne, high rates of inequality, and a high concentration of services. This combination made it an ideal location for Australia’s first community court.

Modelled on the Red Hook Community Justice Centre in Brooklyn and spearheaded by the State Attorney General at the time, Rob Hulls, the NJC pilot was focused on improving the community’s relationship with the justice system through local, therapeutic and procedural justice. Like Red Hook, it was designed based on evidence and an analysis of gaps in existing justice services. Despite shifting political winds – including “tough-on-crime” rhetoric on the one hand and complaints of more favourable “postcode justice” available only for the NJC’s participants on the other – the NJC managed to secure ongoing state government support (J. Jordens, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

Unlike the NLCJC, the NJC remains in operation today. The procedurally just design of the NJC building and approach of its magistrate, David Fanning, have earned the court significant credibility and legitimacy in the Collingwood community (Halsey and Vel-Palumbo 2018; J. Jordens, personal communication, October 19, 2020). Community and client engagement have continued to be a key feature of the NJC’s work, helping to reduce recidivism and increase compliance with community-based court orders (Halsey and Vel-Palumbo 2018) .

In spite of its success, some observers note that the NJC’s outreach efforts have not gone as far as they could have. Early consultations with a group of community stakeholders regarding the design and governance of the NJC were discontinued in the Centre’s later years. Although the reason for this is unclear and may well have been legitimate, the result was that key representatives of the community lost direct and regular access to NJC leadership over time (J. Jordens, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

These examples illustrate that even under the umbrella of a one-stop-shop community court, identifying expected justice outcomes in the community as a first step towards problem-solving justice – and continuing to do so even after the court is well-established – is not a given. The extent to which this is achieved depends on the approach of the particular court and its efforts to create a reciprocal and collaborative relationship with the surrounding community.

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts determined whether existing justice processes deliver these outcomes and allow people in the target population to move on?

Problem-solving courts generally – and community courts and drug courts in particular – are created with the explicit intention to address gaps in existing justice processes.

Community courts are typically established in communities that have been historically underserved and disproportionately incarcerated to provide a more holistic response to crime and increase trust in the justice system.

In the early days of the Red Hook Community Justice Center, the community’s deep distrust of law enforcement emerged as a key challenge for the Center’s work. Red Hook staff approached this challenge by inviting police officers into the court and showing them the data they had collected on the justice outcomes that residents were experiencing. They helped the officers understand that by not addressing the root causes of crime in the Red Hook community, they were delaying crime rather than stopping it (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 5, 2020).

Over time, the court’s relationship with law enforcement has improved. In 2016, the Justice Center launched its “Bridging the Gap” initiative, which creates a safe space for young people and police officers to get to know each other and discuss difficult topics that offer the chance to explore the other’s perspective (Red Hook Justice News 2016; Sara Matusek 2017).

Similarly, the proliferation of drug courts across the country was a response to high rates of recidivism among individuals with substance use disorders, which persisted in spite of tough-on-crime sentencing practices. During the so-called “war on drugs” in the mid-1980s, judges across the country gradually began to realise that handing down increasingly long sentences to people with substance use disorders was not working.

One such person was the late Honourable Peggy Hora, a California Superior Court judge responsible for criminal arraignments. Like other judges repeatedly confronted with defendants grappling with substance use disorders in the 1980s and 90s, Judge Hora initially felt that incarceration was the only tool available to her. Not much research had been done on incarceration at the time, so its detrimental effects were not yet widely known (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

Determined to understand why the defendants that came before her seemed to be willing to risk everything to access drugs – even their freedom and the right to see their children – Judge Hora took a class on chemical dependency. This experience brought her to the realisation that “everything they were doing was wrong.” She quickly built relationships with people at the National Institute on Drug Abuse and began engaging with drug treatment research at a national level (Ibid).

Judge Hora eventually went on to establish and preside over the nation’s second drug court in Alameda County, California. After learning more about procedural justice and seeing evidence that early drug courts worked and saved money in the long run, she helped promote the model across the country and around the world (Ibid).

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts created a system for monitoring whether new, people-centered justice processes deliver these outcomes and allow people in the target population to move on?

Outcomes monitoring is an essential component of problem-solving justice. As Rachel Porter, Michael Rempel, and Adam Manksy of the Center for Court Innovation set out in their 2010 report on universal performance indicators for problem-solving courts:

It is perhaps their focus on the outcomes generated after a case has been disposed that most distinguishes problem-solving courts from conventional courts. Like all courts, problem-solving courts seek to uphold the due process rights of litigants and to operate efficiently, but their outcome orientation demands that they seek to address the underlying issues that precipitate justice involvement (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. 1.).

Measuring and monitoring people-centred outcomes was also key to problem-solving courts’ early success. Because the problem-solving approach was so different from the status quo, showing evidence that it worked was necessary for building political and financial support. This meant clearly articulating the goals of problem-solving courts and finding ways to measure progress towards them (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 14, 2020).

In their report, What Makes a Court Problem-Solving? Porter, Rempel, and Mansky identify universal indicators for each of the three organising principles of problem-solving courts. They include: (under problem-solving) individualised justice and substantive education for court staff; (under collaboration) links with community-based agencies and court presence in community; and (under accountability) compliance reviews, early coordination of information, and court data systems (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. 57). Many of these problem-solving principles and practices can be (and are) applied and monitored in traditional courts.

To ensure delivery of individualised justice for example, any court staff can engage the individuals appearing before it by making eye contact, addressing them clearly and directly, and asking if they have any questions about the charges or their mandate (Ibid). This kind of engagement can “radically change the experience of litigants, victims, and families” and “improve the chance of compliance and litigant perceptions of court fairness” (Ibid). Similarly, any court can prioritise and track its use of alternative sanctions – such as community service or drug treatment – and its efforts to link individuals to existing services in the community (Ibid).

The extent to which a particular (problem-solving or traditional) court monitors progress towards these people-centred outcomes depends on its ability to track compliance and behaviour change among participants. This can be achieved through regular compliance reviews, which provide “an ongoing opportunity for the court to communicate with [participants] and respond to their concerns and circumstances” (Ibid. p. 60-61). Investing in electronic data systems that track and coordinate information also makes it easier for a court to monitor its overall impact on case outcomes and improve the quality of its mandates (Ibid).

Successful outcomes monitoring also depends crucially on a court’s ability to develop strong relationships with researchers. Without this, early problem-solving courts like the Red Hook Community Justice Center would not have been able to, for example, quantify the impact of a 7-day jail stay in terms of budget, jail population, and bookings per month. Strong research partnerships also made it possible to compare successful and unsuccessful court participants, which was necessary to assess and improve the quality of the court’s services (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 14, 2020).

Outcomes monitoring at the Red Hook Community Justice Center was not without its challenges, however. Because most people who come before the court are charged with less serious crimes, their treatment mandates are relatively short. The short amount of time the Red Hook staff and service providers have to work with these participants means that outcomes related to individual progress are not likely to show a full picture of the court’s impact. The Red Hook Community Justice Center addressed this by also measuring outcomes related to the court’s impact on the community. What was the effect on social cohesion and stability when someone’s brother, father, or son was allowed to remain in the community instead of being incarcerated? (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 5, 2020).

Another challenge faced by community courts broadly is that traditional outcomes monitoring systems are not well-equipped to acknowledge the reality that everything is connected. Where does one draw the line between service providers and justice providers? If a restorative justice process facilitated under the supervision of the court fails to reconcile the parties in conflict but has a positive impact on the lives of the support people who participate, should it be considered a success or failure?

A former Red Hook staff member involved in the court’s peacemaking initiative shared a story of a young, devout woman with a new boyfriend who mistreated her and who her children strongly disliked. When she tried to throw him out, the boyfriend would use her Christian values against her and convince her to let him stay. Eventually, he punched someone and was arrested on assault charges. His case was referred to a restorative justice circle for resolution. In the circle, the boyfriend was very aggressive and as a result, his case was sent back to court. The woman and her children asked if they could continue meeting in circle without him because they found it helpful (Ibid).

After a series of circle sessions together, the woman came to realise that her abusive boyfriend was using drugs and found the courage to kick him out. In his absence, the woman and her children were able to reconcile and reunite. The woman returned to school and her oldest son found a job. The criminal case that started the process was ultimately unresolved, but from a more holistic and common sense perspective the impact of the circles on the family was positive (Ibid). How should success be measured in this case? This is a challenge that community courts attempting to measure and monitor people-centred justice regularly face.

Evidence-Based Solutions

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts introduced interventions that are evidence-based and consistently deliver the justice outcomes that people in the target population look for.

Problem-solving courts have introduced a number of interventions that have proven to deliver people-centred outcomes for the communities they serve. Although different interventions work for different populations, direct engagement with participants and the delivery of individualised treatments are two key elements of the problem-solving orientation that all problem-solving courts share (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. 29-30).

As described in the previous section, direct engagement means that the judge speaks to participants directly and becomes actively engaged in producing positive change in their lives (Ibid. p. 30-31). This effort to ensure that participants feel heard, respected and experience the process as fair is supported by research on procedural justice.

Individualised treatment means that the interventions delivered are tailored to the specific problems of each participant. This requires that the court offer “a continuum of treatment modalities and services to respond to the variety and degrees of need that participants present.” This service plan must be revisited by the court on a regular basis and adjusted depending on the participant’s reported progress (Ibid. p. 29-30).

Despite this shared approach to justice delivery, different problem-solving courts have identified different types of treatments and ways of monitoring whether they work that are unique to the populations they serve.

Community courts like the Red Hook Community Justice Center, for example, generally work with the residents in their neighbourhood to find out what is important to them rather than imposing a predetermined set of solutions.

The Neighbourhood Justice Centre in Melbourne did this through a unique problem-solving process that took place outside of the courtroom and which participants could opt into voluntarily. In a confidential, facilitated discussion based on restorative and therapeutic justice principles, participants were given an opportunity to share their perspective on the problems they were facing and empowered to become collaborators in their own rehabilitation. Important takeaways from this process would be reported back to the court’s magistrate so he could help them move forward – for example by changing their methadone (1) dose or changing the number of treatments they received per week. The collaborative nature of the sessions helped ensure that the treatment plans mandated by the court were realistic for participants. Though the content of these sessions was unpredictable and varied, the co-design process remained constant (J. Jordens, personal communication, October 19, 2020; Halsey and Vel-Palumbo 2018).

With that said, certain interventions have proven to consistently improve outcomes for communities, victims, and individuals with justice system involvement when applied to low-level cases. These include: using (validated) screening and assessment tools (2); monitoring and enforcing court orders (3); using rewards and sanctions; promoting information technology (4); enhancing procedural justice (5); expanding sentencing options (to include community service and shorter interventions that incorporate individualised treatment); and engaging the community (6).

In 2009, the National Institute of Justice funded a comprehensive independent evaluation of the Red Hook Community Justice Center to assess whether it was achieving its goals to reduce crime and improve quality of life in the Red Hook neighbourhood through these interventions (Lee et al. 2013, p. 2.). The evaluation found that:

The Justice Center [had] been implemented largely in accordance with its program theory and project plan. The Justice Center secured the resources and staff needed to support its reliance on alternative sanctions, including an in-house clinic and arrangements for drug and other treatment services to be provided by local treatment providers...The Justice Center’s multi-jurisdictional nature, as well as many of its youth and community programs, evolved in direct response to concerns articulated in focus groups during the planning process, reflecting a stated intention to learn of and implement community priorities (Ibid. p. 4).

Using a variety of qualitative and quantitative research methods, the evaluation also concluded that Red Hook had successfully: changed sentencing practices in a way that minimised incarceration and motivated compliance; provided flexible and individualised drug treatment; sustainably reduced rates of misdemeanour recidivism among young people and adults; and reduced arrests in the community.

In spite of the robust evidence supporting their approach, many community courts experience resistance to their efforts to help participants address underlying issues of substance use and mental disorders through treatment. As Brett Taylor, a Senior Advisor for Problem-Solving Justice and former defence attorney at the Red Hook explains:

Some critics of community courts say that [this] is not the job of courts and should be handled by other entities. In a perfect world, I would agree. However, in the reality of the world today, people with social service needs continue to end up in the courts. Court systems across the country have realised that if defendants with social service needs are not given treatment options, those defendants will be stuck in the revolving door of justice and continue to clog the court system....Although it may not comport with the vision of success that many defence attorneys had upon entering this work, I can tell you that nothing beats seeing a sober, healthy person approach you on the street and hearing, ‘Thank you for helping me get my life back on track’ (Taylor 2016, p. 25).

In contrast to the broad and community-based approach to treatment taken by community courts, drug courts focus specifically on providing drug treatment. In the words of Judge Peggy Hora, drug treatment is “painful and difficult.” Because of this, drug courts start with external changes as their goal, but ultimately aim for internal change. This means appropriately matching participants with evidence-based treatment and using neutral language that assists, supports, and encourages participants along the way. Because relapse is such a common feature of recovery, drug courts focus on keeping people in appropriate treatment as long as necessary for them to eventually graduate from the program (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

Drug court treatments have become increasingly evidence-based since the 1990s due to a growing movement toward performance measurement in the non-profit sector:

The emergence of drug courts as a reform of courts’ traditional practice of treating drug-addicted offenders in a strictly criminal fashion coincided with renewed interest in performance measurement for public organisations. The argument for measuring the performance of drug courts is compelling because they are a recent reform that must compete with existing priorities of the judicial system for a limited amount of resources. This makes it incumbent upon drug courts to demonstrate that the limited resources provided to them are used efficiently and that this expenditure of resources produces the desired outcomes in participants (Rubio et al. 2008, p. 1).

This movement was further strengthened by the development of a cutting edge performance measurement methodology known as the “balanced scorecard.” Created for the business sector, the balanced scorecard method aims to go beyond traditional measures of success and get a more balanced picture of performance by incorporating multiple perspectives. This method was adapted to create CourTools, a set of ten performance measures designed to evaluate a small set of key functions of trial courts (Ibid. p. 2).

Because “the nature of addiction and the realities of substance use treatment require extended times to disposition for drug court participants,” many of the performance measures developed for conventional trial courts (such as reduced time to disposition) are not directly applicable to drug courts. However, the increased application of performance measurement to courts and the creation of CourTools in particular helped make way for the development of the first set of nationally recommended performance measures for Adult Drug Courts in 2004 (Ibid. p. 4).

Developed by a leading group of scholars and researchers brought together by the National Drug Court Institute (NDCI) and published for the first time in 2006, these included four key measures of drug court performance: retention; sobriety, in-program recidivism; and units of service (Ibid. p. 5).

Retention refers to the amount of time drug court participants remain in treatment. “Longer retention not only indicates success in treatment but also predicts future success in the form of lower post treatment drug use and re-offending” (Ibid. p. 5). Sobriety – both during and after treatment – is another important goal of drug courts. “As the participant proceeds through the program, a trend of decreasing frequency of failed [drug] tests should occur. Research has shown that increasing amounts of time between relapses is associated with continued reductions in [drug] use” (Rubio et al. 2008, p. 5). In-program recidivism is the rate at which drug court participants are re-arrested during the course of their participation. This is expected to be lowered through a combination of “judicial supervision, treatment, and rewards and sanctions” unique to drug courts (Ibid. p.5; US Government and Accountability Office, 2005). Finally, units of service refers to the dosages in which drug court treatment services – including, but not limited to substance use treatment – are delivered. These are usually measured in terms of days or sessions of service provided (Rubio et al. 2008, p. 5).

Since their development, these four measures of drug court performance have been actively promoted by leading technical assistance providers like the Center for Court Innovation (CCI) and the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) (Ibid. p. 6). They have since been adopted and adapted by a number of states across the US. The NCSC facilitates this process, but decisions about what specifically to measure are made by the advisory committee convened by the state-level agency responsible for drug courts (Ibid). Additional performance measures used by some states relate to, for example: accountability, social functioning, processing, interaction with other agencies, compliance with quality standards, and juvenile drug court measures, family drug court measures, and domestic violence drug court measures (Ibid. p. 10).

In 2007, the NCSC surveyed statewide drug court coordinators from across the country about their use of state-level performance measurement systems (SPMS). Out of 45 states that completed the surveys, 58% were using a SPMS in their drug courts. Most of these were adult drug courts (Ibid. p. 14). Although the frequency with which these states reported performance measurement data varied from quarterly to annually, the majority did provide data to a central agency (Ibid. p. 15).

The development and widespread use of SPMS have helped drug courts deliver treatments that are increasingly evidence-based in the sense of consistently delivering the outcomes that their participants need. However, the NCSC survey found that the state-level performance measures used were not entirely balanced in that they typically focused more on the effectiveness of drug courts than their efficiency, productivity, or procedural satisfaction (Ibid. p. 20). The NCSC therefore recommended that a more balanced, national and uniform set of drug court performance measures be developed to measure performance more holistically and facilitate comparisons of performance across states (Ibid. p. 18).

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts used outcome-based monitoring (discussed in the previous section) to continuously improve these interventions and replace interventions that have proven ineffective?

Because of their problem-solving orientation and focus on outcomes, problem-solving courts are by their nature adaptive and capable of developing new treatment modalities to meet different kinds of needs. As Brett Taylor, Senior Advisor for Problem-Solving at the Center for Court Innovation put it, “the problem-solving court environment creates a space in which there is more room for creativity. If you were to redesign the justice system now, there wouldn’t be only courts you could go to, there would be different justice mechanisms and modalities available to treat different levels of issues. Perhaps that is why new modalities develop within problem-solving courts” (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

A clear example of this creative and outcomes-based approach to improvement was the way the problem-solving dialogue process developed at the Neighbourhood Justice Center (NJC) was adapted over time to meet changing demands in the community. As Jay Jordens, a Neighbourhood Justice Office at the NJC who introduced the process explains: “different problems would arise that would demand a re-design of the court’s approach” (J. Jordens, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

For example, the NJC began to notice that people responsible for family violence were participating in problem-solving dialogues without sharing this part of their history. In response, the NJC developed a tailored problem-solving process for people who were respondents to a family violence order in which this part of their past would be addressed from the start. The NJC also began facilitating support meetings for victims of family violence, including for example parents who were being mistreated by their children. The process was designed to solicit feedback about the new approach after victims had tried it. Eventually, it earned the support of the police in the community because it consistently delivered outcomes for a unique population (Ibid).

A second adaptation of the problem-solving process at the NJC was made when court staff noticed that many young people were opting out. Many of the court-involved young people in the Collingwood community were refugees from South Sudan who were experiencing the effects of intergenerational trauma. Realising that the process as it was originally imagined was too interrogative for this population, the NJC began holding circles with the young person, their mother, and one or two support workers. A facilitator would begin by asking humanising questions of everyone in the circle. Although the young person would often pass when it was their turn to speak, participating in the circle gave them an opportunity to listen, relax, and improve their relationships with the adults sitting in the circle with them. These problem-solving circles were designed to prioritise safety concerns and would often result in an agreement among the participants to get external support and/or attend family therapy.

Jay Jordens notes that such adaptations were possible in spite of, not because of, an operational framework of specialisation within the court that made collaboration a choice rather than an expectation among Centre staff. “We aren’t there yet where these processes are intuitive,” he explained, “we still need to actively facilitate them” (Ibid).

Because of their systematic approach to outcomes monitoring and performance measurement, drug courts have made a number of improvements to the treatment they provide as well. First and foremost, they have learned to avoid net widening: “the process of administrative or practical changes that result in a greater number of individuals being controlled by the criminal justice system” (Leone n.d.).

Specifically, drug courts have learned that putting the wrong people in the wrong places results in bad outcomes. An example of this is cherry picking the easiest cases for drug treatment: a common practice among drug courts in the early years of their development that later proved to be harmful. Evidence has shown that drug courts are most effective when they focus on treating high-risk, high-needs participants who are most likely to reoffend (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020). Cherry picking low-risk cases in order to inflate measures of success means putting them in more intensive treatment than they need and failing to appropriately match treatments with risk. Over time, this entraps people in the criminal justice system unnecessarily and reduces drug courts’ potential to meaningfully reduce crime (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

Cherry picking low-risk cases for drug treatment has also resulted in racially biased outcomes. Because of the ways racial bias is embedded in the American criminal justice system, young white defendants have historically been more likely to be assessed as low-risk and eligible for specialised treatment than participants of colour. Participants of colour who were selected for drug court programming also tended to flunk out or leave voluntarily at higher rates than white participants.

In response to these trends, drug courts developed a toolkit on equity and inclusivity to examine the data and understand why this was happening. They introduced HEAT (Habilitation Empowerment Accountability Therapy), a new drug treatment modality geared towards young black men which was recently evaluated with very positive results. They have also worked harder generally to ensure that treatments are culturally appropriate for the different populations they serve.

Drug courts have also become more sophisticated at treating different kinds of drug addiction. The Matrix Model, for example, was developed to engage a particularly difficult population – stimulant (methamphetamine and cocaine) users – in treatment. Previously considered “untreatable” by many drug courts, stimulant users treated using the Matrix Model have shown statistically significant reductions in drug and alcohol use, risky sexual behaviors associated with HIV transmission, and improved psychological well-being in a number of studies (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020; National Institute of Drug Abuse 2020).

Drug court judges who once took a “blaming and shaming” approach have shifted towards a more people-centred one, as evidenced by changes in the language used to describe participants. In response to research in the medical sector demonstrating that people who are described as addicts receive lower quality care and fewer prescriptions, drug courts have increasingly replaced the term “addiction” with “substance use disorder” (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

In line with this shift, attitudes towards medically assisted drug treatment have also changed dramatically over the years. Whereas most drug courts previously did not allow the use of methadone in treatment, the field has now clearly adopted medically assisted treatment after finding that it was consistent with improved graduation rates, among other outcomes. Though not universally accepted, it is now considered a best practice supported by decades of research (Ibid).

On a more systematic level, a 2007 analysis of performance measurement data collected by the state of Wyoming provides an example of how drug courts have started to use this data to improve the quality of their treatments and overall impact. Based on results related to the key measures of drug court performance introduced in the previous section – retention, sobriety, in-program recidivism and units of service – the NCSC made a number of programmatic recommendations for drug courts across the state. First, they suggested that drug courts aim to support participants’ education and employment-related needs, as both attainment of a diploma and employment at admission to treatment were associated with increased graduation rates. They also recommended that additional resources be made available for young participants of colour, who were found to have higher rates of positive drug tests and recidivism than young white participants (Rubio et al. 2008, p. 17).

Innovations + Delivery Models

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts scaled their people-centered service delivery model to deliver justice outcomes for a larger population.

Many problem-solving courts across the US continue to start in the way the first problem-solving courts did: with judges deciding to do things differently. With that said, the proliferation of problem-solving courts across the country can be traced to three primary factors: science and research; technical assistance; and changes in legal education.

Research has helped bring problem-solving courts to scale by showing that the problem-solving approach to justice, if properly implemented, can be effective. Research on procedural justice and advancements in understanding of the science of addiction have been particularly important in this respect. Increased awareness of major studies in these areas have helped the field shift towards evidence-based working and helped legal professionals learn from past mistakes. More and more judges realise that relapse is part of recovery, and that mandated treatment within a drug court structure delivers positive outcomes for participants (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

Once a number of problem-solving courts had been established around the country, technical assistance providers emerged to help them take a data-driven approach. This means working with communities to look at the numbers and identify the biggest crime problems they are struggling with and introducing a problem-solving court that is responsive to those issues. It also means using screening and needs assessment tools to make informed sentencing decisions and match participants to appropriate treatments. Technical assistance has helped problem-solving courts increase their impact and effectiveness and over time deliver outcomes for larger populations (Ibid).

As problem-solving courts like the Red Hook Community Justice Center have become better known, law students and young legal professionals have become more aware of and enthusiastic about problem-solving justice as an alternative to adversarial ways of working (Ibid). This represents a significant shift from the early days of problem-solving courts, when judges and lawyers alike were reluctant to embrace non-conventional conceptions of their roles as legal professionals. Prosecutors called problem-solving courts “hug-a-thug” programs. Defence attorneys resisted the idea of a court being a cure-all for their clients. Judges insisted that they “weren’t social workers” and shouldn’t be doing this kind of work (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020). Service providers were concerned too: they feared that involving the justice system in treatment would ruin their client relationships.

Over time, judges have come to see that their roles could expand without violating something sacrosanct about being a judge. In 2000, the Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrators adopted a resolution supporting the use of therapeutic justice principles. Since then, experience presiding over a drug court has come to be seen as a positive in judicial elections (Ibid).

Despite early concerns that problem-solving courts were “soft on crime,” prosecutors and defense attorneys have largely come on board as well. Research has demonstrated that when problem-solving courts acknowledge their gaps in knowledge and defer to service providers for clinical expertise, they can be successful in supporting treatment. As a result of advances in research, the emergence of problem-solving technical assistance, and important cultural shifts, drug and mental health courts are now widely recognised as appropriate and welcome additions to the field (Ibid). This acceptance has facilitated their spread nationally and as far as Australia and New Zealand.

Court numbers are not the only relevant measure for evaluating the extent to which problem-solving courts have successfully scaled, however. In addition to horizontal scaling of courts across the country, vertical integration of problem-solving principles and practices within particular jurisdictions is an important indicator of problem-solving courts’ spread and influence (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

As explained in the introduction, the principles and practices of problem-solving justice can be and are increasingly applied by traditional justice actors and in existing, non-specialised courts. Police departments across the country are learning that they can divert defendants to treatment from the get-go, without necessarily waiting for a case to be processed through the courts (Ibid). A prominent example of police-led diversion is LEAD (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion) in Seattle, “a collaborative community safety effort that offers law enforcement a credible alternative to booking people into jail for criminal activity that stems from unmet behavioural needs or poverty” (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion, n.d.). The Seattle LEAD model was externally evaluated and found to deliver a range of positive outcomes for individuals with justice system involvement and the community (LEAD National Support Bureau n.d.-a). The model has been replicated successfully and is now operating in over thirty-nine counties in the US (LEAD National Support Bureau n.d.-b).

Cases that do reach court are also increasingly diverted outside of it. Prosecutors and judges who are not operating within a problem-solving court can nevertheless apply problem-solving principles by linking defendants to services and making use of alternative sentences in lieu of jail time. This “problem-solving orientation” has allowed problem-solving justice to be applied in more instances and settings without necessarily setting up new problem-solving courts. One indication that problem-solving courts have already scaled “horizontally” in the US – and that this “vertical” scaling is the latest trend – is the fact that the US government’s drug courts funding solicitation in 2020 no longer includes a category for the creation of a new drug court (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

Evidence of this trend towards vertical scaling can be found as far away as Australia. As a specific alternative to horizontal replication, the Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC) has developed resources to support judges at the Melbourne Magistrates Court to adopt a problem-solving approach to their work. Over time, this court has become a “laboratory of experimentation” for problem-solving principles and practices as well as other complementary technologies (i.e. therapeutic or procedural justice approaches) that need to be tested before broader roll-out. In a similar vein, New York City’s courts have carried the innovative principles and practices of community courts into centralised courthouses in Brooklyn and the Bronx rather than creating more Red Hooks (Ibid).

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts funded their service delivery model in a sustainable way?

Drug courts have been successful in obtaining large and sustainable streams of federal funding due to the strong research partnerships they developed from the start. Early data collection and evaluation persuaded funders that the problem-solving approach would deliver positive outcomes and save money by reducing incarceration costs. The fact that Florida Attorney General Janet Reno – who set up the nation’s first drug court in 1989 – worked with Assistant Public Defender Hugh Rodham (7) in Miami Dade County also helped make drug courts a success and capture the attention of the federal government early on.

Importantly, federal funding for drug courts was often conditional upon their participation in rigorous evaluations. This demonstrated the effectiveness of the drug court model in a way that may not have been possible had the drug courts had to fund the research themselves, and justified their continued funding (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020). In recent years, states and counties have become a significant source of funding for drug courts as well (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

Although the federal government has also helped fund other types of problem-solving courts, drug courts are by far the most sustainably funded. Only recently has the government made it possible for community courts to apply for direct funding, or indirect funding as subgrantees of the Center for Court Innovation. The long-term funding for many community courts is provided by local municipalities (Ibid). Funding community courts is a unique challenge because in addition to standard line items like project director and case worker salaries, they must find a way to cover less conventional expenses support for community volunteers and circle participants (often in the form of food, which the government is not willing to fund) (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

Direct federal funding for other kinds of problem-solving courts is very limited. What funding has been made available to them has gone primarily towards research and the establishment of state-level coordinators and problem-solving court infrastructure. This has helped to increase awareness of the problem-solving principles and practices at the state level and encouraged their application in different areas (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

Private foundations have supported various aspects of problem-solving justice initiatives in certain parts of the country, but have not yet committed to doing so in a sustained way (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

To what extent have problem-solving courts leveraged the following sustainable financing strategies: public-private partnerships and smart (user) contributions?

Community courts in New York – including the Red Hook Community Justice Center and the Midtown Community Court – have benefitted from public-private partnerships to the extent that their planning and operations have been led by the Center for Court Innovation, a public-private partnership between the New York court system and an NGO. Over the years, these courts have also partnered with local “business improvement districts” to supervise community service mandates and offer employment opportunities to program graduates (Ibid).

Some treatment courts do also charge a nominal participant fee, which can range from $5-$20 per week (Wallace 2019). These user contributions can be used for grant matching, among other things. Charging people for their participation in problem-solving programming is generally not regarded as good practice, however (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

More broadly, problem-solving courts and community courts in particular can be said to be financially sustainable in that they often save taxpayer money (Wallace 2019). Although it takes time to realise the benefits of the upfront costs of creating and running a drug court for example, research has demonstrated that once established, the associated cost savings range from more than $4,000-$12,000 per participant (Office of National Drug Court Policy 2011). The Red Hook Community Justice Center alone was estimated to have saved local taxpayers $15 million per year (primarily) in victimisation costs that were avoided as a result of reduced recidivism (Halsey and de Vel-Palumbo 2018). The cost savings associated with problem-solving courts have helped them to continue to be competitive applicants for federal, state and local, and sometimes private grant funding over the years and in spite of changing political winds (Wallace 2019).

- Enabling environment

How and to what extent have regulatory and financial systems created/enabled by the government supported problem-solving courts and made it possible for this service/activity to scale?

Most if not all states in the US have allowed drug courts to become part of state legislation, which makes possible their continued operation (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

How and to what extent have the outcomes-based, people-centered services delivered by problem-solving courts been allowed to become the default procedure?

Problem-solving courts have not been allowed to become the default procedure in that adversarial courts and procedures remain the standard way of responding to crime in the US. In the words of Judge Hora, “There is no question that the number of people served is growing, but this remains only a drop in the bucket. For every person served there are 6-7 who aren’t” (Ibid). However, the expanding presence of problem-solving courts has helped the justice sector shift away from the excessively punitive state sentencing laws and tough-on-crime rhetoric of the late 1980s towards a more restorative and evidence-based way of working (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 5, 2020).

Problem-solving courts have enabled cultural change by demonstrating to lawyers and judges that defendants do better when they are able to access treatment, while at the same time allowing these traditional legal players to act as intermediaries and retain a gatekeeping role. As discussed in previous sections, police, prosecutors, and judges alike have grown increasingly comfortable with diverting cases from the adversarial track to community-based treatment (Ibid).

It is a paradox that the US has developed and spread the problem-solving courts model as the country with the highest incarceration rates in the world. Former Senior Advisor of Training and Technical Assistance at the Center for Court Innovation, Julius Lang, speculates that this punitive backdrop is what has allowed alternatives to incarceration to flourish in the US and become so highly developed. At the same time, countries with lower baseline penalties that have set up problem-solving courts, such as Canada and Australia, have developed creative means of engaging defendants who need treatment since there is less of a threat of incarceration (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts stimulated (or benefitted from) investment into justice research and development?

Problem-solving courts have both stimulated and benefited from investment into justice research and development. As discussed in the previous sections, the success of problem-solving courts in the US can be attributed in large part to their strong research partnerships.

From the start, “problem-solving courts always took responsibility for their own research and their own outcomes” (Ibid). Problem-solving justice initiatives run by the Center for Court Innovation, for example, always worked directly with researchers. This produced a huge amount of evaluation literature, which was important for securing the buy-in and funding necessary to continue operating (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 14, 2020).

The fact that federal funding has incentivised high-quality evaluations has also gone a long way to build a foundation of evidence demonstrating drug courts’ effectiveness (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

Leadership + Pathways

How and to what extent have justice sector leaders’ skills and collaborations enabled/hindered problem-solving courts to increase access to justice by delivering the outcomes people need at scale.

Strong leadership has been essential to problem-solving courts’ ability to deliver the treatment outcomes people need at scale. Without the leadership of visionary judges and other leaders aiming to do things differently, they would never have come into existence in the first place.

Because of the tendency to maintain the status quo, individual problem-solving courts also rarely get off the ground without a strong champion. The reason for this can be traced to problem-solving principles and practices themselves: the goal is not to force people to change, but to make them change because they want to. In the same way, effective leaders can persuade system actors that problem-solving justice is the way to achieve common goals (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 14, 2020).

Community courts in particular require strong leadership. This can sometimes pose problems for the courts’ long-term stability. For example, a community court in North Liverpool was championed by prominent national politicians. Their leadership was important for the court’s establishment and initial funding, but changes in national leadership and the lack of local support were major factors in the court’s ultimate closure (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

As mentioned above, community courts may struggle when their early champions move on. To avoid this and prepare for the eventual departure of the personalities who are driving change, it is important to put the courts’ internal ways of working into writing. As previously discussed, it is also necessary to obtain evidence that the court’s approach works, as this is a more important driver of funding than good leadership in the long-run (B. Taylor, personal communication, October 5, 2020).

Mid-level leadership within problem-solving courts also matters. Since staff are often employed and supervised by various partner agencies – rather than the director of the project as a whole – it is particularly important that they be selected with care, trained in the project’s mission, policies and practices, and incentivised to work as part of a single team (J. Jordens, personal communication, October 19, 2020).

How and to what extent have problem-solving courts contributed to/benefited from new high-level strategies or pathways towards people-centred justice in the US?

High-level strategies at the state level and in the form of technical assistance have benefitted problem-solving courts significantly by facilitating their replication. This is particularly true of drug courts, for which state-wide coordination mechanisms were set up at an early stage.

Recognising that substance use disorder was a major problem, and persuaded by the same research as federal legislators, state officials began to set up mechanisms that would allow them to receive federal drug court funding. This also allowed them to strategise about which counties would most benefit from drug courts (or other problem-solving courts), and which standards to impose.

Together, state-wide coordination mechanisms created an infrastructure for the improvement and replication of drug courts nationwide, and made it easier to apply problem-solving practices and principles in new settings. Whereas trainings on brain science and what’s working in treatment used to be reserved for drug court judges, there are now few states that do not include them in judicial training for all new judges. The same can be said for trainings for prosecutors, defence attorneys, and service providers (P. Hora, personal communication, October 16, 2020).

The emergence of technical assistance providers specialising in problem-solving justice such as the Center for Court Innovation, Justice System Partners, the National Center for State Courts, and the Justice Management Institute have also helped problem-solving courts to coordinate and replicate in strategic ways. By developing listservs and organising conferences, these organisations have enabled people in various problem-solving courts to support each other across state and international lines. Over time, these efforts have created shared principles and legitimacy around the movement for problem-solving justice (J. Lang, personal communication, October 28, 2020).

To what extent have problem-solving courts contributed to/played a role in a broader paradigm shift towards people-centered justice?

As mentioned in the introduction, a fifth key feature of the problem-solving orientation is system change. By educating justice system stakeholders about the nature of behavioural problems that often underlie crime and aiming to reach the maximum number of cases within a given jurisdiction, problem-solving courts seek to make broader impact within the justice system and community (Porter, Rempel and Mansky 2010, p. 32-33).

Since the first drug court was set up in 1989, legal professionals have become increasingly aware that many people with social problems end up in the justice system: a system that was never intended to address those problems. Problem-solving courts have contributed to a broader paradigm shift towards people-centred justice to the extent that they have helped these professionals:

- Acknowledge this issue;

- Recognise that lawyers are not equipped to deal with this issue (American law schools do not prepare them to);

- Connect with service providers in the community;

- Leverage the coercive power of the justice system in a positive way;

- Encourage success in treatment programs using procedural justice.

By taking a collaborative approach to decision-making, delivering individualised justice for each participant while at the same time holding them accountable, educating staff, engaging the broader community, and working to produce better outcomes for people, problem-solving courts have demonstrated what people-centred criminal justice can look like in the US and around the world.

View additional information

(1) Methadone is a synthetic opioid used to treat opioid dependence. Taking a daily dose of methadone in the form of a liquid or pill helps to reduce the cravings and withdrawal symptoms of opioid dependent individuals.

(2) “A screening tool is a set of questions designed to evaluate an offender’s risks and needs fairly quickly…An assessment tool is a more thorough set of questions administered before an offender is matched to a particular course of treatment or service.” Taylor 2016, p. 7.

(3) “The main monitoring tool community courts use is compliance hearings, in which participants are periodically required to return to court to provide updates on their compliance.” Taylor, 2016, p. 9.

(4) “Community courts have promoted the use of technology to improve decision-making. Technology planners created a special information system for the Midtown Community Court to make it easy for the judge and court staff to track defendants…Information that’s reliable, relevant, and up-to-date is essential for judges to make the wisest decisions they can.” Taylor 2016, p. 12-13.

(5) In community courts, “judges often speak directly to the offender, asking questions, offering advice, issuing reprimands, and doling out encouragement. This reflects an approach known as procedural justice…Its key components, according to Yale Professor Tom Tyler, are voice, respect, trust/neutrality, and understanding.” Taylor 2016, p. 15.

(6) “Community courts emphasize working collaboratively with the community, arguing that the justice system is stronger, fairer, and more effective when the community is invested in what happens inside the courthouse.” Taylor 2016, p. 22.

(7) Hugh Rodham was the brother of Hillary Clinton, who would become the First Lady a few years later.

View References

Amanda Cissner and Michael Rempel. (2005). The State of Drug Court Research: Moving Beyond ‘Do They Work?’ , Center for Court Innovation.

Brett Taylor. (2016). Lessons from Community Courts: Strategies on Criminal Justice Reform from a Defense Attorney . Center for Court Innovation, p. 3.

Cheryl Wright, (n.d.). Tackling Problem-Solving Issues Across the Country . National Center for State Courts (NCSC).

Cynthia Lee, Fred Cheesman, David Rottman, Rachael Swaner, Suvi Lambson, Michael Rempel and Ric Curtis. (2013). A Community Court Grows in Brooklyn: A Comprehensive Evaluation of the Red Hook Community Justice Center . National Center for State Courts, Center for Court Innovation, p.1.

David Wallace. (2019). Treatment Court: Is Yours Sustainable? (Part Four) . Justice Speakers Institute.

David Wallace. (2019). Treatment Court: Is Yours Sustainable? (Part One) . Justice Speakers Institute.

Dawn Marie Rubio, Fred Cheesman and William Federspiel. (2008). Performance Measurement of Drug Courts: The State of the Art . National Center for State Courts, Volume 6, p. 1.

George Mair and Matthew Millings. (2011). Doing Justice Locally: The North Liverpool Community Justice Centre . Centre for Crime and Justice Studies.

Halsey and de Vel-Palumbo. (2018). Courts As Empathetic Spaces: Reflections on the Melbourne Neighbourhood Justice Centre . Griffith Law Review, 27(4).

Interview with Brett Taylor, Senior Advisor for Problem-Solving Justice, Center for Court Innovation, October 5, 2020.

Interview with Brett Taylor, Senior Advisor for Problem-Solving Justice, Center for Court Innovation, October 14, 2020.

Interview with Brett Taylor, Senior Advisor for Problem-Solving Justice, Center for Court Innovation, October 16, 2020.

Interview with Brett Taylor, Senior Advisor for Problem-Solving Justice, Center for Court Innovation, October 19, 2020.

Interview with Jay Jordens, Education Program Manager – Therapeutic Justice, Judicial College of Victoria, October 19, 2020.

Interview with Judge Peggy Hora, President, Justice Speakers Institute, October 16, 2020.

Interview with Julius Lang, Senior Advisor, Training and Technical Assistance, Center for Court Innovation, October 28, 2020.

Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) , King County.

LEAD National Support Bureau, (n.d.). Evaluations .

LEAD National Support Bureau. (n.d.). LEAD: Advancing Criminal Justice Reform in 2020 .

Mark Halsey and Melissa de Vel-Palumbo. (2018). Courts As Empathetic Spaces: Reflections on the Melbourne Neighbourhood Justice Centre . Griffith Law Review 27 (4).

Matthew Leone, Net widening , Encyclopaedia of Crime and Punishment, SAGE Reference.

National Institute of Drug Abuse (2020). The Matrix Model (Stimulants) , Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide

Office of National Drug Court Policy. (2011). Drug Courts: A Smart Approach to Criminal Justice .

Rachel Porter, Michael Rempel and Adam Mansky. (2010). What Makes a Court Problem-Solving? Universal Performance Indicators for Problem-Solving Justice . Center for Court Innovation, p. 1

Red Hook Justice News. (2016). Bridging the Gap: Youth, Community and Police .

Sarah Matusek. (2017). Justice Center celebrates Bridging the Gap birthday . The Red Hook Star Revue.

Sarah Murray and Harry Blagg. (2018). Reconceptualising Community Justice Centre Evaluations – Lessons from the North Liverpool Experience . Griffith Law Review 27 (2).

Suzanne Strong and Tracey Kyckelhahn. (2016). Census of Problem-Solving Courts, 2012 . Bureau of Justice Statistics.

US Government and Accountability Office, 2005.

Table of Contents

- Case Studies:

- Casas De Justicia Colombia

- Local Council Courts in Uganda

- LegalZoom in the US

- The Justice Dialogue

- Methodology