Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Case study of a patient with tuberculosis

15 Case study of a patient with tuberculosis Maria Mercer Chapter aims • To provide you with a case study of a patient who has been diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) together with the rationale for care • To encourage you to research and deepen your knowledge of TB Introduction This chapter provides you with an example of the nursing care that a patient with pulmonary TB might require. The case study has been written by a TB nurse specialist and provides you with a patient profile to enable you to understand the context of the patient. The case study aims to guide you through the assessment, nursing action and evaluation of a patient with pulmonary TB together with the rationale for care. Activity In Chapter 1 you were asked to revise the normal anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system (see Montague et al 2005 ) and a brief definition of TB was given. Before reading the case study below, find out how pulmonary TB would affect the respiratory system and what symptoms a patient with TB might present with. The following article may help you: William VG (2006). Tuberculosis: clinical features, diagnosis and management. Nursing Standard 20(22):49–53. Online. Available at: http://nursingstandard.rcnpublishing.co.uk/archive/article-tuberculosis-clinical-features-diagnosis-and-management (accessed July 2011). Patient profile Mr Patel is a 21-year-old gentleman who lives in a shared flat with friends and studies English at a local college. He is a new arrival to the UK having arrived from Bangladesh in October 2009. There are six adults, including Mr Patel, who share a two-bedroom flat. They share three adults to a room. He was referred to accident and emergency (A&E) via his GP with a 2-month history of a productive cough (no episodes of haemoptysis), associated fevers, drenching night sweats, loss of appetite and a 5-kg weight loss. In the last 7 days his symptoms have worsened and warranted the admission via A&E. Assessment on admission Mr Patel has a pyrexia of 38.5°C, he is cachectic and has pleuritic chest pain. His respiratory rate is slightly raised at 18 per minute and he has a tachycardia of 114 beats per minute. Blood pressure is normal. Inflammatory markers – erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) – are raised at 72 mm/h and 65.4 mg/L. A chest X-ray has been reported as abnormal: ‘Patchy shadowing seen in left upper lobe? Pulmonary TB.’ Activity See Appendix 4 in Holland et al ( 2008 ) for possible questions to consider during the assessment stage of care planning. Mr Patel’s problems Based on your assessment of Mr Patel, the following problems should form the basis of your care plan: • Mr Patel has a potential diagnosis of pulmonary TB which can be an infectious disease and public health risk. • Mr Patel feels stigmatised because of respiratory isolation measures and the potential diagnosis of TB. • Mr Patel has a temperature, raised inflammatory markers, a slightly elevated respiratory rate and a tachycardia. • Mr Patel is nutritionally compromised because of a 5-kg weight loss due to anorexia. • Mr Patel has pleuritic chest pain associated with coughing and expectoration of sputum. Mr Patel’s nursing care plans 1. Problem: Mr Patel has an infection. Pulmonary TB is felt to be the primary diagnosis. Goal: To limit transmission of TB to other patients and staff and ensure prompt treatment is commenced. Nursing action Rationale Mr Patel to be isolated in a side room with bathroom facilities with respiratory isolation measures in place immediately The door to the side room must be shut at all times Appropriate face masks (FFP2 or FFP3, depending on risk assessment – refer to infection control/TB policy) should be worn when entering Mr Patel’s room and he should wear the appropriate face mask if he needs to leave the side room for investigations Gloves and aprons do not need to be worn unless handling bodily secretions Liaise with bed managers and infection control team to expedite bed availability as necessary To reduce the risk of TB transmission to other patients and staff Collect three consecutive sputum specimens for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) Send one sputum specimen urgently on day of admission To ascertain diagnosis and ensure the appropriate treatment is commenced promptly Ensure Mr Patel is aware that sputum specimens need to be collected consecutively. Label 3 sputum pots clearly and leave in side room. Instruct Mr Patel to inform the nurse caring for him when the sputum for each day is ready so it can be collected and sent to the Laboratory as soon as possible. To ascertain diagnosis and ensure the appropriate treatment is commenced promptly. Contact the TB nurses to perform a Mantoux test if prescribed by the medical staff. To facilitate prompt diagnosis and obtain specialist nursing advice and support Ensure effective communication with Mr Patel explaining why the above measures are necessary and providing reassurance and support To alleviate fear and anxiety Evaluation:

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Medical placements

- Revision and future learning

- The end of the journey

- Medicines management

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

A case study of a patient with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

Affiliation.

- 1 Community nurse working in South West England.

- PMID: 30048191

- DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.14.806

In this case study, a nurse presents her reflections on the challenges of supporting a patient through his treatment journey for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The patient has significant comorbidities and social issues, such as diabetes and homelessness. There was also a language barrier. All these aspects made the management of his treatment challenging. The medication side effects and his lifestyle were also a barrier to full engagement. The same multidisciplinary team was involved with the patient and, despite the obstacles, he seemed willing to engage with treatment and the team.

Keywords: Comorbidities; Language barrier; Multidisciplinary team; Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis; Pulmonary TB; Under-served population.

- Alcohol Drinking

- Antitubercular Agents / administration & dosage

- Antitubercular Agents / therapeutic use*

- Communication Barriers

- Diabetes Complications

- Drug Therapy, Combination

- Social Support

- Tuberculosis, Multidrug-Resistant / complications

- Tuberculosis, Multidrug-Resistant / drug therapy*

- Tuberculosis, Multidrug-Resistant / nursing*

- United Kingdom

- Antitubercular Agents

TB Personal Stories

TB is still a life-threatening problem in this country. TB knows no borders, and people here in the United States are suffering from TB. Anyone can get TB. These stories highlight the personal experiences of people who were diagnosed and treated for latent TB infection and TB disease, as well as the work of TB control professionals.

- TB Personal Stories from TB Free California external icon

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 19 November 2022

A case report of persistent drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis after treatment completion

- Sergo A. Vashakidze 1 , 2 ,

- Abivarma Chandrakumaran 3 ,

- Merab Japaridze 1 ,

- Giorgi Gogishvili 1 ,

- Jeffrey M. Collins 4 ,

- Manana Rekhviashvili 1 &

- Russell R. Kempker 4

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 22 , Article number: 864 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5225 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) has been found to persist within cavities in patients who have completed their anti-tuberculosis therapy. The clinical implications of Mtb persistence after therapy include recurrence of disease and destructive changes within the lungs. Data on residual changes in patients who completed anti-tuberculosis therapy are scarce. This case highlights the radiological and pathological changes that persist after anti-tuberculosis therapy completion and the importance of achieving sterilization of cavities in order to prevent these changes.

Case presentation

This is a case report of a 33 year old female with drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis who despite successfully completing standard 6-month treatment had persistent changes in her lungs on radiological imaging. The patient underwent multiple adjunctive surgeries to resect cavitary lesions, which were culture positive for Mtb. After surgical treatment, the patient’s chest radiographies improved, symptoms subsided, and she was given a definition of cure.

Conclusions

Medical therapy alone, in the presence of severe cavitary lung lesions may not be able to achieve sterilizing cure in all cases. Cavities can not only cause reactivation but also drive inflammatory changes and subsequent lung damage leading to airflow obstruction, bronchiectasis, and fibrosis. Surgical removal of these foci of bacilli can be an effective adjunctive treatment necessary for a sterilizing cure and improved long term lung health.

Peer Review reports

Mycobacterium tuberculosis treatment has been evolving over the years, especially with the introduction of newer drugs and shorter regimens [ 1 , 2 ]. Apart from the cavitary nature of tuberculous disease, patients who have been treated with current regimens often are given the designation of cure without achieving proper sterilization. Patients who complete the tuberculous regimen are given the definition of cure after they achieve sputum negativity but many of these patients harbor bacilli within cavities that continue to exert their effects on the respiratory system [ 3 ]. The residual changes that occur in patients who have completed medical therapy have been poorly attended to in the literature. Patients that underwent surgical and medical sterilization have been reported to have better pulmonary health in the long term, especially after the removal of cavities [ 4 ].

Here, we report a patient who underwent a complete regimen of medical therapy for pulmonary tuberculosis and later had to have surgical resection of her cavities, which grew tuberculous bacilli even after achieving sputum negativity.

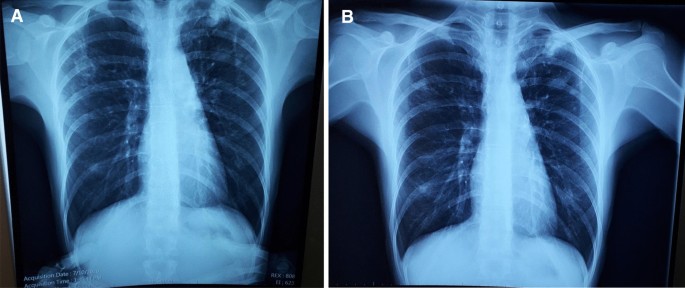

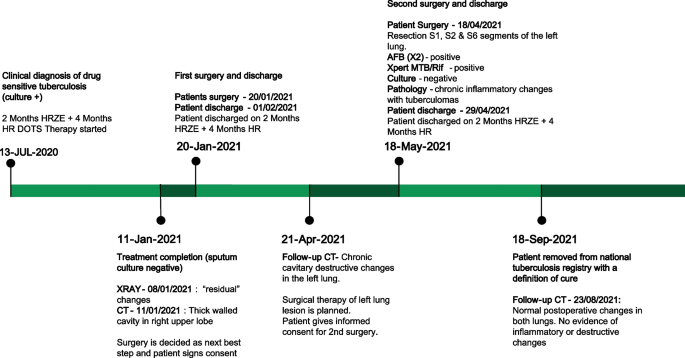

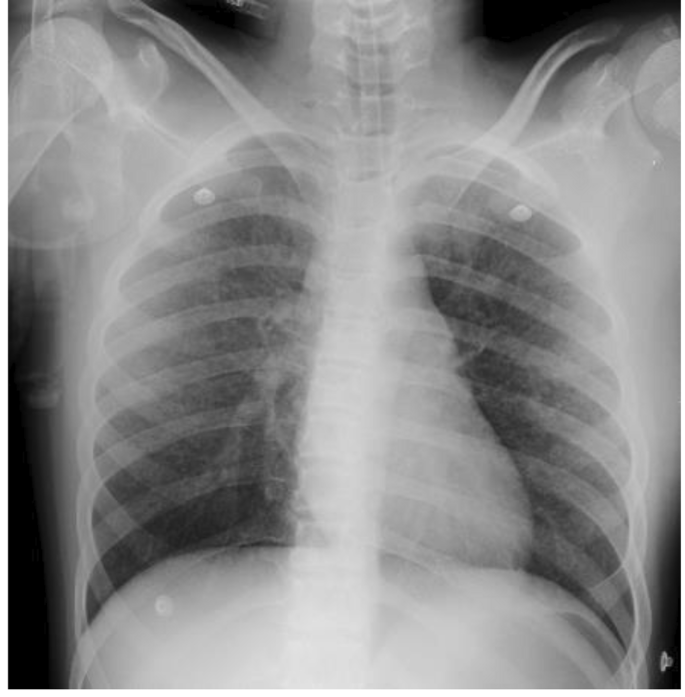

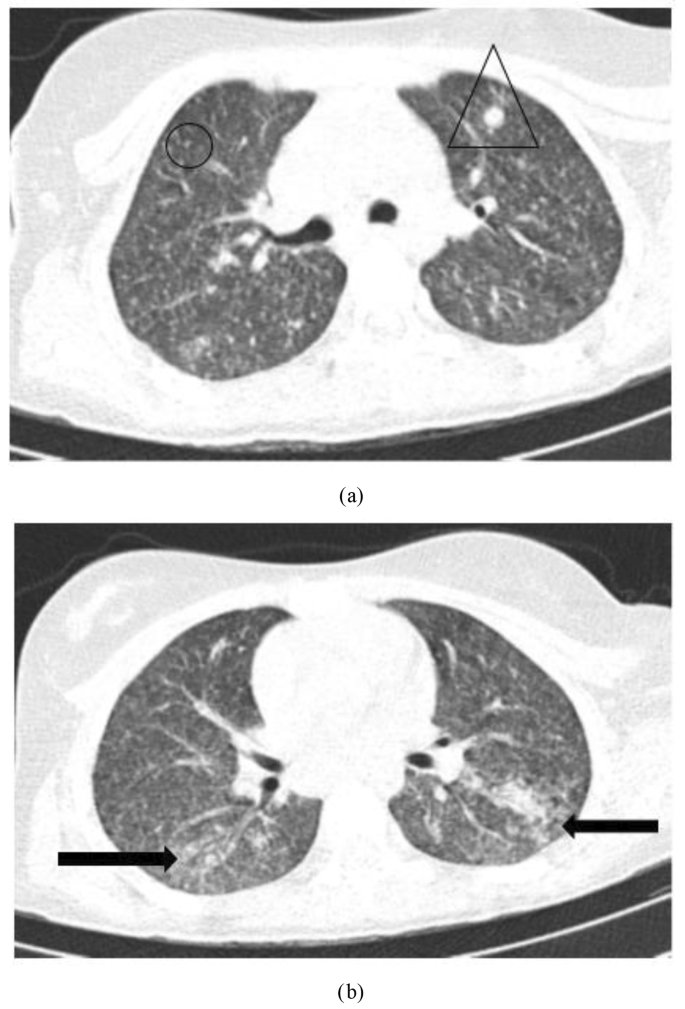

A 33-year-old female from the country of Georgia presented to a tuberculosis dispensary on July 10, 2020, with a temperature of 38° C and symptoms of malaise, productive cough, and night sweats. The patient had no known medical problems. She reported smoking ~ 10 cigarettes daily and denied alcohol or illicit drug use. She had 3 children and her husband was a prisoner being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. Upon physical examination there were decreased breath sounds in the upper lobes of the lungs with dullness to percussion. The patient had a body mass index (BMI) of 16.3 kg/m 2 . A complete blood count revealed a moderate leukocytosis of 10.2 × 10 9 /L and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 42 mm/h. Biochemical blood parameters were normal. Sputum testing found a negative acid-fast bacilli (AFB) microscopy, positive Xpert MTB/RIF test (no RIF resistance), and positive culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Additionally, drug susceptibility testing (DST) revealed sensitivity to rifampin, isoniazid, and ethambutol. Chest radiography revealed multiple small foci in the upper lobes of both lungs and a cavity in the right lung (Fig. 1 A). The patient was initiated on daily outpatient treatment with three pills of a fixed dosed combination pill containing isoniazid 75 mg, rifampin 150 mg, ethambutol 275 mg and pyrazinamide 400 mg. Treatment was given through directly observed therapy (DOT). She converted her sputum cultures to negative at 2 months and continued rifampin and isoniazid to finish 6 months of treatment. An end of treatment chest x-ray revealed fibrosis and honeycombing in the right upper lung, and fibrosis and dense focal shadows in the 1st and 2nd intercostal spaces of the left lung (Fig. 1 B). The complete treatment timeline is summarized in Fig. 2 .

A (left): Baseline chest X-ray showing a cavity in the right lung and multiple foci in the upper lobes of both lungs. B (right): End of initial treatment chest X-ray, showing fibrosis, local honeycombing and dense focal shadows in both lungs

Patient treatment timeline ( HRZE isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol; HR isoniazid & rifampin; DOTS directly observed therapy, short-course; CT computed tomography; AFB acid fast bacilli)

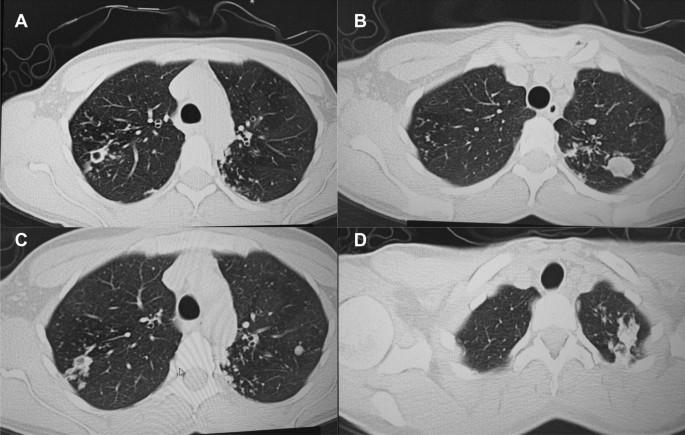

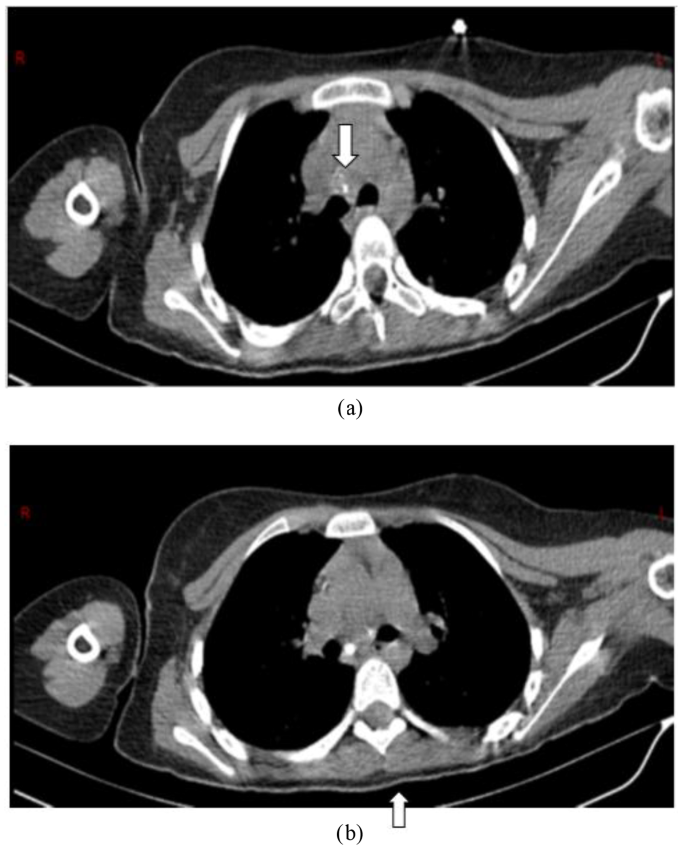

A follow up chest computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a cavity in the right upper lobe measuring 12 × 10 mm in size with a thick and heterogeneous wall and nodules and bronchiectasis in the left lung (Fig. 3 A–D). Based on CT findings and in accordance with National tuberculosis guidelines, the patient was offered surgical resection of the affected portion of the lung. It should be noted that the patient reported no symptoms, complaints, or functional disability before the surgery. Preoperative workup including pulmonary function testing, an echocardiogram, bronchoscopy, and blood chemistries were normal. The patient consented to surgery and underwent a surgical resection of the S1 and S2 segments of the right lung 2 weeks later. Intraoperatively, moderate adhesions were visualized in the S1 and S2 area with a palpable dense formation ~ 3.0 cm in diameter, in addition to a dense nodule. Gross pathology of the resected lesion showed a thick-walled fibrous cavity filled with caseous necrosis (Fig. 4 A) corresponding to the right preoperative CT lesion seen on Fig. 3 A, C.

CT scan (January 11, 2021) showing, A a cavity in the upper lobe of the right lung with heterogeneous thick walls. B S1 and S2 segments of the left lung shows a 23 × 18 mm oval shaped calcified inclusions; C , D areas with calcified, compacted nodules 13 × 20 mm in size with additional traction bronchiectasis

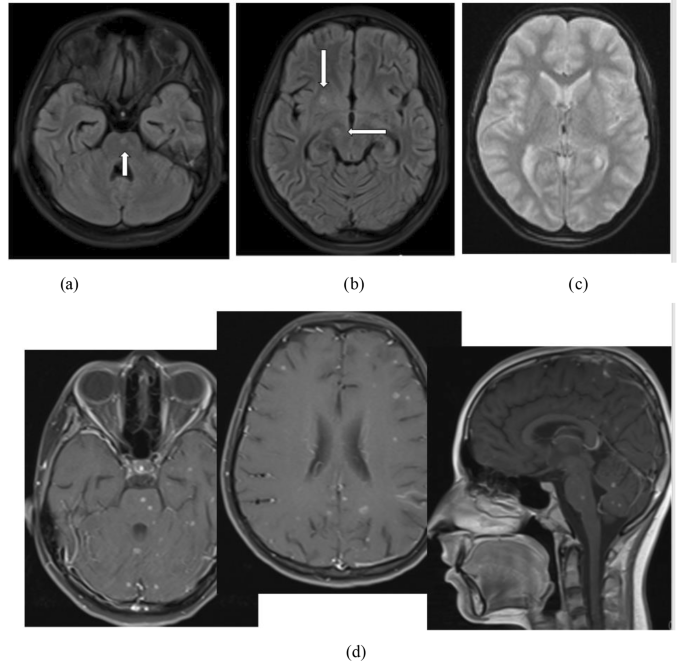

A Gross pathological image of a resected cavity with caseous material from first surgery (S1 & S2 segment of right lung). B The gross pathology from the second surgery showed the presence of a blocked cavity measuring up to 2 cm in diameter filled with caseous material in the S1, S2 and C Tuberculoma in S6 segment

Microbiological analysis on the resected tissue revealed acid-fast bacilli on microscopy, and positive Xpert MTB/RIF and culture results. Mtb grew from the caseous center, inner and outer walls of the cavity and a resected foci located ~ 3 cm from the cavity. DST revealed sensitivity to isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol.

Pathological examination of the resected lesion showed findings consistent with fibrocavernous tuberculosis. No postoperative complications were experienced, and the patient reinitiated first-line therapy via DOT on the 2nd postoperative day and was discharged on postoperative day 11.

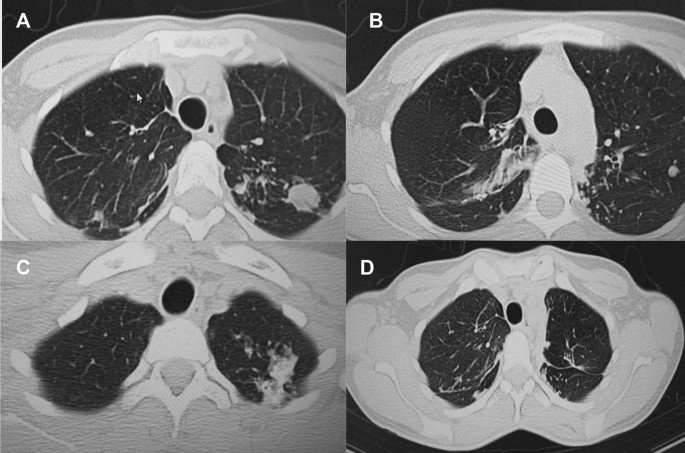

A follow up CT scan performed after 3 months showed postoperative changes in the right upper lobe, and an unchanged left lung (Fig. 5 A–C). Based on the persistent conglomerate of tuberculomas and multiple small tuberculous foci, growth of Mtb from the previous surgical specimen, and the patient’s social situation (mother of three young children) a second surgery to optimize the chance of cure was recommended. The patient reported no symptoms, complaints, or functional disability before the surgery. Preoperative sputum testing found negative AFB smear microscopy and culture. The patient underwent the second operation on May 18, 2021, in which the S1, S2 and part of the S6 segment of the left lung were resected. Intraoperatively, moderate adhesions seen along with a dense palpable ~ 3 cm mass in the S1 and S2 region and a dense focus in S6.

A – C Follow-up CT scan after first adjunctive surgery showing postoperative changes of the right lung and radiological changes in the left lung, that were unchanged compared to the initial CT. D Final CT scan showing normal postoperative changes with no cavities as previously seen

Microbiological examinations performed on resected tissue revealed positive AFB smear microscopy and Xpert MTB/RIF results and a negative AFB culture. The pathological examination of the surgical samples indicated a variety of destructive changes in addition to ongoing inflammation. The gross specimen of S1 and S2 segments of the left lung showed fibrocavernous tuberculosis shown in Fig. 4 B, which corresponds to the left lung lesion seen on the first preoperative CT in Figs. 3 B and 5 A in the second preoperative CT; the gross specimen of the S6 segment showed progressive tuberculoma seen in Fig. 4 C, which corresponds to the left lung lesion seen on the first preoperative CT in Figs. 3 D and 5 C in the second preoperative CT.

There were no postoperative complications, and tuberculosis (TB) treatment was reinitiated. The patient successfully completed treatment with normalization of clinical and laboratory parameters and a clinical outcome of cure in September 2021, ~ 14 months after beginning treatment. The patient had reported near complete resolution of her symptoms, having a much better ability to perform her daily activities. The patient appreciated the effects surgery had on her recovery and was happy to have gone through that treatment route. A post treatment CT scan demonstrated postoperative changes in the upper segments of both lungs (Fig. 5 D). Results from post treatment lung function testing were all within normal range.

Discussion and conclusions

We present this case to highlight the heterogeneous nature of pulmonary tuberculosis and need for an individualized treatment approach, especially for patients with cavitary disease. Over the last decade, novel diagnostics, drugs, and treatment regimens have revolutionized TB management including a recent landmark clinical trial demonstrating an effective 4-month regimen for drug-susceptible TB [ 1 ]. The move towards shorter regimens is critical to improve treatment completion rates and help meet TB elimination goals. However, during a transition to shorter treatment durations it is imperative that clinicians remain aware of complex and severe pulmonary TB cases that may require longer durations of treatment and adjunctive therapies such as surgery. Supporting evidence comes from a recent landmark study finding persistent inflammation on imaging associated with finding Mtb mRNA in sputum after successful treatment and a meta-analysis demonstrating a hard-to-treat TB phenotype not cured with the standard 6 months of treatment [ 2 , 5 ]. However, regarding recommendations for prolonging treatment beyond 6 months for drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis, ATS/CDC/IDSA recommends (expert opinion) extended treatment for persons with cavitary disease and a positive 2 month culture (our patient would not have met this criteria); World Health Organization (WHO) does not recommend extended treatment for any persons with drug-susceptible TB [ 6 , 7 ]. Accumulating evidence demonstrates surgical resection may be an effective adjunctive treatment in cases with cavitary disease [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Ultimately, a precision medicine approach towards TB will be able to identify patients who would benefit from short course therapy and those who would benefit from longer therapy and adjunctive treatment including surgery [ 13 ].

Mtb has a unique ability and propensity to induce cavities in humans with various studies showing cavitary lesions in ~ 30 to 85% of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis [ 14 ]. Lung cavities are more common in certain groups including patients with diabetes mellitus and undernutrition such as our patient who had a baseline BMI of 16.3 kg/m 2 [ 15 , 16 ]. Their presence indicates more advanced and severe pulmonary disease as evidenced by their association with worse clinical outcomes. Cavitary disease has been associated with higher rates of treatment failure, disease relapse, acquired drug resistance, and long term-term pulmonary morbidity [ 2 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. The impact of cavitary disease may be more pronounced in drug-resistant disease as shown in an observational study from our group which found a five times higher rate of acquired drug resistance and eight times higher rate of treatment failure among patients multidrug- or extensively drug-resistant cavitary disease compared to those without [ 20 ].

Mtb cavities are characterized by a fibrotic surface with variable vascularization, a lymphocytic cuff at the periphery followed by a cellular layer consisting of primarily macrophages and a necrotic center with foamy apoptotic macrophages and high concentrations of bacteria. Historically, each portion of the TB cavity has been conceptualized as concentric layers of a spherical structure due to its appearance on histologic cross-sections. However, recent studies using more detailed imaging techniques have shown most TB cavities exhibit complex structures with diverse, branching morphologies [ 21 ]. A dysregulated host immune response to Mtb is thought to contribute to the development of lung cavities, which may explain why cavitary lesions are seen less frequently among immunosuppressed patients including people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [ 14 ]. The center of the TB cavity (caseum) is characterized by accumulation of pro-inflammatory lipid signaling molecules (eicosanoids) and reactive oxygen species, which result in ongoing tissue destruction, but do little to control Mtb replication [ 22 ]. Conversely, the cellular rim and lymphocytic cuff are characterized by a lower abundance of pro-inflammatory lipids and increases in immunosuppressive signals including elevated expression of TGF-beta and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-1 [ 22 ]. The anti-inflammatory milieu within these TB cavity microenvironments impairs effector T cell responses, further limiting control of bacterial replication [ 23 , 24 , 25 ].

The combination of impaired cell-mediated immune responses with accumulation of inflammatory mediators at the rim of the caseum leads to ongoing tissue destruction with the potential for long-term pulmonary sequelae. Many with cavitary tuberculosis suffer chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after successful treatment and the risk may be greater in those with multidrug-resistant disease [ 3 , 4 ]. This has led to research into adjunctive treatment with immune modulator therapies with a goal of mitigating the over-exuberant inflammatory response at the interior edge of the cavity to limit tissue damage. In a recent randomized clinical trial, patients with radiographically severe pulmonary tuberculosis treated with adjunctive everolimus or CC-11050 (phosphodiesterase inhibitor with anti-inflammatory properties) achieved better long-term pulmonary outcomes versus those who received placebo [ 26 ]. Such results suggest the inflammatory response can be modified with appropriate host-directed therapies to improve pulmonary outcomes, particularly in those with cavitary tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis cavities not only hinder an effective immune response, but also prevent anti-tuberculosis drugs from achieving sterilizing concentrations throughout the lesion and especially in necrotic regions. The necrotic center of cavitary lesions is associated with extremely high rates of bacilli (up to 10 9 per milliliter), many of which enter a dormant state with reduced metabolic activity. Bacilli in this dormant state may be less responsive to the host immune response and exhibit phenotypic resistance to some anti-tuberculosis drugs thereby preventing sterilization and increasing chances of relapse [ 14 , 27 , 28 ]. The fact that the specimens from our patient’s second surgery were Xpert and AFB positive, but culture negative may indicate the presence of either dead bacilli or metabolically altered(dormant) bacilli that may be alive, but not culturable by standard techniques. Further, genomic sequencing studies have also found distinct strains of Mtb within different areas of the cavity that have varying drug-susceptibilities demonstrating cavities as a potential incubator for drug resistance [ 27 , 29 ].

Emerging literature has started to elucidate the varying abilities of drugs to penetrate into cavitary lesions and the importance of adequate target site concentrations. One notable study found that decreasing tissue concentrations within resected cavitary TB lesions were associated with increasing drug phenotypic MIC values [ 30 ]. Innovative studies using MALDI mass spectrometry imaging have further demonstrated varied spatiotemporal penetration of anti-TB drugs in human TB cavities [ 31 ]. This study found rifampin accumulated within caseum, moxifloxacin preferentially at the cellular rim, and pyrazinamide throughout the lesion, demonstrating the need to consider drug penetration when designing drug regimens in patients with cavitary TB. Computational modeling studies have further demonstrated the importance of complete lesion drug coverage to ensure relapse-free cure [ 32 ]. Furthermore, clinical trials are now incorporating these principles into study design by (1) using radiological characteristics to determine treatment length and (2) incorporating tissue penetration into drug selection and regimen design [ 33 , 34 ]. Beyond tissue penetration, varying drug levels and rapid INH acetylation status can also lead to suboptimal pharmacokinetics and poor clinical outcomes [ 35 , 36 ]. As highlighted in a recent expert document, clinical standards to optimize and individualize dosing need to be developed to improve outcomes [ 37 ].

Available literature points to a benefit of adjunctive surgical resection particularly among patients with drug resistant tuberculosis. A meta-analysis of 24 comparative studies found surgical intervention was associated with favorable treatment outcomes among patients with drug-resistant TB (odds ratio 2.24, 95% CI 1.68–2.97) [ 38 ]. Additionally, an individual patient data meta-analysis found that partial lung resection (adjusted OR 3.9, 95% CI 1.5–5.9) but not pneumectomy was associated with treatment success [ 39 ]. In two observational studies, we have also found that adjunctive surgical resection was associated with high and improved outcomes compared to patients with cavitary disease not undergoing surgery and was associated with less reentry into TB care. It should be noted that all studies of surgical resection for pulmonary TB were observational studies, which may be subject to selection bias, and no clinical trials (very difficult to implement in practice) were conducted to provide more conclusive evidence. Based on available evidence, the WHO has provided guidance to consider surgery among certain hard to treat cases of both drug-susceptible and resistant cavitary disease [ 40 ]. Criteria for surgical intervention included (1) failure of medical therapy (persistent sputum culture positive for M. tuberculosis ), (2) a high likelihood of treatment failure or disease relapse, (3) complications from the disease, (4) localized cavitary lesion, and (5) sufficient pulmonary function to tolerate surgery. For our patient, the severity of disease, lack of improvement of radiological imaging despite appropriate treatment, and high risk of relapse were the main indicators for surgery. Contraindications for surgery included a forced expiratory volume (FEV1) < 1000 mL, severe malnutrition, or patients at high risk for perioperative cardiovascular complications. With strict adherence to indications and contraindications for surgery, an acceptable level of postoperative complications are noted (5–17%) [ 4 , 38 ]. Our results also demonstrate the safety of adjunctive surgery, as our post-operative complication rate (8%) was low with the majority being minor complications [ 41 ].

As our case highlights, patients with persistent cavitary disease at the end of treatment require close clinical follow up and a tailored, individualized plan to determine the best approach for disease elimination and cure. In certain cases, including those with persistent cavitary disease and end of treatment, and where available, surgical resection is an effective adjunctive treatment option that can reduce disease burden and aid anti-tuberculosis agents in providing a sterilizing cure. As we enter an era of welcomed new shorter treatment options for tuberculosis it is imperative for clinicians to be able to identify and recognize complicated TB cases that require prolonged treatment and potentially adjunctive surgery.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

Acid fast bacilli

American Thoracic Society

Body mass index

Center for Disease Control

Computed tomography

Directly observed therapy

Drug sensitive tuberculosis

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Infectious Diseases Society of America

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Tuberculosis

World Health Organization

Dorman S, Nahid P, Kurbatova E, Phillips P, Bryant K, Dooley K, et al. Four-month rifapentine regimens with or without moxifloxacin for tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(18):1705–18.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Imperial M, Nahid P, Phillips P, Davies G, Fielding K, Hanna D, et al. A patient-level pooled analysis of treatment-shortening regimens for drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2018;24(11):1708–15.

Vashakidze S, Kempker J, Jakobia N, Gogishvili S, Nikolaishvili K, Goginashvili L, et al. Pulmonary function and respiratory health after successful treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;82:66–72.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harris RC, Khan MS, Martin LJ, et al. The effect of surgery on the outcome of treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:262.

Malherbe S, Shenai S, Ronacher K, Loxton A, Dolganov G, Kriel M, et al. Persisting positron emission tomography lesion activity and Mycobacterium tuberculosis mRNA after tuberculosis cure. Nat Med. 2016;22(10):1094–100.

Nahid P, Dorman S, Alipanah N, Barry P, Brozek J, Cattamanchi A, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guidelines: treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(7):e147–95.

World Health Organization. The WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis, module 4: treatment—drug-susceptible tuberculosis treatment. Geneva: WHO; 2022.

Google Scholar

Kang M, Kim H, Choi Y, Kim K, Shim Y, Koh W, et al. Surgical treatment for multidrug-resistant and extensive drug-resistant tuberculosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(5):1597–602.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pomerantz B, Cleveland J, Olson H, Pomerantz M. Pulmonary resection for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121(3):448–53.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Somocurcio J, Sotomayor A, Shin S, Portilla S, Valcarcel M, Guerra D, et al. Surgery for patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: report of 121 cases receiving community-based treatment in Lima, Peru. Thorax. 2007;62(5):416–21.

Dravniece G, Cain K, Holtz T, Riekstina V, Leimane V, Zaleskis R. Adjunctive resectional lung surgery for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(1):180–3.

Wang H, Lin H, Jiang G. Pulmonary resection in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a retrospective study of 56 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(5):1640–5.

Lange C, Aarnoutse R, Chesov D, van Crevel R, Gillespie S, Grobbel H, et al. Perspective for precision medicine for tuberculosis. Front Immunol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.566608 .

Urbanowski M, Ordonez A, Ruiz-Bedoya C, Jain S, Bishai W. Cavitary tuberculosis: the gateway of disease transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):e117–28.

Zafar M, Chen L, Xiaofeng Y, Gao F. Impact of diabetes mellitus on radiological presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis in otherwise non-immunocompromised patients: a systematic review. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2019;15(6):543–54.

Sinha P, Bhargava A, Carwile M, Cintron C, Cegielski J, Lönnroth K, et al. Undernutrition can no longer be an afterthought for global efforts to eliminate TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022;26(6):477–80.

Cegielski J, Dalton T, Yagui M, Wattanaamornkiet W, Volchenkov G, Via L, et al. Extensive drug resistance acquired during treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(8):1049–63.

Gao J, Ma Y, Du J, Zhu G, Tan S, Fu Y, et al. Later emergence of acquired drug resistance and its effect on treatment outcome in patients treated with Standard Short-Course Chemotherapy for tuberculosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-016-0187-3 .

Shin S, Keshavjee S, Gelmanova I, Atwood S, Franke M, Mishustin S, et al. Development of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis during multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(3):426–32.

Kempker R, Kipiani M, Mirtskhulava V, Tukvadze N, Magee M, Blumberg H. Acquired drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and poor outcomes among patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(6):992–1001.

Wells G, Glasgow J, Nargan K, Lumamba K, Madansein R, Maharaj K, et al. Micro-computed tomography analysis of the human tuberculous lung reveals remarkable heterogeneity in three-dimensional granuloma morphology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(5):583–95.

Marakalala M, Raju R, Sharma K, Zhang Y, Eugenin E, Prideaux B, et al. Inflammatory signaling in human tuberculosis granulomas is spatially organized. Nat Med. 2016;22(5):531–8.

McCaffrey E, Donato M, Keren L, Chen Z, Delmastro A, Fitzpatrick M, et al. The immunoregulatory landscape of human tuberculosis granulomas. Nat Immunol. 2022;23(2):318–29.

Gern B, Adams K, Plumlee C, Stoltzfus C, Shehata L, Moguche A, et al. TGFβ restricts expansion, survival, and function of T cells within the tuberculous granuloma. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(4):594-606.e6.

Gautam U, Foreman T, Bucsan A, Veatch A, Alvarez X, Adekambi T, et al. In vivo inhibition of tryptophan catabolism reorganizes the tuberculoma and augments immune-mediated control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711373114 .

Wallis R, Ginindza S, Beattie T, Arjun N, Likoti M, Edward V, et al. Adjunctive host-directed therapies for pulmonary tuberculosis: a prospective, open-label, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(8):897–908.

Kaplan G, Post F, Moreira A, Wainwright H, Kreiswirth B, Tanverdi M, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth at the cavity surface: a microenvironment with failed immunity. Infect Immun. 2003;71(12):7099–108.

Fattorini L, Piccaro G, Mustazzolu A, Giannoni F. Targeting dormant bacilli to fight tuberculosis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013;5(1):e2013072.

Moreno-Molina M, Shubladze N, Khurtsilava I, Avaliani Z, Bablishvili N, Torres-Puente M, et al. Genomic analyses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from human lung resections reveal a high frequency of polyclonal infections. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2716.

Dheda K, Lenders L, Magombedze G, Srivastava S, Raj P, Arning E, et al. Drug-penetration gradients associated with acquired drug resistance in patients with tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(9):1208–19.

Prideaux B, Via L, Zimmerman M, Eum S, Sarathy J, O’Brien P, et al. The association between sterilizing activity and drug distribution into tuberculosis lesions. Nat Med. 2015;21(10):1223–7.

Strydom N, Gupta S, Fox W, Via L, Bang H, Lee M, et al. Tuberculosis drugs’ distribution and emergence of resistance in patient’s lung lesions: a mechanistic model and tool for regimen and dose optimization. PLoS Med. 2019;16(4): e1002773.

Chen R, Via L, Dodd L, Walzl G, Malherbe S, Loxton A, et al. Using biomarkers to predict TB treatment duration (predict TB): a prospective, randomized, noninferiority, treatment shortening clinical trial. Gates Open Res. 2017;1:9.

Bartelink I, Zhang N, Keizer R, Strydom N, Converse P, Dooley K, et al. New paradigm for translational modeling to predict long-term tuberculosis treatment response. Clin Transl Sci. 2017;10(5):366–79.

Pasipanodya J, Srivastava S, Gumbo T. Meta-analysis of clinical studies supports the pharmacokinetic variability hypothesis for acquired drug resistance and failure of antituberculosis therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(2):169–77.

Colangeli R, Jedrey H, Kim S, Connell R, Ma S, Chippada Venkata U, et al. Bacterial factors that predict relapse after tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(9):823–33.

Alffenaar J, Stocker S, Forsman L, Garcia-Prats A, Heysell S, Aarnoutse R, et al. Clinical standards for the dosing and management of TB drugs. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022;26(6):483–99.

Marrone M, Venkataramanan V, Goodman M, Hill A, Jereb J, Mase S. Surgical interventions for drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis [review article]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(1):6–16.

Fox G, Mitnick C, Benedetti A, Chan E, Becerra M, Chiang C, et al. Surgery as an adjunctive treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: an individual patient data metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(7):887–95.

Word Health Organization Europe. The role of surgery in the treatment of pulmonary TB and multidrug and extensively drug-resistant TB. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2014.

Vashakidze SA, Gogishvili SG, Nikolaishvili KG, et al. Adjunctive surgery versus medical treatment among patients with cavitary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;60(6):1279–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezab337 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the physicians, nurses, and staff at the NCTLD in Tbilisi, Georgia, who provided care for the patient described in this report. Additionally, the authors are thankful for the patient with pulmonary tuberculosis who was willing to have their course of illness presented and help contribute meaningful data that may help future patients with the same illness.

This study did not receive any specific funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Thoracic Surgery Department, National Center for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, 50 Maruashvili, 0101, Tbilisi, Georgia

Sergo A. Vashakidze, Merab Japaridze, Giorgi Gogishvili & Manana Rekhviashvili

The University of Georgia, Tbilisi, Georgia

Sergo A. Vashakidze

Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi, Georgia

Abivarma Chandrakumaran

Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

Jeffrey M. Collins & Russell R. Kempker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SAV: Conceptualization; Data collection and interpretation; Scientific Writing including initial draft preparation and manuscript revision and editing. AC: Data interpretation; Table and Figure preparation; Literature review; Scientific Writing including initial draft preparation and manuscript revision and editing. MJ: Data collection; Scientific Writing including manuscript review and editing. GG: Data collection; Scientific Writing including manuscript review and editing. JMC: Data interpretation; Scientific Writing including manuscript review and editing. MR: Data interpretation; Scientific Writing including manuscript review and editing. RRK: Conceptualization; Literature review; Scientific Writing including manuscript review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sergo A. Vashakidze .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The authors confirm that written informed consent has been obtained from the patient involved in the case report. Ethics approval is not needed for case reports according to our institutional (National Center for Tuberculosis and Lung Disease) review board.

Consent for publication

The authors confirm that written consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Vashakidze, S.A., Chandrakumaran, A., Japaridze, M. et al. A case report of persistent drug-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis after treatment completion. BMC Infect Dis 22 , 864 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07836-y

Download citation

Received : 08 August 2022

Accepted : 02 November 2022

Published : 19 November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07836-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Thoracic surgery

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

34: Tuberculosis

David Cluck

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Patient presentation.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Chief Complaint

“I have a cough that won’t go away.”

History of Present Illness

A 63-year-old male presents to the emergency department with complaints of cough/shortness of breath which he attributes to a “nagging cold.” He states he fears this may be something worse after experiencing hemoptysis for the past 3 days. He also admits to waking up in the middle of the night “drenched in sweat” for the past few weeks. When asked, the patient denies ever having a positive PPD and was last screened “several years ago.” His chart indicates he was in the emergency department last week with similar symptoms and was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia and discharged with azithromycin.

Past Medical History

Hypertension, dyslipidemia, COPD, atrial fibrillation, generalized anxiety disorder

Surgical History

Appendectomy at age 18

Family History

Father passed away from a myocardial infarction 4 years ago; mother had type 2 DM and passed away from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

Social History

Retired geologist recently moved from India to live with his son who is currently in medical school in upstate New York. Smoked ½ ppd × 40 years and drinks 6 to 8 beers per day, recently admits to drinking ½ pint of vodka “every few days” since the passing of his wife 6 months ago.

Sulfa (hives); penicillin (nausea/vomiting); shellfish (itching)

Home Medications

Albuterol metered-dose-inhaler 2 puffs q4h PRN shortness of breath

Aspirin 81 mg PO daily

Atorvastatin 40 mg PO daily

Budesonide/formoterol 160 mcg/4.5 mcg 2 inhalations BID

Clonazepam 0.5 mg PO three times daily PRN anxiety

Lisinopril 20 mg PO daily

Metoprolol succinate 100 mg PO daily

Tiotropium 2 inhalations once daily

Venlafaxine 150 mg PO daily

Warfarin 7.5 mg PO daily

Physical Examination

Vital signs.

Temp 100.8°F, P 96, RR 24 breaths per minute, BP 150/84 mm Hg, pO 2 92%, Ht 5′10″, Wt 56.4 kg

Slightly disheveled male in mild-to-moderate distress

Normocephalic, atraumatic, PERRLA, EOMI, pale/dry mucous membranes and conjunctiva, poor dentition

Bronchial breath sounds in RUL

Cardiovascular

NSR, no m/r/g

Soft, non-distended, non-tender, (+) bowel sounds

Genitourinary

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Case Report: Pulmonary tuberculosis and raised transaminases without pre-existing liver disease- Do we need to modify the antitubercular therapy?

Sanjeev Gautam Roles: Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation Keshav Raj Sigdel Roles: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing Sudeep Adhikari Roles: Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Buddha Basnyat Roles: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing Buddhi Paudyal Roles: Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing Jiwan Poudel Roles: Writing – Review & Editing Ujjwol Risal Roles: Writing – Review & Editing

This article is included in the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit (OUCRU) gateway.

tuberculosis, transaminitis, standard ATT, liver friendly regimen

Revised Amendments from Version 1

The changes have been made in the revised manuscript as suggested by the reviewers. The concerns of reviewers regarding limited workup of the patient for liver disease has been addressed in the manuscript. This is a single case report and further studies are required to make a firm recommendation for management of pulmonary tuberculosis with transaminitis without pre-existing liver disease. We have acknowledged the fact in the revised manuscript.

See the authors' detailed response to the review by Vivek Neelakantan See the authors' detailed response to the review by Neesha Rockwood See the authors' detailed response to the review by Prajowl Shrestha and Ashesh Dhungana

Tuberculosis is the biggest infectious disease killer in the world 1 , and is endemic in Nepal with the national prevalence at 416 cases per 100000 population 2 . Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most common form. In Nepal, tuberculosis prevalence is more in productive age group (25–64 years) and men. Poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding, immunocompromised state like HIV infection, alcohol, smoking, air pollution, diabetes and other comorbidities are important risk factors for acquiring the disease 3 . Though under-reported, involvement of liver with tuberculosis is encountered often in clinical practice in endemic areas like Nepal.Liver can be involved; a) diffusely as a part of disseminated miliary tuberculosis or as primary miliary tuberculosis of liver, or b) focal involvement as hepatic tuberculoma or abscess, as was classified by Reed in 1990 4 . The biochemical pattern of liver function abnormality in these forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is cholestatic (predominantly raised alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase) rather than hepatocellular (predominantly raised transaminases) 5 , 6 . The hepatocellular pattern of liver injury is seen in cases with pre-existing liver disease including hepatotoxic drug use, which are unrelated to tuberculosis 7 , 8 .

As per national protocol of Nepal, any patient with tuberculosis receives combination antitubercular therapy (ATT) including four drugs; Isoniazid (H), Rifampicin (R), Pyrazinamide (Z) and Ethambutol (E) for initial 2 months popularly known as HRZE. This is followed by 4 months of two drugs; HR. Treatment is given under Directly Observed Treatment Short- Course (DOTS) to improve the patient compliance which could otherwise be compromised owing to lower socioeconomic status of patients, longer duration of treatment and side effects 9 . Patients with extrapulmonary hepatic tuberculosis are treated with full dose of standard ATT 5 , 6 . But three out of the four drugs (H, R and Z) are hepatotoxic 7 . So the patients having pre-existing liver disease usually require liver-friendly modified regimens to protect the liver but they may be suboptimal for eradicating underlying tuberculosis 8 . The protocol of Nepal does not warrant baseline investigations except chest X-ray and sputum smear microscopy to be done routinely before prescribing ATT in programmatic setting 9 . However in hospital setting like our case, baseline blood investigations including liver function tests are usually done before starting treatment even in absence of features suggesting liver injury and therapy modified accordingly.

Here we present a case of pulmonary tuberculosis with predominant transaminitis but there was no feature of pre-existing liver disease nor a history of hepatotoxic drug use. The liver injury was attributed to the pulmonary tuberculosis itself, and treated with standard first line ATT which led to resolution of liver function abnormalities.

Case presentation

A 33 year old Newar housewife from Kathmandu, Nepal, with no known comorbidity, presented to Patan Hospital Emergency Department in November, 2019 with a history of cough with occasional sputum production over the previous 20 days and low grade fever for 10 days. There was no history of chest pain, difficulty breathing, headache, vomiting, altered mentation, abdominal pain, yellowish discoloration of eyes, burning urine, hair loss, photosensitivity, joint pain, or rash but she had decreased appetite and weight loss. There was no past history of tuberculosis or jaundice. She did not consume alcohol or any drugs including acetaminophen, aflatoxin or herbal products. Her father-in-law had been diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis five years earlier, but there was no family history of liver disease.

Initial examination showed temperature of 101 o F with pulse of 110 beats/minute and respiratory rate of 26 breaths/minute. There was diffuse fine crepitation on the left side on auscultation of the chest. There was no lymphadenopathy, icterus, peripheral edema or wheezes. Neck veins were not distended. Liver and spleen were not palpable, and abdomen examination was normal.

Laboratory parameters with normal ranges in parenthesis are as follow:

Complete blood count before transfusion: white cell count 7.8 (4–10) × 10 9 /L; neutrophils 80%; lymphocytes 16%; monocytes 4%; red blood cells 3.6 (4.2–5.4) × 10 12 /L; haemoglobin 10.6 (12–15) g/dL; platelets 410 (150–400) × 10 9 /L.

Biochemistry: random blood sugar 126 (65–110) mg/dL; urea 39 (17–45) mg/dL; creatinine 1.1 (0.8–1.3) mg/dL; sodium 138 (135–145) mmol/L and potassium 4 (3.5–5) mmol/L.

Chest X-ray ( Figure 1 ) showed thick walled cavitating lesions in the left upper lobe and patchy infiltrates in left middle and lower zones. There were hyperinflated lung fields with blunting of left costophrenic angle. Sputum smear examination showed 3+ acid fast bacilli. Sputum Gene Xpert was positive for Rifampicin sensitive tubercle bacilli. A diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis was made, and planned for starting ATT.

Figure 1. Chest X-ray showing thick walled cavitating lesions in the left upper lobe and patchy infiltrates in left middle and lower zones.

Liver function test was performed as baseline workup before starting treatment which showed the following results (with normal ranges in parenthesis): bilirubin total 1.1 (0.1–1.2) mg/dL and direct 0.5 (0–0.4) mg/dL; alanine transaminase 308 (5–30) units/L; aspartate transaminase 605 (5–30) units/L; alkaline phosphatase 149 (50–100) IU/L; gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase66 (9–48) units/L. The raised transaminases led us to perform further workup for liver disease. There was no clinical evidence of chronic liver disease or portal hypertension. Liver synthetic functions were as following;albumin 3.5 (3.5–5) g/dL; total protein 6.5 (6–8.3) g/dL; prothrombin time 14 (11–13.5) s. Serologies for HIV, HBsAg, Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Hepatitis A virus (HAV) and Hepatitis E virus (HEV) were nonreactive. Testing for other hepatotropic viruses was not done because of unavailability of the tests. Neurological examinations and the slit lamp examination of eye were normal. Ultrasound of the abdomen showed a normal sized liver with smooth outline and echotexture. However fibroscan, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, abdominal CT scan and liver biopsy were not done due to financial constraints of the patient.

She was admitted to the respiratory isolation unit. At first there was some hesitation in starting the full treatment for her pulmonary tuberculosis because of her liver function tests. But taking into consideration her presentation and laboratory findings, we opted for the full treatment rather than a modified TB regimen. We started standard four drugs ATT based on her weight as per national TB guidelines which included three tablets of HRZE given once daily with each tablet containing 75 mg isoniazid (H), 150 mg rifampicin (R), 400 mg pyrazinamide (Z) and 275 mg ethambutol (E). This led to improvement in her clinical status. She was closely observed for possible worsening of her liver disease due to the hepatotoxic antitubercular drugs. Providentially, at 1 week after starting treatment, she was afebrile and continuing to improve and her liver function test showed a total bilirubin of 0.7 mg/dl, aspartate transaminase of 40 IU/L and alanine transaminase of 62 IU/L.

She was discharged with advice to follow up in 1 month. At 1 month follow up she had no symptoms and therefore no further tests were done. At 2 months, she was still asymptomatic and her sputum smear was negative for acid fast bacilli. Her liver function test showed a total bilirubin of 0.6 mg/dl, aspartate transaminase of 30 IU/L and alanine transaminase of 35 IU/L. She was switched to3 tablets of HR to be taken for 4 months.

Our patient with pulmonary tuberculosis had predominantly raised transaminases (hepatocellular pattern)during the initial presentation, with only modest elevation in alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyltranspeptidase. The workup for liver disease could not be performed completely because of resource limitation. Looking for clinical evidences by history and examination, and performing liver function tests, abdominal ultrasound and serology for common hepatotropic viruses are usually considered sufficient in our limited setup. We perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. There were no clinical features of chronic liver disease or portal hypertension. She had no risk factors for liver disease such as family history, alcohol, drugs, toxins, features suggesting autoimmune or metabolic liver diseases. Her viral hepatitis serologies were negative. Ultrasound also showed normal liver architecture and size.Though incomplete, the initial workup led us to believe that she had no pre-existing liver injury.

Patients with extrapulmonary hepatic tuberculosis as classified by Reed (diffuse or focal)usually present withnonspecific symptoms like abdominal pain, jaundice, fever, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss and hepatomegaly. They havecholestatic pattern of liver function abnormality with normal transaminases, increased protein- albumin gap owing to raised serum globulin. Hepatic imaging with ultrasound or CT scan reveal abnormalities in 76 and 88% cases respectively. Liver biopsy and demonstration of caseating granuloma and mycobacterial culture remain gold standard for diagnosing hepatic tuberculosis 4 – 6 . Following points in our patient precluded making the diagnosis of hepatic tuberculosis; a) absence of abdominal symptoms and hepatomegaly; b) predominantly raised transaminases (hepatocellular pattern) and normal protein- albumin gap; and c) normal ultrasound finding (though CT and biopsy were not done).

There is another classification schema, given by Levine in 1990 which has incorporated additional entity under hepatic tuberculosis which is ‘pulmonary tuberculosis withliver involvement’ 10 . In the absence of obvious pre-existing liver disease or drug and the presence of active cavitary tuberculosis in lungs, we attributed the transaminitisin our patient to the pulmonary tuberculosis itself. In our anecdotal experience, we have found many such patients though we do not have any formal data to back this up. They are often managed with modified liver-friendly antitubercular regimens for fear of increasing the hepatotoxicity and causing acute liver failure with the use of standard regimen. Few case reports are available in literature reporting the use of the modified regimens 11 , 12 . We believe such cases are underreported, and firm guidelines have not been established to guide clinicians in these cases. Given this, many clinicians in low-middle income countries, including Nepal, who have been treating tuberculosis patients tend to be skeptical in using full doses of first line ATT in such patients and tend to use a modified regimen. However, this practice may potentially lead to under-treatment and therefore increase fatality 13 . The use of modified regimen may also increase the risk of developing drug-resistant tuberculosis because of exclusion of more potent drugs 14 . Though there was some hesitation at first in our case, we soon started treatment with the standard ATT in our patient with close monitoring. This we believe led to the resolution of liver injury, evidenced by the normalization of transaminases.

However, acknowledging that the patient may develop drug induced liver injury (DILI) with the hepatotoxic antitubercular drugs, we should monitorsuch patients closely in an inpatient basis to look forclinical deterioration or any feature suggesting liver failureand liver function test repeated regularly. Though there is no firm recommendation for when to repeat the tests, patient should not be discharged till there is significant improvement in the transaminases level. The close monitoring is important in those with higher risks for developing DILI associated with ATT such as elderly, females, alcohol consumers, the malnourished and those with genetic susceptibility like slow acetylators 7 . Such monitoring is even more important in our setup because there are possibilities of missing occult hepatic diseases owing tolimited workup.Our patient had improving transaminases evidenced till 2 months follow up.

Though limited by incomplete investigations, we concluded pulmonary tuberculosis as the cause for transaminitis in our patient, and the normalization of transaminases after starting the standard dose of ATT further supports this conclusion. We believe pulmonary TB presenting with transaminitis is a common problem and that treatment may often be compromised because of decreased dosing of ATT.We further aim to perform case series study to explore the magnitude of problem and reach specific conclusions.

When treating a tuberculosis patient with transaminitis, it is important to look for any possibility of pre-existing liver disease or drug use. If none is found, then the use of standard ATT from the beginning with close inpatient monitoring of the patient may be essential for optimal management of tuberculosis, and this may help resolve any liver injury caused by the tuberculosis. This is a single case report, so further case series or cohort studies would be helpful to reach some conclusion and provide concrete recommendations.

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

Data availability

Underlying data.

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

- 1. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis . .

- 2. https://nepalntp.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NEPAL-NATIONAL-TB-PREVALENCE-SURVEY-BRIEF-March-24-2020.pdf . .

- 3. https://nepalntp.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NTP-Annual-Report-2075-76-2018-19.pdf .

- 4. Reed DH, Nash AF, Valabhji P: Radiological diagnosis and management of a solitary tuberculous hepatic abscess. Br J Radiol. 1990; 63 (755): 902–4. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 5. Hickey AJ, Gounder L, Moosa MY, et al. : A systematic review of hepatic tuberculosis with considerations in human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2015; 15 : 209. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 6. Wu Z, Wang WL, Zhu Y, et al. : Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic tuberculosis: report of five cases and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2013; 6 (9): 845–50. PubMed Abstract | Free Full Text

- 7. Ramappa V, Aithal GP: Hepatotoxicity related to anti-tuberculosis drugs: mechanisms and management. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013; 3 (1): 37–49. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 8. Sonika U, Kar P: Tuberculosis and liver disease: management issues. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012; 33 (2): 102–6. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 9. https://nepalntp.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National-Tuberculosis-Management-Guidelines-2019_Nepal.pdf . .

- 10. Levine C: Primary macronodular hepatic tuberculosis: US and CT appearances. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990; 15 (4): 307–9. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- 11. Sanchez-Codez M, Hunt WG, Watson J, et al. : Hepatitis in children with tuberculosis: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Pulm Med. 2020; 20 (1): 173. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 12. Shastri M, Kausadikar S, Jariwala J, et al. : Isolated hepatic tuberculosis: An uncommon presentation of a common culprit. Australas Med J. 2014; 7 (6): 247–50. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- 13. Essop AR, Posen JA, Hodkinson JH, et al. : Tuberculosis hepatitis: a clinical review of 96 cases. Q J Med. 1984; 53 (212): 465–77. PubMed Abstract

- 14. Kumar N, Kedarisetty CK, Kumar S, et al. : Antitubercular therapy in patients with cirrhosis: challenges and options. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20 (19): 5760–72. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

Comments on this article Comments (0)

Open peer review.

Competing Interests: No competing interests were disclosed.

Reviewer Expertise: Tuberculosis, Interventional Pulmonology, ILD

- Respond or Comment

- COMMENT ON THIS REPORT

Reviewer Expertise: History of Tuberculosis, Global Health, South and Southeast Asia, Medical Humanities

Is the background of the case’s history and progression described in sufficient detail?

Are enough details provided of any physical examination and diagnostic tests, treatment given and outcomes?

Is sufficient discussion included of the importance of the findings and their relevance to future understanding of disease processes, diagnosis or treatment?

Is the case presented with sufficient detail to be useful for other practitioners?

Reviewer Expertise: Management of HIV/tuberculosis; PK/PD for tuberculosis

- Author Response 16 Oct 2020 Sudeep Adhikari , Internal Medicine, Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Lalitpur, Nepal 16 Oct 2020 Author Response We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. The title needs to convey that ... Continue reading We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. The title needs to convey that this is new onset transaminitis attributed to tuberculosis prior to commencement of anti tubercular therapy Response: Title has been modified. Thank you Background Please outline the baseline work up for TB in programmatic setting in Nepal. Do all patients have baseline LFTs done? Response: Programmatic setting does not require any baseline workup except sputum smear and in chest Xray. But in hospital setting, we perform baseline blood investigations like blood counts, renal function, electrolytes and liver function tests before starting treatment, so that treatment can be modified accordingly. Changes have been made in the background section. Case presentation Has this patient had normal LFTs recorded prior to current TB presentation? Response: No prior LFT testing was done by the patient Mention drug history incl. paracetamol, aflatoxin exposure, family history of liver disease. Text has been modified to state the fact. Thank you The liver screen is incomplete - e.g. autoimmune and inherited liver disease, paracetamol levels, ferritin, occult hep B. Also liver fibrosis assessment. Baseline GGT and clotting needs to be given. Please give a table of ALT, AST, GGT, Alk phos, Albumin and clotting during first 2 weeks of treatment (and any further tests during 6 months of treatment) Of note, there is no clear evidence of disseminated miliary TB on CXR. Abdominal or liver CT was not done. Hence, no comment can be made regarding liver/splenic micronodular abscesses. It appears no mycobacterial blood cultures were taken to assess for bacteraemia. Nor was a liver biopsy done. All relevant negatives and limitations should be mentioned. Response: The liver disease screen is incomplete as the reviewer pointed out. However, because of resource limitation and financial constraints, it is not usually possible to perform full liver disease screening in Nepal. So we usually opt for limited screen, and rely more on history, physical examination and initial limited investigations. Then we perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. Text has been modified to include investigations and other limitations. When was she discharged? Response: She was discharged after 1 week after becoming afebrile and improvement in transaminases. Considering she was never symptomatic from the point of view of GI/hepatobiliary system, was there no further blood work to monitor LFTs since discharge? Response: LFT was repeated first at 1 week before discharge, then at 2 months follow up after discharge. Discussion: Briefly explain classifications of liver TB e.g. Reed, Alvarez, Levine. The authors do not clearly say what clinical, biochemical, radiological and histopathological presentation would be seen with disseminated TB involving liver. This case does not clearly illustrate steps to confirm a transaminitis secondary disseminated miliary TB. Response: Text has been modified to include further discussion. Thank you The implications of this case report would have greater impact and relevance for practitioners in the context of a case series or retrospective cohort and the authors should consider doing this. Response: Yes we hope further case reports and case series would be published in future, and we look forward to do case series and we have included this notion in the ms. Thank you. Further discussion is needed of considerations such as potentiated toxicity with pharmacogenomic factors e.g. slow acetylators, the need for individualized monitoring e.g. therapeutic drug monitoring. Response: Further discussion has been added. Unfortunately such therapeutic drug monitoring is not widely available in Nepal. How long should these patients have monitoring of their LFTs? Is there are risk of paradoxical reactions? Unlike Drug induced liver injury, there is no specific monitoring protocols for patients described in our case. The monitoring should be done till the deranged tests normalize and patient becomes clinically well. We have not encountered paradoxical reactions so far. We would like to whole-heartedly thank you for spending so much time and effort to improve our manuscript. Here below is the point by point response. The title needs to convey that this is new onset transaminitis attributed to tuberculosis prior to commencement of anti tubercular therapy Response: Title has been modified. Thank you Background Please outline the baseline work up for TB in programmatic setting in Nepal. Do all patients have baseline LFTs done? Response: Programmatic setting does not require any baseline workup except sputum smear and in chest Xray. But in hospital setting, we perform baseline blood investigations like blood counts, renal function, electrolytes and liver function tests before starting treatment, so that treatment can be modified accordingly. Changes have been made in the background section. Case presentation Has this patient had normal LFTs recorded prior to current TB presentation? Response: No prior LFT testing was done by the patient Mention drug history incl. paracetamol, aflatoxin exposure, family history of liver disease. Text has been modified to state the fact. Thank you The liver screen is incomplete - e.g. autoimmune and inherited liver disease, paracetamol levels, ferritin, occult hep B. Also liver fibrosis assessment. Baseline GGT and clotting needs to be given. Please give a table of ALT, AST, GGT, Alk phos, Albumin and clotting during first 2 weeks of treatment (and any further tests during 6 months of treatment) Of note, there is no clear evidence of disseminated miliary TB on CXR. Abdominal or liver CT was not done. Hence, no comment can be made regarding liver/splenic micronodular abscesses. It appears no mycobacterial blood cultures were taken to assess for bacteraemia. Nor was a liver biopsy done. All relevant negatives and limitations should be mentioned. Response: The liver disease screen is incomplete as the reviewer pointed out. However, because of resource limitation and financial constraints, it is not usually possible to perform full liver disease screening in Nepal. So we usually opt for limited screen, and rely more on history, physical examination and initial limited investigations. Then we perform further tests only if the initial workup hints towards another etiology. Text has been modified to include investigations and other limitations. When was she discharged? Response: She was discharged after 1 week after becoming afebrile and improvement in transaminases. Considering she was never symptomatic from the point of view of GI/hepatobiliary system, was there no further blood work to monitor LFTs since discharge? Response: LFT was repeated first at 1 week before discharge, then at 2 months follow up after discharge. Discussion: Briefly explain classifications of liver TB e.g. Reed, Alvarez, Levine. The authors do not clearly say what clinical, biochemical, radiological and histopathological presentation would be seen with disseminated TB involving liver. This case does not clearly illustrate steps to confirm a transaminitis secondary disseminated miliary TB. Response: Text has been modified to include further discussion. Thank you The implications of this case report would have greater impact and relevance for practitioners in the context of a case series or retrospective cohort and the authors should consider doing this. Response: Yes we hope further case reports and case series would be published in future, and we look forward to do case series and we have included this notion in the ms. Thank you. Further discussion is needed of considerations such as potentiated toxicity with pharmacogenomic factors e.g. slow acetylators, the need for individualized monitoring e.g. therapeutic drug monitoring. Response: Further discussion has been added. Unfortunately such therapeutic drug monitoring is not widely available in Nepal. How long should these patients have monitoring of their LFTs? Is there are risk of paradoxical reactions? Unlike Drug induced liver injury, there is no specific monitoring protocols for patients described in our case. The monitoring should be done till the deranged tests normalize and patient becomes clinically well. We have not encountered paradoxical reactions so far. Competing Interests: none Close Report a concern Reply -->

- The authors describe a patient with pulmonary tuberculosis and raised liver enzymes (Transaminases). They do mention that the patient did not have any preexisting liver disease or drug use, but do not mention how they systematically ruled out other causes of tansaminitis (other non A-E viral hepatitis like GBV, Hep G, EBV,TT virus and other tropical infections).

- “In this report, we gave full dose standard antitubercular drugs, and the liver injury resolved evidenced by normalization of transaminases”. The authors should make their message more clear to “presence of transamnitis with no obvious common underlying etiology may not warrant a modification of standard antitubercular regimen”

- Evaluation of patient: Diagnostic work-up is incomplete and should also include evaluation for degree of hepatocellular injury. Prothrombin time is not mentioned, GGT levels not mentioned, Serum globulin levels not mentioned (hepatic TB has inverted albumin to globulin ration), imaging was limited (only USG performed, CT not done), liver biopsy not performed. More investigations should have been performed to rule out underlying chronic liver diseases: Fibroscan, upper GI endoscopy for Portal HTN)

- Figure 1: The quality of the image is suboptimal. The entire bony cage is not visible. Right costophrenic angle is not visible. Finding of hyperinflated lung fields and blunting of left CP angle are not described. Did the patient have underlying obstructive airway disease? If so did she also have pulmonary hypertension?. Could hepatic congestion due to RHF explain the raised liver enzymes?

- Follow up: The patient improved significantly at 1 month follow up. It would be desirable to have a complete follow up of the patient with evaluation of liver enzymes at least once during treatment as patient initially also did not have any liver specific symptoms.

- The authors argue that the patient did not have underlying liver disease or liver involvement due to tuberculosis as there was no features of Granuloma and cholestatic pattern of liver enzyme elevation. To ascribe the transamnitis to be caused by TB would be an arbitrary statement especially in the absence of liver biopsy.

- The authors mention that they have found many patients of pulmonary TB to have predominant transamnitis and without any preexisting liver disease in their experience. Such statement is not backed by any formal data.

- The authors conclude that pulmonary TB was the cause of transamnitis in their patient, not hepatic TB or underlying liver disease. In the absence of complete workup, such strong conclusions should not be made.