- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Faith, Power, and Survival: What Ruled Life in Early-Medieval England

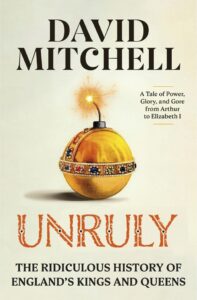

David mitchell considers the less-than-illustrious origins of the english crown.

For me, the misty, dark, unknowable aura of fifth-, sixth- and seventh-century Britain is an enormous draw. Murkiness with a fleeting glimpse of gold. A crown, a sword, a hoard of Roman coins buried by a rich Romano-Briton fleeing his villa in panic…

What was that movement in the fog? A dragon, a dinosaur, a galley full of legionaries hurrying away? The sense of mystery and loss is overwhelming, long before anyone thought of inventing King Arthur.

Hwaer cwom mearg? Hwaer cwom mago?

That’s the Anglo-Saxon language, also known as Old English. It contains hardly any words inherited from Brittonic, which suggests there was eerily little cordial interaction between the Anglo-Saxons and the people they displaced. It’s a snippet from a poem called “The Wanderer” that’s preserved in a tenth-century manuscript but is believed to have been written much earlier. It’s from a bit that translates as this:

Where is that horse now? Where the rider? Where is the hoard-sharer?

Where is the house of the feast? Where is the hall’s uproar?

There’s a powerful sense of missing something, which is a strangely sophisticated emotion to have been preserved for us from what, in our terms, seems like such a primitive and poorly documented culture. Longing and bereavement are surprisingly high in the mix, compared to, say, glory or sex or anger. From our perspective, this little medieval society is barely getting started and yet it’s already steeped in as much moist-eyed nostalgia as last orders at a British Legion club on the anniversary of VE Day.

“The work of giants is decaying,” laments another poem, “The Ruin.” It’s reflecting on some crumbling Roman buildings, probably those in Bath. “Bright were the castle buildings, many the bathing-halls, / high the abundance of gables, great the noise of the multitude, / many a meadhall full of festivity, / until Fate the mighty changed that.”

“A meadhall full of festivity” sounds a bit downmarket for a Roman night out, and the reference to “castle buildings” is poignant. Magnificent though they are, the buildings aren’t fortified. They didn’t need to be for most of Roman rule. The Romans established reliable public order, a feat not achieved again in Britain for well over a thousand years. This was a luxury the Anglo-Saxons couldn’t imagine.

Still, the point is well made. I suppose it’s hard to live amid so much decaying infrastructure without feeling a bit glum.

The good news

Some people managed it, though. King Ceolwulf of Northumbria, for example, and his favorite historian, the Venerable Bede. They lived in the late seventh and early eighth centuries and they’re quite upbeat about life. Plus they definitely existed. You can take that as read from now on. The mists of time have lifted considerably.

Bede is one of the main mist-lifters. He was a monk in the abbey of Jarrow in Northumbria and his Ecclesiastical History of the English People was the most famous thing to come out of Jarrow until a march protesting against unemployment in 1936. Bede’s book predates the march by a cool 1,205 years and is one of the main reasons we know anything at all about Dark Age England. He dedicated it to the King of Northumbria at the time, Ceolwulf.

Bede and Ceolwulf are also both saints. I don’t disapprove of Ceolwulf ’s kingly sainthood as much as Edward the Confessor’s, because he abdicated in 737 and lived as a monk for the rest of his life, so he put the hours in sanctity-wise. As did Bede, though the soubriquet Venerable seems to have stuck to him despite achieving higher-ranking saintly status. These things happen. People never really said “Admiral Kirk.”

I have genuinely literally read Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People . So you don’t have to. I’d take me up on that if I were you—it may be important but it’s boring. It was written in Latin but an English translation was on the reading list I was given before going to university, so I gave it a go.

In my nineteen-year-old arrogance, what I felt was silly about Bede was that he characterized an age of comparative barbarism and misery as one in which humanity had advanced. He only did this, ridiculously it seemed to me then, because it was a good period for the church, an institution with which he was obsessed. In England, for the hundred years or so before he wrote his history, Christianity had been on the march. That’s why Bede didn’t see the situation in the same bleak terms as whoever wrote “The Wanderer” and “The Ruin.” I felt he was just plain wrong.

Looking back, I realize I was a bit hard on him. Religion both bored and unsettled me, and yet my history teachers were constantly exhorting me not to ignore it. In an A-Level history essay, I was taught, there should always be at least one paragraph on the church. I would dutifully stick one in but I didn’t really get it. I was an agnostic who didn’t like thinking about religion because I hoped there was a God but didn’t have the confidence to commit. Plus the trappings of religion felt a bit embarrassing and weird, like properly putting on a French accent when saying things in French.

My religious views haven’t significantly moved on, but what I am slightly more capable of understanding is that, the existence or non-existence of God notwithstanding, religion is real and powerful and not just something from the olden days. Moreover, in the olden days, it was, in pretty much every society, a bigger deal than we can possibly imagine.

Christianity, for Bede, wasn’t merely something he was massively into, or he solemnly exhorted other people to adhere to, it was everything . It was the real underlying truth of existence, like science is today. It was very much not like religion is today, even for those who are very religious. If we don’t accept that, we can’t begin to understand the times he lived in and the attitude he took.

So, for him, a history of England that wasn’t entirely focused on the spread of the Christian faith would be pointless, because nothing else mattered. This was a prevalent view at the time and one that gave a brutal existence meaning, purpose and hope. I’m thirty years nearer the grave than when I first read Bede and much less confident in rejecting this worldview.

The bad news

The Romans had been Christian by the end. Originally they’d been polytheistic and inclined to use Christians as lion food, but in 313 the Emperor Constantine put a stop to all that and declared he was a Christian himself. Soon Christianity was the empire’s dominant religion, which meant that the Romano-British were Christian—hence King Arthur was Christian, even though he didn’t exist. Over on the continent, Roman rule may not have survived but Roman religion did. Tribes like the Goths and the Franks were content to live in Roman cities and were soon worshipping the Romans’ lovely big single God. Despite repeatedly sacking Rome itself, these upwardly mobile barbarians were keen to live an increasingly Roman life. It was as if they were collectively willing into existence the expression “When in Rome.”

It was different in Britain. The invading Anglo-Saxons weren’t interested in Jesus or a free limoncello . The Britons were driven west, some remaining Christian and some reverting to a sort of iron age paganism, cities were abandoned and the newcomers settled down to a rural existence throughout the south-east of the island, hurling the occasional Roman brick at one another.

The Anglo-Saxons stuck with the form of paganism they’d brought over from the continent, which was a nice little bunch of gods who, as a helpful mnemonic, the days of the week are named after. There’s Woden, king of the gods and god of wisdom—beardy guy with a cloak—after whom Wednesday is named. Then Thunor, their version of Thor, who you might know from the Marvel Universe. He’s god of thunder, which feels like a comparatively small brief, and the etymological root of Thursday.

Then it’s Frigg. I don’t know if the 1970s expression for wanking derives from this goddess’s name—though it seems unlikely as her portfolio includes marriage and childbirth—but the word Friday definitely does and I think we can all agree that the end of the working week is a lovely time for a jolly good frigg. The god of war, Tiw, accounts for Tuesday. Sunday and Monday are the sun and the moon and, weirdly, Saturday is named after the Roman god Saturn, which feels incongruous—a bit like having a parish church called St Mohammed’s.

Back to the mortals: whatever the actual names of those early Anglo-Saxon big shots, it seems unlikely that any of them were kings in the sense we understand the word. What probably happened is that the new settlers appropriated areas of land and then, people being reliably unpleasant, some of those settlers would start pushing others around, demanding “tribute” and offering “protection.” Gradually, by the same method used by drug gangs to divide up LA, a system of government emerged.

The local hard guy had to stay in with the provincial hard guy who had to curry favor with the regional hard guy. It was out of this unjust and lawless maelstrom of violence that the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms coalesced. The kingly legitimacy affected by the relatively settled handful of rulers and regimes that were in existence by Bede’s day is no more respectable than a mafia boss adopting the title “Don.”

It’s just dressing up a system based on violence in order to economize on violence. If you can get people to start calling you “sire” and obeying you because they think that’s the way of the world, or somehow right and proper and endorsed by God or the gods, then you don’t have to raise so many bands of heavies or armies and incur all the risks and costs involved in asserting your supposed royalty at the point of a sword or knuckle.

In case this isn’t sounding grim enough, in the 530s–550s there was a period of extreme cold weather, famine and plague. A series of volcanic eruptions in (what is now) Iceland threw up dust clouds that blocked the sun and made the crops fail all over Europe. Outbreaks of plague followed, probably because everyone who hadn’t starved to death was hungry and cold and sad. All this suffering must have hastened the process by which power was consolidated into fewer and nastier hands. Many desperate people will have accepted the protection offered by anyone tough with a bit of spare food.

The true roots of English kingship are therefore so far away from the Arthurian ideal it’s actually funny. The notion that pious legitimacy was the foundation of the institution is totally false. Everything those early kings possessed they, or their ancestors, had either stolen or demanded with menaces.

The veneer of legitimacy was retrospectively applied in order to keep hold of all the power and wealth.

By the late sixth century and early seventh, pretending to be a king was all the rage. The vague regions of strongman influence started to coalesce into kingdoms and the idea of a bretwalda emerged. The bretwalda, which literally means either “wide-ruler” or “Britain-ruler,” was supposedly the dominant Anglo-Saxon king at any given time. We don’t know if the term was used contemporaneously—it may be a ninth-century invention—but the notion of being a dominant ruler must have been understood. It would have been the gold medal in the Olympics of unpleasantness that these violent men were competing in.

Rulers’ status was all about power deriving from violence, combined with a growing sense that a bit of regal showiness helped keep inferiors in their place and intimidate rival kings. So they energetically asserted their importance in other ways. That’s what the elaborate burial at Sutton Hoo was all about. They also built huge wooden halls, full of booze and smoke and warriors. As you can imagine, they burned down, or were burned down, with tedious regularity, but they were major symbols of the new kings’ power.

A king could put a roof over your head, at least for a few hours, and keep you warm and fill your stomach. In those bleak days, that was all it took. Rather poignantly, the modern English word “lord” derives from the Old English hlaford meaning “bread-giver.” In Roman times, there’d been circuses too.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Unruly: The Ridiculous History of England’s Kings and Queens by David Mitchell . Copyright © 2023 . Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

David Mitchell

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Insomnia, Imposter Syndrome, and All the Ways I Learned to Write My Book

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Please enable JavaScript in your web browser to get the best experience.

You are here:

- Library & Digital

- Collections

Medieval History Collections

Find out more about the extensive Medieval History Collections in the IHR Wohl Library. We collect historical sources, reference works and guides to finding and using sources. This page shows examples from the collections.

- Share page on Twitter

- Share page on Facebook

- Share page on LinkedIn

Introduction

The collections on medieval history are one of the strengths of the IHR library. The collections focus on editions of primary sources, alongside complementary aids to study such as reference works, guides and historiography.

There are sections on medieval history across the library. Collections are both geographically-arranged (for example within the French collection, works on Medieval France are at classmark EF.2) and thematically-arranged (for example Medieval Military history at W.41). The local and regional history sections (e.g., ENL Low Countries, ESR Spain) also contain particularly rich sources on medieval history. Material is collected both in language of origin and translations, and language dictionaries and guides are available. Online resources are included within the relevant sections of this guide and as a separate section at the end.

For the purposes of this guide, we are using an end date of around 1500 varying from region to region based on political changes and dynasties. There is a complementary guide covering Early modern history [to link here]. This guide is arranged in three sections: Primary sources with subsections on types of source, Selected themes such as Medieval Women and Travel writing and Secondary Works including bibliographies, guides and historiography.

The collections are complemented by material at Senate House Library and the Warburg Institute Library . For the very early middle ages readers will also find useful material in the Institute of Classical Studies Library which covers late antiquity.

Image credit: "a miniature depicting a family by the Seder table with the master of the house placing the basket of unleavened bread on the head of one of his children", from British Library Additional 14761 f. 28v , Spain c. 1340.

Finding within the Library

Collection arrangement.

Collections within the library each have a letter, followed by a numerical sequence (decimal numbers are used, arranged as if after a decimal point, so for example ER.53 comes after ER.504). Each national collection has a sequence of local and regional material following the general sequence. The main areas with medieval sections and the corresponding classmarks are as follows:

- Austria (to 1556): EA.291

- Britain and England : General sections with medieval material: B.0 Bibliographies/guides, B.2 Biography, B.3-4 Law and Parliament, B.5 England to 1485, BC English local history

- Byzantium : EV

- Crusades : EU

- France ( to 1483): EF.2

- General history : E.1 Historiography and Methodology, E.2 Reference works, E.41-46 Carolingian and Holy Roman Empire, E.6 Sources and Secondary works Medieval

- Germany to 1517: EG.2

- Italy to c. 1494: EI.2

- Ireland to 1540: BI.4

- Jewish history : EY.092 and EY.2

- Low Countries to 1555 : EN.31-37

- Mediterranean world : EM

- Military : W.41 History of Naval and Military operations Ancient and Medieval

- Portugal to 1580: EP.2

- Religious history : ER. Includes sections on Patristics ER.2, Saints and Hagiography ER.4, Theology ER.4, Papacy: ER.5, Medieval Papacy ER.504, Papal Letter and Registers ER.53, Monasticism ER.6-7, Aspects of Religious life: liturgy, pilgrimage, Heresy and the Inquisition ER.8. Source material on religious establishments is also found in the relevant national collections.

- Scandinavia : ED arranged by country

- Scotland : BS.2 to 1542

- Spain to 1516: ES.2

- Wales to 1536: BW.2

Further Help

Contact us if you would like help on finding or using our collections, or if you have any comments or suggestions about the content of this guide. We are happy to help.

You can also join the library and book a help session .

Highlights from the Collections: Primary Sources

General collections of sources.

Included here are some freely available online collections as well as print editions. Examples are:

- English Historical Documents

- Oxford Medieval Texts

- British History Online (mostly free and access to subscription content within library)

- Internet medieval sourcebook (online)

- EuroDocs: Online Sources for European History (online)

- Monumenta Germaniae Historica shelved at classmark EGM, organized by series. Further information can be found on the MGH guide .

- Collection de documents inédits sur l’histoire de France.

- Deutsches Archiv für Geschichte des Mittelalters

- Fonti per la storia d’italia

- Regesta Imperii and online version

- Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France

- Rerum Italicarum scriptores

- Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de España

- Textos medievales

Church Records

Examples are:

- Patrologia Latina print and electronic

- Acta Sanctorum print and electronic

- Corpus Christianorum

- Regesta pontificum Romanorum

- Papal Letters, various editions including Ut per litteras apostolicas

- English episcopal acta

- Papsturkunden in Frankreich : Neue Folge

- York's Archbishops Registers Revealed (online) Free access to over 20,000 images of Registers produced by the Archbishops of York, 1225-1650

- Rolls Series Rerum Britannicarum Medii Aevi Scriptores

- Annals of Ulster

- Chroniken der deutschen städte vom 14. bis in's 16. Jahrhundert

- Les grandes chroniques de France

- Collection de chroniques belges inédites

- Colección de crónicas españolas

British and Irish Law and Government

- Statutes of the Realm

- Parliament Rolls of Medieval England

- Inquisitions post mortem

- Calendar of the charter rolls . Further information

- Calendar of Close Rolls . Further information

- Calendar of the Patent Rolls . Further information: National Archives website ; IHR blog post

- Calendar of the Fine Rolls and Henry III Fine Rolls Project

- Selden Society Publications

- Curia Regis rolls

- The acts of Welsh rulers 1120-1283

- Regesta Regum Scottorum

- Register of Edward, the Black Prince

- Giraldi Cambrensis Opera

- English Medieval Legal Documents Database (online)

Charters and other Landholding Sources

Some examples:

- Domesday: Various editions including Alecto edition of Domesday book and Exon: The Domesday Survey of South-West England (online)

- Anglo Saxon charters

- Early Yorkshire charters

- The Electronic Sawyer: Online catalogue of Anglo-Saxon charters (online)

- Scripta: Database of Norman Medieval documents "a large corpus of medieval norman charters dating from the 10th to the 13th Century" (online)

- El llibre de privilegis de Castelló de la Plana, 1245-1470

- Diplomatarium islandicum

- Urkunden und Regesten zur Geschichte des Templerordens im Bereich des Bistums Cammin und der Kirchenprovinz Gnesen

The collections include editions of letters, both of individuals and compilations. There are also some secondary works about medieval letter-writing. Examples include:

- Letters of medieval Jewish traders

- Lost letters of medieval life : English society, 1200-1250

- Christ church letters : A volume of mediaeval letters relating to the affairs of the priory of Christ church Canterbury

- Calendar of the letters of Arnaud Aubert, Camerarius Apostolicus 1361-1371

- Calendar of letters from the Mayor and Corporation of the City of London, circa A.D.1350-1370

- The Cely letters, 1472-1488

- Epistolari de la València medieval

- The letter collections of Nicholas of Clairvaux

- The letters of the queens of England, 1066-1547

- The letters and poems of Fulbert of Chartres

- The letters of Catherine of Siena

- Letters of Margaret of Anjou

- Merovingian letters and letter writers

- Paston letters and papers of the fifteenth century

- The Plumpton letters and papers

- The letters of the Rožmberk sisters : noblewomen in fifteenth-century Bohemia

- Epistolae: Medieval Women's Letters (online)

Local and Regional History

These are a rich source of medieval history. Examples include:

- Business contracts of medieval Provence : selected notulae from the cartulary of Giraud Amalric of Marseilles, 1248

- Medieval Bruges, c. 850-1550

- De Oorkonden van de Sint-Baafsabdij te Gent (819-1321)

- Zwolse regesten

- De heren van de kerk : de kanunniken van Oudmunster te Utrecht in de late middeleeuwen

- Victoria County History . Full text of many of the volumes available on British History Online .

- The court rolls of the Manor of Wakefield : from September 1348 to September 1350

- Calendar of Antrobus deeds before 1625

- Surveys of the estates of Glastonbury Abbey, c. 1135-1201

Place-names

The library collections include place name reference works which document place-names and allow their origins to be traced. Some examples:

- English Place-Name Society volumes

- Key to English Place-Names (online)

- Toponymie générale de la France : etymologie de 35,000 noms de lieux

- Diccionario de topónimos españoles y sus gentilicios

- De Vlaamse waternamen : verklarend en geïllustreerd woordenboek

Military History

This includes items in the main miltary section W.41 and also in the crusades section EU

- Medieval warfare sourcebook

- Encyclopedia of the hundred years war

- Records of the medieval sword

- Anglo Norman warfare

- The Battle of Hastings : sources and interpretations

- Alfred's wars : sources and interpretations of Anglo-Saxon warfare in the Viking age

- Baldric of Bourgueil 'History of the Jerusalemites' : a translation of the 'Historia Ierosolimitana'

- Bayeux Tapestry (online)

Highlights from the Collection: Secondary Works

Bibliographies, catalogues, guides.

Ranging from general to subject specific they are a good way of locating publications and learning more about how to use sources. Each section of the library has sections for bibliographies and guides to sources near the beginning.

- International Medieval Bibliography

- Bibliography of British and Irish History

- Medieval Cartularies of Great Britain and Ireland

- Makers and users of medieval books : essays in honour of A. S. G. Edwards

- Literature of the crusades

- Corpus catalogorum Belgii : the medieval booklists of the southern Low Countries

- Understanding medieval primary sources : using historical sources to discover medieval Europe

- Introduction aux sources de l'histoire médiévale

- Ruling the script in the middle ages : formal apsects of written communication (books, charters, and inscriptions)

- Le catalogue médiéval de l'abbaye cistercienne de Clairmarais et les manuscrits conservés

- A critical companion to English 'Mappae Mundi' of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries

- L'atelier du médiéviste

- Archives Portal Europe (online)

Biographical Works

Most of the library’s sections include biographical listings, both general resources such as National Biographical dictionaries, and themed listings such as by trade, religious office holders or listings of aristocratic households. Examples are:

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (both print and online )

- Dictionary of Welsh Biography (online)

- Dizionario biografico degli Italiani

- Neue Deutsche Biographie

- Who's who in the Middle Ages

- Extraordinary women of the medieval and Renaissance world : a biographical dictionary

- An annotated index of medieval women

- History of Parliament 1386-1421 and online

- Religious office holders, e.g. Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae , The heads of religious houses, England and Wales

- Registers of students within histories of universities, see Culture and Learning section .

- Dictionnaire des sculpteurs français du Moyen Age

- The Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (online)

- England’s Immigrants 1330-1550 (online)

- A handlist of the Latin writers of Great Britain and Ireland before 1540

The collections also include some biographies of individuals e.g. B.58 British collection

Dictionaries and Reference Works

Within the library, dictionaries are available at the beginning of the general and other sections. Online versions of medieval language dictionaries are also listed below.

- Logeion Includes The Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources

- Anglo-Norman Dictionary

- Bosworth-Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

- Middle English Compendium

Reference works and encyclopedias

- Dictionary of the Middle Ages

- Lexikon des Mittelalters print and online

- The new Cambridge medieval history

- A dictionary of medieval terms and phrases

- Medieval France : an encyclopedia

- The encyclopedia of the medieval chronicle

- Encyclopedia of the hundred years war

- Encyclopedia of medieval pilgrimage

- Medieval Ireland : an encyclopedia

- Medieval Iberia : an encyclopedia

- Medieval Jewish civilization : an encyclopedia

- Trade, travel and exploration in the middle ages : an encyclopedia

- The Blackwell encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England

Historiography and Methodology

There are general works at classmark E.1 and subject-specific works within other collections. They range from historiography, methodology, works about individual historians, medievalism and the interpretation of medieval history. Examples are:

- What is medieval history?

- Writing medieval history

- Medievalisms in the postcolonial world : the idea of the "Middle Ages" outside Europe

- The Vikings reimagined : reception, recovery, engagement (on order)

- Chronicling history : chroniclers and historians in medieval and Renaissance Italy

- In their own words : practices of quotation in early medieval history-writing

- Arabische Historiographie der Gegenwart

- Universal chronicles in the high middle ages

- Bede's Historiae : genre, rhetoric and the construction of Anglo-Saxon church history

- A woman in history : Eileen Power, 1889-1940

- Anna Komnene : the life and work of a medieval historian

Secondary Texts

The library doesn’t generally collect secondary material but some works are held where they are considered useful guides to the sources or have source-based appendices. We actively collect Festschriften. A few examples:

- The medieval world / edited by Peter Linehan and Janet L. Nelson

- Freedom of movement in the middle ages : proceedings of the 2003 Harlaxton Symposium

- The Cambridge history of medieval political thought c. 350-c. 1450

- Domesday : book of judgement

- Writing medieval biography, 750-1250 : essays in honour of Professor Frank Barlow

- Album Helen Maud Cam

Periodicals

The most recent years of most of our journals are on open shelves in the Current Periodicals room. Earlier issues can be ordered from the stack. Many are also available online within the building via the links on the catalogue. Bibliography of British and Irish History and JSTOR are examples of the online databases that can be used to locate journal articles. Examples of medieval history periodicals are listed below, but articles will be found across periodicals on many subjects:

- Anglo Norman studies

- Cambrian medieval celtic studies

- Anglo-Saxon England

- Early medieval Europe

- Journal of medieval history

- The journal of medieval military history

- Journal of the Haskins Society : studies in medieval history

- Medieval prosopography

- Fourteenth century England

Selected Themes

Medieval women.

Insights about the lives of medieval women are found within many primary sources across the collections. There are also compilations of sources on the subject, and some secondary works. Finding items in sources require some digging and knowledge of the likely places. Secondary works and collections of sources on the subject can be found using subject and keyword searches on the catalogue. Some examples:

Collections of writings

- The writings of medieval women : an anthology

- Women's lives in medieval Europe : a sourcebook

- Medieval writings on secular women

- The letters of the queens of England, 1066-1547

Individual women or families

- Letters of Margaret of Anjou

- The Paston women : selected letters

- A companion to The book of Margery Kempe

Women and religion

- Guidance for women in twelfth-century convents

- Women's Books of hours in medieval England

- Saints Edith and Æthelthryth : princesses, miracle workers, and their late medieval audience : the Wilton Chronicle and the Wilton Life of St Æthelthryth

- The white nuns : Cistercian abbeys for women in medieval France

- Religious women in medieval East Anglia : history and archaeology c1100-1540

Spaces and objects

- Gender in medieval places, spaces and thresholds (open access)

- Medieval women and their objects

- Dress accessories c.1150 - c.1450

- "For the salvation of my soul": women and wills in medieval and early modern France (online)

- Frauenstimmen in der spätmittelalterlichen Stadt? : Testamente von Frauen aus Lüneburg, Hamburg und Wien als soziale Kommunikation

- The will of Aethelgifu : a tenth century Anglo-Saxon manuscript

Secondary works

- Ale, beer and brewsters in England : women's work in a changing world, 1300-1600

- Motherhood, religion, and society in medieval Europe, 400-1400 : essays presented to Henrietta Leyser

- Popular memory and gender in medieval England : men, women and testimony in the church courts, c.1200-1500

- Medieval Italy, medieval and early modern women : essays in honour of Christine Meek

- Medieval women : texts and contexts in late medieval Britain : essays for Felicity Riddy

- The Welsh law of women : studies presented to Professor Daniel A. Binchy on his eightieth birthday, 3 June 1980

- Queen Emma and Queen Edith : queenship and women's power in eleventh-century England

- Women in the medieval English countryside : gender and household in Brigstock before the plague

Travel Writing

These can be found both within the general travel and exploration sections (classmark C) and within the collections for the place being described. They include textual sources, maps and other trade and travel sources. Examples include:

- A traveller in thirteenth-century Arabia : Ibn al-Mujāwir's Tārīkh al-mustabṣir

- Mandeville’s travels (several editions)

- The voyages of the Venetian brothers, Nicolò & Antonio Zeno, to the northern seas in the XIVth century

- Quellen zur Geschichte des Reisens im Spätmittelalter

- Marco Polo’s Le devisement du monde: Edition and Simon Gaunt’s Marco Polo's Le devisement du monde : narrative voice, language and diversity

- The travels of Ibn Jubayr : a medieval journey from Cordoba to Jerusalem

- Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages : a reader

- Cathay and the way thither : being a collection of medieval notices of China

- Trade, travel and exploration in the middle ages : an encyclopedia

- Historical atlas of the Islamic world

- A critical companion to English 'Mappae Mundi' of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries

- Local maps and plans from medieval England

Clothing and Textiles

Examples include sources on clothing, laws on clothing and the textile trade, archaeological sources and secondary works. There will also be many examples within more general sources. See also the Fashion history guide .

- The medieval clothier

- The right to dress : sumptuary laws in a global perspective, c. 1200-1800

- Cloth and clothing in medieval Europe : essays in memory of Professor E.M. Carus-Wilson

- Advance contracts for the sale of wool, c. 1200-c. 1327

- The Merchant Taylors of York : a history of the crafts and company from the fourteenth to the twentieth century

- Registre des délibérations et ordonnances des marchands merciers de Paris, 1596-1696

- Statuti dell'Arte dei rigattieri e linaioli di Firenze (1296-1340)

- Fleming, R, Acquiring, flaunting and destroying silk in late Anglo-Saxon England in Early Medieval Europe (2007)

Examples of descriptions from within sources:

- Descriptions of the prescribed apparel for Servants, Esquires and Gentlemen, Merchants, Knights, the Clergy and Ploughmen in Statutes of the Realm , 37 Edward III c.8-15 1363

- "A statute was approved during the parliament to prohibit the export of wool, while seeking to encourage the manufacture of cloth in England... No one was to use foreign made cloth, except the king, queen and their children" ( Parliament Rolls of Medieval England , 1337 March, Vol. 4 p.230)

Building and Households

The collection includes both primary sources such as estate and building records and secondary works. See also the separate Architectural History collections guide . Examples are:

Primary sources

- The building accounts of Tattershall castle : 1434-1472

- Building accounts of King Henry III

- Building accounts of All Souls College Oxford, 1438-1443

- London plotted : plans of London buildings c.1450-1720

- The Plan of St. Gall : a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery

- The medieval household : daily living c.1150-c.1450

- Norwich households : the medieval and post-medieval finds from Norwich Survey excavations, 1971-1978

- Household accounts from medieval England. Part 1, Introduction, Glossary, Diet Accounts

Reference and secondary works

- The Pevsner Buildings of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales series

- English mediaeval architects : a biographical dictionary down to 1550

- The elite household in England, 1100-1550 : proceedings of the 2016 Harlaxton Symposium

- Anglo-Saxon architecture

- A gazetteer of medieval houses in Kent

- The medieval peasant house in Midland England

- Scottish abbeys : an introduction to the mediaeval abbeys and priories of Scotland

- Jewish heritage in England : an architectural guide

- The English Mediaeval House

- Greater medieval houses of England and Wales 1300-1500

- The early Norman castles of the British Isles

- Arts of the medieval cathedrals : studies on architecture, stained glass and sculpture in honor of Anne Prache

- Mainz and the middle Rhine Valley : medieval art, architecture and archaeology

Education and Learning

There are sections within individual areas on this theme, also a large collection on the history of universities (including biographical listings) and, within the Religious history collection , works on monasticism and religious orders.

Examples of Histories of universities and alumni listings

- Die Matrikel der Universität Wien

- Die Matrikel der Universität Köln

- Die Matrikel der Universität Heidelberg von 1386 bis 1870

- A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. 1500

- History of the University of Oxford

- A history of the University of Cambridge

- Alumni cantabrigienses: a biographical list of all known students, graduates and holders of office at the University of Cambridge, from the earliest times to 1900 print and online version .

Examples of other works:

- University records and life in the Middle Ages

- The universities of Europe in the Middle Ages

- English schools in the Middle Ages

- Teaching and learning in medieval Europe : essays in honour of Gernot R. Wieland

- The church and learning in later medieval society : essays in honour of R.B. Dobson

- Writing history in the Anglo-Norman world : manuscripts, makers and readers, c. 1066-c. 1250

- Medieval libraries of Great Britain : a list of surviving books

- The Cambridge history of libraries in Britain and Ireland

Food and Drink

There are references to food in many of the primary sources in the collections. Listed below are some examples of secondary works on the subject. See also the Guide to Food History Collections

- Food and eating in medieval Europe

- Food, craft, and status in medieval Winchester : the plant and animal remains from the suburbs and city defences

- The book of Sent Soví : medieval recipes from Catalonia

- Medieval cookery : recipes and history

- A medieval capital and its grain supply : agrarian production and distribution in the London region c.1300

- Medieval masterchef : archaeological and historical perspectives on eastern cuisine and western foodways

- Agrarian history of England and Wales

Online Resources

Subscription online resources are available within the building. See also the medieval section in Open and Free Access Materials for Research . Free online resources are also included in the relevant sections above.

A few examples:

- International Medieval Bibliography

- Acta Sanctorum

- British History Online

- Gatehouse: A comprehensive gazetteer and bibliography of the medieval castles, fortifications and palaces of England, Wales and the Islands

- The Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture

- Historic England Archive

- Dictionary of Medieval Names from European Sources

- The Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- England’s Immigrants 1330-1550

- Logeion includes The Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources

- English place-names

- English medieval coins

- Portable Antiquities Scheme database

Other Collections

- British Library

- National Library of Scotland

- National Library of Wales

- National Archives

- Bodleian Libraries

- Warburg Institute

- Senate House Library

- Institute of Classical Studies

Related Content

European History 1150-1550

Earlier Middle Ages

Interdisciplinary Seminar on Medievalism

The Interdisciplinary Seminar on Medievalism meets regularly to consider imaginings, re-imaginings and evocation of the Middle Ages...

Crusades and the Latin East

Italy 1200-1700

London Society for Medieval Studies

Founded in 1970/1, the London Society for Medieval Studies seeks to foster knowledge of, and dialogue about, the Middle Ages (c.500–c.1500 CE)...

Late Medieval

The Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH)

Find out more about the series Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH) in the IHR Wohl Library

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section English Kings and Monarchy, 1066-1485

Introduction.

- Early Narrative Histories and Essay Collections

- Cambridge and Oxford Narrative Histories

- Other Studies

- Reference Works

- Bibliographies and Handbooks

- Major Primary Source Collections in the Original Languages

- Source Collections in Translation

- Constitutional and Administrative History

- William I “The Conqueror”

- William II “Rufus”

- Richard I “Coeur de Leon”

- John “Lackland” or “Softsword”

- Edward I “Longshanks”

- Richard III

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Alfred the Great

- John Hardyng

- Pope Innocent III

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Chronicles (Anglo-Norman and Continental French)

- Chronicles (East Norse, Rhymed Chronicles)

- Middle English Lyric

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

English Kings and Monarchy, 1066-1485 by Douglas Biggs LAST REVIEWED: 28 January 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 28 January 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396584-0114

The king was the most important component in medieval political society. With him lay the right to rule, and all power flowed from him out to his subjects through a complex array of nobles, churchmen, gentry, and the machinery of government. Without the person of the monarch, governance was all but impossible. Across the roughly four centuries that separate the Norman Conquest from the accession of the Tudors in 1485, English kingship underwent a number of significant changes in response to various constitutional crises and transformations of government, but the core of who and what the king was remained constant. Historians have focused on kings and their power for centuries, and their work on so large a subject is both broad and varied. Significant debates as to the nature of kingship and the application of royal power and a plethora of studies of individual kings and how they shaped the office have led to different understandings of monarchy in this period. This bibliography does not try to provide the reader with an exhaustive list of articles and books on so broad a topic as kingship and monarchy. Rather, it tries to provide only the major works for any particular reign that will probably be found in a college or university library. This bibliography draws attention to works such as Stephenson and Marcham 1937 (cited under Source Collections in Translation ), or Bryce Dale Lyon’s history of administration ( Lyon 1980 , cited under Constitutional and Administrative History ) that might be lingering in dusty retirement on their shelves.

General Overviews

A topic as broad as monarchy and kingship has spawned a great many general overviews and studies. The late 19th century was a period of great narrative histories, when historians covered several reigns in multivolume sets (e.g., Norgate 1887 , Ramsay 1892 , Ramsay 1913 , and Hunt and Poole 1905–1910 ). Both Cambridge University and Oxford University produced multivolume sets of their own, while individuals have also produced single-volume studies.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Medieval Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Aelred of Rievaulx

- Alcuin of York

- Alexander the Great

- Alighieri, Dante

- Ancrene Wisse

- Angevin Dynasty

- Anglo-Norman Realm

- Anglo-Saxon Art

- Anglo-Saxon Law

- Anglo-Saxon Manuscript Illumination

- Anglo-Saxon Metalwork

- Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture

- Apocalypticism, Millennialism, and Messianism

- Archaeology of Southampton

- Armenian Art

- Art and Pilgrimage

- Art in Italy

- Art in the Visigothic Period

- Art of East Anglia

- Art of London and South-East England, Post-Conquest to Mon...

- Arthurian Romance

- Attila And The Huns

- Auchinleck Manuscript, The

- Audelay, John

- Augustodunensis, Honorius

- Bartholomaeus Anglicus

- Benedictines After 1100

- Benoît de Sainte Maure [113]

- Bernard of Clairvaux

- Bernardus Silvestris

- Biblical Apocrypha

- Birgitta of Sweden and the Birgittine Order

- Boccaccio, Giovanni

- Bokenham, Osbern

- Book of Durrow

- Book of Kells

- Bozon, Nicholas

- Byzantine Art

- Byzantine Manuscript Illumination

- Byzantine Monasticism

- Calendars and Time (Christian)

- Cambridge Songs

- Capgrave, John

- Carolingian Architecture

- Carolingian Era

- Carolingian Manuscript Illumination

- Carolingian Metalwork

- Carthusians and Eremitic Orders

- Cecco d’Ascoli (Francesco Stabili)

- Charlemagne

- Charles d’Orléans

- Charters of the British Isles

- Chaucer, Geoffrey

- Christian Mysticism

- Christianity and the Church in Post-Conquest England

- Christianity and the Church in Pre-Conquest England

- Christina of Markyate

- Chronicles of England and the British Isles

- Church of the Holy Sepulchre, The

- Cistercian Architecture

- Cistercians, The

- Clanvowe, John

- Classics in the Middle Ages

- Cloud of Unknowing and Related Texts, The

- Constantinople and Byzantine Cities

- Contemporary Sagas (Bishops’ sagas and Sturlunga saga)

- Corpus Christi

- Councils and Synods of the Medieval Church

- Crusades, The

- Crusading Warfare

- da Barberino, Francesco

- da Lentini, Giacomo

- da Tempo, Antonio and da Sommacampagna, Gidino

- da Todi, Iacopone

- Dance of Death

- d’Arezzo, Ristoro

- de la Sale, Antoine

- de’ Rossi, Nicolò

- de Santa Maria, Cantigas

- Death and Dying in England

- Decorative Arts

- delle Vigne, Pier

- Drama in Britain

- Dutch Theater and Drama

- Early Italian Humanists

- Economic History

- Eddic Poetry

- England, Pre-Conquest

- England, Towns and Cities Medieval

- English Prosody

- Exeter Book, The

- Family Letters in 15th Century England

- Family Life in the Middle Ages

- Feast of Fools

- Female Monasticism to 1100

- Findern Manuscript (CUL Ff.i.6), The

- Folk Custom and Entertainment

- Food, Drink, and Diet

- Fornaldarsögur

- French Drama

- French Monarchy, The

- French of England, The

- Froissart, Jean

- Games and Recreations

- Gawain Poet, The

- German Drama

- Gerson, Jean

- Glass, Stained

- Gower, John

- Gregory VII

- Hagiography in the Byzantine Empire

- Handbooks for Confessors

- Hardyng, John

- Harley 2253 Manuscript, The

- Hiberno-Latin Literature

- High Crosses

- Hilton, Walter

- Historical Literature (Íslendingabók, Landnámabók)

- Hoccleve, Thomas

- Hood, Robin

- Hospitals in the Middle Ages

- Hundred Years War

- Hungary, Latin Literacy in Medieval

- Hungary, Libraries in Medieval

- Illuminated Manuscripts

- Illustrated Beatus Manuscripts

- Insular Art

- Insular Manuscript Illumination

- Islamic Architecture (622–1500)

- Italian Cantari

- Italian Chronicles

- Italian Drama

- Italian Mural Decoration

- Italian Novella, The

- Italian Religious Writers of the Trecento

- Italian Rhetoricians

- Jewish Manuscript Illumination

- Jews and Judaism in Medieval Europe

- Julian of Norwich

- Junius Manuscript, The

- King Arthur

- Kings and Monarchy, 1066-1485, English

- Kings’ Sagas

- Knapwell, Richard

- Lancelot-Grail Cycle

- Late Medieval Preaching

- Latin and Vernacular Song in Medieval Italy

- Latin Arts of Poetry and Prose, Medieval

- Latino, Brunetto

- Learned and Scientific Literature

- Libraries in England and Wales

- Lindisfarne Gospels

- Liturgical Drama

- Liturgical Processions

- Lollards and John Wyclif, The

- Lombards in Italy

- London, Medieval

- Love, Nicholas

- Low Countries

- Lydgate, John

- Machaut, Guillaume de

- Magic in the Medieval Theater

- Maidstone, Richard

- Malmesbury, Aldhelm of

- Malory, Sir Thomas

- Manuscript Illumination, Ottonian

- Marie de France

- Markets and Fairs

- Masculinity and Male Sexuality in the Middle Ages

- Medieval Archaeology in Britain, Fifth to Eleventh Centuri...

- Medieval Archaeology in Britain, Twelfth to Fifteenth Cent...

- Medieval Bologna

- Medieval Chant for the Mass Ordinary

- Medieval English Universities

- Medieval Ivories

- Medieval Latin Commentaries on Classical Myth

- Medieval Music Theory

- Medieval Naples

- Medieval Optics

- Mendicant Orders and Late Medieval Art Patronage in Italy

- Middle English Language

- Mosaics in Italy

- Mozarabic Art

- Music and Liturgy for the Cult of Saints

- Music in Medieval Towns and Cities

- Music of the Troubadours and Trouvères

- Musical Instruments

- Necromancy, Theurgy, and Intermediary Beings

- Nibelungenlied, The

- Nicholas of Cusa

- Nordic Laws

- Norman (and Anglo-Norman) Manuscript Ilumination

- N-Town Plays

- Nuns and Abbesses

- Old English Hexateuch, The Illustrated

- Old English Language

- Old English Literature and Critical Theory

- Old English Religious Poetry

- Old Norse-Icelandic Sagas

- Ottonian Art

- Ovid in the Middle Ages

- Ovide moralisé, The

- Owl and the Nightingale, The

- Papacy, The Medieval

- Persianate Dynastic Period/Later Caliphate (c. 800–1000)

- Peter Abelard

- Pictish Art

- Pizan, Christine de

- Plowman, Piers

- Poland, Ethnic and Religious Groups in Medieval

- Post-Conquest England

- Pre-Carolingian Western European Kingdoms

- Prick of Conscience, The

- Pucci, Antonio

- Pythagoreanism in the Middle Ages

- Rate Manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 61)

- Regions of Medieval France

- Regular Canons

- Religious Instruction (Homilies, Sermons, etc.)

- Religious Lyrics

- Robert Mannyng of Brunne

- Rolle, Richard

- Romances (East and West Norse)

- Romanesque Art

- Rus in Medieval Europe

- Ruthwell Cross

- Sagas and Tales of Icelanders

- Saint Plays and Miracles

- Saint-Denis

- Saints’ Lives

- Scandinavian Migration-Period Gold Bracteates

- Schools in Medieval Britain

- Scogan, Henry

- Sex and Sexuality

- Ships and Seafaring

- Shirley, John

- Skaldic Poetry

- Slavery in Medieval Europe

- Snorra Edda

- Song of Roland, The

- Songs, Medieval

- St. Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury

- St. Peter's in the Vatican (Rome)

- Syria and Palestine in the Byzantine Empire

- The Middle Ages, The Trojan War in

- The Use of Sarum and Other Liturgical Uses in Later Mediev...

- Theater and Performance, Iberian

- Thirteenth-Century Motets in France

- Thomas Aquinas

- Thornton, Robert

- Tomb Sculpture

- Travel and Travelers

- Trevisa, John

- Troubadours and Trouvères

- Troyes, Chrétien de

- Umayyad History

- Usk, Thomas

- Venerable Bede, The

- Vercelli Book, The

- Vernon Manuscript, The

- Von Eschenbach, Wolfram

- Wall Painting in Europe

- Wearmouth-Jarrow

- Welsh Literature

- William of Ockham

- Women's Life Cycles

- York Corpus Christi Plays

- York, Medieval

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with EHR?

- About The English Historical Review

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Books for Review

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Reading and Writing in Medieval England: Essays in Honor of Mary C. Erler, ed. Martin Chase and Maryanne Kowaleski

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jane Bliss, Reading and Writing in Medieval England: Essays in Honor of Mary C. Erler, ed. Martin Chase and Maryanne Kowaleski, The English Historical Review , Volume 135, Issue 575, August 2020, Pages 1007–1009, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceaa131

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This volume on the medieval book, its owners, and its readers begins with an Introduction by the editors, Martin Chase and Maryanne Kowaleski, which acts as a useful guide to the contributions. The essays consider a range of readers and practices of reading, from the literary and intratextual to the historical Londoners whose traces can be found in the archives.

Joyce Coleman’s opening essay revisits Troilus and Criseyde (book ii) in detail. She explores the irony of a situation in which women read about a city under siege, being under siege themselves. In this scene Pandarus pulls Criseyde away from her reading; later, Criseyde will be pulled away from the doomed city. According to Coleman, Chaucer’s portrait of the reading circle may have been inspired by his own youthful service at the court of Elizabeth de Burgh.

Caroline M. Barron considers Beatrice Melreth, a ‘London Gentlewoman’. She argues that something of Beatrice’s life may be glimpsed by examining the books she owned and the will she drew up; her reading was that of a devout and moderately learned laywoman without evidence of ‘affective piety’ (p. 54). She shared her literary culture with her sister, to whom she left the books. Similar questions underpin Sheila Lindenbaum’s study of fifteenth-century Londoners. She examines the interaction between London’s ‘middling sorts’ and educated clergy, and what they read. She challenges Sylvia Thrupp’s notion that Londoners lacked intellectual curiosity; what can look like anti-intellectualism may instead have been a reaction against dangerous religious controversy. Lindenbaum asserts that their participation in ‘classicizing civic rituals’ (p. 79) is evidence of learned culture.

Memory is another key theme in the history of engagement with books. Joel T. Rosenthal examines fifteenth-century proofs of age. This is a study of those moments when the books or documents in which events were recorded were not available at the time those events needed to be recalled. He suggests the rich insights to be gained from bringing together the concerns of his own work with the gendered insights of Erler’s scholarship, in particular since proofs of age tend to reflect a female domain of birth and baptism; meanwhile, he says, proper examination of women’s role in the context of ‘proofs of age’ awaits further inquiry (p. 98).

The collection then turns to the act of reading and intertextuality within texts themselves. Kathryn A. Smith considers the Old Testament in the Queen Mary Psalter (the text in question is the Preface to the Psalter). After interrogating the book’s production and reception, Smith discusses examples of the way Old Testament narratives are influenced by chivalric romance when recounted in the Preface of this exceptional and beautifully produced book. It is not so much that the artists were familiar with, or drew on, romance texts: the illustrations resemble those in romance manuscripts, thus creating ‘intervisual’ references (p. 113). The essay is lavishly illustrated. This kind of multi-layered involvement with the book is also explored by Michael G. Sargent, with regard to Walter Hilton’s Scale of Perfection at Syon Abbey. However, Sargent argues for a form of reading and engagement that is specific to the Bridgettine nuns and distinct from wider clerical or lay literacy. He develops a comparison between Hilton’s book and The Mirror of Our Lady , and traces layers of non-linear reading that includes rubrics (annotations, incipits), English and Latin.

Beyond the text, scholars are increasingly turning to the materiality of books. Such a perspective is adopted here, by Heather Blatt. Strikingly, this allows her to demonstrate an important difference between men’s reading and women’s: the men are more likely to go to the book, which is supported by a lectern of some sort, to read according to the liturgy and the order of service. On the other hand, the book goes to and with the nun: she takes it away and sits in a corner to read it supported on her lap. The ‘bookmarker’ (an anchor or pin holding textile strands to mark places in the book) is crucial to this process.

The essays focus on English material with one exception. Martin Chase’s essay, ‘ Enska Vísan : Sir Orfeo in Iceland?’, nowhere identifies this Icelandic poem as a romance, in spite of points of comparison with the Middle English romance of Sir Orfeo . The ‘English Verse’ of the title is here edited, with a table of resemblances and a discussion of its affinities with other genres. At the end of the narrative, the lady is left with the ‘peaceful man’ Sunday, rather than being brought home; the protagonist journeys back into the world so that he can tell of his adventure, thus providing a record for transmission to posterity.

Reading is shown throughout the essays to have been both bound up in notions of textual community, and also highly personal. This is particularly apparent in Allison Adair Alberts’ study of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs . The female ‘martyrs’ of the book are presented as sympathetic, rather than idealised as they were in the Catholic canon. Women reading these lives can map their own concerns with (for example) nurturing their family onto the predicaments in which Foxe’s women find themselves. Hitherto, hagiography had separated the roles of saint and mother (p. 232). Instead of an emphasis on abandoning the world and the family, domestic struggles are shown by Foxe as part of the female saint’s journey to martyrdom.

There follows a bibliography of the scholarship of Mary Carpenter Erler. All the essays in the volume speak to Erler’s ‘passion for exploring lives’ (p. 7) through the books that people owned or read. It provides a rich and varied tribute to a great scholar of the history of the book.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4534

- Print ISSN 0013-8266

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

What was life like in medieval society?

Part of History Medieval society, life and religion

- Most people in medieval society lived in villages, there were few large towns.

- The majority of people were peasants, who worked on the land.

- There were a range of jobs and trades in towns and villages, some quite similar to those people might have today.

Video about life in medieval England

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Video transcript video transcript.

Narrator: Most people in medieval England were farming peasants who lived in villages in the countryside. They had a hard life working all day on farms owned by nobles. By the 12th century this was changing. New towns developed around religious buildings, castles or trade routes. These towns were crowded, noisy and smelly. At dawn, a bell would ring to begin the day. Townspeople would attend their first religious mass of the day.

Towns were not healthy places to live. Although housing did improve during the period, there was no sewage system. So people discarded their waste in the streets or local rivers. People often shared their homes with their livestock, but none of these animals were house-trained. The town was run by powerful people such as merchants and lords, while the crafts workers and traders made their living in the bustling markets.

Crime was common in towns. If someone was accused of a crime such as stealing, one of the ways they might have to prove their innocence was through a trial by boiling water. The accused would have to pick up a stone from a pot of boiling water and people believed that if the person was innocent, God would heal the wounds within three days. If not, the person was guilty. The city gates were shut at dusk and the bell was rung for curfew. A night watchman would patrol the streets to look out for criminals or wild animals to keep townspeople safe.

Life in medieval villages

In medieval society, most people lived in villages and most of the population were peasants.

Villeins close villeins Peasants who were at the bottom of the feudal system. They worked and lived in land owned by a lord and were not allowed to leave without the lord’s permission. were peasants who were legally tied to land owned by a local lord. If they wanted to move, or even get married, they needed the permission of the lord first. In return for being allowed to farm the land they lived on, villeins had to give some of the food they grew each year to the lord. Villeins worked on strips of land, spread out in different fields across the village. Life could be hard; if crops failed to produce enough food, people faced starvation.

Some peasants were called freemen close freemen Freemen were a minority of peasants who had the right to move around the country and work on different pieces of land. . These peasants were able to move round from one village to another and did not have the same restrictions on them as villeins did.

Peasants' everyday life

Peasant homes were small, often just made up of one room. A peasant's hut was made of wattle close wattle A framework for a wall or fence made from woven twigs. and daub close daub Plaster, clay, or another substance used for coating a surface, especially when mixed with straw. , with a thatch close thatch A roof covering made of straw. roof but no windows. Inside the hut, a third of the area was penned off for the animals, which lived in the hut with the family. A fire burned in a hearth in the centre of the hut, so the air was permanently eye-wateringly smoky. Furniture was maybe a couple of stools, a trunk for bedding, and a few cooking pots.

Women in peasant families learnt to spin wool from an early age, using wooden wheels to make clothes.

Children spent most of their time helping their parents with day-to-day activities. Rather than going to school, they worked on jobs in the house, looked after animals and helped grow food.

Peasants also had to pay a tithe close tithe Peasants had to give 10 per cent of what they produced on their land to the church. to the Church. A tithe was 10% of what they produced on their land. The Church was central to medieval life. People would attend services there every Sunday, and it would host marriages, christenings and funerals.

What challenges did a peasant face?

Show more Show less

Peasants in medieval England were incredibly poor. Their main aim was to grow enough food to survive. This meant they often had to work long hours and their lives could depend on whether or not they grew enough food.

A peasant’s year would be based around farming and the seasons. In spring they would plough the land and sow seeds followed by tending to crops in the summer and harvesting them in the autumn.

Food supplies would be at their lowest in spring, as the stocks from the autumn harvest would start to run out.

Life in medieval towns

There were not many towns in medieval England, and those that existed were small by modern standards. London was the largest with a population of 10,000 and Winchester the second largest with 6,000 people. The Domesday Book close Domesday Book The Domesday Book was a survey of England to establish what every person owned. This helped William establish control over England and raise taxes. gives some idea about what life in towns was like .

There were many skilled craftsmen working in towns, such as carpenters, blacksmiths and tailors. Trade was a key part of town life, with goods such as iron, wool, salt and agricultural products being commonly bought and sold. Coastal towns would trade with other countries.

Some women were able to work as shopkeepers, cloth-sellers or run pubs, but these opportunities were very limited. Similar to villages, women were also expected to work in the home, cleaning and looking after their family.

Towns were often unhygienic because of the larger populations and the lack of proper sanitation close sanitation Accessibility of clean drinking water and hygienic waste disposal. . Modern toilets and plumbing were a long way in the future and waste was thrown into the streets. Animals such as pigs and sheep roamed and butchers often threw waste meat into the street or river. These unsanitary conditions contributed to the spread of diseases, such as the Black Death.

Activity - Put these groups of people into the right order

Law and order in medieval society.

In the medieval period, there was no organised police force and most law enforcement was organised by local people. In some areas, every male over the age of 12 had to join a group called a tithing close tithing A group of 10 people who were expected to maintain law and order within their group. , and they had to make sure no one else in the group committed a crime. If someone was the victim of a crime, they had to raise the ‘hue and cry’, meaning other villagers had to come to help find the criminal.

Some areas had watchmen or constables who would patrol the area to prevent crimes. Most minor crimes were dealt with by the local lord. A judge, who was appointed by the king, travelled to each county to deal with serious crimes.

If a jury couldn't decide if a person was innocent or guilty, there was the option of trial by ordeal . This is where people were subjected to painful tasks, such as:

- Walking on hot coals

- Putting your hand in boiling water to retrieve a stone

- Holding a red-hot iron

If your wounds healed cleanly after three days, then you were considered to be innocent in the eyes of God. If not, you were considered guilty and would be punished accordingly. Punishments included being put in the stocks, fines, or even death for more serious crimes.

Education in medieval society

Some children went to school to learn to read and write, but most didn't. Schools were expensive and usually located in towns. Children from wealthy families may have had a tutor or attended a grammar school, but the cost of schooling meant that most children could not afford to go. There were also schools in monasteries close monastery Buildings lived in by a community of monks who live under religious vows. , but places often went to children who were to become monks.

Instead of formal schooling, many medieval children learned how to farm, grow food and tend to animals. Some also learned a trade and perhaps became an apprentice to a local craftsperson like a carpenter or a tailor.

Test your knowledge

History Detectives game. game History Detectives game

Analyse and evaluate evidence to uncover some of history’s burning questions in this game

More on Medieval society, life and religion

Find out more by working through a topic

The Church's role in medieval life in England

- count 2 of 2

Life and Culture in Medieval England

Welcome to a journey through time to explore the fascinating world of medieval England . This period in history stretches from the 5th century to the end of the 15th century, marked by incredible changes in society, economy , culture, religion , and politics.

As we delve deeper into the life and culture of medieval England , we’ll discover the rich tapestry of events and characters that shaped this incredible era. From the Norman Conquest to the rise of feudalism , from chivalry and knights to the role of medicine and healthcare , we’ll explore every aspect of medieval life.

Join us on this exciting journey through time to discover the wonders of medieval England .

Key Takeaways

- Medieval England was a period in history that spanned from the 5th to the 15th century.

- During this time, the country witnessed significant changes in society, economy , culture, religion , and politics.

- The Norman Conquest and the rise of feudalism were two crucial events that shaped the medieval period in England.

- Other key areas of interest include the role of religion , art , architecture , education , healthcare , literature , and entertainment .

The Rise of Medieval England

In 1066, the Norman Conquest transformed England into a powerful nation that would have significant impact on the course of history . William the Conqueror’s victory over King Harold Godwinson marked the beginning of medieval England, a period of great cultural and social change. The Norman Conquest brought sweeping changes to the country’s political, economic, and social landscape. The events that followed over the next few centuries would shape the nation and lay a foundation for modern England .

The Norman Conquest brought about the introduction of Norman-French language and culture, which had a significant impact on English society. The new ruling class established a feudal system that granted land ownership and control to a small group of elite nobles. The role of the king was greatly expanded under the Norman monarchs , and a powerful central government was established. This period also saw the emergence of chivalry and the rise of knights as key figures in society.

The medieval period in England was marked by constant warfare, both domestic and foreign. The country experienced multiple invasions, including those by the Vikings and the Normans. The resulting conflicts and battles shaped the country’s culture and politics in profound ways. The Hundred Years’ War between England and France , which began in 1337, was one of the most significant events of the medieval period. This prolonged conflict had a profound impact on the country’s political and economic systems, and ultimately led to the downfall of the Plantagenet dynasty.

The Norman Conquest

In 1066, William the Conqueror led the Norman invasion of England, defeating King Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings. The Norman Conquest marked a turning point in English history, bringing about significant changes in the country’s political, social, and economic systems.

The Normans introduced a feudal system, which divided society into distinct classes based on land ownership and labor. The king held ultimate power and granted land to barons and nobles in exchange for military service. The peasants who lived and worked on the land were subject to their lords and had little freedom or autonomy.

The Norman Conquest also had a significant impact on the English language. French became the language of the ruling class, and many French words and phrases were incorporated into English. This period saw the development of Middle English, a linguistic evolution that had a profound impact on the language and literature of England and beyond.

Social Structure and Daily Life

Medieval England was highly stratified, with a rigid social hierarchy that determined people’s roles, rights, and obligations. At the top of the pyramid were the nobility, who owned vast estates, held political power, and enjoyed exclusive privileges. Below them were the clergy, who provided spiritual guidance and administered religious institutions. The vast majority of the population, however, belonged to the peasantry, who worked the land, paid taxes, and provided military service to their lords.

Daily life in medieval England was hard, demanding, and often unpredictable. The vast majority of people lived in rural areas, where they depended on agriculture for their survival. They worked long hours in the fields, tended to their cattle, and engaged in various crafts and trades to supplement their income. Many people lacked basic necessities such as clean water, sanitation, and healthcare , which made them vulnerable to diseases and epidemics.

However, despite the challenges, medieval life was not without its pleasures. People enjoyed communal activities such as festivals, fairs, and sports, where they could socialize, dance, and watch performances. They also participated in religious rituals and celebrations, which provided a sense of community and belonging.

In terms of gender roles, women in medieval England had limited opportunities for education , employment, and political participation. Their main role was to serve as wives, mothers, and caregivers, and to manage household activities such as cooking, sewing, and cleaning. Men, on the other hand, were expected to fulfill their duties as laborers, soldiers, and protectors of their families. They also had more opportunities for education and occupational mobility than women.