Reliability and validity: Importance in Medical Research

Affiliations.

- 1 Al-Nafees Medical College,Isra University, Islamabad, Pakistan.

- 2 Fauji Foundation Hospital, Foundation University Medical College, Islamabad, Pakistan.

- PMID: 34974579

- DOI: 10.47391/JPMA.06-861

Reliability and validity are among the most important and fundamental domains in the assessment of any measuring methodology for data-collection in a good research. Validity is about what an instrument measures and how well it does so, whereas reliability concerns the truthfulness in the data obtained and the degree to which any measuring tool controls random error. The current narrative review was planned to discuss the importance of reliability and validity of data-collection or measurement techniques used in research. It describes and explores comprehensively the reliability and validity of research instruments and also discusses different forms of reliability and validity with concise examples. An attempt has been taken to give a brief literature review regarding the significance of reliability and validity in medical sciences.

Keywords: Validity, Reliability, Medical research, Methodology, Assessment, Research tools..

Publication types

- Biomedical Research*

- Reproducibility of Results

- Joyner Library

- Laupus Health Sciences Library

- Music Library

- Digital Collections

- Special Collections

- North Carolina Collection

- Teaching Resources

- The ScholarShip Institutional Repository

- Country Doctor Museum

Evidence-Based Practice for Nursing: Evaluating the Evidence

- What is Evidence-Based Practice?

- Asking the Clinical Question

- Finding Evidence

- Evaluating the Evidence

- Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN

Evaluating Evidence: Questions to Ask When Reading a Research Article or Report

For guidance on the process of reading a research book or an article, look at Paul N. Edward's paper, How to Read a Book (2014) . When reading an article, report, or other summary of a research study, there are two principle questions to keep in mind:

1. Is this relevant to my patient or the problem?

- Once you begin reading an article, you may find that the study population isn't representative of the patient or problem you are treating or addressing. Research abstracts alone do not always make this apparent.

- You may also find that while a study population or problem matches that of your patient, the study did not focus on an aspect of the problem you are interested in. E.g. You may find that a study looks at oral administration of an antibiotic before a surgical procedure, but doesn't address the timing of the administration of the antibiotic.

- The question of relevance is primary when assessing an article--if the article or report is not relevant, then the validity of the article won't matter (Slawson & Shaughnessy, 1997).

2. Is the evidence in this study valid?

- Validity is the extent to which the methods and conclusions of a study accurately reflect or represent the truth. Validity in a research article or report has two parts: 1) Internal validity--i.e. do the results of the study mean what they are presented as meaning? e.g. were bias and/or confounding factors present? ; and 2) External validity--i.e. are the study results generalizable? e.g. can the results be applied outside of the study setting and population(s) ?

- Determining validity can be a complex and nuanced task, but there are a few criteria and questions that can be used to assist in determining research validity. The set of questions, as well as an overview of levels of evidence, are below.

For a checklist that can help you evaluate a research article or report, use our checklist for Critically Evaluating a Research Article

- How to Critically Evaluate a Research Article

How to Read a Paper--Assessing the Value of Medical Research

Evaluating the evidence from medical studies can be a complex process, involving an understanding of study methodologies, reliability and validity, as well as how these apply to specific study types. While this can seem daunting, in a series of articles by Trisha Greenhalgh from BMJ, the author introduces the methods of evaluating the evidence from medical studies, in language that is understandable even for non-experts. Although these articles date from 1997, the methods the author describes remain relevant. Use the links below to access the articles.

- How to read a paper: Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about) Not all published research is worth considering. This provides an outline of how to decide whether or not you should consider a research paper. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997b). How to read a paper. Getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7102), 243–246.

- Assessing the methodological quality of published papers This article discusses how to assess the methodological validity of recent research, using five questions that should be addressed before applying recent research findings to your practice. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997a). Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7103), 305–308.

- How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests This article and the next present the basics for assessing the statistical validity of medical research. The two articles are intended for readers who struggle with statistics more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997f). How to read a paper. Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data need different statistical tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7104), 364–366.

- How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician II: "Significant" relations and their pitfalls The second article on evaluating the statistical validity of a research article. more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997). Education and debate. how to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: "significant" relations and their pitfalls. BMJ: British Medical Journal (International Edition), 315(7105), 422-425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7105.422

- How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997d). How to read a paper. Papers that report drug trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7106), 480–483.

- How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997c). How to read a paper. Papers that report diagnostic or screening tests. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7107), 540–543.

- How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997e). How to read a paper. Papers that tell you what things cost (economic analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7108), 596–599.

- Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) more... less... Greenhalgh, T. (1997i). Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7109), 672–675.

- How to read a paper: Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research) A set of questions that could be used to analyze the validity of qualitative research more... less... Greenhalgh, T., & Taylor, R. (1997). Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 315(7110), 740–743.

Levels of Evidence

In some journals, you will see a 'level of evidence' assigned to a research article. Levels of evidence are assigned to studies based on the methodological quality of their design, validity, and applicability to patient care. The combination of these attributes gives the level of evidence for a study. Many systems for assigning levels of evidence exist. A frequently used system in medicine is from the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine . In nursing, the system for assigning levels of evidence is often from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's 2011 book, Evidence-based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice . The Levels of Evidence below are adapted from Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt's (2011) model.

Uses of Levels of Evidence : Levels of evidence from one or more studies provide the "grade (or strength) of recommendation" for a particular treatment, test, or practice. Levels of evidence are reported for studies published in some medical and nursing journals. Levels of Evidence are most visible in Practice Guidelines, where the level of evidence is used to indicate how strong a recommendation for a particular practice is. This allows health care professionals to quickly ascertain the weight or importance of the recommendation in any given guideline. In some cases, levels of evidence in guidelines are accompanied by a Strength of Recommendation.

About Levels of Evidence and the Hierarchy of Evidence : While Levels of Evidence correlate roughly with the hierarchy of evidence (discussed elsewhere on this page), levels of evidence don't always match the categories from the Hierarchy of Evidence, reflecting the fact that study design alone doesn't guarantee good evidence. For example, the systematic review or meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are at the top of the evidence pyramid and are typically assigned the highest level of evidence, due to the fact that the study design reduces the probability of bias ( Melnyk , 2011), whereas the weakest level of evidence is the opinion from authorities and/or reports of expert committees. However, a systematic review may report very weak evidence for a particular practice and therefore the level of evidence behind a recommendation may be lower than the position of the study type on the Pyramid/Hierarchy of Evidence.

About Levels of Evidence and Strength of Recommendation : The fact that a study is located lower on the Hierarchy of Evidence does not necessarily mean that the strength of recommendation made from that and other studies is low--if evidence is consistent across studies on a topic and/or very compelling, strong recommendations can be made from evidence found in studies with lower levels of evidence, and study types located at the bottom of the Hierarchy of Evidence. In other words, strong recommendations can be made from lower levels of evidence.

For example: a case series observed in 1961 in which two physicians who noted a high incidence (approximately 20%) of children born with birth defects to mothers taking thalidomide resulted in very strong recommendations against the prescription and eventually, manufacture and marketing of thalidomide. In other words, as a result of the case series, a strong recommendation was made from a study that was in one of the lowest positions on the hierarchy of evidence.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Quantitative Questions

The pyramid below represents the hierarchy of evidence, which illustrates the strength of study types; the higher the study type on the pyramid, the more likely it is that the research is valid. The pyramid is meant to assist researchers in prioritizing studies they have located to answer a clinical or practice question.

For clinical questions, you should try to find articles with the highest quality of evidence. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses are considered the highest quality of evidence for clinical decision-making and should be used above other study types, whenever available, provided the Systematic Review or Meta-Analysis is fairly recent.

As you move up the pyramid, fewer studies are available, because the study designs become increasingly more expensive for researchers to perform. It is important to recognize that high levels of evidence may not exist for your clinical question, due to both costs of the research and the type of question you have. If the highest levels of study design from the evidence pyramid are unavailable for your question, you'll need to move down the pyramid.

While the pyramid of evidence can be helpful, individual studies--no matter the study type--must be assessed to determine the validity.

Hierarchy of Evidence for Qualitative Studies

Qualitative studies are not included in the Hierarchy of Evidence above. Since qualitative studies provide valuable evidence about patients' experiences and values, qualitative studies are important--even critically necessary--for Evidence-Based Nursing. Just like quantitative studies, qualitative studies are not all created equal. The pyramid below shows a hierarchy of evidence for qualitative studies.

Adapted from Daly et al. (2007)

Help with Research Terms & Study Types: Cut through the Jargon!

- CEBM Glossary

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine|Toronto

- Cochrane Collaboration Glossary

- Qualitative Research Terms (NHS Trust)

- << Previous: Finding Evidence

- Next: Articles, Books & Web Resources on EBN >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 10:03 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ecu.edu/ebn

Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Reliability

Nursing Resources : Reliability

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Table of Evidence

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

Difference Between Reliability and Validity

Validity related to the data collection instrument (such as a questionnaire or interview).

Reliability: This usually has to do with HOW the data were collected. (Remember "data" is always plural!)

Research Rundowns

- Instrument, Validity, Reliability Instruments fall into two broad categories, researcher-completed and subject-completed, distinguished by those instruments that researchers administer versus those that are completed by participants. Researchers chose which type of instrument, or instruments, to use based on the research question.

What is "Reliability?"

Reliability has to do with the quality of measurement. In its everyday sense, reliability is the "consistency" or "repeatability" of your measures. Before we can define reliability precisely we have to lay the groundwork. First, you have to learn about the foundation of reliability, the true score theory of measurement .

Along with that, you need to understand the different types of measurement error because errors in measures play a key role in degrading reliability. With this foundation, you can consider the basic theory of reliability , including a precise definition of reliability. There you will find out that we cannot calculate reliability -- we can only estimate it.

Because of this, there a variety of different types of reliability that each have multiple ways to estimate reliability for that type. In the end, it's important to integrate the idea of reliability with the other major criteria for the quality of measurement -- validity -- and develop an understanding of the relationships between reliability and validity in measurement .

- << Previous: Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Next: Validity Threats >>

- Last Updated: Mar 19, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/nursing

- Open access

- Published: 22 April 2024

Developing and validating the nurse-patient relationship scale (NPRS) in China

- Yajie Feng 1 na1 ,

- Chaojie Liu 3 ,

- Siyi Tao 1 , 8 ,

- Chen Wang 1 , 6 ,

- Huanyu Zhang 1 ,

- Xinru Liu 1 na1 ,

- Zhaoyue Liu 1 na1 ,

- Wei Liu 1 ,

- Juan Zhao 1 , 5 ,

- Dandan Zou 1 , 7 ,

- Zhixin Liu 1 , 4 ,

- Junping Liu 1 ,

- Nan Wang 1 ,

- Qunhong Wu 1 ,

- Yanhua Hao 1 ,

- Weilan Xu 2 &

- Libo Liang 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 255 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

176 Accesses

Metrics details

Poor nurse-patient relationship poses an obstacle to care delivery, jeopardizing patient experience and patient care outcomes. Measuring nurse-patient relationship is challenging given its multi-dimensional nature and a lack of well-established scales.

This study aimed to develop a multi-dimensional scale measuring nurse-patient relationship in China.

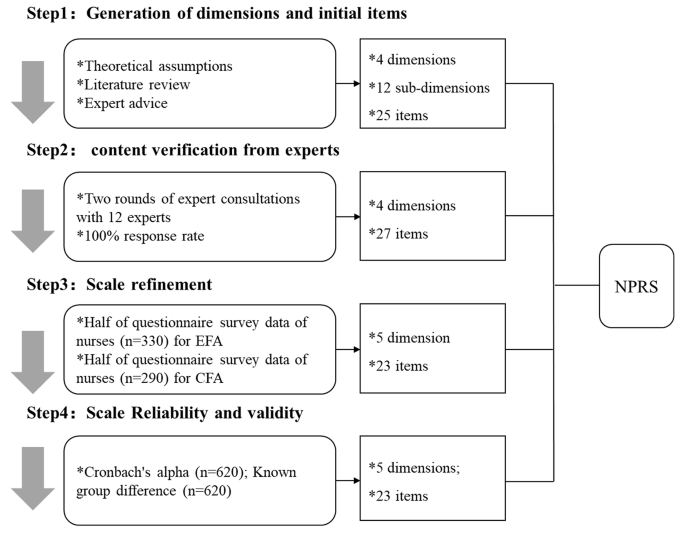

A preliminary scale was constructed based on the existing literature and Delphi consultations with 12 nursing experts. The face validity of the scale was tested through a survey of 45 clinical nurses. This was followed by a validation study on 620 clinical nurses. Cronbach’s α, content validity and known-group validity of the scale were assessed. The study sample was further divided into two for Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), respectively, to assess the construct validity of the scale.

The Nurse-Patient Relationship Scale (NPRS) containing 23 items was developed and validated, measuring five dimensions: nursing behavior, nurse understanding and respect for patient, patient misunderstanding and mistrust in nurse, communication with patient, and interaction with patient. The Cronbach’s α of the NPRS ranged from 0.725 to 0.932, indicating high internal consistency. The CFA showed excellent fitness of data into the five-factor structure: χ 2 /df = 2.431, GFI = 0.933, TLI = 0.923, CFI = 0.939, IFI = 0.923, RMSEA = 0.070. Good content and construct validity are demonstrated through expert consensus and psychometric tests.

The NPRS is a valid tool measuring nurse-patient relationship in China.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

At present, nurse-patient disputes are common, and a large number of reports focus on the relationship and conflicts between nurses and patients. Despite efforts to alleviate the strained relationship between nurses and patients, it still persists [ 1 ]. Patients are usually considered as a passive subject [ 2 , 3 ]. Research points out that many patients, or most of them, are not able to engage in care for themselves through effective interactions with health workers [ 4 ]. Henderson [ 5 ] noted that professional domination over patient care causes depersonalization and, consequently, worsening of the relationship between the nurse and the patient [ 2 , 6 ].

A positive nurse-patient relationship is fundamental for effective and high-quality nursing care. The importance of defining and evaluating the connotation of the nurse-patient relationship has been well-established, with a variety of theories being proposed [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Some scholars define it as a kind of interpersonal relationship in the process of providing and receiving nursing services. Nurses and patients learn and encourage each other, naturally forming a relationship of helping and being helped [ 10 ]. Others see it as instrumental, primarily reflecting the help nurses provide to patients [ 11 ]. From the perspective of nurses, a positive nurse-patient relationship allows them to effectively plan, provide, and evaluate nursing services. For patients, the caring consciousness, wisdom, and interpersonal skills of nurses are essential for developing and maintaining a continuous nurse-patient relationship [ 12 ]. Clinical and interpersonal skills are the two equally important pillars of patient-centered nursing practice [ 13 ].

It is critical for nurses to form a positive attitude towards patients that involves respect, trust, and understanding to enable effectively communication and delivery of the help and guidance needed by the patients [ 14 ]. Empirical evidence suggests that the tension between nurses and patients is associated with a lack of respect and understanding of nursing care from patients. Some patients or the public may hold inherent prejudices toward the status and nature of nursing work, resulting in a lack of respect and understanding for nurses [ 15 ]. This can manifest in behaviors such as not treating nurses with respect or understanding their role. In some extreme cases, patients may resort to verbal and even physical violence against nurses, which can have a negative impact on the nurse-patient relationship. As a result, the nurses may be unable to provide high-quality nursing services [ 16 ].

A reliable tool measuring nurse-patient relationship can not only help to better understand the nursing care process, but also predict patient experience and care outcomes [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. However, the existing validated tools measuring the nurse-patient relationship have several limitations. Firstly, there is a lack of comprehensiveness, with most focusing on specific selected aspects of the nurse-patient relationship, such as trust [ 17 , 18 ], social interaction [ 19 ], and care behavior [ 20 ]. Secondly, there exists ambiguity in the conceptualization of the elements measured by the existing tools: for example, “respect” can be regarded as an attribute of trust [ 21 ] or nursing behavior [ 20 , 22 ]. Thirdly, the existing tools have failed to consider the special circumstances of nursing work environments in China. The hierarchical and collectivist culture in China has significant implications for how nurses work with their patients and colleagues. Nurses often become an easy target for patient complaints although system problems are usually the underlying reasons [ 23 ]. Therefore, there is a need to develop a measurement tool that can capture the complex nature of nurse-patient relationship, especially under the context of the Chinese health system [ 24 ].

This study aimed to address the gap in the literature by developing and validating a scale that measures the nurse-patient relationship comprehensively from the perspective of nurses in China, guided by existing theories and considering the existing measurement tools.

The study followed the best practice in scale development [ 25 ], which involved four steps: item generation, content verification, scale refinement, and reliability and validity assessment (Fig. 1 ).

Four steps in scale development. (Note: EFA– Exploratory Factor Analysis; CFA– Confirmatory Factor Analysis; NPRS– Nurse-Patient Relationship Scale)

The study was conducted in Heilongjiang, a province with a socioeconomic development index at the lower end range in China. In 2019, Heilongjiang had 26 nurses per 10,000 population, compared with a national average of 32 [ 26 ].

Item generation

The concept of nurse-patient relationship was defined as a therapeutic relationship in line with Peplau’s interpersonal relationship theory. Nurses play a variety of roles in helping patients, ranging from a communicator to a caregiver [ 12 ]. At the core of the relationship is trust, communication, mutual understanding, and clinical care. Halldorsdottir (2008) likened the two extremes of nurse-patient relationship as “bridge” and “wall” [ 27 ]. “Bridge” symbolizes openness of communication and connectivity felt by patients in their relationship with nurses. It represents patient-centeredness and easy access to nursing services. By contrast, “wall” symbolizes a lack of communication and indifference of nurses to patient demands, as well as mistrust between the two parties [ 27 ]. The items generated in this study covered both “wall” and “bridge” aspects in relation to trust, communication, understanding, and clinical care.

The sources of items came from a cascading decomposition of the aforementioned theoretical assumptions, a review of the existing measurement tools, and descriptive adaptation to the local health system and clinical practices. A total of 12 sub-domains were mapped into the four core functions of nurse-patient relationship through the process, with advisory support from six external experts who had complementary knowledge and expertise to the research team (Table 1 ).

Content verification - Delphi consultations

The Delphi method is one of the most commonly used procedures to establish content validity of a scale [ 28 ]. In this study, eligible participants of the Delphi consultations were the experts with a background of nursing research, clinical nursing, or psychology. A minimal of ten years of work experience in the relevant areas was required. The participants were recruited through a stratified convenience sampling strategy. In total, 12 experts from eight provinces participated in the Delphi consultations, covering the eastern developed, the central developing, and the western under-developed regions in China. Half of them worked in academic institutions and half in the healthcare industry.

The participants were invited to respond to the consultation questionnaire by email in December 2019. They were asked to rate the relative importance of each sub-domain on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree), and the relevance of each item to its respective sub-domain on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not relevant) to 5 (essential). Suggestions about modification, removal, or addition of items, sub-domains, and domains were also encouraged. Participation in the consultations was voluntary and verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Consensus of the expert ratings was indicated by the percentage of agreement. The items/sub-domains that had a higher than 80% expert agreement and an over 4 average score were retained [ 29 ]. Two rounds of consultations were conducted. The first round resulted in some changes in the subdomains and items, although the four core functions (domains) remained unchanged. In round two, feedback of the round one results was provided, which included the rating results and the corresponding changes made such as removal, addition, and modification of items, sub-domains, and domains. Participants were asked to reconsider their ratings if needed. The 12 experts completed both rounds of consultations.

We also calculated the item content validity index (I-CVI) and the scale content validity index (S-CVI)/average: I-CVI > 0.78 and (S-CVI)/average of 0.90 or higher were deemed acceptable [ 30 , 31 ].

Pilot testing

The NPRS endorsed by the experts was tested in a convenience sample of 45 nurses selected from the clinical units (mainly internal medicine, surgery, ICU, and stomatology) of a tertiary hospital in Harbin, capital of Heilongjiang province. Participants were asked to self-complete the paper questionnaire independently. Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale reached 0.795. No further changes were made as a result of the pilot testing.

Reliability and validity assessment

Reliability and validity of the NPRS were assessed through a questionnaire survey of clinical nurses in a public tertiary hospital in Qiqihar city in Heilongjiang province. The hospital employed 1093 clinical nurses who had direct contacts with patients. From 29 to 31 December 2019, the nurses working in the clinical units were invited to participate in the survey. Participation in the survey was anonymous and voluntary. Return of the questionnaire was deemed informed consent. In total, 721 questionnaires were distributed and 708 (86.5%) were returned. After removal of the invalid returned questionnaires, 620 (86.0%) were included for data analysis, representing 56.7% of the entire nursing workforce in the participating hospital.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval for the study protocol was granted by the research ethics committee of Harbin Medical University.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 and AMOS 24.0. A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A pairwise strategy was adopted in managing missing values.

Each item of the NPRS was rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The direction of item scores was aligned before a summed score was calculated for each domain and the entire scale, with a higher score indicating a more positive nurse-patient relationship.

Construct validity was tested through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The study sample was randomly divided into two mutually independent sub-samples, with 330 participants for EFA and 290 participants for CFA, respectively. The appropriateness of factor analyses was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure (KMO ≥ 0.50) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity ( p < 0.05) [ 32 ]. The EFA extracted factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1 using principal component analysis (PCA) with maximal rotation of variance. This allowed us to identify and eliminate poorly-fitted items, including those with a low factor load (< 0.4) on all factors and those with a high load (≥ 0.4) across multiple factors [ 33 ]. The CFA then assessed the fitness of data into the adjusted scale resulting from the EFA. A good model fit was indicated by Chi-square/degree of freedom (χ 2 /df ratio ranging from 1 to 3), goodness-of-fit index (GFI > 0.9), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08), a root mean square residual (RMR < 0.08), a comparative fit index (CFI > 0.9), a normalized fit index (NFI > 0.9), and Incremental Fit Index (IFI > 0.9) [ 34 ]. Convergent validity was assessed by composite reliability (CR > 0.70) [ 35 ] and average variance extracted (AVE > 0.5) from CFA [ 36 ]. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing AVE with the Pearson correlation coefficients between domains: A good discriminant validity is indicated if the square root of AVE of each construct is greater than its correlations with the rest of the constructs [ 37 , 38 ].

Reliability was assessed by Cronbach’s α for the entire NPRS and its domains using the entire sample. A greater than 0.7 Cronbach’s α coefficient indicates good internal consistency [ 39 ].

Known-group validity was tested through student t tests using the entire sample, with a hypothesis that nurse-patient relationship varies by the personal characteristics of the nurse [ 40 , 41 ].

Content validity

Characteristics of delphi participants.

About one third of the participants of the Delphi consultations came from Heilongjiang province and over 40% aged between 30 and 40 years. Half held a doctoral degree and had more than 20 years of work experience. Over 58% of participants held a senior professional title (Table 2 ).

Results of Delphi consultations

The first round of consultations resulted in an increase of items from 25 to 27: five new items were suggested while three were removed (Table 3 ). The three items that were suggested by some experts for removal all had low levels of expert agreement. Wording changes were also suggested by the experts for nine items to reduce ambiguity and improve clarity (Supplementary Table 1 ). The four core functions (domains) remained unchanged.

The first round of Delphi consultations already achieved an I-CVI of 0.83 (22/25) and an (S-CVI)/average of 0.98, exceeding the recommended value.

The second round of consultations led to language modification of two items. One item was removed because it failed to reach agreement among the experts in both rounds of consultations (Table 2 ). This resulted in a final version of the NPRS, containing 26 items, measuring nurse patient understanding and respect (8 items), nurse-patient trust (4 items), nurse-patient communication (8 items), and nurse’s help and guidance to patients (6 items). The second round of Delphi consultations already achieved an I-CVI of 0.83 (22/26) and an (S-CVI)/average of 0.99, exceeding the recommended value.

Construct validity

Characteristics of survey participants.

Of the 620 clinical nurses surveyed, 88.1% were female and 46.0% aged between 26 and 35 years. Most were married (53.2%), obtained a university degree (59.0%), and worked in internal medicine (55.6%). Almost half (49.0%) had over five years of work experience and 70.6% held an intermediate or senior professional title. The two sub-divided samples had slightly different characteristics of study participants (Table 4 ).

Structural adjustment of the scale

The KMO (0.903) and Bartlett test of sphericity ( p < 0.001) indicated appropriateness of the subsample ( n = 330) for EFA. The EFA extracted five factors: nursing behavior ; nurse understanding and respect for patient; patient misunderstanding and mistrust; communication with patient; and interaction with patient. The five factors explained 68.06% of the total variance. Three items (item N7, N9, N16) with low factor loadings or cross loadings were removed, resulting in a 23-item NPRS (Table 5 ). The complete NPRS scale is shown in supplementary Table S3 .

The KMO (0.902) and Bartlett test of sphericity ( p < 0.001) indicated appropriateness of the subsample ( n = 290) for CFA. Excellent fitness of data into the five-factor structure in line with the EFA was found: χ 2 /df = 2.431, GFI = 0.933, TLI = 0.923, CFI = 0.939, IFI = 0.923, and RMSEA = 0.070. The vast majority of items had a factor loading greater than 0.70 on its respective domain (Supplementary Table S2 ).

Convergent and discriminatory validity

Convergent validity of the scale was confirmed by the CFA ( n = 290), as indicated by the greater than 0.7 CR and greater than 0.5 AVE (Table 6 ).

The five domains were moderately correlated. The square root of the AVE value of each domain generated from the CFA ( n = 290) was much greater than its correlation coefficients with other domains (Table 6 ), indicating good discriminant validity between dimensions.

Cronbach’s α

High levels of internal consistency were found for the entire scale and its five domains, as indicated by the higher than 0.7 Cronbach’α coefficients (Table 7 ).

Known group validity

There were statistically significant differences in the NPRS scores by gender and working experience (Table 8 ). Male nurses had lower scores (indicating poorer relationship) in two domains: patient misunderstanding and mistrust in nurse, and communication with patients, compared to female nurses ( p < 0.01). Longer work experience was associated with higher scores (indicating better relationship) in two domains: nurse understanding and respect for patients, and interaction with patients ( p < 0.05). Patient complaint was associated with a lower score (indicating poorer relationship) in one domain (patient misunderstanding and mistrust in nurse) despite a lack of significance in the difference of overall NPRS scores.

Discussion and conclusions

The current research represents an attempt to provide a clear conceptualization and a reliable and valid scale measuring the comprehensive nurse-patient relationship in China. This research closely followed the best practice in scale development, involving a series studies covering the generation of dimensions and initial items, verification of the content, refinement of the scale, and reliability and validity testing of the scale. Previous studies have endeavored to assess the nurse-patient relationship through specific theories [ 18 , 46 , 47 ]. The nurse-patient relationship is indeed multifaceted. From a practical standpoint, no single theory can entirely encapsulate the nature of the nurse-patient relationship. The nurse-patient relationship scale developed in this current study offers a comprehensive tool by incorporating and refining dimensions and items derived from previous studies.

The results showed that the NPRS developed by our research has good reliability and validity. It supports a multi-dimensional construct, with Cronbach’s alpha of the scale and its five domains well exceeding the acceptable value of 0.7. Good content and construct validity are demonstrated through expert consensus and psychometric tests.

The NPRS has captured all of the essential elements of nurse-patient relationship as measured by the existing measurement tools, including trust [ 18 , 48 ], communication and interaction [ 46 , 49 , 50 , 51 ], and respect and humanistic care [ 47 ]. It covers both positive and negative behavioral reflections of the nurse-patient relationship, and puts nursing responsiveness, care process, and care outcomes at the core of the relationship. Mutual understanding, trust and respect provide the foundation for a positive nurse-patient relationship [ 27 ], which enables positive behaviors and interactions between the two to ensure good care outcomes.

The NPRS can help managers and policymakers to better respond to the call for patient-centered care. Increasing tensions in the relationship between nurses and patients due to various reasons have been observed worldwide [ 52 ], prompting calls for improving work and cultural environments. In this current study, we found that patient complaints are associated with poorer nurse-patient relationship, characterized by patient misunderstanding and distrust in nurses. Indeed, experiencing patient complaints reduces job satisfaction and the quality of working life of nurses [ 53 ]. Nurses facilitate care through frequent and direct contact with patients and their families in almost all healthcare settings, particularly in hospitals [ 54 ]. Patient demands and expectations have never been so high due to the rapid technological advancement and increased affordability of care [ 55 ]. What follows is the increase in the workload and the high pressure imposed on nurses [ 56 ]. Constant and chronic occupational stress produce burnout, a prominent characteristic of nursing work [ 57 ]. Study shows that the inverse relationship between physician burnout and patient safety affects nurse-patient relationship [ 58 ]. On the other hand, patients may take improved care outcomes for granted [ 59 ]. Therefore, it is important to use a tool, such as the NPRS, to help nurses and their managers to identify key domains in the nurse-patient relationship for improvement.

Our findings have some policy implications on the current health system reform in China. We found that the male nurses have worse relationship with patients than their female counterparts. This may reflect the structural inequality in gender division of work: Female nurses take most of the care tasks [ 60 ]. Female nurses may be more sensitive than their male counterparts, have stronger empathy, communication and caring characteristics, and pay more attention to emotional communication [ 61 ]. A study on the humanistic care of male nurses showed that male nurses expressed humanistic care differently from female nurses. Female nurses were more inclined to use their unique mother-like image to care for patients, while male nurses mostly used professional behaviors to care for patients [ 62 ]. There is a need to address the gender inequality and strengthen the communication competency of male nurses.

In the current study, we found that longer work experience is associated with a better nurse-patient relationship, in terms of nurse understanding and respect for patient and interaction with patient. Benner argues that rich life experience and increased situation awareness can help nurses to better manage nurse-patient relationship [ 63 ]. Empirical evidence shows that nursing students can obtain both professional and personal growth, such as a rise in confidence and self-esteem, through accumulated experience in interactions with patients [ 64 ]. However, professional and managerial support is equally, if not more, important to enable nurses to excel in managing nurse-patient relationship. As indicated in the findings of this current study, longer work experience does not appear to improve nurse behavior, patient misunderstanding and mistrust in nurse, and communication with patient.

The current study has some limitations. The study sample was drawn from one hospital. Future studies should expand participants to a more representative sample. It is also important to examine the tool from patient perspective. The NPRS was developed under the context of the Chinese health system. Cross-cultural adaptation is needed should it be used in different health system settings.

The 23-item NPRS is a valid tool measuring the comprehensive relationship between nurses and patients under the context of the Chinese health system. It measures five domains: nursing behavior, nurse understanding and respect for patient, patient misunderstanding and mistrust in nurse, communication with patient, and interaction with patient. The NPRS presents an opportunity for nurses and their managers to reflect and identify key domains in nurse-patient relationship for improvement. Healthcare practitioners and policymakers can utilize this tool to pinpoint crucial areas for enhancing the development of a trusting and productive nurse-patient relationship.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ferri P, Silvestri M, Artoni C, et al. Workplace violence in different settings and among various health professionals in an Italian general hospital: a cross-sectional study[J]. Psychol Res Behav Manage. 2016;9:263–75.

Article Google Scholar

Cahill J. Patient participation–a review of the literature[J]. J Clin Nurs. 1998;7(2):119–28.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Truglio-Londrigan M. The patient experience with Shared decision making: a qualitative descriptive study[J]. J Infus Nurs. 2015;38(6):407–18.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Grffith R, Tengnah C. Shared decision-making: nurses must respect autonomy over paternalism[J]. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;18(6):303–6.

Henderson S. Power imbalance between nurses and patients: a potential inhibitor of partnership in care[J]. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(4):501–8.

Malaquin-Pavan E. [Is nursing care an intrusion? [J]. Soins, 2015(794):21.

Feo R, Rasmussen P, Wiechula R, et al. Developing effective and caring nurse-patient relationships[J]. Nurs Standard (Royal Coll Nurs (Great Britain): 1987). 2017;31(28):54–63.

Hagerty BM, Patusky KL. Reconceptualizing the nurse-patient relationship[J]. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2003;35(2):145–50.

Molina-Mula J, Gallo-Estrada J. Impact of nurse-patient relationship on quality of care and patient autonomy in Decision-Making[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020,17(3).

Genoveva GG. The nurse-patient relationship as a Caring Relationship[J]. Nurs Sci Q, 2009,22(2).

Book Review: Nursing Theorists and Their Work (4th ed.) Edited by Ann Marriner Tomey and Martha Raile Alligood (St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby. 1998 Reviewed by Burns Nancy, RN; PhD; FAAN Professor, The University of Texas at Arlington[Z]. United States: 1999;12:263.

Interpersonal relations in nursing[J].

Feo R, Rasmussen P, Wiechula R, et al. Developing effective and caring nurse-patient relationships[J]. Nurs Stand. 2017;31(28):54–63.

Dithole KS, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Akpor OA, et al. Communication skills intervention: promoting effective communication between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients[J]. BMC Nurs. 2017;16(1):74.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhao S, Xie F, Wang J, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against Chinese nurses and its association with mental health: a cross-sectional survey[J]. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(2):242–7.

Bridges J, Nicholson C, Maben J, et al. Capacity for care: meta-ethnography of acute care nurses’ experiences of the nurse-patient relationship[J]. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(4):760–72.

Radwin LE, Cabral HJ. Trust in nurses Scale: construct validity and internal reliability evaluation[J]. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(3):683–9.

Ozaras G, Abaan S. Investigation of the trust status of the nurse-patient relationship[J]. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25(5):628–39.

Rask M, Malm D, Kristofferzon ML, et al. Validity and reliability of a Swedish version of the relationship assessment scale (RAS): a pilot study[J]. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;20(1):16–21.

PubMed Google Scholar

Wu Y, Larrabee JH, Putman HP. Caring behaviors inventory: a reduction of the 42-Item instrument[J]. Nurs Res. 2006;55(1):18–25.

Zhao Ling W, Rong ZHU, Chenhui. Revision of nurse-patient relationship trust scale and test of reliability and validity [J]. J Nurs Sci. 2018;33(01):56–8.

Google Scholar

He Ting G, Yingying L, Xiaohong, et al. Sinicization and validity test of nursing behavior scale [J]. Shanghai Nurs. 2021;21(01):6–9.

Liu C, Bartram T, Leggat SG. Link of patient care outcome to occupational differences in response to human resource management: a cross-sectional comparative study on hospital doctors and nurses in China[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020,17(12).

Feo R, Conroy T, Wiechula R, et al. Instruments measuring behavioural aspects of the nurse–patient relationship: a scoping review[J]. J Clin Nurs. 2019;29(11–12):1808–21.

Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, et al. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a Primer[J]. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

National Bureau of Statistics. https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=E0103&zb=A0O02®=230000&sj=2019 .

Halldorsdottir S. The dynamics of the nurse-patient relationship: introduction of a synthesized theory from the patient’s perspective[J]. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(4):643–52.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique[J]. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15.

Bing-Jonsson PC, Bjork IT, Hofoss D, et al. Competence in advanced older people nursing: development of ‘nursing older people–competence evaluation tool‘[J]. Int J Older People Nurs. 2015;10(1):59–72.

Timmins F. Nursing Research Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, Polit DF, Tatano Beck C. Lippincott Williams & Williams, London, ISBN: 978-1-60547-708-4 - scienceD[J]. Nurse Education in Practice. 2012;13(6).

Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations[J]. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–97.

Kang H. [A guide on the use of factor analysis in the assessment of construct validity[J]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2013;43(5):587–94.

WeiLong Z, Shaozhuang M, Li G. Development and validation of doctor-patient relationship scale in China[J]. Health Qual Manage. 2018;25(06):57–61.

Structural Model Evaluation and Modification. An Inverted Estimation Approach[J].

Wynne WC, Barbara LM, Peter RN. A partial least squares Latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study[J]. Inform Syst Res, 2003,14(2).

Richard PB. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: a comment[J]. J Mark Res. 1981;18(3).

Fuller CM, Simmering MJ, Atinc G, et al. Common methods variance detection in business research[J]. J Bus Res. 2016;69(8):3192–8.

Li C, Jiang Y. Measurement model improvement of organizational memory: the development and validation of local scaling[J]. Res Financial Economic Issues, 2012(10):17–24.

Multivariate. Date Analysis[M].

Moriconi S, Balducci PM, Tortorella A. Aggressive behavior: nurse-patient relationship in mental health setting[J]. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(Suppl 1):207–9.

Boge LA, Dos SC, Moreno-Walton LA, et al. The relationship between physician/nurse gender and patients’ correct identification of health care professional roles in the emergency department[J]. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(7):961–4.

Hildegard P. Interpersonal Relation of Nursing[J]. 1952.

Cronin SN, Harrison B. Importance of nurse caring behaviour as perceived by patients after myocardial infarction[J]. Heart Lung J Acute Crit Care. 1988;17(4):374–80.

CAS Google Scholar

岡谷恵子. 看護婦-患者関係における信頼を測定する質問紙 の 開発-信頼性 妥当性 の 検定[J]. 1994 年度聖路加看護大学大学院博士論文, 1994.[Z].

Boscart VM, Pringle D, Peter E, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the humanistic nurse-patient scale[J]. Can J Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement. 2016;35(01):1–13.

Dithole KS, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G, Akpor OA, et al. Communication skills intervention: promoting effective communication between nurses and mechanically ventilated patients[J]. BMC Nurs. 2017;16:74.

Boscart VM, Pringle D, Peter E, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the humanistic nurse-patient scale[J]. Can J Aging. 2016;35(1):1–13.

Burge DM. Relationship between patient trust of nursing staff, postoperative pain, and discharge functional outcomes following a total knee arthroplasty[J]. Orthop Nurs. 2009;28(6):295–301.

Fakhr-Movahedi A, Rahnavard Z, Salsali M, et al. Exploring nurse’s communicative role in nurse-patient relations: a qualitative study[J]. J Caring Sci. 2016;5(4):267–76.

McGilton KS, Sorin-Peters R, Sidani S, et al. Patient-centred communication intervention study to evaluate nurse-patient interactions in complex continuing care[J]. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:61.

Strauss B. The patient perception of the nurse-patient relationship when nurses utilize an electronic health record within a hospital setting[J]. Comput Inf Nurs. 2013;31(12):596–604.

Keykaleh MS, Safarpour H, Yousefian S, et al. The relationship between Nurse’s job stress and patient safety[J]. Open Access Macedonian J Med Sci. 2018;6(11):2228–32.

Teymourzadeh E, Rashidian A, Arab M, et al. Nurses exposure to workplace violence in a large teaching hospital in Iran[J]. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2014;3(6):301–5.

Kieft RA, de Brouwer BB, Francke AL, et al. How nurses and their work environment affect patient experiences of the quality of care: a qualitative study[J]. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:249.

The power in. the nurse-patient relationship: integrative review[J].

Allande-Cussó R, Macías-Seda J, Porcel-Gálvez AM. Transcultural adaptation into Spanish of the caring nurse-patient interactions for assessing nurse-patient relationship competence[J]. Enfermería Clínica (English Edition). 2020;30(1):42–6.

Maslach C, Leiter MP. The truth about burnout[M]. The Truth About Burnout; 1997.

Garcia CL, Abreu LC, Ramos J et al. Influence of burnout on patient safety: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Med (Kaunas). 2019;55(9).

Al-Awamreh K, Suliman M. Patients’ satisfaction with the quality of nursing care in thalassemia units[J]. Appl Nurs Res. 2019;47:46–51.

Gender differences in. sleeping hours and recovery experience among psychiatric nurses in Japan[J].

Zhou Xiaomei L. Investigation and analysis of clinical nurses’ nursing care behavior and patients’ caring perception [J]. Chin J Practical Nurs. 2019;35(36):2858–63.

Zhang, Wen. Cheng Xiangwei. A qualitative study on the practice perception of humanistic care in male nurses [J]. J Nurs Sci. 2017;32(08):63–6.

Benner PE. From novice to expert: excellence and power in clinical nursing practice[M]. From novice to expert: excellence and power in clinical nursing practice, 1984.

Suikkala A, Leino-Kilpi H. Nursing student-patient relationship: experiences of students and patients[J]. Nurse Educ Today. 2005;25(5):344–54.

Download references

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71673073 and 71974049) for providing funding.

Author information

Yajie Feng, Xinru Liu and Zhaoyue Liu are joint first authors.

Authors and Affiliations

School of Health Administration, Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China

Yajie Feng, Siyi Tao, Chen Wang, Huanyu Zhang, Xinru Liu, Zhaoyue Liu, Wei Liu, Juan Zhao, Dandan Zou, Zhixin Liu, Junping Liu, Nan Wang, Lin Wu, Qunhong Wu, Yanhua Hao & Libo Liang

Qiqihar Medical College, Qiqihar, China

Department of Public Health, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, 3086, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Chaojie Liu

Department of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, Peking University, 100191, Beijing, China

Southwest Hospital, Third Military Medical University (Army Medical University, 400000, Chongqing, China

Xinqiao Hospital, Third Military Medical University (Army Medical University, 400037, Chongqing, China

Jin Shan Hospital of Fudan University, 201508, Shanghai, China

Anhui Medical University, No.1166, Wangjiang West Road, Shushan District, Hefei, Anhui, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

F.Y.J. and T.S.Y. and W.C and L.W. and Z.H.Y and L.X.R and Z.J and Z.D.D and L.Z.X and L.J.P and W.N and W.L. and L.Z.Y. conceptualized the study. F.Y.J and L.X.R and T.S.Y and W.C. and L.L.B. contributed to reagents methodology. F.Y.J and T.S.Y and W.C and L.W and Z.H.Y and L.X.R and Z.J and Z.D.D. L.Z.X. and L.J.P. supervised data collection. F.Y.J and L.L.B and W.Q.H. and X.W.L. directed data analysis. F.Y.J and L.L.B and L.C.J and H.Y.H. and X.W.L. interpreted the findings. F.Y.J. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Yanhua Hao , Weilan Xu or Libo Liang .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board at the Harbin Medical University. The data collection occurred between October and December 2019. Abiding by the research ethical conduct, informed consent was obtained from all subjects who participated in this study. Research is carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Feng, Y., Liu, C., Tao, S. et al. Developing and validating the nurse-patient relationship scale (NPRS) in China. BMC Nurs 23 , 255 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01941-w

Download citation

Received : 27 July 2023

Accepted : 15 April 2024

Published : 22 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01941-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Nurse-patient relationship

- Reliability

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 17, Issue 4

- Bias in research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Joanna Smith 1 ,

- Helen Noble 2

- 1 School of Human and Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield , Huddersfield , UK

- 2 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- Correspondence to : Dr Joanna Smith , School of Human and Health Sciences, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield HD1 3DH, UK; j.e.smith{at}hud.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2014-101946

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

The aim of this article is to outline types of ‘bias’ across research designs, and consider strategies to minimise bias. Evidence-based nursing, defined as the “process by which evidence, nursing theory, and clinical expertise are critically evaluated and considered, in conjunction with patient involvement, to provide the delivery of optimum nursing care,” 1 is central to the continued development of the nursing professional. Implementing evidence into practice requires nurses to critically evaluate research, in particular assessing the rigour in which methods were undertaken and factors that may have biased findings.

What is bias in relation to research and why is understanding bias important?

Although different study designs have specific methodological challenges and constraints, bias can occur at each stage of the research process ( table 1 ). In quantitative research, the validity and reliability are assessed using statistical tests that estimate the size of error in samples and calculating the significance of findings (typically p values or CIs). The tests and measures used to establish the validity and reliability of quantitative research cannot be applied to qualitative research. However, in the broadest context, these terms are applicable, with validity referring to the integrity and application of the methods and the precision in which the findings accurately reflect the data, and reliability referring to the consistency within the analytical processes. 4

- View inline

Types of research bias

How is bias minimised when undertaken research?

Bias exists in all study designs, and although researchers should attempt to minimise bias, outlining potential sources of bias enables greater critical evaluation of the research findings and conclusions. Researchers bring to each study their experiences, ideas, prejudices and personal philosophies, which if accounted for in advance of the study, enhance the transparency of possible research bias. Clearly articulating the rationale for and choosing an appropriate research design to meet the study aims can reduce common pitfalls in relation to bias. Ethics committees have an important role in considering whether the research design and methodological approaches are biased, and suitable to address the problem being explored. Feedback from peers, funding bodies and ethics committees is an essential part of designing research studies, and often provides valuable practical guidance in developing robust research.

In quantitative studies, selection bias is often reduced by the random selection of participants, and in the case of clinical trials randomisation of participants into comparison groups. However, not accounting for participants who withdraw from the study or are lost to follow-up can result in sample bias or change the characteristics of participants in comparison groups. 7 In qualitative research, purposeful sampling has advantages when compared with convenience sampling in that bias is reduced because the sample is constantly refined to meet the study aims. Premature closure of the selection of participants before analysis is complete can threaten the validity of a qualitative study. This can be overcome by continuing to recruit new participants into the study during data analysis until no new information emerges, known as data saturation. 8

In quantitative studies having a well-designed research protocol explicitly outlining data collection and analysis can assist in reducing bias. Feasibility studies are often undertaken to refine protocols and procedures. Bias can be reduced by maximising follow-up and where appropriate in randomised control trials analysis should be based on the intention-to-treat principle, a strategy that assesses clinical effectiveness because not everyone complies with treatment and the treatment people receive may be changed according to how they respond. Qualitative research has been criticised for lacking transparency in relation to the analytical processes employed. 4 Qualitative researchers must demonstrate rigour, associated with openness, relevance to practice and congruence of the methodological approach. Although other researchers may interpret the data differently, appreciating and understanding how the themes were developed is an essential part of demonstrating the robustness of the findings. Reducing bias can include respondent validation, constant comparisons across participant accounts, representing deviant cases and outliers, prolonged involvement or persistent observation of participants, independent analysis of the data by other researchers and triangulation. 4

In summary, minimising bias is a key consideration when designing and undertaking research. Researchers have an ethical duty to outline the limitations of studies and account for potential sources of bias. This will enable health professionals and policymakers to evaluate and scrutinise study findings, and consider these when applying findings to practice or policy.

- Wakefield AJ ,

- Anthony A ,

- ↵ The Lancet . Retraction—ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children . Lancet 2010 ; 375 : 445 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- Easterbrook PJ ,

- Berlin JA ,

- Gopalan R ,

- Petticrew M ,

- Thomson H ,

- Francis J ,

- Johnston M ,

- Robertson C ,

Competing interests None.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2024

Relationship between learning styles and clinical competency in nursing students

- Seyed Kazem Mousavi 1 , 2 ,

- Ali Javadzadeh 3 ,

- Hanieh Hasankhani 3 &

- Zahra Alijani Parizad 3

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 469 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

265 Accesses

Metrics details

The acquisition of clinical competence is considered the ultimate goal of nursing education programs. This study explored the relationship between learning styles and clinical competency in undergraduate nursing students.

A descriptive-correlational study was conducted in 2023 with 276 nursing students from the second to sixth semesters at Abhar School of Nursing, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Data were collected using demographic questionnaires, Kolb’s learning styles, and Meretoja’s clinical competence assessments completed online by participants. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16, employing descriptive statistics and inferential tests (independent T-test, ANOVA, Pearson correlation) at a significance level 0.05.

The predominant learning styles among nursing students were divergent (31.2%), and the least common was convergent (18.4%). The overall clinical competency score was 77.25 ± 12.65. Also, there was a significant relationship between learning styles and clinical competency, so the clinical competency of students with accommodative and converging learning styles was higher. ( P < 0.05).

The results of this study showed the association between learning styles and clinical competence in nursing students. It is recommended that educational programs identify talented students and provide workshops tailored to strengthen various learning styles associated with enhanced clinical competence.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Clinical competency is a multifaceted and nuanced concept that has been extensively explored and examined from various perspectives in recent years [ 1 ]. Its significance is underscored by the World Health Organization (WHO), which has identified the assessment and enhancement of nurses’ competencies as fundamental principles to uphold the quality of care. WHO defines nurses as competent when they can fulfill their professional responsibilities at the appropriate level, grade, and standard [ 2 ]. Factors such as evolving healthcare systems, the imperative for safe and cost-effective services, heightened community awareness of health issues, escalating expectations for quality care, and the demand for skilled healthcare professionals have elevated the importance of clinical competence in nursing and related fields [ 3 ]. Clinical competency is considered the ultimate objective and benchmark of nursing education effectiveness [ 4 ]. Notably, clinical education constitutes a pivotal component of nursing training, with over half of nursing programs dedicated to practical training [ 5 ]. A nursing student’s ability to become a proficient nurse at the bedside hinges on acquiring essential skills during their academic journey and attaining requisite qualifications [ 6 ]. Scholars argue that continual efforts to enhance educational quality are essential for upholding nursing care standards and improving clinical competence [ 7 , 8 ]. Understanding how learners acquire knowledge is crucial for enhancing educational quality, with learning styles playing a pivotal role in this process [ 9 ].

Learning refers to the relatively enduring behavioral changes from experiences [ 10 ]. Learning styles, a concept widely embraced by educational theorists in recent decades, pertain to individuals’ distinct approaches to processing information and acquiring knowledge [ 11 ]. These styles encompass cognitive and psychosocial traits that are relatively stable indicators of learners’ engagement with and response to their learning environments [ 12 ]. Among the myriad theories on learning styles, Kolb’s learning theory is particularly influential [ 13 ]. According to Kolb, learning can be categorized into four primary modes: concrete experience, abstract conceptualization, reflective observation, and active experimentation, yielding four learning styles—converging, diverging, assimilating, and accommodating [ 14 ].

People with a converging learning style excel at problem-solving, decision-making, and practical application by engaging in abstract conceptualization and active experimentation [ 15 ]. Diverging learners thrive on experiencing and closely observing situations, possessing a unique ability to view scenarios from multiple perspectives and synthesize information into a cohesive whole [ 16 ]. The assimilating learning style is characterized by a preference for deep thinking and thorough examination, with individual’s adept at organizing information and employing abstract concepts to comprehend complex situations [ 13 ]. Accommodating learners learn best through hands-on experiences and activities, demonstrating proficiency in working with tangible objects and gaining new insights through practical engagement [ 10 ]. Learning styles are essential in nursing education because the primary mission of nursing education programs is to train nurses who have the necessary knowledge, attitude, and skills to maintain and improve the health of society members, and in other words, have sufficient competence in providing their job duties [ 17 ].

So far, separate studies have been conducted on nursing students’ learning styles and clinical competency [ 4 , 8 , 13 , 17 ]. However, the relationship between these two concepts has received less attention from researchers. The first step in ensuring students’ academic success is to determine their learning style [ 11 ]. Professors’ awareness of the student’s learning styles and the relationship between these styles and the level of clinical competency provide a favorable opportunity to identify the styles with higher clinical competency and encourage students to use them as much as possible. Considering this importance, the researchers decided to design and implement the present study to investigate the relationship between learning styles and clinical competency in nursing students.

Materials and methods

Study design and sampling.

This study was a descriptive-correlational study conducted in 2023, investigating the relationship between learning styles and the clinical competency of undergraduate nursing students. The research involved all second to sixth-semester undergraduate nursing students from the Abhar School of Nursing affiliated with Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Sampling was carried out as a census, with 276 students selected to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the study, full-time employment in nursing, no prior clinical work experience, and no reported psychiatric diseases or medication use. Incomplete questionnaire completion was set as an exclusion criterion.

Instruments

The data collection tools included demographic questionnaires, Kolb’s learning styles questionnaire, and a modified Meretoja nursing clinical competency questionnaire. The demographic questionnaire gathered age, gender, marital status, semester, Grade Point Average (GPA), and interest in nursing.

The data collection tools included demographic questionnaires, Kolb’s learning styles questionnaire, and a modified Meretoja nursing clinical competency questionnaire. The demographic questionnaire gathered information such as age, gender, marital status, semester, Grade Point Average (GPA), and interest in nursing.

Kolb’s III learning styles questionnaire comprised 12 questions with four options each, requiring the student to select the option most similar to them. Each option represented one of the four main learning methods: concrete experience (CE), reflective observation (RO), abstract conceptualization (AC), and active experimentation (AE). Scores for the four learning styles were obtained from the total questions across the sections. By subtracting scores, two dimensions (AC - CE) and (AE - RO) were derived, determining the student’s learning styles as converging, diverging, accommodating, or assimilating [ 18 ]. This questionnaire has been used in various studies over the past 30 years, demonstrating validity and reliability. In Iran, Ghahrani et al. used the internal consistency method to determine the reliability of the questionnaire. They obtained Cronbach’s alpha of 71% in concrete experience, 68% in reflective observation, 71% in abstract conceptualization, and 71% in active experimentation [ 19 ]. Also, In the present study, the reliability value of this questionnaire was determined using Cronbach’s alpha method of 0.94.

Meretoja’s revised nursing clinical competency questionnaire contained 47 items across 5 areas of clinical competency: assisting patients (7 skills), teaching and guidance (12 skills), diagnostic measures (8 skills), therapeutic measures (5 skills), and occupational responsibilities (15 skills). Skills were rated on a four-point Likert scale, assessing the degree of skill utilization [ 20 ]. This questionnaire was psychometrically evaluated in Iran by Bahreini et al., and its validity was qualitatively determined at the optimal level, and its reliability was determined between 70 and 85%. Also, in this study, the reliability value of this questionnaire was determined using Cronbach’s alpha method of 0.91 [ 21 ].

Data collection and statistical analysis

Following ethical approval and research permission, questionnaires, consent forms, and contact information for the researchers were provided to students online through the Porsline system ( www.porsline.ir ) for completion. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 16 software, employing descriptive (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential (independent T-test, ANOVA, Pearson correlation) statistics at a significance level of 0.05.

Out of 276 participants, 10 students were excluded due to incomplete questionnaire responses, leaving 266 participants for analysis. The average age of students was 22.33, with 63.4% being female. Most participants were single (79.2%), and 46.2% had a GPA between 16 and 18. Also, 80.7% of students declared that they are interested in nursing. Then, the results of the questionnaires on learning styles and clinical competency were examined. Based on this, the findings showed that divergent (31.2%) and convergent (18.4%) styles were the study participants’ most and least-used learning styles, respectively. Also, the overall students’ clinical competence score was 77.25 ± 12.65 (Table 1 ).

The relationship between the participants’ learning styles and clinical competency was examined in the next step. Initially, the study data underwent a normality assessment. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results indicated that parametric statistical tests were applicable ( p > 0.05). Subsequently, an ANOVA test was conducted to explore the relationship between learning styles and clinical competency, revealing a significant association between learning style and clinical competency with moderate effect size ( p < 0.05) (Table 2 ).

The correlation between demographic variables, learning styles, and student clinical competency was investigated in the final phase of analyzing the findings. Parametric independent t-tests, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and ANOVA were employed for this analysis. The results indicated that none of the learning styles exhibited a statistically significant relationship with the demographic characteristics of the participants ( p > 0.05). However, a significant correlation was observed between participants’ demographic variables, such as age, academic semester, GPA, and interest in nursing, and their clinical competencies ( p < 0.05) (Table 3 ).

This study explored the relationship between learning styles and clinical competency in undergraduate nursing students. The research initially focused on examining the variables and subsequently explored their interrelation. According to this, the most prevalent learning style among nursing students was divergent. This finding aligns with the outcomes of various domestic studies like Mehni et al. [ 22 ] and Shirazi et al. [ 16 ], as well as numerous international studies such as those by Campos et al. in Brazil and the United States [ 23 ], Nosheen in Pakistan [ 24 ], Madu et al. in Nigeria [ 25 ], and AbuAssi et al. in Saudi Arabia [ 26 ]. It should be said that the dominant abilities of people with divergent styles are concrete experience and reflective observation. They see the situation from multiple angles, emphasize brainstorming and generating ideas, have a strong imagination, are more sensitive to values, respect the feelings of others, and listen with an open mind and without bias [ 5 ]. Therefore, these people have high cultural interests and are more inclined towards humanities fields such as sociology, psychology, counseling, and nursing.

Upon reviewing studies in this field, it is concluded that findings often vary. They can be influenced by factors including individual student traits, educators’ teaching styles, learning environments, and tasks [ 12 ]. Also, this study noted no significant association between learning styles and participants’ demographic characteristics, consistent with similar research in the field [ 22 , 23 ]. In this regard, Dantas et al. emphasized that learning styles predominantly reflect individuals’ traits and are minimally impacted by demographic variables [ 12 ].