Learn Anthropology

No products in the cart.

Username or Email Address

Remember Me Forgot Password?

A link to set a new password will be sent to your email address.

Your personal data will be used to support your experience throughout this website, to manage access to your account, and for other purposes described in our privacy policy .

Get New Password -->

Quantitative Data

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2023

Quantitative data has long been a core component of anthropological research. Since the advent of cultural anthropology during the early 20th century, numerical and statistical methods have been employed to further our understanding of human cultures , behaviors, and societies [1] .

Overview of Quantitative Data in Anthropology

In anthropology , quantitative data involves the collection and analysis of numerical information to reveal patterns, trends, correlations, or generalizations about the human condition. This can be gleaned from various sources such as population censuses, health records, economic indicators, or surveys.

For instance, an anthropologist studying dietary practices across cultures might employ quantitative methods to measure and compare food intake or nutritional indices. A seminal work in this regard is Murdock’s [2] . Ethnographic Atlas, which compiled quantitative data on a variety of cultural traits across hundreds of societies, providing invaluable insights into cross-cultural patterns and diversities.

While quantitative data provides rigorous, generalizable insights, it’s important to recognize that it is often complemented by qualitative data, offering a holistic understanding of human experiences [1] .

Methodology

Research design.

In anthropological research, design is instrumental to the structure and execution of a study. A common research design is the cross-sectional study, where data is collected from a sample population at a specific point in time [1] . This is often employed in cultural anthropology to assess variations across different cultural groups or regions.

Data Collection Techniques

- Surveys: Surveys are standard instruments for collecting quantitative data. Anthropologists often use structured interviews or standardized questionnaires to gather information about beliefs, behaviors, and social practices.

- Questionnaires: Questionnaires, either self-administered or researcher-administered, are used to gather standardized data. In an anthropological study examining social networks, questionnaire items might include queries about respondents’ relationships and interactions.

- Experiments: Experimental methods are used less frequently in anthropology but can offer valuable insights. Laboratory or field experiments, for instance, can help determine causal relationships or test hypotheses about human behavior.

- Archival Research: Anthropologists may use archival data, such as historical documents, census data, or institutional records, to gather quantitative information.

Sampling Techniques

There are two types of sampling techniques in research: Probability Sampling Methods and Non-Probability Methods.

Probability sampling methods ensure each member of a population has a known, non-zero chance of being selected , facilitating the collection of unbiased, representative data. These techniques offer more precise and generalizable findings. Here are several types of probability sampling methods:

- Simple Random Sampling (SRS): In SRS, each individual in the population has an equal and independent chance of being chosen for the sample. This method ensures a high level of representativeness, and conclusions drawn from the sample can be generalized to the population. However, it requires an exhaustive list of all members in the population, which may not always be feasible.

- Systematic Sampling: This involves selecting a random starting point from the population list and then picking every nth element. The key benefit is its simplicity. But, the order of the list may introduce bias if there’s a pattern that coincides with the chosen interval.

- Stratified Sampling: The population is divided into homogeneous subgroups, or strata, and random samples are drawn from each stratum. This technique ensures representation of all key groups within the population and can increase the efficiency and precision of the estimate.

- Cluster Sampling: In this method, the population is divided into clusters, usually geographically. Random clusters are then chosen and all individuals within these clusters are included in the sample. This method can save time and resources when the population is geographically dispersed but might be less precise than simple random or stratified sampling.

Non-probability sampling techniques don’t give each member of a population a known chance of being included in the sample. These methods are often used when it’s not feasible to conduct probability sampling, and while they can be easier and cheaper to implement, they don’t allow for statistical inference about the entire population.

- Convenience Sampling: This is the most straightforward type of non-probability sampling, where participants are selected based on their availability or ease of access. It’s used when a random sample isn’t necessary or when it isn’t feasible to choose a random sample. However, the results may not be representative of the broader population.

- Snowball Sampling: Also known as referral sampling, this method is often used when it’s difficult to identify members of a desired population. Researchers start with a small pool of initial informants, then each of those informants provides referrals to other participants, creating a ‘snowball’ effect. This method is particularly useful when studying hidden or hard-to-reach populations.

- Quota Sampling: This method is the non-probability counterpart of stratified sampling. Researchers divide the population into specific groups based on relevant characteristics and then non-randomly select individuals from each group until the quotas are filled. The proportion of participants in each quota matches their proportion in the population.

- Purposive Sampling: In this method, researchers use their judgment to select participants who are most able to contribute useful data. For example, if conducting research on specialized practices within a culture, anthropologists might use purposive sampling to select individuals who are considered experts in those practices.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics.

Descriptive statistics summarize and describe the main features of a dataset. Anthropologists use them to provide a clear and concise summary of their data.

- Measures of Central Tendency: These include the mean (average), median (middle value), and mode (most frequent value). For instance, an anthropologist studying age at marriage in a community might use the mean age to describe the central tendency of their data.

- Measures of Dispersion: These describe the spread or variability of the data, including range, variance, and standard deviation. For instance, studying income distribution in a society, the range of incomes and the standard deviation can help understand economic inequality.

Inferential Statistics

Inferential statistics allow researchers to draw conclusions about a population based on a sample. They form the backbone of hypothesis testing in anthropological research.

- Hypothesis Testing: Hypothesis testing involves proposing a claim about a population parameter and then using sample data to test the claim. For instance, an anthropologist might hypothesize that there is a significant difference in fertility rates between two cultural groups.

- Confidence Intervals: These provide a range of values within which the population parameter is likely to fall. An anthropologist estimating the average number of children per woman in a community might report it as a range, giving a confidence interval.

- Correlation Analysis: This measures the relationship between two variables. For instance, an anthropologist might analyze the correlation between education level and income within a society.

- Regression Analysis: This allows researchers to predict the value of one variable based on the value of another. An anthropologist could use regression analysis to predict a community member’s social status based on variables like age, education, and occupation.

Comparisons with Qualitative Data

Advantages of quantitative data.

Quantitative data provide numeric evidence that can be analyzed statistically to support or refute hypotheses about a population. The results are replicable, allowing for generalizability of findings. For instance, anthropologists might use quantitative data to measure the prevalence of a certain cultural practice in different societies.

Limitations of Quantitative Data

Despite its strengths, quantitative data isn’t well-suited to explore all research questions. It often fails to capture the richness and complexity of human experiences and doesn’t illuminate the meanings or interpretations people assign to their experiences. It also requires a larger sample size to be statistically significant and might oversimplify complex social phenomena.

Complementary Relationship between Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Qualitative and quantitative data serve complementary roles in anthropological research. While quantitative data can illustrate patterns and trends across a population, qualitative data can provide a deep, nuanced understanding of the cultural context and individual perspectives. For instance, an anthropologist might combine a quantitative survey of marriage patterns in a community with qualitative interviews to understand the underlying beliefs and norms influencing these patterns.

Summary of the Article’s Main Points

This article has comprehensively covered the concept, methodologies, analysis, and comparison of quantitative data in anthropological research. Quantitative data provides numerical evidence that facilitates a statistical understanding of phenomena, such as cultural practices or societal trends. Key methodologies discussed include research design, data collection, and sampling techniques, both probability and non-probability. The use of descriptive and inferential statistics in analyzing quantitative data has also been outlined, from measures of central tendency and dispersion to hypothesis testing and regression analysis. The advantages and limitations of quantitative data were considered alongside qualitative data, illuminating their complementary relationship in anthropological research.

Implications for Anthropology and Future Research

Quantitative data plays a crucial role in anthropology, providing a foundation for testing hypotheses and making generalizable conclusions. Yet, the importance of blending these approaches with qualitative methods to obtain a richer, more nuanced understanding of cultural phenomena has been highlighted. For future research, embracing a mixed-methods approach will continue to strengthen the anthropological understanding of human societies and cultures. As we navigate the evolving landscapes of research, the refinement of data collection techniques, alongside advancements in data analysis tools, will further enhance the application and utility of quantitative data in anthropology.

References:

[1] Bernard, H. R. (2011). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. AltaMira Press. https://ds.amu.edu.et/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/11396/Russel-Research-Method-in-Anthropology.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[2] Murdock, G. P. (1967). Ethnographic Atlas. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Vasundhra, an anthropologist, embarks on a captivating journey to decode the enigmatic tapestry of human society. Fueled by an insatiable curiosity, she unravels the intricacies of social phenomena, immersing herself in the lived experiences of diverse cultures. Armed with an unwavering passion for understanding the very essence of our existence, Vasundhra fearlessly navigates the labyrinth of genetic and social complexities that shape our collective identity. Her recent publication unveils the story of the Ancient DNA field, illuminating the pervasive global North-South divide. With an irresistible blend of eloquence and scientific rigor, Vasundhra effortlessly captivates audiences, transporting them to the frontiers of anthropological exploration.

Newsletter Updates

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

I accept the Privacy Policy

Related Posts

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.6: Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 150177

- Jennifer Hasty, David G. Lewis, & Marjorie M. Snipes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify differences between quantitative and qualitative information.

- Provide an example of how an anthropologist might model research findings.

- Describe the steps of the scientific method.

Differences between Quantitative and Qualitative Information

Quantitative information is measurable or countable data that can provide insight into research questions. Quantitative information is one of the most direct ways to understand limited, specific questions, such as how often people in a culture perform a certain action or how many times an art form or motif appears in a cultural artifact. Statistics created from quantitative data help researchers understand trends and changes over time. Counts of cultural remains, such as the number and distribution of animal remains found at a campsite, can show how much the campsite was used and what type of animal was being hunted. Statistical comparisons may be made of several different sites that Indigenous peoples used to process food in order to determine the primary purpose of each site.

In cultural research, qualitative data allows anthropologists to understand culture based on more subjective analyses of language, behavior, ritual, symbolism, and interrelationships of people. Qualitative data has the potential for more in-depth responses via open-ended questions, which can be coded and categorized in order to better identify common themes. Qualitative analysis is less about frequency and the number of things and more about a researcher’s subjective insights and understandings. Anthropology and other fields in the social sciences frequently integrate both types of data by using mixed methods. Through the triangulation of data, anthropologists can use both objective and frequency data (for example, survey results) and subjective data (such as observations) to provide a more holistic understanding.

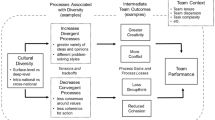

Many anthropologists create models to help others visualize and understand their research findings. Models help people understand the relationships between various points of data and can include qualitative elements as well. One very familiar model is a map. Maps are constructed from many thousands of data points projected onto a flat surface to help people understand distances and relationships. Maps are typically two-dimensional, but we are of course all familiar with the three-dimensional version of a world map known as a globe. Maps and globes are built on data points, but they also include qualitative information, such as the colors used to represent various features and the human-assigned names of various geographical features. Other familiar types of models include graphs, calendars, timelines, and charts. GPS is also a significant modeling tool today.

GPS, or the Global Position System, is increasingly used in archaeology. A model of a research site can be created using computer programs and a series of GPS coordinates. Any artifacts found or important features identified within the site can mapped to their exact locations within this model. This type of mapping is incredibly helpful if further work is warranted, making it possible for the researcher to return to the exact site where the original artifacts were found. These types of models also provide construction companies with an understanding of where the most sensitive cultural sites are located so that they may avoid destroying them. Government agencies and tribal governments are now constructing GPS maps of important cultural sites that include a variety of layers. Layering types of data within a landscape allows researchers to easily sort the available data and focus on what is most relevant to a particular question or task.

Wild food plants, water sources, roads and trails, and even individual trees can be documented and mapped with precision. Archaeologists can create complex layered maps of traditional Native landscapes, with original habitations, trails, and resource locations marked. GPS has significant applications in the re-creation of historic periods. By comparing the placements of buildings at various points in the past, GPS models can be created showing how neighborhoods or even whole cities have changed over time. In addition, layers can be created that contain cultural and historic information. These types of models are an important part of efforts to preserve remaining cultural and historic sites and features.

The Science of Anthropology

Anthropology is a science, and as such, anthropologists follow the scientific method . First, an anthropologist forms a research question based on some phenomenon they have encountered. They then construct a testable hypothesis based on their question. To test their hypothesis, they gather data and information. Information can come from one or many sources and can be either quantitative or qualitative in nature. Part of the evaluation might include statistical analyses of the data. The anthropologist then draws a conclusion. Conclusions are rarely 100 percent positive or 100 percent negative; generally, the results are somewhere on a continuum. Most conclusions to the positive will be stated as “likely” to be true. Scholars may also develop methods of testing and retesting their conclusions to make sure that what they think is true is proven true through various means. When a hypothesis is rigorously tested and the results conform with empirical observations of the world, then a theory is considered “likely to be accurate.” Hypotheses are always subject to being disproven or modified as more information is collected.

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Research methods in anthropology : qualitative and quantitative approaches

Available online, at the library.

Law Library (Crown)

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- Chapter 1. Anthropology and the Social Sciences

- Chapter 2. The Foundations of Social Research

- Chapter 3. Preparing for Research

- Chapter 4. Research Design: Experiments and Experimental Thinking

- Chapter 5. Sampling I: The Basics

- Chapter 6. Sampling II: Theory

- Chapter 7. Sampling III: Nonprobability Samples and Choosing Informants

- Chapter 8. Interviewing I: Unstructured and Semistructured

- Chapter 9. Interviewing II: Questionnaires

- Chapter 10. Interviewing III: Cultural Domains

- Chapter 11. Scales and Scaling

- Chapter 12. Participant Observation

- Chapter 13. Field Notes and Database Management

- Chapter 14. Direct and Indirect Observation

- Chapter 15. Introduction to Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

- Chapter 16. Cognitive Anthropology I: Analyzing Cultural Domains

- Chapter 17. Cognitive Anthropology II: Decision Modeling, Taxonomies, and Componential Analysis

- Chapter 18. Text Analysis I: Interpretive Analysis, Narrative Analysis, Performance Analysis, and Conversation Analysis

- Chapter 19. Text Analysis II: Schema Analysis, Grounded Theory, Content Analysis, and Analytic Induction

- Chapter 20. Univariate Analysis

- Chapter 21. Bivariate Analysis

- Chapter 22. Multivariate Analysis.

- (source: Nielsen Book Data)

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Quantitative and Qualitative Research across Cultures and Languages: Cultural Metrics and their Application

- Regular Article

- Published: 09 May 2014

- Volume 48 , pages 418–434, ( 2014 )

Cite this article

- Wolfgang Wagner 1 , 3 ,

- Karolina Hansen 2 &

- Nicole Kronberger 1

2082 Accesses

19 Citations

Explore all metrics

Growing globalisation of the world draws attention to cultural differences between people from different countries or from different cultures within the countries. Notwithstanding the diversity of people’s worldviews, current cross-cultural research still faces the challenge of how to avoid ethnocentrism; comparing Western-driven phenomena with like variables across countries without checking their conceptual equivalence clearly is highly problematic. In the present article we argue that simple comparison of measurements (in the quantitative domain) or of semantic interpretations (in the qualitative domain) across cultures easily leads to inadequate results. Questionnaire items or text produced in interviews or via open-ended questions have culturally laden meanings and cannot be mapped onto the same semantic metric. We call the culture-specific space and relationship between variables or meanings a ’cultural metric’, that is a set of notions that are inter-related and that mutually specify each other’s meaning. We illustrate the problems and their possible solutions with examples from quantitative and qualitative research. The suggested methods allow to respect the semantic space of notions in cultures and language groups and the resulting similarities or differences between cultures can be better understood and interpreted.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Trustworthiness of Content Analysis

Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Background and Procedures

Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A retrospective of research on multicultural work groups and an agenda for future research

Günter K Stahl & Martha L Maznevski

A note on terminology is due here: We follow Quine’s ( 1960 ) suggestion of the equivalence of culture and language. Particularly in our discussion of qualitative methods we feel free to use both terms as being virtually co-extensive.

There were two participants from the USA, two from Japan and one from Germany. Thus, not for all of them English was their native language, but as they were senior and internationally recognized researchers, their English level was certainly close to native speakers’ level.

There is an interesting development in statistics called Finite Mixture Modelling that could potentially become a tool for cross-cultural comparison. Building on work by Weller ( 1984 ) and Krackhardt ( 1987 ), the method models consensus in a way that allows to “identify situations in which multiple distinct but disagreeing beliefs exist between subgroups of individuals” (Mueller and Veinott 2008 , p. 899). This method may allow us to understand how cultural differences affect beliefs and attitudes, but the method is still under development and does not yet allow final evaluation (Mueller, Sieck, and Veinott 2007 ).

Allum, N. C. (1998). A social representations approach to the comparison of three textual corpora using ALCESTE . London School of Economics and Political Science, UK: Unpublished MSc Thesis.

Google Scholar

Amir, Y., & Sharon, I. (1987). Are Social Psychological Laws Cross-Culturally Valid? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18 , 383–470.

Article Google Scholar

Berry, J. W. (1989). Imposed Etics, Emics, Derived Etics. International Journal of Psychology, 24 , 721–735.

Bilewicz, M., & Bocheńska, A. (2010). How language affects two components of racial prejudice? A socio-psychological approach to linguistic relativism. In U. Okulska & P. Cap (Eds.), Perspectives in Politics and Discourse (pp. 385–396). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Chapter Google Scholar

Brislin, R. (2000). Understanding culture’s influence on behavior (2nd ed.). New York: Wadsworth.

Caillaud, S., Kalampalikis, N., & Flick, U. (2012). The Social Representations of the Bali Climate Conference in The French and German Media. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 22 (4), 363–378. doi: 10.1002/casp.1117 .

Campbell, D. R. (1961). The mutual methodological relevance of anthropology and psychology. In F. L. K. Hsu (Ed.), Psychological Anthropology . Homewood, Ill: Dorsey.

Dahlin, B., & Watkins, D. (2000). The Role Of Repetition in the Processes of Memorising and Understanding: A Comparison of The Views of German and Chinese Secondary School Students in Hong Kong. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70 , 65–84.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Douglas, M. (1982). In the Active Voice . London: Routledge & Kegan.

Gibbons, J.L., Lynn, M., Stiles, D.A., Jerez de Berducido, E., Richter, R., Walker, K. & Wiley, D. (1993). Guatemalan, Filipino, and U.S.A. adolescents’ images of women as office workers and homemakers. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 17, 373-388.

Greenfield, P. M. (2000). Three Approaches to the Psychology of Culture: Where do they come from? Where do they go? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3 (3), 223–240.

Hayashi, C. (1950). On The Quantification of Qualitatice Data from the Mathematics-Statistical point of view. Annals of Statistical Mathematics, 2 .

Helfrich, H. (1999). Beyond the Dilemma of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Resolving the Tension Between etic and emic Approaches. Culture & Psychology, 5 , 131–153.

Hohl, K., & Gaskell, G. (2008). European Public Perceptions of food risk: Cross-National and Methodological Comparisons. Risk Analysis, 28 (2), 311–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01021.x .

Jang, D.-H., & Kim, L. (2013). Framing ‘World class’ Differently: International and Korean Participants’ Perceptions of the World Class University Project. Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education and Educational Planning, 65 (6), 725–744.

Kim, U. (2000). Indigenous, Cultural, and Cross-cultural Psychology: A theoretical, Conceptual, and Epistemological Analysis. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3 , 265–288.

Krackhardt, D. (1987). Cognitive Social Structures. Social Networks, 9 , 109–134.

Kronberger, N. & Wagner, W. (2000). Keywords in context: Statistical analysis of text features. In: M. Bauer & G. Gaskell (Eds.). Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound. A Practical Handbook . London: Sage

Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition. (1979). What’s Cultural About Cross-Cultural Cognitive Psychology? Annual Review of Psychology, 30 , 145–172.

Lawson, C. W., & Saltmarshe, D. K. (2002). The Psychology of Economic Transformation: The impact of the Market on Social Institutions, Status and Values in a Northern Albanian Village. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23 (4), 487–500.

LeVine, R. A. (1982). Culture, Behaviour and Personality . New York: Aldine.

Mäkiniemi, J.-P., Pirttilä-Backman, A.-M., & Pieri, M. (2011). Ethical and unethical food. Social representations among Finnish, Danish and Italian students. Appetite, 56 (2), 495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.023 .

Meaning of Work Research Team (1987). International comparison of the relationships between MOW variables. In: Meaning of Work Research Team (Eds.). The Meaning of Working . New York: Academic Press

Mueller, S. T., & Veinott, E. S. (2008). Paper presented at the Cognitive Science ‘08 . Washington: DC. Cultural mixture modeling: Identifying cultural consensus (and disagreement) using finite mixture modeling.

Mueller, S. T., Sieck, W. R., & Veinott, E. S. (2007). Cultural metrics: A finite mixture models approach . Klein Associates: Final Research Report.

Piew, L. S., Sarmiento, C. Q., & Kawasaki, K. (2005). Southeast Asian and Japanese cultural influences on the understanding of scientific concepts. Proceedings of an Intellectual Exchange Project Workshop funded by the Japan Foundation for fiscal year, 2005 . Retrieved March 27, 2014 from http://home.e-catv.ne.jp/kawasaki-knym/files/Reports/7TowardRestration.pdf .

Pike, K. L. (1967). Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behavior . The Hague: Mouton.

Quine, W. V. O. (1960). Word and Object . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1969). Ontological Relativity and Other Essays . New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Reinert, M. (1983). ‘Une méthode de classification descendante hiérarchique: application a l’analyse lexicale par contexte’ [A method of descendent hierarchical classification: Application to a lexical analysis per context, French]. Les Cahiers de l’Analyse des Données, 8 (2), 187–198.

Reinert, M. (1990). ’ALCESTE. Une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurélia de Gérard de Nerval’ [ALCESTE. A methodology for analysing textual data and an application: Aurélia by Gérard de Nerval, French]. Bulletin de méthodologie sociologique , 26, 24-54.

Shweder, R. A. (2000). The psychology of practice and the practice of the three psychologies. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3 , 207–222.

Straub, J. (1999). Handlung, Interpretation, Kritik. Grundzüge einer textwissenschaftlichen Handlungs- und Kulturpsychologie [Action, interpretation, critique. An outline of a text-scientific psychology of action and culture] . Berlin: de Gruyter.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Triandis, H. C. (1996). The psychological measurement of cultural syndromes. American Psychologist, 51 , 407–415.

Triandis, H. C. (2000). Dialectics between cultural and cross-cultural psychology. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3 , 185–196.

Triandis, H. C., Bontempo, R., Leung, K., & Hui, C. K. (1990). A method for determining cultural, demographic, and personal constructs. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 21 , 302–318.

Van de Geer, J. P. (1993). Multivariate Analysis of Categorical Data: Applications . London: Sage.

Van de Vijver, F., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and Data Analysis for Cross-Cultural Research . London: Sage.

Wagner, W., & Yamori, K. (1999). Can Culture Be a Variable? Dispositional explanation and cultural metrics. In T. Sugiman, M. Karasawa, J. H. Liu, & C. Ward (Eds.), Progress in Asian Social Psychology (Vol. 2). Seoul: Kyoyook-Kwahak-Sa Publishers.

Wagner, W., Valencia, J., & Elejabarrieta, F. (1996). Relevance, discourse and the ‘hot’ stable core of social representations—A structural analysis of word associations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 35 , 331–351.

Wagner, W., Kronberger, N., Gaskell, G., Allum, N., Allansdottir, A., Cheveigné, S., Dahinden, U., Diego, C., Montali, L., Mortensen, A., Pfenning, U., Rusanen, T., & Seger, N. (2001). Nature in disorder: The troubled public of biotechnology. In G. Gaskell & M. Bauer (Eds.), Biotechnology 1996-2000: The years of controversy . London: Museum of Science and Industry.

Wagner, W., Kronberger, N., Allum, N., De Cheveigné, S., Diego, C., Gaskell, G., et al. (2002). Pandora’s genes - images of genes and nature. In M. Bauer & G. Gaskell (Eds.), Biotechnology - the Making of a Global Controversy (pp. 244–276). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weller, S. C. (1984). Cross-cultural concept of illness: Variation and validation. American Anthropologist, 86 , 341–351.

Woolf, L. M., & Hulsizer, M. R. (2011). Why diversity matters: The power of inclusion in research methods. In K. D. Keith (Ed.), Cross-cultural psychology: Contemporary themes and perspectives (pp. 56–72). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Yang, K.-S. (2000). Mono-cultural and cross-cultural indigenous approaches: The royal road to the development of a balanced global psychology. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3 (3), 241–264.

Download references

Acknowledgment

Writing of this paper by Karolina Hansen was supported by the post-doctoral internship ‘Fuga’ awarded to her by the Polish National Science Centre (DEC-2013/08/S/HS6/00573).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social and Economic Psychology, Johannes Kepler University Linz, Altenberger Straße 69 4040, Linz, Austria

Wolfgang Wagner & Nicole Kronberger

University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

Karolina Hansen

University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

Wolfgang Wagner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wolfgang Wagner .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wagner, W., Hansen, K. & Kronberger, N. Quantitative and Qualitative Research across Cultures and Languages: Cultural Metrics and their Application. Integr. psych. behav. 48 , 418–434 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-014-9269-z

Download citation

Published : 09 May 2014

Issue Date : December 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-014-9269-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cross-cultural psychology

- Cultural metric

- Quantitative research

- Qualitative research

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

A Quick Guide to Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences

(11 reviews)

Christine Davies, Carmarthen, Wales

Copyright Year: 2020

Last Update: 2021

Publisher: University of Wales Trinity Saint David

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Tiffany Kindratt, Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Arlington on 3/9/24

The text provides a brief overview of quantitative research topics that is geared towards research in the fields of education, sociology, business, and nursing. The author acknowledges that the textbook is not a comprehensive resource but offers... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The text provides a brief overview of quantitative research topics that is geared towards research in the fields of education, sociology, business, and nursing. The author acknowledges that the textbook is not a comprehensive resource but offers references to other resources that can be used to deepen the knowledge. The text does not include a glossary or index. The references in the figures for each chapter are not included in the reference section. It would be helpful to include those.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

Overall, the text is accurate. For example, Figure 1 on page 6 provides a clear overview of the research process. It includes general definitions of primary and secondary research. It would be helpful to include more details to explain some of the examples before they are presented. For instance, the example on page 5 was unclear how it pertains to the literature review section.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

In general, the text is relevant and up-to-date. The text includes many inferences of moving from qualitative to quantitative analysis. This was surprising to me as a quantitative researcher. The author mentions that moving from a qualitative to quantitative approach should only be done when needed. As a predominantly quantitative researcher, I would not advice those interested in transitioning to using a qualitative approach that qualitative research would enhance their research—not something that should only be done if you have to.

Clarity rating: 4

The text is written in a clear manner. It would be helpful to the reader if there was a description of the tables and figures in the text before they are presented.

Consistency rating: 4

The framework for each chapter and terminology used are consistent.

Modularity rating: 4

The text is clearly divided into sections within each chapter. Overall, the chapters are a similar brief length except for the chapter on data analysis, which is much more comprehensive than others.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The topics in the text are presented in a clear and logical order. The order of the text follows the conventional research methodology in social sciences.

Interface rating: 5

I did not encounter any interface issues when reviewing this text. All links worked and there were no distortions of the images or charts that may confuse the reader.

Grammatical Errors rating: 3

There are some grammatical/typographical errors throughout. Of note, for Section 5 in the table of contents. “The” should be capitalized to start the title. In the title for Table 3, the “t” in typical should be capitalized.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The examples are culturally relevant. The text is geared towards learners in the UK, but examples are relevant for use in other countries (i.e., United States). I did not see any examples that may be considered culturally insensitive or offensive in any way.

I teach a course on research methods in a Bachelor of Science in Public Health program. I would consider using some of the text, particularly in the analysis chapter to supplement the current textbook in the future.

Reviewed by Finn Bell, Assistant Professor, University of Michigan, Dearborn on 1/3/24

For it being a quick guide and only 26 pages, it is very comprehensive, but it does not include an index or glossary. read more

For it being a quick guide and only 26 pages, it is very comprehensive, but it does not include an index or glossary.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

As far as I can tell, the text is accurate, error-free and unbiased.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

This text is up-to-date, and given the content, unlikely to become obsolete any time soon.

Clarity rating: 5

The text is very clear and accessible.

Consistency rating: 5

The text is internally consistent.

Modularity rating: 5

Given how short the text is, it seems unnecessary to divide it into smaller readings, nonetheless, it is clearly labelled such that an instructor could do so.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The text is well-organized and brings readers through basic quantitative methods in a logical, clear fashion.

Easy to navigate. Only one table that is split between pages, but not in a way that is confusing.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

There were no noticeable grammatical errors.

The examples in this book don't give enough information to rate this effectively.

This text is truly a very quick guide at only 26 double-spaced pages. Nonetheless, Davies packs a lot of information on the basics of quantitative research methods into this text, in an engaging way with many examples of the concepts presented. This guide is more of a brief how-to that takes readers as far as how to select statistical tests. While it would be impossible to fully learn quantitative research from such a short text, of course, this resource provides a great introduction, overview, and refresher for program evaluation courses.

Reviewed by Shari Fedorowicz, Adjunct Professor, Bridgewater State University on 12/16/22

The text is indeed a quick guide for utilizing quantitative research. Appropriate and effective examples and diagrams were used throughout the text. The author clearly differentiates between use of quantitative and qualitative research providing... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The text is indeed a quick guide for utilizing quantitative research. Appropriate and effective examples and diagrams were used throughout the text. The author clearly differentiates between use of quantitative and qualitative research providing the reader with the ability to distinguish two terms that frequently get confused. In addition, links and outside resources are provided to deepen the understanding as an option for the reader. The use of these links, coupled with diagrams and examples make this text comprehensive.

The content is mostly accurate. Given that it is a quick guide, the author chose a good selection of which types of research designs to include. However, some are not provided. For example, correlational or cross-correlational research is omitted and is not discussed in Section 3, but is used as a statistical example in the last section.

Examples utilized were appropriate and associated with terms adding value to the learning. The tables that included differentiation between types of statistical tests along with a parametric/nonparametric table were useful and relevant.

The purpose to the text and how to use this guide book is stated clearly and is established up front. The author is also very clear regarding the skill level of the user. Adding to the clarity are the tables with terms, definitions, and examples to help the reader unpack the concepts. The content related to the terms was succinct, direct, and clear. Many times examples or figures were used to supplement the narrative.

The text is consistent throughout from contents to references. Within each section of the text, the introductory paragraph under each section provides a clear understanding regarding what will be discussed in each section. The layout is consistent for each section and easy to follow.

The contents are visible and address each section of the text. A total of seven sections, including a reference section, is in the contents. Each section is outlined by what will be discussed in the contents. In addition, within each section, a heading is provided to direct the reader to the subtopic under each section.

The text is well-organized and segues appropriately. I would have liked to have seen an introductory section giving a narrative overview of what is in each section. This would provide the reader with the ability to get a preliminary glimpse into each upcoming sections and topics that are covered.

The book was easy to navigate and well-organized. Examples are presented in one color, links in another and last, figures and tables. The visuals supplemented the reading and placed appropriately. This provides an opportunity for the reader to unpack the reading by use of visuals and examples.

No significant grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The text is not offensive or culturally insensitive. Examples were inclusive of various races, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

This quick guide is a beneficial text to assist in unpacking the learning related to quantitative statistics. I would use this book to complement my instruction and lessons, or use this book as a main text with supplemental statistical problems and formulas. References to statistical programs were appropriate and were useful. The text did exactly what was stated up front in that it is a direct guide to quantitative statistics. It is well-written and to the point with content areas easy to locate by topic.

Reviewed by Sarah Capello, Assistant Professor, Radford University on 1/18/22

The text claims to provide "quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences," which it does. There is no index or glossary, although vocabulary words are bolded and defined throughout the text. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

The text claims to provide "quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences," which it does. There is no index or glossary, although vocabulary words are bolded and defined throughout the text.

The content is mostly accurate. I would have preferred a few nuances to be hashed out a bit further to avoid potential reader confusion or misunderstanding of the concepts presented.

The content is current; however, some of the references cited in the text are outdated. Newer editions of those texts exist.

The text is very accessible and readable for a variety of audiences. Key terms are well-defined.

There are no content discrepancies within the text. The author even uses similarly shaped graphics for recurring purposes throughout the text (e.g., arrow call outs for further reading, rectangle call outs for examples).

The content is chunked nicely by topics and sections. If it were used for a course, it would be easy to assign different sections of the text for homework, etc. without confusing the reader if the instructor chose to present the content in a different order.

The author follows the structure of the research process. The organization of the text is easy to follow and comprehend.

All of the supplementary images (e.g., tables and figures) were beneficial to the reader and enhanced the text.

There are no significant grammatical errors.

I did not find any culturally offensive or insensitive references in the text.

This text does the difficult job of introducing the complicated concepts and processes of quantitative research in a quick and easy reference guide fairly well. I would not depend solely on this text to teach students about quantitative research, but it could be a good jumping off point for those who have no prior knowledge on this subject or those who need a gentle introduction before diving in to more advanced and complex readings of quantitative research methods.

Reviewed by J. Marlie Henry, Adjunct Faculty, University of Saint Francis on 12/9/21

Considering the length of this guide, this does a good job of addressing major areas that typically need to be addressed. There is a contents section. The guide does seem to be organized accordingly with appropriate alignment and logical flow of... read more

Considering the length of this guide, this does a good job of addressing major areas that typically need to be addressed. There is a contents section. The guide does seem to be organized accordingly with appropriate alignment and logical flow of thought. There is no glossary but, for a guide of this length, a glossary does not seem like it would enhance the guide significantly.

The content is relatively accurate. Expanding the content a bit more or explaining that the methods and designs presented are not entirely inclusive would help. As there are different schools of thought regarding what should/should not be included in terms of these designs and methods, simply bringing attention to that and explaining a bit more would help.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

This content needs to be updated. Most of the sources cited are seven or more years old. Even more, it would be helpful to see more currently relevant examples. Some of the source authors such as Andy Field provide very interesting and dynamic instruction in general, but they have much more current information available.

The language used is clear and appropriate. Unnecessary jargon is not used. The intent is clear- to communicate simply in a straightforward manner.

The guide seems to be internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework. There do not seem to be issues in this area. Terminology is internally consistent.

For a guide of this length, the author structured this logically into sections. This guide could be adopted in whole or by section with limited modifications. Courses with fewer than seven modules could also logically group some of the sections.

This guide does present with logical organization. The topics presented are conceptually sequenced in a manner that helps learners build logically on prior conceptualization. This also provides a simple conceptual framework for instructors to guide learners through the process.

Interface rating: 4

The visuals themselves are simple, but they are clear and understandable without distracting the learner. The purpose is clear- that of learning rather than visuals for the sake of visuals. Likewise, navigation is clear and without issues beyond a broken link (the last source noted in the references).

This guide seems to be free of grammatical errors.

It would be interesting to see more cultural integration in a guide of this nature, but the guide is not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. The language used seems to be consistent with APA's guidelines for unbiased language.

Reviewed by Heng Yu-Ku, Professor, University of Northern Colorado on 5/13/21

The text covers all areas and ideas appropriately and provides practical tables, charts, and examples throughout the text. I would suggest the author also provides a complete research proposal at the end of Section 3 (page 10) and a comprehensive... read more

The text covers all areas and ideas appropriately and provides practical tables, charts, and examples throughout the text. I would suggest the author also provides a complete research proposal at the end of Section 3 (page 10) and a comprehensive research study as an Appendix after section 7 (page 26) to help readers comprehend information better.

For the most part, the content is accurate and unbiased. However, the author only includes four types of research designs used on the social sciences that contain quantitative elements: 1. Mixed method, 2) Case study, 3) Quasi-experiment, and 3) Action research. I wonder why the correlational research is not included as another type of quantitative research design as it has been introduced and emphasized in section 6 by the author.

I believe the content is up-to-date and that necessary updates will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement.

The text is easy to read and provides adequate context for any technical terminology used. However, the author could provide more detailed information about estimating the minimum sample size but not just refer the readers to use the online sample calculators at a different website.

The text is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework. The author provides the right amount of information with additional information or resources for the readers.

The text includes seven sections. Therefore, it is easier for the instructor to allocate or divide the content into different weeks of instruction within the course.

Yes, the topics in the text are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The author provides clear and precise terminologies, summarizes important content in Table or Figure forms, and offers examples in each section for readers to check their understanding.

The interface of the book is consistent and clear, and all the images and charts provided in the book are appropriate. However, I did encounter some navigation problems as a couple of links are not working or requires permission to access those (pages 10 and 27).

No grammatical errors were found.

No culturally incentive or offensive in its language and the examples provided were found.

As the book title stated, this book provides “A Quick Guide to Quantitative Research in Social Science. It offers easy-to-read information and introduces the readers to the research process, such as research questions, research paradigms, research process, research designs, research methods, data collection, data analysis, and data discussion. However, some links are not working or need permissions to access them (pages 10 and 27).

Reviewed by Hsiao-Chin Kuo, Assistant Professor, Northeastern Illinois University on 4/26/21, updated 4/28/21

As a quick guide, it covers basic concepts related to quantitative research. It starts with WHY quantitative research with regard to asking research questions and considering research paradigms, then provides an overview of research design and... read more

As a quick guide, it covers basic concepts related to quantitative research. It starts with WHY quantitative research with regard to asking research questions and considering research paradigms, then provides an overview of research design and process, discusses methods, data collection and analysis, and ends with writing a research report. It also identifies its target readers/users as those begins to explore quantitative research. It would be helpful to include more examples for readers/users who are new to quantitative research.

Its content is mostly accurate and no bias given its nature as a quick guide. Yet, it is also quite simplified, such as its explanations of mixed methods, case study, quasi-experimental research, and action research. It provides resources for extended reading, yet more recent works will be helpful.

The book is relevant given its nature as a quick guide. It would be helpful to provide more recent works in its resources for extended reading, such as the section for Survey Research (p. 12). It would also be helpful to include more information to introduce common tools and software for statistical analysis.

The book is written with clear and understandable language. Important terms and concepts are presented with plain explanations and examples. Figures and tables are also presented to support its clarity. For example, Table 4 (p. 20) gives an easy-to-follow overview of different statistical tests.

The framework is very consistent with key points, further explanations, examples, and resources for extended reading. The sample studies are presented following the layout of the content, such as research questions, design and methods, and analysis. These examples help reinforce readers' understanding of these common research elements.

The book is divided into seven chapters. Each chapter clearly discusses an aspect of quantitative research. It can be easily divided into modules for a class or for a theme in a research method class. Chapters are short and provides additional resources for extended reading.

The topics in the chapters are presented in a logical and clear structure. It is easy to follow to a degree. Though, it would be also helpful to include the chapter number and title in the header next to its page number.

The text is easy to navigate. Most of the figures and tables are displayed clearly. Yet, there are several sections with empty space that is a bit confusing in the beginning. Again, it can be helpful to include the chapter number/title next to its page number.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

No major grammatical errors were found.

There are no cultural insensitivities noted.

Given the nature and purpose of this book, as a quick guide, it provides readers a quick reference for important concepts and terms related to quantitative research. Because this book is quite short (27 pages), it can be used as an overview/preview about quantitative research. Teacher's facilitation/input and extended readings will be needed for a deeper learning and discussion about aspects of quantitative research.

Reviewed by Yang Cheng, Assistant Professor, North Carolina State University on 1/6/21

It covers the most important topics such as research progress, resources, measurement, and analysis of the data. read more

It covers the most important topics such as research progress, resources, measurement, and analysis of the data.

The book accurately describes the types of research methods such as mixed-method, quasi-experiment, and case study. It talks about the research proposal and key differences between statistical analyses as well.

The book pinpointed the significance of running a quantitative research method and its relevance to the field of social science.

The book clearly tells us the differences between types of quantitative methods and the steps of running quantitative research for students.

The book is consistent in terms of terminologies such as research methods or types of statistical analysis.

It addresses the headlines and subheadlines very well and each subheading should be necessary for readers.

The book was organized very well to illustrate the topic of quantitative methods in the field of social science.

The pictures within the book could be further developed to describe the key concepts vividly.

The textbook contains no grammatical errors.

It is not culturally offensive in any way.

Overall, this is a simple and quick guide for this important topic. It should be valuable for undergraduate students who would like to learn more about research methods.

Reviewed by Pierre Lu, Associate Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 11/20/20

As a quick guide to quantitative research in social sciences, the text covers most ideas and areas. read more

As a quick guide to quantitative research in social sciences, the text covers most ideas and areas.

Mostly accurate content.

As a quick guide, content is highly relevant.

Succinct and clear.

Internally, the text is consistent in terms of terminology used.

The text is easily and readily divisible into smaller sections that can be used as assignments.

I like that there are examples throughout the book.

Easy to read. No interface/ navigation problems.

No grammatical errors detected.

I am not aware of the culturally insensitive description. After all, this is a methodology book.

I think the book has potential to be adopted as a foundation for quantitative research courses, or as a review in the first weeks in advanced quantitative course.

Reviewed by Sarah Fischer, Assistant Professor, Marymount University on 7/31/20

It is meant to be an overview, but it incredibly condensed and spends almost no time on key elements of statistics (such as what makes research generalizable, or what leads to research NOT being generalizable). read more

It is meant to be an overview, but it incredibly condensed and spends almost no time on key elements of statistics (such as what makes research generalizable, or what leads to research NOT being generalizable).

Content Accuracy rating: 1

Contains VERY significant errors, such as saying that one can "accept" a hypothesis. (One of the key aspect of hypothesis testing is that one either rejects or fails to reject a hypothesis, but NEVER accepts a hypothesis.)

Very relevant to those experiencing the research process for the first time. However, it is written by someone working in the natural sciences but is a text for social sciences. This does not explain the errors, but does explain why sometimes the author assumes things about the readers ("hail from more subjectivist territory") that are likely not true.

Clarity rating: 3

Some statistical terminology not explained clearly (or accurately), although the author has made attempts to do both.

Very consistently laid out.

Chapters are very short yet also point readers to outside texts for additional information. Easy to follow.

Generally logically organized.

Easy to navigate, images clear. The additional sources included need to linked to.

Minor grammatical and usage errors throughout the text.

Makes efforts to be inclusive.

The idea of this book is strong--short guides like this are needed. However, this book would likely be strengthened by a revision to reduce inaccuracies and improve the definitions and technical explanations of statistical concepts. Since the book is specifically aimed at the social sciences, it would also improve the text to have more examples that are based in the social sciences (rather than the health sciences or the arts).

Reviewed by Michelle Page, Assistant Professor, Worcester State University on 5/30/20

This text is exactly intended to be what it says: A quick guide. A basic outline of quantitative research processes, akin to cliff notes. The content provides only the essentials of a research process and contains key terms. A student or new... read more

This text is exactly intended to be what it says: A quick guide. A basic outline of quantitative research processes, akin to cliff notes. The content provides only the essentials of a research process and contains key terms. A student or new researcher would not be able to use this as a stand alone guide for quantitative pursuits without having a supplemental text that explains the steps in the process more comprehensively. The introduction does provide this caveat.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

There are no biases or errors that could be distinguished; however, it’s simplicity in content, although accurate for an outline of process, may lack a conveyance of the deeper meanings behind the specific processes explained about qualitative research.

The content is outlined in traditional format to highlight quantitative considerations for formatting research foundational pieces. The resources/references used to point the reader to literature sources can be easily updated with future editions.

The jargon in the text is simple to follow and provides adequate context for its purpose. It is simplified for its intention as a guide which is appropriate.

Each section of the text follows a consistent flow. Explanation of the research content or concept is defined and then a connection to literature is provided to expand the readers understanding of the section’s content. Terminology is consistent with the qualitative process.

As an “outline” and guide, this text can be used to quickly identify the critical parts of the quantitative process. Although each section does not provide deeper content for meaningful use as a stand alone text, it’s utility would be excellent as a reference for a course and can be used as an content guide for specific research courses.

The text’s outline and content are aligned and are in a logical flow in terms of the research considerations for quantitative research.

The only issue that the format was not able to provide was linkable articles. These would have to be cut and pasted into a browser. Functional clickable links in a text are very successful at leading the reader to the supplemental material.

No grammatical errors were noted.

This is a very good outline “guide” to help a new or student researcher to demystify the quantitative process. A successful outline of any process helps to guide work in a logical and systematic way. I think this simple guide is a great adjunct to more substantial research context.

Table of Contents

- Section 1: What will this resource do for you?

- Section 2: Why are you thinking about numbers? A discussion of the research question and paradigms.

- Section 3: An overview of the Research Process and Research Designs

- Section 4: Quantitative Research Methods

- Section 5: the data obtained from quantitative research

- Section 6: Analysis of data

- Section 7: Discussing your Results

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This resource is intended as an easy-to-use guide for anyone who needs some quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences, covering subjects such as education, sociology, business, nursing. If you area qualitative researcher who needs to venture into the world of numbers, or a student instructed to undertake a quantitative research project despite a hatred for maths, then this booklet should be a real help.

The booklet was amended in 2022 to take into account previous review comments.

About the Contributors

Christine Davies , Ph.D

Contribute to this Page

Quick links

- Directories

Quantitative Methods

Related faculty.

Dan T. A. Eisenberg

Darryl Holman

Patricia A. Kramer

Melanie Martin

Ben Marwick

Latest news.

- Anthropology researchers awarded prize in Decoding Maternal Morbidity Data Challenge (December 8, 2021)

- Anthropology, actually — Forging a social scientist career path (April 22, 2019)

Related Research

- Xu, Jing. "Unruly" Children: Historical Fieldnotes and Learning Morality in a Taiwan Village . Cambridge University Press. Forthcoming.

- Xu, Jing. 2023. Re-discovering "the Child": A Re-interpretation of Arthur & Margery Wolf's Classic Fieldnotes. Sociological Review of China , no.9: 65-88. In Chinese.

- Yichun Chen & Ben Marwick (2023) Women in the Lab, Men in the Field? Correlations between Gender and Research Topics at Three Major Archaeology Conferences, Journal of Field Archaeology, DOI: 10.1080/00934690.2023.2261083

- Glass, D. J., John-Stewart, G., Shattuck, E., Njuguna, I., & Enquobahrie, D. (2023). Cofactors of Longitudinal Linear Growth Among Infants With And Without In-Utero HIV/Antiretroviral Exposure In Kenya. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DBMG9

- Glass, D. J., Young, Y. M., Tran, T. K., Clarkin, P., & Korinek, K. (2023). Weathering within war: Somatic health complaints among Vietnamese older adults exposed to bombing and violence as adolescents in the American war. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 165, 111080.

- (2022) Martin MA, Keith M, Pace RM, Williams JE, Ley SH, Barbosa-Leiker C, Caffé B, Smith CB, Kunkle A, Lackey K, Navarrete AD, Pace CDW, Gogel AC, Eisenberg DTA, Fehrenkamp BD, McGuire MA, Meehan CL, Brindle E. SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody trajectories in mothers and infants over two months following maternal infection. ( Frontiers in Immunology, 13 3389/fimmu.2022.1015002 )

- Mohamed, Sumaya Bashir. “Rag Waa Shaah, Dumarna Waa Sheeko: Men Are Like Tea, Women Are Like Conversation: Culturally Congruent Somali Perinatal Care in Seattle, WA: A Feasibility Study.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2022.

- Park, G., Wang, L., & Marwick, B. (2022). How do archaeologists write about racism? Computational text analysis of 41 years of Society for American Archaeology annual meeting abstracts. Antiquity, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.181

- Chapman, R. R., Raige, H., Abdulahi, A., Mohamed, S., & Osman, M. (2021). Decolonising the global to local movement: Time for a new paradigm. Global Public Health , 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1986736

- YouTube

- Newsletter

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 What Is Anthropological Research?

What do anthropologists research.

The short answer is pretty much anything related to being human. We can be more specific by looking at each of the four major fields of anthropology:

Cultural anthropology: this is the cornerstone of anthropology. Cultural, or sociocultural, anthropologists study living peoples. They ask questions about how people behave and why they behave that way.

Biological or physical anthropologists also study living peoples but ask different types of questions that are related to the interaction of biology and culture. Disease, death, evolution, primates are all topic within biological anthropology.

Linguistic anthropologists study how people communicate, both verbally and non-verbally. They look at the structure and evolution of language. They also examine what cultural values are reflected in language.

Archaeologists ask the same types of questions that cultural anthropologists ask, but their dataset is different; they look at the material remains of people in the past.

How do anthropologists decide what to research?

This is a good question, and it has a surprisingly simple answer–they research what they find interesting. It is important that you do the same thing when you are assigned a research project for your classes. Even if your professor assigns a topic, you should be able to come up with an angle to that topic that you find interesting. When choosing a topic, start broadly then through the process of research, begin to narrow the focus. The best way to start is to do some general research to learn about the topic. Wikipedia can be a good source for this first step. The articles on Wikipedia can provide you with keywords to help you focus your research. Once you’ve identified keywords, then you can find academic sources to complete your assignment. Royal Road University has more advice on how to develop a research question. Grand Canyon University also has some advice on this.

Science and Anthropology

There has been a long running debate about the scientific nature of anthropology. Science is a way to gain knowledge about natural phenomena using empirical observation and testing, i.e., experiments (Jurmain, et al 2013). While there are different protocols used in science, it is performed using a set of rules called The Scientific Method (Fancher 2000). The method stresses the need to develop a testable hypothesis, the use of objectivity and rationality, and the circularity of scientific research. This does not mean that science is infallible, but in using the scientific method, particularly with the necessity to have testable hypotheses and tests that are replicable by other researchers, rigorous conclusions are reached.

Within the academy, anthropology is designated as a social science. Social sciences are identified as humanistic, ergo, thought of as “soft sciences” because they focus on

…intangibles and relate to the study of human and animal behaviors, interactions, thoughts, and feelings. Soft sciences apply the scientific method to such intangibles, but because of the nature of living beings, it is almost impossible to recreate a soft science experiment with exactitude…the distinction between the two types of science is a matter of how rigorously a hypothesis can be stated, tested, and then accepted or rejected (Helmenstine 2019).

Helmenstine (2019) further states that the designation is outdated as the “degree of difficulty is less related to the discipline than it is to the specific question at hand.” Difficulty may be not in the performance of experiments but in devising an experiment, which may be harder in the so-called soft sciences.

Peregrine, et al. (2014) claim that the differentiation between science (hard sciences) and the humanities (soft sciences) is a false dichotomy. Within anthropology, both hard science and soft science provide important frameworks for understanding the human experience. Hard science helps us make sense of observable phenomena and soft science provides cultural context for those phenomena. As a holistic discipline it is important for anthropologists to use various methodologies and engage with differing perspectives to understand the human experience.

Anthropology cannot succeed without tolerance for this diversity of approaches…our task…is not to seek definitions of scientific or humanistic approaches but, rather, to implement whatever approach satisfies our interests and helps us to answer our questions (Peregrine et.al. 2012, 597).

Misconceptions About Science

There are some common misconceptions about science that may impede one’s ability to fully understand scientific concepts:

- Science proves things. Proofs are final and binary, which occurs in mathematics and logic. Science uses evidence gathered over time to develop theories, which are explanations widely accepted based on the current available data. Good scientists accept that theories may change based on new data (Kanazawa 2008).

- The scientific method is the only way to do science and it must be done in a lab. While the scientific method is an important tool, it is not the only tool in the researcher’s toolbox. Part of the scientific method as is generally taught in science classrooms is experimentation. It is important to remember that experimentation is only one way to collect data. There are many other ways to collect data, which does not negate utilizing other steps of the scientific method.

- Science is boring . Maybe it is sometimes, but science can be fun and creative. Science employs the imagination and since it explores all observable phenomena, there is usually something that garners one’s interest. Sometimes it is simply a matter of finding that something.

- Science is hard. Perhaps. The language of science, including mathematics, can be intimidating; however, learning about how to do science is the same as learning how to do anything—it’s a process that we learn over time. Patience is key here—sometimes we need to look at multiple sources to gain an understanding.

- Hypotheses and theories are the same thing. Not so. Hypotheses are tentative explanations for a phenomenon. Theories are an accepted explanation based on the testing of hypotheses and well-supported by facts. It can take a long time for a hypothesis to be elevated to the level of scientific theory.

- Scientific knowledge is immutable. Again, not so. Scientific knowledge can and does change as new data are collected and analyzed. If scientific knowledge was immutable or unchanging, then there would never be medical or technological advancements. New or changing knowledge is not bad; the success of humans is reliant on our ability to question and be open to new things. We would not be living in the structures we do today or eat the wide range of foods that we do if not for our ancestors’ openness to new knowledge and change.

- There is always a right answer. Since scientific knowledge can change, answers may change, or we may not be able to determine the ‘right’ answer. This can be especially hard for some people to understand. This may be because the data suggest multiple answers or we simply do not have the ability to collect the data needed to approach a definitive answer. The trajectory of human evolution is a good example of this. Based on current data and data collection methods, paleoanthropologists have developed several hypotheses about how humans evolved. Because we cannot say which hypothesis is right some people claim that human evolution is false. This is a misunderstanding as to the nature of science. The ‘gray’ area, the area of uncertainty, is not inherently bad. It drives further research, and we need to be open to the fact that sometimes ‘this is what we know right now’ is okay.

- Science is anti-religion. While it is true that many scientists are atheists, it is also true that many scientists follow religious belief systems. Scientists prefer to leave religion outside of the science classroom because the subject matter is out of the purview of what they can research because “supernatural explanations are less likely to generate testable claims” (Brickmore et.al. 2009).

Science and Culture

Science does not operate within a vacuum. It operates within cultural systems, which, unsurprisingly, influences the way science is done. Science, as is taught in most schools in industrial nations, started in Renaissance Europe, which itself was heavily influence by knowledge gained from Islamic societies. However, this empirical approach is not the only way to study nature or observable phenomena.

Cultures from all regions of the world have developed a complex view of nature, rooted in their philosophy, which has led to their understanding and explanation of the natural world. The traditional knowledge of non-European cultures is the expression of specific ways of living in the world, of a specific relationship between society and culture, and of a specific approach to the acquisition and construction of knowledge (Iaccarino 2003, 223).

It is beyond the scope of this class to explore all the various ways cultures understand the interaction of culture and environment or to investigate the myriad of ways knowledge is constructed. Because anthropology is embedded within the Western practice of science, that approach is the focus of this chapter.

Society’s Influence on Science

As cultures and societies change to meet new needs, so does science. For instance, national interests influence the trajectory of science. World War II influenced research into atoms, leading to the development of nuclear weapons and nuclear medicine. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic led researchers to investigate not only a vaccine for the virus, but its origins and epidemiology.

Funding to practice science, e.g., laboratory equipment, salaries, etc., most often comes from social organizations. Both government and private organizations support scientific research. In the United States, the National Science Foundation, National Institute of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control are a few governmental organizations that provide grants for scientific research. The Wenner-Gren Foundation, Tinker Foundation, and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation are examples of private organizations that provide science research grants. Sometimes the organizations direct the focus of research by providing grants for specific types or areas of research, such as The Whitehall Foundation, which provides grants for research in the life sciences, or The Leakey Foundation, which awards grants for research about human origins. While funding agencies can influence what scientists research, it cannot determine the conclusions of the research.