We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

A link to reset your password has been sent to your email.

Back to login

We need additional information from you. Please complete your profile first before placing your order.

Thank you. payment completed., you will receive an email from us to confirm your registration, please click the link in the email to activate your account., there was error during payment, orcid profile found in public registry, download history, what to do if you are thinking of changing your phd topic or field.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 18 June, 2022

Completing your PhD research project is often a lengthy process that will at some stage almost certainly involve changes in your initial plans. The proposal you submitted when applying may have been written more than nine months before even starting the PhD. Changes are the norm, but the degree of change can vary considerably. This article outlines some considerations and actions to take if you are contemplating changing your topic or even your field.

A. When you need to consider the type of PhD you are doing

An initial factor to consider is the type of PhD you are writing, whether it is producing a number (usually three) of related articles which together form the thesis or the development of a thesis/dissertation ( monograph ). Projecting forward three possible articles is demanding, and plans may therefore change quite late in the PhD process if you are taking this option.

Suggested action

Regardless of the degree of change, the best first step to take is to seek the advice of your supervisor/advisor , who will be best placed to advise you on what you need to do and the extent of the changes to make.

B. When your learning evolves as you progress in your PhD

In some systems, such as in the American style of PhD programmes , it is common to write and defend a more substantial proposal, called a Prospectus , at the end of the first year of studies. The first year on these programmes often covers issues related to methodology at the PhD level, and your own research is almost certainly going to change in some way as a result.

The first two years are going to involve considerable reading around your chosen topic. Searching for answers to your initial research questions will reveal that some have already been answered. It is also likely that you will make discoveries suggesting additional or even alternative research routes that can be pursued. They add the novelty factor to your research, which is perhaps the most prized attribute of a research project. These new openings may lead you to modify the direction of your initial plans if you see more fruitful possibilities to make a contribution.

Suggested actions

In all these scenarios, it may be possible to tweak the research question(s) to:

- Open up more possibilities.

- Narrow down their scope to be more readily answerable.

- Slightly shift direction to find a new area to explore.

Again, seeking advice from your supervisor is best here. Consulting with second supervisors or other professors with whom you share interests will also often help.

Note : Be aware that acquiring too many opinions and advice can also become confusing if you receive varying or contradictory answers.

C. When more serious scenarios are involved with your PhD

Sometimes, changes become necessary because of events outside of your control that impact your initial plans. This could be because of:

- Scientific developments in your area of expertise

- Finding new research which covers a similar area to your own

- Serious repercussions resulting from external factors, such as a pandemic or unexpected conflict

Sometimes, other factors can also prove more challenging: the chosen type of data may not become available or may not yield the results you were expecting or hoping for .

To address these issues, it may still be possible to make small changes to your central research question(s), which will generate new information. Perhaps you can still change the data source, adjust your methods slightly and carry out the research regardless.

Alternatively, you may be able to adopt a different theoretical approach to the same problem, or bring in a different approach from an outside discipline.

As always, your supervisor and other academics may be able to offer good advice .

D. When you are feeling disillusioned or demotivated about the PhD

Sometimes, you might just lose motivation , feel bored with the studies or feel that the research is going nowhere.

In this case, before you decide to take any drastic decisions, it might just be a good idea to get some distance from your studies, take a break and do something completely different. Then, when you’re feeling rested, come back to the research with fresh eyes and reassess the situation. (If this is the case, you may also find this article useful: What to do when you Lose the Motivation to Complete your PhD )

In research, change is to be expected : ideas develop, research pushes forward to open new doors… or sometimes, closes them. If you encounter a problem, it does not necessarily mean you have to make big and drastic changes to your overall PhD project. Often, a minor amendment here or an infinitesimal tweak there will be enough. Whatever you choose to do, always discuss your concerns and plans with your supervisor to get the perspective and guidance you need to move forward in the best and most efficient way possible.

Maximise your publication success with Charlesworth Author Services.

Charlesworth Author Services, a trusted brand supporting the world’s leading academic publishers, institutions and authors since 1928.

To know more about our services, visit: Our Services

Share with your colleagues

Related articles.

Choosing the Right PhD Topic

Charlesworth Author Services 18/06/2022 00:00:00

Finding the Right Place to do your PhD

Charlesworth Author Services 25/05/2021 00:00:00

How to develop an excellent PhD Supervisor relationship

Charlesworth Author Services 24/04/2020 00:00:00

Related webinars

Bitesize Webinar: Effective paper writing for early career researchers: Module 1: Writing an effective PhD thesis

Charlesworth Author Services 02/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize webinar: Effective paper writing for early career researchers: Module 3: The right mindset for academic paper writing

Bitesize Webinar: Effective paper writing for early career researchers: Module 4: How to sell yourself as a researcher

Bitesize Webinar: Effective paper writing for early career researchers: Module 5: Key team working skills

Importance of writing the Scope and Delimitations of your study

Charlesworth Author Services 17/03/2022 00:00:00

Novelty effect: How to ensure your research ideas are original and new

Charlesworth Author Services 12/01/2022 00:00:00

Developing and framing a Research Question for different types of studies

Charlesworth Author Services 23/03/2022 00:00:00

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Of monsters and mentors: PhD disasters, and how to avoid them

Despite all that’s been done to improve doctoral study, horror stories keep coming. here three students relate phd nightmares while two academics advise on how to ensure a successful supervision.

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

For all the efforts in recent years to improve the doctoral experience for students, Times Higher Education still receives a steady supply of horror stories from PhD candidates. To the authors of such submissions, the system appears, at best, indifferent to them and, at worst, outright exploitative. Here, we present three such examples – all of whose writers, tellingly, feel the need to remain anonymous, given the power dynamics involved.

Perhaps such tales are inevitable. Perhaps, even with the best will in the world, there will always be supervisor-supervisee relationships that just don’t function; expectations that, however heartfelt, just aren’t realistic; supervisors who just can’t find the time to give the kind of detailed supervision that they would like to give, and that students feel they need.

But perhaps there is still more that could be done to ensure that this most intense and crucial of academic relationships doesn’t end up on the rocks. In that spirit, two academics with strong views on the matter – one from science and one from the humanities – set out how they think the supervisory task should best be approached. Their guidance may not amount to a stake through the heart of the PhD horror franchise: as B-movie history amply demonstrates, good advice is not always heeded. But the exposure of the problems to further sunlight may at least slow the drip-drip of blood on to the doctoral carpet.

I had never felt so helpless in my life. The university wholly and blindly supported my supervisors, ignored my concerns and suggested, again, that I was making things up

When I was offered a fully funded doctorate in a UK environmental science laboratory, I was delighted and accepted instantly. I assumed that the experience of working in an international environment and the many transferable skills that I would learn would be a stepping stone to an exciting career beyond the academy. Little did I know that what I had signed up for would destroy not only my career plans but also my passion for the subject, my ambition and my self-confidence.

My supervisors turned out to have limited knowledge of the topic that they had so glamorously advertised, and the university lacked the facilities and machinery that I needed. Left with precious little guidance, I was obliged to work with methods that would do very little to enhance my career. An obvious solution was to set up an external collaboration, but my supervisors were reluctant to sanction it. They didn’t seem to want to share the glory with anyone else, but the environment that they created meant that there was never likely to be much glory to share anyway.

It didn’t help, either, that I am female. My male supervisors, in a male-dominated field, constantly made belittling remarks that they would never have made to a male student, remarks that led me to doubt my own capabilities. My doctorate became a living nightmare, and, after a year of ineffectively trying to solve the issues directly with my supervisors, I decided to take things further.

Because the head of my department had just resigned, I sought help from the university’s students’ union. But joint meetings with a union representative and my supervisors seemed to go nowhere, culminating in accusations that I was “making up” the issues. The union subsequently managed to arrange a meeting with the head of the graduate school, but, nearly six weeks after our meeting, he deemed my case too complex and I was ultimately told to solve my issues with my supervisors directly!

I had never felt so helpless in my life, and I was amazed at how unconcerned the university apparently was about student well-being. After months of more meetings with my supervisors and the union, I was contacted by the departmental postgraduate tutor, who expressed “concern” about my progress. This offered me a ray of hope. However, as usual, things got worse rather than better. The university wholly and blindly supported my supervisors, ignored my concerns and suggested, again, that I was making things up. I was offered an additional female supervisor, but, while welcome, that would have done little to solve the other issues.

I was given an ultimatum. I had two weeks to decide if I wanted to continue with my PhD and “accept” things as they were. The alternative was to leave – without any form of diploma or certificate for my two years of work (which included the publication of a first-author paper).

My last throw of the dice was to contact my funding body. However, my entire funding had already been transferred to my university, so there was little that it could do to help me. Thus I had no other choice but to quit and to watch as the university swept my case under the carpet, documenting my withdrawal as the result of “personal and health issues”.

Although the experience has cost me a lot, it also taught me a considerable amount. I learned to be wary of offers that seem too good to be true. I learned not to take my rights for granted. I learned the value of having expectations, commitments and offers put down in writing. I learned to trust no one.

I also learned a lot about how higher education institutions function. I discovered that they will do whatever it takes to cover up their own mishaps to save their reputation, even if it comes at the cost of destroying a young person’s career.

Anecdotally, cases similar to mine are becoming increasingly common. In recent months, there have been multiple ongoing cases at my former university, including more withdrawals. However, the university just recruits more students to make up for the losses.

It is well known that PhD students are widely seen by academics as a cheap workforce. But to be treated with such little respect by the people who are supposed to foster your career and help you to succeed is just not right in any workplace.

The author prefers to remain anonymous.

If you want to supervise and mentor with integrity and thoughtfulness, it is ultimately up to you to decide to do so, and to make the rules. You cannot assume good ethics on the part of your department

The power that you as a supervisor have over a student or postdoc is immense. Your actions, whether they are kindnesses, temper tantrums or intimacies, have the potential to shake up trainees to a much greater degree than their actions can affect you. And, most of the time, trainees have no way to solve conflicts with you if you won’t negotiate. Hence, it is your responsibility not to abuse your power.

But it takes integrity and clarity not to do so. Doctoral supervision is challenging. Your first difficulty is in acknowledging and getting beyond unrealistic expectations of your students that you might not even know you have. In science, new supervisors often imagine a lab filled with idealised workers: miniature versions of themselves, who churn out data and submit manuscripts. So when their charges don’t do exactly what they expect, they feel frustrated.

You might also observe that other supervisors allow their people to flounder, or even to fail. And even though you don’t want that, you have never had the lessons in personnel management that might ensure it doesn’t happen. Academic departments and institutions may or may not provide support to guide supervisors and students in building effective relationships.

If you want to supervise and mentor students with integrity and thoughtfulness, it is ultimately up to you to decide to do so, and to make the rules. You cannot assume good ethics on the part of your department. Nor can you assume, as a scientist, that your research group will passively absorb your good intentions. You must consider what you haven’t been trained in graduate school to consider: your own ethics, morals and sense of justice. Accept what institutional help exists, but if the policies at your institution render trainees expendable, you must develop the courage to stand up to power.

And then you build a framework for your students in which your ethics, rules and expectations are clear. For example, if you want your people to know that you are concerned with their professional futures, don’t let them drift without guidance. Evaluate each person regularly, and give feedback and compassionate criticism – not just on results but also on communication skills, presentation skills, time management and other characteristics of a successful professional. Keep notes on your meetings and follow up on what you and the trainee have discussed. Check in frequently and provide multiple opportunities for discussion and interaction. Be present.

Authorship and project choice are other vital areas where your policies can reflect your intentions to have a collaborative rather than a competitive climate. How are projects chosen? Do you actively foster collaboration, putting new people to work with more established lab members in a way that both parties benefit from, and will you continue to guide and monitor those collaborations? Do you intend to compete with your own trainees when they leave, or will you allow them to take their projects with them? Who writes the papers? How is authorship decided? Will you protect your people in authorship disputes with collaborating groups, or will you sacrifice a trainee to keep last authorship for yourself?

Create a group manual, with protocols, policy and helpful information, being specific about whatever you consider to be important for students to know. Include information about where trainees can find help if they have a personal or project issue – including problems with you.

You also need to be prepared to deal with the inevitable conflicts between lab members. Learn not to fear it, as that fear can mould you into a little dictator and keep you from understanding what people need. Have a process to work through conflicts (look up “interest-based conflict resolution”), as fair process often carries more weight with people even than achieving the outcome they wanted. Explain that process to your students, too: conflict resolution is one of the most valuable skills you can pass on. Don’t run from emotions – research is an emotional business – but learn to control your own emotional responses so that they don’t interfere with your communications.

Talk about ethical behaviour, and model that behaviour. If you expect your people to meet deadlines, you should be on time for meetings and return manuscripts and phone calls predictably. If you hear someone making a racist or sexist remark, correct the person: doing nothing will send the message that such behaviour is OK by you.

It is also important not to let yourself, or anyone else, become isolated. Make a point of introducing your students to your former students and postdocs – as well as to experts in their fields – when they visit or when you encounter them at meetings. Model the value of mentors by having mentors yourself, for personal and professional advice. Have the confidence to encourage trainees to have other role models and mentors, especially if they move into a project area in which you aren’t expert: having mentors is the start of building a web of relationships that will support trainees all through their lives.

But students must also be activists. Some supervisors eat their young, and some institutions allow it. As a student, you have the greatest level of control before you accept a position, so look for a place where you are respected and can do the work that you believe in. Ask other students questions about the scholarship and mentorship of particular supervisors before you make the decision to sign on. Once there, find role models, and get to know your community. The more you are integrated with others, the more people there are to help should your relationship with your supervisor or your project go badly.

It is unfortunate and unfair that students are not always protected, and that leaving might be the only solution to a toxic situation, but that is the harsh reality. So, as a student, doing all that you can to ensure that you will be appreciated and fulfilled in the position you accept is worth the effort.

Kathleen Barker is clinical assistant professor at the University of Washington School of Public Health. She is the author of At the Helm: Leading Your Laboratory (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

PhD students are often made to feel like they are a huge burden on their supervisors, and they are frequently ignored and unsupported

Tom sent his supervisor a chapter of his PhD thesis to read six weeks ago. He can’t start on the next chapter until he receives feedback on what he has already done. But he has had no response despite chasing up his supervisor – with whom he gets on well personally – several times. Indeed, he has not even received an acknowledgement of his email. And he knows that when he does finally receive a reply, there will be no mention of the delay, let alone an apology. He knows that because this has all happened before.

But this time the situation plays out even more egregiously. After Tom has waited for two more weeks, he finally hears back – a full two months after his initial email. But his supervisor has checked only the first two pages and the last page of his chapter, ignoring everything between.

Tom is frustrated, but he thanks his supervisor for the feedback and does not challenge her over the delay. How can he when he is entirely dependent on her to get him through the PhD submission process and to supply a good reference for subsequent job applications? Besides, sustaining a complaint would come down to his word against hers – and she is senior and well respected in the department and the university. No one would believe him. And even if they did, would it really be worth the hassle of getting another supervisor allocated to him in his final year – and, in the process, acquiring a bad reputation in the department for being the one who “made a fuss”?

So Tom soldiers on. Eventually, after much delay, he finishes his thesis. But is it ready for submission? He points out to his supervisor that he does not believe that the thesis has been checked properly, but she tells him to stop worrying, to take responsibility for his work and to be confident in its quality and in his ability to defend it. So he takes the plunge and submits. But he spends the next two months worrying that he might fail, rendering the past four years of hard work a complete waste of time.

This is a true story. And it takes only a few cursory searches of online PhD forums to see how common such scenarios are. PhD students are often made to feel like they are a huge burden on their supervisors, and they are frequently ignored and unsupported. Hence, even the most toxic student-supervisor relationships often persist long beyond the point of dysfunctionality, sometimes leaving the student with mental health problems.

I believe that this happens primarily because supervisors’ responsibilities are rarely clearly defined and because supervisors are not accountable to anyone for carrying them out. So I make the following recommendations:

- Training for supervisors must be compulsory

- Supervisors must be held accountable to someone senior in the department, and PhD students should be made aware of who that is

- Supervisors must be required to respond to their PhD students’ emails within three days, barring any type of leave

- Supervisors’ responsibilities need to be outlined clearly in a handbook that is available to both supervisors and students. It should also be made clear to students how much of their supervisors’ time each week or month is allocated to giving them feedback so that they are not made to feel like a burden

- Students must be assigned a mentor who is not close to their supervisor or in the same research team – ideally in another department altogether. This person can help to alleviate concerns and act as an intermediary when necessary

- There should be an anonymous procedure within each department that PhD students can use to complain or give feedback about their supervisor

- Supervisors should be formally encouraged to ask their students annually how they could better support them. This should be part of supervisors’ yearly appraisals.

In the absence of such steps, such stories as the one above will continue to write themselves over and over again.

If a relationship works well, it can be life-changing for the student and deeply rewarding for the supervisor. Supervising PhDs, I have been directed along paths that I would not have discovered otherwise

There is no doubt in my mind that the best part of being an academic over the years has been supervising PhD students. I cannot remember how many I have supervised, but the number runs to well over 80, and I have examined even more than that.

I am still in touch with many former students and examinees, and have been delighted to follow their careers wherever they are in the world. If a relationship between supervisor and postgraduate works well, it can be life-changing for the student and deeply rewarding for the supervisor. I have learned so much from supervising PhDs, and have been directed along new paths that I would not have discovered otherwise. There have been occasions when a student would arrive in my office with a bag full of books that he or she felt I should read: a living demonstration of the fact that it is not always the supervisor who provides all the bibliographical information.

I always start by telling students three things: that I will read every word they write in draft and then in final copy; that if they can get me to approve the thesis, given how tough I am going to be with them, then they have a very good chance of getting it past the examiners; and that they should not be discouraged if they find that their work is shifting direction after a few months. Writing a humanities PhD is an organic process, and if ideas have not started to develop by the end of the first year, then something is going wrong. Supervisors are particularly important at this stage, to provide reassurance and to help the student move forward.

Supervising PhDs is rewarding because you can see the process of intellectual development unfolding before your eyes. But it is also an intensely time-consuming task. All the various calculations of hourly allocation for supervision are absurd: if you are going to supervise properly, then you have to be prepared to spend hours reading drafts and then talking to the student.

There are some supervisors who do not write anything on drafts, preferring to correct only a final version. I find this ridiculously unhelpful. The whole point of reading drafts is to give proper feedback, and in the case of international students this kind of detailed reading is essential. Academic writing courses help, but careful editing by a supervisor is vital.

Nor should a supervisor’s detailed corrections focus on content alone. They also need to address spelling, punctuation, style and structure. Sometimes I have proposed radical structural changes, such as moving material from a conclusion into the introduction and vice versa. Such suggestions can be responsibly made only after you do a final read-through of the whole thesis – and that final reading is essential because although you may have read individual chapters or sections over several years, only the student will have a clear idea of how they want it to fit together.

It is also important to provide a written summary of general points after reading each draft. I learned early on that trying to do this verbally does not work because a student is often anxious and so does not take everything in. An email with bullet points works best. It is also important to balance criticism with praise, so the summary should start out with something positive before moving on to the “however” part. But all criticism, however negative, should be presented in such a way as to offer solutions and to help the student with the next stage in writing.

One of the problems facing supervisors in the UK is that the hours they put in are never adequately acknowledged by university management. This is because the UK has had to try to catch up with the kind of structure for doctorates that operates in US universities, and often PhD students have been tagged on as extras to someone’s academic workload. In the humanities, there have also been (and remain) some curious ideas about the need for a supervisor to be a “specialist” in exactly the same area as the student. Not only can this impose undue pressures on specialists in popular fields, it is also conceptually misconceived. Supervision should take both student and supervisor down relatively unexplored paths.

When it comes to choosing an examiner, practices vary widely. I have heard colleagues state firmly that the student should have no input, but I consult with mine because it is important to find out whether they have been in contact with any potential examiners. Also, despite clear guidelines, some universities still do not appoint anyone to chair the viva, which means that if a student feels hard done by, there is no independent witness. That only makes the choice of examiner even more important.

I don’t understand why supervising PhDs should be seen as a chore, rather than as a unique opportunity to engage with the brightest minds of younger generations. My research would be so much poorer without the help that I have received, directly and indirectly, from my doctoral students.

Susan Bassnett is professor of comparative literature at the universities of Warwick and Glasgow.

The degree was not awarded. Yet years later I discovered evidence that the viva had been deliberately biased. It’s a serious matter – so how would the university respond?

Some students cheat. That’s clear from numerous articles in the press. But is this a one-sided view? How often is the examiner’s performance questioned or subjected to independent scrutiny? For postgraduates in particular, this is no trivial matter: any bias or lack of honesty in an examiner can waste years of the candidate’s life and can degrade trust in the system.

My experience may not be typical, but it’s certainly an eye-opener for any postgraduate who assumes that the viva examination will be automatically fair and above board.

After an MSc, I completed four years of doctoral research at a major UK university. The results were formally approved by the relevant research council and were published as a series of seven papers in major, peer-reviewed journals.

Before the viva, I’d queried the choice of examiners, owing to perceived bias, but was overruled.

The degree was not awarded: the examiners claimed that none of my seven papers had deserved publication – even though they had satisfied a total of 14 independent referees. The examiners had decided all 14 were wrong.

So what did I do? I got on with my life. Years later, though, I discovered that my papers are cited in the examiners’ own publications: that is, the examiners had used them as valid references to support their own work. Incredibly, some of these papers had been referenced before my viva. Clearly, this was perverse, dishonest and highly unprofessional conduct: the viva had been deliberately biased. It’s a serious matter – so how would the university respond?

I sent it five of the examiners’ publications that cite my papers, together with a copy of the examiners’ signed report. I asked for acknowledgement that the viva had been biased. But the university declined to comment; it said the complaint was “out of time”.

Where there is evidence of malpractice, it should not matter when the viva was held: bias was deliberate and obvious, and the university could have followed up. Hiding behind process is a deeply inadequate response to such a blatant and egregious case. Nowadays, so-called historic cases of injustice and abuse, some from many decades ago, are being recognised and investigated. So why is corruption in education treated differently?

Examinations might be more equitable if, before the viva, candidates were officially entitled to raise concerns about their examiners – any concerns being addressed independently of the college or university. Such adjudication might seldom be needed, but it should still be in place. Examiners, after all, are people. And people – from students to presidents – do not always possess the levels of integrity and honesty that we naively expect of them.

Candidates should not be expected to accept a particular examiner if they can offer valid reasons for not doing so. And any university that seeks to impose a disputed examiner should be asked to reconsider its definition of fair play.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Related articles

PhDs: ‘toxic’ supervisors and ‘students from hell’

How should universities handle breakdowns in PhD student-supervisor relationships?

Reader's comments (11)

You might also like.

Biden breaks silence to condemn US campus ‘chaos’

President says ‘order must prevail’ after police clear UCLA encampment

Third of UK students say they might drop out due to money worries

Apparent turnaround in nation’s finances has done little to alleviate financial pressure on students, according to new poll

How best should US universities respond to campus protests?

Tough decade-old experience with police violence taught California universities the value of restraint, though divisive politics may already be straining its ability to keep its ideals

No degree and little hope for protesting students behind bars

Student leaders protesting their university’s failure to accredit their degrees find themselves in Papua New Guinea jail, after ‘opportunist’ torches vehicles

Featured jobs

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NATURE BRIEFING

- 13 July 2022

Daily briefing: How to bounce back from a PhD-project failure

- Flora Graham

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here

Wild birds are sold for food at a market in Vietnam. Credit: Hoang Dinh Nam/AFP/Getty

Where livelihoods depend on wild species

Billions of people worldwide rely on at least 50,000 species of wild plants and animals for food, medicine and income . Dozens of authors, including individuals with Indigenous and local knowledge, were involved in a major attempt by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) to quantify how much humanity relies on nature. The report highlights many examples of wild species being used sustainably, and recommends ways to support and replicate those methods. Critics say there are significant gaps in the evidence and question whether some cases are as sustainable as they seem. The report’s authors acknowledge those gaps but say they shouldn’t slow efforts to introduce better practices.

Nature | 5 min read

Reference: IPBES Sustainable Use Assessment

DeepMind AI learns physics like a baby

Researchers at Google-owned company DeepMind have created an artificial intelligence (AI) that knows about as much physics as a 3-month-old baby. The team trained the system on simple videos until it could predict patterns such as solidity (two objects do not pass through one another) and continuity (objects do not blink in and out of existence) . The research makes an interesting contribution to the nature–nurture debate about how infants learn to see the world, say psychologists Susan Hespos and Apoorva Shivaram in the accompanying News & Views article . The results suggest that experience “is an important contribution to the learning process, but it is not the whole story. The complete story requires some built-in knowledge.”

Nature | 4 min read & Nature Human Behaviour | 5 min read

Reference: Nature Human Behaviour paper

The number of beagles, bred for research purposes, that are looking for homes after animal welfare violations led to the closure of a breeding facility in Virginia. ( The New York Times | 6 min read )

Where I work

Hemu Kafle is an environmental scientist and founder of the Kathmandu Institute of Applied Science. Credit: Monika Deupala for Nature

With no research institute in Nepal equipped to support her drought research, environmental scientist Hemu Kafle helped to establish a new one. She is pictured here with one of the low-cost meteorological stations that she and her colleagues designed and developed at the Kathmandu Institute of Applied Sciences. ( Nature | 3 min read ) (Monika Deupala for Nature )

Features & opinion

Bounce back from a phd-project failure.

Science is riddled with stories of getting scooped, data glitches and funding crises — which can feel particularly acute for PhD candidates who are racing against time to earn their degrees. Five researchers talk about the hurdles they faced and how they overcame them .

Nature | 11 min read

‘Why I advocate for abortion access for all’

“I know in my heart that I would never have become a scientist had I not had my abortion,” writes palaeoecologist Jacquelyn Gill. She never regretted her decision, she says, but she has carried a lifetime of grief because of unnecessary barriers that made the experience more invasive, expensive and traumatic than it had to be. She shares her deeply personal story to illustrate that “reproductive justice matters to science not only because scientists get abortions, but also because so many scientists are well-positioned to use our privilege and roles as trusted experts to de-stigmatize and support abortion rights for everyone”.

How BA.5 is reshaping the pandemic

The rise and rise of the BA.5 variant of SARS-CoV-2 — a sub-variant of Omicron — raises questions about how we will deal with a pandemic in which many more people get COVID-19 or experience repeated reinfections . Focusing on the United States, where the variant is spreading quickly, science writer Ed Yong debunks some false assumptions. He also urges US leaders to tighten up the country’s slackening health-protection policies against COVID-19. “This is what ‘living with COVID” means’,” writes Yong. “A continual cat-and-mouse game that we can choose to play seriously or repeatedly forfeit.”

The Atlantic | 10 min read

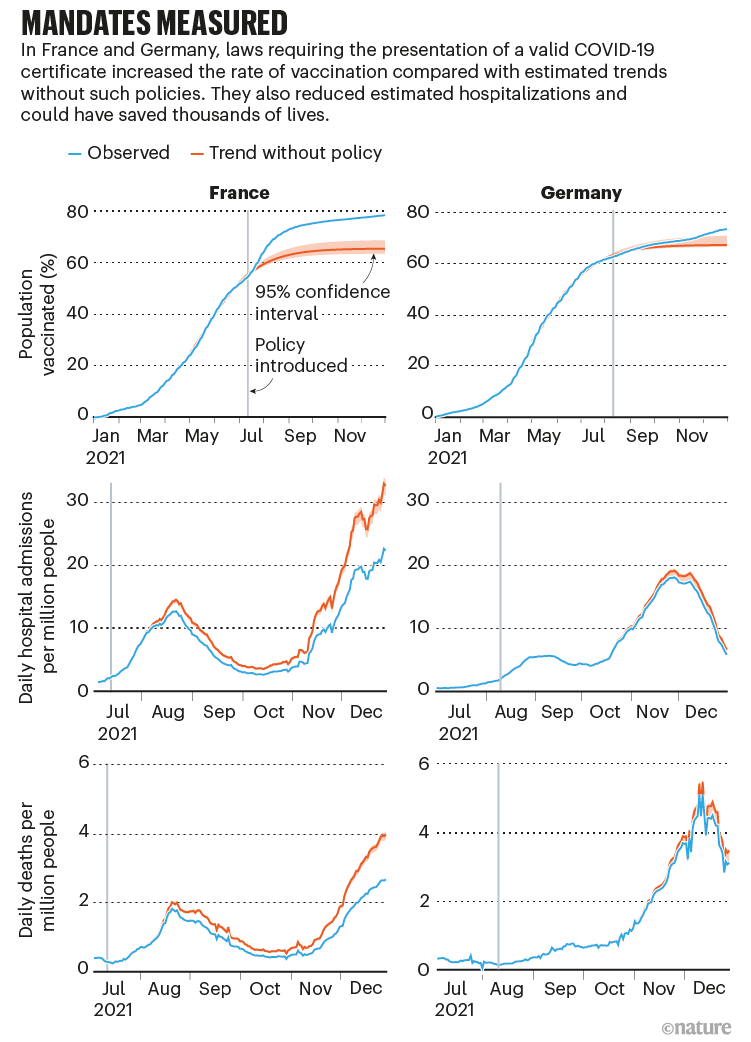

Infographic of the week

Source: M. Oliu-Barton et al. Preprint at Research Square https://doi.org/h4s5 (2022).

Public-health researchers have found that the ‘measure of last resort’ for increasing vaccination rates — legal interventions such as vaccine mandates and passes — increased vaccine uptake and reduced hospitalizations and deaths . But scientists say it is hard to accurately quantify how obligatory vaccination policies affected social exclusion, loss of public trust or inequitable outcomes. ( Nature | 13 min read )

See more of the week’s key infographics, selected by Nature ’s news and art teams.

QUOTE OF THE DAY

“we have a climate crisis going on that we’re trying to respond to, but then we also have a moral crisis that we can’t ignore.”.

Marine biologist Brendan Kelly is among the climate researchers facing a loss of crucial climate data as the war in Ukraine severs partnerships between researchers inside and outside Russia. ( Nature | 7 min read )

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01977-5

Today, I took a break from gazing at every iteration of the high-resolution images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope to enjoy some of the ways people are remixing the pioneering pics. Software developer John Christensen made a tool to compare Webb images to Hubble Space Telescope images (and an anonymous person made this silly response to all the Web–Hubble comparisons). The European Space Agency released the official Webb GIFs we didn’t know we needed, and the journal Antiquity made my favourite Webb meme so far .

Send me something silly about the Just Wonderful Space Telescope, tell me if this is funny or let me know what you think about this newsletter. Your e-mails are always welcome at [email protected] .

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Nicky Phillips

Related Articles

Daily briefing: Spectacular first images from the Webb space telescope

Daily briefing: COVID variants spotted early in sewage

Daily briefing: New Zealand’s bold plan to oust invasive predators

Daily briefing: Pig-to-human transplant trials inch closer

W2 Professorship with tenure track to W3 in Animal Husbandry (f/m/d)

The Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Göttingen invites applications for a temporary professorship with civil servant status (g...

Göttingen (Stadt), Niedersachsen (DE)

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

Postdoctoral Associate- Cardiovascular Research

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Faculty Positions & Postdocs at Institute of Physics (IOP), Chinese Academy of Sciences

IOP is the leading research institute in China in condensed matter physics and related fields. Through the steadfast efforts of generations of scie...

Beijing, China

Institute of Physics (IOP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS)

Director, NLM

Vacancy Announcement Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health DIRECTOR, NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE THE POSITION:...

Bethesda, Maryland

National Library of Medicine - Office of the Director

Call for postdoctoral fellows in Molecular Medicine, Nordic EMBL Partnership for Molecular Medicine

The Nordic EMBL Partnership is seeking postdoctoral fellows for collaborative projects in molecular medicine through the first NORPOD call.

Helsinki, Finland

Nordic EMBL Partnership for Molecular Medicine

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

What nobody tells you about doing a PhD…

Jul 29, 2023

When you start a PhD, you’re thrown into the deep end. Unlike starting a new job, there’s often no onboarding process to guide you through. You’re lucky if you even receive methods training. If your PhD is anything like mine, you’ll be shown your desk on day one and told to get on with it.

Now, that’s part of the PhD journey; figuring out what you need to be doing and then actually doing it. It requires self-motivated learning and exploration. Over time, by asking the right questions (of yourself and others), you start to build up a picture of what indeed you need to be getting on with.

But there are some things I found out the hard way, and which only really became apparent to me after I finished my PhD and when I started working with and guiding other students in my role here at The PhD Proofreaders. These are the things that no one ever really tells you about doing a PhD.

PhDs are Janus-Faced

On one hand, they can be very solitary endeavours, defined by countless hours spent reading and writing alone, many of which are tinged by feelings of doubt and uncertainty, with the door seemingly always open for imposter syndrome to derail or devalue what’s going well.

On the other hand, they’re communal endeavors. As a PhD student, what you’re feeling and navigating isn’t unique. You’re part of a web, a community, a network; part of something much, much bigger. While every PhD is, by definition, unique, the ups and downs, and the emotions that accompany them, are very much not. The problem is that, too often, it’s easy to forget this. You can think you’re unique in feeling the way you do, in struggling with the things you struggle with, and in feeling the joys and victories that you do.

What’s easier? Doing a PhD while feeling isolated, working in a silo of one, feeling the weight of the world on your shoulders, and feeling just awful because of it. Or, doing a PhD knowing that there are others around you in the same boat? Knowing that there are others out there going through the same ups and downs, feeling the same pains and joys, each managing the unique challenges that come with the PhD journey. Each crossing their fingers and hoping for the best.

No One Else Knows What They’re Doing Either

At least some of the time, and to varying degrees, most (perhaps all?) PhD students feel like impostors. The more convinced we become of our own ineptitude, and the brilliance of others, the less motivated we become to do the work. Why bother, our brain tells us, if it’s never going to be good enough?

Part of the challenge of doing a PhD is learning to manage and ultimately silence this inner impostor.

You might think that the best approach is to remind ourselves of our strengths and talents. But that will only take you so far.

Instead, you should accept those feelings of doubt and remind ourselves how refreshingly normal and unproblematic they are. These thoughts aren’t offering any concrete evidence of our impending failure or evidence that we’ll never have what it takes to reach the lofty heights of wherever it is we’re headed.

Instead, they’re a reflection of the fact that no one really has it all figured out. You may look to those around (and above) you and wonder how they manage to glide through professional life with such ease, but on the inside, they’re likely feeling as confused and unsure as you.

To put it differently, if we feel resigned to the fact that we will always be children in an adults’ world, it can be helpful to remind ourselves that there aren’t really any true adults in the first place. No one has it ‘figured out’, and the door to self-doubt and critique is always open.

There are lots of competent people – including you – doing their best to make good decisions, say the right things, and put things in the right order. But they’re doing so in spite of their own respective incompetences, not because of some explicit brilliance.

So if you’re feeling like an impostor as you try to navigate through the PhD – and let’s not forget the enormity of such a journey – then everyone else around you likely feels like one too.

The PhD is an act, where all the performers are giving it their all, hoping that they don’t fluff their lines.

This is not a normal blog subscription

Each week we send a short, thought-provoking email that will make you think differently about what it means to be a PhD student. It is designed to be read in thirty seconds and thought about all day.

You’ll Run Out of Time

I was talking with a friend earlier this week about the progress they were making on their PhD. With a few months to go, they were panicking about whether they would have everything done in time.

Notwithstanding the fact that they’re a brilliant student, and have so much of the PhD puzzle already in place, it did get me thinking.

I remember the feeling well; as the deadline loomed, my fear and panic rose. Would I really get everything done? It didn’t seem possible.

It made me wonder how many others feel the same way. Did most students, nearing the end of the journey, start panicking about whether there was enough time left?

I suspect it’s common to feel this way as the end of the PhD comes into view. It’s natural when you think about it; so many years of your life are leading up to this moment. It’s to be expected that panic sets in.

In reality, I didn’t get it all done in time. Not really. There were so many loose ends with the thesis; some I knew about, others I didn’t. I came up against the deadline and had to submit, even in spite of the incompleteness. And even in spite of that – in spite of what, for many of you, may seem like a living nightmare – everything turned out okay.

There are three points to take away from this. The first is that the thesis will always be unfinished. That’s sort of the point – nothing in life is perfect, not least research. The key is avoiding the perfectionist trap.

The second is that, as you near the end, you need to have faith in all the work you’ve done prior to this point. You haven’t been living under a rock; the final stages of a PhD represent the culmination of years of hard work. Have faith that you’ve already done most of the work, and that all of the decisions you’ve made thus far were made in good faith.

The third is perhaps a more contentious one. Statistically speaking, it’s likely that your examiners will require you to make at least minor corrections (major corrections, in my case). In some ways, writing the corrections was the easiest stage of the PhD. It’s the only time in the whole process where you have someone telling you exactly what needs to change, and where. I found it quite cathartic.

Your PhD will never be really finished, and that’s okay. There’s no magic lightbulb moment where you think, ‘ah-ha! I’ve done it!’. You do your best, you embrace imperfection, and you submit the best you can, having faith that it’s good enough. Seen this way, deadlines are nothing to be scared of. Instead, they’re there to be embraced.

Making Mistakes Doesn’t Make You Stupid

The real skill in the PhD is not the avoidance of mistakes but rather the ability to be kind to ourselves once they’ve happened.

To be human is to make mistakes, and to pretend otherwise is to fall into the perfectionist trap; aiming unrealistically high and chastising yourself when you inevitably fall short.

If we’re not careful, we can expect too much of ourselves and expect the path between where we are now and where we need to be, whether that’s an experiment, a chapter, or an exam, to be traversed flawlessly, without incident.

This is dangerous (and wishful thinking).

Similarly, when we do make mistakes – remember, they’re inevitable – it’s easy to pile on the guilt and be unnecessarily harsh on ourselves. By seeing mistakes as avoidable, it becomes easy to ruminate obsessively about what we could have done differently or how we could have been so foolish. Why didn’t we see it coming? How could we have been so blind?

Thinking like this becomes a form of torture. At best, we’ll conclude that we are a fool undeserving of a PhD. At worst, it’ll drag us down into a dark place from which it’ll be a struggle to recover.

But there is another approach. By seeing mistakes as unavoidable and by adopting a more pragmatic perspective on our own intelligence and agency, we can be more forgiving. Our mistakes no longer reflect our foolishness but rather our humanity.

During your PhD, you operate in conditions of uncertainty, both regarding the outcome of your particular decisions and whether those decisions are even the right ones to be making. You’re steering blind much of the time, and that’s why it becomes inevitable that you’ll make mistakes.

So next time you slip up, be kind to yourself. And give yourself permission to slip up again and again and again.

Your PhD Thesis. On one page.

This won’t last forever.

The overriding feeling for many on their PhD journey is one of discomfort, made worse by the belief that the discomfort will last forever.

If this is you, people around you are able to see what you’re going through for what it is: temporary discomfort in pursuit of your doctorate.

But you can’t, because it’s all new to you. This is your new forever.

Too many people quit their PhDs when they feel like this. Their decision has nothing to do with how well they can tolerate feeling the discomfort, but the mistaken belief that it will never end. Because it seems permanent, it looks unbearable.

It works the other way, too. When things are going well, we can mistakenly think that the good times will last forever. It’s at times like this that we take things for granted, drop the ball, and bring the discomfort back.

However your PhD is going, recognise that your reality is temporary. The good times don’t last, but the bad times don’t either.

Motivation Isn’t Stable

When I start anything, I’m the most enthusiastic person in the world. It’s a thrill, really. I’m bursting with ideas and, crucially, I’m fully motivated.

And then a few weeks go by, and that motivation is nowhere to be seen.

The same was true during my PhD. On day one, I remember how keen I was. Full of beans, ready to tackle the doctorate.

And then fast forward a month or two, and I was starting to question everything.

This was a cycle that repeated itself throughout the PhD. A new year, a new chapter, a new set of data, whatever it was, that sense of newness was motivating. It was a chance to get excited all over again.

And then the newness wore off, the stress kicked back in, and once again I found myself procrastinating.

Can you relate? Do you find your motivation ebbs and flows like this?

The further I went along the PhD journey, the more I started to realize that managing this constant motivated/unmotivated cycle was, in itself, part of the PhD. Learning to ride the waves and deal with the falls was one of the many skills that were necessary to learn to get through to the other side.

And the further I went down the more I realized that in fighting it, in trying to treat motivation as a stable, constant thing, I was creating stress, pressure, and ultimately disappointment and self-critique.

Accepting that motivation isn’t stable, and that it comes in ebbs and flows is empowering. It means you can plan your workload in a more realistic way and start to go easier on yourself when your productivity and enthusiasm naturally decrease.

So next time you find your motivation lacking, remind yourself that it’s normal. We can’t be fully motivated to do everything all the time. Go easy on yourself when you’re in second gear and take full advantage when you’re firing on all cylinders.

You’ll Need to Rewrite Everything

Some of the best advice I got during my PhD was to start writing as early as possible.

But what no one told me was that most of what I wrote would be so off the mark as to render it basically useless. Or that I would end up with notebooks and folders full of crappy drafts. Or that everything would need to be edited at best and rewritten at worst.

I know I’m not alone here. Every student I work with has tons of crappy drafts.

With this in mind, it’s easy to feel like everything you’re putting down on paper is garbage.

But here’s the thing: it’s not garbage. It’s just a draft. And every great piece of writing starts as a draft.

One of the most important things you can do is to write without judgment. Don’t worry about whether it’s perfect or if it’s even making sense. Just get those ideas out of your head and onto paper. You can always go back and edit later. And trust me, you’ll be doing a lot of editing.

It’s also important to remember that writing is a skill, and like any skill, it takes practice to get better. The more you write, the easier it will become, and the better your writing will be. Plus, it is through the act of writing that you work out what it is you actually want to say. Or, put another way, it’s by going down the dead ends that you know which is the right path.

You’re Not Stupid

I spent most of my PhD feeling so confused.

And I spent a good chunk of it feeling just plain stupid. It sounds silly looking back, but I often managed to convince myself I was, in fact, an idiot.

What was worse was that all the while, I thought I was the only one feeling this way. Now, five years on, and having worked with hundreds of students, I realize how common this feeling is.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that everyone else knows exactly what they’re doing, while we struggle to keep up. But the truth is, most PhD students go through periods of confusion and self-doubt. And a big chunk also thinks they’re idiots (spoiler: they’re 100% not).

It’s important to remember that feeling confused or uncertain doesn’t mean you’re not cut out for a PhD. It’s a natural part of the learning process. And there are steps you can take to help yourself navigate these difficult feelings.

Firstly, talk to someone. Whether it’s a friend, family member, or your supervisor, it’s important to have a support system in place. Don’t suffer in silence. By reaching out, you’ll surprise yourself how many other people feel the same.

Finally, take advantage of the resources available to you. Your university likely has a range of support services. Make use of them. You can also check in with our free PhD Knowledge Base. This article is a good place to start. Or, if you want some more hands on support, we offer one one one coaching , mock-vivas, skills workshops and language proofreading . We want to be by your side during your PhD.

Hello, Doctor…

Sounds good, doesn’t it? Be able to call yourself Doctor sooner with our five-star rated How to Write A PhD email-course. Learn everything your supervisor should have taught you about planning and completing a PhD.

Now half price. Join hundreds of other students and become a better thesis writer, or your money back.

Share this:

Submit a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Search The PhD Knowledge Base

Most popular articles from the phd knowlege base.

The PhD Knowledge Base Categories

- Your PhD and Covid

- Mastering your theory and literature review chapters

- How to structure and write every chapter of the PhD

- How to stay motivated and productive

- Techniques to improve your writing and fluency

- Advice on maintaining good mental health

- Resources designed for non-native English speakers

- PhD Writing Template

- Explore our back-catalogue of motivational advice

Living The Dream | Following the Dream

Postcard from Nowhere

Dr. pamela carter , phd florida state university.

Graduation Day loomed at the University of Maryland business school, but unfortunately for new MBA Pamela Carter, employment did not.

With a brilliant track record in her studies, she had performed admirably in a co-op work engagement with the Federal Reserve Board, and was anticipating a permanent job offer at a respectable salary.

She had no Plan B.

The offer did arrive, but it fell far short of her expectations. She declined it. With Memorial Day approaching and no job prospects in sight, she turned to her local newspaper’s classified ads.

In small print, she spotted an opening for an assistant professor to teach office systems technology at Northern Virginia Community College. She had never even thought about teaching college before—but, she reminisces, “It sounded like it could be fun, so I decided I would try for it.”

The college, impressed with her credentials, hired her and put her to work. She proved to be a standout in her first year. But that was when state budget cuts struck the public college. Dr. Carter, the new professor on the block, had no seniority and was first in line to be dismissed.

Then The PhD Project mailer dropped into her mailbox. It was two days before the conference application deadline when she read it.

That night, Dr. Carter stayed up until 3:00 a.m. completing the application. The next morning, she FedEx’d it to meet the deadline.

Meanwhile, her department chair was furiously maneuvering to save the job of his newest professor. Two senior faculty members decided to retire, clearing enough budget room for Dr. Carter to be retained. But having considered the broader possibilities, she declined with thanks and applied to doctoral programs.

“Sometimes,” she says, “you’re on a path that’s meant to be. A postcard comes out of nowhere, you go to a conference, and things start happening.”

Fate played a greater role than she had realized at first. Dr. Carter’s strong first choice was Florida State University. One of the Maryland MBA professors she asked for a recommendation had, it turned out, been a visiting member of the business faculty at Florida State recently. When Florida State’s committee read the recommendation from a former colleague, it gave Dr. Carter’s application greater weight. She was accepted.

Dr. Carter and her husband, facing a significant cut in income, also had the bad luck to be selling their suburban Washington home during a dip in the real estate market. To make ends meet, they realized, it would be necessary to forego vacations and take out loans. “My five dollar jars of olives had to go too,” she jokes. “When you are on a budget, you have to go without some of the little things that make life pleasurable.”

How did she and her husband cope with the necessity of making those sacrifices? “We knew why we were doing it, and we knew it was temporary. We knew what the rewards would be later.”

“In the Ph.D. process,” Dr. Carter adds, “you learn what is really important. That’s what gets you through.”

The dream continues…

In January 2016, Dr. Carter became the Dean of Business & Technology at Community College of Philadelphia.

Dr. Pamela Carter

Community college of philadelphia dean of business & technology, phd florida state university.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In my opinion, the PhD was just a means to an end. As long as it was taking me where I wanted to go afterwards, I didn't care that much about my project that went nowhere. The project went nowhere (I still plan to do something about if after I graduate), but I was still going in the direction I wanted for my career and life.

I'm about to end the first year of my PhD an my project is truly going nowhere... My field is in Bioinformatics and I'm currently enrolled in a european university meaning there is very little coursework, and from year 1 you start doing research. I am a physicist, so it's been hard deciding exactly how to train myself without courses and ...

Be kind to yourself and then see if there is anything salvageable from your project. Look out for questions that remain unanswered, then lick your wounds and start working on something new ...

A. When you need to consider the type of PhD you are doing. An initial factor to consider is the type of PhD you are writing, whether it is producing a number (usually three) of related articles which together form the thesis or the development of a thesis/dissertation (monograph). Projecting forward three possible articles is demanding, and ...

6. If you are really doing research, then the results are not predictable. However, even when the research "fails" to reach some more or less expected end, you learn something. If all your research reaches the expected end, then you aren't doing research, but just confirming something already known, if only approximately.

But joint meetings with a union representative and my supervisors seemed to go nowhere, culminating in accusations that I was "making up" the issues. The union subsequently managed to arrange a meeting with the head of the graduate school, but, nearly six weeks after our meeting, he deemed my case too complex and I was ultimately told to ...

Hello guys, been lurking the sub for some time, first time posting. I'm in my third year of my PhD in Italy, Nanotechnology course, and for the last few weeks i've been felling quite down with the state of my PhD, feeling like i'm getting nowhere and i often can't even understand the basics of my field, expecially in data revision and analysis and sometimes in operating with the lab equipment.

The project is going nowhere for a variety of reasons (the first is that the methodology he wants to use is demonstrably flawed--from a statistical standpoint). Several times over this time period he has dangled the carrot of co-authorship on the paper (at times saying "you will be a co-author", and a few weeks later saying "if you contribute ...

2. First things first: In your country, there must be laws regulating Ph.D. programs and outlining what the requirements for completing such a program are. It can go along the lines of: Demonstrating knowledge and application of research methods. Demonstrating independence in research work.

How to overcome getting scooped, data glitches and funding crises as a PhD. Plus, an AI that learns physics like a baby and how people can sustainably maintain livelihoods that rely on wild species.

If you must know, my thesis had three data chapters (all subsequently papers): chapter 1 - I got the main result in my first year, but then spent the next three years doing more experiments to collect more data, chapter 2 - I got the main result right at the end of my third year, chapter 3 - I got the only result in my so-called writing up year.

And then a few weeks go by, and that motivation is nowhere to be seen. The same was true during my PhD. On day one, I remember how keen I was. Full of beans, ready to tackle the doctorate. And then fast forward a month or two, and I was starting to question everything. This was a cycle that repeated itself throughout the PhD.

I feel as this project is going nowhere and even if I managed to fix some of the logistical issues, the isolation, the lack of expertise of my supervisor and the lack of a research environment really bother me. ... because of course having to do my PhD abroad in another language makes everything harder, but I thought it would have been worth it ...

PhD going nowhere. Back to threads Reply. 4. 4Matt 502 posts 12 years ago. Hi everyone, I'm in the second year as a postgrad, but first year of my proper PhD, as it's a 1+3 PhD, so my Phd is about 4 months old. I've only been able to work on it properly for about two months due to a vital part of the work not being available until the start of ...

Project going nowhere, PI didn't have a plan or seem to care, and her advisory committee consisted of her PI, her PI's best friend, and the PI's best friend's wife. ... Stuff happens, especially when PI's change directions or collaborations change. I know my PhD project changed several times and I was quite late in the process before my project ...

I mapped my life out: I'd study neuroscience at a top university and proceed to do a master's, a Ph.D., and a postdoc, all of which would somehow lead to a prosperous career. But it didn't go quite as planned. During the research portion of my master's degree, I found myself putting in 8 hours of work per day with little enthusiasm.

PhD going nowhere. PhD going nowhere. Back to threads Reply. F. fuzz 10 posts 18 years ago. Hi all, I started a biology PhD over 3 months ago and since then I have started no cell work and have only seen my supervisor say 4 times. My supervisor arranged for postdocs to help me with the cell work but in the last month, I have only seen the ...

I'm about to end the first year of my PhD an my project is truly going nowhere... My field is in Bioinformatics and I'm currently enrolled in a european university meaning there is very little coursework, and from year 1 you start doing research. I am a physicist, so it's been hard deciding exactly how to train myself without courses and ...

We would like to show you a description here but the site won't allow us.

I started to get treatment and reconfigured my study-life balance, and boom - no more feeling of impending doom. Well, now there's the uphill of being a disabled PhD student, but with anxiety everything would be worse. Anyway, my message is that your wellbeing needs to come first. Take care of yourself, I wish you the best. ️

My supervisor (a young-ish professor) mostly works alongside an older professor (his own PhD supervisor back in the day). — First red flag. — My supervisor, on the other hand, spends most of his time providing supervision to the old professor's PhD students — Second red flag. — All the old professor's students work together on everything but I am pretty much isolated — Third red flag.

Dr. Carter, the new professor on the block, had no seniority and was first in line to be dismissed. Then The PhD Project mailer dropped into her mailbox. It was two days before the conference application deadline when she read it. That night, Dr. Carter stayed up until 3:00 a.m. completing the application. The next morning, she FedEx'd it to ...

I am nowhere near finished writing. I am going to fail. What the title says. I hated my project - everything went wrong and I wasn't passionate about it. I was so burnt out by the time I finished my experiments I didn't touch my thesis for a year. ... I'm sorry for what you're going through. The PhD monster rears its head especially when it ...