- Discover our global expertise Project services PMO & Project Delivery Project Dashboards Project Management as a Service (PMaaS) Project Portfolio Execution Strategy execution & Business Improvements Project Management Improvement Agility at scale Change Management Lean Innovation Project Portfolio Management & Optimisation Digital Solutions Digital PMO Deployment of PM Solutions Intelligent Project Prediction (IPP) Clayverest: the PMO's Copilot Case studies Discover how our expertise supports our clients

- Join our team Our company culture Empower your project experience Empower your professional experience Empower your CSR experience Empower your social experience Our job families Project Management Consultant Delivery Manager Business Manager Your profile Early Professional Experienced Professional Our job offers Discover our local and international opportunities

- The Project Management Blog PM Guides Agile Change Management Cost Management Crisis Management Digital PMO Industry Insights Lean Innovation PMaaS PMO Portfolio Management Project Management Delivery Project Managements Roles Risk Management Schedule Management Latest articles Newsroom Case studies Discover how our expertise supports our clients

- Europe France Germany Italy Portugal Romania Spain Switzerland United Kingdom North America Canada Mexico United States Asia South East Asia Oceania Australia Contact Us

Case Study: Improving Risk Culture

- 28 May 2020

- Financial Services , Change Management

Risk management is a key component of every organization’s strategy and operations. Companies make important risk-based decisions every day. At the forefront of such risk decisions are financial institutions. Improving risk culture allows a company to both raise awareness on how to better manage risk, and also to bridge the gap between management operations and organizational values.

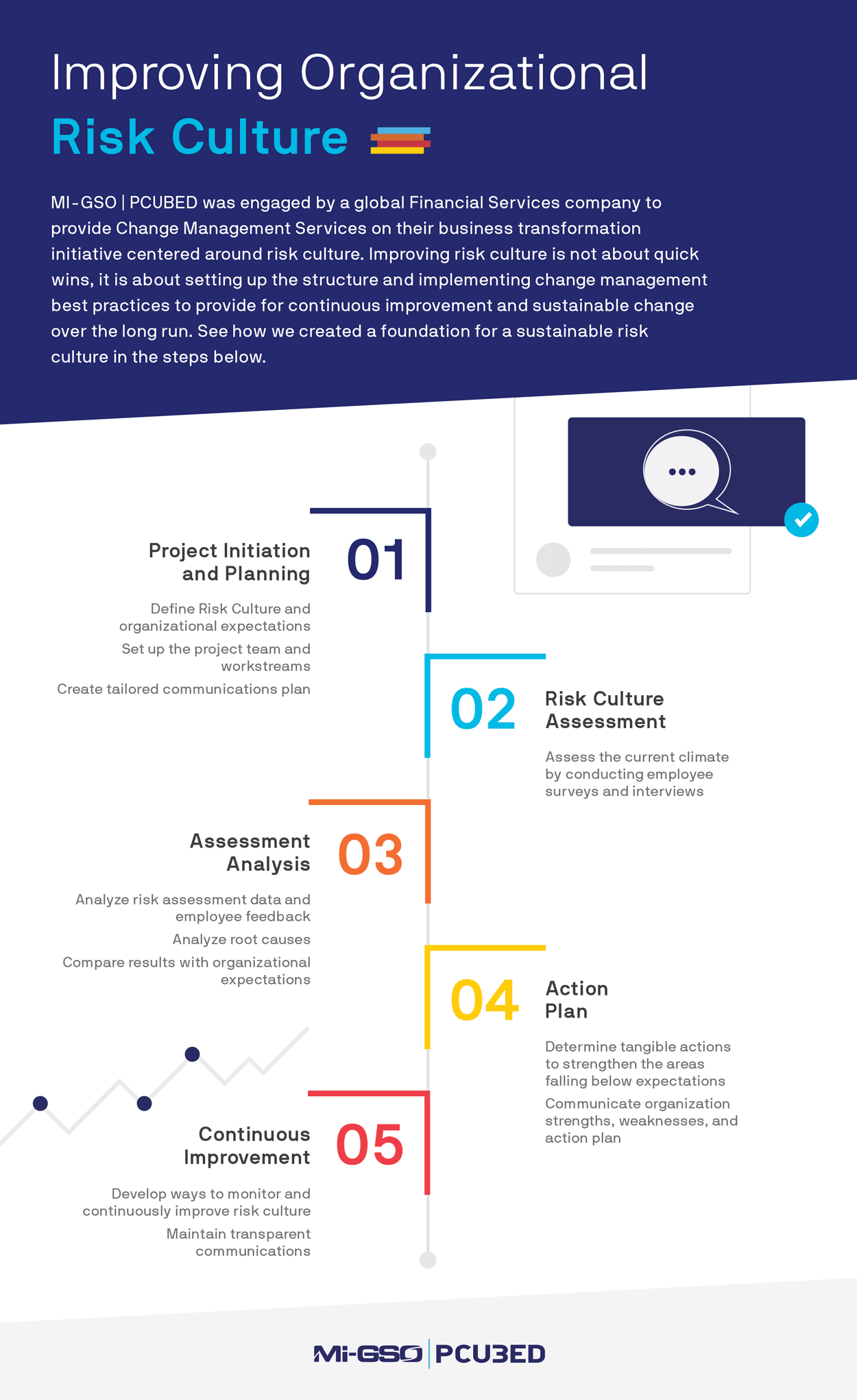

In brief: 5 steps to create a sustainable risk culture

The Challenge

MIGSO-PCUBED was engaged by a federally regulated Financial Services company to provide Change Management Services in support of a company-wide business transformation program.

The program began as a response to recommendations and mandates from regulators. However, risk management had become largely control-driven and lacked consistent awareness among the employee base. Compliance with aggressive regulatory timeframes, competing project scopes, and changes in leadership each contributed to poor risk management.

The change management initiative, therefore, focused on improving the understanding of risk culture across the organization and creating a foundation for a more sustainable culture going forward.

The Solution

For a transformation initiative centered around risk culture improvement, it is important to set up an effective structure – one that successfully nurtures, builds, and supports an environment for change, which, in turn, allows the organization to see and experience long-term benefits and continuous improvement.

Working directly with the Senior Management Committee and key stakeholders, the team quickly structured the business transformation program into six corporate workstreams that would each simultaneously deliver results. Each workstream’s output provided an understanding of current capability, an assessment of gaps against benchmarks, and a clear roadmap for change.

With a structure in place, the team next set out to determine what aspects of their risk culture the client needed to specifically address. With that, we will take a quick detour on risk culture and risk culture measurement.

What is a Risk Culture?

“ Risk culture is the values, beliefs, knowledge, and understanding about risk, shared by a group of people with a common purpose.” – PMI, The ABC of Risk Culture . And, having a robust risk culture is important in more effectively managing risk.

"Risk culture is the values, beliefs, knowledge and understanding about risk, shared by a group of people with a common purpose." PMI - The ABC of Risk Culture

Enterprise risk management includes identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks depending on both the risk tolerance and the risk appetite of the firm. Whereas risk appetite is the amount of total risk an organization is willing to accept, risk tolerance is the day to day or transactional limit.

Want to know more about

By raising risk awareness and understanding, a healthy risk culture aligns a company’s attitudes and behaviors with their business strategy. This ensures that the values and ethics of employees – around risk strategy, appetite, and tolerance – are aligned with those of the organization.

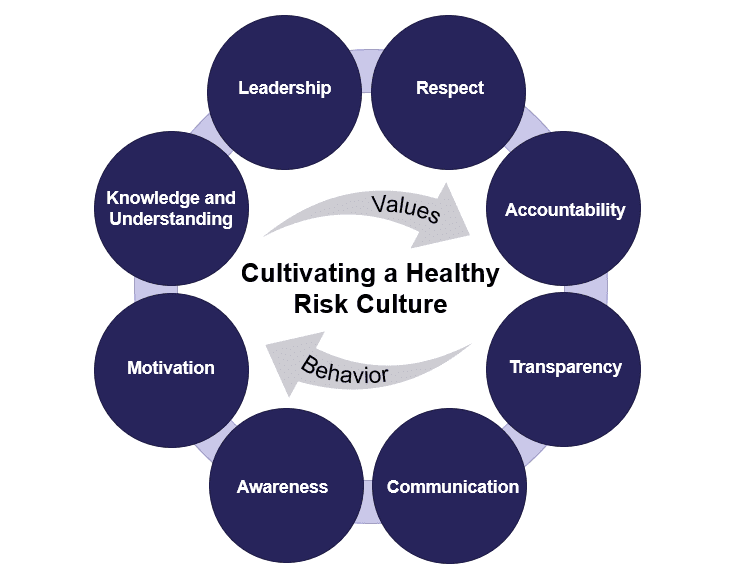

Key elements of a healthy risk culture include Knowledge and Understanding as well as Leadership, Respect, and Accountability. To cultivate those values, you must also be able to observe the behaviors of Transparency, Communication, Awareness, and Motivation.

Bringing Risk Management into Focus

Bringing us to perhaps the most interesting aspect of this project – the focus on risk management and its integration to change management. You may wonder how an organization quantifies their risk management capabilities and overall risk awareness – basically how they conduct a risk culture assessment.

“There is no one good or model culture against which others can be measured and ranked, and no single template or checklist for firms to adopt.” - Banking Standards Board

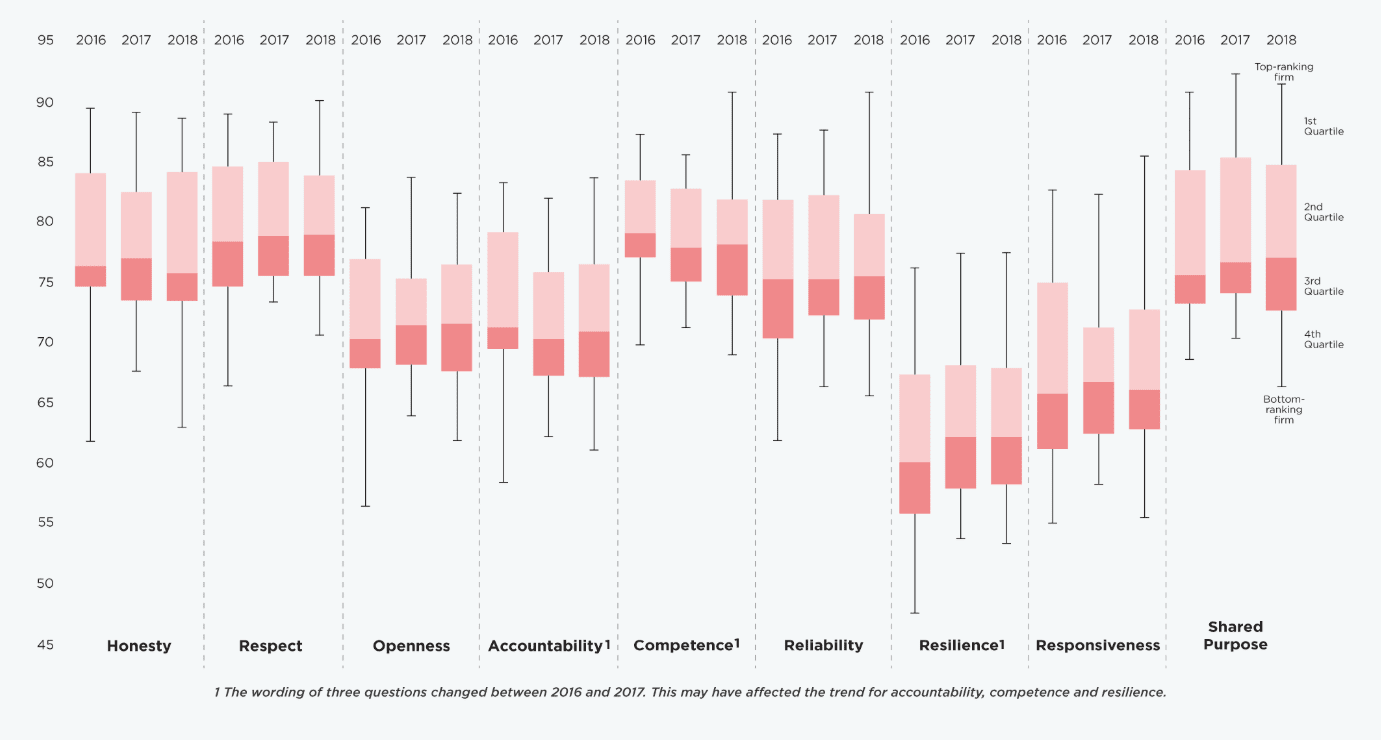

Within the Financial Services industry, the Banking Standards Board conducts an annual assessment with its member firms. While it does not rank their culture directly, it does provide its member firms with feedback against key elements to help them manage their culture more effectively (image below).

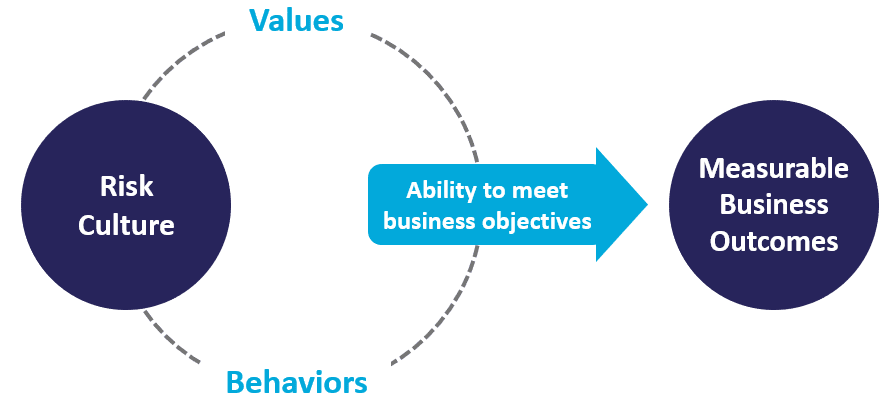

In the same way, risk culture itself cannot be measured. However, an organization can measure its ability to demonstrate risk-related values and meet company objectives. That means an organization must first determine what outcomes are driven by values and behaviors, and then begin to measure them.

What values and behaviors contribute to effective risk management? How can these be measured or evaluated? What actions can an organization take thereafter to establish risk awareness?

To give you an example, with a strong risk culture, employees feel more empowered to speak up and escalate issues. In turn, an organization that encourages employees to raise concerns and issues might observe a decrease in their employee turnover rate. They may also see an increase in the number of reported issues or a decrease in the number of integrity-related risks.

Using an anonymous forum, a company may identify sensitive issues or gauge the number and severity of integrity risks. Using this data, the company can then organize its risk indicators into a dashboard to consistently appropriate and evaluate risk culture.

Implementing a Risk Culture Approach

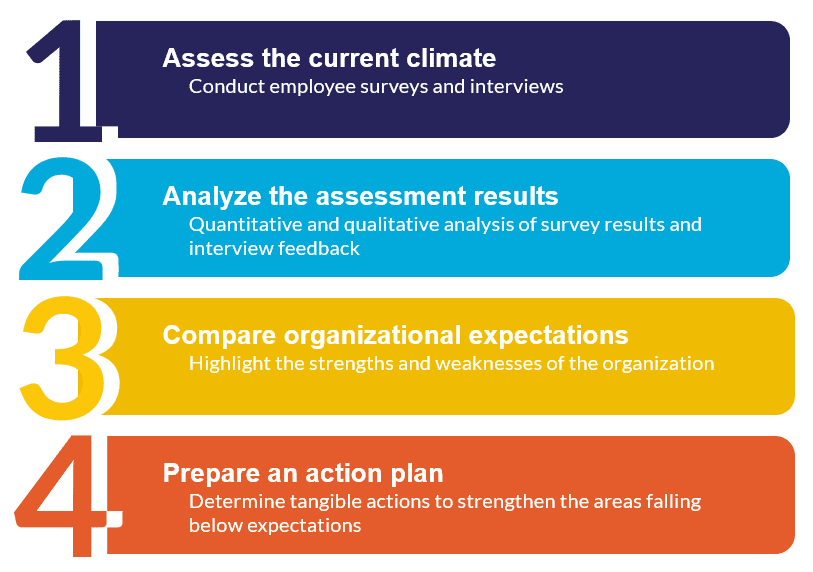

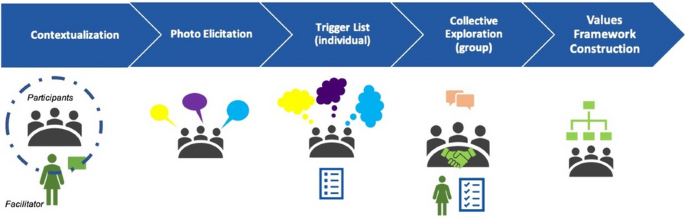

Adopting this approach, the MIGSO-PCUBED change management team led the client through each of the 4 steps in the graphic below. The team leveraged core Change Management tools and techniques beginning with assessing the current climate and analyzing in comparison to organizational expectations. The team then defined a set of tangible actions mapped to a change roadmap of short, medium, and long term actions to strengthen areas falling below expectations.

Additionally, they established a robust governance and planning structure, and tailored communications to facilitate a more sustainable business transformation initiative.

The Benefits

In the short term, the MIGSO-PCUBED team has supported the client in building a company-wide and unified understanding of their corporate risk culture. Roles and responsibilities are better understood. Moreover, the client is observing greater risk awareness and more effective risk management practices.

The client also has the means to assess and monitor their risk culture going forward in the short, medium, and long term. This allows them to identify gaps and take action more proactively in driving risk culture. This highlights the longevity of the business transformation initiative long after its closure, as its outputs are fully integrated into the organization.

This article was written by Elaina Wheeler and Victoria Emslie .

You might also like:

Global Supply Chain Schedule Integration

PMO Delivery within Nuclear

Throwback to the start of our first Swiss hub with Marie Timmerman, Business Manager in Geneva

Loved what you just read? Let's stay in touch.

No spam, only great things to read in our newsletter.

We combine our expertise with a fine knowledge of the industry to deliver high-value project management services.

MIGSO-PCUBED is part of the ALTEN group.

Find us around the world

Australia – Canada – France – Germany – Italy – Mexico – Portugal – Romania – South East Asia – Spain – Switzerland – United Kingdom – United States

Follow us here

© 2024 MIGSO-PCUBED. All rights reserved | Legal information | Privacy Policy | Cookie Settings | Intranet

Perfect jobs also result from great environments : the team, its culture and energy. So tell us more about you : who you are, your project, your ambitions, and let’s find your next step together.

- Netherlands

South East Asia

Switzerland

United Kingdom

United States

In accordance with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR), the data entered is processed for the management of recruitment and its improvement. To find out more, visit our privacy policy .

Dear candidates, please note that you will only be contacted via email from the following domain: migso-pcubed.com . Please remain vigilant and ensure that you interact exclusively with our official websites. The MIGSO-PCUBED Team

Discover our global expertise →

Project Services →

Strategy Execution & Business Improvements →

Digital Solutions →

Our case studies →

Join our team →

Company Culture →

Job Families →

Choose your language

Subscribe to our Newsletter

A monthly digest of our best articles on all things Project Management.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Our website is not supported on this browser

The browser you are using (Internet Explorer) cannot display our content. Please come back on a more recent browser to have the best experience possible

Browser does not support script.

- LSE Research for the World Strategy

- LSE Expertise: Global politics

- LSE Expertise: UK Economy

- Find an expert

- Research for the World magazine

- Research news

- LSE iQ podcast

- Research films

- LSE Festival

- Researcher Q&As

Impact case study

Influencing risk culture change processes in financial institutions.

The research … put a more rigorous framework around the discussions of the implications of different organisational structures for risk-taking; in particular, more complex organisations might be driven beyond their bandwidth for risk-taking by specific hot spots in the organisation. This focused attention on the need to consider the trade-offs between risk taking and controls. Former partner at EY and senior regulator at the Bank of England

Research by

Professor Michael Power

Department of accounting.

Dr Tommaso Palermo

LSE research explored the dynamics and trade-offs involved in managing risk cultures in financial institutions, shaping how the industry understands approaches to risk-taking and control.

What was the problem?

Financial organisations need to take risks, but if those risks are uncontrolled or reckless, then the damage caused by very large organisations is immense. And so it matters that we understand the cultures that shape approaches to risk-taking and control in organisations, and the trade-offs involved.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 to 2009 focused new attention on a perceived culture of reckless risk-taking by financial organisations, especially banks. In response, many institutions and policymakers wanted to develop a consolidated understanding of organisations’ efforts to better understand and act on their risk cultures. The financial crisis also raised questions about the influence of financial regulators and consultants on these organisational conceptions of risk culture, and the capacity for and consequences of consciously measuring, managing, changing, and auditing risk cultures.

What did we do?

To understand how risk cultures operate within financial institutions, Professor Michael Power and Dr Tommaso Palermo, along with Dr Simon Ashby (then at the University of Plymouth, now Vlerick Business School), engaged directly with the key actors in the financial sector charged with operationalising ways to assess, manage, and report on organisational risk cultures.

Between 2012 and 2015, the team conducted field-based research, drawing on observations and interviews alongside surveys and documentation analysis. They conducted interviews with 61 individuals in financial institutions, professional associations, regulatory bodies, and consulting firms. They also used survey questionnaires in some participant organisations to explore relevant aspects of business operations, such as interactions between control functions and revenue-generating teams. Focus group discussions, facilitated by the researchers, allowed them to collect additional data by observing senior managers’ reactions to, and interpretation of, assessments of their organisations’ risk cultures.

From this body of research Power, Ashby, and Palermo developed a framework that concisely models different approaches to risk culture assessment and management and their potential trade-offs. The insights, refined in a 2017 paper , make an important contribution to academic understanding of risk culture, while further research compared risk culture in the financial sector with safety culture in high-risk sectors such the airline industry .

The research showed how good practice entails awareness of the trade-offs inherent in the different approaches to managing risk cultures, rather than being prescriptive about how much risk to take. The research also revealed how firms tend to focus for pragmatic reasons on a few key issues, rather than developing a holistic framework to risk culture assessment. They concentrate, for example, on how to foster revenue-generating units’ respect for risk and compliance functions; the creation of new risk oversight units and capabilities; and dealing with new regulatory entities such as the Financial Conduct Authority.

In addition to documenting different approaches to risk culture assessment and management, the longitudinal field study engagement with different organisations helped the researchers to appreciate how risk culture has become more “auditable” over time, with a shift towards organisations adopting formal toolkits and oversight structures. This has significant managerial implications, since it frames corporate risk culture as something that can be inspected and validated by boards of directors and regulators, despite initial scepticism about formal diagnostic toolkits and measurable performance indicators.

The research team used these insights to develop a suite of “smart questions” about risk culture for companies to use either as a stand-alone set or as a follow-up to diagnostic tools such as surveys. The answers to these “smart questions” are specific and targeted, raising awareness about key cultural hotspots to address, but together they provide a useful snapshot of organisational risk culture.

What happened?

These insights on risk cultures have influenced how financial services organisations around the world understand their own practices. Although the aim was not to develop a new tool to measure risk culture, it has supported industry efforts to do so.

The initial report was shared widely among financial organisations, including banks, insurance companies, and industry regulators. It has, along with subsequent publications, become a reference point in the risk culture debate within the sector. Its reach is evident in the wide range of regulators, professional bodies, and advisory firms that cite it in policy and guidance documents and in the invitations the researchers have received to present their evidence to senior staff in regulatory authorities, along with professional bodies, banks, and within academia.

The research has informed new industry guidance aimed at improving understanding, monitoring, and development of risk cultures. In 2014, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system, cited the research in their report on assessing risk culture. This new guidance was intended to help supervisors assess the soundness and efficacy of a financial institution’s risk culture. As with other FSB publications, its intended users are the financial institutions of the world’s largest economies, international financial institutions, and international standard-setting organisations. The FSB report has become a central reference point for corporate and regulatory initiatives on risk culture.

Professor Power and Dr Palermo’s work has also been cited in several other policy and guidance documents, such as ones published by the CRO Forum , a group of Chief Risk Officers from multinational insurance companies; the Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors (CIIA); and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), an independent statutory authority supervising banking, insurance, and superannuation institutions.

The collaborative nature of the research has also helped to deliver direct impacts within participating organisations, and organisations that have contacted the research team subsequently to learn about the report findings and to share the results of their own internal risk culture workstreams. One indicative example is a major insurance company, which contacted the researchers in September 2017 leading to an ongoing collaboration with direct impact on corporate practice. Dr Palermo worked with senior members of the company’s internal audit function to develop and refine its method of assessing risk and control culture as part of the audit process.

Related content

Article: investigating risk cultures in financial institutions, counterparty credit risk management at barclays: estimating extreme quantiles, analysing and learning from healthcare complaints, more by michael power, rejection sampling and agent-based models for data limited fisheries.

Author(s) Michael Power

How culture displaced structural reform: problem definition, marketization, and neoliberal myths in bank regulation

Memories lost: a history of accounting records as forms of projection, the firm that would not die: post-death organizing, alumni events, and organization ghosts, more by tommaso palermo, the value of research activities “other than” publishing articles: reflections on an experimental workshop series.

Author(s) Tommaso Palermo

How accounting ends: self-undermining repetition in accounting lifecycles

How do accounts pass a discussion of vollmer’s “accounting for tacit coordination”, how to improve the risk cultures of financial institutions.

Banks’ risk culture and management control systems: A systematic literature review

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 13 August 2021

- Volume 32 , pages 439–493, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jennifer Kunz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4843-824X 1 &

- Mathias Heitz 1

11k Accesses

9 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Over ten years of a debate about the best ways to make banks safer have led to the conclusion that improving their risk culture is one venue to achieve this goal. Consequently, different disciplines discuss topics related to risk culture from varying methodological angles. This effort of many scholars provides a rich basis of theoretical and empirical evidence to guide business practice and improve regulation. However, the application of many approaches and methods can result in fragmentation and loss of a comprehensive perspective. This paper strives to counteract this fragmentation by providing a comprehensive perspective focusing particularly on the embeddedness of risk culture into banks’ management control systems. In order to achieve this goal, we apply a systematic literature review and interpret the identified findings through the theoretical lens of management control research. This review identifies 103 articles, which can be structured along three categories: Assessment of risk culture , relation between risk culture and management controls (with the subcategories embeddedness of risk culture in overall management control packages, risk culture and cultural controls, risk culture and action controls, risk culture and results controls, as well as risk culture and personnel controls) and development of banks’ risk culture over time . Along these categories the identified findings are interpreted and synthesized to a comprehensive model and consequences for theory, business practice and regulation are derived.

Similar content being viewed by others

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Implementation: A Review and a Research Agenda Towards an Integrative Framework

Tahniyath Fatima & Said Elbanna

Meta-analyses on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): a literature review

Patrick Velte

A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility

Mauricio Andrés Latapí Agudelo, Lára Jóhannsdóttir & Brynhildur Davídsdóttir

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The banking and economic crisis of 2007/8 resulted in the call for a fundamental change of banks’ professional norms (e.g., Cohn et al., 2017 ; Palermo et al., 2017 ; Pan et al., 2017 ; Power et al., 2013 ) and regulators started to emphasize the concept of risk culture in their standard setting (e.g., Carretta et al., 2017 ; European Banking Authority (EBA), 2017 ; Financial Stability Board (FSB), 2014 ).

As risk culture is part of qualitative regulation, those standards considering this topic provide a wide range of qualitative recommendations, covering internal controls, like remuneration, but also soft factors, like open communication (e.g., FSB, 2014 ). This qualitative character of risk culture and the related recommendations to establish it in a reasonable way, constitute a major challenge for banks: As literature on management controls stresses, corporate culture – and thus also a firm’s risk culture as part of this corporate culture – constitutes a socially constructed management control system (Bedford & Malmi, 2015 ; Malmi & Brown, 2008 ; Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017 ), and it is embedded into a whole set of further management controls (Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017 ). Thus, when trying to develop an appropriate risk culture, banks have to cope with the need to change socially constructed entities and they have to consider and understand the mentioned embeddedness in whole sets or packages of management controls. Moreover, banks are confronted with partly contradicting external requirements, e.g., there is a strong tension between market and regulatory demands (Lim et al., 2017 ), which in turn result in contradicting demands with respect to risk behavior. If such complexities are neglected, the application of particular instruments to establish a reasonable risk culture might miss the intended effect (Power et al., 2013 ).

Due to this need for deeper insights into how risk culture can be implemented and managed successfully and sustainably in banks, since the last financial crisis scholars devoted increasing attention to this topic. For example, they discussed issues as diverse as the impact of incentive systems (Gande & Kalpathy, 2017 ; Iqbal & Vähämaa, 2019 ; Schnatterly et al., 2019 ) or the way to measure risk culture (e.g., Sheedy, 2016 ; Sheedy et al., 2017 ). Within these emerging research fields different methods and theoretical perspectives are applied. This differentiation fosters a pluralistic perspective on banks’ risk culture and thereby provides the possibility to develop a broad set of recommendations for business practice and regulation. However, it also bears the risk of fragmentation and mitigates the development of a comprehensive view on banks’ risk culture. Particularly, as different authors stress different building blocks to achieve a proper risk culture, it is difficult to select and prioritize the relevant building blocks. This is all the more true since regulators do not show causal relationships between individual building blocks in their papers, but rather list them individually. Moreover, scholars disagree on the relation between certain instruments and risk culture. For example, Stulz ( 2016 ) discusses incentives and culture as two distinct measures to influence prudent risk-taking, while McConnell ( 2013 ) mentions remuneration as integral component of risk culture. Finally, in the wake of the last financial crisis, the discussion on risk culture became ethically inflated, as an inadequate risk culture is seen as an important reason for misconduct. In summary, there are many reasonable views on risk culture in banks, but they need to be integrated to develop a more coherent understanding that allows banks to develop their risk culture in an appropriate direction.

The present paper aims to provide insights for such a coherent understanding by focusing particularly on the embeddedness of risk culture into banks’ management control systems. In order to achieve this goal, we apply a systematic literature review and interpret the identified findings through the theoretical lens of management control research. When defining a clear-cut inclusion criterion for the considered articles in this review, we have to consider that this field of research is still under development. In order to cover the relevant literature, we selected those articles which simultaneously deal with risk culture and management control systems or particular elements of these systems both in the sense of explicitly combining them but also in the sense of discussing them in a less related way. Thus, we consider both articles which explicitly strive to understand risk culture in relation to management control systems and articles which at least point to the fact, that risk culture has to be understood in the broader context of (elements of) management control systems, without necessarily providing the precise relations between them. The application of this systematic literature review allows the structured discussion of recommendations for business practice and regulation as well as the derivation of promising paths for future research. Thereby, the analysis mitigates increasing fragmentation and helps to direct future research effort to existing blind spots.

On the one hand, our study extends the mainly interpretative research in management control literature that aims to foster the understanding of effective practices to achieve an appropriate risk culture (e.g., Mikes, 2009 , 2011 ; Power, 2009 ). By combining evidence from this literature with further insights from other research streams on risk culture, we broaden the perspective and provide a comprehensive view on risk culture as management control system and its embeddedness within other management control systems. This makes our study one of the few analyses that deal explicitly with the relationship between risk culture and management control systems. On the other hand, we provide evidence to enhance theory and business practice on risk culture in banks by compiling the current state of research, bringing together the most important findings and highlighting existing research gaps. Particularly, we discuss in detail issues related to the assessment of risk culture, the relation between risk culture and other management controls and the possibility to change risk culture. Moreover, we provide a comprehensive model relating risk culture to other management control systems in order to disentangle their complex relationships. From these insights, we draw recommendations for business practice, regulators, education and research.

The remaining paper is structured as follows: To lay the ground for the following analysis, in Sect. 2 we derive a definition of risk culture within banks and relate it to management control research. Based on this combination we elaborate on the relevant categories to be analyzed in order to derive the intended comprehensive view. Section 3 provides detailed information regarding the procedure to identify the relevant literature for the systematic literature review. Section 4 covers the results of the systematic review and in Sect. 5 we discuss these results. Section 6 contains concluding remarks and the discussion of the limitations.

2 Risk culture and management controls

According to Schein ( 1990 ) organizational culture is the derivative of organizational learning processes through which particular norms and behavioral patterns have evolved that served to solve problems in the past. It “may be defined as the shared basic assumptions, values, and beliefs that characterize a setting and are taught to newcomers as the proper way to think and feel, communicated by the myths and stories people tell about how the organization came to be the way it is as it solved problems associated with external adaptation and internal integration” (Schneider et al., 2013 , p. 362). As a consequence, organizational culture is a dynamic organizational phenomenon whose content can change over time dependent on organizational learning within changing environments due to external pressure und internal processes. Risk culture forms part of the overall organizational culture and describes the way an organization takes and manages risk (e.g., Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), 2016 ). Similar as overall organizational culture, also risk culture develops according to learning processes related to external and internal determinants, as exhibited by relevant definitions.

One frequently cited definition is applied by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) ( 2009 ), which is also used by the FSB ( 2014 ) and the APRA ( 2016 ). They define risk culture as “the norms and traditions of behavior of individuals and of groups within an organization that determine the way in which they identify, understand, discuss and act on the risks the organization confronts and the risks it takes” (IIF 2009 , p. 35). According to the Institute of Risk Management (IRM) ( 2012 , p. 7) risk culture comprises “the values, beliefs, knowledge and understanding about risk, shared by a group of people with a common intended purpose, in particular the leadership and employees of an organization.” Another well-known definition of risk culture as “bank’s norms, attitudes and behaviors related to risk awareness, risk-taking and risk management and controls that shape decisions on risk” is provided by the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (BCBS) ( 2015 , p. 2). Overall, these definitions stress the importance of individual perceptional and cognitive processes in combination with social interactions for the evolution of a bank’s risk culture.

The literature further states that different organizations also can have different risk cultures (IRM 2012 ). Moreover, as the norms and traditions related to risk culture are formed via shared experiences over time, and these experiences are driven by various external factors, also various sets of shared norms and traditions within organizations are possible.

However, despite the possible differences between risk culture across and within banks, the FSB ( 2014 ) suggests four core elements that support a sound risk culture in each bank: tone from the top , accountability of employees , adequate incentives and effective communication and challenge . The IRM ( 2012 ) adds further aspects, like the commitment to ethical principles or risk event reporting. These aspects are part of an overarching management concept that is anchored in the bank’s internal management control systems. Thus, as also outlined by the APRA ( 2016 ) in addition to the less formal psychological and social processes mentioned above, formalized systems also have an influence on the orientation of risk culture.

Finally, the adequacy of a particular risk culture must always be assessed in the light of a bank’s business model. Regulators expect banks to implement a prudent risk culture, which does not necessarily mean that banks should be as risk-averse as possible. Rather, it is intended to promote a risk behavior that only allows the bank to take acceptable risks, so that it can prosper sustainably and does not get into financial difficulties (e.g., FSB, 2014 ).

Overall, the mentioned definitions stress that risk culture refers to a general organizational attitude towards risk and its handling. It constitutes the shared experiences of individuals and comprises norms, values, traditions, and attitudes, which lead to particular activities related to the handling of risk and its consideration in decision processes. It is formed through the interaction between informal psychological and social processes , formal instruments, like reward systems, and external circumstances, like regulation . Risk culture is therefore an elusive phenomenon, the development of which is difficult to predict. Nevertheless, regulators expect banks to exert a targeted influence on their risk culture and to develop it in an appropriate direction, i.e. in a manner that fits to their business model and does not result in financial distress.

Management control systems can be defined as a collection of practices that are intended to align staff’s decision-making and action taking with overall organizational goals (e.g., Anthony, 1965 ; Berry et al., 1995 ; Chenhall, 2003 ; Gooneratne & Hoque, 2013 ). While in older research a more objective perspective on management controls can be observed, more recently scholars stress that management control systems “are also viewed as socially constructed phenomena within the particular context in which they operate; being subjected to wider social, economic and political pressures” (Gooneratne & Hoque, 2013 , p. 147). Given this definition, on the one hand, it becomes clear that literature of management controls can help to make sense of banks’ risk culture and its relation to the mentioned instruments as well as to foster its active development into an adequate direction. On the other hand, according to this literature, culture is its own management control system (Malmi & Brown, 2008 ; Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017 ). Thus, a deeper understanding of risk culture, as a particular part of culture, also can inform management control research. Especially it can add insights to the growing research stream on management control systems in banks (Gooneratne & Hoque, 2013 ). In order to achieve both goals, we derive three issues, which are to be clarified by the systematic literature review.

First, the idea of management controls is closely related to the idea of making issues relevant to organizational goal achievement assessable. At first glance, this statement seems to be at odds with the previously derived definition of risk culture and the conclusion that it is an elusive phenomenon. Moreover, particularly authors from the field of management controls, like Power ( 2009 ) and Mikes ( 2009 ), are rather critical regarding a culture of assessment or even precise measurement in the context of risk culture. However, in order to embed the active management of risk culture within banks, this management process has to be conceptualized in a way that fits to the general thinking within this industry. The banking industry not only has to cope with qualitative but also with quantitative regulation, which still results in a clear focus on measurable aspects. Moreover, in order to learn about possible progress made in developing an adequate risk culture (i.e. a risk culture that fits the selected business model), banks need clear benchmarks. Consequently, possible ways of assessing risk culture constitute the first category of the following systematic literature review. In detail, we elaborate on existing assessment instruments in extant literature and on the need for future research.

Second, as previously discussed, to achieve a risk culture that fits to the selected business model, regulators as well as recent literature propose to implement certain instruments, like appropriate incentive systems, adequate communication structures and suited leadership. Thus, the understanding of the relation between particular instruments as part of management control systems and banks’ risk culture constitutes a second important issue. Management control research provides frameworks to foster this analysis. Based on previous research (e.g., Galbraith, 1973 ; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967 ; Perrow, 1970 ; Thompson, 1967 ), Chenhall ( 2003 ) classifies management controls in the two broad categories of organic, less standardized and mechanistic, formalized management controls. Merchant and Van der Stede ( 2017 ) provide a more nuanced categorization by differentiating results controls (focusing on the outcomes of employees’ work activities), action controls (setting decision frames within that decision makers can operate), personnel controls (ensuring a good fit between the recruited employees and the job requirements) and cultural controls (norms, traditions and organizational values). Malmi and Brown ( 2008 ) separate five types of management controls: Planning controls are dedicated to the definition of targets of different business units and their coordination. Cybernetic controls constitute activities that ensure goal achievement through for example budgets and performance measures. Reward and compensation controls comprise incentive systems to motivate employees to behave in accordance with organizational goals. Administrative goals consist of organizational structures, procedures and routines. Cultural controls focus on the application of organizational norms and values to influence employees’ behavior.

Banks’ risk culture is part of cultural controls and as such, forms part of organic, less standardized management controls. In contrast, those aspects that are discussed in literature as important to reach a risk culture that fits the business model form part of other management controls, like results/rewards and compensation controls. The systematic literature review builds on this observation and serves to identify these aspects discussed to date and their relation to risk culture. To assure a structured discussion of the articles assigned to this category, we apply the framework designed by Merchant and Van der Stede ( 2017 ), that provides the subcategories cultural, action, personnel and results controls. In the first subcategory, cultural controls , we present articles that for example deal with different manifestations of risk culture as one form of cultural controls, that emphasize ethical aspects as another part of cultural controls or that indicate an impact of national culture in this context. Further three subcategories deal with articles which provide insights regarding one of the relations between banks’ risk culture and action, personnel and results controls. Additionally, we identified articles which deal with more comprehensive frameworks related to banks’ risk culture comprising issues considering all kinds of management controls. These articles are discussed in one further subcategory.

Third, management control systems are not static, but they develop over time, the same holds for banks’ risk culture and its embeddedness in banks’ overall management control systems. This observation leads to a third important issue which is related to the nature of the change and the changeability of risk culture in banks and its relation to management controls.

To get a comprehensive overview of the recent developments in risk culture research we performed a systematic literature review (Tranfield et al., 2003 ). The previous discussion on risk culture in Sect. 2 indicates, that risk culture, as an immaterial, organizational and social phenomenon, is difficult to delimit, which complicates the design of a systematic literature review, as many aspects can affect it, which in turn become important for management control systems to manage it. In order to do justice to this problem and the continuous progress of research in this rapidly growing field, we have conducted multi-phase research. The starting point here was a broad view on the topic.

As adequate risk culture is reflected in risk taking behavior that fits to the selected business model, in the first phase we focused on both, articles that explicitly cover the topic banks’ risk culture and papers that deal with risk taking in banks. However, with respect to the latter topic we concentrated on papers that are related to qualitative regulation, i.e. aspects of quantitative regulation like proper risk measurement tools, capital requirements, credit regulation regimes and similar aspects were not considered. In order to achieve a broad perspective on the topic, in this first phase we included peer reviewed articles from two different sources. Furthermore, as we deemed risk culture as a more recent concept in the area of bank regulation, we restricted this first search phase to the time period of January 1997 to the beginning of November 2019.

First, we performed a comprehensive database research of articles in the Abi Inform Complete database (only peer reviewed articles, English language) with the keywords risk culture, risk climate, risk management and risk taking as part of the title, abstract or keywords in the articles. This search was intended to provide a broad overview of relevant articles across all levels of peer-reviewed journals without any restrictions in terms of ranking levels. Due to the great amount of unfitting search results, we had to narrow, where appropriate, the thematic scope by applying by the database provided pre-set filters to exclude articles focusing on other research topics, such as for example public health. This search procedure provided in a first step the results illustrated in Table 1 , where the first row shows the results without the pre-set filters and the second row those results applying the pre-set filters, respectively.

However, despite the application of the pre-set filters, the received hits still contained a large number of articles, which were not in the focus of the present study, as they did not deal with risk culture in the banking industry, but e.g. risk taking related to sexual behavior or risks related to climate change. A research fellow (master level) knowledgeable in the field of risk management scanned these articles for their relation to risk culture in terms of a general organizational attitude towards risk and its handling in banks. This procedure resulted in 95 articles, which he considered as potentially relevant.

Second, in this first phase we in parallel performed an additional in-depth search in several premium journals to additionally identify those articles which were not listed in the database or which were related to our topic but could not be identified via the keywords within the database. We decided to perform this step, although it might result in a certain bias as here we explicitly focus on highly ranked journals, as we consider articles in these journals to be the most impactful, whose neglect in an overview would result in considerable restrictions. By pursuing this double strategy (database search and journal search) we try to do justice to the tension between breadth and depth of a literature review as mentioned by Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ), which arises especially in a still young and self-defining field.

As we focus on both risk culture in banks, i.e. a finance topic, and management control systems, i.e. a management control topic, we selected journals from two disciplines: On the one hand, as we focus on risk culture in banks, we considered financial premier journals. We identified the following journals using journal ranking and bibliometric studies (e.g., García-Romero et al., 2016 ; Ritzberger, 2008 ; Schäffer et al., 2011 ) and a range of journal rankings compiled and updated regularly by Anne Will Harzing (available at: https://harzing.com/resources/journal-quality-list ): Journal of Finance; Journal of Financial Economics; Journal of Banking & Finance; Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control; Review of Finance; Review of Financial Studies; Journal of Financial Intermediation; Journal of Money, Credit & Banking. On the other hand, as risk culture is part of banks’ management controls, we additionally searched within premier journals that cover management control research. We selected Journal of Accounting and Economics, Journal of Accounting Research, The Accounting Review, Contemporary Accounting Research, Management Accounting Research and Accounting, Organizations and Society as premier accounting journals based on Bonner et al. ( 2006 ) and Balstad and Berg ( 2019 ). The search, which was performed by reading the title and the abstract, in these premier journals lead to 310 potentially relevant articles.

The search in the journals was conducted independently by one of the two authors and partly by a research fellow (master level) knowledgeable in the field of risk management.

In the further process the authors once again read the abstracts or, if necessary, the complete texts of the articles so far identified in the database and the premier journals as potentially relevant. During this process further articles were identified which, in contrast to our or the research fellow’s initial judgement, did not provide insights directly related to risk culture as a qualitative aspect of regulation, but 1) focused mainly on aspects related to quantitative regulation like risk measurement or capital requirements, 2) covered a much broader perspective, like risk management or risk taking in banks in general or 3) dealt with risk management in general independently of the industry. Therefore, further articles, which were initially considered as potentially relevant by one of the authors or the research fellow, were excluded from our sample after debating it with the other author. Moreover, those articles which focused on risk culture in the sense of the present paper were further analyzed whether they also contained a relation to management control systems as defined in the present paper. This procedure reduced our sample from initially 405 potentially relevant articles to 37 articles. One further article was eliminated due to a reviewer recommendation during the revision process leading to a sample of 36 relevant articles. To assure completeness of our sample, we hereafter executed a backward search, i.e. we analyzed the literature of our sample and identified 15 additional articles that we considered in our further analysis. Finally, we retained 51 articles in our sample.

However, as research on risk culture is conducted with growing interest and published in a broad range of journals apart from premium journals and potentially not listed in the ABI Inform Complete database, we decided to execute a second search phase in June 2020. During this search, we did not focus on a pre-set period of time to additionally also cover literature, which was overlooked during the first phase as it was published before the pre-set time frame. We decided to make this change to the search framework because when we read the articles already identified we noticed that some older sources were indeed cited. We searched the following databases: Abi Inform Complete (226 hits), Business Source Premier/EconLit (111 hits), Ingenta (225 hits) and Science Direct (114 hits) with the search strings “risk culture AND bank” and “risk climate AND bank” in title , abstract or keywords . It has to be mentioned, that due to this more focused search strategy in terms of the search string, this second search provided a much lower number of initial hits, while yielding a number of additional articles almost comparable to the outcome of the first search phase. Additionally, we searched the first 200 hits of Google Scholar applying these search strings. The total amount of hits contained 148 duplicates. After reading the abstracts and partly the papers, we identified 32 articles additionally to the previously selected papers. These articles also were subject to a backward search, which yielded 20 further papers. Thus, in total we identified 103 relevant articles.

The identified literature is structured along those categories that are derived in Sect. 2 : The first category focuses on the assessment of risk culture. The second category deals with the relation between risk culture and particular management controls or packages of them. We differentiate five subcategories: The first subcategory contains articles dealing with more holistic aspects regarding the embeddedness of risk culture in overall management control packages. They mention several management controls simultaneously. The remaining four subcategories are dedicated to articles which focus on one of the four management control types introduced by Merchant and Van der Stede ( 2017 ), i.e. cultural, action, results and personnel controls. In the third category we elaborate on issues related to the development of banks’ risk culture over time.

Table 2 provides an overview of the papers, the applied method and the sample, where applicable. Table 3 constitutes the concept matrix resulting from categorizing the content of the identified articles (Webster & Watson, 2002 ).

4.1 Assessment of risk culture

Literature regarding the assessment of risk culture still is scarce. We identified two validated scales and one framework. Sheedy et al. ( 2017 ) present a scale of 16 items (structured along four factors) to measure the perception of risk culture, which they call risk climate. The scale comprises the following dimensions: “Valued: Staff perceive that risk management is genuinely valued within the organization […] Proactive: Staff perceive that (in the local business unit) risk issues and events are proactively identified and addressed […] Avoidance: Staff perceive that risk issues and policy breaches are ignored, downplayed or excused in the organization […] Manager: Staff perceive that their (local) manager is an effective role model for desirable risk management behaviours” (Sheedy, 2016 , p. 6). Sheedy ( 2016 ) uses this scale to investigate the relation between risk climate and banks’ size. Sheedy and Griffin ( 2018 ) apply this scale to analyze staff’s perception of risk culture and its relation with risk structures and risk behavior, i.e. in this recent publication, they switch from their previous term risk climate to risk culture. The data (30,126 responses by staff of banks in Australia and Canada in the period of 2014 to 2015) provides evidence for varying perceptions with regard to the quality of risk culture between business units and business lines and a rather complex relation between risk structures, risk culture and risk behavior.

Muñiz et al. ( 2020 ) present another 18-item scale to assess risk culture in banks considering the four building blocks according to the FSB (tone from the top, accountability, effective communication and challenges, incentives), i.e. they more closely follow regulators’ specifications, but also focus on staff’s perceptions.

Thakor ( 2016 ) transfers the Competing Value Framework to banks’ credit culture to create an instrument, which allows banks to assess their culture. The original framework differentiates the four corporate culture orientations compete, create, control and collaborate, which are related to different leader styles, value drivers and basic assumptions about the means to effectively achieve goals (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983 ). Thakor ( 2016 ) adapts this framework to assess credit culture and differentiates competitive individual culture (compete), product-innovation-focused culture (create), risk-minimization-focused culture (control) and partnership culture (collaborate). Banks act differently in the context of credit risk management depending on the particular culture type. In contrast to the two previously mentioned assessment instruments, Thakor ( 2016 ) does not provide a validated scale, but rather points to a more subjective self-assessment process.

4.2 Relation between risk culture and management controls

4.2.1 embeddedness of risk culture in overall management control packages.

On a conceptually basis, several scholars develop and discuss comprehensive frameworks to foster banks’ risk culture, which highlight learning from failure, organizational resilience and corporate governance as more general aspects, but also individual responsibility and supervision (which are related to action controls), remuneration systems (which constitute results controls) as well as training, recruitment and knowledgeable leaders (which are components of personnel controls) (Bott & Milkau, 2018 ; Cordery, 2007 ; Drennan, 2004 ; Drummond, 2002 ; Gontarek, 2016 ; Jackson, 2015 ; McConnell, 2013 ; Srivastav & Hagendorff, 2016 ; Wood & Lewis, 2018 ). Young ( 2011 ) adds the concept of high-reliability organizations to the discussion. They offer the possibility to establish more stable banks in terms of risk taking due to high levels of resilience and responsiveness, exemplary leadership and customer-centric objectives. Fritz-Morgenthal et al. ( 2016 ) and Yusuf et al. ( 2020 ) add to this further insights regarding the positive effects of an adequate risk culture on risk management.

These concepts promote a holistic perspective on risk culture or as Stulz ( 2008 , p. 47) stresses: “If risk is everybody’s business, it is harder for major risks to go undetected and unmanaged.” This view underpins the importance not only of individual management controls in the context of risk culture, but also and especially of the importance of embedding risk culture in an overarching concept for entire management control systems. The following articles add to this perspective further insights.

Cordery ( 2007 , p. 64) elaborates on the severe foreign exchange loss announced by the National Australian Bank in January 2004 and identifies problems applying “behavioural controls, such as supervision and security restrictions, attitudinal controls affecting hiring procedures and corporate cultural development, and accountability controls consisting of budgets, targets, incentives and reporting” as instruments to attenuate dysfunctional behavior in this context. According to the author, particularly, incentive systems motivated dealers to break trading limits and to work around established control systems. Moreover, dealers did not exhibit proper attitudes to behave in an ethical way. Although the bank applied codes of conduct signed by each employee, they were not trained to fill this declaration of intent with life and there was no exchange between the board members to develop systems implementing the declaration in daily business. Furthermore, due to a focus on profit only good news was passed to the top management. Additionally, board members did not have a full understanding of the business model and particularly the risk underlying it. Dellaportas et al. ( 2007 ) discuss the same case study, i.e. the National Australian Bank. They also highlight detrimental effects of incentive systems. Moreover, they stress that management followed a profit-oriented perspective, neglecting ethical aspects and that the organization operated in a bureaucratic manner, where top management focused on processes, documentation and procedure manuals instead of really understanding the issues. This points to dysfunctional communication structures. Furthermore, management also did not take on responsibility, personal and professional attacks were observed towards market risk and internal audit staff by traders and traders were selected only according to their ability to make profits irrespectively of how they achieved them.

Barings Bank is another prominent example of failing to embed a proper risk culture in an overarching set of management controls (Stonham, 1996a , 1996b ). Drennan ( 2004 ) particularly points to missing personnel and action controls in this context. The author provides evidence that the recruitment of extreme risk takers in reaction to the de-regulation of the UK financial services market and dysfunctional supervision processes allowed Nick Leeson, a trader on the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX), to continue fraudulent activities. He was not only Chief Trader but also Head of Settlements. Moreover, his local supervisor did not monitor him and his manager in London left the monitoring to the local supervisor. Drummond ( 2002 ) adds to the discussion that Leeson’s supervisors were not knowledgeable enough to supervise his activities and operated in a state of “groupthink”. Stein ( 2000 ) discusses the case of Barings Bank from a psychoanalytical point of view. He also identifies the deregulation of the UK banking sector as one major factor that enhanced the dysfunctional structures, which allowed Leeson to act without proper supervision.

Lehman Brothers constitutes a third example of failure, which is explicitly discussed in extant literature. Based on Schein’s ( 2010 ) organizational culture framework Ganon et al. ( 2017 ) identify the behavior of Richard Fulder, the final CEO of Lehman Brothers, and the culture installed by him as major drivers for the bank’s collapse, i.e. in this context the authors particularly stress the absence of proper personnel and cultural controls.

Literature dealing with the reasons behind the last financial crisis as well points to missing relations between risk culture and other management controls. Jackson ( 2015 ) highlights (among other aspects) inadequate incentives, poor information flows, poor leadership and no clear accountability as reasons for inadequate risk taking resulting in the financial crisis. Furlong et al. ( 2017 ) argue that misconduct, which also led to the financial crisis in 2007/2008, is rooted in poor judgements resulting from underdeveloped character dimensions and organizational culture which does not mitigate them. Thus, the authors focus on both personnel and cultural controls. They explicitly stress that poor conduct not only is an ethical or moral issue. This perspective has the advantage that “[v]iewing misconduct as a judgement issue instead of a moral issue engages audiences who want to improve decision-making but without the judging that is typically associated with moral agendas. Discussions can be had more dispassionately and rationally, and the audience does not feel themselves under attack” (Furlong et al., 2017 , p. 208). The authors develop a Leader Character Framework that comprises those characteristics relevant for leaders to behave adequately. Hashagen et al. ( 2009 ) present a study with more than 400 participants (senior managers involved in risk management of banks) carried out by KPMG and the Economist Intelligence Unit. The participants were asked to name the weaknesses in risk management in banks that fostered the recent financial crisis and the measures that banks take to prevent such a crisis from occurring again. The participants stress the importance of risk culture and highlight the relevance of senior managers’ leadership to implement a prudent risk culture, i.e. 77% of the participants stress tone from the top as one important issue to develop an appropriate risk culture. Also, proper remuneration and a strengthening of risk professionals’ role is mentioned. However, as many as 45% of the banks surveyed also admit that their management boards do not have sufficient knowledge about risks.

4.2.2 Risk culture and cultural controls

The present section is dedicated to the relation between risk culture and banks’ overarching cultural controls. Rad ( 2016 ) provides a particular perspective on this issue. The author focuses on the interplay between risk management and management control systems. Thus, he does not refer to risk culture, but rather to a concept which is related to it. However, by drawing on Simons’ Levers of Control Framework to analyze this relation in two case studies, he identifies belief systems to be of high relevance in this context. Thus, although he does not focus on risk culture in particular, his analysis stresses the importance of cultural components, when analyzing the relation between risk management and management controls. Similarly, Stulz ( 2016 ) highlights culture as an important factor to mitigate the limitations of risk management.

While risk culture as such is by definition one component of cultural controls, it is also related to other aspects linked to this control type. One important aspect in this context are ethical issues . For example, Lui ( 2015 ) investigates five British banks and finds evidence that these banks have undergone a transformation from a customer-driven culture to a sales-oriented culture, which resulted in a greedy, reckless and dishonest behavior. Llewellyn ( 2014 ) discusses detrimental effects of banks’ culture in the context of the last financial crisis. The author does not explicitly state risk culture, but rather refers to banks’ culture in general and their effect on consumers. Nevertheless, it is clear from this discussion that risks relating to financial products must be clearly recognizable to customers in order to maintain a lasting basis of trust. In addition, he sees the establishment of cooperative banks as an opportunity to establish prudent risk behavior. Consequently, ethical behavior in terms of consumer-oriented and sustainable decision making can be related to prudent risk taking, which in turn is related to an adequate risk culture that mitigates systemic collapses of financial systems. Accordingly, Minto ( 2016 ) discusses the specific values of cooperative banks as reasons for these banks to cope much better with the financial crisis in 2007/2008 than commercial banks. The author specifically highlights trust and reciprocity, solidarity, mutualism, proximity and “relationship banking” via local presence, heterogeneity through member ownership as well as social commitment and the “cooperative spirit”. In their conceptual paper, also Awrey et al. ( 2013 ) debate how to achieve a more ethical culture in the financial service industry. According to them, especially process-oriented regulation “backed by a credible threat of both public enforcement and reputational sanctions” (Awrey et al., 2013 , p. 191) can help to establish a more ethical organizational culture in banks by reshaping individual ethical choices. Thus, they argue for stronger regulation and societal sanctioning via reputational losses in case of unethical behavior. Complementary to this discussion, Fichter ( 2018 ) elaborates on how ethical issues are solved in the daily decision processes within the financial industry and provides several suggestions for how financial institutions can translate formal ethical standards into decision making practice. The author stresses challenging authority, creating opportunities for discourse, valuing positive emotion or making time for reflection. Overall, this literature stresses the link between prudent risk raking, (risk) culture and ethical decision making. Thus, for a risk culture to be effective in terms of the overall financial system and to help to prevent systemic collapses, it must be embedded in an overarching cultural context of the bank that follows clear ethical standards.

Another component of cultural controls is the organizational handling of failure . In this context, Gendron et al. ( 2016 ) add to the discussion a perspective on stabilizing processes, which restore risk management credibility after failures and thereby inhibit a fundamental change in approaching risk management in banks. The authors find that failure of risk management is attributed to external factors like implementation failures rather than to failures within the core ideas behind the implemented instruments. Thus, a particular culture of handling failure can affect or inhibit the development of risk culture, in terms of how to manage risks reasonably, into an appropriate direction.

Other scholars focus more on the antecedents and components of risk culture . They particularly discuss the relation between values, norms and risk culture. Lo ( 2016 ) mention different sources of such values . They can be derived top-down (through leadership and authority) and bottom-up (merging form individual behavior) and they are influenced by incentives and environmental factors. By applying Schein’s model of organizational culture Kane ( 2016 ) identifies particular norms in financial institutions and central banks, which foster destructive risk taking. The author argues for a fundamental change of norms within this industry, as the implementation of mechanisms just to constrain the resulting behavior will not effectively mitigate it. In line with this argumentation, Cohn et al. ( 2017 ) expected that professional norms in the financial industry in combination with the salience of the staff’s professional identity foster risk taking. However, in an experimental setting with 128 employees of a large, international bank they find evidence that participants took fewer risks. The authors conclude that their results “contradict the conventional thinking that the professional norms in the banking industry make the employees in that industry less risk averse” (Cohn et al., 2017 , p. 3803). However, this finding has to be put in a broader perspective. The identification of an adequate risk culture for a particular bank does not mean that the bank has to become risk averse, but instead the risk culture has to fit to the bank’s business model and to induce in this sense prudent risk taking. In this context, further findings by Cohn et al. ( 2014 ) are more informative, as the authors find evidence, that the salience of bankers’ professional identity fosters their dishonest behavior, which points to a fundamental problem when establishing an adequate risk culture, as according to the previous discussion such a culture depends on transparent, responsible and honest behavior.

Further scholars consider different manifestations of risk culture to be the condensate of the mentioned values and norms: In order to analyze, whether the growing and in literature criticized focus on quantitative risk management is inevitable, Mikes ( 2009 ) discusses two different risk cultures. Mikes ( 2011 ) further elaborates on these different manifestations and investigates the perspectives on risk measurement within two case studies and 53 further interviews with risk management staff in the period of 2001 to 2010. Some organizations have a culture of quantitative enthusiasm , i.e. they believe in the power of risk measurement, while others follow a culture of quantitative skepticism , which results in risk envisionment by providing alternative future scenarios. The two cultures lead to different behavior of risk officers and their boundary work. A culture of quantitative enthusiasm fosters risk control through the implementation of measurement instruments and the emphasis of independent and scientific risk control. In contrast, in a culture of calculative skepticism, “controllers in this camp lacked the analytical mystique wielded by those with quantitative enthusiasm and they appeared to have deliberately left the boundaries between themselves and the rest of the organization blurred and porous in order to influence decision makers in the business lines” (Mikes, 2011 , p. 241). Lim et al. ( 2017 ) add to this further evidence. Based on qualitative data, they argue that banks are confronted with “a core paradox of market versus regulatory demands and an accompanying variety of performance, learning and belonging paradoxes” (Lim et al., 2017 , p. 75), which are so far resolved by inappropriate measures, as a power imbalance between front and back office remains. The authors suggest that this problem only can be resolved if risk management is less defined by normative, standard based rules but considers a behavioral dimension. Thus, they argue for a shift from quantitative enthusiasm to quantitative skepticism. Stulz ( 2015 ) also contrasts a behavioral perspective with a statistical, calculative orientation in risk management. The author states that “it’s important to keep in mind that companies in the financial industry differ considerably from non-financial firms in the extent to which employees are empowered to make decisions that affect risk” (Stulz, 2015 , p. 16) and stresses adequate risk culture as a way to increase flexibility which is mitigated by statistical risk management. Based on the notion that the application of quantitative models increases the perception of decreasing uncertainty and increasing manageability of risk, LaBriola ( 2019 ) analyzes a possible positive relation between the relative level (1) of securities and (2) of trading securities and levels of leverage. The data (bank-years for large U.S. commercial banks over the period of 1996 to 2016) supports the second hypothesis, whereas it does not lend any support to the first one. However, the support of the second hypothesis does not indicate that actually the application of quantitative models as such results in imprudent risk taking, as the author does not test this relation. Yet, the results point to a possible relation, which again favors calculative skepticism over quantitative enthusiasm. Based on the Competing Value Framework, which comprises the four corporate culture dimensions compete, create, control and collaborate (cf. Sect. 4.1 ) developed by Quinn and Rohrbaugh ( 1983 ), Nguyen et al. ( 2019 ) add to these results by differentiating two foci of risk culture: compete and create cultures are related to a growth focus, while collaborate and control cultures pertain a safety focus. The authors find that banks following the earlier focus incur greater loan losses than banks applying the later focus. In sum, besides categorizing risk culture into different categories the mentioned authors also evaluate the identified types. Risk cultures stressing on collaboration, trust, solidarity and a healthy critical distance to mathematical risk management approaches seem to be favored over competitive, aggressive and quantitatively enthusiastic cultures, as the former result in more resilient banks.

Additionally, scholars find evidence that the conceptualization of an adequate risk culture might vary between organizational units within one single bank depending on the units’ tasks: Based on semi-structured interviews Wahlström ( 2009 ) finds differences with respect to the acceptance of the approaches of risk measurement by Basel II between the operational staff and staff working with risk measurement. The author explains this observation with differences in the frames of reference, which can be interpreted as parts of the risk culture prevailing within each unit. While such differences can result in conflicts, Bruce ( 2014 ) provides evidence that different perspectives on risk culture within one bank also can be advantageous. The author presents four worldviews, which can be interpreted as antecedents of risk culture and which result from a combination between grid and group: Grid refers to the extent to which the social context expects people to behave in a particular way dependent on their role, i.e. the military is a high grid-context, as the hierarchical position clearly determines how a person can act. In contrast, “[g]roup measures both how strongly an individual associates with the organization or collective, and how strongly the organization or collective exerts influence over the individual” (Bruce, 2014 , p. 552). Each dimension can have two levels (high and low). Therefore, the combination of the dimensions results in four worldviews, which in turn guide human behavior differently and, thus, also the interpretation of the reasons behind the recent financial crisis. Based on this analysis, the author argues that diversity and the joint incorporation of different worldviews can improve risk management. Consequently, the implementation of an adequate risk culture that fits the selected business model also comprises the acceptance of different worldviews.

National culture constitutes another source of norm-based influence. It forms part of cultural controls, but it is less changeable by firms as such. It rather constitutes a pre-set condition, in which other cultural controls are embedded. Scholars actually find evidence that it exerts an important impact on banks’ risk taking. For example, based on a sample of 65 to 70 countries in the period of 2000 to 2006, Kanagaretnam et al. ( 2014 ) find lower risk taking in banks in low individualism and high uncertainty avoidance cultures. Similarly, in a sample of 75 countries Ashraf et al. ( 2016 ) observe that cultures characterized by high individualism and low uncertainty avoidance (as well as low power distance) foster risk taking in banks. Findings by Mihet ( 2013 ) support this evidence regarding a positive relation between high individualism and risk taking. Mourouzidou-Damtsa et al. ( 2019 ) as well observe this relation, but not for globally operating banks. In contrast, in a global sample of 467 commercial listed banks from 56 countries, Illiashenko and Laidroo ( 2020 ) find evidence of a negative relation between individualism and banks’ risk taking. The authors explain this observation by the cushioning hypothesis, i.e. decision makers in collectivist cultures receive more support if they make a mistake and are therefore more willing to take risks. Kanagaretnam et al. ( 2019 ) add to these observations evidence of a relation between societal trust and banks’ risk taking: Banks located in high-trust countries exhibit lower levels of risk taking than banks located in low-trust countries. The authors further provide first evidence that this attenuating effect is channeled via greater accounting transparency, higher scores in social CSR and lower CEO equity incentive compensation, i.e. in the study societal trust is related to these aspects in the mentioned direction and they attenuate imprudent risk taking. In sum, these results suggest that the basic attitudes towards risk behavior within a national culture have an important impact on banks’ risk taking and thus supplement and influence the risk culture of a particular bank.

Finally, also different stakeholders can exert an impact on risk culture, because they can have more or less influence depending on their position of power by communicating corresponding expectations and setting certain regulatory standards. Also in this context only some scholars explicitly discuss risk culture, while others rather provide indirect insights with respect to risk culture, as they focus on risk taking. However, as risk taking also is an expression of the prevailing risk culture and the investigated stakeholders have the power to set norms and values and thereby to transport their worldview into the banks and to influence the manifestation of cultural controls, we consider also this part of literature as insightful for the present topic. Several scholars focus on the impact of regulators on risk culture as particularly powerful stakeholders (Cohen, 2015 ; Mongiardino & Plath, 2010 ; Rattaggi, 2017 ; Walter & Narring, 2020 ). For example, Schnatterly et al. ( 2019 ) investigate the implications of the selection of one of three possible regulators by the initial board of directors within new U.S. banks for the banks’ future risk taking. Their results point to a joint effect of board independence and the selected regulator on the banks’ risk. The analysis is based on a sample of 140 new banks from the population of 1,367 U.S. banks chartered between 1992 and 1998. Carretta et al. ( 2017 ) observe differences between national supervisors’ conceptualization of risk culture as well as their substantial distance to the ECB’s risk culture in the period of 1999 to 2012. These differences complicate the development of an adequate risk culture within European banks, particularly the ones that operate internationally, because they are confronted with different requirements. Sinha and Arena ( 2018 ) investigate the viewpoints of regulators as well as normalizers, consultants, and implementers on risk culture. Their sample consists of 20 interviews and 295 documents. They find two distinct interpretations. While the first interpretation concentrates on the control of risk culture via verification, the second interpretation focuses on the control of risk culture through internal audits and the empowerment of employees through training. Regulators and implementers promote the first interpretation, while consultants and normalizers foster the second one. In order to fully satisfy the different stakeholders’ demands, banks have to set up a process, which discloses these viewpoints and integrates them into a comprehensive approach related to the management of risk culture.