ESSAY SAUCE

FOR STUDENTS : ALL THE INGREDIENTS OF A GOOD ESSAY

Essay: Women in leadership

Essay details and download:.

- Subject area(s): Management essays

- Reading time: 6 minutes

- Price: Free download

- Published: 27 October 2015*

- File format: Text

- Words: 1,548 (approx)

- Number of pages: 7 (approx)

Text preview of this essay:

This page of the essay has 1,548 words. Download the full version above.

‘Women in leadership’ is a phenomena that has obtained many attention over the past couple of years. Nowadays more young woman graduate of Universities, yet the amount of female leader seems remarkable low (in 2012 only 16,6%). Many research has been accomplished in order to find out the differences between male and female leadership styles, the challenges women face in organisations, the traits women have to make and the influence of stereotyping on men and women. A significant number of organisations have diverse teams and claim they acknowledge the advantages of female leadership styles and know the positive influence of women in the organisation. Nevertheless, the traditional roles at home, the stereotyping and the ‘boys networking clubs’ seem to make it difficult for women on their way to the top. Even though organisations state they offer equal chances for men and women, women continue to make more traits and face more obstacles due to gender-based assumptions. Women and female leaders still face discrimination in organisations. This essay discusses reasons why women face discrimination, such as the communication style of women, work/family balance, stereotyping and networking based on academic research, statistical data, examples and expert quotes.

First of all women face discrimination, because organisations find a women’s communication style to emotional to be a representative leader. According to von Hippel et al. (2011, 1313) who held research about the stereotyping of women and compared a lot of research reports, state that a women’s communication style is focused on emotional, indirect and elaborate components, while a men’s communication style is instrumental, direct and compact. Another research report of Groysberg and Bell (2013) argues about the gender gap in the CEO-suite, argues that 8% of the women and 11% of the men state women have more interpersonal skills and show more empathy (Gorysberg & Dell 2013, 93). The findings about women their communication style confirm women are seen as less competent than men, because women do not show the male skills such as assertiveness (Eagly & Karau, 2002, Heilman, Wallen, Fuchs, & Tamkins, 2004, 1313).

However, women’s communication style is perceived as ‘better’ than men’s communication style. According to researchers Eberly & Fong (2013, 709) on ‘leading via heart and mind’ leaders need to have the skills to recognize their emotions and the influence of their emotions on their employees. Leaders who are emotionally intelligent are better in identifying emotional needs of a situation (Humprey et al., 2008). The ability of emotionally intelligence leads to managing the emotions of oneself and their employees, can achieve a positive work surrounding and leads to better employee performance and motivation (Eberly & Fong 2013, 709). Furthermore, one respondent in a report of Vecchio (2003, 835) about the gender advantage states the following quote about female leadership: ‘Every study I’m aware of finds that women managers are more effective than men in decision making, analysis, so-called people skills and communications. Women have emotional x-ray vision. And they deliver results.’ -a female marketing consultant (Kleiman, 2003). On the other hand, women have a lack of authority and therefore women are perceived as less competent leaders (Hippel et al. 2011, 1313). As a result women seem less qualified for leadership positions (Hippel et al. 2011, 1313). According to Powell, Butterfield & Parent (2002) Schein (1975, 1313) the masculine characterises such as assertiveness and self-reliance, are seen as indicators for effective leadership style. Although research confirms women’s communication style leads to better performance, research indicates women still seem to suffer under the gender-based advantages of men.

Secondly, women face discrimination because organisations and men assume they put family first under all circumstances. According to Ely, Stone, and Ammerman (2014, 103), who surveyed more than 25,000 HBS graduates to collect data about women in leadership, conclude women and men think women develop more slowly due to the assumption that women find family more important than their career. 77 % of the HBS graduates state choosing family over work is holding women back to make a career (Ely, Stone, Ammerman 2014, 104). Also, more than 75% of the men expects their wife to take care of the children instead of having a career (Ely, Stone, Ammerman 2014, 106). Men still expect women to adjust their career to the traditional roles. Furthermore, more than half of the men finds their career more important than their wives career and think their career deserves more priority (Ely, Stone, Ammerman 2014, 106). Another notable assumption is that women are most of the time not considered for international opportunities (Gorysberg & Dell 2013, 91). For example, directors still assume women find it more difficult than men to leave their family for travelling or relocating due to work(Gorysberg & Dell 2013, 91). This leads to unequal chance for international functions.

On the contrary, women do leave the company due to child care and they start working part-time. According to Ely, Stone & Ammerman (2014, 104) women do leave the company to take care of the children. According to Sheryl Sandberg (CEO Facebook) women give up their career ambitions to have a family. Pip Jamieson, a business consultant and leadership coach, interviewed more than twenty senior female and male leaders about the differences of men and women in business. One of her respondents stated the following about working mothers (Jamieson, 2010, 36): ‘To be quite honest I could never do what I am doing if I had children.’ However, only 11% leaves the company due to fulltime childcare, the rest of the women are simply seeking for other jobs because their current jobs are not fulfilling enough (Ely, Stone & Ammerman 2014, 105). Many women do start working part-time and then never climb up the ladder. This might be true, but that has a reasonable explanation. Organisations still do not offer challenging and professional part-time jobs for working mothers (Ely, Stone & Ammerman 2014, 105). As a result, women have a lack in professional experience and that is why they cannot make it to the top (Ely, Stone & Ammerman 2014, 105). Also according to Sheryl Sandberg and Pip Jamieson, a work-life balance is hard for women. Many women are comparing themselves with fulltime mothers or fulltime workers (Sandberg, 2013). Women are self-critics and are eager to fulfil every role perfectly (Jamieson, 2010, 36). Sandberg states that the responsibilities at home should be balanced, however according to Ely, Stone & Ammerman (2014, 105) men are still traditional about the child care responsibilities. Also, organisations need to offer more family-friends benefits such as flexible working hours and child care for both men and women (Eagly & Carli, 2007, 69-70). The services organisations offer seem not to be sufficient enough to let mothers work.

Thirdly, women face discrimination because they are often shut out in networking events or meetings. According to Gloysberg & Connolly (2013, 71) who interviewed 24 CEO’s about diverse and inclusive organisations, state that seven of the CEOs said that being shut out from networks and conversations leads to less development and promotion of an employee. Men seem to shut out women. For example, Woods Staten (CEO Arcos Dorados, largest operator of McDonald’s), confirms that men ignore women and bond with other men by drinking together and meet up after meetings (Gloysberg & Connolly 2013, 71). According to Barry Salzberg (CEO Deloite) women have to deal with the ‘old boys’ network’: a typical masculine environment when they do fun activities like play golf and where it is difficult for women to fit in meetings (Gloysberg & Connolly 2013, 71).

Women may have the feeling they are excluded, but women do not participate in networking meetings. According to Gregory-Mina (2012, 66) who provided a literature review about gender issues, debates that women are less likely to take part of networking events due to family-work balance. Also women have less success in networking, because they want to use networking for social support and men want to use it for career growth (Gregory-Mina 2012, 69). However, organisations still do not offer enough mentoring opportunities for women. When organisations offer mentoring opportunities and they provide a male mentor, access to networks for women becomes easier (Gregory-Mina 2012, 69). According to Gloysberg & Connolly (2013, 75) organisations can offer sponsoring resource groups or mentoring in order to let women network. Also Sheryl Sandberg (2013, 87) states women should get a mentor in order to motivate women to climb up the ladder and become successful.

In summary, women and female leaders still face discrimination in organisations due to their communication skills, gender-based assumptions and exclusion of networks. A female communication style is the opposite of male communication style and the male communication style tends to be more effective. Another reason why women face discrimination is because of the assumption organisations and men seem to have that women chose family above all. Thirdly, women are excluded of networking opportunities. Yet, the opposites states that the emotional intelligence of women has positive impacts on employees and their productivity. However, women still suffer a lack of authority due to the male communication style. Furthermore women do leave the company to take care of the children. Nevertheless, they want to come back and work on their career, but organisations still do not offer enough family-friends benefits. At last, women leave after networking events which may indicate women do not want to network. On the contrary, they would like to network but they need a mentor that supports them and gives them advice. It is obvious that the prejudices of female behaviour still rule the organisations and the society. Companies should provide mentors to increase the access to networks, directors should embrace the female communication style and organisations should offer family-friend benefits. In that way the gender barriers will overcome and women will get more chances to climb up the ladder.

...(download the rest of the essay above)

About this essay:

If you use part of this page in your own work, you need to provide a citation, as follows:

Essay Sauce, Women in leadership . Available from:<https://www.essaysauce.com/management-essays/essay-women-in-leadership/> [Accessed 26-03-24].

These Management essays have been submitted to us by students in order to help you with your studies.

* This essay may have been previously published on Essay.uk.com at an earlier date.

Essay Categories:

- Accounting essays

- Architecture essays

- Business essays

- Computer science essays

- Criminology essays

- Economics essays

- Education essays

- Engineering essays

- English language essays

- Environmental studies essays

- Essay examples

- Finance essays

- Geography essays

- Health essays

- History essays

- Hospitality and tourism essays

- Human rights essays

- Information technology essays

- International relations

- Leadership essays

- Linguistics essays

- Literature essays

- Management essays

- Marketing essays

- Mathematics essays

- Media essays

- Medicine essays

- Military essays

- Miscellaneous essays

- Music Essays

- Nursing essays

- Philosophy essays

- Photography and arts essays

- Politics essays

- Project management essays

- Psychology essays

- Religious studies and theology essays

- Sample essays

- Science essays

- Social work essays

- Sociology essays

- Sports essays

- Types of essay

- Zoology essays

Privacy Overview

Having women in leadership roles is more important than ever, here's why

Finland's Prime Minister Sanna Marin (second from right), Minister of Education Li Andersson, Minister of Finance Katri Kulmuni and Minister of Interior Maria Ohisalo Image: REUTERS

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Leanne Kemp

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Gender Inequality is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, gender inequality.

- Since 2015 the number of women in senior leadership in business has grown and diversity in leadership is good for business;

- Beyond business, female leaders from across generations are working together to find new solutions to the world's biggest problems;

- The tech sector must attract more women to unlock the potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and ensure technology is developed from a balanced perspective.

In an ideal world, it shouldn’t matter whether there’s a woman running the IMF, Microsoft or the Democratic Party. Does an SME owner or tech start-up care that it’s a woman who makes finance more accessible? If a miner, factory worker or fisherman gets a better share of the profits and can send his or her children to school, are they bothered that a woman made it possible?

Bush fires, burst riverbanks, melting icecaps, fatbergs, plastic islands and species extinction: none of these considers the sex of the perpetrators or decision-makers. Yet, encouraging more women into leadership positions remains critical in our era and given the fast-approaching challenges of the future.

Have you read?

5 ways to break down the barriers for women to access leadership roles, these are the best countries for women to work in, a woman would have to be born in the year 2255 to get equal pay at work.

The overall number of women in top business roles is still painfully low – only 5% of CEOs of major corporations in the US are women – but there are reasons for optimism. Since 2015 the number of women in senior leadership has grown, particularly in the C-suite where the representation of women has increased from 17% to 21% . Today, 44% of companies have three or more women in their C-suite, up from 29% of companies in 2015. Corporate America scores much lower than France or Norway, where businesses average more than 40% female representation on a board of directors .

Diversity in leadership is good for business. For example, a Harvard Business School report on the male-dominated venture capital industry found that “the more similar the investment partners, the lower their investments’ performance”. In fact, firms that increased their proportion of female partner hires by 10% saw, on average, a 1.5% spike in overall fund returns each year and had 9.7% more profitable exits.

Evolving job needs are empowering women and levelling the playing field. The new service economy doesn’t rely on physical strength but skills that come easily to women, such as determination, attention to detail and measured thinking. The female brain is naturally wired for long-term strategic vision and community building.

The emergence of female leaders can become a centrifugal force for good in the world. For the first time, we’re seeing examples of female leaders emerging from across the generations to cross-weave their knowledge and drive for change. If we take the environment and climate as an example, someone as experienced and respected as Jane Goodall is standing alongside teenage activists like Greta Thunberg. Importantly, there are now ambitious and capable women running influential organizations who can activate physical change through technology and policy. The recent progress with the circular economy and blockchain is a prime example.

There’s nothing inherently masculine about blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning; computers are androgynous by nature. That said, the tech sector remains heavily dominated by men. According to the World Economic Forum , the greatest challenge preventing the economic gender gap from closing is women’s under-representation in emerging roles. In cloud computing, just 12% of professionals are women; in engineering and Data and AI, the numbers are 15% and 26% respectively. Unless the sector can balance the ledger by making roles attractive to women, then we risk missing out on the full potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Organizations need to ensure there are sufficient rungs on the ladder to help women climb into management positions. We need to be open-minded enough to bring in female leaders from other industries, who don’t have a tech background. We need to work closely with schools and universities to win the argument that tech isn’t just a male career path. Technology also has a role to play – and responsibility – in promoting diversity in the workplace, given its ability to change working relationships, encourage transparency and connect people around the world. In a period of constant flux, organizations that prioritize a diverse and inclusive culture will be better placed to solve the problems of the future.

Research by Deloitte suggests companies with an inclusive culture are six times more likely to be innovative. By staying ahead of changes, they are twice as likely to hit or better financial targets. This means providing female mentors and role models, demonstrating trust (rather than talking about it), creating an environment that encourages collaboration, using technology to break barriers and sourcing innovation openly.

Women can lead our sector forward too. Now that technology is all-pervasive, the traditional sector lines have become blurred. Brands that cling to the old structures will find themselves overtaken and left behind. This is when women’s ability to empathize and seek compromise becomes a powerful asset. If technology is supposed to service the whole of humanity, the big decisions need to be taken from a balanced perspective.

More women are now being elected to legislatures across the world: women hold 25.2% of parliamentary lower-house seats and 21.2% of ministerial positions, compared to 24.1% and 19% respectively last year. While there is a long way to go, improving political empowerment for women typically corresponds with increased numbers of women in senior roles in the labour market.

In my own Queensland, a women-led government is taking big steps forward on behalf of the state economy. They’ve shown a real desire to listen to experts in the wider world of business. We’re seeing women from other fields, such as ex-Olympic athletes, joining the political arena. Yet, for those countries and political parties – and corporations for that matter – which have never appointed a woman to the top position, the suspicion that the system isn’t fair and that the glass ceilings are unbreakable grows with every election.

The survival of the planet requires new thinking and strategies. We are in a pitched battle between the present array of resources and attitudes and the future struggling to be born. Women get it; young people get it. They are creating a whole different mindset.

Ultimately, the problems we face are not technological, but human – the human system is broken. People should always be appointed on merit and the electorate must decide, but more still needs to be done to give all women the best possible chance of rising to the top. If that happens, then I’ll be the first to say that who’s in charge doesn’t matter a jot.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Gender Inequality .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

In the age of the ‘manosphere,’ what’s the future for feminism? With Jude Kelly of the WOW Festival

Robin Pomeroy and Sophia Akram

March 28, 2024

Fintech is growing fast. Here are 3 groups who are benefiting

Women inventors make gains, but gender gaps remain

Victoria Masterson

March 19, 2024

Paris to host the first-ever gender-equal Olympics

Access to financial services can transform women’s lives – an expert explains how

Kateryna Gordichuk and Kate Whiting

March 18, 2024

Access to financial services can transform women's lives. Here's how

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Are Women Better Leaders than Men?

- Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman

We’ve all heard the claims, the theories, and the speculation about the ways leadership styles vary between women and men. Our latest survey data puts some hard numbers into the mix. Our data come from 360 evaluations, so what they are tracking is the judgment of a leader’s peers, bosses, and direct reports. We ask […]

We’ve all heard the claims, the theories, and the speculation about the ways leadership styles vary between women and men. Our latest survey data puts some hard numbers into the mix.

- JZ Jack Zenger is the CEO and Joseph Folkman is the president of Zenger/Folkman, a leadership development consultancy. They are co-authors of the October 2011 HBR article “ Making Yourself Indispensable ,” and the book How to Be Exceptional: Drive Leadership Success by Magnifying Your Strengths (McGraw-Hill, 2012).

Partner Center

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Chapter 2: what makes a good leader, and does gender matter.

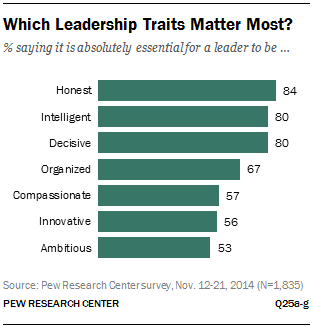

Roughly two-thirds of adults (67%) say that being organized is an essential quality in a leader. Somewhat smaller shares of the public say that being compassionate (57%), innovative (56%) or ambitious (53%) are essential for leadership.

Larger gender gaps emerge on some of the other, less important traits. Women are much more likely than men to say that being compassionate is absolutely essential in a leader: 66% of women say this, compared with 47% of men. Women also place a higher value on innovation than men do. Some 61% of women consider this trait to be absolutely essential in a leader, compared with 51% of men.

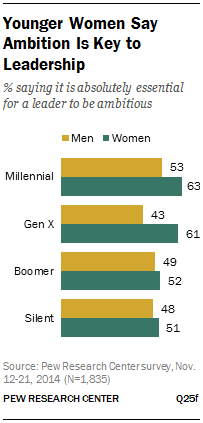

In addition, women are more likely than men to say that ambition is an essential trait for a leader (57% of women and 48% of men say this is absolutely essential). This overall gender gap is driven by the younger generations—Millennials and Gen Xers. Fully 63% of Millennial women and 61% of Gen X women consider ambition an essential leadership trait, compared with 53% of Millennial men and only 43% of Gen X men.

Who Has the Right Stuff to Lead—Men or Women?

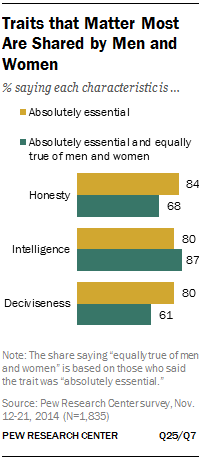

The public sees little distinction between men and women on several of these leadership traits. Large majorities say that when it comes to intelligence and innovation, men and women display those qualities equally. And solid majorities see no gender differences in ambition, honesty and decisiveness.

The public is also much more likely to see women as being more organized than men, rather than vice versa. Fully 48% say being organized is more true of women than men, while only 4% say this quality is found more in men than women (46% say it’s true of both).

Women also have an advantage over men when it comes to honesty—one of the most crucial leadership traits, according to the public. Some 29% of all adults associate honesty more with women than men, while 3% say honesty applies more to men than women. A majority of adults (67%) say this characteristic is displayed equally by men and women.

While solid majorities of the public see no difference between men and women on decisiveness and ambition, among those who do draw a distinction on these traits, men have an edge over women. Some 27% of adults say that men are more decisive than women, while only 9% see women as more decisive than men. About six-in-ten (62%) say men and women are equally decisive. Similarly, while 21% of the public says men are more ambitious than women, half as many (9%) say women are more ambitious than men. (A 68% majority see no gender difference on this trait.)

Two additional leadership traits are clearly a gender tossup in the public’s mind. More than eight-in-ten adults (86%) say intelligence is equally descriptive of men and women. An additional 9% say women are more intelligent than men, and 4% say the opposite. Fully three-quarters of adults say men and women are equally innovative. Those who see a difference on this characteristic are evenly split over which gender has an advantage: 11% say innovation better describes women, and 12% say it’s more true of men.

Public Sees Few Gender Differences on “Essential Traits”

For example, among those who say honesty is an essential quality for a leader to have, 68% say that men and women are equally honest (among all adults 67% say the same). And for those who say intelligence is an essential trait for a leader, 87% say this trait is found equally in men and women (compared with 86% among all adults). The same can be said of decisiveness. Among those who say this is an essential leadership trait, 61% say men and women display this trait equally (compared with 62% among all adults).

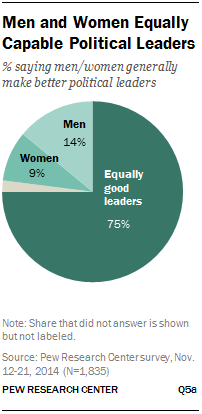

Gender and Political Leadership

Views on gender and political leadership are remarkably stable across major demographic groups. Men are slightly more likely than women to say that men make better political leaders (17% vs. 12%), and women are more likely than men to say women make better leaders (11% vs. 7%). But strong majorities of both groups say men and women make equally good political leaders.

There is broad agreement across generations as well, although Gen Xers are somewhat less likely than younger or older generations to say that women make better leaders than men. There are no major differences across racial or socio-economic groups on this question.

When gender and partisanship are both taken into account, the differences become sharper. Among Republican men, 27% say that men make better political leaders than women. Only 1% of Republican men say that women make better leaders than men. Republican women also lean toward men, though less heavily so: 17% say that men make better political leaders than women, while 4% say women make better leaders than men.

The gender gap is smaller among Democrats. Equal shares of Democratic men and women say that women make better political leaders than men (16%). Among Democratic men, 11% say men make better political leaders than women. Some 8% of Democratic women say the same.

Executive vs. Legislative Leadership

In elected office, women tend to be more heavily represented in the legislative branches of government than in the executive branches, but the public doesn’t draw sharp distinctions in terms of where women can do the best job. Only 10% say women are better at legislative jobs like serving on the city council or in Congress, and 7% say women are better at executive jobs such as mayor or governor. The vast majority (82%) say there is no difference, suggesting that women can serve equally well in either type of position.

A similarly large majority of adults (83%) don’t see any difference in men’s capability to carry out executive vs. legislatives jobs in government. About one-in-ten adults (11%) say men are better at executive jobs, and 5% say men are better at legislative jobs. Men and women agree that executive and legislative jobs are not better suited for one gender than the other.

The Tools of the Trade

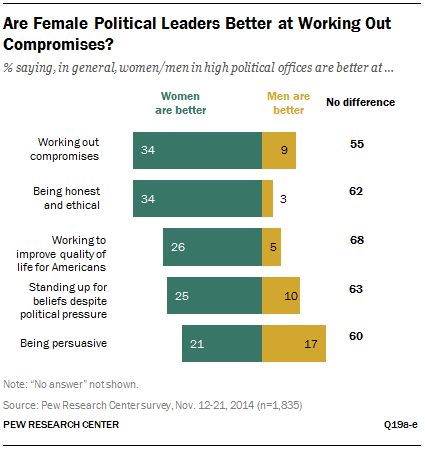

While most Americans think, in general terms, men and women make equally good political leaders, many do see gender differences in style and substance.

Women also have an advantage over men on honesty and ethical behavior. A majority of all adults (62%) say men and women don’t differ in this regard. One-third (34%) say women in top political positions are more honest and ethical than men in top political positions. Just 3% say men are more honest and ethical.

Most adults (68%) say political leaders are equally good at working to improve the quality of life for Americans regardless of their gender. But many do see a gender difference: 26% say women in top political positions are better at this than their male counterparts, while 5% say men are better at this than women.

Similarly, women have an edge over men when it comes to standing up for what they believe in, despite political pressure. While most adults (63%) say men and women serving in high-level political offices are about equal in this regard, 25% say female political leaders are better at doing this, and 10% say men are better.

Opinion is more evenly divided on which gender is more persuasive. Overall, 60% of adults say there is no difference between male and female political leaders in their ability to be persuasive. Beyond that, only a slightly higher share say women are better at this (21%) than say men are better (17%).

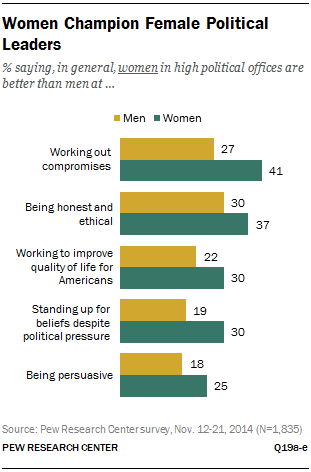

Women See Clear Advantages to Female Political Leadership

Women are also significantly more likely than men to say that in politics female leaders have an advantage over male leaders in terms of standing up for what they believe in, despite political pressure. Three-in-ten women say female leaders are better at doing this; only 19% of men agree. There are significant gender gaps on the three additional items tested in the poll: being honest and ethical, working to improve the quality of life for Americans and being persuasive. In each case more women than men say that female political leaders do a better job.

Interestingly, while men are somewhat more likely than women to say that male political leaders excel in several of these areas, in most cases, even men give female leaders at least a slight edge.

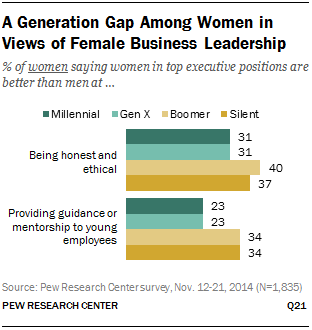

There is a generational divide in views of men, women and political leadership. Baby Boomers and members of the Silent generation tend to have more a positive view of female leaders than do their younger counterparts. And because the gender gap on these issues is much wider among older adults, the generational differences are driven almost entirely by women.

About half of women from the Baby Boom (47%) and Silent generations (50%) say that women in high political office are better than men at working out compromises. By comparison, 33% of Millennial women and 37% of Gen X women say the same. Similarly, 39% of Boomer women and 35% of Silent women say that female leaders are better than their male counterparts at working to improve the quality of life for Americans. Younger generations of women are less likely to hold this view (22% of Millennial women and 24% of Gen X women).

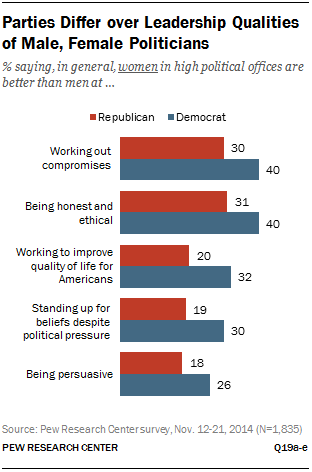

Democrats More Enthusiastic about Female Political Leaders

For example, while 40% of Democrats say female political leaders are better than male leaders at working out compromises, only 30% of Republicans agree. Relatively few Republicans (10%) say men are better at working out compromises, but a majority (58%) say there isn’t any difference between men and women in this regard.

When it comes to standing up for what they believe in, despite political pressure, three-in-ten Democrats say female political leaders are better at this than male leaders. Only 19% of Republicans agree that women are better than men in this area. Some 67% of Republicans, compared with 59% of Democrats, say men and women are equally able in this regard.

Democratic women are among the most enthusiastic proponents of female political leaders. In most cases, they are more likely than both Democratic men and Republican women to say that female political leaders do a better job than men. This is true for working out compromises, working to improve the quality of life for Americans, standing up for what they believe in and being persuasive.

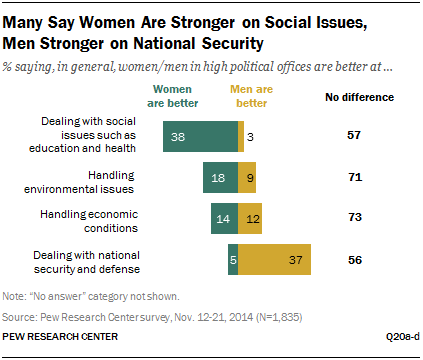

Political Leadership and Policy Expertise

Just as the public views men and women as equally capable on various leadership traits and characteristics, majorities see little difference between male and female political leaders in some major policy realms.

Environmental policy is another area where the public sees little difference between male and female political leaders: 71% say when it comes to handling environmental issues, men and women perform about equally well. Roughly one-in-five (18%) say women in high political offices are better at handling this issue; half as many say men do a better job in this area.

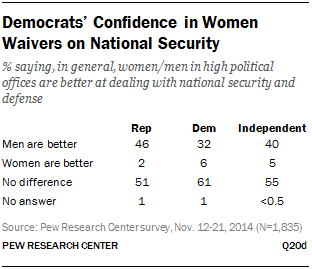

Bigger differences emerge on two additional policy areas—social issues and national security. Narrow majorities say men and women in high political office are equally capable in these areas: 57% for social issues and 56% for national security. But nearly four-in-ten have a clear gender preference in each of these issue areas. Some 38% say women in high political office do a better job than men dealing with social issues such as education and health care. Only 3% say men do a better job in this area.

The gender gaps in perceptions about male and female leaders are not as pronounced on these policy issues as they are for traits and attributes. Women are more likely than men to say that female political leaders are better at dealing with social issues such as education and health care, and they are somewhat more likely to say that female leaders are better at handling economic conditions. Very few women (5%) say that female leaders do a better job than their male counterparts in dealing with national security. A majority of women (59%) say that there isn’t any difference between male and female leaders in this policy area (54% of men say the same).

Gender and the C-Suite

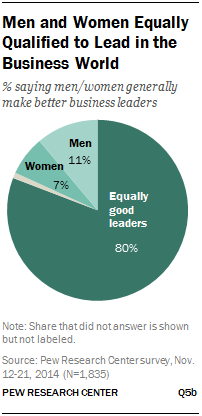

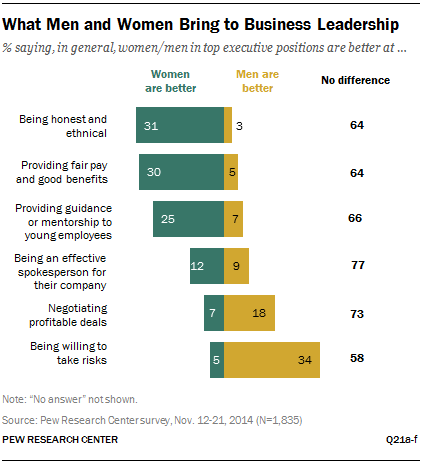

Looking at some of the specific attributes required to be successful in business, again, the public sees relatively few differences between men and women. Strong majorities say there is no difference between men and women when it comes to being an effective spokesperson for their company (77% see no difference) and negotiating profitable deals (73%). And solid majorities see no difference between men and women on providing guidance or mentorship to young employees (66%), providing fair pay and good benefits (64%), being honest and ethical (64%) and being willing to take risks (58%).

Among those who do draw distinctions between men and women on these leadership attributes, some clear gender patterns emerge. About three-in-ten adults (31%) say women in top executive positions are more honest and ethical than men; only 3% say men are better in this regard. Similarly, 30% say women do a better job at providing fair pay and good benefits, while 5% say the same about men. Women are also perceived to have an advantage in providing guidance or mentorship to young employees: 25% say women are better at this, while 7% say men are better.

The largest gap in favor of men is on the willingness to take risks. Some 34% of the public says men in top executive positions are better at this than women; only 5% say women are better than men. Men are also seen as having an edge in negotiating profitable deals. About one-in-five adults (18%) say men in top business positions are better at this than women, while 7% say women are better at this.

Neither men nor women are seen as having a clear advantage in serving as spokespeople for their companies: 9% say men are better at this, 12% say women are better and 77% see no difference between the two.

Men are more likely than women to say that male leaders in business are more willing to take risks (37% of men say this, compared with 31% of women). In addition, men are more likely than women to say there is no gender difference when it comes to being honest and ethical and providing fair pay and good benefits.

Opinions on gender and business leadership also differ across partisan lines. Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say that women do a better job on many of the characteristics tested in the poll, although in most cases majorities from each party say there is no difference between men and women on these dimensions.

Some of the largest partisan gaps can be seen on which gender does a better job of being honest and ethical (37% of Democrats say women, 29% of Republicans say the same), providing fair pay and good benefits (37% of Democrats say women, 24% of Republicans say the same), and being willing to take risks (44% of Republicans say men, 30% of Democrats say the same).

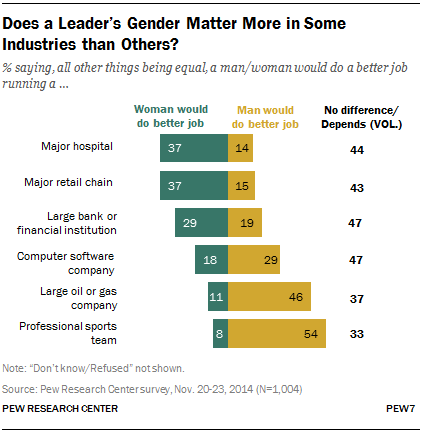

Gender Stereotypes and Business Industries

The share saying a man would do a better job running a computer software company is higher than the share saying a woman would do a better job at this. Some 47% don’t see a difference between men and women in their ability to run a software company or say it depends.

Women have an edge over men in hospital management and in retail. Among all adults, 37% say a woman would do a better job of running a major hospital, while 14% say a man would do a better job at this. A plurality (44%) say gender doesn’t make any difference in running a hospital.

The responses are nearly identical for a major retail chain: 37% say a woman would do a better job running this type of company, 15% say a man would do a better job and 43% say there is no difference or it depends.

Women also have a slight advantage when it comes to running a large bank or financial institution. About three-in-ten adults (29%) say a woman would do a better job running this type of company, and 19% say a man would do a better job. Roughly half (47%) say it would not make any difference.

Men and women tend to agree in their assessments of who could do a better job running companies in each of these industries. In the case of a professional sports team, women are somewhat more likely than men to say that a female leader could do better job (11% vs. 5% of men). However, even among women, half (51%) say a man would do a better job of running a pro sports team.

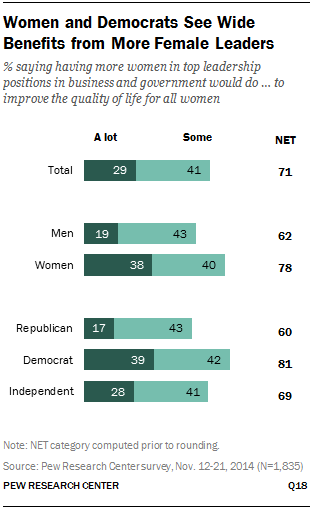

Do Female Leaders Make a Difference?

Women are much more likely than men to see potential benefits in having more female leaders. Fully 38% of women say having more women in top leadership positions would do a lot to improve the lives of all women; only half as many men (19%) agree.

Similarly, Democrats are twice as likely as Republicans to say that more female leaders would be beneficial to all women. About four-in-ten Democrats (39%) say this would do a lot to improve the quality of life for all women. Only 17% of Republicans say the same. Independents fall squarely in the middle: 28% say having more female leaders would do a lot to improve the lives of all women.

- This series of questions was included in a separate telephone survey. Respondents were not offered the option of choosing “no difference” as they were in the main survey, which was conducted online. They were, however, allowed to volunteer responses such as “no difference,” “both equally good” or “depends.” The mode of interview (telephone vs. online) may have had an impact on the share choosing a neutral category in this type of question. ↩

Social Trends Monthly Newsletter

Sign up to to receive a monthly digest of the Center's latest research on the attitudes and behaviors of Americans in key realms of daily life

Report Materials

Table of Contents

Among parents with young adult children, some dads feel less connected to their kids than moms do, many in east asia say men and women make equally good leaders, despite few female heads of government, for women’s history month, a look at gender gains – and gaps – in the u.s., race and lgbtq issues in k-12 schools, who are you the art and science of measuring identity, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Get New Issue Alerts

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Women, Power & Leadership

Many more women provide visible leadership today than ever before. Opening up higher education for women and winning the battle for suffrage brought new opportunities, along with widespread availability of labor-saving devices and the discovery and legalization of reliable, safe methods of birth control. Despite these developments, women ambitious for leadership still face formidable obstacles: primary if not sole responsibility for childcare and homemaking; the lack of family-friendly policies in most workplaces; gender stereotypes perpetuated in popular culture; and in some parts of the world, laws and practices that deny women education or opportunities outside the home. Some observers believe that only a few women want to hold significant, demanding leadership posts; but there is ample evidence on the other side of this debate, some of it documented in this volume. Historic tensions between feminism and power remain to be resolved by creative theorizing and shrewd, strategic activism. We cannot know whether women are “naturally” interested in top leadership posts until they can attain such positions without making personal and family sacrifices radically disproportionate to those faced by men.

Nannerl O. Keohane , a Fellow of the American Academy since 1991, is a political philosopher and university administrator who served as President of Wellesley College and Duke University. She is currently affiliated with the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University and is a Visiting Scholar at the McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society at Stanford University. Her books include Philosophy and the State in France: The Renaissance to the Enlightenment (1980), Higher Ground: Ethics and Leadership in the Modern University (2006), and Thinking about Leadership (2010). She is a member of the Board of Directors of the American Academy.

One of the most dramatic changes in recent decades has been the increasing prominence of women in positions of leadership. Many more women are providing leadership in government, business, higher education, nonprofit ventures, and other areas of life, in many more countries of the world, than would ever have been true in the past. This essay addresses four aspects of this development.

I will note the kinds of leadership women have routinely provided, and list factors that help explain why this pattern has changed dramatically in the past half century. I will mention some of the obstacles that still block the path for women in leadership. Then I will ask how ambitious women generally are for leadership, and discuss the fraught relationship between feminism and power, before concluding with a brief look at the future that might lie ahead.

As we approach this subject, we need to understand what we mean by “leadership.” I use the following definition: “Leaders define or clarify goals for a group of individuals and bring together the energies of members of that group to pursue those goals.” 1 This conception is deliberately broad, designed to capture various types of leadership, in various groups, not just the work of leaders who hold the most visible offices in a large society.

A leader can define or clarify goals by issuing a memo or an executive order, an edict or a fatwa or a tweet, by passing a law, barking a command, or presenting an interesting idea in a meeting of colleagues. Leaders can mobilize people’s energies in ways that range from subtle, quiet persuasion to the coercive threat or the use of deadly force. Sometimes a charismatic leader such as Martin Luther King Jr. can define goals and mobilize energies through rhetoric and the power of example.

It is also helpful to distinguish leadership from two closely related concepts: power and authority.

All leaders have some measure of power, in the sense of influencing or determining priorities for other individuals. But leadership cannot be a synonym for holding power. Power is often defined in the straightforward way suggested by political scientist Robert Dahl: “ A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do.” 2 A bully or an assailant with a gun wields power in this sense, but it would not be appropriate to call such a person a “leader.”

Leadership often involves exercising authority with the formal legitimacy of a position in a governmental structure or high office in a large organization. Holding authority in these ways provides clear opportunities for leadership. Yet many men and women we would want to call leaders are not in positions of authority, and not everyone in a formal office provides leadership. As John Gardner, author of several valuable books on leadership, noted, “We have all occasionally encountered top persons who couldn’t lead a squad of seven-year-olds to the ice cream counter.” 3

We can think of leadership as a spectrum, in terms of both visibility and the power the leader wields. On one end of the spectrum, we have the most visible: authoritative leaders like the president of the United States or the prime minister of the United Kingdom, or a dictator such as Hitler or Qaddafi. At the opposite end of the spectrum is casual, low-key leadership found in countless situations every day around the world, leadership that can make a significant difference to the individuals whose lives are touched by it.

Over the centuries, the first kind–the out-in-front, authoritative leadership–has generally been exhibited by men. Some men in positions of great authority, including Nelson Mandela, have chosen a strategy of “leading from behind”; more often, however, top leaders have been quite visible in their exercise of power. Women (as well as some men) have provided casual, low-key leadership behind the scenes. But this pattern has been changing, as more women have taken up opportunities for visible, authoritative leadership.

Across all the centuries of which we have any record, women have been largely absent from positions of formal authority. Such posts, with a few exceptions, were routinely held by men. Women have therefore lacked opportunities to exercise leadership in the most visible public settings. And as both cause and consequence of this fact, leadership has been closely associated with masculinity. In some parts of the world this assumption is still dominant: even in what we think of as the most advanced countries, there are people who think that men are “natural leaders,” and women are meant to follow them.

Yet despite this stubborn linkage between leadership and maleness, some women in almost every society have proved themselves capable of providing strong, visible leadership. Women exercised formal public authority when dynasty or marriage-lines trumped gender, so that Elizabeth I of England or Catherine the Great of Russia could rule as monarch. There are cultures in which wise women are regularly consulted, either as individuals or as members of the council of the tribe. All-female institutions are especially auspicious for women as leaders, including convents, girls’ schools, and women’s colleges, where women have often held authoritative posts.

Women have led in situations where men are temporarily absent: in wartime when the men are away fighting, or in a community like Nantucket in the eighteenth or nineteenth century, where most of the men were whaling in distant seas for years at a time. Women have provided visible leadership in movements for social betterment, including the prohibition and settlement house campaigns of the late nineteenth century and the battle for women’s suffrage. “First ladies” have leveraged their access to power to promote important causes. The impressive accomplishments of Jane Addams and Eleanor Roosevelt stand as prime examples of female leadership. Women have been leaders in family businesses in many different settings. And countless women across history have provided leadership in education, religious activities, care for the sick and wounded, cultural affairs, and charity for the poor.

So that’s a rough, impressionistic survey of the leadership women have exercised in the past: a very few “out front,” as queens or abbesses or heads of school, with many providing more informal leadership in smaller communities or behind the scenes.

This picture has changed dramatically in the past half-century. Many more women today hold authoritative posts, as prime ministers, heads of universities, CEOs of corporations, presidents of nonprofit organizations, and bishops in Protestant denominations. Why has this happened in the past few decades, rather than sooner, or later, or never?

As we ponder this question, we must also note that the changes have proceeded unevenly. It is still unusual for a woman to be CEO of a major public corporation or the president of a country with direct elections for the head of government, as distinct from parliamentary systems. Women’s leadership in religious organizations depends on the doctrines of the religion or sect and the influences of the surrounding society on how these doctrines are interpreted. We will look at some of the barriers blocking change in these and other areas.

And finally, are women as ambitious for leadership as men, or are there systematic differences between the two sexes in the appetite for gaining and using power? Can tensions between the core concepts of feminism and the wielding of power help us understand these issues?

In the past half-century, fifty-six women have served as president or prime minister of their countries. 4 In the United States, women hold office as senators and congresswomen, governors and mayors, cabinet officers and university presidents, heads of foundations and social service agencies, rabbis, generals, and principal investigators. Women have been the CEOs of GM, IBM, Yahoo, and Pepsi-Cola. There are women judges sitting at all levels of the court system, and women leaders in several prominent international organizations.

In the United States, the unprecedented numbers of women candidates in the 2018 midterm elections and the 2019 Democratic presidential primaries are striking examples of women tackling the long-standing identification of leadership with masculinity. One hundred and seventeen women won office in 2018, including ninety-six members of the House of Representatives, twelve senators, and nine governors. Each of these was a record number, compared with any year in the past. 5 Among Democrats, female candidates were more likely to win than their male counterparts. 6 Hillary Clinton’s candidacy for the presidency was a significant step in splintering, if not yet shattering, one of the hardest “glass ceilings” in the world. And Angela Merkel’s deft leadership for Germany and the European Union has provided a model for women in politics worldwide.

We can multiply instances from many different fields, from many different contexts: women today are much more likely to provide visible leadership in major institutions than they have been at any time in history.

Yet why have these changes occurred precisely at this time? I’ll suggest half a dozen factors that have made it possible for women to take these significant strides in leadership.

First is the establishment of institutions of higher education for women to-ward the end of the nineteenth century. Both men and women worked to open male institutions to women and to build schools and colleges specifically for women students. Careers and activities that had been beyond the reach of all women now for the first time became a plausible ambition. Higher education provided a new platform for leadership by women in many fields.

Virginia Woolf’s powerful essay A Room of One’s Own (1929) makes clear how crucial it was for women to be educated in a university setting. College degrees allowed women to enter professions previously barred to them and, as a result, become financially independent of their fathers and husbands and gain a measure of control over their own lives. Woolf’s less well-known but equally powerful treatise from 1939, Three Guineas, considers the impact of this development on social institutions and practices, including the relations between women and men.

The second crucial development, beginning in the late nineteenth century, was the invention of labor-saving devices such as washing machines and dryers, dishwashers and vacuum cleaners, followed in the second half of the twentieth century by computers and, later still, electronic assistants capable of ordering goods online to be delivered to your door. The women (or men) in charge of running a household today have far more mechanical and electronic support than ever before.

Ironically, for middle-class Americans today, much of the time freed up by these labor-saving devices has been redirected into “super-parenting”: parents are expected to spend much more time educating, protecting, and developing the skills of their children. Yet one might hope that these patterns could be more malleable than the punishing work required of our great-grandmothers to maintain a household.

Third is the success of the long struggle for women’s suffrage in many countries early in the twentieth century. Even more than the efforts that opened colleges and universities for women, the suffrage movements were deliberate, well-organized campaigns in which women leaders used their sources of influence strategically to obtain their goals. Enfranchised women could vote for candidates who advocated policies with particular resonance for them, including family- and child-oriented regulations and laws that tackled discriminatory practices in the labor market. Many female citizens voted as their fathers and husbands did; but the possibility of using the ballot box to pursue their priority interests was for the first time available to them. Women could also stand for election and be appointed to government offices. It is important to note, however, that in the United States, the success of the movement was tarnished by the denial of the vote to many Black persons in the South until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. 7

Fourth factor: the easy availability of reliable methods of birth control. Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own gives a vivid portrayal of women in earlier centuries who were hungry for knowledge or professional activity but bore and tended multiple children, making it impossible to find either the time or the opportunity to be educated. In the early twentieth century, there was for the first time widespread public discussion of the methods and moral dimensions of birth control. The opportunity to engage in family planning by controlling the number and timing of births gave women more freedom to engage in other tasks without worrying about unwanted pregnancies. By 1960, when “the pill” became the birth control device of choice for millions of women, the battle for legal contraception had largely been won in most of the world.

Next is women’s liberation, the “second wave” of feminism from the late 1960s through the early 1980s. This multifaceted movement encouraged countless women to reenvision their options and led to important changes in attitudes, behavior, and legal systems. The ideas of the movement were originally developed by women in Western Europe and the United States, but the implications were felt worldwide, and women in many other countries provided examples of feminist ideas and activities.

Among the most important by-products of the feminist movement in the United States was Title IX, passed as part of the Education Amendments Act in 1972. New opportunities for women in athletics and in combatting job discrimination followed the passage of this bill. There is ample evidence that participating in sports strengthens a girl’s self-confidence as well as her physical capacity. 8 And although the Equal Rights Amendment has not passed, the broadened application of the Fourteenth Amendment by federal courts made a significant difference in opening up equal opportunities for women.

A fifth factor contributing to greater scope for women’s activities is the change in economic patterns–contemporary capitalism–in which many families feel that they need two incomes to maintain themselves or achieve the lifestyle they covet. This puts more women in the workforce and thus on a potential ladder to leadership, despite remaining biases against women in jobs as varied as construction, teaching economics in a university, representing clients in major trials, and fighting forest fires.

Finally, the change in social expectations that is the cumulative result of all these developments, so that for the first time in history, in many parts of the world, it seems “natural” that a woman might be ambitious for a major leadership post and that with the right combination of talent, experience, and luck, she might actually get it. The more often it happens, the more likely it is that others will be inspired to follow that example, whereas in the past, it would never have occurred to a young girl that she might someday be CEO of a company, head of a major NGO, member of Congress, dean of a cathedral, or president of a university.

If you simply project forward the trajectory we have seen since the 1960s, you might assume that the future will be one in which all top leadership posts finally become gender-neutral, as often held by women as by men. The last bastions will fall, and it will be just as likely that the CEO of a company or the president of the country will be a woman as a man; the same will be true of other forms of leadership.

Sometimes we act as though this is the obvious path ahead, and the only question is how long it will take. On this point, the evidence is discouraging. The Gender Parity Project of the World Economic Forum predicted in 2015 that “if you were born today, you would be 118 years old when the economic gender gap is predicted to close in 2133.” 9 The report also notes that although gender parity around the world has dramatically improved in the areas of health and education, “only about 60% of the economic participation gap and only 21% of the political empowerment gap have been closed.”

Yet however glacial the rate of change, we may think: “we’ll get there eventually, because that’s where things are moving.” You might call this path convergence toward parity between men and women as leaders. This is the scenario that appears to underlie much of our current thinking, even if we have not articulated it as such.

This scenario, however, ignores some formidable barriers that women ambitious for formal leadership still face. Several familiar images or metaphors have been coined to make this point: “glass ceiling” or “leaky pipeline.” In Through the Labyrinth , sociologists Alice Eagly and Linda Carli use the ancient female image of the “labyrinth” to describe the multiple obstacles women face on the path to top leadership. It’s surely not a straight path toward eventual convergence. 10

The first and most fundamental obstacle to achieving top leadership in any field is that women in almost all societies still have primary (if not sole) responsibility for childcare and homemaking. Few organizations (or nation-states) have workplace policies that support family-friendly lifestyles, including high-quality, reliable, affordable childcare; flexible work schedules while children are young; and support for anyone caring for a sick child or aging parent. This makes things very hard for working parents, and especially for working mothers.

The unyielding expectation that one must show one’s seriousness about a job by being available to work nine- or ten-hour days, being on-call at any time of the week, and ready to move the family to wherever one’s services are needed is a tremendous obstacle to the advancement of women. Although hours worked are correlated with productivity in some jobs and professions, the situation is far more complicated than such a simple metric would indicate. Nonetheless, this measure is often used for promotion and job opportunities, explicitly or in a more subtle fashion. This expectation cuts heavily against a working mother, or a father who might want to spend significant time with his young children.

One of the most stubborn obstacles in the labyrinth is the lack of “on-ramps”: that is, pathways for women (or men) who have “stopped out” to manage a household and raise their children to rejoin their professions at a level commensurate with their talent and past experience. 11 Choices made when one’s children are born are likely to define the available options for a mother for the rest of her life, in terms of professional opportunities and salary level. We need more flexible pathways through the labyrinth so that women (or men) can–if they wish–spend more time with their kids in their earliest years and still get back on the fast track and catch up.

We need to work toward a world in which marriage with children more often involves parenting and homemaking by both partners, so that all the burden does not fall on the mother. We urgently need more easily available high-quality childcare outside the home so that working parents can be assured that their kids are well cared for while they both work full time. Reaching this goal will require more deliberate action on the part of governments, businesses, and policy-makers to create family-friendly workplaces. Such policies are in place in several European countries but have not so far been implemented in the United States. 12

Other labyrinthine obstacles include gender stereotypes that keep getting in the way of women being judged simply on their own accomplishment. Women are supposed to be nurturing, but if you are kind and sensitive, somebody will say you are not tough enough to make hard decisions; if you show that you are up to such challenges, you may be described as “shrill” or “bitchy.” This “catch-22” clearly plagued Hillary Rodham Clinton in her first campaign for the presidency and took an even more virulent form in her second campaign, when her opponent in the general election and his supporters regularly shouted profoundly misogynistic comments at her.

Women also have fewer opportunities to be mentored. Many (not all) senior women are happy to mentor other women; but if there aren’t any senior women around, and the men aren’t sympathetic, you don’t get this support. Some senior male professors or corporate leaders do try specifically to advance the careers of young women, but many male bosses find it easier to mentor young men, seeing them as younger versions of themselves; they take them out for a beer or a round of golf, and find it hard to imagine doing this for young women.

The #MeToo movement has brought valuable support to many women unwilling to speak out about sexual assault and harassment in the workplace. This is surely a significant step in removing obstacles to women’s advancement. However, this very visible effort has also made some male bosses nervous about reaching out to female subordinates in ways that might be misinterpreted. Men who are already deeply committed to advancing the cause of women do not usually react this way, but those who are less committed may use the #MeToo movement as an excuse not to support women employees, or more often, be genuinely uncertain about which boundaries are inappropriate to cross.

Another insidious obstacle for women on the path to top leadership is popular culture, a formidable force in shaping expectations for young people. Contemporary media rarely suggest a high-powered career as an appropriate ambition for a person of the female sex. The ambitions of girls and women are discouraged when they are taught to be deferential to males and not to compete with them for resources, including power and recognition. Women internalize these expectations, which leads us to question our own abilities. Women are much less likely to put themselves forward for a promotion, a fellowship, or a demanding assignment than men even when they are objectively more qualified in terms of their credentials. 13

And finally, in terms of obstacles to women’s out-front leadership, I have so far been describing the situation in Western democracies. As we know, women who might want to be involved in political activity or provide leadership in any institution face even more formidable obstacles in many parts of the world today. Think of Afghanistan, where the Taliban have denied women education or any opportunities outside the home. For young women in such settings, achieving professional status and leadership is a very distant dream.

For all of these reasons, therefore–expectations of primary responsibility for domestic duties, absence of “on-ramps” for returning to the workforce, gender stereotypes, absence of mentors, the power of popular culture, if not systematic exclusion from political activity–women ambitious for out-front leadership must deal with significant barriers that do not confront their male peers.

Addressing the topic of women’s leadership in terms of the obstacles we face makes sense, however, only if significant numbers of women are ambitious for top leadership. In an essay entitled “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby–and You’ve Got Miles to Go,” leadership scholar Barbara Kellerman asks us to consider the possibility that most women really do not want such jobs. As she put it, “Work at the top of the greasy pole takes time, saps energy, and is usually all-consuming.” So “maybe the trade-offs high positions entail are ones that many women do not want to make.” Maybe, in other words, there are fewer women senators or CEOs because women “do not want what men have.” 14

If Kellerman is right, as women see what such positions entail, fewer will decide that high-profile leadership is where our ambitions lie, and the numbers of women in such posts will recede from the high-water mark of the late twentieth century toward something more like the world before 1950. Women have proved that we can do it, in terms of high-powered, visible leadership posts. We have seen the promised land, and many women will decide they are happier where most women traditionally have been.

We found something of this kind in a Princeton study on the fortieth anniversary of the university’s decision to include women as undergraduates. President Shirley Tilghman charged a Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women’s Leadership, which issued its report in March 2011, with determining “whether women undergraduates are realizing their academic potential and seeking opportunities for leadership at the same rate and in the same manner as their male colleagues.” 15 In a nutshell, the answer was no: women were not seeking leadership opportunities at the same rate or in the same manner.

Many recent Princeton alumnae and current female students the committee surveyed or interviewed in 2010 were not interested in holding very visible leadership positions like student government president or editor of the Princetonian ; they were more comfortable leading behind the scenes, as vice president or treasurer. There had not been a female president of the student government or of the first-year class at Princeton in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Other young women told us that they were not interested in the traditional student government organizations and instead wanted to lead in an organization that would focus on something they cared about, working for a cause: the environment, education reform, tutoring at Princeton, or a dance club or an a cappella group.

When we asked young women about this, they told us that they preferred to put their efforts where they could have an impact, in places where they could actually get the work of the organization done, rather than advancing their own resumés or having a big title. In this, they gave different answers than many of their male peers. Their attitudes also differed markedly from those of the alumnae who first made Princeton coeducational forty years before. Those women in the 1970s or 1980s were feisty pioneers determined to prove that they belonged at Princeton against considerable skepticism and opposition. They showed very different aspirations than the female students of the first decade of the twentieth century and occupied all the major leadership posts on campus on a regular basis.

Thus, our committee discovered (to quote our first general finding): “There are differences–subtle but real–between the ways most Princeton female undergraduates and most male undergraduates approach their college years, and in the ways they navigate Princeton when they arrive.” We found statistically significant differences between the ambitions and comfort-levels of undergraduate men and women at Princeton in 2010, in terms of the types of leadership that appealed to them and the ways they thought about power.

If you project forward our Princeton findings, and if Barbara Kellerman and others who share her assumptions are correct, there is no reason to believe that women and men will converge in terms of types of leadership. You might instead predict that these differential ambitions will mean that women will always choose and occupy less prominent leadership posts than men, even as they make a significant difference behind the scenes.

However, this conclusion is at odds with the way things are changing today, at Princeton and elsewhere. In addition to hearing from women who preferred low-key posts, our committee learned that women who did consider running for an office like president of college government often got the message from their peers (mostly their male peers) that such posts are more appropriately sought by men. As the discussion of women’s leadership intensifies on campus, more women stand for offices they might not have considered relevant before. Quite a few women have held top positions on campus in the past decade.

The Princeton women tell us that mentoring is very important and being encouraged to compete for a post makes a big difference. When someone–an older student, a friend or colleague, a faculty or staff member–says to a young woman: “You really ought to run for this office, you’d be really good at this,” she is much more likely to decide to be a candidate. There is a good deal of evidence that this is true far beyond the Princeton campus, including the experiences of women who decide to run for political office or state their interest in a top corporate post. 16

Therefore, to those who assert that there is a “natural” difference in motivation that explains the disparities between men and women in leadership, I would respond that we cannot know whether this is true until more women are encouraged to take on positions of leadership. We cannot determine, also, whether women are “naturally” interested in top leadership posts until women everywhere can attain such positions without making personal and family sacrifices radically disproportionate to those faced by men.

In asking what drove the dramatic change in women’s opportunities for leadership over the past half-century, I mentioned as one factor the strength of second-wave feminism. From the point of view of women and leadership, it is ironic that this movement was firmly and explicitly opposed to having any individual speak for and make decisions for other members. The cherished practice was “consciousness-raising,” with a focus on group-enabled insights. The search for consensus and common views was a significant feature of any activity projected by feminist groups in this period.

Second-wave feminism led to some significant advances for women, but the rejection of any out-front leadership meant that the gains were more limited than some members of the movement had envisioned. As was the case with Occupy Wall Street in the twenty-first century, the rejection of visible public leadership constrained the development and implementation of policy, despite the passion and commitment displayed by thousands of participants. The antipathy of second-wave feminists to power, authority, and leadership also means that it is hard to envision a feminist conception of leadership without coming to terms with this legacy.

This tension between “feminism” and “power” long predates the second wave. As women from Mary Wollstonecraft onward have attempted to understand disparities between the situation of women and men, the power held by men–in the state, the economy, and the household–has been a central part of the explanation. Feminists have often identified power with patriarchy, and therefore seen power as antipathetic to their interests as women striving to flourish as independent, creative human beings, rather than as a possible tool for change.

As a result of this age-old linkage of power with patriarchy, one further step in the decades-long progression of women from subordinate positions to positions of authority and leadership is a reconstruction of what it means to provide leadership and hold power. These activities must be detached from their fundamental connection to patriarchy, to make them more compatible with womanhood. There is evidence that this is happening today, as more and more women see power as relevant for accomplishing their goals and are increasingly willing to be seen wielding it with determination and even relish.

Many women today, in multiple contexts and in different parts of the world, are becoming more comfortable with exercising authority and holding power, and are openly ambitious to do so. These leaders see no need to deny or worry about their femininity, but instead concentrate on gaining power and getting things done. For these women, to a large extent, their sex/gender is not a relevant variable.

However, the other side of the equation–men and other women becoming comfortable with women in power and seeing their sex/gender as irrelevant–is lagging behind. Women are ready to take on significant public leadership positions in ways that have never been true before. But what about their potential followers? Large numbers of citizens in many countries and employees in many organizations–men and women–may still be reluctant to accept women as leaders who hold significant power over their lives.

This fluid situation calls both for creative feminist theorizing and for consolidating steps that are already being taken in practice. One of the most effective ways to provide the groundwork for this next stage of development is for more and more women to step forward for leadership posts. As with other profound social changes, including a broader acceptance of homosexuality and support for gay marriage, observing numerous instances of the phenomenon that initially appears “unnatural” can lead, over a remarkably short period of time, to changes in values and beliefs.

People who discover that valued friends, coworkers, or family members are gay are often likely to change their views on homosexuality. The same, one might hypothesize, will be true with women in power, as powerful women become a “normal” part of governments and corporations. The more women we see in positions of power and authority, the more “natural” it will seem for women to hold such posts.