- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Health Education Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Executive Editor

Michael Eriksen, USA

New Special Issue: Read Now

Health Education Research proudly presents a new Special Issue: Refugee, Immigrant, and Migrant Health. This issue explores the hidden global public health crisis.

Health Education Research deals with all the vital issues involved in health education and promotion worldwide - providing a valuable link between the health education research and practice communities.

Editor's Choice Articles

Executive Editor, Michael Eriksen, has hand-picked a collection of outstanding research articles from the journal, freely available to read.

Explore now

Why should you publish with HER ?

Health Education Research publishes original, peer-reviewed studies that deal with all the vital issues involved in health education and promotion worldwide—providing a valuable link between the health education research and practice communities. Explore the reasons why HER is the perfect home for your research.

Public Health at OUP

Latest articles.

Recommend to your library

Fill out our simple online form to recommend Health Education Research to your library.

Recommend now

Promote Your Article

Have you published an article? What should you do now? Read our top tips on promoting your work to reach a wider audience and ensure your work makes an impact.

Discover a more complete picture of how readers engage with research in Health Education Research through Altmetric data. Now available on article pages.

Email alerts

Register to receive table of contents email alerts as soon as new issues of Health Education Research are published online.

Related Titles

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1465-3648

- Print ISSN 0268-1153

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Open access

- Published: 06 April 2020

The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015

- Viju Raghupathi 1 &

- Wullianallur Raghupathi 2

Archives of Public Health volume 78 , Article number: 20 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

210k Accesses

251 Citations

170 Altmetric

Metrics details

A clear understanding of the macro-level contexts in which education impacts health is integral to improving national health administration and policy. In this research, we use a visual analytic approach to explore the association between education and health over a 20-year period for countries around the world.

Using empirical data from the OECD and the World Bank for 26 OECD countries for the years 1995–2015, we identify patterns/associations between education and health indicators. By incorporating pre- and post-educational attainment indicators, we highlight the dual role of education as both a driver of opportunity as well as of inequality.

Adults with higher educational attainment have better health and lifespans compared to their less-educated peers. We highlight that tertiary education, particularly, is critical in influencing infant mortality, life expectancy, child vaccination, and enrollment rates. In addition, an economy needs to consider potential years of life lost (premature mortality) as a measure of health quality.

Conclusions

We bring to light the health disparities across countries and suggest implications for governments to target educational interventions that can reduce inequalities and improve health. Our country-level findings on NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) rates offer implications for economies to address a broad array of vulnerabilities ranging from unemployment, school life expectancy, and labor market discouragement. The health effects of education are at the grass roots-creating better overall self-awareness on personal health and making healthcare more accessible.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Is education generally associated with good health? There is a growing body of research that has been exploring the influence of education on health. Even in highly developed countries like the United States, it has been observed that adults with lower educational attainment suffer from poor health when compared to other populations [ 36 ]. This pattern is attributed to the large health inequalities brought about by education. A clear understanding of the health benefits of education can therefore serve as the key to reducing health disparities and improving the well-being of future populations. Despite the growing attention, research in the education–health area does not offer definitive answers to some critical questions. Part of the reason is the fact that the two phenomena are interlinked through life spans within and across generations of populations [ 36 ], thereby involving a larger social context within which the association is embedded. To some extent, research has also not considered the variances in the education–health relationship through the course of life or across birth cohorts [ 20 ], or if there is causality in the same. There is therefore a growing need for new directions in education–health research.

The avenues through which education affects health are complex and interwoven. For one, at the very outset, the distribution and content of education changes over time [ 20 ]. Second, the relationship between the mediators and health may change over time, as healthcare becomes more expensive and/or industries become either more, or less hazardous. Third, some research has documented that even relative changes in socioeconomic status (SES) can affect health, and thus changes in the distribution of education implies potential changes in the relationship between education and health. The relative index of inequality summarizes the magnitude of SES as a source of inequalities in health [ 11 , 21 , 27 , 29 ]. Fourth, changes in the distribution of health and mortality imply that the paths to poor health may have changed, thereby affecting the association with education.

Research has proposed that the relationship between education and health is attributable to three general classes of mediators: economic; social, psychological, and interpersonal; and behavioral health [ 31 ]. Economic variables such as income and occupation mediate the relationship between education and health by controlling and determining access to acute and preventive medical care [ 1 , 2 , 19 ]. Social, psychological, and interpersonal resources allow people with different levels of education to access coping resources and strategies [ 10 , 34 ], social support [ 5 , 22 ], and problem-solving and cognitive abilities to handle ill-health consequences such as stress [ 16 ]. Healthy behaviors enable educated individuals to recognize symptoms of ill health in a timely manner and seek appropriate medical help [ 14 , 35 ].

While the positive association between education and health has been established, the explanations for this association are not [ 31 ]. People who are well educated experience better health as reflected in the high levels of self-reported health and low levels of morbidity, mortality, and disability. By extension, low educational attainment is associated with self-reported poor health, shorter life expectancy, and shorter survival when sick. Prior research has suggested that the association between education and health is a complicated one, with a range of potential indicators that include (but are not limited to) interrelationships between demographic and family background indicators [ 8 ] - effects of poor health in childhood, greater resources associated with higher levels of education, appreciation of good health behaviors, and access to social networks. Some evidence suggests that education is strongly linked to health determinants such as preventative care [ 9 ]. Education helps promote and sustain healthy lifestyles and positive choices, nurture relationships, and enhance personal, family, and community well-being. However, there are some adverse effects of education too [ 9 ]. Education may result in increased attention to preventive care, which, though beneficial in the long term, raises healthcare costs in the short term. Some studies have found a positive association between education and some forms of illicit drug and alcohol use. Finally, although education is said to be effective for depression, it has been found to have much less substantial impact in general happiness or well-being [ 9 ].

On a universal scale, it has been accepted that several social factors outside the realm of healthcare influence the health outcomes [ 37 ]. The differences in morbidity, mortality and risk factors in research, conducted within and between countries, are impacted by the characteristics of the physical and social environment, and the structural policies that shape them [ 37 ]. Among the developed countries, the United States reflects huge disparities in educational status over the last few decades [ 15 , 24 ]. Life expectancy, while increasing for all others, has decreased among white Americans without a high school diploma - particularly women [ 25 , 26 , 32 ]. The sources of inequality in educational opportunities for American youth include the neighborhood they live in, the color of their skin, the schools they attend, and the financial resources of their families. In addition, the adverse trends in mortality and morbidity brought on by opioids resulting in suicides and overdoses (referred to as deaths of despair) exacerbated the disparities [ 21 ]. Collectively, these trends have brought about large economic and social inequalities in society such that the people with more education are likely to have more health literacy, live longer, experience better health outcomes, practice health promoting behaviors, and obtain timely health checkups [ 21 , 17 ].

Education enables people to develop a broad range of skills and traits (including cognitive and problem-solving abilities, learned effectiveness, and personal control) that predispose them towards improved health outcomes [ 23 ], ultimately contributing to human capital. Over the years, education has paved the way for a country’s financial security, stable employment, and social success [ 3 ]. Countries that adopt policies for the improvement of education also reap the benefits of healthy behavior such as reducing the population rates of smoking and obesity. Reducing health disparities and improving citizen health can be accomplished only through a thorough understanding of the health benefits conferred by education.

There is an iterative relationship between education and health. While poor education is associated with poor health due to income, resources, healthy behaviors, healthy neighborhood, and other socioeconomic factors, poor health, in turn, is associated with educational setbacks and interference with schooling through difficulties with learning disabilities, absenteeism, or cognitive disorders [ 30 ]. Education is therefore considered an important social determinant of health. The influence of national education on health works through a variety of mechanisms. Generally, education shows a relationship with self-rated health, and thus those with the highest education may have the best health [ 30 ]. Also, health-risk behaviors seem to be reduced by higher expenditure into the publicly funded education system [ 18 ], and those with good education are likely to have better knowledge of diseases [ 33 ]. In general, the education–health gradients for individuals have been growing over time [ 38 ].

To inform future education and health policies effectively, one needs to observe and analyze the opportunities that education generates during the early life span of individuals. This necessitates the adoption of some fundamental premises in research. Research must go beyond pure educational attainment and consider the associated effects preceding and succeeding such attainment. Research should consider the variations brought about by the education–health association across place and time, including the drivers that influence such variations [ 36 ].

In the current research, we analyze the association between education and health indicators for various countries using empirical data from reliable sources such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and World Bank. While many studies explore the relationship between education and health at a conceptual level, we deploy an empirical approach in investigating the patterns and relationships between the two sets of indicators. In addition, for the educational indicators, we not only incorporate the level of educational attainment, but also look at the potential socioeconomic benefits, such as enrollment rates (in each sector of educational level) and school life expectancy (at each educational level). We investigate the influences of educational indicators on national health indicators of infant mortality, child vaccinations, life expectancy at birth, premature mortality arising from lack of educational attainment, employment and training, and the level of national health expenditure. Our research question is:

What are some key influencers/drivers in the education-health relationship at a country level?

The current study is important because policy makers have an increasing concern on national health issues and on policies that support it. The effect of education is at the root level—creating better overall self-awareness on personal health and making healthcare more accessible. The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the background for the research. Section 3 discusses the research method; Section 4 offers the analysis and results; Section 5 provides a synthesis of the results and offers an integrated discussion; Section 6 contains the scope and limitations of the research; Section 7 offers conclusions with implications and directions for future research.

Research has traditionally drawn from three broad theoretical perspectives in conceptualizing the relationship between education and health. The majority of research over the past two decades has been grounded in the Fundamental Cause Theory (FCT) [ 28 ], which posits that factors such as education are fundamental social causes of health inequalities because they determine access to resources (such as income, safe neighborhoods, or healthier lifestyles) that can assist in protecting or enhancing health [ 36 ]. Some of the key social resources that contribute to socioeconomic status include education (knowledge), money, power, prestige, and social connections. As some of these undergo change, they will be associated with differentials in the health status of the population [ 12 ].

Education has also been conceptualized using the Human Capital Theory (HCT) that views it as a return on investment in the form of increased productivity [ 4 ]. Education improves knowledge, skills, reasoning, effectiveness, and a broad range of other abilities that can be applied to improving health. The third approach - the signaling or credentialing perspective [ 6 ] - is adopted to address the large discontinuities in health at 12 and 16 years of schooling, which are typically associated with the receipt of a high school diploma and a college degree, respectively. This perspective considers the earned credentials of a person as a potential source that warrants social and economic returns. All these theoretical perspectives postulate a strong association between education and health and identify mechanisms through which education influences health. While the HCT proposes the mechanisms as embodied skills and abilities, FCT emphasizes the dynamism and flexibility of mechanisms, and the credentialing perspective proposes educational attainment through social responses. It needs to be stated, however, that all these approaches focus on education solely in terms of attainment, without emphasizing other institutional factors such as quality or type of education that may independently influence health. Additionally, while these approaches highlight the individual factors (individual attainment, attainment effects, and mechanisms), they do not give much emphasis to the social context in which education and health processes are embedded.

In the current research while we acknowledge the tenets of these theoretical perspectives, we incorporate the social mechanisms in education such as level of education, skills and abilities brought about by enrollment, school life expectancy, and the potential loss brought about by premature mortality. In this manner, we highlight the relevance of the social context in which the education and health domains are situated. We also study the dynamism of the mechanisms over countries and over time and incorporate the influences that precede and succeed educational attainment.

We analyze country level education and health data from the OECD and World Bank for a period of 21 years (1995–2015). Our variables include the education indicators of adult education level; enrollment rates at various educational levels; NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training) rates; school life expectancy; and the health indicators of infant mortality, child vaccination rates, deaths from cancer, life expectancy at birth, potential years of life lost and smoking rates (Table 1 ). The data was processed using the tools of Tableau for visualization, and SAS for correlation and descriptive statistics. Approaches for analysis include ranking, association, and data visualization of the health and education data.

Analyses and results

In this section we identify and analyze patterns and associations between education and health indicators and discuss the results. Since countries vary in population sizes and other criteria, we use the estimated averages in all our analyses.

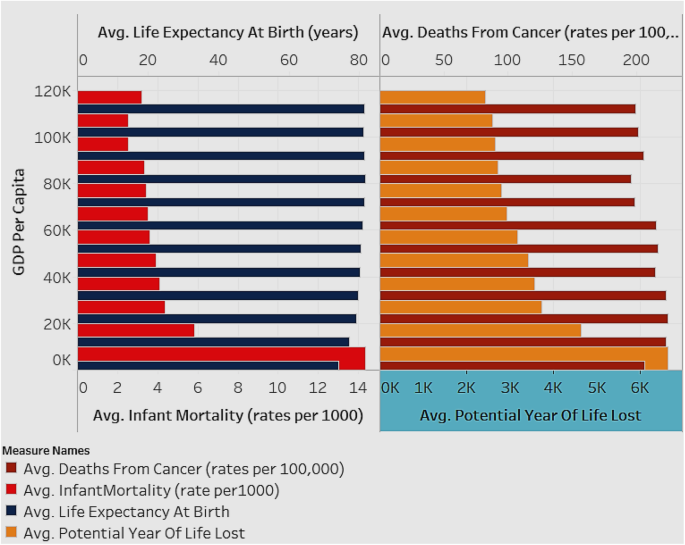

Comparison of health outcomes for countries by GDP per capita

We first analyzed to see if our data reflected the expectation that countries with higher GDP per capita have better health status (Fig. 1 ). We compared the average life expectancy at birth, average infant mortality, average deaths from cancer and average potential year of life lost, for different levels of GDP per capita (Fig. 1 ).

Associations between Average Life Expectancy (years) and Average Infant Mortality rate (per 1000), and between Deaths from Cancer (rates per 100,000) and Average Potential Years of Life Lost (years), by GDP per capita (for all countries for years 1995–2015)

Figure 1 depicts two charts with the estimated averages of variables for all countries in the sample. The X-axis of the first chart depicts average infant mortality rate (per 1000), while that of the second chart depicts average potential years of life lost (years). The Y-axis for both charts depicts the GDP per capita shown in intervals of 10 K ranging from 0 K–110 K (US Dollars). The analysis is shown as an average for all the countries in the sample and for all the years (1995–2015). As seen in Fig. 1 , countries with lower GDP per capita have higher infant mortality rate and increased potential year of life lost (which represents the average years a person would have lived if he or she had not died prematurely - a measure of premature mortality). Life expectancy and deaths from cancer are not affected by GDP level. When studying infant mortality and potential year lost, in order to avoid the influence of a control variable, it was necessary to group the samples by their GDP per capita level.

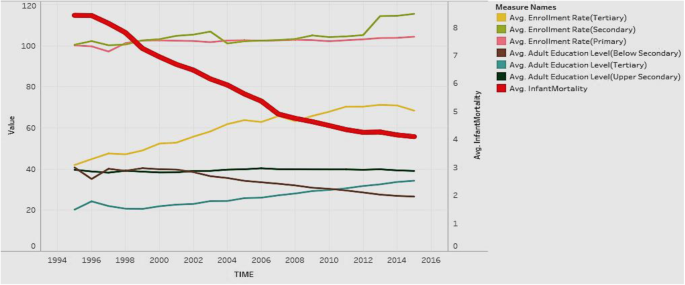

Association of Infant Mortality Rates with enrollment rates and education levels

We explored the association of infant mortality rates with the enrollment rates and adult educational levels for all countries (Fig. 2 ). The expectation is that with higher education and employment the infant mortality rate decreases.

Association of Adult Education Levels (ratio) and Enrollment Rates (ratio) with Infant Mortality Rate (per 1000)

Figure 2 depicts the analysis for all countries in the sample. The figure shows the years from 1995 to 2015 on the X axis. It shows two Y-axes with one axis denoting average infant mortality rate (per 1000 live births), and the other showing the rates from 0 to 120 to depict enrollment rates (primary/secondary/tertiary) and education levels (below secondary/upper secondary/tertiary). Regarding the Y axis showing rates over 100, it is worth noting that the enrollment rates denote a ratio of the total enrollment (regardless of age) at a level of education to the official population of the age group in that education level. Therefore, it is possible for the number of children enrolled at a level to exceed the official population of students in the age group for that level (due to repetition or late entry). This can lead to ratios over 100%. The figure shows that in general, all education indicators tend to rise over time, except for adult education level below secondary, which decreases over time. Infant mortality shows a steep decreasing trend over time, which is favorable. In general, countries have increasing health status and education over time, along with decreasing infant mortality rates. This suggests a negative association of education and enrollment rates with mortality rates.

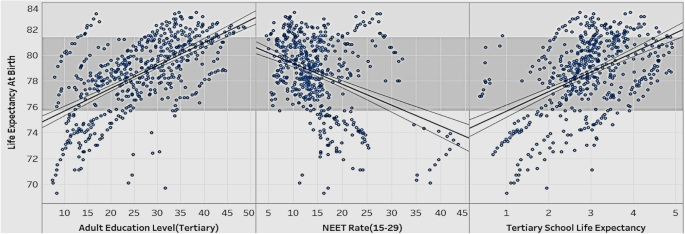

Association of Education Outcomes with life expectancy at birth

We explored if the education outcomes of adult education level (tertiary), school life expectancy (tertiary), and NEET (not in employment, education, or training) rates, affected life expectancy at birth (Fig. 3 ). Our expectation is that adult education and school life expectancy, particularly tertiary, have a positive influence, while NEET has an adverse influence, on life expectancy at birth.

Association of Adult Education Level (Tertiary), NEET rate, School Life Expectancy (Tertiary), with Life Expectancy at Birth

Figure 3 show the relationships between various education indicators (adult education level-tertiary, NEET rate, school life expectancy-tertiary) and life expectancy at birth for all countries in the sample. The figure suggests that life expectancy at birth rises as adult education level (tertiary) and tertiary school life expectancy go up. Life expectancy at birth drops as the NEET rate goes up. In order to extend people’s life expectancy, governments should try to improve tertiary education, and control the number of youths dropping out of school and ending up unemployed (the NEET rate).

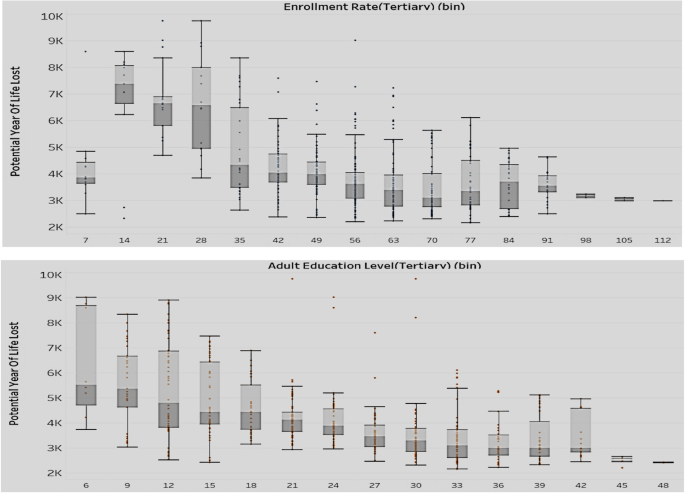

Association of Tertiary Enrollment and Education with potential years of life lost

We wanted to explore if the potential years of life lost rates are affected by tertiary enrollment rates and tertiary adult education levels (Fig. 4 ).

Association of Enrollment rate-tertiary (top) and Adult Education Level-Tertiary (bottom) with Potential Years of Life Lost (Y axis)

The two sets of box plots in Fig. 4 compare the enrollment rates with potential years of life lost (above set) and the education level with potential years of life lost (below set). The analysis is for all countries in the sample. As mentioned earlier, the enrollment rates are expressed as ratios and can exceed 100% if the number of children enrolled at a level (regardless of age) exceed the official population of students in the age group for that level. Potential years of life lost represents the average years a person would have lived, had he/she not died prematurely. The results show that with the rise of tertiary adult education level and tertiary enrollment rate, there is a decrease in both value and variation of the potential years of life lost. We can conclude that lower levels in tertiary education adversely affect a country’s health situation in terms of premature mortality.

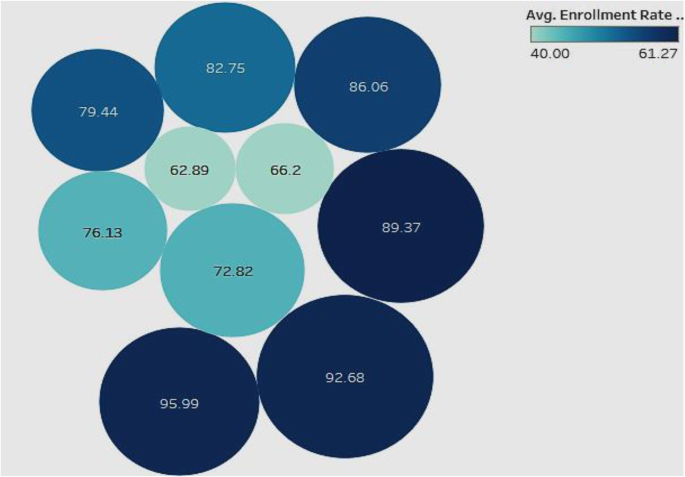

Association of Tertiary Enrollment and Education with child vaccination rates

We compared the performance of tertiary education level and enrollment rates with the child vaccination rates (Fig. 5 ) to assess if there was a positive impact of education on preventive healthcare.

Association of Adult Education Level-Tertiary and Enrollment Rate-Tertiary with Child Vaccination Rates

In this analysis (Fig. 5 ), we looked for associations of child vaccination rates with tertiary enrollment and tertiary education. The analysis is for all countries in the sample. The color of the bubble represents the tertiary enrollment rate such that the darker the color, the higher the enrollment rate, and the size of the bubble represents the level of tertiary education. The labels inside the bubbles denote the child vaccination rates. The figure shows a general positive association of high child vaccination rate with tertiary enrollment and tertiary education levels. This indicates that countries that have high child vaccination rates tend to be better at tertiary enrollment and have more adults educated in tertiary institutions. Therefore, countries that focus more on tertiary education and enrollment may confer more health awareness in the population, which can be reflected in improved child vaccination rates.

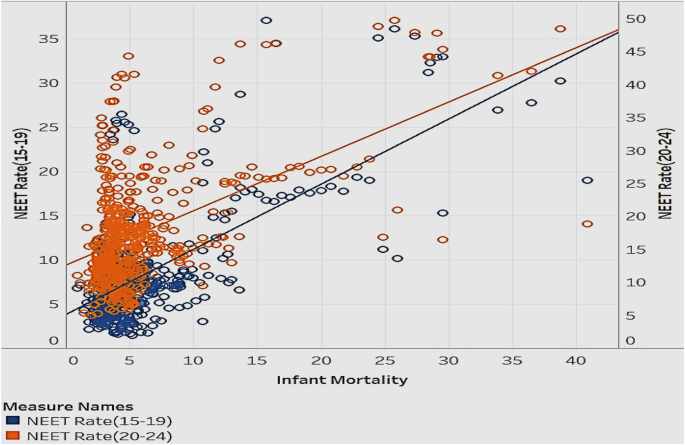

Association of NEET rates (15–19; 20–24) with infant mortality rates and deaths from Cancer

In the realm of child health, we also looked at the infant mortality rates. We explored if infant mortality rates are associated with the NEET rates in different age groups (Fig. 6 ).

Association of Infant Mortality rates with NEET Rates (15–19) and NEET Rates (20–24)

Figure 6 is a scatterplot that explores the correlation between infant mortality and NEET rates in the age groups 15–19 and 20–24. The data is for all countries in the sample. Most data points are clustered in the lower infant mortality and lower NEET rate range. Infant mortality and NEET rates move in the same direction—as infant mortality increases/decrease, the NEET rate goes up/down. The NEET rate for the age group 20–24 has a slightly higher infant mortality rate than the NEET rate for the age group 15–19. This implies that when people in the age group 20–24 are uneducated or unemployed, the implications on infant mortality are higher than in other age groups. This is a reasonable association, since there is the potential to have more people with children in this age group than in the teenage group. To reduce the risk of infant mortality, governments should decrease NEET rates through promotional programs that disseminate the benefits of being educated, employed, and trained [ 7 ]. Additionally, they can offer financial aid to public schools and companies to offer more resources to raise general health awareness in people.

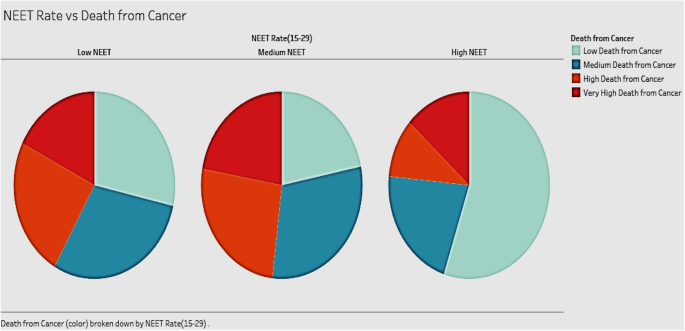

We looked to see if the distribution of population without employment, education, or training (NEET) in various categories of high, medium, and low impacted the rate of deaths from cancer (Fig. 7 ). Our expectation is that high rates of NEET will positively influence deaths from cancer.

Association of Deaths from Cancer and different NEET Rates

The three pie charts in Fig. 7 show the distribution of deaths from cancer in groups of countries with different NEET rates (high, medium, and low). The analysis includes all countries in the sample. The expectation was that high rates of NEET would be associated with high rates of cancer deaths. Our results, however, show that countries with medium NEET rates tend to have the highest deaths from cancer. Countries with high NEET rates have the lowest deaths from cancer among the three groups. Contrary to expectations, countries with low NEET rates do not show the lowest death rates from cancer. A possible explanation for this can be attributed to the fact that in this group, the people in the labor force may be suffering from work-related hazards including stress, that endanger their health.

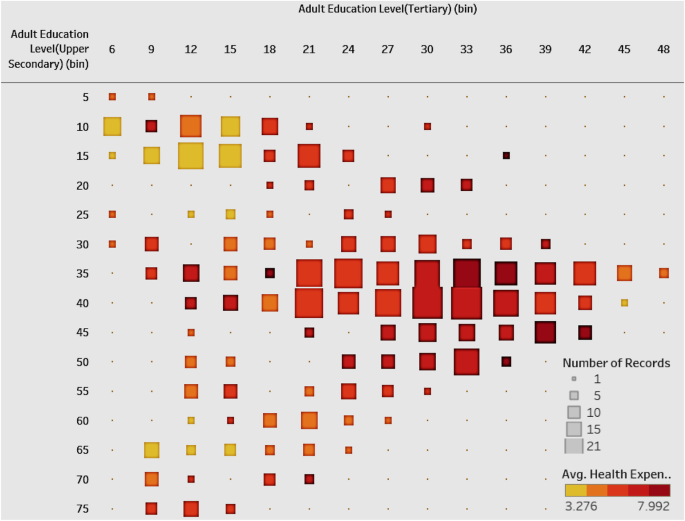

Association between adult education levels and health expenditure

It is interesting to note the relationship between health expenditure and adult education levels (Fig. 8 ). We expect them to be positively associated.

Association of Health Expenditure and Adult Education Level-Tertiary & Upper Secondary

Figure 8 shows a heat map with the number of countries in different combinations of groups between tertiary and upper-secondary adult education level. We emphasize the higher levels of adult education. The color of the square shows the average of health expenditure. The plot shows that most of the countries are divided into two clusters. One cluster has a high tertiary education level as well as a high upper-secondary education level and it has high average health expenditure. The other cluster has relatively low tertiary and upper secondary education level with low average health expenditure. Overall, the figure shows a positive correlation between adult education level and compulsory health expenditure. Governments of countries with low levels of education should allocate more health expenditure, which will have an influence on the educational levels. Alternatively, to improve public health, governments can frame educational policies to improve the overall national education level, which then produces more health awareness, contributing to national healthcare.

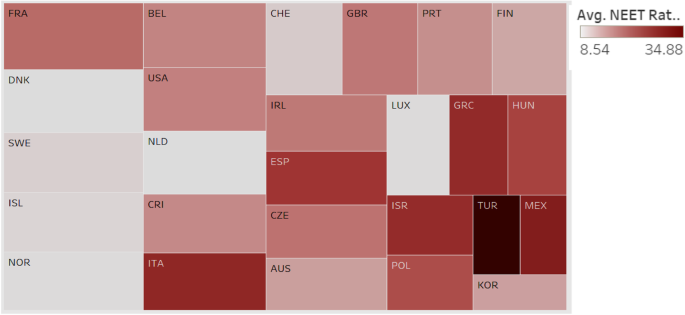

Association of Compulsory Health Expenditure with NEET rates by country and region

Having explored the relationship between health expenditure and adult education, we then explored the relationship between health expenditure and NEET rates of different countries (Fig. 9 ). We expect compulsory health expenditure to be negatively associated with NEET rates.

Association between Compulsory Health Expenditure and NEET Rate by Country and Region

In Fig. 9 , each box represents a country or region; the size of the box indicates the extent of compulsory health expenditure such that a larger box implies that the country has greater compulsory health expenditure. The intensity of the color of the box represents the NEET rate such that the darker color implies a higher NEET rate. Turkey has the highest NEET rate with low health expenditure. Most European countries such as France, Belgium, Sweden, and Norway have low NEET rates and high health expenditure. The chart shows a general association between low compulsory health expenditure and high NEET rates. The relationship, however, is not consistent, as there are countries with high NEET and high health expenditures. Our suggestion is for most countries to improve the social education for the youth through free training programs and other means to effectively improve the public health while they attempt to raise the compulsory expenditure.

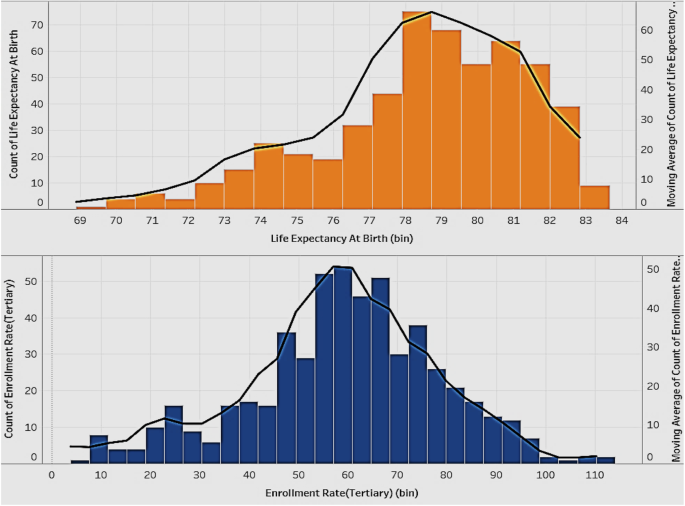

Distribution of life expectancy at birth and tertiary enrollment rate

The distribution of enrollment rate (tertiary) and life expectancy of all the countries in the sample can give an idea of the current status of both education and health (Fig. 10 ). We expect these to be positively associated.

Distribution of Life Expectancy at Birth (years) and Tertiary Enrollment Rate

Figure 10 shows two histograms with the lines representing the distribution of life expectancy at birth and the tertiary enrollment rate of all the countries. The distribution of life expectancy at birth is skewed right, which means most of the countries have quite a high life expectancy and there are few countries with a very low life expectancy. The tertiary enrollment rate has a good distribution, which is closer to a normal distribution. Governments of countries with an extremely low life expectancy should try to identify the cause of this problem and take actions in time to improve the overall national health.

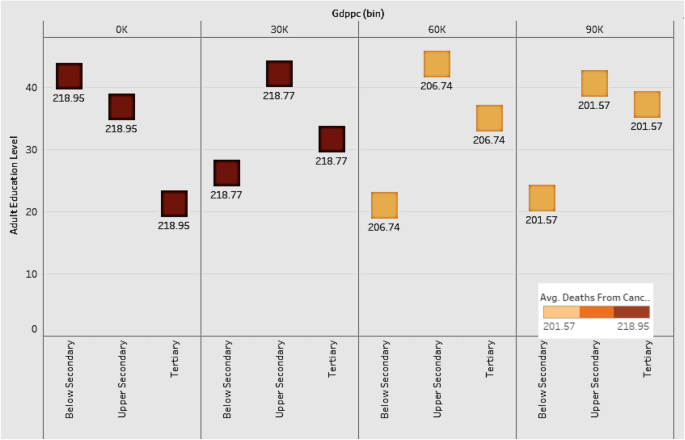

Comparison of adult education levels and deaths from Cancer at various levels of GDP per capita

We wanted to see if various levels of GDP per capita influence the levels of adult education and deaths from cancer in countries (Fig. 11 ).

Comparison of Adult Education Levels and Deaths from Cancer at various levels of GDP per capita

Figure 11 shows the distribution of various adult education levels for countries by groups of GDP per capita. The plot shows that as GDP grows, the level of below-secondary adult education becomes lower, and the level of tertiary education gets higher. The upper-secondary education level is constant among all the groups. The implication is that tertiary education is the most important factor among all the education levels for a country to improve its economic power and health level. Countries should therefore focus on tertiary education as a driver of economic development. As for deaths from cancer, countries with lower GDP have higher death rates, indicating the negative association between economic development and deaths from cancer.

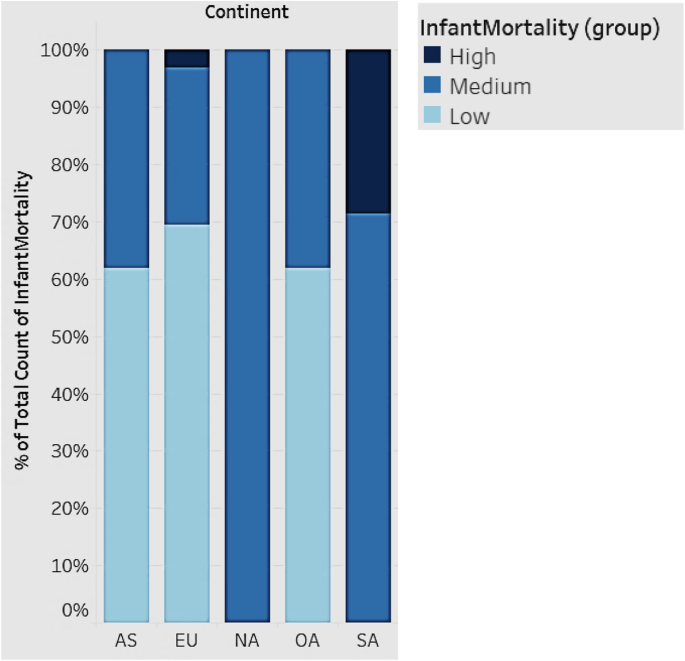

Distribution of infant mortality rates by continent

Infant mortality is an important indicator of a country’s health status. Figure 12 shows the distribution of infant mortality for the continents of Asia, Europe, Oceania, North and South America. We grouped the countries in each continent into high, medium, and low, based on infant mortality rates.

Distribution of Infant Mortality rates by Continent

In Fig. 12 , each bar represents a continent. All countries fall into three groups (high, medium, and low) based on infant mortality rates. South America has the highest infant mortality, followed by Asia, Europe, and Oceania. North America falls in the medium range of infant mortality. South American countries, in general, should strive to improve infant mortality. While Europe, in general, has the lowest infant mortality rates, there are some countries that have high rates as depicted.

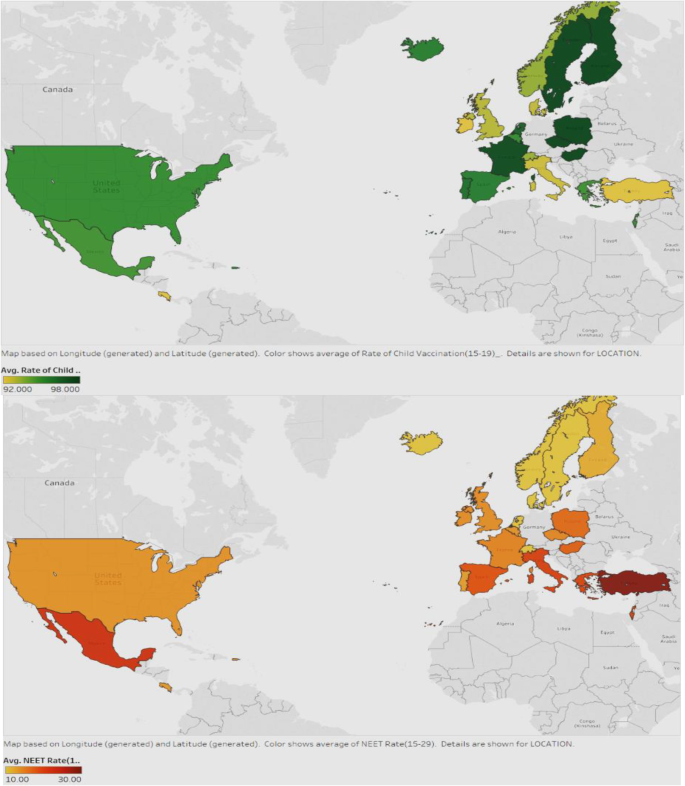

Association between child vaccination rates and NEET rates

We looked at the association between child vaccination rates and NEET rates in various countries (Fig. 13 ). We expect countries that have high NEET rates to have low child vaccination rates.

Association between Child Vaccination Rates and NEET rates

Figure 13 displays the child vaccination rates in the first map and the NEET rates in the second map, for all countries. The darker green color shows countries with higher rates of vaccination and the darker red represents those with higher NEET rates. It can be seen that in general, the countries with lower NEET also have better vaccination rates. Examples are USA, UK, Iceland, France, and North European countries. Countries should therefore strive to reduce NEET rates by enrolling a good proportion of the youth into initiatives or programs that will help them be more productive in the future, and be able to afford preventive healthcare for the families, particularly, the children.

Average smoking rate in different continents over time

We compared the trend of average smoking rate for the years 1995–201 for the continents in the sample (Fig. 14 ).

Trend of average smoking rate in different continents from 1995 to 2015

Figure 14 depicts the line charts of average smoking rates for the continents of Asia, Europe, Oceania, North and South America. All the lines show an overall downward trend, which indicates that the average smoking rate decreases with time. The trend illustrates that people have become more health conscious and realize the harmful effects of smoking over time. However, the smoking rate in Europe (EU) is consistently higher than that in other continents, while the smoking rate in North America (NA) is consistently lower over the years. Governments in Europe should pay attention to the usage of tobacco and increase health consciousness among the public.

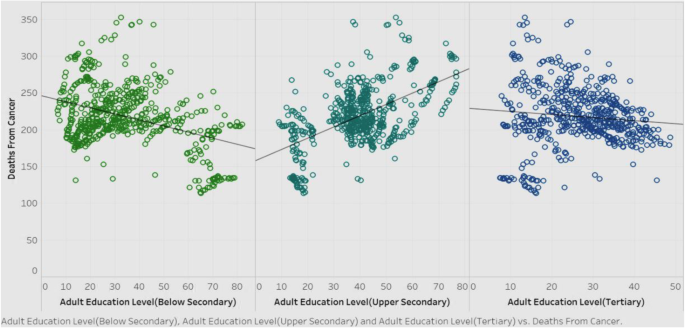

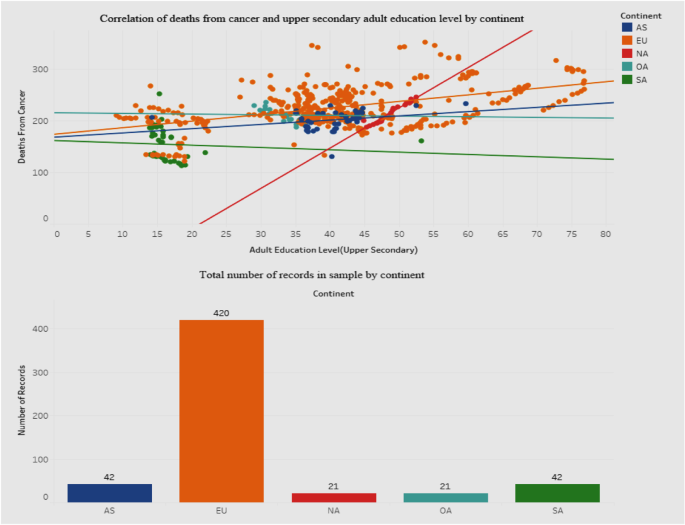

Association between adult education levels and deaths from Cancer

We explored if adult education levels (below-secondary, upper-secondary, and tertiary) are associated with deaths from cancer (Fig. 15 ) such that higher levels of education will mitigate the rates of deaths from cancer, due to increased awareness and proactive health behavior.

Association of deaths from cancer with adult education levels

Figure 15 shows the correlations of deaths from cancer among the three adult education levels, for all countries in the sample. It is obvious that below-secondary and tertiary adult education levels have a negative correlation with deaths from cancer, while the upper-secondary adult education level shows a positive correlation. Barring upper-secondary results, we can surmise that in general, as education level goes higher, the deaths from cancer will decrease. The rationale for this could be that education fosters more health awareness and encourages people to adopt healthy behavioral practices. Governments should therefore pay attention to frame policies that promote education. However, the counterintuitive result of the positive correlation between upper-secondary levels of adult education with the deaths from cancer warrants more investigation.

We drilled down further into the correlation between the upper-secondary education level and deaths from cancer. Figure 16 shows this correlation, along with a breakdown of the total number of records for each continent, to see if there is an explanation for the unique result.

Association between deaths from cancer and adult education level-upper secondary

Figure 16 shows a dashboard containing two graphs - a scatterplot of the correlation between deaths from cancer and education level, and a bar graph showing the breakdown of the total sample by continent. We included a breakdown by continent in order to explore variances that may clarify or explain the positive association for deaths from cancer with the upper-secondary education level. The scatterplot shows that for the European Union (EU) the points are much more scattered than for the other continents. Also, the correlation between deaths and education level for the EU is positive. The bottom bar graph depicts how the sample contains a disproportionately high number of records for the EU than for other continents. It is possible that this may have influenced the results of the correlation. The governments in the EU should investigate the reasons behind this phenomenon. Also, we defer to future research to explore this in greater detail by incorporating other socioeconomic parameters that may have to be factored into the relationship.

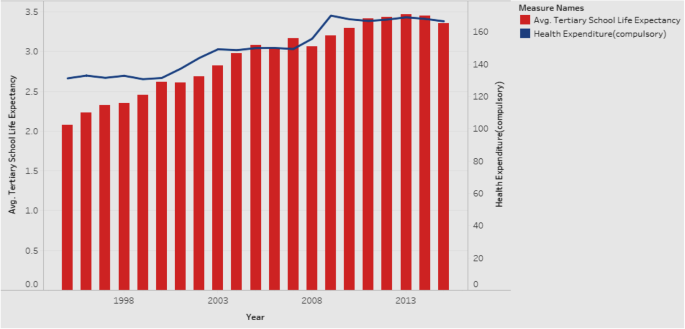

Association between average tertiary school life expectancy and health expenditure

We moved our focus to the trends of tertiary school life expectancy and health expenditure from 1995 to 2015 (Fig. 17 ) to check for positive associations.

Association between Average Tertiary School Life Expectancy and Health Expenditure

Figure 17 is a combination chart explaining the trends of tertiary school life expectancy and health expenditure, for all countries in the sample. The rationale is that if there is a positive association between the two, it would be worthwhile for the government to allocate more resources towards health expenditure. Both tertiary school life expectancy and health expenditure show an increase over the years from 1995 to 2015. Our additional analysis shows that they continue to increase even after 2015. Hence, governments are encouraged to increase the health expenditure in order to see gains in tertiary school life expectancy, which will have positive implications for national health. Given that the measured effects of education are large, investments in education might prove to be a cost-effective means of achieving better health.

Our results reveal how interlinked education and health can be. We show how a country can improve its health scenario by focusing on appropriate indicators of education. Countries with higher education levels are more likely to have better national health conditions. Among the adult education levels, tertiary education is the most critical indicator influencing healthcare in terms of infant mortality, life expectancy, child vaccination rates, and enrollment rates. Our results emphasize the role that education plays in the potential years of life lost, which is a measure that represents the average years a person would have lived had he/she not died prematurely. In addition to mortality rate, an economy needs to consider this indicator as a measure of health quality.

Other educational indicators that are major drivers of health include school life expectancy, particularly at the tertiary level. In order to improve the school life expectancy of the population, governments should control the number of youths ending up unemployed, dropping out of school, and without skills or training (the NEET rate). Education allows people to gain skills/abilities and knowledge on general health, enhancing their awareness of healthy behaviors and preventive care. By targeting promotions and campaigns that emphasize the importance of skills and employment, governments can reduce the NEET rates. And, by reducing the NEET rates, governments have the potential to address a broad array of vulnerabilities among youth, ranging from unemployment, early school dropouts, and labor market discouragement, which are all social issues that warrant attention in a growing economy.

We also bring to light the health disparities across countries and suggest implications for governments to target educational interventions that can reduce inequalities and improve health, at a macro level. The health effects of education are at the grass roots level - creating better overall self-awareness on personal health and making healthcare more accessible.

Scope and limitations

Our research suffers from a few limitations. For one, the number of countries is limited, and being that the data are primarily drawn from OECD, they pertain to the continent of Europe. We also considered a limited set of variables. A more extensive study can encompass a larger range of variables drawn from heterogeneous sources. With the objective of acquiring a macro perspective on the education–health association, we incorporated some dependent variables that may not traditionally be viewed as pure health parameters. For example, the variable potential years of life lost is affected by premature deaths that may be caused by non-health related factors too. Also there may be some intervening variables in the education–health relationship that need to be considered. Lastly, while our study explores associations and relationships between variables, it does not investigate causality.

Conclusions and future research

Both education and health are at the center of individual and population health and well-being. Conceptualizations of both phenomena should go beyond the individual focus to incorporate and consider the social context and structure within which the education–health relationship is embedded. Such an approach calls for a combination of interdisciplinary research, novel conceptual models, and rich data sources. As health differences are widening across the world, there is need for new directions in research and policy on health returns on education and vice versa. In developing interventions and policies, governments would do well to keep in mind the dual role played by education—as a driver of opportunity as well as a reproducer of inequality [ 36 ]. Reducing these macro-level inequalities requires interventions directed at a macro level. Researchers and policy makers have mutual responsibilities in this endeavor, with researchers investigating and communicating the insights and recommendations to policy makers, and policy makers conveying the challenges and needs of health and educational practices to researchers. Researchers can leverage national differences in the political system to study the impact of various welfare systems on the education–health association. In terms of investment in education, we make a call for governments to focus on education in the early stages of life course so as to prevent the reproduction of social inequalities and change upcoming educational trajectories; we also urge governments to make efforts to mitigate the rising dropout rate in postsecondary enrollment that often leads to detrimental health (e.g., due to stress or rising student debt). There is a need to look into the circumstances that can modify the postsecondary experience of youth so as to improve their health.

Our study offers several prospects for future research. Future research can incorporate geographic and environmental variables—such as the quality of air level or latitude—for additional analysis. Also, we can incorporate data from other sources to include more countries and more variables, especially non-European ones, so as to increase the breadth of analysis. In terms of methodology, future studies can deploy meta-regression analysis to compare the relationships between health and some macro-level socioeconomic indicators [ 13 ]. Future research should also expand beyond the individual to the social context in which education and health are situated. Such an approach will help generate findings that will inform effective educational and health policies and interventions to reduce disparities.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Fundamental Cause Theory

Human Capital Theory

Not in Employment, Education, or Training

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Socio-economic status

Andersen RM, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1973;51(1):95–124.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Social Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10.

Baker DP. The Schooled Society: The Educational Transformation of Global Culture. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press: 2014; 360.

Becker GS. Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press; 1964.

Google Scholar

Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Oxford Acad J. 1979;109(2):186–204.

CAS Google Scholar

Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Vasunilashorn S. Biodemography: new approaches to understanding trends and differences in population health and mortality. Demography. 2010;47:S41–64.

Article Google Scholar

Spence M. Job market signalling. The Quarterly J Econ. 1973;87:355–79.

Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Education and Health: Evaluating Theories and Evidence: NBER Working Papers; 2006. p. 12352.

Feinstein L. What are the effects of education on health? OECD Proceedings of the Copenhagen Symposium; 2006 . .

Folkman S, Lazarus RS. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J Health Soc Behav. 1980;21(3):219–39.

Freedman VA, Martin LG. The role of education in explaining and forecasting trends in functional limitations among older Americans. Demography. 1999;36(4):461–73.

Freese J, Lutfey K. Fundamental causality: challenges of an animating concept for medical sociology. In: Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, McLeod JD, Rogers A, editors. Handbook of the Sociology of Health, Illness, and Healing: a blueprint for the 21st century. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 67–81.

Chapter Google Scholar

Fouweather T, Gillies C, Wohland P, Van Oyen H, Nusselde W, Robine J, Cambois E, Jagger C. Comparison of socio-economic indicators explaining inequalities in healthy life years at age 50 in Europe: 2005 and 2010. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25:978–83.

George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver Weil-being: a multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. Gerontologist. 1986;26(3):253–9.

Goldman D, Smith JP. The increasing value of education to health. Soc Sc Med. 2011;72(10):1728–37.

Harper AC, Lambert LJ. The health of populations: an introduction. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1994.

Health 2020: Education and health through the life-course. WHO Europe Sector Brief on Education Health; 2015. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/324619/Health-2020-Education-and-health-through-the-life-course-en.pdf?ua=1 .

Kino S, Bernabé E, Sabbah W. The role of healthcare and education systems in co-occurrence of health risk behaviours in 27 European countries. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28(1):186–92.

Landerman LR, Burns BJ, Swartz MS, Wagner HR, George LK. The relationship between insurance coverage and psychiatric disorder in predicting use of mental health services. Am J Psychol. 1994;151(12):1785.

Lynch SM. Cohort and life-course patterns in the relationship between education and health: a hierarchical approach. Demography. 2003;40(2):309–31.

Mackenbach J, Kunst A. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(6):757–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00073-1 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Manton KG, Corder L, Stallard E. Chronic disability trends in elderly United States populations: 1982-1994. Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94(6):2593–8.

Mirowski J, Ross CE. Education, learned effectiveness and health. London Rev Edu. 2005;3(3):205–20.

Montez JK, Berkman LF. Trends in the educational gradient of mortality among US adults aged 45 to 84 years: bringing regional context into the explanation. Am J Pub Health. 2014;104(1):e82–90.

Montez JK, Zajacova A. Trends in mortality risk by education level and cause of death among US white women from 1986 to 2006. Am J Pub Health. 2013;103:473–9.

Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, Binstock RH, Boersch-Supan A, Cacioppo JT, Carnes BA, Carstensen LL, Fried LP, Goldman DP, Jackson J, Kohli M, Rother J, Zheng Y, Rowe J. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Aff. 2012;31(8):1803–13.

Pamuk ER. Social-class inequality in infant mortality in England and Wales from 1921 to 1980. Eur J Popul 1988; 4 , 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01797104.

Phelan JC , Link BG , Tehranifar P . Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications . J Health Soc Behav 2010 ; 51 : S28 S40 . doi : 10.1177/0022146510383498.

Renard F, Devleesschauwer B, Speybroeck N, Deboosere P. Monitoring health inequalities when the socio-economic composition changes: are the slope and relative indices of inequality appropriate? Results of a simulation study. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 662. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6980-1.

Ro A, Geronimus A, Bound J, Griffith D, Gee G. Educational gradients in five Asian immigrant populations: do country of origin, duration and generational status moderate the education-health relationship? Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:338–43.

Ross CE, Wu CL. The links between education and health. Am Soc Rev. 1995;60(5):719–45.

Shiels MS, Chernyavskiy P, Anderson WF, Best AF, Haozous EA. Diverging trends in premature mortality in the U.S. by sex, race, and ethnicity in the 21st century. Lancet. 2017;389:1043–54.

Tsou MT. Association of Education, health behaviors, concerns, and knowledge with metabolic syndrome among urban elderly in one medical Center in Taiwan. Int J Gerontology. 2017;11(3:138–43.

Wheaton B. Stress, personal coping resources, and psychiatric symptoms: an investigation of interactive models. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(3):208–29.

Williams DR, Collins C. US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: patterns and explanations. Ann Rev Soc. 1995;21:349–86.

Zajacova A, Lawrence EM. The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Ann Rev Pub Health. 2018;39:273–89.

Zimmerman EB, Woolf SH. Understanding the relationship between education and health. Discussion Paper, Inst Med. Washington DC; 2014. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BPH-UnderstandingTheRelationship1.pdf .

Zhong H. An over time analysis on the mechanisms behind the education–health gradients in China. China Econ Rev. 2015;34(C):135–49.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Koppelman School of Business, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Ave, Brooklyn, NY, 11210, USA

Viju Raghupathi

Gabelli School of Business, Fordham University, 140 W. 62nd Street, New York, NY, 10023, USA

Wullianallur Raghupathi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to all parts of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Viju Raghupathi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Raghupathi, V., Raghupathi, W. The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Arch Public Health 78 , 20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5

Download citation

Received : 16 October 2019

Accepted : 26 February 2020

Published : 06 April 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Education level

- Enrollment rate

- Life expectancy

- Potential years of life lost

- Infant mortality

- Deaths from cancer

Archives of Public Health

ISSN: 2049-3258

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 04 August 2022

Using theory in health professions education research: a guide for early career researchers

- Koshila Kumar 1 ,

- Chris Roberts 2 ,

- Gabrielle M. Finn 3 &

- Yu-Che Chang 4

BMC Medical Education volume 22 , Article number: 601 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3804 Accesses

5 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

An Editorial to this article was published on 16 November 2020

Theory provides complex and comprehensive explanations of a wide range of phenomena (i.e., things that we research), and using theory can enhance quality in health professions education (HPE) research [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. However, those who are new to HPE research and early career researchers (ECRs) can find it challenging to use theory. In this paper, we outline key considerations (see Table 1 ) for using theory in HPE research, both in relation to theory as a subject or content area and the process of using it, including critically questioning which theories are priviledged in the HPE literature [ 5 , 6 ]. By providing this guidance, we hope to support new and early-career HPE researchers around the globe to enhance their capacity to appraise and improve theoretical quality, both in relation to their own work and the HPE literature. While theory is the focus of this paper, we acknowledge it is one of many aspects that researchers have to concurrently balance and integrate into their work [ 7 ].

Consider theory comprehensively and critically

There are many different definitions of theory articulated in the HPE literature. These include theory as: an organised, coherent, and systematic articulation of a set of issues that are communicated as a meaningful whole [ 1 ]; a means of better understanding the mechanics of the research phenomena [ 3 ], a system of ideas intended to explain a phenomenon [ 8 ]; or a ‘philosophical stance informing the methodology’ [ 9 ]. These multiple definitions highlight that there are different interpretations about what theory is. For example, some regard theory as the underpinning philosophy or paradigm of a discipline which are the assumptions which underpin what a researcher does and why (we cover this in more detail later). Others, including ourselves, regard theory as a specific set of ideas or a lens that can be applied to examining and explaining phenomena. Furthermore, there are many different terms associated with theory [ 2 ] and interchangeable use of terminology. Therefore, we advise those new to HPE research to take time in the early stages of their research to clarify interpretations and terminology associated with theory and their own understandings of theory, through discussion with their supervisors/mentors, and research colleagues.

Given the range of theories available for use, we suggest ECRs seek guidance from supervisors/mentors and colleagues about what theories they use and see which theories are being discussed in their professional networks and social media. Once there is an initial level of familiarity, we advise ECRs to note which theories are being used in the primary HPE research literature (peer-reviewed journal articles) and grey literature (e.g., reports, conference presentations etc.) in the HPE field. To reduce the reliance on others’ interpretations of theory, it will also be important to engage with original sources of a chosen theory (or theories). To enhance inclusivity and diversity of theory [ 5 , 6 ], we advise ECRs to engage with theories from other disciplines (e.g., social psychology, sociology, education, philosophy, organisational, and economics etc.), cultures and geographical settings, and with theories that are less well-known in the HPE field. We also recommend ECRs collate, deconstruct, and discuss peer-reviewed examples of theory use. To demonstrate how to deconstruct theory use, we have taken a small sample of papers published in this journal and identified how theory is used in relation to paradigm, methodology, unit of analysis, timing of theory use, and write up of theory (See Table 2 ). Collectively, these strategies will help ECRs to identify and choose a theory (or multiple theories) that is fit for purpose.

As ECRs engage with theory, they will need to adopt a critical stance and ask questions both about theory as a subject/content area and the process of theory use. Questions that can be asked about theory as a subject/content area include: what are the origins of a particular theory; how has that theory evolved over time; and who is using that theory and how [ 14 ]? It is important to question theory because each theory: privileges a certain way of framing a research problem; is underpinned by certain assumptions; has different strengths and limitations [ 8 ]; and offers a different level of explanation and perspective [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 8 ]. Adopting a critical stance in relation to theory is also vital to decolonise and diversify research practices [ 5 , 6 ]. In order to effectively critique theory, we encourage ECRs to keep current with contemporary debates and discussions about theory and its use. So our first set of considerations (outlined in Table 1 ) relates to engaging comprehensively and critically with theory as a subject or content area.

Consider the alignment between paradigm and theory

A paradigm is a world view or a ‘philosophical way of thinking’ [ 15 ] which guides what a researcher does and why. It encompasses: values and assumptions about the nature of reality (ontology); how we come to know (epistemology); the research processes (methodology); and values (axiology) [ 16 , 17 ]. There is broad agreement that there are four main paradigms: positivism; post-positivism; constructivism/interpretivism; and critical theory [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Qualitative research is aligned with the post-positivist, constructivist/interpretivist, and critical paradigms, quantitative research corresponds to the positivst paradigm, and mixed methods research can involve a combination of all paradigms. A key element of HPE research relates to reflecting on and articulating one’s paradigm [ 17 ], ideally, at the time of designing a study.

Critically, ECRs are advised that although not every published study will explicitly name a paradigm, each study is situated within a specific philosophical milieu [ 20 ]. Furthermore, ECRs also need to understand that each theory itself is also underpinned by certain assumptions based not only on its disciplinary roots, but also its cultural roots [ 5 , 6 ]. For example, theories derived from psychology will differ from sociological theories in terms of their fundamental philosophical assumptions about phenomena and focus on understanding individuals and/or groups (psychological theories) and social groups, communities, and cultures (sociological theories). Similarly, theories from Western cultures may priviledge certain kinds of knowledge and perspectives over others [ 5 , 6 ]. Finally, although theory use is more prevalent in qualitative research, it can also be used in quantitative and mixed methods research as illustrated in the examples we have currated in Table 2 . This reinforces the importance of all HPE researchers having some understanding of theory and how to use it. Thus, our second set of considerations relate to considering the interplay between theory and paradigm (summarised in Table 1 ).

Consider the interplay between methodology and theory

Methodology refers to the research processes used in a study, encompassing methods of recruitment, data collection and data analysis. An important relationship exists between paradigm and methodology [ 17 ], and therefore between methodology and theory. As identified earlier, theory can be used in both qualitative and quantitative HPE research and different methodologies interact differently with theory. For example, traditional grounded theory as a methodology actively rejects pre-existing theory and regards theory development as an endpoint of the research [ 21 ]. In contrast, contemporary variants of grounded theory use pre-existing theory to inform the research [ 22 ]. Other qualitative methodologies such as hermeneutic phenomenology also use theory to focus the inquiry and explain findings [ 23 ]. So, in this context, we encourage ECRs to develop their awareness of the underpinning philosophical foundations of their chosen methodology and its stance on theory, and to engage with examples of published research to identify how others utilising a similar methodology have used theory. Therefore, our third set of considerations (summarised in Table 1 ) relates to engaging with theory in the context of methodology.

Consider the fit between theory and unit of analysis

There are two elements relating to the unit of analysis. Firstly, the unit of analysis pertains to the level at which a researcher is intending to examine a research phenomenon. Crotty’s [ 9 ] multi-level framework is a useful way to frame the different levels at which a phenomenon can be explored, which is at the level of the: individual or groups (micro-level); organisations/workplaces or medium sized networks (meso-level); or systems or large networks (macro-system). At the micro or individual level, the focus is mainly on the individual and their motivations, learning, performance, and development etc., and theories used at this level include mainly psychological and educational theories. At the micro-level, there can also be a focus on groups or small networks and their interactions, processes, social practices, identity etc., with social psychology, socio-cultural, sociological, social network theories being used. At the meso or organisational level, the focus is on structures and systems within organisations and mid-level networks, and organisational, cultural, socio-cultural, and ecological theories are commonly used at this level. At the macro level, there is a broader focus on systems and large networks, and theories used at this level can include activity theory, systems theory, and complexity theory etc.

Secondly, the unit of analysis can also pertain to whether a researcher is specifically seeking to unravel the impact of power, race, gender, politics, history and culture on phenomena (across micro, meso or macro levels). This would require the use of theories which are critical or emancipatory in nature, such as critical, feminist, intersectional, or postcolonial theory. As discussed earlier, using a critical or emancipatory lens can decolonise and diversify the theoretical knowledge and perspectives represented in the HPE literature [ 5 , 6 ]. By critically and deeply reflecting on their motivations and values with regards to a research study [ 17 ] ECRs can clarify their unit of analysis. As such, our fourth set of considerations (listed in Table 1 ) relates to identifying the alignment between unit of analysis and theory.

Consider when theory is used and associated implications

Theory can be used deductively or inductively [ 2 ]. When used deductively, theory guides all parts of the process, including conceptualisation, planning and execution of the research [ 2 ]. Using theory deductively requires ECRs to outline how the chosen theory has informed the framing of their research problem, the wording of the research aims and questions, and the methods of data collection and analysis. It is important for ECRs to understand that while the deductive approach implies there is a logical and linear way to use theory, initial theoretical understandings are often extended and adjusted as researchers engage in the research process. This includes the processes of collecting and analysing data, applying a theory, critically reflecting on the use of theory, writing up their work [ 2 ], and considering the interplay between pre-existing theory and emergent theory [ 21 ].

Theory can also be used inductively which involves applying it in the latter stages of data analysis [ 2 ]. With this approach, data is first interpreted in an open and exploratory manner using approaches like thematic analysis [ 24 ] or framework analysis [ 25 ] enabling the identification of preliminary themes. Then a theory-informed analysis is undertaken using a theory that is chosen based on preliminary impressions of the data and engagement with the literature. This inductive approach is also common in secondary analyses where researchers apply theory to interpret research data that has already been collected. With both deductive and inductive approaches, it is important for HPE researchers to show they have engaged critically and comprehensively with theory in justifying their choice of theory (or theories). As such, our fifth set of considerations (outlined in Table 1 ) relates to considering when theory is used in the research process and associated implications.

Consider the complexities of how theory is written up

In the HPE research manuscript, theory can be presented in three different ways. In some papers, theory is introduced and described in the Background/Introduction section as a way of framing the research, revisited in the Methods as part of the data collection and analysis, and explained further in the Discussion in terms of the contributions and implications of using theory. This approach is common in both studies where theory is used deductively or inductively, highlighting the complexities of balancing what was done in the research process (which is highly flexible and non-linear) and the reporting of a research study (which demands a logical and linear approach). We discuss this aspect later. In other papers, theory is first presented in the Methods section as a lens for data interpretation and then in the Discussion section as a way of considering the significance of findings and implications. This is common in studies using an inductive approach but may run the risk of reviewers critiquing the transparency and consistency of a paper [ 26 ]. Finally, entry-level research mostly only refers to theory in the Discussion section as a way of highlighting the implications of a study, but this approach does not fully leverage the possibilities offered by the use of theory [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ].

In reporting their work, researchers need to balance between what they have done in the research process (logic-in-use) with how they ‘formulate, articulate, analyse, or evaluate’ what they have done (reconstructed logic) [ 27 ]. Logic-in-use is a highly flexible and non-linear process involving juggling between the interrelated elements of ontology, epistemology, methodology, and axiology across the entire research process [ 9 ]. In contrast, reconstructed logic involves researchers developing linear and logical narratives about their work in which theory is often presented earlier as part of the framing of a study and separated from methodology and paradigm. Reconstructed logic means that even in studies where theory may have been used inductively and applied at the stage of data collection, a linear narrative can create an impression that the theory was known all along [ 28 ]. This highlights the complexities of balancing logic-in-use and reconstructed logic in the write-up phase. As advised earlier, consulting examples of original research articles can help ECRs to discern the different ways in which theory is presented in a research manuscript and how to report theory in a way that is fit for purpose for their research. So, our last set of considerations (outlined in Table 1 ) relates to considering the complexities of how theory is written up.

Using theory in HPE research holds significant benefits for the individual researcher, research teams and communities, and the discipline of HPE. Therefore upskilling in theory use is vital for all HPE researchers. We hope the guidance provided here supports new and emerging researchers across the globe to enhance their capacity to discern, enhance, and critique theoretical quality in HPE research.

Reeves S, Albert M, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ. 2008;337(7664):a949.

Article Google Scholar

Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med. 2020;95(7):989–94.

Samuel A, Konopasky A, Schuwirth LW, King SM, Durning SJ. Five principles for using educational theory: strategies for advancing health professions education research. Acad Med. 2020;95(4):518–22.

Rees C, Monrouxe L. Theory in medical education research: how do we get there? Med Educ. 2010;44(4):334–9.

Ajjawi R, Crampton PE, Ginsburg S, Mubuuke GA, Hauer KE, Illing J, et al. Promoting inclusivity in health professions education publishing. Med Educ. 2022;56(3):252–6.

Kusurkar RA. The leaky pipeline of publications and knowledge generation in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 2022;11(2):70–2.

Hammersley M. Theory and evidence in qualitative research. Qual Quant. 1995;29(1):55–66.

Laksov KB, Dornan T, Teunissen PW. Making theory explicit-An analysis of how medical education research (ers) describe how they connect to theory. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):18.

Crotty M. The Foundations of Social Research. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin; 1998.

Google Scholar

Horsburgh J, Ippolito K. A skill to be worked at: using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–8.

Held FP, Roberts C, Daly M, Brunero C. Learning relationships in community-based service-learning: a social network analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):113.

O’Keefe M, Wade V, McAllister S, Stupans I, Burgess T. Improving management of student clinical placements: insights from activity theory. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):219.

Ji YA, Nam SJ, Kim HG, Lee J, Lee S-K. Research topics and trends in medical education by social network analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):222.

Meyer S, Ward P. ‘How to’ use social theory within and throughout qualitative research in healthcare contexts. Sociol Compass. 2014;8(5):525–39.

Kuhn T. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1970.

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. p. 105–17.

Brown MEL, Dueñas AN. A medical science educator’s guide to selecting a research paradigm: building a basis for better research. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(1):545–53.

Bunniss S, Kelly DR. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med Educ. 2010;44(4):358–66.

Bergman E, de Feijter J, Frambach J, Godefrooij M, Slootweg I, Stalmeijer R, et al. AM last page: a guide to research paradigms relevant to medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):545.

Merriam S. Qualitative research: A Guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

Kennedy TJT, Lingard LA. Making sense of grounded theory in medical education. Med Educ. 2006;40(2):101–8.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006.

Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Ed. 2019;8(2):90–7.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117.

Roberts C, Kumar K, Finn G. Navigating the qualitative manuscript writing process: some tips for authors and reviewers. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:439.

Kaplan A. The conduct of inquiry: methodology for behavioral science. San Francisco: Chandler; 1964.

Carter SM, Little M. Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1316–28.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Prideaux Discipline of Clinical Education, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

Koshila Kumar

Education Office, Sydney Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Chris Roberts

Division of Medical Education, School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, The University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9NT, UK

Gabrielle M. Finn

Department of Emergency Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital; Chang Gung Medical Education Research Centre (CG-MERC) and School of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan

Yu-Che Chang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KK wrote the first draft. All other authors contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chris Roberts .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare they have no competing interests. All authors are or have been Associate or Section Editors for BMC Medical Education. No funding has been received for this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions