- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Research Summary

It’s a common perception that writing a research summary is a quick and easy task. After all, how hard can jotting down 300 words be? But when you consider the weight those 300 words carry, writing a research summary as a part of your dissertation, essay or compelling draft for your paper instantly becomes daunting task.

A research summary requires you to synthesize a complex research paper into an informative, self-explanatory snapshot. It needs to portray what your article contains. Thus, writing it often comes at the end of the task list.

Regardless of when you’re planning to write, it is no less of a challenge, particularly if you’re doing it for the first time. This blog will take you through everything you need to know about research summary so that you have an easier time with it.

What is a Research Summary?

A research summary is the part of your research paper that describes its findings to the audience in a brief yet concise manner. A well-curated research summary represents you and your knowledge about the information written in the research paper.

While writing a quality research summary, you need to discover and identify the significant points in the research and condense it in a more straightforward form. A research summary is like a doorway that provides access to the structure of a research paper's sections.

Since the purpose of a summary is to give an overview of the topic, methodology, and conclusions employed in a paper, it requires an objective approach. No analysis or criticism.

Research summary or Abstract. What’s the Difference?

They’re both brief, concise, and give an overview of an aspect of the research paper. So, it’s easy to understand why many new researchers get the two confused. However, a research summary and abstract are two very different things with individual purpose. To start with, a research summary is written at the end while the abstract comes at the beginning of a research paper.

A research summary captures the essence of the paper at the end of your document. It focuses on your topic, methods, and findings. More like a TL;DR, if you will. An abstract, on the other hand, is a description of what your research paper is about. It tells your reader what your topic or hypothesis is, and sets a context around why you have embarked on your research.

Getting Started with a Research Summary

Before you start writing, you need to get insights into your research’s content, style, and organization. There are three fundamental areas of a research summary that you should focus on.

- While deciding the contents of your research summary, you must include a section on its importance as a whole, the techniques, and the tools that were used to formulate the conclusion. Additionally, there needs to be a short but thorough explanation of how the findings of the research paper have a significance.

- To keep the summary well-organized, try to cover the various sections of the research paper in separate paragraphs. Besides, how the idea of particular factual research came up first must be explained in a separate paragraph.

- As a general practice worldwide, research summaries are restricted to 300-400 words. However, if you have chosen a lengthy research paper, try not to exceed the word limit of 10% of the entire research paper.

How to Structure Your Research Summary

The research summary is nothing but a concise form of the entire research paper. Therefore, the structure of a summary stays the same as the paper. So, include all the section titles and write a little about them. The structural elements that a research summary must consist of are:

It represents the topic of the research. Try to phrase it so that it includes the key findings or conclusion of the task.

The abstract gives a context of the research paper. Unlike the abstract at the beginning of a paper, the abstract here, should be very short since you’ll be working with a limited word count.

Introduction

This is the most crucial section of a research summary as it helps readers get familiarized with the topic. You should include the definition of your topic, the current state of the investigation, and practical relevance in this part. Additionally, you should present the problem statement, investigative measures, and any hypothesis in this section.

Methodology

This section provides details about the methodology and the methods adopted to conduct the study. You should write a brief description of the surveys, sampling, type of experiments, statistical analysis, and the rationality behind choosing those particular methods.

Create a list of evidence obtained from the various experiments with a primary analysis, conclusions, and interpretations made upon that. In the paper research paper, you will find the results section as the most detailed and lengthy part. Therefore, you must pick up the key elements and wisely decide which elements are worth including and which are worth skipping.

This is where you present the interpretation of results in the context of their application. Discussion usually covers results, inferences, and theoretical models explaining the obtained values, key strengths, and limitations. All of these are vital elements that you must include in the summary.

Most research papers merge conclusion with discussions. However, depending upon the instructions, you may have to prepare this as a separate section in your research summary. Usually, conclusion revisits the hypothesis and provides the details about the validation or denial about the arguments made in the research paper, based upon how convincing the results were obtained.

The structure of a research summary closely resembles the anatomy of a scholarly article . Additionally, you should keep your research and references limited to authentic and scholarly sources only.

Tips for Writing a Research Summary

The core concept behind undertaking a research summary is to present a simple and clear understanding of your research paper to the reader. The biggest hurdle while doing that is the number of words you have at your disposal. So, follow the steps below to write a research summary that sticks.

1. Read the parent paper thoroughly

You should go through the research paper thoroughly multiple times to ensure that you have a complete understanding of its contents. A 3-stage reading process helps.

a. Scan: In the first read, go through it to get an understanding of its basic concept and methodologies.

b. Read: For the second step, read the article attentively by going through each section, highlighting the key elements, and subsequently listing the topics that you will include in your research summary.

c. Skim: Flip through the article a few more times to study the interpretation of various experimental results, statistical analysis, and application in different contexts.

Sincerely go through different headings and subheadings as it will allow you to understand the underlying concept of each section. You can try reading the introduction and conclusion simultaneously to understand the motive of the task and how obtained results stay fit to the expected outcome.

2. Identify the key elements in different sections

While exploring different sections of an article, you can try finding answers to simple what, why, and how. Below are a few pointers to give you an idea:

- What is the research question and how is it addressed?

- Is there a hypothesis in the introductory part?

- What type of methods are being adopted?

- What is the sample size for data collection and how is it being analyzed?

- What are the most vital findings?

- Do the results support the hypothesis?

Discussion/Conclusion

- What is the final solution to the problem statement?

- What is the explanation for the obtained results?

- What is the drawn inference?

- What are the various limitations of the study?

3. Prepare the first draft

Now that you’ve listed the key points that the paper tries to demonstrate, you can start writing the summary following the standard structure of a research summary. Just make sure you’re not writing statements from the parent research paper verbatim.

Instead, try writing down each section in your own words. This will not only help in avoiding plagiarism but will also show your complete understanding of the subject. Alternatively, you can use a summarizing tool (AI-based summary generators) to shorten the content or summarize the content without disrupting the actual meaning of the article.

SciSpace Copilot is one such helpful feature! You can easily upload your research paper and ask Copilot to summarize it. You will get an AI-generated, condensed research summary. SciSpace Copilot also enables you to highlight text, clip math and tables, and ask any question relevant to the research paper; it will give you instant answers with deeper context of the article..

4. Include visuals

One of the best ways to summarize and consolidate a research paper is to provide visuals like graphs, charts, pie diagrams, etc.. Visuals make getting across the facts, the past trends, and the probabilistic figures around a concept much more engaging.

5. Double check for plagiarism

It can be very tempting to copy-paste a few statements or the entire paragraphs depending upon the clarity of those sections. But it’s best to stay away from the practice. Even paraphrasing should be done with utmost care and attention.

Also: QuillBot vs SciSpace: Choose the best AI-paraphrasing tool

6. Religiously follow the word count limit

You need to have strict control while writing different sections of a research summary. In many cases, it has been observed that the research summary and the parent research paper become the same length. If that happens, it can lead to discrediting of your efforts and research summary itself. Whatever the standard word limit has been imposed, you must observe that carefully.

7. Proofread your research summary multiple times

The process of writing the research summary can be exhausting and tiring. However, you shouldn’t allow this to become a reason to skip checking your academic writing several times for mistakes like misspellings, grammar, wordiness, and formatting issues. Proofread and edit until you think your research summary can stand out from the others, provided it is drafted perfectly on both technicality and comprehension parameters. You can also seek assistance from editing and proofreading services , and other free tools that help you keep these annoying grammatical errors at bay.

8. Watch while you write

Keep a keen observation of your writing style. You should use the words very precisely, and in any situation, it should not represent your personal opinions on the topic. You should write the entire research summary in utmost impersonal, precise, factually correct, and evidence-based writing.

9. Ask a friend/colleague to help

Once you are done with the final copy of your research summary, you must ask a friend or colleague to read it. You must test whether your friend or colleague could grasp everything without referring to the parent paper. This will help you in ensuring the clarity of the article.

Once you become familiar with the research paper summary concept and understand how to apply the tips discussed above in your current task, summarizing a research summary won’t be that challenging. While traversing the different stages of your academic career, you will face different scenarios where you may have to create several research summaries.

In such cases, you just need to look for answers to simple questions like “Why this study is necessary,” “what were the methods,” “who were the participants,” “what conclusions were drawn from the research,” and “how it is relevant to the wider world.” Once you find out the answers to these questions, you can easily create a good research summary following the standard structure and a precise writing style.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal?

What is the purpose of a research proposal , how long should a research proposal be, what should be included in a research proposal, 1. the title page, 2. introduction, 3. literature review, 4. research design, 5. implications, 6. reference list, frequently asked questions about writing a research proposal, related articles.

If you’re in higher education, the term “research proposal” is something you’re likely to be familiar with. But what is it, exactly? You’ll normally come across the need to prepare a research proposal when you’re looking to secure Ph.D. funding.

When you’re trying to find someone to fund your Ph.D. research, a research proposal is essentially your “pitch.”

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research.

You’ll need to set out the issues that are central to the topic area and how you intend to address them with your research. To do this, you’ll need to give the following:

- an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls

- an overview of how much is currently known about the topic

- a literature review that covers the recent scholarly debate or conversation around the topic

➡️ What is a literature review? Learn more in our guide.

Essentially, you are trying to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into.

It is the opportunity for you to demonstrate that you have the aptitude for this level of research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas:

It also helps you to find the right supervisor to oversee your research. When you’re writing your research proposal, you should always have this in the back of your mind.

This is the document that potential supervisors will use in determining the legitimacy of your research and, consequently, whether they will invest in you or not. It is therefore incredibly important that you spend some time on getting it right.

Tip: While there may not always be length requirements for research proposals, you should strive to cover everything you need to in a concise way.

If your research proposal is for a bachelor’s or master’s degree, it may only be a few pages long. For a Ph.D., a proposal could be a pretty long document that spans a few dozen pages.

➡️ Research proposals are similar to grant proposals. Learn how to write a grant proposal in our guide.

When you’re writing your proposal, keep in mind its purpose and why you’re writing it. It, therefore, needs to clearly explain the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. You need to then explain what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

Generally, your structure should look something like this:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Research Design

- Implications

If you follow this structure, you’ll have a comprehensive and coherent proposal that looks and feels professional, without missing out on anything important. We’ll take a deep dive into each of these areas one by one next.

The title page might vary slightly per your area of study but, as a general point, your title page should contain the following:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- The name of your institution and your particular department

Tip: Keep in mind any departmental or institutional guidelines for a research proposal title page. Also, your supervisor may ask for specific details to be added to the page.

The introduction is crucial to your research proposal as it is your first opportunity to hook the reader in. A good introduction section will introduce your project and its relevance to the field of study.

You’ll want to use this space to demonstrate that you have carefully thought about how to present your project as interesting, original, and important research. A good place to start is by introducing the context of your research problem.

Think about answering these questions:

- What is it you want to research and why?

- How does this research relate to the respective field?

- How much is already known about this area?

- Who might find this research interesting?

- What are the key questions you aim to answer with your research?

- What will the findings of this project add to the topic area?

Your introduction aims to set yourself off on a great footing and illustrate to the reader that you are an expert in your field and that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge and theory.

The literature review section answers the question who else is talking about your proposed research topic.

You want to demonstrate that your research will contribute to conversations around the topic and that it will sit happily amongst experts in the field.

➡️ Read more about how to write a literature review .

There are lots of ways you can find relevant information for your literature review, including:

- Research relevant academic sources such as books and journals to find similar conversations around the topic.

- Read through abstracts and bibliographies of your academic sources to look for relevance and further additional resources without delving too deep into articles that are possibly not relevant to you.

- Watch out for heavily-cited works . This should help you to identify authoritative work that you need to read and document.

- Look for any research gaps , trends and patterns, common themes, debates, and contradictions.

- Consider any seminal studies on the topic area as it is likely anticipated that you will address these in your research proposal.

This is where you get down to the real meat of your research proposal. It should be a discussion about the overall approach you plan on taking, and the practical steps you’ll follow in answering the research questions you’ve posed.

So what should you discuss here? Some of the key things you will need to discuss at this point are:

- What form will your research take? Is it qualitative/quantitative/mixed? Will your research be primary or secondary?

- What sources will you use? Who or what will you be studying as part of your research.

- Document your research method. How are you practically going to carry out your research? What tools will you need? What procedures will you use?

- Any practicality issues you foresee. Do you think there will be any obstacles to your anticipated timescale? What resources will you require in carrying out your research?

Your research design should also discuss the potential implications of your research. For example, are you looking to confirm an existing theory or develop a new one?

If you intend to create a basis for further research, you should describe this here.

It is important to explain fully what you want the outcome of your research to look like and what you want to achieve by it. This will help those reading your research proposal to decide if it’s something the field needs and wants, and ultimately whether they will support you with it.

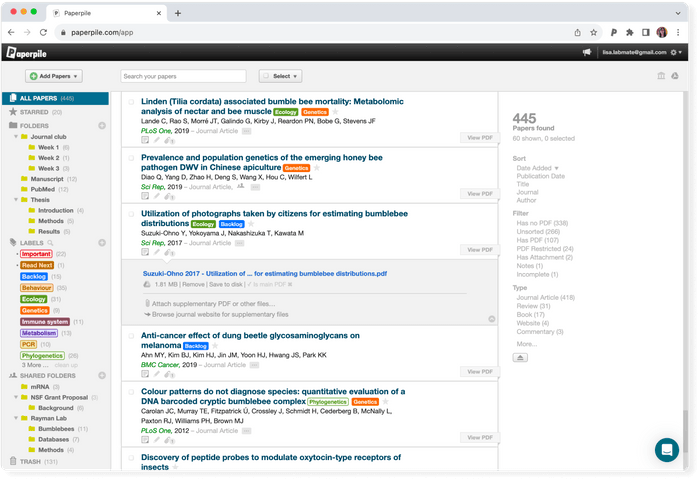

When you reach the end of your research proposal, you’ll have to compile a list of references for everything you’ve cited above. Ideally, you should keep track of everything from the beginning. Otherwise, this could be a mammoth and pretty laborious task to do.

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to format and organize your citations. Paperpile allows you to organize and save your citations for later use and cite them in thousands of citation styles directly in Google Docs, Microsoft Word, or LaTeX.

Your project may also require you to have a timeline, depending on the budget you are requesting. If you need one, you should include it here and explain both the timeline and the budget you need, documenting what should be done at each stage of the research and how much of the budget this will use.

This is the final step, but not one to be missed. You should make sure that you edit and proofread your document so that you can be sure there are no mistakes.

A good idea is to have another person proofread the document for you so that you get a fresh pair of eyes on it. You can even have a professional proofreader do this for you.

This is an important document and you don’t want spelling or grammatical mistakes to get in the way of you and your reader.

➡️ Working on a research proposal for a thesis? Take a look at our guide on how to come up with a topic for your thesis .

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research. Generally, your research proposal will have a title page, introduction, literature review section, a section about research design and explaining the implications of your research, and a reference list.

A good research proposal is concise and coherent. It has a clear purpose, clearly explains the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. A good research proposal explains what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

You need a research proposal to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into. It is your opportunity to demonstrate your aptitude for this level or research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas clearly, concisely, and critically.

A research proposal is essentially your "pitch" when you're trying to find someone to fund your PhD. It is a clear and concise summary of your proposed research. It gives an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls, it elaborates how much is currently known about the topic, and it highlights any recent debate or conversation around the topic by other academics.

The general answer is: as long as it needs to be to cover everything. The length of your research proposal depends on the requirements from the institution that you are applying to. Make sure to carefully read all the instructions given, and if this specific information is not provided, you can always ask.

- Research Process

Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

- 5 minute read

- 99.2K views

Table of Contents

The importance of a well-written research proposal cannot be underestimated. Your research really is only as good as your proposal. A poorly written, or poorly conceived research proposal will doom even an otherwise worthy project. On the other hand, a well-written, high-quality proposal will increase your chances for success.

In this article, we’ll outline the basics of writing an effective scientific research proposal, including the differences between research proposals, grants and cover letters. We’ll also touch on common mistakes made when submitting research proposals, as well as a simple example or template that you can follow.

What is a scientific research proposal?

The main purpose of a scientific research proposal is to convince your audience that your project is worthwhile, and that you have the expertise and wherewithal to complete it. The elements of an effective research proposal mirror those of the research process itself, which we’ll outline below. Essentially, the research proposal should include enough information for the reader to determine if your proposed study is worth pursuing.

It is not an uncommon misunderstanding to think that a research proposal and a cover letter are the same things. However, they are different. The main difference between a research proposal vs cover letter content is distinct. Whereas the research proposal summarizes the proposal for future research, the cover letter connects you to the research, and how you are the right person to complete the proposed research.

There is also sometimes confusion around a research proposal vs grant application. Whereas a research proposal is a statement of intent, related to answering a research question, a grant application is a specific request for funding to complete the research proposed. Of course, there are elements of overlap between the two documents; it’s the purpose of the document that defines one or the other.

Scientific Research Proposal Format

Although there is no one way to write a scientific research proposal, there are specific guidelines. A lot depends on which journal you’re submitting your research proposal to, so you may need to follow their scientific research proposal template.

In general, however, there are fairly universal sections to every scientific research proposal. These include:

- Title: Make sure the title of your proposal is descriptive and concise. Make it catch and informative at the same time, avoiding dry phrases like, “An investigation…” Your title should pique the interest of the reader.

- Abstract: This is a brief (300-500 words) summary that includes the research question, your rationale for the study, and any applicable hypothesis. You should also include a brief description of your methodology, including procedures, samples, instruments, etc.

- Introduction: The opening paragraph of your research proposal is, perhaps, the most important. Here you want to introduce the research problem in a creative way, and demonstrate your understanding of the need for the research. You want the reader to think that your proposed research is current, important and relevant.

- Background: Include a brief history of the topic and link it to a contemporary context to show its relevance for today. Identify key researchers and institutions also looking at the problem

- Literature Review: This is the section that may take the longest amount of time to assemble. Here you want to synthesize prior research, and place your proposed research into the larger picture of what’s been studied in the past. You want to show your reader that your work is original, and adds to the current knowledge.

- Research Design and Methodology: This section should be very clearly and logically written and organized. You are letting your reader know that you know what you are going to do, and how. The reader should feel confident that you have the skills and knowledge needed to get the project done.

- Preliminary Implications: Here you’ll be outlining how you anticipate your research will extend current knowledge in your field. You might also want to discuss how your findings will impact future research needs.

- Conclusion: This section reinforces the significance and importance of your proposed research, and summarizes the entire proposal.

- References/Citations: Of course, you need to include a full and accurate list of any and all sources you used to write your research proposal.

Common Mistakes in Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

Remember, the best research proposal can be rejected if it’s not well written or is ill-conceived. The most common mistakes made include:

- Not providing the proper context for your research question or the problem

- Failing to reference landmark/key studies

- Losing focus of the research question or problem

- Not accurately presenting contributions by other researchers and institutions

- Incompletely developing a persuasive argument for the research that is being proposed

- Misplaced attention on minor points and/or not enough detail on major issues

- Sloppy, low-quality writing without effective logic and flow

- Incorrect or lapses in references and citations, and/or references not in proper format

- The proposal is too long – or too short

Scientific Research Proposal Example

There are countless examples that you can find for successful research proposals. In addition, you can also find examples of unsuccessful research proposals. Search for successful research proposals in your field, and even for your target journal, to get a good idea on what specifically your audience may be looking for.

While there’s no one example that will show you everything you need to know, looking at a few will give you a good idea of what you need to include in your own research proposal. Talk, also, to colleagues in your field, especially if you are a student or a new researcher. We can often learn from the mistakes of others. The more prepared and knowledgeable you are prior to writing your research proposal, the more likely you are to succeed.

Language Editing Services

One of the top reasons scientific research proposals are rejected is due to poor logic and flow. Check out our Language Editing Services to ensure a great proposal , that’s clear and concise, and properly referenced. Check our video for more information, and get started today.

- Manuscript Review

Research Fraud: Falsification and Fabrication in Research Data

Research Team Structure

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Research Proposal Example/Sample

Detailed Walkthrough + Free Proposal Template

If you’re getting started crafting your research proposal and are looking for a few examples of research proposals , you’ve come to the right place.

In this video, we walk you through two successful (approved) research proposals , one for a Master’s-level project, and one for a PhD-level dissertation. We also start off by unpacking our free research proposal template and discussing the four core sections of a research proposal, so that you have a clear understanding of the basics before diving into the actual proposals.

- Research proposal example/sample – Master’s-level (PDF/Word)

- Research proposal example/sample – PhD-level (PDF/Word)

- Proposal template (Fully editable)

If you’re working on a research proposal for a dissertation or thesis, you may also find the following useful:

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : Learn how to write a research proposal as efficiently and effectively as possible

- 1:1 Proposal Coaching : Get hands-on help with your research proposal

FAQ: Research Proposal Example

Research proposal example: frequently asked questions, are the sample proposals real.

Yes. The proposals are real and were approved by the respective universities.

Can I copy one of these proposals for my own research?

As we discuss in the video, every research proposal will be slightly different, depending on the university’s unique requirements, as well as the nature of the research itself. Therefore, you’ll need to tailor your research proposal to suit your specific context.

You can learn more about the basics of writing a research proposal here .

How do I get the research proposal template?

You can access our free proposal template here .

Is the proposal template really free?

Yes. There is no cost for the proposal template and you are free to use it as a foundation for your research proposal.

Where can I learn more about proposal writing?

For self-directed learners, our Research Proposal Bootcamp is a great starting point.

For students that want hands-on guidance, our private coaching service is recommended.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a PhD in Management at Altantic International University. I checked on the coaching services, but it indicates that it’s not available in my area. I am in South Sudan. My proposed topic is: “Leadership Behavior in Local Government Governance Ecosystem and Service Delivery Effectiveness in Post Conflict Districts of Northern Uganda”. I will appreciate your guidance and support

GRADCOCH is very grateful motivated and helpful for all students etc. it is very accorporated and provide easy access way strongly agree from GRADCOCH.

Proposal research departemet management

I am at the stage of writing my thesis proposal for a masters in Analysis of w heat commercialisation by small holders householdrs at Hawassa International University. I will appreciate your guidance and support

please provide a attractive proposal about foreign universities .It would be your highness.

comparative constitutional law

Kindly guide me through writing a good proposal on the thesis topic; Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Financial Inclusion in Nigeria. Thank you

Kindly help me write a research proposal on the topic of impacts of artisanal gold panning on the environment

I am in the process of research proposal for my Master of Art with a topic : “factors influence on first-year students’s academic adjustment”. I am absorbing in GRADCOACH and interested in such proposal sample. However, it is great for me to learn and seeking for more new updated proposal framework from GRADCAOCH.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Executive Summary

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An executive summary is a thorough overview of a research report or other type of document that synthesizes key points for its readers, saving them time and preparing them to understand the study's overall content. It is a separate, stand-alone document of sufficient detail and clarity to ensure that the reader can completely understand the contents of the main research study. An executive summary can be anywhere from 1-10 pages long depending on the length of the report, or it can be the summary of more than one document [e.g., papers submitted for a group project].

Bailey, Edward, P. The Plain English Approach to Business Writing . (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 73-80 Todorovic, Zelimir William and Marietta Wolczacka Frye. “Writing Effective Executive Summaries: An Interdisciplinary Examination.” In United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship. Conference Proceedings . (Decatur, IL: United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 2009): pp. 662-691.

Importance of a Good Executive Summary

Although an executive summary is similar to an abstract in that they both summarize the contents of a research study, there are several key differences. With research abstracts, the author's recommendations are rarely included, or if they are, they are implicit rather than explicit. Recommendations are generally not stated in academic abstracts because scholars operate in a discursive environment, where debates, discussions, and dialogs are meant to precede the implementation of any new research findings. The conceptual nature of much academic writing also means that recommendations arising from the findings are distributed widely and not easily or usefully encapsulated. Executive summaries are used mainly when a research study has been developed for an organizational partner, funding entity, or other external group that participated in the research . In such cases, the research report and executive summary are often written for policy makers outside of academe, while abstracts are written for the academic community. Professors, therefore, assign the writing of executive summaries so students can practice synthesizing and writing about the contents of comprehensive research studies for external stakeholder groups.

When preparing to write, keep in mind that:

- An executive summary is not an abstract.

- An executive summary is not an introduction.

- An executive summary is not a preface.

- An executive summary is not a random collection of highlights.

Christensen, Jay. Executive Summaries Complete The Report. California State University Northridge; Clayton, John. "Writing an Executive Summary that Means Business." Harvard Management Communication Letter (July 2003): 2-4; Keller, Chuck. "Stay Healthy with a Winning Executive Summary." Technical Communication 41 (1994): 511-517; Murphy, Herta A., Herbert W. Hildebrandt, and Jane P. Thomas. Effective Business Communications . New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997; Vassallo, Philip. "Executive Summaries: Where Less Really is More." ETC.: A Review of General Semantics 60 (Spring 2003): 83-90 .

Structure and Writing Style

Writing an Executive Summary

Read the Entire Document This may go without saying, but it is critically important that you read the entire research study thoroughly from start to finish before you begin to write the executive summary. Take notes as you go along, highlighting important statements of fact, key findings, and recommended courses of action. This will better prepare you for how to organize and summarize the study. Remember this is not a brief abstract of 300 words or less but, essentially, a mini-paper of your paper, with a focus on recommendations.

Isolate the Major Points Within the Original Document Choose which parts of the document are the most important to those who will read it. These points must be included within the executive summary in order to provide a thorough and complete explanation of what the document is trying to convey.

Separate the Main Sections Closely examine each section of the original document and discern the main differences in each. After you have a firm understanding about what each section offers in respect to the other sections, write a few sentences for each section describing the main ideas. Although the format may vary, the main sections of an executive summary likely will include the following:

- An opening statement, with brief background information,

- The purpose of research study,

- Method of data gathering and analysis,

- Overview of findings, and,

- A description of each recommendation, accompanied by a justification. Note that the recommendations are sometimes quoted verbatim from the research study.

Combine the Information Use the information gathered to combine them into an executive summary that is no longer than 10% of the original document. Be concise! The purpose is to provide a brief explanation of the entire document with a focus on the recommendations that have emerged from your research. How you word this will likely differ depending on your audience and what they care about most. If necessary, selectively incorporate bullet points for emphasis and brevity. Re-read your Executive Summary After you've completed your executive summary, let it sit for a while before coming back to re-read it. Check to make sure that the summary will make sense as a separate document from the full research study. By taking some time before re-reading it, you allow yourself to see the summary with fresh, unbiased eyes.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Length of the Executive Summary As a general rule, the correct length of an executive summary is that it meets the criteria of no more pages than 10% of the number of pages in the original document, with an upper limit of no more than ten pages [i.e., ten pages for a 100 page document]. This requirement keeps the document short enough to be read by your audience, but long enough to allow it to be a complete, stand-alone synopsis. Cutting and Pasting With the exception of specific recommendations made in the study, do not simply cut and paste whole sections of the original document into the executive summary. You should paraphrase information from the longer document. Avoid taking up space with excessive subtitles and lists, unless they are absolutely necessary for the reader to have a complete understanding of the original document. Consider the Audience Although unlikely to be required by your professor, there is the possibility that more than one executive summary will have to be written for a given document [e.g., one for policy-makers, one for private industry, one for philanthropists]. This may only necessitate the rewriting of the introduction and conclusion, but it could require rewriting the entire summary in order to fit the needs of the reader. If necessary, be sure to consider the types of audiences who may benefit from your study and make adjustments accordingly. Clarity in Writing One of the biggest mistakes you can make is related to the clarity of your executive summary. Always note that your audience [or audiences] are likely seeing your research study for the first time. The best way to avoid a disorganized or cluttered executive summary is to write it after the study is completed. Always follow the same strategies for proofreading that you would for any research paper. Use Strong and Positive Language Don’t weaken your executive summary with passive, imprecise language. The executive summary is a stand-alone document intended to convince the reader to make a decision concerning whether to implement the recommendations you make. Once convinced, it is assumed that the full document will provide the details needed to implement the recommendations. Although you should resist the temptation to pad your summary with pleas or biased statements, do pay particular attention to ensuring that a sense of urgency is created in the implications, recommendations, and conclusions presented in the executive summary. Be sure to target readers who are likely to implement the recommendations.

Bailey, Edward, P. The Plain English Approach to Business Writing . (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 73-80; Christensen, Jay. Executive Summaries Complete The Report. California State University Northridge; Executive Summaries. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Clayton, John. "Writing an Executive Summary That Means Business." Harvard Management Communication Letter , 2003; Executive Summary. University Writing Center. Texas A&M University; Green, Duncan. Writing an Executive Summary. Oxfam’s Research Guidelines series ; Guidelines for Writing an Executive Summary. Astia.org; Markowitz, Eric. How to Write an Executive Summary. Inc. Magazine, September, 15, 2010; Kawaski, Guy. The Art of the Executive Summary. "How to Change the World" blog; Keller, Chuck. "Stay Healthy with a Winning Executive Summary." Technical Communication 41 (1994): 511-517; The Report Abstract and Executive Summary. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Executive Summaries. Effective Writing Center. University of Maryland; Kolin, Philip. Successful Writing at Work . 10th edition. (Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2013), p. 435-437; Moral, Mary. "Writing Recommendations and Executive Summaries." Keeping Good Companies 64 (June 2012): 274-278; Todorovic, Zelimir William and Marietta Wolczacka Frye. “Writing Effective Executive Summaries: An Interdisciplinary Examination.” In United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship. Conference Proceedings . (Decatur, IL: United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 2009): pp. 662-691.

- << Previous: 3. The Abstract

- Next: 4. The Introduction >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 10:51 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Recommended pages

- Undergraduate open days

- Postgraduate open days

- Accommodation

- Information for teachers

- Maps and directions

- Sport and fitness

How to Write a Research Proposal

As part of the application for admission onto our MJur, MPhil and PhD programmes, you must prepare a research proposal outlining your proposed area of study.

What is a research proposal?

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research. It sets out the central issues or questions that you intend to address. It outlines the general area of study within which your research falls, referring to the current state of knowledge and any recent debates on the topic. It also demonstrates the originality of your proposed research.

The proposal is the most important document that you submit as part of the application process. It gives you an opportunity to demonstrate that you have the aptitude for graduate level research, for example, by demonstrating that you have the ability to communicate complex ideas clearly, concisely and critically. The proposal also helps us to match your research interest with an appropriate supervisor.

What should you include in the proposal?

Regardless of whether you are applying for the MJur, MPhil or PhD programmes, your research proposal should normally include the following information:

This is just a tentative title for your intended research. You will be able to revise your title during the course of your research if you are accepted for admission.

Examples of the thesis titles of some of our current and recent research students can be seen on our Current Projects page .

2. Abstract

The proposal should include a concise statement of your intended research of no more than 100 words. This may be a couple of sentences setting out the problem that you want to examine or the central question that you wish to address.

3. Research Context

You should explain the broad background against which you will conduct your research. You should include a brief overview of the general area of study within which your proposed research falls, summarising the current state of knowledge and recent debates on the topic. This will allow you to demonstrate a familiarity with the relevant field as well as the ability to communicate clearly and concisely.

4. Research Questions

The proposal should set out the central aims and questions that will guide your research. Before writing your proposal, you should take time to reflect on the key questions that you are seeking to answer. Many research proposals are too broad, so reflecting on your key research questions is a good way to make sure that your project is sufficiently narrow and feasible (i.e. one that is likely to be completed with the normal period for a MJur, MPhil or PhD degree).

You might find it helpful to prioritize one or two main questions, from which you can then derive a number of secondary research questions. The proposal should also explain your intended approach to answering the questions: will your approach be empirical, doctrinal or theoretical etc?

5. Research Methods

The proposal should outline your research methods, explaining how you are going to conduct your research. Your methods may include visiting particular libraries or archives, field work or interviews.

Most research is library-based. If your proposed research is library-based, you should explain where your key resources (e.g. law reports, journal articles) are located (in the Law School’s library, Westlaw etc). If you plan to conduct field work or collect empirical data, you should provide details about this (e.g. if you plan interviews, who will you interview? How many interviews will you conduct? Will there be problems of access?). This section should also explain how you are going to analyse your research findings.

6. Significance of Research

The proposal should demonstrate the originality of your intended research. You should therefore explain why your research is important (for example, by explaining how your research builds on and adds to the current state of knowledge in the field or by setting out reasons why it is timely to research your proposed topic).

7. Bibliography

The proposal should include a short bibliography identifying the most relevant works for your topic.

How long should the proposal be?

The proposal should usually be around 2,500 words. It is important to bear in mind that specific funding bodies might have different word limits.

Can the School comment on my draft proposal?

We recognise that you are likely still developing your research topic. We therefore recommend that you contact a member of our staff with appropriate expertise to discuss your proposed research. If there is a good fit between your proposed research and our research strengths, we will give you advice on a draft of your research proposal before you make a formal application. For details of our staff and there areas of expertise please visit our staff pages .

Read a sample proposal from a successful application

Learn more about Birmingham's doctoral research programmes in Law:

Birmingham Law School is home to a broad range of internationally excellent and world-leading legal academics, with a thriving postgraduate research community. The perfect place for your postgraduate study.

Law PhD / PhD by Distance Learning / MPhil / MJur

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide [With Template]

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide [With Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write A Proposal

Writing a Proposal involves several key steps to effectively communicate your ideas and intentions to a target audience. Here’s a detailed breakdown of each step:

Identify the Purpose and Audience

- Clearly define the purpose of your proposal: What problem are you addressing, what solution are you proposing, or what goal are you aiming to achieve?

- Identify your target audience: Who will be reading your proposal? Consider their background, interests, and any specific requirements they may have.

Conduct Research

- Gather relevant information: Conduct thorough research to support your proposal. This may involve studying existing literature, analyzing data, or conducting surveys/interviews to gather necessary facts and evidence.

- Understand the context: Familiarize yourself with the current situation or problem you’re addressing. Identify any relevant trends, challenges, or opportunities that may impact your proposal.

Develop an Outline

- Create a clear and logical structure: Divide your proposal into sections or headings that will guide your readers through the content.

- Introduction: Provide a concise overview of the problem, its significance, and the proposed solution.

- Background/Context: Offer relevant background information and context to help the readers understand the situation.

- Objectives/Goals: Clearly state the objectives or goals of your proposal.

- Methodology/Approach: Describe the approach or methodology you will use to address the problem.

- Timeline/Schedule: Present a detailed timeline or schedule outlining the key milestones or activities.

- Budget/Resources: Specify the financial and other resources required to implement your proposal.

- Evaluation/Success Metrics: Explain how you will measure the success or effectiveness of your proposal.

- Conclusion: Summarize the main points and restate the benefits of your proposal.

Write the Proposal

- Grab attention: Start with a compelling opening statement or a brief story that hooks the reader.

- Clearly state the problem: Clearly define the problem or issue you are addressing and explain its significance.

- Present your proposal: Introduce your proposed solution, project, or idea and explain why it is the best approach.

- State the objectives/goals: Clearly articulate the specific objectives or goals your proposal aims to achieve.

- Provide supporting information: Present evidence, data, or examples to support your claims and justify your proposal.

- Explain the methodology: Describe in detail the approach, methods, or strategies you will use to implement your proposal.

- Address potential concerns: Anticipate and address any potential objections or challenges the readers may have and provide counterarguments or mitigation strategies.

- Recap the main points: Summarize the key points you’ve discussed in the proposal.

- Reinforce the benefits: Emphasize the positive outcomes, benefits, or impact your proposal will have.

- Call to action: Clearly state what action you want the readers to take, such as approving the proposal, providing funding, or collaborating with you.

Review and Revise

- Proofread for clarity and coherence: Check for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors.

- Ensure a logical flow: Read through your proposal to ensure the ideas are presented in a logical order and are easy to follow.

- Revise and refine: Fine-tune your proposal to make it concise, persuasive, and compelling.

Add Supplementary Materials

- Attach relevant documents: Include any supporting materials that strengthen your proposal, such as research findings, charts, graphs, or testimonials.

- Appendices: Add any additional information that might be useful but not essential to the main body of the proposal.

Formatting and Presentation

- Follow the guidelines: Adhere to any specific formatting guidelines provided by the organization or institution to which you are submitting the proposal.

- Use a professional tone and language: Ensure that your proposal is written in a clear, concise, and professional manner.

- Use headings and subheadings: Organize your proposal with clear headings and subheadings to improve readability.

- Pay attention to design: Use appropriate fonts, font sizes, and formatting styles to make your proposal visually appealing.

- Include a cover page: Create a cover page that includes the title of your proposal, your name or organization, the date, and any other required information.

Seek Feedback

- Share your proposal with trusted colleagues or mentors and ask for their feedback. Consider their suggestions for improvement and incorporate them into your proposal if necessary.

Finalize and Submit

- Make any final revisions based on the feedback received.

- Ensure that all required sections, attachments, and documentation are included.

- Double-check for any formatting, grammar, or spelling errors.

- Submit your proposal within the designated deadline and according to the submission guidelines provided.

Proposal Format

The format of a proposal can vary depending on the specific requirements of the organization or institution you are submitting it to. However, here is a general proposal format that you can follow:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your proposal, your name or organization’s name, the date, and any other relevant information specified by the guidelines.

2. Executive Summary:

- Provide a concise overview of your proposal, highlighting the key points and objectives.

- Summarize the problem, proposed solution, and anticipated benefits.

- Keep it brief and engaging, as this section is often read first and should capture the reader’s attention.

3. Introduction:

- State the problem or issue you are addressing and its significance.

- Provide background information to help the reader understand the context and importance of the problem.

- Clearly state the purpose and objectives of your proposal.

4. Problem Statement:

- Describe the problem in detail, highlighting its impact and consequences.

- Use data, statistics, or examples to support your claims and demonstrate the need for a solution.

5. Proposed Solution or Project Description:

- Explain your proposed solution or project in a clear and detailed manner.

- Describe how your solution addresses the problem and why it is the most effective approach.

- Include information on the methods, strategies, or activities you will undertake to implement your solution.

- Highlight any unique features, innovations, or advantages of your proposal.

6. Methodology:

- Provide a step-by-step explanation of the methodology or approach you will use to implement your proposal.

- Include a timeline or schedule that outlines the key milestones, tasks, and deliverables.

- Clearly describe the resources, personnel, or expertise required for each phase of the project.

7. Evaluation and Success Metrics:

- Explain how you will measure the success or effectiveness of your proposal.

- Identify specific metrics, indicators, or evaluation methods that will be used.

- Describe how you will track progress, gather feedback, and make adjustments as needed.

- Present a detailed budget that outlines the financial resources required for your proposal.

- Include all relevant costs, such as personnel, materials, equipment, and any other expenses.

- Provide a justification for each item in the budget.

9. Conclusion:

- Summarize the main points of your proposal.

- Reiterate the benefits and positive outcomes of implementing your proposal.

- Emphasize the value and impact it will have on the organization or community.

10. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as research findings, charts, graphs, or testimonials.

- Attach any relevant documents that provide further information but are not essential to the main body of the proposal.

Proposal Template

Here’s a basic proposal template that you can use as a starting point for creating your own proposal:

Dear [Recipient’s Name],

I am writing to submit a proposal for [briefly state the purpose of the proposal and its significance]. This proposal outlines a comprehensive solution to address [describe the problem or issue] and presents an actionable plan to achieve the desired objectives.

Thank you for considering this proposal. I believe that implementing this solution will significantly contribute to [organization’s or community’s goals]. I am available to discuss the proposal in more detail at your convenience. Please feel free to contact me at [your email address or phone number].

Yours sincerely,

Note: This template is a starting point and should be customized to meet the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the organization or institution to which you are submitting the proposal.

Proposal Sample

Here’s a sample proposal to give you an idea of how it could be structured and written:

Subject : Proposal for Implementation of Environmental Education Program

I am pleased to submit this proposal for your consideration, outlining a comprehensive plan for the implementation of an Environmental Education Program. This program aims to address the critical need for environmental awareness and education among the community, with the objective of fostering a sense of responsibility and sustainability.

Executive Summary: Our proposed Environmental Education Program is designed to provide engaging and interactive educational opportunities for individuals of all ages. By combining classroom learning, hands-on activities, and community engagement, we aim to create a long-lasting impact on environmental conservation practices and attitudes.

Introduction: The state of our environment is facing significant challenges, including climate change, habitat loss, and pollution. It is essential to equip individuals with the knowledge and skills to understand these issues and take action. This proposal seeks to bridge the gap in environmental education and inspire a sense of environmental stewardship among the community.

Problem Statement: The lack of environmental education programs has resulted in limited awareness and understanding of environmental issues. As a result, individuals are less likely to adopt sustainable practices or actively contribute to conservation efforts. Our program aims to address this gap and empower individuals to become environmentally conscious and responsible citizens.

Proposed Solution or Project Description: Our Environmental Education Program will comprise a range of activities, including workshops, field trips, and community initiatives. We will collaborate with local schools, community centers, and environmental organizations to ensure broad participation and maximum impact. By incorporating interactive learning experiences, such as nature walks, recycling drives, and eco-craft sessions, we aim to make environmental education engaging and enjoyable.

Methodology: Our program will be structured into modules that cover key environmental themes, such as biodiversity, climate change, waste management, and sustainable living. Each module will include a mix of classroom sessions, hands-on activities, and practical field experiences. We will also leverage technology, such as educational apps and online resources, to enhance learning outcomes.

Evaluation and Success Metrics: We will employ a combination of quantitative and qualitative measures to evaluate the effectiveness of the program. Pre- and post-assessments will gauge knowledge gain, while surveys and feedback forms will assess participant satisfaction and behavior change. We will also track the number of community engagement activities and the adoption of sustainable practices as indicators of success.

Budget: Please find attached a detailed budget breakdown for the implementation of the Environmental Education Program. The budget covers personnel costs, materials and supplies, transportation, and outreach expenses. We have ensured cost-effectiveness while maintaining the quality and impact of the program.

Conclusion: By implementing this Environmental Education Program, we have the opportunity to make a significant difference in our community’s environmental consciousness and practices. We are confident that this program will foster a generation of individuals who are passionate about protecting our environment and taking sustainable actions. We look forward to discussing the proposal further and working together to make a positive impact.

Thank you for your time and consideration. Should you have any questions or require additional information, please do not hesitate to contact me at [your email address or phone number].

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

How to write a research proposal?

Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Devika Rani Duggappa

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

INTRODUCTION

A clean, well-thought-out proposal forms the backbone for the research itself and hence becomes the most important step in the process of conduct of research.[ 1 ] The objective of preparing a research proposal would be to obtain approvals from various committees including ethics committee [details under ‘Research methodology II’ section [ Table 1 ] in this issue of IJA) and to request for grants. However, there are very few universally accepted guidelines for preparation of a good quality research proposal. A search was performed with keywords such as research proposal, funding, qualitative and writing proposals using search engines, namely, PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus.

Five ‘C’s while writing a literature review

BASIC REQUIREMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

A proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new paradigm will it add to the literature, while specifying the question that the research will answer, establishing its significance, and the implications of the answer.[ 2 ] The proposal must be capable of convincing the evaluation committee about the credibility, achievability, practicality and reproducibility (repeatability) of the research design.[ 3 ] Four categories of audience with different expectations may be present in the evaluation committees, namely academic colleagues, policy-makers, practitioners and lay audiences who evaluate the research proposal. Tips for preparation of a good research proposal include; ‘be practical, be persuasive, make broader links, aim for crystal clarity and plan before you write’. A researcher must be balanced, with a realistic understanding of what can be achieved. Being persuasive implies that researcher must be able to convince other researchers, research funding agencies, educational institutions and supervisors that the research is worth getting approval. The aim of the researcher should be clearly stated in simple language that describes the research in a way that non-specialists can comprehend, without use of jargons. The proposal must not only demonstrate that it is based on an intelligent understanding of the existing literature but also show that the writer has thought about the time needed to conduct each stage of the research.[ 4 , 5 ]

CONTENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

The contents or formats of a research proposal vary depending on the requirements of evaluation committee and are generally provided by the evaluation committee or the institution.

In general, a cover page should contain the (i) title of the proposal, (ii) name and affiliation of the researcher (principal investigator) and co-investigators, (iii) institutional affiliation (degree of the investigator and the name of institution where the study will be performed), details of contact such as phone numbers, E-mail id's and lines for signatures of investigators.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations.[ 4 ]

Introduction

It is also sometimes termed as ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract’. Introduction is an initial pitch of an idea; it sets the scene and puts the research in context.[ 6 ] The introduction should be designed to create interest in the reader about the topic and proposal. It should convey to the reader, what you want to do, what necessitates the study and your passion for the topic.[ 7 ] Some questions that can be used to assess the significance of the study are: (i) Who has an interest in the domain of inquiry? (ii) What do we already know about the topic? (iii) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (iv) How will this research add to knowledge, practice and policy in this area? Some of the evaluation committees, expect the last two questions, elaborated under a separate heading of ‘background and significance’.[ 8 ] Introduction should also contain the hypothesis behind the research design. If hypothesis cannot be constructed, the line of inquiry to be used in the research must be indicated.

Review of literature

It refers to all sources of scientific evidence pertaining to the topic in interest. In the present era of digitalisation and easy accessibility, there is an enormous amount of relevant data available, making it a challenge for the researcher to include all of it in his/her review.[ 9 ] It is crucial to structure this section intelligently so that the reader can grasp the argument related to your study in relation to that of other researchers, while still demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. It is preferable to summarise each article in a paragraph, highlighting the details pertinent to the topic of interest. The progression of review can move from the more general to the more focused studies, or a historical progression can be used to develop the story, without making it exhaustive.[ 1 ] Literature should include supporting data, disagreements and controversies. Five ‘C's may be kept in mind while writing a literature review[ 10 ] [ Table 1 ].

Aims and objectives

The research purpose (or goal or aim) gives a broad indication of what the researcher wishes to achieve in the research. The hypothesis to be tested can be the aim of the study. The objectives related to parameters or tools used to achieve the aim are generally categorised as primary and secondary objectives.

Research design and method

The objective here is to convince the reader that the overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the research problem and to impress upon the reader that the methodology/sources chosen are appropriate for the specific topic. It should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

In this section, the methods and sources used to conduct the research must be discussed, including specific references to sites, databases, key texts or authors that will be indispensable to the project. There should be specific mention about the methodological approaches to be undertaken to gather information, about the techniques to be used to analyse it and about the tests of external validity to which researcher is committed.[ 10 , 11 ]

The components of this section include the following:[ 4 ]

Population and sample

Population refers to all the elements (individuals, objects or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe,[ 12 ] and sample refers to subset of population which meets the inclusion criteria for enrolment into the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined. The details pertaining to sample size are discussed in the article “Sample size calculation: Basic priniciples” published in this issue of IJA.

Data collection

The researcher is expected to give a detailed account of the methodology adopted for collection of data, which include the time frame required for the research. The methodology should be tested for its validity and ensure that, in pursuit of achieving the results, the participant's life is not jeopardised. The author should anticipate and acknowledge any potential barrier and pitfall in carrying out the research design and explain plans to address them, thereby avoiding lacunae due to incomplete data collection. If the researcher is planning to acquire data through interviews or questionnaires, copy of the questions used for the same should be attached as an annexure with the proposal.

Rigor (soundness of the research)

This addresses the strength of the research with respect to its neutrality, consistency and applicability. Rigor must be reflected throughout the proposal.

It refers to the robustness of a research method against bias. The author should convey the measures taken to avoid bias, viz. blinding and randomisation, in an elaborate way, thus ensuring that the result obtained from the adopted method is purely as chance and not influenced by other confounding variables.

Consistency

Consistency considers whether the findings will be consistent if the inquiry was replicated with the same participants and in a similar context. This can be achieved by adopting standard and universally accepted methods and scales.

Applicability

Applicability refers to the degree to which the findings can be applied to different contexts and groups.[ 13 ]

Data analysis

This section deals with the reduction and reconstruction of data and its analysis including sample size calculation. The researcher is expected to explain the steps adopted for coding and sorting the data obtained. Various tests to be used to analyse the data for its robustness, significance should be clearly stated. Author should also mention the names of statistician and suitable software which will be used in due course of data analysis and their contribution to data analysis and sample calculation.[ 9 ]

Ethical considerations

Medical research introduces special moral and ethical problems that are not usually encountered by other researchers during data collection, and hence, the researcher should take special care in ensuring that ethical standards are met. Ethical considerations refer to the protection of the participants' rights (right to self-determination, right to privacy, right to autonomy and confidentiality, right to fair treatment and right to protection from discomfort and harm), obtaining informed consent and the institutional review process (ethical approval). The researcher needs to provide adequate information on each of these aspects.

Informed consent needs to be obtained from the participants (details discussed in further chapters), as well as the research site and the relevant authorities.

When the researcher prepares a research budget, he/she should predict and cost all aspects of the research and then add an additional allowance for unpredictable disasters, delays and rising costs. All items in the budget should be justified.

Appendices are documents that support the proposal and application. The appendices will be specific for each proposal but documents that are usually required include informed consent form, supporting documents, questionnaires, measurement tools and patient information of the study in layman's language.

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your proposal. Although the words ‘references and bibliography’ are different, they are used interchangeably. It refers to all references cited in the research proposal.

Successful, qualitative research proposals should communicate the researcher's knowledge of the field and method and convey the emergent nature of the qualitative design. The proposal should follow a discernible logic from the introduction to presentation of the appendices.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on 13 June 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organised and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, frequently asked questions.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .